Abstract

Persons with albinism experience visual impairments and have unusually white hair and skin colour. In Nigeria, they face social disadvantages due to misconceptions about albinism, which create barriers to equal participation in education, employment, and society. This study explored the life stories of persons with albinism in Nigeria to understand the meanings they ascribe to their experiences. Using a Constructivist Grounded Theory methodology, forty-two interviews were conducted with eleven persons with albinism. ‘Being Different’ emerged as the main theme representing the life experiences of persons with albinism in Nigeria from childhood to adulthood. Participants expressed ‘Being Different’ through subthemes such as ‘being in a tug of war’, ‘disadvantaging schooling system’, and ‘suffering double tragedy’. The study concludes that strongly enforcing anti-discrimination laws, promoting inclusive education, and regularly educating the public about albinism can significantly reduce the negative effects of ‘Being Different’ in Nigeria.

Points of Interest

Albinism is a condition that people are born with. It is caused by a lack of pigmentation (colour) in the body. Persons with albinism have a physical appearance which is strikingly different from the majority of the Nigerian population.

Due to visual and skin impairments, persons with albinism have difficulty seeing clearly even with prescription glasses, and they have a low tolerance for sunshine.

Because albinism is poorly understood in Nigeria, persons with albinism are often subjected to stigma and discrimination.

To understand their experiences of stigma, this study examined the life stories of persons with albinism in Nigeria.

Participants described their experiences of living with albinism as ‘being different’. This paper argues that persons with albinism are rightful members of society and deserve full participation in all social institutions across Nigeria.

Introduction

In recognition of the importance of person-centred language (United Nations Citation2007), this paper adopts the term ‘Persons with Albinism’ throughout. There is no consensus on the exact number of persons with albinism in Nigeria. Reported prevalence rates vary across time and by region, from 1:2858 in Lagos, to 1:7000 in Benin City (Barnicot Citation1952), to 1:15,000 across Anambra, Imo, Enugu, Ebonyi and Abia States (Okoro Citation1974). The most recent evidence suggests that when the Nigerian population was one hundred and eighty million in 2019, there were more than two million persons with albinism in Nigeria (Anele Citation2019). Furthermore, sub-national prevalence data obtained from hospital attendance records in 2019 estimated 6.39 persons with albinism per 10,000 individuals in Nigeria (Ajose and Cole Citation2019). With a population estimate of two hundred and twenty-nine million in Nigeria in 2024 (United Nations Population Fund Citation2024), it is likely that the number of persons with albinism in Nigeria has also increased significantly.

Persons with albinism constitute one of the most socially disadvantaged groups in Nigeria. Several studies indicate that persons with albinism experience social stigma, social exclusion, and persecution across Sub-Saharan Africa due to their physical appearance and associated impairments (Aborisade Citation2021; Ololajulo and Omotoso Citation2023; Kiluwa, Yohani, and Likindikoki Citation2022; Masanja, Imori, and Kaudunde Citation2020; Reimer-Kirkham et al. Citation2019; Taylor, Bradbury-Jones, and Lund Citation2019; Imafidon Citation2020). Albinism results in lifelong limitations for the following reasons. Firstly, persons with albinism are born with visual impairment, ranging from severe to functional blindness (Brilliant 2015; Estrada-Hernández and Harper Citation2007; Federal Ministry of Education Citation2019). Secondly, individuals with albinism lack pigmentation in their skin, which makes them more vulnerable to skin cancer. This is due to their reduced ability to filter ultraviolet rays from the sun, especially in areas with consistently high daytime temperatures (Liu et al. Citation2021; Nikolaou, Stratigos, and Tsao Citation2012; Saad et al. Citation2007). Finally, several studies indicate that societal misconceptions of albinism exist in Nigeria due to a poor understanding of the condition, creating stigma and unfair treatment of persons with albinism (Audu et al. Citation2013; Etieyibo and Omiegbe Citation2016; Okafor et al. Citation2022). Ultimately, the combination of visual and dermal impairments, along with social stigma, limits life chances for persons with albinism in Nigeria. This restriction affects their equal participation in education, employment, and other social goods (Estrada-Hernández and Harper Citation2007; Reimer-Kirkham et al. Citation2019; Saka et al. Citation2020). This study aligns with the social relational definition of disability, which views disability as ‘a form of social oppression involving the social imposition of restrictions of activity on people with impairments and the socially engendered undermining of their psycho-emotional wellbeing’ (Thomas Citation1999, 60; Thomas Citation2003).

The Nigerian government signed the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2007, and subsequently adopted it in 2010 (United Nations Citation2023). However, it was not until 2019 that the Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018, was enacted into law (Federal Republic of Nigeria Citation2019). This Act provided a legal framework to promote equal access to social participation and opportunities for people with disabilities, including mandating a 5% staffing reservation for individuals with disabilities across the public sector labour force. Additionally, the Nigerian government established a National Commission for Persons with Disabilities in 2020 with the primary responsibility of implementing and coordinating the execution of social development for people with disabilities. A notable output of the Commission is the development of the Disability Inclusion Assessment and Diagnostics Tool. This tool is expected to be utilised by stakeholders within disability networks across Nigeria to identify the varied needs of individuals with disabilities, particularly in terms of occupational and structural barriers (National Commission for Persons with Disabilities Citation2021).

Whilst these policy changes are important, functional lapses in the legislation implementation framework have been identified and criticised as inadequate for tangible and sustainable effectiveness (Amucheazi and Nwankwo Citation2020; Arimoro Citation2019; Etieyibo and Omiegbe Citation2021). For example, there is no clear provision to enumerate the number of individuals with disabilities across all ages and communities in Nigeria. Without valid metric data to identify, quantify, and qualify diverse presentations of disabilities, it becomes difficult to allocate resources and interventions to promote inclusion and improve the quality of life for persons with disabilities in Nigeria. Similarly, the legal framework and implementation plan fail to consider sociocultural drivers of disability perceptions which complicate interactions between Nigerian society and people with disabilities. Therefore, there is a risk of missing the opportunity to identify and address the fundamental causes of multiple disadvantages individuals with disabilities experience in Nigeria.

Several studies have examined and reported lived experiences of persons with albinism in Nigeria. For example, Ezeilo (Citation1989) explored the psychological aspects of albinism within a higher education setting. In the study, all respondents reported feeling disempowered because the university community and extended society were ‘unkind and rejecting’ (1989, 1130) largely due to their conspicuous physical appearance. Ikuomola (Citation2019b) investigated the implications of albinism misconceptions on health-seeking behaviour among women with albinism in South West Nigeria, which is the geopolitical region of the Yoruba people. He discovered that Yoruba cultural beliefs view albinism as a sign of spiritual evil. This influences how healthcare providers interact with women who have albinism and consequently discourages these women from seeking medical care. A study which explored the social constructions of women with disabilities in Lagos concluded that negative sociocultural nomenclature for disabilities, including albinism in the Yoruba language, reinforced experiences of societal discrimination, exclusion and, in some cases, bodily assault (Olaitan Citation2023). Ololajulo and Omotoso (Citation2023) documented the employment experiences of women with albinism in Ibadan, a Yoruba-speaking city. They conceptualised these experiences as manifestations of ‘double jeopardy’ (2023, 3) to highlight the combined disadvantage of being a woman with disabilities in a traditionally patriarchal society. The study reported all participants encountered varied forms of subtle and direct rejection within formal and informal settings. Potential employers who were secondary participants in the study by Ololajulo and Omotoso (Citation2023) admitted that individuals with albinism are viewed through the lenses of repulsion and perceived laziness based on their physical appearance. These studies consistently highlight the influence of Yoruba culture on societal attitudes towards persons with albinism. This is due to mythical traditional and cultural beliefs associated with albinism among the Yoruba people (Adenekan Citation2019; Omobowale and Olutayo Citation2009), which shape societal views across South West Nigeria. For example, there are beliefs that persons with albinism are witches, or their body parts have mystical powers, and as a consequence, people are found dead or sacrificed. The belief, or misconception, is that body parts can be used in rituals to gain power, success, or improved vitality (Ikuomola Citation2019b).

Given that Nigeria is a culturally diverse country, our study attempted to supplement existing knowledge of this phenomenon by exploring the life stories of persons with albinism in Nigeria outside the South West region. Our aim was to develop recommendations for interventions that could be applicable in diverse sociocultural settings across Nigeria.

Research process

Study design

The research design for this study was based on Kathy Charmaz’s constructivist grounded theory (CGT) (Charmaz Citation2006; Charmaz Citation2014). This was considered suitable because its elements enabled the emergence of a theoretical explanation of what it means to be a person with albinism in Nigeria. This research was underpinned by CGT’s ontological stance on multiple realities (Charmaz Citation1995; Charmaz Citation2002) which argues that the life experiences of an individual with albinism in Nigeria will be shaped by the prevailing Nigerian sociocultural context. Furthermore, this study aligns with the epistemological position of CGT that a phenomenon such as albinism is best understood when it is recalled, interpreted, and constructed by people who are actively living its realities (Charmaz Citation2007). Constructivist grounded theory is also valuable for social justice research because of its respect for participants’ voice when examining social processes, context and meaning (Charmaz Citation2005; Charmaz Citation2011).

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Sub Committee of the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Society at the University of Chester with code RESC0116-671. All participants were given a participant information sheet [PIS] which contained information on the purpose and scope of the study, including individual rights as co-producers of knowledge. Initial data collection commenced only after participants understood the PIS and consented to participate.

Participant recruitment

Recruitment and data collection were completed by the lead author, a Nigerian researcher with a passion for social justice. Purposive sampling was the first strategy adopted for participant recruitment (Matthew and Michael Citation1994). The participants were individuals who have albinism, over the age of 18 and registered service users of The Albino Foundation (TAF) Africa. TAF Africa is a non-governmental organisation that advocates the rights and social inclusion of persons with albinism in Nigeria. The management of TAF Africa approved the lead author to contact service users about participation and appointed a resident counsellor to coordinate participant recruitment. This was to engender a sense of trust and security for potential participants. All face-to-face contact with participants occurred at TAF Africa’s head office in Abuja. This formed the setting for data collection and doubled as a means to promote non-maleficence because it offered both a familiar environment to participants and a safe space for the investigator. As a location, Abuja, the federal capital city of Nigeria, enabled contact with individuals from diverse ethnicities and sociocultural backgrounds. This indicates that findings represent experiences of participants from across Nigeria and not from a particular region as is often the case with previously conducted studies on the subject.

The lead author attended a TAF Africa service users meeting to introduce the purpose of the study and establish familiarity with prospective participants. At the meeting, ethical considerations were highlighted, including participants’ right of autonomy to participate and withdraw without consequences. To manage participant expectations, it was explained that findings from the study will not provide instant solutions but could serve to amplify participant’s voice and thus, could potentially benefit future outcomes for persons with albinism in Nigeria. A notebook was left with the resident counsellor at TAF Africa, who was well known and easily accessible to service users. Interested members were invited to register their contact details and preferred date of interview. Twenty people indicated an interest to participate; however, data were obtained from only eleven participants because nine of them did not attend the scheduled interview. All the participants chose pseudonyms to anonymise their names. As participants were likely to recall painful and traumatic experiences while providing data, they were informed that the resident counsellor would always be available in the connecting room during interviews to provide emotional support whenever the need arose.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

The final sample comprised 9 women and 2 men, all born and raised in Nigeria, but from different geopolitical zones, and were aged between 19 and 46. At the point of data collection, all 9 women were unmarried, 7 of whom had at least one child for whom they were solely responsible. One male participant was married and had a child, while the other male was single with no children. Ten participants had completed some form of post-secondary education: 6 had completed a vocational apprenticeship; 2 had polytechnic diplomas; and 2 had university degrees [and were the only ones in fulltime employment after previous several unsuccessful attempts]. The remainder of the sample was either unemployed or worked in zero-hours cleaning jobs.

Data collection

Initial data collection was conducted by means of in-person, semi-structured interviews. The interviews commenced after participants agreed to be involved in the study, signed the consent form and provided verbal approval to audio-record their responses; the recordings were later transcribed manually and anonymised. As individuals with albinism in Nigeria are an oppressed group who are usually not offered the opportunity to be heard (Ikuomola Citation2019b), it was considered essential the interviews offered participants a sense of control and freedom to talk freely. For this reason, interviews began with ‘Please tell me the story of your life as a person with albinism living in Nigeria’. This line of questioning was drawn from Wengraf’s single-question-aimed-at-inducing-narrative (Wengraf Citation2004, p.4) which is considered a useful means of eliciting narrative biographical stories. Participants spoke mainly in the English language. Although, there were instances when they switched to Nigerian Pidgin, a lingua franca that many Nigerians speak (Agbo and Plag Citation2020), including the lead author. During the interview process, some incidents in participants’ lives evoked emotional reactions, including crying. When this occurred, participants were asked if they wished to pause the interview to collect their thoughts or invite the counsellor. All participants continued, determined to share their stories, and none required the support of the counsellor. As participants recalled and constructed their life stories, these incidents were noted as probes in the same language as was narrated by participants. These probes were the foundation for understanding what it means to be a person with albinism in Nigeria. As analysis progressed, additional data were collected by telephone calls only after participants affirmed their interest to contribute further to this study.

Data analysis

The methods for data analysis were influenced by Charmaz (Citation2014) and Strauss and Corbin (Corbin and Strauss Citation2008; Strauss and Corbin Citation1990; Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). Data were analysed using the constant comparative method whereby transcripts were interrogated line-by-line and initially coded in gerunds (Charmaz Citation2006; Strauss and Corbin Citation1990; Corbin and Strauss Citation2008; Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). These codes exemplified the literal meaning of what was happening in participants’ lives.

Initial codes were compared across all transcripts for nuances and commonalities of experiences. After identifying the varied and shared experiences, we kept the selective in-vivo codes in the original language used by the participants. This aligned with the essential element of constructivist grounded theory methodology, which is the co-construction of meanings between participant(s) and researcher (Charmaz Citation2006; Charmaz Citation2014). Progressively, selective in-vivo coding of data signalled the needed for theoretical sampling, which involved the collection of additional information from certain participants whose stories offered theoretical insights into understanding the realities of being a person with albinism in Nigeria. During theoretical sampling, in-vivo codes focused on data that provided conceptual insight into the meaning of being a person with albinism in Nigeria. In-vivo codes were exact words participants used to describe the meaning they attached to their experiences at the time. Examples of in-vivo codes in this study are ‘being in a tug of war’ and ‘double tragedy’. Subsequently, focused conceptual codes were compared with literature to determine how data could be explained with extant theories. Because collected data were self-constructed autobiographies of the participants, it was helpful to group emerging codes against a life course chronology. Collectively, a theme that characterises the participants’ life experiences emerged from the codes.

Throughout the stages of data interrogation, memos were written to document developing understanding. These memos served as an analytical compass to ensure that interpretations were consistent with participant data. Data analysis required an ongoing engagement with participants and concluded when there were adequate descriptions of experiences to explain what it means to be a person with albinism in Nigeria. This stage is termed ‘theoretical sufficiency’ (Charmaz Citation2014; Dey Citation1999), and it marked the end of data collection and analysis. In total, forty-two in-depth interviews were conducted to answer the research question enabling the emergence of an explanation of ‘Being Different’.

Results

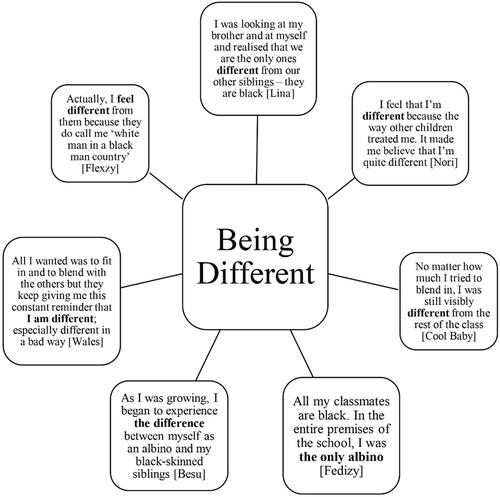

‘Being Different’ emerged as the definition of life for a person with albinism in Nigeria. This is because participants described their interactions with Nigerian society as predetermined by their different physical appearance, societal beliefs about albinism, and the resulting disabilities.

‘Being Different’ represents the continuum of life experiences for persons with albinism from childhood to adulthood. The components that characterise ‘Being Different’ are: (a) being in a tug of war, (b) disadvantaging schooling system; and (c) suffering double tragedy.

Being in a tug of war

The experiences that epitomise ‘being in a tug of war’ occurred within the family home environment. Data revealed participants whose parents had either no, or a low level of education misunderstood albinism. These parents believed albinism was contagious and children with the condition were blind. It seemed these parents believed it was not a prudent use of family income to send a child with albinism to school. Consequently, children with albinism were excluded from schooling and often from social occasions. These beliefs underlie the feelings of embarrassment felt by parents and the negative treatment of children with albinism. For participants in this study, fathers were the primary perpetrators of these adverse childhood experiences. In some cases, the displeasure associated with having a child or children with albinism caused tension between parents and the eventual disintegration of the family.

My daddy was blaming my mom that she’s the one that brought albinism. It was a tug of war that my dad even abandoned the home and refused to take responsibility for me [and] the last born who is [also] an albino. You know when you are not very educated; you accept anything that the culture tells you. Maybe he was thinking that [I] won’t be useful in life, so he didn’t care much. But if he had gone to school, maybe things would be different – Uma, North Central Nigeria.

My mother told me that my father accused her [of] bearing albinos and that my father hated her because of it. When my mother could not bear the bad treatment any longer, she left – Besu, North West Nigeria.

‘Being in a tug of war’ typifies strife within the family unit. The quotes provided highlight the impact of diverse negative cultural beliefs about albinism and identify a lack of family and societal understanding of the condition, including its impact on the individual. Participants acknowledged that their experiences of ‘being in a tug of war’ initiated personal loss of self-identity and feelings of guilt and inadequacy that continued into adulthood.

Disadvantaging schooling system

Findings revealed several ways in which interacting with the schooling environment intensified the realities of being different from the rest of the local population. Firstly, study participants lost the protection of the family home environment, especially those who had not been able to develop social skills due to exclusion. Secondly, functional limitations due to visual and dermal impairments became immediately noticeable. In particular, participants struggled to see the chalkboard and were unable to participate in outdoor playground activities with peers. Finally, participants described their experiences of being bullied because of their atypical physical appearance.

In school, I was the only albino. So, people mocked me; some laughed at me – some called me names. Some will say ‘oyinbo pepper*’. Some will just be laughing at me about my eyesight. It affected me badly. I will sit lonely and start crying– Fedizy, South South Nigeria.

*Oyinbo pepper is a derogatory term for white foreigners to describe how their skin turns red when eating spicy Nigerian food. The term is equally demeaning to a person with albinism because it draws undue attention to their skin colour.

According to participants, the schooling system was poorly configured and offered no provisions for learning support to children with visual impairment. In addition, data revealed there were occasions when teachers were complicit in reinforcing disadvantages for children with albinism in school.

I didn’t have support in terms of school. I didn’t write in class because I couldn’t see what was written on the board. But my teachers did not understand that it’s not me not wanting to participate. They thought that I was just too lazy to write. One day, my teacher saw that I was not copying notes. She asked me why, and when I couldn’t give her an answer, she caned me badly. This happened a lot of times – Nori, South East Nigeria.

Consequently, lack of participation in learning activities led to poor school performance, notably in subjects that involve shapes and figures, such as mathematics and biology.

I never passed mathematics because when I see a 5, I think it’s an 8; when I see a 3, I think it’s an 8. Another was biology. There was an exam [whereby] we were to identify a specimen under the microscope. I looked through the screen three times, and I did not see anything. But my other classmates were able to identify it. That was enough to make me different from them. – Nori, South East Nigeria.

The absence of support for the participants in the schooling system seemed constant in primary and secondary education as they progressed from childhood to adolescence. Equally as participants approached adulthood, the effects of life experiences began to impact their sense of self.

All I wanted to do was to fit in and to blend with the others. [But] they kept giving me this constant reminder that I am different; especially different in a bad way – Wales, South West Nigeria.

The participants’ experiences in the home and schooling environments, as described above, resulted in limitations such as low self-esteem and poor grades, which later impacted their life outcomes in adulthood.

Suffering double tragedy

The female participants described the combination of being a woman and having albinism as ‘suffering double tragedy’. While all people with albinism experience discrimination in the job market, the combination of gender and disability discrimination made it particularly difficult for women with albinism to find employment and pursue romantic relationships.

Being a woman in Africa is a disability. So, imagine you being a lady and then, being a lady with albinism: that is a double tragedy for you in Nigeria, in fact for all persons with albinism in Africa – Nori, South East Nigeria.

The excerpt below describes difficulties in accessing the job market in the private and public sectors. These difficulties were common for all participants, regardless of gender.

There was a time they needed someone in Abuja to be the local council ward coordinator. The Councillor of our ward nominated me for the position and forwarded my name and contact details to the chairman of the screening committee. I went to see the chairman, and the moment he saw me, he said I was not qualified for the position. I believe it was my skin colour. There are lots of things that I deserved but didn’t get because of my skin colour - Cool Baby, North East Nigeria.

Exclusion from employment opportunities seemed to stem from misinformed societal beliefs that individuals with albinism might bring bad luck to the workplace and are unproductive workers.

At work, people look at me and like ‘Is this guy competent to do this thing?’ – Wales, South West Nigeria.

The realities of exclusion and rejection for persons with albinism transcend the employment market. For example, all participants attested to experiencing ridicule and disappointment whenever they attempted to engage in a romantic relationship. Consequently, these experiences heightened feelings of self-doubt and inadequacy. Excerpts from a male and female participant provided below demonstrate that complications associated with romantic relationships were not gender specific. However, one could argue that women with albinism are more impacted than men with albinism.

When [I started] picking interests in women. I had extreme difficulty. There was always that rejection. It made me feel ‘will I ever find a life partner?’ – Wales [M]

All my relationships have been short-lived; I’ve been used, disgraced, disrespected and rejected because I am an albino. This has made it difficult for me to sustain a relationship even until now - Cool Baby [F]

Information from female participants indicated their relationships with men in the Nigerian society were characterised by deceit, sexual exploitation, abandonment, and, as a result, living as single mothers.

Men who go into relationship with me often believe they deserve thanks. Some men want to have [me] because [I am] an albino – to taste me – to take advantage of [me]. One of them said he liked me, that he would help me. But he deceived me and forced himself on me. I got pregnant and had to drop out of school- Ella, South South Nigeria.

Excerpts from participants’ stories convey the cumulative effects these adverse life experiences have on their mental health and wellbeing.

I struggle with [an] inferiority complex, depression and suicidal tendencies due to the stigma and discrimination – Ella, South South Nigeria.

Finally, ‘Being Different’ emerged as a central theme that consolidates the meaning of being a person with albinism in Nigeria, derived from the way participants constructed and narrated their life stories. The data that support this inference are illustrated in below.

Coping with ‘being different’

Given the myriad life challenges that constitute experiences of albinism in Nigeria, participants in the study adopted various ways to manage the stressful situations associated with being different.

Amplified listening skills

In the context of primary education, being visually impaired meant the participants often fell behind on lesson notes as they could not clearly see the chalkboard and keep pace with other learners. As a result, all participants identified a reliance on their listening skills to follow classroom lessons and complete notes. As participants progressed to secondary and post-secondary education, data revealed how developing keen listening skills in childhood was helpful because the usual form of lesson delivery at the time was via dictation. In some sense, these alleviated feelings of inadequacy.

‘I was able to adapt my listening skill for writing very fast. That is when I began to realise that if you are smart in school, others will come to you to teach [them] and that increases your self-esteem’ – Wales, South West Nigeria.

Joining the Albino Foundation

As the participants approached adulthood, they began to develop the need to identify with people of shared attributes. Signing up to become members and service users of TAF Africa enabled access to multiple advantages, including free sunscreen for skin protection, counselling services, an orientation on albinism management and self-care, opportunities for disability advocacy, and a social hub for recreation and wellbeing. In their own words, the participants applauded TAF Africa for significantly improving their sense of self.

I am glad I joined The Albino Foundation because it has helped me to accept

myself and my brother, who is also an albino’ – Cool Baby, North East Nigeria.

Inuring self and challenging others

Drawing on self-help and albinism management resources provided by TAF Africa, most study participants feel empowered to reject victimisation and occasionally raise albinism awareness with the perpetrator, especially in response to name-calling.

I’m very upfront towards them. I correct them immediately and I try and resolve the issue there and then - I challenge those things – Wales, South West Nigeria.

Practicing faith

The data highlighted the importance of faith, particularly in God as the creator of all things, commonly believed to have a unique plan for every person. Consequently, participants relied on their faith practices to seek solace and build resilience against the social consequences of albinism.

God has His reasons for making me an albino. I am convinced that He has a purpose for me’- Fedizy, South South Nigeria.

Discussion

In this study, ‘Being Different’ has emerged as the thematic summary of life experiences for persons with albinism in Nigeria. In itself, ‘Being Different’ represents the variability of adverse experiences that persons with albinism contend with as they engage with society and social institutions in Nigeria at different stages, from childhood to adulthood. These life experiences, although individually endured, are remarkably similar in their impact on life outcomes for persons with albinism.

For example, experiences of ‘being in a tug of war’ depict unfair treatment within the family home environment. These experiences echo the findings of Likumbo, De Villiers, and Kyriacos (Citation2021) in their study of women who have children with albinism in Malawi. One key finding was also the occurrence of paternal blaming and alienation of the child due to misinformation on the condition. In line with our research findings, a study in Nigeria by Aborisade (Citation2021) similarly showed that children with albinism are often subjected to prejudice by their parents and siblings. Respondents in the study reported being physically assaulted by their fathers, denied educational and vocational opportunities due to perceived physical weakness, and treated with resentment within their families, as if being born with albinism was their fault.

One of the limitations of our study is the absence of parental perspectives on childhood experiences, particularly to understand fathers’ unfavourable treatment of children with albinism. It was unfeasible to interview participants’ parents because some had died, and in several cases, relationship with their parents was strained. Nonetheless, participants attributed the unfair paternal treatment they experienced to a lack of education and influence of sociocultural myths about albinism. At the time of writing, it was not possible to identify literature which explored the perspectives of fathers whose children have albinism in Nigeria. This would be a useful focus for future research.

Here, we argue that negative parental treatment of children with albinism is likely due to their awareness of the difficulty associated with growing up with albinism in Nigeria, and possibly because of poor understanding of the condition. Notwithstanding, the Child’s Rights Act of 2003 is clear on the rights of children in Nigeria (National Human Rights Commission Citation2023). Part II Sections 10 (2) and 11 (a) of the Child’s Right Act emphasise a child’s right to dignity and freedom from discrimination, stating that no child should be subjected to disability or deprivation due to their birth circumstances, nor should they suffer physical, mental, or emotional injury, abuse, neglect, or maltreatment (National Assembly of The Federal Republic of Nigeria Citation2003, A460). At the time of writing, thirty-three out of thirty-seven states in Nigeria had domesticated the Child’s Right Act into law (Partners West Africa Nigeria Citation2023). Considering this legislation and commonalities in participants’ adverse childhood experiences, we believe that ‘being different’ serves to highlight the social injustices experienced by individuals with albinism in Nigeria.

The National Policy on Albinism (Federal Ministry of Education Citation2019) recognises the adverse impact of socio-culturally constructed myths associated with albinism on the social life of persons with albinism in Nigeria. Furthermore, the policy identifies the need for mass reorientation, thereby validating participants’ stories.

The range of adverse schooling experiences identified in this study aligns with dated and recent evidence from across Sub-Saharan Africa, suggesting that ‘disadvantaging schooling system’ represents an ongoing reality for persons with albinism in Nigeria and across the sub-continent. For example, evidence of exclusion from learning activities, punishment for not completing lesson notes, peer and teacher bullying, and lack of educational support at school have been reported in Nigeria (Njoku and Amadi Cajetan Citation2020; Nwosu et al. Citation2019), Zambia (Kanyungo and Penda Citation2021; Mtonga et al. Citation2021), Zimbabwe (Machingambi Citation2023), and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Meddeb Citation2016).

The schooling environment should provide a safe learning community in which pupils can positively and beneficially engage with peers and teachers (Sayfulloevna Citation2023). However, the extent to which mainstream schooling environments in Nigeria are safe for persons with albinism remains contentious. Here, ‘safe’ is used broadly to include the overall wellbeing of a child with albinism, especially regarding their participation in learning and their social relationships at school.

Albinism advocates in Nigeria are resolute about their preference for inclusive education (Abdulrahman Citation2023; Adelakun and Ajayi Citation2020; Inclusive News Network Citation2023). Admittedly, Mtonga, Kalimaposo, and Mandyata (Citation2023) reported that children with albinism in Zambia have better social and academic outcomes in special schools due to personalised education provided by specially trained teachers and an adaptable learning environment. However, in the context of Nigeria, stakeholders in the albinism community argue that enrolling children with albinism in special schools is counterproductive. They believe it will only serve to widen the margins of segregation and, ultimately, undermine the relevance of inclusion, diversity, and equal opportunity for academic success (Epelle Citation2022). Indeed, there are diverse views on the potential of mainstream schools to meet the needs of individuals with visual impairment. For instance, Brydges and Mkandawire (Citation2017) explored the opinions of students with visual impairment in Lagos. They reported that while students identified the usefulness of engaging with fully sighted children, they all highlighted the issue of bullying and intolerance in mainstream schools. In conclusion, the students admitted feeling safer in a learning environment that is more empathetic and aware of their limitations.

Similarly, parents of children with impairments in Nigeria have expressed doubts that mainstream education can provide adequate learning support, safety and required environmental adaptations for their children (Torgbenu et al. Citation2021). Based on the findings of this study, it is reasonable to deduce that participants’ experiences of a ‘disadvantaging schooling environment’ is inconsistent with the ideals of inclusive education. In accordance with Article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, individuals with albinism in Nigeria are allowed two and a half times the standard amount of time to complete their work during examinations at all educational levels (Federal Ministry of Education Citation2019). However, the reality of providing inclusive education in Nigeria requires a strategic modification in the schooling systems. Other African countries have good practices that are worth copying, especially Malawi and Tanzania. For instance, in Malawi, disability resource centres are attached to mainstream schools, and specialist teachers are deployed to these resource centres on a rotational basis (Lynch, Lund, and Massah Citation2014). These centres serve as hubs for teachers and parents to access training and development on how best to support a child with albinism in and out of the classroom, including raising disability awareness amongst school children. In addition, itinerant specialist teachers monitor the provision of learning support to pupils with albinism and their academic outcomes. In Tanzania, two mainstream schools at primary and secondary levels are championing the provision of inclusive education for children with albinism. This is achieved by adopting pedagogical models which prioritise learning diversity, investing in barrier-free facilities, and upholding a social culture of respect to make learning accessible and conducive for pupils (Holzinger et al. Citation2023). While these approaches could be contextualised to fit the Nigerian educational landscape, providing good quality inclusive education will require intentional political will and national investment. As a starting point, this study recommends albinism awareness training be mandated for all teachers, particularly in primary and secondary education. Similarly, disability sensitisation should be adopted into the learning curriculum to promote social-emotional learning among school administrators, teachers, and pupils (Juvonen et al. Citation2019). This may foster empathy, positive group dynamics, and reduce unhealthy adherence to sociocultural misconceptions about albinism.

Life limitations for persons with albinism in Nigeria come to full manifestation when individuals attempt to engage with the employment market. The ‘Suffering double tragedy’ theme identifies discriminations that disempower persons with albinism from opportunities to earn a living. Consequently, many persons with albinism in Nigeria are resigned to a life of poverty, which could cause generational deprivation. A point to note is that exclusion from employment opportunities affects persons with albinism regardless of whatever qualifications and competencies have been acquired. Similar findings have been reported from investigations conducted in Nigeria by Aborisade (Citation2022), in Ghana (Benyah Citation2017), Zimbabwe (Maunganidze, Machiha, and Mapuranga Citation2022), and South Africa (Mather et al. Citation2020). A recurrent theme across these studies is employment discrimination and exclusion of persons with albinism are underpinned by sociocultural perceptions of albinism, which are further heightened by physical appearance and visual impairment. The Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act of 2018, which is expected to enable access to employment opportunities for individuals with albinism, has been criticised for being poorly enforced (Aborisade Citation2022). Recognising legislation alone is not enough to achieve equality, TAF Africa has launched an ongoing nationwide campaign tagged ‘ABLEtoSERVE’ to promote the inclusion of persons with disabilities in the labour force (TAF Africa Citation2023). For the ‘ABLEtoSERVE’ campaign to gain traction, the leadership of TAF Africa is currently leveraging the influence of captains of industry. The campaign has obtained the endorsement of the People’s Democratic Party, the major opposition political party in Nigeria (Agbo Citation2023a, Citation2023b).

There is abundant evidence from Sub-Saharan African countries of the multiple forms of violence inflicted on females with albinism, especially ritual killings, and mutilations (Amnesty International Citation2017; Aquaron, Djatou, and Kamdem Citation2009; British Broadcasting Corporation Citation2014; Ikuomola Citation2015a; Masanja, Imori, and Kaudunde Citation2020; Mwiba Citation2018).

In this study, ‘suffering double tragedy’ typifies the difficulties encountered by women with albinism in Nigeria in securing romantic relationships. A notable finding is that the female participants who contributed to this study did not report instances of physical violence. However, this does not mean that persons with albinism in Nigeria do not experience persecution and bodily harm, as such incidents may be underreported. In this study, it should be borne in mind that participants believe the reason men are attracted to them is not out of genuine affection but out of transient curiosity that soon faded away after engaging in sexual intercourse. The findings of Ikuomola (Citation2019a) in his study, which examined the sexual experiences of women with albinism in southern Nigeria, identified similar findings. Ikuomola (Citation2019a) drew on Moradi and Huang (Citation2008) objectification of the body model to explain why women with albinism are at a more significant disadvantage in experiencing adverse romantic relationship experiences. It seems the sexualisation of a person with albinism starts in childhood when parents begin to contemplate if their child would be desirable enough for marriage. Parents often start drawing attention to the development of body parts and expressing worry over the child’s attractiveness. This can contribute to self-stigma and a desperate longing for acceptance. Consequently, these insecurities can make a girl or woman with albinism vulnerable to being exploited by sexual predators. Ikuomola (Citation2019a) iterates that socioeconomic deprivation exacerbates the impact of sexual objectification on women with albinism.

Although descriptions of myth have not emerged in participants’ narratives, several other research investigations on albinism have identified superstition as the driver of harmful interest in persons with albinism. Across Africa, traditional cultural beliefs, for example, that girls or women with albinism are magical beings with the power to confer fortune and restore health, may provide further perspective on why they are targeted for sexual exploitation (Duri and Makama Citation2018; Machoko Citation2013; Ojilere and Saleh Citation2019; Phatoli, Bila, and Ross Citation2015). Reflecting on the data from female participants, this may explain why men often abandoned them once they realised that having sexual relations with a woman with albinism does not bestow supernatural wealth or healing.

Collectively, the participants in our study adopted various strategies of stigma management and behavioural responses to cope with the disadvantages of albinism in Nigeria. Lazarus and Susan (Citation1984) transactional model of coping contends that a person’s capacity to cope and adjust to challenges is a consequence of transactions between person and environment. This offers a conceptual framework to understand participants’ coping strategies. A key theme in our findings called ‘Amplified listening skills’, demonstrated how study participants worked hard to develop their listening skills. This helped them to deal with the problem of not seeing the classroom chalkboard clearly. ‘Joining the Albino Foundation’ is a support-seeking form of social coping to alleviate feelings of self-stigma and improve self-empowerment. ‘Inuring self and challenging others’ offer the opportunity to regulate stigma-informed emotions while confronting the injustice of name-calling. For the participants, the practice of faith facilitates self-reinvention as they pursue meaning and life purpose.

Goffman’s (Citation1963) theory of stigma also provides a robust theoretical framework to explain the complexities of life as a person with albinism in Nigeria. Goffman defined stigma as an ‘attribute that is deeply discrediting’ (1963, 3) which could be a visible physical attribute such as albinism, or a hidden attribute such as mental illness or even a criminal record. Albinism falls into the ‘abominations of the body’ stigma group (Goffman Citation1963, 4). Stigma against people with albinism appears to be a result of other people’s fears. These fears are formed by a lack of awareness and information about albinism (Bradbury-Jones et al. Citation2018; Ikuomola Citation2015b; Lynch, Lund, and Massah Citation2014; Miles Citation2011). Therefore, society makes erroneous assumptions, constructing stereotypes to marginalise persons with albinism from exercising their rights to full participation in society. The multiple disadvantages experienced by persons with albinism in Nigeria have significant implications for social justice.

Conclusion

The components of ‘Being different’ can serve as a potential systematic approach to implementing interventions that could help reduce the inequalities and associated injustices faced by persons with albinism in Nigeria. For example, opinion shapers could use the coping strategies that study participants have used to inform policy implementation. Based on the findings of this study, the following recommendations are suggested to the Government of Nigeria, through the Federal and State Ministries of Justice, Labour and Employment, Education, Health, Women Affairs and Social Development, and Information and Culture: (i) the Child’s Rights Act (2003) should be enforced in all states across the country (ii) the Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018 should be mandated into recruitment and employment policies across public and private sectors (iii) school administrators at all levels should adopt inclusive learning practices (vi) learning curriculum in primary and secondary education should include disability awareness so that school children can learn the importance of empathy and tolerance towards their peers with albinism (v) all teachers must complete disability diversity awareness training (vi) all teachers must complete cultural awareness training (vii) antenatal care should include couples counselling on hereditary and congenital conditions and provide postpartum support for coping with unexpected pregnancy outcomes (viii) continual mass orientation on albinism through radio and television (ix) recurrent grassroot orientation targeted at breaking unhealthy adherence to negative cultural beliefs on albinism (x) custodians of religious faiths to use their platform and influence to demystify albinism particularly to improve parental and familial attitude towards albinism and other disabilities.

The closing point for consideration argues that adoption of the above recommendations will help social institutions in Nigeria to enable persons with albinism to thrive and reach their full potential.

Authors’ contributions

AO proposed the research and conducted all interviews. MM and GB provided guidance on research governance and data analysis. AO, MM, and GB wrote the paper. LT proofread and helped to edit the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Mr Jake Epelle, founder of The Albino Foundation (TAF Africa), Chief Adeyemi Dada, founder of The Albino Network Association (TANA) and all members for allowing us to identify with their struggle for full social inclusion in Nigeria.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdulrahman, Hadiza. 2023. “Inclusive Education for Children with Albinism.” Radio Nigeria, September 18, 2023. https://radionigeria.gov.ng/2023/09/18/inclusive-education-for-children-with-albinism/#:∼:text=The%20existing%20blueprint%20has%20done,the%20pervasive%20misinformation%20about%20albinism.

- Aborisade, Richard A. 2021. “Why Always Me?’ Childhood Experiences of Family Violence and Prejudicial Treatment Against People Living with Albinism in Nigeria.” Journal of Family Violence 36 (8): 1081–1094. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00264-7.

- Aborisade, Richard A. 2022. “Two People and One Albino! Accounts of Discrimination, Stigmatization, and Violence against People Living with Albinism in Nigeria.” Journal of Human Rights and Social Work 7 (3): 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-022-00214-3.

- Adelakun, Olanike Sekinat, and Mary-Ann Ajayi. 2020. “Eliminating Discrimination and Enhancing Equality: A Case for Inclusive Basic Education Rights of Children with Albinism in Africa.” Nigerian Journal of Medicine 29 (2): 244–251. https://doi.org/10.4103/NJM.NJM_50_20.

- Adenekan, Tolulope Elizabeth. 2019. “Information Needs of Albinos in the Yoruba Ethnic Group, Nigeria.” International Journal of Technology and Inclusive Education 8 (1): 1385–1393. https://doi.org/10.20533/ijtie.2047.0533.2019.0169.

- Agbo, Christian. 2023a. “Able to Serve Campaign: PDP Backs TAF-Africa’s Call for Appointment of PWDs as Ministers, Commissioners.” Qualitative Magazine, May 5, 2023. https://qualitativemagazine.com/able-to-serve-campaign-pdp-backs-taf-africas-call-for-appointment-of-pwds-as-ministers-commissioners/.

- Agbo, Christian. 2023b. “NCPWD Endorses TAF Africa’s Able to Serve Campaign.” Qualitative Magazine, April 27, 2023. https://qualitativemagazine.com/ncpwd-endorses-taf-africas-able-to-serve-campaign/.

- Agbo, Ogechi Florence, and Ingo Plag. 2020. “The Relationship of Nigerian English and Nigerian Pidgin in Nigeria: Evidence from Copula Constructions in Ice-Nigeria.” Journal of Language Contact 13 (2): 351–388. https://doi.org/10.1163/19552629-bja10023.

- Ajose, Frances, and Olufolake Cole. 2019. “Where Do Nigerian Albinos Come From? An Observational Cohort Study.” LASU Journal of Health Sciences 2 (1): 1–7.

- Amnesty International. 2017. “The Ritual Murders of People with Albinism in Malawi.” In Individuals at Risk. London: Amnesty International UK.

- Amucheazi, C., and C. M. Nwankwo. 2020. “Accessibility to Infrastructure and Disability Rights in Nigeria: An Analysis of the Potential of the Discrimination Against Persons with Disability (Prohibition) Act 2018.” Commonwealth Law Bulletin 46 (4): 689–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050718.2020.1781674.

- Anele, Douglas. 2019. “Notes on the 2019 International Albinism Awareness Day (1).” Vanguard. https://www.vanguardngr.com/2019/06/notes-on-the-2019-international-albinism-awareness-day-1/.

- Aquaron, R., M. Djatou, and L. Kamdem. 2009. “Sociocultural Aspects of Albinism in Sub-Saharan Africa: Mutilations and Ritual Murders Committed in East Africa (Burundi and Tanzania).” Medecine Tropicale: Revue du Corps de Sante Colonial 69 (5): 449–453.

- Arimoro, Augustine Edobor. 2019. “Are They Not Nigerians? The Obligation of the State to End Discriminatory Practices Against Persons with Disabilities.” International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 19 (2): 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1358229119846764.

- Audu, Ishaq A., Suleiman H. Idris, Victor O. Olisah, and Taiwo L. Sheikh. 2013. “Stigmatization of People with Mental Illness among Inhabitants of a Rural Community in Northern Nigeria.” The International Journal of Social Psychiatry 59 (1): 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764011423180.

- Barnicot, N. A. 1952. “Albinism in South-Western Nigeria.” Annals of Eugenics 17 (Part 1): 38–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1809.1953.tb02535.x.

- Benyah, Francis. 2017. “Equally Able, Differently Looking: Discrimination and Physical Violence Against Persons with Albinism in Ghana.” Journal for the Study of Religion 30 (1): 161–188. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3027/2017/v30n1a7.

- Bradbury-Jones, Caroline, Peter Ogik, Jane Betts, Julie Taylor, and Patricia Lund. 2018. “Beliefs About People with Albinism in Uganda: A Qualitative Study Using the Common-Sense Model.” PloS One 13 (10): e0205774. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205774.

- British Broadcasting Corporation. 2014. “Tanzania’s Albino Community: "Killed Like Animals”. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-30394260.

- Brydges, Colton, and Paul Mkandawire. 2017. “Perceptions and Concerns About Inclusive Education Among Students with Visual Impairments in Lagos, Nigeria.” International Journal of Disability, Development & Education 64 (2): 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2016.1183768.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 1995. “The Body, Identity, and Self: Adapting to Impairment.” The Sociological Quarterly 36 (4): 657–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1995.tb00459.x.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2002. “The Self as Habit: The Reconstruction of Self in Chronic Illness.” OTJR: Occupation, Participation & Health 22 (1_suppl): 31S–41S. https://doi.org/10.1177/15394492020220S105.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2005. “Review of Grounded Theory in the 21st Century: Applications for Advancing Social Justice Studies.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin, and Y. S. Lincoln, 507–535. CA: SAGE Ltd.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2007. “Review of Constructionism and Grounded Theory.” In Handbook of Constructionist Research, edited by J. A. Holstein, and J. F. Gubrium, 319–412. New York: Guilford.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2011. “Grounded Theory Methods in Social Justice Research.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin, and Y. S. Lincoln, 359–380. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Ltd.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, Inc.

- Dey, Ian. 1999. Grounding Grounded Theory: Guidelines for Grounded Theory Inquiry. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Duri, F., and A. Makama. 2018. “Disabilities and Human Insecurities: Women and Oculocutaneous Albinism in Postcolonial Zimbabwe.” In Rethinking Securities in an Emergent Techno-Scientific New World Order: Retracing the Contours for Africa’s Hi-Jacked Futures. Makon. Bamenda: Langaa Research & Publishing CIG.

- Epelle, Jake. 2022. “Inclusive Schools, Not Special Schools, Will Deliver Quality Education for Children with Disabilities.” In News Agency of Nigeria’s Forum Flagship Platform, edited by Isaiah Ude. Abuja: BONews Service.

- Estrada-Hernández, N., and D. C. Harper. 2007. “Research on Psychological and Personal Aspects of Albinism: A Critical Review.” Rehabilitation Psychology 52 (3): 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.52.3.263.

- Etieyibo, E., and O. Omiegbe 2016. “Religion, Culture, and Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities in Nigeria.” African Journal of Disability 5 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v5i1.192.

- Etieyibo, E., and O. Omiegbe. 2021. “People with Disabilities in the Margins in Nigeria.” Africa Review 13 (3): S17–S30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09744053.2020.1812040.

- Ezeilo, B. N. 1989. “Psychological Aspects of Albinism: An Exploratory Study with Nigerian (Igbo) Albino Subjects.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 29 (9): 1129–1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(89)90026-9.

- Federal Ministry of Education. 2019. “National Policy on Albinism in Nigeria”. https://education.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/REVIEWED-NATIONAL-POLICY-ON-ALBINISM-DESIGNED.pdf.

- Federal Republic of Nigeria. 2019. “Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act 2018.” In Fgp 59/052019/1 50. Lagos: The Federal Government Printer.

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Touchstone.

- Holzinger, Andrea, Ursula Komposch, Gonda Pickl, and Martin Hochegger. 2023. “Education for Children with Albinism in Tanzania. A Cooperation Project of the University College of Teacher Education Styria and the University of Moshi.” In Internationalisation and Professionalisation in Teacher Education: Challenges and Perspectives, edited by Heiko Haas-Vogl, Oliver Holz, and Susanne Linhofer, 93–104. Graz-Wien: Leykam University Press. https://doi.org/10.56560/isbn.978-3-7011-0511-3_7.

- Ikuomola, A. D. 2015a. “We Thought We Will Be Safe Here’: Narratives of Tanzanian Albinos in Kenya and South-Africa.” African Research Review 9 (4): 37–54. https://doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v9i4.4.

- Ikuomola, A. D. 2015b. “Socio-Cultural Conception of Albinism and Sexuality Challenges among Persons with Albinism (PWA) in South-West, Nigeria.” AFRREV IJAH: An International Journal of Arts and Humanities 4 (2): 189–208. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijah.v4i2.14.

- Ikuomola, A. D. 2019a. “Beyond Asexualization: Narratives of Sexual Objectification of Persons with Albinism in Nigeria.” Issues in Ethnology and Anthropology 14 (1): 223–245. https://doi.org/10.21301/eap.v14i1.9.

- Ikuomola, A. D. 2019b. “The Misconception of Albinism (Causes and Curses): Implication on Women with Albinism Invisibility in Public Health Care Centres in Nigeria.” Studia Sociologica 1: 167–182. https://doi.org/10.24917/20816642.11.1.10.

- Imafidon, Elvis. 2020. “Some Epistemological Issues in the Othering of Persons with Albinism in Africa.” In: Imafidon, E. (eds) Handbook of African Philosophy of Difference. Handbooks in Philosophy: 361–378. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14835-5_18.

- Inclusive News Network. 2023. “Disability Activist Advocates Inclusive Education for Children with Albinism.” Albinism News. https://inclusivenews.com.ng/disability-activist-advocates-inclusive-education-for-children-with-albinism/.

- Juvonen, J., L. M. Lessard, R. Rastogi, H. L. Schacter, and D. S. Smith. 2019. “Promoting Social Inclusion in Educational Settings: Challenges and Opportunities.” Educational Psychologist 54 (4): 250–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1655645.

- Kanyungo, V. M., and A. Penda. 2021. “Challenges Pupils with Albinism Face in Selected Schools of Luapula Province, Zambia.” International Journal of Research & Innovation in Social Science V VIII: 395–401.

- Kiluwa, S. H., S. Yohani, and S. Likindikoki. 2022. “Accumulated Social Vulnerability and Experiences of Psycho-Trauma Among Women Living with Albinism in Tanzania.” Disability & Society 39 (2): 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2022.2072706.

- Lazarus, Richard, and Folkman Susan. 1984. Stress, Appraisal & Coping. New York: Springer.

- Likumbo, Naomi, Tania De Villiers, and Una Kyriacos. 2021. “Malawian Mothers’ Experiences of Raising Children Living with Albinism: A Qualitative Descriptive Study.” African Journal of Disability 10: 693. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v10i0.693.

- Liu, Siyin, Helen J. Kuht, Emily Haejoon Moon, Gail D. E. Maconachie, and Mervyn G. Thomas. 2021. “Current and Emerging Treatments for Albinism.” Survey of Ophthalmology 66 (2): 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2020.10.007.

- Lynch, P., P. Lund, and B. Massah. 2014. “Identifying Strategies to Enhance the Educational Inclusion of Visually Impaired Children with Albinism in Malawi.” International Journal of Educational Development 39: 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.07.002.

- Machingambi, Margaret. 2023. “Exploring Barriers to Learning Hindering Learners with Albinism’ Academic Achievement at Schools in the Masvingo District in Zimbabwe.” International Journal of Studies in Psychology 3 (1): 28–37. https://doi.org/10.38140/ijspsy.v3i1.901.

- Machoko, C. G. 2013. “Albinism: A Life of Ambiguity–A Zimbabwean Experience.” African Identities 11 (3): 318–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2013.838896.

- Masanja, M. M., M. M. Imori, and I. J. Kaudunde. 2020. “Factors Associated with Negative Attitudes towards Albinism and People with Albinism: A Case of Households Living with Persons with Albinism in Lake Zone, Tanzania.” Open Journal of Social Sciences 08 (04): 523–537. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.84038.

- Mather, L., Thavanesi Gurayah, Deshini Naidoo, Henna Nathoo, Fortune Feresu, Nhlanhla Dlamini, Trinity Ncube, and Zuleika Patel. 2020. “Exploring the Occupational Engagement Experiences of Individuals with Oculocutaneous Albinism: An EThekwini District Study.” South African Journal of Occupational Therapy 50 (3): 52–59. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2020/vol50no3a6.

- Matthew, Miles, and Huberman Michael. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Incorporated.

- Maunganidze, Farai, Kudakwashe Machiha, and Mapuranga Mapuranga. 2022. “Employment Barriers and Opportunities Faced by People with Albinism. A Case of Youths with Albinism in Harare, Zimbabwe.” Cogent Social Sciences 8 (1): 2092309. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2092309.

- Meddeb, M. 2016. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Protecting and Empowering Children with Albinism in Schools. Kinshasa: United Nations Children’s Fund.

- Miles, Susie. 2011. “Exploring Understandings of Inclusion in Schools in Zambia and Tanzania Using Reflective Writing and Photography.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 15 (10): 1087–1102. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.555072.

- Moradi, B., and Y. Huang. 2008. “Objectification Theory and Psychology of Women: A Decade of Advances and Future Directions.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 32 (4): 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x.

- Mtonga, Thomas, Esther Lungu, Kalisto Kalimaposo, and Joseph Mandyata. 2021. “Exclusion in Inclusion: Experiences of Learners with Albinism in Selected Mainstream and Special Schools in Zambia.” European Journal of Special Education Research 7 (1): 162–181. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejse.v7i1.3638.

- Mtonga, Thomas, Kalisto Kalimaposo, and Joseph Mandyata. 2023. “Classroom Experiences of Learners with Albinism in Selected Regular and Special Education Schools in Zambia.” International Journal of Social Science and Education Research STUDIES 03 (01): 120–129. https://doi.org/10.55677/ijssers/V03I1Y2023-15.

- Mwiba, Denis Mwanyanja. 2018. “Medicine Killings, Abduction of People with Albinism, Wealth and Prosperity in North Malawi: A Historical Assessment.” Proceedings of the African Futures Conference 2 (1): 30–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2573-508X.2018.tb00008.x.

- National Assembly of The Federal Republic of Nigeria. 2003. “Child’s Rights Act 2003.” In Act No. 26. https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5568201f4.pdf.

- National Commission for Persons with Disabilities. 2021. Disability Inclusion Assessment and Diagnostic Tool. Abuja: Africa Polling Institute. https://ncpwd.gov.ng/pdfs/11document.pdf.

- National Human Rights Commission. 2023. “Child Rights.” Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.nigeriarights.gov.ng/focus-areas/child-rights.html.

- Nikolaou, Vasiliki, Alexander J. Stratigos, and Hensin Tsao. 2012. “Hereditary Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer.” Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 31 (4): 204–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sder.2012.08.005.

- Njoku, Ju, and N. Amadi Cajetan. 2020. “Original Research Article Psycho-Social Dimensions of Stigmatisation of Albinos in Rivers State and the Challenges of Learning among Students with Albinism (SWA).” Journal of Advances in Education and Philosophy 04 (04): 155–159. https://doi.org/10.36348/jaep.2020.v04i04.003.

- Nwosu, K. C., C. G. Unachukwu, V. C. Nwasor, and A. O. Ezennaka. 2019. “Teaching Children with Albinism in Nigerian Regular Classrooms: An Examination of the Contextual Factors.” Journal of Advocacy, Research & Education 6 (2): 4–16.

- Ojilere, A., and M. M. Saleh. 2019. “Violation of Dignity and Life: Challenges and Prospects for Women and Girls with Albinism in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of Human Rights and Social Work 4 (3): 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-018-0085-0.

- Okafor, Ifeoma P., Damilola V. Oyewale, Chidumga Ohazurike, and Adedoyin O. Ogunyemi. 2022. “Role of Traditional Beliefs in the Knowledge and Perceptions of Mental Health and Illness Amongst Rural-Dwelling Women in Western Nigeria.” African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine 14 (1): e1–8–e8. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v14i1.3547.

- Okoro, A. N. 1974. “Albinism in Nigeria: A Clinical and Sociological Study.” British Journal of Dermatology 91 (s10): 24–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1974.tb12489.x.

- Olaitan, Muhammed Faisol. 2023. “Social Constructions of Disabled Women and Their Implications for Their Wellbeing in Lagos, Nigeria.” African Identities 21 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2023.2207763.

- Ololajulo, E. T., and S. A. Omotoso. 2023. “The Double Jeopardy of Women with Albinism in Ibadan, Nigeria: Breaking the Unemployment Barrier.” Disability & Society 39 (7): 1747–1764. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2022.2164705.

- Omobowale, Ayokunle Olumuyiwa, and Akinpelu Olanrewaju Olutayo. 2009. “The Sanctity of the ‘White Skin’ in Yoruba Belief System.” Journal of Environment and Culture 6 (1–2): 112–122.

- Partners West Africa Nigeria. 2023. Child Rights Act Tracker. Rule of Law and Empowerment Initiative. https://www.partnersnigeria.org/childs-rights-law-tracker/.

- Phatoli, Relebohile, Nontembeko Bila, and Eleanor Ross. 2015. “Being Black in a White Skin: Beliefs and Stereotypes Around Albinism at a South African University.” African Journal of Disability 4 (1): 106. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v4i1.106.

- Reimer-Kirkham, S., Barbara Astle, Ikponwosa Ero, Kristi Panchuk, and Duncan Dixon. 2019. “Albinism, Spiritual and Cultural Practices, and Implications for Health, Healthcare, and Human Rights: A Scoping Review.” Disability & Society 34 (5): 747–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1566051.

- Saad, N., A. Hot, J. Ninet, A. Claudy, and M. Faure. 2007. “Acquired Hypertrichosis Lanuginosa and Gastric Adenocarcinoma.” Annales de Dermatologie & de Vénéréologie 134 (1): 55–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0151-9638(07)88991-5.

- Saka, Bayaki, Abas Mouhari-Toure, Saliou Adam, Garba Mahamadou, Panawè Kassang, Julienne N. Teclessou, Séfako A. Akakpo, et al. 2020. “Dermatological and Epidemiological Profile of Patients with Albinism in Togo in 2019: Results of Two Consultation Campaigns.” International Journal of Dermatology 59 (9): 1076–1081. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.15069.

- Sayfulloevna, Salimova Shahlo. 2023. “Safe Learning Environment and Personal Development of Students.” International Journal of Formal Education 2 (3): 7–12.

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet M. Corbin. 1990. “Basics of Qualitative Research.” Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Incorporated.

- TAF Africa. 2023. “Able to SERVE”. https://youtu.be/8pg3c32uapI.

- Taylor, J., C. Bradbury-Jones, and P. Lund. 2019. “Witchcraft‐Related Abuse and Murder of Children with Albinism in Sub‐Saharan Africa: A Conceptual Review.” Child Abuse Review 28 (1): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2549.

- Thomas, C. 1999. Female Forms: Experiencing and Understanding Disability. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Thomas, C. 2003. “Developing the Social Relational in the Social Model of Disability: A Theoretical Agenda.” In Implementing the Social Model of Disability: Theory and Research, edited by C. Barnes, and G. Mercer. Leeds: The Disability Press.

- Torgbenu, E. L., O. S. Oginni, M. P. Opoku, W. Nketsia, E. Agyei-Okyere, and Elvis Agyei-Okyere. 2021. “Inclusive Education in Nigeria: Exploring Parental Attitude, Knowledge and Perceived Social Norms Influencing Implementation.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 25 (3): 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1554715.

- United Nations Population Fund. 2024. “Review of World Population Dashboard.” United Nations Population Fund. https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population-dashboard.

- United Nations. 2007. "Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/resources/general-assembly/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-ares61106.html.

- United Nations. 2023. "Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities." United Nations Treaty Collections. https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=iv-15&chapter=4&clang=_en.

- Wengraf, T. 2004. The Biographic-Narrative Interpretative Method: Short Guide. 23rd ed. Middlesex: Middlesex University.