Abstract

The article describes an educational and artistic project in Poland where individuals with sight impairments could learn more about visual arts through guided city tours around their greatest monuments, appreciation of art pieces and meetings with artists. During workshops, they could test their own artistic skills by creating tactile drawings, pottery sculptures, photographs and tactile picture book. The effects of their attempts were presented in a temporary exhibition in the contemporary art gallery (with an associated educational program). The exhibition was a significant experience both for the artists with visual impairments and the visitors. Through analysis of the structure and content of the artworks, the gallery visitors could understand more about the situation of people with sight impairments as they struggle with everyday tasks and how creative they are.

People without disabilities know little about the difficulties that individuals with severe visual impairment have to deal with on an everyday basis. "Visual impairment has been considered one of the most threatening disabilities, typically awakening emotional reactions of extreme loss of confidence and independence in individuals confronted with this disability” (Reina et al. Citation2011, 244). Studies involving typically developing preschool children showed that they were less likely to make inclusion decisions with respect to a child with visual impairment than with a peer with a mobility disability – most probably due to limited knowledge about the activities available to blind children (Hong, Kwon, and Jeon Citation2014). The study of attitudes towards disabled people conducted in Poland in the 1990s (Ostrowska Citation1994) revealed that those people are often perceived as strange and different. They are thought to be unsuccessful and unfulfilled, and not equal partners for people without disabilities. It is believed that less should be required of them due to their limited abilities. Unfortunately, not much has changed since that study and the stereotypical opinions about people who are blind are still as much present in Polish society as they used to be. Recent experiments only confirm it (Niestorowicz Citation2017). In the study, the spectators were asked to evaluate ceramic sculptures made by deaf-blind artists, with and without knowledge about the artists’ disability. It turned out that the spectators who knew about the authors' disability attributed all the imperfections of art pieces to the clumsiness of disabled sculptors.

I wondered if the negative attitude towards people who are blind could be associated with the fact that those people are hardly ever present in public life in Poland? That, in turn, should not come as a surprise since in Poland, people who are blind have very limited access to information, not many websites are visually impaired friendly, they need to fight for audio descriptions in public television broadcasting and so on. I was thinking how the full spectrum of abilities of people with visual impairments can be revealed to those who question them. Perhaps, by perverse actions and by surprise, by exhibiting work of people who are blind and visually impaired in the field seemingly unavailable to them, in visual arts? And yes, driven by my desire to fight against the stereotypes I got involved in the culture promoting project entitled ‘City That Can't Be Seen’ [Miasto, którego nie widać].Footnote1

I invited young people and adults with visual impairment (mainly congenitally blind) from Lublin, to participate in my project. I offered them walks around the town in the areas of publicly exhibited contemporary art, city monuments and museums. The participants had an opportunity to meet visual artists working in our city and take part in a series of workshops on drawing, photography, ceramic sculpting, and tactile picturebook. All the works created during workshops were the interpretations of the project title: ‘City That Can't Be Seen’.

At the end of the project, a temporaryFootnote2 exhibition was organized in one of the major contemporary art galleries in Poland, Galeria Labirynt in Lublin. The exhibition was accompanied by an educational program held by the gallery staff. The artworks were exhibited in poor light, almost dusk and the visitors were encouraged to wear specially prepared blindfolds and touch the art pieces to experience them. All the art pieces except for the photos were displayed on tables set in a row with descriptions in Braille so that a visitor could walk along the tables and discover the objects, touching each of them with a hand as he walked by. It is striking that apart from the collages for a tactile picturebook, almost all of the exhibited pieces of art were monochromatic. The exhibition and the accompanying educational program should be considered as an awareness intervention designed to change attitudes towards people with visual disabilities (Yuker Citation1987).

Although blind people around the world and in Poland have been involving themselves in amateur drawing, sculpting and photography for a long time (see Szuman Citation1967; Kennedy and Juricevic Citation2003, Citation2006; Rothenstein, Citation2016; Niestorowicz Citation2017), their artistic activity still is often met with disbelief. Some visitors of the ‘City That Can't Be Seen’ exhibition could not quite believe that the artworks on display had been created by totally blind or very poor-sighted people, especially when it came to the photos. In our over -visualized world, it is hard to adopt any other perspective but visual (see Koca-Atabey and Öz Citation2017). The surprise of the audience was however generally positive in tone. The visitors became convinced that the blind artists in fact had great imagination and creativity. However, it is difficult to determine how far the viewers' opinions were unbiased and not patronizing. Did a high evaluation of the exhibition result from the fact that they really liked the artworks? Or perhaps they were simply surprised to learn that people with disabilities are able to do much more than just carry out their everyday activities. Francesca Martinez, a disabled performer in her interview for The Telegraph on 5 June 2014 (Vidal, Citation2014) ironically stated that it is usually enough for a blind artist to achieve anything beyond self-care skills like taking a shower or getting dressed to be considered ‘inspiring’. While in fact, for a disabled artist art is a part of who they are. Generally, they express themselves in art out of their inner drive and not to prove to others their capabilities or equality with artists without disabilities in creating art and achieving artistic recognition.

By engaging in visual arts, people with sight impairments show that the artistic creative process can be altered. They prove art is not reserved for sighted people only. Having their art exhibited, the artists with sight disabilities could demonstrate that they are active agents behind the cultural shift. Interestingly, visual arts take on a different shape in the hands of people with limited vision. They create artworks resembling rather oeuvres of professional contemporary artists than of sighted amateurs. First, these artworks are not ‘pretty’. Secondly, viewers contemplating these pieces of art focus rather on the concept presented than on the visual aspect of the artwork.

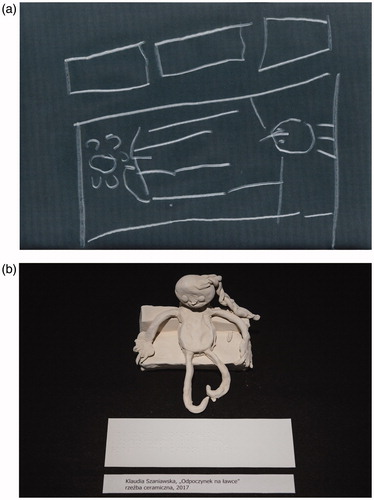

The visitors of ‘The City That Can’t Be Seen’, in the first place, learned a lot about the cognitive functioning of people with visual impairment. Careful listening to the ambient sounds of the urban space can help people who are blind not only in spatial orientation but also in taking a photo. If they want to take a picture of a tree that rustles above, they need to point the camera upwards or take a few steps back. The decision about the positioning of the photographer and the direction of a camera lens is mainly based on the sounds and noises around. The visitors found the comparison of the drawings made by the people who are congenitally blind and partially sighted very interesting. The drawings by artists who have never seen resemble children's scribbles and geometrical abstraction where objects are hardly identifiable (Szubielska, Niestorowicz, and Marek Citation2016). On the other hand, the drawings by partially sighted artists could be easily recognized and even used foreshortening. Comparing works of the same congenitally blind artist made in drawing and in sculpture was an interesting experience, too (see ). The sculptures were easily recognizable because they were three-dimensional and for a person who is blind, the forming is an effortless task as it resembles tactile perception of objects from many sides at the same time (Heller Citation2006).The content of works presented in the exhibition tells us a lot about the problems visually impaired people experience every day in a city. The visitors could learn that, for example, stairs constitute an obstacle not only for people in wheelchairs. One of the artists drew a staircase winding around a building and entitled her work ‘Try Not To Fall’. Short stories written for the tactile illustrated book often related to the difficulties with orientation in a new space or told stories about getting lost in a city. Some authors described it briefly giving only facts:

Figure 1. A scan of an embossed drawing (a), and a ceramic sculpture (b): "Rest on the Bench" made by an artist who is congenitally blind (photo by Wojciech Pacewicz).

"I was walking with my friend to the dorm. I went too far. I didn't know where I was. My friend didn't know either and we had no idea where to go. I yelled. I don't remember what. A lady from the dorm came and led us back." (Klaudia, I Took a Wrong Path)

Others, who did not want to write openly about unpleasant experience of getting lost, invented incredible stories:

"I get out at a bus stop. I am walking slowly in the darkness. I can't see anything in front of me but suddenly I get to stairs so high I can't walk down them. I am afraid. I don't know what to do. Suddenly I realize I am at the top of a skyscraper. And I hear a voice: Take a step. And I'm like: But how? It's so high! And the voice answers: Don't worry, we'll help you in a moment. But who? I feel disoriented. Finally, I take the step. And I am falling but I can feel something soft under my feet. I am flying on a cloud above Lublin!" (Agata, no title)

In conclusion, it is worth noticing how the exhibition not only changed visitors' attitudes towards visually impaired people but also the artists' self-confidence. They felt the joy of creating and embraced their own creativity and started to believe in their capabilities. They felt appreciated by having their artwork exhibited in a gallery next to well-recognized and famous contemporary artists. Paradoxically ‘the experiment’ proved that the visual arts can help normally sighted people to see the world of the persons with visual impairment.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Agata Sztorc from the Galeria Labirynt gallery for help in organizing the exhibition and Professor Val Williams for help in preparing the final version of the article.

Notes

1 The experiment referred to above was a scholarship project funded by the Minister of Culture and National Heritage, Poland.

2 The exhibition was open from 19 December 2017 to 28 February 2018.

References

- Heller, Morton A. 2006. “Picture perception and spatial cognition in visually impaired people.” In Touch and blindness: Psychology and neuroscience, edited by Morton A. Heller and Soledad Ballesteros, 49–71. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hong, Soo-Young, Kyong-Ah Kwon, and Hyun-Joo Jeon. 2014. “Children’s Attitudes towards Peers with Disabilities: Associations with Personal and Parental Factors.” Infant and Child Development 23 (2): 170–193. doi:10.1002/icd.1826.

- Kennedy, John M., and Igor Juricevic. 2003. “Haptics and Projection: Drawings by Tracy, a Blind Adult.” Perception 32 (9): 1059–1071. doi: 10.1068/p3425.

- Kennedy, John M., and Igor Juricevic. 2006. “Blind Man Draws Using Diminution in Three Dimensions. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 13 (3): 506–509. doi: 10.3758/BF03193877.

- Koca-Atabey, Müjde, and Bahar Öz (2017). “Telling about Something that You Do Not Really Know: Blind People Are Talking about Vision!” Disability & Society 32 (10): 1656–1660. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2017.1345210.

- Niestorowicz, Ewa. 2017. The World in the Mind and Sculpture of Deafblind People. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Ostrowska, Antonina. 1994. Niepełnosprawni w społeczeństwie: Postawy społeczeństwa polskiego wobec ludzi niepełnosprawnych [Disabled in Society. Attitudes of Polish Society towards People with Disabilities]. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Filozofii i Socjologii PAN.

- Reina, Raul, Víctor Lopez, Mario Jiménez, Tomás García-Calvo, and Yeshayahu Hutzler. 2011. “Effects of Awareness Interventions on Children’s Attitudes toward Peers with a Visual Impairment.” International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 34 (3): 243–248. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e3283487f49.

- Rothenstein, Julian, ed. 2016. The Blind Photographer: 150 Extraordinary Photographs from Around the World. London: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Szubielska, Magdalena, Ewa Niestorowicz, and Bogusław Marek. 2016. “Drawing without Eyesight. Evidence from Congenitally Blind Learners.” Roczniki Psychologiczne 19 (4), 681–700. doi:10.18290/rpsych.2016.19.4-2en.

- Szuman, Wanda. 1967. O dostępności rysunku dla dzieci niewidomych [On Drawing Availability for Blind Children]. Warsaw: Państwowe Zakłady Wydawnictw Szkolnych.

- Vidal, Ava. 2014. “Disability Campaigner Francesca Martinez: 'Im So Far from 'Normal' I Can Actually be Happy'.” The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-health/10872761/Disability-campaigner-Francesca-Martinez-Im-so-far-from-normal-I-can-actually-be-happy.html. London: Telegraph Media Group.

- Yuker, Harold E., ed. 1987. Attitudes towards Persons with Disabilities. New York: Springer.