Abstract

Few qualitative studies have explored the lives of autistic women diagnosed in adulthood, despite this knowledge being essential to inform awareness of the intersection of autism and gender. This systematic review was undertaken to synthesise available qualitative evidence on the lived experience of autistic women diagnosed in adulthood. The accounts of 50 women from nine qualitative studies were synthesised using thematic analysis and four super-ordinate themes were identified: wanting to ‘fit in’; making sense of past experiences; developing a new ‘autistic identity’; and barriers to support. The autistic women spent many years without a diagnosis or autism-specific support, felt misunderstood, and experienced social exclusion. Following their diagnosis, they reframed these experiences into new ‘sense-making narratives’, used social media to contact other autistic people, and developed neurodiverse-affirming autistic identities. The studies suggested that health and social care professionals were not always able to recognise, refer, diagnose, and support autistic women effectively.

In childhood, the autistic women who participated in the nine reviewed studies remembered feeling that they were ‘weird’ or ‘alien’ and being bullied due to their difficulties with socialising

These participants imitated their more ‘easy-going’ friends in social situations to keep up appearances and look as if they were in control

After their diagnosis, the autistic women felt more able to be themselves, rather than trying to be the ‘ideal’ person that others expected them to be

The women who participated in the studies believed that, if they had been diagnosed in childhood, they would have coped better with dangerous situations they had encountered during their lives

Most of the women in the studies felt proud of their autistic identity and the success they had achieved, despite the number of challenges they had faced

Points of interest

Introduction

The researchers carried out this systematic review to explore what the findings from primary qualitative studies may reveal about the lived experience of autistic women diagnosed in adulthood, drawing on neurodiversity and intersectionality as their theoretical framework. This framework supported a critical interpretation of the experiences of the autistic women from the reviewed studies, that stemmed from an intersection of their gender and autistic identities.

Currently, there is no reliable and definitive diagnostic biomarker for autism, and so diagnosis is based on a set of behaviours which must include difficulties with social interaction and restricted, repetitive behaviours and interests which cause significant issues for an individual (WHO Citation2018). Without a biomarker, diagnosis is more subjective and open to interpretation by clinicians. Although people with these set of behaviours have been around since the dawn of humanity, new disciplines emerged during the last century, such as child psychiatry, that classified and managed the behaviour of the population according to normative measures (Foucault Citation1975). The construction of ‘autism’ placed a boundary within a continuum of behaviours and separated out the traits considered ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ (Molloy and Vasil Citation2002; Nadesan Citation2013).

When the additional autism category of Asperger syndrome (AS) was classified in 1992, the number of people diagnosed in Europe and North America increased due to the medicalisation of ‘atypical’ behaviours in people without a learning disability (Conrad Citation2007; Wheeler Citation2011; WHO Citation1992). This rising prevalence contributed to an increase in autism awareness, the availability of assessment centres and autism services, and diagnostic switching from other developmental and psychiatric conditions to autism (Russell Citation2021). Media interest in neurodiversity, autobiographies of autistic people, and fictional accounts increased the likelihood that a person may consider an autism diagnosis as an explanation of their differences (Hacking Citation2009; Russell Citation2021; Russell et al. Citation2015). This subsequently meant that even more people got diagnosed, creating a ‘looping effect’ (Hacking Citation1995). Furthermore, autism was historically regarded as a very rare condition of childhood, mainly occurring in boys, whilst now it is considered to be a lifelong neurodevelopmental divergence occurring in all genders (Brugha et al. Citation2011).

Autism, without a learning disability (LD) or language delay, previously known as AS, was categorised in 1992 (WHO 1992). Consequently, autistic women without an additional learning disability or language delay, who had been at school before the early-1990s, were unlikely to have been diagnosed during their school years. Although autism is now known to be a lifelong condition, with similar prevalence rates in all age groups, it was historically understood to be a condition of childhood (Brugha et al. Citation2011). As autism was thought to affect predominantly young boys, many autistic women remained undiagnosed for decades without any autism-specific support (Brugha et al. Citation2016). It may be that women, who decide to seek a diagnosis later in life, are able to understand themselves better and make more sense of their experiences. Exploring the lived experiences of autistic women who were diagnosed in adulthood is essential for conceptualising potential avenues of support, yet their ‘voices’ have been largely missed, as few qualitative studies have been undertaken in this group (Milton Citation2014). A roundtable report identified gaps in autism research and specifically highlighted the lack of knowledge about autistic women and the small numbers of women included in research studies (Howlin et al. Citation2015). Feminist disability studies emphasise the importance of all women’s voices being brought to the forefront, especially in research where their experiences have traditionally been dismissed and misrepresented (Garland-Thomson Citation2005; Piepmeier, Cantrell, and Maggio Citation2014; Wendell Citation1989).

While writing this review, the researchers chose to use identity-first language rather than person-first language, for example the term ‘autistic person’ instead of ‘person with autism’, as this is the terminology that most of the autistic community in the UK prefers (Kenny et al. Citation2016; Sinclair Citation2013). Person-first language has been generally rejected by this community as autistic people do not wish to be disassociated from their condition, as if it is somehow shameful. The terminology used is important, as it shapes people’s assumptions and beliefs. Many self-advocates have re-appropriated identity-first language, once used to evidence ‘pathology’, in a positive way (Bottema-Beutel et al. Citation2021; Gernsbacher Citation2017). The term ‘autism’ has also been used as a shorthand version for ‘autism spectrum condition’ without learning disability or language delay, which was the set of behaviours previously categorised as Asperger syndrome (WHO 1992).

This systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO Registration number: CRD42017084079).

The positionality of the first author

The first author’s interest in autism and neurodiversity started eight years ago, when her son was diagnosed with autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). She enrolled on a Post-graduate Certificate in Autism and Asperger syndrome at Sheffield Hallam University and it was during a lecture that it suddenly struck her that her son’s apparently ‘atypical’ behaviour was very similar to her own. She was eventually diagnosed with autism and ADHD at the age of 50 years old. The diagnosis explained many of the difficulties, as well as strengths, she had experienced throughout her life, but particularly in her teenage years when she dropped out, had mental health and substance abuse issues, and attempted suicide. However, she managed to gain her academic qualifications as a mature student on a part-time, distance-learning basis whilst working full-time. In 2017, she started a part-time Professional Doctorate in Health Research at the University of Hertfordshire, and this review was undertaken during this programme. She still works full-time at the UK Health Security Agency (formally known as Public Health England) as a senior scientist coordinating a quantitative survey of people living with HIV in the UK called Positive Voices. Since February 2020, she has also been assisting in the production of the daily COVID-19 surveillance figures as part of the public health response to the pandemic.

Positionality, along with reflexivity, are critical examinations conducted by feminist researchers which are used to reveal their position in the complex hierarchies of power within society. Having conducted this review as part of her doctoral studies with insider experience of the phenomena explored, her interpretations of the data and writing have been limited by, and situated by, the knowledge she has learnt and her experiences of the world (Haraway Citation1988; Willig Citation2013). However, this knowledge has helped her relate to and understand the experiences and emotions that the participants in the articles described (Chown et al. Citation2017; Fletcher-Watson et al. Citation2019; Milton Citation2014; Woods et al. Citation2018). Feminist research encourages this type of insider research and criticises the way positivist approaches emphasise objectivity and neutrality (Franks Citation2002; Frost and Holt Citation2014). She believes, as many feminist scholars do, that maintaining a completely objective stance to a research matter is not possible, or even appropriate (Willig Citation2013). As qualitative research necessitates a researcher’s involvement and so, to yield any worthwhile insight into participants’ lived experiences, it cannot be done in a neutral or disengaged manner (Madill, Jordan, and Shirley Citation2000). She has attempted to use her own experience of acquiring an autism diagnosis in adulthood to enrich her interpretations, rather than thinking of it as a bias needing to be eliminated or ‘bracketed out’ (Bertilsdotter Rosqvist et al. Citation2019; Frost Citation2016).

As subjectivity is an inevitable part of research, the first author maintained an ongoing process of reflexivity throughout this systematic review. Reflexivity is a critical examination of how one sees the social world and understands the relations between content, context and consequences of knowledge that arise from the research process (May and Perry Citation2017). ‘Reflexivity is not just about the ability to think about our actions—that is called reflection—but an examination of the foundations of frameworks of thought themselves’ (3). She considered her motivation and reasons for conducting this review and how these may have affected her interpretation of the findings. She kept a reflexive journal from the beginning of her doctoral programme in which she recorded her thoughts and questions about the research, decisions made, challenges addressed and critical themes that she identified (Finley Citation2002). Whilst writing, she became more aware of her own assumptions and beliefs, as well as the context that surrounded the studies, and how they related to her research interpretations (Frost Citation2016). She confesses to having developed a positive autistic identity following her own autism diagnosis and is pleased that there are other autistic women who have experienced similar diagnostic journeys to her own. However, she made sure that the interests and views of the study participants were expressed, thus mitigating the risk of bias associated with the subjectivity in the review (Bertilsdotter Rosqvist et al. Citation2019).

Theoretical framework: neurodiversity and intersectionality

The researchers’ understanding of autism was shaped by the theories of neurodiversity and intersectionality. These perspectives underpinned and informed the process and interpretation of the data in this review.

Neurodiversity

‘Neurodiversity’ was first described in the literature by Singer (Citation1999) who proposed the concept for intersectional analysis. It was based on biodiversity that describes how ecosystems benefit from having a wide variety of life, for example by making them more resilient and sustainable. The behaviours of neurodivergent individuals, including autistic people and those with other neurodevelopmental conditions such as ADHD and dyslexia, may be more extreme when one considers the distribution of sensory, affectual and cognitive processing within the general population (Murray Citation2020). Although the minority of the population may diverge strongly from the ‘norm’, they should still be recognised and respected as a natural expression of human diversity that fills an ‘ecological niche’ in society (Blume Citation1997; Singer Citation1999). Autistic people can bring many complementary and beneficial skills to a community, particularly if it values and promotes diversity by moving beyond essentialist binaries of ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Chapman Citation2020; Runswick-Cole Citation2014).

The neurodiversity paradigm, in line with the social model of disability, challenges the medical model which links autism to a specific stigmatising ‘deficit’, laden with negative beliefs about restricted abilities and limited potential (Gillman, Heyman, and Swain Citation2000; Goffman Citation1963; Ho Citation2004). These negative attitudes are a form of psycho-emotional disablement that can significantly impact on the emotional well-being and self-esteem of autistic people (Milton and Moon Citation2012; Reeve Citation2004; Watermeyer and Swartz Citation2008). Humanity is neurologically diverse but propositions about normality still assume an ideal, male, white, neurotypical person - defined as a ‘normate’ by psychologists within the eugenics movement (Garland-Thomson Citation2017). Autistic people are stigmatised because they exhibit behaviours that currently deviate from the ‘norm’, so are treated as ‘other’ and in need of ‘treatment’ (Scuro Citation2017; Wolbring Citation2008). However, to say that there exists a ‘normal’ human with a ‘normal’ brain is no more valid than there being a ‘normal’ ethnic group, gender, or class (Crow Citation2017; Walker Citation2014).

Proponents of the neurodiversity movement, particularly autistic activists, have reclaimed autism for their own and promote diagnosis in a less pathologised form (Kapp Citation2020; Thibault Citation2014). Autistic activism emerged in resistance to the medical model discourse depicting autism as a deficit and argued for autism as an identity that should not be cured or regarded as a tragedy. However, autistic people may require support in order to lead a fulfilling life in a world in which they experience specific and nuanced forms of social oppression (Baker Citation2006; Castells Citation2009; Shakespeare Citation2010). The neurodiversity movement challenges autism research funding that primarily focuses on aetiology, screening, treatment, prevention, and cure. They have shifted attention to research aimed at critically understanding and improving autistic experiences, quality of life and decreasing health care inequalities (Kapp et al. Citation2013; Raymaker and Nicolaidis Citation2013; Robertson Citation2009).

Autism advocates also reject functioning labels associated with autism, as they feel that those given the ‘low-functioning’ label may be devalued and those given the ‘high-functioning’ label may not be considered for the support they need (Milton and Moon Citation2012). Clinicians usually distinguish levels of functioning using standard intelligence tests, however these tests have been shown to underestimate autistic intelligence, so their usage may lower expectations and deny autistic people access to appropriate educational support (Dawson et al. Citation2007). Furthermore, distinguishing between levels of functioning is misleading as the functioning of a person fluctuates depending on the context, for example their perception of control over and inclusion within their environment, their emotional state, other people’s expectations, and what support has been provided (Beardon Citation2017; den Houting Citation2019; Murray Citation2009).

This process of resistance and redefinition has started to reshape the autism landscape into a more progressive and less stigmatising one (Gobbo and Shmulsky Citation2016). Ultimately, the goal is to reduce discrimination and stigmatisation and create a more compassionate and inclusive world that does not pathologise and dehumanise diverse people (Chapman Citation2020). The neurodiversity theory has enabled many autistic individuals to regard autism as a cognitive style; not a ‘disorder’ which must be removed or cured like a disease (Bumiller Citation2008, 4; Cameron Citation2014b; Swain and French Citation2000).

Intersectionality

Within an increasingly complex world, intersectionality theory has developed into a valuable interdisciplinary concept for understanding the shared and the unique complexity of multiple social and cultural identities. Originally conceived as a tool for analysing black women’s oppression in America, intersectionality is now widely used in social sciences (Crenshaw Citation1989; King Citation1988). In intersectionality theory, when a person is a member of more than one marginalised group, they intersect to create a group with a qualitatively unique experience of oppression that is different to the combination of the original groups. Such a group has its own specific needs and problems, as well as ways of meeting those needs and making their mark, which may differ or conflict with those of the original groups and therefore, their ‘distinct voice’ needs to be recognised (Begum Citation1992; Garland-Thomson Citation2005). Biological and cultural categories such as ethnic group, class, gender identity, sexual orientation, marital status, nationality, disability, age, and religion are considered ‘multiple and interlocking’ (Bowleg Citation2012, 1267), allowing people to recognise ‘the outcomes of these interactions in terms of power’ (Davis Citation2008, 68).

Historically, disability was often unrecognised in contemporary feminist research; however, this intersection is vital for feminist and general philosophy (Hall Citation2015). Fine and Asch (Citation1988) suggested that feminists excluded women that were disabled from studies in the past because of fear that they may bolster stereotypical notions of females as dependent. Deep-seated beliefs of female emancipation, independence, and self-sufficiency were the foundation of feminism, but conflicted with the stereotypical view of disabled women (Mohamed and Shefer Citation2015; Simpson and University of Oxford Citation2019). In addition, the disabled people’s movement historically favoured the representation of disabled males within society (Bê Citation2014). The barriers associated with female gendered role responsibilities, such as assistance with childcare or looking after elderly relatives in order to enable paid employment, were mostly ignored (Morris Citation1996; Thomas Citation1999). When individuals with multiple identities are not even recognised within their identity groups, this is known as ‘intersectional invisibility’ (Purdie-Vaughns and Eibach Citation2008). Intersectionality theory seeks to make the less visible or under-recognised, visible and explore the inequalities that result in some individuals being marginalised (Smooth Citation2013). The union of the theoretical fields of gender and disability has deepened our understanding of gender roles, interdependence, experience of care, lived experience and social justice (Garland-Thomson Citation2002; Wendell Citation1989).

Saxe (Citation2017) asserts that an intersectional framework should be used to study the lived experiences of autistic women, who are often disregarded due to the male-biased understanding of the condition that dominates autism discourse. Feminist scholars have described how ‘stereotypical autistic traits, and their discursive representations have been culturally coded as masculine rather than feminine’ (Davidson Citation2008b, 660). As men often play the role of autistic characters in literature and in the media, the public seem to find it more difficult to envisage an autistic woman (Murray Citation2012). Unfortunately, when characteristics of a condition are stereotypical of one gender, there is a risk that clinicians will be biased diagnostically (Hughes Citation2015).

Neurodiversity and intersectionality provided a valuable framework to explore the experiences, social oppression and psycho-emotional disablement faced by autistic women through the male-biased and ableist discourse around autism (Strand Citation2017; Thomas Citation2007).

Methods

Search strategy

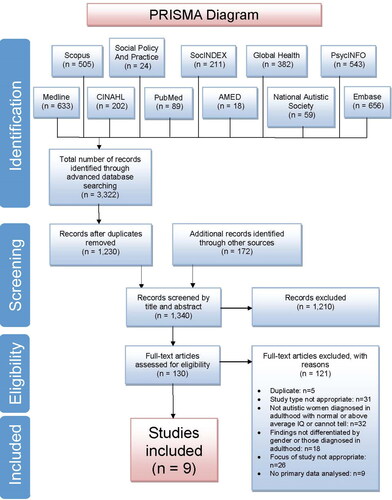

Throughout the process of identifying the included studies, the researchers followed the guidelines stated in the PRISMA Statement of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (Moher et al. Citation2015). Eleven electronic databases were searched for peer-reviewed primary research: Global Health, Scopus, Embase, OVID Medline, PsycINFO, SocINDEX, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the National Autistic Society database, Social Policy and Practice, Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED) and PubMed (). We used the search term: (autis* OR asperger* OR AS*) AND (wom* OR female* OR gender). The publications were limited to English language articles dated between 1st January 1943 and 21st August 2020. References were managed in EndNote X9.3.3 software and 3,322 publications were identified from the searches. This broad approach was chosen to allow for the identification of papers that might not otherwise have been found (Boland, Cherry, and Dickson Citation2017). Staying abreast of newly published articles throughout the course of this review provided a further 172 articles. Duplicates were removed, leaving 1,340 articles available for screening.

The titles and abstracts of 1,340 articles were screened by consulting the inclusion and exclusion criteria (). The third author (A-TJ) independently screened a random selection of 15% of the articles in order to check for consistency. If any disparities were found and were not resolved, arbitration would have been sought from the first author’s two doctoral supervisors: SS and SR. During the title and abstract screening process, 1,210 articles were excluded, leaving 130 articles to be assessed for eligibility by reading the full text of each publication. After SS and SR verified their eligibility, nine articles were classified as ‘accepted’.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 3. .

Table 2. Characteristics of the primary research articles included (n=9).

Study characteristics

Whilst the subject matter of the nine included articles were broadly about the lived experiences of autistic adults, their original research topics varied: Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy (Citation2016) investigated the female autism phenotype, Griffith et al. (Citation2012) support needs, Hurlbutt and Chalmers (Citation2004) challenges of employment, Kanfiszer, Davies, and Collins (Citation2017) gender and social relationships, Krieger et al. (Citation2012) perceptions of the workplace, Leedham et al. (Citation2020) diagnosis in middle to late adulthood, Smith and Sharp (Citation2013) unusual sensory experiences, Stagg and Belcher (Citation2019) diagnosis in later life and Webster and Garvis (Citation2017) success and critical life moments (). The countries of origin were mainly from the United Kingdom, with the rest from the United States, Switzerland and Australia. In two of the articles, the ages and age at diagnosis of participants were provided as a range, however the articles confirmed that they had been diagnosed after the age of 18 years of age (Stagg and Belcher Citation2019; Webster and Garvis Citation2017).

Three studies used narrative analysis as their methodology, two used interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), and the others used framework analysis, thematic analysis, content analysis and grounded theory. While some researchers argue that primary qualitative studies should have similar methodologies to be included within a meta-synthesis, others maintain that combining evidence from different analytical approaches is acceptable (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2005). Out of these different methodologies, IPA seems to be the approach that is most suitable for primary autism research as it is committed to viewing people as experts on their own personal world, establishing an ‘equality of voice’ and promoting the process of reflexivity (Dowley Citation2016; Howard, Katsos, and Gibson Citation2019; MacLeod Citation2019). It focuses on the specific, unique perspectives of each participant, the meanings behind their interpretations, and how they relate to their historical, cultural and societal context (Creswell and Poth Citation2016).

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was chosen as the methodology for analysing the findings from the nine primary research articles in this systematic review. Thematic analysis is a well-tested technique that encourages reviewers to have an evidential link between their findings and the results of primary studies, using quotes as examples to describe the themes developed, therefore preserving principles that are fundamental to systematic reviewing (Thomas and Harden Citation2008). The articles were read and reread until the first author (CK) was very familiar with the studies and notes were made about possible themes and concepts that related to the review question, as recommended by Braun and Clarke (Citation2013). To thematically analyse the qualitative findings, digitised pdf copies of the articles were downloaded into the qualitative data analysis software, NVivo Mac Release 1.3, for coding and categorisation.

Only quotes and analysed results and interpretations that were specifically associated with 50 of the participants, who were women who had been diagnosed in adulthood, were analysed (). Data associated with other participants from the studies, such as men and women diagnosed in childhood, were not extracted. When a strand of data related to multiple concepts, it was coded multiple times. When similarities and associations across the studies were identified, the coded data were grouped into clusters of related concepts. These clusters were identified inductively, and constantly compared and regrouped into sub-themes. Some of the concepts were refined by moving to and from each of the studies to determine how they might relate together. Super-ordinate themes were then developed, enabling the creation of a higher-order interpretation of the translations. The creation of the super-ordinate and sub-ordinate themes were considered by SS and SR and were subsequently approved.

Throughout the data analysis process, the codes, categories, and themes were evaluated for accuracy and clarity. Whenever the researchers felt uncertain about their decisions or findings, they were double-checked to make sure interpretations were firmly grounded in the data.

Thematic analysis

Four super-ordinate themes were identified in the analysis, which are described below.

Wanting to ‘fit in’

When the women in the studies described their childhood experiences, they remembered thinking that they were ‘weird’, ‘alien’ or ‘a different type of human’ due to the difficulties they had interacting with their friends (Kanfiszer, Davies, and Collins Citation2017; Leedham et al. Citation2020; Stagg and Belcher Citation2019). At school they were bullied and persecuted for being ‘odd’ and felt lonely and distanced from their peers (Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy Citation2016; Huws and Jones Citation2010). Culture determines how one interprets and responds to other people’s verbal and non-verbal communication and, in Western European and North American nations (WENA), one can be judged harshly for not giving enough eye contact, not smiling, raising your voice, being too direct and so on. Goffman (Citation1963) argued that individuals are continuously trying to manage the impressions they make during social interactions. Those with the ability to perform well are considered ‘normal’, while those who exhibit unusual behaviour are considered ‘abnormal’ and stigmatised as a result (Milton Citation2013). A woman in Kanfiszer, Davies, and Collins (Citation2017) felt that she had been perceived as deviating from the expectations placed upon her:

‘… they just ostracised me … what they called ‘sent to Coventry’ where no one in the dormitory would speak to me (laughs) because I so alienated them …It’s my reactions, and the way I interacted with people wasn’t appropriate …’ (664).

The women who participated in the studies were unaware that they were autistic during their childhood and adolescence, so they felt compelled to keep up appearances and look as if they were in control. They observed their more ‘easy-going’ friends and imitated them in social situations, learning their mannerisms and speech, mimicking small talk, and repressed behaviours that others might think were ‘weird’. (Krieger et al. Citation2012; Willey Citation2015). They described how they had changed their ‘persona’ or wore a ‘mask’ as a survival strategy to cover up their difficulties interacting: ‘[when I] appear sort of normal, that is because of the years of actual effort that I’ve put into it’ (Leedham et al. Citation2020, 141). ‘Masking’, also known as ‘camouflaging’ or ‘passing’, is a strategy where a person disguises their underlying authentic self and ‘passes’ as socially competent by using learnt behaviours to act in a ‘socially acceptable’ manner (Ginsburg and Pease Citation1996; Kalei Kanuha Citation1999). However, autistic women often find this lack of authenticity particularly disturbing and damaging to their self-esteem (Foucault Citation1975; Murray Citation2020). Masking may also involve suppressing their repetitive movements, known as stims (short for self-stimulation), such as hand flapping or twiddling hair, despite the fact that they can be used as coping mechanisms during stressful situations (Kapp et al. Citation2019; Lingsom Citation2008).

Butler (Citation2006) argued that being gendered as a woman is, in itself, a kind of improvised performance. In this patriarchal culture, women are often expected to be socially accommodating by being hospitable, communicative, nurturing and biddable, which may motivate some autistic women to emulate this behaviour (Gould and Ashton-Smith Citation2011). However, a few women in the review found it hard to envisage themselves in traditional gendered roles that others expected them to fulfil, such as a mother or carer (Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy Citation2016; Kanfiszer, Davies, and Collins Citation2017). They disregarded these expectations, along with the social construct of gender in general, and adopted more ‘personal’ gender identities (Butler Citation2006; Davidson and Tamas Citation2016). In Kanfiszer, Davies, and Collins (Citation2017), a few women described themselves as ‘tomboys’ and preferred playing with boys when they were younger:

‘Girls are sort of bothered about what they’re wearing and what their hair looks like and their nails and who’s cute in what band … it’s not actually possible for me to be less interested … whereas the guys would be mucking about … something I felt more inclined to be involved with.’ (665)

Making sense of past experiences

Most women felt their diagnosis had been a positive experience as they finally understood their uniqueness and were able to make sense of their lives (Haney and Cullen Citation2017; Leedham et al. Citation2020; Tan Citation2018). Following their diagnosis, autistic women initially felt a range of emotions, such as anger, disbelief, shock, and joy: ‘A relief, because for years and years everything has been put down to anxiety and depression. Everything from the last 30 years made sense, it just all fitted in and it made sense’(Stagg and Belcher Citation2019, 353). Many felt proud of who they had become and the success they had achieved, despite all the challenges they had faced (Krieger et al. Citation2012; Webster and Garvis Citation2017). The diagnosis conceptualised their lifelong challenges as real, not just a quirk of their personality that should be cured; removing some guilt and blame from themselves (Punshon, Skirrow, and Murphy Citation2009; Stagg and Belcher Citation2019).

One woman described crying and feeling overwhelmed when she was finally diagnosed, as it explained why she had struggled so much when she was younger (Webster and Garvis Citation2017) The women seemed to have revised their understanding of their challenges and negative experiences; reattributing struggles and misunderstandings to autism within their ‘sense-making narrative’ (Leedham et al. Citation2020). A sense-making narrative may be revised when a person, who previously had an inadequate way of understanding themselves, gains new insight into their past and feels they understand themselves better (Bury Citation1982; Kim Citation2013). Before having acquired this knowledge, the women were forced to concoct incomplete explanations for their developmental history and life experiences (Limburg Citation2016). Other people had attributed their autistic traits to issues of motivation, poor character, or a flawed upbringing (Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy Citation2016). Following their diagnosis, the women went through a period of intense research and growing self-awareness (Leedham et al. Citation2020). Some began to read autobiographies written by autistic women, giving them a greater understanding of themselves (Hacking Citation2006; Linton Citation2014; Webster and Garvis Citation2017). They described their diagnostic journeys in autistic women’s groups on social media platforms, which allowed them to compare their experiences with those of others (Davidson Citation2008a).

Many of the women felt that a diagnosis in childhood would have increased the quality of their lives, helped them to progress in life, and giving them the knowledge to better understand themselves (Webster and Garvis Citation2017). They believed that, if they had been diagnosed earlier, they would have been better able to sense danger, ‘read’ other people’s intentions, and cope with dangerous situations: ‘I think women tend to be diagnosed later in life when they actually push for it themselves… if people had helped me from earlier on, then life would have been a whole lot easier.’ (Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy Citation2016, 3286). Reflecting on their past, during and after their diagnosis, was upsetting for some who had experienced abuse, bullying, rape, and harassment (Kanfiszer, Davies, and Collins Citation2017; Leedham et al. Citation2020; Webster and Garvis Citation2017).

Compensatory strategies such as masking, although used to avoid rejection from their peers, may have resulted in their social interaction difficulties going unnoticed and their support needs being underestimated (Beck et al. Citation2020). Some women felt they had been misdiagnosed with other mental health conditions when they were younger (Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy Citation2016). However, these previous diagnoses may have accurately reflected clinicians’ understandings of their difficulties at that time, as autistic girls and women went largely under the radar until relatively recently. Moreover, autistic women often experience concurrent mental health difficulties related to the stress of living in a neurotypical world that expects social competency, especially those diagnosed later in life (Atherton et al. Citation2021).

For most women, the late diagnosis proved valuable, as did having long-term relationships with close friends and family members, both autistic and non-autistic, who accepted and encouraged them to achieve their goals, without criticising their ‘quirky’ traits (Kock et al. Citation2019; Leedham et al. Citation2020; Webster and Garvis Citation2017). However, a small number worried that the ‘label’ may be seen by others as shameful and may limit their future potential (Ho Citation2004; Leedham et al. Citation2020). A diagnosis not only allows a person to reflect on themselves differently, but it can also change the way others perceive them and consequently treat them (Becker Citation2008; Goffman Citation1963). Unfortunately, when someone constantly hears negative messages about their value and ability, it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy as they internalise these judgements and start to believe them (Jussim et al. Citation2000; Merton Citation1948; Reeve Citation2004). The reaction of a person to being diagnosed with autism may depend on when the diagnosis is given and under what circumstances. Perhaps most women in this review found it a positive experience because they voluntarily sought a diagnosis for themselves in adulthood, rather than ‘receiving’ the label in childhood, without being well informed (Molloy and Vasil Citation2002).

Developing a new ‘autistic identity’

The growing popularity of social media and the neurodiversity paradigm during the last decade has increased the number of autistic women seeking out like-minded others and connecting and sharing their experiences; empowering them, increasing their well-being and reducing feelings of alienation (Milton and Sims Citation2016; Straus Citation2013; Webster and Garvis Citation2017). In Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy (Citation2016), several women described the importance of finding new autistic friends online who accepted and understood them, highlighting the importance of informal peer support: ‘Something that I really appreciate about having the diagnosis is actually being in this club now where people talk about their experiences and having so many echoes of my own’ (3289). Socialising with other autistic women online may have helped them construct a positive ‘autistic identity’, which otherwise may have proved difficult due to the competing discourse around autism, particularly the powerful medical or ‘deficit’ model (Bagatell Citation2007; Davidson Citation2008a). However, neurodiversity represents autism as a cognitive style, rather than as a ‘discreditable’ deficit that should be overcome, and this concept seemed to have encouraged the women to redefine autism as a distinct cultural identity, positively influencing their self-image and encouraging them to disclose to others (Haney and Cullen Citation2017; Tan Citation2018; Wright, Spikins, and Pearson Citation2020).

Many of the women felt more able and free to be themselves, rather than an idealised version of what others expected them to be, and so they were absolved from having to wear a mask, particularly around their autistic friends (Leedham et al. Citation2020). Developing a positive ‘autistic identity’ appears to have increase personal and collective self-esteem, offering a protective mechanism for psychological wellbeing (Milton and Sims Citation2016; Tan Citation2018). In a society where autistic people have traditionally been devalued, this identity construction involves resisting normalising ideology and feeds back into our understanding of autism via the looping effect, as discussed earlier (Hacking Citation2006; O’Dell et al. Citation2016). Hopefully a greater societal appreciation of autism and autistic behavioural traits may reduce the compulsion for autistic females to mask their authentic selves (Hodge, Rice, and Reidy Citation2019).

For some women, receiving a diagnosis seems to have encouraged them to set goals based on their unique strengths, assert their opinions, ask for support when needed, and realise their potential (Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy Citation2016; Leedham et al. Citation2020; Webster and Garvis Citation2017). One key strength that was frequently mentioned was the ability to ‘hyperfocus’ on interests; a result of their enhanced processing using a cognitive strategy called monotropism (Murray Citation2018; Murray, Lesser, and Lawson Citation2005). Some autistic individuals tend to intensely focus on a task that they are particularly interested in, to the point where the rest of the world seems to disappear and any other, less interesting, tasks get ignored (Grant and Kara Citation2021). Working on, or building a career from, activities of specific interest to the women provided a sense of stimulation and fulfilment, despite the challenges the women had faced in the past (Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy Citation2016; Krieger et al. Citation2012; O’Neil Citation2008; Stagg and Belcher Citation2019).

Although the mental health of a few women continued to fluctuate after they were diagnosed, many seemed to have developed more self-compassion and an increased sense of agency. For example, some women managed to gain the confidence to end unsupportive and abusive relationships and friendships (Webster and Garvis Citation2017). One woman felt less anxious after her diagnosis: ‘I don’t get as much anxiety as I used to … because I’ve got better understanding of—and because I understand it better I’m actually able to deal with it better … so I build strategies around that really’ (Leedham et al. Citation2020, 142). An increase in the women’s autonomy was indicated by their decision-making and efforts to improve their quality of life. This illustrated the importance of measures that may increase their sense of agency and awareness that they can succeed.

Developing a positive social identity and contacting others in the autism community has the potential for autistic women to increase their self-esteem and to reduce feelings of isolation and alienation (Cameron Citation2014a; Cooper, Smith, and Russell Citation2017). Swain and French (Citation2000) proposed a new model called the affirmation model that embraces positive social identities and respects the diverse ways of being in society; challenging presumptions about the ‘tragedy’ of disability (Cameron Citation2014b; Swain and French Citation2008). By contacting the autism community and sharing their narratives about their lives and diagnostic journey, the women in these studies were reframing their sense-making narrative in a neurodiversity-affirming way (Kapp Citation2020; Swain and Cameron Citation1999).

Barriers to support

While seeking a diagnosis in adulthood, the women in the study by Bargiela, Steward, and Mandy (Citation2016) felt that healthcare professionals lacked an understanding of the way autistic traits present in women. Some women had found that General Practitioners (GPs) and psychiatrists had dismissed their concerns: ‘When I mentioned the possibility to my psychiatric nurse, she actually laughed at me…I asked my mum, who was a GP at the time…if she thought I was autistic. She said, ‘Of course not’’ (ibid, 3286). As GPs are more used to identifying autistic features in boys, they may not initially think of autism when they meet a woman with social difficulties in their clinic, but instead think of social anxiety or depression, for which medication can be prescribed (Fletcher-Watson and Happé Citation2019). Studies have revealed a large gender disparity in autism referral and diagnosis (Dworzynski et al. Citation2012; Russell, Steer, and Golding Citation2011). This could either reflect a significant gender bias by clinicians or the fact that females are more motivated and successful at emulating non-autistic behaviour (Hurley Citation2014).

Another possibility for the gender disparity could be that clinicians have been under the impression that women could not be autistic due to misinterpreting a theory about extreme male brains. The theory was informally suggested by Hans Asperger in 1944, who stated that ‘the autistic personality is an extreme variant of male intelligence. In the autistic individual, the male pattern is exaggerated to the extreme.’ (Frith Citation1991, 84). More recently, the Extreme Male Brain (EMB) theory hypothesised that autistic brains were extreme forms of the male brain, as they were better at analysing and systemising which are male traits, but less good at empathising which is a female trait (Baron-Cohen Citation2002). Further research suggested a relationship between pre-natal exposure to the sex-linked hormone testosterone in amniotic fluid and autistic traits (Baron-Cohen et al. Citation2015). However, this theory was heavily criticised for failing to distinguish between sex and gender; rather it subsumed one into the other (Butler Citation2006). The theory relies on a binary model of brains which suggests that differences in social skills between males and females are biologically determined, but fails to account for cultural expectations and learnt behaviour (Jack Citation2011).

An autism diagnosis may function as a key to unlocking legal and financial support that would otherwise not be accessible, including welfare benefits, reasonable adjustments in the workplace, protections, rights, services, social groups, information and educational support (Booth Citation2016). There was an expectation amongst the women in the review that some post-diagnostic social care support would be available, but unfortunately, their attempts to access it were unsuccessful (Griffith et al. Citation2012). Women felt that this was due to a lack of specific adult autism services: ‘… I don’t fit mental health. I don’t fit learning disability. I just fall through the gaps between departments, whether it’s in the health service or social services. I just don’t fit anywhere’ (ibid, 540).

In workplace environments, assessments should be carried out and recommendations made for reasonable adjustments, for example to lessen specific sensory stimuli that may be a hindrance to an autistic individual’s work performance and wellbeing (Booth Citation2016). However, the women had come across a general lack of autism awareness by their employers who did not understand or appreciate the kind of difficulties autistic people may experience in the workplace or what accommodations may be required (Griffith et al. Citation2012; Hurlbutt and Chalmers Citation2004). In fact, many felt that their difficulties in socially interacting with co-workers had led to their dismissal from a post in the past. A few of the women were so disheartened that they stopped looking for work altogether:

‘It’s interacting … they come up to you and start asking you questions about your problems, see, I may make a comment, I may do something inappropriate and it builds up and then the employer … usually it leads to a reason for dismissal’ (Griffith et al. Citation2012, 539).

Limitations

Only the main issues described by participating autistic women were highlighted, so unfortunately other potentially important nuances contained within their personal stories may have been missed (Finfgeld-Connett Citation2010). The criteria for inclusion in the review were women who had been diagnosed in adulthood, so undiagnosed and self-diagnosed autistic women, autistic individuals with other gender identities and individuals diagnosed in childhood were not represented (Brugha et al. Citation2011). The countries of origin of all nine articles were from the minority world, traditionally known as ‘developed countries’. Data on the women’s ethnicity group were only included in one study, in which all the participating women were White British (Smith and Sharp Citation2013). It is possible that minority ethnic groups may have been under-represented in this review. Demographic information about the participants from the nine studies were limited and not consistent in all of the studies, which meant that we could not apply the full framework of intersectionality to any other aspects of the women’s identity, such as ethnicity or class, that may have empowered or disadvantaged them (Kim Citation2012). A recommendation for future research would be to study the impact of an autism diagnosis on autistic women’s intimate relationships, such as with their partners, children or parents (Kock et al. Citation2019).

Conclusions

Receiving the diagnostic label of autism proved to be a positive ‘turning-point’ for many of the women who participated in the nine studies reviewed. The identity of ‘autism’ provided the women with an explanatory framework which allowed them to rewrite their biography and make sense of their experiences. The women’s sense-making narratives were affirming and recognised autism as an intrinsic part of them. These narratives may be viewed as an act of resistance to the metanarrative of autism that have been historically rooted in medicalised approaches to autism (Loftis Citation2021). In its place, the autistic women in the studies used the paradigm of neurodiversity to interpret and construct a new autistic identity which accepted and valued all types of human diversity and challenged the dominant ideology of the deficit-based medical model. The women expressed the importance of communicating with other autistic individuals following a diagnosis, especially other autistic women. It provided opportunities for mutual recognition and demonstrated how diversity is something to be celebrated and embraced. The women developed a positive identity by virtue of being autistic and proudly described their autistic strengths that made them unique.

However, the studies did suggest that health and social care professionals were not always able to recognise, refer, and support autistic women and were unaware of autistic women’s specific challenges. By focusing on the intersection of autism and gender, the review revealed practices of stigma and marginalisation that had affected the women’s psycho-emotional disablement. The autistic women were routinely disabled by societal, attitudinal, and structural barriers and experienced frequent discrimination, disadvantage, and social exclusion in employment and within the broader society. Following their diagnosis, the women used their new positive autistic identity to overcome some of these barriers, to facilitate social interaction with other autistic people, and to access and obtain better outcomes for themselves. Further exploration of the lived experiences of autistic women is essential for conceptualising potential approaches to support, particularly as their ‘voices’ have been largely missing in qualitative studies (Howlin et al. Citation2015; Milton Citation2014). Approaches could include the following:

At the point of diagnosis, information should be given on autistic female social groups, helplines, local voluntary groups, autobiographical books on autism, useful websites, blogs and social media groups

Counselling support should be made available for women following a late autism diagnosis, since the identification may be traumatic for some

Support service staff should help to develop an empowering and positive autistic identity for women, for example by providing first-hand accounts from autistic individuals and introducing the concept of neurodiversity

Acknowledgements

The researchers are indebted to the reviewers for their comprehensive feedback and guidance on this review. It enabled the first author to greatly improve her writing and assisted in her personal development as a doctoral researcher.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Atherton, G., E. Edisbury, A. Piovesan, and L. Cross. 2021. “Autism through the Ages: A Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding How Age and Age of Diagnosis Affect Quality of Life.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders doi:10.1007/s10803-021-05235-x.

- Bagatell, Nancy. 2007. “Orchestrating Voices: Autism, Identity and the Power of Discourse.” Disability & Society 22 (4): 413–426. doi:10.1080/09687590701337967.

- Baines, AnnMarie D. 2012. “Positioning, Strategizing, and Charming: How Students with Autism Construct Identities in Relation to Disability.” Disability & Society 27 (4): 547–561. doi:10.1080/09687599.2012.662825.

- Baker, Dana Lee. 2006. “Neurodiversity, Neurological Disability and the Public Sector: Notes on the Autism Spectrum.” Disability & Society 21 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1080/09687590500373734.

- Bargiela, S., R. Steward, and W. Mandy. 2016. “The Experiences of Late-Diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 46 (10): 3281–3294. doi:10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8.

- Baron-Cohen, Simon. 2002. “The Extreme Male Brain Theory of Autism.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 6 (6): 248–254. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01904-6.

- Baron-Cohen, Simon., Bonnie. Au-Yeung, Bent. Nørgaard-Pedersen, David M. Hougaard, Morsi W. Abdallah, Lars. Melgaard, Arieh. S. Cohen, Bhisma. Chakrabarti, Liliana. Ruta, Michael, and V. Lombardo. 2015. “Elevated Fetal Steroidogenic Activity in Autism.” Molecular Psychiatry 20 (3): 369–376. doi:10.1038/mp.2014.48.

- Bê, Ana. 2014. “Feminist Disability Studies.” In Disability Studies: A Student’s Guide, edited by Colin Cameron, 59–62. London: Sage.

- Beardon, Luke. 2017. Autism and Asperger Syndrome in Adults. UK: Hachette.

- Beck, J. S., R. A. Lundwall, T. Gabrielsen, J. C. Cox, and M. South. 2020. “Looking Good but Feeling Bad: "Camouflaging" Behaviors and Mental Health in Women with Autistic Traits.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 24 (4): 809–821. doi:10.1177/1362361320912147.

- Becker, Howard S. 2008. Outsiders; Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Begum, Nasa. 1992. “Disabled Women and the Feminist Agenda.” Feminist Review 40 (1): 70–84. doi:10.2307/1395278.

- Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, Hanna., Marianthi. Kourti, David. Jackson-Perry, Charlotte. Brownlow, Kirsty. Fletcher, Daniel. Bendelman, and Lindsay. O’Dell. 2019. “Doing It Differently: Emancipatory Autism Studies within a Neurodiverse Academic Space.” Disability & Society 34 (7-8): 1082–1101. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.1603102.

- Blume, Harvey. 1997. Autism & the Internet or It’s the Wiring, Stupid. Massachusetts: Media In Transition.

- Boland, Angela. Gemma. Cherry, and Rumona. Dickson. 2017. Doing a Systematic Review: A Student’s Guide. London: Sage.

- Booth, Janine. 2016. Autism Equality in the Workplace: Removing Barriers and Challenging Discrimination. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Bottema-Beutel, Kristen., Steven K. Kapp, Jessica Nina. Lester, Noah J. Sasson, and Brittany N. Hand. 2021. “Avoiding Ableist Language: Suggestions for Autism Researchers.” Autism in Adulthood 3 (1): 18–29. doi:10.1089/aut.2020.0014.

- Bowleg, L. 2012. “The Problem with the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality-an Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health.” American Journal of Public Health 102 (7): 1267–1273. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria. Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage.

- Brugha, T. S., N. Spiers, J. Bankart, S. A. Cooper, S. McManus, F. J. Scott, J. Smith, and F. Tyrer. 2016. “Epidemiology of Autism in Adults across Age Groups and Ability Levels.” The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science 209 (6): 498–503. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.115.174649.

- Brugha, T. S., S. McManus, J. Bankart, F. Scott, S. Purdon, J. Smith, P. Bebbington, R. Jenkins, and H. Meltzer. 2011. “Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Adults in the Community in England.” Archives of General Psychiatry 68 (5): 459–465. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.38.

- Bumiller, K. 2008. “Quirky Citizens: Autism, Gender, and Reimagining Disability.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 33 (4): 967–991. doi:10.1086/528848.

- Bury, Michael. 1982. “Chronic Illness as Biographical Disruption.” Sociology of Health & Illness 4 (2): 167–182. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939.

- Butler, Judith. 2006. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. London: Routledge.

- Cameron, Colin. 2014a. “Alienation.” In Disability Studies: A Student’s Guide, edited by Colin Cameron, 11–14. London: Sage.

- Cameron, Colin. 2014b. “Developing an Affirmative Model of Disability and Impairment.” In Disabling Barriers–Enabling Environments, edited by John Swain, Colin Barnes and Carol Thomas, 22–28. London: Sage.

- Castells, M. 2009. The Power of Identity. Vol. 2, the Information Age: Society, Economy, and Culture. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Chapman, Robert. 2020. “Defining Neurodiversity for Research and Practice.” In Neurodiversity Studies: A New Critical Paradigm, edited by H. B. Rosqvist, N. Chown and A. Stenning, 218–220. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Chown, Nicholas. 2014. “More on the Ontological Status of Autism and Double Empathy.” Disability & Society 29 (10): 1672–1676. doi:10.1080/09687599.2014.949625.

- Chown, Nick., Jackie. Robinson, Luke. Beardon, Jillian. Downing, Liz. Hughes, Julia. Leatherland, Katrina. Fox, Laura. Hickman, and Duncan. MacGregor. 2017. “Improving Research about Us, with Us: A Draft Framework for Inclusive Autism Research.” Disability & Society 32 (5): 720–734. doi:10.1080/09687599.2017.1320273.

- Conrad, Peter. 2007. The Medicalization of Society: On the Transformation of Human Conditions into Treatable Disorders. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Cooper, Kate., Laura G. E. Smith, and Ailsa. Russell. 2017. “Social Identity, Self-Esteem, and Mental Health in Autism.” European Journal of Social Psychology 47 (7): 844–854. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2297.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1 (8): 139–167.

- Creswell, John W, and Cheryl N. Poth. 2016. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. London: Sage.

- Crow, Maxx. 2017. "Anarchism: In the Conversations of Neurodiversity." https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/maxx-crow-anarchism-in-the-conversations-of-neurodiversity.

- Davidson, J., and S. Tamas. 2016. “Autism and the Ghost of Gender.” Emotion, Space and Society 19: 59–65. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2015.09.009.

- Davidson, Joyce. 2008a. “Autistic Culture Online: Virtual Communication and Cultural Expression on the Spectrum.” Social & Cultural Geography 9 (7): 791–806. doi:10.1080/14649360802382586.

- Davidson, Joyce. 2008b. “In a World of Her Own…’: Re-Presenting Alienation and Emotion in the Lives and Writings of Women with Autism.” Gender, Place & Culture 14 (6): 659–677. doi:10.1080/09663690701659135.

- Davis, Kathy. 2008. “Intersectionality as Buzzword.” Feminist Theory 9 (1): 67–85. doi:10.1177/1464700108086364.

- Dawson, Michelle., Isabelle. Soulières, Morton Ann. Gernsbacher, and Laurent. Mottron. 2007. “The Level and Nature of Autistic Intelligence.” Psychological Science 18 (8): 657–662. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01954.x.

- den Houting, J. 2019. “Neurodiversity: An Insider’s Perspective.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 23 (2): 271–273. doi:10.1177/1362361318820762.

- Dixon-Woods, Mary, Shona Agarwal, David Jones, Bridget Young, and Alex Sutton. 2005. “Synthesising Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence: A Review of Possible Methods.” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10 (1): 45–53. doi:10.1177/135581960501000110. 15667704

- Dowley, Becky. 2016. “The Development and Importance of the Autistic Voice in Understanding Autism and Enhancing Services.” Good Autism Practice 17 (1): 48–53.

- Dworzynski, K., A. Ronald, P. Bolton, and F. Happe. 2012. “How Different Are Girls and Boys above and below the Diagnostic Threshold for Autism Spectrum Disorders?” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 51 (8): 788–797. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.018.

- Fine, Michelle, and Adrienne. Asch. 1988. Women with Disabilities: Essays in Psychology, Culture, and Politics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. 2010. “Generalizability and Transferability of Meta-Synthesis Research Findings.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 66 (2): 246–254. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05250.x.

- Finley, L. 2002. “Outing’ the Researcher: The Provenance, Process, and Practice of Reflexivity.” Qualitative Health Research 12 (4) doi:10.1177/104973202129120052.

- Fletcher-Watson, S., J. Adams, K. Brook, T. Charman, L. Crane, J. Cusack, S. Leekam, D. Milton, J. R. Parr, and E. Pellicano. 2019. “Making the Future Together: Shaping Autism Research through Meaningful Participation.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 23 (4): 943–953. doi:10.1177/1362361318786721.

- Fletcher-Watson, Sue, and Francesca. Happé. 2019. Autism: A New Introduction to Psychological Theory and Current Debate. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Foucault, Michel. 1975. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London, UK: Penguin.

- Franks, M. 2002. “Feminisms and Cross-Ideological Feminist Social Research: Standpoint, Situatedness and Positionality—Developing Cross-Ideological Feminist Research.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 3: 38–50.

- Frith, Uta. 1991. Autism and Asperger Syndrome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Frost, Nollaig. 2016. Practising Research: Why You’re Always Part of the Research Process Even When You Think You’re Not. London: Palgrave.

- Frost, Nollaig., and Amanda. Holt. 2014. “Mother, Researcher, Feminist, Woman: Reflections on “Maternal Status” as a Researcher Identity.” Qualitative Research Journal 14 (2): 90–102. doi:10.1108/QRJ-06-2013-0038.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. 2002. “Integrating Disability, Transforming Feminist Theory.” NWSA Journal 14 (3): 1–32. doi:10.1353/nwsa.2003.0005.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. 2005. “Feminist Disability Studies.” Signs 30 (2): 1567–1587. doi:10.1086/423352.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. 2017. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. USA: Columbia University Press.

- Gernsbacher, M. A. 2017. “Editorial Perspective: The Use of Person-First Language in Scholarly Writing May Accentuate Stigma.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 58 (7): 859–861. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12706.

- Gillman, Maureen., Bob. Heyman, and John. Swain. 2000. “What’s in a Name? The Implications of Diagnosis for People with Learning Difficulties and Their Family Carers.” Disability & Society 15 (3): 389–409. doi:10.1080/713661959.

- Ginsburg, E. K., and Donald E. Pease. 1996. Passing and the Fictions of Identity. USA: Duke University Press.

- Gobbo, Ken., and Solvegi. Shmulsky. 2016. “Autistic Identity Development and Postsecondary Education.” Disability Studies Quarterly 36 (3) doi:10.18061/dsq.v36i3.5053.

- Goffman, E. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London: Penguin Books.

- Gould, J., and J. Ashton-Smith. 2011. “Missed Diagnosis or Misdiagnosis?: Girls and Women on the Autism Spectrum.” Good Autism Practice 12 (1): 34.

- Grant, Aimee., and Helen. Kara. 2021. “Considering the Autistic Advantage in Qualitative Research: The Strengths of Autistic Researchers.” Contemporary Social Science 16 (5): 589–603. doi:10.1080/21582041.2021.1998589.

- Griffith, G. M., V. Totsika, S. Nash, and R. P. Hastings. 2012. “ ‘I just don’t fit anywhere’: support experiences and future support needs of individuals with Asperger syndrome in middle adulthood.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 16 (5): 532–546. doi:10.1177/1362361311405223.

- Hacking, I. 2009. “Autistic Autobiography.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1522): 1467–1473. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0329.

- Hacking, Ian. 1995. “The Looping Effects of Human Kinds.” In Causal Cognition: A Multidisciplinary Approach, edited by Dan Sperber, David Premack and Ann James Premack. USA: Oxford University Press.

- Hacking, Ian. 2006. “Making up People.” London Review of Books 28 (16): 23–26.

- Hall, Kim Q. 2015. “New Conversations in Feminist Disability Studies: Feminism, Philosophy, and Borders.” Hypatia 30 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1111/hypa.12136.

- Haney, J. L., and J. A. Cullen. 2017. “Learning about the Lived Experiences of Women with Autism from an Online Community.” Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation 16 (1): 54–73. doi:10.1080/1536710X.2017.1260518.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. doi:10.2307/3178066.

- Heasman, B., and A. Gillespie. 2018. “Perspective-Taking is Two-Sided: Misunderstandings between People with Asperger’s Syndrome and Their Family Members.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 22 (6): 740–750. doi:10.1177/1362361317708287.

- Ho, Anita. 2004. “To Be Labelled, or Not to Be Labelled: That is the Question.” British Journal of Learning Disabilities 32 (2): 86–92. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3156.2004.00284.x.

- Hodge, Nick., Emma J. Rice, and Lisa. Reidy. 2019. “They’re Told All the Time They’re Different’: How Educators Understand Development of Sense of Self for Autistic Pupils.” Disability & Society 34 (9-10): 1353–1378. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.1594700.

- Howard, K., N. Katsos, and J. Gibson. 2019. “Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in Autism Research.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 23 (7): 1871–1876. doi:10.1177/1362361318823902.

- Howlin, Patricia., Joanne. Arciuli, Sander. Begeer, Jon. Brock, Kristina. Clarke, Debra. Costley, Peter. di Rita, et al. 2015. “Research on Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Roundtable Report.” Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 40 (4): 388–393. doi:10.3109/13668250.2015.1064343.

- Hughes, Elizabeth. 2015. “Does the Different Presentation of Asperger Syndrome in Girls Affect Their Problem Areas and Chances of Diagnosis and Support?” Autonomy, the Critical Journal of Interdisciplinary Autism Studies 1 (4)

- Hurlbutt, Karen., and Lynne. Chalmers. 2004. “Employment and Adults with Asperger Syndrome.” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 19 (4): 215–222. doi:10.1177/10883576040190040301.

- Hurley, Elisabeth. 2014. Ultraviolet Voices: Stories of Women on the Autism Spectrum. UK: Autism West Midlands.

- Huws, J. C., and R. S. P. Jones. 2010. “They Just Seem to Live Their Lives in Their Own Little World’: Lay Perceptions of Autism.” Disability & Society 25 (3): 331–344. doi:10.1080/09687591003701231.

- Jack, Jordynn. 2011. “The Extreme Male Brain?" Incrementum and the Rhetorical Gendering of Autism.” Disability Studies Quarterly 31 (3) doi:10.18061/dsq.v31i3.1672.

- Jussim, Lee. Polly. Palumbo, Alison. Smith, and Stephanie. Madon. 2000. “Stigma and Self-Fulfilling Prophecies.” In The Social Psychology of Stigma, edited by T. Heatherton, R. Kleck, M. R. Hebl and J. G. Hull, 374–418. New York: Guilford Press.

- Kalei Kanuha, Valli. 1999. “The Social Process of ‘Passing’ to Manage Stigma: Acts of Internalized Oppression or Acts of Resistance?” Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 26 (4): 27.

- Kanfiszer, L., F. Davies, and S. Collins. 2017. “‘I was just so different’: The Experiences of Women Diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder in Adulthood in Relation to Gender and Social relationships.” Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice 21 (6): 661–669. doi:10.1177/1362361316687987.

- Kapp, S. K., K. Gillespie-Lynch, L. E. Sherman, and T. Hutman. 2013. “Deficit, Difference, or Both? Autism and Neurodiversity.” Developmental Psychology 49 (1): 59–71. doi:10.1037/a0028353.

- Kapp, S. K., R. Steward, L. Crane, D. Elliott, C. Elphick, E. Pellicano, and G. Russell. 2019. “‘People should be allowed to do what they like’: Autistic adults’ views and experiences of stimming.” Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice 23 (7): 1782–1792. doi:10.1177/1362361319829628.

- Kapp, Steven K. 2020. Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kenny, L., C. Hattersley, B. Molins, C. Buckley, C. Povey, and E. Pellicano. 2016. “Which Terms Should Be Used to Describe Autism? Perspectives from the Uk Autism Community.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 20 (4): 442–462. doi:10.1177/1362361315588200.

- Kim, Cynthia. 2013. I Think I Might Be Autistic: A Guide to Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis and Self-Discovery for Adults. New York: Narrow Gauge.

- Kim, Hyun Uk. 2012. “Autism across Cultures: Rethinking Autism.” Disability & Society 27 (4): 535–545. doi:10.1080/09687599.2012.659463.

- King, Deborah K. 1988. “Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 14 (1): 42–72. doi:10.1086/494491.

- Kock, Elizabeth., Andre. Strydom, Deirdre. O’Brady, and Digby. Tantam. 2019. “Autistic Women’s Experience of Intimate Relationships: The Impact of an Adult Diagnosis.” Advances in Autism 5 (1): 38–49. doi:10.1108/AIA-09-2018-0035.

- Krieger, B., A. Kinebanian, B. Prodinger, and F. Heigl. 2012. “Becoming a Member of the Work Force: Perceptions of Adults with Asperger Syndrome.” Work (Reading, Mass.) 43 (2): 141–157. doi:10.3233/WOR-2012-1392.

- Leedham, A., A. R. Thompson, R. Smith, and M. Freeth. 2020. “ ‘I Was Exhausted Trying to Figure It Out’: The Experiences of Females Receiving an Autism Diagnosis in Middle to Late Adulthood.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 24 (1): 135–146. doi:10.1177/1362361319853442.

- Limburg, Joanne. 2016. “But That’s Just What You Can’t Do’: Personal Reflections on the Construction and Management of Identity following a Late Diagnosis of Asperger Syndrome.” Life Writing 13 (1): 141–150. doi:10.1080/14484528.2016.1120639.

- Lingsom, Susan. 2008. “Invisible Impairments: Dilemmas of Concealment and Disclosure.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 10 (1): 2–16. doi:10.1080/15017410701391567.

- Linton, Kristen F. 2014. “Clinical Diagnoses Exacerbate Stigma and Improve Self-Discovery according to People with Autism.” Social Work in Mental Health 12 (4): 330–342. doi:10.1080/15332985.2013.861383.

- Loftis, Sonya Freeman. 2021. “The Metanarrative of Autism: Eternal Childhood and the Failure of Cure.” In Metanarratives of Disability, 94–105. London: Routledge.

- MacLeod, Andrea. 2019. “Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Ipa) as a Tool for Participatory Research within Critical Autism Studies: A Systematic Review.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 64: 49–62. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2019.04.005.

- MacLeod, Andrea., Ann. Lewis, and Christopher. Robertson. 2013. “Why Should I Be like Bloody Rain Man?!’ Navigating the Autistic Identity.” British Journal of Special Education 40 (1): 41–49. doi:10.1111/1467-8578.12015.

- Madill, Anna., Abbie. Jordan, and Caroline. Shirley. 2000. “Objectivity and Reliability in Qualitative Analysis: Realist, Contextualist and Radical Constructionist Epistemologies.” British Journal of Psychology 91 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1348/000712600161646|.

- May, Tim, and Beth. Perry. 2017. Reflexivity: The Essential Guide. London: Sage.

- Merton, Robert K. 1948. “The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy.” The Antioch Review 8 (2): 193–210. doi:10.2307/4609267.

- Milton, D. E. 2014. “Autistic Expertise: A Critical Reflection on the Production of Knowledge in Autism Studies.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 18 (7): 794–802. doi:10.1177/1362361314525281.

- Milton, Damian E. M. 2012. “On the Ontological Status of Autism: The ‘Double Empathy Problem.” Disability & Society 27 (6): 883–887. doi:10.1080/09687599.2012.710008.

- Milton, Damian. 2013. “Filling in the Gaps’: A Micro-Sociological Analysis of Autism.” Autonomy, the Critical Journal of Interdisciplinary Autism Studies 1 (2)

- Milton, Damian. 2017. A Mismatch of Salience: Explorations of the Nature of Autism from Theory to Practice. UK: Pavilion Press.

- Milton, Damian., and Lyte. Moon. 2012. “The Normalisation Agenda and the Psycho-Emotional Disablement of Autistic People.” Autonomy, the Critical Journal of Interdisciplinary Autism Studies 1 (1)

- Milton, Damian., and Tara. Sims. 2016. “How is a Sense of Well-Being and Belonging Constructed in the Accounts of Autistic Adults?” Disability & Society 31 (4): 520–534. doi:10.1080/09687599.2016.1186529.

- Mohamed, Kharnita., and Tamara. Shefer. 2015. “Gendering Disability and Disabling Gender: Critical Reflections on Intersections of Gender and Disability.” Agenda 29 (2): 2–13. doi:10.1080/10130950.2015.1055878.

- Moher, David, Larissa. Shamseer, Mike. Clarke, Davina. Ghersi, Alessandro. Liberati, Mark. Petticrew, Paul. Shekelle, and Lesley A. Stewart, PRISMA-P Group 2015. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (Prisma-P) 2015 Statement.” Systematic Reviews 4 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

- Molloy, Harvey., and Latika. Vasil. 2002. “The Social Construction of Asperger Syndrome: The Pathologising of Difference?” Disability & Society 17 (6): 659–669. doi:10.1080/0968759022000010434.

- Morris, Jenny. 1996. Encounters with Strangers: Feminism and Disability. London: The Women’s Press.

- Murray, D., M. Lesser, and W. Lawson. 2005. “Attention, Monotropism and the Diagnostic Criteria for Autism.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 9 (2): 139–156. doi:10.1177/1362361305051398.

- Murray, Dinah. 2018. “Monotropism – an Interest Based account of Autism.” In Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders 1–3.

- Murray, Dinah. 2020. “Dimensions of Difference.” In The Neurodiversity Reader: Exploring Concepts, Lived Experience and Implications for Practice, edited by Damian Milton, 7–17. Shoreham by Sea, UK: Pavilion.

- Murray, Stuart. 2009. “Autism Functions/the Function of Autism.” Disability Studies Quarterly 30 (1) doi:10.18061/dsq.v30i1.1048.

- Murray, Stuart. 2012. Autism. New York: Routledge.

- Nadesan, Majia Holmer. 2013. Constructing Autism: Unravelling The’truth’and Understanding the Social. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- O’Dell, Lindsay., Hanna Bertilsdotter. Rosqvist, Francisco. Ortega, Charlotte. Brownlow, and Michael. Orsini. 2016. “Critical Autism Studies: Exploring Epistemic Dialogues and Intersections, Challenging Dominant Understandings of Autism.” Disability & Society 31 (2): 166–179. doi:10.1080/09687599.2016.1164026.

- O’Neil, Sara. 2008. “The Meaning of Autism: Beyond Disorder.” Disability & Society 23 (7): 787–799. doi:10.1080/09687590802469289.

- Piepmeier, Alison., Amber. Cantrell, and Ashley. Maggio. 2014. “Disability is a Feminist Issue: Bringing Together Women’s and Gender Studies and Disability Studies.” Disability Studies Quarterly 34 (2) doi:10.18061/dsq.v34i2.4252.

- Portway, Suzannah M., and Barbara. Johnson. 2005. “Do You Know I Have Asperger’s Syndrome? Risks of a Non-Obvious Disability.” Health, Risk & Society 7 (1): 73–83. doi:10.1080/09500830500042086.

- Punshon, C., P. Skirrow, and G. Murphy. 2009. “The Not Guilty Verdict: Psychological Reactions to a Diagnosis of Asperger Syndrome in Adulthood.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 13 (3): 265–283. doi:10.1177/1362361309103795.

- Purdie-Vaughns, Valerie., and Richard P. Eibach. 2008. “Intersectional Invisibility: The Distinctive Advantages and Disadvantages of Multiple Subordinate-Group Identities.” Sex Roles 59 (5-6): 377–391. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9424-4.

- Raymaker, Dora, and Christina. Nicolaidis. 2013. “Participatory Research with Autistic Communities: Shifting the System.” In Worlds of Autism: Across the Spectrum of Neurological Difference, edited by Joyce Davidson and Michael Orsini, 169–188. UK: University of Minnesota Press.

- Reeve, D. 2004. “Psycho-Emotional Dimensions of Disability and the Social Model.” In Implementing the Social Model of Disability: Theory and Research, edited by C. Barnes and G. Mercer. Leeds: The Disability Press.

- Robertson, Scott Michael. 2009. “Neurodiversity, Quality of Life, and Autistic Adults: Shifting Research and Professional Focuses onto Real-Life Challenges.” Disability Studies Quarterly 30 (1) doi:10.18061/dsq.v30i1.1069.

- Runswick-Cole, Katherine. 2014. “Us’ and ‘Them’: The Limits and Possibilities of a ‘Politics of Neurodiversity’ in Neoliberal Times.” Disability & Society 29 (7): 1117–1129. doi:10.1080/09687599.2014.910107.

- Russell, G., C. Steer, and J. Golding. 2011. “Social and Demographic Factors That Influence the Diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorders.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 46 (12): 1283–1293. doi:10.1007/s00127-010-0294-z.

- Russell, G., S. Collishaw, J. Golding, S. E. Kelly, and T. Ford. 2015. “Changes in Diagnosis Rates and Behavioural Traits of Autism Spectrum Disorder over Time.” BJPsych Open 1 (2): 110–115. doi:10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.000976.

- Russell, Ginny. 2021. The Rise of Autism: Risk and Resistance in the Age of Diagnosis. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Sasson, N. J., and K. E. Morrison. 2019. “First Impressions of Adults with Autism Improve with Diagnostic Disclosure and Increased Autism Knowledge of Peers.” Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice 23 (1): 50–59. doi:10.1177/1362361317729526.

- Sasson, N. J., D. J. Faso, J. Nugent, S. Lovell, D. P. Kennedy, and R. B. Grossman. 2017. “Neurotypical Peers Are Less Willing to Interact with Those with Autism Based on Thin Slice Judgments.” Scientific Reports 7: 40700. doi:10.1038/srep40700.

- Saxe, Amanda. 2017. “The Theory of Intersectionality: A New Lens for Understanding the Barriers Faced by Autistic Women.” Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 6 (4): 153–178. doi:10.15353/cjds.v6i4.386.

- Scuro, Jennifer. 2017. Addressing Ableism: Philosophical Questions via Disability Studies. USA: Lexington Books.

- Shakespeare, Tom. 2010. “The Social Model of Disability.” In The Disability Studies Reader, edited by Lennard J. Davis, 266–273. New York: Routledge.

- Simpson, H, University of Oxford. 2019. “Disability, Neurodiversity, and Feminism.” Journal of Feminist Scholarship 16 (16): 81–83. (Fall): doi:10.23860/jfs.2019.16.10.

- Sinclair, Jim. 2013. “Why I Dislike “Person First” Language.” Autonomy, the Critical Journal of Interdisciplinary Autism Studies 1 (2): 1–2.