Abstract

Switzerland’s social policies in the field of disability have been significantly reshaped over the last two decades by reducing the number of allowances awarded and by increasing the recourse to vocational rehabilitation measures. What stances do individuals who experience the implementation of these policies adopt? What kind of tests are they subjected to? How can we explain the posture they adopt – be it ‘compliant’, ‘pacified’ or ‘rebellious’ – when facing the (re)assignations of their identity and professional status? Drawing on interviews conducted with individuals who have recently been involved in programmes set up by Swiss disability insurance, we highlight their uncertainties and concerns relating to their place in society, as well as their reactions to disability insurance’s interventions.

Points of interest

This article examines how people experience vocational rehabilitation programmes set up by Swiss disability insurance.

Swiss disability insurance evaluates one’s eligibility for vocational rehabilitation and benefits; it proposes or denies vocational retraining courses and can cease to provide benefits if recipients turn down its offers.

This process provokes doubts, fears and hopes, and often involves the mourning of previous identities.

While some people are happy with Swiss disability insurance’s decisions, others have more mixed views and a majority of those we met are very critical.

The main factors that impact the experiences of people in contact with disability insurance are, on the one hand, the opportunity to negotiate one’s rehabilitation path and future occupation, and, on the other, the outcome of this negotiation.

Introduction

The test is always a test of strength. That is to say, it is an event during which beings, in pitting themselves against one another … reveal what they are capable of and, more profoundly, what they are made of. (Boltanski and Chiapello Citation2005, 31)

In Switzerland, health impairments that partially or wholly affect a person’s earning capacity are covered by a specific category of social insurance: disability insurance (DI). DI is compulsory and universal, applying to Switzerland’s whole resident population. Its financing is based upon obligatory contributions (52.8%) as well as tax revenue (47.2%) (OFAS Citation2017). Since its implementation in 1959, DI has provided two main types of benefits – rehabilitation measures aimed at partially or wholly restoring recipients’ earning capacity, and disability pensions for individuals considered unable to attain this earning capacity. The rate of pensions is based on a disability scale: depending on the degree of their earning incapacity, recipients are eligible for a quarter, half, three-quarter or full pension.

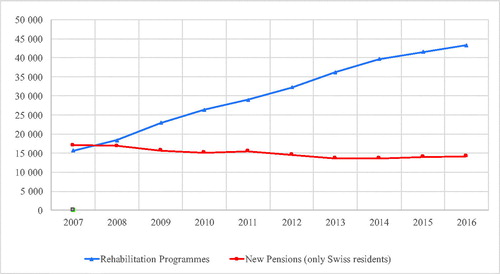

Since the early 2000s, DI has been revised three times. The main goal of legislative changes was to reduce the number of pensions awarded by restricting the definition of disability, on the one hand, and increasing recourse to rehabilitation measures on the other. These changes have expanded the range of measures offered – introducing, among others, early intervention measures, integration measures and trial job placements. They have thus transformed both the target population and the nature of rehabilitation. As a result, the number of individuals involved in rehabilitation programmes has increased, as shows.

Figure 1. Number of persons involved in rehabilitation programmes and new pensions awarded. Note: Data retrieved from @Federal Social Insurance Service (2017) and DI Statistic 2016.

Within this context of rapid changes in disability policies, largely focused on the increased value placed on (re)involvement in the labour market, how do target groups experience their interactions with DI? Prior to exploring this issue, we briefly present the state of current research on the experience of vocational rehabilitation. In this section we also set forth our theoretical standpoint. Next, we discuss our empirical material and present the typology of reactions to the disability certification process that we have constructed.

Theoretical context

Four types of conceptual issues arise from current research on how vocational rehabilitation is experienced in Western Europe, the United States and Australia; that is, national contexts where activation technologies are part of the disability policy (OECD Citation2009).

One group of studies examines the impact on recipients of the normative framework of new social policies in the field of disability. Norms of self-sufficiency, independence, employability and productivity in the labour market, in short the norms of abledness, are now embedded in policy measures (Chouinard and Crooks Citation2005; Lantz and Marston Citation2012; van Hal et al. Citation2012; Vandekinderen et al. Citation2012). Hence, acquiring qualifications is no longer the only goal of said measures. In practice, this means that pressure is put on recipients to conform to these norms. As a result, their experience of vocational rehabilitation becomes dependent on their capacity to embody the logics of the able-bodied worker.

Another range of studies focuses more specifically on agents charged with implementing these social policies. They show that these professionals play an important role in identity negotiations within the social protection apparatus, since they are the ones that assign (dis)ability statuses (Angeloff Citation2011). In doing so, they reconstruct and come to consolidate a scale of (dis)ability, as well as that of (in)ability to work (Bertrand, Caradec, and Eideliman Citation2014). In practice, this (re)assignation involves ruptures from previous identities as well as taking on new statuses, along with the problems these processes may pose in some cases. People to whom a status of 'disabled' is attributed, for example, were not necessarily seeking this ‘recognition’, in Nancy Fraser’s (Citation2005) terms. In some cases, the goal was to gain protection from an employer or from the requirements of other social services programmes. In others, the goal was that of accessing professional retraining opportunities. Research also shows that lack of communication and transparency about policy reforms and the gap between political discourse and its implementation can have negative effects on recipients (Knijn and van Wel Citation2014; Parker Harris et al. Citation2014; Vedeler Citation2009).

A third type of studies highlights the various instruments mobilised to bring recipients into conformity with the new normative framework. They may include motivational strategies (Lantz and Marston Citation2012) or focus on ensuring that recipients subscribe to the new norms and internalise a specific posture that entails, for example, knowing one’s place, accepting it and appropriating it (Piecek et al. Citation2017). These ‘techniques of the self’ (Foucault Citation2001) are underpinned by required self-assessment exercises that result in recipients internalising the status of ‘disabled subject’ (Shildrick and Price Citation1996). New techniques of governance also include feelings like disgust or shame (Soldatic and Meekosha Citation2012). In short, these new disability policy instruments are based on subjectivisation practices (Bröckling Citation2016) typical of current social policies.

A fourth type of research brings to light the diversity of recipients’ lived experiences. As people navigate through the obstacle-laden process that disability policy puts them through (Revillard Citation2017), their perception and reception of this policy can take various forms depending on their disability model of reference (Dorfman Citation2017), gender, age, type of health impairment, socio-professional status and type of employment (Angeloff Citation2011). The experience of work rehabilitation is also interwoven with a range of relationships that individuals cultivate with themselves, with society, and with their past, current and future lives, that give rise to different 'narratives of identity work' (van Hal et al. Citation2012).

Overall, these studies primarily bring to light the negative impact of social policies on recipients. They pinpoint the anxiety, stress, stigmatisation and painfulness of attempts to conform, as well as the feelings of illegitimacy and marginalisation that characterise the experiences of individuals confronted with institutional arrangements concerning disability (de Wolfe Citation2012; Morris Citation2013). Barriers encountered in accessing public health and welfare services may also lead to a deterioration of claimants’ health status (Fougeyrollas et al. Citation2008; Grut and Kvam Citation2013). Nonetheless, a few studies point out that recipients’ experiences may be mixed, oscillating between positive feelings on the one hand and expression of the need for more individualised services on the other (Kinn et al. Citation2011), and that some participants experience work rehabilitation programmes in very positive ways (Heenan Citation2002; Lewis, Dobbs, and Biddle Citation2013). We should also note that factors favouring decisions to enter rehabilitation programmes, as well as factors that may improve return to work, have been the focus of various analyses that may be best described as expert evaluations (for example, Hamner, Timmons, and Bose Citation2002; Johnson et al. Citation2009; Wagner, Wessel, and Harder Citation2011).

A recent but growing body of literature seeks to emphasise the voices of recipients or potential recipients themselves. This article attempts to offer new insights into this research field by focusing on an issue that in our view has been insufficiently examined: the positions adopted by users with regard to the new normative framework underpinning social policies focused on disability. More specifically, the article concerns how they position themselves with regard to the disability certification process. To this end, we will examine how norms are experienced and how critical discourse emerges around these experiences. We shall do so on the basis of the experiences of individuals involved in vocational rehabilitation programmes run by DI in Switzerland.

On the theoretical level, our approach involves articulating the legacy of pragmatic sociology (Boltanski Citation2009) with the contribution of critical disability studies. According to the former perspective, social actors act on the basis of values and norms of justice to which they adhere. We make the assumption that contact with DI can be a ‘test’ (Claisse and Jacquemain Citation2008; Martuccelli Citation2015), as actors experience it at a time of uncertainty and worry about the future. Therefore, in our hypothesis, these individuals perceive, interpret and/or critique the boundaries set between so-called able-bodied/minded and so-called disabled people, as well as the DI (dis)ability scale, with regard to their conceptions of what is fair and legitimate. The critical disability studies perspective (Campbell Citation2009; Goodley Citation2014) that we adopt will help us analyse how this critique questions the normative presuppositions that are at the origin of the social construction of (dis)ability as well as that of normality. We shall thus be able to identify whether and how actors question the ableist logics that, through a process of differentiation and of hierarchical divisions, assign individuals to an inferior status of ‘other’ when their capacities do not conform to established standards.

Methodology

This article is based on a study supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) and by the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland (HES-SO)1. The University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland’s research team is comprised of sociologists and a psychologist (three women and one man).

In order to mitigate potentially ableist biases of our research, two steps were taken. Firstly, one of the sociologists hired as research team member herself experiences disability and receives a partial disability pension. Secondly, a support group of nine individuals involved in non-profit organisations that focus on disability issues, most of them with direct experience of disability, met five times to discuss methodological approaches and research hypotheses. Other than the opportunity to increase the quality of both the data collected and the analyses (Bergold and Thomas Citation2012), this approach constitutes an attempt to involve individuals in studies that concern them.

Our project aimed at collecting a wide range of rehabilitation experiences in order to meet the principles set out for the selection of qualitative multiple case samples (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967; Pires Citation1997). This approach is based on the diversification of cases (in the context of our research this refers to rehabilitation measures, gender, domestic workload, education level, disability, age, etc.), regardless of their statistical frequency. In order to recruit participants, we contacted 98 specialised organisations and asked them, respecting all standard ethical criteria, to relay requests for interviews. Despite the number of contacts initiated, we encountered some difficulties in recruiting participants. Among reasons reported for refusals were particularly difficult personal situations, as well as fear that information could end up in the hands of DI agents.

Thirty-three semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted between February 2016 and January 2017, lasting from 50 minutes to 2.5 hours, brought us to a saturation point (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967). Interviewees’ were aged between 20 and 64 years. They experienced a broad range of impairments, such as hearing impairments, chronic pain, depression, cancer and burnout. Seventeen of them were directed towards vocational rehabilitation on the basis of a medical diagnosis of physical impairment, 14 due to diagnoses related to mental health and two interviewees had a diagnosis of learning disability. These individuals were at various stages of their journey through DI at the time of the interview: some were involved in rehabilitation measures and others were not; some had returned to employment, others had not. The duration of their involvement with DI ranged from a few months to over 20 years. Types and providers of measures in which interviewees had been involved also varied widely. Our interviewees’ socio-demographic data are presented in .

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants (at time of interview).

Our interview protocol was designed to focus on the evaluation of DI interventions, in order to avoid reproducing the structure of DI questionnaires concerning health impairments and professional experience. We talked about our interviewees’ experiences relating to DI administration, rehabilitation measures and the consequences for them of DI action. We encouraged them to express some distance from their dealings with DI agents. This led them to speak of their agreements and disagreements with DI interventions, as well as with the (dis)ability scale it uses.

All interviews have been recorded, transcribed and anonymised. The data were analysed adopting an inductive analytic approach (see Charmaz Citation2006; Corbin and Strauss Citation1990; Glaser and Strauss Citation1967). In order to gain an understanding of interviews’ content in their multiple dimensions, we conducted thematic iterative coding (MacQueen et al. Citation1998; Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña Citation1994). A final coding process included a set of six themes (evaluation of DI responses, personal experience of DI institution, personal experience of rehabilitation, feelings about DI, feelings about society, self-image during and after their experience) and 20 codes. Based on that coding, we constructed three ideal-types of experiences. While ideal-types are useful for understanding the meaning that individuals accord to their experiences (Aronovitch Citation2012; Weber [1904] Citation2013), their purpose is not to provide statistical representativeness. Furthermore, our typology refers to different reactions to the disability certification process and should not be viewed as a typology of personalities.

Interviews were also coded for 18 socio-demographic variables, such as professional status before contact with DI, age, level of education, domiciliary care services, family situation, domestic work and care work or type of impairment. The only variables that showed a direct association with specific lived experiences and attitudes were presence in the job market and sex, which will be discussed later.

Summaries and interview excerpts were chosen for their representative character of the dimensions that make up the ideal-types presented in the article.

Limitations

Two limitations stem from our methodological choices. Our standpoint, particularly in terms of our outsider status with regard to the lived experience of interviewees as well as to the asymmetry inherent to the interview situation, lead to the production of empirical data that do not include some dimensions, more intimate and emotional, of participants’ experience of contacts with DI. The second limitation comes from the fact that our data, like all biographical narratives, are comprised of reconstructions after the event.

Two further limitations came to light over the course of the study. Our sample contains no subjects who are just beginning their journey through DI. Interviewees pointed out that at this stage they would have been unable to participate in an interview due to health problems or because of difficulties they were experiencing in their dealings with DI. As a result, we only met with people who were willing and ready to talk about their experience. The final limitation comes from having had to go through a provider of rehabilitation programmes (for six interviewees) in order to complete our sample and achieve saturation; this may also have introduced a bias.

Analysis

In the context of dealing with DI, the status of recipients with regard to norms of (dis)abledness is discussed. This status can be questioned, modified or even profoundly redefined.

The perception individuals have of their own status is placed in direct confrontation with the institution’s vision of their status, often time and time again as rehabilitation programmes and vocational retraining are proposed, or denied, by DI agents. For example, Florent (60 years old, bank employee and awaiting DI decision)2 explains that the disability rate he has been assigned (30%) is too low: ‘I really didn’t think the doctor [medical advisor to DI] would manage to find me 70% able, I almost fell off my chair I was so, so shocked.’ Martine (47 years old, nurse), on the contrary, finds it too high: ‘I didn’t understand … I said to myself: “But what is the matter with them? They actually think my case is so serious that I’ll never work again?”’ Jérôme (46 years old, in training as a salesperson) expresses his disappointment because his career plans need to be redefined: ‘I wanted to go back to sales, but they [DI agents] were telling me I couldn’t, so I was a bit disappointed because that was the kind of job I wanted.’

Power is not equally distributed in these confrontations, since DI can cease to provide financial support if beneficiaries turn down its offers. Here we may really speak of ‘an offer you can’t refuse’ without running the risk of negative consequences. Helmut (25 years old, awaiting DI decision) states this clearly when he explains that DI agents ‘put pressure on him’ and that he agreed to enter a training programme he had not chosen, telling himself: ‘Enough already! I’ll accept the damn thing and that way it’s done and dusted.’ Laurent (45 years old, in training as a salesperson) expresses a similar position when he says that:

if you close the doors … if you turn things down … after a while [the DI agent will say]: ‘Well now if you aren’t willing to try, take a step or two in the right direction, then we’ll just stop right here!’

Sarah (20 years old, awaiting DI decision) also expresses the feeling of not having any choice: ‘Either I accept penalties, or I accept whatever they’re offering.’

On the basis of our interviews, we can identify three ideal-typical discourses about DI experience. The first is characterised by an agreement with the status classification made by DI. The second is characterised by a temporary conflictual reaction, having later given way to a pacified attitude. The third is characterised by rebellion.

The ‘compliant’

This first ideal-type is comprised of individuals who, on the whole, agree with what DI has provided for them, and who have a positive view of the outcome of this experience. This group is small, including only 4 of the 33 interviewees. As they are four men aged 31–46 years, this may confirm the gendered character of measures set up by DI (Vandekinderen et al. Citation2012). Before coming into contact with DI, three had completed their upper secondary education (either vocational education and training or academic high school), and one had completed compulsory school. Two were receiving financial benefits (from DI and from welfare) due to diagnoses related to mental health, and the other two had been obliged to leave their jobs because of physical impairments. All had taken part in various rehabilitation measures and had followed a certifying upper secondary-level training programme financed by DI. At the time of interview, only one of them was still involved in a vocational programme and about to complete a technical training course. Three others held jobs and were satisfied with their rate of occupation3 (between 25% and 100%; the person working a very part-time job also receiving a pension from DI). presents socio-demographic characteristics of participants per ideal-type.

Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants per ideal-type (at time of interview).

As an example of this ideal-type, we may cite the case of Antonio, 36 years old at the time of interview. Antonio worked as a salaried electrician until he suffered a work accident at age 30 years. He then had to reduce his working hours to eight per week. Two years later, after being fired by his employer and losing his accident insurance cover, his doctors submitted a request to DI for vocational retraining, considering that Antonio would have full work capacity if he could switch to a suitable vocation. A year later, DI confirmed his right to access to vocational rehabilitation measures. His experience is as follows.

The first programme offered to Antonio is a competency evaluation – a two-day session he views rather critically, feeling that ‘it did not really amount to much’. Then he follows, over a three-month period, a programme in an institution mandated by DI. The goal is to find a full-time activity compatible with his health status. Initially, he is rather apprehensive: ‘My first feeling … was: “I’m arriving in an unknown universe, what are they going to do to me? How is it going to go?”’ Relatively quickly, he gains trust in the programme and becomes acquainted with other participants. He finds the support offered comprehensive and personalised, and the daily schedules varied. He takes part in a range of evaluation modules in order to test his functional limitations, on the one hand, and define new career avenues on the other. ‘It went from photography to IT [information technology], from lithography to care work, so I was really able to explore all the fields that interested me’, he sums up. He also takes initiatives: ‘I was really motivated, so I pushed for field practice to start sooner than I would usually.’ Finally, he is placed in various internships, first as an IT worker and later in residential care institutions and a nursing home. He puts together an educational project for a three-year training course as a social care worker and successfully pitches for it in a meeting with DI agents. Retrospectively, he thinks that ‘things have been set up so that I can make it’ and that he has been ‘very fortunate’ to have had a very open-minded DI agent.

His experience of the rehabilitation process, however, has not all been smooth sailing. The training course is demanding and the work required is substantial. This affected his private life and led to a separation. Towards the end of his course, Antonio’s health took a turn for the worse. Financially, his income decreased during his course, and as a result he had to cut back on outings and vacations. He never felt stigmatised as a DI recipient and he shares his story openly with colleagues and friends. However, as he points out: ‘I had a “label of vocational retraining”, one might say … it is a label that still is … less heavy to bear than that of DI pensioner’. Currently, he works full-time as a social care worker in a residential care institution.

Like Antonio, recipients in the compliant ideal-type come out of their dealings with DI reassured, because they have received individualised support, help that has enabled them to regain a status of able-bodied/minded in society, and thus to cross back into the world of abledness. These individuals have found opportunities to negotiate their future status in society. They talk about their wishes being taken into account, speak of the co-construction of projects with institutional actors. Terms used to describe this support are: ‘one can breathe’, ‘bouncing back’, ‘one feels supported’, ‘accompanied’, ‘understood’ and ‘helped through administrative steps’. These terms do reveal that experiencing being labelled as disabled is a test. However, these interviewees’ sense of justice has not been mishandled, or not in a major way, by their DI experience. Another of their common traits concerns the opportunity given to them by DI to explore various paths towards vocational retraining; they retained the feeling that they belonged to a group that has choices, despite their impairment. Nevertheless, the uncertain and anxiety-provoking character of their experiences still comes through, as these individuals do also state that they appreciated being able to regain some self-confidence.

Their final position on the DI (dis)ability scale suits them, probably because they were able to re-attain a status of abledness (although only partly in one of the cases). The reference to ‘normality’ is thus clearly present in their discourse. In one case, a request of ‘change of position on the scale’ – that is, a demand to accede to partial abledness (through rehabilitation measures) – was made by a person who had been categorised as totally disabled. A consciousness of the hierarchy of capacities is also displayed, as Olivier’s interview shows us (46 years old, workshop instructor):

I was 28 when I first received disability benefits … I thought: ‘Wait, you are done for there … you have no value anymore.’ So there was work to be done, it did not happen in two shakes of a lamb’s tail. There were activities … that helped me to see … the advantages that went with it. I can’t work in an insurance office; I can’t be a company representative or head of claims… OK, I have [this impairment], … so then … in terms of identity, it’s not great. But I am able to paint. So I was able to have my workshop, to start working there, it was pleasurable, it helped me rebuild, then I found meaning and also value.

Another common feature of this group is that these men, after rehabilitation measures, have a higher socio-professional status than after their impairment was diagnosed; two of them even reached a higher status than the one they had before their impairment, as DI enabled them to follow a higher education curriculum. They consequently gained social and professional recognition, as autonomy and independence are the normative expectations of masculinity (Shuttleworth, Wedgwood, and Wilson Citation2012).

Given this context, it is not surprising that they express few criticisms. In the few cases when they do criticise, they focus on specific transitory elements: DI is slow and you have to wait, it is difficult to get hold of agents, DI cut short a measure or a measure did not go well because there were problems with the provider, and so forth. As we emphasised with regard to references to normality, their discourse supports to varying degrees both the hierarchical classification and the principles that underpin DI’s actions.

The ‘pacified’

In this second ideal-type, while the interventions of DI are evaluated positively on the whole, sizeable problems have been encountered. This ideal-type includes 12 of the 33 persons interviewed (five women and seven men), and is thus markedly larger than the compliant group. The median age of this group is 46.5 years, but the women are younger on average. Half of the recipients have received diagnoses of physical impairment, and the other half diagnoses related to mental health. Six have completed upper secondary-level education; three attended only compulsory school and three others attended university. All but one were working before their recourse to DI (e.g. as cook, bank employee, nurse, warehouse employee, sales person or woodcutter). This group varies with regard to the type of rehabilitation pathway followed. Whilst nine recipients were awarded training measures, three were offered only evaluation measures, sometimes associated with job support or coaching programmes. Three-quarters of them took part in several programmes (between two and four different measures). At the time of interview, five recipients had completed their rehabilitation course and were currently in work. Their employment activity rate (between 40% and 100%) suits them, except for one woman who would like to increase it from 40% to 80%.

For the pacified, while identity (re)assignations and the internalisation of a new status have necessitated negotiations, the outcome of the process is satisfactory. Disagreements relating to their sense of justice, however, have affected either their placement on the (dis)ability scale or their view of future occupation.

Massimo is a good example of this ideal-type. He is a manual worker, who has lived in Switzerland for 30 years. His work involved heavy physical activity that resulted in back problems, causing him to go on sick leave and necessitating the fitting of a disc prosthesis. At age 45 years, he became unable to work and suffers from depression. He was referred to DI, resigned from work, applied for unemployment benefits and is required to look for work, which he thinks is paradoxical in view of his poor health. Following medical evaluations, DI offered Massimo a pension, but it is much lower than his previous income. He then requested a rehabilitation measure from DI. It was accepted, but he is told:

Now you have to get it into your head that you are not the same as you were. … That is over, all of that. You are no longer 40. … You have to dress for the season.

His DI agent asked him to choose an occupation that suits him and to enter a placement financed by DI. He chose a craftsman’s trade and he started training, feeling ‘happy’ and ‘passionate’ about the opportunity.

However, when his course is in its advanced stages, a change of DI agent upends his plans. As the new agent views the job opportunities in his chosen field as very limited, she has put an end to his training course. Massimo disagrees with this decision:

I was very angry, because I was learning a trade … Starting another [training course] … I am not 20 anymore. And also, I had all my worries, my problems.

Within the programme he is now required to enter, he has a choice between internships in around 10 occupations. He opts for mechanics, enters pre-training and then starts a new training course. While it has not been easy for him to start a new apprenticeship, he achieved it, he states, through considerable effort and willpower. When we meet him, he is completing his first year of training. He has failed one examination, but he can sit it again. However, he remains concerned about his professional prospects, particularly in view of the economic context. He is afraid of ‘having to fall into unemployment again’, which would signify the failure of all his efforts: ‘You build your castle and then, at the end, someone with a hammer goes wham! Everything, back on the ground.’ Massimo has frequently felt judged for being on DI. Whilst he says that it has become easier to discuss, he still usually avoids talking about it ‘because it is still something that’s viewed as a disability’. ‘However, if earlier on in my dealings with DI it was’, as he says, ‘something taboo … now DI … it also means re-integration, for me’.

The characteristic of this ideal-type is that pacified recipients view their experience with DI as leading to success. They thus recognise that their place on the (dis)ability scale and/or their new professional orientation are appropriate, either because they were able to get their own views to prevail, or because they have accepted the place that they were offered. Thierry, 49 years old, who is training in watchmaking, explains that choices are restricted. He wanted to go to design school:

and then they clearly told me they would not consider it … There are few job prospects, very, very few. … I had to think. For me it was like … being faced with a big white wall. Then I had to start filling it in.

After a few internships, he finds the type of training course that suits him. But he ponders:

I do feel that in the end, DI, they have a hold on us. If you want to be mean and negative, you’d say they have us on a leash. … You have to be clear and answer on time, as requested. Because if you don’t, then it can quickly all go down the drain.

During the negotiation process, recipients must go through, as Laurent states, ‘a rather substantial process of self-questioning’, but also, as Julie, a 27-year-old commercial employee awaiting a DI decision, says, they must become aware that ‘our areas of competency, our skills, they are still there’. Among those who critique their own position on the DI (dis)ability scale, five interviewees, like Julie, view their assigned place on the scale as too low:

I did [to an extent] miss working pretty quickly. And since I already had IT skills … so I already knew how to file. And all of a sudden, there I was with nothing to do. … My motivation went south in a big way.

Yet it can also be seen as too high. Laurent, echoing the views of seven other interviewees, explains:

It is eating at me a bit, because of course people might say: ‘Yes, he can’t carry things, he shouldn’t carry things.’ But when … the customer isn’t there, there’s tidying up to be done, there is my painful knee, there are things to be set up, shelves to be filled.

Like Massimo or Thierry, recipients in this group were sometimes made to ‘dress for the season’ during the rehabilitation process. In other words, they had to adapt their aspirations to DI agents’ expectations. This created inner conflicts, particularly concerning the ways in which professional status and identity (re)assignation to abledness are conceptualised by DI. Four interviewees, such as Audrey (28 years old, in training as a retail sales operative), felt compelled to continue participating in a rehabilitation placement despite experiencing difficulties:

I worked [for a firm] for 9 months, to see whether they wanted to hire me or not. … My boss … he treated me more or less like a piece of shit. … I got insulted … And me, after a while, I was fed up. I broke down. I really broke down. … [The DI agent] didn’t give a damn, she said: ‘Hang in there, I understand. It’s normal. In life, some jobs are like that.’

In fact, according to Pierre (50 years old, social care worker and DI pension recipient), who feels he is ‘supported by DI [because he] fits into their framework’, relations are pacified when recipients’ expectations match those of the DI apparatus.

The most frequently expressed criticism, shared by all group members, concerns the ways in which DI operates. As Dominique (43 years old, bookstore salesperson and DI pension recipient) points out, ‘the problem is, the administration is excessively burdensome’; Julie has ‘the feeling that it just took a bit too long. This is life, I’m ready now, but no – there is another three months’ delay. … Because for me, in my head, I was ready to move to the next stage.’ She emphasises the ‘uncertainty’ associated with future decisions, ‘which is not very pleasant’. Laurent agrees; he adds that ‘you have to get moving … even if you have an illness, you have to move your butt’. Thierry also states that ‘nothing falls from the sky just like that. You have to look, ask, request information’. He has another criticism about timing. He thinks, generalising from his own situation (Boltanski, Darré, and Schiltz Citation1984) like other interviewees in this group, that the internship he was offered was too short:

15 days, [to see] whether you like it or not. But in 15 days, it’s very difficult to get an idea. So ideally, it should have been maybe 1 or 2, even 3 months … to get a long term view. Because this way, it’s just a short term view.

Finally, three participants question the very principle of hierarchical categorisation. Julie explains:

For people with disabilities, I think it is a bit regrettable how today, in 2016, people are categorised. It’s really like: you have to be beautiful, have a super high social level, … have a big house, 3 kids, be the director of I don’t know what. And that, that bothers me. You can be a good person, even if your life course is a bit different.

Laurent expresses a similar critique when he says: ‘It sounds like we are burdens but for me [DI recipients] should be on the same level as [other] human beings.’

The ‘rebel’

The 17 individuals in this third ideal-type are more critical. The group includes eight women and nine men aged from 20 to 64 years. The median age is 46 years. At the time of interview, six of the recipients were involved in a rehabilitation programme. As in the ‘pacified’ group, two-thirds of these individuals have completed an upper secondary-level education. Within the remaining third, four individuals had completed compulsory school and two had tertiary-level education. Just as in the other two ideal-types, about half of recipients (nine individuals) resorted to DI because of diagnosed physical health impairments, while six did so due to diagnoses related to mental health and two due to diagnoses of learning disability. However, those in this group are less likely to have been involved in training courses financed by DI (seven people have been involved). For the most part, they have been offered assessments of their work capacity (nine individuals) combined with vocational orientation (one individual), internships (two individuals) and integration measures (four individuals). This group includes the greatest number of recipients who participated in only one programme (seven individuals), who receive a DI pension at the time of the interview (three individuals) or who are awaiting a decision by DI (six individuals). Those who completed measures are least likely to be professionally active on the regular labour market (only three individuals).

Within this third ideal-type, recipients report on a process of ‘othering’ by the DI apparatus. While the criticisms expressed are similar to those found in the previous ideal-type (of the place attributed on the (dis)ability scale, of the professional (re)assignation process and of the (dis)ability scale itself), they are more numerous and more specific. Disagreement with the assignation of a given status is expressed in a more hostile manner and, most significantly, no pacification has taken place in the appraisal of what happened (or is still happening). The metaphor of an obstacle course is used repeatedly. Interviewees challenge not only the discourse of the DI apparatus, but they question its legitimacy to place them on a (dis)ability scale. As an example, let us present Marie’s experience.

Marie, aged 54 years at the time of the interview, had been working as a manager. However, physical health problems compounded by conflicts with management result in an episode of depression and complete inability to work. Her employer quickly calls upon DI. When Marie meets her DI agent, she is offered a first measure, an assessment with the goal of determining whether she can continue working in her previous field and, if this does not seem possible, to reorient her towards another type of job. Marie explains that the questions asked during this assessment did not make sense to her. Her health status worsens, and her DI agent informs her that she can no longer aspire to managerial roles.

The agent then informs her that she needs to enrol in a ‘pre-rehabilitation resilience training course’, which turns out to consist of sorting used clothing. Marie feels humiliated, but her DI agent convinces her that she must start ‘at the bottom’. It seems to her that the other people placed in the sorting workshop are either unmotivated to work there or unable to do so. As she notes, she is working alongside various categories of welfare recipients, asylum-seekers, people who have run out of unemployment benefits and ‘drug addicts’. Her self-esteem collapses and she drops out of the programme.

She is placed in another rehabilitation measure called ‘progressive training’, with the aim of gradually increasing her work stamina. She feels she has climbed back up a rung on the ladder. Indeed, her DI agent has taken on board her request for more qualified work, and she is assigned to IT tasks. She feels appropriately supported. However, working alongside professionals recounting their latest holidays makes her painfully aware of her current lower status. She again ceases to attend. A fourth measure gives her the impression of going backwards. It takes place in a sheltered workshop and she feels out of place, because most participants are very young. Moreover, in order to be admitted to the workshop, she is shocked to have to take tests in basic mathematics, grammar and spelling. She stops attending after two months. Within the context of these three last programmes, it is through the comparison with others that Marie comes to understand her assigned place on the (dis)ability scale. This shows that identity is constructed through comparing and contrasting it with that of others.

For every programme in which she has been involved, Marie describes having felt highly pressured by DI to reach the set objectives (a work capacity of 50%), a goal she sees as incompatible with her illness (which is a generalising statement; Boltanski, Darré, and Schiltz Citation1984). Following the lack of success of her last placement, her DI agent informs her that ‘there is nothing else for her’, except a pension. However, the decision to award her a pension is delayed. She feels reduced to a number, to a file forgotten under a pile on someone’s desk. When she does get the DI decision, the criteria used are not made explicit. Moreover, the pension awarded is lower than the one her physician had requested. Her doctor tells her that ‘you can’t do anything to counter the DI machine’.

Marie mainly criticises the place on the (dis)ability scale attributed to her by DI; the rehabilitation measures offered have been too difficult or too easy, too demanding or, on the contrary, ‘humiliating’. In the same category of critiques, Yann (24 years old, working in a sheltered workshop and DI pension recipient) explains that his DI agent turned him down for a rehabilitation programme because he was ‘too slow’; ‘that it would be better for [him] to have a place in a sheltered workshop’; that he ‘would fit in better there’. This assessment causes him to ‘totally panic’. He explains:

What if then … they orient me somewhere I don’t like… I don’t see why just to please people I should be buried in a thing that will make me want to shoot myself. … Having a disability is already a pain in the ass in itself, but on top of it to have to be dragged into something that you absolutely can’t stand, that’s even worse.

Aline (32 years old, child-care centre assistant) refers, like Marie, to her self-comparison with other people encountered in a rehabilitation programme, explaining that she views them as lower than herself on the (dis)ability scale:

I couldn’t fit in … There were people there that had a much more noticeable disability than me, much more serious. Me, I was there, but fatigue is the only reason why I have to change my occupation.

On the contrary, Gabriel (41 years old, communication specialist and DI pension recipient) ‘feels that they actually overestimate [his] abilities and that’s a bit difficult to take’.

Within this group, strong reservations were also expressed about the professional (re)assignation conducted by DI. Sarah explains, for example, that her DI agent:

did not listen to my wishes … My life’s project was an arts and crafts job. And them, they would not have any of it. In the beginning, they thought I should have a pension. … But then they also said … you have a choice but … you are responsible for giving up your own rights. … I would rather he act like a human being.

Within this ideal-type, 13 recipients not only criticise proposed measures, but also oppose in a more global manner the very conception of the (dis)ability scale and its operating principles and mechanisms. In other words, they question the way that (dis)ability percentage is assessed. For instance, Sonia (46 years old, recipient of a DI pension) explains that DI agents ‘had no appreciation for professional experience or for training … after compulsory education. In fact, they were going to make us sit tests like the ones you take at the end of compulsory school. … It is totally inappropriate.’ Francesca (64 years old, seeking employment) explains that in the programme she participated in, ‘you had to count paper clips and other … stuff. … For me, it was terrible. … I said: “But what! This is work?”’ She also expresses her disapproval with the evaluation of her disability rate:

When I saw the evaluation they gave me, that’s when I was disappointed. … I was supposed to be able to work full-time. But … I couldn’t do heavy work, stairs, vacuum, not stand too much, not sit too much, not too much this and that. So I couldn’t do anything.

Criticism of DI interventions by the rebels are for the most part addressed at the (re)assignation process. This implies, as our literature review indicated, ruptures as well as the internalisation of a new devalued status that is socially problematic to take on. The following is how Yann puts it:

The image that sticks to people who are on a pension … Today DI pensioners are still viewed as lazy asses or as cheaters. Some of them are, of course. But that’s because of a few assholes who haven’t found anything better to do with their lives. So because they don’t want to work, they fake all kinds of illnesses.

He does not want to tell people that he is a DI recipient, ‘because right away we are seen as profiteers and all that, as leeches’. Yet these critiques also demonstrate a fundamental refusal when confronted with the injunction to internalise a ‘motivated and involved stance’ (Piecek et al. Citation2017). This requirement is rejected even more strongly when DI shows little interest in a given recipient’s desire to be involved in specific programmes, and when the standardisation of measures – the ‘one size fits all’ cited by Vandekinderen et al. (Citation2012) – leads them to see proposed programmes as inappropriate for them.

Conclusion

While, early in their dealings with DI, almost all recipients interviewed (26 of 33 individuals) saw it as stigmatising, it has become an institution like any other for interviewees in the groups we have named ‘compliant’ and ‘pacified’. This is not the case for those we have defined as belonging to the ‘rebel’ group, for whom DI remains an institution that causes social depreciation and/or imposes devalued social statuses. However, our research shows that while situations vary greatly, DI systematically challenges one’s position in a world that is hierarchically organised on the basis of capacities. This institutional space is where statuses are fixed, provoking doubts, fears, hesitations and hopes, and often involving a painful letting-go of previous identities. Clearly, coming face to face with hierarchies based on capacities is a test. The uncertainty about one’s worth and that of others in an ableist world wanes – or grows – in interactions with the DI universe. The experience of this test, described by our interviewees, sheds light on the unequal value placed on society’s members on the basis of capacities.

The experience of identity (re)assignation by persons entering rehabilitation processes takes place in the context of recent changes in Swiss disability policies characterised by moral discourses about welfare dependency and abuses of social benefits by recipients (Ferreira and Frauenfelder Citation2007). Indeed, as in other national contexts (for example, Garthwaite Citation2011; Soldatic and Morgan Citation2017), Swiss DI recipients are described by the media, by the general public, by politicians and by welfare institutions as ‘shirkers’, ‘benefit cheats’, ‘not bothered’ or ‘wasters’. This rhetoric about welfare abuse generates multiple effects. On the one hand, it generalises the suspicious manner in which so-called ‘disabled people’ are viewed and puts their rights to benefits into question. On the other, it results in the tightening of controls and requirements to conform to DI expectations in order to maintain access to social security benefits and services (Despland Citation2012). This type of discourse constructs disability as a motivational problem that could be remedied by the introduction of tighter control mechanisms. Our research shows that this representation is unhelpful as well as limiting. Our interviewees’ experiences show that motivation and engagement – meant to be at the heart of current DI reforms (Piecek et al. Citation2017) – depend on the opportunity to negotiate with DI about one’s status, on the one hand, and on the outcome of such a negotiation on the other. Our analysis unpicks these complex processes and invites us to rethink the ways in which disability policies are implemented.

Finally, our findings show that our interviewees’ very critique of the identity (re)assignation they have experienced has major effects: it may cause them to reproduce the processes to which they have been subjected, but it may also lead them to challenge the validity of hierarchies based on capacities. On the one hand, they may distance themselves from ‘others’. This is a logic of social distinction, which reproduces ableist hierarchies. For instance, the institutional approach that involves assigning different categories of beneficiaries to the same rehabilitation measures caused our interviewees to question the way in which they themselves had been categorised, and to label other participants as ‘sicker’ or more ‘disabled’. In fact, in the vast majority of cases, their critique actually focuses on the inadequate ways in which categorisations and (re)assignation processes are carried out. In these critiques, the manner in which the institution 'behaves' is viewed as the problem, rather than its mission or the normative principles upon which it is founded. However, the interviews do also bring to light the norms of justice that present a challenge to the labelling power of DI. Some critics indeed open up the possibility of subverting the (dis)ability scale, disability not systematically being viewed by beneficiaries themselves as intrinsically negative.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the journal reviewers for their stimulating comments, Toni M. Calasanti and the Department of Sociology of Virginia Tech (USA) for their useful comments on an oral presentation of this article in 2017, the colleagues of NCCR LIVES, and Élisabeth Hirsch Durrett and Nyan Storey for the English translation.

This work was undertaken at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland (HES-SO).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

Notes

1 Project 156131.

2 In order to ensure anonymity, fictitious names have been used. The occupations indicated are those the subjects practised at the time of interview. Age and professional status are only specified the first time the participants are quoted.

3 36.6% of economically active persons in Switzerland in 2017 work part-time (Federal Statistical Office, table 03.02.01.16).

References

- Angeloff, Tania. 2011. “Des Hommes Malades du Chômage? Genre et (ré-)Assignation Identitaire au Royaume-Uni.” Travail et Emploi 128:69–82. doi: 10.4000/travailemploi.5476

- Aronovitch, Hilliard. 2012. “Interpreting Weber’s Ideal-Types.” Philosophy of the Social Sciences 42 (3):356–69. doi: 10.1177/0048393111408779

- Bergold, Jarg, and Stefan Thomas. 2012. “Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological Approach in Motion.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 13 (1) http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1201302.

- Bertrand, Louis, Vincent Caradec, and Jean-Sébastien Eideliman. 2014. “Devenir Travailleur Handicapé. Enjeux Individuels, Frontières Institutionnelles.” Sociologie 5 (2):121–38. doi: 10.3917/socio.052.0121

- Boltanski, Luc. 2009. De la Critique. Précis de Sociologie de L’émancipation. Paris: Gallimard.

- Boltanski, Luc, and Eve Chiapello. 2005. The New Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Gregory Elliott. London: Verso.

- Boltanski, Luc, Yann Darré, and Marie-Ange Schiltz. 1984. “La Dénonciation.” Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 51 (1):3–40. https://www.persee.fr/doc/arss_0335-5322_1984_num_51_1_2212.

- Bröckling, Ulrich. 2016. The Entrepreneurial Self. Fabricating a New Type of Subject. Translated by Steven Black. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Campbell, Fiona Kumari. 2009. Contours of Ableism. The Production of Disability and Abledness. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage.

- Chouinard, Vera, and Valorie A. Crooks. 2005. “Because They Have All the Power and I Have None’: state Restructuring of Income and Employment Supports and Disabled Women’s Lives in Ontario, Canada.” Disability & Society 20 (1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/0968759042000283610

- Claisse, Frédéric, and Marc Jacquemain. 2008. “Sociologie de la critique: la compétence à la justification.” In Epistémologie de la Sociologie. Paradigmes Pour le XXIe Siècle., edited by Marc Jacquemain and Bruno Frère, 121–41. Bruxelles: De Boeck.

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 1990. “Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria.” Qualitative Sociology 13 (1):3–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00988593

- de Wolfe, Patricia. 2012. “Reaping the Benefits of Sickness? Long-Term Illness and the Experience of Welfare Claims.” Disability & Society 27 (5):617–30. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.669107

- Despland, Béatrice. 2012. L’obligation de Diminuer le Dommage en Cas D’atteinte à la Santé. Son Application Aux Prestations en Espèces Dans L’assurance-Maladie et L’assurance-Invalidité, Analyse Sous L’angle du Droit D’être Entendu. Genève: Schulthess.

- Dorfman, Doron. 2017. “Re-Claiming Disability: Identity, Procedural Justice, and the Disability Determination Process.” Law & Social Inquiry 42 (1):195–231. doi: 10.1111/lsi.12176

- Federal Statistical Office. 2018. “Taux d’occupation. Table number cc-f-20.04.02.04.01.” https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/situation-economique-sociale-population/egalite-femmes-hommes/activite-professionnelle/travail-temps-partiel.assetdetail.4522136.html

- Ferreira, Cristina, Arnaud Frauenfelder. 2007. “Y en a Qui Abusent…’ Identifier, Gérer et Expertiser Des Ayants Droit de la Politique Sociale.” Carnets de Bord en Sciences Humaines 13:3–6. http://www.unige.ch/ses/socio/carnets-de-bord/revue/article.php?NoArt=126&num=13.

- Foucault, Michel. 2001. Dits et Écrits. Tome 2: 1976-1988. Paris: Gallimard.

- Fougeyrollas, Patrick, Line Beauregard, Charles Gaucher, Normand Boucher. 2008. “Entre la Colère… et la Rupture du Lien Social: Des Personnes Ayant Des Incapacités Témoignent de Leur Expérience Face Aux Carences de la Protection Sociale.” Service Social: 54 (1):100–15. doi: 10.7202/018346ar

- Fraser, Nancy. 2005. Qu’est-ce Que la Justice Sociale? Reconnaissance et Redistribution. Paris: La Découverte.

- Garthwaite, Kayleigh. 2011. “The Language of Shirkers and Scroungers?’ Talking about Illness, Disability and Coalition Welfare Reform.” Disability & Society 26 (3):369–72. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2011.560420

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago: Aldine.

- Goodley, Dan. 2014. Dis/Ability Studies: Theorising Disablism and Ableism. London: Routledge.

- Grut, Lisbet, and Marit H. Kvam. 2013. “Facing Ignorance: people with Rare Disorders and Their Experiences with Public Health and Welfare Services.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 15 (1):20–32. doi: 10.1080/15017419.2011.645870

- Hamner, Doris, Jaimie Ciulla Timmons, and Jennifer Bose. 2002. “A Continuum of Services: Guided and Self-Directed Approaches to Service Delivery.” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 13 (2):105–13. doi: 10.1177/10442073020130020601

- Heenan, Deirdre. 2002. “It Won’t Change the World but It Turned my Life Around’: Participants’ Views on the Personal Advisor Scheme in the New Deal for Disabled People.” Disability & Society 17 (4):383–401. doi: 10.1080/09687590220140331

- Johnson, Robyn Lauren, Mike Floyd, Doria Pilling, Melanie Jane Boyce, Bob Grove, Jenny Secker, Justine Schneider, and Jan Slade. 2009. “Service Users’ Perceptions of the Effective Ingredients in Supported Employment.” Journal of Mental Health 18 (2):121–8. doi: 10.1080/09638230701879151

- Kinn, Liv Grethe, Helge Holgersen, Marit Borg, and Svanaug Fjaer. 2011. “Being Candidates in a Transitional Vocational Course: experiences of Self, Everyday Life and Work Potentials.” Disability & Society 26 (4):433–48. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2011.567795

- Knijn, Trudie, and Frits van Wel. 2014. “Better at Work: Activation of Partially Disabled Workers in The Netherlands.” ALTER – European Journal of Disability Research/Revue Européenne de Recherche Sur le Handicap 8 (4):282–94. doi: 10.1016/j.alter.2014.09.005

- Lantz, Sarah, and Greg Marston. 2012. “Policy, Citizenship and Governance: The Case of Disability and Employment Policy in Australia.” Disability & Society 27 (6):853–67. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.686881

- Lewis, Ruth, Lynn Dobbs, and Paul Biddle. 2013. “If This Wasn’t Here I Probably Wouldn’t Be’: disabled Workers’ Views of Employment Support.” Disability & Society 28 (8):1089–103. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.758031

- MacQueen, Kathleen M., Eleanor McLellan, Kelly Kay, and Bobby Milstein. 1998. “Codebook Development for Team-Based Qualitative Analysis.” Field Methods 10 (2):31–6. doi: 10.1177/1525822X980100020301

- Martuccelli, Danilo. 2015. “Les Deux Voies de la Notion D’épreuve en Sociologie.” Sociologie 6 (1):43–60. doi: 10.3917/socio.061.0043

- Miles, Matthew B., A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Morris, Rosa. 2013. “’Unjust, Inhumane and Highly Inaccurate’: The Impact of Changes to Disability Benefits and Services – Social Media as a Tool in Research and Activism.” Disability & Society 28 (5):724–8. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2013.808093

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2009. Sickness, Disability and Work. Keeping on Track in the Economic Downturn. Background Paper presented at the High-Level Forum, May 14–5, Stockholm, Sweden. https://www.oecd.org/els/emp/42699911.pdf.

- OFAS (Office fédéral des assurances sociales) 2017. Statistique de l’AI 2016. Tableaux détaillés. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/catalogues-databases/publications.assetdetail.2702448.html.

- Parker Harris, Sarah, Randall Owen, Karen R. Fischer, and Robert Gould. 2014. “Human Rights and Neoliberalism in Australian Welfare to Work Policy: Experiences and Perceptions of People with Disabilities and Disability Stakeholders.” Disability Studies Quarterly 34 (4). doi: 10.18061/dsq.v34i4.3992.

- Piecek, Monika, Jean-Pierre Tabin, Céline Perrin, and Isabelle Probst. 2017. “La Normalité en Société Capacitiste. Une Étude de Cas (assurance Invalidité Suisse).” SociologieS http://journals.openedition.org/sociologies/6412.

- Pires, Alvaro. 1997. “Échantillonnage et recherche qualitative: essai théorique et méthodologique.” In La Recherche Qualitative. Enjeux Épistémologiques et Méthodologiques., edited by Jean Poupart, Jean-Pierre Deslauriers, Lionel-Henri Groulx, Anne Laperrière, Robert Mayer, and Alvaro Pires, 113–69. Montréal: Gaëtan Morin.

- Revillard, Anne. 2017. “La Réception Des Politiques du Handicap: une Approche Par Entretiens Biographiques.” Revue Française de Sociologie 58 (1):71–95. doi: 10.3917/rfs.581.0071

- Shildrick, Margrit, and Janet Price. 1996. “Breaking the Boundaries of the Broken Body.” Body & Society 2 (4):93–113. doi: 10.1177/1357034X96002004006.

- Shuttleworth, Russell, Nikki Wedgwood, and Nathan J. Wilson. 2012. “The Dilemma of Disabled Masculinity.” Men and Masculinities 15 (2):174–94. doi: 10.1177/1097184X12439879

- Soldatic, Karen, and Helen Meekosha. 2012. “The Place of Disgust: Disability, Class and Gender in Spaces of Workfare.” Societies 2 (3):139–56. doi: 10.3390/soc2030139

- Soldatic, Karen, and Hannah Morgan. 2017. “’The Way You Make Me Feel’: Shame and the Neoliberal Governance of Disability, Welfare Subjectivities in Australia and the UK.” In Edges of Identity: The Production of Neoliberal Subjectivities., edited by Jonathon Louth and Martin Potter, 106–33. Chester: University of Chester Press.

- van Hal, Lineke B. E., Agnes Meershoek, Angelique de Rijk, and Frans Nijhuis. 2012. “Going beyond Vocational Rehabilitation as a Training of Skills: return-to-Work as an Identity Issue.” Disability & Society 27 (1):81–93. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.631799

- Vandekinderen, Caroline, Griet Roets, Michel Vandenbroeck, Wouter Vanderplasschen, and Geert Van Hove. 2012. “One Size Fits All? the Social Construction of Dis-Employabled Women.” Disability & Society 27 (5):703–16. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.673275

- Vedeler, Janikke Solstad. 2009. “When Benefits Become Barriers. The Significance of Welfare Services on Transition into Employment in Norway.” ALTER – European Journal of Disability Research/Revue Européenne de Recherche Sur le Handicap 3 (1):63–81. doi: 10.1016/j.alter.2008.12.003

- Wagner, Shannon L., Julie M. Wessel, and Henry G. Harder. 2011. “Workers’ Perspectives on Vocational Rehabilitation Services.” Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 55 (1):46–61. doi: 10.1177/0034355211418250

- Weber, Max. [1904] 2013. “Die ‘Objektivität’ sozialwissenschaftlicher und sozialpolitischer Erkenntnis.” In Gesammelte Aufsätze Zur Wissenschaftslehre, Max Weber., 146–214. Paderborn: Historisches Wirtschaftarchiv.