Abstract

Physical access to food is frequently studied using universal measures, like distance to stores, excluding experiences of people who move or travel differently, like disabled people who choose to use mobility aids. Aiming to understand disabling experiences of food access, mobile interviews were conducted with 23 disabled adults who use mobility aids and/or experienced physical barriers to mobility. This study uses a critical ableist studies perspective, looking beyond the effect of the ‘disabled body’ and focuses on relational distances to food, including physical, economic, and social resources that could lead to pathways of disablement. Results highlight intersecting disabling barriers to food access, including socioeconomic barriers and physical barriers within the home, neighbourhoods, transportation, and food destinations and temporal inaccessibility due to construction and inclement weather. These findings suggest the importance of improving and enforcing accessibility standards in public and private places in coordination with addressing socioeconomic disadvantage of disabled people.

Disabled people experience greater risk of food insecurity.

Food insecurity for disabled people could be reduced with increased incomes from disability income sources or through a basic income supplement.

Physical barriers to mobility were located within the home, neighbourhoods, transport systems, and food destinations. Limited income often resulted in greater physical barriers to food access (e.g., inadequate housing or transportation) and reduced ability to overcome physical mobility barriers.

Disruptions related to construction, weather, or mechanical breakdowns resulted in risks to safety and uncertain food access.

Points of interest

Introduction

Research in the United States and Canada indicates that disabled people experience greater risk of food insecurity, defined as the inability to access food because of financial constraints (Coleman-Jensen and Nord Citation2013; Gundersen and Ziliak Citation2018; Borowko Citation2008; Schwartz, Tarasuk, et al. Citation2019). Food insecurity is associated with chronic conditions (e.g. diabetes, cardiovascular disease), mental illness, and increased mortality (Vozoris and Tarasuk Citation2003; Gundersen and Ziliak Citation2015). Health effects go beyond impacts of poor diets and nutrition and include experiences of stress or lacking control over basic needs (Tarasuk Citation2016). Explanations for the disability-food insecurity link include reduced financial resources and high household expenses related to disability, such as equipment, care, and medical needs (Huang, Guo, and Kim Citation2010; She and Livermore Citation2007). ‘Physical limitations on mobility’ (Heflin, Altman, and Rodriguez Citation2019, 221) are also discussed as a barrier to food security because of assumed reduced ability to procure or prepare food (Wolfe, Frongillo, and Valois Citation2003; Heflin, Altman, and Rodriguez Citation2019). Yet, experiences of food access (physical and economic) among disabled people remains poorly understood (Schwartz, Buliung, and Wilson Citation2019; Shaw Citation2006; Webber, Sobal, and Dollahite Citation2007).

A critical ableist studies (CAS) approach is used in this work to theorize disability within food access systems (Goodley Citation2014). This approach has its foundation in the social model, where ‘disability’ is understood as a social rather than medical or bodily problem (Oliver Citation1996; Goodley et al. Citation2019). The social model defines disability as resulting from social barriers, including social discrimination operating individually and institutionally, and adverse built environments, which may exclude people from wider social participation. Building on the social model, a CAS approach considers bodily experiences of difference and questions not just disability, but ‘ability’, or the ableist social organizations and structures that privilege so-called ‘able’ bodies. This ‘system of ableism’ produces exclusionary socio-temporal organization of everyday life. For example, environments and normative social orderings in many modern cities conform to the needs of ‘typical’ or ‘able’ bodies, assuming flexible and independent mobility while excluding people who do not meet these expectations (Goodley Citation2014; Hahn Citation1986).

Throughout this article we make use of identity-first language (i.e. disabled person(s)), while acknowledging debate and diversity in the representation of disability in both academic and public discourse (Peers, Spencer-Cavaliere, and Eales Citation2014). As an example of this debate, within the context of this work, our community research partner, the Centre for Independent Living in Toronto (CILT) and many of our participants used person-first descriptors (i.e. person with a disability) (CILT Citation2019). We did not explore representation and identity in depth with our partner organization or participants and so are unable to write about the nuanced and often deeply personal choices about how one describes oneself. In our work, we explored access barriers among persons who used some kind of a mobility aid to assist with their daily independent mobility or described barriers to mobility present in their surrounding environment and so in the remainder of the paper, when we refer to disabled people, we are specifically focused on people who experience mobility barriers and/or use various technologies/devices to help them move their bodies in the way they want to move them.

Food access and disability

Physical access to food is often considered using technical measures, like distance to stores or ‘walkable’ neighbourhoods (Walker, Keane, and Burke Citation2010; Caspi et al. Citation2012). When disability is considered in this research, it is generally conceptualized as an impediment to access, increasing the likelihood of experiencing barriers (e.g. difficulty walking shorter distances to a store), thereby focusing access on the disabled body (Whelan et al. Citation2002; Shaw Citation2006). These conceptions of access ignore other affective and physical responses like pain and frustration during travel, disabling barriers, and how people react to environments in ways that are unique and tied to past experiences (Andrews et al. Citation2012). When disability has been incorporated into understandings of walkability, or ‘wheelability’, perceived accessibility and features, like curb cuts are shown as important (Mahmood et al. Citation2020), indicating a need to expand understandings of access. Mobility and social participation among disabled people are found to be greatly limited by inaccessibility of outdoor environments, public buildings, and the home (Bigonnesse et al. Citation2018). Though mobility assistive devices can increase the autonomy of many disabled people, this depends on the availability of accessible places that permit their use (Korotchenko and Hurd-Clark 2014). Disabling barriers specifically, during trips to food sources have been reported. Examples of these barriers include steep topography, cracks in sidewalks, and food stores lacking features like accessible parking, entrances, or washrooms (Shaw Citation2006; Chung et al. Citation2012; Huang et al. Citation2012; Mojtahedi et al. Citation2008). How such barriers contribute to food insecurity for disabled people is unknown. Disabled people could overcome physical access barriers, like distance, through material and social resources, including access to help, and by possessing the ability to afford public and private forms of transportation (Coveney and O’Dwyer 2009; Wolfe et al. Citation1996). Yet, physical disability could intersect with limited material and social resources and severely limit access to food (Webber, Sobal, and Dollahite Citation2007), particularly as disability is widely associated with poverty and more limited social resources (Palmer Citation2011; Barnes and Sheldon Citation2010). Food access may be particularly difficult for those without access to proper housing or accessible transportation, living in places with fewer accessible features and stores, or without the means to overcome environmental barriers, requiring examination of barriers at the intersection of poverty and disability.

This study examines food access experiences among working-age disabled adults in the City of Toronto, Canada. A CAS perspective is used to investigate disabling inequalities in food systems. We aimed to look beyond the effect of the ‘disabled body’ or oversimplified measures of access, instead focusing on relational distances to food among disabled adults, including important interconnections between physical, economic, and social resources that could lead to pathways of disablement (Cummins et al. Citation2007). This research is part of a broader project which examines experiences of food access and insecurity among disabled people in the City of Toronto and across Canada (Schwartz, Tarasuk, et al. Citation2019; Schwartz, Buliung, and Wilson Citation2019).

Methods

Semi-structured mobile interviews were conducted with 23 disabled adults who use mobility aids or experience physical barriers to their mobility. Working-age adults (age 18–65) living independently (i.e. outside a community facility) in Toronto were eligible for participation, focusing on those at greater risk of food insecurity and more likely responsible for household food access (Tarasuk, Mitchell, and Dachner Citation2016). Two participants over 65 were included in pilot interviews and the analysis due to their relevant experience. Eight participants, recruited through CILT, were included in a first wave of interviews conducted between November 2017–February 2018. Fifteen participants were recruited from four additional disability or food advocacy organizations across the city in a second wave, with interviews conducted from April to September 2018. A further wave of recruitment was not pursued as participants represented a diversity of disability experiences and a good cross-section of Toronto neighbourhoods.

Participants completed a questionnaire, followed by a semi-structured static interview on barriers to access food (economic, social, physical), and an optional mobile interview. The questionnaire collected sociodemographic information and included the validated, 10-item adult household food insecurity survey module, with Canadian thresholds to determine severity (Health Canada Citation2007). Mobile interviews consisted of a go-along interview, during which the interviewer (NS) accompanied the participant on a typical food access journey (generally to and from a grocery store) or if preferred, a mental mapping exercise, where the participant created a ‘life-space map’, or drawing, of their local food environment (Huot and Laliberte Rudman Citation2015). Mobile methods can elucidate relational understandings of mobility in every-day routines, allowing participants to emphasize features that are important to them and encourage reflection and reactions tied to place (Matthews and Vujakovic Citation1995; Kusenbach Citation2003; Carpiano Citation2009). Of the 23 participants, 18 participated in go-along interviews, four in life-space mapping, and one completed a static interview alone. The questionnaire and/or mapping exercise was completed by participants or the interviewer at the participants’ direction. For go-along interviews, participants chose the food destination, the route, and travel mode. Participants were compensated according to interview type. Go-along interviews involved the highest compensation at $30 (CAN) due to its longer time commitment and travel was reimbursed according to the cost of public transportation.

Interviews were recorded with participants’ permission, and were transcribed, and coded using NVIVO 12. Thematic analysis was used to identify emergent themes, using iterative coding to identify overarching themes and insights and to group results. Routes and life-space maps were compared and linked to emergent themes in interviews. All participants were given pseudonyms to protect their identity. Ethics was granted from the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board and was approved by CILT.

Geographical context

Toronto, Ontario is the largest city in Canada, with a population of 2.7 million (Statistics Canada Citation2019). The City of Toronto is diverse in its neighbourhood design, including a densely populated downtown core/commercial centre, central-Toronto with housing and transport typical of Canada’s early (pre-World War II) suburban neighbourhoods, and inner-suburbs, with less dense, automobile-dependent growth. Food insecurity is reported in 13.6% of Toronto households, comparable to a provincial rate of 13.3% (Tarasuk and Mitchell Citation2020). Toronto has costly housing which has sharply increased in recent years (CANCEA Citation2018). The Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) offers Wheel-Trans, a paratransit service, which includes door-to-door transportation for disabled residents at the cost of standard public transit fare. The City also has planning goals focused on improving neighbourhood and transit (station and vehicle) accessibility (City of Toronto Citation2020a, Citation2020b; TTC 2017).

Policy environment

Ontario’s social assistance program for disabled people, known as the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP), offers higher payments compared to the general welfare system. Benefits are distributed with a requirement to prove financial need and presence of a long-term disability (Government of Ontario Citation2018). Maximum benefits for a single person on ODSP equalled $14,954 (CAD) in 2018, lower than Toronto market-based measures of poverty ($21,207 CAD) (Maytree Citation2019). In 2005, the province adopted the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA), mandating that organizations in the public and private sector follow certain accessible standards, with a goal to achieve ‘full’ accessibility by 2025 (Government of Ontario Citation2015).

Participant profiles

Participant characteristics were self-reported in questionnaires. Participants ranged in age, with the majority being over age 50 (74%, n = 17), and gender with most identifying as female (61%, n = 14) and one participant identifying as a transgender male. The most common primary mobility devices used were walkers (n = 9), and wheelchairs (n = 7). Most participants were socioeconomically disadvantaged, with 14 (61%) reporting food-insecurity, including seven (30%) with severe food insecurity. Sixteen (70%) identified the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) as their primary source of income. Others identified employment, Old Age Security, the Canada Pension Plan for disability, savings/dividends, or private disability insurance as their primary income sources. Most participants lived alone (74%, n = 17) and all but four were primarily responsible for acquiring household food; these four either shared responsibilities or supplemented household access. Participants were primarily white (83%, n = 19). Seven participants were recruited from downtown neighbourhoods, eight from central Toronto, outside the downtown core, and eight from inner suburban neighbourhoods.

Results

Disabled participants experienced barriers to food access on various fronts. These barriers included economic barriers that prevented people from affording food, physical access barriers that made it more difficult to acquire, prepare, or eat food, and social barriers that denied needed supports. Barriers occurred when food access systems failed to meet the needs of disabled people. These barriers were experienced at multiple levels outlined below, including the state/provincial level, informing policy and practices around social assistance, within the home, on the way to food destinations, and within food destinations.

State-level barriers (social assistance)

Of the 12 participants experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity, 11 identified economic barriers as majorly limiting food access. This was mostly due to inadequate incomes from social assistance programs like the provincial ODSP and the national Canada Pension Plan-Disability (CPP), in addition to self-reported inability to ‘work’ or gain full employment because of a disability. Of those receiving their primary income from ODSP or CPP, 65% (11 of 17) were food insecure, similar to proportions among Canadians on social assistance (Tarasuk and Mitchell Citation2020). Low incomes from state-level sources or other disability pensions often outweighed all other food access concerns, as Richard described.

Richard: If I… had the assistance with the food shopping… that would be fantastic. But at the end of the day… what it really boils down to, especially for those who are on some form of assistance or fixed income, it comes down to dollars and cents.

-50s, severely-food-insecure, walker-user, downtown

Richard, receiving ODSP, noted that his income was too low to afford quality food. Though food shopping was difficult, he described this as separate and unrelated to food security. Limited budgets also made it difficult to afford special diets needed for health. Programs were sometimes available from social assistance sources to supplement extra expenses related to disability (e.g. medical, dietary, mobility devices). A special dietary allowance accessed by a few participants, supplemented benefits for people with medical dietary restrictions on ODSP. Yet these benefits were sometimes described as inadequate or were unknown to participants who could qualify.

Physical barriers, referring to barriers that prevented food access in leaving or returning home, during trips, and within food sources/destinations, may be described separately from economic barriers, yet physical and economic barriers are often highly interrelated. For example, all participants experiencing severe food insecurity (n = 7) reported both important economic and physical barriers that prevented food access, highlighting the multiple barriers faced by the most disadvantaged. Limited budgets affected people’s daily food access experiences and ability to overcome barriers. People with very limited economic resources often had the least control over their physical environment, including living in unsuitable housing, inability to afford proper care or transportation, lack of choice in neighbourhood of residence, and limited choice in food destinations.

Barriers within the home

The home was the most immediate place from which food was accessed; meaning barriers within the home were particularly salient. One participant lived in a single detached home, while the rest lived-in high-rise apartments (n = 17), low rise apartments (n = 4), or shared group homes (n = 1). Barriers were experienced within the personal space of the home but also in common or shared spaces for those in apartment buildings.

Barriers within personal spaces included small sized units that do not properly fit mobility devices, high shelves, inaccessible sinks, and narrow passageways, making activities like food preparation or moving comfortably within the home more difficult. Amanda described difficulties moving around her small market-rent apartment.

Amanda: At home, I don’t use anything (mobility device), I just hang onto the walls, but now I’m literally hugging the walls, and like, walking like a snail pace… So, my upper body is incredibly strong… but like balance, strength, flexibility, all those things are not up to par because of disabilities… The reason I do it in my house (ambulate) is because my house is not accessible, I live in a shoebox (laughs). There’s no turning radius.

-30s, marginally-food-insecure, manual-wheelchair-user, downtown

Because of limited income or restrictions of subsidized housing, participants, like Amanda, lived in inadequately sized apartments that did not properly fit them with their mobility device. This led to stress and risks to safety. Some participants, including Amanda, also recounted dangers of cooking in inaccessible kitchens, while some avoided cooking altogether because of perceived dangers.

Barriers in shared spaces included heavy doors, a lack of accessible door openers, and uncleared or unsafe ramps in front of apartment building or houses. Because most participants lived in apartments, particularly high-rise units, many feared that elevators would break down or dealt with slow elevators with long wait times. Breakdowns affected people’s ability to leave home or could force some to take risks, like walking up stairs. Certain participants’ apartment buildings permitted entrance or exit but were not fully accessible, for example, where front door entrances or lobbies were inaccessible and disabled people were accommodated through backdoor or side entrances. Backdoor accommodations, already exclusionary, separating disabled people from regular access points (Imrie and Kumar Citation1998), may have additional negative consequences. Many participants wait in front lobbies to detect the arrival of their rides from Toronto’s paratransit system, Wheel-Trans, which can arrive within 30 min of booking times and sometimes takes longer. Two participants with inaccessible front-door lobbies reported waiting outside their building to detect the arrival of their ride, sometimes waiting up to 30 min in freezing temperatures, with potentially important risks to safety.

During adverse weather events, construction, or mechanical breakdowns of elevators or mobility devices, people may be limited to the home, severely restricting access to food. Material or social resources affected whether participants could overcome physical access barriers within the home.

Cynthia: Remember the ice storm we had, in April? I stayed home, yeah, that’s when I didn’t have food… The worst, probably the worst… I would have to order, and they deliver…

Interviewer: from one of the grocery delivery services?

Cynthia: Oh well, you know, like Swiss Chalet or Pizza Pizza (laughs). Yeah, if I have to, like I don’t want to starve… If I have the money. If I don’t then I just wait until the next day and drink a glass of water.

-50s, severely-food-insecure, walker-user, downtown

Cynthia experienced a severe situation during a spring ice storm when her options were either getting food delivered, if she had the money, or coping with severe hunger. Spending on fast food delivery was sometimes possible during emergencies because it required less cash on hand compared to grocery delivery. If living with others, other household members often took over shopping during difficult times. Alternatively, those living alone mostly reported difficulty getting help.

Travel to food destinations

Variation in transport and mobility experience, the capabilities of available transport modes, and the role of disabling barriers along the way impacted physical access to food destinations. Embodied experiences highlight common challenges accessing food among disabled people. Brian reported on a discussion with a family-member over his limited ability to travel alone to a discount supermarket within a kilometre of his home.

Brian: he basically thought, ‘oh Brian you can go to Food Basics anytime you want. It’s very convenient’. And I said ‘Yes, but you’re able-bodied, you can handle the wind and the weather, with me and my walker, there’s times… if the wind is strong, the wind will blow me off course and I have no one to help me… So, the average person, they’ll say it’s no big deal, but for me it is.

-30s, moderately-food-insecure, walker-user, inner-suburbs

Brian described how distances, commonly thought of as close, as considered here by a member of his family, are more difficult for him to travel. Barriers to travel were also interrelated with other circumstances, like mobility device, weather, and having someone with whom to travel. Alternatively, some participants did not have trouble acquiring food alone.

Robert: …I have the best shopping vehicle around that can carry all my groceries, and I can do what a normal person can do in a third of the time with my scooter. Going there and coming back and going in a store… Cuz it’s such a big store, right? …I’m able to even pick up all my tin cans and stack them on the bottom of the base of the scooter and carry them. Now, how would I normally, bring them home and do all that?

-60s, food-secure, scooter-user, downtown

Participants like Robert, with electric mobility devices, frequently travelled long distances and transported heavy groceries home, even in snowy or icy conditions. However, other restrictions could arise when encountering barriers, including reduced ability to traverse narrow spaces, adjust to disruptions (e.g. broken-down elevators), or getting stuck. Two participants also described rejecting use of these devices for a time because of perceived stigma related to disability or aging.

Barriers in outdoor environments were frustrating and dangerous. These barriers were also experienced relationally, rooted in familiarity with local neighbourhoods, like knowledge of accessible washrooms. Participants frequently discussed barriers, like old inaccessible buildings, and crowded routes in downtown and central-Toronto and more commonly discussed features like wide, dangerous intersections in the suburbs. For many participants, city streets, built to prioritize motor vehicles, could be difficult to traverse. Rana [60s, moderately-food-insecure, walker-user, inner-suburb] described how her slower walking speed put her at greater risk of being hit. Despite having a grocery store across the street from her suburban residence, for safety, Rana walked far out of the way to cross at a light, more than doubling the time needed to reach a store. People with slower walking speeds have increased risk of pedestrian injury because of greater difficulty crossing intersections within set walk times and difficulty crossing safely between intersections (Avineri, Shinar, and Susilo Citation2012). This relationship could be alleviated with designs that consider the needs of pedestrians, including greater frequency of lights for crossing and longer intersection walk times (Liu and Tung Citation2014; Retting, Ferguson, and McCartt Citation2003). Road designs that do not consider pedestrians can importantly lead to safety risks or long inconvenient detours for disabled people.

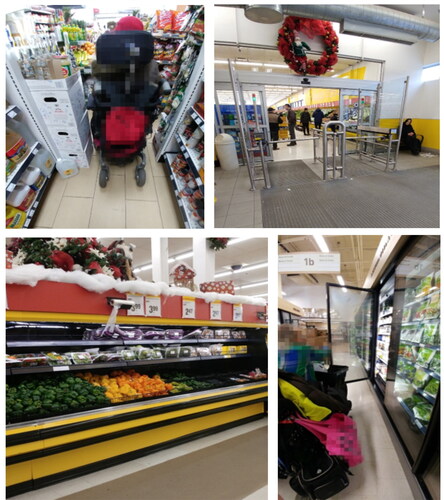

Small-scale barriers could leave people stranded or forced to take risks. Caleb described travelling in his wheelchair along roads or parking lots because of sidewalks that lack a curb cut. He compared his experience to the 1980s videogame ‘frogger’ where a frog is trying to cross a road while avoiding obstacles, including cars. Lisa [60s, food-secure, scooter-user, inner-suburbs] recounted once travelling down a sidewalk, and then discovering there was no curb cut to dismount. To get down, she was made to crash her scooter off the sidewalk. In addition to important risks of bodily injury, these situations could require expensive equipment repairs, not fully covered by disability assistance programs. Where curb cuts existed, they could be temporally inaccessible, blocked by objects like ice and snow. Lisa described how cars would sometimes park in front of curb cuts (see for examples). Small features like bumps, cracks, and gradient toward a road could also make sidewalks difficult to traverse. As Caleb described, these ‘minor things’ add up.

Figure 1. Examples of curb cuts. (a) Curb cuts sometimes blocked by cars, ice, or snow. (b) Curb cut leads nowhere.

Interviewer: are there improvements that can be made that would help you travel more?

Caleb: Well, it’s the minor things… like you can’t really blame anyone for, but you really want to blame somebody for. Like when there’s snow, and the ice, and the fact that the garbage machine… sometimes it drops (the garbage bin) and then it falls down and that blocks my path. I, most of the time, I push it out of the way, but sometimes it’s like, there’s like a gross puddle or something in front and it’s ugh!

-20s, food-secure, power wheelchair-user, inner-suburbs

Caleb cannot anticipate the temporal inaccessibility of sidewalks, making travel difficult. Mahmood et al. (Citation2020) similarly note how temporary obstructions can act as a major mobility barrier, resulting in unanticipated rerouting. These barriers could cause discomfort and negative affect in the moment. Repeated exposure to such negative experiences can accumulate, leading to chronic feelings of stress and uncertainty. Imrie and Kumar (Citation1998) similarly describe how encountering small-scale barriers, can make outside environments seem dangerous and unwelcoming. These environments can be considered disabling, communicating exclusion and difference to disabled people (Kitchin Citation1998).

Accessibility concerns on streets and sidewalks were further complicated by construction, including risks to safety from uneven paths and inconvenient detours. Barbara [60s, marginally-food-insecure, walker-user, central-Toronto] described her fears crossing a major construction site near her home, noting how bumps in the road made it dangerous to get through with her walker. Winter weather also often imposed severe limitations on movement, dramatically shifting access. Sidewalks were not always cleared of snow, even days after snowfall. People using canes, walkers, or manual chairs feared slipping on icy sidewalks. Power chairs could move better than other devices through snow or ice but could also get dangerously stuck in the winter, as Lisa described.

Lisa: one time I went out and I was fine getting to the store, but with the groceries I was sinking in. And somebody that knew me stopped and waited with me because they couldn’t get (me) out either off the sidewalk. So, I put in a call to Wheel-Trans. They stayed with me till they came and helped push it into the Wheel-Trans… It’s tricky cuz you could freeze if something like that happens and you gotta make sure your cell phone’s always charged up.

-60s, food-secure, scooter-user, inner-suburbs

Lisa, fearful of travelling alone, relied on her cell phone in case of emergencies. As seen here, these situations could be life or death. Many participants shopped less in the winter, got help from others, if available, or took different routes, like paths with more foot traffic and therefore, more likely cleared of snow. Participants were more likely to take paid forms of transportation in winter or have food delivered.

Grocery delivery was a potentially helpful supplement to food access but also presented some challenges. Four participants regularly used grocery delivery. Amanda [30s, marginally-food-insecure, manual wheelchair-user, downtown], described how her pregnancy prevented her from reaching or turning easily in her manual wheelchair, which made grocery shopping difficult. She had, therefore, been using grocery delivery services almost exclusively during her pregnancy. For others, having food delivered was sometimes helpful, especially for big orders. However, delivery costs were prohibitive for many. Some delivery services also require a minimum order of $50 (CAD), which many participants did not have on hand, or were from more expensive stores, precluding use, even when desired. Additionally, commercial delivery was not always desired. While delivery may have been affordable for Mike [50s, food-secure, walker-user, inner-suburbs], at times where his mobility is more limited, like in wintertime, he preferred going out, avoiding long periods alone at home. Therefore, while grocery delivery is a useful adaptation strategy for some people, it does not replace the desire to go out and comfortably access food and does not ameliorate an obvious disability-related inequality regarding travel options for food.

Travelling by paratransit

Wheel-Trans, Toronto’s paratransit service, offers door to door service for qualifying disabled adults at the cost of general public transit. Wheel-Trans was the most common mode for food shopping, used regularly by 65% of participants (n = 15), while only three had access to a personal motor vehicle (excluding wheelchairs or scooters). For many, Wheel-Trans was a necessity, without which they could not get around. Participants found the service to be generally safe and noted the importance and convenience of door-to-door service, enabling travelling longer distances, especially in winter. However, relying on Wheel-Trans for food access presented many challenges. The cost of transit was expensive for many, particularly for a monthly transit pass (metropass) costing $146.25 (CAD) for adults during the study period with a one-time trip costing 3$(CAD) (TTC Citation2019). Yet, for some with very limited mobility, a monthly pass was also a necessity.

Julie: I buy a metropass, which is, that’s a big chunk of my monthly …basic needs that they give me. But, you know, I have to. I can only walk from here, up to the corner and that’s all I can do… so I really have to have a metropass if I’m gonna go anywhere… so, forever I just buy a metropass, and I just kind of, I don’t fucking care (laughs)…but that cuts into my food money.

-50s, severely-food-insecure, walker-user, central-Toronto

Julie prioritized her mobility even though high transportation costs limited her ability to afford food. While Julie could supplement her food from community food programs (accessed by Wheel-Trans) and foodbanks, she could not get around to access food, or for other reasons, without paying for transportation. These priorities reflect common trade-offs many participants had to make around food access.

Participants reported booking their Wheel-Trans schedules up to a week in advance. The closer to the time of travel, the less likely they would be able to book a ride at desired times for trips and return trips. This sometimes meant waiting for hours after an event for a return trip. Brian [30s, moderately-food-insecure, walker-user, inner-suburbs] described his frustrations with the booking system, exclaiming ‘nobody else plans their life seven days in advance.’ For Brian, if an event is cancelled or rescheduled, or a program, like a cooking class he attended, goes long, others who do not rely on Wheel-Trans can flexibly adapt, while he may not be able to make alternative arrangements. Trips anywhere via Wheel-Trans required setting aside large blocks of time and waiting became an important component of participants’ shopping trips. Therefore, many avoiding specialized stores, preferring to shop where they could carry out other errands or get a meal or coffee while they waited. Wheel-Trans can also arrive anytime within a 30-min window of booking and is sometimes later due to delays. Yet, participants reported that if they were over 5-min late, Wheel-Trans would cancel their ride. Missed rides and last-minute cancellations earned system demerit points; four missed rides in a month resulted in suspension of monthly service (TTC Citation2018). Participants expressed fear that their rides would be cancelled if they were late. Charlie discussed the stress and careful time management involved in scheduling sufficient time to shop without missing his ride.

Charlie: …if I’m looking through the shelves and I’m not finding it, and I don’t see someone around to ask, then I get a little bit worried and frustrated that I might get closer to the Wheel-Trans time… I still make the rides, but I just start to feel a bit of pressure if it’s taking longer than I think it should to get the food, to look for it, or even just waiting in the lineup. Sometimes, well sometimes, it might be my fault for not managing the time, but still, I feel the pressure.

-40s, food-secure, manual wheelchair-user, inner-suburbs

Charlie discussed planning to finish his shopping closer to the arrival of his ride as finishing too early meant that his food may spoil or defrost while waiting. Obstacles may come up at multiple points during Charlie’s shopping trip, including long lines or inability to find items or staff, but no matter what, he must make his ride on time.

Barriers at food destinations

In choosing to shop at discount grocery stores, large chain, specialized, or closer stores, or use foodbanks, participants balanced food destination accessibility, travel options, and affordability. Most participants preferred discount stores, generally large chain stores with cheaper products, due to their restricted budgets. Yet, these stores also often lacked features that were helpful for disabled people, like staff helping in the aisles, or included checkouts where people are expected to bag their own groceries. Connor [30s, moderately food-insecure, cane-user, central-Toronto] who bagged his own items during our trip to a discount grocery store joked, ‘here, there’s no service. You’re paying for the discounts right.’ Though, it was sometimes possible to get help above what was offered, this required asking and waiting for help, which for some, induced anxiety.

Large or chain grocery stores were perceived to have more accessible features, like accessible entrances and wider aisles. Users of wheelchairs or scooters often preferred spacious stores with more room to navigate aisles. Yasmin [50s, severely-food-insecure, power wheelchair-user, downtown] shopped in a grocery store close to her downtown apartment with especially narrow aisles (). She described the experience as a ‘nightmare’ and like a game of Jenga, where she is trying to avoid knocking things down. Conversely, Rana, using a walker, described difficulty and exhaustion traversing big stores.

Figure 2. Barriers in grocery stores. (a) Navigating ‘Jenga’ aisles with Yasmin, (b) ‘choppers’ at store entrances. (c) Plastic bags too high for Anna to reach, (d) freezer doors with Sam.

Rana: going for shopping it’s hard because of my, not able to walk in the big mall… so I just pick up a few things and then I’m short… so I’m not able to buy as much as I want.

-60s, moderately-food-insecure, walker-user, inner-suburb

Because Rana is frequently too exhausted to get everything that she needs in one trip, she must make multiple small trips to get what she needs or make do with less food.

Foodbanks, used by four participants, could be a helpful and necessary supplement. However, foodbanks limit visits to once or twice per month and only provide for several days’ worth of food and so were rarely reported as a major food source. Foodbanks were also described as providing low quality food and lacking in fresh options. This was particularly problematic for participants with special dietary needs, including one participant with kidney problems who could not eat canned foods and therefore avoided most foodbanks. Though foodbanks are disproportionately used by disabled people (Foodbanks Canada Citation2019) they are often inaccessible, as Shirley described.

Shirley: Like the Salvation Army one… I had to ask if somebody would carry it down the steps… even though they see you with a cane and you’re limping…

Interviewer: So, you can’t go in with your scooter?

Shirley: No, no (laughs)… and then you try not to bring a cane because you have to carry all these heavy groceries. How you gonna manage with[out] a cane as well? There’s like … the outdoor staircase, the metal ones, then there’s another staircase to go up… Yeah, I manage, but there will be a time where I won’t be able to.

-60s, severely-food-insecure, scooter-user, downtown

Because of shocking inaccessibility of major foodbanks, Shirley took risks like abandoning her mobility equipment outside and climbing or going down stairs with heavy groceries to meet her needs. However, with declining ability, she noted that access at major foodbanks may become unavailable to her.

Participants reported regularly encountered small-scale barriers within various food destinations. A few participants were annoyed by what one participant called ‘choppers’, or gates meant to prevent people from taking carts out of stores (). Yasmin [50s, severely-food-insecure, power wheelchair-user, downtown] stated that these gates would sometimes hit her in the face, while others worried about getting stuck in them. Palettes for loading food, displays, and boxes sometimes blocked people from traversing aisles, particularly when stores were crowded. Many had difficulty reaching items that were on higher shelves. Anna [50s, food-secure, wheelchair-user, central-Toronto] described difficulty reaching high-up plastic produce bags (). Accessing food inside the freezer or refrigerated section, often behind doors, could be challenging. Sam [40s, severely-food-insecure, scooter-user, downtown] had to balance his chair against the door and maneuver to get access to these foods (see ). These small-scale barriers could add up to important frustration and exhaustion, as Anna explained.

Anna: when I first moved to Toronto, I’d pick every single one of these checkouts… But you want to put in self-serve and make the spaces narrower, and I can only go through one in the entire store now and you’re not staffing it. That’s so frustrating! …And everyone says ‘…we’ll get, someone staffing it’ …but you know what? Perhaps I need to run out the door and catch my bus, or perhaps …that checkout also happens to be the 1-8 [item] checkout, but I’m taking 30 items through because it’s all you’ll offer me. And I get the public going (hissing) behind me, right?

-50s, food-secure, power wheelchair-user, central-Toronto

Rather than allowing disability access in all checkout aisles, participants reported being relegated to a single accessible aisle. Having the express checkout aisle as the only operable accessible aisle (e.g. wide enough to fit a wheelchair) was also reported as a source of anxiety when participants had large grocery orders. Though providing an accessible option, and so technically complying with AODA guidelines, this ‘checking boxes’ consideration of accessibility fell short in practice, leading to designs that were functionally inaccessible (e.g. by not staffing checkout aisles) and contributing to feelings of exclusion (Ross and Buliung, Citation2019).

Participants indicated that inconsistent barriers and functional inaccessibility was confusing, leading to uncertainty over when and where to access food. Sam highlighted the every-day difficulties accessing food where disability accessibility is not considered or dealing with temporary inaccessibility due to things like mechanical breakdowns, adverse weather, or failures of disability systems.

Sam: So, it’s like, when I’m working in a system, up until the moment that I’m here at the table, I’m dealing with a lot of barriers… like if the elevator was broken today … then I would have to put in a complaint and decide, am I gonna find another way to get up to the second floor (of the grocery store) or am I gonna just cancel my shopping trip? So, I have to really pace myself in everything I do because, using a wheelchair means I can’t just, like depend on things. I can’t expect all these things to run smoothly… or by the time I get here, I’m tired and I just want to… it’s just, I have to leave ample room for everything I do.

-40s, severely-food-insecure, scooter-user, downtown

As Sam expressed, he must constantly plan for small disruptions and his own fatigue, leading to considerable uncertainty. For Sam, everyday small events add up, affecting whether he will be ‘at the table’, properly participating and able to meet his needs, or whether he will be excluded.

Discussion

Findings from this study highlight food access experiences of disabled adults, the majority having low incomes, in Toronto, Canada. This research contributes to the food insecurity literature by highlighting an important population inequality and examining the intersection of physical and economic access barriers. Most participants emphasised how their limited, fixed incomes resulted in food insecurity. Yet, physical ability, interacting with accessibility barriers in the home, on the way to food sources, and within food sources, complicated access. Though experiences varied, accessing food while disabled frequently involved long waits and inflexible schedules, risks to safety, stress, and uncertainty. Physical access also strongly depended on available resources, including mobility devices, financial means, and access to help. Those with limited financial resources were less able to limit exposure to barriers.

Mobile interviews allowed for a more fulsome understandings of embodied and relational experiences tied to place. While other studies consider accessibility at certain stages of the food access journey (Huang et al. Citation2012; Shaw Citation2006; Wolfe et al. Citation1996), this study produces a more comprehensive understanding, from food preparation, to going out, shopping, and returning with food. Our work further highlights the important compromises to well-being (physical and emotional) when modes of access are stressful and physically exhausting (Bostock Citation2001; Hamelin, Habicht, and Beaudry Citation1999). Like Webber, Sobal, and Dollahite (Citation2007), we highlight intersections between mobility barriers and socioeconomic disadvantage. However, we understood mobility barriers as not solely based in the disabled body but related to treatment of disabled people, including overly restricted budgets for adults on ODSP and regularly encountered barriers that compromised people’s safety and well-being while accessing food. For example, many participants were limited at times from going out, because of barriers like unsafe intersections, un-cleared sidewalks, inadequate transportation systems, or exclusionary design more generally. Among disabled people, important interactions between limited financial means and restrictions on social-spatial movement have been shown previously (Crooks, Citation2004; Dyck, Citation1995). Yet these interactions are rarely emphasized in work considering disabling barriers to food access (Whelan et al. Citation2002; Coveney & O’Dwyer 2009; Shaw Citation2006).

Participants used a variety of mobility devices, were of different ages, and lived in different areas of Toronto, providing a diversity of experiences. However, experiences in Toronto, a large metropolitan area with generally good access to grocery stores (MPI Citation2010) and services like Wheel-Trans available across the city, may not apply to experiences in other place with different mobility services or urban geographies. Participants in this study mostly lived alone and were more likely involved in disability activism, highlighting a unique population. Despite Toronto being a diverse city (Statistics Canada Citation2019), only four participants were non-white due to limitations in recruitment. Therefore, intersectional experiences of race and disability have been missed.

Disabling experiences of food access

Social structures and environments that are built for the average person rather than accounting for difference, exclude people that do not conform to ableist standards (Goodley Citation2014). In the context of the design of many modern cities, adapted for flexible, independent travel, people are assumed to have control over places and timing of access (Urry Citation2004). Yet, the ways that people acquire, travel with, and consume food differs for people with less financial or social resources or reduced physical ability for travel. Inability to take up normative modes of shopping or access, further communicates feelings of ‘otherness’ or difference (Hansen and Philo Citation2007; Pașcalău-Vrabete and Băban Citation2018). Many of the systems used by disabled people to access food operated outside regular modes of access, including ODSP, Wheel-Trans, and public areas and food sources with unpredictable accessibility. Using these alternatives, disabled people were left with greater financial and physical vulnerability, reliant on places that deny functional accessibility in favour of meeting technical requirements, and with the possibility of temporal inaccessibility.

Restrictive budgets limited participants’ food security and physical access to food. Greater incomes could have prevented food insecurity or helped people avoid some physical access barriers, including facilitating paid grocery delivery in times of need or accessing paid forms of transportation, like taxis. Yet, Chouinard and Crooks (Citation2005) describe how ODSP, used by most participants, is purposely inflexible to needs. Under ODSP, clients are responsible for navigating complicated bureaucratic systems while access to funds and programs, like a special dietary allowance, relied on precise definitions of disability and depended on medical practitioners or other professionals for access (Shantz Citation2011; Lightman et al. Citation2009). Though disabled people are seen as the ‘deserving poor’, under this system, they are only seen as deserving of poverty incomes which deny their needs (Chouinard and Crooks Citation2005). Additionally, many environments impose barriers that require financial means to overcome, leading to a greater need to spend for access.

Access barriers arose when environments or disability systems did not meet the needs of the disabled body or mobility devices. Encountering these various access barriers immediately contributed to embodied experiences of physical pain, fear, and exhaustion while accessing food. Over time, these barriers lead to uncertainty and less control over foods accessed. Similar to work produced by other scholars (Korotchenko and Hurd Clark 2014; Pașcalău-Vrabete and Băban Citation2018), we found that participants were reluctant to ask for help or use mobility devices that could improve access due to disability-related stigma, or pressure to act normatively. Because of regularly encountered barriers and limitations of accessible systems, participants were often restricted in both time and space, leading to the labour of reordering daily tasks (Dyck Citation1995). Examples of this reordering included: confining movements to familiar places, building schedules to account for long waits, and limiting shopping to periods of better weather. In public spaces, designation as ‘accessible’ meant that AODA requirements were met. Though the AODA has led to important improvements in accessibility, guidelines were not always enforced and meeting technical requirements did not guarantee functional accessibility (McQuigge Citation2019), meaning participants could not be sure that places labelled as accessible would work for them. For example, the presence of separate disability access, like disability checkout aisles, meant that disabled people were sometimes excluded from regular forms of access, requiring extra work to be recognized and waiting to have their needs met. When places and systems labelled as accessible fail to work as intended or require added physical or emotional labour for their use (e.g. hailing someone to staff the accessible checkout), they signal the limited or marginal acceptance of disabled people in public spaces (Korotchenko and Hurd-Clark 2014; Hansen and Philo Citation2007).

Separate systems like Wheel-Trans frequently involved long waits and disruptions, which could be especially problematic when accessing work or appointments or travelling with perishable groceries. Though a vital service for many participants, difficulties using Wheel-Trans have been well documented, including important delays and difficulties booking rides at needed times (Angus et al. Citation2012; Delaire and Adler Citation2019). Wheel-Trans’s inflexibility and unreliability restricted temporal and physical patterns of food access. In a world of rideshare and bus tracking, disabled people often wait for rides for upwards of 30 min with little ability to track rides or adjust schedules.

Temporal inaccessibility was a major concern. Participants were made to account for numerous possible disruptions in their day, like pain or fatigue, encountering accessibility barriers, adverse weather events, mechanical breakdowns, construction, or disruptions to Wheel-Trans. For example, when elevators broke down, there was rarely an alternative option. Adverse weather, including build-up of snow or ice was an important and consistent barrier to food access, temporarily limiting when people could leave home. Though inclement weather cannot be avoided, processes like snow removal reflect political decisions. In Toronto, the city is not always responsible for snow removal on sidewalks, which is often left to individual homeowners or building managers (City of Toronto Citation2020a, Citation2020b) but is responsible for clearing all the streets. This leaves many sidewalks icy and impassable for disabled adults or with major fears for their safety when going out, a reflection of the prioritizing of the so-called ‘able-bodied’ during periods of challenging weather and at other times.

Practical implications

Food access for disabled adults could be improved with greater incomes to afford food. Higher incomes would also help to remove physical mobility barriers to food access, including enabling accessibility adaptations to homes, or access to alternative transportation or food delivery in times of need. This suggests needed increases in ODSP, or alternatively, solutions like a basic income for people to flexibly meet their needs (BICN Citation2019). However, financial ability to adapt does not replace a desire for autonomous mobility within non-disabling environments. More work is needed to integrate considerations of disability and difference in design and management across places of food access. The political will must be made to enforce accessibility rules, like the AODA, including during periods of construction, adverse weather events, or mechanical breakdowns. Greater consultation and consideration of disabled people and financial commitment to accessibility would allow for places that truly meet people’s need, rather than meeting technical accessibility requirements. These changes could ensure that disabled people are ‘at the table’, included and prioritized in systems of food access.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrews, G. J., E. Hall, B. Evans, and R. Colls. 2012. “Moving beyond Walkability: On the Potential of Health Geography.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 75 (11): 1925–1932. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.013.

- Angus, J., L. Seto, N. Barry, N. Cechetto, S. Chandani, J. Devaney, S. Fernando, L. Muraca, and F. Odette. 2012. “Access to Cancer Screening for Women with Mobility Disabilities.” Journal of Cancer Education: The Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education 27 (1): 75–82. doi:10.1007/s13187-011-0273-4.

- Avineri, E., D. Shinar, and Y. O. Susilo. 2012. “Pedestrians’ Behaviour in Cross Walks: The Effects of Fear of Falling and Age.” Accident Analysis and Prevention 44 (1): 30–34. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2010.11.028.

- Barnes, C., and A. Sheldon. 2010. “Disability, Politics and Poverty in a Majority World Context.” Disability & Society 25 (7): 771–782. doi:10.1080/09687599.2010.520889.

- BICN (Basic Income Canada Network). 2019. Signposts to Success: Report of a BICN Survey of Ontario Basic Income Recipients. Ottawa, ON: BICN.

- Bigonnesse, C., A., H. Mahmood, W. B. Chaudhury, W. C. Mortenson, W. C. Miller, and K. A. Martin Gini. 2018. “The Role of Neighborhood Physical Environment on Mobility and Social Participation among People Using Mobility Assistive Technology.” Disability & Society 33 (6): 866–893. doi:10.1080/09687599.2018.1453783.

- Borowko, W. 2008. “Food Insecurity among Working-Age Canadians with Disabilities.” Master’s diss., Simon Fraser University.

- Bostock, L. 2001. “Pathways of Disadvantage? Walking as a Mode of Transport among Low-Income Mothers.” Health & Social Care in the Community 9 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2524.2001.00275.x.

- CANCEA (Canadian Centre of Economic Analysis). 2018. Toronto Housing Market Analysis: From Insight to Action. Toronto, ON: CANCEA.

- Carpiano, R. M. 2009. “Come Take a Walk with Me: The “Go-Along” Interview as a Novel Method for Studying the Implications of Place for Health and Well-Being.” Health & Place 15 (1): 263–272. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003.

- Caspi, C., G. Sorensen, S. V. Subramanian, and I. Kawachi. 2012. “The Local Food Environment and Diet: A Systematic Review.” Health & Place 18 (5): 1172–1187. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.006.

- CILT (Centre for Independent Living in Toronto). 2019. “About Us”. Toronto, ON: CILT. Accessed 2 December 2019. https://www.cilt.ca/about-us/

- Chouinard, V., and V. A. Crooks. 2005. “Because They Have All the Power and I Have None’: State Restructuring of Income and Employment Supports and Disabled Women’s Lives in Ontario, Canada.” Disability & Society 20 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/0968759042000283610.

- Chung, W. T., W. T. Gallo, N. Giunta, M. E. Canavan, N. S. Parikh, and M. C. Fahs. 2012. “Linking Neighborhood Characteristics to Food Insecurity in Older Adults: The Role of Perceived Safety, Social Cohesion, and Walkability.” Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 89 (3): 407–418. doi:10.1007/s11524-011-9633-y.

- City of Toronto. 2020a. “Accessibility at the City of Toronto”. City of Toronto. Accessed 23 March 2020. http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=7ed9e29090512410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRDandvgnextchannel=d90d4074781e1410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

- City of Toronto. 2020b. “Clearing Snow and Ice from the Sidewalk”. City of Toronto. Accessed 19 February 2020. https://www.toronto.ca/services-payments/streets-parking-transportation/road-maintenance/winter-maintenance/clearing-snow-and-ice-from-your-property/

- Coleman-Jensen, A., and M. Nord. 2013. Food Insecurity among Households with Working-Age Adults with Disabilities. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Coveney, J., and L. A. O’Dwyer. 2009. “Effects of Mobility and Location on Food Access.” Health & Place 15 (1): 45–55. Available online at: https://www.dsg-sds.org. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.010.

- Crooks, V. A. 2004. “Income Assistance (the ODSP) and Disabled Women in Ontario, Canada: Limited Program Information, Restrictive Incomes and the Impacts upon Socio-Spatial Life.” Disability Studies Quarterly 24 (3). doi:10.18061/dsq.v24i3.507.

- Cummins, S., S. Curtis, A. V. Diez-Roux, and S. Macintyre. 2007. “Understanding and Representing ‘Place’ in Health Research: A Relational Approach.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 65 (9): 1825–1838. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.036.

- Delaire, M., and M. Adler. 2019. “‘Assessing Access: Wheel-Trans’ High Ratings Confuse Users in Toronto”. toronto.com. February 19. Accessed 26 April 2021. https://www.toronto.com/news-story/9749678-assessing-access-wheel-trans-high-ratings-confuse-users-in-toronto/

- Foodbanks Canada. 2019. Report: Rate of Foodbank Use among Single People Hits Record High. Toronto, ON: Foodbanks Canada.

- Dyck, I. 1995. “Hidden Geographies: The Changing Lifeworlds of Women with Multiple Sclerosis.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 40 (3): 307–320. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0091-6.

- Goodley, D. 2014. Dis/Ability Studies: Theorising Disablism and Ableism. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Goodley, D., R. Lawthom, K. Liddiard, and K. Runswick-Cole. 2019. “Provocations for Critical Disability Studies.” Disability & Society 34 (6): 972–997. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.1566889.

- Government of Ontario. 2015. “About Accessibility Laws”. Government of Ontario. Accessed 2 December 2019. https://www.ontario.ca/page/about-accessibility-laws.

- Government of Ontario. 2018. “Ontario Disability Support Program - Income Support”. Ontario Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services. Accessed 18 December 2019. https://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/mcss/programs/social/directives/odsp/is/6_1_ODSP_ISDirectives.aspx.

- Gundersen, C., and J. P. Ziliak. 2015. “Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes.” Health Affairs (Project Hope) 34 (11): 1830–1839. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645.

- Gundersen, C., and J. P. Ziliak. 2018. “Food Insecurity Research in the United States: Where We Have Been and Where We Need to Go.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 40 (1): 119–135. doi:10.1093/aepp/ppx058.

- Hahn, H. 1986. “Disability and the Urban Environment: A Perspective on Los Angeles.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 4 (3): 273–288. doi:10.1068/d040273.

- Hamelin, A. M., J. P. Habicht, and M. Beaudry. 1999. “Food Insecurity: Consequences for the Household and Broader Social Implications.” The Journal of Nutrition 129 (2S Suppl): 525S–528S. doi:10.1093/jn/129.2.525S.

- Hansen, N., and C. Philo. 2007. “The Normality of Doing Things Differently: Bodies, Spaces and Disability Geography.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 98 (4): 493–506. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2007.00417.x.

- Health Canada. 2007. Canadian Community Health Survey, Cycle 2.2, Nutrition (2004): Income-Related Household Food Security in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Health Products and Food Branch.

- Heflin, C. M., C. E. Altman, and L. L. Rodriguez. 2019. “Food Insecurity and Disability in the United States.” Disability and Health Journal 12 (2): 220–226. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.09.006.

- Huang, J., B. Guo, and Y. Kim. 2010. “Food Insecurity and Disability: Do Economic Resources Matter?” Social Science Research 39 (1): 111–124. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.07.002.

- Huang, D. L., D. E. Rosenberg, S. D. Simonovich, and B. Belza. 2012. “Food Access Patterns and Barriers among Midlife and Older Adults with Mobility Disabilities.” Journal of Aging Research 2012: 231489–232204. doi:10.1155/2012/231489.

- Huot, S., and D. Laliberte Rudman. 2015. “Extending beyond Qualitative Interviewing to Illuminate the Tacit Nature of Everyday Occupation: Occupational Mapping and Participatory Occupation Methods.” OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health 35 (3): 142–150. doi:10.1177/1539449215576488.

- Imrie, R., and M. Kumar. 1998. “Focusing on Disability and Access in the Built Environment.” Disability & Society 13 (3): 357–374. doi:10.1080/09687599826687.

- Kitchin, R. 1998. “Out of Place’,’knowing One’s Place’: Space, Power and the Exclusion of Disabled People.” Disability & Society 13 (3): 343–356. doi:10.1080/09687599826678.

- Korotchenko, A., and L. Hurd Clarke. 2014. “Power Mobility and the Built Environment: The Experiences of Older Canadians.” Disability & Society 29 (3): 431–443. doi:10.1080/09687599.2013.816626.

- Kusenbach, M. 2003. “Street Phenomenology: The Go-Along as Ethnographic Research Tool.” Ethnography 4 (3): 455–485. doi:10.1177/146613810343007.

- Lightman, E., A. Vick, D. Herd, and A. Mitchell. 2009. “‘Not Disabled Enough’: Episodic Disabilities and the Ontario Disability Support Program.” Disability Studies Quarterly 29 (3). Available online at: https://www.dsg-sds.org doi:10.18061/dsq.v29i3.932.

- Liu, Y. C., and Y. C. Tung. 2014. “‘Risk Analysis of Pedestrians’ Road-Crossing Decisions: Effects of Age, Time Gap, Time of Day, and Vehicle Speed.” Safety Science 63: 77–82. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2013.11.002.

- Mahmood, A., E. O’Dea, C. Bigonnesse, D. Labbe, T. Mahal, M. Qureshi, and W. B. Mortenson. 2020. “Stakeholders Walkability/Wheelability Audit in Neighbourhoods (SWAN): User-Led Audit and Photographic Documentation in Canada.” Disability & Society 35 (6): 902–925. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.1649127.

- MPI (Martin Prosperity Institute). 2010. Food Deserts and Priority Neighbourhoods in Toronto. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto, Rotman School of Management.

- Matthews, M. H., and P. Vujakovic. 1995. “Private Worlds and Public Places: Mapping the Environmental Values of Wheelchair Users.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 27 (7): 1069–1083. doi:10.1068/a271069.

- Maytree. 2019. Welfare in Canada. Toronto, ON: Maytree.

- McQuigge, M. 2019. “Review of Ontario Accessibility Finds Province is Failing Disabled Residents”. The Globe and Mail.” March 8. Accessed 26 April 2021. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-review-of-ontario-accessibility-finds-province-is-failing-disabled/

- Mojtahedi, M. C., P. Boblick, J. H. Rimmer, J. L. Rowland, R. A. Jones, and C. L. Braunschweig. 2008. “Environmental Barriers to and Availability of Healthy Foods for People with Mobility Disabilities Living in Urban and Suburban Neighborhoods.” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 89 (11): 2174–2179. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2008.05.011.

- Oliver, M. 1996. Understanding Disability: From Theory to Practice. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

- Palmer, M. 2011. “Disability and Poverty: A Conceptual Review.” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 21 (4): 210–218. doi:10.1177/1044207310389333.

- Pașcalău-Vrabete, A., and A. Băban. 2018. “Is ‘Different’ Still Unacceptable? Exploring the Experience of Mobility Disability within the Romanian Social and Built Environment.” Disability & Society 33 (10): 1601–1619. doi:10.1080/09687599.2018.1503592.

- Peers, D., N. Spencer-Cavaliere, and L. Eales. 2014. “Say What You Mean: Rethinking Disability language in Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly.” Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly: APAQ 31 (3): 265–282. doi:10.1123/apaq.2013-0091.

- Retting, R. A., S. A. Ferguson, and A. T. McCartt. 2003. “A Review of Evidence-Based Traffic Engineering Measures Designed to Reduce Pedestrian-Motor Vehicle Crashes.” American Journal of Public Health 93 (9): 1456–1463. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.9.1456.

- Ross, T., and R. Buliung. 2019. “Access Work: Experiences of Parking at School for Families Living with Childhood Disability.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 130: 289–299. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2019.08.016.

- Shaw, H. J. 2006. “Food Deserts: Towards the Development of a Classification.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 88 (2): 231–247. doi:10.1111/j.0435-3684.2006.00217.x.

- She, P., and,G.A. Livermore. 2007. “Material Hardship, Poverty, and Disability among Working-Age Adults.” Social Science Quarterly 88 (4): 970–989. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00513.x.

- Schwartz, N., V. Tarasuk, R. Buliung, and K. Wilson. 2019. “Mobility Impairments and Geographic Variation in Vulnerability to Household Food Insecurity.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 243: 112636. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112636.

- Schwartz, N., R. Buliung, and K. Wilson. 2019. “Disability and Food Access and Insecurity: A Scoping Review of the Literature.” Health Place 57: 107–121. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.03.011.

- Shantz, J. 2011. “Poverty, Social Movements and Community Health: The Campaign for the Special Diet Allowance in Ontario.” Journal of Poverty and Social Justice 19 (2): 145–158. doi:10.1332/175982711X574012.

- Statistics Canada. 2019. “Toronto Profile”. Statistics Canada. Accessed 3 December 2019. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=EandGeo1=CSDandCode1=3520005andGeo2=PRandCode2=35andSearchText=TorontoandSearchType=BeginsandSearchPR=01andB1=AllandTABID=1andtype=0.

- Tarasuk, V., A. Mitchell, and N. Dachner. 2016. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2014. Toronto, ON: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF).

- Tarasuk, V., and A. Mitchell. 2020. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2017-18. Toronto, ON: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF).

- Tarasuk, V. 2016. “Health Implications of Food Insecurity.” In Social Determinants of Health: Canadian Perspectives, edited by D. Raphael. 3rd ed. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholar’s Press Inc. pp. 321–342.

- TTC (Toronto Transit Commission). 2020. “2014-2018 Multi-Year Accessibility Plan”. TTC. Accessed 23 March 2020. https://www.ttc.ca/TTC_Accessibility/Accessible_Transit_Services_Plan/2014_2018/index.jsp.

- TTC (Toronto Transit Commission). 2018. “Late Cancellation and No-Show FAQ”. TTC. Accessed 16 March 2020. https://www.ttc.ca/WheelTrans/late_cancellation_policy_faq.jsp.

- TTC (Toronto Transit Commission). 2019. “Prices.” TTC. Accessed 6 December 2019. https://www.ttc.ca/Fares_and_passes/Prices/Prices.jsp.

- Urry, J. 2004. “The ‘System’ of Automobility.” Theory, Culture and Society 21 (4-5): 25–39. doi:10.1177/0263276404046059.

- Vozoris, N. T., and V. Tarasuk. 2003. ” “Household Food Insufficiency is Associated with Poorer Health.” The Journal of Nutrition 133 (1): 120–126. doi:10.1093/jn/133.1.120.

- Walker, R. E., C. R. Keane, and J. G. Burke. 2010. “Disparities and Access to Healthy Food in the United States: A Review of Food Deserts Literature.” Health & Place 16 (5): 876–884. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.013.

- Webber, C. B., J. Sobal, and J. S. Dollahite. 2007. “Physical Disabilities and Food Access among Limited Resource Households.” Disability Studies Quarterly 27 (3). Available online at: https://www.dsg-sds.org. doi:10.18061/dsq.v27i3.20.

- Whelan, A., N. Wrigley, D. Warm, and E. Cannings. 2002. “Life in a ‘Food Desert’.” Urban Studies 39 (11): 2083–2100. doi:10.1080/0042098022000011371.

- Wolfe, W. S., C. M. Olson, A. Kendall, and E. A. Frongillo. 1996. “Understanding Food Insecurity in the Elderly: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Nutrition Education 28 (2): 92–100. doi:10.1016/S0022-3182(96)70034-1.

- Wolfe, W. S., E. A. Frongillo, and P. Valois. 2003. “Understanding the Experience of Food Insecurity by Elders Suggests Ways to Improve Its Measurement.” The Journal of Nutrition 133 (9): 2762–2769. doi:10.1093/jn/133.9.2762.