Abstract

This paper elaborates on four different reasons why the assumption of continual dynamic stochastic general equilibrium, which is now standard in mainstream macroeconomics but is not used in agent based macro, makes a macro model less useful: (1) it assumes away most coordination problems, (2) it hides possible instabilities, (3) it makes money look unimportant, and (4) it makes inflation look trivial.

Axel Leijonhufvud’s “Towards a Not Too Rational Macroeconomics,” made a powerful case for the construction and deployment of Agent Based Macro (ABM) models, on the grounds that they dispense with the neoclassical postulate of rationality. Free of the constraint that all agents be demonstrably rational, ABM models can focus on the questions of interaction and coordination that had been, when he wrote, the central questions of macroeconomics. In this essay I argue that ABM models are powerful also because they dispense with the other core neoclassical postulate, namely that the economy is always in a state of equilibrium. In particular, I will elaborate on four different reasons why the assumption of continual dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE), which is now standard in mainstream macroeconomics but is not used in ABM, makes a macro model less useful: (1) it assumes away most coordination problems, (2) it hides possible instabilities, (3) it makes money look unimportant, and (4) it makes inflation look trivial.

1. Coordination problems

The first item on my list is almost tautological. To assume that the economy is always in a state of equilibrium is to assume that coordination has been achieved by some unspecified mechanism, because an equilibrium is a state in which everyone’s economic plans and activities are mutually compatible. This may be a good assumption for many purposes, but not for studying the central macroeconomic problems of recession, unemployment, and inflation, all of which involve people acting at cross purposes.

I say this even though there is a literature on coordination failuresFootnote1 that is based on equilibrium analysis. This literature studies cases in which an economy can exhibit multiple, Pareto-ranked equilibria. There are insights to be gained from such cases, but they are limited to conditions under which non-linearities arising from strategic complementarity are strong enough to guarantee the existence of multiple equilibria. To my knowledge no one has ever provided a convincing demonstration that such conditions hold in reality. More fundamentally, the basic problem of coordinating the economic activities of a multitude of heterogeneous economic agents does not vanish when non-linearities are weak enough.

Moreover, even if multiple equilibria could be shown to exist in a particular case, the analysis might or might not imply a macroeconomic coordination problem depending on whether or not the economy settles into one of the Pareto inferior equilibria. But there is nothing in the equilibrium analysis that can tell us which equilibrium will be achieved. For that we need to theorise about how the economy behaves when it is out of equilibrium.Footnote2

So, in the end, in order to make use of the coordination failure literature, we need to go beyond equilibrium analysis. And once we do that, the equilibria begin to lose interest. For coordination problems can manifest themselves not just when disequilibrium behaviour has led the economy to a Pareto-dominated equilibrium, but also when the economy lingers in a poorly coordinated state of disequilibrium, perhaps never converging on any equilibrium.

More generally, the technical requirements of dynamic stochastic general equilibrium usually require a modeller to make a lot of simplifying assumptions, and to assume special functional forms chosen solely for their tractability. One ends up with a simple system in which the actors are incredibly sophisticated, whereas in reality, if we are to believe the writings of modern behavioural economists, which I do, an economy is just the opposite - a complicated web of people behaving according to relatively simple rules.Footnote3

It is important to remember that a central goal of macroeconomic theory is not just to explain why a decentralised economic system sometimes exhibits problematical behaviour but also to explain how it keeps this complicated web so well coordinated most of the time. The US economy, for example, spends most of its time with almost all of the work force gainfully employed, producing a level of per capita income that would have been unimaginable a century ago. How does this orchestra make such beautiful music without a conductor? Some people claim that general equilibrium theory provides an answer. But a system that is endowed with an “auctioneer,” or any other costless mechanism that tells people how to choose mutually compatible plans and actions is by definition not decentralised.Footnote4 One of the benefits of ABM models is that they can assume that each actor is “autonomous”; that is, capable of acting on purely local information, without receiving instructions from someone who has “solved” the system. That autonomy is the essence of decentralisation, and it requires that general equilibrium be a possibly emergent property of the system, not an assumption.

2. Possible instability

Restricting policy analysis to the study of DSGE also blinds the economist to the possibility that certain kinds of policies can render even a unique general equilibrium dynamically unstable. A case in point, on which I have written,Footnote5 is that of a monetary policy that pegs the nominal rate of interest, or more generally one that violates the “Taylor principle,” to the effect that the rate of interest should vary more than one-to-one with the rate of inflation.

The Taylor principle has been challenged by the school of thought known as Neo-Fisherism,Footnote6 which eschews anything but equilibrium analysis. According to Neo-Fisherism, a central bank can reduce inflation by reducing its policy rate of interest and pegging it at its new lower level independently of any subsequent developments, in clear violation of the Taylor principle. The logic behind this proposition is clearest if we assume there is an expectations-augmented Phillips Curve with a unit coefficient on expected inflation, and that monetary policy works only through the real rate of interest.Footnote7 If the bank announces and executes a previously unanticipated Δ point reduction in the interest rate, and people immediately reduce the expected rate of inflation by Δ points, then by definition the policy action will not affect the real rate of interest or, by extension, the level of output or employment. Therefore, according to the expectations-augmented Phillips Curve, the effect on the actual rate of inflation will be to reduce it by the expected Δ points.

Anyone who has had the job of conducting monetary policy will tell you from experience that this neo-Fisherian proposition is 180 degrees from the truth. People will not expect a cut in interest rates to bring inflation down. Instead, as we have seen recently in the US and elsewhere, it is increases in interest rates, not decreases, that cause almost all economists and journalists to expect inflation to come down, at least somewhat. Nor am I aware of any evidence that recent rate hikes have led to the increase in inflation expectations among the general public that neo-Fisherian theory would predict. On the contrary, the University of Michigan survey of inflation expectations one year ahead peakedFootnote8 in March 2022, the month in which the Fed began its publicly announced series of rate increases. Neil Wallace once observed, perhaps in jest, that the theory of rational expectations is either wrong or not new, because if it was right then, by the very assumptions of the theory, the general public must have had rational expectations all along. A rational expectation that cutting interest rates will reduce inflation would be a surprising revelation to most people that actually give such matters any thought, so it must be wrong.

Instead, as Friedman (Citation1968) explained so clearly, when the Fed cuts interest rates, people will either raise their expectations of inflation or leave them unchanged until they see what happens. So, the initial effect of lower nominal interest rates will be a lower real interest rate, which will raise aggregate demand and hence put upward pressure on inflation. Moreover, when this increase in inflation feeds into expectations, it will reduce the real interest rate even further, causing a further rise in aggregate demand, and so on in cumulative fashion until the policy is abandoned and the nominal interest rate is finally raised by more than the expected rate of inflation, by which time inflation will be higher than it was initially, not lower as the neo-Fisherian analysis predicted.

Neo-Fisherians will counter with the charge that this Friedmanesque analysis depends on an ad hoc scheme of adaptive expectations, whereas the only outcome consistent with rational expectations equilibriumFootnote9 is the neo-Fisherian result of lower inflation. But, as I showed in Howitt (Citation1992), the outcome of ever rising inflation until interest rates are raised by more than expected inflation, far from depending on a particular ad hoc assumption about expectations, is implied, in a wide variety of macro models, under any expectational scheme in which people genuinely try to learn from experience. Specifically, the only requirement on expectations is that if people have always seen inflation higher than expected, and higher than the period before, then they must expect higher inflation next period than they did last period. Anyone who violated that requirement could fairly be said to be refusing to learn from experience.Footnote10

In essence, the problem is that even though there is a rational expectations equilibrium that yields the neo-Fisherian result, perhaps even a unique equilibrium, that equilibrium is not dynamically stable under any sensible assumption about expectations. The equilibrium requires a fall in inflation, but when people try to learn from experience, they are led to expect higher inflation, and then inflation rises even more than expected. The result is an explosive divergence from equilibrium.

Thus we have an example of a macroeconomic proposition that is consistent with a great deal of empirical evidenceFootnote11 and is supported by a general theory that imposes almost no restrictions on the formation of expectations, but which is impossible to reconcile with DSGE theory except through analysis of the disequilibrium adjustment processes that take place out of equilibrium.Footnote12 This is certainly not the only example of a proposition which is true in DSGE theory but which cannot be true under any sensible assumption about expectations. Any time there is a variable x that is affected more than one for one by changes in its expected value Ex, the same analysis will imply that the rational expectations equilibrium in which x = Ex will be asymptotically unstable under any expectational scheme that satisfies the minimal property outlined above. For example, Fazzari (Citation1985) has shown that Harrodian instability of investment dynamics has the same character, with the actual rate of investment being affected more than point-for-point by the expected rate of investment. Propositions of this sort are not interpretable by a theory that considers only what happens in equilibrium.

3. The quantity of money

The modern DSGE theory that guides monetary policy around the world today is quite explicit in denying any independent role to the quantity of money in influencing the level of economic activity. According to this theory, monetary policy can be fully described in terms of interest rates, without reference to money; indeed, as Woodford (Citation2003) has shown, monetary policy operates exactly as it would in a “cashless” economy where fiat money does not even exist as a means of payment or store of value.

In this respect, modern theory is really no different than IS-LM theory, in which the LM curve is a redundant fifth wheel when a central bank uses an interest rate as an instrument. In both cases, the only channel through which a central bank can affect aggregate demand is its policy interest rate. The LM curve can still be used, but only to determine what will happen to the money supply, which does not feed back into income determination. (In principle, as Patinkin showed, the real-balance effect provides another channel through which money can influence aggregate demand, independently of its effect on interest rates, but in practice the outside money supply is such a small fraction of aggregate wealth that this independent channel is quantitatively negligeable.)

When an interest rate is the instrument of monetary policy, the most a monetarist could claim, according to both IS-LM and modern DSGE, is that the quantity of money is an important indicator of monetary policy’s influence on the economy. For this to be true there must of course be a stable demand function for money that is not too interest-elastic, which of course Friedman argued was indeed the case. Under such circumstances one cannot infer whether the central bank’s current setting of interest rates is too high or too low without looking at the quantity of money, because one cannot directly observe the volatile exogenous component of aggregate demand, which is a key determinant of the bank’s “neutral” interest rate.

But, with changes in the payments mechanism, it is clear that there have indeed been sizeable shifts in the demand for money in recent decades. Not only do these developments bring into question the appropriate definition of money, they also undermine the only remaining reason for paying attention to the money supply in DSGE theory.Footnote13 Thus central bankers, having adopted a framework in which the money supply plays no role in the transmission mechanism, found it very easy to stop paying attention to it altogether.

It would have been harder for central bankers to abandon money if they had not been guided by a theoretical framework in which equilibrium is assumed to prevail at all points in time; in particular, by one in which the supply and demand for money are always equilibrated. An alternative is provided by the buffer-stock theory of money.Footnote14 In this theory, economic actors use their money holdings to buffer their economic lives against fluctuations in their cash flow, allowing their planned transactions, on both current and capital account, to remain on schedule in the face of temporary shocks. According to this theory, as in the once widely taught theory of the precautionary demand for money, the setup cost of transacting makes it prohibitively expensive to keep actual money holdings exactly equal to desired holdings at all points in time. Instead, transactors will intervene only occasionally with special asset transactions to reset their money holdings.

An individual can thus remain with an excess demand or supply of money for a considerable period of time. Moreover, money’s special role as a medium of exchange and “temporary abode of purchasing power,” to use Friedman’s apt phrase, implies that an excess demand or supply for money can persist for an even longer time at the aggregate level than at the individual level. This is because, to paraphrase Friedman once more, the transactions by which one individual makes a one-time adjustment to eliminate an excess or deficiency of cash holdings will typically pass the hot potato along to some other individual, who may also take some time before passing it along to another, and then another …

In such a theory, an increase in the quantity of money can create an excess supply that will eventually lead to an increase in aggregate demand, without necessarily having a significant effect on interest rates. Instead, people willingly allow the newly created money to increase their existing holdings, with perhaps minimal changes in asset yields, creating an excess supply of money, the counterpart by Walras’ Law to an excess demand for goods and services, that people will try to eliminate only gradually by increased spending. If the authorities are not paying attention to the money supply, they may not see any indication of this potential increase in aggregate demand.

If central bankers had been guided by such a framework in recent years, it would have been difficult for them to stop paying attention to the money supply the way they did. And they would have been quicker to realise that in fact money has not lost all of its predictive power. Indeed, in many countries they would have noticed a historically unprecedented increase in the rate of monetary expansion, starting in 2020, which foreshadowed the persistent increase in inflation that these countries have experienced since 2021, as predicted by classical monetary theory.

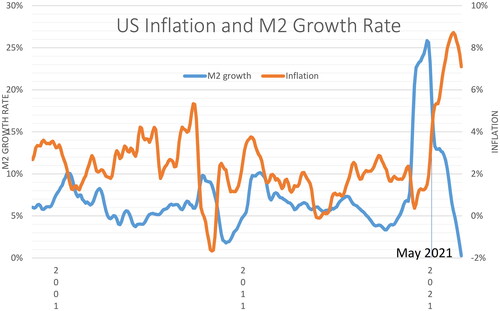

Consider what happened in the United States, for example. shows that by May of 2021, when inflation was just starting to take off, M2 had been growing faster than ever before recorded by this data series, for over a year. Indeed, the annual growth rate of M2 peaked in February at 25.8%, which was almost twice as high as the highest rate ever recorded before 2020 since this data series began in January 1959.Footnote15 Nor was this phenomenon of record high growth limited to the a particular definition of money; the growth rate of William Barnett’s alternative Divisia Index measures of the money supply also underwent a large increase over the same period in Bordo and Duca (Citation2023). also shows that inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, soon reached levels not seen since the great inflation of the 1970s and 80s.

Figure 1. Lagging 3-month moving averages of the percentage change (of respectively the CPI and M2) over the previous 12 months.

This huge increase in the rate of monetary expansion, combined with the shortages of goods and services that were beginning to appear throughout the US economy, was just what one would have expected to see if the economy had been experiencing a large excess supply of money. It also bore an uncanny resemblance to the runup to the great inflation in the early 1970s, when many were also arguing, mistakenly it turns out, that the rise in inflation was attributable to temporary supply-side effects.

Nevertheless, the Federal Reserve System allowed this unprecedented increase in monetary expansion to go unchecked for over a year. Why? According to Chairman Powell it was because the Fed no longer believed that there was any empirical connection between monetary expansion and inflation.Footnote16 But it appears that the connection has not entirely disappeared. Indeed, the analysis of Borio, Hofmann and Zakrajšek (Citation2023) shows that excessive monetary expansion was a good predictor of the unexpected increase in inflation in many other countries as well.Footnote17 In any event, I would have thought that a historically unprecedented increase in the one variable that generations of economists have shown to be associated with inflation would at least have rung some alarm bells.

Clearly, the Fed and other central banks just weren’t paying attention. Instead, they allowed themselves to be diverted by supply-chain problems, which were probably also important if we want to understand the short-run dynamics of inflation but clearly not the whole story, until the consensus finally shifted to the opinion that aggregate demand management had been too stimulative, with no mention of what was happening to the money supply, except, as pointed out above, to deny that it was of any importance. The Fed finally started raising interest rates in March 2022, 22 months after the rate of M2 growthFootnote18 had first surpassed its previous historical peak.

In my opinion, this failure of central banks is attributable to the fact that modern short-run macro theory, the kind used by all of them, attaches no importance to the quantity of money, and it does so because of the overuse of the concept of equilibrium. In particular, macroeconomic theory for decades has proceeded under the assumption that the supply and demand for money are always equal. I believe this is why if you google the topic of US M2 growth and inflation you find lots of journalistic commentary, but almost nothing by any prominent academic economist. Money has just gone out of fashion in short-run macro, and to talk of a persistent excess supply of money is to suggest that some equilibrium condition is being violated, which has become downright disreputable.

4. Cost of inflation

Chari and Kehoe (Citation2006) claim that one of the principles that modern macroeconomic theory has established conclusively is that low inflation is the most appropriate goal for monetary policy. In reality, on the contrary, modern macroeconomic theory has never managed to come up with a satisfactory account of why a high trend rate of inflation should entail a quantitatively significant cost to society.

The most clearly articulated case for low inflation in modern theory comes from the public-finance argument that supports the Friedman ruleFootnote19, which is to reduce inflation to the point where the nominal rate of interest equals zero, on the grounds that the real quantity of money, being costless for society to increase by means of deflation, should be costless for individuals to hold as an asset. But this case actually trivialises the cost of inflation, because the saving that would arise in principle from going all the way from even a ten percent inflation to the negative four percent that the Friedman rule dictates would consist of the elimination of a tax on non-interest-bearing money holdings, a saving that almost all published research estimates to be a small fraction of GDPFootnote20 because the base of this tax is itself a small fraction of total wealth in any advanced economy.

New Keynesian DSGE models, in which, as we have seen, money as a means of exchange and store of value plays no essential role, offer another possible reason for targeting low inflation, namely the inefficiency that inflation produces by creating a wider dispersion of relative prices for no reason other than the fact that different sellers are at different stages of the price change cycle; those with more recent price changes will tend to have higher relative prices because they have made the most recent adjustment to inflation. In these models the optimal trend rate of inflation is clearly zero, except possibly for second-best public finance reasons (Phelps Citation1972) or risk-sharing considerations (Levine Citation1991) that might argue for a positive rate.

Howitt and Milionis (Citation2007) show that in the deterministic new Keynesian DSGE of Yun (Citation2005), the price dispersion cost can be substantial once inflation reaches even 6 or 7 percent, and that at 10 percent inflation the cost is enormous, being equivalent to 30 percent of aggregate consumption! But they also show that this argument is dependent on an aspect of the Calvo pricing model that is particularly unconvincing. In particular, once the trend inflation rate reaches 10 percent, over 35 percent of aggregate output is produced by the 0.3 percent of firms that are selling at a price below marginal cost! These firms would certainly want to either raise their price or curtail production if it were not for the fact that they have not recently been visited by the Calvo fairy, but the model requires them anyway to produce however much is demanded at their obsolete prices. Replacing the Calvo model by a Taylor model of fixed price-change intervals, with as much as a 7 quarter lag between price changes, gets rid of this counterintuitive feature of the model and has no firms selling below marginal cost, but it also reduces the cost of a 10 percent inflation to about 1.5% percent of aggregate consumption.

Moreover, if one keeps the assumption of Calvo pricing but reinserts lagged inflation in the Phillips Curve, as central bank DSGE models typically do, by invoking the usual indexation story - that price setters not visited by the Calvo fairy adjust their prices as a function of lagged inflation – then the cost of inflation in the DSGE model is almost entirely eliminated, because indexation greatly reduces the extent to which inflation raises price dispersion. For example, Billi (Citation2011) presents a model that includes such indexation and is calibrated to U.S. data, paying strict attention to the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates. He shows that while the optimal mean rate of inflation is less than 1% per annum under commitment it is almost 17% under discretion. Yet he also reports that the welfare cost of going from commitment to discretion is less than 0.5 percent of aggregate consumption!

I conclude that the cost of inflation is not something that modern DSGE theory is capable of addressing. However, an ABM framework that abandons the assumption of continuous equilibrium, can do so. For example, Ashraf, Gershman and Howitt (Citation2016) showed that in an extended version of the Howitt and Clower (Citation2000) ABM model, calibrated to the U.S. economy, the trend rate of inflation has a significantly positive effect on the equilibrium rate of unemployment, because inflation interferes with the workings of the decentralised market mechanism that brings buyers and sellers together. Specifically, the higher the rate of inflation the more difficult it is for the firms that operate markets to remain in business, because of the well-known tendency of inflation to induce noise into the price system. This is a result that falls naturally out of an ABM approach, but which is impossible to replicate in any DSGE model without making unbelievable assumptions.

Of course, there is the possibility that DSGE models are correct, that inflation is indeed not costly to society, and that central bankers are acting against the social good by focusing on inflation. But at times like the early 2020s and the late 1970s, when inflation is persistently high, US public opinion polls typically rank inflation as one of the major problems facing the country. So, if inflation is not in fact socially costly then these poll results contradict that other basic assumption of DSGE models, the one to which Axel objected, to the effect that all the agents in the economy are rational.

5. Conclusion

Equilibrium has been a central concept of economic theory at least since the 18th Century.Footnote21 It has led to great developments in many areas of both micro and macro theory. Indeed, modern microeconomics has been transformed by various refinements of the idea of Nash equilibrium. One could even argue that almost every useful contribution of modern economic theory has been based on equilibrium theory. But there are large areas of macroeconomics where the exclusive focus on equilibrium that is characteristic of modern DSGE theory is misleading. In those areas equilibrium is still a useful concept, but only when used in the way that economists from Smith through Samuelson have used it, namely as a reference point for understanding the dynamic evolution of an economic system. Modern ABM models offer a method for returning to this classical idea.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks David Laidler and Hans-Michael Trautwein for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Cooper and John (Citation1988), Diamond (Citation1982), Howitt (Citation1985), Howitt and McAfee (Citation1987).

2 For example, Howitt and McAfee (Citation1992).

3 See also Leijonhufvud (Citation1993, 1–2).

4 This was also the essence of Hayek’s (Citation1937, Citation1945) criticism of general equilibrium theory. “The economic problem of society … is a problem of the utilization of knowledge not given to any one in its totality.” (1945, 519–20), and “equilibrium analysis … does not deal with the social process at all” (1945, 530).

5 Howitt (Citation1992).

6 Cochrane (Citation2016), Williamson (Citation2019).

7 Minor qualifications are needed in the canonical model of Woodford (Citation2003) where the coefficient on expected inflation is approximately one.

8 At 5.4 per cent (retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MICH, June 16, 2023).

9 In the canonical New Keynesian DSGE model of Woodford (Citation2003) such a policy will lead to indeterminacy, so there are many other outcomes consistent with rational expectations equilibrium. But all the equilibria eventually lead to a lower inflation rate. There are, however, models with a unique rational expectations equilibrium even when the Taylor rule is violated, in which this immediate drop in actual inflation is implied (Howitt, Citation1992).

10 The paper also shows that the same instability result holds if there are variations across individuals in the method for forming inflation expectations, as long as each individual’s method obeys this minimal requirement. The analysis of the paper does not, however, allow for discrepancies between actual and perceived rates of inflation, which Jonung (Citation1981) has shown can be substantial.

11 Consider, for example, the recent failed attempt in Turkey to reduce inflation by lowering interest rates.

12 In fairness, DSGE modelers outside the neo-Fisherian movement do check the expectational stability of their analysis, and their analysis confirms my earlier finding that the Taylor rule is necessary and sufficient for stability (for example, Woodford Citation2003, 266).

13 Although Woodford (Citation2008) argues that money growth is not something a central bank should target, he does state that there is no reason why a variety of monetary statistics should not be among the large number of indicators that are used by a central bank in making its projections.

14 See, for example, Laidler (1974, Citation1984), Judd and Scadding (Citation1982), and Knoester (Citation1984).

15 These growth rates were not affected by the Fed’s decision to include saving deposits in M1 starting in May 2020, a change which did not affect M2. (See item 5 in https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h6/h6_technical_qa.htm.).

16 In response to a question by Senator Kennedy of Louisiana, during the Senate Banking Committee Hearings on the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to Congress, February 2021, he stated that “the growth of M2 … doesn’t really have important implications for the economic outlook.” (https://www.banking.senate.gov/hearings/02/12/2021/the-semiannual-monetary-policy-report-to-the-congress).

17 This is despite the fact that the situation in Europe was a bit different from the United States, in the sense that European M3 growth was lower than U.S. M2 growth, Europe had less politically motivated fiscal expansion, and European supply shocks were more severe after the Russian assault on Ukraine.

18 Again as measured by the lagging 3-month moving average.

19 Friedman (Citation1969).

20 For example, Lucas (Citation2000).

21 Milgate (Citation1987).

References

- Ashraf, Quamrul, Boris Gershman, and Peter Howitt. 2016. “How Inflation Affects Macroeconomic Performance: An Agent-Based Computational Investigation.” Macroeconomic Dynamics 20 (2): 558–581. doi:10.1017/S1365100514000303.

- Billi, Roberto M. 2011. “Optimal Inflation for the U.S. Economy.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 3: 29–52.

- Bordo, Michael D., and John V. Duca. 2023. “Money Matters: Broad Divisia Money and the Recovery of Nominal GDP from the COVID-19 Recession.” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Research Department Working Paper No. 2306.

- Borio, Claudio, Boris Hofmann, and Egon Zakrajšek. 2023. “Does Money Growth Help Explain the Recent Inflation Surge?” BIS Bulletin #67.

- Chari, V. V., and Patrick J. Kehoe. 2006. “Modern Macroeconomics in Practice: How Theory is Shaping Policy.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20 (4): 3–28. doi:10.1257/jep.20.4.3.

- Cochrane, John. 2016. “Do Higher Interest Rates Raise or Lower Inflation?” HooSver Institution Working Paper.

- Cooper, Russell, and Andrew John. 1988. “Coordinating Coordination Failures in Keynesian Models.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 103 (3): 441–463. doi:10.2307/1885539.

- Diamond, Peter. 1982. “Aggregate Demand Management in Search Equilibrium.” Journal of Political Economy 90 (5): 881–894. doi:10.1086/261099.

- Fazzari, Steven M. 1985. “Keynes, Harrod and the Rational Expectations Revolution.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 8 (1): 66–80. doi:10.1080/01603477.1985.11489543.

- Friedman, Milton. 1968. “The Role of Monetary Policy.” American Economic Review 58: 1–17.

- Friedman, Milton. 1969. The Optimum Quantity of Money. Chicago: Aldine Press.

- Hayek, Friedrich von. 1937. “Economics and Knowledge.” Economica 4: 33–54.

- Hayek, Friedrich von. 1945. “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” American Economic Review 35: 519–530.

- Howitt, Peter. 1985. “Transaction Costs in the Theory of Unemployment.” American Economic Review 75: 88–100.

- Howitt, Peter. 1992. “Interest Rate Control and Nonconvergence to Rational Expectations.” Journal of Political Economy100 (4): 776–800. doi:10.1086/261839.

- Howitt, Peter, and Robert Clower. 2000. “The Emergence of Economic Organization.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 41 (1): 55–84. doi:10.1016/S0167-2681(99)00087-6.

- Howitt, Peter, and Preston McAfee. 1987. “Costly Search and Recruiting.” International Economic Review 28 (1): 89–107. doi:10.2307/2526861.

- Howitt, Peter, and Preston McAfee. 1992. “Animal Spirits.” American Economic Review 82: 493–507.

- Howitt, Peter, and Petros Milionis. 2007. On the Robustness of the Calvo Price Setting Model. Providence, RI: Brown University.

- Jonung, Lars. 1981. “Perceived and Expected Rates of Inflation in Sweden.” American Economic Review 71: 961–968.

- Judd, John P., and John L. Scadding. 1982. “The Search for a Stable Money Demand Function: A Survey of the Post-1973 Literature.” Journal of Economic Literature 20: 993–1023.

- Knoester, Anthonie. 1984. “Theoretical Principles of the Buffer Mechanism, Monetary Quasi-Equilibrium, and Its Spillover Effects.” Credit and Capital Markets - Kredit und Kapital 17 (2): 243–260. doi:10.3790/ccm.17.2.243.

- Laidler, David. 1974. “Information, Money and the Macro-Economics of Inflation.” The Swedish Journal of Economics 76 (1): 26–41. doi:10.2307/3439354.

- Laidler, David. 1984. “The Buffer Stock Notion in Monetary Economics.” Economic Journal Supplement: Conference Papers 94: 17–34.

- Leijonhufvud, Axel. 1993. “Towards a Not-Too-Rational Macroeconomics.” Southern Economic Journal 60 (1): 1–13. doi:10.2307/1059926.

- Levine, David K. 1991. “Asset Trading Mechanisms and Expansionary Policy.” Journal of Economic Theory 54 (1): 148–164. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(91)90110-P.

- Lucas, Robert E. Jr. 2000. “Inflation and Welfare.” Econometrica 68: 247–274.

- Milgate, Murray. 1987. “Equilibrium (Development of the Concept).” In The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Ed by John Eatwell, edited by Murray Milgate, Peter Newman. London: Macmillan.

- Phelps, Edmund S. 1972. Inflation Policy and Unemployment Theory. New York: Norton.

- Williamson, Stephen. 2019. “Neo-Fisherism and Inflation Control.” Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne D'économique 52 (3): 882–913. doi:10.1111/caje.12403.

- Woodford, Michael. 2003. Interest and Prices: Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Woodford, Michael. 2008. “How Important is Money in the Conduct of Monetary Policy?” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 40 (8): 1561–1598. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4616.2008.00175.x.

- Yun, Tack. 2005. “Optimal Monetary Policy with Relative Price Distortions.” American Economic Review 95 (1): 89–109. doi:10.1257/0002828053828653.