Abstract

Normative images of disability portray disabled people as ‘supercrips,’ victims, or symbols. These forms of representation, which oversimplify disability and demand narrative predictability, resemble ‘romantic’ norms of governance as described by Bonnie Honig. Offering an alternative, Honig translates the ‘female gothic’ literary genre into a ‘gothic subjectivity’ in which political subjects are ‘neither solely grateful nor perpetually disaffected’ within various ‘sites of belonging’ such as governing bodies, authority figures, and the self (Beltràn 2015, 102). I propose that disability is one such ‘site of belonging’ which would benefit from a gothic lens, as exemplified by Riva Lehrer’s portraiture. In contrast to the norm, a gothic imagining of disability celebrates disability without romanticizing it, presents disabled people as self-determined subjects rather than objects, and develops political significance without rhetorical exploitation. Thus, a ‘gothic disability’ may reject prescriptive narratives of ableism and facilitate the formation of a complex and liberatory disabled subjectivity.

Points of interest

Popular images of disabled people depict disabled people as ‘abnormal’ and nondisabled people as ‘normal’. These images are intended for a nondisabled audience and oversimplify disability into something that is completely good or completely bad.

These images resemble ‘romantic’ stories from classic books and fairy tales in which people and relationships are completely good or completely bad and certain types of characters predictably have more power than others.

On the other hand, characters in ‘gothic’ stories, specifically those with supernatural elements and female heroines like Jane Eyre and Rebecca, are both good and bad, normal and abnormal, and powerful and powerless.

In contrast to popular images, disabled artist and author Riva Lehrer creates portraits of disabled people that resemble ‘gothic’ stories more than ‘romantic’ ones. They represent disability as complicated and prioritize the points of view of disabled people.

My first monster story was Frankenstein… I waited for his graceless body, his halting gait and cinder-block shoes. I could recognize the operating room where he was born. I knew he was real, because we were the same—everything that made him a monster made me one, too.

Riva Lehrer, Golem Girl: A Memoir

Introduction

In ‘Toward a Rhizomatic Model of Disability’, artist and activist Petra Kuppers writes:

Disability is a slippery word that holds nightshade and sunlight, a concept that grows above ground, in our disability culture politics, and below, in the privacy of the disarticulation of pain, of isolation, of the lived reality of social and physical oppression. (2009, 225)

What lies in this no man’s land between pride above and pain below? How might we imagine such a slippery concept of disability, one which inhabits both realms? In this paper, I hope to offer one such multi-faceted imagining by examining narrative and visual representations of disability through the lens of Bonnie Honig’s theory of gothic subjectivity. I argue that Honig’s theory offers the liberatory capacity for an imagining of disability that may hold both ‘nightshade’ and ‘sunlight’, and that a manifestation of this newfound gothic imagining may be found in Riva Lehrer’s portraits of disabled people.

Honig’s theory translates the female gothic literary genre into a potential way of being in which democratic subjects may take up a ‘gothic subjectivity’ that is defined by the ability to be ‘neither solely grateful nor perpetually disaffected’ within various ‘sites of belonging’ such as the nation, governing bodies, authority figures, and their own identities (Beltràn Citation2015, 102). Subjectivity, for our purposes, may be understood as the subjective lens through which individuals relate to these sites—as in how a nation’s ‘subjects’ relate to it. Honig offers gothic subjectivity as an alternative to the ‘romantic’ norm, which may be defined by its demand for unambiguously amorous relationships between subjects and their various sites of belonging (Honig Citation2009, 108).

I propose that disability is one such site that may benefit from the capaciousness of a gothic subjectivity, particularly insofar as disabled subjectivities are shaped by socially dominant visual and narrative representations. Though visual and literary depictions of disability may be created with nondisabled viewers in mind, they are also sites of identity formation for disabled people (Hevey Citation1993) and thus for the formation of disabled subjectivities—defined as ‘the condition not only of identifying as disabled but also of perceiving the world through a particular kind of lens’ (Adams, Reiss, and Serlin Citation2015, 8). Normative representations of disability resemble what Honig describes as prescriptive romantic norms. As taxonomized by disability studies scholar Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, who looks specifically at the aesthetics of modern American photography, normative ‘visual rhetorics of disability’ present people with disabilities only as ‘supercrips’, victims, or symbols, options which preclude a spacious or even respectful imagining of disability for those who consume these representations—people with disabilities included.

To examine the shortcomings of these options and explore gothic subjectivity as an alternative framework through which people with disabilities may both be represented and represent themselves, I turn to visual depictions of disability and the narratives they represent. First, I argue that Rosemarie Garland-Thomson’s visual rhetorics of disability may be read as manifestations of Honig’s romantic norms. Second, I explore the gothic genre’s relationship to disability and Honig’s translation of the genre into a framework for democratic participation and ways of being. Finally, I analyze visual depictions of disability in the work of Riva Lehrer, a Chicago-based, disabled artist and writer, as manifestations of the liberatory possibility of a gothic representation and expression of disability.

Lehrer is widely acclaimed for her arresting technical skill as well as her attentiveness to the autonomy and complexity of the disabled artists and activists she portrays (Ware Citation2008). Lehrer works collaboratively with her ‘subjects’, and the impact of her methodology is felt by many. Petra Kuppers writes of her work, ‘Riva Lehrer is a poet of image and word, a US crip culture artist in whose delicate painting many of us have seen crip culture transformed’ (2008). Lehrer’s portraiture is a distinct alternative to normative images of disability, and this is intentional. In her words, ‘the collaborative method aims to counter the coercive tradition of pictures of disabled people; our public mirrors have offered little but specimens, monsters, and freaks seen by the eye of normality’ (Lehrer as quoted in Ware Citation2008). In tandem with resisting the oppressive depiction of such ‘specimens, monsters, and freaks’, Lehrer frequently identifies tenderness and personal connection to these same figures in her writing, and her portraits also employ aspects of the supernatural and mythical in bringing to fruition an imaginative ‘crip world’ (Kuppers Citation2008). Despite these elements’ resonance with the gothic genre, Lehrer’s work has not been explicitly related to a gothic aesthetic or literary tradition. Here, I explore how Lehrer’s work reflects gothic motifs and how its political meaning enacts Honig’s envisioning of a ‘gothic subjectivity’.

In this paper, I draw my definition of disability from the spacious and inclusive efforts of Sins Invalid, a performance project at the origins of the Disability Justice Movement. In their ‘10 Principles of Disability Justice’, the group states that a ‘commitment to cross-disability solidarity’ includes:

people with physical impairments, people who are sick or chronically ill, psych survivors and people with mental health disabilities, neurodiverse people, people with intellectual or developmental disabilities, Deaf people, Blind people, people with environmental injuries and chemical sensitivities, and all others who experience ableism and isolation that undermines our collective liberation. (Sins Invalid (Organization) Citation2019, 25)

A system that places value on people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, intelligence, excellence and productivity. These constructed ideas are deeply rooted in anti-Blackness, eugenics, colonialism and capitalism. This form of systemic oppression leads to people and society determining who is valuable and worthy based on a person’s appearance and/or their ability to satisfactorily [re]produce, excel and ‘behave’. (Lewis Citation2020)

Finally, I’d like to include a note on language. Though I identify with chronic illness and disability myself, I use the pronoun ‘they’ rather than ‘we’ to refer to disabled people in this paper because I can represent only my own disabled subjectivity and do not wish to collapse the many distinct experiences of disability into one voice.

Romance and visual genres of disability

In Democracy and the Foreigner, Bonnie Honig argues that relationships between political subjects and their governing bodies are most normatively understood as (and prescribed to be) ‘happy-ending love stories’ in which, pending predictable and finite obstacles, ‘the right match is made and the newly wed couple is sent on its way to try to live happily ever after’ (2009, 109). Honig tracks this norm through ‘classic texts of Western political culture’ as well as ‘popular and high cultural stories’ which range from The Book of Ruth to The Wizard of Oz (2,3). In these stories, romantic demands take shape in characters’ relationships to each other as well as to the institutions that govern them. Honig’s analysis, as well as the examples that I draw from Garland-Thomson’s work, are based in American and European contexts. Thus, their ‘normative’ nature as discussed in this paper refers to their dominance in these particular spheres. Though a discussion of the ways in which romantic norms of disability reach outside of American and European contexts is beyond the scope of this paper, we may understand that insofar as these norms are entangled with ableism, they are also, as quoted above, ‘deeply rooted in anti-Blackness, eugenics, colonialism and capitalism’ and thus exert power on a global scale. Furthermore, the metaphors of subjugation enacted by images of disability resonate with those used to further colonial imaginings of the Global South (Shakespeare Citation1994, 288).

Honig understands the demands of romantic norms to exert pressure not only on relationships between subjects and governments but on relationships to various personal and political sites of belonging. Romantic norms demand that these relationships, whatever their nature, culminate in a successful union—whether it be between a citizen and their nation, two parties in a social contract, or a person and their own sense of belonging. The romantic genre’s emphasis on achieving this successful union shapes the conventions of its narratives, which climax at the formation of the union and end before the struggles of an ongoing relationship even begin. In this way, the relationship is kept pure so that the site of belonging may remain idealized. Honig posits that this ‘insistence on total identification with an idealized object […] tends to drive the subject to split the beloved object into two (the good object and the bad) and to defend the former against the now externalized threat of the latter’ (2009, 117). In other words, in order to maintain any site of belonging as a ‘good object’, existing negativity must be projected elsewhere. In the case of the nation-state, Honig argues, this manifests as scapegoating foreign figures for the failings of the state so that the state may be blameless.

One may read normative visual representations of disability as a manifestation of these prescribed elements of romance, particularly as these representations are described in Rosemarie Garland-Thomson’s ‘Seeing the Disabled: Visual Rhetorics of Disability in Popular Photography’. Garland-Thomson examines visual representations of disability as they appear in American photography and organizes them into four genres based on their rhetorical use of disability: wondrous, sentimental, exotic, and realistic. Garland-Thomson understands these genres as ‘rhetorics’ insofar as they mobilize the disabled body as a tool for ‘contracting, instructing, or assuring some aspect of an ostensibly nondisabled viewer’ (2001, 340). This use of images of disabled people exemplifies their wider purpose ‘within cultural representation’ as described by Shakespeare: in literature, he writes, ‘it is not the disabled person themselves that the author is concerned with, as subjects, but the disabled person as vehicle, as object’ (1994, 285). As a result, ‘disabled people become ciphers for those feelings, processes or characteristics with which non-disabled society cannot deal’ (287).

Garland-Thomson also argues that because disabled people in ‘Western’ culture are considered ‘to-be-looked-at’ rather than ‘to-be-embraced’, the visual is the predominant mode in which disability is defined in Western modernity (2001, 340). Thus, both contributing to and reflecting society’s pool of narratives about disability, these images ‘construct the object they represent as they depict it’ (335–6). The particular mechanism by which each image constructs its narrative of disability is what places it into the wondrous, sentimental, exotic, or realistic genre. Moreover, I argue that all four categories also reflect genre conventions of the romantic. In particular, they exert the demands of romantic norms on disabled subjects’ relationships to both nondisabled viewers and their own disabled identities.

First, I will examine the ways in which normative images of disability manifest romantic tropes by prioritizing the seduction of the viewer over the perspective of the disabled subject. Visuals in the wondrous genre represent people with disabilities as ‘supercrips’ who may achieve miraculous accomplishments, but only due to exceptional individual effort (sans accessibility measures) and the ability to externalize their disability from themselves. As an example of the wondrous, Garland-Thomson includes a photo of a person who is a wheelchair-user scaling the side of a cliff. As she comments, ‘the photographic composition literally positions the viewer to look up in awe at the climber dangling in her wheelchair’ (Garland-Thomson Citation2001, 341). However, the rhetorical task of this genre is not to empower the disabled subject by placing them above the viewer but to confirm the nondisabled onlooker’s normality while solidifying the disabled person’s illegibility.

While wondrous images place disabled subjects above the viewer, ‘sentimental’ visuals encourage viewers to look down on disabled people. In this genre, people with disabilities are presented as objects to receive pity from nondisabled viewers and whose suffering may only be alleviated by death or cure. This positioning empowers the viewer to see themselves as a savior. If people with disabilities are made to be fainting damsels in distress, the viewer is made to be their nondisabled hero. In a poster for the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis included by Garland-Thomson, a young white boy thanks the viewer for their presumed contribution to his restored walking ability: ‘your dimes did this for me!’ (2001, 342). Such images use the sentimental visual rhetoric of disability in order to elevate the viewer to parent and savior while imagining the disabled ‘as passive and incapable people, objects of pity and of aid’ (Shakespeare Citation1994, 287–8). This relative positioning of empowered nondisabled subject to disempowered disabled object writes into being a relationship in which nondisabled viewers may play the hero role by donating to cure-oriented organizations which have rarely even been led by disabled people. As a result, nondisabled viewers’ harmful understandings of disability become more firmly entrenched, and material resources continue to be rerouted away from disabled people (Doddington, Jones, and Miller Citation1994).

The ‘exotic’ genre as presented by Garland-Thomson posits that people with disabilities are so utterly different as to be illegible apart from being frightening, fascinating, or both. This genre is particularly entangled with racism and colonialism, as disabledness and non-whiteness are often wielded in tandem. Images in this genre replicate the tradition of displaying non-normative bodies as freakish. In Medical Apartheid, Harriet Washington discusses Joyce Heth’s experience being displayed by circus legend P.T. Barnum as the supposed Black ‘mammy’ to President George Washington. The author describes Heth’s body to be ‘gnarled by a breathtaking decrepitude that simultaneously thrilled and repelled’ and claims that onlookers ‘consistently identified [her body] both with Africa and with death’ (Citation2008, 86). It is precisely this combination that seduces the onlooker in the exotic genre, for fetishization flattens the relationship between disabled subject and viewer so that the viewer might desire the subject’s disability (or, more broadly, their difference) without desiring the person themselves. Furthermore, such exotification denies disabled people and others against whom it is wielded access to the ‘mundane world’ of ‘economic and political power’ (Garland-Thomson Citation2001, 341). This exclusion from such economic and political power works as a mechanism of ableism and results in the material and social subjugation of exotified people. As Shakespeare writes, we may also connect the exotic [exemplified by pornography] and the sentimental [exemplified by charity] by identifying their shared gaze upon ‘the body, which is passive and available’ and manipulation of the viewer ‘into an emotional response: desire, in the case of pornography, fear and pity in the case of charity advertising’ (1994, 288).

Garland-Thomson presents the wondrous, sentimental, and exotic genres as the most exploitative in their use of disability to manipulate (and, as I argue, to seduce) the viewer. However, I find that the fourth genre—the realistic—similarly romances the viewer. Garland-Thomson claims that this genre most effectively reaches toward ‘equality’ for people with disabilities because ‘realism avoids differentiation and arouses identification’ in order ‘to routinize disability, making it seem ordinary’ (2001, 363). However, the narrative offered by this visual genre still centers the goal of affecting nondisabled minds and attitudes and, as a result, continues to displace the subjectivity of disabled people. As Garland-Thomson acknowledges of a ‘realistic’ photo depicting an ‘African amputee’ (his country of origin is not included), the image still ‘marks the disabled man as the person the viewer does not want to be’ (346). Thus, the image remains a metaphor and projection of nondisabled fear of losing ‘able-bodiedness’ (Hevey Citation1993, 426) and in its receptions of such projections, collapses the disabled person into ‘object’ (Shakespeare Citation1994, 287).

Via these mechanisms, dominant visual genres of disability romance the viewer and displace the disabled subject from their very own portrait. Thus, these images preclude the possibility for the formation of a disabled subjectivity and perpetuate the understanding that ‘the cripple [sic] is the creature who has been deprived of his [sic] ability to create a self’ (Kriegel as quoted in Shakespeare Citation1994, 285). In turn, a dominant understanding of disability refuses to acknowledge, as described by disabled writer and activist Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, the fact that ‘disabled people could know things that the abled don’t. That we have our own cultures and histories and skills’ (Citation2018, 69). This refusal echoes Talila ‘TL’ Lewis’ definition of ableism as one which ‘places value on people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, intelligence, excellence and productivity’ and systematically denies disabled people such value (Lewis Citation2020). In an effort to elicit reactions from nondisabled viewers, normative representations of disability abandon the opportunity for the formation of a disabled subjectivity that might actually manifest the perspective of the person and community being ‘represented’.

Furthermore, these visual genres of disability not only romanticize the relationship between disabled subject and viewer but also construct disabled people’s relationships to their own disabilities according to romantic conventions. In wondrous, sentimental, and exotic representations, either the person or their disability might be desired or romanced but never both at once. This speaks to Honig’s claim, mentioned at the beginning of this section, that in order for relationships between subjects and sites of belonging to obey the demands of romantic norms, the site of belonging must be split ‘into two (the good object and the bad)’, with the bad becoming an ‘externalized threat’ (Honig Citation2009, 117). Wondrous, sentimental, and exotic visuals separate the disabled subject from their disability and externalize disability from the self as a result.

The wondrous genre, for example, finds its romantic climax in the ability of the ‘supercrip’ to complete some miraculous task. However, this happy ending is dependent upon disability playing the role of externalized threat. We see this rhetoric in action in disabled writer and activist Eli Clare’s account of an advertisement that claims Whoopi Goldberg ‘overcaem’ her dyslexia (the misspelling is a dyslexia pun, described as ‘dismissive and stereotypical’ by Clare) with nothing but ‘hard work’ (Citation2017, 8). In response, Clare asks how the ‘dominating, subsuming, defeating’ that is required to ‘overcome’ could even be possible in the case of disability: ‘how could I dominate my shaky hands, defeat my slurring tongue, even if I wanted to? How could Whoopi Goldberg subsume her dyslexia even as words waver and reverse on the page?’ (9). Despite the fact that disability is so internal as to be part of one’s bodymind, the wondrous genre demands that it must be externalized and defeated for the resolution of the story. In the sentimental genre, the salvation offered by the happy union of damsel and hero also casts disability as the villain that must be conquered. And, if the hero offers a cure, this salvation might go so far as to eradicate disability. Finally, in the exotic genre, fetishization prompts the viewer to desire the subject’s disabled body without desiring the disabled person themselves. By separating disabled people from their disability, these images relieve viewers from their obligation to engage with disabled people beyond simply viewing them.

On the other hand, rather than dramatizing and externalizing disability, the realistic genre minimizes it. ‘Realistic’ depictions of disability seek to romance the viewer by emphasizing the claim that disability is simply ‘normal’ and by downplaying disabled people’s subjective or cultural differences from the nondisabled. In addition to precluding the formation of a subjective disabled lens, this rhetorical tactic also steers away from honest engagement with the body and its pain. This same tendency has been critiqued in the social model of disability and post-structuralist approaches to disability, which locate the disabling factor of bodily difference in external conditions and abuses of nondisabled power rather than embodied experience (Adams, Reiss, and Serlin Citation2015; Feely Citation2016). Though the social model does the essential work of identifying extensive material needs of disabled people that are unmet by the state and society, it also romanticizes disability by limiting ‘bad object’ status to the state and society and leaving disability itself to be only a ‘good object’. Furthermore, in an attempt to reject the over-individualization of disability, the social model neglects ‘culture, representation and meaning’ and thus misses major modalities of ableism (Shakespeare Citation1994, 283). Post-structuralist approaches, on the other hand, purposefully dissect individual experience, representation, and cultural discourse but neglect material power (Feely Citation2016).

Alternatively, imaginings of disability would benefit from holding both embodied pain and liberation from material exclusion. As Martha Stoddard Holmes writes, ‘theorizations of embodiment that bypass the reality of bodies in pain are neither realistic in attending to the pain experiences of many people with disabilities nor effective in promoting social justice’ (Citation2015, 134). A more complete imagining of disability requires a reconciliation of the sometimes painful material reality of disability with the value, humanity, and obvious fullness of disabled life. I argue that a gothic subjectivity has the potential to offer this: the ability to be equal while also being different, and maybe even while in pain.

The gothic genre, gothic subjectivity, and gothic disability

Ruth Anolik, in Demons of the Body and Mind: Essays on Disability in Gothic Literature, describes the gothic genre as an ‘antidote’ to the Enlightenment and its lasting impact on normative Western demands for ‘defining conceptual categories’ and ‘rational light’ (2010, 6). The gothic genre lives within ‘the shadowy, mysterious and unknowable space inhabited by the inhumanly unknowable Other’ (2). This Other, living in the shadows, often takes the form of somebody whose bodymind diverges from the norm, and as a result, the motif of disability becomes a metonym for the monstrous and threatening (Costa Citation2019).

Considering this history, how could a genre which has so firmly linked bodily difference to shadows and fear be a site of liberation for disability? Indeed, relegating difference to the horrific has long contributed to the marginalization of people with disabilities as well as dark-skinned people, gender non-conforming people, and others with ‘undesirable’ bodies. However, while gothic literary conventions do make this linkage, they also complicate it by ‘present[ing] human difference as monstrous, and then, paradoxically, subvert[ing] the categories of exclusion to argue for the humanity of the monster’ (Anolik Citation2010, 2). However, even this allowance risks merely mobilizing disability for the metaphorical benefit of telling a story about normalcy. What truly holds potential for a more complex imagining of disability within the gothic is its ‘distrust of confining categories and boundaries and of the powerful authorities who create them’ (6). In her recent memoir, Riva Lehrer describes her body’s refusal of these very boundaries, and in her case, the doctors who sought to create them: ‘The day I was born I was a mass, a body with irregular borders. The shape of my body was pared away according to normal outlines, but … my body insisted on aberrance’ (Citation2020, xv). Like Lehrer, gothic characters, creatures, and settings demonstrate the potential for bottom-up determination and rejection of the borders between human/monster, dis/ability, and ab/normalcy by disobeying boundaries and those in power who might define them.

Though it is certainly complicated if not dangerous to align an imagining of disability with the fearful and uncanny, there is potential in the gothic for a reimagining of disability which is neither only horrific nor only romantic. This is particularly true with a focus on what representations of disability might mean for disabled subjects rather than nondisabled viewers. Anolik writes that gothic narratives ‘reflect a doubled and conflicted set of anxieties: fear of the non-normative human Other’ and ‘fear of social authority that excludes human difference’ (Citation2010, 6). While one might fear that a gothic depiction of disability risks strengthening the nondisabled viewer’s association of disability with the monstrous, this fear should not disallow people with disabilities from expressing their disabled selves in a gothic sense. Just as gothic characters refuse definition and demand fluidity through unknowability (Costa Citation2019), so might disabled people demand the unknowability of their disability by their nondisabled counterparts. Coupled with resistance to the power structures and social authority that enact ableism and the exclusion of disabled people, an identification with the gothic, the monstrous, and the shadows may allow people with disabilities and representations of disability to reject oppressive norms, lay claim to self-determination, and engage more fully with difference.

Honig mines this politically salient potential from the female gothic genre, though she offers it more broadly to all governed subjects rather than just to disabled ones. Critics debate which authors and stories the female gothic subgenre should include, as well as whether it primarily reinforces or primarily critiques the oppression of the women it depicts (Wallace and Smith Citation2009). However, while the heroines of the female gothic are subject to controlling men and exclusionary political norms, they also resist these arms of patriarchy—in part via expressing ambivalence toward them. Honig argues that female gothic heroines’ ambivalence is ‘social and political rather than strictly familial’ and should be understood as resistance to exclusionary political circumstance as well as individual patriarchal relationships (2009, 111).

Though Honig’s theory of gothic subjectivity is not in itself concerned with disability, it may be employed as a translation of what the gothic literary genre has to offer as a framework for disabled people’s participation in society, identity, and other ‘sites of belonging’, as reflected in and shaped by visual and narrative representations. I turn, then, to what makes a gothic subjectivity. In Democracy and the Foreigner, Honig takes up the female gothic genre as an alternative lens for reading democratic participation. According to her, citizens’ relationships to their governing bodies are prescribed by Western democratic theory, literature, and film, to be normative romantic ones, replete with metaphors of happy marriages interrupted only by momentary marital squabbles. These metaphors ultimately serve as demands for unswerving patriotism and subservience. Alternatively, Honig encourages democratic participants forming relationships to governing bodies and other sites of belonging to employ the ambivalence and complexity of a gothic lens.

A central feature of female gothic literature is its heroines’ ambivalent relationships to authority and belonging, often manifested through husbands and fathers. In contrast to romantic narratives, which end at the initial formation of a union, the gothic genre’s ‘concern is with understanding the relationship and the feelings involved once the union has been formed’ (Honig Citation2009, 110). As a result, gothic stories engage with the complexities of ongoing relationships so that neither party may remain solely a ‘good’ or ‘bad object’ as prescribed by romantic norms. In addition, the gothic troubles the roles of hero and villain, which are often both embodied by the heroine’s love interest. While the romantic genre demands pure loyalty to the hero and unfettered hatred of the villain, the gothic allows for, and even assumes, that good and evil are connected if not one and the same. In the gothic, the reader, as well as the characters, are not allowed to understand each other in such simplistic or predictable ways. As Honig describes, it often ‘turns out that it is not the apparently scary foreigner but the nice man next door, meek and mild, who is the real murderer’ (119).

However, Honig reassures that this unknowability of potential threats does not preclude the gaining of power and knowledge to wield against them. While protagonists of the gothic horror genre often become helpless ‘in the face of pervasive powers that determine human fate from places beyond the reach of human agency’, female gothic heroines engage in a deep questioning of and resistance to forces which seem to control them, and they are able to gain power over these forces as a result (Honig Citation2009, 115). In fact, Honig argues that female gothic heroines’ ability to maintain both ambivalence and commitment in their relationships empowers them to gain agency through continuing to learn about and analyze those bonds. Furthermore, she extrapolates this ability to any gothic subject: she argues that armed with the tools to understand relationships with others and themselves with nuance, gothic subjects need not settle for the clearcut roles of romantic narratives. Similarly forming a gothic subjectivity, disabled people might see themselves in gothic heroines as they negotiate an ongoing process of self-discovery, resistance to ableist authority, and vulnerability to the hardships enacted by their body and society.

Importantly, however, Honig notes that female gothic heroines’ gains in power and agency do not fit a simple arc, and they come with loss as well as ongoing vulnerability. Though Honig writes that ‘the best female gothic heroines are takers’ (2009, 118) and that ‘the subjects best prepared for the demands of democracy’ are those who ‘know that if they want power they must take it’ (114), a gothic taking of power does not cleanly resolve as it might in a romantic narrative. Rather, female gothic heroines’ gains are entangled with loss and change. Looking to Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca, Honig describes the character Mrs. De Winter’s desire to be ‘‘older’ or simply ‘old’’ in order to gain ‘power and agency’ (113). Mrs. De Winter’s gains in ‘mature self-assurance’ will come at the cost of innocence and youth’s privilege. Honig contrasts this reconciling of gain and loss with the romantic convention of scapegoating, which serves to separate wins from the harms they may have required in order to narrativize such wins as purely good.

Furthermore, despite their gains in power, female gothic heroines ‘usually remain vulnerable’ and do not resolve all the questions looming in their relationships nor ‘all the secrets that haunt them’ (Honig Citation2009, 117). In this way, the gothic presents a more honest vision of agentic growth that includes incompleteness. For example, female gothic heroines’ gains in power remain intertwined with vulnerability through continued interdependence with other characters. For example, Honig notes that in Jane Eyre, Jane ‘adopts and is adopted by the Rivers family’, and it is ‘from the stage of this […] kinship that Jane marries Rochester’ (113). Rather than power and agency being dependent on individualism, the empowerment of female gothic heroines includes others. As Honig describes, from this we ‘learn the importance to independence of relations of solidarity and enacted sorrel kinship’ (113). This lesson resonates with the tenets of Disability Justice, which include the necessity of communality to independence. As Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha writes, ‘in the face of systems that want us dead, sick and disabled people have been finding ways to care for ourselves and each other for a long time’ (Citation2018, 41). The gothic offers disability a power that is both vulnerable and communal.

Demonstrating gothic subjectivity’s political applicability, Cristina Beltràn sees ‘gothic subjectivity’ operating in young DACA activists. Using Honig’s theory, Beltràn examines DACA ‘coming out’ videos, in which activists use sardonic humor, anger, and hope to ‘come out’ as DACA recipients and condemn the violence of U.S. immigration law. In these videos, DACA activists declare themselves to be ‘undocumented, unafraid, and unapologetic’ (Beltràn Citation2015, 87). The tone of the videos leads Beltràn to read their pride as a gothic rather than a romantic one. Whereas a romantic approach may employ simplified narratives of American immigration and false ‘xenophilic celebration of patriotism’, the activists express a gothic subjectivity in their relationships to identity, community, and country by demanding ‘a richer and more complex approach to membership’ (103). Beltràn’s analysis demonstrates the ability of gothic subjectivity to be a politically actionable framework through which to represent and express an identity. Furthermore, she demonstrates the usefulness of gothic subjectivity in the visual realm. The coming out videos she describes simultaneously do the work of representing an identity (and even revealing it) to an external audience while also expressing a robust version of that identity from the genuine perspective of the subject that allows for political utility alongside nuanced personal meaning.

Interpreting Riva Lehrer’s portraits of disabled activists through a gothic lens reveals a similarly productive manifestation of gothic subjectivity. Described in the next section, her portraits create imaginative representations of disabled people and their relationships to disabled identity. The portraits communicate a robust and distinct disabled subjectivity, as they successfully reject the tradition of exploiting disability as a symbol for the nondisabled viewer. In the process, they create new possibilities for the representation of disability.

Finding gothic disability in Riva Lehrer’s portraiture

In ‘Golem Girl Gets Lucky’, Riva Lehrer reflects on the iron gate that guards her home:

Iron is an ancient, eldritch charm against demons and faeries, able to divide the world of monsters from the world of men. This iron threshold marks the line between the hard-shell body I wear in the street and the soft stitched-up skin of my animal self […] The sounds of coming home—the turn of the lock, the squeak of the metal, the closing clank—are my quiet incantations for the protection of monsters. (Citation2012, 231)

Though Lehrer does not explicitly create work that expresses disability through a gothic lens, her portraits of disabled activists and the writing she pairs with them may be read as such. Like the DACA activists Beltràn discusses, Lehrer’s portrait subjects are ‘unapologetic’ and ‘unafraid’ of the identities they hold yet express the pain of their identities in a matter of fact, honest affect. As Lehrer writes in the New York Times, ‘these portraits do not ask for sympathy, or empathy, or even that viewers agree that the subjects are beautiful’ but serve as prompts ‘to daydream the life of the person before them’ (Citation2017).

One of Lehrer’s series of portraits is titled ‘Totems and Familiars’. In her artist’s statement for the collection, she explains her interest in the ‘totems and familiars’ of children’s literature. In particular, she is intrigued by hero figures. Like writers of the female gothic genre, Lehrer takes up genre conventions and troubles them. In a portrait of disabled activist Nadina La Spina, the ghost of a young girl stands behind her (Lehrer Citation2008) (). The girl has a neutral expression, empty eyes, and plays with La Spina’s bountiful curls. The ghost is La Spina’s childhood friend, who was also disabled and lived with her in the hospital. With Lehrer’s interest in ‘heroes’ in mind, we might see the young ghost as a distinctly gothic hero. Though a friend, the young girl also haunts La Spina. Lehrer writes the story of the portrait: ‘both girls were quite beautiful; visitors would say: “Oh, you’re so pretty! What a shame. What a waste.” Nadina’s friend got the message that she would always be unacceptable, and decided to commit suicide at twenty-two’ (Citationn.d.-a, ‘Nadina La Spina’). The girl stands behind La Spina as a specter of pain but also survival. Smiling with the ghost’s hands in her hair, La Spina seems comfortable holding this duality. In an interview, Lehrer echoes this relationship to ghosts: rejecting demands to paint ‘universal images’ as an art student in the 1970s, Lehrer opted for ‘the images that were haunting her’, that were ‘mutating in [her] mind’ and refusing to ‘leave [her] alone’ (Isaacs Citation1993).

Figure 1. Black and white charcoal drawing in three panels. Nadina LaSpina sits in a wheelchair in the center of the image, looking straight at the viewer. She has long, dark, wavy hair and is wearing a skirt. To her right is a semi-transparent figure with short curly hair who is wearing a dress and touching Nadina’s hair. In the right panel are three IV poles with bags that contain small dresses and in the left panel is a singular IV bag.

In her collection ‘Mirror Shards’, Lehrer paints her subjects in tandem with animalistic and monstrous imagery. Again playing with the contentious relationship of people with disabilities to beasts and monsters, Lehrer mines this tension for new potential. Resonating with the gothic desire to trouble boundaries of normal/abnormal and human/inhuman, Lehrer seeks to create something new and boundary-less as she mingles human and creature. These disabled subjects are not monsters as defined by nondisabled onlookers but something entirely their own. In Lehrer’s imagining of disability, the uncanny holds uniqueness and difference without shame.

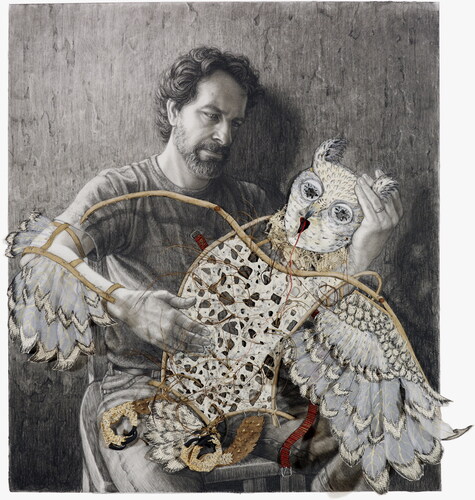

For example, in ‘Tim/Owl’, Lehrer depicts Chicago artist Tim Lowly and his relationship to his disabled daughter, Temma (Lehrer Citation2011) (). Describing the portrait, Lehrer writes, ‘my portraiture practice is based on informed consent. I was unable to ask Temma for her consent due to her impairment, so I chose instead to depict the father-and-daughter relationship’ (Citationn.d.-b, ‘Tim/Owl’). In refusing to show Temma without her consent, Lehrer keeps central to her work disabled people’s autonomy—defined by Sins Invalid as ‘independence, freedom; the ability to be self-governing, to make decisions for oneself’ (2019, 145). And, with Temma not physically present in the piece, Lehrer manages to demonstrate both Temma’s agency and opacity. Explaining her choice of animal avatar, Lehrer writes: ‘owl wisdom is complex, its messages cryptic and obscure. The Owl asks Who? Demanding that the seeker explain himself’ (Citationn.d.-b, Tim/Owl). Here, Temma is the active subject—she does the asking and demanding, even though she may be ‘cryptic’ or illegible to the nondisabled. For Lehrer, Temma’s avatar also ‘offers Tim a fragmented mask and fragile wings, in order to fully immerse himself in Temma’s endless moment’ (Citationn.d.-b, Tim/Owl). Again, she emphasizes Temma’s agency. Tim is brought into Temma’s experience only with her invitation. Furthermore, noting ‘Temma’s endless moment’, Lehrer creates space for a specific disabled subjectivity by acknowledging that Temma’s experience of time may be unique.

Figure 2. Black and white charcoal background with collaged foreground. Tim Lowly sits on a wooden chair in the center of the image in front of a textured wall. He has short wavy hair and a beard. He holds an owl figure made of glass, clay, papers, Bible pages, wire, and twigs in his lap. His left hand cradles the owl’s head, and on his right he wears a beige brace with a wing.

Temma’s visual presence in the portrait is similarly multi-faceted. She is fragile and a bit haunting, seemingly made of twigs and paper with hollow-seeming eyes and dangling red straps that connect to nothing. Yet, she is also the only part of the piece that is in color: warm creams, red, and beige. The relationships here between Temma and her father, and Temma and her disability, are gothic ones. They juggle mystery and unknowns alongside tenderness and strength.

Lehrer’s series ‘Circle Stories’ includes portraits of disabled artists, academics, and activists. To create these portraits, Lehrer set up a mutually iterative process for getting to know her subjects so that she could create ‘imagery that is a truthful representation of their experience’ (Lehrer, Citationn.d.-c, ‘Circle Stories’). She calls her method ‘circular’, involving ‘extensive interviews with each participant, in which we talk about their lives, work, and understanding of disability’ (‘Circle Stories’). Though Lehrer seeks ‘truthful representation’, her style approaches truth through metaphor and imagination rather than pure realism. The details of her subjects’ bodies are deftly painted and life-like, but they are accompanied by surreal and often uncanny elements. With this juxtaposition, the portraits blur the boundary between the real and the unreal and un-divide the uncanny from the truth.

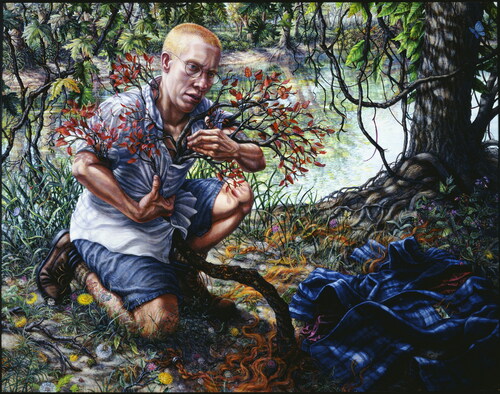

One portrait in the series depicts disabled writer and activist Eli Clare kneeling on the ground in a lush pond-scape, entangled with a gnarled tree that grows up out of the ground and into his shirt and torso (Lehrer Citation1997) (). Art critic Diane Thodos notes the complex work of the painting: ‘in it, nature and its tremendously powerful presence resolves the balance between pain and existence while affirming a wondrously regenerative meaning to life’ (Citation2004). The individual elements of the portrait are painted in a literal style, but when placed together, they form an entirely new visual world—one in which trees grow with bodies, where a bodymind with cerebral palsy (like Clare’s) is active and strong and pain mingles with beauty. Writing about the portrait, Clare himself contrasts Lehrer’s supportive and collaborative approach to representation with the oppressive gaze of others: ‘I’ve known hostile stares, curious gawking, impetuous glances that demanded I explain this body of mine’, whereas Lehrer’s artwork ‘overwhelms me, surrounds me, encourages me to fill my skin to its very edges’ (Citationn.d., ‘Portrait of Eli by Riva Lehrer’). While others have demanded Clare categorize himself within their knowable boundaries, Lehrer encourages his own self-formation, as he ‘fills’ his very own skin.

Figure 3. Acrylic painting in color. Eli Clare kneels on the left side of the image. He has buzzed orange hair, glasses, and is holding the branches of a tree that grow from the ground into his shirt. On the ground to his left is a blue plaid jacket and tendrils of orange hair. Around him is a lush landscape of water, trees, and flowers.

Lehrer’s iterative methodology and aesthetic style ensure that the subjects of her portraits are not merely depicted in the gothic genre but have the opportunity to form their own gothic subjectivities of disability. Though metaphors may play a role in their representation, the disabled artists, writers, and activists in Lehrer’s work are not two-dimensional symbols or narrative tools used to please nondisabled viewers. They are whole persons at the helm of their own formation. Lehrer writes of the subjects in ‘Circle Stories’: ‘I gave them a great deal of control over the images, because nearly all found it painful to be stared at, and I refused to replicate that pain’ (2017). Lehrer does not shy away from the pain of disability, but nonetheless works to halt its perpetuation. With balanced attention to pain and power, Lehrer’s work manifests an elegantly ambivalent and gothically beautiful disabled subjectivity.

Conclusion

Taking Bonnie Honig’s theory of political subjectivity together with the gothic genre’s complication of normative categories of bodily difference, we might imagine a disabled subjectivity that takes up the gothic lens. In Lehrer’s portraits, we see this lens take a visual form, and in her words, a narrative of identity which is not just realistic but honest and whole. On her body, Lehrer writes:

There. Is. Not. One. Inch. Of. Me. That. Is. Normal. I have a painter’s honesty: knowing that not skin, not hair, not eyes, or mouth or bone or joints or muscle or fingers or fingernails are untouched by strange variations. Monster on the outside, and monster on the inside where the bone, the muffled thump, and the secret details live. (Citation2012, 248)

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dr. Jacob Appel (Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai) for advising.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Funding

This work was supported by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai under the Patricia S. Levinson Summer Research Award.

References

- Adams, Rachel, Benjamin Reiss, and David Serlin, 2015. “Disability.” In Keywords for Disability Studies, edited by Rachel Adams, Benjamin Reiss, and David Serlin, 5–11. New York, NY: New York University.

- Anolik, Ruth Bienstock. 2010. Demons of the Body and Mind: Essays on Disability in Gothic Literature. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

- Beltràn, Cristina. 2015. “‘Undocumented, Unafraid, and Unapologetic’: Dream Activists, Immigrant Politics, and the Queering of Democracy.” In From Voice to Influence: Understanding Citizenship in a Digital Age, edited by Danielle Allen and Jennifer S. Light. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

- Clare, Eli. 2017. Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure. Durham, NC: Duke UP.

- Clare, Eli. n.d. “Portrait of Eli by Riva Lehrer.” Accessed January 3, 2021. https://eliclare.com/background/portrait.

- Costa, Stevi. 2019. “Foreword: Disability, Metonymic Disruption, and the Gothic.” Studies in Gothic Fiction 6 (1): 4–6. doi:10.18573/sgf.14.

- Doddington, K., R. S. P. Jones, and B. Y. Miller. 1994. “Are Attitudes to People with Learning Disabilities Negatively Influenced by Charity Advertising?” Disability & Society 9 (2): 207–222. doi:10.1080/09687599466780221.

- Feely, Michael. 2016. “Disability Studies after the Ontological Turn: A Return to the Material World and Material Bodies without a Return to Essentialism.” Disability & Society 31 (7): 863–883. doi:10.1080/09687599.2016.1208603.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. 2001. “Seeing the Disabled: Visual Rhetorics of Disability in Popular Photography.” In The New Disability History: American Perspectives, edited by Paul K. Longmore and Lauri Umansky. New York, NY: New York University.

- Hevey, David. 1993. “From Self-Love to the Picket Line: Strategies for Change in Disability Representation.” Disability, Handicap & Society 8 (4): 423–429. doi:10.1080/02674649366780391.

- Holmes, Martha Stoddard. 2015. “Pain.” In Keywords for Disability Studies, edited by David Serlin, Benjamin Reiss, and Rachel Adams, 2nd ed., 133–134. New York, NY: New York University.

- Honig, Bonnie. 2009. Democracy and the Foreigner. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Isaacs, Deanna. 1993. “Art People: Riva Lehrer, Body and Beyond.” Chicago Reader. September 2. https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/art-people-riva-lehrer-body-and-beyond/Content?oid=882692.

- Kuppers, Petra. 2008. “Scars in Disability Culture Poetry: Towards Connection.” Disability & Society 23 (2): 141–150. doi:10.1080/09687590701841174.

- Kuppers, Petra. 2009. “Toward a Rhizomatic Model of Disability: Poetry, Performance, and Touch.” Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 3 (3): 221–240. doi:10.1353/jlc.0.0022.

- Lehrer, Riva. 1997. Circle Stories: Eli Clare. Acrylic on Panel. https://www.rivalehrerart.com/eli-clare-1.

- Lehrer, Riva. 2008. Totems and Familiars: Nadina La Spina. Charcoal on Paper. https://www.rivalehrerart.com/nadina-la-spina.

- Lehrer, Riva. 2011. Mirror Shards: Tim/Owl. Charcoal, Glass, Clay, Papers, Bible Pages, Wire, Twigs and Collage on Schoellershammer Board. https://www.rivalehrerart.com/tim-and-temma-lowly.

- Lehrer, Riva. 2012. “Golem Girl Gets Lucky.” In Sex and Disability, edited by Robert McRuer and Anna Mollow. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Lehrer, Riva. 2017. “Where All Bodies Are Exquisite.” New York Times, August 9. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/09/opinion/where-all-bodies-are-exquisite.html.

- Lehrer, Riva. 2020. Golem Girl: A Memoir. New York, NY: One World.

- Lehrer, Riva. n.d.-a. “Nadina La Spina.” Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.rivalehrerart.com/nadina-la-spina.

- Lehrer, Riva. n.d.-b. “Tim/Owl.” Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.rivalehrerart.com/tim-and-temma-lowly.

- Lehrer, Riva. n.d.-c. “Circle Stories.” Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.rivalehrerart.com/circle-stories.

- Lewis, Talila. 2020. “Ableism 2020: An Updated Definition.” TALILA A. LEWIS (Blog). January 25. https://www.talilalewis.com/blog/ableism-2020-an-updated-definition.

- Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi. 2018. Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice. Vancouver, Canada: Arsenal Pulp Press.

- Shakespeare, Tom. 1994. “Cultural Representation of Disabled People: Dustbins for Disavowal?” Disability & Society 9 (3): 283–299. doi:10.1080/09687599466780341.

- Sins Invalid (Organization). 2019. Skin, Tooth, and Bone: The Basis of Movement is Our People, a Disability Justice Primer. 2nd ed. Berkeley, CA: Sins Invalid.

- Thodos, Diane. 2004. “Riva Lehrer: Circle Stories.” Artcritical, May 1. https://artcritical.com/2004/05/01/riva-lehrer-circle-stories/.

- Wallace, Diana, and Andrew Smith, eds. 2009. The Female Gothic: New Directions. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ware, Linda. 2008. “Worlds Remade: Inclusion through Engagement with Disability Art.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 12 (5–6): 563–583. doi:10.1080/13603110802377615.

- Washington, Harriet A. 2008. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. First Anchor Books ed. New York, NY: First Anchor Books.