ABSTRACT

This article compares the conceptualisations of creativity between the early childhood policy frameworks from Iran and Australia to demonstrate how cultural differences influence understandings and representations of creativity. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2019. “PISA 2021 Creative Thinking Framework: Third Draft.” OECD. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA-2021-creative-thinking-framework.pdf. suggests that students in all contexts and across all levels of education need to learn how to engage productively in the practice of generating ideas, reflecting upon ideas valuing both relevance and novelty, and how to iterate their ideas to a satisfactory outcome. This research draws from Hofsted, G. 2020. “Hofsted Insights.” https://www.hofstede-insights.com/ and Hofstede, G. 1980. Culture's Consequences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. three dimensions of national cultures for interpreting the cultural differences between Australia and Iran, as well as Vygotsky, L. S. 1987. “Imagination and Creativity in Childhood.” In In the Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky, edited by R. W. Rieber and A. S. Carton. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Plenum Press socio-cultural theory. This study analyses how creativity is represented within the policy documentation drawing from four perspectives (psychology, education, sociocultural and art). Findings suggest similarities for how creativity was conceptualised, however, significant differences were found pertaining to culture. These results assist in understanding how global influences on early childhood education policies regarding creativity can be interpreted and implemented in response to different culturally- situated contexts. A significant implication of this study is its call for policy makers and teachers to factor in cultural differences in developing children’s creativity.

Introduction

Creativity in children is an important facet for research as neurologically, early childhood presents as the optimal period for creative cognitive development (Sawyer et al. Citation2003). The OECD (Citation2019, 12) proposed that creative thinking is a ‘process by which we generate fresh ideas. It requires specific knowledge, skills and attitudes. It involves making connections across topics, concepts, disciplines and methodologies’. This definition of creativity is reflective of many Western definitions, whereby a child who is ‘creative’ is inclined to show some form of novelty and/or innovation and problem-solving skills (Runco Citation2007; Lubart Citation1999; Beghetto and Kaufman Citation2007). What is not considered, is that creativity means different things to different cultures and how creativity is defined and understood is largely influenced by the social-cultural context of the child.

This paper presents a recent qualitative study, involving a comparative analysis of early childhood policies between early childhood education and care (ECEC) in Australia and Iran. A pervasive question relates to the extent to which culture could influence creativity (Rudowicz Citation2003). This research examines how the uniqueness of a particular sociocultural context or setting shapes a particular pattern for how creativity is understood. This article seeks to contribute to the growing body of literature on the importance of sociocultural differences in fostering children’s creativity. To begin this study, we examine the early childhood creativity literature tracing differing cultural influences that shape and define the early childhood policy frameworks of Australia and Iran.

Literature review

Defining creativity is a complex undertaking, with differing views presented from the fields of psychology, education, arts, and sociocultural research. From a psychological perspective, creativity is defined or perceived as being a person’s ‘multi-variational behaviour’(Runco and Albert Citation2010), which may incorporate different types of personality traits such as risk-taking, curiosity, imagination, and problem solving (Sawyer et al. Citation2003). This perspective contends that testament of creativity, also known as ‘creative disposition’, would closely align with imaginative play, adaptation, innovation, problem solving, planning, and making decisions (Andiliou and Murphy Citation2010; Sukarso et al. Citation2019). These characteristics closely align with the intentions of the OECD (Citation2019) for education, promoting skills, dispositions and abilities of children. According to the OECD, teachers should develop or improve pedagogical activities that nurture the creative and critical thinking skills of their students.

An educational perspective (Craft Citation2000; Edwards and Springate Citation1995; Tok Citation2022) places emphasis on the role of a teacher and his/her support towards a child, especially in terms of ‘individuality’, ‘choices’, and ‘ideas’. Teacher support may consist of one-to-one scaffolding, the provision of positive feedback, and promotion and encouragement of peer social interactions (Corsaro Citation1985; Fernie, Kantor, and Whaley Citation1995; Kudryavtsev Citation2011).Footnote1 In the context of early childhood education and care (ECEC), it is often argued that appropriate conditions and opportunities afforded would help facilitate a child’s creativity (National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education (NACCCE) Citation1999). In other words, from this point of view, creativity is not innate but rather contextualised within a system of change (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979, Citation1989). The individual abilities of the child are therefore dependant on the educational context and social environment.

The arts perspective is somewhat unique for its emphasis on and acknowledgment of the importance of artforms, notably, dance, drama, literature, imaginative writing, media, music, and visual arts (Dissanayake Citation1974; Ewing Citation2010). This consideration denotes an intimate association between two concepts: that a particular art form may foster a person’s sense of creativity and a person’s manifestation of his/her creativity may, in fact, reflect his/her understanding, feeling, and/or experience of a desired art form. Creativity articulated through the arts is most notably enacted within the Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education and care, with Loris Malaguzzi describing this philosophy of artistic expression through the hundred languages of children (Edwards, Gandini, and Forman Citation1998). Children are encouraged to express their ideas and thoughts through a variety of media or ‘languages’.

Sociocultural perspectives emphasise the importance of sociocultural ‘specificity’ and ‘contextualization’ (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979; Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Vygotsky Citation1978). From an educational point of view, sociocultural specificity and contextualisation contends that a person’s cognitive growth is embedded within a particular sociocultural context. Vgytosky’s (Citation1978) theory of sociocultural constructivism, for example, places strong emphasis on the potency of culture, and the extent to which a specific culture could shape a person’s cognitive growth. As such, it is envisaged that the development of creativity in children would closely align with the specificity of a sociocultural context (Runco and Johnson Citation2002; Vygotsky Citation1987), wherein cultural factors such as shared beliefs and/or dominant values (Hofstede Citation2011) make major contributions.

From the four perspectives presented, it is evident that the majority of creativity researchers (Runco Citation2007; Sternberg and Lubart Citation1996; Plucker and Beghetto Citation2004) have largely drawn from a psychological perspective, favouring a definition for creativity that supports novelty, innovation and problem-solving skills of an individual. What is lacking from the research available is a focus on early childhood, in particular how social and cultural factors influence the growing child’s creative ability.

Creativity in early childhood education

Sociocultural theories of cognitive development have provided a detailed theoretical account of creativity where ‘creative imagination’ arises and/or develops from children’s play activities (Vygotsky Citation1987). According to Vygotsky (1930, Citation1978), children engage in pretend play where they use their imagination to act out their ‘wishes’. At preschool age, children are unable to achieve their inner desires immediately and so, to resolve this tension, they ‘enter an imaginary, illusory world, in which the unrealizable desires can be realized, and this world is what we call play’ (Vygotsky Citation1978, 93). What is of significance, however, is that children gain pleasure from play because they are free to determine their own actions (Vygotsky Citation2016; Tok Citation2022).

Through social interactions, children come to learn and develop their personal understanding of the world and through play they are able to advance in their development of creativity (Fleer Citation2008; Rogoff Citation1990; Vygotsky Citation1987). Cultural practices within social contexts determine the type of creativity valued by a community (D'Andrade Citation1981; Lee and Walsh Citation2001; Rogoff Citation2003).Footnote2 For example, a child who lives in the Marshall Islands could perceive and believe that creativity is about his/her ability to make handicrafts from bamboo leaves. Whereas in Japan, a child’s creativity may be intimately linked to technological advances. Each culture places significant value on the creative pursuits that drive the economy and advancement of civilisation.

A sociocultural viewpoint of creativity places an emphasis on the ‘contextualization’ of creativity. Social interactions, where cultural skills are scaffolded and guided by more knowledgeable or capable others in the community, may assist a child in his/her development of creativity within a specific cultural context (Exner Citation1984; Holaday, LaMontagne, and Marciel Citation1994; Rogoff Citation2003). In summary, the sociocultural perspective of creativity in early childhood education is of considerable interest as it places strong emphasis on the notion of ‘situated context’ or the notion of specific contextualisation, which may intricately relate to and/or explain the development of a child’s creativity.

Cross-cultural perspectives of creativity in early childhood education

An interesting inquiry in early childhood education relates to cross-cultural perspectives of creativity. A review of contemporary research has indicated that people from the East and West hold similar, but not identical, conceptions of creativity (Morris and Leung Citation2010; Ramos and Puccio Citation2014). These differences focus on how people perform creatively and how they assess creativity. From the literature it can be concluded that Western countries focus more on novelty, innovation and individual success, whereas Eastern countries are more likely to view creativity collectively, having social and moral values, with a connection made between the new and the old (Niu and Sternberg Citation2006). The differences between East and West are related to the collectivist orientation of the East and the individualistic origin of the West (Lubart Citation2010; Ng Citation2001; Niu and Sternberg Citation2002). This paper reports on a study that compares the representations of creativity within policy documentation from Australia and Iran.

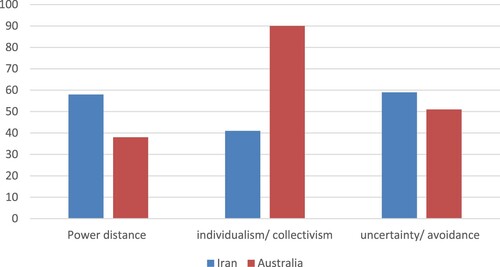

To better understand the cultural differences between Australia and Iran this study drew from Hofstede’s three dimensions/indexes of national cultures: Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, Individualism versus Collectivism (Citation1980, Citation2020). In the 1970s, Hofstede accessed a large survey database about values and related sentiments of people in more than 50 countries around the world (Hofstede Citation1980). Scores for Iran and Australia within the three indexes are reported in .

Hofstedes’ study has previously been used by many researchers who have studied the Australian and/or Iranian cultures in older age groups (Brand Citation2004; Kharkhurin & Samadpour Motalleebi Citation2008; Yoo Citation2014). It’s worth to note here that no early childhood studies were identified in these past studies.

From the first index of Power Distance, (which relates to the different solutions to the problem of human inequality), it is evident that Iranians accept a hierarchical order in which everybody has a place, and which needs no further justification. Australians on the other hand, appear to have a more equal relationship between managers and employees and, mostly, they consult and share information frequently, and communication is informal, direct and participative. From the second index, Uncertainty and Avoidance, Iran (59) received a higher score than Australia (51). This index indicates the level at which people are threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations and have created beliefs and institutions that try to avoid these. This confirms the collectivist approach within the Iranian culture as opposed to the individual freedom experienced within the Australian context. From the third index, Individualism vs Collectivism, (relating to the integration of individuals into primary groups), the Iranian score indicates a higher commitment to the member ‘group’, be that family, extended family, or extended relationships. In contrast, Australians could be described as having a ‘loosely-knit society’; that is, people look after themselves (Hofsted Citation2020, para 7).

In summary, comparative studies provide insight into how beliefs/values/attitudes form crucial elements of culture. A person’s beliefs/values can be understood by observing their consistent behaviour. According to Ajzen and Fishbein (Citation1975), there is a strong relationship between attitude and behaviour and creative behaviour as a social process is influenced by cultural beliefs (Csikszentmihalyi Citation1990; Davis et al. Citation2015; Vygotsky Citation1978; Shao et al. Citation2019). From this data, we suggest that creativity from a western perspective is more individualised and expressed in different ways, while in Iran, a collectivist approach to how a group of people will respond or behave to creative pursuits is expected. The next section introduces the context of the study.

Australian and Iranian early childhood education

Iran early childhood education services enrol children from birth to six years of age. Kindergarten services (three months to four years of age), operate under the supervision of the State Welfare Organization (Behzisty), while the Education Ministry of Iran supervise preschool services (four to six). The majority of both kindergarten and preschool programmes in Iran are private businesses. Early childhood education is not mandated (Sharifian Citation2018). In 2008, the Iranian Education and Training Department nationalised and standardised preschool policy through the implementation of the Iranian Education Preschool Frameworks (IEPF) (Iran Educational Preschool Framework (IEPF) Citation2008). The Iranian IEPF supports academic learning skills through a suite of workbooks designed for children aged four to six years to develop specific learning outcomes, such as confidence in reading, writing and numeracy.

Early childhood education in Australia operates under an Education Ministry (AIHWA Citation2022). To improve the quality of the life of young children in Australia, the Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) was established and a National Quality Framework (NQF)was agreed upon for all Australian Governments (State and Federal) to work together to provide better educational and developmental outcomes for children using education and care services (ACECQA Citation2023). The NQF includes: A National Law and National Regulations, National Quality Standard (NQS) assessment and quality rating process, and national learning frameworks.

Methods and methodology

Following from an ethical approval from Newcastle University in Australia (H0317), our methodological approach to this research commenced with an examination of each of the two country’s early childhood policies and documents with regard to the inclusion of creativity. Specifically, we analysed the Australian Early Years Learning Frameworks (EYLF) (AGDE Citation2022) and the Iranian Preschool Educational Framework (Iran Educational Preschool Framework (IEPF) Citation2008), extracting key themes and relevant words pertaining to creativity. This included: play, thinking, unique, and new ideas. In addition, the following words relating to creative dispositions were included: imagination, engagement, confidence, expression of ideas, confidence and curiosity.

Documentation that supported the design and development of the EYLF and IPEF were also reviewed, providing background information for the study. In Australia, these documents included the Melbourne Declaration (Ministerial Council on Education and Youth Citation2008), an ECE Discussion Paper (Productivity Agenda Working Group-Education Skills Training and Early Childhood Development Citation2008) and a research paper on the development of EYLF (Edwards, Fleer, and Nuttall Citation2008). In Iran, the only supporting documents found that could be accessed were children’s workbooks developed by the Iranian Education Ministry.

An initial analysis of the Australian supporting documents emphasised the need to develop a national framework for early childhood education, but there was little information about the concepts of creativity and culture. The three underpinning documents advocated for the importance of early childhood education, quality education and equity in education in Australia. A review of the Iranian children’s workbooks found that they were considered compulsory for pre-schoolers, and that children could work on them at home as well as at preschool. Iranian children have seven workbooks to work through in a year, each titled: social skills, math, science concepts, literacy, Islamic education, fine motor skills, and sudoku. The expectations of social behaviours are evident in children’s workbooks. For example, in the set of behavioural rules on learning the language concept (literacy) statements such as: ‘don’t eat too much food’, ‘never eat fruit before you wash’, ‘cut your nails when they are long’ can be found. These workbooks were noted for reflecting an influence of Western and Eastern cultures. For example, featured in a workbook that teaches math skills, there is an image of a rabbit holding a guitar and underneath the image is written: ‘This rabbit is singing’. The significance of this picture is that it features a Western cultural perspective of freedom for expressing creativity, while in the Islamic culture, playing a guitar, or expressing individual creativity such as singing, is illegal (Ghazizadeh Citation2011).

The review of documentation required the application of a summative analysis involving three steps: 1/ counting the keywords as identified from the literature review 2/ coding based on the four theoretical perspectives: psychology, sociocultural, art and education as identified in the literature (latent analysis) and 3/ analysing key words in relation to literature and research findings (Babbie Citation1992; Catanzaro Citation1988; Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). Therefore, analysis of the data involved a mixed methodological approach of quantitative and qualitative components whereby the researchers gathered data and the interrogated it further to reveal hidden meanings. The next section reports on quantitative findings focusing on keywords in the documentation.

Findings

Step 1 – Identification of key words prior to analysis

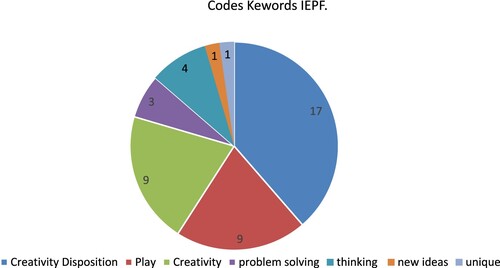

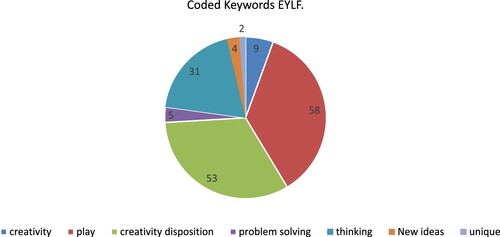

The first step in the analysis procedure, with the purpose of quantification, was to present a view of creativity as the central focus of this study, as well as selected keywords from creativity research. The analysis, therefore, searched for the words addressed in the literature that were associated with creativity, which included: creativity, thinking, play, problem solving, new ideas, unique, as well a range of dispositions that related to creativity. and indicate how the Australian EYLF and Iranian IPEF scored on selected keywords prior to the analysis.

Both documents linked creativity to main ideas pertaining to play, creative disposition, thinking and problem solving. From the data it was evident that the EYLF valued firstly play, then creative dispositions and thinking, while the IEPF recognised foremostly creative dispositions, then play and thinking as significant contributing factors to children’s creativity. It was interesting to note that in regard to creative dispositions, key words such as confidence, expressing ideas, imagination, and curiosity were used in both documents. However, the Australian EYLF also used words such as optimism, risk taking, persistence, enthusiasm and commitment. This confirms what Hofstede (Citation2011) suggested as key individual cultural elements for individual success. Risk-taking, persistence, enthusiasm and commitment were also recognised characteristics of children’s play, emphasising individual pursuits and accomplishments. The EYLF is recognised as a play-based curriculum, so this is not a surprise in the data. However, further investigation was required to examine the extent to which play was valued in children’s creativity within the Iranian documentation.

Play is a shared value associated with creativity (Russ Citation1999, 59; Vygotsky Citation1987). The conceptualisation of linking play to creativity was found within the two frameworks, however these have different cultural values. For example, the third criterion for play in the Iranian IEPF states that the educator should ‘consider increasing the children’s attention and giving positive feedback to increase creativity: play not only increases concentration but also increases creativity, self-confidence, creative discussion, problem solving and correct responses’ (Citation2008, 31). While play is recognised, this statement suggests that it is the role of the educator to increase or have control over the child’s creativity. On the other hand, the EYLF states: ‘play-based learning with intentionality can expand children’s thinking and enhances their desire to know and to learn, promoting positive dispositions towards learning’ (Citation2022, 21). This statement places greater emphasis on the child who is in control of his/her learning. This key cultural difference from the data highlights a significant cultural difference. Play and learning within the Australian context provides the child with control over his/her learning as well as freedom of expression, whereas in Iran, the educator is expected to guide group play where children through problem solving will find correct responses together. This finding lead to further examination of the documentation to understand how play was defined between the two contexts.

How play was defined and understood varied between the two early childhood policy documents. For example, the play criteria (points 4 and 5 of the IEPF) states that ‘4. Include logical meaning: for example, in the ‘sheep and wolf’ game children chase and escape from each other. 5. Make logical links between different components of a game: for example, connecting what they hear with how they respond. When children play the ‘fly game’ they have to raise their hands when hear the name of flying objects, and lower their hands for objects that do not fly’ (IEPF Citation2008, 32). These play examples s varies from a Western definition of play, indicating that play has enforceable rules. Literature describing Western cultures highlights that: ‘The more open play is and the more choices or control afforded to the child, the more likely play will be an enjoyable and creative experience for the child’ (Leggett Citation2014, 30). What is lacking from these examples is the child’s freedom of expression. Central to creativity and education is freedom and imagination (Vadeboncoeur, Perone, and Panina-Beard Citation2016; Hosseini Citation2014). Vygotsky stated that ‘we need to observe the principle of freedom, which is generally an essential condition for all kinds of creativity. This means that the creative activities of children cannot be compulsory or forced and must arise only out of their own interests’ (Vygotsky Citation2004, 84). The analysis of the IEPF indicated that local, ethical and traditional play was mostly about Islamic values and rules that originate from the dominant culture in Iran. In contrast, the EYLF does not mention a need to consider local, ethical and traditional play. The EYLF instead focuses on children’s interests and ideas forming the basis of policy documents decision making, recommending that educators ‘draw on diverse family and community experiences and expertise to include familiar games and physical activities in play’ (AGDE Citation2022, 42). The freedom of choice, in particular a child-centred approach to ECEC in Australia, varied immensely from the controlled experiences governed by rules imposed on children from Iran. The power of play exists in the hands of children from Australia, whereas play for children in Iran, is controlled by the educator.

Step 2 – Latent content analysis

A qualitative approach to analysis in the second step involved latent content analysis. Latent content analysis is most often defined as interpreting what is hidden deep within the text. In this method, the role of the researcher is to discover the implied meaning within the content (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). The reason for this analysis was to find out which of the four perspectives of creativity (psychology, education, arts, or sociocultural perspectives) were identified in the definition and scope of creativity for each country’s policy documents. Coding during latent content analysis allowed subthemes to emerge for each perspective.

From the data it was found that a psychology perspective of creativity involving thinking, new ideas, problem solving, and creative dispositions arose. From an educational perspective, subthemes such as educators’ roles and educational environments were emphasised. From an art’s perspective, subthemes of visual arts, music, dance, drama, painting, drawing and craft appeared, and from sociocultural perspectives, collaboration/partnership with families, communities, sharing ideas, and interaction between children emerged. presents data outlining the four perspectives as coded in the EYLF and the IEPF policy documentation.

Table 1. Four perspectives coded in the EYLF and the IEPF.

Latent content analysis of both the EYLF and IEPF indicated that a psychological perspective was the strongest presented, with the lowest focus on sociocultural perspectives. The different weighting between psychology and sociocultural perspectives signified a low contextualisation of creativity by the policy frameworks. Both documents suggested that creativity was part of cognitive development essential for thinking and learning. The EYLF scored much higher than the IEPF from an educational perspective, suggesting that Australian educators foster children’s creative thinking through challenging experiences and interactions. It was also interesting to note that drama, from an arts perspective in Iran, also promoted psychological factors such as memory and acting attentively, while the Australian arts perspective focused on gross and fine motor control (Alter, Hays, and O'Hara Citation2009).

Overall, from the data it can be conclude that educators from Iran were more likely to lead the children’s learning by providing new ideas, giving answers and solutions to assist children in their attendance to activities. This, as supported by Hofstede’s findings, is to maintain control over the child/rens’ learning. In contrast, the Australian policy document promoted individual children’s cognitive attainment whereby the child is encouraged to take the lead in his/her own learning. Educators within the Australian context are to respond to the ideas and prompts of the child. In contrast, the Iranian document maintains control of children’s learning under the direction of the educator. This has serious implications for how creativity is understood and promoted within differing social and cultural contexts, particularly for the role of the educator. The next section addresses the significant role of educators in fostering children’s creativity.

Step 3 – Key words during analysis

The last step in the summative analysis process was using open coding and searching for the emphasis of the frameworks. This step helped to understand each framework, providing a better opportunity to see the cultural differences between the EYLF and IEPF policies regarding creativity in early childhood education.

The EYLF is recognised as a child-centred framework that was found to cite ‘children’s learning’ 60 times. For example: ‘The Framework puts children’s learning at the core and comprises three inter-related elements: Vision, Principles, Practices and Learning Outcomes’ (AGDE Citation2022, 7). In a supportive research paper by Kennedy and Barblett (Citation2010), there is no separation between learning and play given that learning occurs through play. However, placing a greater emphasis on learning may give the impression that learning is prioritised over play (coded n = 60). The term ‘educator’s role’ appeared 46 times. The sub-themes that emerged from this data were the educator’s role in the learning environment, the educator’s role in assessment, the educator’s role in partnership with families, and the educator’s role in cultural competence on understanding children’s culture.

Educators have a significant role in children’s learning and in fostering creativity (Cheung and Leung Citation2013; Craft Citation2010; Daws Citation2005)Footnote3 however, the educator’s role specifically in connection to creative development was not evident in this search of the data. For example, according to creativity researchers, one of the teacher’s roles in supporting young children’s creativity is to achieve an optimum balance between structure and freedom of expression (Edwards and Springate Citation1995; Runco Citation2007; Tegano Citation1991). Another role is to develop children’s creativity through the professional interaction between the child and educators (Kudryavtsev Citation2011; Stojanova Citation2010). Neither of these aspects were mentioned in the EYLF. While the EYLF promotes children’s learning through play, it does not specifically address how creativity is supported by the educators. The EYLF refers to curiosity and creativity as a child’s ‘disposition’ stating that ‘play based learning’ ‘enhances thinking skills and lifelong learning dispositions such as curiosity, persistence and creativity’ (AGDE Citation2022, 8). In this sense, creative development is something the child learns through play.

Keywords during analysis identified in the IEPF were Islamic values, coded 33 times; thus, being the greatest score of all the codes for the IEPF. This code reflected a very strong feature of Iranian life and manifested in the IEPF. Following the Islamic Revolution in 1978, the ensuing strong emphasis on the Islamic religion brought about many changes, including the education system (Ghazizadeh Citation2011). In this study, words and references that were coded as Islamic values included: ‘Develop ethical and social skills according to Islamic values’ (9); and ‘Focus on the needs and interests of children and try to increase creativity of children based on Islamic principles and training’ (12). In addition, the Quran which guides the educators on how to make learning the Quran interesting for children is included. For example, telling an interesting story about the Quran, reading the Quran with an Arabic accent and interesting voice.

In Iran, in spite of families’ different religious backgrounds, children have to learn about Islamic values. Many researchers have found a relationship between religion, religiosity and creativity (Assouad and Parboteeah Citation2018; Nguyen Citation2012). For example, creative Islamic art in Iran includes mosque paintings and carpet designs that originated from the Islamic religion. A study by Liu et al. (Citation2018) explains that creativity is associated with challenging traditions and rules, and having a tolerance for diversity – all of which are discouraged by religious traditions such as Islam. So, if in learning Islamic religious traditions children are not permitted to ask any questions or challenge ideas, their thinking and creativity may be limited because they are denied the necessary creative processes in which children are encouraged to take risks, solve problems or contribute new ideas. This suggests that conformity in approaching creative tasks and endeavours must be maintained through rules so that cultural traditions will continue to exist.

This three-step analysis found similarities and differences between the frameworks on the conceptualisation of creativity. The main similarities were that creativity was defined by both frameworks as a thinking process that manifested through creativity dispositions and play. While it was agreed that play provided the best opportunity for children’s creativity, how play was experienced depended on the role of the educator and the educational context for the child. It was evident that the IEPF was strongly directed by Islamic law and religion served to infiltrate educational experiences that were collective and under the guidance and direction of educators in Iran. In the Australian context however, educators provided the environment for children to play and foster their creativity independently.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, the national early childhood education frameworks of Australia and Iran were analysed in order to respond to the research questions: How is creativity conceptualised in early childhood education within the contexts of Iran and Australia and are there similarities and/or differences between these policies’ perspectives?

The analysis of EYLF and IEPF found that creativity was mostly connected to children’s dispositions and was developed through their play. However further investigation revealed differences between the two frameworks indicating significant cultural influences. For example, the IEPF emphasised religious values through workbook activities and explicit teaching methods, providing samples of daily activity and the focus on group activities. While creativity was valued as part of developing children’s thinking, it is not culturally valued as a means for individual advancement or economic growth. In Iran, there is a strong connection to the past in order to maintain traditional values and control. Maintaining traditional creative artforms in early childhood is enforced through rules and collective experiences under the guidance of educators, with individual creative expressions suppressed. In contrast, a Western perspective promotes individual creativity within educational contexts as this is considered an essential tool for driving the economy. From the data presented in this study, it can be concluded that the Iranian teachers were more likely to encourage children’s creativity through group activities than individual ones (Alizadeh Citation2014; Nikosaresht Citation2010), whilst in Australia, teachers encouraged both individuality and collective efforts in creativity (McWilliam and Dawson Citation2008, 636; Venables Citation2011). There was also a difference found between educators in Iran who maintained control over children’s learning, while the Australian educators encouraged children to have control over their own learning.

Despite these differences, it is interesting to note that Western influences are evident in the work of Iranian researchers in creativity (Behpajoh Citation2009; Hosseini Citation2014) who cite a definition of creativity drawn from Western sources. This demonstrates the hegemony of Western societies and also explains the reason that the definitions of creativity in the EYLF and the IEPF are similar, however are implemented differently. Similarly, the finding of the study by Hamilton, Jin, and Krieg (Citation2019) reported similarities and differences between The Beijing Art Curriculum and the Australian Art Curriculum, which the similarities mainly resulted from globalization.

In summary the IEPF shows influences of both Western and local culture; for example, in defining creativity and linking it to play, problem solving and creativity dispositions. In the IEPF, the dominant cultural influences were evident in considering group activities in play rather than allowing children freedom to express their individuality, whereas the EYLF encouraged individuality and group activities.

This article is the first study to compare Iranian and Australian and national early childhood education frameworks, which internationally highlights the importance of early childhood as a critical stage for fostering creativity utilising a cultural focus. It is hoped that this research will open further study that investigates how different cultural communities foster creativity during the early years, particularly as it relates to the cultural and social contexts in which children are raised.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The paper is from PhD research conducted in Newcastle University in Australia. More data available http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1427296.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 (Stojanova Citation2010)

2 (Vygotsky Citation1978)

3 (Leggett Citation2014; Mellou Citation1996; Runco Citation2007, Citation1990)

References

- Australian Children Education and Care Quality Authority [ACECQA]. 2023. What is NQF?. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/nqf/about

- AIHWA. 2022. “Early Childhood Education and Care.” https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/australias-children/contents/education/early-childhood-education-and-care.

- Ajzen, Icek, and Martin Fishbein. 1975. “A Bayesian Analysis of Attribution Processes.” Psychological Bulletin 82 (2): 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076477.

- Alizadeh, N. 2014. “Effect of Traditional Play on Children's Creativity.” Saf Khanvadeh 68: 26–39.

- Alter, Frances, Terrence Hays, and Rebecca O'Hara. 2009. “Creative Arts Teaching and Practice: Critical Reflections of Primary School Teachers in Australia.” International Journal of Education & the Arts 10 (9): n9.

- Andiliou, A., and K. Murphy. 2010. “Examining Variations among Researchers’ and Teachers’ Conceptualizations of Creativity: A Review and Synthesis of Contemporary Research.” Educational Research Review 5 (3): 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.07.003.

- Assouad, Alexander, and K. Praveen Parboteeah. 2018. “Religion and Innovation. A Country Institutional Approach.” Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 15 (1): 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2017.1378589.

- Australian Government Department of Education [AGDE]. 2022. Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Frameworks for Australia (V2.0). Australian Government Department of Education and Ministerial Council. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/EYLF-2022-V2.0.pdf

- Babbie, E. 1992. The Practice of Social Research. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Beghetto, Ronald A., and James C. Kaufman. 2007. “Toward a Broader Conception of Creativity: A Case for "Mini-c" Creativity.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 1 (2): 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3896.1.2.73.

- Behpajoh, M. 2009. “What is Creativity? Who is Creative Child?” Pivand 356: 8–11.

- Brand, M. 2004. “Collectivistic Versus Individualistic Cultures: A Comparison of American, Australian and Chinese Music Education Students' Self-Esteem.” Music Education Research 6 (1): 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461380032000182830

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1989. “Ecological Systems Theory.” In Annals of Child Development: Theories of Child Development: Revised Formulations and Current Issues, edited by R. Vasta, 187–251. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Catanzaro, T. E. 1988. “A Survey on the Question of How Well Veterinarians are Prepared to Predict their Client's Human-Animal Bond.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 192 (12): 1707–1711.

- Cheung, Rebecca Hun Ping, and Chi Hung Leung. 2013. “Preschool Teachers’ Beliefs of Creative Pedagogy: Important for Fostering Creativity.” Creativity Research Journal 25 (4): 397–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2013.843334.

- Corsaro, W. 1985. Friendship and Peer Culture in the Early Years. Norwood: Ablex.

- Craft, A. 2000. Creativity Accross the Primary Curriculum. London: Routledge-Falmer.

- Craft, A. 2010. “Possibility Thinking and Wise Creativity: Educational Futures in England?” In Nurturing Creativity in the Classroom, edited by R. A. Beghetto and J. C. Kaufman, 289–312. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1990. “The Domain of Creativity.” In Theories of Creativity, edited by M. A. Runco and R. S. Albert, 190–212. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- D'Andrade, Roy Goodwin. 1981. “The Cultural Part of Cognition.” Cognitive Science 5 (3): 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog0503_1.

- Davis, S., B. Ferholt, H. G. Clemson, S.-M. Janson, and A. Marjanovic-Shane. 2015. Dramatic Interactions in Education: Vygotskian and Sociocultural Approaches to Drama, Education and Research. India: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Daws, James E. 2005. “Teachers and Students as co-Learners: Possibilities and Problems.” The Journal of Educational Enquiry 6 (1): 110–125.

- Dissanayake, Ellen. 1974. “A Hypothesis of the Evolution of art from Play.” Leonardo 7 (3): 211–217. https://doi.org/10.2307/1572893.

- Edwards, S. E., M. Fleer, and J. G. Nuttall. 2008. A Research Paper to Inform the Development of an Early Years Learning Framework for Australia. Melbourne: Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

- Edwards, C. P., L. Gandini, and G. E. Forman. 1998. The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach–Advanced Reflections. Westport, CT: Ablex.

- Edwards, C. P., and Kay Wright Springate. 1995. Encouraging Creativity in Early Childhood Classrooms. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Improvement (ED).

- Ewing, Robyn. 2010. The Arts and Australian Education: Realising Potential. Melbourne, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Exner, C. E. 1984. “The Zone of Proximal Development in In-hand Manipulation Skills of Nondysfunctional 3- and 4-year-old Children.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 38 (7): 446–451. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.38.7.446.

- Fernie, David E, Rebecca Kantor, and Kimberlee L Whaley. 1995. “Learning from Classroom Ethnographies: Same Places, Different Times.” Qualitative Research in Early Childhood Settings x: 155–172.

- Fleer, M. 2008. “Using Digital Video Observations and Computer Technologies in a Cultural-Historical Approach.” In Studying Children: A Cultural-Historical Approach, edited by M. Hedegaard and M. Fleer, 104–117. McGraw Hill: Open University Press.

- Ghazizadeh, Somayeh. 2011. “Cultural Changes of Iranian Music after Islamic Revolution.” Paper Presented at the International Conference on Humanities, Society and Culture IPDER.

- Hamilton, Amy, Yan Jin, and Susan Krieg. 2019. “Early Childhood Arts Curriculum: A Cross-Cultural Study.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 51 (5): 698–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2019.1575984.

- Hofsted, G. 2020. “Hofsted Insights.” https://www.hofstede-insights.com/.

- Hofstede, G. 1980. Culture's Consequences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Hofstede, G. 2011. “Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context.” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2 (1): 3–26. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014.

- Holaday, B., L. LaMontagne, and J. Marciel. 1994. “Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development: Implications for Nurse Assistance of Children’s Learning.” Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing 17 (1): 15–27. https://doi.org/10.3109/01460869409078285.

- Hosseini, A. S. 2014. “The Effect of Creativity Model for Creativity Development in Teachers.” International Journal of Information and Education Technology 4 (2): 138–142. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJIET.2014.V4.385.

- Hsieh, F. H., and E. S. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Iran Educational Preschool Framework (IEPF). 2008. Educational Curriculum Design. Tehran: Borhan.

- Kennedy, Anne, and Lennie Barblett. 2010. Learning and Teaching through Play: Supporting the Early Years Learning Framework. Deakin West: Early Childhood Australia.

- Kharkhurin, A .V., and S. N. Samadpour Motalleebi. 2008. “The Impact of Culture on the Creative Potential of American, Russian, and Iranian College Students.” Creativity Research Journal 20 (4): 404–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400410802391835

- Kudryavtsev, V. T. 2011. “The Phenomenon of Child Creativity.” International Journal of Early Years Education 19 (1): 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2011.570999.

- Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, K., and D. J. Walsh. 2001. “Extending Developmentalism: Cultural Psychology and Early Childhood Education.” International Journal of Early Childhood Education 7: 71–91.

- Leggett, Nicole. 2014. Intentional Teaching Practices of Educators and the Development of Creative Thought Processes of Young Children within Australian Early Childhood Centres. Newcastle: The University of Newcastle's Digital Repository.

- Liu, Zhen, Qingke Guo, Peng Sun, Zhao Wang, and Rui Wu. 2018. “Does Religion Hinder Creativity? A National Level Study on the Roles of Religiosity and Different Denominations.” Frontiers in Psychology 9 (1912): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01912.

- Lubart, T. I. 1999. “Creativity across Cultures.” In Handbook of Creativity, edited by R. J. Strenberg, 339–350. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Lubart, Todd. 2010. “Cross-cultural Perspectives on Creativity.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity., edited by J. C. Kaufman and R. J. Sternberg, 265–278. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- McWilliam, E., and S. Dawson. 2008. “Teaching for Creativity: Towards Sustainable and Replicable Pedagogical Practice.” Higher Education 56 (6): 633–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9115-7.

- Mellou, Eleni. 1996. “Can Creativity be Nurtured in Young Children?” Early Child Development and Care 119 (1): 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443961190109.

- Ministerial Council on Education, Employment Training, and Affairs Youth. 2008. Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians”.

- Morris, M., and K. Leung. 2010. “Creativity East and West: Perspectives and Parallels.” Management and Organization Review 6 (3): 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2010.00193.x.

- National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education (NACCCE). 1999. All our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education. London.: Department for Education and Employment.

- Ng, A. K. 2001. Why Asians are Less Creative than Westerners. Singapore: Prentice-Hall.

- Nguyen, K.-L. T. 2012. An Exploratory Study on the Relationship between Creativity, Religion, and Religiosity. California: San Jose State University.

- Nikosaresht, N. 2010. “How Parents Can Foster Creativity among Children?” Educational Training 86: 60–64.

- Niu, W., and R. J. Sternberg. 2002. “Contemporary Studies on the Concept of Creativity: The East and the West.” Journal of Creative Behavio 36: 270–288.

- Niu, W., and R. J. Sternberg. 2006. “The Philosophical Roots of Western and Eastern Conceptions of Creativity.” Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology 26 (1–2): 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0091265.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2019. “PISA 2021 Creative Thinking Framework: Third Draft.” OECD. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA-2021-creative-thinking-framework.pdf.

- Plucker, Jonathan A, and Ronald A Beghetto. 2004. Why Creativity is Domain General, Why it Looks Domain Specific, and Why the Distinction does not Matter”.

- Productivity Agenda Working Group-Education Skills Training and Early Childhood Development. 2008. “Early Childhood Life”.

- Ramos, Suzanna J., and Gerard J. Puccio. 2014. “Cross-cultural Studies of Implicit Theories of Creativity: A Comparative Analysis between the United States and the Main Ethnic Groups in Singapore.” Creativity Research Journal 26 (2): 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2014.901094.

- Rogoff, B. 1990. Apprenticeship in Thinking: Cognitive Development in Social Context. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Rogoff, B. 2003. The Cultural Nature of Human Development. New York, NY: Oxford University.

- Rudowicz, Elisabeth. 2003. “Creativity and Culture: A two way Interaction.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 47 (3): 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830308602.

- Runco, M. A. 1990. “The Divergent Thinking of Young Children: Implications of the Research.” Gifted Child Today Magazine 13 (4): 37–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/107621759001300411.

- Runco, M. A. 2007. Creativity. Theories and Themes: Research, Development and Practice. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier Academic Press.

- Runco, M. A., and R. S. Albert. 2010. “Creativity Research: A Historical View.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, edited by J C. J. Kaufman and R. Sternberg, 3–19. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Runco, M. A., and D. J. Johnson. 2002. “Parents’ and Teachers’ Implicit Theories of Children's Creativity: A Cross-Cultural Perspective.” Creativity Research Journal 14 (3-4): 427–438. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1434_12.

- Russ, S. 1999. “Play, Affect, and Creativity: Theory and Research.” In Affective, Creative Experince, and Psychological Adjustment, edited by S. Russ, 57–72. Ann Arbor, MI: Braun-Brumfield.

- Sawyer, R. K., V. John-Steiner, M. Csikszentmihalyi, S. Moran, D. Feldman, H. Gardner, R. J. Sternberg, and J. Nakamura. 2003. Creativity and Development. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Shao, Yong, Chenchen Zhang, Jing Zhou, Ting Gu, and Yuan Yuan. 2019. “How Does Culture Shape Creativity? A Mini-Review.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01219.

- Sharifian, M. 2018. “Early Childhood Education in Iran: Progress and Emerging Challenges.” International Journal of the Whole Child 3: 30–37.

- Sternberg, R. J., and T. I. Lubart. 1996. “Investing in Creativity.” American Psychologist 51 (7): 677–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.51.7.677.

- Stojanova, B. 2010. “Development of Creativity as a Basic Task of the Modern Educational System.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2 (2): 3395–3400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.522.

- Sukarso, A., A. Widodo, D. Rochintaniawati, and W. Purwianingsih. 2019. “The Potential of Students’ Creative Disposition as a Perspective to Develop Creative Teaching and Learning for Senior High School Biological Science.” Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1157: 022092. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1157/2/022092.

- Tegano, Deborah W. 1991. Creativity in Early Childhood Classrooms. NEA Early Childhood Education Series. Washington, DC: ERIC.

- Tok, Emel. 2022. “Early Childhood Teachers’ Roles in Fostering Creativity through Free Play.” International Journal of Early Years Education 30 (4): 956–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2021.1933919.

- Vadeboncoeur, J. A., A. Perone, and N. Panina-Beard. 2016. “Creativity as a Practice of Freedom: Imaginative Play, Moral Imagination, and the Production of Culture.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Creativity and Culture Research, edited by V. Glaveanu, 285–305. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Venables, R. 2011. “Fostering Artistic and Creative Expression in Children.” www.learninglinks.org.au.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1987. “Imagination and Creativity in Childhood.” In In the Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky, edited by R. W. Rieber and A. S. Carton. Vol. 1, 339–349. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 2004. “Imagination and Creativity in Childhood.” Journal of Russian & East European Psychology 42 (1): 7–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/10610405.2004.11059210.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 2016. “Play and Its Role in the Mental Development of the Child.” International Research in Early Childhood Education 7 (2): 3–25.

- Yoo, A. J. 2014. “The Effect Hofstedes Cultural Dimensions Have On Student-Teacher Relationships In The Korean Context.” Journal of International Education Research 10 (2): 171–178. https://doi.org/10.19030/jier.v10i2.8519