Abstract

The article describes the work of the first three authors, who are young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), on an ‘inclusive research’ project. For this project, these young adult activists worked together with university researchers and students, and with organizations serving disabled people as active members of the research team. Through this research project, 24 participants who were youths with IDD were interviewed about their important relationships and the activities they do in their communities. The research found that belonging really matters to the youths interviewed. These young adult activists talk about some of the activities they they did as research team members and some of their important contributions to the research. For example, they participated in writing the interview questions, recruiting study participants, and making a film about what the research found.

Introduction

Academic research about intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD)Footnote1 guides policies, programmes, and services that directly affect the lives of people with IDD. Having an activist role in research is one way that people with IDD can have some control over their own lives. Our Voices of Youths inclusive research project (the Project) included three young adults with IDD as research team members. We describe our collaboration on the Project among three young adults with IDD, academic researchers from two large Canadian universities, and community service professionals. This four-year Project was funded by the Canadian government. Throughout the article, we highlight the perspectives of the first three authors, who are the team members with IDD.

The Voices of Youths Project

Our research team met monthly to make important decisions about the Project. Its overall purpose was to understand friendship, community engagement, and quality of life for teens and young adults with IDD from their own perspectives. Our aim was to help improve programmes and services that young people with IDD need to access so that they feel like they belong in their communities.

Twenty-four youths with IDD and their friends were interviewed. We video-recorded the interviews so that the youths could use more than just words to show what was important to them. Then, we watched the interview videos many times to understand the patterns of ideas that the youths told us were important. We put these patterns together to make what we call the Belonging Framework. Then we wrote an accessible report and two academic publications (Renwick et al., Citation2019) about it. We did presentations about it at many conferences and made the Belonging Matters film about the Project’s findings (see for a snapshot from the film).

Figure 1. A still from the Belonging Matters film showing the first three authors of this article who served as the Project Consultants.

We made the film so that our findings would be accessible to as many people, with and without disabilities, as possible (to watch the film, see Renwick and DuBois Citation2017 for the link to click on). It was launched at a public event at the University of Toronto which Project participants and their families, disability advocates, service professionals, policy-makers, and researchers attended.

Inclusive research

Walmsley (Citation2004) developed the term ‘inclusive research’ to stress that it differs from other types of research which study people with IDD as subjects (the people who are studied). Inclusive projects like ours have active members with IDD on the research team, so that their views and ideas can help to shape the research.

Roles of the authors

Articles written by inclusive research teams often leave out who did what and how the team members with IDD were actively involved. For this article, the members with IDD – Zoe, Peter, and David – and three trained academic researchers – Rebecca, Denise, and Jasmine – were the authors.

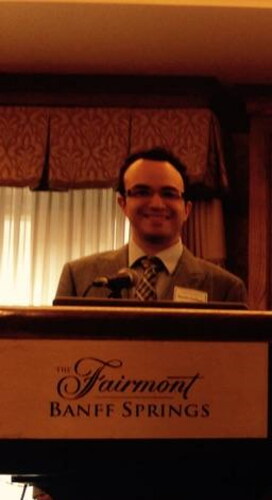

Before David passed away in 2017, he had written about his experiences as part of a presentation he made on behalf of the Project at a research conference in 2016 (see for a picture of David presenting at the conference). Parts of his writing were adapted by Zoe and Jasmine for this article. Before he passed away, David stated that he wanted to be an author on this article. His writing and name as an author are included in this article to honour his wishes.

Figure 2. Photograph of David Conforti, one of the Project Consultants and the third author, presenting at a national research conference on behalf of the Project.

We each wrote parts of this article on our own. We also met regularly over several months to write together. Peter, who lives in another city, participated by telephone. Denise found several articles on inclusive research, which the authors read. Zoe and Jasmine wrote the first drafts of the paper, with input from Peter and detailed comments from Denise and Rebecca. After submitting our article, we received feedback from the journal editor. Zoe led the effort to work together on re-writing the article.

In the rest of the article, we use ‘we’ when talking about ideas and experiences shared by the authors. We use our names to share our individual voices (e.g. Zoe thought …; Peter experienced …).

The title of project consultant

Everyone on the Project had a title. Team members from community organizations were called ‘community collaborators’. Rebecca, Denise, and Jasmine were ‘academic researchers’. Zoe, Peter, and David were paid ‘project consultants’.

These titles were carefully chosen, especially the title of project consultant. From Zoe’s perspective, project consultant was best because Zoe, Peter, and David were asked to contribute a lot to the Project based on their lived experiences. Because the academic researchers viewed the consultants as activists and experts on their own experiences and on the experiences of youths with IDD, they consulted with the project consultants at each stage of the Project.

Power: in-between team meetings

In inclusive research, the balance of power among team members with and without IDD is really important. Power means having a voice in important decisions and sharing control over the research process. Power includes how a team works together and how projects are managed and organized (Frankena et al. Citation2015; Strnadová and Walmsley Citation2018). In our team, we aimed to make most of the important decisions together during team meetings, which all members of the team were expected to attend. However, a number of university rules and procedures were barriers to reaching full power-sharing. The university setting (environment) strongly influenced how, when, and where we could do some of our project activities. In addition, because the academic team members worked at the university, they were associated with the power and influence that were part of this setting.

For example, ideally the project consultants would have been involved from the start of the project when the topic and research questions were chosen. Yet, until funding and certain approvals from the university were obtained, the project consultants could not be included in the Project. Therefore, the academic researchers and community collaborators chose the Project’s original goals.

After the Project was funded, the project consultants took an active role in all research decisions made at team meetings. Peter thought there was a good relationship between everyone on the team, and he often mentioned the meetings when describing his role on the Project. David felt proud of being the team member who missed the fewest meetings. In his writing about the project, David said that attending meetings made him feel more competent, more in control, and able to manage time better. He also talked about his role as a professional, who had ‘a seat at the table’. For Zoe, the working relationship that developed in the meetings was a good foundation for everyone. Meetings were a place where each step of the research process was discussed until everyone was on the same page.

For Jasmine, the power-sharing that happened during the meetings made sure that all of the team members had a more equal say. For example, we met monthly and shared important news about our personal and professional lives. We ate together when we celebrated holidays and our team’s achievements. Socializing together created closeness and trust that made us feel more equal as we related to each other as team members.

Yet while the team meetings provide a ‘snapshot’ of what made the team inclusive, they also highlighted some of the inequalities that still existed within our team. As with any large-scale research project, there were several university deadlines, procedures, and expected outputs (e.g. the final report, the film, and journal articles) that affect the timing and the way in which a successful project must run. Looking back on it, by setting the agendas for meetings, by keeping our project ‘on time’, and by choosing what would be shared with the team (e.g. the Project’s budget) and when, the project coordinator and academic researchers held a significant share of the power.

Because of this, Jasmine sometimes had the uncomfortable thought that the role of the project consultants and community members was to approve the silent, hidden decisions that were made by the academic researchers in between meetings. For example, Zoe objected to the term ‘youths’, saying: ‘That’s like, what old people would call us, not what we would call ourselves’. She preferred the terms ‘teenager’ and ‘young adult’. Yet ‘Voices of Youths’, the Project’s title, was chosen by the academic researchers, who had put it on the proposal for funding and had already paid a graphic designer to make the Project’s logo.

Doing good research is challenging

The project consultants contributed their thoughts, ideas, and experiences in ways that improved the research process and outcomes. They also contributed their lived experiences as users of programmes and services for youths with IDD. Zoe saw their role as helping other team members to understand teenagers and young adults with IDD. They helped to make decisions about how the study was done, such as choosing the language for recruitment information and developing interview questions. David was known as ‘the glue’ of the Project. He shared his experiences and contributions at a national research conference. Peter acted in the video used to recruit participants and was a Master of Ceremony at our public film launch. Zoe took the lead on many other aspects of the project, such as this article. For example, she organized writing meetings of the authors, read about inclusive research, and wrote large portions of this article.

The project consultants’ valuable contributions were also reflected in the Belonging Matters film. Not only were they the team’s spokespeople in our film, their voices showed depth and honesty about their experiences of belonging and not belonging in community life.

But the Belonging Matters film and other public events also represented moments of discomfort and tension for Zoe. She found it more difficult than Peter and David to be in the spotlight. Zoe felt that, as the project consultants, they were under a lot of pressure in making this film because they were its stars. She wanted to be close to perfect. But on her way to the film studio, she got lost. It was also a very hot summer day and even hotter under the studio lights. So filming was physically demanding and emotionally tough for Zoe who felt it was like being an ‘open book’. She also worried about seeing herself on film for the first time, wondering ‘Are other people judging me? What will they think about me?’ Even though making the film was more challenging than expected, in hindsight, Zoe is pleased that she participated and challenged herself to engage in public speaking. Zoe felt that the trust between team members made her comfortable enough to open up about topics she would not have usually talked about.

After hearing Zoe talk about why the day was hard for her at a writing meeting, the other authors were able to relate to some of those feelings. Research includes many moments when researchers are uncertain of the outcomes or may not succeed. For the academic researchers on the Project, past difficult experiences had prepared them for future struggles. It had also shown them that success and growth can result from challenge, even if it does not feel like that in the moment. But, for the project consultants, the Project may have challenged them in ways that they had not experienced before (perhaps due to lack of opportunity or other barriers). As the team reflected and talked about this uncomfortable moment for Zoe, they shared her perspective that research is about challenging yourself because you are trying to influence society and help make it better for the next generation. Then they will not have to go through the same things that she and others with IDD have experienced.

Conclusion

This article describes the sincere attempt by the Voices of Youths research team members to do inclusive research. From our perspectives, the Project is an example of how, despite some challenges, partnerships like ours can be equal in many ways, produce high-quality research, and offer learning opportunities for both youths with IDD and academic researchers. We also think that universities could change some of their rules and procedures to ensure that collaboration with, and active participation of, people with IDD can lead to high-quality research. However, inclusive research could also be done with activists at community-based advocacy centres (Townson et al. Citation2004). For our current inclusive research projects, we have made some changes, such as bringing on project consultants earlier in the process and aiming to include a more diverse team.

Zoe called the Project ‘a roller-coaster ride’ with triumphs and setbacks. She saw the destination of the roller coaster as helping teens and young adults with IDD to belong in their communities. Peter said the experience made us all look at research in totally different ways. For all of us, having seen the Belonging Framework develop out of what participants told and showed us has been a privilege. The team members continue to have pride and passion for exploring pathways to belonging. Working on the Project was life-changing as we strove to help pave the way for the next generation of inclusive disability research in Canada.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study participants and their families.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest to report for any of the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We have chosen the terminology ‘youths with IDD’ because this is how the youths on our research team and our study participants self-identified.

References

- Belonging Matters: Knowledge Mobilization Film on Voices of Youths Research Incusive Methods and Findings. (2017). [film] Directed by Rebecca Renwick and Denise DuBois. Toronto, ON: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v1/4brAsG2CidwA&feature1/4youtu.be.

- Frankena, Tessa Kim., Jenneken Naaldenberg, Mieke Cardol, Christine Linehan, and Henny van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk. 2015. “Active Involvement of People with Intellectual Disabilities in Health Research: a Structured Literature Review.” Research in Developmental Disabilities 45–46: 271–283.

- Renwick, Rebecca, Denise DuBois, Jasmine Cowen, Debra Cameron, Ann Fudge Schormans, and Natalie Rose. 2019. “Voices of Youths on Engagement in Community Life: A Theoretical Framework of Belonging.” Disability & Society 34(6): 945–971. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1583551

- Strnadová, Iva, and Jan Walmsley. 2018. “Peer-Reviewed Articles on Inclusive Research: Do Co-Researchers with Intellectual Disabilities Have a Voice?” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 31(1): 132–141.

- Townson, Lou, Sue Macauley, Elizabeth Harkness, Rohhss Chapman, Andy Docherty, John Dias, Malcolm Eardley, and Niall McNulty. 2004. “We Are All in the Same Boat: Doing ‘People-Led Research.” British Journal of Learning Disabilities 32(2):72–76.

- Walmsley, Jan. 2004. “Inclusive Learning Disability Research: The (Nondisabled) Researcher’s Role.” British Journal of Learning Disabilities 32(2): 65–71.