Abstract

The Financial Crisis of 2008 resulted in many western economies implementing cuts in health and social care. This systematic review provides a holistic picture of the impact of austerity policy on the lives of people with learning disabilities (LD) and the collateral effects on the people who support them. Our review suggests that in the current climate of economic austerity, available funding to support people with LD is no longer aligned to their care needs. Cuts in disability services have adversely affected the well-being both of people with LD and their informal carers. Individuals with LD have lost social support and are experiencing increased social isolation. Heightened demands on family carers’ time have negatively influenced their wider roles, including parental functioning, and labour market participation. Our review provides the foundations for further discourse and research on the effects of austerity on people with LD and their family carers.

Points of interest

Austerity means that governments across the world are cutting benefits and services for everyone including people with learning disabilities

We looked at other studies and what they have said about austerity and people with intellectual disabilities

We did not find many studies - only 11 studies across the world: 4 in the Netherlands, 5 in the UK, 1 from Canada and 1 from the USA

Cuts in disability services have impacted negatively on the well-being of people with learning disabilities and their informal carers

People with learning disabilities have lost social support and opportunities for community participation. They are feeling socially isolated

Cuts to services mean that informal carers, e.g. parents, are having to increase or take on the role of caring

Introduction

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 resulted in many western economies adopting policies to reduce public expenditure in an attempt to cut the scale of their national budget deficit (Acharya et al. Citation2009). Under the political ideology that markets can adjust and become competitive during adverse financial conditions by deficit reduction policies, many countries implemented neoliberal agendas. Stringent fiscal measures included tax rises, privatisation of previously publicly owned assets and reduction of the size of the public-sector workforce. The latter inevitably resulted in rapid unemployment increases and reduced personal income for the countries’ population (Karanikolos et al. Citation2013). Moreover, according to Cylus et al. (Citation2012), European Union countries experienced disproportionate cuts across the health and social care sector.

The United Nations has argued that the cuts and lower government spending, which have resulted in reduced budget allocations for social welfare, health care, employment and education, have impacted adversely on the human rights agenda (UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Citation2016). Despite claims by some governments – such as the UK – that ‘we are all in it together’, the most vulnerable groups in society have been disproportionally negatively affected (O'Hara Citation2015). Furthermore, people with disabilities have experienced even greater negative outcomes and have apparently been disproportionally targeted by most governments’ cost-saving agendas (Grootegoed, Van Barneveld, and Duyvendak Citation2015). Recession adversely and unequally affects the participation of people with disabilities in the labour force (Livermore and Honeycutt Citation2015), and many have experienced profound challenges and obstacles to their daily lives as a consequence of welfare cuts. In countries like the United Kingdom, cuts have been implemented through reductions in benefits, and in the case of social care via tightened eligibility criteria, thereby reducing the numbers of people receiving support (McInnis, Hills, and Chapman Citation2012; Runswick-Cole and Goodley Citation2015). Similarly, in Sweden tightening of eligibility has played a part in the reduction of claimant numbers for disability benefits, falling from 66,000 to 20,000 between 2004 and 2015 (Andersen, Schoyen and Hvinden Citation2017). The education of people with disabilities has also been jeopardised. Many countries (e.g. Spain) have drastically cut funding to education resulting in schools no longer being guided by a sense of social justice but rather by a concern towards academic results. Thus, the emphasis is no longer placed on accommodating the diverse needs of students within an inclusive educational environment but on individualised competiveness (Whitburn Citation2016).

Throughout this article we use the terminology of ‘learning disability’ (LD); we recognise that elsewhere, particularly in the USA and Australia, the term ‘intellectual disabilities’ (ID) has increasingly been used. Much of this usage is in academic discourse, but in the UK the preference is generally to use learning disability. Research by Cluley (Citation2018) with focus groups of professional and lay people involved in learning disability services highlighted negative perceptions of the term ‘intellectual disabilities’ (ID) and emphasised the need for further research to explore the perceptions of this terminology by people with learning disabilities. Throughout our research we therefore use ‘learning disabilities’ (LD) to acknowledge the terminology preferred and most frequently used within the UK.

Personalisation policies are firmly linked to the independent living movement and promote self-determination and wider participation for individuals with learning disabilities (LD), and for other users of social care and support. Personalisation objectives of person-centred holistic support have become the focus of social care reform in the UK and across Europe, and given expression through Direct Payments, personalised budgets and self-directed support. However, the roll-out of such objectives coincided with the onset of global programmes of austerity, which has limited the positive impacts that personalisation could have in practice (Pearson and Ridley Citation2017). It has been suggested that governments conceal some retrenchment strategies behind this vision of creating a society in which disabled people are ‘empowered’ to gain independence (Ferguson Citation2007). In the UK, the closure of many day care centres, without any alternative provision, has meant that people with LD have progressively become more dependent on informal care from family membersthis being perversely portrayed as a useful way to help social inclusion and participation in the community (Power, Bartlett, and Hall Citation2016). Similarly, Hungary has implemented austerity measures through the framework of wider welfare reform and modernisation (Pearson and Ridley, Citation2017). In the Netherlands, the government has aimed to make care for people in their own homes the ‘norm’ through moral exhortation and increased reliance on informal social networks (primarily family carers) to provide assistance. This of course has had an impact on the lives of unpaid carers as they struggle to combine employment and other commitments with caring responsibilities (Grootegoed, Bröer, and Duyvendak Citation2013).

In countries such as the UK, expenditure cuts have resulted in increasing demands on third sector organisations, namely community and voluntary organisations, charities and social enterprises (Walker and Hayton Citation2017). Funding for these organisations has however become progressively difficult and competitive, inevitably affecting their ability to deliver services. Similarly, social service workers in understaffed and underfunded services with large caseloads may find themselves detached from their clients’ needs and may no longer actively advocate on behalf of clients or be able to provide quality services (Lipsky Citation2010), often leaving in considerable numbers so that many social services departments are unable to fill permanent posts.

The above changes have been accompanied by a rise in the volume of negative rhetoric directed towards many of those in need of welfare. The media has tended to depict people claiming disability benefits as ‘scroungers’, with increased coverage of fraudulent claims (Briant, Watson, and Philo Citation2013). At the same time those who take on informal care responsibilities are often praised or seen as heroic, while being given little practical support.

Despite the implementation of austerity measures worldwide, it is evident that approaches to cost-cutting differ largely between countries. Perhaps most notably, the UK’s continuing efforts to reduce the budget deficit have led to disproportionate consequences for those with disabilities (O’Hara Citation2015). Widespread cuts of influence have come from many directions, including cuts to housing, income, social care, and public services. This is alongside the increased cost of basic needs (e.g. utilities), and a reduction in legal aid. The cumulative impact of these has caused serious damage with some estimates that an average disabled person in poverty would experience a yearly loss of £4660, and an average person using social care would experience a yearly loss of £6409 (Duffy Citation2014).

There is mounting evidence, including from the grey literature and media, that suggests continued and intensifying problems for people with LD. There has been an ongoing discussion surrounding the calamitous effects of austerity on the well-being of people with LD. A narrative review by Flynn (Citation2017) looked specifically at the impact of austerity measures on children with LD in Ireland and highlighted that this group has been hit hard and is more susceptible to poverty. However, there is currently no systematic review to our knowledge that cumulatively provides an overview of the impact of austerity on the lives of individuals with LD, their family and carers on an international and cross-cultural level. Such a review should uncover the numerous ways the lives of people with LD have been influenced in the context of austerity in different countries with various health and social services.

Aims

The overall aim of this thematic synthesis was to build a holistic and international picture of the impact that austerity related policy has had on the lives of people with learning disabilities and the collateral effects on the people who support them (e.g. family carers, care workers) on an international level. Most specifically, it aimed to understand how financial cuts have impacted people’s daily reality, their quality of life, and also their social identity and personhood. It additionally aimed to gauge the impact of the cuts and reforms on the lives of carers. Through synthesising the available literature, it was hoped that a broader and more comprehensive overview of their experiences and challenges could be outlined. This might subsequently help us to identify the measures that have most adversely affected individuals and allow us to highlight the possible implications of these. Such knowledge could help inform current policy, and the capacity of health and care professionals to better assist individuals with LD and their families. Finally, this thematic synthesis aimed to appraise the existing literature, identify gaps and highlight potential areas of future research.

Methods

Search terminology covered two broad domains; learning disabilities and austerity. Each of the learning disability keywords shown in were searched alongside each of the austerity keywords.

Table 1. Keywords utilised in the systematic review.

Table 2. Studies included in the systematic review.

Eligibility criteria and search strategy

Inclusion criteria

To be included, articles must have addressed the impact of austerity measures on people with learning disabilities, their family carers or paid caregivers. This allowed us to exclusively focus on the perspectives of people with LD and those in direct contact with them. The viewpoint of non-frontline workers (e.g. policymakers, social care managers) was only included if integrated in the analysis with the former participants. Studies were included if they were empirical peer-reviewed research articles using qualitative, quantitative, and/or mixed method approaches, published between January 2008 and September 2017. Earlier publications were excluded, since 2008 is the year that is generally accepted as signifying the beginning of the global economic crisis. No language restrictions were applied so as to avoid English language bias. The study population had to consist of individuals with learning disabilities and/or their informal carers. Due to the limited research exploring learning disabilities and austerity, articles studying multiple disability groups including LD were included. However, great care was taken to only include information directly reported as being linked to the lives of people with learning disabilities. No age, gender or demographic restrictions were imposed on the population with disabilities, as the aim of the systematic review was to evaluate how austerity has impacted both adults and younger people.

Exclusion criteria

Articles that assessed the impact of austerity on people who work in organisations for people with LD but did not have regular direct contact with them were excluded (e.g. social care managers, policy makers). Articles that discussed welfare reforms but did not explicitly link this to austerity measures were also excluded. Grey literature was likewise excluded. While it is acknowledged that unpublished studies, a sub-category of grey literature, can counterbalance publication bias and English language bias, their methodological validity can be difficult to evaluate.

Screening process

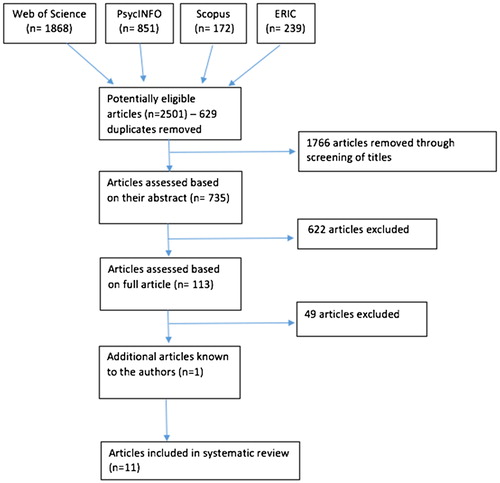

Electronic searches of PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus Web of Science and ERIC were carried out between May and August 2017. summarises the identification and selection of studies. There were a substantial number of papers that we concluded were not relevant because budget* and personalis* are popular terms within a range of research areas, although we did not want to exclude any potentially relevant studies through the removal of these terms. The search generated a large range of discussion and opinion pieces commenting on recent policies. A total of 1766 articles were excluded based on their titles and 735 were assessed based on their abstract. Of these, 583 were excluded as irrelevant to our research question.

This left a total number of 113 articles that were obtained in full texts for further assessment of eligibility. The first two authors independently reviewed these articles. Any discrepancies in the assessment were discussed with a third reviewer until consensus was reached. Ten of these articles were deemed eligible for inclusion. An additional article was recommended following consultation with other researchers in the field. Finally, the reference lists of all articles included were searched manually for additional articles that were not identified through the electronic search; however, no additional relevant articles were found (see ).

Experts in the field of learning disabilities were also asked whether they were aware of any relevant studies for this review. Whenever possible, corresponding authors were contacted for papers with insufficient details to enable a decision about inclusion: in four articles the composition of the sample of individuals with disabilities was not specified and thus it was not clear if it included individuals with LD. These articles were therefore excluded. Potentially suitable papers were further assessed against the inclusion criteria.

Data abstraction and synthesis

Using a standardised template, data from the 11 studies identified as eligible for inclusion were extracted, and the data captured were: author; date and location of study; aims of the study; participant characteristics (N, mean age, gender, and type of disability); data collection methods; data analysis approach and main findings (see ).

Results

Quality assessment

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme for systematic reviews (CASP Citation2013) was used to guide critical appraisal of the quality of included studies. This involves the assessment of both internal and external validity of the studies, and relevance of included papers based on 10 criteria. The assessment was carried out independently by the first two authors to address inter-rater reliability. Any discrepancies between scores were discussed or, where necessary, presented to a third reviewer until a consensus was reached.

Each paper was reviewed and rated as being weak (1), moderate (2), or strong (3) in relation to ten questions. A total score was calculated for each study, which could range from 8 to 24 (see ). The mean CASP score was 16.5 (range =10 to 23).

Table 3. Study quality scores based on the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP).

Overall the quality of the literature was relatively poor, often due to a lack of methodological clarity and transparency. This was mostly due to minimal descriptions of samples and/or sampling strategies employed. Thus, it was not always possible to extract demographic information about the participants of the studies, although their authors were contacted. A further shortcoming was minimal reflexivity in qualitative studies. Thus, researchers had failed to acknowledge their role in the creation of knowledge, to carefully self-monitor the impact of their biases, beliefs, and personal experiences on their research. Also, some studies used research tools that were not adequately described. Most importantly, the studies tended to include broad and heterogeneous participant groups. Therefore, the participants were not solely limited to individuals with LD and the studies did not generally include a separate analysis for this specific population. Nevertheless, great care was exercised to ensure that the themes that emerged were drawn only from the data relating to individuals with LD and their carers.

Thematic synthesis

The technique of thematic synthesis was used to blend the qualitative data obtained and to answer questions regarding people’s experiences. This entailed line-by-line coding of the results section of each of the included studies, development of ‘descriptive themes’, and generation of ‘analytical themes’. The development of descriptive themes demands the reviewer to remain close to the primary studies. In contrast, when developing analytic themes the reviewer goes beyond the primary studies, generating new interpretative explanations. This approach was chosen in order to look further than the findings of specific studies and identify recurrent themes that would deepen our understanding of a specific topic and help to generate new insight (Thomas and Harden Citation2008). Furthermore, greater levels of generalisability could be provided by drawing on a wider range of participants and settings.

Study characteristics

As already described, 11 articles fulfilled the reviews inclusion criteria. The vast majority of the studies employed a range of qualitative techniques (e.g. interviews, focus groups, questionnaire surveys with free-text response), and four used structured questionnaires to complement the qualitative data (Brimblecombe et al. Citation2017; Needham Citation2014; Stalker et al. Citation2015). Articles encompassed research from the Netherlands, the UK, the United States of America and Canada. They were published between 2012 and 2017 and drew on nine different samples, thus three studies used the same participants. The age of the participants was not always specified nor was their gender. Of those stating age, it ranged from 10 to 91 years.

Analyses employed by the studies included thematic analysis and thematic content analysis. The impact of austerity measures on the lives of people with LD and their carers was explored through three perspectives: that of the people with LD, the carers’ perspective, and through frontline workers’ and managers’ viewpoints. Each of those viewpoints helped uncover the cumulative impact of austerity on the lives of people with LD and their carers.

Impact of austerity measures on people with learning disabilities

Through the narratives of people with LD, their carers, and also of frontline workers in the field, a comprehensive picture could be synthesised which revealed the detrimental impact of austerity measures on the lives of people with LD as well as on their carers. One main theme emerged and two subthemes. People with LD experienced a range of loss. This was not restricted to the loss of financial security, as those with LD also described the loss of independence, choice and social participation in their daily lives. Additionally, the austerity measures negatively affected the quality of care they were receiving.

Loss

Deprivation of autonomy, choice, and social participation

Through the accounts of people with LD it was apparent that their autonomy and independence were maintained through and contingent on the support of their care workers. The loss of this care and support necessitated increased reliance on family members and volunteers, which consequently led to feelings of reduced self-sufficiency and independence. They reported that the input of care and support workers enabled them to make choices and to exert independence, which was greatly valued. Service provision of this kind provided people with some power over their own life, and while they might not have been entirely independent, they maintained that they had a degree of control over how the support was provided and the form it took. In contrast, relying primarily on relatives or volunteers was typically experienced as restricting people’s autonomy and confining their dignity and independence. People with LD felt that being dependent on their family’s help disturbed the balance of their relationship, rendering them passive recipients and subordinate. This was reflected, for example, in a study from the Netherlands, where a 51-year-old interviewee with learning disabilities explained the reason for avoiding help from his father and how paid care helped him maintain a sense of power over his own life: “I think that my father would become overly involved, and then I would feel overly very controlled. I think an outsider performs the job, it is different, more neutral.” (Grootegoed and Van Dijk Citation2012). Participants felt that additional burdens on their relatives and carers would have a detrimental impact on their pride and sense of freedom. Also in the Netherlands, the substitution of volunteerism was perceived as creating challenges and can entail a lack of choice from the care recipients’ point of view, as this comment illustrates: “Yes, well if it doesn’t click with a paid care-giver, you can easily request another person. But if it is a volunteer, that is much more difficult” (Grootegoed and Tonkens Citation2017). In contrast to the professional relationship with paid service workers, the relationship with volunteers and family members was typically perceived as one characterised by appreciation and gratitude, which would unavoidably create an unequal power relationship. Volunteerism was therefore sometimes approached with scepticism, while also raising questions over the skills, motivation and dedication of those volunteering.

Other research conducted in the Netherlands also found that people with LD were deprived of choice through lack of confidence in the appeal process against service reductions, and experienced this as socially stigmatising. Participants asserted that lodging an appeal against reductions in care would be shameful and viewed it as an admission of helplessness. The fear of social disgrace left them utterly exposed to the fiscal cuts, as this comment highlights: “My care provider advised me to make an appeal, but they are just the new rules. I am not going to beg for care, I want to be helped, but in a normal way, I do not need preferential treatment. I am just like every other person” (Grootegoed et al. Citation2013).

The autonomy of people with disabilities was further jeopardised by employment insecurity as well as limited work opportunities. The rising instability in the labour market in combination with negative perceptions of disability limited the choices they had. This was highlighted by a participant in the UK: “I feel as though there’s a lot of resistance, because of disabilities, there’s a lot of resistance from employers” (Hamilton et al. Citation2017).

In addition, people with LD who experienced loss of service and support were deprived of opportunities for social participation and forced into social isolation. Due to a lack of funding and support, people often experienced becoming house-bound and segregated from their peers. While the discourse of personalisation emphasises that service users need more choices and access to a wider range of purposeful activities, in practice a lack of funding renders that unattainable for many. One survey of respondents in England explained that: “People’s budgets are not as big as they thought and once basic care needs are met there is often not a lot left for what I would class as social care. The result is more people pulling out of services and becoming more isolated.” (Needham Citation2014). The number of activities people were engaged in and the social contact they had was inevitably reduced. In a further study undertaken in England, participants pointed out (in relation to self-advocacy groups): “People who live in residential places don’t really have a choice about whether they can go to a meeting or not. There is no support worker to take them. And the creative arts groups are struggling to get money, there’s less people at those meetings” (Bates et al. Citation2017). A Scottish study also found the cuts reduced the recreational activities youths with disabilities could attend and left them more isolated from their peers (Stalker et al. Citation2015).

Reduced funding for services can also mean that support workers are stretched more thinly. A service worker in Toronto, Canada emphasised a direct association between support workers’ heavier workload and the isolation and loneliness of the people they support: “I have individuals that complain to me…or complain to my supervisor that they can’t get out and they can’t do things. I had an individual that was like begging me to take him out for a walk that day. Like how sad is that?…You just don’t have the time to spend with them and even sometimes have a conversation about how their day was” (Courtney and Hickey Citation2016).

Studies also found that people with learning disabilities were increasingly deprived of meaningful social participation through the closure of day services and a reduction in day centre provision. As a result, their social network and friendship groups had declined sharply in size. As a support worker in the UK explained, the people their clients had daily contact with abruptly disappeared from their lives: “And then these places closed and people weren’t given contact details for people they’d lived with for years and years. So their friends just kind of disappeared off the edge of a cliff it felt like I think.” (Hamilton et al. Citation2017). This increase in isolation and dependency can be seen as a deprivation of human rights for people with LD.

Lowering of care quality

Another major theme to emerge across almost all of the studies was the insufficient quality of care provision that was provided due to austerity-driven reforms. Due to budget restraints, service workers were given excessive workloads, which affected the quality of support they could provide as their time was spread more thinly between clients. As paid staff workers in Ontario, Canada pointed out, priority was no longer given to people’s needs, and instead new policies dictated that they concentrate “more on the documentation and paperwork than … on the care of individuals” (Courtney and Hickey Citation2016). This was also acknowledged by a family carer in the UK: “It’s not necessarily the carers themselves – their fault, but they’ve probably got, you know, ten people to get up in the morning or whatever and. they’ve been allocated three quarters of an hour to get that person. up, washed, dressed, fed, and – and everything and, you know, three quarters of an hour is not – it’s not sufficient” (Brimblecombe et al. Citation2017). Similarly, in the USA carers attested to the fact that due to cuts, the care their relatives or their loved ones were receiving was no longer person-centred: “So, you get the sense of the family, that your person that you’re taking care of has to fit their box as opposed to having … some thoughts about what would really work well during the day for an individual.” (Williamson et al. Citation2016). Parents of young people with disabilities in Scotland argued that the social workers failed to advocate for the rights of their children, and the support they were receiving did not meet the expectations of their family carers (Stalker et al. Citation2015).

Where volunteers were being substituted for paid support workers, they were sometimes seen as inadequately prepared for their role, and lacking the attributes that would make them appropriate carers. This was demonstrated by findings from the Netherlands: “No, a 19-year-old student is way too busy with himself. He cannot support a 12-year-old disabled boy. Moreover, as a student, he still has to learn and cannot care for a disabled boy. He may have good intentions as a volunteer, but he himself is a student” (Grootegoed and Tonkens Citation2017).

This lowering of care quality was also seen through changes in support services. These included service closures, and reductions in the numbers of hours offered to those with LD. One participant in the UK highlighted the lack of services: “it’s only on a Wednesday so that’s the only support I’ve got really at the moment. I’ve just got to rely on that, there’s nothing else” (Hamilton et al. Citation2017). Such reductions in hours and services have a substantial influence on the lives of those with LD, and their families. This was also found in research that took place in Scotland, where participants explained that “the reality for [families] trying to get [their] children back into a routine after that, it’s like hell” (Stalker et al. Citation2015). Increased charges to access services, lack of funds to support facilities, and raised eligibility thresholds were further indications of the detrimental impact of these cuts. It was also evident that services were becoming more limited to crisis intervention, than providing a preventative service despite prevention being widely endorsed as a core objective of social care reform.

Impact of austerity measures on informal carers

Being abandoned by the system

The austerity measures deeply affected the lives of family carers. Through their testimony, it is evident that many felt abandoned by the system and their countries’ government. For instance, carers in Scotland felt the government perceived the needs of their loved ones as ‘a low priority’ (Stalker et al. Citation2015). They were faced with a cumbersome bureaucratic system which was bewildering and left them uncertain about who they should turn to. This was also demonstrated by studies in the UK where carers were not aware of what services were available or what support their loved ones would be eligible for: “I don’t know where you go for the services now, to be honest with you” (Brimblecombe et al. Citation2017).

Higher levels of demand and increased caring hours were transferred to unpaid family carers, who were expected by governments to altruistically undertake this customary role. An assessor quoted by Grootegoed et al. (Citation2015) summarised the phenomenon: “Very simply put, the municipality has set these rules and we [the assessors] just assume that customary care is provided. I am not going to judge if they [the relatives] have enough time to do it. Because it is not my task. I also say to people that I am not going to decide how they should resolve it [customary care tasks], only that they should resolve it.” In other words, it was expected that the needs of people with disabilities would be met within the home and within the realm of the family; while services would only provide reactive support instead of proactive, intervening only when the family and their carers reached breaking point. “It always comes down tae [to] money and it seems in a lot of situations that they only, if they do anything they only do it when somebody gets to crisis point” (Stalker et al. Citation2015).

All carers in the studies were aware that the governments’ money-saving policies took precedence over the needs of their relatives. Carers were similarly expected to prioritise their unpaid-carer responsibilities over the obligations they had towards their employment, and to other members of their family. In other words, they had to step in to deal with the shortfall in service provision. Due to people being ineligible for care or because of concerns about the poor quality of care being provided, carers took upon themselves the responsibilities that were shared with services. Carers reported that mistrust of the system left them no alternative but to provide care themselves.

Family carers were trying to ‘manage’ without the help of state intervention, while suffering detrimental consequences to their well-being, their social relationships and their families. The substantial demands on family carers were exacerbated by the lack of respite available. This left carers overwhelmed, as highlighted by a carer in the USA: “it reduces what she can do …so her opportunities are being limited and your ability to take a break and recharge your batteries is being also” (Williamson et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, the all-consuming role of the carer took over and strained other family relationships, reducing the amount of attention and time they had with other family members: “I found it was a good break not just for myself but for my other son as well …when we could go out and we could do things we couldn’t normally do with David … or even just have a chill out day watching DVDs” (Stalker et al. Citation2015).

Discussion and conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review on the effects of recent global austerity measures on the lives of people with learning disabilities. The small number of empirical studies that were identified, and the limited numbers of participants indicates the scarcity of research to date on this important area of analysis. Only 11 articles met the inclusion criteria for this review which were purposefully broad in order to capture as many articles as possible.

Our review suggests that in the current climate of economic austerity, the funding that is made available to support people with LD is increasingly poorly aligned to the care needs of this population. Cuts in disability services seem to have affected the well-being both of people with LD and of their informal carers, on whom the retrenched system is increasingly relying to meet the shortfall in care provision. The narrative testimonies of participants in the research studies provided extensive accounts of multiple dimensions of loss due to austerity. Such losses were evident not only in economic terms, but also in reduced social networks and participation, and in consequent increased isolation. Furthermore, austerity measures introduced in the provision of care and support increased dependency on family caregivers, and contributed to a loss of autonomy. This thematic synthesis also suggests that budgetary constraints have negatively affected the quality of care provision as resources are spread more thinly.

‘Social participation’ refers to involvement in activities and interaction with networks of people. It is regarded as an important contributor to the quality of life of people with learning disabilities (Schalock Citation2004), as it provides opportunities for developing friendships, competencies, and identity. However, it is well documented in the literature that people with LD do not have the same opportunities to develop and engage in interpersonal relationships and are often socially isolated (Sango and Forrester-Jones Citation2017). The loss of services and thus collective spaces for people with learning disabilities is important to consider in terms of their sense of belonging and self-identity. The concept of belonging is multifaceted and is argued to involve attachment, value, and “a sense of insiderness and proximity to ‘majority’ people, activities, networks and spaces” (Hall Citation2010). Our review suggests that such isolation is further exacerbated by austerity measures that have led to reductions in resources and staff availability, and the closure of collective facilities, which have served to constrain community participation.

Family carers typically felt that austerity measures had negatively impacted on information about entitlements that were readily available and transparent in the past. Furthermore, carers described how increased responsibilities and financial burdens were accumulating for them as they assumed increasing caring responsibilities. The lack of carer support from statutory services resulted in carers having increasing demands on their time, which negatively influenced their wider roles including parental functioning, and labour market participation. This was accompanied by increased stress levels and worries. As caring responsibilities were no longer shared, informal caregivers were in greater danger of burnout and emotional exhaustion. This, despite the literature which has pointed out that carers’ readiness and ability to continue caring for a relative with LD should not be arbitrarily presumed and that the state should provide services that help to maintain their health and well-being (Seddon et al. Citation2006).

Limitations

Although our review presents a primary account of the impact of austerity on people with learning disabilities, on the basis of the literature it is difficult to gauge the full extent of impact that all the stakeholders might experience, and there are several limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the findings. While a systematic searching method was employed that utilised a non-English language restriction, no relevant non-English papers were detected. Thus, the studies were carried out in the UK, Canada, USA and the Netherlands and although their findings obviously transcend the borders of these specific countries, there appeared to be a dearth of literature exploring the impact of austerity on the countries that were most affected by the economic crisis (in particular the so-called peripheral European countries of Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain), countries that were forced to take drastic measures that inevitably affected vulnerable socioeconomic groups. The picture of the impact of austerity measures in low-income countries is therefore incomplete. The absence of published empirical research studies in these countries may be due to a range of reasons. The lack of studies could be associated with limited research funding and lack of human resources (there has been a recent ‘brain-drain’, reported to have exacerbated the human resource gap in countries experiencing austerity, according to Grubel (Citation2006). However, taking into consideration the number of studies that have addressed the general populations’ concerns in time of austerity (e.g. increased suicide rates among the general population in these countries, Rachiotis et al. Citation2015), it is likely that due to the recession the lives of people with disabilities have been pushed to the margins. This leads us to question whether the economic crisis has allowed the governments to neglect their duties and human rights responsibilities towards individuals with LD (Biel Portero Citation2012).

Participation bias was also a potential issue in the majority of the included studies, since most of the samples were not statistically representative of the general population under study and, therefore, the generalisability to the rest of the community is limited. Furthermore, a purposive sample which included only those who attested to having experienced the negative side-effects of the economic recession was typically used, which may have excluded the voices of those who had mixed or even positive views of the recent economic/political developments. Finally, specific groups were entirely absent from this body of research, e.g. the voices of individuals with LD that lack capacity to consent appeared to be missing in the literature.

Despite a number of limitations, this review provides the first synthesis of evidence pertaining to the important topic of the impact of austerity on welfare and well-being of people with LD and raises a number of important questions and provides emerging findings. It provides the foundations for further discourse and research on topics related to the effects of economic crisis on people with LD and their family carers, whether this impact has widely undermined the aspirations of achieving person-centred care and support, enabling people to exercise choice, control and self-determination in their daily lives, and whether this will be a temporary setback that may be relieved by the future relaxation of austerity measures, or if this becomes a permanent restriction limiting personalisation and independence for generations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acharya, V., T. Philippon, M. Richardson and N. Roubini. 2009. “The Financial Crisis of 2007–2009: Causes and Remedies.” Financial Markets, Institutions & Instruments 18 (2): 89–137.

- Andersen, J. G., M. A. Schoyen, and B. Hvinden. 2017. “Changing Scandinavian Welfare States: Which Way Forward?” In After Austerity: Welfare state transformation in Europe after the great recession, edited by Peter Taylor-Gooby, Benjamin Leruth, and Heejung Chung, 89–114. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bates, K., D. Goodley, and K. Runswick-Cole. 2017. “Precarious Lives and Resistant Possibilities: The Labour of People with Learning Disabilities in Times of Austerity.” Disability & Society 32 (2): 160–175.

- Biel Portero, I. 2012. “Are There Rights in a Time of Crisis?” Disability & Society 27 (4): 581–585.

- Briant, E., N. Watson, and G. Philo. 2013. “Reporting Disability in the Age of Austerity: The Changing Face of Media Representation of Disability and Disabled People in the United Kingdom and the Creation of New ‘Folk Devils’.” Disability & Society 28 (6): 874–889.

- Brimblecombe, N., L. Pickard, D. King, and M. Knapp. 2017. “Barriers to Receipt of Social Care Services for Working Carers and the People They Care for in Times of Austerity.” Journal of Social Policy 29: 1–19.

- CASP, U. 2013. “Critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) qualitative research checklist: 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research.” Accessed 10 October 2017. http://Media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf

- Cluley, V. 2018. “From ‘Learning Disability to Intellectual Disability’ – Perceptions of the Increasing Use of the Term ‘Intellectual Disability’ on Learning Disability Policy, Research and Practice”. British Journal of Learning Disability 46: 24–32.

- Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2016. “Inquiry concerning the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland carried out by the Committee under the article 6 of the Optional Protocol of the Convention. 6 October 2016. CRPD/C/15/R.2 Rev1.” Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Accessed 10 October 2017. http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CRPD/CRPD.C.15.R.2.Rev.1-ENG.doc

- Courtney, J., and R. Hickey. 2016. “Street-Level Advocates: Developmental Service Workers Confront Austerity in Ontario.” Labour/Le Travail 77 (1): 73–92.

- Cylus, J., P. Mladovsky, and M. McKee. 2012. “Is There a Statistical Relationship Between Economic Crises and Changes in Government Health Expenditure Growth? An Analysis of Twenty‐Four European Countries.” Health Services Research 47 (6): 2204–2224.

- Duffy, S. 2014. “Counting the cuts.” Accessed 13 June 2018: http://www.centreforwelfarereform.org/library/by-az/counting-the-cuts.html

- Ferguson, I. 2007. “Increasing User Choice or Privatizing Risk? The Antinomies of Personalization.” British Journal of Social Work 37 (3): 387–403.

- Flynn, S. 2017. “Perspectives on Austerity: The Impact of the Economic Recession on Intellectually Disabled Children.” Disability & Society 32 (5): 678–700.

- Grootegoed, E., C. Bröer, and J. W Duyvendak. 2013. “Too Ashamed to Complain: Cuts to Publicly Financed Care and Clients’ Waiving of Their Right to Appeal.” Social Policy and Society 12 (3): 475–486.

- Grootegoed, E., and E. Tonkens. 2017. “Disabled and Elderly Citizens' Perceptions and Experiences of Voluntarism as an Alternative to Publically Financed Care in the Netherlands.” Health & Social Care in the Community 25 (1): 234–242.

- Grootegoed, E., E., Van Barneveld, and J. W. Duyvendak. 2015. “What is Customary About Customary Care? How Dutch Welfare Policy Defines What Citizens have to Consider ‘Normal’ Care at Home.” Critical Social Policy 35(1): 110–131.

- Grootegoed, E., and D. Van Dijk, 2012. “The Return of the Family? Welfare State Retrenchment and Client Autonomy in Long-Term Care” Journal of Social Policy 41 (4): 677–694.

- Grubel, H. 2006. The Brain Drain: Determinants, Measurements and Welfare Effects, Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press.

- Hall, E. 2010. Spaces of Social Inclusion and Belonging for People with Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 54 (1): 48–57.

- Hamilton, L.G., S. Mesa, E. Hayward, R. Price and G. Bright. 2017. “‘There’s a Lot of Places I’d Like to go and Things I’d Like to Do’: The Daily Living Experiences of Adults with Mild to Moderate Intellectual Disabilities During a Time of Personalised Social Care Reform in the United Kingdom.” Disability & Society 32 (3): 287–307.

- Karanikolos, M., P. Mladovsky, J. Cylus, S. Thomson, S. Basu, D. Stuckler, J.P. Mackenbach, and M. McKee. 2013. “Financial Crisis, Austerity, and Health in Europe.” The Lancet 381 (9874): 1323–1331.

- Lipsky, M. 2010. Street-Level Bureaucracy, 30th ann. ed.: Dilemmas of the individual in public service. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Livermore, G. A., and T. C. Honeycutt. 2015. “Employment and Economic Well-Being of People with and Without Disabilities Before and After the Great Recession.” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 26 (2): 70–79.

- McInnis, E. E., A. Hills, and M. J. Chapman. 2012. “Eligibility for Statutory Learning Disability Services in the North‐West of England. Right or Luxury? Findings From a Pilot Study.” British Journal of Learning Disabilities 40 (3): 177–186.

- Needham, C. 2014. “Personalization: From Day Centres to Community Hubs?” Critical Social Policy 34 (1): 90–108.

- O'Hara, M. 2015. Austerity bites: A journey to the sharp end of cuts in the UK. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Pearson, C., and Ridley, J. 2017. “Is Personalization the Right Plan at the Wrong Time? Re-thinking Cash for Care at a time of Austerity”. Social Policy & Administration 51 (7): 1042–59.

- Power, A., R. Bartlett, and E. Hall. 2016. “Peer Advocacy in a Personalized Landscape: The Role of Peer Support in a Context of Individualized Support and Austerity.” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 20 (2): 183–193.

- Rachiotis, G., D. Stuckler, M. McKee, and C. Hadjichristodoulou. 2015. “What has Happened to Suicides During the Greek Economic Crisis? Findings from an Ecological Study of Suicides and their Determinants (2003–2012).” BMJ Open 5 (3): e007295.

- Runswick-Cole, K., and D. Goodley. 2015. “Disability, Austerity and Cruel Optimism in Big Society: Resistance and “The Disability Commons”. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 4 (2): 162–186.

- Sango, P. N., and R. Forrester-Jones. 2017. “Spirituality and Social Networks of People with Intellectual and Developmental Disability.” Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 43 (3): 274–284.

- Schalock, R. L. 2004. “The Concept of Quality of Life: What We Know and Do Not Know.” Journal of Intellect Disabilities Research 48 (Pt 3): 203–216.

- Seddon, D., C. Robinson, C. Reeves, Y. Tommis, B. Woods, and I. Russell. 2006. “In Their Own Right: Translating the Policy of Carer Assessment into Practice.” British Journal of Social Work 37 (8): 1335–1352.

- Stalker, K., C. MacDonald, C. King, F. McFaul, C. Young, and M. Hawthorn. 2015 “We Could Kid on That This is Going to Benefit the Kids But no, This is About Funding”: Cutbacks in Services to Disabled Children and Young People in Scotland.” Child Care in Practice 21 (1): 6–21.

- Thomas, J., and A. Harden. 2008. “Methods for the Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research in Systematic Reviews.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 8 (1): 45.

- Walker, C. M., and J. W. Hayton. 2017. “Navigating Austerity: Balancing ‘Desirability with Viability’ in a Third Sector Disability Sports Organisation.” European Sport Management Quarterly 17 (1): 98–116.

- Whitburn, B. 2016. “The Perspectives of Secondary School Students with Special Needs in Spain During the Crisis.” Research in Comparative and International Education 11 (2): 148–164.

- Williamson, H.J., E.A. Perkins, A. Acosta, M. Fitzgerald, J. Agrawal, and O.T. Massey. 2016. “Family Caregivers of Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Experiences with Medicaid Managed Care Long‐Term Services and Supports in the United States.” Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 13 (4): 287–296.