Abstract

Nicotine warning labels on e-cigarette products can inform potential consumers that using e-cigarettes can cause addiction. This study examined awareness of the omnipresence of nicotine in the JUUL e-cigarette through a cross-sectional online survey of 4860 adolescents (13–17 years), 3746 young adults (18–24 years) and 5000 older adults (25–99 years) in the United States. Analyses also examined variation in nicotine awareness as a function of age, ownership, and past 30-day frequency of JUUL use. Results indicated fewer than half of JUUL ever-users and fewer than half of past 30-day JUUL users were aware that JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine. Among JUUL ever-users, awareness of the omnipresence of nicotine in JUUL e-cigarettes was significantly lower among adolescents and those who did not personally own a JUUL. Among past 30-day JUUL users, awareness of the omnipresence of nicotine was significantly lower among adolescents and infrequent users (i.e. used on 1–19 of the past 30 days). Results suggest many users of a JUUL, especially youth, non-owners and infrequent users, may be underestimating their risk of becoming addicted to JUUL products, or overestimating their ability to stop using JUUL products whenever they choose. Reasons for low awareness and methods for increasing public awareness of the omnipresence of nicotine in JUUL products are proposed.

Introduction

It is well-established that nicotine is the major chemical component responsible for addiction to conventional cigarettes and other tobacco products (USDHHS, Citation1988, Citation1994, Citation2010). Though the potential for nicotine addiction varies by the formulation of the nicotine, the dose delivery rate, the rate of absorption of nicotine into the bloodstream, the attained concentration of nicotine, and the frequency and duration of exposure, all products that are made of or derived from tobacco are likely addictive due to the presence of nicotine (Benowitz, Citation1988, Citation2010; Watkins, Koob, & Markou, Citation2000). There is therefore a significant public health benefit to be gained by increasing potential consumers’ awareness of the presence of nicotine in new tobacco products, and increasing their appreciation of the risks for becoming addicted to these products.

Electronic cigarettes (‘e-cigarettes’) are battery-powered devices that can deliver nicotine and flavorings to the user in the form of an aerosol by heating a liquid rather than by burning tobacco. Though e-cigarette aerosol typically contains fewer and lower concentrations of toxicants and carcinogens than are typically carried in smoke from combustible tobacco cigarettes, e-cigarette aerosol is not harmless, and regular, long-term inhalation is unlikely to be without biological effects in humans, and poses unique health and addiction risks during adolescence (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, Citation2018). An estimated 10.8 million adults were current e-cigarette users in 2016, of whom approximately 15% had never smoked a cigarette (Mirbolouk et al., Citation2018). Among all adults, the prevalence of current e-cigarette use was highest among young adults aged 18–24 years (9.2%, or approximately 2.8 million current e-cigarette users in this age range). E-cigarettes’ are also the most commonly used tobacco product among middle and high school students in the United States, and have been so since 2014 (Wang et al., Citation2018). Youth use of e-cigarettes surged considerably between 2017 and 2018, with 4.9% of middle school students and 20.8% of high school students in 2018 estimated to have used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days (compared to 3.3% and 11.7%, respectively, in 2017). These data indicate that around 3.5 million middle and high school students have used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days, up from around 2 million in 2017 (Wang et al., Citation2018). In response to these data, the FDA announced in September 2018 that e-cigarette use among youth had become ‘an epidemic’ (USDHHS, Citation2018).

The wide availability and growth in popularity of e-cigarette and vaping products across the United States has raised the possibility of an expanding population of nicotine consumers if these products are perceived by tobacco non-users, especially youth, to pose low health and addiction risks. Indeed, adolescents who hold lower harm perceptions, lower addiction perceptions, and higher benefit perceptions of e-cigarettes have been found to be more likely to have used, start using, or continue to use e-cigarettes (Amrock, Zakhar, Zhou, & Weitzman, Citation2015; Barrington-Trimis et al., Citation2015; Bernat, Gasquet, Wilson, Porter, & Choi, Citation2018; Owotomo, Maslowsky, & Loukas, Citation2018). E-cigarettes also have potential to increase chronic nicotine exposure in the population of existing tobacco users by expanding the prevalence of use of multiple nicotine-containing products, and to sustain nicotine exposure to tobacco users who may choose to switch from other tobacco products to using e-cigarettes as an alternative to ceasing use of all nicotine-containing products. Warning potential consumers of e-cigarettes and vaping products that these products can and usually do contain nicotine, and that nicotine is a highly addictive substance regardless of how it is delivered, can therefore be an effective means of discouraging initiation or continued use of e-cigarettes, especially among youth, non-users of other tobacco products, and individuals who may underestimate their vulnerability to becoming addicted to nicotine or overestimate their ability to stop using nicotine-containing products.

In May 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), through its Center for Tobacco Products, finalized a rule – referred to as the ‘final deeming rule’ – that deemed all products meeting the statutory definition of ‘tobacco product’ in section 70 201(rr) of the Food Drug & Cosmetic (FD&C) Act (21 U.S.C. 321(rr)) to be subject to chapter IX of the FD&C Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act in 2010. In this final deeming rule, FDA clarified that all electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS: including, but not limited to, e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-hookah, vape pens, personal vaporizers, electronic pipes, and ENDS components and parts (e.g. liquids, cartridges)) were now subject to the FDA’s chapter IX authorities (USDHHS, Citation2016). Section 1143 of the Final Rule required that all ENDS products must include the following warning statement on each product package and in each advertisement: ‘WARNING: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical.’ This warning statement is required to appear on at least 30% of the two principal display panels of the package, and at least 20% of the area of advertisements, and must be indelibly printed on or permanently affixed to packages and advertisements. This nicotine warning label requirement for ENDS products became effective on August 10 2018.

The JUUL nicotine salt pod vaporizer (‘JUUL e-cigarette’) is a temperature-regulated nicotine vaping device that, at 9.45 × 1.50 × 0.69 cm and weighing 100 g, has been described as resembling a USB flash drive in size, weight and appearance. The JUUL e-cigarette is based on a two-part system: a pre-filled, disposable e-liquid pod that clicks into a small battery. All 0.7 mL e-liquid pods marketed by JUUL in the United States are designed to contain either 23-mg of nicotine (3% nicotine by weight) or 40-mg of nicotine (5% nicotine by weight). In addition to the mandatory nicotine warning label, the front panel of the packaging of JUULpods states the ‘nicotine strength’ (expressed as ‘5%’ or ‘3%’) of the contained e-liquid pods, while the back panel lists vegetable glycerin, propylene glycol, benzoic acid, nicotine, and flavorings as the ingredients of JUULpods. For clarity, JUUL Labs Inc. do not currently manufacture e-liquid pods that do not contain nicotine.

Data from a longitudinal online survey of a U.S. national, probability-based cohort of adolescents aged 15–17 years estimate the prevalence of past 30-day use of a JUUL among 15–17 years had significantly increased from 6.0% in February–May 2018 to 7.8% in February–May 2019 (Vallone, Bennett, Xiao, Pitzer, & Hair, Citation2018; Vallone et al., Citation2020). These studies are accompanied by news media reports citing parents, educators, school superintendents, health care providers, and public health experts who claimed the use of JUUL e-cigarettes had become widespread among middle and high school students both within and out-with school premises. In September 2018, FDA announced that much of the increase in youth use of e-cigarettes observed between 2017 and 2018 had been attributable to use of JUUL products (Belluz, 2019; USDHHS, Citation2018). To the extent that the JUUL brand of vaping products has become uniquely popular among U.S. adolescents, the possibility that JUUL products may be expanding the youth population of nicotine consumers at a greater rate compared to other e-cigarette brands provides a strong rationale for research that seeks to quantify and explain youth and young adult consumers’ awareness of the presence of nicotine in JUUL vaping products specifically.

The printing of health warnings on the outer packaging of tobacco products has been shown to be an effective means of increasing the public’s awareness of the health risks associated with smoking tobacco (Bansal-Travers, Hammond, Smith, & Cummings, Citation2011; Hammond, Citation2011; Hammond, Fong, & McNeill, Citation2006, Hammond et al., Citation2007; Hammond et al., Citation2018; Portillo & Antonanzas, Citation2002) and a promising means for influencing harm perceptions and discouraging intentions to initiate e-cigarette use during adolescence (Mays, Smith, Johnson, Tercyak, & Niaura, Citation2016; Sontag, Wackowski, & Hammond, Citation2019; Wackowski, Hammond, O’Connor, Strasser, & Delnevo, Citation2016). The effectiveness of nicotine warning messages in reducing tobacco product use, however, is dependent on these messages being visible to and noticed by potential consumers when they are considering purchasing the tobacco product and/or when they are considering using a product (Sontag et al., Citation2019). For example, ever e-cigarette users who notice warning labels on e-cigarettes have higher odds of knowing e-cigarettes can contain nicotine and for believing e-cigarettes can be addictive. Youth noticing of warning labels on e-cigarette products and recall of nicotine addiction warning labels, however, is low (Sontag et al., Citation2019). Little is known, however, about levels of awareness of the presence of nicotine in specific brands of e-cigarette products, or factors that influence e-cigarette users’ exposure to the nicotine warning label on specific brands of e-cigarette products.

Recent research, however, has established that youth e-cigarette users largely do not directly purchase vaping products themselves, but instead, obtain e-cigarettes primarily from social sources (Tanski et al., Citation2018). Likewise, the majority of youth aged 15–17 years who were currently using JUUL vaping products had not purchased JUUL products directly from retail locations themselves, but rather, had obtained JUUL products primarily or entirely from social sources, the most common source being someone who was asked to buy JUUL products for the user (McKeganey, Russell, Katsampouris, & Haseen, Citation2019). Therefore, though the mandatory nicotine addiction warning label has been printed on the outer packaging of all JUULpods sold in the United States since August 2018, it is possible that users of JUULpods who do not directly purchase these products from retail locations, and users who do not personally own JUULpods (e.g. pods were given by a friend to try), may typically receive or obtain JUULpods absent their original outer packaging. These users may therefore have had only a limited frequency of exposure or zero exposure to the mandatory addictiveness warning on the packaging of JUULpods, and so be less aware of the fact that all JUULpods contain nicotine, and that the nicotine in JUULpods can cause addiction.

The present study examined levels of awareness of the fact that JUUL products always contain nicotine among individuals who have ever used a JUUL and have used a JUUL in the past 30 days. We also examined variation in awareness of the nicotine content of JUUL as a function of age, ownership of a JUUL e-cigarette, and past 30-day frequency of use of a JUUL e-cigarette.

Methods

Participants

Participants were (i) adults aged 18 years and older in the United States who were enrolled as panelists of a Qualtrics internet research panel, and (ii) adolescents aged 13–17 years in the United States who were children of adults who were enrolled as panelists of a Qualtrics’ internet research panel. Qualtrics’ internet research panels comprise a diverse sample of over 30 million adults in the United States who have volunteered to periodically receive invitations to complete surveys online in exchange for incentives. Panelists consent/give assent to each survey they decide to participate in and are free to withdraw from any survey at any time. Only those who reported having heard of or seen e-cigarettes before this study and reported having heard of or seen a brand of e-cigarette called ‘JUUL’ before this study, were eligible to participate.

Recruitment

Recruitment quotas were set with the intention of constructing a non-probability sample that matched the U.S. adolescent population in terms of age, gender and U.S. census region. Additionally, to correct for survey non-response and possible selection bias, a study-specific post-stratification weight was used to adjust the composition of the final sample to match the age, gender and regional distributions of U.S. adolescent population. Demographic and geographic distributions from the March 2017 supplement of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) were employed as population benchmarks for sample recruitment and adjustment, and included gender (male, female), age (13, 14, 15, 16, 17), and census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West).

Adolescent participants were recruited to the study by sending an email invitation to panelists who were identified by Qualtrics as potentially having at least one child aged 13–17 years living in the household. From these email invitations, a total of 14,908 panelists started the survey, of whom 3296 (22.1%) did not have children; 1492 (10.0%) did not have a child aged 13–17 years living in the household; 1618 (10.9%) parents did not give consent for their child to participate; 102 (0.7%) children did not give assent to participate; 458 (3.1%) children screened out due to being unaware of e-cigarettes; and 1555 (10.4%) children screened out due to being unaware of a brand of e-cigarette called ‘JUUL’. Of the 6387 eligible children, 1172 (18.3% of eligible) were screened out due to quota restrictions, 353 (5.5% of eligible) were excluded due to low quality or incomplete responses, and 2 (0.0% of eligible) were excluded for failing to report age. This left a final analytic sample of 4860 (76.1% of eligible) U.S. adolescents (13–17 years) who were aware of e-cigarettes and aware of the JUUL brand of e-cigarettes.

Adult participants were recruited via direct email invitations sent by Qualtrics and via a ‘survey opportunity’ notification posted to online portals to which Qualtrics panelists have access. It was not possible to know how many panelists saw the study invitation posted in the online portals, or how many email invitations were received or read. A total of 26,267 panelists started the survey, of whom 2,159 (8.2%) did not give consent to participate; 134 (5.1%) were not aged 18 years or older; 308 (11.7%) were not residents of the United States; 686 (26.1%) were employees of or related to employees of JUUL Labs Inc. or PAX Labs Inc.); 1645 (6.3%) screened out due to being unaware of e-cigarettes; 6738 (24.3%) screened out due to being unaware of a brand of e-cigarette called ‘JUUL’. Of the 14,597 eligible adults, 5394 (37.0% of eligible) were screened out due to quota restrictions and 458 (3.1% of eligible) were excluded due to low quality or incomplete responses. This left a final analytic sample of 8746 (59.9% of eligible) U.S. adults who were aware of e-cigarettes and aware of the JUUL brand of e-cigarettes, comprised of 3746 young adults (18–24 years) and 5000 older adults (≥ 25 years).

Procedure

To avoid self-selection bias, neither the survey invitation nor the portal notification included specific details about the survey contents or topics. With regard to the adolescent survey, clicking the web-link in the email invitation routed the panelist to an online Parent Permission Form (PPF). This PPF explained that Qualtrics was seeking the panelist’s permission to invite their child to take part in an online survey about their child’s views and experiences of tobacco products, like cigarettes and e-cigarettes. The PPF provided information about the purpose of the study, who was conducting the study, what their child’s participation would involve, what their child would receive for participating, their child’s rights as a study participant – including their right to skip questions or withdraw at any time – how their child’s information would be protected, the contact details of the study director, assurances of participant anonymity and confidentiality, and contact details for the Qualtrics support center and of the Institutional Review Board that was providing oversight of this study. Panelists were asked to allow their child to complete the survey and submit their answers in private.

When a panelist gave consent for their child to participate, the panelist was routed to an online Youth Assent Form (YAF), which they were asked to read and then ask their child to read carefully before deciding whether he/she wished to participate. The YAF provided the same information and assurances as the PPF. The survey took around 25 min to complete. Upon completion, a message displayed thanking participants for their time and informing them that a credit equivalent to $10 would be deposited to their parent’s panel account, and that their parent has been asked to give $10 to the participant.

Adult panelists completed the adult survey by the same procedure, with the exception that adult panelists were routed to an Informed Consent Form by clicking the web-link in the email invitation or portal notification. All surveys were completed online between 20 March and 12 April 2019. This study was approved by Advarra Institutional Review Board (approval no. 00030080, 2 October 2018, and approval no 00032019, 25 January 2019).

Measures

Awareness of e-cigarettes and JUUL e-cigarettes

The following brief description displayed to potential participants on-screen:

Electronic cigarettes or e-cigarettes are electronic devices that produce an aerosol by heating a liquid that usually contains nicotine, flavorings and other additives. Users inhale this aerosol into their lungs.

E-cigarettes come in many shapes and sizes (see image below). Most have a battery, a heating element, and a place to hold a liquid. Some e-cigarettes are made to look like regular cigarettes, while some look like USB flash drives, pens, and other everyday items. Larger e-cigarettes such as tank systems, or ‘mods,’ do not resemble other tobacco products.

E-cigarettes are known by many different names. They are sometimes called ‘e-cigs,’ ‘e-hookahs,’ ‘mods,’ ‘vape pens,’ ‘vapes,’ ‘tank systems,’ and ‘electronic nicotine delivery systems.’ Using an e-cigarette is sometimes called ‘vaping’ or ‘JUULing.’

Some common e-cigarette brands include JUUL, Vuse, Blu, Logic, MarkTen, NJOY, and eGo.

Potential participants were then asked, ‘Have you ever seen or heard of e-cigarettes before this study?’ (yes/no). This description clarified for potential participants that JUUL is a brand of e-cigarette. A similar brief written description of the JUUL e-cigarette was then displayed, following which potential participants were asked, ‘Have you ever seen or heard of a brand of e-cigarette called “JUUL” before this study?’ (yes/no).

Use of a JUUL e-cigarette

Ever use of a JUUL e-cigarette was assessed by the question, ‘Have you ever used a JUUL e-cigarette, even once or twice?’. Participants who responded ‘No’ to this question were defined as ‘never users of a JUUL e-cigarette’. Participants who responded ‘Yes’ to this question were defined as ever users of a JUUL e-cigarette and subsequently asked, ‘When was the last time you used a JUUL e-cigarette, even one or two puffs? (Please choose the first answer that fits)’. Those who responded ‘Earlier today’, ‘Not today but sometime during the past 7 days’ or ‘Not during the past 7 days but sometime during the past 30 days’ were defined as ‘past 30-day JUUL users’. Those who responded ‘Not during the past 30 days but sometime during the past 6 months’, ‘Not during the past 6 months but sometime during the past year’, ‘1 to 4 years ago’ or ‘5 or more years ago’ were defined as ‘former JUUL users’.

Ownership of a JUUL e-cigarette

Participants who reported having ever used a JUUL e-cigarette were asked, ‘Do you own a JUUL e-cigarette?’ (yes/no).

Awareness of the nicotine content of JUUL e-cigarettes

All participants were asked, ‘Which one of the following statements do you believe is true (select one)’. Participants then selected one from five statements: ‘JUUL e-cigarettes _________ contain nicotine’ (always; often; sometimes; rarely; never). Responses to this question were recoded to create a binary variable (0 = incorrect response (often, sometimes, rarely and never); 1 = correct response (always)).

Data analysis

Analysis was restricted to 4860 adolescents (13–17 years), 3746 young adults (18–24 years) and 5000 older adults (25–99 years) who had heard of or seen the JUUL e-cigarette before this study. We report the population-weighted proportions of adolescents, young adults and older adults who reported having ever used a JUUL e-cigarette, having used a JUUL e-cigarette in the past 30 days, and currently owning a JUUL e-cigarette. We also report the proportion of ever-users of a JUUL e-cigarette and the proportion of past 30-day users of a JUUL e-cigarette who reported currently owning a JUUL e-cigarette, by age group Differences in the proportions of each age group reporting each JUUL use status were tested by z tests with a Bonferroni correction.

The association between age group, JUUL ownership and awareness that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’ was examined through two binary logistic regression models, conducted separately for respondents who reported (i) ever use of a JUUL; and (ii) use of a JUUL in the past 30 days. In the first regression model – which was restricted to include only ‘ever-users of a JUUL’ – three variables were entered in step 1: use of a JUUL in the past 30 days (yes vs. no), ownership of a JUUL (owns a JUUL vs. does not own a JUUL) and age group (adolescents vs. young adults vs. older adults). ‘No JUUL use in the past 30 days’, ‘older adults’ and ‘doesn’t own a JUUL’ were specified as the reference categories in the ‘used a JUUL in the past 30 days’, ‘age group’ and ‘ownership of a JUUL’ predictor variables, respectively. An interaction term for age group and ownership of a JUUL was entered at step 2.

In the second regression model – which was restricted to include only ‘past 30-day users of a JUUL’ – three variables were entered in step 1: ownership of a JUUL (owns a JUUL vs. does not own a JUUL), frequency of JUUL use in the past 30 days (infrequent vs. frequent), and age group (adolescents vs. young adults vs. older adults). ‘Doesn’t own a JUUL’, ‘infrequent JUUL user’, and ‘older adults’ were specified as the reference categories in the ownership of a JUUL’, ‘frequency of JUUL use’, and ‘age group’ variables, respectively. An interaction term for age group and ownership of a JUUL was entered at step 2.

All data were population-weighted. Odds ratios in these regression models indicate the proportionate change in a respondent’s odds of correctly reporting that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’ associated with the indicator on the categorical predictor variable. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v.25 software.

Results

Use and ownership of a JUUL E-cigarette

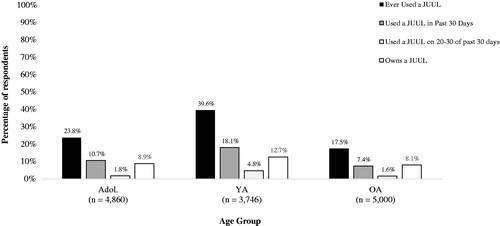

Young adults were significantly more likely than adolescents to have ever used a JUUL (39.6% vs. 23.8%, p < 0.05); in turn, adolescents were significantly more likely than older adults (17.5%) to have ever used a JUUL (p < 0.05) (). Young adults were significantly more likely than adolescents to have used a JUUL in the past 30 days (18.1% vs. 10.7%, p < 0.05); in turn, adolescents were significantly more likely than older adults (7.4%) to have used a JUUL in the past 30 days (p < 0.05). Young adults (4.8%) were significantly more likely than adolescents (1.6%, p < 0.05) and older adults (1.8%, p < 0.05) to have used a JUUL on 20-30 of the past 30 days (i.e. frequent users). Lastly, young adults (12.7%) were significantly more likely than adolescents (8.9%, p < 0.05) and older adults (8.1%, p < 0.05) to personally own a JUUL. Between approximately 60% and 80% of JUUL owners in each age group had not used a JUUL in the past 30 days, suggesting a high rate of former/discontinued JUUL use among those in each age group who owned a JUUL device.

Figure 1. Proportion of adolescents, young adults and older adults who reported ever use, past 30-day any use, past 30-day frequent use, and current ownership of a JUUL e-cigarette. Note. Ns are unweighted; percentages are population-weighted. Key: Adol.: Adolescents (13–17 years); YA: Young Adults (18–24 years); OA: Older Adults (25–99 years).

Among past 30-day users of a JUUL, 62.2% reported owning a JUUL. A significantly higher proportion of older adults than adolescents reported ownership of a JUUL (72.3% vs. 63.6%, p < 0.05); in turn, adolescents were significantly more likely than younger adults to report ownership of a JUUL (55.1%, p < 0.05). That young adults were the most likely to have used a JUUL in the past 30 days but that young adult past 30-day JUUL users were the least likely to personally own a JUUL suggests that social/shared use of a JUUL was most common among young adult past 30-day JUUL users. Lastly, among past 30-day users of a JUUL, 22.1% had used a JUUL on 20-30 of the past 30 days (i.e. frequent JUUL use). Young adult (26.3%) and older adult (24.5%) past 30-day JUUL users were each significantly more likely than adolescent past 30-day JUUL users (15.1%) to be frequent JUUL users (both ps < 0.05).

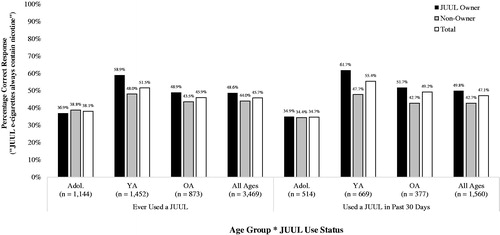

Factors associated with awareness of the nicotine content of JUUL e-cigarettes among ever-users of a JUUL

Rates of correct reporting that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’ by age group (adolescents, young adults, older adults), JUUL use status (ever used, used in past 30 days), frequency of JUUL use in the past 30 days (infrequent use vs. frequent use), and JUUL ownership status (JUUL device owner vs. non-owner) are summarized in . A logistic regression model indicated that, among ever-users of a JUUL (n = 3451), ownership of a JUUL and age group were significantly independently associated with awareness that JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine (Step 1 Wald = 59.34, df = 5, p < 0.001) (). Ever-users of a JUUL e-cigarette who personally owned a JUUL were 23% more likely to correctly report that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’ compared to JUUL ever-users who did not own a JUUL (48.6% correct vs. 44.0% correct: aOR = 1.23; 1.05, 1.44). Compared to older adult JUUL ever-users, adolescent ever-users were 36% less likely to correctly report that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’ (45.9% correct vs. 38.1% correct: aOR = 0.73; 0.61, 0.88). Young adult JUUL ever-users, however, were 29% more likely than older adult ever-users to correctly report that JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine (51.5% correct vs. 45.9% correct: aOR = 1.29; 1.09, 1.53). However, past 30-day JUUL users and former JUUL users (i.e. those who had used a JUUL in the past but not in the past 30 days) had statistically equivalent odds of correctly reporting that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’ (47.1 vs. 44.5: aOR = 1.101; 0.87, 1.18). The interaction term entered at step 2 of the model was also statistically significant (Step 2 Wald = 9.54, df = 2, p = 0.008). However, awareness that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’ did not significantly vary between adolescent JUUL-owners and older adult JUUL-owners (36.9% correct vs. 48.9% correct: aOR = 0.74; 0.51, 1.06) or between young adult JUUL owners and older adult JUUL owners (58.9% correct vs. 48.9% correct: aOR = 1.24; 0.88, 1.76).

Figure 2. Awareness that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’, by age group, JUUL use status and JUUL ownership status. Note. Ns unweighted;%s weighted. Key: Adol.: Adolescents (13–17 years); YA: Young Adults (18–24 years); OA: Older Adults (25–99 years).

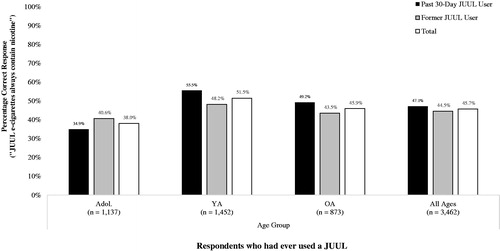

Figure 3. Awareness that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’, by age group and past 30-day use of a JUUL. Note. Ns unweighted;%s weighted. Key: Adol.: Adolescents (13–17 years); YA: Young Adults (18–24 years); OA: Older Adults (25–99 years).

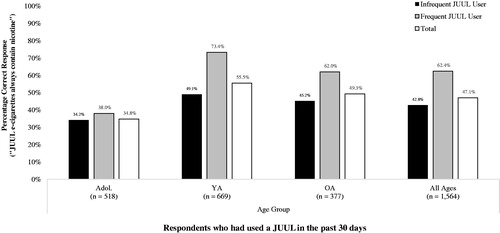

Figure 4. Awareness that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’, by age group and frequency of JUUL use in the past 30 days. Note: Ns unweighted; %s weighted. Key: Adol.: Adolescents (13–17 years); YA: Young Adults (18–24 years); OA: Older Adults (25–99 years).

Table 1. Model information for a binary logistic regression analysis of the likelihood of awareness that JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine among ever-users of the JUUL e-cigarette (n = 3451).

Factors associated with awareness of the nicotine content of JUUL e-cigarettes among past 30-day users of a JUUL

A second logistic regression model indicated that, among respondents whom had used a JUUL in the past 30 days (n = 1558), frequency of JUUL use in the past 30 days and age group were significantly independently associated with awareness that JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine (Step 1 Wald = 92.82, df = 5, p < 0.001) (). Past 30-day frequent users of a JUUL (used on at least 20 of the past 30 days) were 97% more likely to correctly report that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’ compared to past 30-day infrequent users of a JUUL (used on 1–19 of the past 30 days) (62.4% correct vs. 42.8% correct: aOR = 1.97; 1.50, 2.57). Compared to older adult past 30-day JUUL users, adolescent past 30-day JUUL users were 69% less likely to correctly report that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’ (49.2% correct vs. 34.7% correct: aOR = 0.59; 0.44, 0.74). Young adult past 30-day JUUL users, however, were 32% more likely than older adult past 30-day JUUL users to correctly report that JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine (55.4% correct vs. 49.2% correct: aOR = 1.32; 1.01, 1.71). However, owners and non-owners of a JUUL had statistically equivalent odds of correctly reporting that ‘JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine’ (49.8% correct vs. 42.7% correct: aOR = 1.14; 0.91, 1.44). The interaction term entered at step 2 of the model was not statistically significant (Step 2 Wald = 2.40, df = 2, p = 0.301).

Table 2. Model information for a binary logistic regression analysis of the likelihood of awareness that JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine among past 30-day users of the JUUL e-cigarette (n = 1558).

Discussion

Warning potential consumers of tobacco products of the presence of nicotine in these products and that nicotine is an addictive chemical regardless of how it is delivered has been shown to be an effective means of increasing awareness and appreciation of the risk of becoming addicted to tobacco products. Despite the prominent display of a ‘nicotine addiction’ warning label on the two principal panels of the packaging of all JUUL vaping products sold in the United States since August 2018, fewer than half of individuals in this study who had ever used a JUUL e-cigarette, and fewer than half of individuals who had used a JUUL e-cigarette in the past 30 days, were aware that JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine. Among ever-users of a JUUL, awareness of the nicotine content of JUUL e-cigarettes was significantly lower among adolescents and among those who did not personally own a JUUL. Among past 30-day users of a JUUL, awareness of the nicotine content of JUUL e-cigarettes was significantly lower among adolescents and those who had used a JUUL infrequently in the past 30 days. Overall, results suggest that, through a lack of awareness of the fact that JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine, many JUUL users, especially youth, non-owners and infrequent users of a JUUL, may be underestimating their risk of becoming addicted to JUUL products in the future, or overestimating their ability to stop using JUUL products whenever they choose.

Given the unique popularity of the JUUL brand of vaping products in the United States, and with around 8% of 15–17 year olds estimated to have used a JUUL in the past 30 days (Vallone et al., Citation2020), understanding why a high proportion of JUUL users, especially youth, believe at least some JUUL e-cigarettes do not contain nicotine is critical, but likely to be challenging. We offer several hypotheses that together may explain the observed low rates of awareness of the omnipresence of nicotine in JUUL e-cigarettes. First, it is reasonable to hypothesize that individuals’ awareness and recall of the content of nicotine warning labels on JUUL products should improve with repeated exposure to the label. In this study, personally owning a JUUL and using a JUUL more frequently in the past 30 days were found to be important determinants of ever-users and past 30-day JUUL users’ awareness of the omnipresence of nicotine in JUUL e-cigarettes, respectively. Ownership of a JUUL and frequency of JUUL use can both be reasonably considered as proxy measures of an individual’ level of exposure to JUUL products, and so to the packaging in which JUUL products come. The higher rates of awareness of the omnipresence of nicotine in JUUL e-cigarettes observed among individuals who owned a JUUL or had used a JUUL more frequently in the past 30 days may therefore be attributable to these individuals having had more frequent exposure to the packaging of JUUL products in the past 30 days, and so more opportunities to notice and remember the nicotine warning label on JUUL product packaging compared to individuals who were less frequently exposed to JUUL products. This hypothesis requires direct testing, however, because the cross-sectional nature of this survey does not permit conclusions about whether individuals’ awareness of nicotine of JUUL products increased with the frequency of their exposure to and use of JUUL products, or whether JUUL products were used more frequently by these individuals because of their awareness of the nicotine content of these products.

The public health concern raised by the hypothesis that nicotine awareness increases with exposure to and use of JUUL products, however, is the possibility that consumers of JUUL products may only come to be aware of the omnipresence of nicotine in JUUL products after, not before, they have become frequent users or owners of JUUL products. Given the importance of warning potential consumers of the risk of becoming addicted before they initiate use of JUUL products, several actions may be taken to better inform experimental, infrequent and non-owing JUUL users, who account for the majority of ever-users of a JUUL, of the presence and addictiveness of nicotine in all JUUL products.

First, on the assumption that a proportion of infrequent JUUL users and individuals who do not own a JUUL e-cigarette typically obtain JUUL products from social sources – such as sharing with or buying from friends and peers of legal age to purchase tobacco products – there is a reasonable probability that non-owners and infrequent JUUL users may have received their JUUL e-cigarette, and may be receiving JUULpods, absent the original warning-containing outer packaging in which the products were initially purchased. Other individuals may receive JUUL products still in the original outer packaging, but quickly decant these products to their pockets or to another container, and then discard the original packaging. The practice of decanting vaping products from their packaging to their pockets is common among vapers because, unlike a cigarette box which functions as a useful container for loose cigarettes, vaping devices and refill supplies (e.g. e-liquid bottles and pre-filled pods) have less need to be carried in their original packaging once in use, and are actually more convenient to use when not stored/carried in their original packaging. Other JUUL users, especially youth and those who perceive ‘JUULing’ (the use of JUUL products) to be a socially stigmatized behavior, may quickly decant JUUL products from their packaging in order to conceal evidence of their JUUL use from others, such as parents or disapproving friends. In all such cases, individuals who tend to quickly discard the packaging of JUUL products and individuals who typically receive JUUL products absent their original packaging would not be exposed to the manufacturer’s warning of the presence of nicotine in the products they are about to use.

Two actions could be taken to raise awareness of the presence of nicotine in all JUUL products among individuals who never or rarely see the original warning-containing packaging of JUUL products. First, an abbreviated version of the nicotine warning label that is currently displayed on the front and back panels of the outer packaging of JUUL products may be printed onto or permanently affixed to the JUUL vaping device itself. This measure would ensure that individuals’ awareness of the nicotine content of JUUL products is not contingent on their exposure to the packaging of the products. Rather, individuals would potentially be exposed to a nicotine warning label every time they lift a JUUL device to use it, whether or not the device packaging has long since been discarded. This idea has already been piloted in real-world settings, with cconversations about e-cigarette harms, conversations about quitting e-cigarettes, and intentions to quit using e-cigarettes all observed to have increased when e-cigarette warnings were placed on to users’ own vaping devices (Mendel, Hall, Baig, Jeong, & Brewer, Citation2018).

Second, JUUL products could be labelled with a message that more clearly communicates to potential consumers not only that ‘This product contains nicotine’, but that ‘All products made by JUUL contain nicotine’. Such labelling may remove any doubts consumers may have as to whether some JUUL products do contain nicotine while others do not, and more clearly communicate to potential and current consumers that all JUUL products can cause addiction. Thereafter, even if non-owners of a JUUL device and infrequent JUUL users were to only occasionally receive JUUL products in their original warning-containing packaging, even such occasional exposure to the message that ‘All products made by JUUL contain nicotine’ could increase individuals’ awareness of the presence of nicotine in all JUUL products received thereafter, whether still packaged or absent the original packaging, and so better inform individuals’ future decisions about using JUUL products.

While this study provides important first insights into the awareness of the presence of nicotine in all JUUL products among users of these products, the findings must be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, though the study sample was constructed to be representative of U.S. adolescents, young adult and older adults in terms of age, gender, and census region, the generalizability of results to all adolescents, young adult and older adults in the U.S. population may be limited as the study sample was recruited from online research panels, and because approximately 19.6% of adolescents and of 31.6% adults who were otherwise eligible to participate were excluded from the study as they had not seen or heard of a brand of e-cigarette called ‘JUUL’ before taking part in this study. A number of studies have shown, however, that the application of corrections (e.g. quota-based recruitment and population weighting) to nonprobability samples is effective in producing prevalence estimates that match those estimated from probability samples (MacInnis, Krosnick, Ho, & Cho, Citation2018; Yeager et al., Citation2011). Additionally, the corrections applied in this study were specific to the U.S. population, and so results are unlikely to represent levels of awareness of the nicotine content of JUUL products in other countries.

Second, the survey question used in this study to measure respondents’ awareness that all JUUL products always contained nicotine asked: ‘Which one of the following statements do you believe is true (select one): “JUUL e-cigarettes _________ contain nicotine” (response options = always; often; sometimes; rarely; never)’. It is important to stress that this question-response option wording and format is only one of several possible wordings and formats that could acceptably be used to measure JUUL users’ levels of awareness of the presence of nicotine in all JUUL products, and that the reported findings may not hold under different variants in the wording and formats of questions and response options. Third and relatedly, the above question specifically references ‘JUUL e-cigarettes’. While the JUUL e-cigarette is intended to be used only to vape e-liquid pods made by JUUL (‘JUULpods’), there were, at the time of data collection in this study, a small number of manufacturers making and selling pre-filled e-liquid pods that were designed to be compatible with the JUUL e-cigarette. All brands of JUUL-compatible pod that were subsequently discovered to have been available for purchase in the United States at the time of data collection for this study were discovered to have been available in at least one nicotine strength, with most brands offering pods in the same or similar nicotine strengths as are offered in authentic JUULpods. However, we do not know which, if any, of these manufacturers of JUUL-compatible pods also offered a zero-nicotine JUUL-compatible pod option at the time of data collection. Though thought to be unlikely, we therefore cannot rule out the possibility that some individuals in this study may have ever used a JUUL e-cigarette to vape zero-nicotine JUUL-compatible pods. As the number of marketed JUUL-compatible pod brands has increased since April 2019, we recommend that future assessments of the public’s awareness of the nicotine content of JUUL products use survey questions that are worded to specifically ask about ‘JUUL e-cigarettes and e-liquid pods that are made by JUUL (‘JUULpods’). Displaying images of the packaging of the JUUL e-cigarette and JUULpods as accompaniments to survey questions may also help respondents to think about authentic JUUL products as distinct from vaping products that are visually and functionally similar to authentic JUUL products.

Conclusions

Fewer than half of individuals in this study who had ever used a JUUL e-cigarette, and fewer than half of individuals who had used a JUUL e-cigarette in the past 30 days, were aware that JUUL e-cigarettes always contain nicotine. Awareness of the omnipresence of nicotine in JUUL e-cigarettes was lowest among adolescents, individuals who had tried using a JUUL but did not personally own a JUUL, and individuals who used a JUUL infrequently in the past 30 days. These findings should encourage consideration of novel product and packaging-based measures that may more effectively warn potential and current consumers of JUUL products, especially youth and experimental/infrequent users, that all JUUL products contain nicotine and so all JUUL products can cause addiction.

Declaration of interest

In the past 24 months, the employer of NM, CR, and FH, the Centre for Substance Use Research (CSUR), has received funding from JUUL Labs Inc. to independently design and conduct research on the impact of JUUL vapor products on tobacco use behaviors, perceptions, and intentions among adults and adolescents in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank each individual who gave his/her time to participate in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amrock, S.M., Zakhar, J., Zhou, S., & Weitzman, M. (2015). Perception of e-cigarette harm and its correlation with use among U.S. adolescents. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 17, 330–336. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu156

- Bansal-Travers, M., Hammond, D., Smith, P., & Cummings, K.M. (2011). The impact of cigarette pack design, descriptors, and warning labels on risk perception in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40, 674–682. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.021

- Barrington-Trimis, J.L., Berhane, K., Unger, J.B., Cruz, T.B., Huh, J., Leventhal, A.M., … McConnell, R. (2015). Psychosocial factors associated with adolescent electronic cigarette and cigarette use. Pediatrics, 136, 308–317. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0639

- Belluz, J. Scott Gottlieb’s last word as FDA chief: Juul drove a youth addiction crisis. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2019/4/5/18287073/vaping-juul-fdascott-gottlieb

- Benowitz, N. (1988). Pharmacologic aspects of cigarette smoking and nicotine addiction. The New England Journal of Medicine, 319, 1318–1330. doi:10.1056/NEJM198811173192005

- Benowitz, N.L. (2010). Nicotine addiction. New England Journal of Medicine, 362, 2295–2303. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0809890

- Bernat, D., Gasquet, N., Wilson, K.O., Porter, L., & Choi, K. (2018). Electronic cigarette harm and benefit perceptions and use among youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55, 361–367. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.043

- Hammond, D. (2011). Health warning messages on tobacco products: A review. Tobacco Control, 20, 327–337. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.037630

- Hammond, D., Fong, G.T., Borland, R., Cummings, K.M., McNeill, A., & Driezen, P. (2007). Text and graphic warnings on cigarette packages: Findings from the international tobacco control four country study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32, 202–209. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.011

- Hammond, D., Fong, G.T., & McNeill, A. (2006). Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tobacco Control, 15, iii19–iii25. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.012294

- Hammond, D., Reid, J. L., Dreizen, P., Thrasher, J.F., Gupta, P.C., … Borland, R. (2018) Are the same health warnings effective across different countries? An Experimental Study in Seven Countries. Nicotine and Tobacco, 21, 887–895. Retrieved from 101093/ntr/nty248.118

- Macinnis, B., Krosnick, J. A., Ho, A. S., & Cho, M.-J. (2018). The accuracy of measurements with probability and nonprobability survey samples: Replication and extension. Public Opinion Quarterly, 82, 707–744. doi:10.1093/poq/nfy038

- Mays, D., Smith, C., Johnson, A., Tercyak, K., & Niaura, R. (2016). An experimental study of the effects of electronic cigarette warnings on young adult non-smokers perceptions and behavioural intentions. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 14, 17. doi:10.1186/s12971-016-0083-x

- McKeganey, N., Russell, C., Katsampouris, E., & Haseen, F. (2019). Sources of youth access to JUUL vaping products in the United States. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 10. doi:10.1016/j.abrep.2019.100232

- Mendel, J., Hall, M., Baig, S., Jeong, M., & Brewer, N. (2018). Placing health warnings on E-cigarettes: A standardized protocol. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 15, 1578. doi:10.3390/ijerph15081578

- Mirbolouk, M., Charkhchi, P., Kianoush, S., Uddin, S.M.I., Orimoloye, O.A., Jaber, R., … Blaha, M.J. (2018). Prevalence and distribution of E-cigarette use among U.S. adults: Behavioural risk factors surveillance system 2016. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 429. doi:10.7326/M17-3440

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2018. Public health consequences of E-cigarettes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Owotomo, O., Maslowsky, J., & Loukas, A. (2018). Perceptions of the harm and addictiveness of conventional cigarette smoking among adolescent e-cigarette users. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62, 87–93. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.08.007

- Portillo, F., & Antonanzas, F. (2002). Information disclosure and smoking risk perceptions: Potential short-term impact on Spanish students of the New European Union directive on tobacco products. European Journal of Public Health, 12, 295–301. doi:10.1093/eurpub/12.4.295

- Sontag, J., Wackowski, O., & Hammond, D. (2019). Baseline assessment of noticing e-cigarette health warnings among youth and young adults in the United States, Canada and England, and associations with harm perceptions, nicotine awareness and warning recall. Preventive Medicine Reports, 16, 100966. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100966

- Tanski, S., Edmond, J., Stanton, C., Kirchner, T., Choi, K., Yang, L., … Hyland, A. (2018). Youth access to tobacco products in the United States: Findings from wave 1 (2013–2014) of the population assessment of tobacco and health study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 21, 1695–1699. doi:10.1093/ntr/nty238

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1988. The health consequences of smoking: Nicotine and addiction. A Report of the Surgeon General. Retrieved from http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/B/B/Z/D

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1994. Preventing tobacco use among young people. A report of the surgeon general. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53017/

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2010. How tobacco smoke causes disease: The biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease. A report of the surgeon general. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53017

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. 2016. Deeming Tobacco Products To Be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (2016). 21 CFR Parts 1100, 1140, and 1143. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/RulesRegulationsGuidance/ucm394909.htm

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. 2018. FDA statement: Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb MD, on new steps to address epidemic of youth e-cigarette use. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm620185.htm

- Vallone, D.M., Bennett, M., Xiao, H., Pitzer, L., & Hair, E.C. (2018). Prevalence and correlates of JUUL use among a national sample of youth and young adults. Tobacco Control, 29, 1–7. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018–054693

- Vallone, D.M., Cuccia, A.F., Briggs, J., Xiao, H., Schillo, B.A., & Hair, E.C. (2020). Electronic cigarette and JUUL use among adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatrics. Published online January 21, doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5436

- Wackowski, O., Hammond, D., O’Connor, R., Strasser, A., & Delnevo, C. (2016). The impact of E-cigarette warnings, warning themes, and inclusion of relative harm statements on young adults’ E-cigarette perceptions and use intentions. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 13, 655. doi:10.3390/ijerph13070655

- Wang, T.W., Gentzke, A., Sharapova, S., Cullen, K.A., Ambrose, B.K., & Jamal, A. (2018). Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 629–633. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a3

- Watkins, S.S., Koob, G.F., & Markou, A. (2000). Neural mechanisms underlying nicotine addiction: Acute positive reinforcement and withdrawal. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2, 19–37. doi:10.1080/14622200050011277

- Yeager, D. S., Krosnick, J. A., Chang, L., Javitz, H. S., Levendusky, M. S., Simpser, A., & Wang, R. (2011). Comparing the accuracy of RDD telephone surveys and internet surveys conducted with probability and non-probability samples. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75, 709–747. doi:10.1093/poq/nfr020