Abstract

The relationship between race, disability and criminality is complex and poorly understood. Scant information, and lack of action, exists on how to best keep Indigenous people with disability out of the justice system, and support this cohort while in the system. This systematic scoping review collates grey and peer-reviewed literature in Australia, Aotearoa (New Zealand), the United States and Canada, to gain insight into the current practices in place for justice-involved Indigenous people with disability, and list promising principles which may inform future practice. We identified 1,301 sources, and 19 of these met the inclusion criteria. Across these sources, nine key principles emerged: need for Indigenous designed, led and owned approaches; appropriately identify and respond to disability/needs; appropriate court models; appropriate diversionary options; therapeutic, trauma-informed, strengths-based and agency-building responses; facilitate connection to family, community and support networks; break down communication barriers; protect human rights; and provide post-release support.

Points of interest

Internationally, Indigenous people with disability are over-repre.sented in criminal justice systems. The reasons for this are complex and not well understood. Existing evidence suggests that long-lasting effects of colonisation; discrimination on the basis of race and disability; problems identifying and reporting disability; and lack of proper services contribute to this issue.

Often, criminal justice systems do not recognise or support a person’s disability until they reach crisis point.

There is a critical need for culturally-appropriate and disability-appropriate interventions, such as diagnostic tools; training programs for police, correctional officers and other service providers; community court models; and more accessible communication.

There is some evidence that Indigenous-led programs – involving country, culture, art, social connection and holistic healing – help prevent Indigenous people with disability from entering and re-entering justice systems.

More research and evaluation is needed to determine how to better support Indigenous people with disability in contact with the justice system.

Introduction

It is widely reported that those in the justice system – particularly Indigenous people – experience high rates of disability (Blagg and Tulich Citation2018; Erickson and Butters, Citation2005; McCausland and Baldry Citation2017; Shepherd et al. Citation2017). This includes cognitive disability (intellectual disability, acquired brain injury, dementia and foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) – see Baldry et al. Citation2016; Bower et al. Citation2018; McCausland and Baldry Citation2017); hearing loss (Vanderpoll and Howard Citation2011) and psychosocial conditions (Ferrazzi and Krupa Citation2016; Heffernan et al. in Dudgeon et al. Citation2014; McCausland and Baldry Citation2017; Riley, Smith, and Baigent Citation2019).

According to Australia’s recent Report on Government Services, Indigenous people (with or without a disability) were 16 times more likely to be incarcerated than non-Indigenous people in 2020–2021 (ROGS 2022, Table 8A.5). Australia’s current Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability has heard from a range of groups in the community, including the Australian Centre for Disability Law – who estimate that 95 per cent of Indigenous people appearing in court charged with a criminal offence have an intellectual, cognitive or mental health condition (Collard Citation2020). Recent, accurate statistics for Aotearoa (New Zealand), the United States and Canada could not be located. However the literature consistently reports that Indigenous people – including those with disability (such as FASD), mental health and substance abuse issues – are also over-represented in prisons in these three jurisdictions (see Arstein-Kerslake et al. Citation2018:19; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2021, 14; US National Council on Disability 2003; Cesaroni, Grol, and Fredericks Citation2019; Chipman Citation2021).

How and why Indigenous people with disability around the world end up in the justice system is complex and not well understood. Disability – especially cognitive, psychosocial and sensory conditions (such as hearing loss) – can be hidden, and therefore go by undetected and unsupported. Some Indigenous people themselves may not be aware they have a disability (Vanderpoll and Howard Citation2011), or may be reluctant to tell police, prison staff and others of their disability for fear of how they will be treated (Sharma, Pearson, and Bright Citation2018). Disability can be mistaken for wilful defiance, delinquency, drug and alcohol use, low education and/or cultural and linguistic difference (McCausland and Baldry Citation2017; Baldry et al. Citation2015; Baldry et al. Citation2016; Sotiri and Simpson Citation2006; Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2014). A person’s Indigeneity (race) can also be what is noticed, and focused on, and not their disability (McCausland and Baldry Citation2017; Sotiri and Simpson Citation2006; Baldry et al. Citation2015). Sometimes it is indeed known that an Indigenous person has a disability, but this information is ignored, treated with suspicion, or exploited by justice, health, social, educational and other workers (Baldry et al. Citation2015; Sotiri and Simpson Citation2006, 436; Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2014). Hutcheon and Lashewicz note that these kinds of ableist and racist violences which intersect in justice systems pathologise Indigenous people with disability, while also rendering their disabilities invisible (2020).

In addition to the intersectionality of racism and ableism, structural issues exist – such as the absence of appropriate services and supports for Indigenous people with disability, particularly in remote areas. Some Indigenous people may have more than one disability or condition, and may be experiencing, or have experienced, other hardships such as homelessness, unemployment, substance use, separation from family, violence, abuse and (intergenerational) trauma (Australian Human Rights Commission, Citation2008), and have little or no support to deal with such an array of challenges.

All of these factors – solely, or in combination – can result in the criminalisation and incarceration of Indigenous people with disability (Baldry et al. Citation2015; Hutcheon and Lashewicz Citation2020; McSherry et al. Citation2017; Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2008). According to Baldry and colleagues, there is a systemic normalisation of disadvantage, disability and offending, and a view amongst agencies that the best place for Indigenous people with disability and complex needs is in the justice system (2015). Indigenous people with disability not only experience high levels of incarceration; they are frequently victims of crime, too (Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2014; Royal Commission, 2020).

Existing literature illustrates that little is known about ‘what works’ to prevent Indigenous people with disability from entering the justice system; to support this cohort while in the system; and to help this cohort exit and stay out of this system (Australian Human Rights Commission, Citation2008, 38; Baldry et al. Citation2015, Citation2016; Blagg, Tulich, and May Citation2019; Flannigan et al. Citation2018). While a small number of initiatives have been developed in Australia and other Western countries to address the needs of justice-involved Indigenous people with disability, few have been subject to the rigorous research and evaluation needed to determine their effectiveness and impact.

This systematic scoping review has been undertaken to provide an insight into some of the current practices (initiatives, services, interventions, programs, policies etc) in place in Australia, the United States, Canada and Aotearoa (New Zealand) for justice-involved Indigenous people with disability. The aim is to identify and discuss the key promising principles or characteristics of current practices, in order to inform the development of future practices (initiatives, services, interventions, programs, policies etc) for this cohort.

Methods

Systematic scoping review examines and describes the extent, variety and characteristics of literature addressing a particular topic or within a specific field (Tricco et al. Citation2018). While standard systematic review methods enable reviewers to assess the level of evidence for specific practices, the aim of systematic scoping review is to provide an overview of the range of practices in place (Munn et al. Citation2018). Systematic scoping reviews are thus a suitable method for reviews of emerging or promising practice, and for reviews of heterogeneous studies (Peters et al. Citation2015; Tricco et al. Citation2018).

The design of our systematic scoping review is based on the established principles described in the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews Checklist (Tricco et al. Citation2018) and the Joanna Briggs Institute Guidance (Peters et al. Citation2015). We adopted a broad search strategy, and included peer-reviewed, grey and other literature (such as published reports and consultation findings), in order to produce a wide range of results.

Systematic scoping review is a research approach which has emerged from positivist traditions and privileges academic knowledge. We recognise that this methodology may marginalise Indigenous voices and knowledges, as well as voices and knowledges of people living with disability. To address this, we drew from the research approach developed by Lowe and colleagues (2019), and did the following:

Formed a diverse, highly-skilled research team with lived experience. The authors of this review are an Australian First Nations disability advocate, an Australian First Nations research leader, a non-Indigenous researcher with a disability, and three non-Indigenous researchers with experience working with Australian First Nations people.

Regularly engaged with key Indigenous disability advocates and stakeholders, who provided advice on the development of research questions and aims.

Used our earlier systematic review on Australian First Nations peoples’ beliefs, practices and experiences of disability, to inform the design and analysis of this review (Puszka et al. Citation2022).

Developed broadly-defined inclusion criteria, which increased the likelihood that Indigenous-designed and -led studies, as well as studies by those with lived experience with disability, would be included.

Conducted a critical appraisal of the involvement of Indigenous peoples, knowledges and methodologies in the included studies.

The Human Research Ethics Committee of the Australian National University advised that ethical clearance for this project was not required as it did not involve the collection of primary data.

Inclusion criteria

Population

Indigenous people, of all ages, of Australia, Aotearoa (New Zealand), the United States and Canada living with one or more disability (including mental health/psychosocial conditions); and who have, or have had, contact with the justice system.

‘Indigenous’ refers to the First Peoples of these countries.

The word ‘disability’ is used in this review, but we acknowledge its shortcomings. It is often reported that, in Indigenous societies, there is no word, concept or understanding of ‘disability’ (Gilroy et al. Citation2013:44; Ineese-Nash Citation2020; Avery Citation2018; King, Brough, and Knox Citation2014:745; Borsay Citation2004; Meekosha Citation2006, Citation2011; Levers Citation2006). As discussed in our earlier systematic review (Puszka et al. Citation2022), Indigenous peoples globally often do not view a missing or differently functioning body part, sense or capacity as a ‘problem’ requiring ‘fixing’ (Avery Citation2018; Bevan-Brown Citation2013; Walsh Citation2020). Instead of an Indigenous person with ‘disability’ having to be ‘made normal’, the family and community often ensure that the person is accepted, included and able to participate in social and cultural life (Avery Citation2018; Walsh Citation2020). Indeed, the notion of ‘disability’ is often perceived by Indigenous, Black and other marginalised groups to be a harmful, political label imposed upon them by colonisers which can carry feelings of deficiency, inferiority, stigma and shame and, thus, in fact create ‘disability’ (Schalk, 2022; Ineese-Nash Citation2020; Imada Citation2017; Hutcheon and Lashewicz Citation2020, Walsh Citation2020). While recognising the issues with the term ‘disability’, we have had to adopt it in this review because of a) the lack of an equivalent term in Indigenous languages in Australia and other countries (Avery Citation2018) and b) Standard Australian English lacks terms that encapsulates Indigenous constructs of human and social functioning.

‘In contact with’ or ‘justice-involved’ includes not just those currently incarcerated (i.e. in adult prisons, or juvenile detention facilities), but those who have been incarcerated at some point; and also those who may not have been incarcerated but have encountered police and courts etc.

Context

This scoping review focuses on recent literature from the Western settler-colonial states of Australia, Aotearoa (New Zealand), the United States and Canada. These four countries have been deemed comparable because they were all initially colonised by the British, and all received the common law from England. As such, the legal and justice systems are similar in these countries (although there are some nuances) (Gleeson Citation2002; Nielsen and Robyn Citation2003). Additionally, and importantly, the Indigenous peoples of these four settler-states have been significantly impacted by British colonisation. While there is diversity in Indigenous histories, cultures and lived experiences, Indigenous peoples in these four settler-states are likely to be marginalised by, and have challenging experiences with, the legal, criminal justice, disability and other systems and services which have been predominantly designed by and for settler-colonial populations.

Concept

This review scopes current international practices (initiatives, services, interventions, programs, policies etc) in place to support Indigenous people with disability in contact with, or at risk of contact with, the justice system. The review presents key principles, or characteristics, emerging from the included literature, which appear promising for future practice.

Study design

We included sources that met the following criteria:

Conducted in Australia, Aotearoa (New Zealand), the United States and Canada;

Published from the year 2000 onwards;

Published in peer-reviewed journals, as grey literature, or in other categories (such as published reports and consultation findings);

Used primary data collection methods (e.g. qualitative, quantitative or mixed);

Incorporated the perspectives of Indigenous people with disability, and their families and communities.

Specifically focused on Indigenous people living with disability who are in contact with (or have had contact with) the justice system.

Search and selection strategy

The following national and international databases were searched for peer-reviewed and grey literature: INFORMIT (Indigenous Collection, AGIS-ATSIS Collection); Web of Science; Scopus; PubMed; Analysis and Policy Observatory (APO); Indigenous Justice Clearinghouse. Additional literature was identified from professional knowledge of the field, and through reviewing the reference lists of included studies.

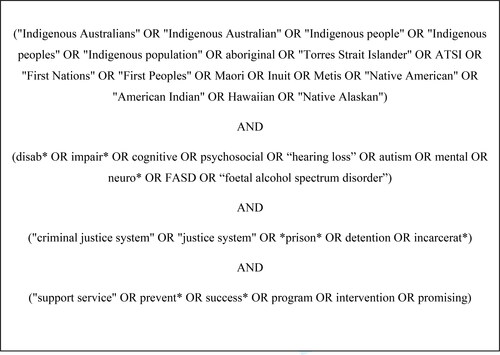

In collaboration with subject librarians, we developed the following Boolean search terms to find relevant literature in the abovementioned databases ().

Some databases (particularly grey literature databases) did not have sophisticated search functions and did not recognise Boolean operators. In these instances, we simplified or reduced the terms and conjunctions.

Data extraction and study selection methods

Literature searches were conducted in March and April 2021. Search results were exported to Covidence© systematic review software. After removing duplicates, initial title and abstract screening was independently conducted by the two lead reviewers (CW and SP). CW screened all titles/abstracts, and SP checked 10% of these titles/abstracts for consistency. The two screeners reached consensus over the sample, and these decisions informed further screening by CW. Full text screening was also performed by CW, in consultation with SP. Both screeners reached a consensus over all full text inclusion decisions.

Charting of data

We undertook a thematic analysis of the 19 included sources. This involved extracting from each source the key themes, or principles, associated with supporting justice-involved Indigenous people with disability. We compared and contrasted these themes/principles, noting similarities, overlaps and which ones received frequent mention. We then synthesised this data to develop nine overarching principles (explored in the Discussion section below). The initial structure of the overarching principles was developed by CW, and then adjusted in dialogue with co-authors. Our synthesis and analysis was also informed by our earlier systematic review of conceptualisations and experiences of disability among First Nations peoples of Australia (Puszka et al. Citation2022).

Appraisal of Indigenous peoples’ involvement in included studies

An appraisal was conducted on each study included in this review, to determine the extent to which Indigenous peoples’ perspectives were part of the research process.

Drawing on the Consolidated Criteria for Strengthening Reporting of Health Research Involving Indigenous Peoples (the CONSIDER Statement) (Huria et al. Citation2019), as well as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quality Appraisal Tool (developed by Harfield et al. Citation2020, 5), and following consultation with Australian First Nations colleagues and advisors, we developed our own appraisal criteria which assessed Indigenous peoples’ involvement in setting research agendas; the representation of Indigenous people and perspectives in research teams and governance structures; and the incorporation of Indigenous ways of knowing, being, seeing and doing within methodologies. For the full framework, see Table S1: Indigenous peoples' involvement in research appraisal criteria in online supplementary material.

Results

Search results

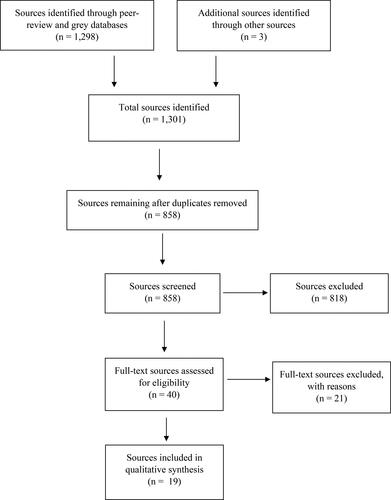

Our search strategy identified a total of 1,301 sources (peer-reviewed n = 1,247; grey n = 51; other n = 3). After removing duplicates, 858 sources remained and the abstracts of these were screened. After screening of abstracts, 40 sources made it to full text review stage (peer-reviewed n = 25; grey n = 12; other n = 3).

After full text review and further screening, 19 publications met the inclusion criteria (peer-reviewed n = 11; grey n = 5; other n = 3) and were synthesised and discussed in this scoping review.

depicts the stages of our search and selection strategy.

provides an overview of the 19 sources included in this review, and the key principles which emerged in each of these. These principles are each explored in detail in the Discussion below.

Table 1. Summary of included sources and key principles emerging.

Appraisal results

Generally, the involvement of Indigenous peoples and organisations in included studies was not well reported. According to our appraisal criteria, the included studies performed relatively well in involving Indigenous people in research teams/governance (14 sources out of 19 reported a large extent of involvement). However, Indigenous people were not as well involved in setting research priorities/agendas (10 out of 19 reported involvement to a large extent), and Indigenous ways of knowing, being, seeing, doing were poorly reflected in methodological approaches (10 out of 19 reported a high degree of incorporation).

Discussion

Key principles emerging from synthesis of the references

Indigenous designed, led and owned

The sources included in this review regularly discussed the ineffectiveness of mainstream, Western approaches (even those mainstream responses which have been ‘made culturally appropriate’); and the need for initiatives and approaches which are Indigenous designed, led and owned, and underpinned by Indigenous ways of knowing, being, seeing and doing (McCausland and Dowse Citation2020; Blagg and Tulich Citation2018; Miller Citation2017; Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2008, Citation2014; Heffernan et al. in Dudgeon et al. 2014). To many Indigenous people worldwide, the criminal justice system is a daunting construct containing foreign colonial assumptions, language and procedures. Isolation, punishment, correction and retribution dominate modern Western approaches to crime and these can be harmful and traumatising to Indigenous people, especially those with disability (Hamilton et al. Citation2020; Goren Citation2001; Ferrazzi and Krupa Citation2016, 163).

Blagg and Tulich (Citation2018), as well as Miller (Citation2017), argue that decolonising the justice system is necessary, which means that justice interventions be Indigenous community owned, and not merely community based. Sources contend that mainstream services are ill-equipped to provide culturally-safe care for justice-involved Indigenous people, and Indigenous and Aboriginal community controlled organisations and services are best placed to support this cohort (Blagg and Tulich Citation2018; McCausland and Dowse Citation2020; Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2008; MacGillivray and Baldry Citation2013; Heffernan et al. in Dudgeon et al. 2014). In 2015, researchers from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) undertook an in-depth, Indigenous-informed, mixed-methods study (‘The IAMHDCD Project’) exploring the needs of First Nations Australians with disability in the criminal justice system, and provided a clear agenda for action – with self-determination (Indigenous-led knowledge, solutions and community-based services) being at the forefront of this agenda (Baldry et al. Citation2015; McCausland and Dowse Citation2020).

However, there is a lack of published evidence on Indigenous-specific justice approaches (services, programs, policies etc), particularly approaches which have been designed, implemented and evaluated in partnership with Indigenous families and communities (Rasmussen, Donoghue, and Sheehan Citation2018; Heffernan et al. in Dudgeon et al. 2014). Further research and evaluation into Indigenous-owned, designed and led justice approaches – especially for those Indigenous people with disability – is recommended.

Appropriately identify and respond to disability

For many Indigenous people, diagnosis of their disability comes with assessment on entry to prison (Baldry et al. Citation2015; Sharma, Pearson, and Bright Citation2018). Recognising a person’s disability and needs as early as possible in their life – in a culturally-safe manner – could increase their chance of receiving appropriate rehabilitative services and supports, and decrease their chance of becoming entangled in the justice system when their needs reach crisis point (McCausland and Dowse Citation2020; Vanderpoll and Howard Citation2011; Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2008).

Several studies argued for the need for culturally-safe assessment and diagnostic tools, inside and outside of the justice system (Blagg and Tulich Citation2018; Vanderpoll and Howard Citation2011; Flannigan et al. Citation2018; Sharma, Pearson, and Bright Citation2018; Heffernan et al. in Dudgeon et al. 2014;). In 2008, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) recommended that disability and mental health screening occur for Indigenous children and youth in the child protection system. This is because Indigenous Australian children in out-of-home-care (OOHC) are over-represented in the youth justice system, and this is a key driver of adult incarceration (Andersen et al. Citation2019).

As discussed earlier in this paper, Indigenous people globally can be reluctant to engage with the colonial, medical construct of ‘disability’, and sources included this review confirm this (Baldry et al. Citation2015; Ferrazzi and Krupa Citation2016; McCausland and Dowse Citation2020; Flannigan et al. Citation2018; Sotiri and Simpson Citation2006). As such, it is imperative that disability definitions and measurements (such as screening and diagnostic tools) be informed by Indigenous people’s conceptualisations and experiences, such as taking into account the social, cultural, historical and other determinants of ill-health and disability, such as colonisation, dispossession, marginalisation, racism and trauma.(Lau et al. Citation2012; McCausland and Dowse Citation2020).

This review finds that there is a dearth of Indigenous-designed and culturally-meaningful assessment tools available internationally. The Indigenous Risk Impact Screen (IRIS) is one culturally-appropriate, widely-used tool for assessing substance use and psychosocial issues in Indigenous adults across Australia, which has been validated for use in the context of Indigenous adults in custody (Ober et al. Citation2013).

Also crucial to identifying and responding to disability is the provision of culturally-informed, disability-informed education and training for service providers. Almost all sources mentioned that those working in the justice system (e.g. police, lawyers, magistrates, correctional officers) and other stakeholders (e.g. teachers/educators) often do not recognise disability in Indigenous (and even non-Indigenous) people, and are unaware of how to address such a situation in an appropriate, effective manner.

Education and training for individuals interacting with Indigenous peoples in the justice system might help to address some of the negative attitudes and assumptions about people with disability (‘ableism’). For instance, that people with disability are unreliable, not credible, not capable of giving evidence, making legal decisions or participating in legal proceedings (Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2014; Royal Commission, 2020). Education and training must include Indigenous peoples’ past and present experiences which may also help address racism and stereotypes from justice system workers, and improve relations and trust between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people (Miller Citation2017; Trofimovs and Dowse Citation2014; Baldry et al. Citation2016). While no specific education/training programs were discussed in included sources, most made a general call for mandatory, ongoing cultural, disability and gender training for those working in, and out of, the justice system (McCausland and Dowse Citation2020; Royal Commission, 2020; Sharma, Pearson, and Bright Citation2018; Heffernan et al. in Dudgeon et al. 2014; Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2008; Shepherd et al. Citation2017; Vanderpoll and Howard Citation2011; Flannigan et al. Citation2018; Miller Citation2017).

Disability- and culturally-appropriate court models

Court innovations are currently in place in Australia and other countries, such as Aboriginal/Community courts (Koori Court, Youth Koori Court), circle sentencing, Aboriginal Sentencing Courts (ASCs) and Neighbourhood Justice Centres (NJCs). They are based on the non-adversarial, less punitive and more rehabilitative concepts of ‘therapeutic jurisprudence’ (TJ) and ‘restorative justice’ (Goren Citation2001; Miller Citation2017). The aim of these more culturally-appropriate options is to involve Indigenous people and practices, and to empower the victim as well as the offender. In these community courts, everyone has a shared responsibility in working out the nature and impact of the offence and how to repair the damage.

Therapeutic-jurisprudence-based courts (e.g. mental health and drug courts) have received criticism for being paternalistic, Eurocentric forums which fail to provide true self-determination to Indigenous people (Miller Citation2017; Ferrazzi and Krupa Citation2016; Pyne Citation2012; Blagg, Tulich, and May Citation2019; Blagg, Tulich, and Bush Citation2015; Blagg and Tulich Citation2018). How effective these courts are for Indigenous people with disability as a specific group is not well researched, however. Miller also discusses Rangatahi Courts operating in Aotearoa, which incorporate Maori law and culture (2017:149). Similar to Australia, and due to a lack of sources uncovered for Aoetearoa, it is unclear as to whether these community courts are appropriate for Maori with disability.

In Canada, Drug Treatment Courts (DTCs) in Vancouver have been found to reduce recidivism, but it also has not yet been established whether they are equally effective for all subgroups of offenders, such as those with psychosocial and other conditions (Somers, Rezansoff, and Moniruzzaman Citation2014). In North America, a leading response to the overrepresentation of people with psychosocial conditions in the criminal justice system has been mental health courts (Ferrazzi and Krupa Citation2016). However, criminal court mental health initiatives do not exist for the Inuit people in the Canadian Arctic (Nunavut), and, again, the evidence is unclear as to whether such initiatives can be successfully adapted to Nunavut communities (Ferrazzi and Krupa Citation2016).

Blagg, Tulich and May question the effectiveness of ‘problem-solving’ courts and conferences for those with disability, especially FASD (2019). They recommend a mobile needs-focused court (raised also in Blagg, Tulich, and Bush Citation2015), which is a hybrid model that draws on the strengths of the Koori Court model and the NJC model. This model would see Elders in the courtroom – which would help to provide a recognisable, safe, comforting cultural symbol for those with FASD, who may not respond well to unfamiliar people and processes (Blagg and Tulich Citation2018:7). This model would also employ a comprehensive screening process upon entry into the court, and would refer them into support programs, preferably on Country. Blagg and Tulich envisage that ‘this hybrid approach would allow greater Indigenous involvement in community-based alternatives for those found unfit to stand trial and, through culturally secure and community owned alternatives, lead to better outcomes for Indigenous young people with FASD’ (2018, 7). Similarly, Miller advocates for a hybrid NJC-ASC model both inside and outside of the court, which she – like Blagg and Tulich – contends is a more decolonising approach (2017).

Disability- and culturally-appropriate diversionary options

A strong theme emerging in our synthesis is the need for diversion (into mental health, drug and alcohol, housing and other community-based, rehabilitative programs) for Indigenous offenders with disability, rather than a custodial sentence – especially for low-level crime (Baldry et al. Citation2015; Flannigan et al. Citation2018; Heffernan et al. in Dudgeon et al. 2014; Pyne Citation2012).

However, there seem to be few positive, community-based options specifically designed for Indigenous people with disability and complex needs (Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2014; Flannigan et al. Citation2018; McCausland and Dowse Citation2020). There are even less diversionary options available for Indigenous people with disability in remote areas, which means that incarceration becomes the default option (Baldry et al. Citation2015:11). There is a particular lack of diversionary options for Indigenous women with disability (McCausland and Baldry Citation2017; Royal Commission, 2020; Somers, Rezansoff, and Moniruzzaman Citation2014; McCausland and Dowse Citation2020), as well as Indigenous youth with disability (Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2008).

The diversionary initiatives that do exist do not seem to be both culturally-appropriate and disability-appropriate. According to McCausland and Dowse, writing for the Australian context, ‘diversionary programmes tend to be embedded in a concept of individual responsibility and choice around offending that can be counterproductive for people with mental and cognitive disability, as it presumes they can simply choose to stop offending. Failure to meet the eligibility criteria of a diversion programme or to complete it for whatever reason is considered as failure of the individual rather than a result of systemic factors, ill-conceived programme design or punitive administration’ (2017, 296). McCausland and Baldry found that some individuals, especially those with disability, are receiving longer sentences in order to access diversionary programs. As such, these authors conclude that ‘diversionary mechanisms, however well intentioned, are serving to entrench rather than divert’ (McCausland and Baldry Citation2017, 303).

Blagg and Tulich express doubt about the appropriateness of mainstream diversionary mechanisms, and recommend place-based, Indigenous-owned solutions, such as on-Country programs for Indigenous offenders and those at risk of offending, especially those with FASD (Blagg and Tulich Citation2018). They mention an already successful initiative called the Yiriman Project, run by Elders from around Fitzroy Crossing in Western Australia. This program takes young Aboriginal people at risk of offending out onto traditional Country, where they acquire bush skills in a culturally secure environment. A three-year review of the Yiriman Project found that not only is being on Country beneficial for young peoples’ health and wellbeing, but minimises their involvement in the justice system (Palmer Citation2013). Rasmussen and colleagues have similarly found that Aboriginal prisoners with high levels of engagement in cultural activities are less likely to violently reoffend (2018). In Canada, Ferrazzi and Krupa also advocate for programs that provide justice-involved Inuit people with psychosocial conditions opportunities to be on their traditional lands (2016).

More appropriate diversionary options for Indigenous people with disability necessitates changes to policy and legislation. Section 32 and Section 33 of the Mental Health (Forensics Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW) can be applied by a magistrate to people who are seriously mentally ill at the time of their court appearance, otherwise Section 32 is used as the main diversionary mechanism. However, MacGillivray and Baldry have found that very few people who meet Sections 32 and 33 are granted it by the court, and this is especially the case for Indigenous people (2013, 24). Some of the reasons for this are ill-equipped legal services, and lack of awareness of the individual’s disability (MacGillivray and Baldry Citation2013). Sources in this review argue for the need to consistently and fairly apply mental health legislation to divert people away from prison and into appropriate treatment (McSherry et al. Citation2017; Pyne Citation2012).

Therapeutic, trauma-informed, strengths-based and agency-building

Included sources advocated for programs and initiatives which are needs-informed, trauma-informed, therapeutic, nurturing, and foster agency, empowerment, confidence, sense of self-worth and purpose – as opposed to punishing harder and longer (Flannigan et al. Citation2018; Hamilton et al. Citation2020; McCausland and Dowse Citation2020).

Hamilton and colleagues yarned with 38 youth (27 of whom were Aboriginal) at Banksia Hill Detention Centre in Western Australia, to find out what personal, social and community capital they require inside and outside of prison. Some of these young people had been diagnosed with FASD or neurodevelopmental conditions. Although the participants had lives marred by trauma, disability and hardship, they spoke of many things that made them happy and hopeful: strong connections to country, family and community, and future goals such as education, employment and skill development. Hamilton et al. call this ‘recovery capital,’ and argue that services ought to focus on these (through the use of appropriate assessment tools) if they want to help these young people on their pathway out of the justice system (Hamilton et al. Citation2020).

Flannigan and colleagues obtained perspectives from Alexis FASD Justice Program (AFJP) workers, which operates in the Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation in Canada (2018). The researchers found the following features of the AFJP supported offenders with FASD and complex needs: screening and identification of areas of disability; comprehensive assessment to understand individual strengths and difficulties; special attention to basic needs; simplifying and assisting with navigating the justice process; mentorship; family and community engagement; and collaborative, compassionate and flexible approaches (Flannigan et al. Citation2018).

Rasmussen and colleagues investigated the degree to which engagement in art programs shield Aboriginal prisoners from psychological distress that leads to self-harm and suicide (2018). In the program, the prisoners engaged in Aboriginal art and socialised with visiting Elders from the local community; and it was found that participation in these was indeed associated with reduced incidence of suicide/self-harm (Rasmussen, Donoghue, and Sheehan Citation2018). Shepherd et al. conclude that Aboriginal prisoners with high levels of engagement in cultural activities are less likely to violently reoffend (in Rasmussen, Donoghue, and Sheehan Citation2018, 142). Blagg and Tulich, quoting Perry (2009), also write about emergent research in neurodevelopmental science, which suggests that interventions such as art, nature, discovery and storytelling are helpful for those with disabilities, particularly FASD (2018).

In Melbourne, Australia, the Gathering Place Health Service (GPHS) healing program, is an intensive rehabilitation and spiritual healing initiative for Indigenous men and women, most of whom have psychosocial conditions, substance issues and/or chronic health conditions (Lau et al. Citation2012). The program has proved very effective for one repeat offender (a middle-aged First Nations man with mental health and substance abuse issues). The program consists of many supported components, such as art and culture classes, food/nutrition classes, drug and alcohol counselling, literacy and numeracy classes, sport and physical activity program, and meditation. The most crucial aspect of the GPHS program is the weekly healing circle run by Elders, which helps participants reconnect with their Indigenous culture, heritage and spirituality. The program has mentors and health workers who make sure participants’ disability, health/medical, housing, transport, social and other needs are met. Unfortunately, the GPHS healing program had not (at that point) been formally evaluated (Lau et al. Citation2012).

In a women’s prison in South Australia, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which uses mindfulness and acceptance strategies, was found to be an acceptable intervention for female Indigenous Australian prisoners with medical, psychosocial and substance abuse issues (Riley, Smith, and Baigent Citation2019). Anxiety and mindfulness measures improved, participants gave overwhelmingly positive feedback about the program, and there were no formal dropouts (Riley, Smith, and Baigent Citation2019).

Connection to family, community, mentors and support personnel

Included sources mentioned the importance of approaches which are not just individual-focused, but promote connection to family, friends, mentors, community and Elders (Flannigan et al. Citation2018; Ferrazzi and Krupa Citation2016; Blagg and Tulich Citation2018).

Incarcerated youth in Hamilton et al.’s study saw their families as a source of strength, comfort and wellbeing; leading the researchers to argue that strong relationships and networks with family and others is an important part of recovery and healing (2020). Lau and colleagues found that children of incarcerated parents are at higher risk of poor health, and an increased risk of offending later in life (particularly in Indigenous families), which is why Melbourne’s GPHS pilot healing program adopts a whole-of-family approach (2012).

The current Australian Royal Commission has heard that the justice system ought to use community-based services and supports for people with disability, and specifically mentioned intermediary programs (2020). An intermediary is someone who can find out the best way to communicate with another person; find out what communication support the person needs; tell people in the justice system how to communicate with that person (Royal Commission 2020). Kippin and colleagues also discuss the usefulness of intermediaries (termed ‘court-appointed communication assistants’) for justice-involved youth with FASD and language disorder in Western Australia (2018). Miller mentions ‘Koori Justice Workers’ at Melbourne’s NJC, who support Indigenous clients by creating treatment plans, providing spiritual and emotional support, referring them to appropriate services and ensuring Indigenous knowledge and perspectives are honoured (Miller Citation2017).

In Aoetearoa, Thom and Burnside found peer support (particularly from ex-offenders who can bring their own lived experience) to be a successful feature of Te Whare Whakapiki Wairua/Alcohol and Other Drug Court (AODT Court) for Maori offenders with mental health and addiction issues (2018).

Sotiri and Simpson caution that some Indigenous people in the justice system may not feel comfortable having an Indigenous support person who is someone they know (2006), and thus should be provided with a choice of support person, where possible.

Break down communication barriers

Police stations, courts and prisons are highly verbal, unfamiliar environments for Indigenous people who sometimes do not have English as their first language, and even more so for those Indigenous people with conditions which can affect communication and comprehension, such as FASD and hearing loss (McSherry et al. Citation2017; Sotiri and Simpson Citation2006; Vanderpoll and Howard Citation2011; Kippin et al. Citation2018). This can lead to people with disability being wrongfully accused, less likely to be granted bail and more likely to breach bail because they have not understood the instructions and conditions (Australian Human Rights Commission, Citation2014).

According to Vanderpoll & Howard, over 90% of Indigenous inmates in the Northern Territory have some degree of hearing loss (often due to untreated childhood middle-ear infections, as well as tinnitus), leading to difficulty hearing and understanding in police stations, courtrooms and prisons (2011). These authors recommend hearing loss awareness training for justice officials, and routine hearing tests and provision of hearing aids/amplification for inmates (2011).

Sources recommend speech therapists, interpreters, and local cultural and language advisors be provided at all stage of the justice system to assist Indigenous people with hearing loss and other communication difficulties (Kippin et al. Citation2018; Blagg and Tulich Citation2018).

Protect human rights

The current Australian Royal Commission has heard that Australians with disability in the justice system, especially Indigenous youth, are not having their needs met, and are even experiencing mistreatment and abuse from fellow inmates and correctional officers (2020).

Sharma and colleagues also detailed harrowing stories of treatment of Indigenous people with disability in the justice system, and concluded that Australia is restricting and violating the rights of prisoners with disabilities (2018). Pyne also argued several years earlier that laws in the Northern Territory are racially discriminatory against Indigenous people, and are in conflict with international human rights standards (2012).

Specific suggestions made by included sources on how to better protect the rights of justice-involved Indigenous people with disability are:

Provide targeted, culturally-appropriate and disability-appropriate legal assistance (Royal Commission 2020);

Address ‘unfit to plead’ laws. Australian laws allow for people with disabilities to be detained indefinitely (for years, even), when they are considered unable to understand or to respond to the criminal charges laid against them (referred to as ‘unfit to plead’) (McCausland and Baldry Citation2017; Baldry et al. Citation2015; Blagg and Tulich Citation2018, Royal Commission, 2020; McSherry et al. Citation2017; Pyne Citation2012). This means that ‘an individual can…spend a longer time in detention than if he or she plead guilty and was sentenced to imprisonment for the offence’ (Blagg and Tulich Citation2018, 5–6; McCausland and Baldry Citation2017; Pyne Citation2012). Addressing unfitness to plead means creating a criminal justice system which does not create separate justice procedures for persons with disabilities (McSherry et al. Citation2017, 58). According to McSherry et al, the Disability Justice Support Program is a cost-effective, human-rights-affirming model which appears to reduce the need for unfitness to plead determinations by assisting accused persons to participate in proceedings and exercise their legal capacity (2017, 9).

Abolish solitary confinement. Restrictive practices such as segregation and isolation are used in prisons, including on people with disability (Royal Commission, 2020; Sharma, Pearson, and Bright Citation2018). Some prisoners with mental and cognitive conditions are being locked in solitary confinement for weeks or months, sometimes for almost 24 hours a day (Sharma, Pearson, and Bright Citation2018).

Provide post-release support

Several sources highlighted the necessity of post-release support for Indigenous people with disability, and also the challenges of providing support of this nature.

Indigenous offenders with cognitive disability are almost three times more likely to reoffend than those without cognitive disability (Shepherd et al. Citation2017). For Indigenous people with cognitive and psychosocial conditions, there are very few alternatives to prison; a lack of appropriate programs and support services in prison or post-release; and the outside world is often difficult for them to navigate – meaning return to prison is very likely (Baldry et al. Citation2015; Sharma, Pearson, and Bright Citation2018; Tait et al. Citation2017). Release from prison for Indigenous Australians with disability, especially psychosocial and cognitive, is associated with a range of poor health outcomes such as homelessness, substance abuse, drug overdose and suicide (Heffernan et al. in Dudgeon et al. 2014).

Hearing loss is a particular barrier to release and rehabilitation (Vanderpoll and Howard Citation2011). According to Vanderpoll and Howard, Indigenous inmates with hearing loss may actually prefer the high security section of the prison because it places less demands on their listening skills. Some inmates with hearing loss will choose to do their whole time in prison rather than apply for parole, because parole is typically complex, challenging and requires good listening skills (Vanderpoll and Howard Citation2011).

Primary health care (Kinner, Young, and Carroll Citation2015), and other resources and services, can help Indigenous people with disability (especially women) transition to life in the community (Kilroy Citation2005). These resources and services include financial support, employment and training opportunities, drug and alcohol assistance, grief and mental health counselling, and safe and affordable housing (Kilroy Citation2005). Sullivan et al. (Citation2019), as well as Pyne (Citation2012), discuss the effectiveness of ‘throughcare’ initiatives, such as the Connections Programme (CP), which provide support to individuals during imprisonment through to post-release. The Australian Royal Commission has heard that the ‘throughcare’ program run by North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency (NAAJA) is an example of good practice (2020). However, it is unclear as to just how effective ‘throughcare’ initiatives are specifically for Indigenous people with disability.

Baldry and colleagues mention the need for supported accommodation and educational support for Indigenous people with disability – early in life if possible, and also after release from prison (2012). These authors mention the NSW Community Justice Program as a good example of a housing program which supports people with an intellectual disability who have been in the criminal justice system (McEntyre, Baldry, and McCausland Citation2015).

Lau and colleagues argue that, if Indigenous prisoners are to have successful community reintegration after their release from prison, then community programs which encompass healing, family and appropriate, meaningful education (such as Melbourne’s GPHS healing programme) are paramount (2012).

Limitations

The majority of sources included in this scoping review are from the Australian context. There were few sources which met our inclusion criteria for the countries of Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the United States. This indicates a lack of research (particularly involving primary data collection) specifically focused on justice-involved Indigenous people with disability in these states, highlighting a critical need for more international research to be conducted.

The literature we identified was heavily focused on Indigenous people in the justice system with cognitive and mental/psychosocial disabilities. Many sources conflated mental health conditions – as well as trauma, substance abuse, addiction – with disability, making it difficult to determine whether the paper should be included. We identified few sources solely focused on disability – especially sensory and physical conditions – which again suggests a need for more research.

The method of scoping systematic review itself has some limitations. As identified in the Methods section of this paper, systematic reviews – while useful – rarely reflect Indigenous knowledges and methodologies, which is why we undertook several steps to ensure voices of Indigenous people, and those with disability, were included. Further, scoping reviews provide an overview of existing research/practice, and do not closely examine or evaluate the included studies. It is thus recommended that more research and evaluation – using qualitative methods (e.g. interviews, focus groups, yarning) which can deeply and critically explore interventions (initiatives, policies, programs, services etc) from the perspectives of justice-involved Indigenous people with disability – be urgently conducted in Australia, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Canada and the United States.

Conclusion

The purpose of this scoping review was to understand current practices (initiatives, services, programs, policies etc) in place for justice-involved Indigenous people with disability in Australia, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Canada and the United States and develop some general principles to be considered when developing future initiatives for this cohort.

Due to the scarcity of sources specifically meeting our inclusion criteria for all four countries, we had limited literature from which to draw conclusions. However, it is clear from the available literature that – while there may be initiatives in place for general offenders, for offenders with disability, and for Indigenous offenders – there is a noticeable lack of initiatives in place specifically for Indigenous people with disability in the justice system as a distinct group. Further, while there may be some mainstream services, initiatives and programs which can support justice-involved Indigenous people with disability, there are very few approaches for this cohort which are Indigenous-owned and framed by Indigenous ways of knowing, being, seeing and doing. There is a pressing need for robust research and evaluation into ‘what works’ for Indigenous people with disability who have, or have had, contact with the justice systems in Australia, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Canada and the United States.

The strong theme emerging in the available literature is the inadequacy of justice systems in responding to the needs and rights of Indigenous people with disability, and the need for significant policy, legislative and system reforms. As we highlighted earlier in this review, identifying and appropriately responding to disability is complicated by the concept of ‘disability’ itself – a term which many Indigenous peoples see to be colonial, limiting and damaging. Therefore, practices that negatively frame justice-involved Indigenous people with disability as ‘problems’ to be ‘rectified’ can continue to perpetuate colonial violence.

From the limited peer-reviewed and grey literature unearthed in this scoping review, nine key principles emerged which show that supporting Indigenous people with disability in the justice system is possible, and essential:

Indigenous-designed, -led and -owned initiatives;

Identify and respond to disability and needs in culturally-safe ways;

Disability- and culturally-appropriate court models;

Disability- and culturally-appropriate diversionary options;

Therapeutic, trauma-informed, strengths-based and agency-building responses;

Facilitate connection to family, community, mentors and support personnel;

Break down communication barriers;

Better protect human rights;

Provide post-release support.

We argue for reforms to, and investment in, services, initiatives, policies and programs which reflect these nine principles. Importantly, initiatives should respect and incorporate Indigenous conceptualisations and values regarding embodiment, human functioning and social inclusion. The cultural model of disability and inclusion developed by Australian First Nations disability scholar, Dr Scott Avery – which steers away from the Western medical, and social, models of disability – provides one example of this (2018). Ultimately, to better support Indigenous people with disability at all stages of the justice system, shifting the focus to treatment, care, connection, healing and rehabilitation into the community – rather than criminalisation, isolation, deprivation, punishment and rectification – is crucial.

Geolocation

Australia, the United States, Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand)

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.4 KB)Acknowledgements

Dr Scott Avery and Ms Sam Faulkner provided invaluable advice at the commencement of the project on the research questions and overall approach. They also provided practical advice and assistance with navigating the review process. Our colleagues Dr Diane Smith, Dr Yonatan Dinku, Ms Minda Murray and Professor Lorana Bartels provided much appreciated advice and feedback on the methodology, structure and content. Staff from the ANU Library generously assisted us with selecting databases and developing search terms. Laura Robson and Dr Talia Avrahamzon from the Australian Government Department of Social Services provided guidance in response to our queries at every stage of this project, especially on the project design, methodology and in identifying relevant literature. The information and views contained in this research are not a statement of Australian Government policy, or any jurisdictional policy, and do not necessarily, or at all, reflect the views held by the Australian Government or jurisdictional government departments.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersen, M., R. Borschmann, E. Buisson, P. Cullen, L. Gubhaju, N. Pollard-Wharton, B. Porykali, and K. Thompson. 2019. The Health and Wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Young Peoples: Position Paper. Crows Nest: Australian Association for Adolescent Health.

- Arstein-Kerslake, A., Y. Maker, M. Ireland, and R. Mawad. 2018. Research needs in access to justice for people with disability in Australia and New Zealand. University of Melbourne. Accessed 7 December, 2022 https://socialequity.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/word_doc/0007/2927842/Disability-Access-to-Justice-Scoping-Paper.docx

- Australian Government, Productivity Commission 2022., Report on Government Services (ROGS) 2022. Released 28 January 2022. Canberra, Australia. Accessed 16 January 2023. https://www.pc.gov.au/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2022

- Avery, S. 2018. Culture is Inclusion: A Narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with a Disability. Sydney, First Peoples Disability Network.

- Baldry, E., L. Dowse, R. McCausland, and M. Clarence. 2012. Lifecourse Institutional Costs of Homelessness for Vulnerable Groups. Sydney: National Homelessness Research Agenda.

- Baldry, E., R. McCausland, L. Dowse, and E. McEntyre. 2015. A Predictable and Preventable Path: Aboriginal People with Mental and Cognitive Disabilities in the Criminal Justice System. University of New South Wales, Sydney.

- Baldry, E., R. McCausland, L. Dowse, E. McEntyre, and P. MacGillivray. 2016. “It’s Just a Big Vicious Cycle That Swallows Them Up’: Indigenous People with Mental and Cognitive Disabilities in the Criminal Justice System.” Indigenous Law Bulletin 8 (22): 10–16.

- Bevan-Brown, J. 2013. “Including People with Disabilities: An Indigenous Perspective.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 17 (6): 571–583. doi:10.1080/13603116.2012.694483.

- Blagg, H., and T. Tulich. 2018. “Diversionary Pathways for Aboriginal Youth with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder.” Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology No.557,.

- Blagg, H., T. Tulich, and Z. Bush. 2015. “Placing Country at the Centre: Decolonising Justice for Indigenous Young People with Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD).” Australian Indigenous Law Review 19 (2): 4–16.

- Blagg, H., T. Tulich, and S. May. 2019. “Aboriginal Youth with Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Enmeshment in the Australian Justice System: Can an Intercultural Form of Restorative Justice Make a Difference?” Contemporary Justice Review 22 (2): 105–121. doi:10.1080/10282580.2019.1612246.

- Borsay, A. 2004. Disability and Social Policy in Britain since 1750: A History of Exclusion. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bower, Carol, Rochelle E. Watkins, Raewyn C. Mutch, Rhonda Marriott, Jacinta Freeman, Natalie R. Kippin, Bernadette Safe, et al. 2018. “Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Youth Justice: A Prevalence Study among Young People Sentenced to Detention in Western Australia.” BMJ Open 8 (2): e019605. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019605.

- Cesaroni, C., C. Grol, and K. Fredericks. 2019. “Overrepresentation of Indigenous Youth in Canada’s Criminal Justice System: Perspectives of Indigenous Young People.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 52 (1): 111–128. doi:10.1177/0004865818778746.

- Chipman, J. 2021. Disabled inmate was forced to sleep on cell floor for 3 weeks, lawsuit alleges. CBC News, 21 November 2021. Accessed 7 December, 2022 https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/disabilities-prison-lawsuit-1.6065673

- Collard, S. 2020. Royal Commission hears high rates of First Nations prisoners with disability. NITV News. Accessed 7 December, 2022. https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/royal-commission-hears-high-rates-of-first-nations-prisoners-with-disability/1icq2y8pt

- Ferrazzi, P., and T. Krupa. 2016. “Symptoms of Something All around us”: Mental Health, Inuit Culture, and Criminal Justice in Arctic Communities in Nunavut, Canada.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 165: 159–167. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.033.

- Flannigan, K., J. Pei, C. Rasmussen, S. Potts, and T. O’Riordan. 2018. “A Unique Response to Offenders with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: Perceptions of the Alexis FASD Justice Program.” Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 60 (1): 1–33. doi:10.3138/cjccj.2016-0021.r2.

- Gleeson, M. 2002. Global influences on the Australian judiciary. Speech to the Australian Bar Association Conference, 8 July 2002, Paris, France. Accessed 13 December 2022. https://www.hcourt.gov.au/assets/publications/speeches/former-justices/gleesoncj/cj_global.htm

- Gilroy, J., M. Donelly, S. Colmar, and T. Parmenter. 2013. “Conceptual Framework for Policy and Research Development with Indigenous People with Disabilities.” Australian Aboriginal Studies (2): 42–58.

- Goren, S. 2001. “Healing the Victim, the Young Offender, and the Community via Restorative Justice: An International Perspective.” Issues in Mental Health Nursing 22 (2): 137–149. doi:10.1080/01612840121244.

- Hamilton, S. L., S. Maslen, D. Best, J. Freeman, M. O’Donnell, T. Reibel, R. C. Mutch, and R. Watkins. 2020. “Putting ‘Justice’ in Recovery Capital: Yarning about Hopes and Futures with Young People in Detention.” International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 9 (2): 20–36. doi:10.5204/ijcjsd.v9i2.1256.

- Harfield, Stephen, Odette Pearson, Kim Morey, Elaine Kite, Karla Canuto, Karen Glover, Judith Streak Gomersall, et al. 2020. “Assessing the Quality of Health Research from an Indigenous Perspective: The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quality Appraisal Tool.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 20 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1186/s12874-020-00959-3.

- Heffernan, et al. 2014. “Mental Disorder and Cognitive Disability in the Criminal Justice System.” in Dudgeon, P., Milroy, H., Walker, R. 2014. Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2nd Edition. Telethon Kids Institute, Kulunga Aboriginal Research Development Unit, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australia.

- Erickson, Patricia G, andJennifer E Butters. 2005. “How Does the Canadian Juvenile Justice System Respond to Detained Youth with Substance Use Associated Problems? Gaps, Challenges, and Emerging Issues.” Substance Use & Misuse 40 (7): 953–973. 10.1081/ja-200058855.16021924

- Australian Human Rights Commission. 2008. Preventing Crime and Promoting Rights for Indigenous Young People with Cognitive Disabilities and Mental Health Issues, Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission.

- Australian Human Rights Commission. 2014. Equal before the Law: Towards Disability Justice Strategies. Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission.

- Huria, T., S. C. Palmer, S. Pitama, L. Beckert, C. Lacey, S. Ewen, and L. Tuhiwai Smith. 2019. “Consolidated Criteria for Strengthening Reporting of Health Research Involving Indigenous Peoples: The CONSIDER Statement.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 19 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1186/s12874-019-0815-8.

- Hutcheon, E. J., and B. Lashewicz. 2020. “Tracing and Troubling Continuities between Ableism and Colonialism in Canada.” Disability & Society 35 (5): 695–714. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.1647145.

- Imada, A. L. 2017. “A Decolonial Disability Studies?” Disability Studies Quarterly 37 (3) doi:10.18061/dsq.v37i3.5984.

- Ineese-Nash, N. 2020. “Disability as a Colonial Construct: The Missing Discourse of Culture in Conceptualizations of Disabled Indigenous Children.” Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 9 (3): 28–51. doi:10.15353/cjds.v9i3.645.

- Kilroy, D. 2005. “The Prison Merry Go Round: No Way off.” Indigenous Law Bulletin 6 (13): 25–27.

- King, J. A., M. Brough, and M. Knox. 2014. “Negotiating Disability and Colonisation: The Lived Experience of Indigenous Australians with a Disability.” Disability & Society 29 (5): 738–750. doi:10.1080/09687599.2013.864257.

- Kinner, S. A., J. T. Young, and M. Carroll. 2015. “The Pivotal Role of Primary Care in Meeting the Health Needs of People Recently Released from Prison.” Australasian Psychiatry : bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists 23 (6): 650–653. doi:10.1177/1039856215613008.

- Kippin, N. R., S. Leitão, R. Watkins, A. Finlay-Jones, C. Condon, R. Marriott, R. C. Mutch, and C. Bower. 2018. “Language Diversity, Language Disorder, and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder among Youth Sentenced to Detention in Western Australia.” International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 61: 40–49. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.09.004.

- Lau, P., C. Marion, R. Blow, and Z. Thomson. 2012. “Healing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians at Risk with the Justice System: A Programme with Wider Implications.” Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health : CBMH 22 (5): 297–302. doi:10.1002/cbm.1847.

- Levers, L. 2006. “Samples of Indigenous Healing: The Path of Good Medicine.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 53 (4): 479–488. doi:10.1080/10349120601008720.

- MacGillivray, P., and E. Baldry. 2013. “Indigenous Australians, Mental and Cognitive Impairment and the Criminal Justice System: A Complex Web.” Indigenous Law Bulletin 8 (9): 22–26.

- McCausland, R., and E. Baldry. 2017. “I Feel like I Failed Him by Ringing the Police’: Criminalising Disability in Australia.” Punishment & Society 19 (3): 290–309. doi:10.1177/1462474517696126.

- McCausland, R., and L. Dowse. 2020. “The Need for a Community-Led, Holistic Service Response to Aboriginal Young People with Cognitive Disability in Remote Areas: A Case Study.” Children Australia 45 (4): 326–334. doi:10.1017/cha.2020.49.

- McEntyre, E., E. Baldry, and R. McCausland. 2015. ‘Here’s how we can stop putting Aboriginal people with disabilities in prison.’ The Conversation, November 6 2015. Accessed 20 March, 2022. https://theconversation.com/heres-how-we-can-stop-putting-aboriginal-people-with-disabilities-in-prison-49293

- McSherry, B. E. A. P. R., E. Baldry, A. Arstein-Kerslake, P. Gooding, R. McCausland, and K. Arabena. 2017. Unfitness to Plead and Indefinite Detention of Persons with Cognitive Disabilities. University of Melbourne, Australia.

- Meekosha, H. 2006. “What the Hell Are You? An Intercategorical Analysis of Race, Ethnicity, Gender and Disability in the Australian Body Politic.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 8 (2-3): 161–176. doi:10.1080/15017410600831309.

- Meekosha, H. 2011. “Decolonising Disability: Thinking and Acting Globally.” Disability & Society 26 (6): 667–682. doi:10.1080/09687599.2011.602860.

- Miller, A. 2017. “Neighbourhood Justice Centres and Indigenous Empowerment.” Australian Indigenous Law Review 20: 123–153.

- Munn, Z., M. Peters, C. Stern, C. Tufanaru, A. McArthur, and E. Aromataris. 2018. “Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 18 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

- Nielsen, M. O., and L. Robyn. 2003. “Colonialism and Criminal Justice for Indigenous Peoples in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States of America.” Indigenous Nations Studies Journal 4 (1): 29–45 University of Kansas. https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/5791?show=full.

- Ober, C., K. Dingle, A. Clavarino, J. M. Najman, R. Alati, and E. B. Heffernan. 2013. “Validating a Screening Tool for Mental Health and Substance Use Risk in an Indigenous Prison Population.” Drug and Alcohol Review 32 (6): 611–617. doi:10.1111/dar.12063.

- Palmer, D. 2013. We Know They Healthy Cos They on Country with Old People": Demonstrating the Value of the Yiriman Project, 2010-2013. Fitzroy Crossing: Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture Centre.

- Peters, M., C. Godfrey, H. Khalil, P. McInerney, D. Parker, and C. Baldini Soares. 2015. “Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews.” International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13 (3): 141–146. doi:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

- Puszka, S., C. Walsh, F. Markham, J. Barney, M. Yap, and T. Dreise. 2022. “Towards the decolonisation of disability: A systematic review of disability conceptualisations, practices and experiences of First Nations people of Australia.” Social Science and Medicine. 305 (115047): 1–11.

- Pyne, A. 2012. “Ten Proposals to Reduce Indigenous over-Representation in Northern Territory Prisons.” Australian Indigenous Law Review 16 (2): 2–17.

- Rasmussen, M. K., D. A. Donoghue, and N. W. Sheehan. 2018. “Suicide/Self-Harm-Risk Reducing Effects of an Aboriginal Art Program for Aboriginal Prisoners.” Advances in Mental Health 16 (2): 141–151. doi:10.1080/18387357.2017.1413950.

- Riley, B. J., D. Smith, and M. F. Baigent. 2019. “Mindfulness and Acceptance–Based Group Therapy: An Uncontrolled Pragmatic Pre–Post Pilot Study in a Heterogeneous Population of Female Prisoners.” International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 63 (15-16): 2572–2585. doi:10.1177/0306624X19858487.

- Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability (the Royal Commission) 2020. Overview of Responses to the Criminal Justice System Issues Paper, December 2020. Accessed 19 January, 2022. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-12/Overview%20of%20responses%20to%20the%20Criminal%20Justice%20System%20Issues%20paper%20-%20Easy%20read.pdf

- Sharma, K., E. Pearson, and G. Bright. 2018. I Needed Help, instead I Was Punished": Abuse and Neglect of Prisoners with Disabilities in Australia. Sydney: Human Rights Watch.

- Shepherd, S. M., J. R. Ogloff, D. Shea, J. E. Pfeifer, and Y. Paradies. 2017. “Aboriginal Prisoners and Cognitive Impairment: The Impact of Dual Disadvantage on Social and Emotional Wellbeing.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR 61 (4): 385–397. doi:10.1111/jir.12357.

- Shepherd, S., R. H. Delgado, J. Sherwood, and Y. Paradies. 2018. “The Impact of Indigenous Cultural Identity and Cultural Engagement on Violent Offending.” BMC Public Health 18 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4603-2.

- Somers, J. M., S. N. Rezansoff, and A. Moniruzzaman. 2014. “Comparative Analysis of Recidivism Outcomes following Drug Treatment Court in Vancouver, Canada.” International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 58 (6): 655–671. doi:10.1177/0306624X13479770.

- Sotiri, M., and J. Simpson. 2006. “Indigenous People and Cognitive Disability: An Introduction to Issues in Police Stations.” Current Issues in Criminal Justice 17 (3): 431–443. doi:10.1080/10345329.2006.12036369.

- Sullivan, E., S. Ward, R. Zeki, S. Wayland, J. Sherwood, A. Wang, F. Worner, S. Kendall, J. Brown, and S. Chang. 2019. “Recidivism, Health and Social Functioning following Release to the Community of Nsw Prisoners with Problematic Drug Use: Study Protocol of the Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study on the Evaluation of the Connections Program.” BMJ Open 9 (7): e030546. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030546.

- Tait, C. L., M. Mela, G. Boothman, and M. A. Stoops. 2017. “The Lived Experience of Paroled Offenders with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Comorbid Psychiatric Disorder.” Transcultural Psychiatry 54 (1): 107–124. doi:10.1177/1363461516689216.

- Thom, K., and D. Burnside. 2018. “Sharing Power in Criminal Justice: The Potential of co‐Production for Offenders Experiencing Mental Health and Addictions in New Zealand.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 27 (4): 1258–1265. doi:10.1111/inm.12462.

- Trofimovs, J., and L. Dowse. 2014. “Mental Health at the Intersections: The Impact of Complex Needs on Police Contact and Custody for Indigenous Australian Men.” International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 37 (4): 390–398. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2014.02.010.

- Tricco, Andrea C., Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly K. O’Brien, Heather Colquhoun, Danielle Levac, David Moher, et al. 2018. “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation.” Annals of Internal Medicine 169 (7): 467–473. doi:10.7326/M18-0850.

- United States (U.S.) National Council on Disability (NCD) 2003., Addressing the Needs of Youth in the Juvenile Justice council System: The Current Status of Evidence-Based Research. Accessed 13 December 2022 https://www.ncd.gov/publications/2003/May12003#CurrentLaws

- United States (U.S.) Department of Health and Human Services 2021. Improving Outcomes for American Indian/Alaska Native People Returning to the Community from Incarceration: A Resource Guide for Service Providers. Accessed 7 December, 2022 https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/87b6927ebbd6583df77f31ef4648cbac/improving-aian-reentry-toolkit.pdf

- Vanderpoll, T., and D. Howard. 2011. Investigation into Hearing Impairment among Indigenous Prisoners within the Northern Territory Correctional Services. Phoenix Consulting, Darwin.

- Walsh, C. L. 2020. Falling on deaf ears? Listening to Indigenous voices regarding middle ear infections (‘otitis media’) and hearing loss. PhD dissertation. Australian National University, Canberra, Australia.

- World Health Organisation (WHO) 2002. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health: The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva, WHO.