Abstract

Evidence based strategies are needed to enhance the ability of the Alcohol and Other Drugs (AOD) sector to prevent prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) and harms including Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). In Australia FASD prevention research has largely focused on primary care and child development sectors, while little research has been conducted with AOD services providing comprehensive support to high risk women. This study interviewed 26 staff from 18 organizations involved in referral and co-ordination, case management, or treatment and support services for women with (or at high risk of) PAE in the Greater Newcastle region in Australia. Interviews with service workers indicated a significant appreciation of the psychosocial complexities related to substance misuse in pregnancy, a highly skilled approach to harm reduction, and a sector going to extraordinary lengths to overcome the disadvantages faced by women including gaps in service provision. These results are discussed in light of recommendations to support AOD services to reduce the harms of PAE.

Introduction

Alcohol use during pregnancy is associated with outcomes including miscarriage, stillbirth, premature birth, and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). FASD refers to neurodevelopmental problems that arise from prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE). Diagnostic categories of FASD with, or without three sentinel facial features have been adopted in Australia (Bower & Elliott, Citation2016). The occurrence of FASD across Australia is difficult to estimate due to limited diagnostic capacity, under-reporting of cases, (Burns et al., Citation2013) the difficulty of diagnosing the disorder generally (Roozen et al., Citation2016) and a possible hesitancy of women to report on their alcohol consumption during pregnancy due to fear of negative outcomes (Burns et al., Citation2013). Rates of FASD found in some Australian populations are among the highest in the world (Bower et al., Citation2018; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2017).

Estimates of alcohol use in pregnancy range from 9.8% globally (Popova et al., Citation2017) to between 35.6% and 58.7% in Australia (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, Citation2017; Muggli et al., Citation2016; Popova et al., Citation2017). Women's alcohol consumption during pregnancy is closely related to their preconception consumption, and whether the pregnancy is un/planned (McCormack et al., Citation2017). While most women cease alcohol drinking upon confirmation of pregnancy, about 25% of Australian women continue to drink after pregnancy recognition (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, Citation2017). Women who use alcohol (and similarly other drugs) during pregnancy often face co-occurring difficulties that make abstinence and help seeking difficult (Stone, Citation2015). In a sample of 1400 women at high-risk of an alcohol or drug exposed pregnancy, 87% had parents who used alcohol or drugs, 65% experienced abuse as a child and 26% had experience in the foster care system (Grant & Ernst, Citation2018). Stigmatization and punishment of women who use substances during pregnancy often lead to poor outcomes (Roozen et al., Citation2020) and women may avoid seeking help out of fear that they will be reported to the authorities (Roberts & Pies, Citation2011; Stone, Citation2015) and have children removed from their care (Burns et al., Citation2013). Stigmatization also limits the range of solutions perceived by the public as relevant and effective. Understanding the lived experience of Alcohol and Other Drugs (AOD) use as a journey where people can manage addiction and live rich and meaningful lives is necessary to address stereotypical addiction narratives and reduce the impact of stigma (Fond et al., Citation2017; Pienaar et al., Citation2015).

In Australia several initiatives are underway at national, state, and local levels to reduce the occurrence and impact of FASD, supported by the National FASD Strategic Action Plan 2018–2028 (Commonwealth of Australia Department of Health, Citation2018). Since 2017 significant investment from the Australian Government has been made, with a $25 million (AUD) commitment to FASD prevention being made in 2019. Workforce initiatives are crucial to this plan as primary and antenatal care professionals such as general practitioners (GPs), obstetricians and midwives are in the unique position of having frequent contact with pregnant women, and are trusted by women to provide information, education and referral (Payne et al., Citation2014; Reid et al., Citation2019; Watkins et al., Citation2015). Despite clinical guidelines and research demonstrating that pregnant women expect to be asked about alcohol consumption (Doherty et al., Citation2019), implementation of guidelines has been demonstrated as suboptimal in antenatal care environments (Doherty et al., Citation2019; Elliott, Citation2015; Payne et al., Citation2014). Reasons for this include concern about stigma and patient sensitivity, barriers such as time, perceived lack of skills, and clinical systems incapable of prompting assessment (Kingsland et al., Citation2018; Mutch et al., Citation2012; Payne et al., Citation2011; Watkins et al., Citation2015). Inconsistent evidence on the harms of alcohol use during pregnancy challenges the abstinence message (Mamluk et al., Citation2017; Reynolds et al., Citation2019), and may impede the implementation of recommended guidelines by health professionals and their uptake by pregnant women (Anderson et al., Citation2014; Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b).

The primary care sector and antenatal environments are crucial to enabling early intervention for pregnant women. Referral to services where women can address alcohol use is necessary for women who struggle to cease alcohol drinking throughout their pregnancy, and for those who cease alcohol drinking during pregnancy but risk relapse following the birth of their child (Elliott, Citation2015; Keegan et al., Citation2010). This sector consisting of specialist AOD services is an important but somewhat overlooked workforce that provides comprehensive and quality care in an efficient manner (Duraisingam et al., Citation2020). Models of care in the AOD sector address prevention, harm reduction (Wilson et al., Citation2015) mental health, homelessness, and unemployment (Flatau et al., Citation2013), legal issues, sexual health, and family and domestic violence (Network of Alcohol & Other Drugs Agencies, Citation2016). Strengths-based and trauma informed practice often provide the foundations for service delivery (Fond et al., Citation2017; Network of Alcohol & Other Drugs Agencies, Citation2016). Enhancing the capacity of the AOD workforce to prevent and minimize the harms of PAE has been a focus of national government (Commonwealth of Australia Department of Health, Citation2018; Intergovernmental Committee on Drugs, Citation2014). However, to our knowledge there has been no Australian research investigating support needs of the AOD workforce to reduce harms to high-risk pregnant women.

It has long been acknowledged that AOD workforce initiatives must address the individual, organizational, and systems factors that impact the ability of the workforce to function effectively (Allsop & Stevens, Citation2009; Roche & Nicholas, Citation2017; van de Ven et al., Citation2020). For example, education and training initiatives will have limited effect without consideration of structural factors such as organizational level support or funding availability (Allsop & Stevens, Citation2009; Skelton et al., Citation2017). However for numerous reasons, comprehensive approaches are not always undertaken, and research evidence is lacking (van de Ven et al., Citation2020). A recent systematic review of international research demonstrated that very few studies have examined the relationship between clinical and organizational workforce characteristics and AOD treatment outcomes. A lack of high-quality research, highly variable evidence, and little consideration of intervening or mediating factors (e.g. client attributes and staff training intensity) lead the authors to conclude that the theoretical underpinnings of workforce development and treatment outcomes require greater clarity. To maximize workforce development in AOD services, research must capture the complex interactions between clinician and organizational workforce characteristics, client attributes and treatment outcomes (Horner et al., Citation2019; van de Ven et al., Citation2020; Watkins et al., Citation2015).

The aim of this research was to identify the workforce development needs for prevention of PAE by AOD services in Newcastle, New South Wales (NSW), Australia. This study used qualitative methods to explore the role of the workforce in prevention of PAE, identifying barriers and enablers of care across numerous levels, and highlighting gaps and opportunities for reducing PAE. This research was conducted in the context of implementing FASD prevention activities as part of a wider program in the regionFootnote1.

Material and methods

This research was conducted in Newcastle, a large coastal city in NSW. Research was guided by a community reference group (Local Drug Action Team (LDAT)) comprising community, medical, education, and legal expertise. Governance was provided through a research and FASD prevention collaboration. Ethics approval for this research was obtained via the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (#RA/4/20/5032).

The research was based within a constructivism–interpretivism paradigm, with a focus on understanding the experience of workers in the AOD space (Ponterotto, Citation2005) and recognising the potential for multiple interpretations of the role and needs of the AOD sector (Crotty, Citation1998). The research was guided by many of the methods of grounded theory (Oktay, Citation2012) to build an understanding of the issue informed by frontline staff. Elements of grounded theory employed in the research included allowing the research question to emerge through interaction between the interviews (data collection and analysis) and literature review, refining semi-structured research questions following pilot interviews, and, an inductive approach to data analysis and the conclusions drawn from this process.

A desktop review, community consultation and environmental scan were conducted to identify programs and services that support women who use alcohol who are (or might become) pregnant. A list of key organizations and individuals were compiled from this desktop review. Further information was provided by the LDAT and the local FASD coordinator embedded in the research team. Government services and community managed AOD organizations providing referral and co-ordination, case management, or treatment or support services for high risk women were contacted by phone or face-to-face to participate. Twenty-seven initial contacts from 22 organizations were invited to participate by email, with a follow-up phone call. From these initial contacts, 17 people were interviewed, two referred the request on to another person in the same organization, two declined, and one did not respond. Snowball sampling identified additional personnel and organizations resulting in a further nine interviews. At the end of this process, researchers had conducted 26 interviews with staff members from 18 organizations/departments. provides a description of the roles of participants. Of this sample, only two participants did not directly provide referral and co-ordination, case management, or treatment or support services in their position, however they had oversight over these functions. There were no incentives to participate.

Table 1. Workforce roles of participants.

Semi-structured interview questions were developed with the research project team, the LDAT, and a steering committee. Refinement was undertaken via pilot interviews (2) with partner organizations involved in the research, overseen by senior members of the research team. While the interview schedule focused on the use of alcohol, flexibility ensured that relevant information about other drugs was included given polydrug use is relatively common (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, Citation2017). Interviews were conducted by two female-identifying researchers. The primary interviewer obtained her PhD in Sociology and has experience in conducting qualitative interviews. This interviewer was new to the area at the time of the research and was thus unknown to the interviewees. The second interviewer had many years of experience working in community engagement in the local AOD sector and was therefore known to many of the interviewees. Both interviewers were employed in the not for profit sector. Interviews took place either face to face or by phone, and ran for an average of 39 minutes, ranging from 21 minutes to 65 minutes (Tong et al., Citation2007).

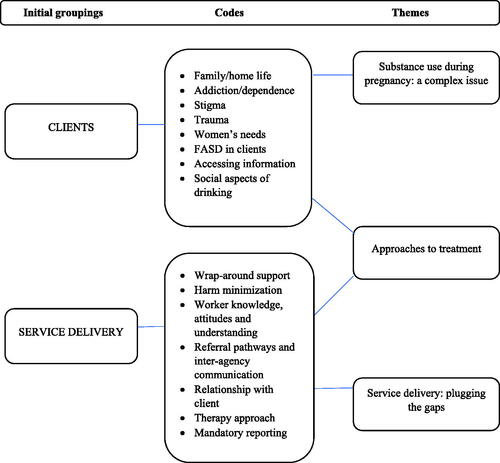

Qualitative data collected from the interviews were recorded, transcribed, and stored on a secure hard drive. Participant checking of transcripts was not conducted (Tong et al., Citation2007). The research used an inductive and reflexive approach to thematic analysis(Braun et al., Citation2019). Open coding was employed initially, with researchers developing a list of descriptive codes from an initial read-through of the transcripts. Transcripts were coded in Excel version 12.1. Emerging themes were identified, and linked back to the literature. In order to organize the data codes were first arranged under two categories that arose from the analysis: codes relating to clients and codes relating to service delivery. This categorization assisted with understanding workforce interaction with clients and additionally with other staff, organizations, and sectors. Further, it clarified aspects of the analysis that related to anecdotal or secondary commentary about women experiencing AOD issues. This was considered pertinent, as the research did not involve women who were themselves accessing services. Codes identified under ‘clients’ included: family/home life; addiction/dependence; stigma; trauma; women’s needs; FASD in clients; accessing information; and social aspects of drinking. Codes identified under ‘service delivery’ included: wrap-around support; harm minimization; worker knowledge; referral pathways; relationship with client; therapy approach; and mandatory reporting. Following the initial coding, the researchers engaged in discussion to develop key themes arising from the research. This thematic analysis was conducted using Excel version 12.1.

Results

Results are arranged below under three key themes. The first theme, ‘Substance use during pregnancy: a complex issue,’ describes the range of issues faced by women accessing AOD services, both at the time of pregnancy and more generally. Theme two ‘Approaches to treatment’ discusses how this complexity informs a multi-skilled approach to treatment and intervention. In theme three, ‘Service delivery: plugging the gaps,’ the challenges faced by the AOD sector are explored. The final thematic structure is presented in with examples described below.

Substance use during pregnancy: a complex issue

Interviewees across the AOD sector in Newcastle highlighted individual, intrapersonal and societal factors that add to the complexity of substance use during pregnancy and women’s willingness to disclose AOD use or engage with treatment. Participants noted that women may feel that their drinking is not a problem due to the legal and social acceptance of alcohol while others might be drinking during the period between conception and confirmation of pregnancy. Other participants stated that under-reporting of alcohol use by women was likely and due to various reasons including stigma, and treatment decisions. These factors were perceived to consequently affect women’s access to appropriate treatment.

Most young women know that drinking alcohol while pregnant is wrong but when you've got a habit and … it's three months into your pregnancy before you even realize that you're pregnant and you've been drinking all that time … It's sort of like we need to get it from an afterthought to a pre-thought. (Source: Interview #4)

[Drinking is] such a social thing, and it's only really recently the guidelines have changed; there's still a lot of people who believe that it's not hurting, or I drank with my other pregnancies and those kids are fine, so I'm only having a couple of beers once a week, what's the problem. (Source: Interview #15)

Participants expressed that women may have used their pregnancy as a motivator to cease alcohol drinking, however this did not necessarily address their long-term needs or ongoing struggle with substance use. Others acknowledged that some women may choose not to proceed with their pregnancy, especially if they have had a ‘chaotic existence’ with drugs and alcohol. Participants also noted that often women may be affected by their own mother’s substance use, or be dealing with the ongoing effects of trauma, including multiple child removals. These factors were perceived to make women ‘service wary’ or ‘service suspicious.’

We'll see women who will say … I stopped when I found out I was pregnant, I stopped using, stopped drinking but then once the baby was born, I couldn't stop myself from picking back up again. (Source: Interview #5)

We have a lady at the moment who is on an opioid treatment program and she was drinking before pregnancy, said she stopped in pregnancy, and then when she found that her methadone dose was not really sufficient and she was having withdrawals, she started to drink really, really heavily - like a litre of wine a day, in her pregnancy. It took her a long time to tell us that that's what she was doing, because she actually didn't want to increase her methadone dose. (Source: Interview #15)

Approaches to treatment

Participants recognized the roles that different health and community services have in FASD prevention and harm minimization, the importance of engaging women with services and treatment, and encouraging better understanding of substance use disorders and their impacts across the workforce and in society generally:

It's such an emotive issue, and any substance use in pregnancy is just such a taboo. Even staff will say I don't understand why they just don't stop, why they can't - you know why are they doing it, why are they harming their baby? … There's a misunderstanding of substance use disorders and addictions … most people do stop, but some can't, and I don't think the general public get that. (Source: Interview #15)

When discussing their approach to treatment, interviewees reported a focus on developing good working relationships with their clients, and asking questions about alcohol use in a non-stigmatizing way that encouraged open communication. Others reported that their treatment approach was focused on understanding the role that alcohol and other drugs has in women’s lives, particularly how substance use interacts with factors such as family violence. Participants who used group therapy emphasized the way that similar experiences helped women to develop broader social support networks. Regardless of the approach, there was a constant focus on individual client’s needs including the acknowledgement of cultural differences, which required a different approach to treatment.

I think the biggest issue for all of us is getting that really transparent, open communication and honest relationship with these mums. … we’re relatively skilled in the art of having difficult conversations. (Source: Interview #28)

I think it's not just alcohol, it's really other drug use as well, increasing our understanding of dangers around other drug use particularly ice because it is so prevalent in our community now. … Women being able to access the support they need around domestic violence and I guess education for our young women around what is - what are the signs of an unhealthy relationship so they can get that early support so that they're not - so that they are able to feel safe when they're pregnant and they're not then needing to turn to substances as a coping strategy. (Source: Interview #5)

We get them to self-reflect on what’s - if it’s alcohol, what does it do for you and if it’s a different substance, what does it do for you, because we’re actually trying to work at meeting the need of the function of the substance. (Source: Interview #9)

Service delivery: plugging the gaps

Participants discussed the structural, systemic and systematic disadvantages that some women faced and the challenges the sector has in responding. Barriers to accessing treatment included the inability of residential detox and rehabilitation services to accommodate women who have parenting responsibilities, lack of housing, violence, and a social services system that ‘persecutes’ those most in need.

There's an acute lack of housing services across the country including in Newcastle, it's very significant. There's some emergency housing but there's big gaps there. … Centrelink benefits haven't risen in real terms for 25 years, so endemic poverty, that's another one. A very unresponsive Centrelink system that has Robodebt and persecutes the most needy of our population, that's another one. Our legal system tends to be biased against people with lack of education and low income. … domestic violence or partner violence or violence from others, that's obviously - women who are pregnant and have some of these problems are at a really big risk. (Source: Interview #16)

Women and children, and particularly women who use substances that need to have their kids with them or provide support to them. Just because your kid's 12 doesn’t mean that you can leave your 12 and 13-year-olds at home to fend for themselves. So there is a gap of support services for women. I think you would have to need a separate service for women with teenagers. (Source: Interview #17)

Strengthening social networks and providing housing, welfare, and other types of wrap-around support were described as integral to women’s recovery. However for this to occur, better communication between services working across both health and the community sectors was noted as crucial.

In my experience, when I worked at the whole family team and I had FACS and the NGOs in the room, no one was really clear that - what their roles were. So, when you tried to have a case conference and say this person needs x, y and z, what do you think you can provide for that? (Source: Interview #21)

Running throughout all interviews was the understanding that there is a significant amount of unmet need. Many participants emphasized the need to do as much as they could as soon as they could, with whatever resources they could manage to place around a woman.

We often run out of rooms and we never I think can offer as much as patients need or be as available as they need us to be. I think the wait time for rehab is crazy … we can do a detox but then they go home to the same environment and nothing really has changed. I guess everything just needs lots of funding. We need more social workers; we need more just everything. But it's an endless problem that will be difficult to fix. (Source: Interview #23)

Discussion

The aim of this research was to understand the support needs of the AOD workforce by identifying barriers and enablers of care in preventing and responding to PAE. Results revealed a highly skilled sector with a significant appreciation of the psychosocial complexities related to substance use in pregnancy. These included cultural norms, client experiences and histories, the physiological nature of addiction, and concerns about stigma. These factors were perceived as influencing women’s disclosure of substance use, their willingness to access treatment, and their immediate and long-term needs. Workers in this study displayed a deep commitment to the women they worked with, often going to extreme lengths to support their clients.

Workforce approaches to addressing PAE were aligned with a focus on harm minimization and engaging and retaining women in treatment. Allocating significant time to build trust with women was crucial to addressing trauma histories and reducing risks to women and their babies. However, there was also a sense that the workforce was under-resourced and unable to address the significant unmet needs of women experiencing substance misuse in pregnancy. It was evident that both gaps in service delivery and the complexity of substance use in pregnant women guided approaches to treatment but seemingly increased the workload of AOD sector workers.

There is a significant shortage of research aiming to understand the workforce development needs of AOD staff who are responding to PAE. However, this study demonstrates some similarities with research findings in general drug treatment settings (Horner et al., Citation2019), and with practitioners in primary and antenatal care environments (Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015a; Watkins et al., Citation2015). Similar factors impacting upon care included constraints on time and resources, sensitivities about stigma, and the importance of both trust and rapport in engaging clients with services and treatment. Role clarification was identified as lacking in the context of multi-agency responses to care by some participants. Structured, positive, and well-coordinated improvements in communication were perceived as necessary between agencies and roles. Previous research with midwives has identified role clarification as capable of predicting intention to implement best practice alcohol screening and referral practices (Watkins et al., Citation2015). Strategies to augment the impact of workforce roles need multifactorial responses and should include organization and management policies to facilitate cross-sector responses (Allsop & Stevens, Citation2009).

Participants reflections on the factors that predispose and exacerbate AOD use in pregnancy include individual influences such as treatment effects and environmental influences found in previous research with pregnant women including persuasive drinking environments (Gibson et al., Citation2019), and inconsistent messages and information (Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015b). Participants were exceptionally mindful of the consequences of these influences describing the impacts on how they work and the women they work with. For example, participants noted it was common for women to perceive pregnancy as a motivating factor for abstinence, but this was often incapable of enabling long term abstinence, highlighting the need for care continuity post birth. Research has indicated that sometimes, the image of a ‘good mother’ is mobilised as a motivating factor in treatment and recovery for substance-dependent women who are also mothers (Kilty & Dej, Citation2012; Radcliffe, Citation2011). However this approach can backfire, as women may become caught in a cycle of ‘abstaining from drugs to be a good mom, while at the same time using drugs to cope with feelings of inadequacy in that role’ (Kilty & Dej, Citation2012).

Negative attitudes towards pregnant women affected by alcohol use were described by participants in public understanding of AOD use – these included by health professionals not working directly with participants. Workers in this study discussed how public stigma may be a barrier to accessing care for some women. Recent research by Corrigan et al. (Citation2017) has demonstrated that mothers of children with FASD are highly stigmatized by the public. Further, stigma towards biological mothers of children with FASD was positively associated with FASD literacy – a finding that conflicts with mental illness and substance use disorders research (Corrigan et al., Citation2019). Results from this qualitative study found that workers self-reported understanding of FASD varied with some participants noting they felt FASD informed, and others describing their understanding as limited. Limited understanding was interpreted by participants as a result of multiple complex factors influencing the relationship between PAE and FASD or discussed in terms of the objective of workforce roles and the scale of concerns needing to be addressed by staff.

This qualitative study demonstrated AOD workforce perceptions of the complex interplay of factors between clients, the sector, and more broadly higher-level policies and structures that impact upon provision of care for pregnant women experiencing or at high-risk of PAE. There are a number of opportunities and recommendations arising from this work to consider in implementation of workforce and service delivery supports, and ongoing research and policy efforts to reduce PAE.

Strengthen capacity of AOD services

Whilst no one system can meet all demand (Roche & Nicholas, Citation2017), AOD use in pregnancy must continue to be on the agenda (Finlay-Jones et al., Citation2020). This study highlighted workers perceptions of significant unmet need in the community and inadequate support to ‘fix’ a never-ending issue. Improvement of interagency communication is needed to strengthen the capacity of the workforce to reduce PAE, and maintain an engaged, supported and stable AOD workforce (Ritter et al., Citation2019; Roche & Nicholas, Citation2017). Current updated models of care are crucial to this endeavor and have been used elsewhere. This however does not address the ongoing need for greater access to detoxification and rehabilitation treatment for women who have children.

Provision of family planning services and child sensitive services post birth and throughout the early years of child development

In the context of high rates of unplanned pregnancies and PAE prior to recognition of pregnancy, family planning approaches should be integrated with AOD workforce initiatives. Change at this level will likely have greater impacts than any training or education initiative concerning PAE. Whilst pregnancy is often a motivator for women to address alcohol use, this study noted that relapse was common and mothers face specific challenges engaging with treatment. Supporting women post-birth is crucial, and ensuring continued access to a comprehensive range of well-connected services (e.g. social support, case management, and mental health services) is necessary through the early years of child development (Breen et al., Citation2014). Child sensitive service provision includes programs that focus on the mother and child, home visits, practical strategies such as transport, childcare, and support to link with treatment services, support groups and residential treatment allowing children to reside with their mothers (Network of Alcohol & Other Drugs Agencies, Citation2016). The Health sector in Newcastle has worked over recent years to address such service gaps. Through the Substance Use in Pregnancy and Parenting clinic [SUPPS], the local hospital has capacity to coordinate pregnancy care with substance misuse treatments, and to follow up with new mothers following delivery.

Evaluation of programs need to be prioritized and funded accordingly

The FASD Strategic Action Plan calls to evaluate, promote and further develop prevention, management, and support models to prevent alcohol drinking in pregnancy. The AOD sector need to be included in this effort with adequate funding to support and evaluate activities. Recent work in the Newcastle area has ensured that screening for alcohol is incorporated into health care provided to pregnant women accessing antenatal services (Kingsland et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). Elsewhere, evidenced-based programs such as the Parent-Child Assistance Program (PCAP) provide a three‐year home visitation model, implemented by highly trained, clinically supervised case managers (Grant et al., Citation2014; Grant & Ernst, Citation2017).

Address public stigma in prevention efforts

Stigma is reflected in public understanding of AOD use as a result of poor decision making on behalf of the mother. This type of stigma limits the options seen as effective by the public to those that focus on punitive strategies to shape behavior (Fond et al., Citation2017). Ways to overcome stigma include reframing public health messages about harm to messages that focus on promoting self-efficacy (Roozen et al., Citation2020), wellbeing, and social and biological factors that step away from individualism (Fond et al., Citation2017; Roozen et al., Citation2020). Additional strategies include mobilizing social support, empowering stigmatized individuals, and via social norms and policies (Roozen et al., Citation2020). For such initiatives to be successful, trust, openness, and positive support are required. The AOD sector and women who access these services must be involved in developing these initiatives given their understanding and experiences of stigma and PAE.

Limitations

There are some limitations in this study that must be acknowledged. This study focused on government services or community managed AOD organizations in a regional hub and may affect the transferability of findings. Meaningful comparisons between specific workforce roles in this sample could not be made due to sample size. As such there may be barriers to care that need further exploration and clarification. Finally, while this work did not incorporate the voices of women and families impacted by PAE, it should be noted that these perspectives are critical to the development of effective programs and services (Anderson et al., Citation2014; McBride et al., Citation2012).

Conclusion

The AOD workforce in Newcastle provides a non-judgmental and determinants-focused approach to care and harm minimization for women with AOD use or dependence in pregnancy. However, the sector experiences challenges, including under resourcing, high demand, and the presence of public stigma towards help-seekers. Interviews indicated a number of needs to be addressed in order to optimize the role of the AOD sector in preventing alcohol use in pregnancy, including increased funding, strengthening of inter-sectoral approaches, and systemic change to facilitate communication between sectors. Future research in this sector and complementary services is warranted in particular initiatives that include and respond to the experiences of pregnant women accessing AOD services.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the dedicated staff who participated in this research study and the expertise provided by the Local Drug Action Team in Newcastle whose members included Tony Brown (LDAT Chair), Elvira Johnson (Mercy Services), Dr Murray Webber (Clinical Lead, Pediatrics HNE Kids Health, John Hunter Children's Hospital), Conjoint Associate Professor Adrian Dunlop (Hunter New England Health District and University of Newcastle), Deborah Rowe (Youth Justice Conference Convenor), and Catherine Norman (LDAT Secretary), for their continued advice throughout the life of the project.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Making FASD History: A multi-site prevention program https://alcoholpregnancy.telethonkids.org.au/our-research/research-projects/making-fasd-history-multi-sites/

References

- Allsop, S. J., & Stevens, C. F. (2009). Evidence-based practice or imperfect seduction? Developing capacity to respond effectively to drug-related problems. Drug and Alcohol Review, 28(5), 541–549. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00110.x

- Anderson, A. E., Hure, A. J., Kay-Lambkin, F. J., & Loxton, D. J. (2014). Women's perceptions of information about alcohol use during pregnancy: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 14, 1048. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1048

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2017). National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2016: detailed findings. Drug Statistics series no. 31. AIHW. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/ndshs-2016-detailed/contents/table-of-contents

- Bower, C., Elliott, E. (2016). Report to the Australian Government of Health: Australian Guide to the diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). https://alcoholpregnancy.telethonkids.org.au/contentassets/6bfc4e8cd1c9488b998d50ea4bff9180/australian-guide-to-diagnosis-of-fasd_all-appendices.pdf

- Bower, C., Watkins, R. E., Mutch, R. C., Marriott, R., Freeman, J., Kippin, N. R., Safe, B., Pestell, C., Cheung, C. S. C., Shield, H., Tarratt, L., Springall, A., Taylor, J., Walker, N., Argiro, E., Leitão, S., Hamilton, S., Condon, C., Passmore, H. M., & Giglia, R. (2018). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and youth justice: A prevalence study among young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia. BMJ Open, 8(2), e019605. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019605

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Springer.

- Breen, C., Awbery, E., & Burns, L. (2014). Supporting pregnant women who use alcohol or other drugs: A review of the evidence. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre.

- Burns, L., Breen, C., Bower, C., O'Leary, C., & Elliott, E. J. (2013). Counting Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in Australia: The evidence and the challenges. Drug and Alcohol Review, 32(5), 461–467. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12047

- Commonwealth of Australia Department of Health. (2018). National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Strategic Action Plan 2018–2028. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/national-fasd-strategic-action-plan-2018-2028.pdf; http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/55E4796388E9EDE5CA25808F00035035/%24File/National%20Fetal%20Alcohol%20Spectrum%20Disorder%20Strategic%20Action%20Plan%202018-2028.pdf

- Corrigan, P., Lara, J. L., Shah, B. B., Mitchell, K. T., Simmes, D., & Jones, K. L. (2017). The public stigma of birth mothers of children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 41(6), 1166–1173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13381

- Corrigan, P., Shah, B. B., Lara, J. L., Mitchell, K. T., Combs-Way, P., Simmes, D., & Jones, K. L. (2019). Stakeholder perspectives on the stigma of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Addiction Research & Theory, 27(2), 170–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2018.1478413

- Crawford-Williams, F., Steen, M., Esterman, A., Fielder, A., & Mikocka-Walus, A. (2015a). “If you can have one glass of wine now and then, why are you denying that to a woman with no evidence”: Knowledge and practices of health professionals concerning alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Women and Birth : Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 28(4), 329–335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2015.04.003

- Crawford-Williams, F., Steen, M., Esterman, A., Fielder, A., & Mikocka-Walus, A. (2015b). “My midwife said that having a glass of red wine was actually better for the baby”: A focus group study of women and their partner's knowledge and experiences relating to alcohol consumption in pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 79 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0506-3

- Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. Sage.

- Doherty, E., Wiggers, J., Wolfenden, L., Anderson, A. E., Crooks, K., Tsang, T. W., Elliott, E. J., Dunlop, A. J., Attia, J., Dray, J., Tully, B., Bennett, N., Murray, H., Azzopardi, C., & Kingsland, M. (2019). Antenatal care for alcohol consumption during pregnancy: Pregnant women's reported receipt of care and associated characteristics. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 19(1), 299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2436-y

- Duraisingam, V., Roche, A. M., Kostadinov, V., Hodge, S., & Chapman, J. (2020). Predictors of work engagement among Australian non-government drug and alcohol employees: Implications for policy and practice. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 76, 102638. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.102638

- Elliott, E. J. (2015). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in Australia – The future is prevention. Public Health Research & Practice, 25(2), e2521516. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp2521516

- Finlay-Jones, A., Elliott, E. J., Mayers, D., Gailes, H., Sargent, P., Reynolds, N., Birda, B., Cannon, L., Reibel, T., McKenzie, A., Jones, H., Mullan, N., Tsang, T. W., Symons, M., & Bower, C. (2020). Community priority setting for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Research in Australia. International Journal of Population Data Science, 5(3). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23889/ijpds.v5i3.1359

- Fitzpatrick, J. P., Latimer, J., Olson, H. C., Carter, M., Oscar, J., Lucas, B. R., Doney, R., Salter, C., Try, J., Hawkes, G., Fitzpatrick, E., Hand, M., Watkins, R. E., Tsang, T. W., Bower, C., Ferreira, M. L., Boulton, J., & Elliott, E. J. (2017). Prevalence and profile of neurodevelopment and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) amongst Australian Aboriginal children living in remote communities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 65, 114–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.04.001

- Flatau, P., Conroy, E., Thielking, M., Clear, A., Hall, S., Bauskis, A., & Burns, L. (2013). How integrated are homelessness, mental health and drug and alcohol services in Australia? Australian Housing & Urban Research Institute.

- Fond, M., Kendall-Taylor, N., Volmert, A., Gertein Pineau, M., & L’Hôte, E. (2017). Seeing the spectrum: Mapping the gaps between expert and public understandings of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in Manitoba.

- Gibson, S., Nagle, C., Paul, J., McCarthy, L., & Muggli, E. (2019). Pregnant women’s understanding and conceptualisations of the harms from drinking alcohol: a qualitative study. bioRxiv, 815209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1101/815209

- Grant, T., Ernst, C. (2018). Parent-Child Assistance Program (PCAP): Prevention & intervention with high risk mothers and their children. http://depts.washington.edu/pcapuw/inhouse/PCAP_Summary_of_Evidence.pdf

- Grant, T., Ernst, C. C. (2017). Parent-Child Assistance Program (PCAP) 1991 – Present: Prevention & intervention with high-risk mothers and their children. http://depts.washington.edu/pcapuw/inhouse/PCAP_Summary_of_Evidence_2.8.17.pdf

- Grant, T., Graham, J., Ernst, C. C., Peavy, K., & Brown, N. (2014). Improving pregnancy outcomes among high-risk mothers who abuse alcohol and drugs: Factors associated with subsequent exposed births. Children and Youth Services Review, 46(Supplement C), 11–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.07.014

- Horner, G., Daddona, J., Burke, D. J., Cullinane, J., Skeer, M., & Wurcel, A. G. (2019). “You’re kind of at war with yourself as a nurse”: Perspectives of inpatient nurses on treating people who present with a comorbid opioid use disorder. PLoS One, 14(10), e0224335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224335

- Intergovernmental Committee on Drugs. (2014). National alcohol and other drug workforce development strategy 2015–2018.

- Keegan, J., Parva, M., Finnegan, M., Gerson, A., & Belden, M. (2010). Addiction in pregnancy. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 29(2), 175–191. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/https://doi.org/10.1080/10550881003684723?needAccess=true https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10550881003684723

- Kilty, J. M., & Dej, E. (2012). Anchoring amongst the waves: Discursive constructions of motherhood and addiction. Qualitative Sociology Review, 8(3), 6–23.

- Kingsland, M., Doherty, E., Anderson, A. E., Crooks, K., Tully, B., Tremain, D., Tsang, T. W., Attia, J., Wolfenden, L., Dunlop, A. J., Bennett, N., Hunter, M., Ward, S., Reeves, P., Symonds, I., Rissel, C., Azzopardi, C., Searles, A., Gillham, K., Elliott, E. J., & Wiggers, J. (2018). A practice change intervention to improve antenatal care addressing alcohol consumption by women during pregnancy: Research protocol for a randomised stepped-wedge cluster trial. Implementation Science : IS, 13(1), 112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0806-x

- Kingsland, M., Doherty, E., Anderson, A., Tully, B., Crooks, K., Elliott, E., Wolfenden, L., Dunlop, A., Tsang, T., Rissel, C., Symonds, I., Attia, J., Azzopardi, C., & Wiggers, J. (2019). Developing a practice change initiative to improve care for alcohol consumption in pregnancy. Women and Birth, 32, S33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2019.07.244

- Mamluk, L., Edwards, H. B., Savović, J., Leach, V., Jones, T., Moore, T. H. M., Ijaz, S., Lewis, S. J., Donovan, J. L., Lawlor, D., Smith, G. D., Fraser, A., & Zuccolo, L. (2017). Low alcohol consumption and pregnancy and childhood outcomes: Time to change guidelines indicating apparently 'safe' levels of alcohol during pregnancy? A systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open, 7(7), e015410. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015410

- McBride, N., Carruthers, S., & Hutchinson, D. (2012). Reducing alcohol use during pregnancy: Listening to women who drink as an intervention starting point. Global Health Promotion, 19(2), 6–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975912441225

- McCormack, C., Hutchinson, D., Burns, L., Wilson, J., Elliott, E., Allsop, S., Najman, J., Jacobs, S., Rossen, L., Olsson, C., & Mattick, R. (2017). Prenatal alcohol consumption between conception and recognition of pregnancy. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 41(2), 369–378. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13305

- Muggli, E., O’Leary, C., Donath, S., Orsini, F., Forster, D., Anderson, P. J., Lewis, S., Nagle, C., Craig, J. M., Elliott, E., & Halliday, J. (2016). “Did you ever drink more?” A detailed description of pregnant women’s drinking patterns. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3354-9

- Mutch, R., Wray, J., & Bower, C. (2012). Recording a history of alcohol use in pregnancy: an audit of knowledge, attitudes and practice at a child development service. Journal of Population Therapeutics & Clinical Pharmacology, 19(2), e227–e233.

- Network of Alcohol and Other Drugs Agencies. (2016). Women’s AOD services network: Gender responsive model of care.

- Oktay, J. S. (2012). Grounded theory. Oxford University Press.

- Payne, J. M., France, K. E., Henley, N., D'Antoine, H. A., Bartu, A. E., Mutch, R. C., Elliott, E. J., & Bower, C. (2011). Paediatricians' knowledge, attitudes and practice following provision of educational resources about prevention of prenatal alcohol exposure and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 47(10), 704–710. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02037.x

- Payne, J. M., Watkins, R. E., Jones, H. M., Reibel, T., Mutch, R., Wilkins, A., Whitlock, J., & Bower, C. (2014). Midwives' knowledge, attitudes and practice about alcohol exposure and the risk of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, 377–389. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-014-0377-z

- Pienaar, K., Fraser, S., Kokanovic, R., Moore, D., Treloar, C., & Dunlop, A. (2015). New narratives, new selves: Complicating addiction in online alcohol and other drug resources. Addiction Research & Theory, 23(6), 499–509. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2015.1040002

- Ponterotto, J. G. (2005). Qualitative research in counseling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.126

- Popova, S., Lange, S., Probst, C., Gmel, G., & Rehm, J. (2017). Estimation of national, regional, and global prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy and fetal alcohol syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Global Health, 5(3), e290–e299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30021-9

- Popova, S., Lange, S., Probst, C., Parunashvili, N., & Rehm, J. (2017). Prevalence of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders among the general and Aboriginal populations in Canada and the United States. European Journal of Medical Genetics, 60(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.09.010

- Radcliffe, P. (2011). Motherhood, pregnancy, and the negotiation of identity: The moral career of drug treatment. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 72(6), 984–991. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.017

- Reid, N., Gamble, J., Creedy, D. K., & Finlay-Jones, A. (2019). Benefits of caseload midwifery to prevent Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: A discussion paper. Women and Birth : Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 32(1), 3–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.03.002

- Reynolds, C. M., Egan, B., O’Malley, E. G., McMahon, L., Sheehan, S. R., & Turner, M. J. (2019). Fetal growth and maternal alcohol consumption during early pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 236, 148–153. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.02.005

- Ritter, A., Chalmers, J., & Gomez, M. (2019). Measuring unmet demand for alcohol and other drug treatment: The application of an Australian population-based planning model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement, (s18), 42–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.42

- Roberts, S. C., & Pies, C. (2011). Complex calculations: How drug use during pregnancy becomes a barrier to prenatal care. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(3), 333–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0594-7

- Roche, A., & Nicholas, R. (2017). Workforce development: An important paradigm shift for the alcohol and other drugs sector. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 24(6), 443–454. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2016.1262823

- Roozen, S., Black, D., Peters, G.-J Y., Kok, G., Townend, D., Nijhuis, J. G., Koek, G. H., & Curfs, L. M. G. (2016). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD): An approach to effective prevention. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 3(4), 229–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-016-0101-y

- Roozen, S., Stutterheim, S. E., Bos, A., Kok, G., & Curfs, L. (2020). Understanding the social stigma of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: From theory to interventions. Foundations of Science. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-020-09676-y

- Skelton, E., Tzelepis, F., Shakeshaft, A., Guillaumier, A., Dunlop, A., McCrabb, S., Palazzi, K., & Bonevski, B. (2017). Addressing tobacco in Australian alcohol and other drug treatment settings: A cross-sectional survey of staff attitudes and perceived barriers. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 12(1), 20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-017-0106-5

- Stone, R. (2015). Pregnant women and substance use: Fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health & Justice, 3(1), 2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-015-0015-5 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-015-0015-5

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- van de Ven, K., Ritter, A., & Roche, A. (2020). Alcohol and other drug (AOD) staffing and their workplace: Examining the relationship between clinician and organisational workforce characteristics and treatment outcomes in the AOD field. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 27(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2019.1622649

- Watkins, R. E., Payne, J. M., Reibel, T., Jones, H. M., Wilkins, A., Mutch, R., & Bower, C. (2015). Development of a scale to evaluate midwives’ beliefs about assessing alcohol use during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0779-6

- Wilson, D. P., Donald, B., Shattock, A. J., Wilson, D., & Fraser-Hurt, N. (2015). The cost-effectiveness of harm reduction. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, S5–S11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.11.007