ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic caused unprecedented disruptions, including lockdowns and changes to family dynamics. Whilst extensive research has demonstrated how adults perceived this transformation and its effects on children, little attention has been given to how children perceive this period. This study explores how Israeli children experienced the COVID-19 period and their parents’ behavior during the lockdowns. Semi-structured interviews and a playing cards method were conducted with a sample of 50 children aged 3–6. Results indicate that children exhibited conscious awareness of the changes the pandemic brought into their lives. One significant change children highlighted was their parents’ behavior, largely in two areas: 1. Division of parental roles at home and 2. Permissiveness in matters of discipline, especially with regard to screen time. This study contributes to a better understanding of children’s experiences in crisis from their viewpoint. In addition, it interrogates the different types of parenting behavior that were practiced during the COVID-19 period. Keywords: COVID-19, early childhood, parents and children relation, context-informed perspective, children perspective.

Introduction

On February 27, 2020, the first COVID-19-infected patient was discovered in Israel. Israel immediately declared a state of emergency. In March 2020, the Israeli government decreed to shut down all kindergartens in Israel. For many children, this event also marked the first time they had heard of COVID-19 (Alter Citation2023). To fight the outbreak, Israel, like other countries, implemented a series of general lockdowns (Abulof, Penne, and Pu Citation2021). The lockdowns, which included shutting down the education system for prolonged periods, restructured the daily routine of families and led parents and children to spend more time together (de Souza et al. Citation2020; Mantovani et al. Citation2021). This new situation changed the daily routine, habits, and relationships of family members who were forced to stay together in an enclosed space (Roll et al. Citation2022).

As acknowledged by the World Health Organization (WHO Citation2020), the situation brought about by the pandemic may have had a multitude of implications for the mental well-being and family life of children and adults alike. Accordingly, since the outbreak of COVID-19, many studies have addressed the health (Lee et al. Citation2020) and psychological consequences of the pandemic on the family unit, mostly from the adult’s perspective (Brown and Greenfield Citation2021; Masten Citation2021).

Until the mid-1980s, most childhood research did not consider children’s perceptions (Corsaro Citation2017). The introduction of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989 (United Nations Citation1989), together with the Sociology of Childhood Theory, focused on research ‘with’ children not just ‘on’ children, which led to a change in the prevailing view and paved the way for studies that considered children as research partners and experts on their own world (Corsaro Citation2017; Mayall Citation2002). Even so, most studies to do with children have focused primarily on how adults perceive their children’s lives (Corsaro Citation2017).

This lacuna is even more pronounced when studying research that deals with how children perceive their parents and their parenting style (Tinnfält et al. Citation2018). Before the outbreak of COVID-19, several studies that included the children’s perspectives on their parents were conducted, mainly on children aged 8 and older. These studies focused mainly on examining how children perceive the family structure (Brannen and O’Brien Citation1996; Brannen, Lewis, and Nilsen Citation2002), the roles within the family (Mayall Citation2002; Tinnfält et al. Citation2018), time spent together (Lewis, Tudball, and Hand Citation2001), and punishment and discipline (Nixon and Halpenny Citation2010).

Among the few studies that do refer to how children perceive their parents’ behaviour, the study conducted by the Office of the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs in Ireland stands out (Nixon and Halpenny Citation2010). The study concluded that most children saw their parents as mentors and they reflected values and expectations important to their parents, such as education and good manners. Children aged 6–15 demonstrate a high awareness of parenting roles, with younger children emphasizing providing food, protection, and primary care. In comparison, older children emphasize the importance of parental guidance, emotional support, and authority (Nixon and Halpenny Citation2010). This study exemplifies children’s awareness of how the focus of parenting roles shifts from physical care (e.g. providing food) to psychological guidance as they grow up (Nixon and Halpenny Citation2010).

Only a few studies have attempted to learn about children’s experiences during the COVID-19 period through their own eyes and to explore their views on their parents’ experiences and parenting styles during the pandemic (Alter Citation2022; Hilppö et al. Citation2020). The studies show that, along with the challenges they encountered, children reported having more freedom and opportunity to make their own rules (Thompson, Spencer, and Curtis Citation2021), and that their parents’ behaviour became more permissive regarding TV time, which increased significantly (Szpunar et al. Citation2021). Another study conducted across six different countries reported children’s willingness to make sacrifices to support their families, demonstrating a strong sense of altruism (Bray et al. Citation2021). Children perceived parents as relying more on them for help, particularly concerning younger siblings and household chores (Alter Citation2022), prompting families with siblings to experience less stress during the pandemic (Hughes et al. Citation2023).

This study is based on context-informed perspectives (Nadan and Roer-Strier Citation2020), an ecological theory that highlights how the diversity of contexts (such as home, school, and extended family) affects children’s experiences differently. It further emphasizes the complexity, intersectionality, power dynamics, and resilience of these experiences (Nadan and Roer-Strier Citation2020). Combining this theory with the Sociology of Childhood Theory allows us to gain a deeper understanding of family life during COVID-19 from the children themselves and their perspective that they are agents who are capable of identifying social patterns around them, recognising changes, and be influential (Alter Citation2022; Corsaro Citation2017)

Recent literature on the impact of COVID-19 focused mainly on the economic and pedagogical consequences of the pandemic (e.g. Gromova Citation2020) and on how the pandemic has affected challenged populations economically, especially from the adult’s perspective (e.g. Roll et al. Citation2022). To enrich research that gives children a voice, this study focuses on children from families with middle-high socioeconomic status and examines how they experienced their parents and family during the pandemic.

Method

Since this study explores the subjective experiences of children, a qualitative methodology was chosen to understand their experiences holistically and as they are presented by the children in their own words (Mayall Citation2002).

Sample

The research was conducted among children living in Israel. The sample was selected using the snowball sampling technique where families introduced the author to other families. The final sample comprised 50 children aged 3–6 (mean age: 4.9 years), 28 boys (56%) and 22 girls (44%) from 43 families. The participants came from middle to high-socioeconomic-status families. lists the demographic characteristics of the children.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

Method

We conducted semi-structured interviews to explore children’s perspectives on their relationships with their family and specifically with their parents, during the COVID-19 pandemic. To tailor the interviews to children, we structured them as a card game (Alter Citation2023). Five cards, arranged in a fixed pattern, were placed in front of the child. The child was asked to pick up one card at a time. Each card contained a different open-ended question. In addition, the children could receive two cards with prizes (small gifts and stickers from the author’s box of surprises). The questions aimed to find out how children experienced the COVID-19 period: (1) Tell me a story about the COVID-19 period, (2) How did you feel during the COVID-19 period?, (3) How did your parents feel during the COVID-19 period?, (4) What were your responsibilities within your family during the COVID-19 period?, and (5) If you were to ‘meet’ COVID-19, what would you say to it? The author further expanded the interview based on the children’s answers in line with the semi-structured interview method (Alter Citation2023).

Procedure

Before each interview, the author coordinated the time and location with the children’s parents by phone. The parents were given information about the content and process of the interview, and it was explained to them that the emphasis would be on highlighting the children’s voices. After signing the consent form, the parents were requested to obtain their children’s consent for the interview as well. The author assured the parents that their children could stop the interview at any time.

The interviews were held in March 2021, immediately after the third lockdown. At this time, the children were starting to go back to school but only where the coronavirus morbidity rate was low but still under various restrictions. It was also the beginning of the vaccination period, but most people were not yet vaccinated and many were still working from home.

To test the interview questions, we conducted a pilot study with five children (three boys and two girls). Before each interview, the author met the children together with their parents. The parents remained nearby during the interviews and the children were assured they could have their parents join them at any time.

The author conducted all the interviews, and each interview lasted between 10 and 20 min (M = 14.83, SD = 2.59). The interviews took place at the children’s home or a nearby playground to ensure a familiar, relaxed, and informal atmosphere. The interviews were recorded, saved securely on the computer, and transcribed by the author. The children’s information was anonymized.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s School of Social Work and followed the committee’s guidelines: (1) obtaining signed informed consent forms from both the parent and the child, (2) guaranteeing confidentiality and discretion throughout the various stages of the study, and (3) assuring the parents and their children that they can stop the interview at any time without any consequences. All the names of the children in this paper are pseudonyms reflecting the child’s background.

Data analysis

All the interviews were conducted in Hebrew, transcribed, and translated into English by a bilingual English-Hebrew speaker (Alter Citation2023). The data was analysed using the Six Step Data Analysis Process (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) that inductively identifies and codes patterns or themes within and across the interview (Braun, Clarke and Gray Citation2017). This approach involves: (1) transcribing all answers and comments from the open-ended questions, (2) re-reading the transcripts to be familiar with the entire dataset, (3) coding the data by identifying topics that repeat themselves in the interviews, (4) collating the coded data into themes, (5) organising and reviewing the themes using thematic mapping, and (6) supporting the themes with relevant quotes from the dataset.

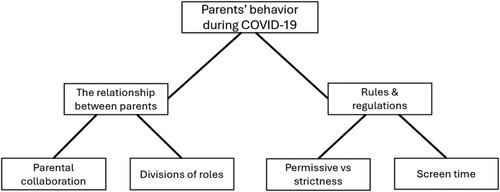

After the data collection stage, the interviews were coded and divided into sub-categories. Thereafter, units of interest in the findings were coded, and this led to the identification of several critical themes regarding parental roles and parenting characteristics. At the end of the process, two main themes emerged, and these were each further divided into two sub-themes. One theme is the relationship between the parents during the COVID-19 pandemic and it is divided into two sub-themes: (1) the parental distinction between work and play and (2) the division of roles between the parents. The other theme has to do with rules in the home and the parenting style, and it is divided into two sub-themes: (1) permissive versus strict parenting style and (2) the issue of screen time.

Results

depicts the two main themes of parental behaviour that emerged during the COVID-19 period as reflected in their children’s interviews: (1) the relationship between the parents and (2) rules and regulations in the home.

All the children mentioned their parents in their responses. The children reported changes in their parents’ behaviour largely across three themes: roles, collaboration, and attitudes regarding house rules. The children demonstrated an awareness that these changes were the consequence of COVID-19 and recognised the complexity of the new circumstances and the importance of familial support and collaboration to allow their parents to cope. Moreover, the children demonstrated an understanding that they needed to sacrifice their own needs and desires regarding their parents for the sake of general familial well-being or their parents’ well-being. This is exemplified in the following excerpt from the interview with Noa:

“I always asked them [her parents], ‘Do you prefer to work or be with us?’ and they always said, ‘What? Of course, to be with you!’”

“So, they said they prefer to be with you but in the end, did they work more or were they more with you?”

“Worked more because it’s more important.”

“Why is that more important?”

“It’s more important because you have to work; that’s how you get money. My dad also always worked on Zoom, my mom worked on Zoom in the room, and Carmel (the little brother) had nothing to do. We were always bored. But that way, they could buy things for the house.” (Noa, girl, aged 6)

The relationships between parents

The complementary needs described by children were not limited to the child-parent relationship but also had implications on how they viewed the relationship between their parents. According to a large proportion of the sample (58%), COVID-19 caused parents to adjust to new lifestyles as well, which affected their relationship in two main ways: the division of roles in the home and collaboration.

Division of roles in the home

We can learn about the changes in the division of roles in the home from the children’s narratives about day-to-day activities before and after the pandemic. Nimrod described this as follows:

Before the corona, my mother took me to kindergarten but during the lockdown, my father took me to kindergarten. (Nimrod, boy, aged 3)

When we are at home, our dad works in the kitchen and our mom is with the laundry. (Gali, girl, aged 4)

My mom cleans the house, sleeps, tidies up the house, and goes to work. My dad also goes to work and sleeps. (Natalie, girl, aged 5)

It is clear that changes in parents’ work patterns, such as staying at home most of the time either due to being able to work remotely or job dismissal (Bick, Blandin, and Mertens Citation2020; Shockley et al. Citation2021), did affect family life and had a psychological and mental impact on parents (Roll et al. Citation2022). These changes led to the establishment of new patterns and role divisions within the nuclear family. Children have specific notions about parenting roles within the family (Brannen, Lewis, and Nilsen Citation2002). The interviews demonstrate how the pandemic influenced and even transformed how children perceive their parents’ ‘traditional roles.’ This is particularly evident in how children had to adopt new norms of behaviour due to the new spatial and temporal realities of their parents’ work needs (such as working from home during the day), which contrasted with their earlier perception of gendered roles. The changes imposed by the pandemic did not go unnoticed by the children in the current study, as can be learned from Amir:

Now only my mom goes to work. My dad has a restaurant, and he is not going to work. He is staying at home with us all day long. (Amir, boy, age 5)

Parental collaboration

The second source of the change in the parents’ relationship that many children (51%) brought up in the interviews was their parents’ collaboration as reflected in the division of household chores. The primary motivation for their parents’ collaboration stemmed from their need to look after their children and to spend time with them.

My parents took turns because they didn’t have to be in lockdown at the beginning. So, at first, they did shifts – whoever watched over me in the morning had to work in the evening, and whoever watched over me in the evening, worked in the morning. (Anael, girl, aged 6)

Mom and Dad said they would tell us every morning who stayed at home and who would go to work. And whenever someone went to work, the other one would prepare food and play with us. (Ami, boy, aged 4)

In general, this theme highlights how children observed changes in their parents’ roles and collaboration during COVID-19, noting shifts in household responsibilities and work patterns that led to a more collaborative and flexible approach to managing family life amidst the challenges of the pandemic.

Rules and regulations at home

The second theme that was raised by half the children concerned rules and regulations in the home. Two main items were highlighted by the children: permissiveness versus strictness, i.e. the flexibility of the rules and regulations at home during the pandemic and screen time. Compared to the period before COVID-19, many children pointed out that they had more screen time during the pandemic (television, tablet, and other gadgets).

Permissiveness versus strictness

According to almost half of the children interviewed (46%), during the COVID-19 period, parents softened their parenting behaviour and were more lax when enforcing rules and regulations in the home, as Noa describes:

Lockdown is fun because we can do all the time things that we weren’t allowed to do before. (Noa, girl, aged 5)

Usually, Mom says we should go to bed early, but during corona, friends slept over at my home, and we went to bed late. (Anat, girl, aged 6)

It was fun because I ‘made trails’ through the house and tramped on the armchair, which I had never been allowed to do before. (Nira, girl, aged 4)

The children in our study identified a softening in their parents’ parenting style during the pandemic. The children stated that the joint and intensive period at home caused their parents to be more permissive and less strict about the rules and regulations that they had enforced before the pandemic. These findings are consistent with other studies that examined children’s perceptions of family relationships during the COVID-19 period (de Souza et al. Citation2020; Zhao et al. Citation2020). They suggest that there is room to examine the issue of parental discipline during a crisis period from a cultural perspective.

It was observed among a few children during the lockdowns that, along with the flexibility of certain rules, there was a toughening of other rules related to COVID-19, for example, Amir says:

“During the lockdowns, I watched TV all the time, but that’s also because my mother refused to allow friends to visit me.”

Interviewer: “Why didn’t she agree?”

“I think it’s because of the corona, but she never told me.” (Amir, boy, aged 5)

Screen time

The permissiveness the children referred to was expressed mainly with regard to the issue of screens. Some of the children (42%) described how the family behaved concerning screens as one of the differences between the pre-pandemic period and the pandemic period that they experienced:

It is more fun to eat during COVID-19 because we can watch TV. (Benny, boy, aged 3)

Because I was in front of the TV all the time … [and before] I was only sometimes. (Ravid, boy, aged 5)

Mom lets us watch movies so that we won’t get bored. (Yael, girl, aged 6)

Because every time I go to grab the tablet, she [his mother] says, ‘You have to tell me before that. If you don’t tell me, I will never let you have it. (Hussein, boy, aged 6)

While the first theme focuses on changes in family dynamics and roles, particularly for parents, the second theme reveals children’s observations of more permissive parenting during the pandemic and being allowed significantly more screen time as a result of the pandemic and spending more time together in the home.

Discussion

The current study focuses on the children’s perspectives on their parents’ behaviour and patterns during the COVID-19 period. All children in our study mentioned changes in their families during the COVID-19 period. This is in line with the sociology of childhood theory that sees children as agents who can identify social patterns around them, be aware of changes, and believe that they can influence them (Corsaro Citation2017).

The effects of changes in the parent’s work habits, in the division of parental roles, and in the parental partnership

This study shows that children aged 3–6 can understand and describe their parents’ behaviour while internalising and successfully adapting to the changes that this behaviour brought to their lives. The literature on parenting focuses on the importance of the parent’s awareness of their children’s behavioural changes (Lee, Schoppe-Sullivan, and Kamp Dush Citation2012; Tinnfält et al. Citation2018). However, a discussion on children’s awareness of their parents’ change of behaviour is absent from this discourse. The current paper discusses children’s perspectives and highlights the critical aspects of context-informed theory – hybridity (Nadan and Roer-Strier Citation2020). Hybridity is a concept that captures the complexity and dynamic nature of cultural change in the lives of individuals. It emphasizes the mixed, composite nature of cultural shifts and the ability of individuals to be aware of and respond to these changes (Roer-Strier and Nadan Citation2020). In this paper, hybridity refers to the children’s hybrid perspectives regarding the changes in their parent’s behaviour against the backdrop of the impact of COVID-19 on their lives. The children were aware of the changes and identified the changes that took place in their environment because of COVID-19 (Bray et al. Citation2021). The children’s ability to recognise the rapid hybridisation that characterised the pandemic period and to accept and come to terms with the changes in their environment, particularly in their family life, may have led them to act responsibly and to internalise the complexity brought about by the pandemic (Alter Citation2022).

The economic situation caused one of the most significant changes in family life during the COVID-19 period (Roll et al. Citation2022; Shockley et al. Citation2021). Many studies showed that one of the consequences of the COVID-19 period is the effect it had on the parents’ work patterns (Roll et al. Citation2022; Shockley et al. Citation2021). This reality forced many families to adapt to the new circumstances. The parents had to cope as individuals, as couples, and as heads of families (Roll et al. Citation2022), while the children had to adjust to a new reality without their grandparents, friends, school, etc. (Alter, Citation2023; Aram et al. Citation2021).

Studies on COVID-19 show that changes to their parents’ work were a leading source of concern to many children (Aram et al. Citation2021; Paryente and Gez-Langerman Citation2020) and significantly impacted their lives (Lawson, Piel, and Simon Citation2020). Changes in work patterns or, in some cases, the lack of work during the pandemic, led to a change in the division of roles between the parents (de Souza et al. Citation2020). While, in some families, the gender-stereotyped division of labour between parents remained the same, we can see that most of the children in our study mentioned considerable differences in the division of roles before and during the COVID-19 period. The differences were reflected in household chores, which were mainly imposed on the mother in the past, and now both parents share them equally. The children often used the term ‘they’ to refer to both parents as in ‘they cleaned up after us,’ meaning that they noticed that both parents did the chores. Various studies conducted with children during COVID-19 did not address the issue of the parents’ roles in the home. However, in some studies, as in the current study, it was noted that the children do not refer to a specific parent when describing the roles of their parents but instead, they use the word ‘they’ (Paryente and Gez-Langerman Citation2020; Szpunar et al. Citation2021).

Our findings are in alignment with various studies that show that children felt that although their mothers still played a more prominent role in their daily lives, fathers did take on more responsibilities, and the family became more united during the COVID-19 period (Cartmell and Pope Citation2022; de Souza et al. Citation2020). The children in this study pointed to the partnership and dialogue between their parents when discussing day-to-day life.

Parenting styles and enforcement of house rules

There is evidence that the COVID-19 period and the intense period being cooped up at home impacted the parent–child relationship and the parenting style (Aram et al. Citation2021; Chung, Lanier, and Wong Citation2020). Most of the children in our study experienced a change in their parent’s parenting style, which became more permissive. Aram et al. (Citation2021) found that during the COVID-19 period, parents found it challenging to enforce household rules, particularly in light of the need to allow their children more autonomy. In contrast, other studies show that the effect of stress and tension during the pandemic manifested as a shift to a more rigid style among parents (Chung, Lanier, and Wong Citation2020).

In studies that examined children’s perspectives, however, the consensus among children is that the parenting style of their parents becomes more permissive (Cartmell and Pope Citation2022; de Souza et al. Citation2020). As in the current study, the children described doing more activities together with their parents compared to what they used to do before COVID-19. In addition, the children reported that their parents gave them more freedom to pursue their own interests (Thompson, Spencer, and Curtis Citation2021). A study among Chinese children aged 3–6 found that for half of the children, their sleep patterns changed during the pandemic: they were allowed to go to bed later and wake up later than they used to. Moreover, 31% of the children reported prolonged mealtimes and 55% reported decreased physical activity. The explanations given by the parents were: they had to run the household, they worked from home, they helped their children cope with boredom, and they avoided conflicts with their children (Zhao et al. Citation2020).

Another aspect of the rules and regulations in the home that is reflected in the current study is screen time. Many children described their parents’ behaviour as more permissive than it used to be towards various aspects around the house, mainly allowing more screen time. These findings align with other studies on children’s perspectives during COVID-19, in which children stated that their parents’ parenting style had changed and was more permissive (Cartmell and Pope Citation2022). According to Zhao et al. (Citation2020), 66.7% of the students in their study reported engaging in less than one hour of screen time a day, while 13% reported more than 3 h a day. Ben-Arieh, Brook, and Farkash (Citation2020) found that 77% of the Israeli children aged 10–16 in their study spent most of the day watching screens during the pandemic.

In more cases than not, the parents’ behaviour towards their children tended to be more permissive, a theme that is reflected in the current study as permissiveness that mainly manifested as allowing the children more screen time.

Conclusions

This study provides a unique perspective on family life during the pandemic. Most studies on early childhood, parenting, and family relationships have focused on the perspective of adults, while little attention has been paid to the perspective of children.

Children’s ability to recognise changes and to adapt to them has emerged in various studies conducted during COVID-19 (Alter Citation2023; Bray et al. Citation2021). The current study demonstrates children’s ability to recognise the hybridity that existed during the COVID-19 period, as evidenced in their awareness of changes in family life and in their parents’ behaviour. The current study also brings to the surface not only children’s awareness of parenting and how it changed during the COVID-19 period but also the fact that these changes occurred as a result of COVID-19.

Recognising the child’s perceptions and not viewing them from a position of power, especially in times of crisis such as COVID-19, may allow researchers and educators to devise interventions based on a context-informed approach. Considering children’s voices can enable children to be equal partners in social life in general and in family life in particular.

Limitations

The current study has some limitations. Since the children interviewed came from medium and high-socioeconomic-status households, the findings reflect a more privileged group within Israeli society. This study was conducted during the COVID-19 period; therefore, it was not possible to compare the children’s perception of their parent’s behaviour during this period to their perception before the pandemic. There are some references to this in the interviews; however, there is room for further studies to expand this topic. Due to the limited sample size, the study cannot identify meaningful patterns in families from different cultural and religious backgrounds, family structures, and geographic areas. Another limitation is the timing of the study. It was conducted at the end of the third lockdown and right before the vaccination campaign began. Hence, the study’s findings may reflect this specific period when the effects of COVID-19 were relatively new and people reacted with more urgency. Even nowadays, outside of the context of lockdowns, COVID-19 is part of everyday life in Israel. In the future, longitudinal and historical studies may help us better understand how the COVID-19 crisis affected family dynamics and children’s development, and how these effects relate to various cultural contexts and family structures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abulof, U., S. L. Penne, and B. Pu. 2021. “The Pandemic Politics of Existential Anxiety: Between Steadfast Resistance and Flexible Resilience.” International Political Science Review 42 (3): 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/01925121211002098

- Alon, T., M. Doepke, J. Olmstead-Rumsey, and M. Tertilt. 2020. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality (No. w26947).” National Bureau of economic research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26947.

- Alter, O. P. M. 2022. “Children During Coronavirus: Israeli Preschool Children’ s Perspectives.” Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology 3: 100032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cresp.2021.100032.

- Alter, O. P. M. 2023. “Children Talk About Corona: The Experience of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Perceived Agency of Children Aged 3–6 from Israel.” PhD diss., Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Aram, D., G. Meoded-Karabanov, M. Assaf, and M. Ziv. 2021. “Parenting in Israel in Times of the Epidemic: Jewish and Arab Parents’ Perceptions of Their Behavior According to the “Five-Parenting” Model.” In The Days of Corona: Preschool Children in Times of Crisis, edited by O. Koret, and D. Givon, 149–178. Romat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University.

- Ben-Arieh, A., S. Brook, and H. Farkash. 2020. Perceptions and Feelings of Children and Adolescents in Israel Regarding the Coronavirus and Their Personal Lives. Haruv Institute (Hebrew). https://haruv.org.il/haruv-media.

- Bick, A., A. Blandin, and K. Mertens. 2020. Work from Home after the COVID-19 Outbreak (Working paper 2017). Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. https://doi.org/10.24149/wp2017.

- Brannen, J., S. Lewis, and A. Nilsen, eds. 2002. Young Europeans, Work, and Family. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203471852.

- Brannen, J., and M. O’Brien. 1996. Children in Families: Research and Policy. London: Psychology Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, and D. Gray, eds. 2017. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide to Textual, Media and Virtual Techniques. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781107295094

- Bray, L., B. Carter, L. Blake, H. Saron, J. A. Kirton, F. Robichaud, et al. 2021. ““People Play it Down and Tell me it Can’t Kill People, but I Know People are Dying Each day”. Children’s Health Literacy Relating to a Global Pandemic (COVID-19); An International Cross Sectional Study.” PLoS One 16 (2): e0246405. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246405

- Brown, G., and P. M. Greenfield. 2021. “Staying Connected During Stay-at-Home: Communication with Family and Friends and its Association with Well-Being.” Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 3 (1): 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.246

- Cartmell, K. M., and D. Pope. 2022. “Children’s Chatter: Daily Reflections of Young Children During Covid-19 Lockdown.” Psychology of Education Review 46 (1): 58–67. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsper.2022.46.1.58.

- Chung, G., P. Lanier, and P. Y. J. Wong. 2020. “Mediating Effects of Parental Stress on Harsh Parenting and Parent-Child Relationship During Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in Singapore.” Journal of Family Violence 37 (5): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10896-020-00200-1/TABLES/3.

- Corsaro, W. A. 2017. The Sociology of Childhood. Washington DC: Sage Publications.

- de Souza, J. B., T. Potrich, C. N. de Brum, I. T. S. B. Heidemann, S. S. Zuge, and A. L. Lago. 2020. “Repercussions of the COVID-19 Pandemic from the Childrens’ Perspective.” Aquichan 20 (4): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2020.20.4.2.

- Gromova, N. S. 2020. “Pedagogical Risks as Consequences of the Coronavirus COVID-19 Spread.” Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 486 (1): 350–355. https://doi.org/10.2991/ASSEHR.K.201105.063.

- Hilppö, J., A. Rainio, A. Rajala, and L. Lipponen. 2020. “Children and the COVID-19 Lockdown: From Child Perspectives to Children’s Perspectives.” Cultural Praxis 20 (6): 24–32. https://culturalpraxis.net/children-and-the-covid-19-lockdown-from-child-perspectives-to-childrens-perspectives/.

- Hughes, C., L. Ronchi, S. Foley, C. Dempsey, S. Lecce, and I-Fam Covid Consortium. 2023. “Siblings in Lockdown: International Evidence for Birth Order Effects on Child Adjustment in the Covid19 Pandemic.” Social Development 32 (3): 849–867. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12668

- Lamb, M. E., and C. S. Tamis-Lemonda. 2004. “The Role of the Father.” The Role of the Father in Child Development 4: 100–105. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232604349_The_Role_of_the_Father_An_Introduction.

- Lawson, M., M. H. Piel, and M. Simon. 2020. “Child Maltreatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Consequences of Parental Job Loss on Psychological and Physical Abuse Towards Children.” Child Abuse & Neglect 110: 104709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709

- Lee, P. I., Y. L. Hu, P. Y. Chen, Y. C. Huang, and P. R. Hsueh. 2020. “Are Children Less Susceptible to COVID-19?” Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection 53 (3): 372. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMII.2020.02.011.

- Lee, M. A., S. J. Schoppe-Sullivan, and C. M. Kamp Dush. 2012. “Parenting Perfectionism and Parental Adjustment.” Personality and Individual Differences 52 (3): 454–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAID.2011.10.047.

- Lewis, V., J. Tudball, and K. Hand. 2001. “Family and Work: The Family’s Perspective.” Family Matters 59: 22–27. https://doi.org/10.3316/agispt.20013997.

- Mantovani, S., C. Bove, P. Ferri, P. Manzoni, A. Cesa Bianchi, and M. Picca. 2021. “Children ‘Under Lockdown’: Voices, Experiences, and Resources During and After the COVID-19 Emergency. Insights from a Survey with Children and Families in the Lombardy Region of Italy.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 29 (1): 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2021.1872673

- Masten, A. S. 2021. “Resilience of Children in Disasters: A Multisystem Perspective.” International Journal of Psychology 56 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12737

- Mayall, B. 2002. Towards a Sociology for Childhood: Thinking from Children’s Lives. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Medcalf, N. A., T. J. Hoffman, and C. Boatwright. 2013. “Children’s Dreams Viewed Through the Prism of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.” Early Child Development and Care 183 (9): 1324–1338. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2012.728211.

- Nadan, Y., and D. Roer-Strier. 2020. “A Context-Informed Approach to the Study of Child Risk and Protection: Lessons Learned and Future Directions.” In Context-Informed Perspectives of Child Risk and Protection in Israel, 317–331. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12393.

- Nixon, E., and A. M. Halpenny. 2010. Children’s Perspectives on Parenting Styles and Discipline: A Developmental Approach. The Stationery Office. https://doi.org/10.1037/e530912013-001.

- Paryente, B., and R. Gez-Langerman. 2020. “Kindergarten Children’s Reactions to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Creating a Sense of Coherence.” Journal of Early Childhood Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X221145471

- Renk, K., R. Roberts, A. Roddenberry, M. Luick, S. Hillhouse, C. Meehan, A. Oliveros, et al. 2003. “Mothers, Fathers, Gender Role, and Time Parents Spend with Their Children.” Sex Roles 48 (7/8): 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022934412910

- Roer-Strier, D., and Y. Nadan, eds. 2020. Context-informed Perspectives of Child Risk and Protection in Israel. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing.

- Roll, S., Y. Chun, O. Kondratjeva, M. Despard, T. M. Schwartz-Tayri, and M. Grinstein-Weiss. 2022. “Household Spending Patterns and Hardships During COVID-19: A Comparative Study of the US and Israel.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 1: 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10834-021-09814-Z/FIGURES/7.

- Shockley, K. M., M. A. Clark, H. Dodd, and E. B. King. 2021. “Work-family Strategies During COVID-19: Examining Gender Dynamics among Dual-Earner Couples with Young Children.” Journal of Applied Psychology 106 (1): 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000857

- Szpunar, M., L. M. Vanderloo, B. A. Bruijns, S. Truelove, S. M. Burke, J. Gilliland, P. Tucker, et al. 2021. “Children and Parents’ Perspectives of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Ontario Children’s Physical Activity, Play, and Sport Behaviours.” BMC Public Health 21 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12344-w

- Thompson, J., G. Spencer, and P. Curtis. 2021. “Children’s Perspectives and Experiences of the COVID-19 Pandemic and UK Public Health Measures.” Health Expectations 24 (6): 2057–2064. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13350

- Tinnfält, A., K. Fröding, M. Larsson, and K. Dalal. 2018. ““I Feel it in My Heart When My Parents Fight”: Experiences of 7–9-Year-Old Children of Alcoholics.” Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 35 (5): 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0544-6

- United Nations. 1989. United Nations Convention on the Right of the Child. UNICEF. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx.

- World Health Organization. 2020. Considerations for Quarantine of Individuals in Containment for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Interim Guidance, March 19, No. WHO/2019-nCoV/IHR_Quarantine/2020.2.

- Zhao, Y., Y. Guo, Y. Xiao, R. Zhu, W. Sun, W. Huang, D. Liang, et al. 2020. “The Effects of Online Homeschooling on Children, Parents, and Teachers of Grades 1–9 During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research 26: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.925591.