Abstract

Recent UK policy changes enable claimants to record their Personal Independence Payment (PIP) assessments, presenting an opportunity to study how they are produced interactionally. Disabled people have often reported feeling disempowered by PIP assessments, and these assessments are notoriously inaccurate – the vast majority are overturned in the claimants’ favour upon appeal. Given the quality of claimants’ lives often depends on their outcome, it is urgent to learn how the assessment process yields so many successful appeals. Here we analyse a small sample of one PIP assessment recording, uploaded to YouTube by the claimant, to show the importance of understanding these high-stakes interactional situations. We intend for this to show the importance of looking at the interactional detail of PIP assessments, which have hitherto been hidden from scrutiny because of the difficulty of obtaining recordings of assessments.

Personal independence payment consultations: activism and the right to own recordings

Personal Independence Payments (PIPs) are a non-means tested and non-taxable benefit for people in the UK who need support with daily activities and/or getting around due to a long-term illness or disability. PIP assessments are typically carried out in-person by a health care professional whose role it is to assess need through focusing on two key components: mobility (the person’s ability to get around) and daily living (the ability to perform a range of functions and activities necessary for everyday life). The entitlement to these benefits is based on an in-person assessment which has been outsourced by the UK Government to two private companies (Independent Assessment Services and Capita).

PIP assessments were intended to deliver reliable, fair, standardised assessments (Gray, Citation2017), however 67% of assessment decisions are overturned in the claimant’s favour on appeal (DWP Citation2021b), suggesting those aims have not been met. Responding to frustrations and experiences of inequity, disabled people started unofficially recording PIP interviews to aid in these appeals and to share information with others (see e.g. Reed Citation2017). Claimants began using social media to share tips about how to navigate PIP assessment questions, and some uploaded recordings to YouTube (providing the data used here). At first, official policies limited recording by requiring expensive ‘tamper-proof’ tape systems. By 2019, however, the ‘On The Record’ campaign (DPAC Sheffield Citation2020; Recovery in the Bin, Citation2019) had started lending out inexpensive, tamper-proof recording kits across the UK, letting claimants officially record their assessments. Human rights lawyers also began to put legal pressure on the government to record all PIP assessments by default (James et al. Citation2019). In late 2020, the two UK PIP assessment providers ATOS and Capita began offering recordings of telephone-based PIP assessments, and when in-person assessments resume (currently paused because of the COVID-19 pandemic), ministers are committed to providing recordings by default. Carina Murray, a campaigner for improving access to recording PIP assessments, responded by saying: ‘recording assessments will fill in the blanks where information gets missed, so our voices will be heard.’ (Independent Lives Citation2020). Here we present an initial analysis of some early PIP assessment recordings to begin this process. We accessed PIP recordings through videos already in the public domain, uploaded to YouTube by PIP claimants. We applied for and received ethical approval from Loughborough University ethics committee to analyse the videos as data. In this article we draw on one recording of a PIP assessment to illustrate our central argument. For anonymity, all names and identifying information have been changed.

We must study PIP assessments as interactions

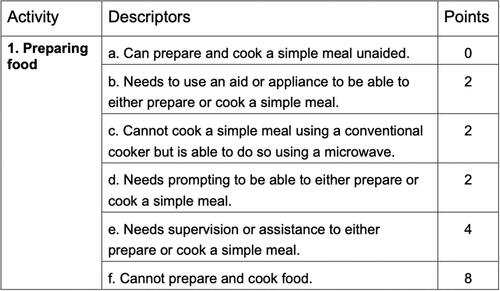

Given the implications of the outcome, it is unsurprising that disabled people often attribute stress and negative mental health impacts to the process of PIP assessments (Gray Citation2014; Machin and McCormack Citation2021). The introduction of Personal Independence Payments (PIP) in 2013 fundamentally changed disability assessments and redrew the boundaries of what (and who) is considered disabled. This is a striking example of how the social construction of disability is manifested so explicitly in policing what, officially, ‘counts’ as disability (Roulstone Citation2015). In practice, PIP claimants fill in a questionnaire about activities of daily living entitled ‘how your disability affects you’ (DWP, 2021a), which healthcare professionals (HCPs) use during a semi-structured PIP assessment interview to evaluate their eligibility for PIP on a nine-point scale. For example, the first item in the PIP assessment ‘table of activities, descriptors and points’ (Citizen’s Advice Citation2021) evaluates the claimant’s ability to prepare food for themselves (see which is the Food Preparation section of the PIP assessment scoring sheet. Points are awarded based on assessed level support needs relating to specific activities – in this case ‘preparing food’). Note how one HCP designs an initial question about food preparation:

Figure 1. The food preparation scoring sheet in the PIP assessor’s ‘table of activities, descriptors and points.’

‘So preparing food. You’ve put that sometimes you can forget and that your wife supervises and your wife cooks most of the time, but you can use the microwave safely.’

After several turns where the claimant explains that they cannot cook safely, the HCP apparently ignores this response and refers, instead, to their official notes saying:

‘So, um, you’ve put here that you can microwave safely.’

After the HCP does repeated requests for confirmation (‘Is that right?’)—strongly weighted towards a positive response - the claimant finally confirms that:

‘Yeah. Yeah, I can, I can use the microwave safely.’

The claimant (who uploaded the video) reported receiving zero points overall, including for this food preparation activity, despite emphasizing that they cannot cook for themselves. Since claimants’ needs can be minimized through the HCP’s design of interview questions in this way, it is essential that we study PIP assessments at interactional levels of detail. Until now, however, such data have remained largely unavailable for scrutiny.

The interactional production of PIP assessments

The Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) itself recognizes that variations in the interactional production of PIP assessments are undermining their validity. In an ‘accountability hearing’, the DWP Permanent Secretary Peter Schofield gave the following evidence on the different outcomes of phone and face to face consultations: ‘because the assessor is not seeing the individual face-to-face, they have to ask better questions and they have to get to the heart of the issue that is affecting the individual in terms of their daily living. They can’t just make judgments on what they see face to face in a snapshot of the meeting that they have. That seems to translate into better quality reports from assessors’ (Work and Pensions Committee Citation2021, p. 19). The interactional details of how these questions are formulated, delivered, and responded to, clearly requires detailed analysis. Even with our small sample we can demonstrate how conflicting agendas and disparate understandings of the interview are built into its very first moments.

In the following PIP interview (uploaded to YouTube by the claimant), which we transcribed using Jefferson’s (Citation2004) conversation analytic conventions, the HCP first checks that the recording equipment is on, then announces the start of the PIP assessment.

In line 6, after the assessor has introduced herself by name, the claimant immediately responds with ‘Hi’, and a proffer of his own name ‘I’m Jonathan’, in overlap, while the assessor continues her self-introduction with a list of her professional roles (lines 7 and 9). Rather than having listened to Jonathan introducing himself, the assessor then seems—from the use of the surname ‘Fountain’ in line 11—to (incorrectly) read his name from her notes.

Sacks (Citation1995, pp. 3–4) first lecture on the ‘Rules of Conversational Sequence’ describes one of the earliest observations in conversation analysis (CA) (Schegloff Citation1995, pp. xvi–xvii): that once someone volunteers their name in introduction, it is normative to give yours in return. While the claimant orients to this norm by producing his name in line 8, the HCP delivers her opening monologue without pause and, as her mistaking his name for ‘Joshua’ shows, without attending to his response. Indeed, by apparently reading his name from her notes (incorrectly), and only requesting that he provide confirmation, the HCP demonstrably prioritizes her ‘official’ source of information over the claimant’s own self-identification. Even from this tiny extract, we see the claimant treating the situation an interpersonal conversation by offering his own name in response to the HCP’s self-introduction, while the HCP treats it as an interview, prioritizing her institutional roles and official sources of information.

Although we lack space to provide a fuller analysis, we can offer a few initial observations. In the PIP assessment that follows, the assessor frequently designs loaded questions (as in the question(s) about food preparation, outlined above), that can have a significant effect on how people answer assessment questions (Jones et al. Citation2020). Jonathan often responds in ways that do not conform to the questioner’s presuppositions, and the HCP frequently re-designs her questions until she gets responses that minimise his support needs. These first few seconds alone indicate how the claimant and the HCP construct their identities within the PIP assessment, how opportunities to talk are organised in this setting, and how different agendas are upheld or undermined throughout the assessment. This short sequence sheds light on moments that may contribute to the dissatisfaction that Jonathan expresses in the video description and comments underneath, as well as why other claimants experience PIP assessments as unempathetic and impersonal (Porter, Pearson, and Watson Citation2021). It also suggests that interactional studies of PIP interviews could explain how they often understate claimants’ needs, and that applied CA combined with methods that prioritize disabled people’s perspectives and involvement (e.g. Williams et al. Citation2020) could help to improve the trustworthiness and efficacy of PIP assessments.

Concluding thoughts

In this paper we prepare for imminent policy changes to PIP assessment recordings by arguing that a detailed CA study of the interactional production of initial PIP assessments would help explain their inaccuracy, and could provide guidelines for improving practice. The ability to access and record PIP interviews represents a vital new opportunity to use these recordings for research that could have a significant impact on the outcome of assessments, and therefore on the lives of disabled people. The voices of disabled people matter, and so do the ways in which they are involved in interactions that shape their economic and social lives.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Kathryn Bole from the Suffolk Coalition of Disabled People for her feedback. We authors would also like to thank the vibrant PIP YouTube community who share information about, and experiences of, their PIP assessments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Citizen’s Advice. 2021. “Personal independence payment (PIP) – table of activities, descriptors and points”. Accessed 28th October 2021. https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/Migrated_Documents/adviceguide/pip-9-table-of-activities-descriptors-and-points.pdf

- DPAC Sheffield. 2020. “PIP assessment recording equipment”, Disability Sheffield. Accessed 28th October 2021. https://www.disabilitysheffield.org.uk/blog/pip-assessment-recording-equipment-2020-01-12

- DWP. 2021a. “How Your Disability Affects You” Accessed 1st November 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/713118/pip2-how-your-disability-affects-you-form.pdf

- DWP. 2021b. “Personal independence payment statistics to April 2021”. Accessed 1st November 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/personal-independence-payment-statistics-to-april-2021/personal-independence-payment-statistics-to-april-2021

- Gray, P. 2014. “An independent review of the Personal Independence Payment Assessment”. Stationery Office, Department of Work and Pensions.

- Gray, P. 2017 The second independent review of the Personal Independence Payment assessment, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/

- Independent Lives. 2020. “Audio recording option set to be introduced for all PIP assessments”. Accessed on 1st November 2021. https://www.independentlives.org/news/audio-recording-for-pip

- James, A. M. Carden, K. Kenningley, S. Hallett, D. Kalonzo, and T. J. Nurminen. 2019. “For the Record: Evaluating the need to provide recording equipment in PIP assessments and Tribunal Hearings to Facilitate Accessibility in the UK”. International Disability Law Clinic – School of Law, Leeds University. Accessed 1st November 2021. http://www.lukeclements.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/For-The-Record-2019.pdf

- Jefferson, G. 2004. “Glossary of Transcript Symbols with an Introduction.” In Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation, edited by G. H. Lerner, 13–31. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Jones, D., R. Wilkinson, C. Jackson, and P. Drew. 2020. “Variation and Interactional Non-Standardization in Neuropsychological Tests: The Case of the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination.” Qualitative Health Research 30 (3): 458–470. doi:10.1177/1049732319873052.

- Machin, R, and F. McCormack. 2021. “The Impact of the Transition to Personal Independence Payment on Claimants with Mental Health Problems.” Disability & Society 0 (0): 1–24. doi:10.1080/09687599.2021.1972409.

- Porter, T., C. Pearson, and N. Watson. 2021. “Evidence, Objectivity and Welfare Reform: A Qualitative Study of Disability Benefit Assessments.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 17 (2): 279–296. doi:10.1332/174426421X16146990181049.

- Reed, J. 2017. “Why I secretly taped my disability assessment”. BBC News. October 16 https://www.bbc.com/news/health-41581060

- Recovery in the Bin 2019. “Put PIP and WCA Assessments On The Record”. November 1. https://recoveryinthebin.org/put-pip-and-wca-assessments-on-the-record/

- Roulstone, A. 2015. “Personal Independence Payments, Welfare Reform and the Shrinking Disability Category.” Disability & Society 30 (5): 673–688. doi:10.1080/09687599.2015.1021759.

- Sacks, H. 1995. Vol. I of Lectures on Conversation, edited by G. Jefferson. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Schegloff, E. A. 1995. “Introduction.” In Vol. I of Harvey Sacks: Lectures on Conversation, edited by G. Jefferson, ix–lxii. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Williams, V., J. Webb, S. Read, R. James, and H. Davis. 2020. “Future Lived Experience: Inclusive Research with People Living with Dementia.” Qualitative Research 20 (5): 721–740. doi:10.1177/1468794119893608.

- Work and Pensions Committee. 2021. “Oral evidence: The work of the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions”, HC 514 (Oral Evidence No. 514). House of Commons. Accessed 1st November 2021. https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/2514/pdf/