Abstract

Care ethics considers the moral good as arising within practices and in people’s experiences in these practices. This contribution applies a care-ethical approach to inquire into the effects of a major change in the social domain policy in The Netherlands. The new policy is based upon the expectation that young adults with Mild Intellectual Disabilities (MID) become ‘active citizens, participating in their neighborhood’, with the support of care organizations and local municipalities. Accordingly, care responsibilities were transferred to the local level (municipalities). On this level, however, basic insights were lacking concerning the needs and wishes of the young adults with Mild Intellectual Disabilities, and concerning the possibilities for local collaboration. Research was performed by taking Joan Tronto’s definition of care as a starting point and applying a method adequate to capture young adults’ experiences in one municipality. We conclude that this neighborhood is not an environment wherein they can participate.

This article offers new insight into the effects of a major change in long-term care policy in the Netherlands that emphasizes participation.

Care ethics focusses on practices, in which more than two people are involved, that help meet needs of care (or fail in this respect).

The article presents an inquiry into the experiences and needs of six participants living in a Dutch facility where youths and young adults with Mild Intellectual Disability are supported to participate in society, as expressed by themselves in photos and interviews and as observed through the method of shadowing.

The results of this inquiry are three aerial photos that show how the participants live in supporting networks with gaps, underscoring their experiences of being displaced and feeling unacknowledged in the vicinity of their home.

Different organizations directed at care for young adults with Mild Intellectual Disability can learn from the care needs that result from this way of organizing care.

Points of interest

Introduction

Over the last decades care ethics has emerged as an interdisciplinary form of ethics with an outlook that offers insights into the ‘moral good’ distinct from more traditional strands of ethics. Care ethics is driven by social issues and questions and takes the normative stance that the moral good can only be found by examining what appears to be good in practices of living together (Leget et al. Citation2017, 6). Rather than taking a viewpoint ‘above’ practices, and deciding impartially about right and wrong, care ethics is focused on research in practices and observing (‘receiving’) what people experience, find valuable, and feel that matters (Leget et al. Citation2017, 7). By reflecting conceptually on the empirical evidence, any (implicit) normativity resulting from the researched practices of care might consequently be elicited (Leget et al. Citation2017, 7).

This paper takes a care ethics perspective on a major change in the social domain policy in the Netherlands in 2015. Many forms of long-term care were transferred from the institution to the municipalities. A municipality in the Netherlands means a town or a district that has a local government. The municipalities were stimulated to collaborate with professional care organizations on a local level to provide these forms of care. However, problems were indicated by a specific municipality in the south of the Netherlands facilitating a home for youths and young adults with a mild intellectual disability (MID), and responsible for their inclusion in the neighborhood in which they live. Both this municipality and the Cura organization (pseudonymized name) lacked insight into (1) the needs and wishes particularly of the young people living in the facility and (2) how institutions could cooperate to meet these needs and improve participation in the neighborhood. We take Joan Tronto’s definition of ‘care’ as a starting point to answer these questions. In her definition Tronto (Citation1993, Citation2013) considers care as a practice of maintaining, continuing and repairing the ‘life-sustaining web’ in which people aim to live ‘as well as possible’ together with others and their environment. This definition seems particularly apt to take a look at care provisions on a local level after the policy change, and see if the service provider and municipality indeed facilitate or form a supporting network in which needs are adequately met.

This article is structured as follows. In the following section we briefly sketch the core changes of the Dutch policy, specifically regarding young adults with MID. Subsequently, the central ideas of care ethicist Joan Tronto are discussed. Her vision offers several entrances to gain insight into the changed way that care is provided in the aforementioned municipality. Then the methodology and findings of the empirical part of the study will be reported on. Finally, in the discussion section, we will reflect on these findings from a care ethical point of view in order to formulate what good care for the participants of this research might entail, including several recommendations for practice and further research.

The policy of ‘participation society’ in The Netherlands

The Netherlands saw fundamental health care system changes within the social domain in 2015, regulating support for people with intellectual disabilities (ID) living at home through a new law, called the Social Support Act (Wet Maatschappelijke Ondersteuning). Instead of central regulation, primary responsibility for this care had now been placed with the municipality (Kroneman et al. Citation2016). The new policy puts a strong emphasis on citizenship and the personal strength of people with ID, stipulating their participation and inclusion, which is also in line with the ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights or Persons with Disabilities in the Netherlands (DCD, 2016). As a result, people with ID living in ‘ordinary’ neighborhoods are expected to be more independent and self-reliant and to participate sufficiently (based on their capabilities) in society (Smulders et al. Citation2016).

However, studies show that this is certainly not self-evident for young adults with MID. They often experience several social barriers, such as having few friends or experiencing loneliness in their neighborhood, and consequently feel no part of it (Novak et al. Citation2013; Verdonschot et al. Citation2009). According to Overmars-Marx, Pepping, and Thomése (Citation2018), inclusion policies often ignore the exclusion faced by people with (M)ID in society. They may have left the old geographical places of exclusion, but the discriminatory context into which they move remains unchanged, and they are still regarded as ‘other’ (Meininger Citation2013 in Overmars-Marx, Pepping, and Thomése Citation2018). The facilitation of inclusion therefore requires not only adjustments from people with (M)ID, but also changes within society (Overmars-Marx, Pepping, and Thomése Citation2018).

Research shows two important, interrelated gaps. First, professionals do not always have the required competences and knowledge to recognize the experiences and concomitant wishes of youths and young adults with MID (Werner and Stawski Citation2012). Second, many institutions within a municipality are not familiar with the target group (see e.g. Eadens et al. Citation2016) since taking care of their needs has not been part of the municipality’s responsibilities for many decades, but has only been assigned to them in this policy change. Although the Dutch government has indicated that more customized work is needed for young adults with MID, including more care in the neighborhood and stronger relationships between different care organizations and institutions (Moonen Citation2017), it is still insufficiently clear what the exact needs of people with MID in the neighborhood are and how institutions should work together for the best possible care and support in the neighborhood. With this research we aim to contribute to these required relevant, yet lacking, insights.

Tronto’s vision on care

Care ethics is a strand of ethics that criticizes one-sided views of people as individuals who are independent and self-sufficient, describing the ideal relationship in more or less contractual terms, and of people as acting as equal citizens within a public realm. As Rogers (Citation2016) has argued, the social model of disability needs care ethics to be able to reflect on our responsibilities to other human beings and people with ID in particular, as they ‘are always interdependent, and many wouldn’t survive without a caring other(s). Removing social barriers without committing to a moral, political and ethical formulation of caring is not an option; care and caring can no longer be seen as a private matter’ (Rogers Citation2016, 34).

Pathbreaking care ethicist Joan Tronto (Citation1993, Citation2013) strongly criticizes the current dominant ideology of self-reliance, self-management and autonomy, and she investigates what it would mean if we organized our society differently, namely by focusing on care. For Tronto, care should be seen broadly as

…a species activity that includes everything we do to maintain, continue and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, our selves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web (1993, p. 103).

In this definition (devised by Tronto with Berenice Fisher), care is seen as a collective practice in which more than two people are involved, with implications on the personal, institutional and even global level.

For our purposes, we emphasize the latter part of the definition, namely the complex, life-sustaining web. This extended understanding of care allows us to understand care as a practice that goes beyond a dyadic exchange between a caregiver and a care receiver. Instead, care is taken as an interrelated whole of relationships in which needs are noticed and care is organized, given and received, or not. This vision allows us to analyze care on a societal level. Tronto’s distinction of five interconnected phases of care offer an adequate tool for this analysis. The subsequent phases are: caring about, caring for, care-giving, care-receiving, and caring-with, each of which contain a central moral element: attentiveness, responsibility, competence, responsiveness, and trust/solidarity (Tronto Citation2013). These phases and moral elements become an analytical tool for collective care policy and practices by asking whether policy and practices are effectively caring since they:

…adequately acknowledge the needs and concerns of the group through attentive looking and listening?,

…actively assume responsibility with regard to these needs and concerns?,

…competently provide the necessary care that meets these needs and concerns?,

…have checked its adequacy through the response of the recipients of care?,

…are committed to make life livable and worth living in the moral complexities of dependency, vulnerability and otherness? (Tronto Citation2013, 35)

By asking these questions, we take a care ethical perspective as a critical approach to the neoliberal ideal of self-reliant entrepreneurs, a jargon that is sedimented in actual policies. This is our normative point of departure: if needs and concerns in a society are unnoticed; or are noticed but no one takes responsibility for them; or are noticed and responsibly organized but not competently performed; or if all of this is arranged with the best intentions, but the care receiver’s needs are not met; or, finally, if all this has been adequately done, but care provision remains a struggle for each separate need or group, and does not lead to more consistent care provisions on which dependent people can rely; then society fails in moral respect (cf. Tronto Citation1993, 126).

This vision on care provided the starting point for our empirical qualitative research into ‘living in the neighborhood’ by young adults with MID. Please note that the non-inclusive language, including the term ‘disability’ that has been used so far in this article was taken from the policy documents and corresponding research proposal that founds this research. As Mykitiuk, Chaplick, and Rice (Citation2015) state: ‘even the word “disability” is unavoidably negative: structurally it signifies a loss or a lack, a state that exists only because it falls short of something better’. The proposal was approved by the Dutch national funding organization for health research and care innovation (ZonMW Citation2020), which called for research into these transferred responsibilities. Although we adopted the language of these sources, from this point on, we will apply inclusive language where we present our own research and therefore use the phrase ‘participants’ in order to mirror Tronto’s idea that we are all members of our society, and to avoid ‘othering’ of people with a disability (cf. Tronto Citation1993, 70–72). The following section explains the method used in this study including how we have used instruments that are specifically suitable for participative research into the ‘life-sustaining web’ that supports ‘living in a neighborhood’.

Methods

Design

This study’s underpinning involves a normative stance that the good can best be established by looking at the lived experiences of the participants and if their needs are adequately met, which is also more in line with contemporary ideas on disability research practice.

To accomplish this, we applied Responsive Evaluation (RE), a methodology which tries to overcome imbalances of power by including various stakeholders and by giving voice to marginalized voices and groups. By doing so, RE offers the possibility to map the meaning and values of all stakeholders concerning the issues under study (Woelders and Abma Citation2015). In this case this entailed focusing mainly on the stories of the young adults involved, and the values that were of interest to them. Our role as researchers was one of being facilitators of the dialogue, interpreters of stories and meanings, educators who establish mutual understanding and Socratic guides who raise self-evident questions, rather than distant experts (Abma Citation2006).

The research project team consequently consisted of 2 experienced academic researchers (including first author IvN) with a background in both Responsive Evaluation and care (ethical) research and two research assistants. The initial analyses were carried out by the whole project group and a final analysis by both authors.

Normally, a RE consists of five phases (Abma and Widdershoven Citation2006, Visse, Abma & Widdershoven Citation2011 and Woelders and Abma Citation2015):

identification of the participants with needs and the social conditions

interviews with participants;

organization of focus groups with participants;

organization of multiple focus groups (heterogeneous groups);

dialogically drawing up of an agenda for negotiation or action.

Because of the relatively short duration of the project (six months), only phases 1 and 2 were carried out in this study. Also, two additional methods were used in aid of attaining a comprehensive insight into the experiences of the participants: photovoice and shadowing.

Photovoice is an effective, qualitative method in which photography is used to collect information from people with ID (Hergenrather et al. Citation2009; Jurkowski and Paul-Ward Citation2007). The method of photovoice is particularly suited ‘to convey the perspective of the person using the camera, allowing them to think about their context and share the story of the pictures that they take’ (Richards, Lawthom, and Runswick-Cole Citation2019; see Simpson and Richards (Citation2018) for a more critical evaluation of the method and its limitations). The participants take photographs of situations, events or things that (i) play a role in their daily life in the neighborhood and (ii) are important to them. These photos offer an insight into what daily life in the neighborhood means to them.

Shadowing is a relevant method for vulnerable people who have difficulty articulating their experiences (Van der Meide Citation2015). The participants could be considered to be vulnerable in this sense. Shadowing was applied to capture as well as possible what they experience daily (see Patton Citation2002). Attention has been paid to both articulated language and non-articulated language (Van der Meide Citation2015).

Setting

The research population consisted of participants living in a municipality in the south of The Netherlands where they receive care and support from a service provider. The home where the research took place had various forms of living such as: group living, living in an apartment and living in a bungalow. A total of 15 people with MID between the ages of 18 and 65 live together in these houses. The property is located in a neighborhood where both rental and owner-occupied homes are located. Opposite the care home is a nursing home. On the corner of the street there is a community center including a child healthcare center. Six persons, 3 males and 3 females, between the ages of 18 and 26 took part in this study.

Ethical issues

Written and oral information was provided both by the researchers and the support workers of the facility. The latter had insisted on the need to protect the participants from unusual living circumstances and to have the research be as little intrusive as possible to their daily routine. The informed consent procedure was carefully supervised, and it was repeatedly checked (through telephone calls and on site) whether an appointment was still suitable. On several occasions consent was withdrawn in the minute that the shadowing or the interview should have started. The wishes of the participants were always actively protected by the support workers and respected by the researchers.

Pseudonyms were given to the participants and to the organization. The data has been handled with the greatest care and was deleted within six months after the end of the investigation. Data was only exchanged between project members via a secure CloudDisk. Downloads and automatic copies were always deleted.

Data collection

In a two month period, six participants were shadowed daily at different times during the day by the research assistants, following everything they did. Immediately after shadowing, the research assistant made a report of what she had actually observed, supplemented with questions and reflections on everything she noticed. In addition to following the participants individually, the research assistants were present for four half-days, between 4 and 8 p.m. in the shared kitchen of the group home, in order to get a picture of how the participants were living together in the facility. Field notes were later made of the observations.

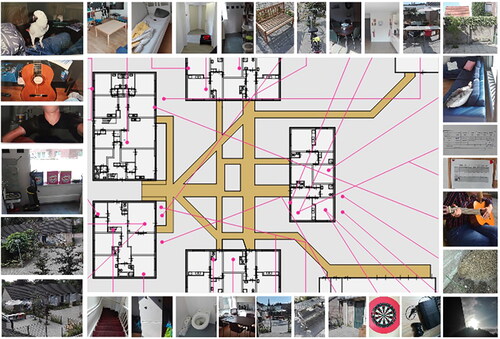

After the participants had been shadowed, they were asked if they wanted to take pictures of events, objects or other matters that are important to them over a period of four weeks. All six participants contributed to this. Five participants took photos using their mobile phones and one used a disposable camera provided by the researcher. The six participants took a total of 54 photos. The number varied from 2 to 23 photos per person. These numbers varied because the participants dealt very differently with what they found important.

In addition to the shadowing, four of the six participants were also interviewed extensively about their lives and about the photos. The interviews were semi-structured and dealt with issues that were mentioned during shadowing and that could be discussed in more depth in the interview. The interviews lasted between 15 and 75 min. All the conversations conducted were recorded and transcribed and presented to the participants with the possibility to adjust it (member check).

Analysis

During the collection of the data, regular consultations took place between the whole project team for triangulation purposes. The data were analyzed thematically (Creswell Citation2013). This was initially done by the whole project team together and in a later stage again by the first and second author. The first step involved reading and actively listening to what the participants said (content), how they said this (form) and when and where (place and time). Fragments of all the different data were marked, discussed and sorted by mutual consultation, comparing them with each other, discussing how they agreed or differed, and how they fit in with experiences gained by the researchers themselves during shadowing (cf. Van der Meide and Olthuis Citation2012).

With regard to the transferability of the findings we prefer to refer to this as ‘petite generalizations’: the aim is to create an understanding of a specific situation (thematic, in trajectories and in the narrative vignette) (cf. Abma and Stake Citation2001). This requires detailed information or ‘thick description’ (Geertz Citation1973, 231–267).

Findings

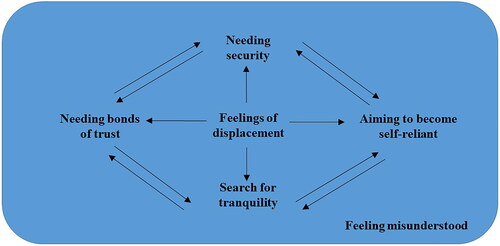

This section presents the findings in two ways. We start with a thematic presentation of the experiences of the participants. below shows how the six themes are interconnected. Secondly, we present three different ‘trajectories’, which aim to offer a comprehensive and palpable image of what the participants experience on a normal day in their living environment. The trajectories include the photos taken by them, ordered spatially, which show the paths that the participants walk in their daily lives.

Thematic presentation of experiences

Feeling displaced

Prior to coming to live in the group home, the participants had moved several times and had lived outside of the care of service provider (Cura). Sometimes they ended up with Cura through a foster family. But also within Cura some participants had moved frequently, for example to a more suitable form of living. These experiences resulted in a feeling of displacement. For example, one of the participants (R1) explained that he was taken out of the protected environment of a foster family and placed in this form of living. Because of this he had to get used to the fact that he had to get to know the home, the counselors, other clients, but also the environment. He had to build a new protected living environment for himself:

In one go, I went from being protected - from something that I knew very well - to something else [the group home] […]. Look, here you are also protected, this is also a protected thing, but it is different. [R1]

He missed the proximity of a familiar family life and also noticed the differences between the foster family and the group home. He expressed this as a feeling of being left alone:

In the family there was mom and dad […] and a sister and brothers and that is not the case here. Here you are more focused on yourself […]. I’m just all alone. [R1]

Yes, because they all live there […] I have the feeling that they occasionally forget about me and yes, you do not experience daily things with them either. [R2]

When you meet each other you chat with each other. When you come together for a coffee. Occasionally ‘come and do a cup of coffee’ […]. Or maybe once […] organize a barbecue together. [R1]

Yes, I think that would be nice, I think so. If people are nice too, why not. I am ready for ideas anyway. [R2]

The need for a bond of trust

The participants express the need for a bond of trust with their counselors. Practical help or support leads to a strengthening of this relationship of trust. Some participants only receive support and trust from their personal counselor, while others have this link with several counselors. With R5 this is expressed in the feeling that she is being helped in daily life and R2 experiences support in the tips that he receives from the supervisor. R1 also describes how he is helped:

Support with making friends. Support with appointments or commitments […] Or when I find something difficult for example. [R1]

That also makes me a little more confident when […] you are seen. And you feel that you are being helped and that is the point. That you are always able to express yourself […]. Even when it’s busy. That they’ll come back to that… [R5]

R1, R2 and R3 all emphasize the importance of the personal counselor and the support they receive in personal conversations:

That means a lot. That is always a trusted person who you can trust […] for everything. [R1]

When it comes to work, I’d rather talk to a supervisor about it. [R2]

Yes, that is really a trusted person. You can really do well with that. [R3]

Needing certainty

The participants have a strong need for certainty and tend to stick to what is known to them. This is evident, for example, from the value that R2 attaches to the work schedule of the supervisors. As a result, he knows what to expect. If he has problems or wants to discuss situations with his personal supervisor, he can plan ahead:

I think that gives me some peace and quiet to […] be able to see, okay, the supervisor is here. [R2]

I find that very difficult to do things [that] are unfamiliar […]. I don’t know, because I’ve never done it. [R2]

I’ve never done it, so I don’t know if… Yes, I really don’t know. I am afraid to give an opinion on that. [R3]

It gives me certainty, […] of course you do something that you like, but you also have to look at what comes in and it also provides financial certainty. [R5]

The need for self-reliance

Just as much as needing certainty and security in a care-assisted life, there is a desire to be self-reliant. This ambivalence is an important characteristic of the participants’ experience of living in the neighborhood. For example, they want to be able to make their own decisions, but at the same time R2 acknowledges that he needs help with this:

If I have to arrange things […]. Yes, then I want me to be really involved. I prefer to do it myself, sometimes it is not always possible. But yes, I think that’s important yes. That sometimes I can arrange my own things. [R2]

I think I am fine here and I can learn things here anyway. [R2]

It is, like, examining yourself: ‘how do I balance myself?’ When are things too much, when I am away from home too much? [How] do I make sure that I can be myself again in my own environment? That is actually what I want to learn a bit here. [R5]

That I can work with colleagues who have experience in their field and […] who also want to take me to that level, from a permanent employee […], that I might become that too. That I can copy a little of what they do. [R2]

If they disagree with something, they will say so, but they will not blame you for your mistakes. Then they usually say: That is what our support is for. [R1]

Because it is free here and closer by….here it is free and there it costs me, yes. I can’t carry the extra cost next to the schooling that I am doing now. It is quite an expensive thing. [R5]

Yes, I just don’t want that. That is actually, that is, with all the traveling of course.

…with public transport. So I’m thinking about buying a car myself. [R3]

Because I usually go to my internship with this bike. I also go to my friends with that bike. With that bike I do almost everything to get away. [R2]

Seeking tranquility

Every day the participants are confronted with unrest, as evidenced by the noisy spaces in which they find themselves, such as their own working environment. Because of all the stimuli they incur, their heads can get ‘filled up’ which they experience as very tiring. The home is not experienced as a particularly soothing environment. People regularly talk, argue, shout, play loud music and walk in and out a lot. Every participant experiences this unrest in a different way and searches tranquility in his or her own way. Some seek it in the home, by withdrawing to their own room, such as R3:

They all live together there and I live quietly here on my own. That’s the good thing. Sometimes I can’t handle the noise because it’s so busy in my head. Then I have to take some time off, say…… You could say, it is a sort of re-charging.,. [R3]

Occasionally I can simply unwind there […]. Yes, for example, if [I] have a setback of some sort… [The] last time I did that was last week. Then, in my head it was also a little bit chaotic and stuff, so I just thought I’d get rid of my frustrations. [R2]

Yes, simply, if it is too busy here or I don’t feel like sitting in my room or just sitting outside, I usually go there… I just enjoy sitting there quietly for a while […]. [R4]

When it was up to here and then I wanted to go […] Cycle to [the dunes], [then] I went there . [Then I sat on a] bench and I just wrote. [R5]

The rest have a lot of contact with each other. At first I also had a lot of contact with everyone. But lately I think, I’m like, there is too much gossip and too much arguing, with each other […] And I want to keep myself out of it, so I’m like, I don’t want to interfere. [R1]

When you do […] see each other then it is just ‘good evening’ or ‘good afternoon’ […]. You can always ask how they are doing, but that’s about it. [R1]

I don’t like quarrels. I always try to keep myself out of it. [R3]

There is something at the back of our house, but I hate it. All the people argue there. [R3]

I don’t really want to sit there because it is quite noisy to hear everyone’s stories. Often I don’t find it very interesting. [R2]

Feeling unacknowledged

The participants indicate that they sometimes feel that they are not considered as full. This is reflected in their having to adapt, being misunderstood and wanting to be treated equally. When asked what he would think if he had more contact with the neighborhood, R1 says the following:

Very often you also hear of people with a disability, these are very low people with a very low IQ […]. That they are just those ‘Downies’ or I don’t know what. […] And then, yes, if you do have contact with the rest of the neighborhood […] then they can also see that this is not the case at all and that we can also just be cheerful and that we also enjoy life and enjoyment, for example ‘let’s drink a glass of wine together in the evening’ […] or a nice coke or that we are just playing soccer. [R1]

They were looking for something else for me and they had [inquired] at a fairly large company if I could work there and then they said that […] I worked at Cura and that I lived at Cura and that I am a boy with a disability. The doors were closed immediately. Immediately there was no way in anymore. [R1]

We have been [acting] negative in the neighborhood lately. […] There have been months when loud music was constantly played. […] That the neighbor has often stood at the door and the neighbor was then seen as a nagging person. And at the same time I think yes, if you turn on the music at twelve o clock in the night … [R1]

Then I don’t have to tell my story. People at Cura already know this, they are the same as me. [R4]

Trajectories

The trajectories that were developed include the photos taken by the participants (photovoice) and informal conversations. The idea of trajectories is that through visualizing where people have important experiences, the ‘owners’ of these experiences attain a voice. Hence these trajectories are ordered spatially. The aim here is to show where the participants from the group home have important experiences when living in the neighborhood.

At the start of this research, the idea was to make one trajectory. However, after further analysis, we were surprised to find a clear (geographical) distinction between the places where the photos were taken. On the first trajectory (Figure 2) one can see a map of the group home itself with the photos taken in the home and the accompanying garden. The second trajectory (Figure 3) shows the photos on an aerial photo of the municipality. An aerial photo rather than a map was chosen to show the concrete environment because this would be more insightful to the participants. On the third and final trajectory (Figure 4) you can see the photos that the participants took of the wider environment of the municipality.

By ordering the collected findings on three distinct trajectories instead of one, we see a remarkable concentration of important experiences within the group home itself, evidenced from the large number of photos that were taken here. The participants indicate that they rarely walk around in the village, and this shows itself too on trajectory 2, with few photos taken there. Also remarkable is the large number of photos taken in places at a rather large distance of their living environment. The visible lack of important experiences in the direct vicinity of the group home indicates that a geographical delineation of ‘neighborhood’ may be much less obvious and important for the participants. The group home can ultimately be seen as a separate neighborhood for them ( and ).

Discussion

In section 2 we presented Tronto’s view of ‘caring’ as a fundamental daily human practice with political and moral implications, and of a society as morally admirable when taking care of her citizens. In this discussion section, we apply Tronto’s view as a tool for reflecting on the empirical findings of section 4, and set up a discussion between theory and practice, in order to see where caring does not come about, leads to conflicts, or shows discrepancies between policy and practice.

Discussion between theory and practice

In our theory section, our normative point of departure, in brief, is that if attentiveness is lacking, responsibility not taken, care incompetently performed, needs go unmet, and if care remains uncertain and a permanent struggle, then care in a society fails in moral respect. The reverse is true as well: a society counts as a caring one if attentiveness, responsibility, competence, and responsiveness form a cyclical process that meets needs and leads to reliable provisions. In this section we bring these theoretical insights in discussion with the empirical findings presented in the previous section.

Needs that are being met

Caring comes about, if the cyclical process of care takes place. This means that the needs are noticed, responsibility is taken, the needs are met competently, the responses of the recipient matter, and certain reliable structures are built, from which certainty for all can be derived. In the practice that we inquired, this is the case with regard to several needs, like a bond of trust and certainty. The bond of trust, for instance, is key for this form of living and the main reason for the participants to live here in this stage of their lives. This is confirmed in expressions like: ‘That is always a trusted person who you can trust for everything’. The certainty of a cyclical process of care is also clearly expressed: ‘That also makes me a little more confident when […] you are seen. And you feel that you are being helped and that is the point. That you are always able to express yourself […]. Even when it’s busy’. This inquiry confirms the importance of the regular presence of someone who is attentive and can be trusted, who helps in practical ways, and with whom one can communicate throughout for adequate care. And certainty can be given through simple means like a visible working schedule of the supervisors.

Critical remarks can be made here too. For despite the fact that bonds of trust and certainty are confirmed, other bonds of trust and familiarity had to be broken in order to live here, causing the participants to feel displaced; and the certainty that is offered within this facility also works counterproductive.

Needs that are challenging

Other needs, like developing self-reliance, and finding tranquillity, pose serious challenges, which the participants face with various success. The participants underscore the wish to become self-reliant, but they also state that they cannot do this without help. This help is offered by the supervisors in various ways, which they appreciate and value. However, needing the help that is available in this particular facility lies at the root of them having to travel long distances by themselves for friends, family, school and internships. The costs connected to transport also means that other possibilities for meeting with peers or gaining self-trust, like sports, are very limited. By lack of an affordable alternative, one participant exercises in the elderly home across the street: ‘Because it is free here and closer by….here it is free and there it costs me, yes. I can’t carry the extra cost next to the schooling that I am doing now’. The need for tranquillity seems to be easily missed in the group home and is met basically by themselves.

Even though the support by counsellors is vital for meeting the need of development towards self-reliance, one can also establish a lack of care on the institutional and societal level, due to insufficient material, social and professional conditions. The most urgent lacks concern the vicinity of family, friends and social contacts or (sports) clubs, (financial) means of transport and leisure activities, and tranquillity. These matters become even more urgent in the following section, on the needs that go unmet.

Needs that go unnoticed and unmet

Two needs remain mostly unnoticed: one is the need that is caused by feeling displaced; the other is caused by the feeling of being misunderstood. The feeling of displacement was mentioned by the participants, but became really clear when they were asked about their life’s trajectories. All expressed how this particular living facility is a temporary living place, established particularly for their peer group, in their stage of development. Some elaborated upon the line of various living places that they have resided. One participant had lived in a foster family and was then placed in the group home. The (family) bonds that were broken off were lamented. The feeling of being displaced is also expressed in the many ways in which the participants need to adapt to living in a place and with people whom they have not chosen themselves. Some really hate the social gatherings. Some adapt to their living conditions by retreating themselves, while others walk away from the home to find tranquility.

In various ways a support network or activity in the neighborhood might have been helpful, but a lack of acknowledgment in the neighborhood has caused the participants to avoid going to certain places (like a beauty salon) in the vicinity and to join people like themselves: ‘People at Cura already know this, they are the same as me’. However, the participants discriminate between acknowledgment that is lacking due to their own actions, like loud music for many hours at night, on the one hand, and acknowledgment that is undeservedly lacking, on the other. The former, they can understand: ‘That neighbor has often stood at the door and the neighbor was then seen as a nagging person. And at the same time I think, yes, if you turn on the music at twelve o’clock in the night’. The latter shows a painful counterproductivity of living with Cura, when employers decline an applicant from this address, that is known as a facility for people with disabilities.

The wishes to belong, to fit in, to participate, and to be acknowledged, have been expressed many times, and indicate needs that require a special effort from the municipality and the Cura organization. However, the trajectories have put us also on the track of the ‘life-sustaining web’ that is central to the care ethics theory of Tronto. When we look again at what needs the participants have expressed and what matters to them, we see that this web contains large gaps. It appears that by putting this web central, we can look at the larger socio-political context which is determined by national policies which in turn limit the options of the municipality and the organization. This means that part of the needs of the participants cannot be met by either party (municipality and organization), as they lie on a level beyond their control. To this we turn in the next section.

Meta-analysis of the ‘life-sustaining web’

The aim of this article has been to focus upon the meeting of needs in and by the societal context. Apparently, it seems that the ‘participation society’ of the national policies and the way in which caring for needs is organized in the neighborhood, do not contribute to a ‘caring society’. The participants try their best and are committed to develop themselves in order to become more self-reliant, but they also fight an uphill battle, facing challenges on a daily level. Living away from their personal networks, with too limited means to meet them, and having an insufficient social network of peers in the vicinity to help them to go exercising or go out for a break from their busy, loud living environment, makes them miss out on things that they need.

In other words, their life sustaining web thus shows a significant gap, that indicates a lack of social contacts in the vicinity of their home. This gap has a spatial dimension; a gap between important contacts within the group home, primarily with supervisors, and important contacts at a distance, primarily with family and friends, and apparently not many contacts of any significance in the neighborhood. But the gap also has a temporal dimension. Over time, the participants have moved from one caring context to another and they are not rooted here, nor is there much familiarity with others inside or outside the home. What is more, their living here appears to be instrumental: they primarily live here to be supported in developing capabilities required for a more independent living. Hence their stay is temporary. With these aims they show themselves adapted to a society that not only expects them to do this, but also presumes a willingness to sacrifice a lot in order to reach this.

We wonder, however, if this does not make the participants more vulnerable. As we have seen, they see themselves faced with an uphill battle in a facility that is even counterproductive to their aims. Departing from the fifth phase of Tronto’s model, we can argue more substantially, that the geographical and temporal gap in their life-sustaining web is a gap of solidarity. Tronto’s fifth phase points at caring as a collective responsibility of a democratic society, based on solidarity and trust (Tronto Citation2013). According to Tronto caring practices may enable people to develop a sensitivity for the role that care plays in society. If such sensitivity develops and people are acknowledged in their vulnerability and dependency, more consistent, collective, reliable care provisions can be created.

Most policies regarding care however, appear not to be rooted in a sensitivity to care needs, but rather in ideals of independence and self-reliance. As a result, care organizations and their personnel need to do the impossible: reconcile the goals of government policies that hardly suit the goals of their organizations or those of their care receivers. The top-down determined goals also prevent the availability of sufficient means. Here we see why care ethics also functions as a critique of political ideology: if we do not look at the societal dimension of how care is organized and how needs are determined by those in power, we run the risk of blaming those who seek to provide care for those in need for their failures, without an eye for the tension within which they operate. We can conclude that those involved in the care provision of this particular location (Cura), act in solidarity with the participants, but are in turn dependent upon those in power who determine the available resources.

This also leads to a critical assessment of Tronto’s work on two points. First, Vosman and Niemeijer (Citation2017) point at an inconsistency where Tronto (Citation2013) suggests that in order to societally organize democracy as more caring, ‘a counter image or story against neoliberal versions of caring’ needs to be construed (Vosman and Niemeijer Citation2017). Rather than such a counter image, Vosman and Niemeijer underscore that the ethos (i.e. practiced morality) by practitioners should remain leading, together with efforts to remove institutional barriers put in place by late-modern ideas:

In the end it would be normatively more fruitful if we were able to enlarge the space for reflection, together with partakers in a practice, including the dismantling of modern elements which in fact constrain the reflection of the practitioners and do not serve them well after all. (Vosman and Niemeijer Citation2017).

A second critical assessment of Tronto’s work, and care ethics more broadly, is made by Vosman, Timmerman, and Baart (Citation2018), who state that one of care ethics’ major flaws is its lack of empirical underpinnings, as well as its ‘lack of consciousness on how to dig into practices in such a way that participants and their actual concerns in that practice are acknowledged (and not their imagined position, “needs,” etc.)’ (Vosman, Timmerman, and Baart Citation2018, 408). This present contribution aims to fill both lacks. On the one hand, we have aimed to find multiple ways to acknowledge participants and their actual concerns and concrete needs, rather than their imagined positions or abstract needs. On the other hand, we consider this research a critical touchstone for the theory of living in a ‘life-sustaining web’. We conclude that this metaphor (‘web’) is helpful in a concrete way, that is: to visualize a real-life problem of distance leading to broken relations and a lack of care. As such, this research affirms the theory, and offers empirical support.

Limitations

Care ethics puts relationality central to care, but also to ethics and to its research approach. This project was therefore designed as participatory research, utilizing methods suitable for participation, and in line with critical insights from care ethics. Still, it was often very hard to factually have the participants participate. ‘Nothing about us without us’, has been a justified demand expressed by people with disabilities. Research agendas and programs from the Dutch health care funding organization ZonMW explicitly acknowledge this demand and so did the researchers involved in this project. Everyone agreed upon the importance of having youths with MID express their own needs and their own wishes concerning care. However, as Löve, Traustadóttir and Rice (Citation2018) point out, we also need to recognize that ‘society’s structures and norms are a reflection of existing power relations, created and defined by dominant groups and which serve to maintain the status quo…[as] ridding society of institutionalized domination and oppression is pivotal to achieving justice for marginalized groups’.

Here we see that the researchers, as well as the funding organization, have fallen into the trap for which Tronto has warned, viz. the presupposition that all citizens are capable of articulating their needs, of organizing their lives and care, and of defending their interests. Based upon this research we cannot and will not conclude that youths with MID are incapable to do so. But we can raise the question whether this kind of participatory research offers the possibilities she claims to offer for these participants. For this, additional research is required.

Conclusion

This research project resulted directly from the problems indicated by the municipality and the Cura organization. Both parties lacked insight into the needs and wishes of the youths and young adults with MID living in the facility and how institutions could cooperate to meet these needs and improve participation in the neighborhood. A participatory design was set up because the basic assumption was that participants needed to be involved as research partners in which they had a say, a voice that was actually listened to. The aims were to gather knowledge of their experiences, of what was of importance to them, and what care and support they needed to live ‘as well as possible’ in this neighborhood.

We conclude that when looking at the care practice in this particular facility through a lens of care, the life-sustaining web of the participants appears to suffer from painful gaps. This has become most clear when looking at the trajectories in which the participants’ photos of meaningful things and places were placed: these were either located in the facility itself, of at a large distance from it. On the other hand, certain needs of the participants were met, particularly some on the individual level of self-development. However, from a care ethics perspective, questions emerge concerning the displacement of participants from familiar settings to this facility on the one hand, and the lack of initiatives such as supporting activities in the neighborhood on the other hand. It seems plausible that the challenges that the participants face are rooted in the political and institutional policies rather than in the needs of the participants.

We therefore strongly recommend a care ethics approach as a point of departure for care policy and organizing care. Having a safe and supporting caring web of relations in place, and sustaining it rather than tearing this down, should be an important aim of those policies and organizations. Finding employment is an indismissable part of such a web. Further, these trajectories could serve as a means for communication. It gives expression to the experiences and needs of the participants, and many are involved in meeting their needs: supervisors, other employees, the organization and the municipality. They all should engage in the cyclical process of care, in order to organize care in a caring way, by sustaining the web of relations. A subsequent research project that could complete the Responsive Evaluation by taking up the next steps (3 to 5) is desirable. This would allow the participants to co-design an agenda for further research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abma, T. A. 2006. “Werken met narratieven: Verhalen en dialoog als methoden voor praktijkverbeteringen [Working with Narratives: Stories and Dialogue as Methods for Improving Practices].” Tijdschrift M&O 60 (3-4): 71–84.

- Abma, T. A., and R. Stake. 2001. “Stake’s Responsive Evaluation: Core Ideas and Evolution.” New Directions for Evaluation 2001 (92): 7–22. doi:10.1002/ev.31.

- Abma, T. A., and G. A. M. Widdershoven. 2006. Responsieve methodologie: Interactief onderzoek in de praktijk [Responsive Methodology: Interactive Research in Practice]. Den Haag: Lemma.

- Creswell, J. W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

- Dutch Coalition for Disability and Development (DCDD). 2016. Hoe Inclusie sociale en economische ontwikkeling verbetert. Amsterdam: DCDD.

- Eadens, D. M., A. Cranston-Gingras, E. Dupoux, and D. W. Eadens. 2016. “Police Officer Perspectives on Intellectual Disability.” Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 39 (1): 222–235. doi:10.1108/PIJPSM-03-2015-0039.

- Geertz, C. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: New York Basic Books.

- Hergenrather, K. C., S. D. Rhodes, C. A. Cowan, G. Bardhoshi, and S. Pula. 2009. “Photovoice as Community-Based Participatory Research: A Qualitative Review.” American Journal of Health Behavior 33 (6): 686–698. doi:10.5993/ajhb.33.6.6.

- Jurkowski, J. M., and A. Paul-Ward. 2007. “Photovoice with Vulnerable Populations: Addressing Disparities in Health Promotion among People with Intellectual Disabilities.” Health Promotion Practice 8 (4): 358–365. doi:10.1177/1524839906292181.

- Kroneman, M., W. Boerma, M. Van den Berg, P. Groenewegen, J. de Jong, and E. Van Ginneken. 2016. Netherlands: Health System Review. Health System in Transition. Utrecht: Nivel.

- Leget, C., I. van Nistelrooij, and M. Visse. 2017 “Beyond Demarcation: Care Ethics as an Interdisciplinary Field of Inquiry.” Nursing Ethics 26 (1): 17–25. doi:10.1177/0969733017707008.

- Löve, L., R. Traustadóttir, and J. G. Rice. 2018. “Trading autonomy for Services: Perceptions of Users and Providers of Services for Disabled People in Iceland”. Alter - European Journal of Disability Research, Revue Européen De Recherche Sur Le Handicap 12(4): 193–207.

- Meininger, H. 2013. “Inclusion as Heterotopia: Spaces of Encounter between People with and without Intellectual Disability.” Journal of Social Inclusion 4 (1): 24–44. doi:10.36251/josi.61.

- Moonen, X. H. M. 2017. (H)erkennen en waarderen: Over het (h) erkennen van de noden mensen met licht verstandelijke beperkingen en het bieden van passende ondersteuning. Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam.

- Mykitiuk, R., A. Chaplick, C. and Rice, C. 2015. “Beyond Normative Ethics: Ethics of Arts-based Disability Research”. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health 1 (3): 373–382.

- Novak, A. A., R. J. Stancliffe, M. McCarron, and P. McCallion. 2013. “Social Inclusion and Community Participation of Individuals with Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities.” Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 51 (5): 360–375. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-51.5.360.

- Overmars-Marx, T., B. Pepping, and F. Thomése. 2018. “Living Apart (or) Together-Neighbours’ Views and Experiences on Their Relationships with Neighbours with and without Intellectual Disabilities.” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID 31 (6): 1008–1020. doi:10.1111/jar.12455.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. London: Sage Publications.

- Richards, M., R. Lawthom, and K. Runswick-Cole. 2019. “Community-Based Arts Research for People with Learning Disabilities: Challenging Misconceptions about Learning Disabilities.” Disability & Society 34 (2): 204–227. doi:10.1080/09687599.2018.1522243.

- Rogers, C. (2016). Intellectual Disability and Being Human: A Care Ethics Model. New York: Routledge.

- Simpson, P., and M. Richards. 2018. “Using Photovoice with Working-Class Men: Affordances, Contradictions and Limits to Reflexivity.” Qualitative Research in Psychology: 1–21. (Published online: 12 December 2018) doi:10.1080/14780887.2018.1549298.

- Smulders, N. B. M., I. G. Driesen, T. Van Regenmortel, and M. J. D. Schalk. 2016. Passende zorg in de sociale wijkteams: Een onderzoek naar toeleiding naar zorg in de sociale wijkteams in de Gemeente Nijmegen [Suitable Care in social Neighborhood Teams in the Municipality of Nijmegen]. Tilburg: Tranzo, Tilburg University.

- Tronto, J. C. 1993. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York: New York.

- Tronto, J. C. 2013. Caring Democracy: Markets, Equality, and Justice. New York: New York University.

- Van der Meide, J. W. 2015. “Why Frailty Needs Vulnerability: A Care Ethical Study into the Lived Experiences of Older Hospital Patients.” PhD Diss., Tilburg University.

- Van der Meide, J. W., and G. Olthuis. 2012. “Geraakt worden door verveling. Over shadowing in een fenomenologisch onderzoek naar de ervaringen van oudere patiënten in het ziekenhuis [Being Affected by Boredom. On Shadwing in Phenomenological Research into the Experiences of Older Patients in Hospital].” Kwalon 17 (2): 41–46.

- Van Nistelrooij, I., P. Schaafsma, and J. C. Tronto. 2014. “Ricoeur and the Ethics of Care.” Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy 17 (4): 485–491. doi:10.1007/s11019-014-9595-4.

- Verdonschot, M. M. L., L. P. De Witte, E. Reichrath, W. H. E. Buntinx, and L. M. G. Curfs. 2009. “Community Participation of People with an Intellectual Disability: A Review of Empirical Findings.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR 53 (4): 303–318. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01144.x.

- Visse, M. A., G. A. M. Widdershoven, and T. A. Abma. (2011). “Moral Learning in an Integrated Social and Healthcare Service Network.” Health Care Analysis, 20: 281–296. doi:10.1007/s10728-011-0187-7.

- Vosman, F., and A. Niemeijer. 2017. “Rethinking Critical Reflection on Care: Late Modern Uncertainty and the Implications for Care Ethics.” Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy 20 (4): 465–476. doi:10.1007/s11019-017-9766-1.

- Vosman, F., G. Timmerman, and A. Baart. 2018. “Digging into Care Practices: The Confrontation of Care Ethics with Qualitative Empirical and Theoretical Developments in the Low Countries, 2007-17.” International Journal of Care and Caring 2 (3): 405–423. doi:10.1332/239788218X15321005652967.

- Werner, S., and M. Stawski. 2012. “Mental Health: Knowledge, Attitudes and Training of Professionals on Dual Diagnosis of Intellectual Disability and Psychiatric Disorder.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR 56 (3): 291–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01429

- Woelders, S., and T. A. Abma. 2015. “A Different Light on Normalization: Critical Theory and Responsive Evaluation Studying Social Justice in Participation Practices”. New Directions for Evaluation 146: 9–18.

- Zon M. W. 2020. Accessed 16 November 2020. https://www.zonmw.nl/en/about-zonmw/organisation/