Abstract

This research engages Autoethnographic Participatory Action Research (APAR) to explore family communication within and between families of autistic young people in emerging adolescence. Autistic young people often have diverse ways of communicating and differences between family members’ communication can result in barriers to family interaction. Much of the existing research in communication in autistic young people within family settings centres around younger children and little is known, therefore, about communication in families of autistic children in middle childhood as they meet the challenges of adolescence. This parent-led study engaged mothers from five families as co-researchers to explore communication within their own families. The action-reflection cycle of the APAR methodology proved to be an effective vehicle for gaining deeper understandings of the young person’s unique situated communication. Findings presented in this article identify the importance of time and space as key enablers to inclusive communication within families.

Points of interest

This article explores how autoethnographic participatory action research (APAR), carried out by five mothers with family members which include autistic young people, helped understand communicative interactions.

Mothers from each family met in a group to talk about the different ways communication occurred within their families. They kept a journal, worked with other family members and added notes and drawings from their young people.

Making notes in their journal and talking about communication helped the mothers to understand how they could all, as a family, improve communication with their autistic young people.

They found that giving more time and space for communication helped autistic young people to be included in communication in their home. This is important to make sure they feel valued and listened to as they are growing up.

This type of research is important as it helps families of autistic young people to understand their own interactions, it also builds knowledge about these real-life experiences that others can draw on.

Introduction

The diverse ways in which autistic young people understand communication, and communicate within families, and differences between family members’ communication, can result in barriers to family interaction (Gorlin et al. Citation2016). Autistic expression, and experience, of communication and social interaction differs from the dominant, non-autistic social norms and expectations, and is acknowledged to be a key feature of autistic experience (Milton Citation2012; Fletcher-Watson and Happé Citation2019) and central to the diagnosis of autism (APA Citation2013). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child asserts the rights of all children to be heard and to have their views considered and taken seriously (UNICEF Citation1989). As parents take an increased role as advocates for their autistic young people. (Boshoff et al., Citation2016) it is important that we find ways to better understand family communication to ensure the views of autistic young people are listened to and included.

Little is known about the nature of communication in families of autistic children in middle childhood as they meet the challenges of emerging adolescence. Research in communication in families with autistic children centres on early infancy and early childhood (Green et al. Citation2010). Research exploring communication in autistic children in middle childhood and adolescence traditionally seeks to develop normative language and communication (Parsons et al. Citation2017) with a focus on school environments and behavioural intervention (Laugeson et al. Citation2012). There is a paucity of research which explores family communication in the home and family environment, particularly with autistic young people in emerging adolescence. Whilst the social world is acknowledged as presenting challenges to autistic individuals and their families (O’Dell et al. Citation2016), the intimate family setting is indicated as prominent in establishing an enabling or disabling experience, and these personal relationships should be considered in the research agenda (Van der Horst and Hoogsteyns Citation2014). Existing research falls short, therefore of considering how autistic young people’s communicative ability can be identified, and reciprocated, in social interactions with familiar people (Rapley Citation2004; Dindar, Lindblom, and Kärnä Citation2017).

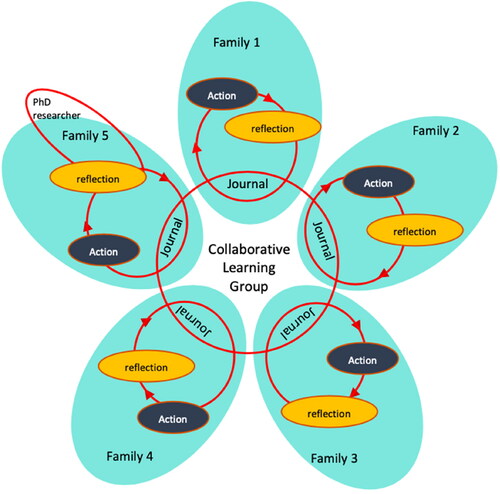

This article reports on a study which engaged mothers from five families as co-researchers to explore communication in their family and centred around their autistic young person. As part of APAR methodology, a research approach that seeks knowledge production through lived experience, mothers came together in Collaborative Learning Groups (CLGs) and shared narratives of communication experience. This provided opportunities for both self and shared reflection as a pathway to improving understandings. Within a social, political and educational narrative of stigma and exclusion relating to autism (O’Dell et al. Citation2016), the APAR methodology enabled an action-reflection cycle through which mothers learned from the authentic communication of their autistic young person within their family, and each other’s narratives, enabling a deeper understanding of their young person’s unique situated communication.

Findings presented in this article identify the central positioning of time and space as key enablers to inclusive communication within families. This builds on the work of Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) who identified how parent-child shared time continues as an important factor in adolescent development. Older children and adolescents continue to rely upon their parents for closeness, connectedness, and support, whilst also developing independence and autonomy (Lam, McHale, and Crouter Citation2012; Larson et al. Citation1996). Zimmerman et al. (Citation2013) emphasises the importance of positive parent-child communication in supporting the transition from childhood to adulthood, however, challenges in communication can impact this dynamic (Steinberg Citation2001; Harper and Cooley Citation2007; Shire et al. Citation2015). Whilst family communication is vital in supporting development and transition from childhood to adulthood (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979; Larson et al. Citation1996; Lam, McHale, and Crouter Citation2012; Zimmerman et al. Citation2013), the altered communication landscape in families of autistic young people can result in pervasive and profound barriers to communication with potential misunderstanding and isolation (Caldwell and Horwood Citation2007; Gorlin et al. Citation2016; Milton Citation2012; Parsi and Elster Citation2012). With this difference in expression and experience of communication and interaction, research clearly identifies the increased challenges autistic young people face, finding increased behavioural challenges, mental ill health and anxiety in this population (Widnall et al. Citation2022; Vickerstaf et al. Citation2007; Lecavalier Citation2006; Cook et al. Citation2021).

As indicated in the Unicef report (UNICEF 1989), all children have the right to inclusion in their community and this community includes home. Krieger et al. (Citation2018) acknowledge the importance of the environment in enabling participation for autistic young people noting the role of families, and particularly mothers, in facilitating social connectedness and advocating for their young person. The challenges to engaging the ‘voice’of those with communication differences has resulted in the exclusion of the views of autistic young people in research and understanding of family communication (Dee-Price et al., Citation2021). Where direct spoken word is relied upon for research engagement these voices may remain silenced. (O’Dell et al., Citation2016) and Woods et al. (Citation2018) advocate for autistic people to be meaningfully involved in research. Therefore, this study engaged young people through their authentic interaction and through the methods that were relevant to their communication within their families. Addressing a paucity of parent-led research in the field, this study explored an insider view of communication and social interaction in families with an autistic young person in late childhood and early adolescence. Specifically, this co-produced study explored opportunities and methods to support inclusion in family communication, an important factor in supporting emerging adolescents.

Research design

This study utilised a particular form of Participatory Action Research (PAR) termed Autoethnographic Participatory Action Research (APAR). Participatory Action Research (PAR) acknowledges that individuals become experts by experience and provides a methodological approach which draws on this lived experience. This methodology provides an iterative approach to knowledge production through an action-reflection cycle of plan-act-observe-reflect (McTaggart Citation1994; Kemmis Citation2006, Citation2009). PAR strives to better understand and address the located challenges specific to a community (Freire Citation1982). Typical research invites participants to pre-determined projects, this study engaged parents as co-researchers who developed the project in an iterative manner. In all families participating in the study, it was the mother who chose to take part as co-researcher. The lead researcher was positioned as a family member and therefore an insider researcher (Anderson Citation2006).

Autoethnography accepts the emotional and connected insider researcher account as intrinsic to research exploration and knowledge production (Ellis Citation2004; Ellis, Adams, and Bochner Citation2011; Bochner and Ellis Citation2006). In the context of this study autoethnographic data was generated through the cyclical action-reflection process. Through a Collaborative Learning Group (CLG) and reflective journals, mothers generated and shared vibrant accounts of communication interaction from within their families (Anderson Citation2006; Adams and Manning Citation2015), including contributions from their autistic young people carried in mothers’ narratives or contributed through visual or note form. Mothers of autistic children are reported to take on multiple roles and challenges beyond that of other mothers (O’Hare et al. Citation2021) (Stoner and Angell, Citation2006). This paper reflects the advocacy role that mothers often assume (Ryan and Runswick-Cole, Citation2008) and centres the authentic verbal and other-than-verbal (including non-verbal, behavioural, and artefact) communication of the autistic young person in their home and family. The autoethnographic reflections and action reflection cycle allow learning from the authentic expression of the autistic young person.

Participants

This study involved 5 families of autistic young people and included the lead researcher and their family. Families were recruited through the network of families in which this researcher was involved. All names have been changed to protect anonymity. All family members were asked to provide consent for participation, where autistic young people could not provide this consent parental consent was provided.

The 6 autistic young people across these families were aged between 9 and 14 representing a period in late childhood and early adolescence during which young people experience rapid change and development. Parents in 2 of the families became separating during the period of the study but all parents agreed to continue with participation in the study via mothers’ contribution.

Family 1

Mum (Maddy), Dad, Will, aged 9 and Rosie, aged 12. Will is nonverbal and Rosie has minimal verbal communication. Both attend a special school.

Family 2

Mum (Josie) and Dad, Josh aged 9 and has a younger sister. Josh attended a mainstream school and has a good level of vocabulary for his age.

Family 3

Mum (Kate), Dad, Dan aged 14. He has an older brother and sister. Dan attends a mainstream school and has a good level of vocabulary for his age.

Family 4

Mum (Jen), Dad and Ollie aged 13 who has an older and a younger brother. Ollie attends a special school and has restricted spoken language.

Family 5

Mum (Anne – researcher in this study), Dad, Charlie aged 12 and his older brother. Charlie attends a special school and has restricted spoken language and uses echolalia.

Methods

Participants from the 5 families were invited to establish a Collaborative Learning Group (CLG) based on the principles of Wenger’s community of practice (Wenger Citation2000). Mothers from each of the families elected to join the Collaborative Learning Group and became co-researchers. Each of the mothers was asked to keep a journal and attend the CLG.

The CLG met on 7 occasions across 10 months. The first meeting (not recorded) allowed parents to ask questions and discuss methods of data generation and discuss the content and methods used for collecting journal entries.

Reflective journals

In the first meeting of the CLG, mothers agreed to give time for communication within their typical family context and then to reflect on this communication time and record their thoughts in their journal. They agreed to include the views of other family members, either directly if possible or indirectly through their reflections. They agreed to encourage contribution from their autistic young person if they wanted to share any forms of interaction through writing, pictures, or photographs. It was agreed by participants that the format of the journal would be particular to each mother and family and flexible in format to allow inclusion of contributions from young people and other family members. In practice the journals included handwritten notebooks, typed pages and one password protected video of the parent shared with the lead researcher. Photographs and notes were provided by some young people. Mothers engaged the fathers, where possible and available, to reflect on communication with them. Father’s interactions were recorded in mother’s reflective journals and discussions.

Collaborative Learning Group meetings

After the initial CLG meeting, six further meetings of the CLG took place and were audio-recorded and transcribed; five of these were monthly, with the final follow-up meeting taking place after a 3-month period to further reflect on the findings from the research. All data were transcribed and stored securely on the password protected university main drive. CLG meetings were held in a private room in a local parent support centre and facilitated by the lead researcher. Meetings lasted between 90 and 120 min. Of the 7 CLG meetings 4 were attended by all group members. A member was missing in 3 of the meetings due to family commitments. The lead researcher provided a summary of the meeting to the mother who missed the meeting and offered opportunity for separate discussion which was taken up on 1 occasion.

To initiate the active research phase parents agreed to give focused time for communication with their autistic young person. Data was generated through autoethnographic methods of storying and narratives through journals and within the CLG discussions. These journals described the emotional and personal struggles from within families and shared the heartfelt experiences of families finding ways to communicate, understand and support one-another. These narratives and artifacts from within families described the rich communication landscape of home-life infused with challenges and difficulties, joy, and humour. The verbal and other-than-verbal contributions from the young people centred in this study were carried in the mothers’ narratives, and in some artefacts from the young people, including notes and drawings. The narratives of the diverse communication expressions and interactions, and the capacity of young people as active communicators, drove the collaborative learning through iterative reflection and action.

Analysis

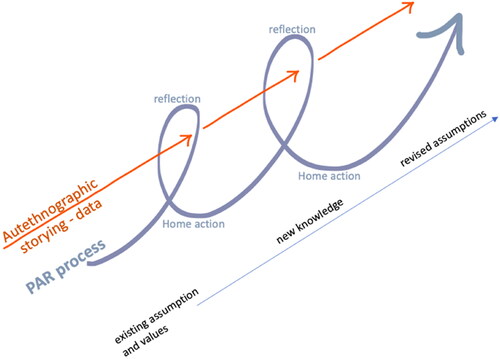

Analysis was initiated through the cyclical action-reflection approach inherent in APAR. Mothers met within the CLGs and discussed their experiences and took these reflections back to their active focus within their family communications. By articulating their own experiences and listening to the experiences of other participants they were increasingly able to act and reflect on their communication practices. The revisiting of key concepts through discussion and reflective practice allowed initial themes to emerge driven by the CLG. Thematic analysis of data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) provided a framework for analysis. Iterative and reiterative reading and coding of the data identified themes. The concepts of giving time and space and the positive impact of this on communication was consistently referred to by mothers in the data. Identification of the positive impact of giving time and space supported increased reflexivity and challenged preconceptions in mothers who referred to the impact of this action as enabling communication. Immersive reading, coding and identification of themes by the lead researcher was shared with the CLG in three later meetings for discussion. Trustworthiness was established through an iterative and reiterative approach to analysis and member checking. This paper focuses on key themes from the data; the importance of giving time and space to invest in communication for these families and the positive and enabling impact of this action. describes the iterative APAR cycle which shaped the analysis through reflection-action.

Ethics

Ethical approval was provided by Northumbria University ethics committee. A full process of informed consent included accessible information sheets for family members detailing the project and their expected commitment. Consent to participate in the study was gathered from young people (where they could provide this), siblings and parents. Where two young people did not show understanding of the process, parents provided consent for their young person to engage in the study. Ethical concerns were central to the development of the study. Direction was taken from the Durham Centre for Social Justice and Community Action (DCSJCA) ethics training and based on the work of Banks (Citation2009). Driver (author one and co-researcher) presented a video on the ethical concerns of working with young people who are non-verbal and use diverse communication to the Participatory Research Network (UKPRN) conference in Cartagena. Feedback supported the methods employed and advocated for iterative reflection on ethical protocol and participant values established in the study. Prior to the first meeting all family members were encouraged to share the values they felt were important in the research by circling words from an extensive list (informed by DCSJCA training). These values were reflected upon as the meetings progressed. The iterative and reflexive approach of PAR supported a critical awareness in all parents. It was heavily informed by the verbal and nonverbal expressions of young people, providing an ethical reflexivity which monitored any impact of the study on the family participants in a self-reflective process. Families were provided with contact numbers for staff in local 3rd sector organisations who could provide support and guidance if any participants experienced distress because of study participation.

Findings

One-to-one time

Throughout the discussions, mothers made significant reference to time as an enabler in communication. Where time was given for focussed one-to-one communication, young people were more able to process communication and express themselves. This process of reflecting on one-to-one time enabled mothers to be more aware of their young person’s expressions and their capacity as communicators.

And I think with a lot of children with autism, they don’t make their needs known …whereas another child might say, ‘you’re not listening to me’ …. they don’t necessarily make their needs known, so you almost have to overcompensate for that; by giving them the more focussed time, to let them have their say. (Kate CLG discussion)

Kate’s son Dan had vocabulary that was typical of a fourteen-year-old boy, yet he had great difficulty accessing his language and expressing himself verbally. Kate and her husband focussed on one-to-one time with Dan, a method they initiated as part of this study.

He doesn’t readily share information through language, and he needs a bit of time and coaxing to articulate what he feels, so unless he is given the one-to-one time, we often don’t get to hear what is on his mind. (Kate reflective journal)

Kate acknowledged it was easy to forget that her son needs extra time to process communication as he had well developed vocabulary. She felt that remembering to build in specific time to focus on communication was important. Kate described spending time sitting together on her bed with her son. She believed this conscious effort to give increased time for communication allowed her son to both access his language and have the time to think of what he wanted to say, enabling Dan to express thoughts that he would not typically share. Kate referred to the way her son was able to talk to her about his approaching school transition in their shared communication time, allowing his views to inform the school review process.

But we actually got quite a lot out of him this time about what he’s feeling about it, it was really lovely…….and I honestly think it’s because we’ve been spending more time, just one-on-one time, just giving him time to speak…. (Kate CLG discussion)

Similarly, for the young people involved in the study who used minimal or nonverbal communication, making time for one-to-one engagement enabled opportunity to communicate and be together, with a focus on playful interaction and shared experience. Maddy spoke of the positive time she had spent in the summer holidays with her two children; Rosie and Will. She acknowledged how very tiring this period was but spoke of the joy she experienced in their shared play and communication engagement, facilitated through giving time for one-to-one interaction.

Because it was summer holidays we’ve had more time with the children and so we were able to have more one-to-one and to reflect a bit more on our communication, which has been lovely….it was really lovely to give the kids the full attention and spend some time, let the other stuff go and say right this is what I’m going to do and give you my full attention and that really paid dividends as well. (Maddy reflective journal)

Maddy’s reflections indicated that the experience of this one-to-one and the attention this gave the children through focussed play and engagement meant that the children were better able to share time and attention at other points.

…you know, we could all share the same space and that felt easier…enjoyable, so I think it was like, giving them more attention, kind of topping up that need, they were then better able to share my time and attention when the time came which is something I’ll absolutely take away from it all I think. (Maddy reflective journal)

Maddy speaks of an increased awareness of the benefits of one-to-one playful interaction which she believed allowed her children to feel ‘topped-up’ with her attention, allowing a sustained connection beyond the direct one-to-one time. She felt this made the children more able to share her attention at later points in time when she couldn’t offer a one-to-one focus.

Space to communicate

As the CLG meetings progressed there was a shift to mothers increasingly using the term space, building, and expanding upon the concept of giving time: Space to accommodate the emotional pressure of communication and to be able to be heard and included. Mothers spoke of the difficulty their young people had when they were pressured to communicate, where anxiety, frustration or emotional complexity inhibited communication. For example, when asked direct questions Charlie would reject the direct questioning by using the phrase ‘I don’t want to ask that question!’ The pressure of direct questioning served to close any opportunity for him to engage. For Dan and Josh who both attended mainstream schools, there were ongoing difficulties in dealing with the complexities of the school environment. Both mothers of Dan and Josh recognised the challenges these environments create for their young person and the impact this had on their communication when they felt pressured to speak.

So, communication is, is a really big thing, so although he’s verbal it’s still a really big thing. Because he’s not able to articulate, he’s not able to express. Or he’s not sure what his response should be, he just shuts down. (Kate CLG discussion)

Josh finds the intensity of school highly demanding and takes time to regulate himself afterwards.

We always leave him alone for as long as we can after school, it’s basically when he comes out and starts jumping on the trampoline, that’s when it’s kind of safe to talk. (Josie CLG discussion)

Reflecting on the pressure to communicate in the school context increased mothers’ awareness of the disabling impact of direct questions or pressure to communicate. This intensity could shut down communication.

In the meetings mothers discussed that in family communication and interaction, they are often busy or there are numerous voices and activities competing. Where this extends to include others, the lack of space to join in can result in the young person becoming excluded from communication interactions. For Charlie, close family members were able to adjust to create space, yet where other people entered the communication environment it became difficult for him to access and join in the communications.

What I have realised more than anything is when it’s just the close family Charlie can access language a lot of the time and we sometimes summarise a more complex conversation. Or we slow to allow him time to join in the chat. As soon as another kid or other family join in, he loses the ability to engage in the conversation, it’s too quick and complex. I try to build space for Charlie to get in but it’s not easy. (Anne reflective journal)

Parents recognised that offering increased space for communication allowed children and young people more opportunity to join in, to contribute their thoughts and express themselves. Through reflective practice, Josie found that by holding back from offering her thoughts and solutions, Josh was more able to process his own opinions and have space to work things out for himself.

I think one major thing I’ve learned is to stop talking … And I think one of the biggest lessons I’ve learned, with Josh is to just shut that off, to just stop it, …I just kind of wait, I pause, I give the space. (Josie CLG discussion)

Kate’s reflections described particular benefit in her increased awareness of space as a catalyst to enable Dan to express himself. She and Dan’s Dad worked together to establish increased space, allowing Dan the opportunity to process language but also to manage his emotions to be able to access and express his own thoughts and feelings.

…I’ve just become aware of the times where we don’t give him enough space to go through that frustration of trying to find the right words to say, …and I’ve become more aware of needing to slow down and just, when he can’t find the right words or just gets angry, or that, just kind of let him have space to, to say that… He often used to say ‘I don’t know, I don’t know’, but now he won’t say that, now he’ll try and come up with an answer, and again I think it’s that he knows we’re going to give him a bit of space rather than say I don’t know what you mean… in busy family life, sometimes kids’ll say something and it’s like ‘what was that?’ and then he just kind of retreats, but now he’s got that bit of space where we’re going to listen, its lovely. (Kate CLG discussion)

…it’s just letting him have that space and I think it’s a lot of what this project is about isn’t it, be more focussed and aware of those, opportunities. (Kate one-to-one CLG discussion)

‘That pattern of knowing’

During the study, mothers and other parents invested in and reflected on their one-to-one engagement with their autistic young person and became aware of patterns that had begun to establish where time and space were given for communication. Where mother and child regularly came together for communication, children began to anticipate these interactions. Mothers spoke of communication both through language and non-verbal interaction. Children anticipated the time and space where they would have a specific opportunity to communicate.

I’m doing the one-to-one time with him, and we just sit on my bed, and he just cuddles in, and we just talk, and so I think he’d got into that pattern of knowing that he’s going to have time to speak. (Kate CLG discussion)

In Kate’s discussion around the bedtime routine they had established, she referred to the ‘pattern of knowing’. This awareness of an anticipated communication time is reflected by four of our five mothers, who speak of bedtime as a particular time in the day where parent and child come together. When parents offered time to be together for one-to-one engagement and interaction, the young people came to anticipate this interaction. Whilst the anticipated communication that Kate speaks of evolved as a result of the one-to-one time established as part of the study process, the reflective process made Josie more aware of the importance of this space and the opportunity it gave her son to express himself and share his thoughts or worries.

…. now, it’s almost like he waits sometimes [until bedtime], and I walk in the room, and he’ll turn round and say, ‘right!’ he dumps on me, but it’s, he knows that’s just like a little quiet space…. (Josie CLG discussion)

Bedtime was acknowledged as a particularly relevant and important point of contact by the mothers of the young people who used verbal communication. Their children in particular seemed more able, indeed keen, to express themselves at this point in the day. This regular time at the end of the day allowed opportunity for their young person to communicate thoughts, concerns or issues that were on their mind.

For Charlie, whose verbal communication was restricted, bedtime was focussed on shared interaction around his books. This was an established and important shared reading time. Whilst it offered opportunity for dialogue it was also a source of narrative and storying, something that he drew upon to inform and structure his communication, these stories became a shared reference for dialogue.

Reading books at bedtime this evening and Charlie asked for the little red train…. He talked me through the book and asked me questions. …we read together and can therefore relate to the narrative and use this to support shared understanding and dialogue. (Anne reflective journal)

For Maddy and her children there is less emphasis on a specific time in the day, yet she actively seeks familiar positive communication interactions. Maddy speaks of the way Rosie asks for familiar routines that she has established with mum to provide predictable space for reassurance, returning to these familiar routines to secure and comfort her.

…I just think there’s so much going on sometimes she just thinks, do you know what, just do what I know, just give me a little bit of just what I know to make me feel safe. So that’s what we do, so you know, it’s just joining her in that, and then she’s kind of like, yeah, I know this! So, when she wants reassurance, she wants for example for me to hide under the covers with her “mummy covers” and for us to pretend to be Peppa [Pig] and Suzy [Sheep] when they are in the tent together. (Maddy CLG discussion)

Mothers also acknowledged the importance of familiar spaces and routines shared by siblings. Jen knows that Ollie’s shared space with his brother is timing out and it will no longer be appropriate to share a bath as her sons will need to seek privacy. This has been a particularly important time where the boys played together, Ollie calling it ‘Bro time’.

…he still has that connection with [younger brother], so we have that issue of well, your body’s changed now Ollie, bath time with [younger brother’s] probably not going to be any more, well that was just devastation, …because what the bath time did with him and [younger brother], was his role play kind of, it was just free flowing and it was just his imagination and we’ll kind of get this truck and this shark and we’ll do this with them, and it was the only time Ollie could do that kind of play free style not copied from a film or a movie, and to take that away from him! (Jen CLG discussion)

Kate also recognised the lost connections that her son experiences.

[sister] used to have quite a mothering relationship with him and they did .bake cakes with him and everything but she’s off with her boyfriend now and with her friends, and she just doesn’t really interact with him. (Kate CLG discussion)

In these excerpts, both mothers lament the loss of the established and familiar space and activity that their young people enjoyed with siblings as they see these spaces closing and the potential of these important communication and connection opportunities being lost.

‘I’m listening’

Through reflection, parents became increasingly aware of the need to establish themselves as available communication partners. Jen started to say ‘I’m listening’ to support Ollie to recognise he was actively being listened to. Her clear and explicit acknowledgement of his communication ensured that he was aware that she was available and listening properly to him. This simple phrase established listening as more tangible communicative action.

I’ve actually started using the words, “I’m listening!” … And things have gone so much better since I’ve done that … And I just keep saying, ‘I’m listening’, because he gets really frustrated if he can’t …like he was when he was, you know when he was non-verbal and he couldn’t speak and I could see the frustration, he’s now getting the frustration when he is speaking to us, but I sometimes think he thinks that we’re not listening …and we don’t understand. And a lot of it, you know, is quite abstract and it is quite hard to understand so I’ve started to put this strategy in place and it’s great, it’s really great. (Jen CLG discussion)

Mothers acknowledged in discussion that they often take for granted that the young person knows they are listening. They reflected that being explicit about their availability and attention ensures that the young person knows they are being actively listened to and are being given the space and opportunity to express themselves.

Empowering

Mothers shared that by creating space for communication, young people had more time to process receptive communication and language, and to initiate and bring their own thoughts or needs to the communication interactions. This enabled young people to be included as more equal partners in communication; to involve their feelings, needs and expressions, in turn empowering them as communication partners.

.…let the other stuff go and say right this is what I’m going to do and give you my full attention …I suppose I go in very much in a playful way, kind of, come on, let’s play but not really making any demands of them, but I’m going to do something I know you’ll enjoy, what are you going to do? You know, and then letting them take the lead. (Maddy reflective video journal)

Mothers discussed the importance of setting aside their own agenda and leaving space for the child’s interest or initiative. By making themselves available they saw that they actively open the space for more inclusive communication. Maddy was explicit in her awareness of letting go of any other agenda or stuff.

With increased opportunity and space to enable young people to engage in more inclusive communication, parents recognised the potential for empowerment of their young people. They discovered that this led to young people initiating more communication and social engagement. Kate talked about a shared interaction where she, Dan and his older sister shared their choices in music. The following day, Dan had spontaneously suggested more shared social time.

What was lovely was the next day …because he never asks me to do things with him, he said ‘could you and I watch a video this afternoon while [sister’s] out? And that was, I think that was a direct result …of the night before we were about an hour and a half of us sitting in a trio doing that, and we were all enjoying it, I was enjoying it, but it led to the next thing which is, and it’s just encouraging this interaction and [him] finding it can be enjoyable…. (Kate CLG)

With this increased time and space to interact and communicate young people were more confident to express themselves and initiate communication. Maddy acknowledged Will’s intentional communication as he actively tried to engage the playful response from his mum.

Will is spontaneously approaching in a more playful way and coming and smiling cheekily, and maybe running off a bit, and turning around and looking and smiling and being cheeky. (Maddy reflective journal)

Maddy’s summary of her interaction with her children expresses her increased awareness of the positive effect of giving time and space to make herself available for communication. She speaks of the way she and her children became more aware of each other and became partners in an evolving dialogue through mutual communicative action.

My conclusion is simply that for better communication, just do it more, do it more often and as we were doing it more often, we were finding other ways that we enjoyed interacting with each other and communicating with each other, some other little games we could play, songs that we could sing or …it was more that we began to recognise stuff in other people. So, I was recognising more what their overtures might be, and they were with me, and then of course they become familiar and much less threatening and so just kind of a virtual circle keeps going, and you extend your repertoire of ways to interact with each other. So, I would just say in conclusion, more is better! The more you do it, the more they want to do it, at least in my experience and the nicer it is! So, it’s just been lovely really, lovely. (Maddy reflective journal)

Maddy articulates her reflections on the shift in power she felt when creating time and space for communication.

That play you have with your child is very bonding …it’s connecting with your child in a way that isn’t so much about power and one person having all of the power and one person having less power, it’s much more equal I would say in terms of balance of power, and by doing that and saying let’s relate to each other in a way that isn’t ‘I’m the grown up and you’re the child’ it is showing respect for your child and it encourages that sort of bonding and that connection…. (Maddy reflective journal)

Discussion

APAR provided an opportunity for mothers to make time and space to communicate within their families and between each other. Turning the gaze inward to in-family communication drew attention to the often-simple politics of located and situated family lives. Through the action-reflection cycle of APAR, mothers recognised the attempts to communicate that were often missed or times when children were not clear that their parent or family member was available and listening. PAR authors emphasise how important it is that the research process opens spaces that facilitate communication (Cook Citation2012; Dentith, Measor, and O’Malley Citation2012). Opening these spaces within the APAR process of reflective journals and CLG discussions, resulted in opening spaces to autistic young people, which enabled their communicative action with other family members. Parents gained an increased awareness of the importance of listening to their autistic young person’s verbal and non-verbal expressions. This reflective practice exposed the importance of the social and physical environment and of familiarity in family communication.

Time and space to actively communicate

In everyday exchanges we typically accept communication to be the back and forth of information, the exchange of words, like objects that we ‘volley back and forth like a tennis ball’ (Lipari Citation2014, 508). Such tacit acceptance of communication as the mere transmission of ideas and information through the back-and-forth linear exchange serves to privilege expressed language and diminish the nuanced complexity and situated emotional experience of communicative behaviour between people (Lipari Citation2014). Where time was given for one-to-one communication, mothers and family members swiftly recognised the benefits. This shared and focussed time allowed parent and child to come together and become more familiar with one another as communication partners. In this communication parents became more aware of their young person’s communication abilities and agency and increasingly recognised their verbal and nonverbal expressions. Mother’s reflections surfaced the significance of giving space for communication. By investing in these spaces, they actively made themselves available and included simple strategies to increase their availability. Saying ‘I’m listening’ allowed Jen to make evident her attention and availability for her son. Maddy actively invested in making her time with Will and Rosie more playful and recognised how this topped up and sustained the children. This established a culture of affirmation and an anticipation that the children could expect their expressions would be acknowledged.

In privileging the metaphor of communication as a message sent between people there has been an emphasis on expressed verbal communication, diminishing the role of listening (Lipari Citation2012). Lipari promotes the concept of communicative interlistening rather than listening. This move responds to our speech-centric culture and seeks to challenge dualist distinctions between speech and listening aiming to establish an understanding of listening as a mode of communicative action (Lipari Citation2012, 519). The conceptualisation of communication as an active interlistening is particularly pertinent in the context of familial communication where the complexity and dynamics of family lives can serve to interrupt and confound communication. The concept of interlistening asks us to consider the active role of both speaking/expressing and listening. This consideration of communication as an active engagement of expressive and receptive communication promotes awareness of self and communication partner in a situated, reciprocal, and relational exchange. The opportunity for reflective practice inherent in APAR made parents turn to notice the unique verbal and non-verbal expression of their autistic young person. This increased awareness of their young person’s expression allowed parents to notice more nuanced expressions and listen and respond to both verbal and non-verbal expressions. This investment in interlistening invested in communicative action and interaction for both parents and autistic young people.

Communication as a spatial event

The findings from this study indicate the need to acknowledge space as intrinsic to communication (Netto Citation2007; Lipari Citation2012; Fox and Alldred Citation2015; Krieger et al. Citation2018). The orientation towards spoken language can serve to marginalise individuals with language and communication processing differences associated with autism (Milton Citation2013; Caldwell Citation2012; Lipari Citation2012) and further, denies their situated experience of the physical environment (Netto Citation2007) which may hold particular significance to autistic communication (Baggs Citation2007). Netto (Citation2007) considers the importance of the physical space in which we communicate as a fixed and visual reference point that can serve to locate our bodies within the communicative event, in contrast to the fluidity of social and human movement. Netto (Citation2007) considers ‘space as referential to communication’ disclosing a ‘material referentiality’ (195) at the heart of our communication practice, this acknowledges the entangled communication of both language, and space, and suggests the possibility of material space as a more tangible counterpart to the elusiveness of fluid communication. This referentiality is potentially of increased relevance to the communication experiences of autistic young people who rely upon stability and familiarity (Rodgers et al. Citation2012; Joyce et al. Citation2017). Autistic people also report of their heightened sensory sensitivity and focus on detail which can be positively or negatively influenced by the physical environment (Bogdashina and Casanova Citation2016).

In their reflections on giving time for communication, parents began to recognise spaces that had become associated with communication events. Bedtime was a particular reference, specifically for those young people who had established and developing spoken language. For these young people, bedtime became a strong point of reference where mothers met and gave time for their young person to be able to express themselves. When time was regularly given over to communication, young people began to anticipate that they would have opportunity to express themselves. For two of our young people, they already regularly used bedtime as a point where their mother helped them to calm down and where they talked about the concerns that were on their mind; this was a regular space where mother and child came together, yet the reflective action of the study process allowed mothers to recognise the importance of this space and further invest in their own availability as communication partners. The familiarity of the communication event which connected time and spatiality, and the familiar communicative phrases and actions, served as enablers for communication establishing patterns of knowing, enabling young people to anticipate communication. Familiarity of interaction established an expectation that they would be listened to, and parent reflection reinforced the importance of familiarity as a communication enabler. The need for sameness is a core feature of autism and often expressed by autistics through restrictive and repetitive behaviours and interests. Findings from this study suggested that repeated and accessible routines in communication such as familiar phrases, activities and shared narratives allowed accessible communication interactions which offered both communicative and soothing connections. The spatial familiarity offered a foundational component in communication, within which the shared narratives, phrases and books offered familiar scaffolding to initiate or revisit communication; communication and comfort were anticipated, as was the expectation that young people would be listened to.

In the communication interactions mothers refer to the physical and familiar spaces that are integral to their communication. Bedtime, but also the physical experience of sitting on the bed together identified the importance of the physical spaces in communicative events providing a catalyst to anticipate communication. This recognition of the importance of anticipated time to engage reflects literature on autism that demonstrates the increased importance of routine and familiarity for these young people. Boulter et al. (Citation2014) and Joyce et al. (Citation2017) highlight the difficulty autistic young people have in dealing with uncertainty, seeking routine and familiarity to counter this. For the young people in this study, familiar and trusted spaces provided a concrete and familiar reference which enabled their active communication.

Mutually Empowering

For mothers engaged in this research study, increasing awareness through reflective practice supported a developing reflexivity. Where mothers invested time and space, they too experienced this communication space. Literature confirms the monitoring and governance of families has potential to influence the parent and family perceptions. Foucault’s (Citation1989, Citation1995) recognition of the omnipresent governance which prescribes hierarchical systems can influence parental perceptions and practices. Biomedically positioned research which informs social narratives, locates communicative (in)competence within individuals, as something that an individual either has or does not have and falls short of recognising that communicative competence can be identified in actual interactions with familiar people (Rapley Citation2004). Van der Horst and Hoogsteyns (Citation2014) assert that ‘the family as a hybrid setting is crucial for the emergence of ability as well as disability’ (832).

Through action-reflection mothers became more aware of their presence in the communication interaction and the positive or negative power they held to control or manage the communication space (see Braidotti Citation2019). Findings suggested a shift in the dynamic of the parent-child interactions, mothers became more aware of themselves as communication partners and their influence on the communication encounter. The process of communication builds meaning and where communication is mutually purposeful there is increased opportunity for co-constructed meaning. Shotter (Citation1996) suggests that meaning originates between us not from within us. Young (Citation1997) advocates a standpoint of moral humility and ‘wonder’ in the face of the other (Young Citation1997 in Milton (Milton, Citation2016)). In referencing Young’s’ work Milton highlights that one cannot see or experience the social world from the perspective of another person and therefore we must wait and learn, through listening and engaging, to be able to gain an understanding of another’s perspective and perceptions.

Maddy very specifically, articulated her awareness of the balance of power within her interactions with her young people, others reflected on the increased trust, confidence and capacity they began to see in their young people, also indicating this rebalancing of power. (Saur and Sidorkin, Citation2018), in researching dialogue in the context of people with learning disabilities, refer to Buber’s suggestion that the situation of power imbalance itself prevents dialogical relation from unfolding. Where communication partners allowed the young person to take a lead in dialogue there was a shift in power, an acceptance of the capability of the young person as communication partner, but also a recognition of the ‘adult’ as available and open to listening. Mothers referred to the fact that their young person might just give up trying when they couldn’t access the family conversations but by giving them space, they were more able to engage. This investment in shifting the power balance is evident in the Intensive Interaction of (Ephraim, Citation1998), Caldwell and Horwood (Citation2007), and Caldwell (Citation2012). Parents found that their increased openness and availability for communication secured their young person and allowed them to get to know one another as equal communication partners.

Early adolescence is a challenging time in the lives of autistic young people, yet they continue to be stigmatized and marginalized by society and receive little support in establishing and sustaining family communication. Such communication is evidenced as being an important factor in adolescent development (Harper and Cooley Citation2007). This paper recognises the need for increased understanding and facilitation of inclusive communication in families of autistic young people as they begin the transition from childhood. It challenges passive advocacy which does not actively seek to engage the voice of autistic young people. This paper also invests in the capacity of families to drive knowledge which directly impacts their lives. The APAR methodology offers further opportunity to build on the process and findings of this research to increase engagement from autistic young people in future family based research. What is evident in the communicative spaces that were explored within these families was not only the capacity of parents to facilitate communication by giving and making space, but also the capacity of the autistic young people as agential communicators. Rather than seeing the parent as the adult teacher, this approach invested in mutual learning. As Freire (Citation1982, Citation1998) advocates, we were learning together and from one another as experts in our own situated knowledge.

Acknowledgements

Dr Catherine Bailey sadly died prior to the publication of this article. Her co-authors would like to pay tribute to her as a valued colleague and supervisor in this research. We would like to thank Cathy’s family for allowing us to publish this article and do so in memory of Cathy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest is reported by each of the authors.

References

- Adams, T. E., and J. Manning. 2015. “Autoethnography and Family Research.” Journal of Family Theory & Review 7 (4): 350–366. doi:10.1111/jftr.12116.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publications.

- Anderson, L. 2006. “Analytic Autoethnography.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35 (4): 373–395. doi:10.1177/0891241605280449.

- Baggs, A. 2007. “In My Language, Directed by Amanda Baggs.” Short Film. Accessed 15 September 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JnylM1hI2jc

- Banks, S. 2009. Ethics in Professional Life: Virtues for Health and Social Care. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Bochner, A. P., and C. S. Ellis. 2006. Comunication as Autoethnography. London: Thousand Oaks.

- Bogdashina, O., and M. Casanova. 2016. Sensory Perceptual Issues in Autism and Asperger Syndrome. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Boshoff, K., D. Gibbs, R. L. Phillips, L. Wiles, and L. Porter. 2016. “Parents’ Voices:’why and How We Advocate’. A Meta-Synthesis of Parents’ Experiences of Advocating for Their Child with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Child: care, Health and Development 42 (6): 784–797. doi:10.1111/cch.12383.

- Boulter, C., M. Freeston, M. South, and J. Rodgers. 2014. “Intolerance of Uncertainty as a Framework for Understanding Anxiety in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44 (6): 1391–1402. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-2001-x.

- Braidotti, R. 2019. “A Theoretical Framework for the Critical Posthumanities.” Theory, Culture & Society 36 (6): 31–61. doi:10.1177/0263276418771486.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. “Contexts of Child Rearing: Problems and Prospects.” American Psychologist 34 (10): 844–850. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.844.

- Caldwell, P. 2012. Delicious Conversations: Reflections on Autism, Intimacy and Communication. London: Pavilion Publishing.

- Caldwell, P., and J. Horwood. 2007. From Isolation to Intimacy: Making Friends without Words. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Cook, J., L. Hull, L. Crane, and W. Mandy. 2021. “Camouflaging in Autism: A Systematic Review.” Clinical Psychology Review 89: 102080. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102080.

- Cook, T. 2012. “Where Participatory Approaches Meet Pragmatism in Funded (Health) Research: The Challenge of Finding Meaningful Spaces.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 13 (1): 18. http://www.qualitative-research.net/.

- Dee-Price, Betty-Jean MLorna Hallahan, Diane Nelson Bryen, and Joanne M Watson. 2021. “Every Voice Counts: exploring Communication Accessible Research Methods.” Disability & Society 36 (2): 240–264. doi:10.1080/09687599.2020.1715924.

- Dentith, A., L. Measor, and M. O’Malley. 2012. “The Research Imagination amid Dilemmas of Engaging Young People in Critical Participatory Work.” In Forum: Qualitative Social Research. Vol. 13, 17. http://www.qualitative-research.net/.

- Dindar, K., A. Lindblom, and E. Kärnä. 2017. “The Construction of Communicative (in)Competence in Autism: A Focus on Methodological Decisions.” Disability & Society 32 (6): 868–891. doi:10.1080/09687599.2017.1329709.

- Ellis, C. 2004. The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Ellis, C., T. Adams, and A. P. Bochner. 2011. “Autoethnography: An Overview.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12 (1): 10. http://www.qualitative-research.net/.

- Ephraim, G. 1998. “Exotic Communication, Conversations and Scripts: Or Tales of the Pained, the Unheard and the Unloved.” In Challenging Behaviour: Principles and Practices, edited by D. Hewitt. London: David Fulton.

- Fletcher-Watson, S., and F. Happé. 2019. Autism: A New Introduction to Psychological Theory and Current Debate. London: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. 1989. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. London: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by A. Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books.

- Fox, N. J., and P. Alldred. 2015. “New Materialist Social Inquiry: Designs, Methods and the Research-Assemblage.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18 (4): 399–414. doi:10.1080/13645579.2014.921458.

- Freire, P. 1982. “Creating Alternative Research Methods. Learning to Do It by Doing It.” In Creating Knowledge: A Monopoly, edited by B. Hall, A. Gillette, and R. Tandon, 29–37. New Delhi: Society for Participatory Research in Asia.

- Freire, P. 1998. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New rev. 20th-anniversary ed. New York: Continuum.

- Gorlin, J. B., C. Peden McAlpine, A. Garwick, and E. Wieling. 2016. “Severe Childhood Autism: The Family Lived Experience.” Journal of Pediatric Nursing 31 (6): 580–597. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2016.09.002.

- Green, J., T. Charman, H. McConachie, C. Aldred, V. Slonims, P. Howlin, A. Le Couteur, et al. 2010. “Parent-Mediated Communication-Focused Treatment in Children with Autism (PACT): A Randomised Controlled Trial.” Lancet (London, England) 375 (9732): 2152–2160. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60587-9.

- Harper, N., and R. Cooley. R. 2007. “Parental Reports of Adolescent and Family Weil-Being following a Wilderness Therapy Intervention: An Exploratory Look at Systemic Change.” Journal of Experiential Education 29 (3): 393–396. doi:10.1177/105382590702900314.

- Joyce, C., E. Honey, S. R. Leekam, S. L. Barrett, and J. Rodgers. 2017. “Anxiety, Intolerance of Uncertainty and Restricted and Repetitive Behaviour: Insights Directly from Young People with ASD.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 47 (12): 3789–3802. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3027-2.

- Kemmis, S. 2006. “Participatory Action Research and the Public Sphere.” Educational Action Research 14 (4): 459–476. doi:10.1080/09650790600975593.

- Kemmis, S. 2009. “Action Research as a Practice-Based Practice.” Educational Action Research 17 (3): 463–474. doi:10.1080/09650790903093284.

- Krieger, B., B. Piškur, C. Schulze, U. Jakobs, A. Beurskens, and A. Moser. 2018. “Supporting and Hindering Environments for Participation of Adolescents Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Scoping Review.” Plos One 13 (8): e0202071. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0202071.

- Lam, C. B., S. M. McHale, and A. C. Crouter. 2012. “Parent–Child Shared Time from Middle Childhood to Late Adolescence: Developmental Course and Adjustment Correlates.” Child Development 83 (6): 2089–2103. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01826.x.

- Larson, R. W., G. Moneta, M. H. Richards, G. Holmbeck, and E. Duckett. 1996. “Changes in Adolescents’ Daily Interactions with Their Families from Ages 10 to 18: Disengagement and Transformation.” Developmental Psychology 32 (4): 744–754. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.744.

- Laugeson, E. A., F. Frankel, A. Gantman, A. R. Dillon, and C. Mogil. 2012. “Evidence-Based Social Skills Training for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders: The UCLA PEERS Program.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 42 (6): 1025–1036. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1339-1.

- Lecavalier, L. 2006. “Behavioral and Emotional Problems in Young People with Pervasive Developmental Disorders: Relative Prevalence, Effects of Subject Characteristics, and Empirical Classification.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 36 (8): 1101–1114. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0147-5.

- Lipari, L. 2012. “Rhetoric’s Other.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 45 (3): 227–245. doi:10.5325/philrhet.45.3.0227.

- Lipari, L. 2014. “On Interlistening and the Idea of Dialogue.” Theory & Psychology 24 (4): 504–523. doi:10.1177/0959354314540765.

- Lipari, L. 2014. Listening, Thinking, Being: Toward an Ethics of Attunement. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press.

- McTaggart, R. 1994. “Participatory Action Research: Issues in Theory and Practice.” Educational Action Research 2 (3): 313–337. doi:10.1080/0965079940020302.

- Milton, Damian E. M. 2016. “Disposable Dispositions: reflections upon the Work of Iris Marion Young in Relation to the Social Oppression of Autistic People.” Disability & Society 31 (10): 1403–1407. doi:10.1080/09687599.2016.1263468.

- Milton, D. E. M. 2012. “On the Ontological Status of Autism: The ‘Double Empathy Problem.” Disability & Society 27 (6): 883–887. doi:10.1080/09687599.2012.710008.

- Milton, D. E. M. 2013. “Autistics Speak but Are They Heard?” Medical Sociology Online 7 (2): 61–68.

- Netto, V. 2007. “Practice, Communication and Space: A Reflection on the Materiality of Social Structures.” Doctoral thesis, University of London.

- O’Dell, L., Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H., Ortega, F. Brownlow, and M. Orsini. 2016. “Critical Autism Studies: Exploring Epistemic Dialogues and Intersections, Challenging Dominant Understandings of Autism.” Disability & Society 31 (2): 166–179.

- O’Hare, A., B. Saggers, T. Mazzucchelli, C. Gill, K. Hass, I. Shochet, J. Orr, A. Wurfl, and S. Carrington. 2021. “’He Is My Job’: Autism, School Connectedness, and Mothers’ Roles.” Disability & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1976110.

- Parsi, K. and N. Elster. 2012. “Growing Up With Autism: Challenges and Opportunities of Parenting Young Adult Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics 2 (3): 207–2011.

- Parsons, L., R. Cordier, N. Munro, A. Joosten, and R. Speyer. 2017. “A Systematic Review of Pragmatic Language Interventions for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Plos ONE 12 (4): e0172242. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172242.

- Rapley, M. 2004. The Social Construction of Intellectual Disability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rodgers, J., M. Glod, B. Connolly, and H. McConachie. 2012. “The Relationship between Anxiety and Repetitive Behaviours in Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 42 (11): 2404–2409. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1531-y.

- Ryan, Sara, and, Katherine Runswick-Cole. 2008. “Repositioning Mothers: Mothers, Disabled Children and Disability Studies.” Disability & Society 23 (3): 199–210. doi: 10.1080/09687590801953937.

- Saur, Ellen, and, Alexander M. Sidorkin. 2018. “Disability, Dialogue, and the Posthuman.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 37 (6): 567–578. doi:10.1007/s11217-018-9616-5.

- Shire, S. Y., K. Goods, W. Shih, C. Distefano, A. Kaiser, C. Wright, P. Mathy, et al. 2015. “Parents’ Adoption of Social Communication Intervention Strategies: Families Including Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Who Are Minimally Verbal.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 45 (6): 1712–1724. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2329-x.

- Shotter, J. 1996. “Before Theory and after Representationalism: Understanding Meaning “from within” a Dialogical Practice.” In Beyond the Symbol Model: Reflections on the Representational Model of Language, edited by J. Stewart, 103–130. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Steinberg, L. 2001. “We Know Some Things: Parent–Adolescent Relationships in Retrospect and Prospect.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 11 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1111/1532-7795.00001.

- Stoner, Julia B, and Maureen E. Angell. 2006. “Parent Perspectives on Role Engagement.” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 21 (3): 177–189. doi:10.1177/10883576060210030601.

- UNICEF UK. 1989. “The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.” Accessed 21 February 2023. https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/UNCRC PRESS200910web.pdf?_ga=2.78590034.795419542.1582474737-1972578648.1582474737

- Van der Horst, H., and M. Hoogsteyns. 2014. “Disability, Family and Technical Aids: A Study of How Disabling/Enabling Experiences Come about in Hybrid Family Relations.” Disability & Society 29 (5): 821–833.

- Vickerstaf, S., S. Heriot, M. Wong, A. Lopes, and D. Dossetor. 2007. “Intellectual Ability, Self-Perceived Social Competence, and Depressive Symptomatology in Children with High-Functioning Autistic Spectrum Disorders.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 37 (9): 1647–1664. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0292-x.

- Wenger, E. 2000. “Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems.” Organization 7 (2): 225–246. doi:10.1177/135050840072002.

- Widnall, E., S. Epstein, C. Polling, S. Velupillai, A. Jewell, R. Dutta, E. Simonoff, et al. 2022. “Autism Spectrum Disorders as a Risk Factor for Adolescent Self-Harm: A Retrospective Cohort Study of 113,286 Young People in the UK.” BMC Medicine 20 (1): 137. doi:10.1186/s12916-022-02329-w.

- Woods, R., D. Milton, L. Arnold, and S. Graby. 2018. “Redefining Critical Autism Studies: A More Inclusive Interpretation.” Disability & Society 33 (6): 974–979. doi:10.1080/09687599.2018.1454380.

- Young, I. M. 1997. Intersecting Voices: Dilemmas of Gender, Political Philosophy, and Policy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Zimmerman, M. A., S. A. Stoddard, A. B. Eisman, C. H. Caldwell, S. M. Aiyer, and A. Miller. 2013. “Adolescent Resilience: Promotive Factors That Inform Prevention.” Child Development Perspectives 7 (4): 215–220. doi:10.1111/cdep.12042.