Abstract

From different perspectives regarding the History of Economic Thought, the contributions to this roundtable highlight different aspects and levels of the modernity of the founder of the Austrian School of Economics, and of his importance for the development of social theory and the discipline of scientific economics. This is complemented by discussions of ambiguities and multiple meanings of modernity.

Carl Menger and the dialectic of modernity

Richard Sturn

But you will notice—and I have had it clearly emphasized in the drawing – that when you look at one of the groups of ideas now engaged in battle, it draws its supply of combatants and ideas not only from its own depot, but also from that of its opponent; you see that it continually changes its front and, quite without reason, suddenly fights with an inverted front, against its own stage; you see, on the other hand, that the ideas continually overflow, back and forth, so that you find them sometimes in one line of battle, sometimes in the other: In a word, you cannot draw up a proper stage plan, nor a demarcation line, nor anything else, and the whole thing is, to say with respect – which, on the other hand, again I cannot believe in! – what in our country any superior officer would call a pigsty!

General Stumm von Bordwehr in Robert Musil's “The Man Without Qualities”

Modernity had and still has its vicissitudes, shades, ambiguities, and ambivalences. As a historical epoch, it may be characterised as a cluster of multi-faceted developments occasionally epitomised as the “dialectic of enlightenment”, including various modern counter–movements of post- and anti-modernity. As a background condition of mental models and epistemic systems, modernism was associated with developments eventually culminating in currents of reactionary anti–modernism, where modern traits may be paradoxically combined with atavistic features: the achievements no less than the crises of the modern age set the scene for a variety of modern “thinkers against the current” (whose influence did not and do not remain confined to the realm of ideas) so vividly portrayed by Isaiah Berlin (Citation2013). Little wonder that General Stumm in Musil’s novel (a work conveying much of the tensions reflected in the Viennese brand of modernity which set the scene for Erwin Dekker’s (Citation2016), panorama of Austrian economists as “students of civilization”) complains in view of multiple intellectual polarizations related to modernism and anti-modernism “that of the famous people at your cousin’s, each one tells me something different when I ask him …, I’m already used to that,” … “but that when I’ve been talking to them for a long time, it seems to me as if they’re all saying the same thing, that’s what I can’t make sense of in any way, and maybe my military mind just isn’t enough for that!”

In midst of all those intricacies, Carl Menger is no doubt a modern thinker, un homme des Lumières, as Gilles Campagnolo stresses. However, “Menger’s modernity” reflects the fact that enlightenment cannot be considered a singular set of tenets or reduced to one unambiguous doctrine free of tensions: for instance, Menger’s modernity is associated with taking on board reasonings on organically grown norms and institutions along the line of Burke-Savigny (a line which later should be famously elaborated by Friedrich von Hayek). However, as a modern thinker, he takes seriously the challenge of showing that this does not imply implausible anti-enlightenment exaggerations: i.e., conclusions according to which such organically grown institutions are always the last word in the progress of civilisation.

More specifically, a century after his death, “Menger’s modernity” can be understood in at least two quite distinct (albeit interconnected) ways, including a disciplinary and a super-disciplinary level: first, Menger dealt with important unsettled questions of political economy and thereby contributed and still contributes to the evolution of economics as a scientific discipline, since some of the pertinent issues (including Austrian themes such as the role of knowledge in society and its implications for economic mechanisms and institutions) were greatly stimulating research ever since. Important achievements notwithstanding, some of those Austrian themes are unsettled to this day, as exemplified by the economics of knowledge and its evolution in the context of the digital transformation. This also applies to issues such as agent heterogeneity and the way in which out-of-equilibrium processes are to be integrated in economic analysis. It illustrates some ways in which a sense of unfinishedness (sometimes attributed to Menger) may be considered a virtue rather than a vice in the evolution of socio-economic theory.

In spite of Menger’s role in the evolution of economic knowledge (whose institutional development as a scientific discipline is a notable characteristic of the modern age), his thought indeed does not fit into a conception of linear modernity with steady progress. A Whig history of economic analysis will hardly do justice to him. Notice that this failure of a Whig approach applies in both directions: as Heinz Kurz argues in his contribution to this special issue, it applies to the way he dealt with classical authors. In that respect, Menger’s achievement is not properly characterised as “improvement” in the sense of linear progress and incremental refinement of the inherited body of disciplinary knowledge. However, it also applies to the (often roundabout, indirect, and fragmentary) way in which “modern economics” has digested his contributions.

Second, at a super–disciplinary level, Menger’s modernity is quite specific among the varieties of modernity. Menger is a pioneering protagonist of the Viennese “students of civilizations” aptly described by Dekker (Citation2016). Dekker characterises their approach as follows: they thought of themselves primarily as scholars dedicated to studying conditions, mechanisms and processes sustaining “their” bourgeois–liberal civilisation whose institutions should be cherished by improving them (e.g., by preventing or mitigating their negative effects, such as mass poverty, as Menger Citation1994, explains in his Lectures to the Crown Prince Rudolf), rather than as protagonists of a science eventually providing the basis for socio–economic engineering. This is related to influences à la Burke-Savigny. Over and above that, it converges with the program of Adam Smith’s Scottish enlightenment in at least two respects: the antitechnocratic thrust culminating in Smith’s (Citation1790, TMS VI.ii.2.17–18) criticism of the “man of system”, and the overarching quest for “understanding” highlighted by Nicholas Phillipson (Citation2010). Both concerns are related to the challenging task of developing a constructive role for “the science of the legislator” while acknowledging the importance of spontaneously emerging patterns and structures brought about by human action, but not by human design – and the related polycentric dynamism jeopardising the efforts of centralist technocratic reformers whose scientific “systems” fail to accommodate this polycentrism. This was a challenge in the time of Smith and Menger, and it is an even greater challenge in the epoch of climate change and the digital transformation: today, diagnoses and technological developments are clearly more science-dependent than ever before, while the contradiction between “science-based” technocratic policy approaches and populist voluntarism may culminate in antagonistic struggles. Economics as “the science of the legislator” is a crucial part of those developments. As put by Colander and Freedman (Citation2019), modern “economics went wrong” since it largely abandoned the “firewall” between theory and policy implied by John Neville Keynes’s influential conceptualisation of economic policy as an “art”. Whether or not the metaphor of a firewall is suitable for characterising the problems of science-politics interfaces, Colander and Freedman certainly have a point: no less than in Smith’s, Menger’s, or Keynes’s time, economic policy is still an “art”, one that requires an awareness of the polycentrism of socio-economic dynamism, the heterogeneous principles of different societal sectors, and conflicting interests.

In a related respect, Menger’s modernity can be better understood by locating him in coordinates used for distinguishing between varieties of liberalism by Jacob Levy (Citation2014). Levy discusses the pros and cons of two kinds of liberalism marked by the poles of rationalism and a kind of “pluralism” associated with cherishing spontaneously grown institutions, including their diversity. As Levy points out, this “pluralism” historically included some degree of acceptance of “local” norms, which more often than not are insolubly intertwined with power asymmetries, exploitation etc. Like Levy, Menger and Smith are aware of the merits of the arguments supporting the “pluralist” pole. Both contributed a lot to understanding its socio–economic background. And both are sceptics regarding comprehensive centralist–technocratic planning. However, Menger’s measured discussion of “pragmatic” institutions (paralleling Smith’s qualified statements with regard to reasonable improvements), their view of the role of collective institutions (from clubs to states) in promoting enlightenment, and their position with regard to core policy issues of their time are illustrating that they are far away from making a cult of the wisdom embedded in traditional institutions, or a cult of the unknown and unknowable, let alone of the “therapeutic nihilism” fashionable in Vienna for some time during Menger’s life.

Menger was a modern thinker who cherished the culture of enlightenment. With his complex background including various German, Scottish, and Aristotelian influences, he was the representative of a kind of modernity accommodating restless change as well as the plurality of organically grown social phenomena (we may imagine some difficulties of Musil’s General Stumm in deriving straightforward answers). However, as implied by a line of the conversation alluded to by Gilles Campagnolo, reasoning à la Menger may have its finest hour when multiple crises are around the corner. This presupposes taking seriously the structural conditions underlying those challenges, which culminate in recurrent crises of liberalism and liberal orders. Those crises reflect the vicissitudes of liberalism: it then appears as a system of the best answers to the main problem of modernity and “great societies”. However, liberalism may also degenerate, for instance into a complacent ideology for rent–seekers whose protagonists (as some of the participants of the Colloque Walter Lippmann have pointed out, among others; cf. Audier 2012 20) are blind to cumulative catastrophes, rendering a caricature of the enlightenment ethos of impartial truth–seeking and understanding.

In some respects, a nuanced view of Menger’s modernity involves both the disciplinary and the super-disciplinary level. We may agree that his economics may not be well equipped with some of the theoretical resources necessary for dealing with the developments and circumstances relevant for addressing major economic problems of technological modernity (a point raised by Heinz Kurz). However, as Gilles Campagnolo’s focus on individualism and tolerance reminds us, modernity also coevolved with individualism, subjectivism, and new forms of pluralism. In view of such cultural modernity, it seems, Menger’s theory is much better equipped, or at least offers a more promising starting point, not least in comparison with Anglo–Saxon approaches that rely on the one–dimensional metric of utility, which in certain respects avoids dealing with the problems of heterogeneity by abstracting from heterogeneity. Menger’s talk of needs and desires is less abstract, including discussions of underlying epistemic and contextual conditions. Unfortunately, his ambition to develop this line of thought in a scientific way by taking on board the more psychological work of the “Second Austrian School of Value Theory” inspired by Franz Brentano did not lead to broadly visible achievements.

However, the Viennese origin of some theoretical developments important for the understanding of modern politico–socio–economic environments (including Schumpeter’s theorisation of socio-economic change) is no coincidence. There are two starkly different examples, both illustrating the extent to which Menger’s thought addresses unsettled questions. First, what was commonly viewed as the Mengerian branch of the “marginalist revolution” accommodated approaches (developed in the works of Friedrich von Wieser, Emil Sax, and Menger, e.g., Citation1923) towards a genuinely individualist theory of communal needs and wants as well as public agency, rendering the activities and services provided in this sphere (some of which are irreducibly communal) commensurable with market–based economic valuation. The ways in which this approach can be made fruitful in theories of public sector institutions, non-market mechanisms, and polycentric governance still offer considerable challenges for future research.

Second, as Sandye Gloria stresses, Mengerian economics has been an inspiration for complexity economics. Erich Streissler has pointed out long ago that equating Menger’s economics with “Austromarginalism” fails to do justice to his work. Somehow paradoxically, the marginal principle is posited in a way which could (and would) be perceived as centre stage, but at the same time it also appears as a principle to be surpassed. This has often been emphasised by Erich Streissler (Citation1972) and other authors for whom the main contribution of Menger’s economics consists in his subjectivist vision of the economy and its epistemic conditions rather than in marginalism as such. It may be left open to which extent and in what sense constructing a theory of complex economic phenomena is part of Menger’s research program. However, subsequent developments including Alfred North Whitehead’s “process philosophy” allow for an association of Menger’s specific focus on “unsettled questions” connected with market processes and their co-evolving institutional embeddedness with a vision theory of complex phenomena in the economic sphere.

Put another way, a distinctive characteristic of Menger’s economics is that it elevates a cluster of unsettled questions to a salient status by which it could stimulate subsequent discussions and subsequent developments – unsettled questions to which the research program of complexity economics may be considered a response (perhaps the scientifically most elaborated response). While a detailed discussion of possible Mengerian inspirations and impacts on complexity economics (let alone their contextualisation within the combination of different influences) is beyond the scope of this note, we may observe that Menger’s economic thought either includes or is at least open towards important ideas that play a role in complexity economics modelling: e.g., that

interaction between (possibly heterogenous) agents is dispersed;

competitive mechanisms provide some control and coordination, complemented by a plurality of mediating norms and institutions

the polycentricity of modern socio–economic systems is at odds with models of centralised controlling mechanisms, auctioneers, or planners.

Such a setting (and the mode of thinking and analysis associated with it) is open – more open than other theoretical settings – for the emergence of innovations, new markets, new technologies, new behaviours, and new institutions. It conceptualises the relation between equilibrium and out–of–equilibrium dynamics in a different way: equilibrium is not obsolete, but it is not the Alpha and Omega of the explanatory perspectives of the theory, implying that out–of–equilibrium processes/dynamics are a key to understanding some of the specific characteristics of modern capitalist market societies.

As indicated above, Menger’s thought does not fit into a Whig history of economic analysis. Should we, then, think of it as (part of) a revolution, a development fuelling a wave of paradigmatic innovation, or an epistemic rupture – or as a milestone in the development of economics as a multi–paradigmatic science? Some plausibility notwithstanding (his position in the “battle of methods” against historicism and his explicit distancing from Walrasian general equilibrium theory seem to reflect a multi–paradigmatic attitude), all these perspectives have major problems of their own, discussion of which is clearly beyond the scope of this note. Perhaps Menger’s role can be understood along the lines of Schumpeter’s (Citation1926) metaphors characterising the evolution of economics: He compares it to the growth of a tropical forest, with exuberant flourishing in possibly unexpected regions, dead wood accumulating in others, where progress happens in a criss–cross fashion. Taken together, the contributions to the present roundtable indeed offer significant illustrations for that.

Carl Menger, “Homme des Lumières”

Gilles Campagnolo

1. Menger and supra-disciplinary concerns in the face of two present-day crises

Why do I say “homme des Lumières” in French? Because the French version of Menger’s seminal masterwork was made available for the first-time last year, in 2020, in my own translation with presentation, notes and commentary. French is the only major language of science in which this came so late; it is a paradox with Menger in France that it took so long for his work to be made available and become known. There are reasons for this within the history of French currents of thought related to liberalism. I have written elsewhere on this (Campagnolo Citation2006, Citation2018). Let me provide here a quick recap of the fate of the founder of the Austrian school in France, as this may be of interest to the audience of this round-table.

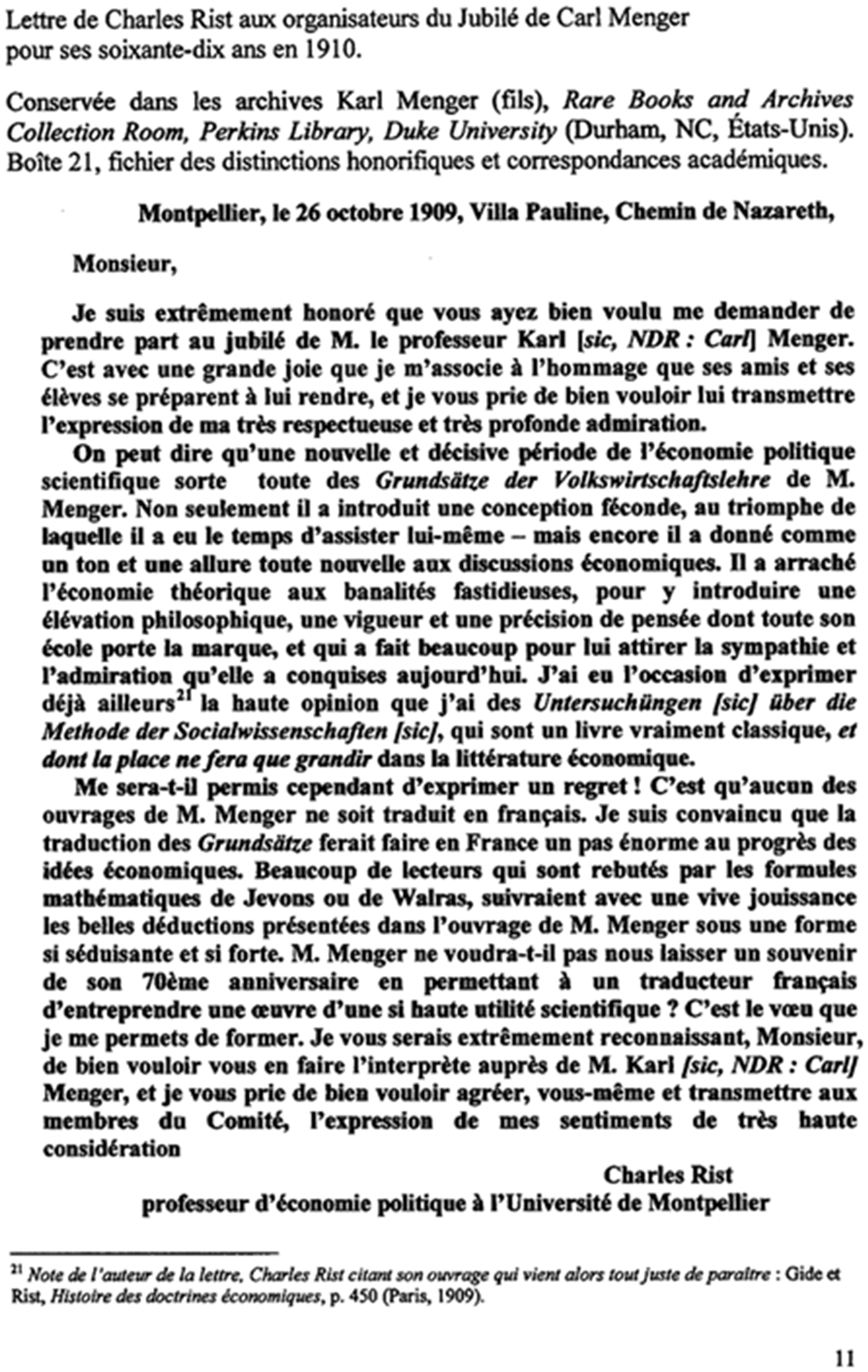

Let us note that during his lifetime, Menger was known to French academia: he was made a corresponding member of the Académie des scicences morales et politiques after Wilhelm Roscher’s death. The fact that Menger was chosen by the French Académiciens rather than Gustav Schmoller from Berlin, the heir to the Historical School and leader of German economists, was probably related on the one hand to the upheavals of history in Europe (the memory of 1870 Franco-Prussian war to start with), and on the other hand to the easier relationship that existed at that time with Austria, which was also a victim of the developing German Second Reich. Certainly, French academia was aware of the disputes within German-language academia and the surge of the Austrian School’s confrontation with the German Historical School. A French translation of the 1871 Principles was devoutly desired, as a letter dated 1909 by Charles Rist (reproduced below in Appendix A) shows. However, this was not achieved and one consequence of this absence was that Menger’s influence almost disappeared thereafter in the French science-scape. Here, then, is Menger: a fairly well-known thinker within French academia in his own times, but who later became relatively unknown in France, despite being considered a major author internationally right up to the present (cf. Campagnolo Citation2006, Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2018).

One positive side of having Menger available now in French is that we may rediscover his works, his thoughts, and the man himself as an author with contemporary relevance, a contemporary author for us in FranceS.Footnote1

What, then, makes Menger modern? I intentionally leave aside the fact that there was a major shift in the history of the Austrian School, from Central Europe (Mittel-Europa) to the Midwest (of the United States), during the twentieth century. Americanised Austrian economics is, in my view, an altogether different story, that probably well deserves attention itself, but I will skip this here to focus on Europe.

At present, we are facing two major crises. One crisis is epistemological, and is fifteen years or so old. It is, in essence, related to the financial crisis and the series of economic breakdowns and rebounds, from the 2008 financial crash up to the present-day economic consequences of the COVID pandemic. It is a crisis of what economics is about and it impacts science itself, as well as mainstream economics, through various attacks; indeed, it may be surprising that there are not more changes within the economics profession (there are “not enough” according to some critics, “too many” according to mainstream defenders). There could be more. Now, this could be a chance for Menger’s theory and ideas from 150 years, as paradoxical as it may seem, to gain momentum if used wisely to clarify some of the topical issues at stake, be they theoretical or methodological, keeping in mind an ideal free individuality.

The second type of crisis I would like to stress is thus related to the first, as it is the global crisis of liberal ideas. I deploy the word “liberal” in the way we Europeans understand it – to mean pro-liberty, pro-free-trade, for instance – and not the American use that relates “liberals” to what we tend to call the “progressive camp”. Incidentally, the American use is not foreign to us, since it is fundamentally the meaning that word had in the mid-nineteenth century in Europe, around the European Spring of Revolutions in 1848. The specifics of the notion have evolved somewhat in Europe, while its original meaning has essentially been retained throughout in US-English parlance. There is indeed a crisis of liberal ideas, as there was in the 1930s (with a war-like situation to the fore in both cases, naturally).

Now both crises intertwine. This reminds us of past times in Europe, but it is also our reality today. The re-building of liberal thought – that is to say, thinking in terms of liberty and the role and place of the individual and individual liberties – calls for the Austrians. Except that, the American "neo-Austrian" school of thought, so to speak, has much evolved by inserting Mengerian views into the very different frame provided by specifically American concerns and the specifics of the school have shifted as a consequence, making the US view quite peculiar. Therefore, one has to return to the European origins and to the founder. This is where Menger is useful. Menger’s relevance to modernity lies in the fact that he offers us tools that help us not only to understand the technicalities of present-day economics. Of course, his views do serve well at a notional level and still apply in many regards to fields that change over time, such as search theory, information theory, product innovation, agency theory, market process and the role of time. But, more generally speaking, they can help to solve the larger crises in the science of economics and with respect to liberal ideas, both induced by the upheavals of our times.

Again, in the French context, in 1938 the Colloque Walter Lippman held in Paris played such a role. There could be a similar agenda for a Mengerian-inspired doctrine to develop for the benefit of rehabilitating and possibly “re-vamping” liberal thinking. This could be one good reason to emphasise the modernity of Menger today, and what his doctrine may do for us in our present world, at, say, a “supra-disciplinary” level, besides technicalities. I stress this aspect now so as to answer the request put forward in Richard Sturn’s remarks, as I shall develop further elements at disciplinary level in the following two interventions, that is to say how to reassess a basis for individual subjectivity and economic, moral and political philosophy that sustains individual freedom, rather than tending to suppress it. Why is it necessary to remind ourselves of this priority of individual freedom, when many either take it for granted or discard it, so as to bury themselves in technical elements that necessarily depend on the passing of time and the emergence of more recent economic theories? Because, if the aforementioned crises that we are facing are general (climate change, biodiversity loss, and so on), they bring with them the temptation to take refuge in other notions of so-called “original” communities and groups: whatever we conceive those to be, they discard the individual. Whether we are happy with this, or how much constraint such a backlash to older demons, so to speak, may bring, remains unclear. However, it is clear that if liberty has any meaning, then it relates to the place and role of the individual. And that is what Menger stressed.

2. Menger warns us against set agendas and pushes us to think like economic philosophers.

Once again, what brings us together in this roundtable is that we stand 100 years after Menger died and 150 years after he published his Principles. When Menger began this work, he regarded it as merely an introduction to a larger work; however, he set himself a task that would become increasingly hard to fulfil as science continued to develop. In Citation1871, Menger provided a book that was, in his own view, incomplete. There was a second edition in 1923, but even this likely diverged from what Menger originally wanted, as it was done by his son whose intellectual background (that would lead him to the Vienna Circle) was somewhat different. Moreover, he didn’t use most of his father’s archives for that purpose.

Therefore, even if Carl Menger’s views had been accepted – rather than violently opposed, at the time of the original 1871 edition – by the German Historical School, it would have become increasingly difficult for Menger, as time passed, to develop a project as large as his. Consequently, how could we imagine that we might simply resume where he left off, 150 years ago? His modernity obviously lies within an adaptation to our times, based upon his most basic notions: subjectivity, methodological individualism, the spirit of liberty and resistance to constructivist abusive thinking, as Hayek would stress later on.

Some commentators, together with some speakers in this conference, stressed how much had been accomplished before and after Menger on those issues as well. But let me stress that it is one thing to evoke some point in passing and to get to the point and open a new field. It is always possible to find predecessors to any author and to any idea almost. It is even our job as scholars to find that kind of sources or insights. As a consequence, is it acceptable to say that “nothing is ever new under the sun”? No. Was Menger on time, uncertainty or subjectivism new? Yes. Let me make a comparison that I find in my own background as a philosopher. By analogy, the fully-fledged notion of “self-conscience” (Ego, Ich in German, the “self” in its reflexive dimension) could be regarded as not new with Descartes, if one recalls that the cogito had previously been heralded, as Pascal pointed, by Augustine. This is factually correct and intellectually, so to speak, erroneously presented: Augustine mentioned the term in passing and did not see the realm of thought it opened, while Descartes did. And Descartes thus brought philosophy to its native land (according to Hegel). The same may be said regarding Marx about history, at least in the understanding that Marx “opened a new continent”, as French philosopher Louis Althusser had put it. Well, Menger opened the land of subjective individualism for the social sciences, and economics in particular, as the title of his Untersuchungen goes (the Investigations into the Methods of Social Sciences).

Even to make something out of a critique that can be suggested (that is to say to select between what is dead and what is alive in Mengerian thought, as, for instance, the Italian philosopher Gentile did regarding Hegel/Marx), one must return to the origins so as to find the “real” Menger, or at least the “real” version of his book, taking into account the annotations that he put into the copy sent by his publisher, Wilhelm Braumüller, which had blank pages for that purpose. This quasi-archaeological work is useful for better understanding further developments, including those of recent and/or contemporary authors who claim to be “Mengerian” in some way. Whether they truly are the “children” or “grand-children” of Menger is a less interesting question than a discussion of why the work that follows Mengerian insights makes sense and can be useful besides the historian/archaeologist’s work. There are some paths that have been mentioned in this conference, and others also exist.

How are they possible at all on the basis of a work dating back more than a century? Because Menger marks a divergence. The divergence is between the paths that have been opened by his disciples over time, in a plurality of directions, and the mainstream one that has come to dominate economics to such an extent that it presents itself as the science of economics in general. This occurred due to the mathematizing of economics: since mathematics is accurate by construction and tractable by definition, the pretence is that it can be the whole of the field. With Menger, other openings exist – and they can be furthered, even now. One may mention complexity (cf. Campagnolo and Tosi Citation2016), but it has to be defined, detailed in its peculiarities: we cannot just repeat the word like a mantra: it has to be substantiated. The issue of discontinuity as a tipping point in economics is also at stake in these times of crisis, and indeed, as Menger rejected the purpose of building theories in view of equilibrium, his understanding of disequilibrium may be mobilised. There is room for Mengerian views: this is one way that Menger can be useful today.

Another way, which brings us back to the supra-disciplinary and bird’s eye approach I developed in Part I, relates to pro-free trade currents of thought. Whether there is a program to develop or not, the issue is always whether one intends, by interfering with the course of exchange, to become (or to avoid being) the advocate of views promoted by avowed interests; this may refer to interest groups (the many lobbies/Interessengruppen but also societal divisions by race, class, gender, religion, etc.) or more general concerns claiming “superior” goals (such as gods, or "nature" when discussing biodiversity). Then scientists tend to become what Menger disparagingly called “Advokaten”, some sort of particular-oriented mind, because in their eyes this is the valid standpoint, one that is more efficient, more protective of such-and-such an interest, saving us from this or that “evil”. It is not good to see science become ancillary.

Moreover, far from solving issues altogether, this usually creates other problems, likely to be even bigger. It doesn’t mean that laissez-faire is a solution, when it is presented just as one more of those recipes for the “betterment of mankind”. It does not mean either that Menger was in favour of laissez-faire, since he actually quoted Freihändler, together with Kommunisten and Kathedersozialisten, among the Advokaten he criticised. This warning only means that intervention is not necessarily the best course of action. To take it inevitably induces unexpected outcomes that may well bring more trouble than it was originally supposed to solve.

Such warnings can be inferred from Menger. This was the case with Keynes: there was the original text, and then diverging paths from his original theories to the interpretations. And then to the things that were said by others about them. Identically, various paths opened up from Menger onwards. The Austrian School itself has been just as diverse, leading to both reinterpretations and criticisms. Who cares about “orthodoxy” in schools of thought? It is only the claiming of legitimacy line of some genealogy: among Austrians, there are many, for instance, from Böhm-Bawerk to Mises in one direction, from Wieser down to Lachmann in another. Plurality is the key to better understanding, since intelligence is provided by pinpointing where currents differentiate, not where they resemble each other. This positive attitude inspires me to put another word on the table, one that sometimes scares away some of our fellow economists: “philosophy”, and especially “economic philosophy”. In a sense, the latter’s task is precisely to identify notions worth raising from within the practical activity of science, in other words, the fundamental tenets and concepts which underlie scientific theories, models and constructions and which may help foster essential issues (cf. Livet Citation2021).

In my view, Menger was a philosopher, and from that perspective, his thought is for all times: not only his own, but ours as well, especially in the current “post-post-modern” crisis. Menger can be summoned to provide ways to “do” not only economics, but philosophy. This is certainly not the case with all economists, but I hold that it is so in his case. Moreover, in the French frame especially, this notion was not developed but, rather unfortunately, largely ignored, as I stressed earlier. But to keep a philosophical mind aware, we may avoid putting forth any stand and instead suspend judgement, bringing issues more aptly under examination and rigorously questioning those who have an agenda, whatever this may be (intervention or the contrary, for that matter). Why and how do some pretend to put forth a particular agenda? Besides personal rationales, what is the implicit reasoning at stake in each case? Studying this aspect means freeing oneself from the fear that makes it appear compelling and from the urge to forcefully pretend to solve problems while potentially creating more of them. This goal is intrinsic to philosophical prudence and is a goal devoutly to be wished, I dare say.

3. Within the social sciences Menger opened the way to keep alive the role of individuality.

There should be no infringement of individual liberty, whether this comes from big government, big firms, public or private hierarchy, or whatever other kind of social control that may exist, especially as the gathering and manipulation of big data has invaded every area of life. We might ask, what was the German Historical School about if not exactly the same things (as manifested in those times), promoting hierarchies and bureaucracies – and what was Menger doing if not fighting them? Statistics is history told through numbers, and digitalisation is making this at present available in the same manner, albeit through AI and contemporary computer techniques. The means have changed, and technology provides fearsome powers today, but the essence is identical: no individual is spared. This is what Menger fought against within the field of theory, in the name of the individual: no blind following of rules, zero tolerance for uniform and overall control over the individual.

Following some questions raised in the discussion, I shall conclude with two ideas.

Menger surfaced when the old socialism and old liberalism had revealed their limits. This was a major crossroads for Europe, for the world and for economic thought; Menger appeared at that moment to open the path towards the best account possible of individuality in the social sciences. His Citation1883 Investigations into the Methods of Social Sciences spread from Vienna, through the Austro-Hungarian Empire and all over Europe, from the German-speaking regions to the various academic spheres; this spread throughout Europe deserves attention in turn beyond the case of France. Menger’s influence was certainly felt across Europe among free thinkers and economists, as recent detailed studies show.

My viewpoint is different from that of Erich Streissler, who tended to describe Menger as a German economist, in sum. Indeed, theoretical parts of the Principles derived from the peculiar reception given to the works of Smith in Germany, where the Wealth of Nations was criticised from the time of its first translations. Streissler linked his analysis to the fate of Austro-Hungary facing the German Reich (defeated by Prussia at Königgrätz). Reflections upon the notion of value are core to Austrian economics, of course, but Austrian economists, notably Joseph Schumpeter, saw things differently and strongly claimed independence from the German School. The Methodenstreit bears witness to this and renders Menger and the rise of his school as central. In the twentieth century, the variety of paths that were opened then may have been concealed at times by disputes raised by the Austrians against all planners, socialists, Keynesians, etc. However, one should count the success of anthropological studies and the rise of “analysis in context” (with long term consequence) as putting an end to “pan-Germanism” and “Euro-centrism” as well, together with interest in early trade and empires through the cogs and wheels of exchange that Menger shared, as his archives show (together with Marcel Mauss, in France, for instance). Part of this came from basic schemes provided by Menger, and it could be said that Karl Polanyi illustrated those as much in his Great Transformation (1944) as Hayek in his Road to Serfdom. It would be precious for further scholarship to develop those lines.

As I have stressed Menger’s importance as a philosopher, a word on Menger and French philosophy may be in order here. Menger was well read in the French studies of his times and, indeed, some heirs of the Austrian School in the Neo-Austrian/American-Austrian School have at times raised the issue of subjective utility theory’s French origins, with good reasons to relate them to Menger as much as to early economists of the Enlightenment. And Menger was well-read in most of the production of the Europe of free thinkers of his times, as already mentioned.

One last word could be a date to wrap up the argument on the prevailing role of individual liberty: 1883 was the year Menger published Investigations into the Methods; it was also the year Karl Marx died, and the year John Maynard Keynes and Josef Aloysius Schumpeter – as well as Benito Mussolini – were born. The friends and the foes of individual liberty would build up camps for the confrontations of the twentieth century, and we would do well to remember the threats, as well as the hopes with regard to restraining, protecting and extending individual liberties. Within the social sciences the radical role of individuality was one path that Menger opened up.

Menger’s construction under scrutiny

Heinz D. Kurz

Il n’y a pas des problèmes résolus, il y a seulement des problèmes plus ou moins résolus.

(Henri Poincaré)

The theme of this conference in general and of this roundtable in particular is whether Menger’s works are still worth reading, whether his ideas still resonate with us, whether and to what extent his spirit permeates modern economic thought and what we can still learn from him today. Richard Sturn has set the stage by asking the panellists a number of specific questions. I will try to do my best in answering some of them as I go along, but I fear that I will only be able to scratch the surface. Menger set himself the difficult task of disclosing the laws shaping the behaviour of the economic system at different stages of the process of civilisation. He raised several intricate problems without fully solving any one of them, but he deserves credit for solving a few problems more or less.

1. Menger’s legacy

The Grundsätze (Menger Citation1871, English Citation1981) saw the light of the day a century and a half ago; its author passed away a century ago. His work would have been buried and forgotten, had there not been people who felt that it was important and worth preserving and at the same time incomplete and in need of correction and elaboration. John F. Kennedy’s famous phrase comes quickly to one’s mind: “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country!” Replace “country” by “Menger” and respond to the request. This will give you at least a partial answer to the theme of conference and roundtable. More specifically: What did scholars do since the publication of the Grundsätze so that Menger’s ideas still capture our attention today?

In my view, the best promotion of Menger’s legacy in economics consists in (i) taking him seriously and weeding out all arguments and concepts in his contribution that cannot be sustained; (ii) rectifying his reasoning whenever it is considered to be basically sound in substance, but problematic in form; (iii) identifying elements in his thought that are both genuinely original and valid, but whose full explanatory power still has to be developed; and (iv) comparing Menger’s explanation of economic phenomena with rivalling ones and form an opinion about what one can learn from each.

To trace modern developments in economics back to stimuli contained in Menger’s work raises an intricate problem of imputation, which, I fear, cannot be decided unequivocally except in a few cases. What can, however, be done is to draw the attention to how his work was received by major economists and what they made of some of its building blocks.

Menger’s former students, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk and Friedrich von Wieser, spotted shortcomings and flaws in his theory. Each in his own way sought to overcome these by means of alternative constructions. They were especially critical of the following elements in his doctrine: (a) His successivist reasoning – taking the prices of goods of first order as given and determining the prices of goods of higher order in terms of them. Clearly the two sets of prices are interrelated and have to be determined together with one another (Wieser). (b) His theory of production and capital – holding on to a unidirectional concept even with regard to industrial production (Wieser) and failing to elaborate a theory of the general rate of profits (interest) and the factors affecting it (Böhm-Bawerk, Wieser). (c) His treatment of the “imputation problem” – taking for granted that a solution exists without ever investigating under which conditions this is in fact the case (Wieser). (d) His radical subjectivism – denying the impact of objective elements (physical real costs) on relative prices and income distribution (Böhm-Bawerk, Wieser). (e) His criticism of the labour theory of value – failing to see that relative prices are proportional to relative labour values in well specified circumstances (Böhm-Bawerk, Wieser).

In their attempts to remedy what was seen to be faulty in Menger’s construction, the two economists proposed changes, some of which implied that salient methodological and theoretical principles upon which his construction rested were abandoned. Wieser’s contributions, in particular, showed that correcting Menger did not leave the substance of his reasoning unscathed. Here are some of the most important changes suggested by the two – plus developments in economic theory more generally that throw some light on Menger’s theoretical edifice.

2. Menger’s construction put to test

(1) Simultaneous vs. successivist approach

Many authors rejected Menger’s successivist approach to the problem of value and distribution and advocated instead a simultaneous one that conceives of production as a circular process instead of a one-way avenue from original factors of production via some intermediate products to consumption goods. Menger (and also Böhm-Bawerk) abandoned the circular viewpoint, which had been advocated by François Quesnay and the classical economists. Menger therefore overlooked the possibility that one and the same type of good may be used both as a consumption good and as a capital good at different stages of the time-phased conception of production. This however undermines Menger’s idea that the prices of goods of higher order could be determined in terms of the given prices of goods of first order. At the same time, it throws into doubt his naïve causal-genetic perspective and his insistence on consumer sovereignty. Lacking a proper concept of system of production, Menger failed to see the implications this has for the set of all non-negative price vectors compatible with the system. This failure comes into the open when he obstinately insists against the classical economists that the physical properties of commodities, the “substances” they represent, play no role whatsoever in the theory of value and distribution.

Production systems may, of course, exhibit hierarchical structures, but these are better captured in terms of sophisticated versions of the classical distinction between “necessaries” (consisting of means of sustenance of workers, or wage goods, and produced means of production) and “luxuries”. While the former are indispensable in production, the latter are not. Sraffa (Citation1960) distinguishes between “basics” and “non-basics” of various kinds: the former are needed directly or indirectly in the production of all commodities, including themselves, whereas the latter are either not needed at all as means of production or only needed in a subgroup of non-basics.

(2) Ordinal vs. cardinal utility

While some interpreters attribute to Menger an ordinal concept of utility, there is, in my view, clear evidence that he held a cardinal one. Here it suffices to point out that a thoroughly subjectivist approach to value and distribution appears to me to be difficult to reconcile with the idea that utility is measurable and interpersonally comparable.

(3) Interrelatedness of consumption

Menger contemplates situations, in which new goods (or better qualities of known ones) continuously, but slowly enter the economic system, while some known goods exit from it. He is clear that this involves the generation of new needs and the demise of old ones. Unfortunately, we learn not all that much about what are the driving forces of this change, its speed and direction, how it is brought about, how it affects the productive apparatus, and how individuals adapt and adopt what is new and abandon what is old. Adam Smith in The Wealth put forward an interesting argument concerning the interrelatedness of the consumption patterns and life styles of people belonging to differently wealthy groups, which revolves around positive and negative demonstration effects. The poor try to imitate the rich, while the rich try to differentiate themselves from the poor. With rising levels of income per capita in both groups, the rich are incessantly on the lookout for new and more expensive pleasures and excitements in order to set themselves apart from the advancing less well-offs, who in turn desperately try to stay close on the heels of the rich and glamorous.

Such consumption dynamics are inherent in societies characterised by significant inequalities of income. They cannot occur in societies as Menger contemplated them, populated by “isolated economizing individuals” (100 [133]), Robinson Crusoes, who are “merely [concerned with] a relationship between certain things and men (3n* [52n4]). This exclusive concern with relationships between man and objects comes as a surprise, given Menger’s admiration of Aristotle to whom the human being was a zoon politicon. What matters is to understand the relationship between humans and humans. (We come back to this below.)

(4) Socioeconomic history seen as a single process

Contemporary followers of Menger acclaim especially his concern with two interrelated facts: the time-consuming nature of all economic activities and the necessity to plan and act into an uncertain future. Decisions and actions therefore often turn out to have been erroneous, based on an insufficient perception of the factors affecting their outcomes. While this is undoubtedly true and certainly worth taking into account, some readers appear to have missed the teleological message of Menger’s Grundsätze. Menger, as John Hicks observed perceptively (see Kurz Citation2022, in this issue), conceives the socioeconomic history of mankind as a “single process” of the accumulation of knowledge. In the course of this process, Menger insists, false ideas, misconceptions and superstition, and therefore “imaginary” needs and goods lose in importance, whereas “true” needs and goods capable of satisfying them are on the rise and with them more and more productive technologies to produce them. In short, humans are taken to gradually increase their control over the planet and themselves. Like many other writers at the time and across ideological divides, Menger, too, held a rationalist faith in human progress. Interestingly, a quarter of a century earlier Friedrich Engels saw the way towards a worldly paradise paved by the enormous rise in labour productivity due to the inventions of scientists, and Marx saw the era of a society without exploitation dawning, in which humans finally succeeded in the “appropriation of all essential human powers”.

In conditions in which technological change is modest and steady, uncertainty is low, markets are well organised and prospective costs and revenues can be calculated with a high degree of certainty, a system of cost-minimizing or “economic prices” will obtain, which Menger also called “effective”. In such conditions the economy can be seen as progressing via a succession of what Menger explicitly dubbed states of “equilibrium” (136n, 172–174 [159n, 191–192]). Therefore, while I agree with scholars who reject the view that Jevons, Walras and Menger form a relatively homogeneous group of marginalist revolutionaries, Menger is perhaps much less the odd man out than is frequently maintained. In particular, what several of Menger’s followers cherish most in his contribution is least present in what he writes about advanced stages of civilisation. In Menger we do not encounter the homo economicus of neoclassical theory, fully informed about the present and all future states of the world and capable of carrying out within a fraction of a second the most intricate problems of the calculus of pleasure and pain. But, as I read him, he was not opposed to the view that equilibrium configurations of economic variables may, in advanced civilisations, be considered reasonable approximations of the truth. The problem, however, is that his own construction exhibits many loose ends and is too opaque to ascertain, what the equilibrium properties of the economic system in given conditions look like.

Not all scholars shared the rationalist faith in human progress. An important exception was Max Weber, who wrote:

[T]he growing process of intellectualisation and rationalisation does not imply a growing understanding of the conditions under which we live. It means something quite different. It is the knowledge or the conviction that if only we wished to understand them we could do so at any time. It means that in principle, then, we are not ruled by mysterious, unpredictable forces, but that, on the contrary, we can in principle control everything by means of calculation. (Weber Citation2004[1917], 12–13)

This implies, Weber emphasised, the “disenchantment of the world” (13).

(5) Stability

An unstable equilibrium, Alfred Marshall was to insist, is of hardly any use whatsoever. Menger appears to have simply taken stability for granted and made no effort to investigate the conditions under which it obtains. Today we know, thanks to the works of Rolf Mantel, Gérard Debreu and Hugo F. Sonnenschein in the 1970s, that stability of economic equilibrium, as portrayed by the Arrow-Debreu model, cannot be proved under sufficiently general assumptions. (In the following sub-section we turn to a very strong assumption which, if met, entails stability.) At this point it should be mentioned that long-period marginalist theory has come under attack from a “classical” perspective (Sraffa Citation1960) in the controversies in the theory of capital. Phenomena such as reswitching, reverse capital deepening and price and real Wicksell effects undermine marginalist theory and the postulated stability of equilibrium. For an assessment of the capital controversies and their implications for economic theory, see Kurz (Citation2018).

For a long time, it was wrongly thought that what Jevons called the “Law of Demand” would be enough to guarantee stability. The “Law” postulates an inverse relationship between the price of a good (or a factor service) and the quantity demanded of it, and is illustrated in terms of a downward sloping demand schedule in the now conventional Marshallian price-quantity diagram. (It deserves to be mentioned that Antoine-Augustin Cournot and Karl Heinrich Rau had put forward the concept of a demand schedule a few decades before Jevons see Chipman (Citation2005, Citation2013).) The law was taken to apply both to the demand of single agents and, via horizontal aggregation, to the collective demand in an entire market. In the Grundsätze, when illustrating his argument, Menger assumes throughout that the law of demand holds true (e.g., 237–238), by implicitly invoking the ceteris paribus assumption. In this case the law is indeed plausible, which explains its high credibility amongst laymen, but also economists. However, as soon as one realises that one cannot change the price of a single good or factor service in isolation, but has to allow for compensating changes in some other prices, which will in turn necessitate further changes and so on that will reverberate through the entire system, the plausibility of the law vanishes. The quantities and prices of some products need not be inversely related. In the case of a change of the wage rate, it is immediately obvious that the ceteris paribus clause makes no sense.

When the German general equilibrium theorist Werner Hildenbrand was confronted with the findings of Mantel, Debreu and Sonnenschein regarding the properties of excess demand functions in an exchange economy, he was “deeply consternated”, because up until then he had been a victim of the “naïve illusion” that the microeconomic foundations of economic theory were sound. Hildenbrand (Citation2014[1994]) then showed that collective demand functions typically do not preserve the properties of individual demand functions, derived on the basis of the usual rationality axioms in consumer theory. He then investigated the conditions under which the aggregation of given individual demand functions confirms the law of demand.

Hildenbrand’s approach still follows the premise of methodological individualism according to which the part should be considered as constitutive of the whole, and not the other way round. However, once it is admitted with Adam Smith that decision-making is often interpersonal, we enter a different world, in which phenomena such as contagion and herd behaviour often play an important part. Heterogeneous-agents-based models seek to replicate analytically what can happen in such circumstances – the conditions under which society will, for example, stay relatively homogeneous or in which it degenerates into several sub-groups, each characterised by its own views and rules of conduct and so on. (For a most interesting application of multi-agents modelling, see Alan Kirman’s Graz Schumpeter Lectures (Kirman Citation2010).) Economists now learn, for example, from the swarm behaviour of fish or bird populations. These developments cry out for a new conceptualisation of the “individual” and its “autonomy”. The “economic man” – the focal point of much of contemporary economics – has to be recast.

(6) Towards full information

In Menger we do not find much in this regard. But he forebodingly at least partially anticipates a condition that has to be met in order for the economic system, as seen by general equilibrium theory, to be stable: agents must be possessed of perfect information, not only about their own situation (preferences, endowments), but also about that of all other agents in the economy. This Menger appears to have sensed somewhat. As soon as society reaches a “certain level of civilization”, he emphasised, agents “naturally acquire a very obvious interest in being informed not only about all the goods in their own possession but also about the goods of all the other persons with whom they maintain trade relations” (47 [91]). Better information, he added, increases the accuracy with which future economic states can be “calculated” (45 [89]).

Hence, while it would be wrong to identify Menger’s reasoning with the neoclassical model of perfectly informed rational agents possessed of infinite computing capacity, it can hardly be denied that some of his reflections may be interpreted as pointing in this direction. This appears to be confirmed also by the following important fact – Menger’s endorsement of Sir Isaac Newton’s “law of cause and effect”.

(7) Cause and effect

The following passage is prominently placed right at the beginning of the main text of the Grundsätze and serves as a signpost for the rest of the book: “All things are subject to the law of cause and effect. This great principle knows no exception, and we would search in vain in the realm of experience for an example to the contrary” (1 [51]). Menger thus embraced what to Newton was the very foundation of physics – the principle of causality. According to it the present determines the future. “Human progress”, Menger was convinced, “has no tendency to cast it in doubt, but rather the effect of confirming it and of always further widening knowledge of the scope of its validity” (ibid). He was keen to develop his economic theory in full recognition of the fundamental principle of Newtonian physics. As is well known, this was also the credo of major marginalist (neoclassical) authors who propagated to mould economics in the image of Newtonian mechanics.

The question is close at hand: Would Menger have felt the need to thoroughly revise his construction, had he been exposed to the path-breaking developments in physics at the beginning of the 20th century: relativity theory, quantum mechanics and Werner Heisenberg’s uncertainty relation. Other economists tried to adapt to the new findings. It suffices to mention Alfred Marshall, whose Principles of Economics, published in 1890, had as a motto “natura non facit saltum” (expressing the principle of continuity generally endorsed by marginalist economists), while in Industry and Trade, published in 1919, he softened it half-heartedly to “natura abhorret saltum”, which is, of course, an entirely different proposition. Heisenberg disputed radically the principle of causality by arguing that we can only know either the precise position of a particle in space or the speed of it, but not both. To the contention, “If we know precisely the present, we can calculate the future”, he objected: What is wrong is not the second part, but the first one – we simply cannot fully know the present. He rejected Newton’s clockwork universe and was critical of the adoption of the principle of cause and effect in other subjects, including philosophy, anthropology and economics.

Not all major physicists adopted Heisenberg’s radical position. Einstein even attempted to disprove the uncertainty relation, but failed. The questions that followers of Menger today will have to answer in this regard are the following: First, should economics still follow Menger’s dictum and respect the most advanced findings in the sciences and especially in physics? Secondly, what do modern developments in physics imply for Menger’s construction?

3. Concluding remark

Let me conclude by recalling Ilya Prigogine’s conjecture: “In all fields, whether physics, cosmology or economics, we come from a past of conflicting certitudes to a period of questioning, of new openings. This is perhaps one of the characteristics of the period of transition we face at the beginning of this new century” (Citation2005, 69).

Carl Menger’s coherent research program

Sandye Gloria

Modernity is a qualitative, not a chronological, category.

Theodor Adorno

I take up the challenge of suggesting, after Heinz Kurz's provocative intervention, one aspect of Carl Menger's modernity. However, I modify the terms of the debate. I do not think it necessary to start from an attempt to remedy what is seen faulty in Menger's construction. First because what is faulty is a matter of interpretation; consider just two instances of issues raised by Heinz Kurz: Böhm-Bawerk’s attempt to build on Menger is considered by the Austrian founder as one of the greatest errors ever committed in economics rather than an improvement; stressing the supposed unsolved issue of stability in Menger stems from a peculiar lecture of Menger which considers the market process as a linear process of knowledge discovery. And second, because the modernity of an author can reside in the still not fully explored potentiality of a suggested system of thought.

1. Modernity as providing a coherent research program

My position as regards the modernity of Carl Menger goes beyond the disciplinary view suggested by Richard Sturn in his introduction. But it is not a postmodern interpretation of the author either. Of course, I can identify issues in Menger that have become prominent much later and which he somehow addresses with his own arguments, in particular the consequences of uncertainty and imperfect knowledge on human agency. However, I think that Menger’s modernity is to be found elsewhere. Nor does it consist only of one particular original aspect of his thought, such as his treatment of time, his theory of organic institution or capital. We had the opportunity to see at the occasion of various presentations during this conference that maybe there was nothing genuinely new in Menger’s way of dealing with time, subjectivism, uncertainty. So, to what extent could we insist on the modernity of the author? I will argue that his modernity lies in the organisation of all these elements of originality (at least original as regards marginalism) into a coherent whole paving the way to further treatments of those hitherto unsettled problems he raised.

So, the author’s modernity does not consist of one or several of any analytical elements taken per se or isolated from one another. His modernity lies in the organisation of these elements in a coherent framework. This was precisely the strength of Walras’ writings: to provide a coherent theoretical pattern. The same holds true for Menger, but he offers an alternative pattern that had not been really deepened by his followers. Some aspects of the Mengerian framework have been picked up again but in isolation, such as the idea that production takes time by Böhm-Bawerk, his theory of money which inspires search theory and so on. There is however one exception.

To me, Ludwig Lachmann is the only author who genuinely built upon the Mengerian logic as a whole. We all know the famous quotation from Hayek according to which progress in economics is a further step in the development of subjectivism. Menger provides the first step in the development of subjectivism in economics with his emphasis on the role of human needs in economic evaluations and decisions. The second step consists in defining individual plans as a subjectivist means-ends framework continuously reshaped by the discovery of knowledge in the course of economic competition as Hayek puts it. Lachmann tackles the task of extending subjectivism to expectations, this is the further step in the development of subjectivism. This endeavour, already present in nuce in Menger who analyses the economic activity of the entrepreneur as caring in advance in order to meet consumers’ requirements in the future, has overwhelming consequences for economic analysis: it allows for taking into account the full dimension of the creativity of the human mind. In an open world of permanent changes, there are no reasons why expectations should be correct or converge. The theory of the market process associated with subjective expectations leads to a different outcome than the Kirznerian equilibrating one. The market process is a process with no terminal point, unfolding towards a direction which is unknown to the participants but also to the theorist. Were the analysis to end here, Lachmann’s theory would appear rather disappointing and legitimately subject to the criticism of theoretical nihilism.

However, we can consider this theory not as a dead-end but as the starting point of new investigations. How? Lachmann gives a twofold orientation for further research that echoes again Menger’s insights.

First, he suggests enriching the theory of the market process with a theory of institutions understood as points of orientation in a world of radical uncertainty. Lachmann discusses then the question of the coherence of an institutional set-up with requirements of stability and flexibility which allows for the coordination of individual decisions.

Second, from an epistemological point of view, Lachmann suggests redefining our standard of what constitutes a good scientific explanation. And his answer is very similar to Menger’s conception of understanding. Instead of trying to elaborate one highly abstract theory of the market process, the ambition of theorists may be reduced to proposing various theories of the market process, representing a variety of ideal-types of markets according to the identified institutional setting, with the objective of understanding their dynamics in terms of meaningful individual interactions.

2. The constituent parts of this coherent research program

William Jaffé denounced in Citation1976 the harmful consequences for progress in economics of the process of homogenisation of the Mengerian thought within the Walrasian framework: the risk of homogenisation would be that the theoretical potentialities of Mengerian originality would remain unexplored for a long time.

If one approaches Menger from Jaffé’s perspective, that is to say as an original author rather than as a technically constrained marginalist, one can only be struck by the coherence of his alternative vision of economics. Ontology, epistemology, methodology and key concepts are harmoniously intertwined in the Mengerian approach, offering a coherent alternative pattern with potentialities to present-day economists to investigate.

Let me detail briefly how these four parts form a potentially modern research program.

(1) From an ontological point of view

The question here is: what is the nature of the economic reality analysed by Menger? The world in which Mengerian actors evolve and interact has little in common with that of Walrasian optimisers. Menger depicts an open reality rather than a closed mechanical world; a world where changes occur continuously as the result of individuals’ creativity, where the unfolding of time modifies individual plans and the outcomes of interactions are unexpected. Genuine novelty is indeed possible in the Mengerian world. The ingredients of this particular vision of reality are thus creativity, time and uncertainty.

The starting point is that economic action takes place over time. O’Driscoll and Rizzo (Citation1985) confront the Newtonian conception of time, adopted by marginalists following the logic inherent in the analogy with mechanics, with the Bergsonian conception, which highlights the subjective and discontinuous nature of time for economic agents in the Mengerian framework. Economic decisions, in Menger’s view, take place in real time in the sense that the passing of time is itself a source of novelty, in so far as it modifies the information and knowledge upon which agents base their means-ends framework. We identify in this particular relationship between time and knowledge the ultimate foundation of the Austrian specific ontology. It has been expressed explicitly by Lachmann (Citation1986, 95) as an Austrian axiom: “[t]ime cannot elapse without the state of knowledge changing”. Economic reality is continuously unfolding as time goes by, propelled by individual interactions based on evolving knowledge; the passing of time changes individuals’ perceptions of their environment, agents continue to gather information and modify their plans in unexpected ways.

(2) At the epistemological level

The question at stake here concerns the nature of the scientific endeavour. What is the correct posture of the economist in trying to understand economic reality? What is a correct scientific explanation?

Menger’s scientific approach is purely analytical and consists of breaking down complicated economic phenomena into their simplest elements, a logical decomposition in terms of the relations of causality. The scientific approach, which aims to acquire a general knowledge of phenomena, consists of systematic research of ultimate causes, which are the very essence of these phenomena, by establishing general laws with a universal character. Understanding an economic phenomenon means identifying the causal process which brings it into being, starting from its most elementary cause—the economising principle—to the most complicated manifestation of the phenomenon under analysis. To Menger, the aim of economic analysis is to identify the sequence of changes that brought the phenomenon into being.

Menger's specific epistemological stance is made explicit by one of his disciples who underlines the contrast with the marginalist posture. Hans Mayer (Citation1932[1995], 57) distinguishes between two types of approaches to the theory of prices formation: genetic-causal theories which, “by explaining the formation of prices, aim to provide an understanding of price correlations via knowledge of the laws of their genesis”, and functional theories which, “by precisely determining the conditions of equilibrium, aim to describe the relation of correspondence between already existing prices in the equilibrium situation”. Clearly, Menger does not follow a functional approach. He rather applies a genetic-causal approach not only to the understanding of prices but to all the economic phenomena he studies, including money, production, market, the State and so on. Menger’s ultimate analytical goal is made explicit in the Untersuchungen where he explains that most economic phenomena are similar to organic institutions, that is, to structures that emerge without a common will directed towards their establishment; the most important question in theoretical economics is how to understand the nature of and changes to these structures. By understanding, Menger means identifying their origins and the causal processes of change that lead to their occurrence. In this perspective, in modern terms, he endorses a generativist epistemological stance.

(3) At the methodological level

The methodological consequences of the ontological and epistemological characteristics of the Mengerian conceptual pattern directly concern the nature of the relevant mathematical tools.

Tools should be coherent and adapted to the scientist’s investigative method and conception of the nature of reality.

From an epistemological point of view, marginalist tools do not permit an understanding of economic phenomena in Menger’s sense;

from an ontological point of view, the kind of mathematical tools available to Menger and used by his contemporaries were not adapted to his vision of economic reality as an open system. In that sense, mathematical tools are not neutral and Menger’s adoption of the mathematical tools of the marginalists would have been totally incompatible with his approach.

Once the theorist’s aim is to understand the process of emergence of a phenomenon through causal decomposition into its primary elements, formalisation as a system of simultaneous equations is inappropriate since it ignores the sequence leading to the formation of the phenomenon and focuses exclusively on the ultimate outcome of the process. The development of the Walrasian program goes hand in hand with the adoption of ever more sophisticated mathematical tools of a specific kind, formalist tools – formalist in the sense of Hilbert – and axiomatization.

Formal tools favour the establishment of theorems, of purely syntactic formal systems, adapted to the functional approach described by Mayer. The Mengerian genetic-causal approach focuses on the process, on the course of interactions and the appropriate mathematical tools are different in nature. But what kind of tools more precisely?

Epstein (Citation2006, 1587) highlights the correspondence between the generativist point of view and constructivist-type tools, such as numerical simulations and multi-agent modelling.

(4) Core concepts

In an open, processual conception of reality coupled with a generativist approach, there is no sense in focussing on end-states. Equilibrium loses its primacy. The process itself becomes the object of investigation and emergence replaces equilibrium as the core concept.

We find in Menger’s writings the idea that the fundamental question to be addressed by social scientists regards the explanation of the emergence of phenomena. In that perspective, Menger’s theory of institutions is not anecdotal or secondary but central to his reasoning. Menger’s interest in institutional phenomena logically follows from the genetic-causal perspective.

Like other economic phenomena, economic institutions such as exchange, markets, the state and money are analysed by causal decomposition, to grasp the essence of their nature and thus to identify the ultimate causes that engender them. Understanding the process that leads to the emergence and evolution of institutional economic phenomena legitimately becomes a central question of economics as Menger sees it.

Menger's explanation of the emergence of money constitutes the typical example of the genetic explanation, in terms which prefigure evolutionary economics, thus testifying to the modernity of an analysis which continues today to inspire numerous authors (cf. Latzer and Schmitz, Citation2002).

No comparable analysis can be found in Walras, who instead focuses on the optimal characteristics of a monetary system intended to ensure justice in the functioning of the economy. In other words, the object of investigation is different: to the question "how is money introduced?" Menger responds by identifying the process of its emergence, while Walras starts from the endpoint and adopts the functional point of view, consisting of identifying the optimal monetary system which allows social justice, i.e., uniqueness and price stability. Emergence vs equilibrium.

3. Conclusion

Menger's approach in all its originality and consistency fits perfectly within a coherent conceptual pattern. Therein lies his modernity:

In the coherence of this conceptual pattern: his conceptual pattern coherently articulates his particular view of the economy as an open process with a genetic-causal approach that consists in focussing on processes in order to explain phenomena; the mathematical tools should be adapted to such an endeavour and clearly functional mathematics are not a good candidate for investigating the essence of phenomena in Menger's sense; instead of targeting the analysis at describing the properties of end-state situations, the task of the social scientist should be oriented towards understanding, in this generativist sense, how social regularities—organic institutions—emerge out of individual decentralised interactions in situations of limited knowledge and uncertainty;

in the potentialities of this conceptual pattern: if Menger and his earlier followers could not count on the availability of the right tools, this is no longer the case today with the development of a realm of constructivist techniques such as multi-agent modelling that perfectly fit the epistemological requirements of the Mengerian conceptual pattern;

in the compatibility with the approach of complexity: as argued elsewhere (Gloria Citation2021), the Mengerian pattern echoes the ontological, epistemological, methodological and conceptual dimensions of the complexity approach. The economy is apprehended as an open, processual reality, with genuine novelty emerging continuously from the interaction of decentralised individual heterogeneous agents in an ever-changing environment they contribute to shaping. Simulations rather than theorems facilitate an understanding of the global properties of this adaptive process.

Not only does Menger provide theoretical elements that prefigure complexity analysis, but he organises them into a coherent conceptual pattern of his own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See also Campagnolo (Citation2020).

References

- Audier Serge. 2012. Le Colloque Walter Lippman. Paris: Le Bord de l’Eau.

- Berlin, Isaiah. 2013. Against the Current. Revised ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Campagnolo, Gilles. 2006. “De Carl Menger à Karl Menger – à Charles Menger? sur la diffusion de la pensée économique autrichienne.” In Autriche-France: transferts d’idées/histoires parallèles?, Review Austriaca, edited by U. Weinmann, Vol. 63, 133–150. FNAC.

- Campagnolo, Gilles. 2008. Carl Menger entre Aristote et Hayek: aux sources de l’économie moderne. Paris: CNRS Éditions.

- Campagnolo, Gilles. 2009. “Origins of Menger’s Thought in French Liberal Economists.” The Review of Austrian Economics 22 (1): 53–79. doi:10.1007/s11138-008-0055-3.

- Campagnolo, Gilles. 2018. “From Karl Menger to Charles Menger? How Austrian Economics (Hardly) Spread in France.” Russian Journal of Economics 4 (1): 8–23. doi:10.3897/j.ruje.4.26001.

- Campagnolo, Gilles, editor. 2020. L’école autrichienne d’économie nationale. Full Special Issue. Review Austriaca 90. Available online at https://journals.openedition.org/austriaca/996

- Campagnolo, Gilles, and Gilbert Tosi. 2016. “La conception organique des institutions de Menger a-t-elle anticipé ce qu’est un système adaptatif complexe?” Revue d'Histoire de la Pensée Économique 2: 41–71.

- Chipman, John. 2005. “Contributions of the Older German Schools to the Development of Utility Theory.” In Studien zur Entwicklung der ökonomischen Theorie, edited by Christian Scheer, 157–259. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

- Chipman, John. 2013. German Utility Theory: Analysis and Translations, Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Colander, David, and Craig Freedman. 2019. Where Economics Went Wrong. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Dekker, Erich. 2016. The Viennese Students of Civilization: The Meaning and Context of Austrian Economics Reconsidered (Historical Perspectives on Modern Economics). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316411162.

- Epstein, J. 2006. “Remarks on the Foundations of Agent-Based Generative Social Science.” In Handbook of Computational Economics, edited by Leigh Tesfatsion and Kenneth Judd, Vol. 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier.