Abstract

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is an ultra-rare genetic disorder characterised by intolerance to visible light. Starting in early childhood, people with EPP suffer from social isolation, impaired educational and occupational opportunities, and low quality of life. Afamelanotide is the only effective and approved therapy for EPP. In England, its cost-effectiveness is currently assessed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which in 2018 issued a negative recommendation for funding. Stakeholder organisations, including our patient organisation, submitted appeals against the recommendation, which were upheld in all possible grounds. Moreover, the appeal panel expressed concerns about whether the evaluating committee discriminated against people with EPP and suggested that it seek guidance regarding the Equality Act 2010. However, three years later, the identified issues have not been addressed and patients in England remain without treatment. Afamelanotide represents another example for the trend towards a loss of fairness in NICE decisions.

The first therapy for an ultra-rare condition

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is an ultra-rare (1:100,000) inborn error of the heme biosynthesis characterised by phototoxic burn reactions; that is, up to second-degree burn injuries of the endothelial cells surrounding the blood capillaries beneath the skin. The associated severe pain develops within minutes of exposure to sunlight and strong artificial light sources, lasts for up to 10 days and is not responsive to analgesics, not even opiates. Starting in early childhood, people with EPP avoid exposure to light, which leads to social isolation, impaired educational and occupational opportunities, mental health challenges and low quality of life (Rufener Citation1987; Rutter et al. Citation2020; Naik et al. Citation2019). Afamelanotide is an analogue of the endogenous alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone. Applied as a bimonthly, 16-mg subcutaneous slow-release implant formulation, it moderately increases skin pigmentation and has strong anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties. Tested in four multicentre randomised controlled clinical trials collectively including around 340 participants, afamelanotide is the first therapy that demonstrably prolongs the time people with EPP can spend in direct sunlight without developing pain, reduces the number and severity of the phototoxic burn reactions, and increases their quality of life (Langendonk et al. Citation2015). People with EPP consistently report that under treatment they can expose themselves for several hours per day to direct sunlight and experience a near-normalisation of all aspects of their lives (Barman-Aksözen et al. Citation2020; Falchetto Citation2020). Afamelanotide for the treatment of adult patients with EPP is approved in the European Union (December 2014), the USA (October 2019) and Australia (October 2020), and is currently available through specialised treatment centres in several European countries including Switzerland, as well as the USA and Israel.

Afamelanotide in England

Patients in England until now do not have access to the afamelanotide treatment. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) reviews the clinical benefit and cost-effectiveness of new treatments and formulates recommendations for their funding by the National Health Service (NHS), with a separate appraisal process for very rare conditions, the Highly Specialised Technologies (HST) programme. In 2016, NICE held a scoping workshop for afamelanotide (ID927), followed by two HST committee meetings and a public consultation. In May 2018, the committee issued a negative recommendation for funding. The reasons for the recommendation, as given in the Final Evaluation Determination document, are that the clinical trial results suggested small benefits with afamelanotide and that cost-effectiveness was not reached (NICE Citation2018a, p1).

The appeal

Stakeholder organisations of appraisal proceedings at NICE have the option to appeal against a negative recommendation, based on the following grounds: either that NICE has failed to act fairly (ground 1a) and/or exceeded its powers in making the assessment that preceded the recommendation (ground 1b), or that the recommendation is unreasonable in the light of the evidence submitted to NICE (ground 2). The appeals submitted by the stakeholder organisationsFootnote1 of the afamelanotide appraisal were upheld on all grounds in collectively six appeal points, of which three were put forward by our patient organisation, the International Porphyria Patient Network (IPPN), which provides cross-border support and counselling of patients suffering from porphyria and porphyria patient associations in scientific, medical and healthcare policy matters. After the appeal procedure, the evaluation was remitted to the same HST committee, with the expectation that the upheld points be addressed. Under ground 2, this concerned:

The appeal panel’s conclusion that it was unreasonable for the committee to state that the trial results show small benefits with afamelanotide (BAD 2.2 and 2.3, IPPN 2.2). (NICE Citation2018b, p20)

In this point, the panel agreed with the view of the clinical experts that the trial results showed that patients with EPP under treatment with afamelanotide have sunlight exposure times comparable to the healthy population.

During the appeal hearing, it also became evident that the committee did not consider EPP as a disability, because of the perceived absence of visible disease manifestations:

In response to a request for clarification from the panel, Dr Jackson elaborated by saying that they had interpreted ‘disability’ as referring to a patently visible disability, and that it would be problematic if every disease before them were regarded as a disability. (NICE Citation2018b, p9)

The Equality Act 2010 defines disability as a ‘physical or mental impairment that has a substantial and long-term negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities’. Accordingly:

The panel took the view that EPP very clearly meets the definition of a disability under the Equality Act 2010. (NICE Citation2018b, p9)

The appeal panel suggested that the committee seek guidance on the Equality Act 2010 regarding this appeal point (NICE Citation2018b, p10), and under ground 1b urged it to address:

The failure to demonstrate adequate consideration of the legal duties and obligations placed on it as a public authority under the Equality Act (CLINUVEL1b.1 and IPPN 1b.1). The appeal panel considers that this is likely to include express consideration of whether the methodology used in the evaluation discriminates against patients with EPP and if so what reasonable adjustments should be made. (NICE Citation2018b, p20)

Further, after the scoping workshop, NICE excluded the IPPN as a stakeholder in the appraisal proceedings, preventing its participation at the committee meetings. The appeal panel considered that the IPPN, as the only stakeholder with first-hand long-term experience with afamelanotide treatment, was important for the evaluation and viewed its exclusion from the second committee meeting as unfair (ground 1a, NICE Citation2018b, p20). The decision of the appeal panel was published in October 2018.

After the appeal

To address the implications of the upheld appeal points, a third committee meeting was held in March 2019, this time including an IPPN representative. However, until now (April 2022) the minutes and documents of this meeting are not publicly available. In May 2020, during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, NICE defined the evaluation of afamelanotide as not being therapeutically critical and paused the proceedings. The restart of the procedures was announced in June 2020, but no further formal activities were resumedFootnote2. Meanwhile, other appraisal procedures continue.

Inconsistencies with other appraisal procedures

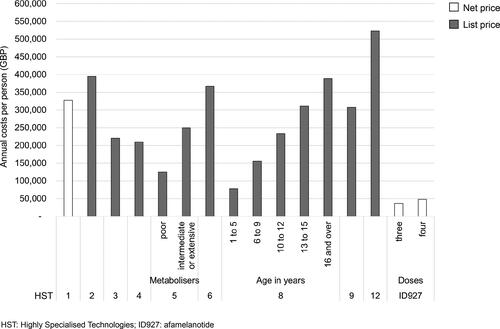

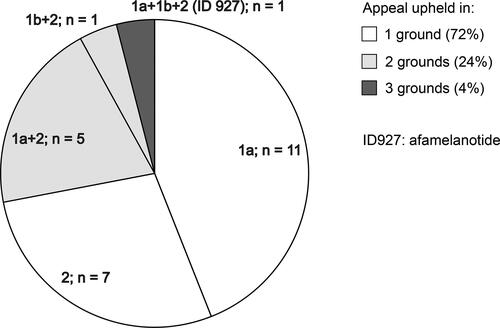

Considering the upheld appeal point 1b, the IPPN was concerned whether and to which extent the methodology used in the evaluation of afamelanotide differed from other assessments. We therefore compared publicly available information of previous appraisal procedures with a positive recommendation for funding by the HST committee with the evaluation of afamelanotide. Some results of this analysis were shared with the HST committee in writing in January 2019 as part of the IPPN’s submission of new evidence and orally at the third committee meeting in March 2019. The identified inconsistencies include the observation that in previous appraisal procedures the voice of the patients and clinical experts apparently was given more weight for decision-making, for example regarding the extent of the experienced benefits and effects on quality of life. Further, we noticed that the annual costs for afamelanotide are considerably lower than the annual costs for all other technologies recommended for funding by the HST committee so far (). When analysing appeals conducted at NICE (HST and Single Technology Assessment programmes), we realised that only in the case of afamelanotide points were upheld in all possible grounds for appeal ().

Ensuring fairness in priority-setting

The appeal process is part of the accountability for reasonableness framework, which was adopted by NICE to ensure fairness in their decision-making and priority-setting. The framework consists of the following conditions: publicity, relevance, appeal and revision, and enforcement. In the case when an upheld appeal is not followed by the subsequent steps – that is, revision and enforcement – the accountability for reasonableness framework cannot be viewed as completed and the fairness of the appraisal proceeding is not established (Schlander Citation2008). The assessment of afamelanotide for treating EPP represents a real-world example for a recent finding by Charlton (Citation2020), who analysed policy changes at NICE over the last 20 years and concluded a trend towards a loss of fairness and allocative efficiency of NICE decisions. McPherson and Beresford (Citation2019) already criticised the tokenistic character of lay person participation and the devaluation of the patient’s voice at the current NICE guideline development procedures for treating depression.

Conclusion

In our opinion, patients and healthcare providers in England need to be able to rely on a truly participatory, objective and fair assessment of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of technologies by NICE, and deviations perceived as inconsistent and unreasonable ultimately may undermine the trust in the Institution. While we do not advocate for funding of a technology ‘at all costs’, we however believe that, based on the appeal outcome and the unmet need of people with EPP as well as to re-establish fairness and equality of treatment, a thorough and timely re-analysis of afamelanotide would be warranted.

Data availability

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Notes

1 Stakeholder organisations of the appeal process: The British Association of Dermatologists (BAD), The International Porphyria Patient Network (IPPN), The British Porphyria Association (BPA) and Clinuvel (UK) Ltd.

2 Update: In February 2022, an informal virtual stakeholder engagement workshop organised by NICE was conducted and the restart of the procedure announced.

References

- Barman-Aksözen, J., M. Nydegger, X. Schneider-Yin, and A.-E. Minder. 2020. “Increased Phototoxic Burn Tolerance Time and Quality of Life in Patients with Erythropoietic Protoporphyria Treated with Afamelanotide – A Three Years Observational Study.” Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 15 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1186/s13023-020-01505-6.

- Charlton, V. 2020. “NICE and Fair? Health Technology Assessment Policy under the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 1999-2018.” Health Care Analysis 28 (3): 193. doi:10.1007/s10728-019-00381-x.

- Equality Act. 2010. “Definition of disability under the Equality Act 2010.” Accessed April 4, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/definition-of-disability-under-equality-act-2010

- Falchetto, R. 2020. “The Patient Perspective: A Matter of Minutes.” The Patient 13 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1007/s40271-019-00399-2.

- Langendonk, J. G., M. Balwani, K. E. Anderson, H. L. Bonkovsky, A. V. Anstey, D. M. Bissel, J. Bloomer, et al. 2015. “Afamelanotide for Erythropoietic Protoporphyria.” The New England Journal of Medicine 373 (1): 48–59. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1411481.

- McPherson, S., and P. Beresford. 2019. “Semantics of Patient Choice: How the UK National Guideline for Depression Silences Patients.” Disability & Society 34 (3): 491–497. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.1589757.

- Naik, H., S. Shenbagam, A. M. Go, and M. Balwani. 2019. “Psychosocial Issues in Erythropoietic Protoporphyria – The Perspective of Parents, Children, and Young Adults: A Qualitative Study.” Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 128 (3): 314–319. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2019.01.023.

- NICE. 2018a. “Afamelanotide for Treating Erythropoietic Protoporphyria.” Final evaluation document. May 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-hst10009/documents/final-evaluation-determination-document

- NICE. 2018b. “Advice on Afamelanotide for Treating Erythropoietic Protoporphyria [ID927].” Decision of the panel. London. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-hst10009/documents/appeal-decision

- Rufener, E. A. 1987. “Erythropoietic Protoporphyria: A Study of Its Psychosocial Aspects.” British Journal of Dermatology 116 (5): 703–708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb05904.x.

- Rutter, K. J., I. Ashraf, L. Cordingley, and L. E. Rhodes. 2020. “Quality of Life and Psychological Impact in the Photodermatoses: A Systematic Review.” The British Journal of Dermatology 182 (5): 1092–1102. doi:10.1111/bjd.18326.

- Schlander, M. 2008. “The Use of Cost-Effectiveness by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE): No(t Yet an) Exemplar of a Deliberative Process.” Journal of Medical Ethics 34 (7): 534–539. doi:10.1136/jme.2007.021683.