Abstract

Autistic people appear to have a higher risk of becoming and remaining homeless than people without autism. This article is based on a wider research study exploring diverse homelessness experiences in Oxford, UK. Using life mapping, a visual research method, we gained verbal and visual accounts of participants’ housing and homeless histories. These accounts support past evidence of higher than expected levels of autism among homeless people, while highlighting for the first time specific, additional risks of homelessness among autistic people. This group also appeared to have fewer means to reduce the risk of homelessness, and faced multiple challenges to resolving their homelessness. Our findings extend existing understandings of autism and homelessness, and of the disabling practices that autistic people may face within the diversity of homeless experiences, while adding valuable biographic detail to the factors leading to homelessness and attempts to exit homelessness. We also discuss potential policy interventions.

Recent evidence suggests that people on the autism spectrum are more likely than people without autism to experience homelessness, and their homeless experiences may also be different

We asked people who were or recently had been homeless, to draw and talk about their housing and homeless histories, exploring a wide range of homeless experiences, including street homelessness, living in hostels, and temporary housing

We found an unexpectedly high number of autistic people in our sample, suggesting that people on the autism spectrum may be at higher risk of homelessness. Autistic people also had fewer means of avoiding homelessness, and faced particular challenges to resolving homelessness

Our findings can inform local councils and homelessness services about the barriers autistic people may face within these systems. We urge that policies and ways of working be made more autism-aware and so improve the lives of autistic homeless people

Points of interest

Introduction

Within the medical model, autism is a developmental disorder characterised by difficulties in communication and social interaction, inflexible thought, limited social imagination, repetitive behaviour, and unusually narrow interests (Allison, Auyeung, and Baron-Cohen Citation2012; Lai, Lombardo, and Baron-Cohen Citation2014). In contrast, the social model of disability uses the term neurodiverse—as used within this paper—to challenge the naturalistic, disorder-focussed narrative, with advocates highlighting the different abilities and specific strengths of many autistic people, arguing that these deserve respect and protection (Runswick-Cole Citation2014). Its counter term, ‘neurotypical’ refers to people with ‘typical’ developmental and cognitive abilities and commonly denotes people without autism. Reimagining autism in this way, however, is not to disregard the significant challenges faced by people on the autism spectrum in navigating daily life within societies determined by neurotypical (non-autistic) expectations and structures. These challenges are multidimensional, including stress (Hirvikoski and Blomqvist Citation2015) mental health issues (Cage, Di Monaco, and Newell Citation2018), and lower employment rates (National Autistic Society Citation2016). Following Chown et al. (Citation2017) and noting debates over terminology, we refer interchangeably to the identity-first ‘autistic people’ and the person-first ‘people on the autism spectrum’.

Alongside the recognised challenges faced by autistic people, recent evidence suggests that they may also be more likely to experience homeless (Churchard et al. Citation2019; Kargas et al. Citation2019). Homelessness refers to a diversity of experiences, ranging from precarious or unsuitable housing through to rough sleeping, where it is common for people to cycle through different homeless experiences as their circumstances change (Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2021). Regardless of its exact type, homelessness is a clear marker of extreme social exclusion. The consequences of homelessness, including mental and physical health problems (Homeless Link Citation2014), significantly reduced lifespans (ONS Citation2020), and violence (WHAT Citation2016) make homelessness a central social and policy challenge.

Researchers have recently begun to explore homelessness among autistic people in the UK. Churchard et al. (Citation2019) estimated that 12.3 per cent of homeless service users within a London outreach team had elevated autistic traits and a further 8.5 per cent had marginal autistic traits, while 18.5 per cent of residents in a Lincolnshire homeless shelter screened positive for autism (Kargas et al. Citation2019). Within non peer-reviewed literature, Pritchard (Citation2010) noted autistic traits among nine of 14 entrenched rough sleepers in Devon, while Evans (Citation2011) reported that 12 per cent of people on the autism spectrum in Wales had experienced homelessness. These figures are far higher than autism prevalence rates in the general population—an estimated one per cent of children (Baron-Cohen et al. Citation2009) and 0.8 per cent of adults (Brugha et al. Citation2016)—and identify autism and homelessness as a significant yet under-researched social issue. Improved understandings of the links between autism and homelessness may offer insights into housing and homelessness policies that acknowledge the specific—yet poorly understood—housing issues experienced by people on the autism spectrum. Such considerations could fill recognised evidence gaps, where UK autism research has generally neglected societal issues and services for autistic people (Pellicano, Dinsmore, and Charman Citation2014).

The current article is based on a broader qualitative study that explored people’s homeless trajectories and transitions between homelessness experiences, including exits from homelessness. The full study was not specifically focused on autism, yet we were struck by the number of participants who either disclosed an autism diagnosis or displayed traits suggestive of autism. This article builds on and valuably extends existing research evidence on autism and homelessness in two key ways: first, its lifecourse perspective enabled an exploration of the long-term, cumulative risk factors that commonly underpin homelessness experiences, but are yet to be examined among autistic homeless people. In doing so, the article builds on existing work exploring the high level of autism among homeless people (Churchard et al. Citation2019; Kargas et al. Citation2019) by considering the underlying reasons for this pattern. Second, recognising the wide range of homelessness experiences, the article extends small studies of rough sleepers (Pritchard Citation2010; Stone Citation2019) to examine a more diverse range of homeless experiences than previously considered.

Methods

Methodological approach

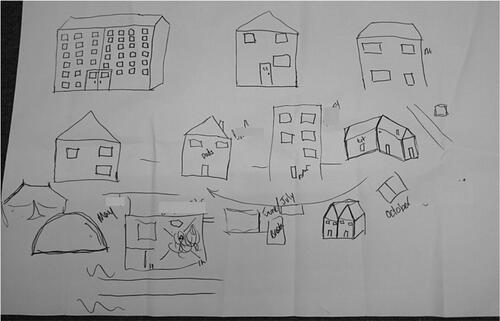

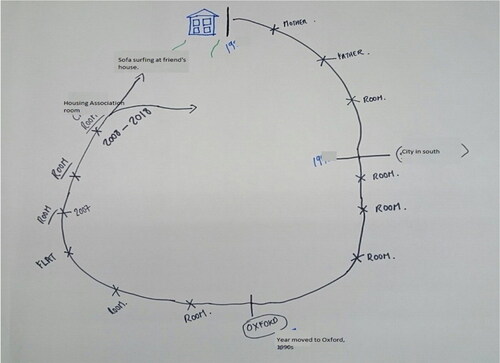

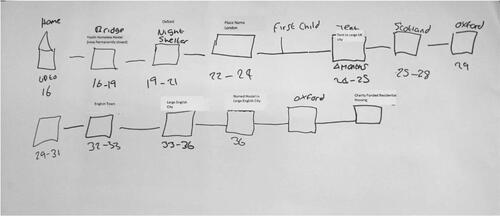

We used the qualitative method of life history interviewing, a narrative approach in which participants give a personal account of their life, in their own words, from childhood to the present day (Atkinson Citation2001). Ours was a guided life history interview, framed by people’s housing and homeless histories. We also used life mapping, a visual research method where participants drew their full housing and homeless histories (see , for example).

The life mapping technique suited the research aim of examining participants’ ‘homeless biograph[ies]’ (Chamberlain and Johnson Citation2013: 62), with a specific focus on points of transition or change between different housing and homelessness episodes. Alongside this particular emphasis, our interest in transitions also helped elicit multi-dimensional accounts of change that included broader themes including relational, financial, health, and employment factors. The life history approach offered insights into the circumstances that contributed to both initial and subsequent homeless episodes, which in many cases had developed over a long period of time. Methodologically, one key advantage of visual methods is their potential to elicit understandings that are unable to be expressed verbally (Gauntlett Citation2007), which is particularly valuable when exploring emotions or complex self-identities such as those associated with experiences of homelessness. The reflective process involved in creating something is also argued to be ‘different’ (Gauntlett and Holzwarth Citation2006: 84), and consequently may offer original insights into participants’ lifeworlds. By creating a ‘concrete frame of reference’ (Hollomotz Citation2018: 157), creative methods can also promote inclusive research by facilitating the abstract thought required for successful interviews while reducing reliance on verbal communication that can serve to exclude people with disabilities (Aldridge Citation2007). Considering autism specifically, life mapping had potential to overcome difficulties in constructing narratives, where autistic people may experience challenges in sequentially ordering their accounts (Stone Citation2017) or in determining relevant information (McCabe, Hillier, and Shapiro Citation2013). For a detailed discussion of life mapping techniques, please see (Garratt, Flaherty, and Barron Citation2021; Flaherty and Garratt, under review).

Procedure

We purposively recruited participants via staff and recruitment posters at relevant third sector organisations, advice centres, housing departments, through a local online classifieds website, and using snowball sampling. Interviews took place in support service locations, local community spaces, and the researchers’ offices. The nature and purpose of the research was verbally explained to participants and an accompanying information sheet supplied. An oral consent process was used.

During the life mapping process, participants either sat with flipchart paper spread out on a table, or stood with the paper pinned to the wall. Interviews began by asking participants to draw the first place they remembered living as a child. We deliberately avoided using the word ‘home’, due to its connotations beyond a physical structure. Participants proceeded to recount their full housing histories, ending with their current housing situation. The format and presentation of participants’ life maps, and the interplay between verbal interview data and visual mappings were deliberately left open to encourage expression and avoid constraining participants. For example, Emma drew her housing history in a circle (see ) while Paul drew a very simple representation, linked to his age (). While giving their verbal accounts, participants would sometimes pause drawing to relay more information. Some pointed to their map or embellished earlier drawings as their narrative developed or they recalled further details. We used a topic guide to probe participants about why they had left housing situations or to encourage further detail, sometimes pointing at relevant features on the mapping when doing so. On average, interviews lasted 90 min. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Participants

In the full study we recruited 39 homeless adults with diverse experiences, including sofa surfing, sleeping in tents, homeless and commercial hostels, and street homelessness. Participants were eligible if they self-identified as currently homeless or had been homeless in the past three years.

As noted, the study was not specifically focussed on autism, consequently we used no autism diagnostic or screening tools (indeed, no validated screening tool exists for homeless populations [Sappok, Heinrich, and Underwood Citation2015]). Nonetheless, we were struck by the unexpectedly high number of participants who either disclosed an autism diagnosis or clearly displayed autistic traits, and were consequently concerned to understand why this might be. The current analysis is from five participants who reported autism or displayed autistic traits; we refer to these participants as autistic (). One author (JF) has an in-depth knowledge of autism and experience of working with people on the autistic spectrum in a support role for the National Autistic Society and as an intensive family support worker, trained in autism awareness. This awareness introduced an ethical dilemma about whether to identify participants as being on the autism spectrum if they displayed autistic-like traits but without clinical diagnosis. In light of the under-diagnosis of autism in adults, especially women (Lai and Baron-Cohen Citation2015), our motivation to explore this important yet under-researched topic prevailed over the potential problems of identifying people as autistic (Hodge Citation2005; Jones et al. Citation2015). We nonetheless acknowledge the inherent difficulties with this position and revisit these in the Discussion. To reach agreement over participants’ possible autism status, the researchers each listened to audio recordings and read the transcripts in full before discussing each participant in detail, in some cases enhanced by informal observations from support services. For ethical reasons we did not share these observations with participants and only enquired about autism if this was directly mentioned by participants.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

A greater proportion of women (3 of 14) than men (2 of 25) were autistic. The youngest two reported an autism spectrum condition diagnosis, while the eldest (50+) was awaiting diagnosis. None of the five autistic participants demonstrated or disclosed an intellectual disability, or significant alcohol or other substance use. Three had received mental health diagnoses at different points in their lives.

Analysis

We took a realist approach to thematic data analysis, which assumes a straightforward relationship between participants’ experiences and the language used to describe them (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). This approach was appropriate both to our study’s practical focus and the direct communication skills characteristic of autistic people. Correspondingly, we undertook inductive analysis, a data-driven approach that involved examining each transcript in detail to identify the most frequent or dominant analytical themes related to homelessness and autism, but not drawing heavily on relevant theories (deductive analysis), which have yet to be developed (Thomas Citation2006).

The study dataset comprised transcripts from the five autistic participants, alongside fieldwork notes. We used the life mapping data to supplement participants’ verbal accounts of their housing and homeless trajectories. To ensure consistency, interview data were coded thematically by both researchers, who met regularly to discuss emerging themes. We made comparisons between the study dataset and transcripts from the full study when identifying overlapping or divergent experiences between autistic and neurotypical participants. We used NVivo software (v12) to organise the dataset and to support the analytic process.

Ethical considerations

Recognising the vulnerability of homeless people and of autistic homeless people in particular, certain ethical considerations were prominent. The life mapping technique sought to reframe power dynamics within the research exchange and thereby maximise participants’ self-esteem. Like other researchers have found before us (McCulloch Citation2015; Sheridan, Chamberlain, and Dupuis Citation2011; Söderström Citation2020), some participants—both autistic and neurotypical—had difficulty engaging with life mapping: One participant, Nathan explicitly stated that his autism made visualisation impossible, consistent with evidence for specialist thinking styles that hinder visual thinking (Grandin Citation2009). In such instances we conducted a standard semi-structured qualitative interview, relying more heavily on interview prompts. An extra dimension of sensitivity was required where participants’ autistic traits became apparent during the interview. In these instances, we sought to communicate especially clearly and directly, and gave participants longer to respond. We also allocated time before and after the interview to discuss concerns or areas of interest to participants. All participants were given information signposting them to support services. All participants are referred to using pseudonyms. The study was approved by Oxford University’s Central University Research Ethics Committee, reference R59704/RE001.

Results

Our analyses identified three key themes: (1) Autism and a higher risk of homelessness; (2) Autism and fewer opportunities to avoid homelessness; (3) Autism and greater challenges to resolving homelessness (). We discuss these themes and their associated subthemes below.

Table 2. Analytical themes and subthemes.

Autism and a higher risk of homelessness

Financial precarity

Participants’ employment histories—characterised by low-waged, precarious work—were typical of the generally low employment rates among autistic people. Only Emma (female, 40 to 49) had spent significant time in employment, referring to the ‘work and survival’ of telesales roles:

You take on a lot, you do a lot, you work very long hours, or I did, not, not nice, I mean, there’s nice jobs, you just sign off at five and go, just ones that you’re completely committed to and in, erm, and delivering and I always worked really, really hard to make sure I’m okay to be there….

These precarious employment and financial situations inevitably restricted the housing options available, often resulting in insecure housing. For example, Caroline lodged briefly with a family until they asked for the room back with just a few days’ notice. Emma had similarly ‘chaotic’ experiences, finding rooms in newspaper adverts and lodging informally with families, leaving her without recourse to housing legislation if things went wrong.

Challenges living with others

Financial precarity confined some participants to shared living environments. Shared accommodation—often the only option in the private rented sector, in hostels, third-sector facilities and move-on options—was a source of stress and conflict both for the full sample, and particularly so for participants on the autism spectrum. Mutual difficulties in personal and social interaction both created behaviours that others found challenging, while undermining autistic participants’ ability to tolerate challenging behaviours in those they lived with. Again, while problematic shared living situations were not unique to the five autistic participants, this group reported specific difficulties in these spaces. For example, Caroline’s untidiness created conflict in several housing situations she recounted, demonstrating how behaviours that may have been manifestations of her autism—and that were not described by any neurotypical participants—were perceived as inconsiderate: ‘We would have arguments…and we would have meetings and they’d [former housemates] sort of blame me for things that were going wrong’.

Autism as an additional risk of homelessness

A key novel finding was that autism itself also appeared to create a direct, additional risk of homelessness, unmediated by other factors, introducing a risk of homelessness that was specific to autistic participants. Being autistic within a neurotypical society led to misunderstandings and an overwhelming burden of behavioural expectations. By taking a lifecourse approach we learned that a lack of support for his autism was directly responsible for several of Paul’s homeless episodes. On three occasions (and with two partners), Paul (male, 30-39) became homelessness following relationship breakdowns, describing how ‘my mental health, just, just sent me away’ from his first partner and their two young children, then later explaining how ‘in the end she [second partner] couldn’t do it no more, it was just too much for her to carry’. We note here that while autism is a neurodevelopmental condition, ‘mental health’ was sometimes used by participants as shorthand for autism—such as Paul’s usage here and throughout his interview.

An additional risk was evident for autistic women: Tinsel (female, 30 to 39) was sexually abused by two men when living in shared supported accommodation, then described ‘triggering’ experiences in a self-contained housing association flat where noise from nearby tenants ‘turned me into um [pause] big breakdown’, prompting her eviction for antisocial behaviour. Having been evicted, Tinsel was deemed intentionally homeless which limited the housing support available to her, and she began sleeping rough.

In identifying autism as introducing explicit risks of homelessness, we recognise that homelessness has complex and overlapping determinants that may not be entirely attributable to autism. We also acknowledge that these themes are as-yet unexplored with no existing body of knowledge to refer to, so our suggestions are therefore exploratory. Yet, we identify the experiences described here as specific to our autistic participants as they are consistent with other features and consequences of autism noted in existing literature, and moreover were not disclosed by neurotypical participants.

Autism and fewer opportunities to avoid homelessness

Reduced family and friendship networks

Our second analytic theme noted that when faced with housing crisis, many neurotypical participants were able to slow or even avoid homelessness by drawing on social networks, commonly returning to the safety net of the parental home following relationship breakdowns or for financial reasons. In contrast, however, none of the five autistic participants had strong family or friendship networks that might offer practical, emotional, or financial support.

When describing becoming street homeless at 17 when the tenancy on his ‘run-down’ bedsit ended, the precarity Paul faced as a consequence of his limited relationship with his parents was striking. He explained how ‘I always wanted to go home but I mean I knew that if I did, it wasn’t going to work anyway’, later elaborating: ‘I couldn’t go back home because … I didn’t, I didn’t see that, at the point I didn’t see eye to eye with my parents because of my mental health; they found it too hard’. At the time of interview, Paul described very limited familial relationships; he clearly lacked the emotional and practical support reported by many neurotypical participants. Emma likewise recognised ‘that whole sense of support’ that others were able to draw on, contrasting this with her experience of being ‘completely estranged’ from her family when facing homelessness in her 40 s: ‘And, erm, so, no, there were no real friendships or, or relationships, just my work and my room’.

Alongside family ties, many neurotypical participants avoided street homelessness by sofa surfing with friends. Conversely, all five autistic participants exhibited limited friendship networks, leaving them without the extra layer of support that many neurotypical participants depended upon. Consequently, Paul, Nathan and Tinsel all quickly became street homeless when faced with housing crisis. On the verge of street homelessness at 16, Tinsel described: ‘I was so cold [when rough sleeping], and I didn’t have anybody to, I didn’t have a friend to go “oh, you know can you put me up?” No, I didn’t have that’. Nathan (male, 50+) also mentioned no friends, immediately sleeping in his car upon leaving his long-term partner’s home when their relationship ended. Paul similarly lacked the friendship networks that might have offered short-term accommodation or broader support when moving repeatedly between a homeless hostel and street homelessness. When asked directly, Paul explained ‘I, I, I don’t have friends and I still don’t to this day, yeah’, attributing his absence of friendships to trust issues arising from past experiences of abuse and intimidation (explored in detail below).

It is telling that the two autistic participants who had never slept rough had both been able to sofa surf with friends. Yet, unlike many neurotypical participants who typically drew upon wide friendship networks, both women relied upon one friend, intensifying the precarity of these living situations. Caroline had spent 4-5 years sofa surfing in the Housing Association flat of an ‘acquaintance/friend’ who had schizophrenia. While lengthy, Caroline described the arrangement as ‘quite stressful’ as lodging in this way was not permitted, and her friend’s parents repeatedly sought to have her evicted. When the arrangement eventually broke down, Caroline moved into emergency council-provided B&B accommodation. Emma was currently sofa surfing in her friend’s mother’s home while she was in hospital, but Emma knew that this arrangement would be inevitably brief, describing how ‘it’s just a little stay of execution… And so, erm, erm, yeah, so I know, I, I, erm, my next step will be homelessness…’.

Autism and greater challenges to resolving homelessness

Resolving homelessness typically requires people to engage with statutory and non-statutory services. Formal services were particularly important for autistic people who faced financial barriers to securing housing, and typically had more limited social networks. However, our third analytic theme noted how autistic people faced particular challenges in accessing and benefitting from the services aimed at resolving their homelessness.

Unmet needs in homeless hostels

Our interviews revealed a clear mismatch between autistic participants’ housing needs and available provision. Nathan described hostel accommodation as ‘a total madhouse’, refusing shared accommodation here, thereby becoming estranged from support and consequently remaining sleeping rough. Tinsel likewise described challenges with hostel routines:

That’s, that what happens a lot of the time at [hostel A] and [hostel B] is they do checks on you twice a day, right? So, even though you have got your lovely own room in this homeless hostel or night shelter you have them come in, check on you, see if you are alright. And it, the times are all over the place, they are supposed to be at set times but they’re not.

Limited access to social housing

The housing needs of people on the autism spectrum were also poorly met by social housing provision. Access to social housing is secured via a Housing Register, a prioritised list of applicants who are waiting to be offered a property, often for many years. While a housing needs assessment considers health and disability, no specific guidance relates to autism, and undiagnosed applicants would clearly not benefit. By failing to give specific housing register priority to autistic applicants, such a system overlooks the vulnerability to homelessness and heightened housing support needs among this group. Emma—who displayed autistic tendencies but did not report any diagnosis—was assigned low priority on the housing register after the charitable housing she had been living in closed, and had correspondingly low expectations of securing social housing: ‘I was allowed to go on the housing, they have no, they have no responsibility to house me if I’m homeless because I don’t fall into one of the sort of emergency categories’.

Paul had likewise joined the housing register in his 20 s and was told to expect a 15-20 year wait, reflecting that ‘So it’s been quite a…at least coming up to 20 years’. Throughout this time, Paul had no expectation of receiving housing assistance. Autistic people like Emma and Paul may be doubly disadvantaged by their low priority on the housing register and their potentially reduced ability to advocate for higher status or pursue alternative housing options when confronted with disabling systems and attitudes. The ‘invisibility’ of autism may result in interactions in which autistic people are perceived as odd or ill-mannered; conversely, being articulate may lead service staff to mistakenly conclude that support is not needed. Indeed, Emma blamed herself for her situation, not recognising the wider structural forces that made her vulnerable to homelessness: ‘I didn’t expect help, I’ve got myself into this situation and now I’d always been able to get out of it, I can’t get out of this situation and I know, I know that…’, later reiterating that ‘there’s nothing I can do to stop it [street homelessness]’.

Barriers to navigating support services

The complex and bureaucratic nature of statutory support systems can create obstacles to accessing appropriate support. Challenging interactions between autistic participants and neurotypical support services can easily be (mis)interpreted as shortcomings of autistic people and not as demonstrating the need for reciprocal and mutual exchange, which may have jeopardised participants’ chances of successfully navigating these systems. For example, Nathan meticulously researched organisational legislation to validate his complaints about the council and third sector homelessness organisations. Some of these appeared well-founded, such as the council’s seemingly contradictory attitude approach to intervening in different housing situations. While these actions appeared logical and appropriate to Nathan, they contributed to difficult relationships with overstretched organisations that may have closed off relevant support.

The various mismatches between autistic participants’ needs and communication styles and the unstated requirements and expectations of support services could likewise be misinterpreted as difficult or self-sabotaging behaviour. Clients on the autism spectrum appeared disadvantaged by protocols within homelessness accommodation, including warnings and exclusions for inappropriate behaviour. For example, Tinsel was evicted from hostel accommodation for deliberately smashing a plate after her post traumatic stress disorder was triggered by antisocial behaviour from other residents. After sleeping rough overnight, she was told to report to the hostel the following morning and reacted angrily when told that a decision had not been made about readmitting her, resulting in a second night’s eviction:

Yeah, and they said that [agreed] time and I was kind of all through the night it was that time that I was focusing on… You know and when that time come and I was reached with nothing you have to go back out there. I did hit my hand against a wall quite hard and that earnt me another night out [pause].

Risk of exploitation and mate crime

Worryingly, homeless people on the autism spectrum were also vulnerable to mate crime, a form of disability hate crime characterised by exploitation and abuse by those a person considers to be their friends (see Doherty Citation2020). When staying at a third-sector homeless hostel, Paul was intimidated under the threat of violence into selling drugs for others in the hostel:

Interviewer:Right and how did you pay for it [drugs he was coerced into taking], was it with your benefit money?

Paul:No, I, I had to go out and work for it. I had to go out and sell drugs for them.

Discussion

In this study we used narrative life mapping to identify three main analytic themes relating to autism and homelessness. First, a higher than expected number of participants disclosed an autism diagnosis or displayed autistic traits (5 of 39 or 12.8 per cent), a strikingly similar figure to that reported by Churchard et al. (Citation2019) (12.3 per cent) and slightly lower than noted by Kargas et al. (Citation2019) (18.5 per cent), yet far higher than general population estimates of less than one per cent (Brugha et al. Citation2016). While not seeking to generalise qualitative results from non-probability samples, our findings reinforce existing evidence for a concentration of autism among homeless people.

Many of the risk factors of homelessness—including poverty, housing affordability, and interpersonal challenges (Bramley and Fitzpatrick Citation2018; Garratt and Flaherty Citation2020)—overlapped with those experienced by neurotypical participants, yet were faced more intensely by participants on the autism spectrum. Of particular concern is the low rate of employment among autistic participants, where only Emma had a regular employment history, albeit in a series of unstable and poorly-paid jobs. Our findings are consistent with evidence that only 32 per cent of autistic people in the UK are in paid work (National Autistic Society Citation2016) and reinforce past research documenting the employment challenges facing autistic people (D. E. M. Milton and Sims Citation2016) and homeless autistic people specifically (Campbell and Winn Citation2015; Stone Citation2019). Collectively, these findings raise important questions about suitable employment opportunities for people on the autism spectrum.

Importantly, autism itself also appeared to introduce a direct, additional risk of homelessness. Relationship breakdowns are a common trigger for homelessness (Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2021), yet the specific challenges of navigating relationships between neurotypical and neurodiverse people introduced an additional vulnerability among autistic participants, as illustrated by Paul’s experiences. Likewise, Tinsel’s experience of sexual abuse—which led directly to mental health problems, eviction, and street homelessness—identifies homelessness as a consequence of the sexual abuse that is widespread among autistic women (Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy Citation2016). We are not aware of existing research on these themes; these novel findings therefore point to particular risks faced by participants on the autism spectrum (see also (Ryder Citation2017)). More detailed consideration both of these issues and suitable responses to these is therefore needed.

Second, participants on the autism spectrum had fewer opportunities to avoid homelessness, stemming from their limited social networks, which can prove protective in helping to slow or even avoid the gradual shift to homelessness. While an absence of family or friendship networks is not unique to autistic people (Garratt and Flaherty Citation2020), they seemed especially vulnerable (Campbell and Winn Citation2015; Grant Citation2017). In some cases this absence was directly attributable to the complexities of interpersonal interactions between neurodiverse and neurotypical people that may create difficulties in forming and maintaining these networks (Gray et al. Citation2014; Magiati, Tay, and Howlin Citation2014; D. E. M. Milton Citation2012). The precarity faced by those without supportive networks is revealing of the neoliberal foundations of statutory homelessness support in the UK. Council housing departments actively encourage those facing homelessness to seek help within their networks, which intensifies vulnerability among those without this safety net, with a disproportionate impact on neurodiverse groups.

Our third theme noted that autistic participants faced particular challenges to resolving homelessness. Autism influences a person’s support needs, including how they navigate often prescriptive frontline homeless services and their experiences of hostel accommodation, potentially impeding attempts to exit homelessness when operating within neurotypical processes and expectations (Churchard et al. Citation2019). The challenges described by our diverse participants (and reported previously by Kargas et al. [Citation2019]) reflect an overall lack of autism awareness that contributed to disabling practices. In particular, homeless hostels—a routine stage in the adult homeless pathway through which people progress with a view to finding long-term accommodation—were busy, noisy, anxiety-inducing and difficult to tolerate for many participants in the full study; these challenges were particularly acute for our autistic participants: Nathan refused hostel accommodation, while Tinsel’s hostel experiences triggered memories of sexual abuse that prompted short-term eviction from the hostel. An additional novel finding was autistic people’s susceptibility to mate crime, likely reflecting their isolation and consequent vulnerability, which risked trapping this group within a lifestyle that could make it difficult to exit homelessness. Our findings therefore suggest that autistic people face specific barriers to resolving their homelessness, challenges that require suitably informed and tailored support.

Policy suggestions

Our research findings suggest five policy suggestions. First, the accessibility of autism diagnoses needs improving to enable people to access tailored support and protection under disability legislation (Portway and Johnson Citation2005). As Tinsel noted, diagnosis, or its absence, can frame the care received: ‘Um [pause] and again this was before I was diagnosed with Asperger’s too, so they didn’t, they was always focused on my self-harm actually when I was in, in supporting[sic] housing’. Practically speaking, receiving housing support can be contingent upon an autism diagnosis (Campbell and Winn Citation2015). Difficulties accessing developmental history information may serve to magnify challenges to mainstream adulthood diagnosis among homeless people; Churchard et al. (Citation2019) autism screening measure for homeless people consequently has value by providing the probable identification of autism needed to access services. In advocating for improved access to diagnosis we are not seeking to valorise a deficit model of autism, and recognise the potential unwelcome symbolic and practical consequences of diagnosis (Forster and Pearson Citation2020; Hodge Citation2005; Jones et al. Citation2015; D. E. M. Milton and Sims Citation2016). Instead, our position recognises how service provision within current practice is grounded on assessments of need or often tacit behavioural expectations of service users that may be inappropriate or unrealistic for neurodiverse people, and where a diagnosis may have particular value. Further research exploring how diagnoses and screening tools are experienced in social work by homeless people and marginalised groups more broadly is doubtless needed.

Second, services need to adopt flexible, neurodiversity-aware practices. We identified barriers to autistic people accessing and engaging with housing and homelessness services equivalent to those reported for healthcare (Nicolaidis et al. Citation2015; Raymaker et al. Citation2017). This applied particularly to homeless hostels, where it is not uncommon for homeless people to favour rough sleeping over such spaces (Homeless Link Citation2015; Mcnaughton Nicholls Citation2009) due to mismatches between service provision and client needs (McMordie Citation2020) that may be heightened among autistic people. Indeed, Paul, Nathan, and Tinsel all recounted difficulties in homeless hostels. Ensuring that homeless hostels are psychologically informed and autism-friendly, in relation to structure, routine, and sensory stimulation (Glasgow City Council Citation2010; D. E. M. Milton and Sims Citation2016) has potential to reduce anxiety for autistic people and hinder behaviours that stem from unsuitable environments (Goodley and Runswick-Cole Citation2011). Resources such as the autism toolkit (Churchard Citation2019) and other practical guidance (Welsh Government Citation2019) will help equip frontline homeless services to make reasonable adjustments to the specific needs of neurodiverse clients, which are often overlooked despite legal recognition under the Equality Act 2010 (Beardon and Edmonds Citation2007; Forster and Pearson Citation2020; Portway and Johnson Citation2005).

Services must appreciate the tensions between autistic participants’ needs and communication styles, and the unstated requirements and expectations of support services. Responsibility for effective social interaction ought to be reframed within the ‘mutuality and reciprocity’ of social exchange, not in terms of supposed shortcomings of autistic people (D. E. M. Milton Citation2012). Doing so would have implications for service design and delivery by disrupting the deficit-based model and its associated expectations for autistic people to assimilate into unsuitable environments and processes in order to receive relevant support, which can prompt withdrawals of support where autistic people apparently fail to co-operate (Campbell and Winn Citation2015). This possibility was evident in Nathan’s descriptions of his interactions with both the local council and homeless pathway, which may have restricted the support he was offered. Under these conditions, services may become sites of oppression where people on the autism spectrum are less able to meet ableist expectations of behaviour and control (Forster and Pearson Citation2020). Practical and easily-implemented measures such as allowing autistic people to converse in writing could improve communication and avoid common misunderstandings between clients and services that may result in disengagement and an escalation of housing crises.

Third, policies are needed that address the structural risks of homelessness, recognising that autistic participants experienced these more intensely than their neurotypical peers. Pursuing autism-friendly recruitment practices (Beardon and Edmonds Citation2007) and workplace environments, and educating employers about the benefits of employing neurodiverse people (Evans Citation2011) are valuable strategies, yet such efforts must be accompanied by wages that are sufficient to cover stable and appropriate accommodation. While many participants in the full study had worked in low-waged jobs that left them financially vulnerable, this risk is heightened among autistic people, where only Emma had significant work history. In parallel, it is also vital that welfare benefits are adequate in both availability and value, noting that suitable work may not be available to all autistic people. UK government austerity policies over the past decade must be reversed to counter the risk of over-valorising paid work and promoting ableism amidst genuine barriers to employment among neurodiverse groups (Goodley, Lawthom, and Runswick-Cole Citation2014; Runswick-Cole and Goodley Citation2011).

Fourth, our findings revealed challenges in accessing social housing, reinforcing previous evidence highlighting the importance of accommodation support for autistic people (Beardon and Edmonds Citation2007). Autism awareness is needed to ensure that autistic applicants are suitably prioritised on housing registers. Noting that autistic people are more likely to refuse accommodation (Ryder Citation2017), greater sensitivity and flexibility is also needed when considering how this group are treated when attempting to access social housing. Several of our participants had accrued arrears from former properties, which can prevent them from bidding for housing or even from joining the housing register; modifications to such practices may prove valuable.

Finally, the vulnerability and needs of people on the autism spectrum may not be appreciated by housing officers making the assessments of ‘priority need’ that underpin accommodation offers (MHCLG Citation2019a). Initiatives such as Autism Cymru’s ‘Attention Card’ scheme can be used by autistic people when they encounter any emergency service, and serves to inform the service of their autism, offers guidance on effective communication, and provides contact details for further support and advice (Pagler Citation2011), and may thereby prove valuable in ensuring that autistic people’s needs are identified and met.

Strengths and limitations

This work has two key limitations. First, as the study did not specifically consider autism, identifying autistic participants relied upon their self-descriptions and on the researchers’ behavioural observations. We recognise that we may have attributed behaviours to autism that may have another cause, noting challenges to diagnosis even in clinical practice (Galanopoulos et al; Stavropoulos, Bolourian, and Blacher Citation2018). However, confining participation to diagnosed cases would overlook experiences of people with undiagnosed autism, particularly women (Lai and Baron-Cohen Citation2015; Loomes, Hull, and Mandy Citation2017) and older adults (James et al. Citation2006). In this regard, our approach has value in capturing and highlighting the experiences of a more diverse group of autistic participants. Other researchers exploring autism and homelessness have similarly relied upon behavioural observations (Stone Citation2017) or non-clinical screening tools (Churchard et al. Citation2019; Kargas et al. Citation2019). We nonetheless took steps to strengthen identification of autistic participants: (1) by carefully questioning participants about autism and ‘mental health’ (a term participants often used when referring to autism); (2) through detailed discussions between researchers; and (3) by seeking to corroborate our evaluations with those of support services. As previously noted, one author (JF) had previously worked directly with people with an autism diagnosis and was trained in autism awareness, so was well placed to recognise autism. Recognising that identifying people as autistic can be problematic (Hodge Citation2005; Jones et al. Citation2015) and that as researchers we were necessarily unable to provide suitable follow-up support, we did not share these observations with participants.

Second, this study sought a detailed exploration of people’s homelessness experiences in a specific local context. We acknowledge Oxford’s atypical characteristics: housing affordability is among the lowest in the country (Clancy Citation2019) and its rough sleeping rate exceeds the England average (8.2 and 2.0 per 10,000 households, respectively) (MHCLG Citation2019b), so caution is needed when considering the transferability of our findings to other settings. However, most neurotypical and all autistic participants had longstanding connections with Oxford, while high levels of autism among homeless people in diverse locations including Devon (Pritchard Citation2010), London (Churchard et al. Citation2019) and Lincolnshire (Kargas et al. Citation2019) further demonstrates that this phenomenon is not unique to Oxford.

We conversely note two key strengths. First, our consideration of the full range of homelessness experiences and the dynamics between these distinguishes our work from previous studies. Homelessness research typically considers specific sub-groups—commonly rough sleepers (Stone Citation2019) or certain service user groups (Churchard et al. Citation2019; Kargas et al. Citation2019)—limiting its application beyond these experiences. By framing our study in relation to housing and homelessness, we accessed a broader range of participants. In doing so we follow Churchard et al. (Citation2019) recommendation to explore autism in a more diverse group of homeless people, recognising that rough sleepers are a minority, and different forms of homelessness may require different policy responses. In the current project we learned that Emma and Caroline experienced considerable housing precarity as a consequence of their low incomes. These women had limited contact with homeless services and neither had slept rough, so their accounts contribute to a more holistic understanding of homelessness among autistic people.

The study’s second key strength is its lifecourse perspective. Methodologically, this approach may have helped participants to construct coherent and sequential narratives, which can be challenging for autistic people (McCabe, Hillier, and Shapiro Citation2013). Substantively, research into the causes of homelessness commonly examines immediate precipitating factors without considering longer-term risk factors (although exceptions exist, e.g.: May Citation2000; Ravenhill Citation2008). Our novel approach traced the lifetime causes of homelessness, identifying issues with employment, services, housing, and relationships. In doing so we learned that Tinsel’s antisocial behaviour, which led to eviction from her housing association flat into street homelessness, was triggered by flashbacks from earlier sexual abuse; detail we would not have learned without taking a lifecourse approach.

Future directions

While noting the breadth of unanswered questions about autism and homelessness, our novel findings suggest four specific areas for further research. First, following Kargas et al. (Citation2019), dedicated research examining suitable housing support and homelessness prevention activities could prove fruitful in understanding how to reduce the risks of initial homelessness among autistic people. For example, our observation that living closely with others was very challenging demonstrates the value of appropriate housing long before autistic people face homelessness directly. Second, exploring opportunities for people on the autism spectrum to build positive social networks and facilitating these in suitable ways has potential value in strengthening support networks that could protect against homelessness at times of crisis, noting that some autistic people do have positive family networks (Hurlbutt and Chalmers Citation2002). Exploring the development and maintenance of such networks in ways that recognise the mutual challenges of shared communication instead of placing sole responsibility on autistic people could thus prove valuable. Nurturing these positive social networks could also offer resilience against mate crime, where a desire for connection may make autistic people vulnerable to unsafe relationships (Fardella, Burnham Riosa, and Weiss Citation2018) that could both intensify the risk of initial homelessness and prolong homeless episodes. Third, a gender-informed exploration of autism and homelessness is needed in light of gender differences in both autism prevalence and in experiences of homelessness, where the potential for sexual exploitation creates an additional, serious, risk to autistic homeless women (Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy Citation2016). Fourth, work that extends the current exploratory study by seeking to directly interrogate and integrate the diverse range of themes we identified—for example, how social and financial difficulties in sustaining a tenancy might combine, or how unstable housing influences the development of social networks—will offer a richer and more holistic understanding of autism and homelessness. Across these research areas, future research would benefit from being conducted by, or in participation with, people on the autism spectrum, both to enhance research integrity and help embed a social model of disability within the research process (Chown et al. Citation2017; D. Milton and Bracher Citation2013).

Conclusion

Across its different forms, homelessness is a manifestation of severe social and financial exclusion. By taking a narrative, biographical approach, our findings extend recent evidence for an unexpectedly high number of autistic people among homeless groups, noting how autism itself also appeared to pose a range of direct, additional risk of homelessness among people on the autism spectrum. When faced with housing crisis, limited social networks offered autistic people fewer opportunities to avoid homelessness. We also draw attention to the multiple barriers encountered by this group when seeking to resolve their homelessness.

Notably, by drawing on participants from a range of homelessness experiences, our findings offer insights into less visible forms of housing instability and hidden homelessness than have previously been documented among autistic people. Alongside broad measures aimed at addressing the structural determinants of homelessness, our findings highlight the crucial need for better support for autistic people, aimed both at protecting this group from the initial risks of homelessness and in providing appropriate assistance to exit homelessness. In particular, embedding autism-awareness at every level of services and adopting Churchard’s (Citation2019) autism toolkit would better enable services to understand the changes needed in their approach to mitigate the risks of homelessness faced by people on the autism spectrum.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks are due to our participants for sharing their time and experiences with us. We are grateful to Dr Alasdair Churchard and Dr Will Mason for their insightful comments on previous drafts.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aldridge, Jo. 2007. “Picture This: The Use of Participatory Photographic Research Methods with People with Learning Disabilities.” Disability & Society 22 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/09687590601056006.

- Allison, Carrie, Bonnie Auyeung, and Simon Baron-Cohen. 2012. “Toward Brief “Red Flags” for Autism Screening: The Short Autism Spectrum Quotient and the Short Quantitative Checklist for Autism in toddlers in 1,000 cases and 3,000 controls [corrected].” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 51 (2): 202–212.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.11.003.

- Atkinson, R. 2001. “The Life Story Interview.” In Handbook of Interview Research, by Jaber Gubrium and James Holstein, 120–140. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Bargiela, Sarah, Robyn Steward, and Will Mandy. 2016. “The Experiences of Late-Diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 46 (10): 3281–3294. doi:10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8.

- Baron-Cohen, Simon, Fiona J. Scott, Carrie Allison, Joanna Williams, Patrick Bolton, Fiona E. Matthews, and Carol Brayne. 2009. “Prevalence of Autism-Spectrum Conditions: UK School-Based Population Study.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 194 (6): 500–509. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.059345.

- Beardon, Luke, and Genevieve Edmonds. 2007. The ASPECT Consultancy Report: A National Report on the Needs of Adults with Asperger Syndrome. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.34791!/file/ASPECT_Consultancy_report.pdf.

- Bramley, Glen, and Suzanne Fitzpatrick. 2018. “Homelessness in the UK: Who is Most at Risk?” Housing Studies 33 (1): 96–116. doi:10.1080/02673037.2017.1344957.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brugha, Traolach, Sally-Anne Cooper, Fiona J. Gullon-Scott, Elizabeth Fuller, Nev Ilic, Abdolreza Ashtarikiani, and Zoe Morgan. 2016. ‘Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey: Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, England, 2014. Chapter 6: Autism Spectrum Disorder’. NHS Digital. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/pdf/1/o/adult_psychiatric_study_ch6_web.pdf.

- Cage, E., J. Di Monaco, and V. Newell. 2018. “Experiences of Autism Acceptance and Mental Health in Autistic Adults.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 48 (2): 473–484. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3342-7.

- Campbell, Jacqueline Aneen, and Beverley Winn. 2015. Piecing Together a Solution: Homelessness amongst People with Autism in Wales. Cardiff: Shelter Cymru. https://sheltercymru.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Piecing-together-a-solution-Homelessness-amongst-people-with-autism-in-Wales.pdf.

- Chamberlain, Chris, and Guy Johnson. 2013. “Pathways into Adult Homelessness.” Journal of Sociology 49 (1): 60–77. doi:10.1177/1440783311422458.

- Chown, Nick, Jackie Robinson, Luke Beardon, Jillian Downing, Liz Hughes, Julia Leatherland, Katrina Fox, Laura Hickman, and Duncan MacGregor. 2017. “Improving Research about Us, with Us: A Draft Framework for Inclusive Autism Research.” Disability & Society 32 (5): 720–734. doi:10.1080/09687599.2017.1320273.

- Churchard, Alasdair. 2019. ‘Autism and Homelessness Toolkit’. Homeless Link. https://www.homeless.org.uk/sites/default/files/site-attachments/Autism_Homelessness_Toolkit.pdf.

- Churchard, Alasdair, Morag Ryder, Andrew Greenhill, and Will Mandy. 2019. “The Prevalence of Autistic Traits in a Homeless Population.” Autism 23 (3): 665–676. doi:10.1177/1362361318768484.

- Clancy, Ray. 2019. ‘Oxford Named as Least Affordable City to Buy a House in the UK’. 8 February. https://www.propertywire.com/news/uk/oxford-named-as-least-affordable-city-to-buy-a-house-in-the-uk/.

- Doherty, Gerard. 2020. “Prejudice, Friendship and the Abuse of Disabled People: An Exploration into the Concept of Exploitative Familiarity (‘Mate Crime’).” Disability & Society 35 (9): 1457–1482. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.1688646.

- Evans, Rebecca. 2011. The Life We Choose: Shaping Autism Services in Wales. Cardiff: National Autistic Society.

- Fardella, Michelle A., Priscilla Burnham Riosa, and Jonathan A. Weiss. 2018. “A Qualitative Investigation of Risk and Protective Factors for Interpersonal Violence in Adults on the Autism Spectrum.” Disability & Society 33 (9): 1460–1481. doi:10.1080/09687599.2018.1498320.

- Fitzpatrick, Suzanne, Beth Watts, Hal Pawson, Glen Bramley, Jenny Wood, Mark Stephens, and Janice Blenkinsopp. 2021. The Homelessness Monitor: England 2021. Crisis. https://www.crisis.org.uk/media/244702/crisis-england-monitor-2021.pdf.

- Flaherty, Jan, and Elisabeth Garratt. under review. ‘Life History Mapping: Exploring Journeys into and through Housing and Homelessness’. Still under review, by Qualitative Research.

- Forster, Samantha, and Amy Pearson. 2020. “‘Bullies Tend to Be Obvious’: Autistic Adults’ Perceptions of Friendship and the Concept of ‘Mate Crime’.” Disability & Society 35 (7): 1103–1123. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.1680347.

- Garratt, Elisabeth, and Jan Flaherty. 2020. Homelessness in Oxford: Risks and Opportunities across Housing and Homeless Transitions. Oxford: Centre for Social Investigation.

- Garratt, Elisabeth, Jan Flaherty, and Amy Barron. 2021. “Life Mapping.” In Methods for Change: Impactful Social Science Methodologies for 21st Century Problems, edited by A. L. Browne Amy Barron, Ulrike Ehgartner, Sarah Marie Hall, Laura Pottinger, and J. Ritson. Manchester: Aspect & The University of Manchester. Manchester.

- Gauntlett, David. 2007. Creative Explorations: New Approaches to Identities and Audiences. London: Routledge.

- Gauntlett, David, and Peter Holzwarth. 2006. “Creative and Visual Methods for Exploring Identities.” Visual Studies 21 (1): 82–91. doi:10.1080/14725860600613261.

- Glasgow City Council. 2010. ‘A Practical Guide for Registered Social Landlords: Housing and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)’. Glasgow City Council. http://onlineborders.org.uk/sites/default/files/asdborders/files/PracticalGuideforRSLsHousingASDmarch10.pdf.

- Goodley, Dan, and Katherine Runswick-Cole. 2011. “The Violence of Disablism.” Sociology of Health & Illness 33 (4): 602–617. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01302.x.

- Goodley, Dan, Rebecca Lawthom, and Katherine Runswick-Cole. 2014. “Dis/Ability and Austerity: Beyond Work and Slow Death.” Disability & Society 29 (6): 980–984. doi:10.1080/09687599.2014.920125.

- Grandin, Temple. 2009. “How Does Visual Thinking Work in the Mind of a Person with Autism? A Personal Account.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1522): 1437–1442. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0297.

- Grant, Paula. 2017. “Investigating the Factors That Contribute to Unstable Living Accommodation in Adults with a Diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorder.” PhD thesis, University of East London.

- Gray, Kylie M., Caroline M. Keating, John R. Taffe, Avril V. Brereton, Stewart L. Einfeld, Tessa C. Reardon, and Bruce J. Tonge. 2014. “Adult Outcomes in Autism: Community Inclusion and Living Skills.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44 (12): 3006–3015. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2159-x.

- Hirvikoski, Tatja, and My Blomqvist. 2015. “High Self-Perceived Stress and Poor Coping in Intellectually Able Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Autism 19 (6): 752–757. doi:10.1177/1362361314543530.

- Hodge, Nick. 2005. “Reflections on Diagnosing Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Disability & Society 20 (3): 345–349. doi:10.1080/09687590500060810.

- Hollomotz, Andrea. 2018. “Successful Interviews with People with Intellectual Disability.” Qualitative Research 18 (2): 153–170. doi:10.1177/1468794117713810.

- Homeless Link. 2014. “The Unhealthy State of Homelessness: Health Audit Results 2014.” London: Homeless Link. https://www.homeless.org.uk/sites/default/files/site-attachments/The%20unhealthy%20state%20of%20homelessness%20FINAL.pdf.

- Homeless Link. 2015. “Autism and Homelessness: Briefing for Frontline Staff.” Homeless Link. https://www.homeless.org.uk/sites/default/files/site-attachments/Autism%20%26%20HomelessnesOct%202015.pdf.

- Hurlbutt, Karen, and Lynne Chalmers. 2002. “Adults with Autism Speak Out: Perceptions of Their Life Experiences.” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 17 (2): 103–111. doi:10.1177/10883576020170020501.

- James, Ian Andrew, Elizabeta Mukaetova-Ladinska, F. Katharina Reichelt, Ruth Briel, and Ann Scully. 2006. “Diagnosing Aspergers Syndrome in the Elderly: A Series of Case Presentations.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 21 (10): 951–960. doi:10.1002/gps.1588.

- Jones, Jennifer L., Kami L. Gallus, Kacey L. Viering, and Lauren M. Oseland. 2015. “‘Are You by Chance on the Spectrum?’ Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder Making Sense of Their Diagnoses.” Disability & Society 30 (10): 1490–1504. doi:10.1080/09687599.2015.1108902.

- Kargas, Niko, Kathryn M. Harley, Amanda Roberts, and Stephen Sharman. 2019. “Prevalence of Clinical Autistic Traits within a Homeless Population: Barriers to Accessing Homeless Services.” Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless 28 (2): 90–95. doi:10.1080/10530789.2019.1607139.

- Lai, Meng-Chuan, and Simon Baron-Cohen. 2015. “Identifying the Lost Generation of Adults with.” The Lancet Psychiatry 2 (11): 1013–1027. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00277-1.

- Lai, Meng-Chuan, Michael V. Lombardo, and Simon Baron-Cohen. 2014. “Autism.” The Lancet 383 (9920): 896–910. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61539-1.

- Loomes, Rachel, Laura Hull, and Will Mandy. 2017. “What is the Male-to-Female Ratio in Autism Spectrum Disorder? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 56 (6): 466–474. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013.

- Magiati, Iliana, Xiang Wei Tay, and Patricia Howlin. 2014. “Cognitive, Language, Social and Behavioural Outcomes in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Follow-up Studies in Adulthood.” Clinical Psychology Review 34 (1): 73–86. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.11.002.

- May, Jon. 2000. “Housing Histories and Homeless Careers: A Biographical Approach.” Housing Studies 15 (4): 613–638. doi:10.1080/02673030050081131.

- McCabe, Allyssa, Ashleigh Hillier, and Claudia Shapiro. 2013. “Brief Report: Structure of Personal Narratives of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 43 (3): 733–738. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1585-x.

- McCulloch, D. C. 2015. “Analysing Understandings of “Rough Sleeping”: Managing, Becoming and Being Homeless.” PhD thesis, The Open University.

- McMordie, Lynne. 2021. “Avoidance Strategies: Stress, Appraisal and Coping in Hostel Accommodation.” Housing Studies 36(3): 380–396. doi:10.1080/02673037.2020.1769036.

- Mcnaughton Nicholls, Carol. 2009. “Agency, Transgression and the Causation of Homelessness: A Contextualised Rational Action Analysis.” European Journal of Housing Policy 9 (1): 69–84. doi:10.1080/14616710802693607.

- MHCLG. 2019a. Homelessness Code of Guidance for Local Authorities. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government.

- MHCLG. 2019b. ‘Rough Sleeping Statistics England Autumn 2018: Tables 1, 2a, 2b and 2c’. 31 January 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-homelessness#rough-sleeping-tables.

- Milton, D. E. M. 2012. “On the Ontological Status of Autism: The “Double Empathy Problem.” Disability & Society 27 (6): 883–887. doi:10.1080/09687599.2012.710008.

- Milton, D., and Mike Bracher. 2013. “Autistics Speak but Are They Heard?” Medical Sociology Online 7 (2): 61–69.

- Milton, D. E. M., and Tara Sims. 2016. “How is a Sense of Well-Being and Belonging Constructed in the Accounts of Autistic Adults?” Disability & Society 31 (4): 520–534. doi:10.1080/09687599.2016.1186529.

- National Autistic Society. 2016. “The Autism Employment Gap.” https://www.autism.org.uk/get-involved/media-centre/news/2016-10-27-employment-gap.aspx.

- Nicolaidis, Christina, Dora M. Raymaker, Elesia Ashkenazy, Katherine E. McDonald, Sebastian Dern, Amelia Ev Baggs, Steven K. Kapp, Michael Weiner, and W. Cody Boisclair. 2015. “‘Respect the Way I Need to Communicate with You’: Healthcare Experiences of Adults on the Autism Spectrum.” Autism 19 (7): 824–831. doi:10.1177/1362361315576221.

- ONS. 2020. “Deaths of Homeless People in England and Wales: 2019 Registrations.” 14 December 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsofhomelesspeopleinenglandandwales/2019registrations.

- Pagler, Jane. 2011. Autistic Spectrum Disorder: A Guide for Homelessness Practitioners and Housing Advice Workers’. WAG10-12024. Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government. https://www.asdinfowales.co.uk/resource/e_q_110324asdhomelesspracen.pdf.

- Pellicano, Elizabeth, Adam Dinsmore, and Tony Charman. 2014. “What Should Autism Research Focus upon? Community Views and Priorities from the United Kingdom.” Autism 18 (7): 756–770. doi:10.1177/1362361314529627.

- Portway, Suzannah M., and Barbara Johnson. 2005. “Do You Know I Have Asperger’s Syndrome? Risks of a Non-Obvious Disability.” Health, Risk, and Society 7 (1): 73–83. doi:10.1080/09500830500042086.

- Preece, Jenny, Elisabeth Garratt, and Jan Flaherty. 2020. “Living through Continuous Displacement: Resisting Homeless Identities and Remaking Precarious Lives.” Geoforum 116: 140–148. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.08.008.

- Pritchard, Colin. 2010. An Evaluation of the Devon Individualised Budget Project to Encourage Rough Sleepers into Accommodation. Exeter: Exeter City Council.

- Ravenhill, Megan. 2008. The Culture of Homelessness. London: Routledge.

- Raymaker, Dora M., Katherine E. McDonald, Elesia Ashkenazy, Martha Gerrity, Amelia M. Baggs, Clarissa Kripke, Sarah Hourston, and Christina Nicolaidis. 2017. “Barriers to Healthcare: Instrument Development and Comparison between Autistic Adults and Adults with and without Other Disabilities.” Autism 21 (8): 972–984. doi:10.1177/1362361316661261.

- Runswick-Cole, Katherine. 2014. “‘Us’ and ‘Them’: The Limits and Possibilities of a ‘Politics of Neurodiversity’ in Neoliberal Times.” Disability & Society 29 (7): 1117–1129. doi:10.1080/09687599.2014.910107.

- Runswick-Cole, Katherine, and Dan Goodley. 2011. “Big Society: A Dismodernist Critique.” Disability & Society 26 (7): 881–885. doi:10.1080/09687599.2011.618743.

- Ryder, Morag. 2017. “The Characteristics of Homeless Adults with Autistic Traits.” PhD thesis, University College London.

- Sappok, Tanja, Manuel Heinrich, and Lisa Underwood. 2015. “Screening Tools for Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Advances in Autism 1 (1): 12–29. doi:10.1108/AIA-03-2015-0001.

- Sheridan, Joanna, Kerry Chamberlain, and Ann Dupuis. 2011. “Timelining: Visualizing Experience.” Qualitative Research 11 (5): 552–569. doi:10.1177/1468794111413235.

- Söderström, Johanna. 2020. “Life Diagrams: A Methodological and Analytical Tool for Accessing Life Histories.” Qualitative Research 20 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1177/1468794118819068.

- Stavropoulos, Katherine Kuhl-Meltzoff, Yasamine Bolourian, and Jan Blacher. 2018. “Differential Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: Two Clinical Cases.” Journal of Clinical Medicine 7 (4): 71. doi:10.3390/jcm7040071.

- Stone, Beth. 2017. “Talking about Homelessness: Engaging Autistic People in Narrative Methods.” Unpublished MSc thesis, Bristol: University of Bristol.

- Stone, Beth. 2019. “‘The Domino Effect’: Pathways in and out of Homelessness for Autistic Adults.” Disability & Society 34 (1): 169–174. doi:10.1080/09687599.2018.1536842.

- Thomas, David R. 2006. “A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data.” American Journal of Evaluation 27 (2): 237–246. doi:10.1177/1098214005283748.

- Welsh Government. 2019. “Autism: A Guide for Practitioners within Housing and Homelessness Services.” https://autismwales.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Autism_A-Guide-for-Practitioners-within-Housing-and-Homelessness-Services_Eng.pdf.

- WHAT. 2016. Detailed Survey Findings Oct 2016. London: Westminster Homeless Action Together.