Abstract

The article provides a contemporary evaluation of Turkish drug-control policy. Turkish drug-control policy is heavily predicated on deterrence-based supply-side policies to the neglect of a holistic strategy that sufficiently addresses supply and demand reduction. The article explores recent subtle trends in drug-control policy to assert that the Turkish government fails to develop appropriate and effective policies in response to the illicit drug issue. In addition, the article identifies and discusses the current political debates and legislative developments that inform the policy preferences of the Turkish authorities. The article concludes that policy failures, combined with the external challenges presented by Syrian refugees and the ongoing insurgency by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), will result in a substantial prevalence of, and an increase in, drug use and drug-related deaths despite increases in seizure rates, criminal justice cases, and prison population and parolees unless Turkish authorities develop an evidence-based drug-control policy.

Introduction

This article aims to assess the overall Turkish drug-control policy, with a particular emphasis on identifying the policy’s strengths and weaknesses and proposing evidence-based policy changes. In doing so, we first analyse relevant dataFootnote1 on both the supply and demand sides to identify recent trends in drug policy that prioritise supply reduction over demand reduction. Then we discuss the factors that have shaped Turkey’s drug-control policy as we observe it today, encompassing both the supply and the demand sides of the problem. Finally, taking into account recent political developments that could aggravate the illicit drug situation in Turkey, such as the Syrian War and the intensified conflict with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), we propose ameliorative policy recommendations.

The legal and illegal drug business has a long history in the Turkish states. After the invention and use of opium for health purposes, Anatolia became a linchpin of opium production and trade. The Ottoman Empire inherited the opium trade from the Byzantine Empire and held that trade through its collapse. The new state that eventually arose from the Ottoman ashes – the Republic of Turkey – has continued to produce and trade opium up until today. Since the foundation of the new republic in 1923, the illicit opium issue has been a major international agenda item for Turkey (Erdinç, Citation2004). Turkey has, however, made reforms and established infrastructures to control opium diversion. While once the main worldwide supplier of illicit heroin to a licit producer of opium in the 1970s, Turkey now produces approximately one-third of global legal opium demand without any leakage (Ekici & Unlu, Citation2013; Windle, Citation2011, 2013b).

Despite its success in controlling the diversion of licit opium to illicit markets, Turkey continued to receive international attention and criticism in the 1980s, this time as a transit country rather than a source. Because precautions against opium diversion have made the Turkish opium supply more expensive and reduced its availability, traffickers have turned their attention to Southeastern Asian countries such as Afghanistan and Pakistan, where the supply is more available and cheaper (Windle, Citation2011, 2013a). Parallel to the increase in demand in European countries in the 1980s, Turkey, due to its geographic position as a bridge between Asia and Europe, continued to serve as the heart of heroin trafficking from Afghanistan, the main supplier of heroin, to Europe, where the demand is high (Robins, Citation2008). In response, international focus shifted from preventing opium’s illicit production and diversion to controlling transnational opium and heroin trafficking (Windle, Citation2013a).

The Turkish state has strengthened its interdiction capacity over the last two decades, which can be seen as an organisational learning period of government actors (Windle, Citation2013b). Turkey has consistently ranked among the countries making the highest number of illicit drug seizures, predominantly of Afghan heroin destined for Europe. Turkish law enforcement forces now consistently make the second highest number of illicit drug seizures annually, after Iran; in some years, the number of Turkish seizures has exceeded that of Iranian seizures (Ekici & Unlu, Citation2013). The trafficking route used is the main variable predicting the number of seizures. The number of annual seizures in Turkey is highly correlated (r = 0.93) with the amount of annual opium production taking place in Afghanistan, as predicted by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Afghan heroin arrives in Turkey a year after the opium is harvested in Afghanistan (Ekici & Coban, Citation2014). Iranian drug syndicates play an important role in the trafficking of opium from Afghanistan to Turkey. Turkish crime syndicates purchase heroin from Iranian syndicates (Ekici & Coban, Citation2014; Ekici & Unlu, Citation2013).

Turkey was once known only as a heroin transit route; it has also become a target for cocaine, Ecstasy, synthetic cannabinoids, and other designer drugs due to an increase in demand (Unlu & Ekici, Citation2012). Seizures of these drugs have consequently increased in the last decade – in the past five years, seizures have increased by approximately 5-fold for cocaine, 10-fold for Ecstasy and 18-fold for synthetic cannabinoid (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2014). While no study to date has discussed the underlying factors in this seizure increase, Routine Activity Theory (Cohen & Felson, Citation1979) suggests that the increase in drug use could be attributed to changes in the social settings of the new generation resulting from the economic and democratic developments of the 2000s. During this period, the number of universities, bars, and discos increased, facilitating a change in the routine activities and lifestyles of Turkish youth and providing them with increased opportunities to use drugs.

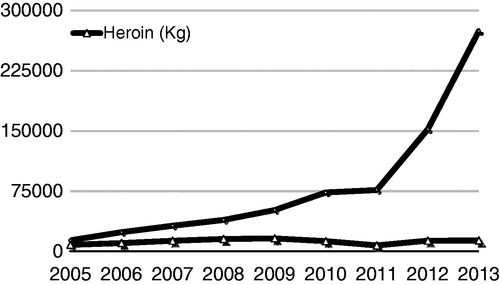

Cannabis cultivation has evolved and expanded across the industrialised world (Decorte & Potter, Citation2015; Potter, Bouchard, & Decorte, Citation2013). Turkey did not remain aloof from this phenomenon. Cannabis is the most prevalent substance among drug users in Turkey (Pumariega, Burakgazi, Unlu, Prajapati, & Dalkiliç, Citation2014; Ünlü & Evcin, Citation2014); its production has increased significantly, but the cannabis produced in Turkey appears only to be consumed domestically, with no reported international trafficking incidence (). Turkey continues to seize not only the largest quantity of heroin but also the largest quantity of cannabis in Europe. In 2004, 9390 kilograms of cannabis were captured; after 10 years, a 29-fold increase (274,380 kg) was reported (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2014).

An international issue becomes a domestic problem

The drug issue has also become a social problem in Turkey over the past two decades. Despite their availability, opium and heroin consumption have traditionally very low among Turkish youth for decades – a plausible explanation for Turkey’s historical reluctance to suppress the heroin trade. Recently, however, new designer drugs such as Ecstasy and synthetic cannabinoids have rapidly become popular. In addition, there are reports that the use of stimulants, cannabis, and synthetic cannabinoids among youth is increasing sharply (Ünlü & Evcin, Citation2014; Ünlü, Evcin, Dalkilic, & Pumariega, Citation2013). Despite the reported steep increase, no reliable national estimate of drug use trends exists, due to a lack of longitudinal data collected from nationally representative samples. Moreover, in the absence of reliable estimates, it is difficult to rule out other plausible theories such as increased police attention which might explain the increase in drug use statistics. Nevertheless, the exponential increase in drug use statistics as corroborated by the treatment demand statistics we report below lead us to believe that the statistics reported, to a large extent, are the product of actual increase in drug use.

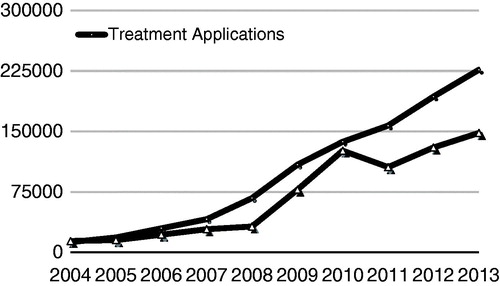

The increase in drug use among youth was followed over the next years by a concomitant increase in the number of police arrests, as well as increased treatment demand. As seen in , there was an approximately 18-fold increase in treatment demand and a 10-fold increase in drug-related police arrests from 2004 to 2013. Treatment demand increased from 12,656 cases in 2004 to 226,471 cases in 2013; drug-related arrests increased in number from 14,009 in 2004 to 148,121 in 2013 (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2011,Citation2012, Citation2013,Citation2014).

Despite the increasing levels of illicit drug use in Turkey, the country’s treatment and rehabilitation capacity appears weak; few drug treatment centres exist. Although only 12 hospitals provided inpatient treatment services, with an approximately 480-bed capacity, in 2004, treatment capacity increased to 26 hospitals with 706 beds in 2013 (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2014). Access to inpatient treatment services appears currently to be a privilege available only to a minority of drug addicts. Only 1 out of 28 drug users (7897 applicants out of 226,471) had access to inpatient services in 2013. In addition to the insufficiency of treatment services, the poor quality of the services available contributes to drug addiction treatment’s ineffectiveness.

Moreover, no operational rehabilitation centre is currently available to provide psychological counselling service to drug users and reintegrate them into society. The insufficiency of treatment and rehabilitation services results in more problematic drug use and an increase in drug-related deaths. The figures reported in national drug reports indicate that drug-related deaths have seen a steady increase in the last decade. In 2004, 29 drug-related deaths (both direct and indirectFootnote2 ) were recorded; the number increased to 648 in 2013, a surge of approximately 22-fold (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2011,Citation2012, Citation2013,Citation2014).

The failure of Turkish drug-control policy is also evident in the nation’s criminal justice system. Both public-order offences and drug offences have increased in number in the past decade. The figures indicate a sharp increase in the ratio of drug-related offences to other types of offences among the prison population. Although drug offenders constituted just 1 out of 12.7 (4348 out of 55,609) members of the prison population in 2001, the ratio rose to 1 out of 8.6 (10,533 out of 90,837) in 2007 and 1 out of 5.8 (24,890 out of 145,478) in 2013 according to national drug reports (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2011,Citation2012, Citation2013,Citation2014). It is also important to keep in mind that the figures created after 2005 show only drug-trafficking-related offences among inmates, because the government enacted reforms in 2005 in compliance with the European Union (EU) membership process. These reforms involved the introduction of the parole system to the Turkish criminal justice system; thereafter, drug possession cases were directed to the parole system. The figures on drug-related police arrests indicate an approximately 10-fold increase in arrests over the last decade. Only 14,009 people were arrested on drug charges in 2004; this figure increased to 148,121 in 2013 (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2011,Citation2012, Citation2013,Citation2014). While this increase might simply indicate increased police attention and activity, the magnitude of the increase might plausibly suggest a significant prevalence in street-level dealing.

What do those figures tell us about the drug situation in Turkey? A number of conclusions can be drawn. First, it can be concluded that drug use is growing more and more prevalent in Turkey, as evidenced by the sharp increases noted in drug seizures, treatment demand, and police arrests. Official figures on drug-related deaths and prison populations, not shown here to preserve space, provide further support for this conclusion. Second, Turkey is continuing to strengthen its interdiction and enforcement capabilities. Turkey continues to seize large amounts of drugs and is making more drug-trafficking-related arrests. Third, Turkey’s addiction treatment capacity appears to lag behind need. In the next section, we aim to explore why Turkish policy makers prefer supply-side efforts such as interdiction and law enforcement to other social policies such as the provision of treatment services.

Policy formulation

The public-policy-making process is a core element of democratic development. It is expected that before designing a policy, power elites will include different stakeholders in the decision-making process and utilise evidence-based frameworks rather than relying on ideological and political views when dealing with a social problem. Since drug policy is a multi-dimensional and complicated social problem that requires unique contributions from the health, criminal justice, education, and welfare domains, experts generally dominate drug-control policy (Singleton & Rubin, Citation2014).

Political parties are more influential than the bureaucracy and non-governmental organisations in the Turkish policy-making process. Turkey’s background in the strongly centralised Ottoman Empire enabled bureaucracy to become a firmly entrenched institution until the 1970s; however, the introduction of the multi-party system eroded the bureaucracy’s authority and prestige (Robins, Citation2009). Moreover, the Turkish bureaucracy was seen as a repository of political goods with which to reward political party members and supporters. The policy-making process is therefore vulnerable to the narrow and partisan interests of the political entities. Drug policy is mainly shaped by monolithic state and top-down political authority (Robins, Citation2009).

One of the weaknesses of policy making in Turkey has related to the intermittent political instability occurring between 1960 and 2002. A series of coup d'états, coalition governments, and the discontinuous governance associated with short-lived governments has resulted in poor policy design. International pressure during this era pressed Turkish drug-control policy towards a focus on the supply side of the drug problem. On the other hand, urbanisation, modernisation, and political conflicts have led to disregard of the demand side of the problem. Drug use came to the public’s attention only when a famous figure died from an overdose (Işik, Citation2013). Having discussed the limitations of general policy making in Turkey, the next sections will elaborate on the supply and demand sides of drug-control policies.

Supply-side policies

Turkish drug-control policy relies primarily upon supply-reduction policies due to a number of factors: international pressure and national prestige, the nexus between drugs and the financing of terrorism and the implications of that connection for state security, and the impact of organised criminal groups on political instability. We will discuss each of these factors below. Turkey historically has been under significant international pressure to strengthen its opium-control and counter-narcotics capacity (Robins, Citation2008; Windle, Citation2013a, 2013b) – pressure that resulted in corresponding institutional, legislative, and policy changes in the 70s. More recently, Turkey established the Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime Department (KOM) in 1983 and continued reforms in Police, Gendarmerie, and Customs at the institutional level; Turkey also made reforms at the personnel-policy, regulations, and technological-capacity levels. For instance, the first legislation (Law Number 4208) in the area of money laundering was enacted in 1996, the first controlled delivery operation took place in 1997, and the first wiretap evidence sharing took place between Germany and Turkey in 2001 (Robins, Citation2008). Turkey has ratified the United Nations (UN) conventions (1961, 1971, and 1988) in order to comply with the international standards in drug policy (Akgul & Gurer, Citation2014).

According to Robins, the ruling elites of Turkey aim to paint a picture of Turkey that downplays any identity it may have as a drug-consumer country (Robins, Citation2008), focussing attention on international drug trafficking and international cooperation as a “core indicator of Turkey’s standing as a good international citizen” (p. 632). Despite the focus on supply-side strategies, Turkey has been reluctant to adopt modern law enforcement strategies such as those designed to target money laundering (Robins, Citation2008). With the exception of a couple of ostensible charges, the Financial Crimes Investigation Board (MASAK), the gatekeeper of the financial system, has been unable to deter drug traffickers from money laundering (Ekici, Citation2014). Dursun (Citation2005) claimed that the political structure in Turkey does not favour the development of a transparent financial system because such a system would hinder political financing. Political parties depend heavily on interest groups that provide them with substantial financial support for elections. These parties and interest groups are unwilling to take precautions that would enable the monitoring of their financial activities. The resulting weak financial structure for identifying suspicious financial activities, together with slow asset-freezing procedures, facilitates criminals’ money-laundering activities (Dursun, Citation2005).

The European countries’ international cooperation demands, particularly relating to the trafficking of heroin from Afghanistan, drive Turkey’s prioritisation of supply reduction. Turkey is on the natural route from Afghanistan, the main source of heroin, to Europe, where the demand for heroin is high. In addition to its concern for being a contributing member of the international community to the struggle against transnational crimes, Turkey strives to meet the demands for international cooperation to counter transnational drug trafficking. International cooperation between countries – particularly the leading countries in supply-reduction efforts in source countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the Netherlands – is typically carried out through liaison officers seconded to other countries temporarily to facilitate information sharing and coordinate common efforts such as controlled delivery operations. These officers are active and important while processing criminal intelligence sharing (Block, Citation2010). Liaison officers for countries leading the supply-reduction are based in Ankara. The number of liaison officers in Turkey has increased in the last decade because the Turkish National Police have become more willing to share information (Kaçakçilik ve Organize Suçlarla Mücadele Daire Baskanligi, Citation2015).

In addition to international pressure, national security concerns are a factor encouraging supply-side drug policy formulation. Transnational drug traffickers pose a serious threat to national security with their tremendous turnover, connections with terrorist organisations, and corruption capacity (Cevik, Citation2013; Ekici, Citation2014). This threat exists not only against institutions and people but also against territorial integrity and system of rule.

Drug trafficking is highly profitable. It is estimated that drug traffickers generate approximately $15 billion annually in Turkey. An illicit market of this size attracts the attention of terrorist organisations (with exceptionsFootnote3 ) striving to finance their activities (Ekici, Citation2014; Roth & Sever, Citation2007). In addition to the Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP-C), the PKK, the infamous Kurdish insurgency organisation, utilises drug trafficking as a source of income. The PKK has been involved in heroin trafficking through the so-called “taxation”, smuggling, refining and producing (particularly in the 1990s), and distribution of the heroin along the route from Turkey to European countries (Ekici, Citation2014; Laciner, Citation2008; Robins, Citation2008). The PKK is accountable for approximately 50–80% of the heroin supply in Europe (Ekici, Citation2014; Roth & Sever, Citation2007).

A strong kin-based social structure among Kurds facilitates the formation of organised crime syndicates in southeastern Turkey. Clan ties enable them to extend their networks not only within the country but also across borders (Ekici, Phil, & Ayhan, Citation2012). The existence of Kurdish immigrants in European countries facilitates their drug-trafficking activities. Turkey-based drug trafficking groups operate easily in some European countries, such as Germany, Sweden, Britain and the Netherlands (Robins, Citation2008; Roth & Sever, Citation2007). In addition to heroin trafficking, the PKK plays an increasing role in cannabis cultivation in some parts of southeastern Turkey. The PKK has been estimated to generate approximately $400 million from cannabis cultivation and distribution within Turkey (Ekici, Citation2014).

The Resolution Process with the PKK, initiated by the Turkish government after 2010, decreased the formal control mechanism of law enforcement in the southeastern region. The initiation has resulted in a sharp increase in both cannabis cultivation and the amount seized (Akgül & Yilmaz, Citation2015); it is important to note that this increase could be attributed partly to increased law enforcement attention to cannabis trafficking. Cannabis consumed in Turkey is largely cultivated domestically through traditional cultivation methods. Turkish cannabis is not known to be trafficked internationally, but existing heroin-trafficking networks may facilitate the adaptation of local farmers to the European cannabis market, giving them the knowledge to take up modern production methods that increase fertility and enabling them to export their product to Europe through existing trafficking networks. A similar case was observed with Moroccan cannabis in Europe: Moroccan cultivators changed their production methods to bring their product quality up to that of the European cultivators and regain their share of the cannabis market (Afsahi, Citation2015). The weakness of authority in southeastern Turkey instigated by the Resolution Process may also facilitate heroin traffickers’ activities in the region, which serves as an entrance hub for heroin trafficking from Afghanistan to Europe.

Border security and political conflicts in neighbouring countries are a great risk of Turkey in terms of drug trafficking. Iran is a well-known and -documented gateway for heroin trafficking through Turkey, and the border with Iran is poorly protected due to rugged terrain and the presence of Kurdish insurgence groups in both countries (Ekici & Coban, Citation2014; Ekici & Unlu, Citation2013). A similar trend has also been observed along the Syrian border in recent years (Yayla, Citation2015). For instance, the number of drug-related indictments in Hatay, a province bordering Syria, tripled after the start of political conflict in Syria; the amount seized was 13 times that of the average amount seized in the pre-conflict period (Arslan, Zeren, Celikel, Ortanca, & Demirkiran, Citation2015).

The link between organised crime groups and corruption is a known phenomenon. Moreover, corruption is a primary cause of political instability. Although heroin trafficking and organised crime have in many ways evolved independently from one another, Gingeras (Citation2010a, 2011) claimed that the two phenomena came to overlap in the 1990s in Turkey. Government willingness to fight organised crime in Turkey has fluctuated over the years. It is difficult to understand the nature and importance of the interface between drug trafficking, insurgency and corruption in Turkey in recent decades, even since the end of the Ottoman Empire (Gingeras, Citation2010b; Robins, Citation2008). Robins (Citation2008) asserted that ultranationalist gangs were utilised by the Turkish security elites to prevent assassinations by the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA) and to suppress fundraisers for the PKK insurgency in 1980s and 1990s. The relationship between the Turkish national security state (the so-called “deep state”) and ultranationalist ideological criminal groups brought narco-corruption into the body of the state, unprecedented in the history of Turkey. It has been asserted that the National Intelligence Agency (MİT) employed actors such as Abdullah Çatli for a variety of violent and covert acts in the 1990s. These actors who purportedly served the interests of the state as assassins, however, took advantage of their networking ties and the immunity vested to them by the deep state to engage in drug trafficking as well as other types of organised criminality (Gingeras, Citation2011). The Susurluk scandal of 1996 – which emerged with a car accident that involved a member of Parliament, a right-wing gang leader (Abdullah Çatli) with his partner, and a police bureaucrat in the same vehicle – and subsequent revelations of state collusions with organised crime groups have accelerated the cleanup of the state after 1996 (Cevik, Citation2013). Evidence of state collusion with organised crime has led to the strengthening of the operational capacity of law enforcement in subsequent years (Robins, Citation2008).

A major shift in Turkish law enforcement has occurred, however, particularly in smuggling units, which may affect counter-struggling strategies and results. Reports by the General Directorate of Security and the Department of Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crimes support this argument. The number of operations against serious organised crime groups increased sharply over a four-year period, from 191 in 1997 to 514 in 2001 (Kaçakçilik ve Organize Suçlarla Mücadele Daire Baskanligi, Citation2000, Citation2006). As the operational capacity of law enforcement has increased, the number of crackdown operations on organised crime groups hit a plateau, hovering around 120 charges between 2007 and 2013. This figure fell sharply, however, to 65 cases in 2014 (Kaçakçilik ve Organize Suçlarla Mücadele Daire Baskanligi, Citation2010, Citation2015). This noteworthy decline can be attributed to the absence of government support and the removal of expert and skilled unit commanders and officers from their positions following the December 17/25 Graft Probe, a series of corruption investigations conducted by the police on December 17 and 25, 2013 that implicated three governmental ministers along with several businessmen and other government officers. It should be noted that limited data prevent us from drawing a quick conclusion about how this intervention will affect drug law enforcement results in the long run.

Drug demand-reduction policies

A number of factors have tended to shape Turkish drug demand-reduction policies: the recognition of drug use and addiction as a social problem, the requirements placed on Turkey as part of the accession process to the EU, and media coverage of particular drug-related deaths. The recognition of drug abuse as a social issue requiring governmental attention and intervention occurred first in 1996, following the National Security Council decision to initiate a national demand-reduction programme. The leading agency role was given to the Family Research Institution (FRI), newly founded under the auspices of the Office of the Prime Minister (Robins, Citation2009). However, FRI efforts fell short of making satisfactory progress, and the Turkish National Police assumed the leading agency role at the beginning of the new millennium.

Turkey is in the process of accession to the EU. The EU has significant influence over its member and accession countries regarding the drug policy-making process, capacity building and institutionalisation. Although member states are not obliged to follow a particular policy, the accession process produces similar institutional structures. Because policy transfer relies upon expert interactions at the international level, such interaction engenders a potential to influence state policy process via policy transfer (Eriksen, Citation2007). The majority of member states tend to shape their drug policy from a health framework rather than a criminal-justice paradigm. Policies and practices do, however, vary among member countries (Akgul & Gurer, Citation2014).

The EU accession process has expedited capacity building in Turkish drug-control policy over recent decades. Under the cooperation framework, Turkey transferred not only the institutional structure of the EU, by creating the Turkish Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (TUBİM), but also DCP processes through several twinning projects (Akgul & Gurer, Citation2014; Yildiz & Ünlü, Citation2011). The establishment of the Turkish focal point was itself a twinning project. In contrast to the practice of other European countries, the national focal point for the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) in Turkey, the TUBIM, acts under the umbrella of the Turkish National Police. TUBIM, a law enforcement body, is responsible for the data collection and the coordination of all governmental and non-governmental stakeholders in drug policy making (Evered & Evered, Citation2016). It has been tasked with the formulation of the National Drug Strategy and Action Plan, the National Drug Report, and the reporting of national data to the EMCDDA and the UNODC.

The Europeanisation of Turkish drug policy has facilitated a paradigm shift in Turkish approaches to the drug issue. Although drug-control policy remains an issue controlled at the national, rather than the European, level, Turkey has adopted policies that separate drug dealers from users (Chatwin, Citation2015b). A major change in approach was the definition of drug use as an illness rather than an exclusively criminal act. For instance, the Turkish government introduced a heroin substitution programme for the first time in 2010 and permitted the prescription of Buprenorphine for outpatient heroin users.

On the other hand, harm reduction as a policy domain has not received much attention because HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C, diseases mostly associated with intravenous drug use through shared dirty needles, are not as widespread as in Europe or other parts of the world (Chatwin, Citation2015a; Kramer, Citation2015). According to national drug reports, a total of 7528 new HIV/AIDS cases were identified between 1985 and 2013 in Turkey, out of which only 174 cases occurred in injecting drug users. Although there has been a sharp increase in HIV/AIDS prevalence over the last decade (from 292 cases in 2005 to 1313 cases in 2013), only 4 of the cases identified in 2013 reported that they were injecting drug users (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2014), suggesting that intravenous drug use plays a very limited role in HIV/AIDS prevalence. However, hepatitis C appears to be somewhat disproportionately more prevalent among injecting drug users. While about one-third of inpatient drug users (29.91%) in 2009 were diagnosed with hepatitis C, about half (45.7%) were diagnosed in 2013 (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2014). Yet the overall threat to society from injecting drug users in terms of hepatitis C is estimated to be low, which may explain Turkish policy makers’ reluctance in the harm-reduction policy domain.

The Turkish government made reforms in the criminal justice system as it relates to illicit drugs. In 2004, an amendment was made to redefine the acts of drug use and drug possession and to propose two years’ imprisonment as the maximum sentencing period for drug possession. Moreover, a parole system was first introduced to the criminal justice system in 2005. Offenders charged only with drug possession can now apply for parole. This reform has led to a sizable decrease in the number of drug users incarcerated. According to a 2008 Parliament report, those charged with drug possession constituted less than 5% of the drug offenders in prisons (Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi, Citation2008).

While the parole opportunity provided to those charged with drug possession significantly reduced the drug-related prison population on the one hand, it has put much strain on the newly founded and immature parole system on the other. The number of parolees increased exponentially in the following years and reached 123,000. Drug offenders constituted more than half of the parolees in 2014 (Ceza ve Tevkifevleri Genel Müdürlüğü, Citation2015). The parolee system also increased the burdens on the treatment and rehabilitation system because participation in treatment services was compulsory to remain on parole. At the same time that the treatment and rehabilitation system was unable to respond to routine treatment demands, it became overwhelmed with parole referrals. According to the official records distributed by TUBIM, there were 141,454 parole referrals to treatment services between 2006 and 2013 (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2014).

According to Ministry of Health statistics, 26 government and privately owned hospitals with a 706-bed total inpatient capacity strived to respond to 226,471 treatment applications for drug problem in 2013. The Ministry of Health is expected to open 18 more treatment centres by the end of 2018 in accordance with the objectives set in the National Drug Policy and Strategy Document for the 2013–2018 period (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2014). To improve and standardise treatment quality, the Ministry of Health initiated a certification programme that encompasses six months of training in 2013; 35 experts graduated in the same year (Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi, Citation2014). As seen above, insufficient health infrastructure has led the government to intervene with the problem via the criminal justice framework.

Despite taking incremental steps towards a less punitive drug-control policy over the last decade, Turkish drug-control policy took a turn towards the draconian in 2014. This trend resulted particularly from the urge for a quick response to the increasing drug use and the rise in frequency of drug-related deaths portrayed by the media. Recently, public attention focussed on the prevalence of synthetic cannabinoids and related deaths, particularly among teenagers in public places. Under media and social pressure, the Turkish government enacted new reforms in 2014 that diverged from the previous paradigm. To mark the beginning of the new era, Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu remarked at the first annual meeting of the Anti-Drug Council, held in Ankara on 28 November 2014, that the government deemed drug dealers to be of the same ilk as the most dangerous terrorists and would treat dealers as such (Sabah Gazetesi, Citation2014).

The government classified synthetic cannabinoids among the drugs that require the maximum period of imprisonment (with a 50% increase in the penalty) for trafficking-related offences. The government also classified drug use as an offence with the new amendment and increased the minimum and maximum imprisonment periods for all drug offences. For example, while previous law proposed one to two years’ imprisonment for drug possession, the new one extended it to two to five years for possession and defined drug use as an offence. Similarly, offenders charged with illegal drug production, importation, or exportation can be sentenced with up to 30 years’ imprisonment, an increase of 10 years to the maximum sentence imposed before the amendment. In addition, a restriction was introduced to make second-time parole applicants within five years ineligible for parole.

Discussion

It is apparent from the foregoing discussion that Turkish drug-control policy leans towards supply-side policies and lacks sufficient focus on the demand side. We have stated that international treaties and pressure are the “push factors” that have led the Turkish government to focus on illicit drug trafficking. Turkey has proven its effectiveness in countering international drug trafficking over the past few decades. It appears, however, that maintaining its international prestige appears to be the primary factor motivating the Turkish government to continue its leading role in countering international drug trafficking. The Turkish government continues to prioritise supply reduction. For instance, the Counter-Narcotics Department, previously a part of the Department of Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime of the Turkish National Police, was extracted from the former department. As a result, illicit drugs are now dealt with at a higher bureaucratic level, with more units at the street level across Turkey and higher levels of dedicated budgetary and human resources. We expect that these institutional changes will not only satisfy the desire for international prestige by increasing seizures but also alleviate public dissatisfaction with drug law enforcement.

The demand-side policies prioritising the health perspective starting with the 2005 amendments have been pushed into the background with the legislative amendments of 2014. Improvements in infrastructure and human resources in the domain of demand reduction have failed to keep up with exponentially growing drug use. The Turkish government has been criticised for implementing strict regulations for the establishment of private treatment and rehabilitation centres, not allocating resources to expand such centres, and not empowering local authorities to develop policies and establish necessary infrastructure (Karataşoğlu, Citation2013). As a result, the government felt obliged to respond to the nation’s increasing drug use with a more punitive response engaging the criminal justice mechanism. Understanding the nature of Turkish drug-control policy requires that attention be given to the way in which ideological views shape the preferences of policy makers and the bureaucracy. Ideology tends to shape the conception of – and, in turn, the responses to – social issues. The current government, under the rule of the Justice and Development Party since 2001, comes from an Islamist and conservative background. Robins (Citation2008) claims that the ruling elite of the Turkish government has not prioritised social responses to the illicit drugs issue because, in their Islamic and conservative ideology, Islam and family-based social cohesion provides an effective barrier against substance use and social erosion without the need for further policy formulation (Robins, Citation2008). This conviction, however, contradicts the facts, as well as experiences in other Muslim countries such as Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan, where drug use is more prevalent than in many western societies (Felbab-Brown, Citation2015; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Citation2013). For that reason, Ankara has focussed its reforms on good governance to increase accessibility to and improve the quality of services rather than developing a comprehensive drug-control policy. Some progress has occurred in that regard. For instance, the processing period for drug treatment applications has shortened in the last 10 years (Yüncü et al., Citation2014). Nevertheless, when good governance strategy failed to a large extent, Ankara turned to the moralistic perspective in 2014, despite the fact that the majority of the Turkish society does not see drug addicts as criminals but ill people in need of treatment (Işik, Citation2013).

The relative deficiency in the demand-side aspect of the Turkish illegal drugs policy agenda is in part attributable to the hierarchical bureaucratic structure involved in policy making. The lead agency, TUBIM, ranks at a lower hierarchical level than other governmental stakeholders such as the ministries of education, health and family – fields in which demand-reduction policies are salient. Therefore, TUBIM, staffed entirely by members of the Turkish National Police, has neither significant experience in fields other than law enforcement nor any bureaucratic authority over other governmental bodies to impose policy changes and control compliance with the objectives set in the National Drug Strategy and Action Plan. Although there exist ad hoc advisory boards composed of representatives from other governmental and non-governmental institutions, these boards’ impact on governmental policy is limited. Members within the Turkish bureaucracy expressed dissatisfaction with the appointment of TUBIM, a law enforcement body, as the national liaison for drug policy to the EU (Robins, Citation2009). Nevertheless, TUBIM has been able to garner cooperation from other agencies and make meaningful contributions, such as the creation of the National Drug Strategy and Action Plan, as well as collecting illegal drugs-related data from the national agencies and sharing them with the EMCDDA. But in order for demand-side policies to be adopted at a satisfactory level, Turkey should seriously consider transferring the national mandate and responsibility for illicit drugs control policy to governmental agencies other than law enforcement. This new institution should address the shortcomings of the current one, such as its legislative framework and dedicated budget. Given the Turkish bureaucratic and hierarchical subculture, it is imperative that the new institution be founded under the Prime Ministry so that it has a mandate and executive power over relevant governmental ministries.

The human resources involved in policy making and implementation are of pivotal importance to these policies’ effectiveness. Over the last decade, the Turkish bureaucracy members operating in the field of illicit drugs – highly motivated by the career-advancement opportunities, expertise, and international activities the policy field provides (Cevik, Citation2013) – has been engaged in a learning phase, particularly with and from the EU through twinning projects. This learning encompasses not only contemporary strategies and actions against illicit drugs but also a collaborative approach among different government agencies. Experts, executives and academics from various levels of the Turkish bureaucracy have created a cooperative network. The incremental progress achieved over the last decade is the product of this fruitful cooperation, in which institutional rivalries have been set aside. Yet the Turkish bureaucracy has undergone a tremendous transformation over the last three years, and the dearth of experts in the field of drug policy is its biggest challenge (Karataşoğlu, Citation2013). In the aftermath of the December 17/25 Graft Probe that implicated a number of ministers from the Turkish government, the Turkish bureaucracy has been subjected to an unprecedented reshuffling by the government. We are not aware to what extent the bureaucracy involved in drug-control policy making and implementation have been affected by this shuffling. At the very least, it is safe to anticipate that it has created a distrustful environment at all levels of the bureaucracy, an atmosphere to which illicit drugs policy makers cannot be immune. Policy makers in the bureaucracy are now more risk averse and concerned with doing things correctly than with doing the right thing, for fear that they will make a career-ending mistake. As a result, the Turkish bureaucracy can be expected to incline towards policy preferences that resonate with the political will of the Turkish government, which tends to favour conservative and punitive policies.

In addition, two external challenges will have short-run implications for the illicit drugs situation in Turkey and its drug-control policy: the refugee influx from the Syrian War and the security situation in southeastern Turkey resulting from the heightened PKK insurgency. Syrian refugees may escalate the illicit-drugs problem. It is estimated that more than 3 million refugees have entered Turkey since the advent of the Syrian civil war. The majority of these refugees are totally uncontrolled within the Turkish cities (Yayla, Citation2015). We have no available information on the effect of Syrian refugee influx on crime levels in Turkey. The illicit drugs business may be attractive to Syrian refugees, stripped as they are of all their savings and desperate to make a living. Syrian refugees are attractive targets for drug trafficking networks to employ as cross-border mules or street-level dealers; for example, the Sanliurfa Police Department seized 16 kg of Syrian cannabis in a Syrian-registered vehicle driven by a Syrian male on 9 April 2016. Academic interest regarding Syrian refugees’ involvement in crime and drug trafficking is lacking, not least because research on Syrian refugees requires special permission from the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Media coverage has, however, drawn attention to the increasing role of Syrian refugees in drug trafficking (İzmir Emniyet Müdürlüğü, Citation2016; Karar Gazetesi, Citation2016; Posta Gazetesi, Citation2016; Yeni Asya Gazetesi, Citation2015).

In addition to the Syrian War and its consequences as felt in Turkey, the intensified conflict with the PKK in Turkey’s southeastern region since October 2014 is expected to worsen the drug situation within and beyond the borders. The unprecedented level of threat posed by the PKK to the security of the region forces law enforcement to remain safely headquartered in cities, focussing on the PKK insurgency rather than drug trafficking at streets and in border cities. The circumstances resulting from the PKK insurgency have facilitated drug trafficking, particularly of heroin, in the Iranian border, as well as cannabis cultivation in the rural areas of the region (Akgül & Yilmaz, Citation2015). Moreover, while counterterrorism is prioritised, the struggle against street-level trafficking and drug use is underemphasised in the region. The security challenges besetting southeast Turkey also deepen drug-use prevalence in the western cities because the increasing availability of heroin and cannabis will reduce the drugs’ prices, thereby increasing consumption.

Conclusion

What should the Turkish government do to better address illicit drugs? For one thing, the focus on supply reduction and law enforcement activities should continue, though not to the neglect of demand-side policies, and these activities should be accompanied by effective measures to seize illicit profits. Turkey needs a holistic approach that sufficiently addresses each of these policy domains. Strengthening of the demand-reduction policies will necessitate the allocation of greater resources and responsibility to governmental agencies that have a vested mandate for education, health, and family. This process should follow a thorough national drugs strategy accompanied by an action plan outlining specific objectives to be achieved, with a time scale subject to formal assessment. It would be important to transfer the national focal point of responsibility to governmental agencies other than law enforcement, specifically to a newly founded body under the Ministry of Prime Ministry. As well, more resources and capacity-building efforts are particularly needed in the field of treatment of drug users. Serious consideration should be given to how to deal with the exponentially growing number of treatment demands. The current government approach diverts drug policy away from modern intervention strategies such as expanding substitution treatments, decriminalisation and other sorts of harm-reduction programmes.

The recent 2014 amendment signals a shift towards punitive policies in the drug-control realm. Draconian policies tend to be counter-effective, however. Recent policy changes within the criminal justice and health fields do not appear to have made a significant impact on drug prevalence and drug related deaths thus far. In addition, new challenges, such as the Syrian refugee influx and the ongoing intensified armed conflict with the PKK in the southeastern region, will only aggravate the depth and breadth of the drug problem, necessitating special attention by the government. Unless a paradigm shift occurs in Turkish drug-control policy and due attention is given to demand-side policies, we can expect that illicit drug use, and in turn the pressure on the criminal justice system and treatment services, will continue to escalate despite increasing bulk seizures.

Declaration of interest

There are no conflicts of interests to report.

Notes

1The data were aggregated from National Drug Reports prepared by the Turkish Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (TUBİM).

2A direct drug-related death occurs when the primary reason for death is identified in autopsy as illicit drugs, such as in cases of overdose, whereas death that occurs under the influence of illicit drugs is categorised as an indirect drug-related death.

3Terrorist organisations may prefer to engage and stop drug dealers on their turf as a means to build popular public support, although they might have had ties in the past. DHKP-C (The Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party) members in Istanbul and IRA (Irish Republican Army) in Northern Ireland are known have employed such tactics.

References

- Afsahi, K. (2015). Are Moroccan cannabis growers able to adapt to recent European market trend? International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, 327–329. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.11.012

- Akgul, A., & Gurer, C. (2014). The European Union and emergence of a drug policy institution in Turkey. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 21, 460–469. doi:10.3109/09687637.2014.911816

- Akgül, A., & Yilmaz, K. (2015). Ramifications of recent developments in Turkey’s southeast on cannabis cultivation. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, 330–331. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.08.005

- Arslan, M.M., Zeren, C., Celikel, A., Ortanca, I., & Demirkiran, S. (2015). Increased drug seizures in Hatay, Turkey related to civil war in Syria. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, 116–118. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.04.013

- Block, L. (2010). Bilateral police liaison officers: Practices and European policy. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 6, 194–210

- Cevik, K. (2013). Internalization of Turkish Law Enforcement A Study of Anti-Drug Trafficking. PhD thesis. University of Nottingham, Nottingham

- Ceza ve Tevkifevleri Genel Müdürlüğü. (2015). 2014 Yili Mart Ayi İstatistikleri. Retrieved October 3, 2015, from http://www.cte.adalet.gov.tr

- Chatwin, C. (2015a). Mixed messages from Europe on drug policy reform: The cases of Sweden and the Netherlands. Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence, Latin America Initiative, Improving Global Drug Policy: Comparative Perspectives and UNGASS 2016, 1–12. doi:10.1515/jdpa-2015-0009

- Chatwin, C. (2015b). Mixed messages from Europe on drug policy reform: The cases of Sweden and the Netherlands. Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence, Latin America Initiative, 1–12

- Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American sociological review 44, 588–608

- Decorte, T., & Potter, G.R. (2015). The globalisation of cannabis cultivation: A growing challenge. International Journal of Drug Policy , 26, 221–225. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.12.011

- Dursun, H. (2005). Ekonomik suçlar ve Türkiye’deki sürdürülebilir kalkinmaya etkileri. Türkiye Barolar Birliği Dergisi, 58, 215–245

- Ekici, B. (2014). International Drug Trafficking and National Security of Turkey. Journal of Politics and Law, 7, 113–126. doi:10.5539/jpl.v7n2p113

- Ekici, B., & Coban, A. (2014). Afghan heroin and Turkey: Ramifications of an international security threat. Turkish Studies, 15, 341–364. doi:10.1080/14683849.2014.926668

- Ekici, B., Phil, W., & Ayhan, A. (2012). The PKK and the KDNs: Cooperation, convergence or conflict? In Strozier, C.B., & Strozier, C.B. (Eds.), The PKK: Financial sources, social and political dimensions (Vol. VDM Verlag Dr. Müller, pp. 146–165). Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller

- Ekici, B., & Unlu, A. (2013). Increased drug trafficking from Iran: Ankara’s challenges. The Middle East Quarterly, 20, 41–48

- Erdinç, F.C. (2004). Overdose Türkiye: Türkiye’de eroin kaçakçiliği, bağimliliği ve politikalar. Cagaloglu, Istanbul: Iletisim

- Eriksen, S. (2007). Institution building in central and eastern Europe: Foreign influences and domestic responses. Review of Central and East European Law, 32, 333–369. doi:10.1163/092598807X195232

- Evered, K.T., & Evered, E. (2016). “Not just eliminating the mosquito but draining the swamp”: A critical geopolitics of TUBİM and Turkey’s approach to illicit drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy. Advance online publication. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.05.003

- Felbab-Brown, V. (2015). No easy exit: Drugs and counternarcotics policies in Afghanistan. Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence, Latin America Initiative, Improving Global Drug Policy: Comparative Perspectives and UNGASS 2016, 1–20

- Gingeras, R. (2010a). Beyond Istanbul’s ‘Laz Underworld’: Ottoman paramilitarism and the rise of Turkish Organised Crime, 1908–1950. Contemporary European History, 19, 215–230. doi:10.1017/S0960777310000135

- Gingeras, R. (2010b). Last rites for a ‘Pure Bandit’: Clandestine service, historiography and the origins of the Turkish ‘deep state’. Past & Present, 206, 151–174. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtp047

- Gingeras, R. (2011). In the hunt for the “sultans of smack”: Dope, gangsters and the construction of the Turkish deep state. The Middle East Journal, 65, 426–441. doi:10.3751/65.3.14

- Işik, M. (2013). Madde Kullanimi ve Stratejik İletişim. Ankara: Sage

- İzmir Emniyet Müdürlüğü. (2016). Uyuştuucu Madde Ticareti Yapan Suriyeli Yakalandi [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.izmir.pol.tr/Haberler/Sayfalar/Uyuşturucu-Madde-Ticareti-Yapan-Suriyeli-Yakalandi.aspx

- Kaçakçilik ve Organize Suçlarla Mücadele Daire Baskanligi. (2000). Kaçakçilik ve Organize Suçlarla Mücadele: 1999 raporu. Retrieved from http://www.kom.pol.tr/Documents/Raporlar/1999.pdf

- Kaçakçilik ve Organize Suçlarla Mücadele Daire Baskanligi. (2006). Kaçakçilik ve Organize Suçlarla Mücadele: 2005 raporu. Retrieved from http://www.kom.pol.tr/Documents/Raporlar/2005.pdf

- Kaçakçilik ve Organize Suçlarla Mücadele Daire Baskanligi. (2010). Kaçakçilik ve Organize Suçlarla Mücadele: 2010raporu. Retrieved from http://www.kom.pol.tr/SiteAssets/Sayfalar/Raporlar/2010.pdf

- Kaçakçilik ve Organize Suçlarla Mücadele Daire Baskanligi. (2015). Kaçakçilik ve Organize Suçlarla Mücadele: 2014 raporu. Retrieved from http://www.kom.pol.tr/Documents/Raporlar/2015tur.pdf

- Karar Gazetesi. (2016). Gaziantep’te Suriyeli göçmen uyuşturucudan tutuklandi. Retrieved March 11, 2016, from http://www.karar.com/gundem-haberleri/teror-orgutu-propagandasindan-54-universiteliye-gozalti-116949

- Karataşoğlu, S. (2013). Sosyal politikalar boyutuyla madde bağimliliği. TüRk İdare Dergisi, 476, 321–352. doi:10.17681/hsp.34389

- Kramer, T. (2015). The current state of counternarcotics policy and drug reform debates in Myanmar. Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence Latin America Initiative - Brookings, 1–14

- Laciner, S. (2008). Drug smuggling as main source of PKK terrorism. The Journal of Turkish Weekly Retrieved from http://www.usak.org.tr/en/usak-analysis/security-and-terrorism/drug-smuggling-as-main-source-of-pkk-terrorism

- Posta Gazetesi. (2016). Suriyeli çocuğun kafasini 250 lira için kesmiş! Retrieved May 11, 2016, from http://www.posta.com.tr/3Sayfa/HaberDetay/Suriyeli-cocugun-kafasini-250-lira-icin-kesmis-htm?ArticleID=334376

- Potter, G., Bouchard, M.M., & Decorte, M.T. (2013). World wide weed: Global trends in cannabis cultivation and its control. Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd

- Pumariega, A.J., Burakgazi, H., Unlu, A., Prajapati, P., & Dalkiliç, A. (2014). Substance abuse: Risk factors for Turkish youth. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni-Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24, 5–14. doi:10.5455/bcp.20140317061538

- Robins, P. (2008). Back from the brink: Turkey’s ambivalent approaches to the hard drugs issue. Middle East Journal, 62, 630–650. doi:10.3751/62.4.14

- Robins, P. (2009). Public policy making in Turkey: Faltering attempts to generate a national drugs policy. Policy & Politics, 37, 289–306. doi:10.1332/030557309X397937

- Roth, M.P., & Sever, M. (2007). The Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) as criminal syndicate: Funding terrorism through organized crime, a case study. Studies in Conflict Terrorism, 30, 901–920. doi:10.1080/10576100701558620

- Sabah Gazetesi. (2014). Davutoğlu: Uyuşturucu tacirleri terörist gibi… [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.sabah.com.tr/gundem/2014/11/28/basbakan-davutoglu-ankarada-konusuyor-canli

- Singleton, N., & Rubin, J. (2014). What is good governance in the context of drug policy? International Journal of Drug Policy , 25, 935–941. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.03.008

- Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi. (2008). Uyuşturucu Başta Olmak Üzere Madde Bağimliliği ve Kaçakçiliği Sorunlarinin Araştirilarak Alinmasi Gereken Önlemlerin Belirlenmesi Amaciyla Kurulan Meclis Araştirma Komisyon Raporu. Ankara: Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi

- Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi. (2011). EMCDDA 2011 ulusal raporu (2010 verileri) Reitox ulusal temas noktasi: Türkiye, yeni gelismeler, trendler, seçilmis konular. Retrieved from http://www.kom.pol.tr/tubim/SiteAssets/Sayfalar/T%C3%BCrkiye-Uyu%C5%9Fturucu-Raporu/2010(T%C3%9CRK%C3%87E).pdf

- Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi. (2012). EMCDDA 2012 ulusal raporu (2011 verileri) Reitox ulusal temas noktasi: Türkiye, yeni gelismeler, trendler, seçilmis konular. Retrieved from http://www.kom.pol.tr/tubim/SiteAssets/Sayfalar/T%C3%BCrkiye-Uyu%C5%9Fturucu-Raporu/2012(T%C3%9CRK%C3%87E).pdf

- Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi. (2013). EMCDDA 2013 ulusal raporu (2012 verileri) Reitox ulusal temas noktasi: Türkiye, yeni gelismeler, trendler, seçilmis konular. Retrieved from http://www.kom.pol.tr/tubim/SiteAssets/Sayfalar/T%C3%BCrkiye-Uyu%C5%9Fturucu-Raporu/2013(T%C3%9CRK%C3%87E).pdf

- Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağimliliği İzleme Merkezi. (2014). EMCDDA 2014 ulusal raporu (2013 verileri) Reitox ulusal temas noktasi: Türkiye, yeni gelismeler, trendler, seçilmis konular. Retrieved Retrieved from http://www.kom.pol.tr/tubim/SiteAssets/Sayfalar/T%C3%BCrkiye-Uyu%C5%9Fturucu-Raporu/TUBIM%202014%20TURKIYE%20UYUSTURUCU%20RAPORU_TR.pdf

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2013). World drug report 2013. Vienna: United Nations

- Unlu, A., & Ekici, B. (2012). The extent to which demographic characteristics determine international drug couriers’ profiles: A cross-sectional study in Istanbul. Trends in Organized Crime, 15, 296–312. doi:10.1007/s12117-012-9152-6

- Ünlü, A., & Evcin, U. (2014). İstanbul’da liseli gençler arasindaki madde kullanim yayginliği ve demokrafik faktörlerin etkileri (Substance use among high school students in Istanbul and effect of demographic factors). Litaratür Sempozyum (Literature Symposium), 1, 2–11

- Ünlü, A., Evcin, U., Dalkilic, A., & Pumariega, A.J. (2013). Substance use prevalence according to public high school types in Istanbul. Addictive Disorders Their Treatment, 13, 75–86. doi:10.1097/ADT.0b013e31829111b6

- Windle, J. (2011). Poppies for medicine in Afghanistan: Lessons from India and Turkey. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 46, 663–677. doi:10.1177/0021909611417393

- Windle, J. (2013a). Preventing the diversion of Turkish opium. Security Journal, 29, 213–227. doi:10.1057/sj.2013.8

- Windle, J. (2013b). A very gradual suppression: A history of Turkish opium controls, 1933–1974. European Journal of Criminology, 11, 195–212. doi:10.1177/1477370813494818

- Yayla, A.S. (2015). Deadly interactions. World Policy Institute, World Policy Journal: Winter 2015/2016

- Yeni Asya Gazetesi, (2015). Trajediye döndü. Retrieved May 11, 2016, from http://www.yeniasya.com.tr/gundem/trajediye-dondu_350792

- Yildiz, S., & Ünlü, A. (2011). Kurumsal Teori Bağlaminda AB Üyelik Sürecinde Türk Polisinde Değişim. Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart Üniversitesi, 9, 217–237

- Yüncü, Z., Saatcioğlu, H., Aydin, C., Özbaşaran, N.B., Altintoprak, E., & Köse, S. (2014). Bir Şehir Efsanesi: Madde Kullanmaya Başlama Yaşi Düşüyor mu? Literatür Sempozyum, 1, 43–50