Abstract

The aim of this study is to explore with autistic adolescents, their perspectives and experiences related to autism. Situated in Australia, the study uses a qualitative methodology and a narrative approach. The findings illustrate a rich and nuanced understanding of autism for adolescents. Autistic adolescents place greater emphasis on difference and diversity rather than difficulty and highlight the positives and strengths of autism characteristics. The findings encourage the framing and conceptualisation of autism in relation to adolescents’ strengths and abilities whilst acknowledging experiences of anger, stress, and anxiety. Most adolescents describe feeling disconnected, emotionally and physically from others. The findings of this study indicate a need for increased awareness and practice of a strengths use in autism. This is to enhance understandings of autism, improve upon the wellbeing and mental health of autistic adolescents and to promote greater connectedness and belonging for this group amongst family, peers, and wider society.

Points of interest

This study explores how autistic adolescents in Australia perceive and experience autism.

It uses interviews to gather their personal stories and detailed understandings about autism.

The findings show a more detailed and realistic view of autism, going beyond common stereotypes.

The study highlights the importance of focusing on the strengths and abilities of autistic individuals.

It acknowledges that autistic adolescents often experience anger, stress, and anxiety, and feel disconnected from others both emotionally and physically.

The study emphasises the need to increase awareness and practices that use the strengths of autistic individuals to foster their wellbeing.

Introduction

The contemporary perspective in disability research and practice has been progressively shifting towards a strengths-based approach, particularly in the context of autism (Murthi et al. Citation2023; Taylor et al. Citation2023). This transition aligns with the principles of the social model of disability, which has been gaining prominence over recent years (Devenish et al. Citation2022). The social model, as described by Shakespeare and Watson (Citation2001) and Thoms and Burton (Citation2015, Citation2018) conceptualizes disability because of the interaction between individuals and their environment, thereby reframing the focus from individual limitations to environmental factors and from deficits to abilities.

Despite some criticisms (Haegele and Hodge Citation2016; Thoms and Burton Citation2018) the adoption of this model has been widely recognized as crucial for acknowledging and valuing diversity and strengths. In this context, strengths-based approaches in autism, advocated by researchers such as Donaldson, Krejcha, and McMillin (Citation2017) and Buntinx and Schalock (Citation2010), suggest viewing autism as an aspect of neurological diversity rather than a disorder, highlighting the strengths and competencies of individuals with disabilities.

Some authors (Murthi et al. Citation2023), including autistic authors, (Grant and Kara Citation2021; Urbanowicz et al. Citation2019) advocate for strengths-based approaches in understanding autism, emphasizing the importance of recognizing and nurturing the abilities of autistic individuals (Devenish et al. Citation2022). They discuss the benefits of qualitative research in capturing the diverse experiences and perspectives of autistic people that goes beyond the traditional deficit-focused models, allowing for a more holistic understanding. Such approaches enable researchers to explore the subjective experiences of autistic individuals, including their coping strategies, perceptions of their environment, and personal narratives, and offering invaluable insights into their worldviews, challenges, and strengths.

Recently, Courchesne et al. (Citation2022), highlighted that whilst research on lived experiences of autism has mostly focused on the insights of parents, siblings, teachers, and clinicians, it has lately begun to include the first-person perspectives of autistic people meaningfully or substantially (Bertilsdotter Rosqvist et al. Citation2019; Cascio, Weiss, and Racine Citation2020); Nicholas, Orjasaeter, and Zwaigenbaum Citation2019; Richards and Crane Citation2020; Tesfaye et al. Citation2019). There is research to indicate the value in seeking the perspectives of autistic people (e.g. Chown et al. Citation2017; Dindar et al. Citation2017; Fletcher-Watson et al. Citation2019; Frazier et al., Citation2018; Galpin et al. Citation2018; Hurlbutt and Chalmers Citation2002; Jones, Quigney, and Huws Citation2003; Parsons et al. Citation2019; Pellicano, Dinsmore, and Charman Citation2014; Pellicano et al. Citation2018; Scott-Barrett, Cebula, and Florian Citation2019; Woods et al. Citation2018). For example, how autistic people perceive and experience autism and how it influences their interactions with others, including family or peers.

Whilst the autistic perspective is gaining traction in research, knowledge of this group’s experiences is largely understood from an adult perspective and not from a child or adolescent perspective (Depape and Lindsay Citation2016; Kirby, Dickie, and Baranek Citation2014; Nicholas, Orjasaeter, and Zwaigenbaum Citation2019; Richards and Crane Citation2020; Tesfaye et al. Citation2019). Therefore, this study aimed to understand how autistic adolescents perceive and experience autism through an exploration of their autism narratives. By doing so, this study aims to add value and enrich this body of work by adding the perspectives of an autistic adolescent group.

As part of a larger study (Trew Citation2021) that investigated the role of autism and family relationships in families with an autistic adolescent, this study focuses on exploring the understanding and experience of autism from the narratives of autistic adolescents. Investigating this phenomenon is important, as without the perspectives of younger autistic people we will not know if there are other or preferred ways of being that might be experienced for this group. This knowledge might be used to reduce some of the environmental and intersectional barriers faced by younger autistic people and increase their social connections and sense of belonging amongst family and peers and in society, broadly. Additionally, without younger autistic perspectives it is unclear if autistic adolescent’s experiences and understandings of autism differs from others, including autistic adults. This knowledge could inform the development of tailored strategies or community-wide awareness campaigns that are informed by autistic adolescents’ perspectives and identify better ways to structure autistic supports, including the wants and needs of autistic adolescents. These might be in spaces such as school, amongst their peers and family, and in workplaces and the broader community.

Background

Autism research, traditionally aligned with the medical model, has primarily focused on studying autistic differences as deficits in comparison to the general population (Brown et al. Citation2021; Kapp et al. Citation2013). However, the autism community and current researchers, including Kornblau and Robertson (Citation2021), argue that these differences can be neutral traits or strengths in appropriate contexts. A growing body of research now aims to understand how autistic individuals’ strengths and interests can contribute to leading fulfilling and productive lives, focusing on identifying environmental barriers and employing strengths-based approaches to improve quality of life including in the home, at school, at work, and in the community (Clark & Adams, Citation2020; Urbanowicz et al. Citation2019).

Characteristics associated with autism

Autistic people’s strengths vary widely but can include exceptional memory, attention to detail, and proficiency in systematic and rule-based reasoning (Meilleur, Jelenic, and Mottron Citation2015). A qualitative study (Russell et al. Citation2019) highlights the autistic advantage, underscoring the diverse strengths in autistic adults, such as heightened perceptual abilities and detailed-focused cognitive styles. Additionally, their unique approach to problem-solving and deep focus on areas of interest can be advantageous, particularly in fields that require specialized knowledge or intense concentration. Urbanowicz et al. (Citation2019) also discusses the strengths of autistic individuals, emphasizing the potential for innovative thinking and unique perspectives that can contribute significantly to various domains, including academic research and the arts.

Bal, Wilkinson, and Fok (Citation2022) provide insight into the cognitive profiles of autistic children, revealing instances of extraordinary talents, particularly in memory and pattern recognition. Urbanowicz et al. (Citation2019) discusses strengths-based approaches in autism, advocating for a focus on the abilities and potentials of autistic individuals, which often go unnoticed in traditional deficit-focused narratives. Courchesne et al. (Citation2015) highlighted that due to deficit focused approaches, autistic children are at risk of being underestimated in a range of settings, including at school. Autistic strengths, as Warren, Buckingham, and Parsons (Citation2021) suggest, are not just limited to cognitive abilities but also include unique personal and interpersonal attributes, as identified by parents of autistic youth (Clark & Adams, Citation2020). This growing body of research collectively emphasizes the importance of recognizing and nurturing the distinctive strengths of autistic individuals, moving beyond the deficits to appreciate their abilities and contributions (Bal, Wilkinson, and Fok Citation2022; Russell et al. Citation2019; Urbanowicz et al. Citation2019; Warren et al. Citation2020).

However, autistic individuals may face a range of challenges, particularly in social communication and sensory processing. Social interaction can be challenging due to differences in understanding social cues, body language, and the subtleties of conversation. Warren et al. (Citation2020) highlight that parents of autistic youth often identify social communication as an area of difficulty for their children. Sensory sensitivities are also common, with many autistic individuals experiencing over- or under-sensitivity to sensory inputs like light, sound, and texture, which can impact their daily functioning and comfort levels (Clark & Adams, Citation2020; Giarelli, Ruttenberg, and Segal Citation2013; Ryan Citation2010). Additionally, adapting to new or unfamiliar situations can be challenging, as many autistic individuals can prefer routine and consistency (Clark & Adams, Citation2020).

‘Executive functioning’ in autistic individuals can be complex, involving both strengths and challenges. A comprehensive review (St John et al. Citation2022) focusing on executive functioning challenges and strengths in autistic adults reveals that while some individuals may experience difficulties in areas such as flexibility, planning, and inhibition, others may exhibit strengths in systematic processing and consistency in routines.

The combination of these strengths and challenges underscores the importance of a balanced approach in understanding and supporting autistic individuals. Recognizing and nurturing their unique abilities, while also providing support, is crucial. This approach not only facilitates autistic people’s development and well-being but also enables their contributions to society to be appreciated and valued (Russell et al. Citation2019; Urbanowicz et al. Citation2019; Warren et al. Citation2020).

Environmental barriers and intersectional considerations

Seeking autistic perspectives in research is important to better understand the impact of various environmental influences – the physical, social and attitudinal on this group (Anaby et al. Citation2013, Citation2014; Forsyth et al. Citation2007; King, Rigby, and Batorowicz Citation2013; Trew et al., Citation2023). Areas of environmental impact include the familial, parental, or peer environments (Henninger and Taylor Citation2013; Orsmond et al. Citation2006) including experiences of being misunderstood by non-autistic others such as family members; physical environment factors like space and sensory inputs (Giarelli, Ruttenberg, and Segal Citation2013; Ryan Citation2010); and school and community environments, including experiences of bullying, and exclusion from social support and public services (Hasson et al. Citation2024; Hebron and Bond Citation2017; Liptak, Kennedy, and Dosa Citation2011; Myers et al. Citation2015; Trew Citation2024).

The phenomenon of stigma as experienced by autistic individuals and their families has not been extensively researched (Alshaigi et al. Citation2020; Grinker Citation2020; Liao, Lei, and Li Citation2019; Ng and Ng Citation2022; Turnock, Langley, and Jones Citation2022), even though it’s evident that stigma about autism contributes negatively to various life aspects and affects the overall well-being of autistic people (Botha, Dibb, and Frost Citation2020; Farsinejad, Russell, and Butler Citation2022; Grinker Citation2020; Leadbitter et al. Citation2021; Turnock, Langley, and Jones Citation2022).

These kinds of challenges and barriers have long-term implications for autistic adult outcomes, with some research suggesting that early supports for younger autistic people that lead to greater participation and inclusion in childhood and adolescence could lead to improved adult participation outcomes across several domains including employment and social relationships (Cameron et al. Citation2022; Chan, Doran, and Galobardi Citation2023; Eaves and Ho Citation2008; Egilson et al. Citation2016; Farley et al. Citation2009; Henninger and Taylor Citation2013; Howlin et al. Citation2004; Lawrence, Alleckson, and Bjorklund Citation2010; Mason et al. Citation2021; Turcotte et al. Citation2015).

Incorporating autistic perspectives through qualitative research

Incorporating autistic perspectives through qualitative research is vital for a deeper understanding of autism (Russell et al. Citation2019; Urbanowicz et al. Citation2019) and important for leveraging firsthand accounts and narratives of the multifaceted nature of the autistic experience and the barriers to autistic participation in a range of settings and environments (Kelly et al. Citation2022). Research methodologies that move beyond deficit-focused narratives allow for the exploration of autistic strengths, preferences, and unique perspectives. This approach contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of autism and promotes a dialogue that respects and values the autistic community (Russell et al. Citation2019).

Grant and Kara (Citation2021) highlight how autistic researchers can contribute unique insights and perspectives, enriching the understanding of autism. They discuss how autistic researchers can contribute significantly to the field, offering perspectives that might otherwise be overlooked. Their attention to detail, depth in focus on specific topics, and ability to think in unconventional ways can enrich the research process and outcomes. By centring autistic voices and experiences, researchers can develop more effective, respectful, and person-centered approaches to supporting autistic individuals (Grant and Kara Citation2021; Russell et al. Citation2019).

This notable shift towards strengths-based methodologies is evident in clinical practices, such as autism diagnostic assessments, where a focus on the strengths, skills, and interests of individuals is increasingly recommended (Whitehouse et al. Citation2018; Woods & Estes, Citation2023). Research in this area is expanding, exploring the impact of strength-based language in diagnostic reports (Braun, Dunn, and Tomchek Citation2017), the application of strengths-based supports for young autistic adults transitioning from school (Hatfield et al. Citation2018; White et al. Citation2024), and the development of new models for aging well for older autistic people (Hwang, Foley, and Trollor Citation2020).

Perspectives and experiences of younger autistic people in qualitative research

Authors Depape and Lindsay (Citation2016) have recognised in their meta-analysis that first-person narratives from autistic children and adolescents are scarce in the literature. The authors identified for inclusion in their review a total of 33 studies across a period of three decades that investigated lived experiences from the perspective of autistic people. Depape and Lindsay (Citation2016) concluded that most lived experience research focused on adults (Hurlbutt and Chalmers Citation2002; Müller, Schuler, and Yates Citation2008; Punshon, Skirrow, and Murphy Citation2009), and only a small number of studies included children or adolescents (Huws and Jones Citation2008; Marks et al. Citation2000; Penney Citation2013; Preece and Jordan Citation2010; Saggers, Hwang, and Mercer Citation2011; Zukauskas, Silton, and Baptista Citation2009).

Knowledge of first-person experiences and perceptions of autistic children and adolescents is largely limited to the challenges they experience in school, including establishing friendships with peers and their experiences of being bullied and excluded and poor wellbeing at school (Calzada, Pistrang, and William Citation2011; Cappadocia, Weiss, and Pepler Citation2012; Chen and Schwartz Citation2012; Connor Citation2000; Cunningham Citation2020; Fisher and Taylor Citation2016; Goodall and MacKenzie Citation2019; Hill et al. Citation2016; Hill Citation2014; Marks et al. Citation2000; Preece and Jordan Citation2010; Saggers, Hwang, and Mercer Citation2011; Warren, Buckingham, and Parsons Citation2021). Since the publication of DePape and Lindsay’s (Citation2016) qualitative meta-synthesis, there have been limited studies that have captured the voices of autistic children and adolescents. Some other authors (e.g. Clark & Adams, Citation2020; Kirby, Dickie, and Baranek Citation2014 Pellicano et al. Citation2018; Saggers, Hwang, and Mercer Citation2011; Scott-Barrett, Cebula, and Florian Citation2019) have highlighted that few scholars have recognised the crucial need to research the perspectives of autistic children and adolescents.

For example, in a recent study Courchesne et al. (Citation2022) sought to test and develop strategies that may prove potentially effective in capturing the voices of autistic teenagers and creating inclusive methodologies within disability and autism research. A few studies (Cappadocia, Weiss, and Pepler Citation2012; Chen and Schwartz Citation2012; Fisher and Taylor Citation2016) interviewed autistic adolescents about their experiences of peer victimisation including bullying and teasing and put forward recommendations that schools might use to address this issue. One study (Kirby, Dickie, and Baranek Citation2014) using phenomenological interviews explored how autistic children and adolescents between 4 and 14 years of age share information about their sensory experiences. The findings showed that these children and adolescents share information about their sensory experiences through themes of normalising, storytelling, and describing responses. Another study (O’Hagan et al. Citation2022) included autistic mentees ages 14–21 amongst a larger study sample in focus groups to understand their perspectives of an inclusive peer mentoring program (Teens Engaged as Mentors) for autistic adolescents. The findings showed that autistic mentees enjoyed the mentoring program because of increased socialisation opportunities, which promoted friendships and openness towards others. Another study (Jones et al. Citation2015) using construct narrative analysis from interviews with autistic adolescents highlight societal attitudes, including stigma and the language surrounding autism, significantly influenced how autistic adolescents perceive themselves and interpret their diagnosis. This understanding underscores the importance of societal perspectives and communication about autism in shaping the self-concept of autistic adolescents.

Despite this body of research, efforts to engage autistic adolescents in research remain uncommon (Factor et al. Citation2019). It is important to investigate the younger autistic perspective as research shows the challenges faced by these younger groups in various environments and the barriers to social inclusion and participation, including in education and healthcare (Anderson and Butt Citation2018; Bradshaw et al. Citation2021; Buckley et al. Citation2020; Goodall Citation2018). For example, younger autistic people’s reduced participation in social interactions and mainstream schooling challenges (Bailey & Baker Citation2020; Giarelli, Ruttenberg, and Segal Citation2013) including bullying and social anxiety (Eroglu and Kilic Citation2020; Jackson, Keville, and Ludlow Citation2022; Kuusikko et al. Citation2008); isolation (Locke et al. Citation2010) and limited peer relationships and low peer acceptance (Cameron et al. Citation2022; Sari et al. Citation2021); and low participation in leisure, educational, and community activities (Arnell et al. Citation2020; Egilson et al. Citation2016).

Research process

Methodology and methods

This study is guided by a social constructivist approach. The study utilises a qualitative methodology and naturalistic narrative approach to the research design (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). With a focus on context and subjectivity, the approach emphasizes understanding phenomena within its specific contexts and values the perspectives and experiences of individuals, focusing on narratives, meanings, and interpretations. Studies focused on narratives seeks to comprehend human experience or the story-like interpretation of a specific event or phenomenon (Josselson Citation2010; Ntinda Citation2019). This narrative perspective looks at understanding how individuals interpret their experiences, narrating them in their own language and context (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). Employing a narrative approach in research, particularly a naturalistic descriptive one, offers an opportunity for underrepresented groups to express their perspectives and experiences (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985; Padgett Citation2008).

In this study, I supported the need to adapt research methods in response to autistic adolescents for their continued involvement in the research (Bergold Citation2007; Coburn and Gormally Citation2015; Levy and Thompson Citation2015). This meant that the methods used emerged through discussion with participants, with a particular focus on appropriate adaptation and flexibility to suit autistic adolescents (Bergold Citation2007; Crotty Citation1998; O’Kane Citation2008). This allowed the research to explore autistic social phenomena in-depth whilst accommodating the preferences and insights of the autistic participants. This study uses encouragers and open-ended questions to engage the participants in the research and to generate rich data for storytelling from their shared and distinct experiences (O’Reilly and Dogra Citation2017; Ponizovsky-Bergelson et al. Citation2019).

Participants

Eleven autistic adolescents 12–19 years of age were recruited for this study. Participants were 4 females, 6 males, and 1 non-binary individual. Most participants, 9 in total, were Australian, while 2 participants were Sri-Lankan. The sampling was designed around recruiting adolescents through families to reach and work with individual members. The project’s recruitment approach focused on establishing strong connections with autism support services, schools, and disability support organisations for youth and families in Canberra. To engage participants, the research opportunity was promoted through newsletters and bulletins issued by these institutions.

Purposeful sampling was employed to recruit participants who were autistic and for identifying possible information-rich cases connected to the research (Palinkas et al. Citation2015). The criteria for participation in this study were that the adolescents had lived experiences of autism, were willing to discuss and to understand the nature and meaning of autism, or the ‘what it is like’ being an autistic person and were agreeable to participating in one in-depth semi-structured interview. Given that the primary purpose of in-depth interviews is to gain a deeper understanding of the meaning behind the behaviour, the sample size in this study is considered appropriate for appreciating the experiences, views, and perceptions of participants (Rosenthal Citation2016).

Ethics approval and participant consent

The Australian Catholic University’s National Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) granted approval for this study, which is registered under study number 2019-33H. Consent in this study was an ongoing process that was negotiated and renegotiated. Participants were provided with multiple opportunities to reaffirm or withdraw their consent to participant in the interviews. Participants were provided with information about this study and led through a tick box consent process that ensured that they understood the nature and scope of this study and their involvement within it and the ways that they could consent or choose how to participate throughout the research process. Parental consent was also required for adolescents under the age of 18 who wanted to be interviewed. Participants were provided with an online monetary voucher for their time and involvement in this study.

Data collected for analysis

The primary source of data for analysis was collected from the interviews. Data included information gathered from in-depth semi-structured interviews using an interview guide and conducted in person with the participants. Examples of questions asked of participants were: In what ways do you identify with the term autistic or autism? What does autism or being autistic mean to you? In what ways does autism or being autistic make you unique or distinct? Do you see being autistic or autism as being different to others or not? In all interviews, prompts were used to explore participants’ experiences in greater depth, and questions were formulated to enquire into their identity, their relationship with the self and others, and interactions with the self and others. Open-ended questions encouraged participants to share their experiences and stories, captured in their own words. Interviews ranged from 30 to 80 min. The interviews utilized an interview guide with associated visual aids, reflective notes, audio recordings, memos, and field notes. Memos and field notes written in a research diary as well as verbal recordings after interviews with participants helped document any observable bias (Morgan Citation2008; Shaw and Holland Citation2014; van Manen Citation1990).

Member checking

Member checking ensured the interview transcripts were correct and valid (Moustakas, Citation1994). After the interviews were completed, all participants in the research were sent a copy of their interview transcript and were invited to check it for accuracy to confirm and add credibility (Creswell and Poth Citation2018). Feedback was collected from most autistic adolescents. This step occurred again throughout data analysis. Third, participants were then given a copy of the initial construction of themes and provided feedback.

Data analysis

In this study, the aim was to generate thick descriptions for an in-depth understanding of how the study participants made sense of and experienced autism. The term thick description refers to a focused and detailed account of participants’ lived experiences, events, or situations (Denzin, Citation1989). To acquire an understanding of the meaning of the perceptions and experiences of autistic adolescents, an approach to data analysis consistent with a narrative strategy of balancing storied experience through both objective and subjective approaches to knowledge production was required (Creswell and Poth Citation2018). To achieve this, this study employed constructivist grounded theory analysis including concepts, processes, and techniques to arrive at findings which are presented as themes from a thematic construction of the data (Charmaz Citation2014). Illustration of the global theme from thematic analysis (TA) was aided by thematic networks (Attride-Stirling Citation2001). TA, with the aid of thematic networks (Attride-Stirling Citation2001, 386): ‘…web-like illustrations (networks) that summarize the main themes constituting a piece of text’, was the primary tool applied to the analysis of the data.

Findings

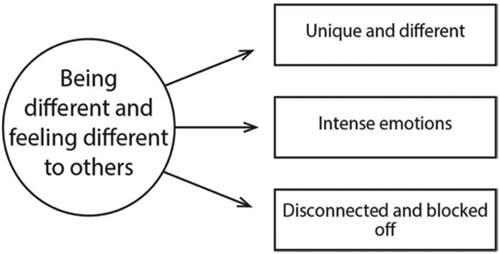

The findings are organised around one global theme and offer an insider account of being an autistic adolescent. The autistic adolescents’ insights and experiences are presented in detail using illustrative quotations via pseudonyms throughout the global theme Being different and feeling different to others.

Global theme: being different and feeling different to others

Most autistic adolescents have an awareness of feeling different and being different to others who are not autistic. For the autistic adolescents, autism or being autistic, is perceived by the group as a way of being and doing – acting, thinking, feeling, communicating; a skill or ability or something special; and a part of who they are as a person. Adolescents’ experiences are reflected in the accounts of their interactions with others, including peers and family members. For some adolescents, feeling different is described as a disconnect from others and being in their own world. Most adolescents attributed their intense anger, stress, and anxiety to autism, and most reported times they were not in control of their behaviours. However, for most autistic adolescents, autism was also experienced as an energy and focus and drive, with a strong sense of self. Just one autistic adolescent shared that although they identified as being ‘autistic,’ they still felt the same as other people who were not autistic. illustrates organising themes that were constructed within this global theme. These organising themes are presented and supported with participant quotes.

Unique and different

Each participant had their own understanding and definition of autism. Jim remarked, ‘I know what autism is, but it’s our own definition. It’s different for everyone…some people with autism [can] tend to act funny, or erratic, or something that people wouldn’t deem as usual.’ Rory, shared:

Rory: You’ve got ceiling fan people, train timetable people, washing machine and car wash people, people that are absolutely focused religiously on something that may seem boring, but they are completely in love with it. I get that about a lot of stuff…a spectrum love for things… My passions and my interests give me all my energy, all the things I need, all the sense of purpose.

Many adolescents, such as Nina, wanted others to know that ‘if someone’s on the spectrum, they’re all different and special in their own way…all people on the spectrum aren’t the same.’ Some adolescents described ‘being on the spectrum’ as a different way of acting, thinking, feeling, and communicating. Ken explained that ‘autism just means I think differently. I act differently, some things I do can be different…sometimes I have different ideas…I think that’s what makes me, and us, different…I think it [autism] plays a positive role.’ Feeling different was a shared experience reported by most autistic adolescents. Lance understood autism to be a behaviour and explained why he felt different:

Lance: I do feel different. I have different problems. I have different struggles. It’s not that autism is in your control, but I think behaviour to some extent can be adapted. I feel like it’s [autism] something that can be worked around.

Autistic adolescents’ sense of feeling different was influenced by those around them who were not autistic. Rory recalled he first noticed this difference in primary school: ‘I began to realise that I was different and strange and that the way that I behaved was very different to the rules of the other kids around me.’ Ken shared that despite feeling different to others, he considered this a positive characteristic of having autism: ‘I feel different. I’m actually proud that I’m different. I like it. I don’t want to be a member of the flock; I want to be my own person.’

Many adolescents’ understandings of autism were influenced by their parents’ descriptions of autism. Jim recalled: ‘I remember reading that autism means selfishness. I asked Mum if I come across as selfish and we had a talk about how sometimes it’s a bit ‘My way or the highway’ approach.’ When discussing the anxiety and stress they experience, Joanna recalled: ‘One thing mum said once, autism is a heightened form of anxiety because there’s some sort of obsessive-compulsive disorder that comes with it, having to double check a lot of things…sometimes my brain goes silly and gets angry at me, and then after trying to calm down, I walk through and fix it.’

Most autistic adolescents felt so different to others that it reduced their sense of belonging. Lucy explained: ‘I think that I am different, but I feel like I’m really different’. I don’t really feel like I belong.’ For Lance, being different to others who were not autistic was something that used to affect him. Over time, Lance embraced his difference and dealt with his difficulties: ‘I do recognise and these days I do embrace my difference. I used to be self-conscious about it. I used to be upset about being different.’

Intense emotions

Emotions played a significant role in the lives of all autistic adolescents. Adolescents described the intensity of their emotional, social, and physical experiences resulting from autism. Because of autism, most adolescents could not spend lengthy amounts of time with others. Nina explained: ‘After a while I find people a bit draining. I have to get away. It’s not that I don’t like the person, it’s just that I need breaks to be on my own.’

Many adolescents described the different ways that autism could make them act differently to others. Jim explained: ‘It can make you physically different in the way you act, and emotionally different, so you can become a lot more trusting of people, and you might have a lessened sense of judgement.’. Lance shared of his ‘emotional reliance’ on his father:

Lance: I want to develop a form of emotional self-reliance, not depending on other people’s behaviours to affect my emotions. For me that’s become a very important thing, not depending on my dad looking happy for me to feel happy. To control that within myself and learn to relax.

Lucy: autism is something that holds me back. Emotionally, sometimes physically and socially. Sometimes I’ll say something and then I’ll be like, ‘I should not have said that.’ Sometimes I feel like I can’t do something because I’m on the spectrum. I’d say that it’s a way that perhaps autism makes me feel different from someone that doesn’t have autism.

Lance: I find it difficult to read my parents’ emotions. Ever since I’ve been a little kid, I’ve said, my parents are grumpy and talk in a kind of strange, stressed way. I feel this kind of oppressive, stressed presence, but that feeling is in me. I don’t really know what they’re thinking or feeling, and that has caused a lot of strain and difficulty in the relationship.

Joanne: I’m very highly empathetic…Connecting with the world includes connecting with other people’s emotions. It’s especially helpful when I need to deal with [my brother] because he’s highly emotional…When my little brother is grumpy. I can get grumpy as well. It’s kind of like emotion mirroring.

We sometimes find it challenging to talk to each other in a nice way. Sometimes you want to be alone and someone else wants to do something, and you get angry about it, then we get angry at each other. Everyone in our house has Asperger’s, so we all know it’s going to happen. It’s hard on relationships having one Asperger in the house, let alone four. One thing we can do to help each other with our Asperger’s is listen to each other. We try to listen, but we can get so upset.

Ken: I can get really angry. I go from zero to Hulk mode in a few seconds. I try not to get angry. It’s so hard, trying to figure out why. I can get angry about some little things like [my sister or a friend] asking me something when I’m focusing on something, and just getting infuriated.

Lucy: My sister and I have our fights. More often than I prefer. Mainly started by me, but sometimes I start them for no reason. I don’t know why I start them because I know I don’t want to fight … I’ve just let the lion out of the cage, I can’t do anything about that now, let’s just let it run free. It’s difficult to keep the lion in the cage.

Nina: Sometimes I won’t put things in the best way. I have a tendency to not really talk but, to lash out, and that’s not the best way.’

Disconnected and blocked off

Nearly all adolescents described feeling disconnected from others. For Joanne, this included not knowing ‘unwritten social rules’ and how to follow them: ‘I’m not very socially good. I’m pretty sure there are a few unwritten rules out there that I still have no idea what they are and how on earth to follow them.’ Nina, as well, described not understanding these kinds of rules: ‘I do think that this world is still a puzzle to me, like how people act and how rules are… and for my world it’s easy to go there and understand it because it’s my world.’

Most adolescents found it difficult to relate to or connect with their others. Lance explained that being autistic creates a disconnect between himself and his parents:

Lance: There is a sense of control and understanding and rapport that is vastly reduced. It affected the family dynamic in that you have a very detached kid who wants to follow his own interests. There was a disconnect, but also there was a lack of will on my part to make a connection. I didn’t see any purpose in that. It did mean that I had a quite strange relationship with my parents… I needed my parents around me because I needed attention and somebody to look after me and I didn’t want to be on my own.

Lucy: He (dad) doesn’t understand me, so I don’t like to see him very often. I’d like him to contact me and want to talk to me, and want to invite me over to his place, to hang out and spend time together.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore alongside autistic adolescents their perspectives and experiences of autism. The study identified that for the participants there was not an exact or definitive description or definition of autism available that captured and explained all its characteristics. The findings of this study suggest a rich and nuanced understanding and description of autism for these adolescents. Autistic adolescents placed great emphasis on difference and diversity, rather than difficulty, as they highlight their strengths and the positive elements of autism and characteristics that manifest in themselves. For most participants, autism was an intrinsic part of what made them to be their own unique person and not necessarily a disorder or a condition that they had acquired.

For the participants, autism is a part of a person, something inherent, and can be a special and unique ability. It is a way of existing in two worlds, one being the autistic persons, and one being shared with others. It is a way of being and doing and influences how one thinks, acts, feels and communicates, often different from others around them. Autism can enhance a person and can block a person off. This can mean feeling stress and anxiety, anger and not in control of emotions and physical actions. It can also mean a driving energetic force, a strong focus and intense interest in one or many things.

These findings have important implications for strengths use in autism. In recent research, authors Taylor et al. (Citation2023) found that autistic individuals often demonstrate a lesser awareness and application of their strengths. Despite this, they observed that the utilization of strengths in autistic people is closely linked to enhanced life quality, improved subjective well-being, and reduced instances of anxiety, depression, and stress. Consequently, strategies and practices that emphasize the development and use of strengths could be an effective way to improve overall well-being in autistic individuals.

Additionally, the participants in this study expressed awareness of their uniqueness, with some viewing this autistic difference as a special aspect of their identity. This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating that autistic adults often perceive themselves as distinct from non-autistic peers (Botha, Dibb, and Frost Citation2020; Hurlbutt and Chalmers Citation2002). This difference was reported by the autistic adolescents in this study to manifest in various ways, including communication, thinking, and behaviour. For example, intense emotions, particularly anger played a significant role in the lives of autistic adolescents. Anger, being contextual and therefore is not inevitable, often led to conflicts between family members, and some participants recognised the impact their anger had on themselves and others. This finding supports previous research that reported anger and aggression in autistic individuals (Mazefsky et al. Citation2013) and that stress, anxiety, depression (Mattys Citation2018) and irritability (Mervielde et al. Citation2005; Sizoo, van der Gaag, and van den Brink Citation2015) are common traits observed in autistic individuals.

Moreover, this study highlights that the sense of feeling different was influenced by interactions with non-autistic others. In this study, parents played a role in shaping the understanding of autism for some adolescents. Their descriptions of autism impacted how these individuals perceived themselves and their experiences. Parental influence on self-perception has been documented, with a study by Cridland et al. (Citation2014) indicating that parental attitudes can impact self-esteem and self-identity in autistic individuals. However, parents are also identified as an important source of information about autistic children and adolescents’ strengths and abilities (Trew Citation2024; Warren, Buckingham, and Parsons Citation2021). Supporting caregivers and others to observe, identify, communicate and interact with autistic adolescents from a strengths approach to autism is important to shape a positive perception and understanding of autism for the young person and their sense of self and identity construction. In another study, Jones et al. (Citation2015) found that for autistic adolescents, their interactions with peers, family members, and others in their community are pivotal in shaping their perceptions of their diagnosis and their self-identity. These interactions often lead to mixed emotions about their condition. While they value the unique characteristics that come with autism, they continued to face challenges in their social relationships.

Social identity theory and its processes (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979) offer a potentially useful lens through which to understand how the participants perceives themselves in the context of autism, and how this perception can affect connectedness with others, including family and social and community connectedness (Lee and Robbins Citation1998; Manzi and Brambilla Citation2014; Tomison and Wise Citation1999). Most autistic adolescents in this study described feeling disconnected, emotionally and physically from others. Connecting and a sense of belonging in interpersonal relationships and in wider social groups is a central human need (Greer, Yu, and Bunderson Citation2015). The basis of connectedness is ‘…positive relationships and experiences with others, and more specifically, relationships and experiences from which [children and] youth garner esteem and competence’ (Karcher, Holcomb, and Zambrano Citation2008, 9).

A strong sense of affiliation with members in a group may possibly improve psychological wellbeing, as demonstrated through a reduction in depression and anxiety scores in autistic adults (Cage, Di Monaco, and Newell Citation2018; Cooper, Smith, and Russell Citation2017). Improving autistic adolescents’ social participant is important as generalised anxiety, separation anxiety, and social anxiety are commonly reported amongst autistic people, with an estimated 40% prevalence rate (Keen et al. Citation2019; Ozsivadjian et al. Citation2012; Spiker et al. Citation2011; Steensel, Bögels, and Perrin Citation2011; Wood and Gadow Citation2010) and are the most frequently reported mental health difficulties amongst this group (Magiati et al. Citation2015).

In this study, autistic adolescents’ sense of disconnect was linked to difficulties in understanding unwritten social rules and connecting with others. However, some adolescents found it frustrating that others such as their family members did not understand them. These findings are consistent with the ‘double empathy problem’ theory (Milton Citation2012), suggesting that it is not just autistic people who can misunderstand others, but they can be misunderstood by non-autistic others, leading to a bidirectional failure of empathy (Heasman and Gillespie Citation2017; Mitchell, Sheppard, and Cassidy Citation2021). Further, the study findings indicated that participants experience a sense of social and emotional disconnectedness in the relationship with their parents despite a strong desire and need to connect with them. Supports might be put in place to address emotional distancing and physical withdrawal between autistic adolescents and others, including family members through a facilitated discussion about the behaviours and patterns that contribute to ambiguous relationships, unclear communications, and stresses (Trew, Citation2024). Practitioners with the required knowledge and skills, and who remain alert to the behaviours, pattens, and responses, might be able to use the construct of ambiguous loss (Boss Citation1977, Citation1999, Citation2006) to guide therapeutic discussion and to support the identification of strategies to promote adaptive patterns, such as conflict resolution, problem solving, and the coping ability for autistic adolescents and family members (Varghese, Kirpekar, and Loganathan Citation2020).

This study indicates that some autistic adolescents cope by withdrawing socially and emotionally from their family to spend time in their own worlds created from their imagination. Some other autistic adolescents cope by redirecting their focus on a particular interest. In the literature, coping is defined as ‘…reflective thinking, feeling, or acting so as to preserve a satisfied psychological state when it is threatened’ (Snyder Citation2001, 4). Social isolation, withdrawing, and avoidance behaviour are established in the literature as maladaptive coping strategies (Spirito and Donaldson Citation1998). These behaviours are precursors to disconnectedness, characterised by social isolation and reduced or absent personal and intra-community relationships (Elliot Citation2006).

Practitioners might utilise cognitive restructuring (Gladding Citation2009) as an adaptive coping strategy, which involves an individual learning to identify and challenge irrational or maladaptive thoughts to change negative thinking pattens. This cognitive-based therapy can be implemented with groups, including families in which members are using avoidant actions or strategies (Rodriguez and Thompson Citation2015), such as social isolation from the family or emotional withdrawal. The study findings indicated that these types of avoidant strategies and actions were used by autistic adolescents in response to behaviours, miscommunications, or a general lack of bidirectional relatedness. Practitioners might encourage other adaptive coping strategies such as approach or action strategies, problem-focused strategies, and cognitive and meaning-making strategies (Meadan, Stoner, and Angell Citation2009; Marshall and Long Citation2009; Mount and Dillon Citation2014). This could help individuals develop the skills to respond to and manage stressors in a way that does not reinforce the kinds of patterns and behaviours that contribute to disrupted connections.

This study also indicates, through the insights of the autistic participants, that strong and close relationships can be created by spending one-on-one time with others who provide reassurance, support, attention, and care. It is established in the literature that factors such as these contribute towards secure connections between individuals, ‘…when a person is actively involved with another person, and that involvement promotes a sense of comfort, well-being and anxiety reduction’ (Hagerty et al. Citation1993, 293).

Limitations and contributions

One noteworthy limitation of this study is it reflects a singular and specific point in time amongst a relatively small group of participants drawn from a single geographic area. This means the research is not generalisable outside the specific scope of this study. Another limitation is that single interviews may not generate rich descriptions for meaningful findings (Polkinghorne Citation2005), and for a few participants their interviews were short.

This qualitative study has expanded the knowledge concerning how autistic adolescents perceive and experience autism. This study not only provides a platform to autistic adolescent’s experiences but foregrounds their insights with existent theory and practice to provide suggestions for a strengths use of autism when working with this group in developing mental health and wellbeing practices and support strategies. The findings encourage others including parents/caregivers and professionals to consider autism in relation to adolescents’ strengths and abilities, and work with them in these ways. This offers the potential to improve upon the wellbeing and mental health of autistic adolescents.

Conclusion

This study illustrated the views and narratives of autistic adolescents, challenging us to rethink conventional perceptions of autism. By accepting autism not just as a condition but as a distinct way of being, we can better appreciate the richness of diversity in human experiences. These autistic adolescents show us that understanding autism through their experiences can unlock a deeper, more empathetic approach to engagement and support.

The findings underscore the role of familial and social interactions in shaping these autistic adolescents’ perceptions of autism, pointing to the complex dynamics of empathy, misunderstanding, and emotional connection within these relationships. Autistic adolescents often experience a heightened sense of difference that is not only self-acknowledged but also moulded by the perceptions and reactions of those around them, particularly non-autistic peers, and family members.

To further consolidate the impact of these findings, future research should focus on comparative studies that explore autistic adolescents’ experiences across different cultural and socio-economic contexts to enhance the understandings of these insights. Additionally, longitudinal studies examining the long-term outcomes of strength-based approaches in supporting autistic individuals would be valuable.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Australian Catholic University (ACU) National Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC), study registration number 2019-33H. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolment in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alshaigi, K., R. Albraheem, K. Alsaleem, M. Zakaria, A. Jobeir, and H. Aldhalaan. 2020. “Stigmatization among Parents of Autism Spectrum Disorder Children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.” International Journal of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 7 (3): 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpam.2019.06.003.

- Anaby, D., C. Hand, L. Bradley, B. DiRezze, M. Forhan, A. DiGiacomo, and M. Law. 2013. “The Effect of the Environment on Participation of Children and Youth with Disabilities: A Scoping Review.” Disability and Rehabilitation 35 (19): 1589–1598. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.748840.

- Anaby, D., M. Law, W. Coster, G. Bedell, M. Khetani, L. Avery, and R. Teplicky. 2014. “The Mediating Role of the Environment in Explaining Participation of Children and Youth with and without Disabilities across Home, School, and Community.” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 95 (5): 908–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2014.01.005.

- Anderson, C., and C. Butt. 2018. “Young Adults on the Autism Spectrum: The Struggle for Appropriate Services.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 48 (11): 3912–3925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3673-z.

- Arnell, S., K. Jerlinder, and L.-O. Lundqvist. 2020. “Parents’ Perceptions and Concerns about Physical Activity Participation among Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice 24 (8): 2243–2255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320942092.

- Attride-Stirling, J. 2001. “Thematic Networks: An Analytic Tool for Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Research 1 (3): 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307.

- Bailey, J., and S. T. Baker. 2020. “A Synthesis of the Quantitative Literature on Autistic Pupils’ Experience of Barriers to Inclusion in Mainstream Schools.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 20 (4): 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12490.

- Bal, V. H., E. Wilkinson, and M. Fok. 2022. “Cognitive Profiles of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder With Parent-Reported Extraordinary Talents and Personal Strengths.” Autism 26 (1): 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211020618.

- Bergold, J. 2007. “Participatory Strategies in Community Psychology Research—A Short Survey.” In Poland welcomes community psychology: Proceedings from the 6th European Conference on Community Psychology, edited by A. Bokszczanin (pp. 57–66). Opole: Opole University Press.

- Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H., M. Kourti, D. Jackson-Perry, C. Brownlow, K. Fletcher, D. Bendelman, and L. O’Dell. 2019. “Doing It Differently: Emancipatory Autism Studies Within a Neurodiverse Academic Space.” Disability & Society 34 (7-8): 1082–1101. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1603102.

- Boss, P. 1977. “A Clarification of the Concept of Psychological Father Presence in Families Experiencing Ambiguity of Boundary.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 39 (1): 141–151. https://doi.org/10.2307/351070.

- Boss, P. 1999. Ambiguous loss: Learning to live with unresolved grief. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Boss, P. 2006. Loss, Trauma, and Resilience: Therapeutic Work with Ambiguous Loss. W Norton & Co.

- Botha, M., B. Dibb, and D. M. Frost. 2020. “Autism is Me”: An Investigation of How Autistic Individuals Make Sense of Autism and Stigma.” Disability & Society 37 (3): 427–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1822782.

- Bradshaw, P., C. Pickett, L. M. van Driel, K. Brooker, and A. Urbanowicz. 2021. “Recognising, Supporting and Understanding Autistic Adults in General Practice Settings.” Australian Journal of General Practice 50 (3): 126–130. https://doi.org/10.31128/AJGP-11-20-5722.

- Braun, M. J., W. Dunn, and S. D. Tomchek. 2017. “A Pilot Study on Professional Documentation: Do We Write From a Strengths Perspective?” American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 26 (3): 972–981. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_AJSLP-16-0117.

- Brown, H. M., A. C. Stahmer, P. Dwyer, and S. Rivera. 2021. “Changing the Story: How Diagnosticians Can Support a Neurodiversity Perspective from the Start.” Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice 25 (5): 1171–1174. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211001012.

- Buckley, J., J. K. Luiselli, J. M. Harper, and A. Shlesinger. 2020. “Teaching Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder to Tolerate Haircutting.” Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 53 (4): 2081–2089. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.713.

- Buntinx, W. H. E., and R. L. Schalock. 2010. “Models of Disability, Quality of Life, and Individualized Supports: Implications for Professional Practice in Intellectual Disability.” Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 7 (4): 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2010.00278.x.

- Cage, E., J. Di Monaco, and V. Newell. 2018. “Experiences of Autism Acceptance and Mental Health in Autistic Adults.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 48 (2): 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3342-7.

- Calzada, L., N. Pistrang, and M. William. 2011. “High-Functioning Autism and Asperger’s Disorder: Utility and Meaning for Families.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 42 (2): 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1238-5.

- Cameron, L. A., B. J. Tonge, P. Howlin, S. L. Einfeld, R. J. Stancliffe, and K. M. Gray. 2022. “Social and Community Inclusion Outcomes for Adults with Autism with and without Intellectual Disability in Australia.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 66 (7): 655–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12953.

- Cappadocia, M. C., J. A. Weiss, and D. Pepler. 2012. “Bullying Experiences among Children and Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 42 (2): 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1241-x.

- Cascio, M. A., J. A. Weiss, and E. Racine. 2020. “Empowerment in Decision-Making for Autistic People in Research.” Disability & Society 36 (1): 100–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1712189.

- Chan, D. V., J. D. Doran, and O. D. Galobardi. 2023. “Beyond Friendship: The Spectrum of Social Participation of Autistic Adults.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 53 (1): 424–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05441-1.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Chen, P. Y., and I. S. Schwartz. 2012. “Bullying and Victimization Experiences of Students With Autism Spectrum Disorders in Elementary Schools.” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 27 (4): 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357612459556.

- Chown, N., J. Robinson, L. Beardon, J. Downing, L. Hughes, J. Leatherland, K. Fox, L. Hickman, and D. MacGregor. 2017. “Improving Research about us, with us: A Draft Framework for Inclusive Autism Research.” Disability & Society 32 (5): 720–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1320273.

- Clark, M., and D. Adams. 2020. “Parent-Reported Barriers and Enablers of Strengths in Their Children with Autism.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 29 (9): 2402–2415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01741-1.

- Coburn, A., and S. Gormally. 2015. “Emancipatory Praxis—A Social Justice Approach to Equality Work.” In Socially-Just, Radical Alternatives for Education and Youth Work Practice: Re-Imagining Ways of Working with Adolescents, edited by C. Cooper, S. Gormally, & G. Hughes. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Connor, M. 2000. “Asperger Syndrome (Autistic Spectrum Disorder) and the Self-Reports of Comprehensive School Students.” Educational Psychology in Practice 16 (3): 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/713666079.

- Cooper, K., L. G. E. Smith, and A. Russell. 2017. “Social Identity, Self-Esteem, and Mental Health in Autism.” European Journal of Social Psychology 47 (7): 844–854. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2297.

- Courchesne, V., A.-A. S. Meilleur, M.-P. Poulin-Lord, M. Dawson, and I. Soulières. 2015. “Autistic Children at Risk of Being Underestimated: School-Based Pilot Study of a Strength-Informed Assessment.” Molecular Autism 6 (1): 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-015-0006-3.

- Courchesne, V., R. Tesfaye, P. Mirenda, D. Nicholas, W. Mitchell, I. Singh, L. Zwaigenbaum, and M. Elsabbagh. 2022. “Autism Voices: A Novel Method to Access First-Person Perspective of Autistic Youth.” Autism 26 (5): 1123–1136. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211042128.

- Creswell, J. W., and C. N. Poth. 2018. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Cridland, L., S. Jones, P. Caputi, and C. Magee. 2014. “Qualitative Research with Families Living with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Recommendations for Conducting Semistructured Interviews.” Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 40 (1): 78–91. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2014.964191.

- Crotty, M. 1998. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. London: Sage Publications.

- Cunningham, M. 2020. “This School is 100% Not Autistic Friendly!’ Listening to the Voices of Primary-Aged Autistic Children to Understand What an Autistic Friendly Primary School Should Be like.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 26 (12): 1211–1225. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1789767.

- Denzin, N. K. 1989. Interpretive Biography. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Depape, A., and S. Lindsay. 2016. “Lived Experiences from the Perspective of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 31 (1): 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357615587504.

- Devenish, B. D., A. Mantilla, S. J. Bowe, E. A. C. Grundy, and N. J. Rinehart. 2022. “Can Common Strengths Be Identified in Autistic Young People? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 98: 102025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2022.102025.

- Dindar, K., A. Lindblom, and E. Kärnä. 2017. “The Construction of Communicative (in)Competence in Autism: A Focus on Methodological Decisions.” Disability & Society 32 (6): 868–891. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1329709.

- Donaldson, A. L., K. Krejcha, and A. McMillin. 2017. “A Strengths-Based Approach to Autism: Neurodiversity and Partnering with the Autism Community.” Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups 2 (1): 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1044/persp2.SIG1.56.

- Eaves, L. C., and H. H. Ho. 2008. “Young Adult Outcome of Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 38 (4): 739–747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0441-x.

- Egilson, S. T., L. B. Ólafsdóttir, T. Leósdóttir, and E. Saemundsen. 2016. “Quality of Life of High-Functioning Children and Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Typically Developing Peers: Self- and Proxy-Reports.” Autism 21 (2): 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316630881.

- Elliot, A. J. 2006. “The Hierarchical Model of Approach-Avoidance Motivation.” Motivation and Emotion 30 (2): 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9028-7.

- Eroglu, M., and B. G. Kilic. 2020. “Peer Bullying among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Formal Education Settings: Data from Turkey.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 75: 101572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101572.

- Factor, R. S., T. H. Ollendick, L. D. Cooper, J. C. Dunsmore, H. M. Rea, and A. Scarpa. 2019. “All in the Family: A Systematic Review of the Effect of Caregiver-Administered Autism Spectrum Disorder Interventions on Family Functioning and Relationships.” Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 22 (4): 433–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-019-00297-x.

- Farley, M. A., W. M. McMahon, E. Fombonne, W. R. Jenson, J. Miller, M. Gardner, H. Block, et al. 2009. “Twenty-Year Outcome for Individuals with Autism and Average or near-Average Cognitive Abilities.” Autism Research 2 (2): 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.69.

- Farsinejad, A., A. Russell, and A. Butler. 2022. “Autism Disclosure – The Decisions Autistic Adults Make.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 93: 101936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2022.101936.

- Fisher, M. H., and J. L. Taylor. 2016. “Let’s Talk about It: Peer Victimization Experiences as Reported by Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Autism 20 (4): 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315585948.

- Fletcher-Watson, S., J. Adams, K. Brook, T. Charman, L. Crane, J. Cusack, S. Leekam, D. Milton, J. R. Parr, and E. Pellicano. 2019. “Making the Future Together: Shaping Autism Research through Meaningful Participation.” Autism 23 (4): 943–953. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318786721.

- Forsyth, R., A. Colver, S. Alvanides, M. Woolley, and M. Lowe. 2007. “Participation of Young Severely Disabled Children is Influenced by Their Intrinsic Impairments and Environment.” Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 49 (5): 345–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00345.x.

- Frazier, T. W., G. Dawson, D. Murray, A. Shih, J. S. Sachs, and A. Geiger. 2018. “Brief Report: A Survey of Autism Research Priorities Across a Diverse Community of Stakeholders.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 48 (11): 3965–3971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3642-6.

- Galpin, J., P. Barratt, E. Ashcroft, S. Greathead, L. Kenny, and E. Pellicano. 2018. “The Dots Just Don’t Join Up’: Understanding the Support Needs of Families of Children on the Autism Spectrum.” Autism 22 (5): 571–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316687989.

- Giarelli, E., J. Ruttenberg, and A. Segal. 2013. “Bridges and Barriers to Successful Transitioning as Perceived by Adolescents and Young Adults with Asperger Syndrome.” Journal of Pediatric Nursing 28 (6): 563–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2012.12.010.

- Gladding, S. 2009. Counselling: A Comprehensive Review (6th ed.). Pearson Education Inc.

- Goodall, C. 2018. “I Felt Closed in and like I Couldn’t Breathe”: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Mainstream Educational Experiences of Autistic Adolescents.” Autism & Developmental Language Impairments 3: 239694151880440. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396941518804407.

- Goodall, C., and A. MacKenzie. 2019. “Title: What About My Voice? Autistic Young Girls’ Experiences of Mainstream School.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 34(4): 499–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2018.1553138.

- Grant, A., and H. Kara. 2021. “Considering the Autistic Advantage in Qualitative Research: The Strengths of Autistic Researchers.” Contemporary Social Science 16 (5): 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2021.1998589.

- Greer, L. L., S. Yu, and J. S. Bunderson. 2015. “The Dynamics of Power and Status in Groups.” Academy of Management Proceedings 2015 (1): 11619. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2015.11619symposium.

- Grinker, R. R. 2020. “Autism, “Stigma,” Disability A Shifting Historical Terrain.” Current Anthropology 61 (S21): S55–S67. https://doi.org/10.1086/705748.

- Haegele, J. A., and S. Hodge. 2016. “Disability Discourse: Overview and Critiques of the Medical and Social Models.” Quest 68 (2): 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1143849.

- Hagerty, B. M., J. Lynch-Sauer, K. L. Patusky, and M. Bouwsema. 1993. “An Emerging Theory of Human Relatedness.” Image-the Journal of Nursing Scholarship 25 (4): 291–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1993.tb00262.x.

- Hasson, K., S. Keville, J. Gallagher, A. Onagbesan, and A. K. Ludlow. 2024. “Inclusivity in Education for Autism Spectrum Disorders: Experiences of Support from the Perspective of Parent/Carers, School Teaching Staff and Young People on the Autism Spectrum.” International Journal of Developmental Disabilities 70 (2): 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2022.2070418.

- Hatfield, M., M. Falkmer, T. Falkmer, and M. Ciccarelli. 2018. “Process Evaluation of the BOOST-A™ Transition Planning Program for Adolescents on the Autism Spectrum: A Strengths-Based Approach.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 48 (2): 377–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3317-8.

- Heasman, B., and A. Gillespie. 2017. “Perspective-Taking is Two-Sided: Misunderstandings between People with Asperger’s Syndrome and Their Family Members.” Autism 22 (6): 740–750. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317708287.

- Hebron, J., and C. Bond. 2017. “Developing Mainstream Resource Provision for Pupils with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Parent and Pupil Perceptions.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 32 (4): 556–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2017.1297569.

- Henninger, N. A., and J. L. Taylor. 2013. “Outcomes in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Historical Perspective.” Autism 17 (1): 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312441266.

- Hill, L. 2014. “Some of It I Haven’t Told Anybody Else’: Using Photo Elicitation to Explore the Experiences of Secondary School Education from the Perspective of Adolescents with a Diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorder.” Educational and Child Psychology 31 (1): 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319831487?icid=int.sj-full-text.similar-articles.1. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2014.31.1.79.

- Hill, V., E. Pellicano, A. Croydon, S. Greathead, L. Kenny, and R. Yates. 2016. “Research Methods for Children with Multiple Needs: Developing Techniques to Facilitate All Children and Adolescents to Have ‘a Voice.” Educational and Child Psychology 33 (3): 26–43. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2016.33.3.26.

- Howlin, P., S. Goode, J. Hutton, and M. Rutter. 2004. “Adult Outcome for Children with Autism.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 45 (2): 212–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x.

- Hurlbutt, K., and L. Chalmers. 2002. “Adults with Autism Speak out.” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 17 (2): 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576020170020501.

- Huws, J. C., and R. S. P. Jones. 2008. “Diagnosis, Disclosure, and Having Autism: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of the Perceptions of Adolescents with Autism.” Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 33 (2): 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250802010394.

- Hwang, Y. I., K.-R. Foley, and J. N. Trollor. 2020. “Aging Well on the Autism Spectrum: An Examination of the Dominant Model of Successful Aging.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 50 (7): 2326–2335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3596-8.

- Jackson, L., S. Keville, and A. K. Ludlow. 2022. “Anxiety in Female Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Lessons for Healthcare Professionals.” Qualitative Health Communication 1 (2): 80–98. https://doi.org/10.7146/qhc.v1i2.128871.

- Jones, J. L., K. L. Gallus, K. L. Viering, and L. M. Oseland. 2015. “Are You by Chance on the Spectrum?’ Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder Making Sense of Their Diagnoses.” Disability & Society 30 (10): 1490–1504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2015.1108902.

- Jones, R. S., C. Quigney, and J. C. Huws. 2003. “First-Hand Accounts of Sensory Perceptual Experiences in Autism: A Qualitative Analysis.” Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 28 (2): 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1366825031000147058.

- Josselson, R., ed. 2010. SAGE Publications, Inc., https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412961288.

- Kapp, S. K., K. Gillespie-Lynch, L. E. Sherman, and T. Hutman. 2013. “Deficit, Difference, or Both? Autism and Neurodiversity.” Developmental Psychology 49 (1): 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028353.

- Karcher, M. J., M. Holcomb, and E. Zambrano. 2008. “Measuring Adolescent Connectedness: A Guide for School-Based Assessment and Program Evaluation.” In Handbook of School Counseling, edited by H. L. K. Coleman & C. Yeh, 649–669. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Keen, D., D. Adams, K. Simpson, J. den Houting, and J. Roberts. 2019. “Anxiety-Related Symptomatology in Young Children on the Autism Spectrum.” Autism 23 (2): 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317734692.

- Kelly, C., S. Sharma, A.-T. Jieman, and S. Ramon. 2022. “Sense-Making Narratives of Autistic Women Diagnosed in Adulthood: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research.” Disability & Society 39 (3): 663–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2022.2076582.

- King, G., P. Rigby, and B. Batorowicz. 2013. “Conceptualizing Participation in Context for Children and Youth with Disabilities: An Activity Setting Perspective.” Disability and Rehabilitation 35 (18): 1578–1585. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.748836.

- Kirby, A. V., V. A. Dickie, and G. T. Baranek. 2014. “Sensory Experiences of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: In Their Own Words.” Autism 19 (3): 316–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314520756.

- Kornblau, B. L., and S. M. Robertson. 2021. “Special Issue on Occupational Therapy with Neurodivergent People.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association 75 (3): 7503170010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.753001.

- Kuusikko, Sanna, Rachel Pollock-Wurman, Katja Jussila, Alice S. Carter, Marja-Leena Mattila, Hanna Ebeling, David L. Pauls, and Irma Moilanen. 2008. “Social Anxiety in High-Functioning Children and Adolescents with Autism and Asperger Syndrome.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 38 (9): 1697–1709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0555-9.

- Lawrence, D. H., D. A. Alleckson, and P. Bjorklund. 2010. “Beyond the Roadblocks: Transitioning to Adulthood with Asperger’s Disorder.” Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 24 (4): 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2009.07.004.

- Leadbitter, K., K. L. Buckle, C. Ellis, and M. Dekker. 2021. “Autistic Self-Advocacy and the Neurodiversity Movement: Implications for Autism Early Intervention Research and Practice.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 635690. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635690.

- Lee, R. M., and S. B. Robbins. 1998. “The Relationship between Social Connectedness and Anxiety, Self-Esteem, and Social Identity.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 45 (3): 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.338.

- Levy, R., and P. Thompson. 2015. “Creating ‘Buddy Partnerships’ with 5- and 11-Year-Old-Boys: A Methodological Approach to Conducting Participatory Research with Young Children.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 13 (2): 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X13490297.

- Liao, X., X. Lei, and Y. Li. 2019. “Stigma among Parents of Children with Autism: A Literature Review.” Asian Journal of Psychiatry 45: 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2019.09.007.

- Lincoln, Y., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage

- Liptak, G. S., J. A. Kennedy, and N. P. Dosa. 2011. “Social Participation in a Nationally Representative Sample of Older Youth and Young Adults with Autism.” Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP 32 (4): 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e31820b49fc.

- Locke, J., E. H. Ishijima, C. Kasari, and N. London. 2010. “Loneliness, Friendship Quality and the Social Networks of Adolescents with High-Functioning Autism in an Inclusive School Setting.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 10 (2): 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01148.x.

- Magiati, I., C. Ong, X. Y. Lim, J. W.-L. Tan, A. Y. L. Ong, F. Patrycia, D. S. S. Fung, M. Sung, K. K. Poon, and P. Howlin. 2015. “Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder Attending Special Schools: Associations with Gender, Adaptive Functioning and Autism Symptomatology.” Autism 20 (3): 306–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315577519.

- Manzi, C., and M. Brambilla. 2014. “Family Connectedness.” In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, edited by A. C. Michalos. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_998.

- Marks, S. U., C. Schrader, T. Longaker, and M. Levine. 2000. “Portraits of Three Adolescent Students with Asperger’s Syndrome: Personal Stories and How They Can Inform Practice.” Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps 25 (1): 3–17. https://doi.org/10.2511/rpsd.25.1.3.

- Marshall, V., and B. C. Long. 2009. “Coping Processes as Revealed in the Stories of Mothers of Children with ASD.” Qualitative Health Research 20 (1): 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309348367.

- Mason, D., S. J. Capp, G. R. Stewart, M. J. Kempton, K. Glaser, P. Howlin, and F. Happé. 2021. “A Meta-Analysis of Outcome Studies of Autistic Adults: Quantifying Effect Size, Quality, and Meta-Regression.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 51 (9): 3165–3179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04763-2.

- Mattys, Laura, Ilse Noens, Kris Evers, and Dieter Baeyens. 2018. “Hold Me Tight so I Can Go It Alone’: Developmental Themes for Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Qualitative Health Research 28 (2): 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317730329.

- Mazefsky, C. A., J. Herrington, M. Siegel, A. Scarpa, B. B. Maddox, L. Scahill, and S. W. White. 2013. “The Role of Emotion Regulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 52 (7): 679–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.006.

- Meadan, H., J. B. Stoner, and M. E. Angell. 2009. “Review of Literature Related to the Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Adjustment of Siblings of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 22 (1): 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-009-9171-7.

- Meilleur, A. A., P. Jelenic, and L. Mottron. 2015. “Prevalence of Clinically and Empirically Defined Talents and Strengths in Autism.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 45 (5): 1354–1367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2296-2.

- Mervielde, I., B. De Clercq, F. De Fruyt, and K. Van Leeuwen. 2005. “Temperament, Personality, and Developmental Psycho-Pathology as Childhood Antecedents of Personality Disorders.” Journal of Personality Disorders 19 (2): 171–201. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.19.2.171.62627.

- Milton, D. 2012. “On the Ontological Status of Autism: The ‘Double Empathy Problem’.” Disability & Society 27 (6): 883–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008.

- Mitchell, P., E. Sheppard, and S. Cassidy. 2021. “Autism and the Double Empathy Problem: Implications for Development and Mental Health.” The British Journal of Developmental Psychology 39 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12350.

- Morgan, D. L. 2008. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, 816–817. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Mount, N., and G. Dillon. 2014. “Parents’ Experiences of Living with an Adolescent Diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Educational and Child Psychology 31 (4): 72–81. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2014.31.4.72.

- Moustakas, C. E. 1994. Phenomenological Research Methods. Sage Publications, Inc.