Abstract

We examine parallels and differences, intersections and complementarities in the notions of societal transition by Karl Polanyi and Joseph A. Schumpeter. Considering their intellectual heritage, methodology and scope, we propose a three-sphere framework to analyse their theories and study the interdependencies within capitalism. The three spheres essential to both thinkers are the political, the socio-cultural and the economic: the latter dominates the others in capitalist societies. The resulting rationalisation (Schumpeter) and commodification (Polanyi) distort the socio-cultural sphere and transcend towards the political sphere which undermines democracy. Applying our framework, we identify similar transitional mechanisms but derive different implications for society.

JEL CLASSIFICATION CODES:

1. Introduction

Karl Polanyi and Joseph A. Schumpeter are arguably two of the greatest thinkers of the 20th century. Not only did their works shape their respective fields, but the two contemporaries also continue to enhance our understanding of societal change to this day. While Schumpeter is primarily known for his concepts of innovation and creative destruction, Polanyi’s ideas gained popularity in recent years thanks to his critique of the (neo-)liberal free-market ideas and their political implementation. Although less of a focus in recent contributions in the history of economic thought, both contemporaries emphasise the processes of societal change and transition.Footnote1 Both had a similarly dynamic vision and critical analysis of the societies they experienced and the relation of liberal democracies and capitalism more generally. The evaluation of this relation continues to be of relevance today: Polanyi already pointed towards the willingness of corrupt elites to tolerate populist and fascist tendencies in order to protect their economic and political interests. In a similar vein, Schumpeter refers to market-like election processes resulting in political opportunism and suggests an epistocractic bureaucratism instead. These overlaps indicate that a comparison between the two provides a better understanding of the relation between capitalism and democracy and the dynamics in societal transitions. Inexplicably, the connections between Polanyi’s and Schumpeter’s oeuvres have hardly been explored in the history of economic thought literature – with some notable exceptions (Harvey and Metcalfe Citation2004; Özel Citation2018). Harvey and Metcalfe (Citation2004) link Polanyi’s and Schumpeter’s perspectives on markets and find that Schumpeter viewed the evolutionary power as originating from within the market system whereas Polanyi considered the organisation of the market system as the driving force for transformation. Özel (Citation2018) discusses the common philosophical base of Schumpeter and Polanyi alongside Marx and Weber. Remarkably, comparisons of Schumpeter’s thinking with other authors are more common, e.g., Veblen (Schütz and Rainer Citation2016; Papageorgiou and Michaelides Citation2016), Sombart (Chaloupek Citation1995) and Keynes (Kurz Citation2012). Connections between Polanyi, Hayek and Keynes (Polanyi-Levitt Citation2012), Polanyi and Streeck (Lloyd and Ramsay Citation2017) and Polanyi and Weber (Maurer Citation2017) have also been examined in the literature. Since the intersection of societal transition in Polanyi and Schumpeter has not yet been analysed to the best of our knowledge, we study the parallels and differences, intersections and complementarities between the writings of Karl Polanyi and Joseph A. Schumpeter.

More specifically, we concentrate on Polanyi’s opus magnum The Great Transformation (TGT) of 1944 which offers a compelling historical account of societal transformation culminating in fascist moves all over Europe. Societal change is portrayed as a radically transformative process that was set in motion by the utopia of an all-encompassing self-regulating market affecting political and cultural realities alike. Throughout the paper, we follow a “hard” interpretation of Polanyi and employ a large-scale term of “embeddedness” (Dale Citation2010) and tend to abstract from the historical context which Polanyi is describing, leaning towards a post-Polanyian reading (Holmes Citation2014, Citation2018). For Schumpeter, our main focus is on 1942s Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (CSD) which provides a more abstract and analytical discussion of the workings of capitalism. He describes a capitalist society’s evolution towards Schumpeterian socialism which has little to do with more commonly used notions of socialism due to technocrats and elites presuming power. We primarily consider Schumpeter’s analysis of late capitalism and assume the Schumpeterian mark-II-model of oligopolistic competition (see Andersen Citation2011) to apply.

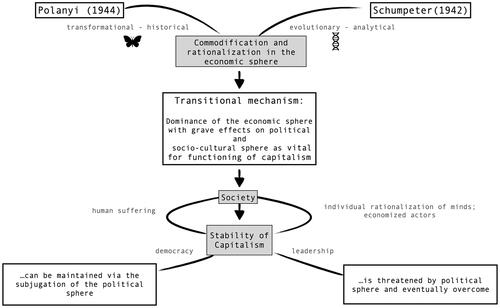

We first consider the two thinkers’ respective backgrounds with regard to their socialisation in Vienna, their choice of methodology and the scope they choose for their analysis. Accordingly, we characterise Polanyi’s approach as transformational-historical and Schumpeter’s as evolutionary-analytical. Then we introduce a three-sphere framework as both Polanyi and Schumpeter implicitly refer to different spheres of society in their work: the political, the economic and the socio-cultural. By applying this spheres framework to Schumpeter’s and Polanyi’s accounts of a transitioning society, we identify mechanisms of transition. While they are similar, they are not exactly congruent and can at times even complement each other. Whereas the rationalisation stemming from the economic sphere plays an important role for Schumpeter, Polanyi’s focus is more on the commodification of labour and other fictitious commodities. Our analysis shows that rationalisation and commodification essentially rely on similar dynamics but attribute a different degree of plasticity to human nature; by this, we mean the degree to which human nature is adaptive to societal transitions and institutional change. Accordingly, we derive different implications for the quality of transition and the overall stability of the capitalist system from the comparison of Polanyi and Schumpeter.

2. Backgrounds

Polanyi’s (Citation[1944] 2014) TGT and Schumpeter’s (Citation[1942] 2003) CSD were first published in 1944 and 1942, respectively. The Austro-Hungarian Empire had fallen apart in World War I and after a short intermezzo of socialists and democrats in Red Vienna and the Weimar Republic in Germany, fascist tendencies had been on the rise in Europe. The context in which both works were written was thus a time of great disruption and political instability which is reflected in both authors’ thinking. Schumpeter and Polanyi both were born into middle-class entrepreneurial households in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire and were part of to the intellectual upper middle class.Footnote2 Later, both were actively involved in interwar period politics in Weimar Germany, the crumbling Austro-Hungarian Empire and its successor states.

Growing up in Moravia (now: the Czech Republic), Schumpeter moved to Vienna in 1901 to study NationalökonomieFootnote3 and was strongly influenced by the contemporary debates and key figures at the University of Vienna. Among the most important influences were representatives of the Austrian School (e.g., Carl Menger and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk) who further engaged in the famous Methodenstreit in the 1880s. Although Schumpeter shares the dynamic conception of capitalist markets with other Austrian thinkers, he clearly differs in his methodological approach: Schumpeter advocated for theory-building and historical observation to be seen as complementary rather than opposing elements for the analysis of social phenomena (Kurz and Sturn Citation2011).Footnote4 Theories of elite leadership were particularly influential in Schumpeter’s intellectual development as advanced by several of his contemporaries, among them Friedrich von Wieser and Alfredo Pareto (Kurz and Sturn Citation2011). Schumpeter shares the notion of an adaptive mass that is continuously perturbed by the disruptive impulse of an energetic leader, the entrepreneur.Footnote5 After World War I, Schumpeter joined the German Socialisation Committee in Berlin for the German Weimar Republic to discuss the future course of the nation with liberals and Marxists.Footnote6 In 1919, he briefly joined the German-Austrian government as a finance minister.

Polanyi was born in Budapest and joined the military of the Austro-Hungarian Empire working as an officer in World War I after having already been involved with Hungarian politics (Congdon Citation1976). After the war, he moved to Vienna and worked as an editor and journalist whilst, together with his wife, becoming part of the socialist intelligentsia of Red Vienna at the time. In the Methodenstreit, he defended the historical position which he would also later apply methodologically in TGT: He describes the rise of capitalism as an overthrowing of historically existing social relations and a. consequent erosion of social cohesion. TGT also reflects his strong belief in community building and social institutions for a functioning human coexistence. The successes of Red Vienna in building social protection and a strong, intellectual working class greatly impacted Polanyi’s view on the transformative potential of political activism among the civilian population (Dale Citation2016). Throughout his life, he was dedicated to politics, but in comparison to Schumpeter’s political position as an academic and policy maker, Polanyi was more confident in intellectual debates and political activism.

The following years of economic depression and Austrofascism led to increasing pessimism among intellectuals. Influenced by these political and intellectual shifts, both authors dedicate themselves to the study of transition and the inherent dynamics of capitalism. In their works, both put strong emphasis not only on the economic but also on the social and political implications of capitalist development and analyse the interactions of these. They both describe how the destruction of the feudalist institutional order by political forces – intentional in a Polanyian, more concomitant in a Schumpeterian sense – preceded the rise of the capitalist system and the related rise of nation states. A crucial difference between the two lies in the distinct focal points of their analyses: Polanyi strives to explain the rise of fascist tendencies by the forceful implementation of market principles whereas Schumpeter aims to integrate his thoughts on the dynamics of capitalist processes into a general theory of overall societal evolution. To achieve these different ends, the authors chose different methodological approaches and their scopes differ in terms of the temporal dimension and the level of abstraction. Polanyi’s TGT is a historical account of societal transformation from 19th to 20th century capitalism. His main intention is to offer a historically conditioned explanation for the rise of fascism in Central Europe. Polanyi clearly refers to a defined and limited period of time which narrows his scope accordingly: the rise and fall of a market economy that is based on implementing a self-regulating market assuming self-interested individuals. Polanyi argues for the embeddedness of the economic aspect of life, emphasising that it is subject to customs, norms and beliefs. Since markets and market-related behaviours have historically always been embedded in the social fabric of society, he considers the idea of a self-regulating market that requires rational, self-interested individual behaviour utopian. Polanyi’s account of human behaviour is fundamentally opposing the rational, self-determined homo oeconomicus (Hejeebu and McCloskey Citation1999) since he views human behaviour as being socially embedded yet determined by a pattern of social organisation. Forms of integration (Polanyi Citation1992) like reciprocity and patterns of social organisation that support these forms are at odds with behaviours required by self-regulating markets. By the active and forceful implementation of a self-regulating market, the economic sphere is gradually disembedded from the social. This divide fundamentally contradicts his view on human nature and thus creates resistance and the need for self-protection in the population. Polanyi emphasises that assuming self-interested individuals on a self-regulating market has an actual and oppressive effect on human nature, particularly once the economic sphere is disembedded.

In contrast to Polanyi, Schumpeter’s main interest lies in the analytical question of if and how capitalism can survive. For his answer, he constantly strives to abstract from normative value judgements and possible external influences to identify actual patterns and regularities of 19th and 20th century capitalism. His main focus is to expand his general theory and increase the precision of his analysis. CSD is the last in a series of previous complex analyses of the economy: Schumpeter’s aim here is to analyse the capitalist development as a whole, and to integrate his theory of the dynamic economy into a broader picture of societal co-evolution in different spheres. His analysis is based on the fundamental discrepancy between two different characters who perform distinct functions in the process of evolution. The innovative entrepreneur induces change in the system to which an inert majority simply adapts.Footnote7 From this dynamic concept of creative destruction in its broadest terms, he derives that society itself must be subject to change at some point. In the course of capitalism, social norms and institutions are undergoing permanent adjustment. Schumpeter assumes human nature as a rather individualistic element and explicitly states these assumptions for the purpose of analytical clarity in his model of overall socio-economic evolution. This does not necessarily imply that the development of capitalism should be seen as an ahistorical event.

In conclusion, both authors view the development of capitalism as interactive between individual behaviour and institutional environment: Schumpeter focuses on the dynamics of innovation and adaption, whereas Polanyi emphasises the distinctiveness of 19th-century market logic in trying to separate economy and society. However, they differ in their scope and in their choice of methodological approach. Polanyi’s scope is narrower in focussing on a distinctive time period by giving a historical account of societal transformation. Schumpeter’s scope is much broader, especially with regard to the economic sphere. Methodologically, he pursues the integration of his evolutionary economic model into a broader, still abstract model of societal evolution. Our comparative study of the two is consequently limited by the diverging accounts. By focussing on important parallels and differences in both works, we do not give a full account of Schumpeter’s oeuvre – especially with regard to his more sophisticated theory on economic development – due to the limitations of Polanyi’s narrower approach. Similarly, we also abstract from the historical processes addressed by Polanyi such as his monetary theory reflections on the departure from the gold standard but focus on processes within and between spheres in both theories. We highlight the interconnectedness of individuals and institutions in the course of capitalist transition and point to aspects in which Polanyi’s critique of self-regulating markets diverges from Schumpeter’s wider general analysis of the capitalist system.

3. Analytical framework

Despite their diverging backgrounds, aims and approaches, we argue that both Polanyi’s and Schumpeter’s theory of transition can be analysed and partly synthesised using our framework. For both Schumpeter and Polanyi, society consists of roughly three spheres: the economic, political, and socio-cultural. Pertinently, neither Polanyi nor Schumpeter develop an explicit, comprehensive notion of a sphere system they both implicitly refer to. While the distinction of spheres is not always clear-cut and consistent, we believe that understanding their approaches through this lens allows for discovering differences, similarities and even complementary aspects.

Society in a Schumpeterian sense (Andersen Citation2011) can be described as comprised of several spheres, sectors, or realms: the economic, the political, the scientificFootnote8 and the family realms. Social norms are rooted in the latter (Andersen Citation2011). Polanyi specifically mentions the separation of economic and political life and clearly references the cultural surrounding of humans. The socio-cultural sphere subsumes both the latter and Schumpeter’s family realm. While both authors use the term “spheres” at some point in their works, they do not necessarily stick to it consistently throughout and operate with other terms vaguely referring to the same idea, too. For our analytical purposes and better comparability, we choose to follow this terminology and apply our system of spheres to both CSD and TGT.

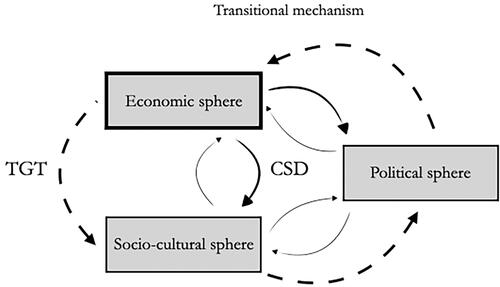

Although distinct to some degree, the three spheres are inseparably interconnected. All three spheres impact each other to an extent; however, our framework suggests there is a hierarchy of spheres and influences within them. Potentially, each sphere could be dominant, but in order for capitalism to function, the economic needs to be in a prevalent, if not leading, position. We therefore conceptualise the relations of the spheres as presented in , separate and equally important, but not identically influential and powerful. The direction of impacts is not perfectly identical for TGT and CSD; nevertheless, the interconnectedness of all three spheres is characteristic for both thinkers.

This framework allows us to compare TGT and CSD despite the different backgrounds, intentions, and focal points of the authors. By design, the implementation of a framework like ours is an abstraction from the original theories as well as a tool that necessitates simplifications. For the sake of analytical comparability and comprehensiveness, we have to accept certain limitations. However, those limitations do not weaken our argument that, firstly, the three spheres we identify are relevant in both theories with, secondly, the economic sphere being dominant compared to the political and socio-cultural spheres in capitalism. In a sense, such a structure is essential to capitalist societies for both Schumpeter and Polanyi. As soon as the dominance of the economic sphere is threatened, the capitalist system stops working as intended until the necessary hierarchy is restored. The way to restore that order has certain aspects in common for both thinkers but is not necessarily the same.

Starting from a capitalist system, Schumpeter (Citation[1942] 2003, Citation[1934], 2004) understands societal change as an evolutionary process during which the economic sphere plays a central role. The development processes in non-economic sectors have some analogies to developments in the economic sector, identified by Schumpeter as an alternation of static adaptation and processes of development and innovation. Even though no causal directionality can be derived from his theory, statements about the process of development and specific characteristics of the economic domination are attainable (Schumpeter, Citation[1934], 2004). As said, all spheres interact with each other in a co-evolution of spheres – the overall outcome being the socio-cultural evolution. Not only do economic circumstances change as a result of this evolution, but also the normative conception of the economy and society evolve. In capitalism, the economic sector is inevitably dominant. Since rationality is a crucial component in the economic process, it influences the other spheres and changes the mode of social life by imposing a “rationality dictate” onto them. Together with the changing economic circumstances, this brings about the evolution from capitalism to a Schumpeterian socialism, which is reflected in a re-organisation of societal and economic principles.

In TGT, Polanyi discusses the institutionalisation of what he calls a liberal utopia: the self-regulating market. He argues that the economic sphere was historically embedded in society and therefore subject to customs, norms, and moral beliefs. However, for the self-regulating market to work, regulations, rules, or laws undermining those customs, norms and moral beliefs are needed. These regulations turn labour, land, and money – although bearing no commodity character at all – into so-called fictitious commodities enabling a self-regulating, free market “[eating] away human relations” (Hejeebu and McCloskey Citation1999, 288). Additionally, a “self-regulating market demands nothing less than the institutional separation of society into an economic and a political sphere” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 74). This institutional separation is also referred to as the disembeddedness of markets from society in contrast to a market that is embedded in and regulated by social norms and institutions. Commodification and competition are the core components for the market mechanism to work, but do not agree with the nature of labour, land, and money; instead, they evoke cultural degradation. Out of this tension of commodification and disembeddedness, the infamous countermovements arise. These political movements fight back against the pressure of the self-regulating market and the dominance of the economic sphere. Ultimately, this can result in fascist political movements and political systems as Polanyi describes for the example of Germany during 1933–1945.

As we said, both authors implicitly use some notion of societal spheres in their analyses which makes their theories flexible enough to be applied to societies in various stages of their transition. However, they appreciate different aspects of the approach: while Schumpeter emphasises its inherent character and analytical benefits, Polanyi sees the distinction of spheres more critically and regards it as an institutionalised result of the disembedded economy. This contrast can be interpreted as complementary views of a similar concept. Partly, the authors’ different conceptions of the plasticity of (inherent) attributes and behavioural traits in human nature allow for different perspectives on societal spheres and their interactions. Schumpeter (Citation[1942] 2003, 202) views humans’ “propensity to feel and act” as well as their behaviour as formable “while the fundamental pattern underlying [the very essence of human nature] remains” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 202). While the quote refers to humans more generally, it is important to acknowledge Schumpeter’s differentiation between the adaptive masses and entrepreneurs. While we cannot be certain about his ultimate view of the plasticity of human nature, his descriptions in CSD tend to support a more individualistic view of humans, especially of entrepreneurs who are driven by their desire to innovate and hence disrupt.

Polanyi, by contrast, sees no such distinction between a formable and a definite part of human nature and does not discriminate between individuals of a society either. He seems to interpret human nature as given by the social fabric of society, particularly with regard to the social ties resulting from it; however, he does not explicitly discuss his perspective on human nature at length in TGT, but rather alludes to it by referencing behavioural patterns, needs and desires of individuals and groups within society. In Polanyi’s view, humans tend to be inherently social beings and collectivist although he mainly uses “collectivist” in a rather sarcastic manner and with inverted commas or the qualifier “so-called” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 150, 169). To summarise, both Polanyi and Schumpeter acknowledge the interdependence of social structure and individual action but emphasise different aspects on the spectrum of interdependence.

Starting from this different conceptual base of human nature, both authors derive slightly different processes of societal change. Moreover, the degree of determinism in transition is related to the assumed degree of plasticity of human nature. In Schumpeter’s evolutionary view, individuals adapt to changing circumstances over time. Therefore, certain degrees of freedom remain in the overall outcome of an indeterministic, evolutionary process. Polanyi interprets humans as inherently collective and the process of changing structures as interaction of individual needs and collective movements. Their approaches again can be regarded as complementary. Polanyi’s rather deterministic view on transformation allows for some spontaneous elements (e.g., in the form of reactionary or emancipatory countermovements) and Schumpeter’s interpretation of evolution has some destructive parts (e.g., creative destruction in innovation processes). This further highlights the insights that can be gained from a comparison of the two theories. summarises our analysis of transition by illustrating their transformational-historical and evolutionary-analytical approaches in a simplified and stylised manner. The next chapter deals with the contextual dimensions presented in the figure.

4. Analysis of transition: the spheres in action

This section deals with the heart of our core argument, namely striking similarities of the mechanism of change in Schumpeter and Polanyi despite differences in their backgrounds and intellectual approaches. In order to make our point we will briefly outline the thinkers’ understanding of competition and, more broadly, the change in the economic sphere that they refer to as rationalisation and commodification, respectively. These central concepts act as the transmitter of change via the socio-cultural sphere. Subsequently, we discuss the impacts on the socio-cultural sphere where humans’ moral beliefs, social norms and cultural surroundings are situated. The impacts on the sociocultural sphere then spread to the political sphere; lastly, the effects on the stability of capitalism and democracy are accentuated.

4.1. Rationalisation and commodification

In their paper about Polanyi and Schumpeter and their understanding or critique of markets, Harvey and Metcalfe (Citation2004, 9) argue that for Schumpeter “the source of change [is] intra-market endogenous” whereas for Polanyi it is “market organisation endogenous”. This statement allows us to establish our argument since it again reflects the methodological backgrounds as well as the scope of the two theories. Although their positions seem to be contradicting at first, they share a lot of common notions and lines of argument.

In both cases, competition plays a central role and is detrimental to the respective transmitters of change: commodification and rationalisation. Since Polanyi is invested in showing the impact of the self-regulating market on society historically, he discusses the origin of markets’ dominance and the origins of markets themselves. The transformation of long-distance and local markets into big national markets clearly marked a departure from the time before and can be viewed as an instituted process. Especially in his essay on “The Economy as Instituted Process”, Polanyi (Citation1992) emphasises the notion of human structures: specific forms of behaviour like reciprocity, redistribution, house-holding or exchange and patterns of social organisation supporting that behaviour (symmetry, centricity, autarchy and the market pattern, respectively). The new social structure in capitalism brought about a new supporting pattern: the market pattern. Markets as meeting places “for the purpose of barter or buying and selling” (Polanyi Citation2014 [1944], 59) and the motive of barter have preceded capitalism but used to be just one possible mode of interaction and had no “automatic tendency to widen” (Hejeebu and McCloskey Citation1999, 291). The market pattern is more specific than the other patterns and, unlike them, creates an institution with a specific, single purpose: the market. This, in turn, allows the market to be made the dominant form of interaction, such that social relations must adapt to the economic system. The implementation of a self-regulating market can be regarded as a fundamental and intentional transformation of organisational principles within society. However, the transformation was made necessary by the “artificial phenomenon of the machine” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 60) that consisted in “the invention of elaborate and therefore specific machinery and plant” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 78) and culminated in the factory system. This required that all production factors involved in production be “on sale” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 78) and available at all times, including labour, land and money.

The motive of gain is particular to the production for markets and profits can be obtained “[…] only if self-regulation is safeguarded through an interdependent competitive market” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 78). A self-regulating market is characterised by its ability to administer production and distribution via buying and selling, i.e., by the reliance on prices, without external governance. For the smooth functioning of the price mechanism, (perfect) competition is essential: it ensures the existence of one price only (Altreiter et al. Citation2020). This further implies that incomes are derived from sales on the market and that no interventions are to distort the price mechanism. Society, including the political and socio-cultural sphere, needs to be subordinated to the laws of demand and supply – along with the production factors, labour, land and money. Since commodities are defined as “objects produced for sale on the market” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 75) and this definition does not hold for labour, land and money, they are referred to as fictitious commodities which are subjugated precisely because they need to be manageable for the competitive self-regulating market. Competition puts pressure on individuals and their surroundings and thus eventually leads to countermovements.

Whereas the concept of competition is not discussed extensively in Polanyi, Schumpeter hardly ever talks about markets but dedicates substantial parts of CSD to his understanding of competition. This circumstance can be attributed to their differing scope, where Polanyi explicitly discusses the self-regulating market and Schumpeter is trying to draft a more encompassing theory of capitalism. However, the discussion of competition is so prominent in Schumpeter’s work because he wants to demonstrate that capitalism and the growth rates observed during the time around 1900 are causally related. By substantiating this point in the second part of CSD Schumpeter, similar to Polanyi, thoroughly criticises the theory of perfect competition. Referring to other economists, he asserts that increasing monopolisation undermines competition and even claims that such a statement “involves the creation of an entirely imaginary golden age of perfect competition” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 81). Said economists and thinkers hold that the individual motive for profits that capitalism promotesFootnote9 does not lead to the maximum production possible unless perfect competition prevails. Schumpeter counters that if the economy is described as a stationary process inclined towards an equilibrium, a deviation from perfect competition indeed comes with social costs. But as is well known, Schumpeter’s understanding of the economy is dynamic:

The essential point to grasp is that in dealing with capitalism we are dealing with an evolutionary process. […] Capitalism, then, is by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationary. (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 82)

Capitalism has to be understood as a system. This evolutionary thinking is reflected in his understanding of competition which diverges from the Polanyian understanding of “perfect” competition for self-regulation which is

[…] not that kind of competition [price competition, quality competition, sales effort, authors’ note] which counts but the competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization (the largest-scale unit of control for instance)–competition which commands a decisive cost or quality advantage and which strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives. (Schumpeter, Citation[1942] 2003, 84)

Although the motive for gainFootnote10 and the change administered through it keep the capitalist engine going, competition and the threat it poses are equally important, especially in the process of creative destruction. The interplay of innovation and adaptation are central to this process. Andersen (Citation2011) describes it as a new innovation triggering a complex competitive process based on the adaptation of the new routine or an increase in productivity. The result is a sustained change in agents’ routines and most of the time an increase in prosperity and growth (Andersen Citation2011, 152–173).

In said process, rationality is essential to survive in the competitive struggle. It features prominently in CSD since it ultimately promotes the evolution of capitalism to socialism. Rationality transcends the economic sphere and influences the socio-cultural as well as the political sphere. Schumpeter argues that “all logic is derived from the pattern of the economic decision” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 122f). Individuals acting rationally in the Schumpeterian sense try to “make the best of it more or less – never wholly –” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 122), act logically and “by doing so on assumptions which satisfy two conditions: that their number be a minimum and that every one of them be amenable to expression in terms of potential experience” (Schumpeter, Citation[1942] 2003, 122). The importance of the economic sphere leads to a “slow though incessant widening of the sector of social life within which individuals or groups” (Schumpeter, Citation[1942] 2003, 122) act in this rationalistic way.

The presence of competition and markets increasingly shape the functioning of society in both TGT and CSD. Polanyi refers to this process as commodification; Schumpeter calls it rationalisation. In terms of our framework, this means that such an extraordinary change in the dominant economic sphere cannot be without consequences to the other spheres. Primarily, the socio-economic sphere has to cope with the consequences.

4.2. Subordination of the socio-cultural sphere

Commodification and rationalisation become central parts in the evolution of society by being the transmitters that enable the transcendence of economic principles to other spheres of society – most notably, the socio-cultural sphere.

As mentioned in section 3, Schumpeter (Citation[1942] 2003) refers to a set of propensities to feel and act that are subject to change through the underlying societal conditions as well as an unchanging human nature.Footnote11 Similarly, he asserts “that the ‘executive’ functions of thinking and the mental structure of man are determined, partly at least, by the structure of the society within which they develop” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 121). This demonstrates how Schumpeter views the influence of the economic on the socio-cultural sphere: as elaborated in the previous chapter, rational thought surges in the economic sphere and then starts to spread to the minds of those involved in said sphere. At this point, it is important to recall Schumpeter’s background and thinking on elites. When writing about the rationalisation of minds, he refers to bourgeois minds or, more precisely, entrepreneurs’ minds who were able to prove themselves in the economic sphere. At several points, this elitist understanding gets reinforced, as e.g., “[…] the mass of people are not in a position to compare alternatives rationally and always accept what they are being told.” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 129). In the “civilisation of capitalism”, the economic system helps to disperse rational thought through its “inexorable definiteness and […] quantitative character” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 123). Situations of social life are thus increasingly met with this “rationalistic” manner which disconnects emotions and social affairs. For Schumpeter, the “economic pattern is the matrix of logic” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 123) as the rationalisation of society essentially leads to the rise of logic and the banishment of “metaphysical belief, mystic and romantic ideas of all kind” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 127). Eventually, the “habit of rational analysis […] turns back upon the mass of collective ideas and criticizes and to some extent ‘rationalizes’ them” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 122), questioning hierarchy and becoming aware of “classwise rights” and wanting to act on them, as Andersen (Citation2011, 229) puts it.Footnote12 This makes e.g., feminism an “essentially capitalist phenomenon” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 127)Footnote13 that follows naturally from capitalism as it is only rational to demand equal rights when deprived of all emotional beliefs. This can also be applied to other forms of social injustice emerging from the capitalist system.Footnote14 To Schumpeter, fighting such tendencies would be equal to fighting evolution.Footnote15

Andersen (Citation2011) interprets the above stated tendencies to feel and act as social norms that are altered by rationalisation. The socio-cultural sphere “most directly reproduces and develops the norms and aspirations of the social actors” (Andersen Citation2011, 225). Social norms can thus be viewed as the channel via which the economic and sociocultural sphere influence each other. These, along with the values of the “upper ranks of the bourgeois stratum”, are so fundamentally altered that “they too are to be freed from the shackles of the system which oppresses them morally no less than it oppresses the masses economically” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 204). Combined with the inherent capitalist evolution of the economic system towards monopoly through creative destruction, this mechanism of rationalisation leads to socialism when the bourgeoisie starts to realise that the economy is more profitable when centrally organised. Essentially, “capitalism destroys itself, not by its vices, but by its virtues” (Robinson and Schumpter Citation1943, 382).

Polanyi expresses the same argument in a different, more clouded manner. Since, famously, “a market economy can function only in a market society” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 60), that system needs to be able to “function according to its own laws” which inter alia implies a separation of the economic and political sphere. As shown above, labour, land and money need to undergo a commodification process which conspicuously resembles the rationalisation process and transforms societal reality and socio-cultural surroundings: village structures are destroyed and the social fabric undeniably altered, leaving individuals without social shelter and protection. By comparing it to the experiences of colonisation, Polanyi speaks of “cultural degradation”, by which “labour and land are made into commodities, which, again, is only a short formula for the liquidation of every and any cultural institution in an organic society” Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 167). As a result of the invention of the machine, industrialists and factory owners push for the implementation of the self-regulating market. Consequently, aristocrats and workers combine forces to protect society and nature from the degradation that the self-regulating market and commodification signify. These countermovements are typically rooted in the political sphere, namely (social) legislation protecting land and labour from commodification. In spite of this, the economic sphere clearly remains dominant and proactive as the laws passed for protection are merely reactive measures trying to alleviate consequences that are economic in origin. The political sphere acts as an intermediary although there is no change in social norms as severe as in Schumpeter’s writings.

Polanyi argues for an embedded economic sphere for the sake of the social fabric and resulting needs of individuals. While he does not explicitly discuss the plasticity of human nature, he implies that human nature opposes any separation into spheres necessary for the dominance of the economic sphere and thus capitalism. Nevertheless, he acknowledges achievements such as civic liberties, private enterprise, and the wage system that according to him “fused into a pattern of life which favoured moral freedom and independence of mind” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 263). These are also considered worth preserving in any future society. Schumpeter, too, values these achievements that build on the success of early-stage capitalism in providing greater individual freedom of action to a larger number of people compared to feudalism and setting the preconditions for a peaceful development of society.

To summarise, the socio-cultural sphere is affected by rationalisation and commodification respectively which in turn impacts the political sphere (and to a lesser extent the economic sphere). In the Schumpeterian case, an evolutionary and elitist view prevails: individuals’ “propensities to feel and act” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 202) (inter alia social norms) as well as their minds are affected by rationalisation and bring about a change in attitudes, i.e., they partially adapt to altered circumstances. In the long run, the adaptation however feeds back into the political sphere. The bourgeois act in the interest of the system in order to maintain the status quo but are no longer able to introduce their morals. While the political system adapts, it is unable to deliver the moral standards expected of it (see below). Polanyi, by contrast, concentrates on transformational aspects: the economic system subjugates the rest of society, thereby destroying institutional arrangements and social fabrics intentionally and leaving individuals defenceless. Although the political system helped the economic sphere into dominance, it now becomes the refuge of the working class (and aristocrats to a smaller extent).

4.3. Stability of the capitalist system

The tension between the economic and the socio-cultural sphere described above leads to conflicts of interest, mediated within the political sphere. These conflicts fundamentally threaten the stability of the system for which both authors describe responses and effects reflecting their respective approaches (transformational-historical and evolutionary-analytical). The Polanyian focus is on the situation of stalemate between the industrialists formed in the economic sphere and the workers and aristocrats resisting through the political sphere. Schumpeter describes how rationalisation has affected the system and sees a resolution in the evolution from capitalism to socialism. In his analysis, the instability of the capitalist system is reflected in the sub-optimal political climate for the capitalist engine:

[T]he capitalist process produces a distribution of political power and a sociopsychological attitude – expressing itself in corresponding policies – that are hostile to it and may be expected to gather force so that they will eventually prevent the capitalist engine from functioning. (Schumpeter Citation[1941] 1991, 112f)

Some actors advocate for a fundamental change on the political level and “[…] count quantitatively at the polls” (Schumpeter Citation[1941] 1991, 140). Moreover, the political sphere becomes more and more subject to economic principles like the rationality dictate which manifests itself as a battle for votes to win a democratic election. In this battle, the political parties’ only objective is to maintain or obtain power. At the same time social norms and attitudes towards capitalism change, i.e., the motive power of the elites that ultimately enable the stability of the system. This results in an evolution to socialism. Schumpeter writes:

But it should be noted that that attitude and cognate factors also affect the motive power of the bourgeois profit economy itself, and that hence the proviso covers more than one might think at first sight – more, at any rate, than mere “politics”. (Schumpeter Citation[1941] 1991, 112f)

Note Schumpeter’s critique of the “classical” theory of democracyFootnote16 based on utilitarian thinking according to which democracy represents the “[r]ule by the people” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 243). For him, democracy does not deliver the values it emulates as it is merely an “arrangement” to arrive at “political – legislative and administrative – decisions and hence incapable of being an end in itself, irrespective of what decisions it will produce” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 242). Disregarding this opens the doors for populists and might result in a fascist political system. His elitist conception leads Schumpeter to value leadership and the entrepreneurial figure. With respect to his new interpretation of competitive political processes, he claims that

[…] this definition leaves all the room we may wish to have for a proper recognition of the vital fact of leadership. The classical theory [of democracy; authors’ note] […] attributed to the electorate an altogether unrealistic degree of initiative which practically amounted to ignoring leadership. But collectives act almost exclusively by accepting leadership – this is the dominant mechanism of practically any collective action which is more than a reflex. (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 207)

In capitalism, the bourgeois class takes up the leadership function. In contrast to the feudal system with its aristocratic leaders, entrepreneurial freedom in capitalism enables self-initiative and broadens the scope for individual agency. Those taking advantage of these newfound opportunities are entrepreneurs by definition. The same characteristics for succeeding as a leader in the economic sphere also apply to the political. Additionally, it “also selects the individuals and families that are to rise into that class [of bourgeois; authors’ note] or to drop out of it” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 74). Thus, the competitive struggle meets a selective, but legitimising function for elite leadership. Here, Schumpeter strongly builds on his meritocratic conception and the new incentive structures that have emerged along with capitalism. Classes are permeable on meritocratic grounds and the supposedly democratic permeability justifies the extensive power of the elites over the working class. This powerful position further enables the bourgeois to maintain the capitalist structure: they preserve the status quo by pursuing their own interests.Footnote17 The working class exclusively focus on their own short-term interests and are unable to form class consciousness and political demands. Indubitably, such a balance of interests skewed towards one class is hardly compatible with a democratic system.Footnote18

In the long run, rationalised social norms can thus be implemented via a benevolent and permeable elite. Schumpeter therefore suggests a technocratic government led by the bourgeois to facilitate the actual evolution to socialism on legislative grounds, i.e., the abolition of privately owned production factors, to secure the stability of the system. In Schumpeter’s view, the long-term evolutionary development is determined by the interplay of individual leadership decisions and the changing institutional structures, with partly unintended consequences.Footnote19

Polanyi also sees classes as variable and not exclusively shaped by material criteria, i.e., the form of income or ownership of means of production. Similar to Schumpeter, he challenges historical materialism, i.e., the Marxian notion that class conflict is the main driver of historical development. Polanyi argues that societies are challenged “as a whole” and the response to this challenge therefore “comes through groups, sections, and classes.” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 106).

He puts stronger emphasis on capitalist inter-class economic inequality and the social and political instability associated with it. In his perception, the advent of industrial production challenges social cohesion. The industrialist classFootnote20 emerging from the “remnants of older classes” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 162) support this new form of production by demanding the implementation of a self-regulating market. While industrialists – like Schumpeter’s bourgeoisie and entrepreneurs – do bring forth economic prosperity for the many and take charge of “the interests of the community as a whole”, they also provoke resistance against the “expansionist movement” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 162). Workers and nobility join forces to counter that and protect the basis of society, labour and land, i.e., the expansion of the market was “both advanced and obstructed by the action of class forces” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 162). Similar to Schumpeter, Polanyi identifies a change in political coalitions over the course of capitalism which results in instability with severe consequences.Footnote21

But if the rise of the industrialists, entrepreneurs, and capitalists was the result of their leading role in the expansionist movement, the defence fell to the traditional landed classes and the nascent working class. And if among the trading community it was the capitalists’ lot to stand for the structural principles of the market system, the role of the die-hard defender of the social fabric was the portion of the feudal aristocracy on the one hand, the rising industrial proletariat on the other. (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 162).

A democratic coordination and negotiation of interest is thus necessary in order to achieve stability. In Polanyi’s view, the citizens have political agency and are able to perform their democratic function and form collective demands. Because the economic sphere is threatening the very substance of people’s livelihoods, they organise and form countermovements in order to protect themselves. Paradoxically, this contradicts the self-regulating market that provides for precisely that livelihood. The requirements for the self-interest-based market society to work thus make it utterly unstable. Since capital is by design powerful in the economic sphere under capitalism, the latter becomes the stronghold for industrialists and capitalists who make up a minority in the political sphere as they are usually a smaller group overall. The democratic process, however, ensures that workers, who are typically stronger in numbers, control politics by building up strong unions and workers’ movements. As long as no tensions are present, the conflict of interest stays latent. Once it erupts, however, the system collides. Due to the – in Polanyi’s view – artificial and institutionalised separation of the economic and political spheres, the conflicting interests can no longer be balanced by a compromise and turn into an intense conflict between the economic and the political sphere; this is problematic because either one needs the other to function.Footnote22

This inherent instability might result in fascism – as it did at the beginning of the 20th century throughout Europe.Footnote23 Polanyi does not consider any society as particularly prone to fascism, instead, he famously considers fascism “[…] rooted in a market that refused to function” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 248). The actual transformation for fascism to assume power is based on the increasing resistance against the requirements of the market but is actually implemented by a small group of leaders. Both authors’ derivations and results resemble each other on this matter. Democratic legitimisation is not essential since Polanyi considers fascism a move rather than a movement, i.e., even small elite groups and tacit collaborators in power can establish fascist regimes. They succeed with their endeavour because the above-mentioned conflict surfaces and the situation becomes unbearable, leaving society paralysed. In Polanyi’s view, political compromise is possible and the individual classes are able to articulate their interests. However, the dominance of the economic sphere leads to an imbalance of power and thus to a standstill which can only be resolved by a subordination of democracy and the political sphere or a re-embedding of the economic system into the social.Footnote24

For Schumpeter, the necessary condition to regain stability (by surpassing capitalism) is the rationalisation of minds that guarantees for the elite in charge of the transition to abstract from their personal (economic) interests and think of the rationally optimal solution for society. Polanyi, on the other hand, is less optimistic about the benevolence of elite leadership in favour of the masses. Instead, he emphasises the resulting conflict of interests for business leaders in capitalist systems since democracy is no longer compatible with maintaining the capitalist mode of production.

Accordingly, in both theories not just the (short-term) (in)stability of the capitalist system is important, but the viability of the transition and therefore the (long-term) stability of society as a whole. Often these concepts of stability are antagonistic, yet interdependent. To summarise ( and ), the stability of the capitalist system demands the dominance of the economic sphere and thus the current political system is subverted and overcome (Schumpeter) or constantly contested (Polanyi).

Table 1. Results synthesised along different categories.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we analysed some of the main oeuvres of Schumpeter and Polanyi and showed that there are substantial similarities in their understanding of the interaction of different spheres of society and how it produces change in the societal system. The comparison is of interest since they not only share the common historical background but also their Austro Hungarian heritage. The divergence with regard to scope and methodology as well as their understanding of the legitimacy of democratic processes cannot hide the fact that both have a dynamic vision of capitalism and seek to reconstruct the patterns of historical transition. Despite the Polanyian transformational-historical and the Schumpeterian evolutionary-analytical emphasis, both concentrate on the interaction between three spheres – the economic, the political and the socio-cultural – as highlighted by our analytical framework.

By synthesising Schumpeter’s and Polanyi’s work, our framework can offer insights into differences, similarities, but most importantly, complementarities. Although both have some blind spots due to their backgrounds – which can again be identified making use of our framework –, the joint consideration of Polanyi and Schumpeter provides a consistent and insightful analysis of the workings of capitalism. They both describe the dominance of the economic sphere necessary for capitalism to work. Whenever this dominance is hindered, the system either tries to revive it by displacing the other spheres or evolves into a different kind of system. However, in both accounts the dynamic character is highlighted: the economic sphere triggers change in the sociocultural and the political spheres which in turn affect the economic again.

In conclusion, we want to highlight three points of interest – either because they show that Polanyi and Schumpeter have different blind spots, or because the similarities of their accounts are particularly striking. In any case, our analysis has shown that understanding benefits from a complementary comparison of the two thinkers. The following points might also open possible avenues for further research.

Due to the chosen scope and methodology, their understanding of the nature or necessity of societal spheres differs. Schumpeter comprehensively analyses capitalism as separating the overall evolution into sub-developments within distinct spheres. Ultimately, any society can be analysed using such an approach. Polanyi focuses on an historical account of the introduction of the self-regulating market and thus describes an actual separation of social processes into spheres. Thus, it is specific to the described period of market capitalism. For Polanyi, the separation is the cause for fascism to arise, whereas for Schumpeter it is useful due to its analytical benefits. However, both always perceive the economic process as being embedded in and never independent of the societal structures surrounding it. The idea of an independent economic sphere – either by a self-regulating market or in the sense of a static equilibrium – is merely a utopian dream.

In accordance with the former point, both authors navigate between the micro- and the macro-level: they write about human nature and describe aspects of people as individuals or part of groups but at the same time see the connection with the institutional framework and aggregate level as a society. Thus, in both theories the interdependence between individuals and institutions is central: Individual behaviours unfold within their institutional possibilities (but are also limited by them) and social change starts from a change in or violation of values and norms in the socio-cultural sphere.

In both Polanyian and Schumpeterian understandings, the role elites play strikes as particularly peculiar. A possible link for this could be their shared socialisation in the tumultuous Vienna of the early 20th century. In Schumpeter’s theory, there is a stark contrast between the entrepreneurs and bourgeois who initiate and the mass of people who adapt. He needs this distinction to introduce an endogenous dynamic. At the same time, as Section 4.3 points out, he values leadership or, more accurately, condemns the absence of leadership as dangerous. Polanyi does not distinguish between elites and masses according to their nature, but rather according to their class interests. In his account, it is a small elite that enforces change but the masses oppose. The democratically non-legitimized leadership is therefore dangerous. Eventually, this distinction also explains the divergent probable outcomes of the theories: in the one case socialism, in the other fascism.

While we have highlighted similarities, differences and complementary aspects of Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy and The Great Transformation using our framework of three societal spheres, we have definitely not exhausted the intersections of Schumpeter’s and Polanyi’s work overall. Especially their notions of socialism and utopian ideas, their ontological and epistemological understandings, their conceptions of freedom or their statements on populism provide ample space for even further investigations into the two contemporaries.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank anonymous referees, Heinz D. Kurz, Richard Sturn, Claudius Gräbner-Radkowitsch, and Patrick Mellacher for comments on earlier versions of this paper as well as participants of the EAEPE Annual Conference 2020, Momentum Kongress 2020, ICAE Research Seminar (December 2020), CHOPE Summer School 2021 (Duke University), International Schumpeter Conference 2021 and the Young Scholar Session at the ESHET Conference 2021. All remaining errors are the authors’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For the sake of clarity, we use the term “transition/transitional” to refer to the dynamic of societal change common in both authors’ theories. When relating to Schumpeter’s view of different spheres we use the term “evolution/evolutionary” in contrast to Polanyi’s consideration of societal change as a process of antagonistic (counter-)movements. The latter is termed as “transformation/transformative” throughout the following analysis.

2 For example, both were able to attend schools with excellent reputations: Schumpeter went to the Theresianium, a private boarding school in Vienna, and Polanyi graduated from the Minta Gymnasium, an elite grammar school in Budapest.

3 Nationalökonomie was the contemporary term for economics or political economy.

4 For a critical review on the extent to which he succeeds in this and the degree of applicability today, see Moura (Citation2003).

5 “Therefore, in describing the circular flow one must treat combinations of means of production (the production-functions) as data, like natural possibilities, and admit only small variations at the margins, such as every individual can accomplish by adapting himself to changes in his economic environment, without materially deviating from familiar lines. Therefore, too, the carrying out of new combinations is a special function, and the privilege of a type of people who are much less numerous than all those who have the “objective” possibility of doing it. Therefore, finally, entrepreneurs are a special type, and their behaviour a special problem, the motive power of a great number of significant phenomena.” (SchumpeterCitation [1934], 2004, 81)

6 As he later outlines in CSD, one of his main concerns was not to implement socialism prematurely and thus undermine the development of the productive forces and associated wealth accumulation through capitalism. This might partly explain his motivation to engage in these political debates.

7 This account likely stems from his engagement with static equilibrium models and its assumption of perfectly competitive markets that rule out any incentives for change. Therefore, in Schumpeter’s thinking, it is the innovative entrepreneur who brings about change and introduces a dynamic element (Schumpeter Citation[1934] 2004, chapters 1 and 2).

8 For the purpose of this paper, the scientific sphere is neglected as it is not imperative for Schumpeter’s transition mechanism in CSD (although he fairly often mentions elites more broadly) and it does not play a major role in TGT either.

9 Schumpeter talks about the motive of gain that is the driving factor for individuals to exert themselves. The promise of gain and upward mobility is “strong enough to attract the large majority of supernormal brains and to identify success with business success” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 81).

10 “Bourgeois society has been cast in a purely economic mold: its foundations, beams and beacons are all made of economic material. The building faces toward the economic side of life. Prizes and penalties are measured in pecuniary terms. Going up and going down means making and losing money. This, of course, nobody can deny. But I wish to add that, within its own frame, that social arrangement is, or at all events was, singularly effective. In part it appeals to, and in part it creates, a schema of motives that is unsurpassed in simplicity and force. The promises of wealth and the threats of destitution that it holds out, it redeems with ruthless promptitude. Wherever the bourgeois way of life asserts itself sufficiently to dim the beacons of other social worlds, these promises are strong enough to attract the large majority of supernormal brains and to identify success with business success.” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 73)

11 See chapter 18 “The Human Element”.

12 See Medearis (Citation1997, 820) who in this context speaks of the vindication of democratic values.

13 “These tendencies must be understood “objectively”, and […] therefore no amount of anti-feminist or antireformist talk or even of temporary opposition to any particular measure proves anything against this analysis. These things are the very symptoms of the tendencies they pretend to fight.” (Schumpeter Citation[1942] 2003, 127)

14 Compare Schumpeter (Citation[1942] 2003 127): “I have pointed out before that social legislation or, more generally, institutional change for the benefit of the masses is not simply something which has been forced upon capitalist society by an ineluctable necessity to alleviate the ever-deepening misery of the poor but that, besides raising the standard of living of the masses by virtue of its automatic effects, the capitalist process also provided for that legislation the means “and the will.” The words in quotes require further explanation that is to be found in the principle of spreading rationality.”

15 Nevertheless, Medearis (Citation1997) shows that Schumpeter did not actually embrace the democratising tendencies of his time and developed his elitist rule concept in light of the necessity to curb those tendencies. His “‘democratic’ socialism could only refer to a society that happened to combine a political system of ‘competitive leadership’ with state control of the economy” (Medearis Citation1997, 829).

16 The research on Schumpeter’s understanding of democracy in CSD is extensive (for a short overview until the 1990s see the introduction of Medearis (Citation1997)). Scholz-Wäckerle (Citation2016) discusses how democracy evolves along with several contradictions, including Schumpeter’s competitive view on democratic processes. Also, political science deals with the Schumpeterian concept of democracy, e.g., Achen and Bartels (Citation2017) and Shapiro (Citation2016).

17 Compare Scholz-Wäckerle (Citation2016) and his discussion of Schumpeter’s conception of elites and their function in democratic processes, where they “[…] try to reserve democracy for the republican idea through the conceptualization and interpretation of democracy as working under the same mechanics as free markets […]” (Scholz-Wäckerle Citation2016, 1005).

18 See e.g., (Ober Citation2017) or (Mackie Citation2009), who argue that Schumpeter’s definition of democracy is implausible as it undermines the very basic element of democracy – the existence of individual and common will. Similarly, Medearis (Citation1997) focuses on the difference and presence of an elitist democracy and democracy as an evolutionary power in the course of history in Schumpeter’s work – and thereby finds partly similar results as we do.

19 “For mankind is not free to choose. This is not only because the mass of people are not in a position to compare alternatives rationally and always accept what they are being told. There is a much deeper reason for it. Things economic and social move by their own momentum and the ensuing situations compel individuals and groups to behave in certain ways whatever they may wish to do – not indeed by destroying their freedom of choice but by shaping the choosing mentalities and by narrowing the list of possibilities from which to choose” (Schumpeter Citation[1941] 1991, 129f).

20 While Polanyi does use the term “entrepreneur”, we stick to “industrialist” for the sake of clarity.

21 Compare Schumpeter here pointing to the fact that the old, feudalistic institutional structure with aristocratic leadership left a vacuum of power that was filled by entrepreneurs and expanded their agency. At the same time, the former leadership by the aristocrats was not only restrictive, but furthermore of protective nature, that caused instability when degraded: “For those fetters not only hampered, they also sheltered” (Schumpeter Citation[1941] 1991, 135).

22 “Under conditions such as these the routine conflict of interest between employers and employees took on an ominous character. While a divergence of economic interests would normally end in compromise, the separation of the economic and the political spheres in society tended to invest such clashes with grave consequences to the community. The employers were the owners of the factories and mines and thus directly responsible for carrying on production in society (quite apart from their personal interest in profits). In principle, they would have the backing of all in their endeavour to keep industry going. On the other hand, the employees represented a large section of society; their interests also were to an important degree coincident with those of the community as a whole. They were the only available class for the protection of the interests of the consumers, of the citizens, of human beings as such, and, under universal suffrage, their numbers would give them a preponderance in the political sphere. […] No complex society could do without functioning legislative and executive bodies of a political kind. A clash of group interests that resulted in paralysing the organs of industry or state either of them, or both-formed an immediate peril to society” (Polanyi Citation[1944] 2014, 243f).

23 For a comprehensive discussion of Polanyi’s thoughts on fascism and how the opportunity of fascist movements is deeply rooted in capitalism see e.g., Dale and Desan (Citation2019). They furthermore discuss Polanyi’s thesis of socialism as a second way out of the crisis of modern society brought about by the institutional separation of economy and politics.

24 As Medearis (Citation1997) shows, Schumpeter also talks about a deadlock situation arising out of the political power labour organisations assumed in the early 20th century. Schumpeter writes: “The admission of labor to responsible office and the reorientation of legislation in the interest of the working class were in a sense an adjustment to a new state of things. But, with the two exceptions mentioned [Russia and Italy], all nations nevertheless attempted to run their economies on capitalist lines, thus continuing to put their trust in an engine, the motive power of which was at the same time drained away by crushing taxation.” (SchumpeterCitation[1941] 1991, 346f) and further “The business class has lost the power it used to have, but not entirely. Organised labor has risen to power, but not completely. Labor and a government allied to the unions can indeed paralyze the business mechanism. But it cannot replace it by another mechanism. [. . . ] [E]verybody check-mates everyone else.” (Schumpeter Citation[1948] 1991, 430)

References

- Achen, Christopher H, and Larry M. Bartels. 2017. Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Altreiter, Carina, Claudius Gräbner, Ana Rogojanu, Stephan Puehringer, and Georg Wolfmayr. 2020. “Theorizing Competition. An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Genesis of a Contested Concept.” SPACE Working Paper Series 3.

- Andersen, Esben S. 2011. Joseph A. Schumpeter: A Theory of Social and Economic Evolution. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chaloupek, Günther. 1995. “Long-Term Economic Perspectives Compared: Joseph Schumpeter and Werner Sombart.” The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 2 (1): 127–149. doi:10.1080/10427719500000097.

- Congdon, Lee. 1976. “Karl Polanyi in Hungary, 1900–19.” Journal of Contemporary History 11 (1): 167–183. doi:10.1177/002200947601100108.

- Dale, Gareth, and Mathieu Desan. 2019. “Fascism.” In Karl Polanyi’s Political and Economic Thought. A Critical Guide, edited by Gareth Dale, Christopher Holmes, and Maria Markantonatou, 151–170. Newcastle, UK: Agenda Publishing.

- Dale, Gareth. 2010. “Social Democracy, Embeddedness and Decommodification: On the Conceptual Innovations and Intellectual Affiliations of Karl Polanyi.” New Political Economy 15 (3): 369–393. doi:10.1080/13563460903290920.

- Dale, Gareth. 2016. Karl Polanyi: A Life on the Left. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Harvey, Mark, and Stan Metcalfe. 2004. “The Ordering of Change: Polanyi, Schumpeter and the Nature of the Market Mechanism.” Journal des Economistes et des Etudes Humaines 14 (2): 87–114. doi:10.2202/1145-6396.1128.

- Hejeebu, Santhi, and Deirdre McCloskey. 1999. “The Reproving of Karl Polanyi.” Critical Review 13 (3–4): 285–314. doi:10.1080/08913819908443534.

- Holmes, Christopher. 2014. “Introduction: A post-Polanyian Political Economy for Our Times.” Economy and Society 43 (4): 525–540. doi:10.1080/03085147.2014.955700.

- Holmes, Christopher. 2018. Polanyi in Times of Populism. Vision and Contradiction in the History of Economic Ideas. London, UK: Routledge.

- Kurz, Heinz D. 2012. “Investition und Zins: Die Beiträge Schumpeters und Keynes.” Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft 38: 197–210.

- Kurz, Heinz D., and Richard Sturn. 2011. Schumpeter für jedermann: Von der Rastlosigkeit des Kapitalismus. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Frankfurter Allgemeine Buch.

- Lloyd, Christopher, and Tony Ramsay. 2017. “Resisting Neo-Liberalism, Reclaiming Democracy? 21st-Century Organised Labour beyond Polanyi and Streeck.” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 28 (1): 129–145. doi:10.1177/1035304617693800.

- Mackie, Gerry. 2009. “Schumpeter’s Leadership Democracy.” Political Theory 37 (1): 128–153. doi:10.1177/0090591708326642.

- Maurer, Andrea. 2017. “Die Institutionen des modernen Kapitalismus: Karl Polanyi contra Max Weber.” In Normative und institutionelle Grundfragen der Ökonomik, Band 16, edited by Richard Sturn, Katharina Hirschbrunn, and G Kubon-Gilke. Marburg, Germany: Metropolis.

- Medearis, John. 1997. “Schumpeter, the New Deal, and Democracy.” American Political Science Review 91 (4): 819–832. doi:10.2307/2952166.

- Moura, Mário da Graça. 2003. “Schumpeter on the Integration of Theory and History.” The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 10 (2): 279–301.

- Ober, Josiah. 2017. “Joseph Schumpeter’s Caesarist Democracy.” Critical Review 29 (4): 473–491. doi:10.1080/08913811.2017.1394059.

- Özel, Huseyin. 2018. “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Marx, Weber, Schumpeter and Polanyi.” Yildiz Social Science Review 4: 111–124.

- Papageorgiou, Theofanis, and Panayotis G. Michaelides. 2016. “Joseph Schumpeter and Thorstein Veblen on Technological Determinism, Individualism and Institutions.” The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 23 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1080/09672567.2013.792378.

- Polanyi, Karl. 1992. “The Economy as Instituted Process.” The Sociology of Economic Life. edited By Mark Granovetter, Richard Swedberg, 29–51. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

- Polanyi, Karl. [1944] 2014. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Polanyi-Levitt, Kari. 2012. “The Power of Ideas: Keynes, Hayek, and Polanyi.” International Journal of Political Economy 41 (4): 5–15. doi:10.2753/IJP0891-1916410401.

- Robinson, Joan, and Joseph. A. Schumpeter. 1943. “Review of Joseph Schumpeter.” Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy.” The Economic Journal 53 (212): 381–383. doi:10.2307/2226398.

- Scholz-Wäckerle, Manuel. 2016. “Democracy Evolving: A Diversity of Institutional Contradictions Transforming Political Economy.” Journal of Economic Issues 50 (4): 1003–1026. doi:10.1080/00213624.2016.1249747.

- Schumpeter, Joseph Alois. [1934] 2004. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle, 10th edition. Translated by Redvers Opie. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Schumpeter, Joseph Alois. [1941] 1991. “An Economic Interpretation of Our Time: The Lowell Lecture.” In The Economics and Sociology of Capitalism, edited by R. Swedberg, 338–336. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Schumpeter, Joseph Alois. [1948] 1991. “Wage and Tax Policy in Transitional States of Society.” In The Economics and Sociology of Capitalism, edited by R. Swedberg. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Schumpeter, Joseph Alois. [1942] 2003. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. London and New York: Routledge.

- Schütz, Marlies, and Andreas Rainer. 2016. “JA Schumpeter and TB Veblen on Economic Evolution: The Dichotomy between Statics and Dynamics.” The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 23 (5): 718–742. doi:10.1080/09672567.2015.1018294.

- Shapiro, Ian. 2016. Politics against Domination. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.