Abstract

Parents of disabled children face many challenges. Understanding their experiences and acknowledging contextual influences is vital in developing intervention strategies that fit their daily realities. However, studies of parents from a resource-poor context are particularly scarce. This ethnographic study with 30 mothers from a South African township (15 semi-structured interviews and 24 participatory group sessions) unearths how mothers care on their own, in an isolated manner. The complexity of low living standards, being poorly supported by care structures and networks, believing in being the best carer, distrusting others due to a violent context, and resigning towards life shape and are shaped by this solitary care responsibility. For disability inclusive development to be successful, programmes should support mothers by sharing the care responsibility taking into account the isolated nature of mothers’ lives and the impact of poverty. This can provide room for these mothers to increase the well-being of themselves and their children.

Points of interest

Research on mothers with a disabled child living in poverty is limited. Yet understanding their specific experiences is important to know how best to support them.

This research studied the daily lives of 30 mothers from a South African poor urban area.

Our data revealed that mothers in this area predominantly care for their disabled child on their own, in an isolated manner. As this proves to be quite challenging, it often harms the mothers’ well-being.

A very unsafe environment and poverty are important factors which cause mothers to lead these rather isolated lives whilst caring for their child.

The research recommended that institutions who aim to support these mothers should invest time in reaching out to them, focus on building trust, and invest in support services such as peer support groups, family care workshops and day-care centres.

Introduction

Parents of disabled children are known to face many challenges on a day-to-day basis. In particular, mothers of a disabled child experience more psychological and physical issues than other mothers (McConkey et al. Citation2008). Research has also shown that caring for a disabled child has a deep impact on a mother’s financial resources and social relationships (Chiang and Hadadian Citation2007; McConnell et al. Citation2015). Although there is ample research on the consequences of caring for a disabled child, there is little research on mothers with a disabled child living in poverty, let alone those living in low and middle-income countries. Our recent literature review reveals fewer than 30 articles investigating the experiences of parents living in resource-poor settings, over half of which are from African countries (Van der Mark et al. Citation2017). We argue that an in-depth understanding of how mothers value, experience, and enact their lives within a poor socio-economic context is vital in order to achieve full disability-inclusive development.

Disability-inclusive development ‘is based on the premise that disability justice should be an integral part of socio-economic development efforts and should not be seen as peripheral to society’ (Van der Mark et al. Citation2017: 1188). Although research on the relationship between disability and poverty has been extensive and instrumental in designing such disability-inclusive strategies (for example, Mitra, Posarac, and Vick Citation2013; Palmer Citation2011), the experiences of mothers with disabled children from a poor socio-economic context are still understudied. Understanding their realities, we argue, is important in order to formulate nuanced and sensitive policies that recognize the carers’ personal or socio-economic constraints to provide care. For example, policies aiming at inclusive education are likely to fall short in resource-poor contexts due to carers’ financial or transport constraints.

There is thus a need for a detailed ethnographic understanding of ‘the local, complex, diverse, dynamic, uncontrollable, and unpredictable realities’ (Chambers 2010, 3) of mothers of a disabled child living in poverty. This approach both gives voice to and amplifies these women’s perspectives, while also recognizing the local context and shedding light on the impacts of poverty. This, in turn, could assist in the development of useful, applicable, and appropriate disability-inclusive development and poverty-reduction strategies in these contexts (Grech 2009; Groce et al. Citation2011). In this regard, the present article reflects on the ethnographic results of a year-long research project with 30 mothers of disabled children living in the poor urban settlement of Khayelitsha, near Cape Town in South Africa.

Disabled children and their families are among the most marginalized groups in South African society. The South African government has made substantial progress in enacting a progressive legislative framework that includes (female) carers, families, and adults and children with disabilities (DSD, DWCPD, and UNICEF Citation2012; Philpott Citation2006; Seekings and Nattrass Citation2014). Important pieces of legislation include those receiving special needs education, social assistance, and free healthcare. Likewise, South Africa’s civil society is extensive with numerous non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working with or lobbying for marginalized groups in society. However, the strategic implementation of policies and effective programming, advocacy, and monitoring remains insufficient, while poverty-reduction policies largely fail to reach disabled children and their families (see DSD, DWCPD, and UNICEF Citation2012).

This article aims to provide an in-depth understanding of the perspectives and experiences of South African mothers living in poverty with a disabled child, using a multidimensional understanding of poverty (Alkire 2011; Sen Citation1999), followed by the implications of our findings for the development of an effective policy framework.

Conceptual lens

Most studies on parents conceptually focus on the negative impact (burden, stress, well-being, challenges, and unmet needs) of caring for a disabled child (Neely-Barnes and Dia Citation2008). McConkey et al. (2008) found that parents often experience a range of negative emotions concerning their child, such as grief, anger, and depression (cf. Azeem et al. Citation2013; Bannink, Van Hove, and Idro Citation2016; Gona et al. Citation2011; Oelofsen and Richardson Citation2006; Taanila et al. Citation2002; Wang, Michaels, and Day Citation2011). Other studies have shown that they also face a physical burden, caused by factors including lack of sleep, having to carry the child, and stress, as a result of which headaches, fatigue, and muscular pain are common among carers (Chang and McConkey Citation2008; Kimura and Yamazaki Citation2013). Additionally, various authors have documented the daily challenges for mothers including the time-consuming process of engaging with medical and educational services, lack of information on disability, loss of income due to providing 24-hour care, and limited social support (Gona et al. Citation2016; Raina et al. Citation2005; Resch et al. Citation2010; Yagmurlu, Yavuz, and Sen Citation2015). However unintentional it may be, this ‘exclusively negative focus’ (Green 2007, 150) can be seen as a form of ‘misery narrative’ in which ‘the assumption seems to be that if the grim realities’ (Beresford Citation2016, 423) of a certain population group are revealed to policy-makers, then something will be done about it.

Counterbalancing this negative focus, some researchers have used a different conceptual perspective (Green 2007; Ryan and Runswick-Cole Citation2008), which emphasizes the benefits of parenting a disabled child and the active coping strategies that mothers develop. For example, mothers report feelings of joy and pride, personal development, and better family functioning as positive effects (Green 2007; Heiman Citation2002; Kayfitz, Gragg, and Orr Citation2010; Park and Chung Citation2015). They also actively seek social, medical, and educational support, learn new skills, and go through a process of acceptance to cope with parenting (Huang, Chen, and Tsai Citation2012; Plant and Sanders Citation2007; Saloojee et al. Citation2007; van der Mark and Verrest Citation2014; Ylvén, Björck-Åkesson, and Granlund Citation2006).

However, the few studies that exist on mothers living in resource-poor contexts point to the context-dependent nature of care provision. For example, based on research in Zimbabwe, Van der Mark and Verrest (Citation2014) have documented how social exclusion and political and cultural issues constrain caring strategies, increase stress and physical discomfort, and reduce available support. Studies from, among others, Uganda, South Africa, and Sri Lanka share similar findings (cf. Hartley et al. Citation2005; Philpott and McLaren Citation2011; Wijesinghe et al. Citation2015). Hence, in this article, we adopt a broader conceptual lens showing mother’s experiences in all their complexity; including the negative and positive experiences as well as the societal context.

Methods

This article presents the ethnographic results of 15 semi-structured interviews and 24 participatory group sessions, which are nested in a two-year participatory action research project with mothers of disabled children from the poor urban area of Khayelitsha in South Africa. The intervention results will be reported separately.

Setting

Khayelitsha is a predominantly black African township near Cape Town with approximately 400,000 residents and high levels of violent crime and poverty (Brunn and Wilson Citation2012; Cluver and Orkin Citation2009; Seekings Citation2013; Terreblanche Citation2002). A very large number of inhabitants are first-generation urban dwellers who migrated to Cape Town from the rural Eastern Cape after 1986 when the apartheid law of ‘influx control’ was abolished. The unemployment rate in Khayelitsha is about 40% and about half of the population is in the poorest quintile for Cape Town, while most of the rest are in the second poorest. The annual median income in the last census in 2011 was R20,000Footnote1 per household. About 45% of inhabitants live in formal housing, and the rest in informal shacks (Seekings Citation2013). Such shacks are usually built by the inhabitants themselves, with wood, corrugated iron sheets, and other cheap materials. These dwellings range in size, depending on the size of the family and of the plot, as well as of the material available. Shacks have no running water and shack dwellers use central water points and communal toilets. There is a reasonable range of social and medical services, but because of the high number of users these are often difficult to access, with long waiting periods, and are, at times, ineffective.

These conditions and circumstances are reflected in the lives of the participating women and the disabled children for whom they care. While they can theoretically use the more extensive care infrastructure in Cape Town, the isolated nature of Khayelitsha, 25 kilometres from the city centre, has a severe impact on the accessibility of such services. In addition, in the more traditional parts of South African society, women are the ones mainly responsible for providing care for their family members, including their husbands, the children, the elderly, and people with disabilities (Gordon, Roberts, and Struwig Citation2013). Moreover, there are stigmas surrounding disability, and cultural beliefs that the mother or the child might have been cursed or bewitched (Mathye and Eksteen Citation2016). Such beliefs invariably affect the extent to which other community members are supportive of the carer and the child. It is in this context that the participating mothers care for their disabled child and go through daily life.

Sampling procedures

This study used a purposive sample. First, access was gained with carers making use of a reputable day-care centre for disabled children.Footnote2 Since carers have limited access to services in Khayelitsha, efforts were made to include carers from the wider community. Through the assistance of women community leaders and by word of mouth, 53 individual carers from Khayelitsha were invited to participate. The inclusion criteria were for the respondent to be: a female resident of Khayelitsha; over the age of 18 years; and the primary carer (not necessarily the biological mother) of a child with any type of disability under the age of 18 years.

Study respondents

Thirty isiXhosa-speaking women caring for a disabled child (57% response rate) participated, of whom seven had their child placed at the day-care centre. The group included 26 biological mothers, three grandmothers, and one sister.Footnote3 Four of them, aware of the age limitations for the child, wanted to participate despite their child being over 20 years old. The researchers decided not to refuse them, following the participatory nature of this research.

Data collection

Data were collected between September 2015 and September 2016. In 24 group sessions (approximately 2.5 hours) the mothers’ daily experiences were explored using creative and participatory methods such as drawing a daily pie chart in which women indicated how much of their time is spent on each daily activity; ranking daily activities in terms of easiest and hardest; ranking the accessibility of basic necessities such as food and housing; and drawing social atoms in which women specified the social support they received. These methods provided visual representations of daily experiences which were used to spark meaningful conversations. As expected with a participatory action research project, and with respect for the complex daily lives of the women, respondents’ attendance was fluid and flexible. Mothers could join or leave the project at any stage. In the end, 30 mothers had participated in one or more sessions. The majority joined between 2 and 10 times. Six mothers took part in more than 10 sessions. Eight respondents attended a session only once. Attendance ranged from 4 to 14 participants. The average participation number was eight. If reasons were given for absence, these mostly revolved around sick children, family ritual obligations, or household responsibilities.

In addition, semi-structured interviews (n = 15) lasting from 28 to 66 minutes were conducted based on voluntary response until initial data saturation. All interviews and group sessions were tape-recorded. A local staff member from the day-care centre was present for translation. Journal notes serving as complementary data were taken after each group session.

Given the main researcher’s white western background, several measures were taken to enhance the cultural sensitivity and local relevance of the project. One local NGO director and one local academic researcher acted as on-call advisors. Via a disabled people’s organization, a pilot session with 10 isiXhosa mothers of disabled children was undertaken prior to the research project. Multiple advice sessions were conducted with professional and academic experts in the field throughout the year. The translator’s extensive experience with mothers and their disabled children, and her knowledge about cultural, language, and religious issues were indispensable. Lastly, the main researcher spent a considerable amount of time informally with the participants through house visits, shared lunches, and group activities. This helped to establish relationships of trust and contributed to gaining in-depth insights.

Scientific validity was further increased by prolonged observation in Khayelitsha, extensive triangulation, involving participants in review and analysis, and analytical discussions with the research group. Detailed descriptions of the context(s), activities, and procedures of the research process were also recorded, and a systematic research administration was kept (Stringer 2007).

Data analysis

An ethnographic content analysis was used, as this provided for a detailed and rich understanding of the realities presented, combining the perceptions of both the ‘insiders’ (i.e. the women) and the ‘outsiders’ (i.e. the researchers) (Geertz 1973; Morse Citation1994). This type of analysis elucidates daily experiences, attributed meanings, and behavior in a specific context (Brohm and Jansen Citation2010).

Recordings of interviews and group sessions were translated from isiXhosa into English and transcribed verbatim. All data were entered into the CAQDAS program Atlas.ti. Data analysis featured a process of constant comparison to discover emergent patterns, themes, and emphases. This resulted in 14 initial salient categories. Data collection and data analysis continued simultaneously to expand on the emerging categories. The analyses, relevance, details, and consequences of each category were discussed in additional group sessions until these concepts and their relations were fully understood. Comparing and categorizing original and additional data and discussion within the research group yielded four main categories, which were identified as being part of one central theme.

Ethics

The Senate Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Western Cape, South Africa, granted ethical approval (No. 15/2/15). Written informed consent was obtained prior to the interviews and group sessions. The right to withdraw or remain silent without explanation was explained, as well as the dual purpose of the project (gaining a contextual understanding of the lives of the people involved and fostering social change). The adoption of pseudonyms guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality (Khanlou and Peter Citation2005). The use of multiple sources for sampling, flexibility in scheduling, the close proximity of research venues, and the possibility of bringing the child reduced barriers to participation (Minkler et al. Citation2002). Prior to the start of the research, a support network of local NGOs and service providers was consulted as researchers were aware of the study’s sensitivity and the likelihood of other social problems surfacing. Indeed, several women needed counseling during the process for issues such as suspected rape of their child, domestic violence, and reduction of the grants they received. The main researcher made sure to contact the relevant service providers and assisted the women in accessing them. The support network has remained in place after finishing the study.

Results

After briefly introducing the group of mothers, we discuss the main theme that emerged from the data: a solitary responsibility of care. This is followed by a presentation of each of the four factors related to this theme: support structures and networks; mothers’ belief systems; personal well-being; and resignation.

The mothers

The group of women participating in this research is diverse. presents the demographic characteristics of participating women and their children.

Table 1. Characteristics of participating female carers and their children.

Both young first-time mothers and older mothers with large families participated. Their children are of different ages and have various disabilities. Half of the children are reported by their mother to have cerebral palsy,Footnote4 although not all children in this group had been officially diagnosed. Most mothers have not been educated beyond secondary school, live without a partner, and rely on the government’s Care Dependency Grant.Footnote5 Indeed, 50% of mothers rely solely on the Care Dependency Grant for their entire familyFootnote6 (see ). The others have some limited additional income from low-paid jobs such as being a domestic worker, informal vendor, parent supporter, crèche assistant, kitchen assistant, or security guard.

For many of the women, this was the first time they had encountered other mothers with a disabled child. This turned out to be one of the major reasons why they wanted to participate:

I am looking forward to the sessions; when one is in the group it feels better. You would think about the things which were said in the group and take that home. (Lulama)Footnote7

I actually met them for the first time today. Yes I do see them, but I never really spoke to them. Talking about it will help, because when you're consulting a doctor they basically just ask you questions and that’s it. But they don't really go deep. So I’m talking about it like this for the first time today. (Buhle)

They were also eager to find out what this research could bring them. Although most women were apprehensive during the introductory sessions, once the creative participatory methods began, the women were eager to share. The majority said that they had never shared their stories before and felt relieved to reveal what was in their hearts:

I am grateful with all the questions she has asked so that I can take it all out. I have had this internal conflict for so long without anyone to talk to. (Nceba)

I am happy to be in a conversation with you all today; as I am talking about these things I am feeling much better. It haunts sometimes not to talk about things. (Nobomi)

A solitary responsibility of care

A major theme that ran through women’s narratives was that they bear the responsibility of care for their child on their own, and in an isolated manner. As they described during a group session:

We choose to live different than others. We create a small world of our own. Just us and our child. We keep quiet, ignore others, and live our lives in our home. (Session 3.14)

We define the solitary responsibility of care as mothers’ perceived obligation to care on their own, including all of the actions they deem necessary for their child’s well-being. This is shaped by and shapes many complex interconnecting factors such as belief systems, community responses, and provision of basic needs. Our data uncover these factors based on mothers’ personal stories; that is, how they view, experience, and exercise their responsibility of care in this specific context of poverty. These factors are described in the following.

Support structures and networks

The key factors that shape the mothers’ responsibility of care are the roles that professional, communal, and family support actors play in their lives.

Professional support

We found that mothers struggle to afford assistance from external services such as (para)medical and respite care. The costs of services (e.g. babysitter or school fees), public transport, or airtime (cell phone credit) to make an appointment were mentioned as financial barriers:

I don’t have money to go to the hospital because in the last few months I got the disability grant but now I didn’t get it [starts crying]. So that’s why I suffer now. (Lumka)

Access to schools and care centres in terms of acceptance of a disabled child is another important issue. Children are regularly refused admission for various reasons. Notumato says: ‘Because he is using a nappy, lots of places refuse to accept him; schools do not accept him. Schools would say he is too old to use a nappy’. According to the mothers, long queues, delays, and waiting lists play an additional role in limiting the accessibility of services.

Furthermore, access to public transport is severely constrained. Mothers can only afford to take local mini-buses, whose drivers refuse to take wheelchairs on board. This significantly restricts their freedom of movement, resulting in suboptimal care, such as being unable to send their child to a care centre or to attend hospital appointments:

The other thing is transport. I struggle to get him transport to the hospital. That stresses me. It’s difficult. I call the hospital and tell them I can’t make it for his appointment because I don’t have transport. (Akhona)

Lastly, mothers perceived services to be limited in their area. Several mothers attributed this to a lack of government interest:

There is not much help from the government; it’s only when the voting time comes when you get to see the councillors in people’s houses. Campaigning; not to give help. I do notice that in other places they [disabled children] are cared for; it’s another story in places where we stay at. (Akhona)

Mothers shared varying accounts regarding the quality of services. On the positive side, most mothers particularly valued the medical attention received at the country’s leading child health institution, one particular day-care centre in Khayelitsha, and from most social workers:

It [placement at care centre] has been very good. Sometimes he would throw tantrums and we wouldn’t understand what he wanted. Now we know when he wants food, because they taught him that. Now he can show you, even if he cannot speak or cannot walk, we have seen another side of him. (Fundiswa)

At the same time, however, almost all mothers had experiences with their child being neglected at care centres, rudely treated at hospitals, or abused at special schools:

At the centre, they never feed her, never change her. The day I came there to visit my baby, she was sleeping on the floor. Sleeping on the floor! My baby got sick there. We had to spend three months in hospital. (Olwethu)

Frequent traumatic experiences like these cause high levels of fear and mistrust, shaping the mothers’ choice of not allowing other people to care for their child.

Communal support

Mothers also expressed a profound fear of abuse, gangsterism, crime, and violence in the community. Although they expressed concern for the safety of all children and for themselves, the generally negative attitudes of the community towards disability, such as verbal and physical abuse and neglect, have led to increased fears for their disabled child, who they feel is an easy target. For example, one boy with a learning disability was used by local gang members as their petty thief while the child believed he was having fun with his friends, unaware of the moral reprehensibility of his actions. Mothers asserted that the violent conditions in Khayelitsha are unfavorable for raising children. Vigilance and mistrust of others have therefore become their way of life.

Family support

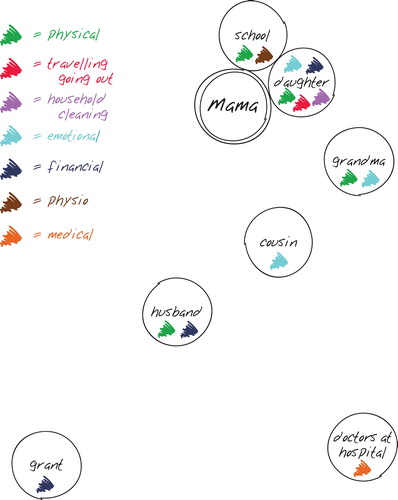

Out of the 30 mothers, only five attested to receiving daily assistance from at least one person in their life: one father, two grandmothers, one brother, and one daughter. They assist with activities such as bathing, feeding, and carrying the child. These five mothers are viewed as lucky and blessed to have such a person in their life. Other mothers, when drawing and discussing their social atom during a group session (see, for example, ), occasionally depicted siblings and extended family members as being emotionally or practically supportive, but indicated that this support is intermittent and thus unreliable.

Figure 1. Example of a social atom drawn by a female carer indicating all actors who provide support (replicated digitally by authors for readability purposes).

Two reasons were given by mothers for not receiving any family support. Firstly, five mothers indicated not trusting other household members with their child. Ndiliswa says: ‘Most of the time he [the father] is at work, he is drinking alcohol, I am not comfortable with him looking after Thanduxolo’. Ten interviewees had dealt with abuse of their child by close relatives. In grandmother Thozoma’s case, alcohol abuse is the prime reason she has to look after her granddaughter in the first place:

There is this child who is making me unsettled. My last born is making my life a pain. She comes back in the house very, very late. She comes back from the shebeen [local bar]. She is making my life a pain. She does beat her own baby and she does not bathe him.

In fact, mothers regarded alcoholism and ignorance about disabilities as key factors that heightened the risk of abuse and neglect:

Sidima is affected because when he [the father] comes back home drunk, he bullies us at home. He bullies us out of the blue with questions he asks like why only Sidima is like that. Why Sidima is a disabled child whereas the other two children are fine? (Nomthandazo)

Secondly, it was revealed that many fathers and other household members do not wish to provide any support to a disabled child, whether practical, financial, or emotional. One mother asserts:

They [mother’s siblings] believe she is good for nothing. There is no point in taking care of her. So they don’t give her food, they don’t sit her up, they don’t change her nappy. (Session 3.12)

Seven mothers mentioned that the fathers left their family because they did not want to be associated with their disabled child. Three fathers were abusive rather than supportive and caring, as they do not accept that their child is disabled. Three other fathers are reported ‘to do nothing’.

Interestingly, the amount of support received does not seem to relate directly to the sense of bearing the sole caring responsibility. Even the five ‘lucky’ mothers feel they shoulder all of the responsibility for providing care. This relates to the fact that one supportive person in daily care is not considered to be enough, which draws attention to the absence of strong supporting structures. What remains, however, is the consideration that mothers believe they are the natural carer of their child and of the whole family:

The difficult one [challenge] that I am facing is the fact that I am a mother for my child but also my brothers are looking unto me for support. My children are looking unto me; my family is looking unto me. (Thandiwe)

Mothers’ belief system

Mothers bearing the care responsibility on their own is inextricably linked to their beliefs and ideas surrounding motherhood, disability, and care. Most women in our study regarded their responsibility towards their child as something natural to motherhood. They believed it was their obligation to nurture, love, and work hard for their child:

We work the hardest, as mothers. We need to work hard. For the whole family. That is our job you see. (Session 3.2)

Interestingly, the three grandmothers and the sister expressed the same natural obligation. In fact, they described themselves as being a mother to and as being addressed accordingly by the child. All women expressed a heightened sense of responsibility for their disabled (grand)child/sibling:

I am happier when I am with my grandson. I love him more than my children. […] All I want to do is to care about his life and taking care of his health. (Lulama)

In addition to perceiving the responsibility of care as natural – ‘it is what mothers do’ – some mothers felt they cannot refuse to care. Some believed God had given them a gift and would never give them a burden they cannot carry, as Olwethu explains:

Jesus gave me the work, I can work for my family, I can do whatever I want to do. […] I am happy for everything I do, for her. I never blame anyone about that, because Jesus knows I must keep that one. That mother, that mother is ok for this baby, she is going to look after her, keep the baby safe, to keep the baby alright.

Alternatively, two mothers did not refer to a natural obligation or to God, but to an involuntary learning process. Indeed, initially they felt pain and resentment towards their child. Having consulted several doctors, they understood their child would not develop or prosper without their care. Over time, they learned to take on the responsibility for their child.

Another influential notion in mothers taking full control of providing care is their perception of being the best carer for their child, saying ‘A mother always, always knows best’ (Session 2.3). This notion is stimulated by an inevitable development of ‘intimate knowledge’ about their child. Mothers’ intimate knowledge refers to knowing the daily needs of their child, for example the type of soft food (s)he needs; knowing the specific habits of their child, for example a child always saying ‘No’ when asked if (s)he needs to go to the toilet; and being able to read their child’s facial expressions and gestures and understand their meanings, for example noticing when a child needs to lie down without being able to say so:

My daughter doesn’t talk, but because I’m her mother I know her, because I know when she's hungry, I know when she’s just bothered. Because I can actually tell. I mean I’m the mother, therefore I know everything about her. (Buhle; original emphasis)

Mothers view themselves as being in a dyadic relationship with their child, as the child also understands and reads the mother’s gestures, and feels and claims her presence. This mutually enforces their bond, and fuels the mothers’ belief of being the best carer.

Personal well-being

Caring for their child on their own has a significant impact on mothers’ psychological and physical well-being, in both positive and negative terms.

Psychological well-being

Being the sole person responsible for caring for their child, mothers frequently emphasized the stress of not being able to fulfill their responsibility to feed, bathe, clothe, educate, and entertain their child and family in a safe, clean environment:

I hope I can be able to take care of her more than this, I take care of her, but I want to do more. I look after her, but they need more love. But when you are constantly stressed you don’t pay too much attention. (Lihle)

If he could just get a school and when he arrives at home he arrives at a warm house, where in the roof there is no sand coming in; that happens when it’s windy. Our house doesn’t have a ceiling. (Thandiwe)

Mothers asserted that providing for these basic needs ‘always comes down to money’, or rather the lack thereof. Finding and maintaining a job requires mothers to leave their child at home, which interferes with their caring responsibilities, particularly since obtaining respite care is fraught with the mothers’ mistrust of babysitters, care centres, and special schools. Mothers who are willing to work and have access to respite care struggle to secure (well-paid) employment; their possibilities are constrained by unemployment, low education and skill levels, limited job opportunities, and nepotism:

It’s difficult [finding a job] because even if you put in CV, the CV will stay there for a long time so in order to get a job you must talk to a person to get it through a person. (Lihle)

Being unable to earn an income and therefore being unable to afford a higher standard of living causes profound distress. Indeed, mothers found this the biggest burden to carry. In fact, when assessing and discussing basic needs such as housing, income, food, and sanitation, mothers repeatedly said ‘Andinyamezeli’, which means ‘I do not endure or tolerate’ in isiXhosa. The word is used to express feelings of stress, worry, sadness, grief, pain, and being overwhelmed. Caring for a disabled child merely puts an additional strain, such as specific nutrition or hygienic requirements, on the mothers’ ability to lead a fulfilling life within their socio-economic context:

I have this child and we are living in the shacks where one is expected to take a long walk to the toilets. These children cannot go to the toilets as I said it is far for them to go. (Session 2.3)

This is not to suggest that stress is related only to low living standards. Mothers also use ‘Andinyamezeli’ in relation to the fact their child has a disability. Although the strong emotions after the diagnosis have usually faded over time, mothers still feel the pain of being unable to see their child develop like other children:

I think this thing on its own is a challenge, it’s a big challenge being disabled. That on its own is a challenge, because I think, oh my word. I mean you see other kids playing and [starts crying] … kids I mean that are her age. (Notumato)

They find it hard to see their child’s discomfort and pain daily. Handling negative responses from extended family and neighbors, such as scolding and shouting, exacerbates the pain. Many women also worry about their child’s development and future prospects, especially about who is going to care for the child after their own death:

Lihle: My fear is when I die or when my mother passes away; when I think about that, it makes me cry.

Thozoma: That is a very painful thought.

Nobomi: I wish my child could die first then I follow.

Ndiliswa: We all do think about that, this is because of the world we live in; it’s a very evil world.

Nomthandazo: You know what, pray to God, plead with Him that before you die, He must take this poor child because there is no one who would take care; even your other children would never take care of your child.

All (at same time): True, that is true. (Session 2.3)

This dialogue hints at the persistent difficulties and worries that afflict mothers of disabled children. However, mothers in Khayelitsha also emphasized that they no longer considered their child a burden. On the contrary, their child was one of their biggest sources of joy and pride. They asserted that being with their child and their family and specifically giving them love brought deep satisfaction and happiness:

I am happy, I can say that. I don’t get hurt that much. I am happy and I love my baby and I want more happiness when it comes to his life. I want to give him love; love such that when he sees me he must see love. When I pick him up, he must feel that a mother’s touch or hands have touched him. (Nomthandazo)

In particular, many mothers reported that seeing their child’s development, however small, brings them great joy:

What made me happy was her being able to sit because other children can’t sit and can’t do everything and I can see she's growing in a good way so that makes me happy. She’s growing and trying out everything, even crawling. (Ndiliswa)

Physical well-being

Managing daily life and care in a difficult context has severe physical ramifications for mothers, who report experiencing fatigue, headaches, and muscular pain caused by the physical care of their child. Although the majority received a state-subsidized wheelchair, most have to lift and carry their child both in and outside the house. Limited space prevents them from using the wheelchair at home, and mothers living in the poorest shack areas cannot use their wheelchair outside because of the sandy roads:

A difficult one is when I have to carry him, going with him here and there, carry him to the bed, carry him to bath, I have to go carry him on weekends for shopping. (Notumato)

I just keep my baby on my back, then I am going to the hospital, then I am coming back, but the next day, my body is feeling sore. If I am doing that, my body is sore, sore, sore. (Olwethu)

Several mothers also reported suffering chronic illnesses such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and depression, which they believed were stress related.

Resignation/acceptance

Despite mothers’ daily struggle and associated stress, a feeling of what we could call either resignation or acceptance is prominent in their accounts. In Khayelitsha, mothers tend to resign themselves to their fate – not just the fact their child is disabled, but also the care responsibility as a mother, their resulting physical issues, their limited ability to provide for basic needs, and their social, economic, and political context. For some mothers, acceptance of their fate is unavoidable. They argue they cannot care for their child or live happily if they are stressing over ‘unchangeable’ situations, and choose to accept anything coming their way:

It is important to accept. It’s like … you put the situation in a box. Then you don’t have to think about it anymore. Life every day is hard, no need to stress. (Session 3.13)

Everything that happens to me I accept it. … There are problems, but then I refuse to complain. Everything you have got to see it in a light way. In everything that I do I trust the Lord. Every day when I am about to sleep and eat, I thank the Lord because other people do not have bread. (Lulama)

As Lulama’s account exemplifies, religion plays an important role in a mother’s acceptance of her fate. Their belief in God as the creator of their life inspires their commitment to accept. In addition, presented with life’s circumstances, some mothers feel powerless and like having no choice but to acquiesce:

So it was like… you HAD to … grow up fast, you had no chance to heal or listen to your body saying: Okay my brother is not the same as the others and he is my only brother. I just had to accept that he is disabled, I have no choice. (Fundiswa)

This feeling of powerlessness is shaped by seeing no options for change in their lives. In fact, when asked what changes they would like to see, mothers were reluctant to name issues. Some became very emotional about it: ‘We just don’t think about it anymore. It is painful. This is what it is’ (Session 3.15). They do not believe that the people around them, the services they deal with, or the government will ever change.

This does not mean, however, that they do not have clear wishes for the future. Mothers overwhelmingly expressed their desire to acquire better housing, secure employment, and find trustworthy day-care centres or special schools. Zimkhitha says: ‘My biggest hope for the future is to see him in a nice environment; be in a decent house’. Finding a job and respite care are inextricably linked since mothers need someone to look after their child while they are out at work, while having more money increases their chances to acquire better housing in the future. As Funeka says: ‘If I can get a job then I can be happy so that the place we are staying at can be a better one’. Almost as importantly, mothers mention that better access to public transport and sufficient emotional and structural support from family, friends, and neighbors would make their lives much easier. Furthermore, they remain hopeful that their child will develop more and prosper in life. In fact, although aware that it is unlikely, most mothers hope their child will lead a life like other children in the future:

I have got faith one day she will be able to stand up. Maybe since she is attending physiotherapy, she will be able to walk. Since she is able to call mom and dad, one day she will be able to speak. I have got faith one day she will be alright. (Nobomi)

Yet, despite having certain hopes, wishes, and aspirations for the future, mothers do not trust anything to change, and would thus rather ‘keep quiet, ignore others and create our own small world’ (Session 3.15).

Discussion

This article has sought to show the daily experiences and perspectives of mothers from a poor resource context with a disabled child. We wanted to learn how they assess and value their life in all its complexity, and how they act within their daily reality. It is necessary to understand their experiences in order to design appropriate disability-inclusive poverty-reduction programmes.

Literature from both resource-poor and other contexts generally describes the external circumstances and relationships that determine the ways in which mothers cope with caring for a disabled child (Gona et al. Citation2011; Hartley et al. Citation2005; Huang, Chen, and Tsai Citation2012; Kishore Citation2011; Plant and Sanders Citation2007). Mothers in Khayelitsha, however, often bear the responsibility of care on their own, engage minimally with others and with services, and become rather isolated in their own small world. A variety of complex factors contribute to and are influenced by the mothers’ solitary endeavors of care. We now critically discuss three of these factors.

First, a profound lack of professional, community, and family support renders women the main individuals responsible for meeting their child’s basic needs. Indeed, the mothers argue that the main cause for ‘andinyamezeli’ (not enduring) is being unable to provide for basic needs and the accompanying sense of failure. This confirms findings in the literature in which mothers highlight the experience of persistent poverty as causing pervasive strain and stress (cf. Goebel, Dodson, and Hill Citation2010; Hunter Citation2010; Sandy, Kgole, and Mavundla Citation2013). Mothers from Khayelitsha consider the low standard of living to be the most demanding, both physically and emotionally. The difficulty of obtaining employment and combining this with care causes substantial financial hardship and limits the mothers’ ability to improve their standard of living.

Second, our findings suggest an important socio-contextual factor under-reported in the literature: although research demonstrates that disabled children in South Africa disproportionately experience violence and abuse, both in the home and outside (Jones et al. Citation2000; UNICEF Citation2013), the effect of such an unsafe context on mothers is under-acknowledged. Mothers in Khayelitsha constantly fear for the safety of their children, especially for a disabled child. Indeed, ‘Khayelitsha ranks among the top areas in South Africa for murder, rape, and aggravated robbery’ (Nleya and Thompson Citation2009, 52). Mothers attribute the risk of abuse to disability discrimination and drug and alcohol abuse, which are exceptionally high in South Africa (ACPF 2011; DSD and CDA Citation2013; Lansdown Citation2002). In a poor urban settlement like Khayelitsha, fear and mistrust have a substantial impact on mothers’ lives, and may similarly apply to mothers living in poverty elsewhere (Webster and Kingston Citation2014).

Lastly, mothers present a sense of resignation towards this complex reality. Although the literature frequently mentions acceptance of the child’s disability as one of parents’ positive coping mechanisms (Barratt and Penn Citation2009; Matt Citation2014, January 2016; Norizan and Shamsuddin Citation2010), acceptance in Khayelitsha encompasses, among other issues, the child’s disability, the poor living conditions, and the context of crime. Mothers resign themselves to their fate. Acceptance and resignation are not just coping mechanisms to come to terms with having a disabled child, as suggested in the literature. Rather, resignation turns out to be a life strategy with comprehensive consequences. ‘Choosing’ to accept and not expecting any change fuel their solitary responsibility of care. At the same time, it fosters a sense of power and being in control. All mothers in our research accept whatever life throws at them, no matter how painful; they create their own small world and aim to maintain a quiet but decent life.

In light of our findings, a crucial question is who is responsible for providing care. Poor women largely remain the prime carers in South African society, and in many other low and middle-income countries. We argue that in order to substantially improve the living conditions and well-being of disabled children and their families, one must focus on systematically supporting these women and thus sharing the responsibility of care.

For disability-inclusive development programmes for disabled children and their families living in poverty to be successful, the active involvement of their carers is essential. Given our findings, which highlight the solitary nature of the care responsibility and related under-acknowledged concepts (i.e. the notion of trust and resignation), however, this may prove challenging. First, as mothers with a disabled child lead rather isolated lives, the first step would be to reach out to them rather than assuming they will seek help. Second, mothers need to be enabled to trust the persons assisting them or working with them. Third, they have to be able to express their ideas for the future and learn to trust in the possibility of change. Without these conditions, mothers are likely to be unwilling to engage with programmes, for example using a care centre, investing time in skills-development programmes, or following medical guidelines.

Peer support groups can provide a first step for active involvement of mothers. Mothers in our project who continued attending attributed their participation to the support they found with each other. Sharing the positive and negative experiences, assisting each other with practical issues, and giving and receiving advice can ease the solitary care responsibility.

Secondly, NGOs and governmental institutions can play a crucial role in establishing a safe and nourishing environment for mothers to engage in and actively pursue their aspirations on the level of family, community, and professional services. These institutions, however, should be critically aware of the implications of mothers bearing the care responsibility on their own. In practical terms, this means besides fostering gender equality within the home, also nurturing the caring skills of family members; in addition to providing access to services, also ensuring their high quality; and apart from promoting family and community solidarity for social network support, also raising disability awareness among (para)medical professionals.

Lastly, such measures can reach their full potential in a wider context of poverty-reduction and macroeconomic policies fostering job opportunities and education, and lowering crime levels. Thus, a focus on sharing the responsibility of care between peers, family, civil society, and the state could break the solitary nature of the care responsibility and lead to better life outcomes for mothers and their children.

Limitations

This study has several strengths, such as the in-depth quality and richness of the data. However, due to the small size of the group, the specificity of context, and the choice of methodology, the research outcomes are qualitative, narrative, and relational. Despite including mothers who make use of a care centre and mothers who do not, we cannot determine whether the results would have been different with mothers who chose not to attend after having been invited to participate. The results should therefore not be interpreted as representing all South African women caring for a disabled child. Yet, considering the extended period of time spent with the mothers, we believe the chosen methodology was best suited to gain an understanding of the complexity of their daily realities. More extensive research on mothers of disabled children living in resource-poor contexts would shed light on commonalities and differences in experiences.

In addition, the study particularly gained insight into the experiences of female carers as women tend to be the primary carers in South Africa. Fathers’ experiences might, however, be very different as they encounter other cultural and political norms and practices. In future research, sufficient resources should be given to peer invitations, increasing participation (providing participating mothers with airtime or transport money to explain the project to other mothers), and towards including male carers, to diversify the findings.

Lastly, the dual nature of participatory action research, which involves both gaining a contextual understanding of the lives of the people and fostering social change, can be seen as both an advantage and a limitation. Continued reflection on the main researcher’s double role and strict research conducts contributed to limiting the potential conflict.

Conclusion

The narrated, lived experiences of mothers from this poor urban settlement of Khayelitsha in Cape Town, South Africa emphasize the solitary bearing of care responsibility, the gendered burden of care, and the influence of abuse, violence, poverty, and discrimination. The related inability to provide for basic needs, notions of mistrust and fear, and resignation affect mothers’ abilities to attain general well-being for themselves and their family. This renders many women invisible. They slip through the cracks of the system and find themselves caring for their disabled child on the outskirts of society on their own.

We argue that for disability-inclusive development to be successful, programmes should support mothers by sharing the responsibility of care, taking into account the notions of trust, resignation, and the impacts of poverty. We hope that this could provide room for these mothers to enhance the well-being of themselves and their children.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded with support of the European Commission. This publication reflects the view only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 At the time of this research, R20,000 (South African Rand) was approximately £990 and $1275.

2 See www.sibongile.org

3 For readability purposes, the term mothers will be used throughout the article to indicate ALL carers, unless stated otherwise.

4 Cerebral palsy is one of the most common types of disability present in South Africa. Mothers believed their child had cerebral palsy when he/she had both physical and psychological impairments.

5 This is a grant from the South African government awarded to all primary carers of a child with a ‘permanent, severe’ disability living at home (SASSA Citation2016). At the time of research, this grant was set at R1410 (South Africa Rand) per month (approximately £70 and $90).

6 In 2016, this grant was set at R1410 (South Africa Rand) per month (approximate;y £70 and $90). With a poverty line set at R779 (approximate;y £38 and $50) per person per month (based on 2011 prices), it is clear the vast majority of these mothers and their families live below it (Stats SA 2015).

7 All quotes are drawn from either a comment from one of the mothers during a group session indexed by a number corresponding with our data storage or from a one-on-one interview with a mother from the core group indexed by their isiXhosa first name pseudonym.

References

- ACPF. 2011. Children with Disabilities in South Africa: The Hidden Reality. Addis Abeba: The African Child Policy Forum.

- Alkire, Sabina. 2011. Multidimensional Poverty and its Discontents. Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Azeem, Muhammad Waqar, Imtiaz Ahmad Dogar, Snehal Shah, Mohsin Ali Cheema, Alia Asmat, Madeeha Akbar, Sumira Kousar, and Imran Ijaz Haider. 2013. “Anxiety and Depression among Parents of Children with Intellectual Disability in Pakistan.” J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 22 (4): 290–295.

- Bannink, Femke, Geert Van Hove, and Richard Idro. 2016. “Parental Stress and Support of Parents of Children with Spina Bifida in Uganda.” African Journal of Disability 5 (1): 1–10.

- Barratt, Joanne and Claire Penn. 2009. “Listening to the Voices of Disability: Experiences of Caring for Children with Cerebral Palsy in a Rural South African Setting.” In Disability & International Development: Towards Inclusive Global Health., edited by M. MacLachlan and L. Swartz, 191–212. New York: Springer.

- Beresford, Peter. 2016. “Presenting Welfare Reform: Poverty Porn, Telling Sad Stories Or Achieving Change?” Disability & Society 31 (3): 421–425.

- Brohm, R. and W. Jansen. 2010. Kwalitatief Onderzoeken. Praktische Kennis Voor De Onderzoekende Professional. Delft: Uitgeverij Eburon.

- Brunn, Stanley D. and Matthew W. Wilson. 2012. “Cape Town's Million Plus Black Township of Khayelitsha: Terrae Incognitae and the Geographies and Cartographies of Silence.” Habitat International 39: 284–294.

- Chambers, Robert. 2010. “Paradigms, Poverty and Adaptive Pluralism.” IDS Working Papers 2010 (344): 1–57.

- Chang, Mei-Ying and Roy McConkey. 2008. “The Perceptions and Experiences of Taiwanese Parents Who have Children with an Intellectual Disability.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 55 (1): 27–41.

- Chiang, Linda H. and Azar Hadadian. 2007. “Chinese and Chinese-American Families of Children with Disabilities.” International Journal of Special Education 22 (2): 19–23.

- Cluver, Lucie and Mark Orkin. 2009. “Cumulative Risk and AIDS-Orphanhood: Interactions of Stigma, Bullying and Poverty on Child Mental Health in South Africa.” Soc Sci Med 69 (8): 1186–1193.

- DSD and CDA. 2013. National Drug Master Plan 2013 – 2017. Pretoria: Department of Social Development, Republic of South Africa/Central Drug Authority.

- DSD, DWCPD, and UNICEF. 2012. Children with Disabilities in South Africa: A Situation Analysis: 2001-2011. Pretoria: Department of Social Development/Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities, Republic of South Africa/UNICEF.

- Geertz, C. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. . New York: Basic Books.

- Goebel, Allison, Belinda Dodson, and Trevor Hill. 2010. “Urban Advantage Or Urban Penalty? A Case Study of Female-Headed Households in a South African City.” Health & Place 16 (3): 573–580.

- Gona, J. K., V. Mung'ala‐Odera, C. R. Newton, and S. Hartley. 2011. “Caring for Children with Disabilities in Kilifi, Kenya: What is the Carer's Experience?” Child: Care, Health and Development 37 (2): 175–183.

- Gona, JK, CR Newton, KK Rimba, R. Mapenzi, M. Kihara, FV Vijver, and A. Abubakar. 2016. “Challenges and Coping Strategies of Parents of Children with Autism on the Kenyan Coast.” Rural and Remote Health 16: 3517.

- Gordon, Steven, B. Roberts, and J. Struwig. 2013. “Shouldering the Burden: Gender Attitudes Towards Balancing Work and Family.” South African Social Attitudes Survey, HSRC Review: November 2016. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/review/hsrc-review-september-2013/shouldering-the-burden-gender-attitudes-towards-balancing-work-and-family.

- Grech, Shaun. 2009. “Disability, Poverty and Development: Critical Reflections on the Majority World Debate.” Disability & Society 24 (6): 771–784.

- Green, Sara Eleanor. 2007. “We're tired, not sad: benefits and burdens of mothering a child with a disability ”: Soc Sci Med 64 (1): 150–163.

- Groce, Nora, Maria Kett, Raymond Lang, and Jean-Francois Trani. 2011. “Disability and Poverty: The Need for a More Nuanced Understanding of Implications for Development Policy and Practice.” Third World Quarterly 32 (8): 1493–1513.

- Hartley, S. O. V. P., P. Ojwang, A. Baguwemu, M. Ddamulira, and A. Chavuta. 2005. “How do Carers of Disabled Children Cope? The Ugandan Perspective.” Child: Care, Health and Development 31 (2): 167–180.

- Heiman, Tali. 2002. “Parents of Children with Disabilities: Resilience, Coping, and Future Expectations.” Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 14 (2): 159–171.

- Huang, Yu‐Ping, Shu‐Ling Chen, and Sen‐Wei Tsai. 2012. Father's experiences of involvement in the daily care of their child with developmental disability in a Chinese context Journal of Clinical Nursing 21 (21-22): 3287–3296.

- Hunter, N. 2010. Measuring and Valuing Unpaid Care Work: Assessing the Gendered Implications of South Africa's Home-Based Care Policy University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban.

- Jones, SL, M. Weinberg, RI Ehrlich, and K. Roberts. 2000. “Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Parents of Asthmatic Children in Cape Town.” J Asthma 37 (6): 519–528.

- Kayfitz, A. D., M. N. Gragg, and R. Orr. 2010. “Positive Experiences of Mothers and Fathers of Children with Autism.” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 23 (4): 337–343.

- Khanlou, Nazilla and Elizabeth Peter. 2005. “Participatory Action Research: Considerations for Ethical Review.” Social Science & Medicine 60 (10): 2333–2340.

- Kimura, M. and Y. Yamazaki. 2013. “The Lived Experience of Mothers of Multiple Children with Intellectual Disabilities.” Qualitative Health Research 23 (10): 1307–1319.

- Kishore, M. T. 2011. “Disability Impact and Coping in Mothers of Children with Intellectual Disabilities and Multiple Disabilities.” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities: JOID 15 (4): 241–251.

- Lansdown, G. 2002. Disabled Children in South Africa: Progress in Implementing the Convention on the Rights of the Child. London, United Kingdom: DAA.

- Mathye, Desmond and Carina A. Eksteen. 2016. “Causes of Childhood Disabilities in a Rural South African Community: Caregivers' Perspective.” African Journal for Physical Activity and Health Sciences (AJPHES) 22 (2.2): 590–604.

- Matt, Susan B. 2014. “Perceptions of Disability among Parents of Children with Disabilities in Nicaragua: Implications for Future Opportunities and Health Care Access.” Disability Studies Quarterly 34 (4): January 2016. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v34i4.3863.

- McConkey, Roy, Maria Truesdale-Kennedy, Mei-Ying Chang, Samiha Jarrah, and Raghda Shukri. 2008. “The Impact on Mothers of Bringing Up a Child with Intellectual Disabilities: A Cross-Cultural Study.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 45 (1): 65–74.

- McConnell, David, Amber Savage, Dick Sobsey, and Bruce Uditsky. 2015. “Benefit-Finding or Finding Benefits? The Positive Impact of having a Disabled Child.” Disability & Society 30 (1): 29–45.

- Minkler, Meredith, Pamela Fadem, Martha Perry, Klaus Blum, Leroy Moore, and Judith Rogers. 2002. “Ethical Dilemmas in Participatory Action Research: A Case Study from the Disability Community.” Health Educ Behav 29 (1): 14–29.

- Mitra, Sophie, Aleksandra Posarac, and Brandon Vick. 2013. “Disability and Poverty in Developing Countries: A Multidimensional Study.” World Development 41: 1–18.

- Morse, J. M. 1994. “Emerging from the Data: The Cognitive Processes of Analysis in Qualitative Inquiry. .” Critical Issues in Qualitative Research Methods 346: 350–351.

- Neely-Barnes, Susan L. and David A. Dia. 2008. “Families of Children with Disabilities: A Review of Literature and Recommendations for Interventions.” Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention 5 (3): 93–107.

- Nleya, Ndodana and Lisa Thompson. 2009. “Survey Methodology in Violence-Prone Khayelitsha, Cape Town, South Africa.” IDS Bulletin 40 (3): 50–57.

- Norizan, A. and K. Shamsuddin. 2010. “Predictors of Parenting Stress among Malaysian Mothers of Children with Down Syndrome.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 54 (11): 992–1003.

- Oelofsen, Natius and Phil Richardson. 2006. “Sense of Coherence and Parenting Stress in Mothers and Fathers of Preschool Children with Developmental Disability.” J Intellect Dev Disabil 31 (1): 1–12.

- Palmer, Michael. 2011. “Disability and Poverty: A Conceptual Review.” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 21 (4): 210–218.

- Park, H. J. and G. H. Chung. 2015. “A Multifaceted Model of Changes and Adaptation among Korean Mothers of Children with Disabilities.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 24 (4): 915–929.

- Philpott, S. 2006. “Vulnerability of Children with Disability: The Impact of Current Policy and Legislation.” In South African Health Review 2006, edited by P. Ijumba and A. Padarath, 271–282. Durban: Health Systems Trust.

- Philpott, S. and P. McLaren. 2011. Hearing the Voices of Children and Caregivers: Children with Disabilities in South Africa; A Situation Analysis, 2001-2011. Pretoria: Department of Social Development, Republic of South Africa/UNICEF.

- Plant, Karen M. and Matthew R. Sanders. 2007. “Predictors of Care‐giver Stress in Families of Preschool‐aged Children with Developmental Disabilities.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 51 (2): 109–124.

- Raina, Parminder, Maureen O'Donnell, Peter Rosenbaum, Jamie Brehaut, Stephen D. Walter, Dianne Russell, Marilyn Swinton, Bin Zhu, and Ellen Wood. 2005. “The Health and Well-being of Caregivers of Children with Cerebral Palsy.” Pediatrics 115 (6): 626–636.

- Resch, J. A., Gerardo Mireles, Michael R. Benz, Cheryl Grenwelge, Rick Peterson, and Dalun Zhang. 2010. “Giving Parents a Voice: A Qualitative Study of the Challenges Experienced by Parents of Children with Disabilities.” Rehabilitation Psychology 55 (2): 139–150.

- Ryan, Sara and Katherine Runswick-Cole. 2008. “Repositioning Mothers: Mothers, Disabled Children and Disability Studies.” Disability & Society 23 (3): 199–210.

- Saloojee, G., M. Phohole, H. Saloojee, and C. IJsselmuiden. 2007. “Unmet Health, Welfare and Educational Needs of Disabled Children in an Impoverished South African Peri-Urban Township.” Child: Care, Health and Development 33 (3): 230–235.

- Sandy, PT, JC Kgole, and TR Mavundla. 2013. “Support Needs of Caregivers: Case Studies in South Africa.” International Nursing Review 60 (3): 344–350.

- SASSA. “South African Social Security Agency: Care Dependency Grant.”, accessed December 10, 2016, http://www.sassa.gov.za/index.php/social-grants/care-dependency-grant.

- Seekings, J. 2013. Economy, Society and Municipal Services in Khayelitsha. Cape Town: Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape Town.

- Seekings, J. and N. Nattrass. 2014. Policy, Politics and Poverty in South Africa. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stats SA. 2015. Methodological Report on Rebasing of National Poverty Lines and Development of Pilot Provincial Poverty Lines. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

- Stringer, Ernest T. 2007. Action Research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Taanila, Anja, Leena Syrjälä, Jorma Kokkonen, and M‐R Järvelin. 2002. “Coping of Parents with Physically and/Or Intellectually Disabled Children.” Child: Care, Health and Development 28 (1): 73–86.

- Terreblanche, Sampie. 2002. A History of Inequality in South Africa, 1652-2002. Scottsville: University of Kwazulu Natal Press.

- UNICEF. 2013. The State of the World's Children 2013. Children with Disabilities. New York: United Nations Children's Fund.

- van der Mark, E. J. and H. Verrest. 2014. “Fighting the Odds: Strategies of Female Caregivers of Disabled Children in Zimbabwe.” Disability & Society 29 (9): 1412–1427.

- van der Mark, E. J., I. Conradie, C. W. M. Dedding, and J. E. W. Broerse. 2017. “How Poverty Shapes Caring for a Disabled Child: A Narrative Literature Review.” Journal of International Development 29(8): 1187–1206. doi: 10.1002/jid.3308.

- Wang, Peishi, Craig A. Michaels, and Matthew S. Day. 2011. “Stresses and Coping Strategies of Chinese Families with Children with Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 41 (6): 783–795.

- Webster, Colin and Sarah Kingston. 2014. Anti-Poverty Strategies for the UK: Poverty and Crime Review. Centre for Applied Social Research (CeASR), Leeds Metropolitan University, Leeds: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Wijesinghe, Champa J., Natasha Cunningham, Pushpa Fonseka, Chandanie G. Hewage, and Truls Østbye. 2015. “Factors Associated with Caregiver Burden among Caregivers of Children with Cerebral Palsy in Sri Lanka.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health 27 (1): 85–95.

- Yagmurlu, Bilge, H. Melis Yavuz, and Hilal Sen. 2015. “Well-being of Mothers of Children with Orthopedic Disabilities in a Disadvantaged Context: Findings from Turkey.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 24 (4): 948–956.

- Ylvén, Regina, E. Björck-Åkesson, and Mats Granlund. 2006. “Literature Review of Positive Functioning in Families with Children with a Disability.” Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 3 (4): 253–270.