Abstract

In this Current Issues article I explore how the world of art can show a different view on ‘madness’. Mad Studies, as an emergent academic field, has the possibility to offer alternative and contrasting views on madness. I argue that the current bio-medical model where ‘madness’ is reduced to ‘mental illness’ denies us the possibility to hear different views and see a person behind a diagnosis. The art world, through visual representation, can present us with an ‘unknown’ factor of ‘madness’ where madness remains a mystery that we will never truly grasp. Visual art can also depict the real human beings and real stories behind ‘diagnoses’.

The current medical model of ‘mental illness’ tries to make out of madness an object of ‘brain study’, an object of purely medical enquiry which can be reduced to scientific explanations, denied of its mystery.

The current system of diagnoses tries to make out of madness a chemical chart, where we have ‘bipolar disorder’, ‘schizophrenia’, or ‘schizoid disorder’, hiding behind the classification many different lives, totally distinct from each other’s stories, and various people with often fascinating narratives.

Mad Studies, by contrast, as an emergent academic field, challenges the predominant view of ‘mental illness’, where the purely medical model dominates the debate in most countries in the western hemisphere. Mad Studies proposes ‘a critical discussion of mental health and madness in ways that demonstrate the struggles, oppression, resistance, agency and perspectives of Mad people to challenge dominant understanding of “mental illness”’ (Castrodale Citation2015). Thus, it gives space for additional exploration of madness, from different views, which could challenge the status quo of the ‘biochemical’ model.

However, it becomes ever more difficult to offer alternatives where the purely medical model sees itself increasingly incorporated across society. Mad Studies, as Beresford and Russo (Citation2016) argue, risks being assimilated into the status quo of the main biochemical model, where stories of ‘survivors’ will be heard only if they reflect the predominant understanding of ‘mental illness’ like ‘any other illness’, where only those survivors who agree with ‘mental illness’ will be heard.

But madness should retain its aura of mystery, and it should always leave room for different views and stories, where some ‘mad’ people or ‘survivors’ want a place in the exploration of the unknown, where there is still room to laugh about one’s madness, and where some ‘patients’ want to offer different stories, different perspectives, different views on ‘madness’, sometimes mysterious, but sometimes very mundane.

The art world is a world which still offers us these alternatives. It is also a world that shows the dilemma of ‘madness’. The dilemma of doctors trying to put a definite label on something which cannot really be explained. Or when it explains something, we want to hear the ‘other’ side, the real, human story. We want to see what each ‘diagnosis’ hides. Behind each ‘depression’ is its own story of sadness, and behind each ‘psychosis’ there is a distinct and unusual journey, sometimes terrifying and, on occasions, very exciting.

The art world also demonstrates that we, as human beings, will always remain attracted to the mystery of madness. People are fascinated by madness, by what it hides. The art world is the world where madness belongs, where it should belong: in the narrative of the ‘unknown’, of the unexplored. ‘Psychosis’ might be defined as a loss of touch with reality by scientists, but for those who experience it, it is a reality which can be magical. It can also be trivial, but, as a human being, I am also interested in the ‘small’ details behind each ‘madness’. I am interested in a ‘patient’, in his story, in his experience with madness.

The story of the current psychiatry and its reduction of the humankind to an object of scientific enquiry can be seen in the famous painting by Pierre Aristide André Brouillet (1887), A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière. It shows us a clinical demonstration given to postgraduate students by the famous neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (Netchitailova Citation2019).

This painting was painted before the official history of psychiatry started, but it shows the state of psychiatry as it is now. There are several doctors who claim to understand madness through words, without clear medical tests confirming the ‘diagnosis’.

But as a human being, when I look at this painting, I am not interested in what Charcot has to say. I can guess what he is trying to say.

I am interested in the patient. Her name is Blanche and I want to hear her story. I want to know what happened to her, and I want to know how she ended up where she is: in the middle of a clinical demonstration. I am also curious as to why no one tries to put a jacket on her, and why she seems like she is ‘asleep’. From the rare mentions of Blanche, I learned that she worked as seamstress, and that she was affected by epilepsy. Charcot used her for his weekly demonstrations to show his ‘skills’ in hypnosis, during which Blanche would suffer from convulsions. They stopped after Charcot had died.

The art world is one world that still shows us the mystery of madness, and our fascination with it as human beings.

We are fascinated by Van Gogh not only because of his genius paintings but also due to his history of ‘madness’. Modern doctors try to impose occasional diagnoses on Van Gogh, such as ‘schizophrenia’, ‘bipolar disorder’, or ‘personality disorder’.

But as a sociologist and a fellow human being, I am interested in the story of Van Gogh, in the glimpses of his ‘battle’ with the unknown. I want to read that after his spell in an asylum, he painted 75 paintings in 70 days and completed more than 100 drawings and sketches. I read with deep curiosity about his life, that he was unlucky in love and was once rejected by Eugenie Loyer when he lived in London. I am less interested in what exactly happened with his ear, but more in the final moments of his life, when, before attempting to take his own life, he painted his Tree Roots (1890).Footnote1

On this painting we can see different leaves and roots giving way to trees, where the colourful ‘palette’ so unique to Van Gogh is very much present.

The painting, of course, created a lot of debates and controversies. Can we really see any moments of ‘madness’ in it? Can we witness the state of mind of the artist right when he was contemplating ending his own life?

Or we take another painting by Van Gogh as an example: The Starry Night (1889) that he painted while living in the asylum.Footnote2

What does it tell us, this painting? It is an amazing painting, one of the best, with stark colours and unusual sky. We can see a small village in it, and a church, and a beautiful sky, with yellow stars and moon. But I am also fascinated by the ‘human story’ of the painting. How was life in the mental asylums then? What were the patients eating? What kind of ‘activities’ did they have?

The biological model of ‘mental illness’, or its recent argument that ‘mental illness is like any other illness’, deprives us of these ‘background’ stories. It tries to create a narrative that something tragic, but sometimes beautiful, can be reduced to the notion of ‘bipolar disorder’; that something which cannot be explained is defined as ‘hallucinations’.

But as a human being I am curious about each particular ‘hallucination’. Where do they come from? What do they hide? I refuse to believe that it is biologically based, and that they are not real. They are real for the person experiencing them, so why do we deny, then, the person the truth of his journey?

What if the hallucinations are actually real, and only few of us have the possibility to witness the parallel reality?

This fascination of what is behind ‘madness’ can be seen in a painting by Mathias Grunewald, The Temptation of St. Anthony (1512–1516).Footnote3

Saint Anthony was a Christian monk who was tempted by demons during his sojourn in the Egyptian desert. Today, his mystical experience would be called ‘psychosis’, with his temptation described as ‘hallucinations’. But it is the numerous paintings depicting the mystical experience of Saint Anthony which present us with a different view, a different story, and a different view on madness.

On the painting by Grunewald we can see the real demons, and these demons were real for Saint Anthony too. Who should we believe: the psychiatrists or a person telling us his own story, his visions?

The view of madness as something that we can explain started, of course, during the enlightenment, the age of reason. It was Foucault, the French philosopher, who said that how we view madness, is defined by social constructs of any given time.

Thus, during the Renaissance period, mad people were looked upon with curiosity and sometimes even with admiration. They would also be put on the ships and sent into ‘nowhere’, but they were not locked up, and some artists asked the eternal question: but what is really madness? Should we look at some individuals as mad, or judge, rather, the society which is also mad?

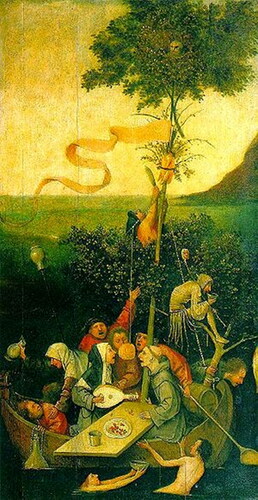

Thus, the famous painting by Bosch, The Ship of Fools, or The Satire of the Debauched Revelers, presents us with a different view on madness.

On this painting we can witness the debauchery caused by some high-standing members of society. The two figures in front are a Franciscan friar and a nun, which was quite unthinkable at the time of the painting (1490–1500) (Netchitailova Citation2019).

But this painting, in particular, has an additional meaning. The ship itself holds the biggest symbolism. Because it was on this kind of ship that the mad were put and sent into the fools’ paradise (into nowhere) in the Middle Ages.

On this painting, however, there is only one fool, who is put there with a purpose: to remind the viewers that it is the ship of fools indeed which is depicted. But by placing other characters, so-called ‘sane’ members of the society on it, Bosh made his view on madness quite clear.

Who is really mad? An innocent fool, not harming anyone, or those who harm others in the name of God?

By looking at this painting, I also want to know the story of this ‘fool’. Who was he? What happened to him? How was life on the ships for people who were put on them?

Another painting, The Scream painted by the Norwegian painter Edward Munch (1893), also poses the existential question of ‘madness’. The Scream shows us a lonely figure of a man, who is obviously distressed, with two hands on his head, as if trying to shut oneself from the world.Footnote4

Is this how ‘depression’ looks or anxiety? Or is it the society itself which we can witness on this oeuvre d’art? Or was it indeed provoked by the fact that the sister of the painter happened to be in the mental asylum when Munch painted it? Does this painting express indeed the ‘anxiety’ of the modern man?

By looking at paintings we can ask these questions. Unlike the modern diagnoses, art gives us the possibility to explore, to venture into different views and interpretations. It gives us stories and a narrative behind. There is no real narrative anymore behind the classification of diagnoses and symptoms; it reduces different aspects of human life to ‘mental illness’, to ‘mental illness like any other ‘illness’.

The art and painters, however, always explored and continue to explore the remaining mystery of ‘madness’. They paint us stories and possibilities of different interpretations. As human beings, we always want ‘stories’, we want more details of real human life, hiding behind the increasing number of diagnoses.

When I contemplate the paintings by Kim Noble,Footnote5 a modern artist, who has ‘dissociative identity disorder’, I am interested in what is behind. I want to learn more about different personalities that make the paintings.

I am listening with great curiosity when Kim talks and gives interviews and I want to learn more about her as a person. Her art is a way for different personalities to express themselves, and her art is beautiful. When I look at her paintings, I do not think of ‘mental illness’, I think of an extremely interesting and vibrant person, who gives us a gift of her art.

I am glad that art still retains the mystery of ‘madness’; that it removes the scientific explanation of all human misery, and presents questions rather than answers.

Doctors try to give us succinct, definite answers, but is there really an answer to the human psyche?

Should we not retain some mystery?

Should we not leave some space for the unknown, for something that we cannot really explain?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Tree Roots by Van Gogh can be seen online: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/tree-roots/WQGYd-7iPjW88g?hl=en-GB&ms=%7B%22x%22%3A0.5%2C%22y%22%3A0.5%2C%22z%22%3A9.295089552092103%2C%22size%22%3A%7B%22width%22%3A1.2548849463499612%2C%22height%22%3A1.2374999999999996%7D%7D. Accessed on 23.03.19.

2 The Starry Night by Van Gogh can be seen online: https://www.google.com/search?q=van+gogh+the+starry+night&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjex_PbvdzgAhUjonEKHTYED08Q_AUIDigB&biw=1366&bih=657#imgrc=qqSZWcdvoaRUNM. Accessed on 23.03.19.

3 The Temptation of Saint Anthony by Grunewald can be seen online: https://www.google.com/search?q=grunewald+The+Temptation+of+St.+Anthony%E2%80%99&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjhsqC5vtzgAhX_URUIHcDCBK8Q_AUIDigB&biw=1366&bih=657#imgrc=-MgxfknQcPzxmM. Accessed on 23.03.19.

4 The Scream by Munch can be seen online: https://www.google.com/search?q=the+scream+munch&tbm=isch&source=iu&ictx=1&fir=-4j9OW6FXR40KM%253A%252C1iewB9Kj8MJFQM%252C%252Fm%252F01f3_n&usg=AI4_-kT3BPhjBX8ABsHPwWL7PtDJB7QaPQ&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi4mIiOwNzgAhXOVBUIHc3_A3QQ_B0wHHoECAMQEQ#imgrc=-4j9OW6FXR40KM. Accessed on 23.03.19.

5 See the website of Kim Noble: http://www.kimnobleartist.com/). Accessed on 23.03.19.

References

- Beresford, P., and J. Russo. 2016. “Supporting the Sustainability of Mad Studies and Preventing Its Co-Option.” Disability and Society 31(2): 270–274. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2016.1145380.

- Castrodale, M. A. 2015. “Book Review ‘Mad Matters: A Critical Reader in Canadian Mad Studies’.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 17(3): 284–286. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2014.895415.

- Netchitailova, E. 2019. “The Mystery of Madness Throughout the Ages.” Mad in America. https://www.madinamerica.com/2019/01/mystery-madness/