Abstract

Aims: On 30 January 2014, in efforts to reduce alcohol-related violence, the New South Wales Parliament adopted alcohol lockout legislation targeting a geographically defined area: the Sydney entertainment precinct. This study used qualitative methods to explore with stakeholders of two areas (Kings Cross/Potts Point and Newtown) whether there was any evidence of displacement of alcohol-related problems from inside to outside the lockout zone.

Methods: Four focus groups were conducted in mid-2015 with residents and patrons: two in Kings Cross/Potts Point (where the measures were implemented) and two in Newtown (an alternative entertainment precinct exempt from the measures). Each explored experiences pre and post lockouts and any perceived changes in the number of people in the area, level of disorderly conduct, patterns of drug and alcohol consumption, public amenity and public safety.

Findings: Stakeholders in Kings Cross/Potts Point reported many improvements since the reforms: including reduced patron numbers, less waste and improved public amenity. However, stakeholders from Newtown reported the opposite: increased patron numbers, reduced public amenity and reduced public safety.

Conclusions: This provides tentative evidence that even if the Sydney lockouts have reduced alcohol-related violence there may have been a partial displacement of alcohol-related problems to outside the lockout zone.

Introduction

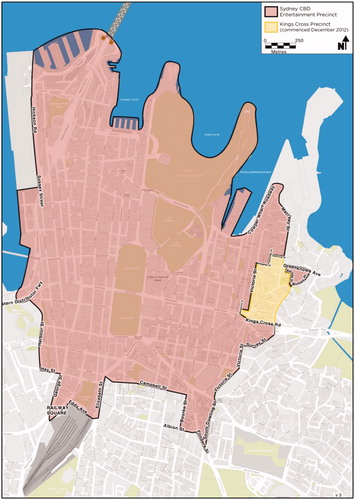

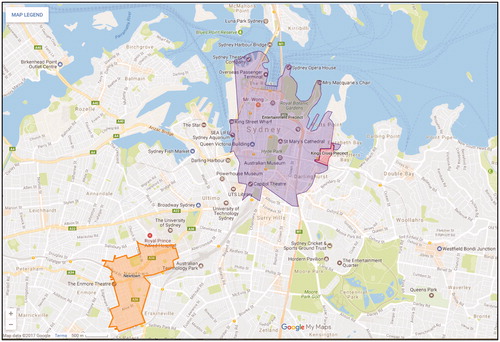

On 30 January 2014, in efforts to reduce alcohol-related violence, the New South Wales Parliament adopted alcohol lockout legislation targeting a geographically defined area: the “Sydney entertainment precinct” (Liquor Amendment Act 2014, NSW). The lockout law, which prevented patrons from entering or re-entering licensed premises after 1.30am, was introduced alongside a 3am restriction on alcohol trading within licensed venues, with both reforms operating exclusively within entertainment precincts in King’s Cross/Pott’s Point and the central business district (see ). Given, many other entertainment precincts across Sydney were exempt from the new reforms almost immediately concerns were levied about the potential for displacement of problems from inside to outside the lockout area. Displacement is defined as where the introduction of a situational crime prevention initiative can lead to the relocation of crime or crime-related issues from one place, time, target, offence or tactic to another, rather than addressing the root causes of crime (Guerette, Citation2009). In this case the Lord Mayor of Sydney, Clover Moore, argued: “what we don't want to see is tens of thousands of people making their way to other areas just outside of the new precinct” (Hasham, Citation2014). Moreover, the then NSW Premier Barry O’Farrell noted that the new laws would be closely monitored for any evidence of displacement (NSW Government, Citation2014) and the precinct boundaries amended if necessary: “if there is displacement”, “the boundaries of the precinct can be expanded” (NSW Government, 2014, p. 26646). That said, to date attention has focussed almost exclusively on potential displacement of alcohol-related violence (Menéndez, Tusell, & Weatherburn, Citation2015; Menéndez, Weatherburn, Kypri, & Fitzgerald, Citation2015), with potential impacts on public amenity, disorderly conduct and public safety ignored. Following increasing concerns that former patrons of the Kings Cross nightlife may have started spending time in Newtown (see ), a suburb of Sydney’s inner west celebrated for its highly inclusive community (Wallace & Koziol, Citation2015, 21 June) and are causing “conflict” with the local GLBTI community (Reclaim the Streets, Citation2016, p. 2), this study uses focus groups with residents and patrons from Kings Cross/Potts Point and Newtown (inside and outside the lockout zone respectively) to explore these issues.

Figure 1. Sydney entertainment precinct (the Lockout Zone). Source: Liquor Amendment Act 2014, Schedule 1A (NSW).

Alcohol regulations and displacement

Lockout laws, defined as an alcohol regulation measure that prevents patrons from entering or re-entering licensed premises after a designated time (Palk, Davey, & Freeman, Citation2010) have been used in a number of countries particularly Australia (with trials in most states and territories), but also New Zealand and Scotland (Bleetman, Perry, Crawford, & Swann, Citation1997; Miller, Chikritzhs, & Toumbourou, Citation2015). Evidence on the use of lockout laws is varied (for overviews see Howard, Gordon, & Jones, Citation2014; Miller et al., Citation2015; Wilkinson, Livingston, & Room, Citation2016). Some studies have found that lockouts in combination with early trading hours can lead to a substantial and sustained reduction in assaults (Kypri, Jones, McElduff, & Barker, Citation2011; Kypri, McElduff, & Miller, Citation2014). But, in general as summed up by Miller et al (Citation2016, p. 10) despite the popularity of such measures “evidence shows a lack of impact and some potential negative consequences”, including increased property damage of licensed premises and increased need for crowd control and police presence around lockout times. To date, there has been minimal evidence of displacement: but none of the reforms targeted a discrete geographic zone such as the Sydney lockouts. That said, other alcohol regulations that have targeted defined geographic areas – such as bans on public drinking have been found to lead to displacement (Howard et al., Citation2014). For example, in their review of public drinking bans in the UK, New Zealand and Australian studies, Pennay and Room (Citation2012) found that displacement was observed in 7 of the 13 locations into which public drinking bans were introduced: leading to a loss of public amenity and reduced public safety in the displaced zones without any apparent reduction in alcohol-related crime or harm. The introduction of voluntary-localised alcohol availability, restrictions have also been found to lead to displacement. For example, McGill et al (Citation2016) found that the removal of cheap, high-strength beer from some off-licenses (or bottle shops) in the UK encouraged a range of substitution behaviours to circumvent the restrictions including consumers switching sites of purchase (to purchase alcohol from off-licenses that still sold high-strength beer), consuming different drinks, using drugs or committing crimes to purchase more expensive drinks.

Figure 2. Location of Newtown (the displacement zone) and the lockout zone (the Sydney entertainment precinct). Source: Google Maps (Citation2017).

The Sydney lockout and impacts to date

In the case of the Sydney lockouts laws, their introduction garnered immediate and sustained attention and controversy. Indeed as noted by Lee (Citation2016, p. 117) it has “polarised Sydney residents and attracted protest from diverse sectors of the community.” For example, there have been multiple rallies through Sydney streets, petitions, as well as anti-lockout murals and constant media attention (McMah, Citation2016, 21 February; Reclaim the Streets, 2016; The Guardian, Citation2016, 9 October) and a recent independent review of the lockouts attracted more than 1800 submissions (Callinan, Citation2016). As noted by Independent Reviewer Ian Callinan (Citation2016, p. 3) “people on both sides of the issue hold, and have expressed very strong, sometimes strident and dogmatic, views.” On the one hand, music industry stakeholders, live music and performance venues, patrons, licensed premises and a newly formed anti-lockout advocacy group “Keep Sydney Open” (Citation2016) have argued the lockouts threaten Sydney’s nightlife, curtail civil liberties and ruin businesses of musicians and small bars. On the other hand, police, emergency room workers and the Government have argued that the lockouts have reduced alcohol-related violence in the community. Indeed, even before the results of the independent lockout review were tabled, the then NSW Premier Mike Baird showed his 100% support for the lockouts: “as I've said before, it is going to take a lot for me to change my mind on a policy that is so clearly improving this city” (cited in McNally, Citation2016, 9 February). That said, a key concern of all parties has remained the capacity for displacement of problems to other areas of the city.

At its basic foundations, criminological displacement theory suggests that when one avenue to commit crime is blocked or made more difficult, offenders may look to alternate methods to commit crime (Reppetto, Citation1976). Traditional views of displacement suggest that displacement is inevitable: if a particular crime is targeted, it will be displaced (Clarke, Citation1980). However, contemporary research show that “crime displacement is the exception rather than the rule” (Eng Leong, Citation2014, p. 26) and that an equally likely consequence of introducing a crime prevention initiative is the diffusion of benefits (the crime problem reduces in the target area and also in areas surrounding the target area). For example, a systematic review of 102 situational crime prevention evaluations by Guerette and Bowers (Citation2009) found that displacement occurred in 26% of cases but diffusion of crime benefits in 27% of cases. Whether or not displacement occurs is shaped by whether there are: (1) motivated offenders; (2) opportunity and (3) familiarity (Guerette & Bowers, Citation2009). In the context of the 2014 Sydney lockouts, all three facilitators for displacement arguably occur: particularly given a large number of alternate entertainment precincts within easy reach of the new lockout zone – including Newtown (see ) – which many patrons are already familiar with.

To date there have been two main analyses regarding potential displacement effects of the Sydney lockouts. The New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) conducted a time series analysis of trends in assault before and after the reforms and found no evidence of displacement (Menéndez, Kypri, & Weatherburn, Citation2017; Menéndez, Tusell, et al., Citation2015; Menéndez, Weatherburn, et al., Citation2015). Instead they found substantially fewer assaults post reform in the target area with no evidence of increases in other entertainment areas in Sydney (including at proximal and distal sites). More recent BOCSAR research (Donnelly, Weatherburn, Routledge, Ramsey, & Mahoney, Citation2016) found evidence of a significant increase in assaults at The Star, a casino (just outside the Sydney CBD entertainment precinct): albeit smaller than the decrease in the lockout zone. In September 2016, the independent review into the lockouts by former High Court Judge Ian Callinan then concluded that: “notwithstanding submissions that Newtown and other places have changed in character” … “the evidence is that there has in fact been little displacement” (Callinan, Citation2016, p. 94). That said, in spite of having the mandate to assess displacement in relation to alcohol-related violence, anti-social behaviour, safety and general amenity, the review focussed almost exclusively on displacement of violence.

Aims

This study sought to explore whether the introduction of the Sydney, NSW lockout legislation in a defined geographic precinct has led to displacement of other types of alcohol-related issues (such as offensive language, offensive conduct, loss of public amenity) from inside to outside the lockout precinct and, if so, what type of displacement has occurred. This was examined in two areas: King’s Cross/Potts Point (as the treatment area) and Newtown (as the catchment area), key sites of public debate about the lockouts.

Methods

The study used four focus groups with residents and patrons: two in Kings Cross/Potts Point and two in Newtown, each of which examined experiences pre and post the 2014 lockout reforms and perceptions of the laws. Focus groups were chosen over other qualitative methods, including face-to-face interviews, as a means to bring a range of stakeholders together, and to comment on and compare each other’s experiences and points of view. As outlined by Kitzinger (Citation1995, p. 299) “the idea behind the focus group method is that group processes can help people to explore and clarify their views in ways that would be less easily accessible in a one to one interview.”

All participants were recruited through flyers, social media and online posts in the two target neighbourhoods including the City of Sydney, Potts Point Residents Association, Newtown Precinct Business Association and Sydney Reddit, with advertisements noting that each would discuss the 2014 Sydney lockout laws. Eligibility criteria for inclusion were that people were aged 18 years or older and were a patron and/or resident of one of the target areas. To ensure a range of perspectives could be captured views were deliberately sought from patrons as well as residents. That said, as shown in the results all but one participant was both a resident and a patron, with many also representing other interest groups (including workers in the night-time economy and members of the GLBTI community). As such, while the original intent was to conduct two or three focus groups in each area, given the diversity of stakeholders and views covered, two per area was deemed sufficient. All focus groups were conducted in June 2015. Importantly, focus groups occurred before the unexpected introduction of a voluntary 3am lockout in Newtown through the Newtown Liquor Accord that was announced on 31 July 2015 and entered into force on 1 September 2015 (Koziol, Citation2015, 31 July).

At each focus group, participants were asked to complete a five minute demographic questionnaire, before taking part in a 40–50 minute focus group that asked participants to describe their entertainment precinct in the months leading up to the 2014 lockouts, and any specific problems observed. They were then asked whether they had observed or experienced any changes in their area since the introduction of the lockouts including: (1) shifts in the late night culture in the area e.g. more/less people or a different demographic; (2) change in patron’s drinking or drug use e.g. more/less drinking; (3) change in the level or type of disorderly conduct late at night e.g. offensive language, offensive conduct and violent behaviour and (4) change in the general amenity or safety of the area. Finally, participants were asked the extent to which they thought any observed changes were attributable to the reform and whether they supported or opposed the lockout laws. The focus groups were audio recorded, transcribed and then thematically coded. This study was approved by the UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee: HC15193.

Results

Focus groups were conducted with 21 participants: 11 from Kings Cross/Potts Point and 10 from Newtown. As noted above, the focus groups participants were a diverse group: for example in addition to all identifying as patrons and/or residents, three participants worked in the night-time economy (NTE) – one as a musician who performed in licenced venues, one as a bar tender and one a bar manager (of venues that traded in the areas targeted by this study), and one participant was a policy advisor who had advised on the development of the lockout laws. The focus groups also included three members of the LGBTI community from inside and outside the lockout zone. As outlined in , the sample had a mean age of 40.3: albeit there was a mix of younger and older stakeholders (range of 18–67 years). All but one participant was both a resident and patron of their area: with the final participant being only a resident. Most had been residents for an average of 12.9 years and a patron for 15.3 years. In the last 12 months 90.5% of the sample reported alcohol consumption, but less than half (42.9%) illicit drug consumption. Comparing the samples by geographic area, participants from Kings Cross/Potts Point were older, and had been resident/patron for more years.

Table 1. Demographics and patterns of drug and alcohol use of the sample and sub-samples.

Kings Cross/Potts Point

The need for intervention

Kings Cross and Potts Point participants reported that preceding the lockouts there were many problems in the night-time economy. For example while participants noted they moved to Kings Cross for the “buzz” and the “diversity” offered by the Kings Cross melting pot (FG2:P5 – male Kings Cross resident/patron), they argued that in the years preceding the lockouts the area had become overrun and unmanageable. For example, they reported that the area was constantly overcrowded:

It’s like emptying the contents of the Sydney Football Stadium onto Kings Cross streets because it’s an entertainment precinct. (FG1:P1 – male Kings Cross resident)

Participants also reported that the crowds were highly intoxicated, aggressive and violent: “angry, tribal drunks” and “aggressive drunks” (FG1:P1, male Kings Cross resident) and that the large number of aggressive people made the area unsafe:

There was a genuine sense of lawlessness up here. The police wouldn’t help for a long time when our property was damaged or venues were clearly in breach of their conditions…. Our back doors were getting bashed in. It really was incredibly unsafe. (FG1:P4 – female Kings Cross resident)

Some reported the safety concerns extended to the daytime economy as well: “there’d be hordes of people on Darlinghurst Road punching each other out at 7 o’clock in the morning” (FG1:P4 – female Kings Cross resident), and a teacher reported that they had had to “hire security guards” to protect students at a local boarding school (FG2:P3 – female Kings Cross resident).

Residents reported a loss of public amenity due to rubbish, human waste, relentless noise and safety concerns. For example, one resident reported having “to hire someone for our building to clean out – it was a public toilet” (FG2:P2 – female Potts Point resident), while another noted “our back doorsteps were being urinated and defecated on” (FG1:P4 – female Kings Cross resident). Others noted the constant noise and loss of sleep:

Our sleep was disrupted every weekend for years because, from 1:30 to 3:30 or 4 o’clock every Saturday and Sunday morning Macleay Street would be bumper to bumper traffic and people would be honking their horns. (FG1:P2 – female Potts Point resident)

Overall, the majority of participants agreed that some form of intervention was necessary to stop the “the wear and tear on residents (and) neighbourhoods” (FG1: P1 – female Kings Cross resident). One participant summarised the combination of the above effects as “the perfect storm” (FG1:P4 – female Kings Cross resident), leaving residents “begging” (FG1:P4) the council and government for an intervention.

Impacts of the lockouts

The focus groups indicated that the introduction of the lockouts had a significant and immediate effect on Kings Cross. Firstly, all participants reported reduced numbers of patrons in the night-time economy in Kings Cross: “there’s still a few of them but they’re not in the football crowd stadium-type numbers that they were” (FG1:P1 – male Kings Cross resident). One Kings Cross bar worker estimated “patronage drop(ped) by about 60 per cent” (FG4:P7 – male, Kings Cross NTE employee).

Kings Cross/Potts Point participants noted that people on the streets in Kings Cross were less intoxicated: “getting on the train it would usually be full of drunks coming in and now it’s not” (FG2:P2 – female Potts Point resident). This was argued to have had positive flow-on effects, improving overall behaviour in the area:

There are less drunk people on the street that’s for certain. And the less drunk people on the street means that everybody is slightly better behaved and those that are drunk look odd and they’re less likely to behave badly. (FG2:P5 – male Kings Cross resident/patron)

Most participants further argued that crime, violence and aggression had fallen: “less fights”, “less brawls” and “less bashings” (FG1:P4 – female Kings Cross resident). Participants reported fewer direct or anecdotal instances of encountering violence since the lockouts. The amenity of the night-time economy in Kings Cross and Potts Point was reported to have improved including through less rubbish and less noise. For example, it was argued: “that noise that used to happen between 11 o’clock and 1 o’clock on Saturday night, that’s all gone” (FG2:P5 – male Kings Cross resident/patron). Participants also noted that they were able to better engage with the local economy and local services:

I walk through Kellett Street, and have a drink, have a coffee with a friend on the way home now. I mean you just couldn’t do that before. (FG1:P4 – female Kings Cross resident)

A few participants did report downsides to the lockout: for example, one GLBTI participant noted that the lockouts were having a detrimental impact on his social life as he was having to go outside the lockout zone to drink or socialise, as the local venues were no longer willing to hold big events (FG2:P5 – male Kings Cross resident/patron). However, overall, the assessment of the lockouts on Kings Cross was positive, with most changes directly attributed to the lockouts: “the turnaround 180 degrees since the lockouts is like day and night” (FG1:P1 – male Kings Cross resident).

When questioned about the potential effect of displacement to other areas of Sydney, opinions were somewhat divided. Some felt that Kings Cross had had enough of the problems and were ambivalent to the notion of displacement: “if it’s a question of displacement, I say bring it on, quite frankly. We’ve done our time and more” (FG1:P2 – female Potts Point resident). But, other participants were concerned about the potential for displacement of problems to other areas:

My hope is that, whilst the benefits that we see – less urination and that – that doesn’t then unfortunately become someone else’s problem. (FG2:P4 – male Kings Cross resident/Newtown patron)

Finally, some argued that if there was evidence of displacement, this was not justification to remove the lockouts – instead it was a justification for their extension:

There’s absolutely no justification to reverse the lockouts. If there’s displacement that only says that … you’ve got to have it (lockouts) across the board. (FG1: P2 – female Potts Point resident)

Changes since reforms – Newtown

In contrast to Kings Cross, the focus groups with Newtown residents and patrons reported that post-lockouts there were many adverse changes in their night-time economy and neighbourhood. They recounted a noticeable increase in the number of patrons attending Newtown. In particular, “getting close to midnight there is an influx of people coming through” (FG3:P1 – male Newtown resident). One musician noted that post-lockouts some local venues went from 30 people to 700 people in the basement alone (FG4, P2 – male Newtown NTE musician/resident/patron), and another who lived opposite a popular pub noted:

The week the lockout laws came into place it went from being fairly relaxed as Newtown kind of was to this absolutely chaotic kind of thing, with a line going all the way down the block. (FG4, P5 – male Newtown resident/patron)

Indeed, two participants who lived or worked in Kings Cross reported that post-lockout they were personally “going to Newtown” more often (FG2:P5 – male Kings Cross resident/patron) as it constituted one of the only viable alternatives to the Kings Cross area:

I am one of those people that likes to go to all night parties, but … the venues that I go to are choosing not to have the parties because the lockout laws are so difficult for them, so I’m going to Newtown. (FG2:P5 – male GLBTI Kings Cross resident/Newtown patron)

I find myself definitely coming here a lot more. Mainly because I finish late at night, or later at night, you know, options around where I am are obviously pretty sparse. (FG4:P7 – male Newtown patron, Kings Cross NTE employee)

That said, that same participant was cognisant that not everyone had been displaced to the Newtown area:

Well, I mean you had 20,000 people in the Cross on a Saturday night, I don’t think they’re all coming to Newtown. Obviously they’ve all dispersed somewhere; they haven’t all taken up knitting. (FG4:P7 – male Newtown patron/Kings Cross NTE employee)

Added to the concerns about the rise in patrons was that the new patrons were not local: “less people from the Inner West and more people from other areas of Sydney” (FG3:P1 – male Newtown resident). They were in turn less responsible for their actions:

It’s not a local crowd so nobody gives a fuck if they start trouble outside because they’re about to get a $60 cab home or whatever. It’s not something they have to worry about. (FG4:P2 – male Newtown resident/patron/musician)

Importantly, people also noted that the new patrons were more judgemental, which was leading to a “clash of cultures”:

The culture here before was quite relaxed, quite accepting of anyone really … but now I feel like there’s a lot more judgement coming though …… There is a sense in the community that it’s under threat. (FG3:P2 – male Newtown resident)

It’s just a different vibe. Newtown has previously been very diverse, welcoming, felt safe walking down the street and it’s that bit of aggression and destructive behaviour that wasn’t part of it … there wasn’t this vibe of walking around looking to smash bottles. (FG4:P8 – male Newtown resident)

Participants argued that patrons on the streets of Newtown were more intoxicated than before the lockouts. Some attributed this to pre-loading (drinking before going out), “there’s a lot more pre-loading going on” (FG4:P1 – male Newtown resident), and patrons having “shots rather than a casual beer” (FG3:P1 – male Newtown resident). But, drug use (particularly crystal methamphetamine or ice) was also reported by some to have become more apparent leading to a “much harder edge” (FG4:P1 – male Newtown resident) in the night-time economy.

All of the Newtown participants raised concerns that the level of aggression in the night-time economy in Newtown had increased. This was primarily reflected in the “vibe” that participants felt at night:

There’s an underlying level of aggression that had not been part of the Newtown, Erskineville and Enmore scene before the lockouts. (FG4:P1 – male Newtown resident)

In turn, the majority of participants argued that Newtown felt less safe than it had before the lockouts: “feel threatened in a way, even if it’s not verbal… there’s a sense of being outnumbered” (FG3:P2 – male Newtown resident):

Would you feel safe if at 3:30am you decide to step out to get milk and you get accosted and poked by a group of young people who are clearly inebriated, intoxicated, with no provocation at all? (FG4:P6 – male GLBTI Newtown resident)

Few participants stated that they had personally seen or experienced any physical violence, but a number including GLBTI residents, recounted incidences of harassment, threats and even personal experiences of assault:

I was living basically opposite the Newtown Hotel right on the street the week the lockout laws came into place… I’d go down to the 7 Eleven and basically get heckled every time – just for my usual grocery shopping. (FG4:P5 – former male Newtown resident)

We were at dinner a few nights ago on Enmore Road and sitting outside and a few guys said some loud inappropriate thing… having a go. I’m literally sitting there eating my kebab, like I’m not even at the bar… and it was early as well… 7pm or something like that. It’s like, its 7pm and I’m having dinner and someone’s already harassing me. Like, come on. (FG4:P2 – male Newtown resident)

I go to the 7 Eleven at the wee hours of the morning because I work late … . Last month a group of young people – 3 guys, 4 girls – out of the blue were passing by the entrance and one of the guys poked me in the chest and said, “What are you doing out late? Go back to your chink cave.” (FG4:P6 – male GLBTI Newtown resident)

Participants further argued that public amenity in Newtown had significantly reduced since the lockouts. One example was damage to property – both public, “they smash street lights, shop signs” (FG4:P6 – male Newtown resident), and private, “we’ve had the tree in front of our house set on fire… people yank the plumbing off our house” (FG4:P8 – female Newtown resident). The level of noise was also reported to be “a lot louder” (FG3:P2 – male Newtown resident/patron). Many Newtown patrons reported they felt less comfortable going out in the main entertainment strip of Newtown. Stakeholders noted that there had been some significant change in the makeup of bars – from small bars and gay bars to large heterosexual bars: “I’ve certainly noticed that the gay bars have been moving back towards a more inclusive sort of thing …. going straight” (FG4: P1 – male Newtown resident). Some residents had thus stopped going out: “I don’t go out any more” (FG4:P6 – male GLBTI Newtown resident), others were going out less often and drinking more at home and still others were changing where they went out, such as by going out further away (e.g. backstreets and surrounding suburbs):

I still go out but have changed where I go out. So still in the area but bars further away from King Street. (FG3:P2 – male Newtown resident/patron)

I’ve certainly been going out a lot less and I’ve found that when I was going out there were a lot more people who were wanting to try something (fight) and it just wasn’t worth it. (FG4:P1 – male Newtown resident/patron)

Overall, the assessment of the lockouts on Newtown was overwhelmingly negative: with all reporting at least some adverse impacts on the area, particularly to a loss of what was special about Newtown. As summed up:

There has traditionally been a vibrancy to Newtown. It was a different crowd approaching it with a different mindset and that seems to have been inundated and overwhelmed. (FG4:P1 – male Newtown resident)

They further directly attributed the changes to the reform. For example, they noted that the adverse impacts were more evident on weekends rather than weekdays, and at night: “it’s mainly at night it’s changed” (FG3:P1 – male Newtown resident). Furthermore, while some residents noted there had been a gradual long-term shift in the area, such as gentrification, there was a very dramatic shift post the lockouts: “since the lockouts it’s been moving in a very different direction” (FG4:P1 – male Newtown resident). Finally, participants who attended both Kings Cross and Newtown noted the stark parallels:

The feeling you get is one that you used to have at 3 o’clock in the Cross …. (only) you’re getting it at 1 o’clock in Newtown, which isn’t something that had been there before. (FG4:P1 – male Newtown resident)

Some noted that the changes following the lockouts had less of a direct impact on them: “I don’t feel like it’s a massive problem for me personally” (FG3:P1 – male Newtown resident). But, were very conscious that they were “less of a target”: as they were not part of a fringe cultural group or the GLBTI or transgender community. That said, it had very direct impacts for a number of participants. For example, a GLBTI resident no longer went out or walked on the main street at night:

I don’t walk on King Street anymore: I walk on back streets … I’ve nearly been run over because it’s so dark but I don’t feel safe walking on King Street anymore. (FG4:P6 – male GLBTI Newtown resident)

Two participants were “thinking about leaving Newtown” (FG4:P6 – male Newtown resident) and one already had moved out:

I came to really despise Newtown and ended up moving out because every night there was just bloodcurdling screams, like, I didn’t have a good night sleep for like 6 months. (FG4:P5 – male Newtown former resident/former patron)

Newtown participants thus argued that the decision to introduce a lockout was poorly thought out, and that the government should have considered other solutions including “better policing”, targeting “identified problem venues” and addressing the culture of violence: rather than just a lockout to shift problems “onto a community that wasn’t equipped to handle it” (FG4:P1 – male Newtown resident):

Over time the Inner West and Newtown in particular has built up a culture and a place where people can be free and be themselves and what’s happened in recent times with violence and people being fearful and shifting the problem … . it’s not a good thing for the area. It’s almost insulting to go “everyone go here” … it’s [a] bandaid fix when they should look at the underlying problem and address that. (FG4:P2 – male Newtown resident)

All participants were further opposed to extending the lockouts to Newtown, arguing that this would punish the local community “for not doing anything wrong” (FG3: P2 – male Newtown resident/patron) and risk “moving” or displacing problems onto other areas, particularly moving the problem “further and further west until it’s not newsworthy” (FG4:P2 – male Newtown resident/patron).

Views of NTE workers

Given that the focus groups included three participants who worked in the Sydney NTE, the final section considers their perspectives on the Sydney 2014 lockouts. Importantly, all recognised there were some “rogue” establishments that tolerated alcohol-related violence in the Sydney NTE:

There are plenty of venues in Kings Cross … where people are glassing each other on a Monday night. (FG4:P7 – male Newtown patron/Kings Cross NTE employee)

There are nice bars (and) there are awful bars … . (FG4:P7 – male Newtown patron/Kings Cross NTE employee)

They further argued that improved responses were warranted in some areas. But, they strongly opposed the Sydney 2014 lockouts. Similarly with the Newtown residents/patrons they concurred that since the lockouts there had been changes in the number of people and demographics in the NTE, with a large shift in patronage from within to outside the lockout zone, and that such areas were ill-equipped to deal with the crowds. Importantly, they also noted three other impacts of the lockouts: which they argued may have long-term detrimental impacts on the NTE. First, the NTE employees noted that the lockouts had made it much harder for many NTE businesses to survive: “it’s certainly damaged the business model a lot” (FG4:P7 – male Newtown patron/Kings Cross NTE employee), including for venues that had already taken a proactive response to alcohol-related problems:

I’ll buck the trend and say maybe the lockouts have a place (for rogue venues)… But, I think if you’re going to apply a blanket approach, its fundamentally unfair. Especially for, as I say, an operator, like the person I work for who has a very, very strong track record on trying to address alcohol-fuelled violence liquor issues. (FG4:P7 – male Newtown patron/Kings Cross NTE employee)

Second, the NTE employees noted that the lockouts had reduced the number of venues playing music as well as opportunities for musicians to work in the Sydney NTE: “Sydney nightlife is, in my opinion as a musician, is pretty much over” (FG4: P2 – male Newtown resident/patron and NTE musician). They further argued that this in turn had encouraged more pubs/venues that were focussed just on drinking and “serving the most drinks”, rather than providing an environment to “break up the drinking”:

One of the issues … is that you don’t have a lot of live music or cultural things to do to break up the drinking … I think that more and more people are just coming here to get drunk … just coming here to get intoxicated. (FG4: P2 – male Newtown resident/patron and NTE musician)

Finally, as demonstrated by one female bar worker the NTE employees noted a decline in personal safety for bar workers working in venues outside the lockout zone:

I was working at the Newtown Hotel when the lockout laws came into effect and there was immediate change, especially the safety for girls. One girl (working at another hotel) got sexually assaulted and raped … a few months after lockouts. There were people everywhere. So we all got warned that we couldn’t walk home from work by ourselves anymore. When I did there was just cars, car full of people yelling and screaming at me, following me and stuff so I didn’t walk home anymore. (FG4:P3 – female former Newtown NTE bar worker)

This led this bar worker to re-locate to working within the lockout zone; an area she stated was “safer”:

I just stopped working in Newtown. I felt more safe in the lockout areas on George Street … than working in Newtown. (FG4: P3 – female Newtown patron/NTE bar worker)

The NTE employees thus concurred with the Newtown patrons/residents that the lockouts were too blunt an instrument to alcohol-related violence, arguing that the government ought to have “identified” and “targeted problem venues” and “problem behaviours” (FG4: P2 – male Newtown resident/patron and NTE musician). They further raised concerns that long-term maintenance of the Sydney lockout laws may impede opportunities for “better” alcohol management in the Sydney NTE.

Discussion

In this article, we used focus groups with residents and patrons in Kings Cross/Potts Point and Newtown to explore whether the introduction of the Sydney alcohol lockout reforms in January 2014 in a geographically defined area resulted in any displacement of alcohol-related problems from within to outside the lockout zone. Comparing the experiences of pre- and post-reform, it is clear that both sites have reported significant changes. On the one hand, stakeholders in the Kings Cross/Potts Point area reported many improvements since the reforms: including reduced patron numbers, reduced aggression, less waste and improved public amenity. On the other hand, stakeholders from Newtown reported many of the opposite effects: increased patron numbers, increased aggression and reduced public amenity. Given the pre-post design, use of two sites and stakeholder views that the changes were by and large attributable to the lockout reforms, rather than some other unrelated factors, this leads us to tentatively suggest that the Sydney lockouts may have contributed towards a partial displacement of patrons and alcohol-related problems from inside the lockout zone to Newtown and that this had led to a number of deleterious impacts on the community, including residents feeling less safe, being harassed, going out less, moving jobs, moving out of the area and a loss of some of the unique and highly inclusive culture of the area.

There are a number of limitations with this study. First, the study measurements of experiences in pre- and post-lockouts were only taken at one time (after the intervention). This necessitates reliance upon recall, which may have encouraged participants to construct retrospective narratives about how things have changed. That said, there was no capacity to conduct a proper “pre-post” design as the lockouts were introduced suddenly and without warning. Second, as a qualitative study with a small sample of participants the results provide tentative rather than definitive evidence of displacement effects. It is also possible that a different group of stakeholders from the two areas may have reported different experiences: particularly a group of patrons only or residents only. That said, an unexpected strength was the diversity of stakeholders including policy makers, bar tenders, musicians, GLBTI members as well as residents and patrons across multiple age groups. Most residents moreover were long-term residents: time enough to put changes in context. More generally with the exception of violence, which as outlined offers a narrow prevue into displacement effects, there are scant quantitative data that can assess many of the impacts that have been addressed by the present study (for some exceptions see: Drug Policy Modelling Program, Citation2016). One final point of note is that since the focus groups were conducted, the majority of late-trading venues in Newtown have introduced a 3am voluntary lockout (albeit 1.5 hours later than the lockout close in Kings Cross). We do not know whether this may have mitigated displacement effects within Newtown (see also below). Further research is thus recommended into such issues.

The findings provide important implications for research and policy. First, the findings are in line with the recent findings of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (Donnelly et al., Citation2016) particularly their newest study released on 6 March 2017 (Donnelly, Poynton, & Weatherburn, Citation2017) (albeit not earlier BOCSAR analyses e.g. Menéndez, Tusell, et al., Citation2015; Menéndez, Weatherburn, et al., Citation2015) that the Sydney lockouts have contributed to a partial but not full displacement of alcohol-related assaults to other entertainment areas. An important proviso to this is that assaults are notoriously under-reported to police, particularly amongst GLBTI communities (Australian Senate Economics References Committee, Citation2016). Equally importantly, the extent of displacement of assaults appears to be growing with time (Donnelly et al., Citation2017). Of note, in BOCSAR’s newest study that examined the impacts of the Sydney lockouts on assaults 32 months post-reform, Donnelly et al. (Citation2017) found that there was a 49% reduction in assaults within the Kings Cross region, but a 12% increase in assaults within the Proximal Displacement Areas (which included The Star Casino and other venues) and a 17% increase in assaults within the Distal Displacement Areas including in Newtown; impacts not observed at earlier time points. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the findings provide the first research evidence supporting claims about other forms of displacement regarding the Sydney, NSW lockouts (City of Sydney, Citation2016; Reclaim the Streets, 2016): particularly increased anti-social and disorderly behaviour, increased drug and alcohol use, increased perceptions of feeling unsafe in the community and reduced public amenity. Coupled with the evidence on the partial displacement of assaults this challenges the conclusion of the independent lockout review that there has definitely been “no displacement” from the lockout laws (Callinan, Citation2016), and suggests the need for a renewed and more comprehensive assessment of the reform impacts.

More generally this adds to the existing studies on lockouts (Miller et al., Citation2016) and those of public drinking bans (Pennay & Room, Citation2012) by showing that consistent with displacement theories, displacement may occur under alcohol-regulations when introduced into a geographically defined area where there is easy opportunity and motivation for patrons to move to alternate venues (Johnson, Guerette, & Bowers, Citation2014). It also adds to some concerns about whether lockouts are the “best” measures: and whether other policy levers including more targeted and venue/problem-specific solutions should be considered by governments that are looking to address alcohol-related violence within a specific entertainment precinct (Weatherburn, Citation2016). This has particularly given the views of the small number of NTE stakeholders in the study who argued that lockouts may reduce opportunities and/or incentives for owners and operators to reduce alcohol-related problems within the NTE. Finally, the study reinforces the importance of valuing communities and community input into the design of alcohol-related policy interventions and evaluations of their worth. How best to do that is something remains a challenge, particularly as ready downplaying of displacement concerns has added to community frustrations about the Sydney lockout experiments.

One quandary is what ought to be done about displacement if it does occur from the Sydney alcohol lockouts? Some participants (from Kings Cross) argued that the lockout zone should be extended, whereas most Newtown participants argued against that, in favour of replacing the lockouts with “better policing”, targeting “identified problem venues” and addressing the culture of violence, responses that were in line with the views of the NTE stakeholders. The Newtown area subsequently voluntarily introduced a lockout, albeit later than in Kings Cross (3am, rather than 1.30am) and across some but not all venues is thus of interest. The stated rationale for the voluntary lockout was to reduce displacement: namely to “ward off late-night revellers and improve safety in the precinct” (Koziol, Citation2015, 31 July). For example, the Newtown Liquor Accord Chairman Tim Claydon said “we're not going to be the last spot for drinks” … “don't even think of heading to Newtown at 3am after a night out in the city, as you simply won't get into venues.” Given, recent reports from the local police that the voluntary lockouts may have reduced anti-social behaviour incidents in the area (Newtown Local Area Command, Citation2015, 2016), this suggests that as conjectured by the focus group participants, expanding lockouts may displace issues onto other entertainment precincts. Whether switching to more targeted responses could produce better outcomes across the Sydney NTE remains unclear.

The findings also raise an important ethical dilemma of “partial displacement” regarding alcohol policy interventions. For example, introducing alcohol policy interventions may lead to greater benefits in one locality (the intervention area) compared to disbenefits occurring in another: from a strictly utilitarian standpoint this can be seen as a net benefit, but it raises the question of what level of displaced disbenefits can and should be tolerated? This question is brought into sharper focus if one views the community receiving disbenefits as one that includes minority groups, especially groups already facing some forms of discrimination (including in this case the LGBTI and transgender community) (Race, Citation2016), thereby fuelling social isolation of already marginalised and stigmatised groups (Australian Senate Economics References Committee, Citation2016). In cases such as this, partial displacement from alcohol policy interventions may be too big a price (Australian Senate Economics References Committee, Citation2016).

Conclusions

This provides tentative evidence that even if the Sydney lockouts have reduced alcohol-related violence there may have been a partial displacement of social problems to outside the lockout zone, namely to Newtown: and that this has fuelled frustration and distress amongst residents of Newtown and antagonism towards the lockout laws. There is a clear need to supplement this study with further qualitative and quantitative research into the Sydney lockouts: but it does raise some questions about the net effectiveness of the reform. More generally, this suggests that future implementations of similar alcohol regulation strategies should be aware of and minimise potential displacement effects on affected communities: particularly if introduced into geographically defined area with easy access to alternate entertainment areas.

Declaration of interest

CEH reports no conflicts of interest. ASWN wrote an earlier one-page parliamentary submission outlining concerns about the Sydney lockout laws (in October 2014). The current study was conducted after that point in time: with the research design, conduct, interpretation and reporting jointly determined by the two study investigators, in accordance with UNSW ethics and UNSW code of conduct.

The Drug Policy Modelling Program is funded by the Colonial Foundation Trust, and is located at the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, a research centre funded by the Australian Government.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to everyone who participated in the focus groups.

References

- Australian Senate Economics References Committee. (2016). Personal choice and community impacts interim report: sale and service of alcohol. Canberra: Australian Parliament House

- Bleetman, A., Perry, C., Crawford, R., & Swann, I. (1997). Effect of Strathclyde police initiative “Operation Blade” on accident and emergency attendances due to assault. Journal of Accident & Emergency Medicine, 14, 153–156. doi: 10.1136/emj.14.3.153

- Callinan, I. (2016). Review of amendments to the Liquor Act 2007 (NSW). Sydney: NSW Department of Justice

- City of Sydney. (2016). Submission to review of the Liquor Amendment Act 2014 by the Hon. IDF Callinan AC QC. Sydney: NSW Department of Justice

- Clarke, R.V. (1980). “Situational” crime prevention: Theory and practice. British Journal of Criminology, 20, 136–147

- Donnelly, N., Poynton, S., & Weatherburn, D. (2017). The effect of lockout and last drinks laws on non-domestic assaults in Sydney: An update to September 2016. Crime and Justice Bulletin No. 201. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

- Donnelly, N., Weatherburn, D., Routledge, K., Ramsey, S., & Mahoney, N. (2016). Did the ‘lockout law’reforms increase assaults at The Star casino, Pyrmont? Crime and Justice Statisics Bureau Brief Issue no. 114. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

- Drug Policy Modelling Program. (2016). Submission to review of the Liquor Amendment Act 2014 by the Hon. IDF Callinan AC QC. Sydney: NSW Department of Justice

- Eng Leong, C. (2014). A review of research on crime displacement theory. International Journal of Business Economics and Research, 3, 22–30. doi: 10.11648/j.ijber.s.2014030601.14

- Google Maps. (2017). Google map: Newtown and sydney lockout zone. Retrieved March 6, 2017 from https://www.google.com.au/maps/

- Guerette, R.T. (2009). Analyzing crime diffusion and displacement Problem-Oriented Guides for Police Problem-Solving Tools: US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services

- Guerette, R.T., & Bowers, K.J. (2009). Assessing the extent of crime displacement and diffusion of benefits: a review of situational crime prevention evaluations. Criminology, 47, 1331–1368. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00177.x

- Hasham, N. (2014, January 21). Restrictions may push Sydney street violence into suburbs, Clover Moore warns, Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/restrictions-may-push-sydney-street-violence-into-suburbs-clover-moore-warns-20140121-316ge

- Howard, S.J., Gordon, R., & Jones, S.C. (2014). Australian alcohol policy 2001–2013 and implications for public health. BMC Public Health, 14, 1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-848

- Johnson, S.D., Guerette, R.T., & Bowers, K.J. (2014). Crime displacement: What we know, what we don't know, and what it means for crime reduction. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 10, 549–571. doi: 10.1007/s11292-014-9209-4

- Keep Sydney Open. (2016). Submission to review of the Liquor Amendment Act 2014 by the Hon. IDF Callinan AC QC. Sydney: NSW Department of Justice

- Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 311, 299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299

- Koziol, M. (2015, July 31). Newtown bars to trial 3am lockout and shots ban, Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/newtown-bars-to-trial-3am-lockout-and-shots-ban-20150731-giomj5.html

- Kypri, K., Jones, C., McElduff, P., & Barker, D. (2011). Effects of restricting pub closing times on night‐time assaults in an Australian city. Addiction, 106, 303–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03125.x

- Kypri, K., McElduff, P., & Miller, P. (2014). Restrictions in pub closing times and lockouts in Newcastle, Australia five years on. Drug and Alcohol Review, 33, 323–326. doi: 10.1111/dar.12123

- Lee, M. (2016). Sydney's lockout laws: For and against. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 28, 117

- Liquor Amendment Act 2014 No 3. (NSW). Retrieved from http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nsw/consol_act/laa2014187/

- McGill, E., Marks, D., Sumpter, C., & Egan, M. (2016). Consequences of removing cheap, super-strength beer and cider: a qualitative study of a UK local alcohol availability intervention. BMJ Open, 6, e010759. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010759

- McMah, L. (2016, February 21). Thousands protest against lockout laws in Keep Sydney Open rally. Retrieved from http://www.news.com.au/national/nsw-act/news/thousands-protest-against-lockout-laws-in-keep-sydney-open-rally/news-story/3093c5f3279899db2fd0132e9d10d5bc

- McNally, L. (2016, February 9). Violence in Sydney down due to lockout laws, NSW Premier Mike Baird says on Facebook, ABC News. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-02-09/violence-in-sydney-down-lockout-laws-mike-baird-says-on-facebook/7152212

- Menéndez, P., Kypri, K., & Weatherburn, D. (2017). The effect of liquor licensing restrictions on assault: a quasi-experimental study in Sydney, Australia. Addiction, 112, 261–268. doi: 10.1111/add.13621

- Menéndez, P., Tusell, F., & Weatherburn, D. (2015). The effects of liquor licensing restriction on alcohol-related violence in NSW, 2008-13. Addiction, 110, 1574–1582. doi: 10.1111/add.12951

- Menéndez, P., Weatherburn, D., Kypri, K., & Fitzgerald, J. (2015). Lockouts and last drinks: The impact of the January 2014 liquor license reforms on assaults in NSW, Australia. Contemporary Issues in Crime and Justice No. 183, 1–12

- Miller, P., Chikritzhs, T., & Toumbourou, J. (2015). Interventions for reducing alcohol supply, alcohol demand and alcohol-related harms Monograph No. 57. Canberra: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre

- Miller, P., Curtis, A., Chikritzhs, T., Allsop, S., & Toumbourou, J. (2016). Interventions for reducing alcohol supply, alcohol demand and alcohol-related harms. Research Bulletin No. 3. Canberra: National Drug Law Enforcement Research Fund

- Newtown Local Area Command. (2015). Newtown – Community Safety Precinct Committee – Minutes 08/10/2015. Newtown: Newtown Local Area Command

- Newtown Local Area Command. (2016). Newtown – Community Safety Precinct Committee – Minutes 10/03/2016. Newtown: Newtown Local Area Command

- NSW Government. (2014). Parliamentary debates, NSW Legislative Assembly, 30 January 2014, Second reading speech – Crimes and Other Legislation Amendment (Assault and Intoxication) Bill and Liquor Amendment Bill 2014 (pp. 26621–26648)

- Palk, G., Davey, J., & Freeman, J. (2010). The impact of a lockout policy on levels of alcohol-related incidents in and around licensed premises. Police Practice and Research, 11, 5–15. doi: 10.1080/15614260802586392

- Pennay, A., & Room, R. (2012). Prohibiting public drinking in urban public spaces: A review of the evidence. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 19, 91–101. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2011.640719

- Race, K. (2016). The sexuality of the night: Violence and transformation. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 28, 105

- Reclaim the Streets. (2016). Submission to review of the Liquor Amendment Act 2014 by the Hon. IDF Callinan AC QC. Sydney: NSW Department of Justice

- Reppetto, T.A. (1976). Crime prevention and the displacement phenomenon. Crime and Delinquency, 22, 166–167. doi: 10.1177/001112877602200204

- The Guardian. (2016, October 9). Thousands rally against lockout laws in Sydney, The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/oct/09/thousands-rally-against-lockout-laws-in-sydney

- Wallace, F., & Koziol, M. (2015, June 21). The new Kings Cross: lockout laws send revellers to Newtown Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/newtown-gets-busy-as-kings-cross-empties-20150619-ghseco

- Weatherburn, D. (2016). The effect of liquor licensing restrictions on assault in the Kings Cross and Sydney CBD entertainment precincts. Paper presented at the Sydney's lockout laws: Cutting crime or civil liberties? Sydney, Australia

- Wilkinson, C., Livingston, M., & Room, R. (2016). Impacts of changes to trading hours of liquor licences on alcohol-related harm: a systematic review 2005–2015. Public Health Research and Practice, 26:e2641644. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17061/phrp2641644