Abstract

Taking a Global South perspective, we investigate the influence of informality and socio-cultural norms on the mobility and participation of people with mobility impairments in public activities. Sit-down and go-along interviews, and GPS tracking/plotting were conducted to gather data from 14 participants living in urban neighbourhoods of Tegalrejo, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Thematic analysis and qualitative Geographic Information System (GIS) were used to analyse data. Findings show that mobility barriers and enablers based on the everyday experience of participants are made up of inter-related physical and socio-cultural dimensions. Urban informality generates barriers to mobility, but participants could tactically use aspects of such informality to facilitate their movement. Tegalrejo’s kampung collectivism generates opportunities for mobility and community participation. However, participants are often excluded in the guise of pemakluman. These findings add to existing literature on disability, place, and mobility in urban contexts by providing insights about the influence of neighbourhood conditions in Tegalrejo.

Point Of Interest

This research examines barriers to mobility and community participation of people with mobility impairments in Tegalrejo, an urban neighbourhood in Indonesia.

A more collectivist urban village (kampung) way of living in Tegalrejo generates opportunities for mobility and community participation of people with mobility impairments.

However, some distinctive socio-cultural norms, such as pemakluman (being explicitly ‘excused’ from participating in communal activities), maintain the exclusion of people with mobility impairments.

Urban informality generates barriers to mobility, but some of features of informality can be used tactically by people with mobility impairments to enable their mobility and movement.

Findings from this article can challenge and enrich knowledge gained from research primarily focused on high-income countries’ experiences.

Introduction

The exclusion of people with disabilities is a pressing issue in Indonesia. In 2010, it was estimated that around 4.3% of population in Indonesia – or about 10 million people - lived with disabilities (Cameron & Suarez, Citation2017). People with disabilities in Indonesia tend to have lower income because many cannot access labour markets due to physical, social, and institutional discriminations (Cameron & Suarez, Citation2017; Hastuti et al. Citation2020; Yeo & Moore, Citation2003). The National Labour Force Survey (Survei Angkatan Kerja Nasional – SAKERNAS) of Indonesia 2016 indicated that the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) for people with mild and severe disabilities was only 56.7% and 20.3%, respectively, significantly lower than the rate of people without disabilities (70.4%) (Halimatussadiah et al. Citation2018). Studies conducted in regional cities like Malang (Thohari, Citation2014), Solo (Irwanto et al. Citation2010), Yogyakarta (Rahayu et al. Citation2015; Wicaksono et al. Citation2019), Gorontalo (Hadi et al. Citation2020) and Banda Aceh (Aini et al. Citation2019) show that public places such as governmental buildings and public transportation are inaccessible to support the mobility of people with disabilities. People with disabilities are also often excluded from participation in political elections (Kramer et al. Citation2022). Social security coverage for people with disabilities remains inadequate (Huripah, Citation2020). These varied forms of exclusion are underpinned by stigma and negative perceptions of people with disabilities in Indonesia as incapable and powerless human beings (Kramer et al. Citation2022; Thohari, Citation2014).

Much of the effort to tackle the exclusion and promote the rights of people with disabilities in Indonesia has focused on the city scale. In the last decades, various iterations of inclusive city programmes and initiatives have been promoted by local and national governments of Indonesia (Maftuhin, Citation2017). The implementation of the Inclusive City Programme has been promoted and supported by international donors and Civil Social Organisation such as Handicap International, UNESCO, ILO, UNPRPD, and Asian Development Bank (Asian Development Bank, Citation2011; Safitri, Citation2016; UNESCO Inclusive Policy Lab, Citation2018) through various development partnership schemes. Fourteen cities participated in the program in 2017, and Yogyakarta City – the focus of this paper – was one of the first to adopt the scheme, with four pilot projects trialled in the sub-districts of Tegalrejo, Wirobrajan, Kotagede, and Gondokusuman.

In this context of growing urban policy attention to promote disability inclusion in Indonesia, little is known about the barriers to inclusion and participation within the local settings of the country’s diverse urban neighbourhood environments. Research surrounding disability and accessibility in urban contexts in Indonesia tends to focus on physical environmental barriers in pedestrian streets, sidewalks, stations, tourist destinations, commercial buildings, and public facilities and transportation services (see for example Ernawati & Sugiarti, Citation2005; Hadi et al. Citation2020; Hayati & Faqih, Citation2013; Hidayati et al. Citation2021; Muhaemin, Citation2019; Qur’ana & Purnomo, Citation2020; Simanjuntak, Citation2019; Tamba, Citation2018; Tanuwidjaja et al. Citation2018; Wahyuni et al. Citation2016; Wibawa & Widiastuti, Citation2019; Wicaksono et al. Citation2019). These studies show that people with diverse disabilities still encounter physical barriers in public places, such as the absence of elevators or ramps, inaccessible public toilets, poorly designed sidewalks, or the absence of tactile guiding blocks (Hadi et al. Citation2020; Hayati & Faqih, Citation2013; Wahyuni et al. Citation2016; Wibawa & Widiastuti, Citation2019; Wicaksono et al. Citation2019). Meanwhile, evidence from high income countries, such as Norway (Lid & Solvang, Citation2016), the Netherlands (van Hoven & Meijering, Citation2019), and New Zealand (Smith et al. Citation2021) suggests that both social and physical barriers in urban neighbourhoods contribute to the social exclusion of people with disabilities.

In general, social and physical barriers and enablers to participation vary significantly among neighbourhoods with different socio-geographic and economic characteristics. In this paper, we consider such differences in terms of everyday participation at urban neighbourhood scale, raising issues such as informality, and cultural norms of collectivism/individualism. We ask and address the question of how the social and physical environment of an urban neighbourhood in Indonesia influence the participation of people with disabilities in everyday activities such as shopping, going to work, socialising, and engaging in the local community (e.g. attending community meetings, religious gatherings, neighbourhood working-bees events (gotong-royong). Using data from fieldwork conducted in the sub-district of Tegalrejo, in the City of Yogyakarta in 2022, we take an approach to understand the link between places and the experience of mobility barriers/enablers for people with disabilities in urban contexts (Imrie, Citation2000; Imrie & Thomas, Citation2008; Lid & Solvang, Citation2016; Wiesel & van Holstein, Citation2020).

Analysing insights from a local neighbourhood like Tegalrejo provides critical insights to disability inclusion/exclusion, and further adds to our understanding of the complex relationships between disability and place within various socio-economic and cultural settings (Watson & Vehmas, Citation2020; Wiesel & van Holstein, Citation2020). We argue that in Tegalrejo, mobility barriers and enablers are shaped by a constellation of inter-related physical and socio-cultural factors. In particular, a neighbourhood’s informality generates both advantages and disadvantages in terms of accessibility and people with disabilities’ capacity to take tactical actions to adapt with their surrounding environment and support their mobility and movement. These findings contribute to the literature on disability, place, and mobility in urban contexts by heeding the call to consider lower-middle income countries’ viewpoints (Watson & Vehmas, Citation2020).

Disability, place, mobility and urban informality

Over the past few decades, questions of mobility and accessibility for people with disabilities in urban contexts have gained growing attention from scholars who have used various approaches within human geography, disability studies, urban planning, and other disciplines (Amaral et al. Citation2023; Bennett, Citation1988; Calder-Dawe et al. Citation2020; Imrie, Citation2000; Imrie & Thomas, Citation2008; Porębska et al. Citation2021; Warnicke & Kristianssen, Citation2023). Mobility is one of the most critical well-being determinants for people with disabilities (Imrie, Citation2000; Imrie & Thomas, Citation2008). Like communication and self-care, mobility is considered an essential everyday core activity, and need for support in mobility is often used as an indicator of disability (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2018). From a social model of disability perspective, the mobility of people with disabilities is affected by the physical and social environment (Anaby et al. Citation2013; Basha, Citation2015; Clarke et al. Citation2008; Imrie, Citation2000; Imrie & Thomas, Citation2008). Mobility barriers encompass any physical or non-physical feature that hinders the free movement of people with disabilities, while enablers act in the opposite way (Anaby et al. Citation2013; Imrie, Citation2000; Imrie & Thomas, Citation2008; Lid & Solvang, Citation2016; Smith et al. Citation2021). Environmental mobility barriers are but one dimension of exclusion of people with disabilities; but being able to move around is essential for participation in varied social activities (Anaby et al. Citation2013; Lid & Solvang, Citation2016; Wiesel & van Holstein, Citation2020).

Studies from high-income countries show that physical barriers often include a wide array of environmental features, from the condition of public infrastructure, through to weather, distance, and crowdedness (Anaby et al. Citation2013; Hammel et al. Citation2015; Imrie, Citation2000; Imrie & Thomas, Citation2008; Lid & Solvang, Citation2016). Meanwhile, non-physical barriers encompass cultural and societal attitudes towards, and relations with, people with disabilities (Butler & Bowlby, Citation1997; Imrie, Citation2000; Imrie & Thomas, Citation2008; Smith et al. Citation2021). Social expectations and norms can also influence mobility and everyday participation of people with disabilities in public and community activities. Goggin (Citation2016), for example, notes that crawling can allow a person with disability to access buildings but can also be experienced as embarrassing or humiliating.

Barriers and enablers to mobility can be experienced differently by different people with disabilities (Anaby et al. Citation2013; Chapman et al. Citation2023; Lid & Solvang, Citation2016; Omura et al. Citation2020). For instance, tactile pavements can be a useful assistive device for people with visual impairments, but this feature can be a severe impediment to wheelchair users (Lid & Solvang, Citation2016). Assistance from others can help some people with disabilities negotiate environmental barriers to movement in urban public space, but can also make some people feel powerless or dependent (Butler & Bowlby, Citation1997). Indeed, the relation between people with disabilities and mobility barriers or enablers are often characterised by such ambivalence (Lid & Solvang, Citation2016). These insights – primarily from studies from high-income countries – highlight that mobility is not only about functional capacity to move from one place to another, but also the ability to do so safely, comfortably, and with dignity. Dignity in the context of mobility and movement for people with disabilities reflects acceptance and inclusion, and capacity to equally and independently participate in social life without experiencing shame, discrimination, and humiliation (Chapman et al. Citation2023).

Empirical studies from low- and middle-income countries such as Kosovo (Basha, Citation2015), Malaysia (Hashim et al. Citation2012), Ghana (Naami, Citation2019; Owusu-Ansah et al. Citation2019), Nigeria (Bombom & Abdullahi, Citation2016), India, Malawi, Mozambique, Mexico, and South Africa (Chakwizira et al. Citation2021; Venter et al. Citation2002), and Zambia (Banda-Chalwe et al. Citation2014) also show a wide range of barriers and enablers affecting the everyday participation of people with disabilities in public activities and their mobility and movement in urban settings. Yet, the cultural and religious norms which affect the mobility and participation of people with disabilities in these countries differ from those of higher-income countries (see for example Banda-Chalwe et al. Citation2014; Basha, Citation2015; Bombom & Abdullahi, Citation2016). For example, in Nigeria, women with disabilities are often restricted from participation in societal activities because of local beliefs that limit their appearance in public (Bombom & Abdullahi, Citation2016). In Zambia, traditional beliefs still see disability as an ancestral curse which forces families to hide children with disabilities from their community (Banda-Chalwe et al. Citation2014). Such examples illustrate that researching mobility and everyday participation of people with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries is vital because their experience may differ due to distinct locality and socio-cultural situations (Watson & Vehmas, Citation2020).

In Indonesia, similar studies are also emerging, although focus on the local settings of the country’s diverse urban neighbourhood environments is still limited (see Ferdiana et al. Citation2021; Hayati & Faqih, Citation2013; Hidayati et al. Citation2021; Muhaemin, Citation2019; Qur’ana & Purnomo, Citation2020; Tanuwidjaja et al. Citation2018). Indonesian case studies can challenge existing knowledge about the influence of neighbourhoods’ settings on the mobility and participation of people with disabilities that has drawn primarily on high-income countries’ perspectives (Clark et al. Citation2020; van Hoven & Meijering, Citation2019). The presence of informality and rural-like relationships (e.g. mutual collaboration and burden sharing within community members) in Indonesian urban neighbourhoods, locally referred to as kampung (Roitman & Rukmana, Citation2022), may also provide a unique angle on questions of mobility and participation.

Literature surrounding informal urbanism suggests that informality is one of the distinctive characteristic of cities in the Global South (Dovey, Citation2012; Marinic & Meninato, Citation2022). Urban informality usually shows in the form of built environment and informal practices, such as street trading, parking, and transporting (Dovey, Citation2012; Marinic & Meninato, Citation2022; Oviedo Hernandez & Titheridge, Citation2016). Tactics, such as sharing space (street alleys) (Roitman & Rukmana, Citation2022) and alternative travel strategies (Oviedo Hernandez & Titheridge, Citation2016), are examples of adaptations emerging from urban informality to negotiate everyday challenges. Communal relations and a collectivist approach to community supports, safety, survival, and mutual aids are also salient characteristics of urban informality, representing ‘practices of urban commoning’ amongst informal urban residents and their dense social networks (Leitner et al. Citation2022; Sheppard et al. Citation2020). While the material form and complexity of informality (such as poorly maintained infrastructure) somehow disadvantage residents’ mobility and generate gendered challenges (see for example Hosseini et al. Citation2023), informality does not always negatively influence urban life as it can also help residents to adapt to everyday accessibility challenges and improve connectivity for people with various spatial needs (Oviedo Hernandez & Titheridge, Citation2016).

Mobility and participation of people with disabilities in Indonesia are shaped by relatively high socio-economic inequalities (Komardjaja, Citation2001b). Responses to improve accessibility tends to be middle-class centric, where urban middle-class with disabilities usually have servants to assist them in daily tasks (Komardjaja, Citation2001b, Citation2001a). Traditional customs which require squatting or sitting on the floor in traditional community activities or household tasks are also a factor leading to the exclusion of people with disabilities (Komardjaja, Citation2001a). These socio-economic, political, cultural, and urban neighbourhood contexts of Indonesia provide a timely backdrop to extend the existing knowledge about disability, place, and mobility in urban settings from low- and middle-income countries’ lenses.

Building upon these theoretical frameworks, we aim to investigate the mobility and everyday participation of people with mobility impairments in Indonesian urban neighbourhoods. Using a fieldwork data conducted in Tegalrejo Sub-District, we focus on some questions including what barriers/enablers do people with mobility impairments encounter in their everyday participation in public activities in Tegalrejo? And how do physical, socio-cultural, and informal settings of Tegalrejo’s neighbourhoods affect their participation?

Methodology

Research design and study area

This research is a case study which aims to unpack the ways in which informality and socio-cultural norms influence the mobility and participation of people with mobility impairments in public activities. A case study methodology has been widely used both in social sciences and practice-oriented fields such as planning and social works (Baxter & Jack, Citation2015; Johansson, Citation2007; Tellis, Citation1997). The application of this methodology is to explore the complexity of a single case, in its ‘natural’ context and using various methods (Johansson, Citation2007). Our case study in this paper concerns the everyday lives of people with mobility impairments in an Indonesian urban neighbourhood. While there is a growing body of research surrounding the accessibility of Indonesian urban space for people with physical disabilities (see for example Ferdiana et al. Citation2021; Hayati & Faqih, Citation2013; Hidayati et al. Citation2021; Muhaemin, Citation2019; Qur’ana & Purnomo, Citation2020; Tanuwidjaja et al. Citation2018), studies focused on the urban neighbourhood scale are still few.

There are five levels of governments in a vertical hierarchy structure in Indonesia: national (Nasional), provincial (Provinsi), district/municipality (Kabupaten/Kotamadya), sub-district (Kecamatan), and urban suburbs/neighbourhoods (Kelurahan) or rural village (Desa) (see Asmorowati et al. Citation2022). Within rural villages and neighbourhoods, there are two subsidiaries levels called local neighbourhoods (Rukun Tetangga – RT) and hamlets (Rukun Warga – RW) (Asmorowati et al. Citation2022). Moreover, in urban Indonesia, there are also kampung which have relatively homogeneous population characteristics, informal settings, and rural-like relationships (Hutama, Citation2016; Roitman & Rukmana, Citation2022; Setiawan, Citation2020). The terminology of kampung is sometimes elusive, as it is difficult to stipulate its administrative units (Hutama, Citation2016). Linkages and exchanges between residents in kampung are often guided by cultural and religious values, materialised in dwellers’ collective practices through burden sharing and mutual collaborations (Kellett & Bishop, Citation2006; Roitman & Rukmana, Citation2022). In Java generally and Yogyakarta specifically, cultural values and collective norms such as hidup rukun (living harmoniously), gotong-royong (mutual help), and tepo sliro (tolerance) remain widely upheld as societal ideals that guide/regulate the everyday interactions of communities living in urban neighbourhoods or kampung (Rahmi et al. Citation2001; Setiawan, Citation2020).

In this paper, we focus on urban neighbourhood settings of Tegalrejo Sub-District, Yogyakarta City, in the Special Province of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Tegalrejo is in the west area of Yogyakarta City. This sub-district has an area of 2.91 Km2 and consists of four urban neighbourhoods (Bener, Kricak, Karangwaru, and Tegalrejo). We chose Tegalrejo because it is stipulated as one of four pilot projects of inclusive sub-districts in Yogyakarta City. With the stipulation, the city government can access resources to initiate pilot projects that improve physical accessibility in public spaces and empowerment programmes for people with disabilities. In 2021, it was estimated that 37,391 people resided in Tegalrejo (Statistics of Yogyakarta Municipality, Citation2022). It is a relatively dense part of Yogyakarta, with a mix of residential and trading areas, medium-high densely populated settlements, and the presence of rivers which contribute to a varied terrain, including both steep and flat areas. In addition, Tegalrejo has 16.7 Ha (5.7% of its total area) of informal settlements located predominantly along the riverbanks (Yogyakarta Mayor Decree No.158/2021 on Pilot Projects of Inclusive Sub-District in Yogyakarta City). These characteristics will help us to generate meaningful and locally situated insights around participants’ experience of mobility and participation in their urban neighbourhood.

Participants

Participants recruited in this study are residents of Tegalrejo with mobility impairments, who use mobility aids (wheelchairs/canes/crutches/walkers) or have difficulty walking three blocks (Gray et al. Citation2008). We used quota sampling to purposely recruit participants with varying socio-demographic characteristics. The number of participants was 14 adults (≥18-years-old), consisting of 7 men and 7 women, all from Javanese ethnic groups. Seven participants were older adults (≥60-years-old), five of them were middle adult (≥35–59-years-old), and the rests were young adults (≥18–34-years-old).

Ten participants reported that they had experienced mobility impairments due to illnesses, genetic disorders or other medical conditions (for example, pinched nerves (syaraf kejepit)). Some participants acquired disability at a young age, for instance due to polio (seven participants). Other participants acquired disability at an older age, for example because of stroke or accidents. Seven participants used wheelchairs and two used canes, while the rest did not use mobility aids.

Half of the participants did not work. Some described themselves as housewives who were not engaged in any work to generate income. Meanwhile, unemployed male participants expressed they could not work with their recent condition or were still looking for a job. Five participants were working in different jobs mostly in casual or informal employment, including selling food, working as a freelance graphic designer, mosque keeper (penjaga masjid/marbot), and scavenger (pemulung). Others were engaging in full-time jobs such as sport centre keeper and parking attendant (tukang parkir). At the time of fieldwork, all but one participant lived with their family, spouse, or relatives in their house.

Data collection

We collaborated with the Disability Inclusive Sub-District Forum of Tegalrejo (Forum Kecamatan Inklusi Tegalrejo - FKIT) to recruit participants. The recruitment took place in the beginning of February 2022. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Office of Research Ethics and Integrity, the University of Melbourne (reference number 2022-23031-25324-3). We obtained written consent for participation from all research participants before data collection was conducted.

Data collection was conducted through sit-down and go-along interviews, as well as GPS tracking/plotting. Sit-down interviews were semi-structured and constituted the primary method for data collection. We used this method to collect information from all participants. Each interview session took 30–60 min, and mostly took place in participants’ homes. In addition, interviews were also conducted in participants’ workplaces such as a sport centre and parking lot. Participants used a mix of Javanese and Bahasa Indonesia during the interview sessions.

Go-along interviews (Carpiano, Citation2009; Kusenbach, Citation2016) aimed to understand localities and everyday activities of participants, while documenting everyday mobility barriers and enablers encountered by them. We accompanied eight participants in their everyday routes in the neighbourhood. Every go-along interview took 20–90 min, depending on the length of the journey. During the interview, we also documented physical barriers and enablers participants encountered, and completed GPS plotting using Maverick – an Android-based application – to document the coordinates of mobility barriers and enablers. The combination of go-along methods and GPS tracking provides opportunities to understand social and physical phenomena in the context of locally situated daily lives (Martini, Citation2020). Based on our fieldwork, go-along interviews generated valuable information about the way participants perceived their neighbourhood and places they usually visited.

Data analysis

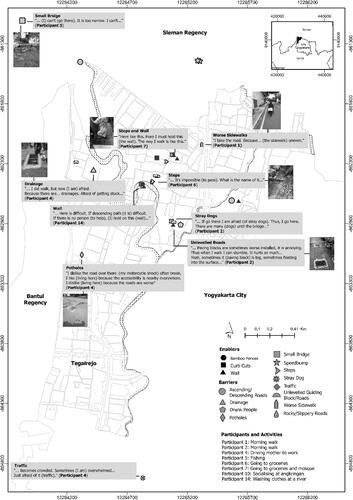

The interviews have been transcribed verbatim and coded using N-Vivo software. Thematic analysis was then used to analyse and frame information from the coded themes (Clifford et al. Citation2016). This analysis generated a primary theme about mobility barriers and enablers participants encountered in their everyday participation in public activities in Tegalrejo’s neighbourhoods and beyond. In addition, data from go-along interviews and GPS tracking were analysed through qualitative Geographic Information System (GIS) (Boschmann & Cubbon, Citation2014; Mavoa et al. Citation2012) using ArcGIS Pro Software to produce a distributional map of mobility barriers and enablers. This approach is beneficial to understand individual spatial narratives in geographic research (Boschmann & Cubbon, Citation2014; Mavoa et al. Citation2012) and provide insights into participants’ mobility and movement experiences in spatial contexts. In the following ‘Results’ section, we reflect on two themes that emerged from our analysis: the urban informality, and distinctive socio-cultural norms in Tegalrejo, and their impact on mobility and participation of people with mobility impairments.

Result

Informality and physical barriers to mobility and participation

Informality has played a significant role in shaping Tegalrejo’s built environment, and the formation of barriers to mobility and participation, but also some important enablers. Some areas in Tegalrejo are categorised as informal settlements, mainly located in riverbank areas where some of the participants lived. Informal settlements along riverbanks in Yogyakarta City mostly lack basic infrastructure (including roads) with high population density (Hutama, Citation2016; Roitman & Rukmana, Citation2022; Setiawan, Citation1998). With little or no planning in such informal settlements, their built environment’s development has been haphazard (Roitman & Rukmana, Citation2022).

The haphazard development of the built environment in Tegalrejo was reflected in the inconsistency of materials used in public roads/alleyways/pathways/sideroads and lack of maintenance in such facilities. In the go-along-interviews, we found inconsistent road materials passed by participants from different neighbourhoods (). Paved roads were usually found in wide alleys connected with main roads while roads with paving blocks and tiles were typically dominant in narrow pathways (). This form of informality negatively affected the mobility and movement of some participants. For instance, inconsistent road building material influenced participants’ feelings when travelling. Many, especially wheelchair users, said paved/concrete roads () commonly had flat surfaces. This road material was preferable for them, as it improved comfortable feeling and enjoyment.

Photo 1. Participant 6 was helped by her carer to move her wheelchair when passing a block paved road to go to a grocery store. The paving blocks were poorly installed. They popped up, making the road surface bumpy and restricting wheelchair’s movement.

Photo 2. Paving blocks along Participant 10’s journey to an angkringan (street food stall). They were better installed but the road surface was still not flat.

Photo 3. Tile and ceramic surfaces can be found alongside Participant 7’s routes to mosques. The surfaces of these materials were slippery.

Photo 4. A photo of Participant 1 on a wheelchair and his carer. Participant 1 usually passed concrete roads in his weekly morning outing. The concrete roads had flat surfaces which improved comfort for wheelchair users..

Photo 5. A photo of Participant 1 on a wheelchair and his carer. Participant 1 prefered to go through the road with his wheelchair, because the sidewalk was in poor condition, with cracks and grass growing on it.

In contrast, concrete block pavements and ceramic floors inside and outside a building were less comfortable. Some participants said poorly installed paving blocks (popping up) restricted their wheelchair movement. The poorly-paved road also often made participants stumble when walking on it. In addition, others using canes/crutches explained that ceramic surface was risky, because their canes/crutches tips could slip and make them fall (). Lack of maintenance was also found in sideroads, where the presence of sideroads for pedestrians was not compensating for the quality. Many who used wheelchairs preferred to wheel on the main road because the sideroads were in poor condition and inaccessible (). Participant 1 (83-years-old) suggested that if his neighbourhood had proper and accessible sideroads, he would use them instead of wheeling on the road. He was self-conscious that wheeling on the road had considerable safety risks, mainly because he used a wheelchair that needed more space to move, but he did not have another choice.

The variation in Tegalrejo’s physical configuration – with a mix of formal and informal spaces, and very different terrains – led to stark differences in participants’ experiences of mobility and participation. Some participants lived on riverbanks with downhill and uphill pathways (), while others lived far from the riverbanks with relatively flat terrains (). Participant 13 (58-years-old) felt that steps were a significant barrier to his mobility and movement. Yet, he argued he never encountered impediments when walking in his neighbourhood, as it had no steps or descending/ascending pathways. This spatial configuration of the neighbourhood thus enabled him to go, in relative ease, to warung (informal stall selling groceries, ready-to-eat foods, or snacks) or attend community events, such as gotong-royong (mutual help). In contrast, Participant 14 (49-years-old), who lived around 20 metres from a river, experienced difficulties when she wanted to wash clothes at the river, go to warung or the main road to work.

Photo 7. An illustration of a neighbourhood in Tegalrejo with flat terrain far away from riverbanks.

Steps, uneven sidewalks, bumpy roads, narrow pathways, speed bumps, potholes, descending/ascending paths, and slippery road materials were typical physical barriers faced by participants. This finding aligns with previous studies from high-income countries, showing that people with other impairments, notably visual impairments, also encounter the same obstacles (Hammel et al. Citation2015; Smith et al. Citation2021). Steps and uneven sidewalks were the most common obstacles encountered by participants. Yet, similar physical barriers had different effects on different participants. Some reported that they could not handle steps and required assistance to lift their wheelchairs or hold their body to keep it steady when passing stepped roads or pathways. Some even decided to avoid bumpy roads and chose other pathways with better conditions when travelling. Others did not have any choice but to cross less accessible paths and tried to be alert and careful when doing so.

Indeed, as shown in , some felt obstacles in their neighbourhoods significantly affected their mobility and movement. Others were able to move, but such obstacles – and the tactics they used to overcome them – caused them discomfort. Participant 7 (65-years-old), for example, said the presence of steps made her choose a longer route when she wanted to buy groceries. Choosing a detour to reach her destination without steps points to a trade-off between distance and comfort, where different participants might make different choices regarding their mobility strategies. Participants’ choices also reflected a desire to avoid anxiety and uncertainty in their movements and activities (Hall & Bates, Citation2019).

Photo 8. A map depicting spatial distribution of mobility barriers and enablers in Tegalrejo’s neighbourhoods. Participants’ activities varied, including going to morning walks, driving their mother to work, fishing, groceries shopping, and washing clothes at a river. Mobility barriers encompassed drainages, potholes, small bridges, speedbumps, and steps, while mobility enablers consisted of bamboo fences, curb cuts, and walls. This map also includes quotes from participants describing their experiences towards mobility barriers and enablers in their daily activities. For example, Participant 2 reported her experience of mobility barriers by saying, ‘if I go there, I am afraid of stray dogs. Thus, I go here. There are many stray dogs until the bridge’. Another example is a quote about mobility enablers from Participant 7 who said, ‘Here is like this, Here I must hold on to this wall. The way I walk is like this’.

Nonetheless, informal infrastructures in the neighbourhoods sometimes served as enablers of mobility and participation for participants. Informal infrastructure such as bamboo fences (), walls, and tali jemuran (clothes lines) () were vital to support participants’ mobility. One tactic used by some participants involved holding on to such informal infrastructures to ease their mobility and movement. Participant 11 (58-years-old) said that the clothes lines helped him feel secure when going to the mosque where he worked as a mosque keeper (penjaga masjid/marbot). He explained how hanging on the clothes lines helped him feel at ease with his movement during his short travel to work (around 15 metres from his home to the mosque). Participant 14 (49-years-old) also reported that she usually held on to bamboo fences when going to wash clothes in the river. Holding on this informal infrastructure increased her safety when going down and up stairs.

Photo 9. Bamboo fences situated nearby Participant 14’s house which helped her to increase safety when going to a river for washing clothes. The fences were installed by her neighbour..

Photo 10. Clothes lines situated between a mosque and Participant 11’s house. The clothes lines were owned and installed by Participant 11’s family and used to dry chlotes.

The physical landscape of the neighbourhood has changed over time. Participants 5 (55-years-old) and 13 (56-years-old) suggested that in the past their neighbourhoods had dirt roads, making them slippery and unsafe, especially in the wet season. Factors such as rice field dominance in land use, and limited access to electricity, and small populations in the past also discouraged some participants from going for outside because they were afraid of begal (robbers) when walking around their neighbourhood. Nevertheless, participants argued that infrastructure in Tegalrejo has since improved. This situation was indicated by the presence of electricity, paved roads, and ramps in governmental offices. Population growth, which was reflected by a significant increase in the numbers of surrounding houses, was also regarded as a positive change, as participants contended it made the neighbourhood safer when they travelled outside.

Socio-cultural barriers and enablers of mobility and participation

Non-physical barriers found in this research consisted of the attitudes toward people with mobility impairments and socio-cultural dynamics in the neighbourhoods more broadly. Examples included lack of permission from a spouse or other family members to travel outside, negative attitudes, stigma, and the lack of information received by participants to take part in community events. A term used by some participants to describe a particular socio-cultural barrier to mobility and participation was pemakluman, which is used in Javanese culture with the meaning of being explicitly ‘excused’ or implicitly excluded from activities other community members are expected to participate in. Pemakluman was a salient factor that restricted participants from attending or actively participating in community events such as pertemuan warga (community meetings), arisan (rotating saving credit), or gotong-royong/kerja bakti (mutual help). For example, although Participant 1 (83-years-old) received invitations to attend community meetings, he was not expected to come. Participant 10 (65-years-old) reported that he decided to attend gotong-royong or kerja bakti (a mutual help event), but his role there was that of a spectator rather than active participants. Other community members asked him to merely sit and converse with others in the location, with no expectation to take part in more active exchanges. This story reflected the notion that inclusion and exclusion are often intertwined (Power and Bartlett, Citation2018). He said he did not have strong feelings about this, because at least he could show up and ngumpul/srawung (gather) with others. Srawung as an everyday social practice and fundamental ethical value in Javanese culture and communities (Itriyati, Citation2020) was believed to strengthen social relation for many participants. Such norms challenge Global North understandings that tend to depict ‘community presence’ as a flawed and incomplete form of ‘community participation’ (O’Brien & Lyle, Citation1988).

Lack of permission from a spouse or other family members to travel or participate in events was a significant factor affecting participants’ mobility, reflecting an intersection of gender norms and ableism in the context of Javanese and Indonesian culture. Common expressions used by family/spouse to disallow participants’ mobility were nggak boleh/dibolehin (not permitted/allowed) or suami/anak tidak mengizinkan (spouse/children were not allowing). Participant 2 suggested she wanted to go to her childhood house, not far away from her recent home, but her husband always prohibited her from going:

I can go there, I am strong, but not allowed (Participant 2, 62-years-old).

Attitudes of people outside the family also generated restrictions on mobility and participation. Participant 2 (62-years-old) often encountered motorists whose negative attitudes made her afraid of spending time and moving outdoors during her routine morning walks. Because she could not walk fast, motorists sometimes mocked her for disturbing the traffic flow. She would feel annoyed when motorists honked the horn to warn her to pull over from roads and let vehicles pass. This experience made her reluctant to walk in the afternoon or evening when the traffic is busier. Thus, she always went out to walk in the morning before sunrise (around 05.30 am) and returned home before 7 am. Participants would self-exclude based on their own past experiences, as well as other people’s negative experiences. Participant 12 (72-years-old), for example, has never gone to malls or department stores. She was triggered by a story of another friend with a disability, who was discriminated against by shop keepers.

In contrast, some sociocultural norms served as enablers of mobility and participation. Some participants noted positive attitudes from other community members that provided feelings of safety when they travelled outside their homes. Participant 5 said that when he travelled alone and pushed his wheelchair along to a fishing pond to do his hobby, motorists tended to stop or slow down. This attitude gave him space to pass narrow alleys first. He said:

When there are cars or motorbikes, (they) slow down… Motorists always slow down (Participant 5, 55-years-old).

Receiving assistance from others for mobility and participation was a complex and at times contentious issue for participants. Our interviews suggested that assistance could be easily sought because family/community members are expected to peduli sesama (care for others, especially for marginalised groups including people with disabilities). Participants also believed that saling (an act which reflects a mutual and reciprocal relations e.g. respecting and helping others) was a standard ethical value to practice for both people with and without disabilities living in Tegalrejo. These caring behaviours were deemed as a factor encouraging family and other community members to offer such support and assistance to relatives with a disability.

Assistance from others did not aim to remove, but to negotiate barriers and improve safety for movement in and out of the house. Many preferred to be assisted or accompanied when travelling outside. Some would avoid going outside altogether if none of the family members could accompany them. They argued that travelling in the company of others could help avoid unwanted incidents and ease their mobility. Some believed that companions made them feel more confident, countered isin (shame) in public, and provided opportunities to have a conversation during travelling.

However, some participants often declined assistance from others, because of guilt and concerns about negative public perceptions of people receiving assistance. Participant 7 (65-years-old), for example, believed that receiving help from others would reinforce her stigma as a powerless and incapable human being. As a result, she always tried to do all tasks by herself to show others her capability and independence. Some participants also said their neighbours often commented negatively and expressed pity for family members who assisted participants. Participant 1 suggested:

Although I was accompanied and assisted by my wife, I feel guilty. People (meeting us) in (our morning) walks, feel pity for my wife… It is when I walk (with my wife) a long distance. Other people seem to think that she might get tired, feeling tired… Sometimes I also feel sorry (for my wife) (Participant 1, 83-years-old).

In my house, all (necessities) is provided by my wife. Yet, when I was able to walk, I could do (my household chores) by myself. I feel sorry if all (of the household tasks) is done by my wife (Participant 1, 83-years-old).

I want to pursue some activities like selling food, but my condition obstructs (me from doing so). I really want to… Honestly, I do not want to burden my children, although my children always say, ‘Bapak, (you) do not have to be hard (on yourself), Bapak can just stay at home. If (Bapak) needs anything, (just) let us know (Participant 10, 65-years-old).

Our interviews also found that not everyone was willing to receive assistance from people outside their family. Most participants said they would be reluctant to receive help if the helpers were not their spouses/family members. Most participants who needed assistance, such as wheelchair users, preferred to be accompanied by their family members when leaving their home. They said safety could be obtained when their family members accompanied them, because they were the most familiar persons to help.

Participants recognised changes over time to socio-cultural norms in the Tegalrejo, which had both positive and negative effects on their mobility and participation. Many said they experienced bullying and discrimination as a child. Participant 9 (71-years-old) even preferred to exclude herself from society by staying at home, because her childhood friends often mocked her impairments. Yet, many felt Tegalrejo has changed for the better and is now more supportive for people with disabilities. They noted its increased social cohesion, reflected by commonalities, reciprocal relations, and kind actions from community members. At the same time, our interviews also revealed a tension, whereby being independent was an important part of participants’ identities albeit they lived in a more collectivist urban village (kampung) (Roitman & Rukmana, Citation2022). In this context, the notion of guilt for not being independent and refusal to accept assistance also reflect, to some extent, generational changes, modernisation, and individualisation in Javanese culture (Mangundjaya, Citation2013), and in Tegalrejo.

Discussion

Our findings echo previous literature on disability, place, and mobility in urban contexts about the kinds of mobility barriers and enablers encountered by people with disabilities (see Banda-Chalwe et al. Citation2014; Butler & Bowlby, Citation1997; Hammel et al. Citation2015; Imrie, Citation2000, Citation2004; Imrie & Thomas, Citation2008; Lid & Solvang, Citation2016; Smith et al. Citation2021). Some barriers and enablers encountered by research participants may also impact on people who have other impairments, notably visual impairments (Hammel et al. Citation2015; Smith et al. Citation2021). However, our empirical results add to existing literature, illustrating how neighbourhood conditions in Tegalrejo affect and influence inclusion and exclusion of people with mobility impairments, with a particular on aspects of urban informality, and socio-cultural norms. These themes reflect the nuanced differences in understanding mobility and disability from lower-middle income and high-income countries’ perspectives.

Distinct socio-cultural norms shaped participants ability to move around and participate in activities in and beyond their neighbourhood. Negative attitudes in everyday activities (mocked by motorists and discriminated by shop keepers) experienced by women (Participants 2 and 12) reflect intersections of gender and disability, in a particular sociocultural context. These participants’ stories imply that having impairments may reinforce broader issues of fear of gender violence in public spaces (Thomas, Citation2006).

Tegalrejo’s kampung collectivism – an urban village with rural-like tightly knit communal relations through the practice of saling (an act which reflects a mutual and reciprocal relation), ngalah (place others’ desires above one’s own), and peduli sesama (care for others) – has some advantages for mobility and participation of people with mobility impairments, such as the expectation of family members to provide informal support, and the range of communal activities people are invited to take part in. A more collectivist urban village (kampung) way of living may promote communal urban practices which are materialised in mutual aid, community support, safety, and survival (Leitner et al. Citation2022; Sheppard et al. Citation2020). However, our finding shows pemakluman (being explicitly excused from such activities) maintains the exclusion of people with mobility impairments from everyday public life and community activities. In Javanese cultures, pemakluman is expected as general people usually maklum (understand or sympathise) with the condition of people with disabilities (Itriyati, Citation2020). However, pemakluman can become a form of subtle exclusion. Itriyati (Citation2020) argues that pemakluman can strengthen victimisation and trigger feelings of disconnectedness, as people with disabilities are not expected to attend and fully participate in societal activities.

The analysis highlighted distinct socio-cultural dynamics related to willingness to give and receive informal support and care for people with mobility impairments in Tegalrejo. Participants in our study were more likely to accept such support from family, although some forms of informal care extended beyond nuclear families and households, particularly in the absence of care and service provision by the government. This reflects close-knitted familial relationship as a cultural norm that is salient in Indonesian urban kampung (Roitman & Rukmana, Citation2022). However, our findings contrast with the case of urban middle-class professional with disabilities in Indonesia who accept much of their support from paid domestic helpers or drivers rather than family members (Komardjaja, Citation2001b, Citation2001a). This contrast reflects intersection of cultural norms with social class, adding further nuance to enrich debates surrounding the meaning and significance of care and independence for people with disabilities in lower-middle income countries, such as Indonesia (Komardjaja, Citation2001a).

Urban informality played an important, albeit ‘ambivalent’ role in shaping mobility and participation of people with mobility impairments. The presence of informal infrastructures such as bamboo fences and clothes lines (tali jemuran) helped participants navigate their movement, as a form of tactical improvisation. Participants’ tactical actions to adapt with their surrounding environment also reflect agency which challenges common views suggesting people with disabilities are inherently vulnerable. In addition to easing some of the most pressing accessibility issues, informality strengthens connections amongst people who have various spatial demands and provides adaptability to various everyday challenges and tensions (Oviedo Hernandez & Titheridge, Citation2016). However, the lack of standardisation reflected in inconsistent materials in roads, pathways, alleyways, sideroads and sideroads maintenance also limited the mobility and movement of participants. The dual role of informality thus made the relationship between disability and accessibility more complex, ambivalent, and dynamic. This idea highlights the difficulty of implementing universal design principles (see Imrie, Citation2004; Komardjaja, Citation2001a, Citation2001b; Lid & Solvang, Citation2016) to pursue a barrier-free environment by establishing standardisation and removing barriers for people with disabilities, in an urban environment that is developed in informal, haphazard ways. Furthermore, the findings illustrating that barriers for some are also enablers for others points to the limits of standardisation.

Conclusion

A Global South, middle income countries’ perspective provides new insight on urban neighbourhood barriers to mobility and community participation of people with disabilities, that can challenge and enrich knowledge gained from research primarily focused on Global North, high income countries’ experience. Tegalrejo, Indonesia, offers an illustrative case study. While the findings affirm that improved ‘formal’ provision of accessible infrastructure will help improve mobility and participation of people with mobility impairments in Tegalrejo, our analysis also illustrated that informality is not only a barrier, but can also be an enabler of mobility, which is an important contribution to understanding disability, mobility, and participation in everyday activities. Furthermore, the analysis highlights the important role of distinct socio-cultural norms in Tegalrejo, such as its urban village (kampung) collectivist norms. However, people with mobility impairments are often explicitly ‘excused’ (pemakluman) from some aspects of such collectivism, leading to their exclusion. In praxis, our findings suggest the need for a more comprehensive understanding of disability inclusion and exclusion to support the inclusive city initiatives in Yogyakarta, which encompasses inter-related physical and socio-cultural facets and is attentive to the complex role of urban informality.

We acknowledge that this study has several limitations. First, although some barriers or enablers found in this study may also impact on people with other impairments, this research only focused on one type of disability – mobility impairments – and cannot be readily generalised to other types of disabilities and their distinctive embodied experiences (Imrie, Citation2000; Lid & Solvang, Citation2016). Second, this research is based on data drawn from a narrow study area with relatively culturally homogeneous participants. These aspects might limit the socio-demographic variance of participants involved in the study. Further research is therefore needed to understand the lived experience of people with disabilities in multiple or more extensive informal urban neighbourhood using an intersectional framework (e.g. Liasidou, Citation2013; Walker & Ossul-Vermehren, Citation2021). These approaches will contribute to examining the lived experiences of people with disabilities in middle income countries’ urban neighbourhood environments across diverse types of disability, gender, age, economic status, religion, and other social categories. The application of intersectional frameworks can help further explore themes regarding disability, place, mobility, and urban informality from lower-middle income countries’ viewpoints. Further inquiry surrounding spatiotemporality of the neighbourhood is also important to unpack how dynamic neighbourhood changes influence the inclusion/exclusion and enablement/disablement for people with disabilities.

Policy and legal documents

Law No. 8/2016 on Persons with Disabilities (Undang-Undang Nomor 8/2016 Tentang Penyandang Disabilitas).

Mayor Decree No 339/2016 on Pilot Projects of Inclusive Sub-District in Yogyakarta City (Keputusan Walikota Yogyakarta Nomor 339/2016 Tentang Penetapan Lokasi Kecamatan Percontohan Kota Inklusi di Kota Yogyakarta).

Mayor Decree number 158/2021 on Slum Housing and Settlement Locations in Yogyakarta City (Peraturan Walikota Nomor 158/2021 Tentang Penetapan Lokasi Perumahan Kumuh dan Permukiman Kumuh).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the significant contribution of participants who participated in this study and the Disability Inclusive Sub-District Forum of Tegalrejo (Forum Kecamatan Inklusi Tegalrejo - FKIT) which assisted us in participant recruitment process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aini, Q., H. Marlina, and A. Nikmatullah. 2019. “Evaluation of Accessibility for People with Disability in Public Open Space.” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 506 (1): 012018. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/506/1/012018

- Amaral, C., M. Chamorro-Koc, A. Beatson, U. Gottlieb, S. Tuzovic, and N. Bowring. 2023. “The Journey to Work of Young Adults with Mobility Disability : A Qualitative Study on the Digital Technologies That Support Mobility.” Disability & Society 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2023.2275521

- Anaby, D., C. Hand, L. Bradley, B. Direzze, M. Forhan, A. Digiacomo, and M. Law. 2013. “The Effect of the Environment on Participation of Children and Youth with Disabilities: A Scoping Review.” Disability and Rehabilitation 35 (19): 1589–1598. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.748840

- Asian Development Bank. 2011. “Inclusive Cities.” In Urban Development Series, edited by F. Steinberg & M. Lindfield. The Philippines: Asian Development Bank. https://www.think-asia.org/handle/11540/127

- Asmorowati, S., V. Schubert, and A. P. Ningrum. 2022. “Policy Capacity, Local Autonomy, and Human Agency: Tensions in the Intergovernmental Coordination in Indonesia’s Social Welfare Response amid the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Asian Public Policy 15 (2): 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/17516234.2020.1869142

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2018. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release.

- Banda-Chalwe, M., J. C. Nitz, and D. De Jonge. 2014. “Impact of Inaccessible Spaces on Community Participation of People with Mobility Limitations in Zambia.” African Journal of Disability 3 (1): 33. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v3i1.33

- Basha, R. 2015. “Disability and Public Space-Case Studies of Prishtina and Prizren.” International Journal of Contemporary Architecture 2 (3): 54–66. https://doi.org/10.14621/tna.20150406

- Baxter, P., and S. Jack. 2015. “Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers.” The Qualitative Report 13 (4): 544–559. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2008.1573

- Bennett, T. 1988. “Planning for Disabled Access.” Planning Practice and Research 2 (4): 8–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697458808722691

- Bombom, L. S., and I. Abdullahi. 2016. “Travel Patterns and Challenges of Physically Disabled Persons in Nigeria.” GeoJournal 81 (4): 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-015-9629-3

- Boschmann, E. E., and E. Cubbon. 2014. “Sketch Maps and Qualitative GIS: Using Cartographies of Individual Spatial Narratives in Geographic Research.” The Professional Geographer 66 (2): 236–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2013.781490

- Butler, R., and S. Bowlby. 1997. “Bodies and Spaces: An Exploration of Disabled People’s Experiences of Public Space.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 15 (4): 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1068/d150411

- Calder-Dawe, O., K. Witten, and P. Carroll. 2020. “Being the Body in Question: Young People’s Accounts of Everyday Ableism, Visibility and Disability.” Disability & Society 35 (1): 132–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1621742

- Cameron, L., and D. C. Suarez. 2017. “Disability in Indonesia : What Can we Learn from the Data?” Monash University & Australian Government.

- Carpiano, R. M. 2009. “Come Take a Walk with Me: The ‘Go-Along’ Interview as a Novel Method for Studying the Implications of Place for Health and Well-Being.” Health & Place 15 (1): 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003

- Chakwizira, J., P. Bikam, and T. A. Adeboyejo. 2021. “Access and Constraints to Commuting for Persons with Disabilities in Gauteng Province, South Africa.” In Urban Book Series: Inclusivity in Southern Africa, edited by H. H. Magidimisha-chipungu & L. Chipungu, 347–394. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81511-0_17

- Chapman, K., C. Ehrlich, J. O’Loghlen, and E. Kendall. 2023. “The Dignity Experience of People with Disability When Using Trains and Buses in an Australian City.” Disability & Society 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2023.2203307

- Clark, A., S. Campbell, J. Keady, A. Kullberg, K. Manji, K. Rummery, and R. Ward. 2020. “Neighbourhoods as Relational Places for People Living with Dementia.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 252 (March): 112927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112927

- Clarke, P., J. A. Ailshire, M. Bader, J. D. Morenoff, and J. S. House. 2008. “Mobility Disability and the Urban Built Environment.” American Journal of Epidemiology 168 (5): 506–513. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn185

- Clifford, N., French, S., Gillespie, T. W., & Cope, M. 2016. Key Methods in Geography, 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Dovey, K. 2012. “Informal Urbanism and Complex Adaptive Assemblage.” International Development Planning Review 34 (4): 349–368. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2012.23

- Ernawati, D. B., and R. Sugiarti. 2005. “Developing an Accessible Tourist Destination Model for People with Disability in Indonesia.” Tourism Recreation Research 30 (3): 103–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2005.11081492

- Errington, J. J. 1988. Structure and Style in Javanese: A Semiotic View of Linguistic Etiquette. University of Pennsylvania Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv5rf6kk

- Ferdiana, A., M. W. M. Post, U. Bültmann, and J. J. L. van der Klink. 2021. “Barriers and Facilitators for Work and Social Participation among Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury in Indonesia.” Spinal Cord 59 (10): 1079–1087. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00624-6

- Goggin, G. 2016. “Disability and Mobilities: Evening up Social Futures.” Mobilities 11 (4): 533–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2016.1211821

- Gray, D. B., H. H. Hollingsworth, S. Stark, and K. A. Morgan. 2008. “A Subjective Measure of Environmental Facilitators and Barriers to Participation for People with Mobility Limitations.” Disability and Rehabilitation 30 (6): 434–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280701625377

- Hadi, I., U. D. E. Noviyanti, I. R. Mohamad, and M. I. Abas. 2020. “The Urgency of Disability Accessibility in Gorontalo District Government Agencies.” Journal La Sociale 1 (3): 24–33. https://doi.org/10.37899/journal-la-sociale.v1i3.130

- Halimatussadiah, A., C. Nuryakin, P. A. Muchtar, A. Bella, and H. Rizal. 2018. “Mapping Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) in Indonesia Labor Market.” Economics and Finance in Indonesia 63 (2): 126. https://doi.org/10.7454/efi.v63i2.572

- Hall, E., and E. Bates. 2019. “Hatescape? A Relational Geography of Disability Hate Crime, Exclusion and Belonging in the City.” Geoforum 101 (March 2018): 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.02.024

- Hammel, J., S. Magasi, A. Heinemann, D. B. Gray, S. Stark, P. Kisala, N. E. Carlozzi, D. Tulsky, S. F. Garcia, and E. A. Hahn. 2015. “Environmental Barriers and Supports to Everyday Participation: A Qualitative Insider Perspective from People with Disabilities.” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 96 (4): 578–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2014.12.008

- Hashim, A. E., S. A. Samikon, F. Ismail, H. Kamarudin, M. N. M. Jalil, and N. M. Arrif. 2012. “Access and Accessibility Audit in Commercial Complex: Effectiveness in Respect to People with Disabilities (PWDs).” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 50 (July): 452–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.08.049

- Hastuti, Dewi R. K., R. P. Pramana, and H. Sadaly. 2020. Kendala Mewujudkan Pembangunan Inklusif terhadap Penyandang Disabilitas. The SMERU Research Institute. https://www.smeru.or.id/sites/default/files/publication/disabilitaswp_id_0.pdf

- Hayati, A., and M. Faqih. 2013. “Disables’ Accessibility Problems on the Public Facilities within the Context of Surabaya, Indonesia.” Humanities and Social Sciences 1 (3): 78. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.hss.20130103.11

- Hidayati, I., C. Yamu, and W. Tan. 2021. “Realised Pedestrian Accessibility of an Informal Settlement in Jakarta, Indonesia.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 14 (4): 434–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2020.1814391

- Hosseini, A., B. Marc, and A. Momeni. 2023. “The Complexities of Urban Informality : A Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Residents ‘ Perceptions of Life, Inequality, and Access in an Iranian Informal Settlement.” Cities 132 (January 2021): 104099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.104099

- Huripah, E. 2020. “Towards an Inclusive Social Welfare Institution for Disabilities: The Case of Indonesia.” Asian Social Work Journal 5 (1): 18–28. https://doi.org/10.47405/aswj.v5i1.122

- Hutama, I. A. W. 2016. Exploring the Sense of Place of an Urban Through the Daily Activities, Configuration of Space and Dweller’s Perception: Case Study of Kampung Code, Yogyakarta. www.itc.nl/library/papers_2016/msc/upm/hutama.pdf

- Imrie, R. 2000. “Disability and Discourses of Mobility and Movement.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 32 (9): 1641–1656. https://doi.org/10.1068/a331

- Imrie, R. 2004. “From Universal to Inclusive Design in the Built Environment.” In Disabling Barriers-Enabling Environments, edited by J. Swain, S. French, C. Barnes, & C. Thomas, 2nd ed., 279–284. SAGE Publications.

- Imrie, R., and H. Thomas. 2008. “The Interrelationships between Environment and Disability.” Local Environment 13 (6): 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830802259748

- Irwanto, Eva R. K., F. Asmin, L. Mimi, and S. Okta. 2010. The situation of people with disability in Indonesia : a desk review. In Center For Disability Studies Universitas Indonesia (Issue November). https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–-asia/–-ro-bangkok/–-ilo-jakarta/documents/publication/wcms_160341.pdf

- Itriyati, F. 2020. The Abandoned Survivors: Newly Disabled Women after the 2006 Earthquake in Yogyakarta, Indonesia [The Australian National University]. In The Australian National University (Issue March). https://search.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/abandoned-survivors-newly-disabled-women-after/docview/2457908558/se-2?accountid=41849

- Johansson, R. 2007. “On Case Study Methodology.” Open House International 32 (3): 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/OHI-03-2007-B0006

- Keeler, W. 1983. “Shame and Stage Fright in Java.” Ethos 11 (3): 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.1983.11.3.02a00040

- Kellett, P., and W. Bishop. 2006. “Reinforcing Traditional Values: Social, Spatial and Economic Interactions in an Indonesian Kampung.” Open House International 31 (4): 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/OHI-04-2006-B0008

- Komardjaja, I. 2001a. “New Cultural Geographies of Disability: Asian Values and the Accessibility Ideal.” Social & Cultural Geography 2 (1): 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360020028285

- Komardjaja, I. 2001b. “The Malfunction of Barrier-Free Spaces in Indonesia.” Disability Studies Quarterly 21 (4): 97–104. https://cursa.ihmc.us/rid=1R440PDZR-13G3T80-2W50/4. Pautas-para-evaluar-Estilos-de-Aprendizajes.pdf. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v21i4.321

- Kramer, E., T. Dibley, and A. Tsaputra. 2022. “Choosing from the Citizens’ Toolbox: Disability Activists as Political Candidates in Indonesia’s 2019 General Elections.” Disability & Society 39 (1): 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2022.2060800

- Kusenbach, M. 2016. “The Go-Along Method.” In Sensing the City: A Companion to Urban Anthropology, edited by A. Schwanhäußer, 154–158. Birkhäuser.

- Leitner, H., S. Nowak, and E. Sheppard. 2022. “Everyday Speculation in the Remaking of Peri-Urban Livelihoods and Landscapes.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 55 (2): 388–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211066915

- Liasidou, A. 2013. “Intersectional Understandings of Disability and Implications for a Social Justice Reform Agenda in Education Policy and Practice.” Disability & Society 28 (3): 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710012

- Lid, I. M., and P. K. Solvang. 2016. “(Dis)Ability and the Experience of Accessibility in the Urban Environment.” Alter 10 (2): 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2015.11.003

- Maftuhin, A. 2017. “Defining Inclusive City: Origin, Theory, and Indicators.” TATALOKA 19 (2): 93. https://doi.org/10.14710/tataloka.19.2.93-103

- Mangundjaya W. L. H. 2013. “Is There Cultural Change in the National Cultures of Indonesia?” Steering the Cultural Dynamics: Selected Papers from the 2010 Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, 59–68. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/105/

- Marinic, G., and P. Meninato. 2022. “Informality and the City.” In Informality and the City, edited by G. Marinic & P. Meninato. Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99926-1

- Martini, N. 2020. “Using GPS and GIS to Enrich the Walk-along Method.” Field Methods 32 (2): 180–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X20905257

- Mavoa, S., M. Oliver, N. Tavae, and K. Witten. 2012. Using GIS to integrate children’s walking interview data and objectively measured physical activity data. 2010. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1837.4400

- Muhaemin, A. B. 2019. “Walkability: Perspective from a Local Neighborhood in Bandar Lampung, Indonesia.” Inovasi Pembangunan: Jurnal Kelitbangan 7 (1): 1. https://doi.org/10.35450/jip.v7i1.118

- Naami, A. 2019. “Access Barriers Encountered by Persons with Mobility Disabilities in Accra, Ghana.” Journal of Social Inclusion 10 (2): 70–86. https://doi.org/10.36251/josi.149

- Nilan, P. 2009. “Contemporary Masculinities and Young Men in Indonesia.” Indonesia and the Malay World 37 (109): 327–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639810903269318

- Nilan, P., M. Donaldson, and R. Howson. 2007. Indonesian Muslim Masculinities in Australia. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/149

- O’Brien, J., and C. Lyle. 1988. Framework for accomplishment. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Framework+for+accomplishment&author=J.+O%27Brien&author=C.+Lyle&publication_year=1987

- Omura, J. D., E. T. Hyde, G. P. Whitfield, N. T. D. Hollis, J. E. Fulton, and S. A. Carlson. 2020. “Differences in Perceived Neighborhood Environmental Supports and Barriers for Walking between US Adults with and without a Disability.” Preventive Medicine 134 (September 2019): 106065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106065

- Oviedo Hernandez, D., and H. Titheridge. 2016. “Mobilities of the Periphery: Informality, Access and Social Exclusion in the Urban Fringe in Colombia.” Journal of Transport Geography 55: 152–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.12.004

- Owusu-Ansah, J. K., A. Baisie, and E. Oduro-Ofori. 2019. “The Mobility Impaired and the Built Environment in Kumasi: Structural Obstacles and Individual Experiences.” GeoJournal 84 (4): 1003–1020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-018-9907-y

- Porębska, A. E., J. Barnaś, and P. Gajewski. 2021. “Invisible Barriers: Excluding Accessibility from the Field of Interest of Architecture and Urban Planning in Poland.” Disability & Society 36 (6): 1021–1025. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1902281

- Power, A., & Bartlett, R. 2018. ‘I shouldn’t be living there because I am a sponger’: negotiating everyday geographies by people with learning disabilities. Disability and Society, 33 (4), 562–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1436039

- Qur’ana, A., and E. P. Purnomo. 2020. “Accessibility of People with Disabilities to Public Facilities in Yogyakarta City.”. Journal of Politics and Policy 3 (1): 1–14.

- Rahayu, S., U. Dewi, and M. Ahdiyana. 2015. “Pelayanan Publik Bidang Transportasi Bagi Difabel di Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta.” SOCIA: Jurnal Ilmu-Ilmu Sosial 10 (2): 108–119. https://doi.org/10.21831/socia.v10i2.5347

- Rahmi, D. H., B. H. Wibisono, and B. Setiawan. 2001. “Rukun and Gotong Royong: Managing Public Places in an Indonesian Kampung.” In P. Miao (Ed.), Public Places in Asia Pacific Cities (1st ed., pp. 119–134). Springer Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-2815-7_6

- Roitman, S., and D. Rukmana. 2022. Routledge Handbook of Urban Indonesia, edited by S. Roitman & D. Rukmana, 1st ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003318170

- Safitri, M. 2016. HI Supports Yogyakarta Municipality Government to Be Inclusive City. http://www.hi-idtl.org/en/hi-supports-yogyakarta-municipality-government-to-be-inclusivecity/

- Setiawan, B. 1998. Local Dynamics in Informal Settlement Development: A Case Study of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. University of British Columbia.

- Setiawan, B. 2020. “Rights to the City, Tolerance, and the Javanese Concepts of ‘Rukun’ and ‘Tepo Sliro’: A Portray from Five Kampungs in Yogyakarta.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 402 (1): 012005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/402/1/012005

- Sheppard, E., T. Sparks, and H. Leitner. 2020. “World Class Aspirations, Urban Informality, and Poverty Politics: A North–South Comparison.” Antipode 52 (2): 393–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12601

- Simanjuntak, J. 2019. “Accessibility for Persons with Disabilities in Trans Metro Bandung Services.” IJDS Indonesian Journal of Disability Studies 6 (2): 149–156. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.IJDS.2019.006.02.4

- Smith, M., O. Calder-Dawe, P. Carroll, N. Kayes, R. Kearns, E.-Y. (Judy) Lin, and K. Witten. 2021. “Mobility Barriers and Enablers and Their Implications for the Wellbeing of Disabled Children and Young People in Aotearoa New Zealand: A Cross-Sectional Qualitative Study.” Wellbeing, Space and Society 2 (July 2020): 100028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wss.2021.100028

- Statistics of Yogyakarta Municipality. 2022. “Kecamatan Tegalrejo Dalam Angka 2022.”

- Tamba, J, Universitas Brawijaya. 2018. “Exploring the Accessibility and Facility in Railway Station Used by Persons with Disabilities: An Experience from Kebayoran Railway Station, Jakarta.” IJDS:Indonesian Journal of Disability Studies 5 (1): 37–45. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.IJDS.2018.005.01.4

- Tanuwidjaja, G., C. Levina, C. Tandiono, and C. Tandiono. 2018. “Service Learning on Inclusive Design: Sidewalk Redesign for Siwalankerto, Surabaya, Indonesia.” SHS Web of Conferences 59: 01013. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20185901013

- Tellis, W. 1997. “Application of a Case Study Methodology.” The Qualitative Report 3 (3): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/1997.2015

- Thohari, S. 2014. “Pandangan Disabilitas Dan Aksesibilitas Fasilitas Publik Bagi Penyandang Disabilitas di Kota Malang.” IJDS Indonesian Journal of Disability Studies 1 (1): 27–37. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.ijds.2014.01.01.04

- Thomas, C. 2006. “Disability and Gender: Reflections on Theory and Research.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 8 (2-3): 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017410600731368

- UNESCO Inclusive Policy Lab. 2018. Inclusive Policy for Persons with Disabilities in Indonesia. https://en.unesco.org/inclusivepolicylab/e-teams/inclusive-policy-persons-disabilitiesindonesia

- van Hoven, B., and L. Meijering. 2019. “Mundane Mobilities in Later life - Exploring Experiences of Everyday Trip-Making by Older Adults in a Dutch Urban Neighbourhood.” Research in Transportation Business & Management 30 (March): 100375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2019.100375

- Venter, C., T. Savill, T. Rickert, H. Bogopane, a Venkatesh, J. Camba, N. Mulikita, C. Khaula, J. Stone, and D. Maunder. 2002. “Enhanced Accessibility for People with Disabilities Living in Urban Areas.” Knowledge Creation Diffusion Utilization, 1–41. http://www.globalride-sf.org/images/DFID.pdf

- Wahyuni, E. S., B. Murti, and H. Joebagio, Department of Occupational Therapy, Health Polytechnic Surakarta. 2016. “Public Transport Accessibility for People with Disabilities.” Journal of Health Policy and Management 01 (01): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.26911/thejhpm.2016.01.01.01

- Walker, J., and I. Ossul-Vermehren. 2021. “Re-)Constructing Disability through Research: Methodological Challenges of Intersectional Research in Informal Urban Settlements.” In Inclusive Urban Development in the Global South: Intersectionality, Inequalities, and Community 12: 167–181. ((

- Warnicke, C., and A. C. Kristianssen. 2023. “Safety and Accessibility for Persons with Disabilities in the Swedish Transport System–Prioritization and Conceptual Boundaries.” Disability & Society 0 (0): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2023.2215398

- Watson, N., and S. Vehmas. 2020. Routledge Hanbook of Disability Studies, edited by N. Watson & S. Vehmas, 2nd ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429279713

- Wibawa, B. A., and K. Widiastuti. 2019. “Obstacles of Accessibility for the Disabled People in the Campus 1 UPGRIS.” Journal of Architectural Design and Urbanism 1 (2): 34. https://doi.org/10.14710/jadu.v1i2.3397

- Wicaksono, T., J. I. G. Simamora, and G. H. Pradana. 2019. “Public Train Service in Yogyakarta for Difabel.” INKLUSI 6 (1): 47. https://doi.org/10.14421/ijds.060103

- Wiesel, I., and E. van Holstein. 2020. “Disability and Place.” In The Routledge Handbook of Place, edited by T. Edensor, A. Kalandides, & U. Kothari, 1st ed., 304–312. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429453267-27

- Yeo, R., and K. Moore. 2003. “Including Disabled People in Poverty Reduction Work: ‘Nothing about us, without us.” World Development 31 (3): 571–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00218-8