Abstract

The transition to fatherhood may present a ‘teachable moment’ when men evaluate their health behaviors. This scoping review synthesizes evidence on men’s experiences of alcohol consumption in the context of fatherhood, and on interventions to reduce drinking among new fathers. We searched four databases and reference lists to identify eligible studies. The review findings were discussed with key stakeholders. The review identified five articles published in peer-reviewed journals, and one protocol. Three qualitative studies explored fathers’ experiences of alcohol consumption. They suggest that men may reduce their drinking to support their pregnant partner, and that some men believe fathers should be role models for their children. The two intervention studies suggest that text message interventions may be successful in engaging men. However, their effectiveness in addressing alcohol use in fathers is unclear. Only one study evaluated intervention effectiveness and this was a couple-based smoking intervention, that led to reduction in drinking.

This review found that it is feasible to recruit fathers through gatekeepers and venues where fathers may go (e.g. antenatal clinics). This scoping review highlights the scarcity of research on fathers’ experiences of alcohol use and on interventions to support new fathers to reduce alcohol consumption.

Introduction

Alcohol is a key risk factor for overall burden of disease across Europe (WHO, Citation2019). Harmful patterns of drinking are particularly problematic among men, compared to women. For example, men’s average level of drinking was nearly four times higher than that of women in Europe in 2016 (18.3 liters and 4.7 liters of pure alcohol per year for men and women respectively) (WHO, Citation2019).

One important way to address hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption among men is to capitalize on key transitions in men’s life, that may serve as ‘teachable moments’ for behavior change. Becoming a father is an example of such teachable moment. The transition to fatherhood may be a catalyst for men to evaluate their lifestyle, modify existing behaviors and adopt new ones (e.g. increase physical activity; decrease ‘risky’ behaviors) (Bodin et al., Citation2017; Garfield et al., Citation2010; Olsson et al., Citation2010). Motivators for behavior change may include prioritizing the needs of the family and being a good role model (Garfield et al., Citation2010). However, many fathers continue to drink during and after pregnancy (Bailey et al., Citation2008; Condon et al., Citation2004; Everett et al., Citation2007; Högberg et al., Citation2016; McBride & Johnson, Citation2016). Research suggests that when men drink alcohol during pregnancy, this increases the likelihood of their partner also drinking and negatively affects relationship quality (Desrosiers et al., Citation2016; McBride & Johnson, Citation2016).

For some men, the stress of becoming a father and the need to manage competing social demands may present barriers to positive behavior change. Instead, negative health behaviors such as drinking, may become forms of ‘hedonistic’ escape (Robertson, Citation2007; Williams, Citation2007). For example, in a qualitative study with parents of children aged 10 years or younger, Wolf and Chavez (Citation2015) found that fathers often drank to relax, although they negotiated decisions around drinking with parenting responsibilities. Another explanation could be that health behaviors are used to construct men’s identities (Emslie et al., Citation2013; Kwon et al., Citation2015). For example, Gordon et al. (Citation2013) found that young men who endorsed the idea that a man should be emotionally, physically and mentally tough, engaged in health undermining behaviors.

Therefore, it is important to explore whether and for whom becoming a father is a teachable moment, when men are more likely to engage with lifestyle advice and change their drinking behavior. Understanding if and how men’s drinking changes when they become fathers can inform interventions and guide best practice on supporting new fathers to reduce hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption. Reducing/quitting alcohol consumption in the pre- and post-natal period is likely to have benefits for men, their partners and children.

This scoping review synthesizes evidence on the impact of becoming a father on men’s alcohol consumption and on the effectiveness of existing interventions to reduce drinking among new fathers. The review aims to answer the following questions:

What are men’s experiences of alcohol consumption in the context of becoming a father?

What are the key characteristics of existing interventions to target alcohol consumption in new fathers?

What are the best ways to engage with new fathers in relation to reducing alcohol-related harm?

Methods

This scoping review examines the range and nature of research evidence on men’s alcohol consumption in the context of becoming a father. Scoping reviews are suitable when the research questions are broad and studies of different designs are included (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). A six stage framework for scoping reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010) was used to ensure the review was undertaken in a rigorous and transparent manner: 1) Identifying the research question; 2) Identifying relevant studies; 3) Study selection; 4) Charting the data; 5) Collating, summarizing and reporting the results; 6) Seeking views and contributions of stakeholders. The review is reported following PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Protocol and registration

The protocol for this scoping review is registered on the FigShare database (Dimova et al., Citation2020).

Eligibility criteria

The review includes studies that report on new fathers’ experiences of alcohol consumption or the feasibility/effectiveness of an intervention to address alcohol consumption in new fathers. For the purpose of this review, alcohol consumption refers to any drinking behavior, including (but not limited to) moderate drinking, heavy episodic drinking, hazardous drinking and alcohol dependence. We use “new fathers” to refer to those expecting a child or whose youngest child is up to 24 months old. Eligible interventions could take a psychosocial, behavioral or medical approach to address alcohol consumption. Studies that focused on both parents were included only if they reported information on fathers separately. Grey literature, such as newspaper articles and opinion pieces, was excluded. However, unpublished reports were deemed relevant in order to reduce the risk of publication bias in the review (Hopewell et al., Citation2007). Conference proceedings and study protocols were also deemed eligible for inclusion as they provide important information about ongoing studies. Only studies in English were included due to time and financial restraints.

Search process

The following electronic databases were systematically searched: Medline, CINAHL, Web of Science, PsychInfo. Reference lists of included articles were hand searched to identify any relevant studies that may have been omitted by the databases search.

Databases were searched from inception until November 2020. A comprehensive search strategy was developed and adapted for each database, by combining key terms for a) pregnancy, b) fathers and c) alcohol, and Boolean operators. We consulted previous literature to identify search terms, relating to expectant and new fathers (Poh et al., Citation2014; Baldwin & Bick Citation2017; Holopainen & Hakulinen Citation2019). No search limits were applied.

The primary author ran the search, collated all identified articles in Microsoft Excel and removed duplicates. After this, the titles and abstracts of the articles were independently screened by two reviewers (ED, JM). They marked the selection as ‘include’, ‘exclude’ or ‘unclear’ on the basis of the inclusion criteria. After this, the full text of all articles marked as ‘include’ or ‘unclear’ was obtained and screened independently by the two reviewers to ensure articles met the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction and synthesis

A data extraction tool, informed by The Joanna Briggs Institute (2020), was developed for this review in order to create a descriptive summary of the results and address the review aims. We extracted data on: study information (i.e. author, year, country), aim, methods, population, participant recruitment and eligibility criteria, data collection (for qualitative studies), key findings (for qualitative studies), intervention information (for intervention studies, e.g. theory, components, duration), alcohol measures (for intervention studies) and alcohol outcomes (for intervention studies). Data were extracted into Microsoft Excel to produce evidence tables. One table presents key information from studies on new fathers’ experiences of alcohol consumption and another on interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in new fathers. Data extraction was completed by one author (ED) and double checked by another (JM).

The extracted information was brought together in a narrative summary, and organized around the research questions.

Stakeholder involvement

The review findings and their implications were discussed in a stakeholder meeting, attended by representatives from third sector organizations that work with fathers and families, and academics with extensive experience in gender-based interventions and research focusing on fathers.

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

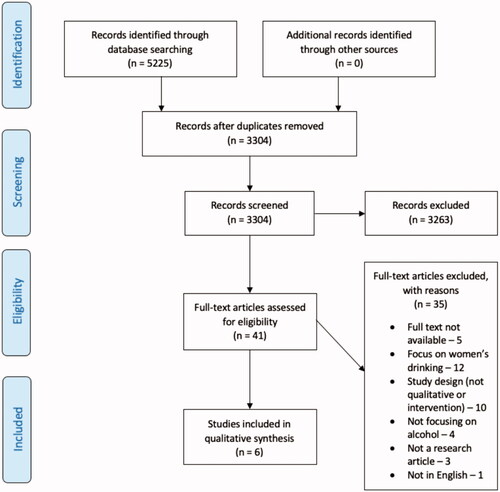

The databases yielded 3,304 unique results. After screening titles and abstracts, the full text of 41 articles was obtained and screened. The review includes five articles, published in peer-reviewed journals, and one protocol. Three of the studies explored fathers’ experiences of alcohol consumption, two reported on interventions and one is a protocol for an intervention to reduce alcohol consumption in new fathers. The study selection process is reported using the PRISMA flowchart (Moher et al., Citation2009; ).

Characteristics of sources of evidence

The extracted information from individual studies, included in the review, is presented in and .

Table 1. Studies on new fathers’ experiences of alcohol consumption.

Table 2. Studies on interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in new fathers.

Study description

Three qualitative studies explored views and experiences of drinking among the male partners of pregnant women (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017; Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015; Van der Wulp et al., Citation2013). They were conducted in Australia (Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015), Canada (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017) and the Netherlands (Van der Wulp et al., Citation2013).

The review includes three studies reporting on interventions to reduce alcohol use among new and expectant fathers (Fletcher et al., Citation2018; Noonan et al., Citation2016; Robinson et al., Citation2018). This comprises one randomized controlled trial (RCT) examining whether a smoking cessation intervention had unintended effects on alcohol consumption among new fathers in the USA (Noonan et al., Citation2016), one developmental study (a text-based intervention informing men about the benefits of reducing risky drinking during the transition to fatherhood in Australia; Robinson et al., Citation2018) and one protocol for an RCT, proposing a text based intervention with expectant fathers in Australia (Fletcher et al., Citation2018).

Study population

The participants in the qualitative studies comprised four expectant or new fathers (Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015), nine expectant fathers (Van der Wulp et al., Citation2013) and eight men who reported being in a committed relationship with the mother of their youngest (or unborn) child (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017). Van der Wulp et al. (Citation2013) failed to provide socio-demographic information, and Crawford-Williams et al. (Citation2015) reported that all men were Caucasian and either from Australia or New Zealand. Benoit and Magnus (Citation2017) provided more detailed information about their study population. Six of the eight men in their study self-identified as Indigenous (First Nations, Metis or Inuit) and their median age was 26 years. Two of the eight fathers reported being employed, four were currently in receipt of income assistance, and one father reported being homeless (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017).

The intervention studies included 51 men (49 current fathers and two expectant fathers) (Robinson et al., Citation2018) and 348 men (Noonan et al., Citation2016). Most of the men (n = 44) in Robinson et al. (Citation2018) were married/in a de facto relationship, were between the ages of 36 and 50 years (n = 38), were employed (n = 50) and had university education (n = 39). Noonan et al.'s (Citation2016) study included 348 men with a mean age of 30 years; half (49%) were White and 46% reported being of more than one race. Two thirds (66%) reported education below secondary level. Perceived financial burden was also measured: 38% of men reported having difficulty paying their bills, 42% indicated having enough money to pay the bills but little spare, 15% had enough money to pay the bills but had to cut back on other things, and only 5% had enough money for special things.

Recruitment

Participants in the qualitative studies were recruited through posters/flyers in venues, attended by expectant and new parents (e.g. health and social services, women’s and children’s hospital, midwife practice, pregnancy courses, antenatal classes) (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017; Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015; Van der Wulp et al., Citation2013). Participants in the quantitative studies were recruited through clinics (Noonan et al., Citation2016) and via social media (Robinson et al., Citation2018). Fletcher et al. (Citation2018) plan to recruit 800 expectant and new fathers through a study-specific website, that men will be made aware of through media outlets, including social media and flyers distributed by health staff.

Eligibility criteria were not reported in two studies (Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015; Van der Wulp et al., Citation2013). Benoit and Magnus (Citation2017) recruited participants who were 19 years of age or older, were affected by substance use either directly or indirectly, had low income or insecure housing, and had a pregnant partner, or had a baby in the last 12 months. Robinson et al.’s (Citation2018) inclusion criteria were: current or expectant Australian fathers who have ever consumed alcohol, and who have access to the Internet. Participants in Noonan et al.'s (Citation2016) study had to meet certain criteria for smoking (as this was a smoking cessation intervention and alcohol was a secondary outcome). Finally, Fletcher et al. (Citation2018) plan to recruit men who have a partner who is more than 16 weeks pregnant or their infant is less than 12 weeks of age, have a mobile phone capable of receiving text messages, and are able to read and understand English.

Data collection (qualitative studies)

Benoit and Magnus (Citation2017) explored personal definitions of problematic substance use during pregnancy and early parenting, participants’ living situation and, experiences with healthcare services while Crawford-Williams et al. (Citation2015) discussed the negative consequences of drinking during pregnancy, sources of information about alcohol use in pregnancy and the availability of reliable health information (Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015). Van der Wulp et al. (Citation2013) asked men about their pregnant partner’s alcohol use, whether they have discussed this with their partner, and their views and experiences of information on alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

Alcohol measures (quantitative studies)

Noonan et al. (Citation2016) measured ‘binge drinking’ in the past 30 days by asking men how many days a week they had an alcoholic beverage, and then asking men who drank one or more days a week, to report the number of drinks they had each day. Those who indicated having five or more drinks a day were considered to be ‘binge’ drinkers. Robinson et al. (Citation2018) used the AUDIT C (which screens for hazardous drinking and alcohol dependence) and also asked fathers to rate the importance and difficulty (using a Likert scale) of following the Australian alcohol guidelines. Fletcher et al. (Citation2018) plan to measure alcohol outcomes using the AUDIT C.

Alcohol outcomes and intervention effectiveness (quantitative studies)

Robinson et al. (Citation2018) describe the development and piloting of 30 text messages to inform men about the benefits of reducing risky drinking during the transition to fatherhood. They asked fathers to rate the text messages for importance and likelihood of seeking further information. Participants attributed higher importance to messages in a child voice compared to those in a second person voice. However, fathers gave similar ratings of likelihood of pursuing information between child voice and second person voice. In sub-group analysis, the authors found that men who consumed alcohol at high-risk levels rated importance of following drinking guidelines as less important but also more difficult to adhere to, compared to those who drank at low-risk levels. The qualitative component of the study found that most fathers responded positively to the text messages and reported that messages that directly connected their behavior with their child’s health and emotional wellbeing had a greater impact than the messages about their own health (Robinson et al., Citation2018). However, some men viewed these messages as manipulative. Finally, the study found that ex-drinkers and risky drinkers indicated a preference for strongly worded alcohol messages (Robinson et al., Citation2018). The men in Noonan et al.'s (Citation2016) study, who received the couples-based intervention, were less likely to report binge drinking at 12 months compared to those in the control arm. In addition, men who quit smoking reported less binge drinking compared to non-quitters. Fletcher et al. (Citation2018) predict that alcohol use (based on the AUDIT C) will be lower among men who receive the SMS4dads intervention, compared to those who receive the comparison SMS4health intervention.

Synthesis of results

Fathers’ experiences of alcohol consumption

This review highlights the scarcity of qualitative research exploring men’s experiences of alcohol consumption in the transition to fatherhood. Only one of the included studies explored fathers’ experiences in depth and it focused on problematic substance use (including drugs).

Motives for reducing drinking

Fathers in two studies reported reducing their alcohol consumption during pregnancy to show support for their partner (Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015; Van der Wulp et al., Citation2013). Some men reduced their drinking because they missed their spouse as a drinking companion (Van der Wulp et al., Citation2013). Becoming a father was also reported as a reason for reducing drinking; fathers’ alcohol (and other substance) use was perceived to be as harmful for the baby as substance use by the mother, but participants acknowledged that fathers were not held to the same degree of responsibility in relation to abstinence as mothers (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017). Men in Benoit and Magnus' (Citation2017) study believed substance use can interfere with parenting in both financial and emotional ways. Respondents perceived themselves as role models for their children and realized that their behavior could break the cycle of socioeconomic disadvantage (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017). Participants in Benoit and Magnus' (Citation2017) study also talked about domestic violence as an example of substance-related harm and the majority of participants said that safety needs to be a prerequisite for the inclusion of fathers in family life.

Knowledge of alcohol and pregnancy

Only one study in this review explored (expectant) fathers’ knowledge of the effects of alcohol use during pregnancy on babies (Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015). Although most participants (women and their partners) acknowledged that alcohol has the potential to cause harm to the unborn baby, the quantity of alcohol needed to cause harm, and the impact of the timing of the exposure were not well known. Many participants believed that alcohol consumption by the mother in the first trimester would cause harm but a small amount of alcohol throughout the pregnancy was not perceived as harmful for the baby (Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015).

Support for decreased drinking

Benoit and Magnus (Citation2017) found that agreement to abstain from alcohol was mostly viewed as the mother’s decision rather than a mutual decision. Some respondents reported their partners gave them an ultimatum to stop drinking or lose their family, although there were examples where the pregnant woman supported the man to quit drinking (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017). Finally, Van der Wulp et al. (Citation2013) found that men reported websites about pregnancy were not suited for expectant fathers as they contain pink colors and pictures of pregnant women. Similarly, fathers in Benoit and Magnus (Citation2017) study reported feeling uncomfortable in parenting groups.

Characteristics of existing interventions to target alcohol consumption in new fathers

Given the limited evidence on interventions to target alcohol consumption in new fathers, this scoping review cannot identify key characteristics of successful interventions. However, we provide the characteristics of included interventions below.

Only one study assessed intervention effectiveness although the intervention itself did not focus on alcohol consumption, as this was a secondary outcome. Noonan et al.'s (Citation2016) intervention was couples-based and included a booklet guide on quitting smoking, free nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) for six weeks, three face-to-face counselling sessions during pregnancy, and three sessions postpartum (one face-to-face and two over the phone). The counselling sessions focused on emotions (e.g. pride, responsibility), health effects of smoking, goal setting, effective communication and support, and review of goals.

Robinson et al.’s (Citation2018) intervention did not assess effectiveness. The intervention included 30 text messages, which were based on Australia’s drinking guidelines, and addressed alcohol-related harms in relation to infant health, the spousal relationship, father-infant relationship and the fathers’ health. The intervention was informed by theory, using motivational interviewing (MI) and the Stages of Change model. The messages were presented either from a child’s voice, as if the child is addressing their father (e.g. ‘Hey dad, do you know how many drinks you can have before it affects your health?’) or from a second person voice (e.g. ‘Do you know how many drinks you can have before it affects your health?’).

In the intervention, proposed by Fletcher et al. (Citation2018), the messages were developed through consultation with parents, academics and practitioners. A father who takes part in the full 77-week intervention will receive 294 messages, 25 of which focus on alcohol, but their content is not reported by Fletcher et al. (Citation2018). The messages are timed according the babies’ expected or actual date of birth, so the issues they address are likely to be relevant for the father. The messages aim to engage with fathers through humor, use of the baby’s voice, and an encouraging, non-judgmental tone.

Strategies to engage with new fathers in relation to reducing alcohol-related harm

The limited number of studies identified by this review suggest that it is feasible to recruit expectant and new fathers through antenatal clinics, hospitals and other venues where fathers may go (e.g. antenatal classes, pregnancy courses). Potentially successful approaches could include the use of posters/flyers, recommendations through gatekeepers (e.g. midwives, nurses), and by directly approaching men after gatekeeper approval is obtained (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017; Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015; Noonan et al., Citation2016; Van der Wulp et al., Citation2013). Social media is another potentially successful avenue for engaging expectant and new fathers (Fletcher et al., Citation2018; Robinson et al., Citation2018). However, detailed information about the recruitment approach could be extracted in relation to only one study (Noonan et al., Citation2016). Noonan et al. (Citation2016) present secondary analysis from a smoking cessation trial, where the researchers approached 555 men, of which 411 agreed to participate (Pollak et al., Citation2010). Extracted information from the larger trial study (Pollak et al., Citation2010) suggests that contacting partners of pregnant women directly (after agreement from the pregnant woman) can be a successful approach to engaging fathers.

Discussion

This scoping review highlights the scarcity of research, exploring fathers’ experiences of alcohol use and effectiveness of interventions to support new fathers to reduce alcohol consumption. This is in line with the findings of a previous scoping review, which points to the invisibility of fathers in studies of psychosocial interventions for substance-abusing parents (Heimdahl, Citation2016).

Qualitative research exploring expectant and new fathers’ experiences of alcohol use during and after pregnancy is limited. Previous research has focused primarily on mothers’ experiences of alcohol consumption and how fathers can support women to stop drinking (Balachova et al., Citation2007; Edvardsson et al., Citation2011; Hammer, Citation2019). Two studies in this review suggest that men may reduce alcohol consumption in order to support their pregnant partner (Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015; Van der Wulp et al., Citation2013). Consistent with previous research (Wolf & Chavez, Citation2015), one study in this review found that men believed that a father should be a role model for their children (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017). In addition, fathers believed that their substance use can be as harmful to the baby as that of the mother (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017). However, participants had low incomes and were affected by any substance use (not necessarily alcohol), so these findings may not be transferable to fathers in the general population. This also highlights the importance of including diverse samples of fathers in research studies. Factors such as young age, being a first-time father and planned pregnancy may be related to men’s intentions to adopt healthy behaviors (Bodin et al., Citation2017; Shawe et al., Citation2019).

More research is also needed to explore fathers’ perceptions of alcohol consumption as well as the social context of their drinking, at different time points following the birth of the baby. According to Miller (Citation2011) while equality and sharing care for the baby are anticipated in the postnatal period, return to paid work disrupts men’s intentions and results in fathers trying to incorporate caring practices into evenings and weekends. Managing work pressures and fathering responsibilities may also compromise men’s intention to adopt and maintain healthy behaviors (Flemming et al., Citation2015; Gordon et al., Citation2013; Kwon et al., Citation2015).

This review found that some fathers perceive antenatal websites to be tailored specifically for women (Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015; Van der Wulp et al., Citation2013) and feel uncomfortable in parenting classes (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017). This resonates with previous qualitative longitudinal studies that explored the experiences of fathers in the UK and Australia during the antenatal and postnatal periods (up to two years after birth, Miller & Nash, Citation2017). Men in the UK attended couple-based antenatal classes and reported feeling uncertain and out of place as they felt the classes were tailored for the mothers (Miller & Nash, Citation2017). Australian men, who attended all-male classes felt more secure, especially when the midwife was male. However, some of the participants believed that outdated male stereotypes (e.g. men’s drinking, watching/doing sports, etc.) were drawn upon both by other participants and the instructor (Miller & Nash, Citation2017). A recent qualitative study in Australia also found that beliefs about gender roles and perceptions that interventions are mother-focused can act as barriers to fathers participating in parenting interventions (Sicouri et al., Citation2018). More research is needed to inform the content and form of presentation for information targeting new fathers.

There is limited intervention research to address alcohol use during the transition to fatherhood. This scoping review identified only one intervention that assessed effectiveness. This was a smoking cessation intervention, which had an unintended impact on alcohol consumption and led to a significant decrease in ‘binge drinking’ among fathers (Noonan et al., Citation2016). The study suggests that involving both members of the couple in an intervention and emphasizing communication skills are important for intervention effectiveness (Noonan et al., Citation2016). This is not surprising given the strong support in the literature for Behavioral Couples Therapy to reduce drinking and increase relationship functioning (McCrady et al., Citation2019). The utility of family-based interventions has also been demonstrated in the field of smoking (Chan et al., Citation2017).

This scoping review also suggests that text message interventions may offer a promising avenue for engaging men. The utility of text message interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm among men has previously been demonstrated (Crombie et al., Citation2017, Citation2018) and there is clear evidence that text message interventions can promote healthy behaviors among pregnant women (Balci & Kadioglu, Citation2018). The interventions by Robinson et al. (Citation2018) and Fletcher et al. (Citation2018) include text messages in a child’s voice, which aims to create a virtual conversation between the father and the baby, thus promoting father involvement. The use of virtual conversation in the form of a narrative has strong potential to increase engagement and reduce resistance to change (Miller-Day & Hecht, Citation2013; Murphy et al., Citation2013). For example, Crombie et al. (Citation2018) found high engagement in an alcohol-reduction text message intervention among men, living in disadvantaged areas in Scotland. The text messages were embedded in a humorous narrative that followed the journey of a man who gradually reduces drinking (Crombie et al., Citation2018). The character encounters difficulties, and models key behavior change techniques, such as goal setting and action planning (Crombie et al., Citation2018).

This scoping review suggests it is feasible to recruit expectant and new fathers through antenatal clinics, hospitals and other venues where fathers may go (e.g. antenatal classes) (Benoit & Magnus, Citation2017; Crawford-Williams et al., Citation2015; Noonan et al., Citation2016; Van der Wulp et al., Citation2013). However, recruitment through antenatal classes may result in the exclusion of specific groups of men, such as separated fathers. More research is needed to develop tailored approaches to recruit diverse groups of fathers. Social media can also be a successful way to engage expectant and new fathers (Fletcher et al., Citation2018; Robinson et al., Citation2018). Vibrant images and concise captions via Facebook may be particularly effective in engaging men in health behavior research (Ryan et al., Citation2019). Ryan et al. (Citation2019) also found that asking women to invite men increased male participation (Ryan et al., Citation2019). This resonates with the findings from Noonan et al. (Citation2016) and Pollak et al. (Citation2010) who found that contacting partners of pregnant women directly (after agreement from the pregnant woman) can be a successful approach to engaging fathers. However, this needs to be done carefully because viewing mothers as ‘gatekeepers’ may also act as a barrier to fathers’ engagement with parenting interventions (Sicouri et al., Citation2018). Future studies need to provide information on non-responders, in order to understand how successful specific recruitment strategies are.

Implications for policy and practice

The findings of this review have implications for families, health professionals, and policy makers. Parenting interventions offer a promising avenue for promotion of healthy behaviors. However, the majority of global parenting interventions marginalize fathers (Panter-Brick et al., Citation2014) and fathers often feel excluded and inadequate when engaging with health visiting services (Menzies, Citation2019). An important step towards creating father-friendly services is to ensure antenatal services signal fathers’ involvement. A recent series of interventions found that inclusion of environmental cues, such as men’s magazines and pictures of fathers, increased intentions and confidence in men to be involved as fathers and to engage in health behaviors (Albuja et al., Citation2019). In addition, Menzies (Citation2019) recommends that health professionals need to link the birth transition to fatherhood, rather than simply preparing men to support their partners. Practitioner interactions that value fathers and support them in developing parenting skills can facilitate fathers’ engagement with early childhood programs (Anderson et al., Citation2015). Although it is crucial for parenting interventions to involve and be promoted to fathers (Panter-Brick et al., Citation2014; Sicouri et al., Citation2018), they need to be carefully designed to be respectful of cultural values as cultural and ethnic factors may influence paternal engagement (Hofferth, Citation2003). Health care professionals need to be equipped to show greater sensitivity to the subtleties of cultural norms and be careful to not make incorrect assumptions on the basis of perceived cultural values (Crawshaw et al., Citation2010).

Despite socio-political changes affecting paternal parenting culture, fathers may still feel unsupported when it comes to antenatal support (Kowlessar et al., Citation2015) and health visitors may face organizational and cultural barriers to father-inclusive practice (Humphries & Nolan, Citation2015). To further promote change, nationwide policies need to challenge gender biases, normalize parenting practices and promote training and education for health professionals. Documents that refer to parents may implicitly perpetuate fathers’ role as ‘bystanders’. This is acknowledged in Scotland’s National Parenting (2012) strategy, which says that ‘when discussing parenting we still tend to think of the mother rather than the father, leaving fathers feeling of secondary importance or worse, excluded’ (Scottish Government, Citation2012, p. 35).

Limitations of the current review

A number of limitations of the current scoping review should be acknowledged. In an effort to identify studies that focus on expectant and new fathers, we included key terms related to pregnancy (e.g. antenatal, postnatal) so the search may have excluded studies focusing on fathers of young children. The review included only studies in English and studies in other languages may offer additional evidence. Although the review did not exclude grey literature, we did not specifically search for grey literature so unpublished reports may have been omitted by the search.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights the almost complete absence of new fathers’ voices in relation to their experiences of alcohol use and of research on the effectiveness of interventions to support new fathers to reduce alcohol consumption. The findings have implications for researchers and health practitioners, as insufficient understanding of new fathers’ experiences of alcohol use may result in missed opportunities to address hazardous and harmful drinking among men during an important period of transition into fatherhood.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Rachel O’Donnell (University of Stirling), Dr Anna Tarrant (University of Lincoln), Mark Hunter (Fast Forward), Ryan Warren (Home-Start), and John Holleran (Scottish Families Affected by Alcohol and Drugs) who formed the study stakeholder group and advised on the study findings and their implications.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albuja, A. F., Sanchez, D. T., Lee, S. J., Lee, J. Y., & Yadava, S. (2019). The effect of paternal cues in prenatal care settings on men’s involvement intentions. PLoS One, 14(5), e0216454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216454

- Anderson, S., Aller, T. B., Piercy, K. W., & Roggman, L. A. (2015). Helping us find our own selves’: Exploring father-role construction and early childhood programme engagement. Early Child Development and Care, 185(3), 360–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.924112

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bailey, J. A., Hill, K. G., Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., & Abbott, R. D. (2008). Men’s and women’s patterns of substance use around pregnancy. Birth, 35(1), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00211.x

- Balachova, T. N., Bonner, B. L., Isurina, G. L., & Tsvetkova, L. A. (2007). Use of focus groups in developing FAS/FASD prevention in Russia. Substance Use & Misuse, 42(5), 881–894. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080701202601

- Balci, A. S., & Kadioglu, H. (2018). Text messages based interventions for pregnant women’s health: Systematic review. Clinical and Experimental Health Sciences, 9(1), 85–90.

- Baldwin, S., & Bick, D. (2017). First-time fathers' needs and experiences of transition to fatherhood in relation to their mental health and wellbeing: A qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 15(3), 647–656. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003031

- Benoit, C., & Magnus, S. (2017). Depends on the father: Defining problematic substance use during pregnancy and early parenthood. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 42(4), 379–402.

- Bodin, M., Kall, L., Tyden, T., Stern, J., Drevin, J., & Larsson, M. (2017). Exploring men’s pregnancy planning behaviour and fertility knowledge: A survey among fathers in Sweden. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences, 122(2), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009734.2017.1316531

- Chan, S. S. C., Cheung, Y. T. D., Fong, D. Y. T., Emmons, K., Leung, A. Y. M., Leung, D. Y. P., & Lam, T. H. (2017). Family-based smoking cessation intervention for smoking fathers and non-smoking mothers with a child: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Pediatrics, 182, 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.11.021

- Condon, J. T., Boyce, P., & Corkindale, C. J. (2004). The first-time fathers study: A prospective study of the mental health and wellbeing of men during the transition to parenthood. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38(1–2), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/000486740403800102

- Crawford-Williams, F., Steen, M., Esterman, A., Fielder, A., & Mikocka-Walus, A. (2015). “My midwife said that having a glass of red wine was actually better for the baby”: A focus group study of women and their partner's knowledge and experiences relating to alcohol consumption in pregnancy”: BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0506-3

- Crawshaw, M., Chattoo, S., & Atkin, K. (2010). Experiences of cancer-related fertility concerns among people of South Asian and White origin: Summary for professionals. University of York and Cancer research UK.

- Crombie, I. K., Cunningham, K. B., Irvine, L., Williams, B., Sniehotta, F. F., Norrie, J., Melson, A., Jones, C., Briggs, A., Rice, P. M., Achison, M., McKenzie, A., Dimova, E., & Slane, P. W. (2017). Modifying alcohol consumption to reduce obesity (MACRO): Development and feasibility trial of a complex community-based intervention for men. Health Technology Assessment, 21(19), 1–150. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta21190

- Crombie, I. K., Irvine, L., Williams, B., Sniehotta, F. F., Petrie, D., Jones, C., Norrie, J., Evans, J. M. M., Emslie, C., Rice, P. M., Slane, P. W., Humphris, G., Ricketts, I. W., Melson, A. J., Donnan, P. T., Hapca, S. M., McKenzie, A., & Achison, M. (2018). Texting to reduce alcohol misuse (TRAM): Main findings from a randomized controlled trial of a text message intervention to reduce binge drinking among disadvantaged men. Addiction, 113(9), 1609–1618. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14229

- Desrosiers, A., Thompson, A., Divney, A., Magriples, U., & Kershaw, T. (2016). Romantic partner influences on prenatal and postnatal substance use in young couples. Journal of Public Health, 38(2), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdv039

- Dimova, E., McGarry, J., McAloney-Kocaman, K., & Emslie, C. (2020). Exploring men’s alcohol consumption in the context of becoming a father: A scoping review. Preprint. Retrieved January 8, 2021, from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13055711.v1

- Edvardsson, K., Ivarsson, A., Eurenius, E., Garvare, R., Nystrom, M. E., Small, R., & Mogren, I. (2011). Giving offspring a healthy start: parents’ experiences of health promotion and lifestyle change during pregnancy and early parenthood. BMC Public Health, 11, 936. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-936

- Emslie, C., Hunt, K., & Lyons, A. (2013). The role of alcohol in forging and maintaining friendships amongst Scottish men in midlife. Health Psychology, 32(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029874

- Everett, K. D., Bullock, L., Longo, D. R., Gage, J., & Madsen, R. (2007). Men’s tobacco and alcohol use during and after pregnancy. American Journal of Men’s Health, 1(4), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988307299477

- Flemming, K., Graham, H., McCaughan, D., Angus, K., & Bauld, L. (2015). The barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation experienced by women’s partners during pregnancy and the post-partum period: A systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Public Health, 15, 849. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2163-x

- Fletcher, R., May, C., Attia, J., Garfield, C. F., & Skinner, G. (2018). Text-based program addressing the mental health of soon-to-be and new fathers (SMS4dads): Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 7(2), e37. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.8368

- Garfield, C. F., Isacco, A., & Bartlo, W. D. (2010). Men’s health and fatherhood in the urban Midwestern United States. International Journal of Men’s Health, 9(3), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.0903.161

- Gordon, D. M., Hawes, S. W., Reid, A. E., Callands, T. A., Magriples, U., Divney, A., Niccolai, L. M., & Kershaw, T. (2013). The many faces of manhood: Examining masculine norms and health behaviours of young fathers across race. American Journal of Men’s Health, 7(5), 394–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988313476540

- Hammer, R. (2019). I can tell when you’re staring at my glass …: Self- or co-surveillance? Couples’ management of risks related to alcohol use during pregnancy. Health, Risk & Society, 21(7–8), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2019.1682126

- Heimdahl, K., & Karlsson, P. (2016). Psychosocial interventions for substance-abusing parents and their young children: A scoping review. Addiction Research & Theory, 24(3), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2015.1118064

- Hofferth, S. L. (2003). Race/ethnic differences in father Involvement in two-parent families: Culture, context, or economy. Journal of Family Issues, 24(2), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X02250087

- Högberg, H., Skagerström, J., Spak, F., Nilsen, P., & Larsson, M. (2016). Alcohol consumption among partners of pregnant women in Sweden: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 694. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3338-9

- Holopainen, A., & Hakulinen, T. (2019). New parents’ experiences of postpartum depression: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 17(9), 1731–1769. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003909

- Hopewell, S., McDonald, S., Clarke, M., & Egger, M. (2007). Grey literature in metaanalyses of randomised trials of health care interventions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), MR000010. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000010.pub3

- Humphries, H., & Nolan, M. (2015). Evaluation of a brief intervention to assist health visitors and community practitioners to engage with fathers as part of the healthy child initiative. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 16(4), 367–376. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423615000031

- Kowlessar, O., Fox, J., & Wittkowski, A. (2015). First-time fathers’ experiences of parenting during the first year. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 33(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2014.971404

- Kwon, J. Y., Oliffe, J. L., Bottorff, J. L., & Kelly, M. T. (2015). Masculinity and fatherhood: New fathers’ perceptions of their female partners’ efforts to assist them to reduce or quit smoking. American Journal of Men’s Health, 9(4), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988314545627

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- McBride, N., & Johnson, S. (2016). Fathers’ role in alcohol-exposed pregnancies: Systematic review of human studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(2), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.009

- McCrady, B. S., Tonigan, J. S., Ladd, B. O., Hallgren, K. A., Pearson, M. R., Owens, M. D., & Epstein, E. E. (2019). Alcohol behavioural couple therapy: In-session behaviour, active ingredients and mechanisms of behaviour change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 99, 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.01.018

- Menzies, J. (2019). Fathers’ experiences of the health visiting service: A qualitative study. Journal of Health Visiting, 7(10), 490–497. https://doi.org/10.12968/johv.2019.7.10.490

- Miller-Day, M., & Hecht, M. L. (2013). Narrative means to preventative ends: A narrative engagement framework for designing prevention interventions. Health Communication, 28(7), 657–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2012.762861

- Miller, T. (2011). Falling back into gender? Men’s narratives and practices around first-time fatherhood. Sociology, 45(6), 1094–1109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511419180

- Miller, T., & Nash, M. (2017). I just think something like the “Bubs and Pubs” class is what men should be having’: Paternal subjectivities and preparing for first-time fatherhood in Australia and the United Kingdom. Journal of Sociology, 53(3), 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783316667638

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Murphy, S. T., Frank, L. B., Chatterjee, J. S., & Baezconde-Garbanati, L. (2013). Narrative versus nonnarrative: The role of identification, transportation and emotion in reducing health disparities. Journal of Communication, 63(1), 116–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12007

- Noonan, D., Lyna, P., Fish, L. J., Bilheimer, A. K., Gordon, K. C., Roberson, P., Gonzalez, A., & Pollak, K. I. (2016). Unintended effects of a smoking cessation intervention on Latino fathers’ binge drinking in early postpartum. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50(4), 622–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9781-0

- Olsson, A., Robertson, E., Bjorklund, A., & Nissen, E. (2010). Fatherhood in focus, sexual activity can wait: New fathers’ experience about sexual life after childbirth. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 24(4), 716–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00768.x

- Panter-Brick, C., Burgess, A., Eggerman, M., McAllister, F., Pruett, K., & Leckman, J. F. (2014). Practitioner review: Engaging fathers-recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 55(11), 1187–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12280

- Poh, H. L., Koh, S. S. L., & He, H. G. (2014). An integrative review of fathers’ experiences during pregnancy and childbirth. International Nursing Review, 61(4), 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12137

- Pollak, K. I., Denman, S., Gordon, K. C., Lyna, P., Rocha, P., Brouwer, R., Fish, L., & Baucom, D. H. (2010). Is pregnancy a teachable moment for smoking cessation among US Latino expectant fathers? A pilot study. Ethnicity & Health, 15(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557850903398293

- Robertson, S. (2007). Understanding men and health:Masculinities, identity and wellbeing. Open University Press.

- Robinson, M., Wilkinson, R. B., Fletcher, R., Bruno, R., Baker, A. L., Maher, L., Wroe, J., & Dunlop, A. J. (2018). Alcohol text messages: A developmental study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(5), 1125–1139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9835-y

- Ryan, J., Lopian, L., Le, B., Edney, S., Van Kessel, G., Plotnikoff, R., Vandelanotte, C., Olds, T., & Maher, C. (2019). It’s not raining men: A mixed-methods study investigating methods of improving male recruitment to health behaviour research. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 814. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7087-4

- Scottish Government. (2012). National parenting strategy. Scottish Government.

- Shawe, J., Patel, D., Joy, M., Howden, B., Barrett, G., & Stephenson, J. (2019). Preparation for fatherhood: A survey of men’s preconception health knowledge and behaviour in England. PLOS One, 14(3), e0213897. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213897

- Sicouri, G., Tully, L., Collins, D., Burn, M., Sargeant, K., Frick, P., Anderson, V., Hawes, D., Kimonis, E., Moul, C., Lenroot, R., & Dadds, M. (2018). Toward father-friendly parenting interventions: A qualitative study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 39(2), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1307

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Van der Wulp, N. Y., Hoving, C., & Vries, H. (2013). A qualitative investigation of alcohol use advice during pregnancy: Experiences of Dutch midwives, pregnant women and their partners. Midwifery, 29(11), e89–e98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.11.014

- Williams, R. A. (2007). Masculinities, fathering and health: The experiences of African Caribbean and white working class fathers. Social Science & Medicine, 64(2), 338–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.019

- Wolf, J. P., & Chavez, R. (2015). “Just make sure you can get up and parent the next day”: Understanding the contexts, risks, and rewards of alcohol consumption for parents”. Families in Society, 96(3), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.2015.96.28

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2019). Status report on alcohol consumption, harm and policy responses in 30 European countries. WHO.