Abstract

Aims: On the 26th of May 2016, the UK Government introduced the Psychoactive Substances Act, 2016. The aim of this short report is to explore online shops selling New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) stated motivations for closing and the changes that arose preceding the ban. Methods: The search for online shops selling NPS was made throughout October 2015. From March to June 2016, data were collected on the status of the online shops, and whether they mentioned the ban, the delay, or their closure. Results: From the original 113 online shops, only 52% remained open. Those that remained were either based overseas (65%), removed NPS and became a headshop (19%), or were inactive (16%). Only 24% of UK-registered websites remained open after the ban. Conclusions: UK-registered websites closed down or moved domain locations and no longer sold to UK customers. UK-registered websites communicated with customers at each stage of the legislation. It is unknown whether the UK retailers have ceased selling NPS or have been displaced to underground markets (street level dealing or the hidden web). The majority of shops in this study were located in Europe or North America, showing that there is still high demand in both continents.

Introduction

Online suppliers of New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) on the surface web (the web that can be accessed by general search engines such as Google™ or Bing™) have revolutionised the drugs marketplace and it reflects the modern, demand-based approach of e-commerce (Seddon, Citation2014). Customers can purchase drugs from online shops from anywhere in the world from their home, work or mobile phone. The benefit to purchasing online compared to traditional street level dealing, is that the consumer can access harm reduction advice and reviews on products and both the consumer and the supplier feel more secure due to lack of physical contact, (EMCDDA & Europol, Citation2016; Seddon, Citation2014). Online supply is a growing platform, mirroring the global increasing use of the Internet (EMCDDA & Europol, Citation2016).

Evidence is mixed to what the predominant method of obtaining NPS is. Some suggest the majority of NPS are bought online (Fattore & Fratta, Citation2011), whereas others find that it was predominantly through friends or street level drug dealers (European Commission, Citation2014). In 2013, there were 651 online shops selling NPS, listing in pounds or euros and shipping to Europe (EMCDDA, Citation2014). The UK is a popular market for NPS with an estimate of around a fifth of the online shops in 2011 based there, the second largest source after the USA (Schmidt, Sharma, Schifano, & Feinmann, Citation2011). The products available on the surface web vary with availability and with legislation (Smith & Garlich, Citation2013). Suppliers remove substances that are controlled or continue selling the controlled substances but under different descriptions (Home Office, Citation2014a). However, the UK’s Home Office found that when chemical names of active ingredients are stated on NPS packets sold online, they do reflect the contents of products (Home Office, Citation2014b).

It is suggested that non-controlled NPS are sold on the surface web and in offline retail vendors, such as “headshops” that specialise in drug paraphernalia, and controlled substances are sold on the hidden web (an online network that cannot be accessed via regular search engines), or non-retail vendors such as street dealers (Home Office, Citation2014a). Schmidt et al. (Citation2011) found that there is an increasing number of grey marketplace developments, where some surface web websites have sales taking place on the hidden web, once sellers have “built trust” with sellers, or to sell controlled NPS.

Following similar footsteps of Ireland and Poland (Hughes & Winstock, Citation2012), the UK Government introduced the Psychoactive Substances Act, 2016 on the 26th May of 2016 (UK Government, Citation2016). The Act was originally set to come into force in April 2016 but was delayed due to concerns that the broad definition of a psychoactive substance would complicate enforcement. The Act controls all psychoactive substances (with some exemptions), that are not already controlled by the Misuse of Drugs Act (UK Government, Citation2016). In the Psychoactive Substances Act, possession is not an offence, but supply and production is criminalised, and its intention therefore was to close all online and offline retail sales.

The Psychoactive Substances Act has received criticism and it has been argued that prohibition will simply displace the market from visible Internet sales and offline shops to criminal networks (Reuter & Pardo, Citation2016; Stevens, Fortson, Measham, & Sumnall, Citation2015). After the implementation of Psychoactive Substances Act 2010 in Ireland, 90% offline shops closed down (Kavanagh & Power, Citation2014). A report by Smyth, James, Cullen, and Darker (Citation2015) showed that after the ban in Ireland, the use of NPS was reduced but not eliminated and a report from the Health Research Board (Citation2015) found that deaths from NPS increased.

Since the Psychoactive Substances Act in the UK is set to criminalise online shops, and thus remove a primary supply route of legal NPS, this paper explores: i. the hypothesis that all online shops with a UK domain location will abide by the new law; ii. the changes that arose to online shops preceding the implementation of the ban; iii. the implications of the findings on the NPS market after the introduction of the ban.

Methods

The search for online shops selling NPS were made throughout October 2015. Search engine’s Google™ and Bing™ were used and various keywords were chosen to extract websites such as “buy” followed by “legal highs” or “research chemicals” or “bath salts” or “party pills” or “herbal highs”.

For every keyword, the first five pages of results were used, and those in the English language and distributed to the UK were extracted. Data collected from the websites included: last update of website; the country of domain; and countries of distribution.

From the end of March until the beginning of June (2016), data were collected on whether the online shops remained open and whether they mentioned the ban, the delay of the ban, or their closure. In the three days preceding the ban, data were collected daily.

Data were collected using an Excel spreadsheet and a descriptive analysis was conducted using SPSS version 21.

The research was observational and did not involve interaction with either customers or shop owners. The study was approved by King’s College London PNM Research Ethics reference number: LRS-15/16-3084, as part of the wider CASSANDRA project.

Results

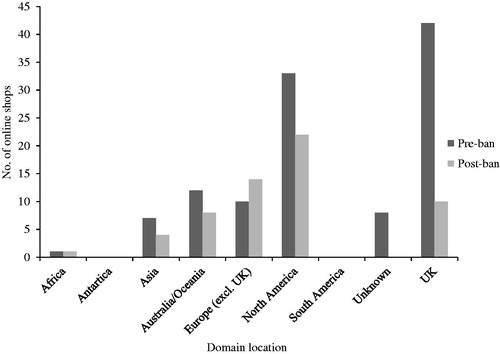

In October 2015, a total of 113 shops selling NPS on the Internet were found in the English language and shipped to the UK. Substances were sold in different forms, some were powders, herbal incense or pellets, and some were in branded packages. The domain locations of the websites were recorded before and after the ban on the 26th of May (). Before the ban, the domain locations of websites were predominantly based in Europe (46%) and four fifths of those were in the UK. After the ban, domain locations remained predominantly in Europe (41%) closely followed by North America (37%); however, the UK suffered the greatest reduction of shops, losing a total of 31.

From the original 113 online shops that were collected in October, 11 shops had already closed by April, and only 52% remained open in May. Of those that remained open, the majority (64%) were based overseas and shipped worldwide, not just to the UK. Focussing on the UK, 14 shops had a UK domain location prior to the ban, however, four shops switched to a European server; three in Germany and one in Norway. Ten UK-registered websites remained open (24% of the original UK shops); nine removed the sale of NPS and were headshops or cannabis seed stores and one was presumed inactive. On the 26th of May, there were no remaining active shops with a UK domain that were selling NPS.

In the days preceding the date of implementation, the number of open shops decreased from 98 to 65 (), and fell to 59 shops in the days after the implementation. Three days before the ban, 31% of shops communicated updates of the legislation (), this dropped in the days up to the 26th of May. On the day of the ban, 9% of shops that were still open had updated or mentioned the day of the ban to their customers. Few non-UK registered websites communicated with their customers about the pending ban. However, some shops thanked their UK customers, and stated that they would no longer be delivering to the UK.

Table 1. The number of online shops open, and updates provided by the shops in the days surrounding the implementation of the Psychoactive Substances Act, 2016.

The shops that updated their websites to notify their customers of changes did so regularly. For example, Official BenzoFury (officialbenzofury.net) frequently posted updates to their website:

OBF [Official BenzoFury] are looking to purchase a tropical island which will allow us to create our own laws (1st April 2016).

UK Ban Has Been Delayed Further Details Will Be Announced When Accuracy Of Reports Can Be Confirmed (6th April 2016).

Possession is not an offence – stock up now (13th of May 2016).

We are now closed to our UK customers! (25th May 2016).

Discussion

From the original 113 online shops, all those with a domain location in the UK that sold NPS closed down by the 26th May of 2016, before their business became illegal. Ten (24%) of the original UK-registered websites remained open but removed sales of NPS to become a headshop and four (17%) had moved domain locations and no longer sold NPS to UK customers. This mirrors what was found by the UK Government, that shops abide by the law and remove substances once controlled (Home Office, Citation2014a). Of the 59 shops that remained open, they were either based overseas, removed sales of NPS, or were no longer active. The inactivity of the sites complements what was found by the UK Home Office (Citation2014b), where quality of sites differ greatly and some update regularly and provide customer service, whereas others do not update and merely display products. It should be noted that 11 shops had already closed before data collection in April had begun, suggesting early preparation or a natural decay of a websites lifespan. Most of the shops that closed in the preceding days before the ban had forewarned their customers, either by updating their website with information on the ban, promoting sales on stock or promoting low stock that “must go”. This suggests that the stores may have closed rather than continued in underground markets. However, it is suggested that sales of NPS would be displaced to street level dealing or to the hidden web (Schmidt et al., Citation2011; Stevens et al., Citation2015). The use of the hidden web for the sale of drugs has increased in recent years (EMCDDA & Europol, Citation2016), and thus an established platform is arguably available to take the sales of the once legal UK NPS.

Limitations

Selection of online shops was only performed a single time in October 2015; therefore the data does not include online shops in the English language that opened after October. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) performed a snapshot of NPS shops online in Europe and found a higher number than in this study (EMCDDA, Citation2014). However, our study’s inclusion criteria focussed on the UK and only collected data from the first five pages of search engines. This did not capture online stores after the fifth page or not in the English language. A total of 113 online shops were found to be sufficient for studying the movement of retailers during the changes of UK legislation. This study did not make any purchases from the online shops, and so shop activity was not confirmed. However, it was decided between the authors that an up to date website and/or social media page was sufficient evidence of activity.

Conclusions

For the online shops in this study, the stated motivation for UK-registered websites to close or remove the sale of NPS was the implementation of the Psychoactive Substances Act. UK-registered websites abided by UK law, and closed down or moved domain locations. The UK-registered websites communicated with their customers about the initial ban, the delay to the ban, and the implementation of the ban. Some overseas shops notified customers that they would no longer be distributing to the UK, however, the majority did not mention the change of UK legislation. The majority of shops in this study after the 26th of May were located elsewhere in Europe or North America, showing that there is still high demand for NPS in both of these continents (Smith & Garlich, Citation2013). From this brief study, it can be argued that the Psychoactive Substances Act has achieved one of its aims in the closure of online shops. However, further research is required to understand where UK customers will obtain their NPS, or whether they will return to traditional illicit drugs, or perhaps cease taking NPS.

Declaration of interest

This publication arises from the project CASSANDRA, (Computer Assisted Solutions for Studying the Availability aNd Distribution of novel psychoActive substances) which has received funding from the European Union under the ISEC programme Prevention of and fight against crime [JUST2013/ISEC/DRUGS/AG/6414].

Colin Drummond was partfunded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, and the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR, or Department of Health.

References

- EMCDDA. (2014). European drug report: Trends and developments. Lisbon: Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

- EMCDDA, & Europol. (2016). EU drug markets report: In-depth analysis. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

- European Commission. (2014). Flash Eurobarometer 401: Young people and drugs. Retrieved Jul 1, 2016, from http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/flash_arch_404_391_en.htm

- Fattore, L., & Fratta, W. (2011). Beyond THC: The new generation of cannabinoid designer drugs. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 5, 60. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00060

- Health Research Board. (2015). 2013 figures from the National Drug-Related Deaths Index. Retrieved from http://www.hrb.ie/uploads/tx_hrbpublications/NDRDI_web_update_2004-2013.pdf

- Home Office. (2014a). New psychoactive substances in England: A review of the evidence. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/new-psychoactive-substances-in-england-a-review-of-the-evidence

- Home Office. (2014b). New psychoactive substances review: Report of the expert panel. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/new-psychoactive-substances-review-report-of-the-expert-panel

- Hughes, B., & Winstock, A.R. (2012). Controlling new drugs under marketing regulations. Addiction, 107, 1894–1899. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03620.x

- Kavanagh, P.V., & Power, J.D. (2014). New psychoactive substances legislation in Ireland - perspectives from academia. Drug Testing and Analysis, 6, 884–891. doi:10.1002/dta.1598

- Reuter, P., & Pardo, B. (2016). Can new psychoactive substances be regulated effectively? An assessment of the British Psychoactive Substances Bill. Addiction, 112, 25–31. doi:10.1111/add.13439

- Schmidt, M.M., Sharma, A., Schifano, F., & Feinmann, C. (2011). “Legal highs” on the net—Evaluation of UK-based Websites, products and product information. Forensic Science International, 206, 92–97. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.06.030

- Seddon, T. (2014). Drug policy and global regulatory capitalism: The case of new psychoactive substances (NPS). International Journal of Drug Policy, 25, 1019–1024. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.03.009

- Smith, S.W., & Garlich, F.M. (2013). Availability and supply of novel psychoactive substances. In P. Dargan, & D. Wood (Eds.), Novel psychoactive substances: Classification, pharmacology and toxicology (pp. 55–77). London: Academic Press

- Smyth, B.P., James, P., Cullen, W., & Darker, C. (2015). “So prohibition can work?” Changes in use of novel psychoactive substances among adolescents attending a drug and alcohol treatment service following a legislative ban. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, 887–889. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.05.021

- Stevens, A., Fortson, R., Measham, F., & Sumnall, H. (2015). Legally flawed, scientifically problematic, potentially harmful: The UK Psychoactive Substance Bill. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, 1167–1170. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.10.005

- UK Government. (2016). Psychoactive Substances Act. Retrieved from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2016/2/contents/enacted