Abstract

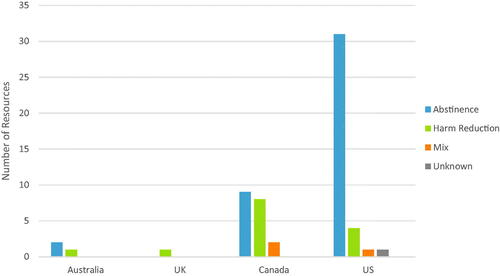

Cannabis was recently legalized for adult use in Canada and many American states. In this context, there is a pressing need for educational resources – aimed at youth and their parents/caregivers – to reduce potential harm. However, little is known about the current state of such resources. This paper presents findings of an environmental scan, mapping and critically analyzing the present landscape of cannabis resources for parents/caregivers. We systematically searched the grey literature identifying English-language resources. Search terms included: youth, young people, child, adolescen*, teen*, train*, tool*, talk, engage*, educat*, involve*, family, parent, adult, caregiver, cannabis, marijuana, pot, weed, prevent*, and harm. Overall, 60 resources met the inclusion criteria. Most were developed in the United States (n = 37) and Canada (n = 19), with three from Australia and one from the United Kingdom. Of these, 42 (70%) were categorized as abstinence-based, 14 (23%) harm-reduction oriented, and 4 (7%) had an unclear approach. Few (10/59) consulted youth in their development and none explicitly included parent/caregiver input. Results can inform the development of new, more appropriate and accessible family-oriented resources – priority in a legalized context where cannabis conversations are shifting away from stigma and abstinence, towards pragmatic approaches with harm reduction goals.

Introduction

With the recent legalization of cannabis in Canada and many of the American states, the need for education targeted to youth and their adult caregivers to reduce potential harms is a public health priority. Indeed, while rates of cannabis use among youth have declined over the last several years, they remain high when compared to other age groups. In Canada, recent results of the Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drug Use Survey show that past-year prevalence of cannabis use in 2018–19 was 23.7% for students in grades 7–9 and 29% for those in grades 10–12 and did not increase significantly post-legalization (Health Canada, Citation2019). In the United States, results from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) show that past-year prevalence of cannabis use for youth 18 years and younger has increased slightly within the last decade, with approximately one in three adolescents using cannabis by the 12th grade, while the US-based Monitoring the Future (MTF) survey conducted in 2017 shows the annual prevalence of 11%, 28%, and 36% in grades 8, 10, and 12, respectively (Johnston et al., Citation2019; Kann et al., Citation2018). The 2017 Australian-based Australian Secondary Students’ Alcohol and Drug Survey (ASSAD) shows that past-year prevalence for youth aged 12–17 was 14%, considerably lower than in North America (Guerin & White, Citation2018).

Harm reduction approaches to youth cannabis use

Calls to improve youth drug education in the context of cannabis legalization recommend a harm reduction approach tailored to the needs of adolescent populations (Adinoff & Cooper, Citation2019; Hathaway, Citation2019; Watson et al., Citation2019; Watson & Erickson, Citation2019). Harm reduction is an orientation based on health equity and human rights for people who use drugs, in recognition that preventing substance use harms need not be an ‘all or nothing’ approach, but one that considers how harms can be mitigated, based on the needs of the individual and their context. At the level of policy, Adinoff and Cooper (Citation2019) refer to this orientation as ‘the balance between the extremes of cannabis prohibition and unregulated legalization, and how to assure that the optimal equilibrium is achieved’ (p. 708). Harm reduction involves a range of strengths-based and health-promoting policies and practices, which seek to address the adverse health, social and economic factors that contribute to substance use harms. In addition, it is based on the understanding that many of the harms of substance use are socially determined and unequally distributed, requiring solutions grounded in social justice. Moreover, a harm reduction approach prioritizes the expertise of people who use substances in defining what is best for them and their communities within the context of interventions and policies.

In youth settings, harm reduction provides an approach to substance use education that extends beyond an emphasis on abstinence and has the potential to overcome shortfalls of existing programs, such as the widely critiqued North American school-based program, Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) (Bruno & Csiernik, Citation2020). Bok and Morales (Citation2000) suggest that in social contexts where drug use is reinforced by peers, and youth identify positive effects of drug use, abstinence and prevention approaches are ‘a form of denial, by adults, about the actual behaviors of teenagers and young adults’ (p. 94). Yet, harm reduction has not been widely studied or adopted for youth populations (Midford, Citation2010), though school-based programs have started to emerge in response to criticisms of existing prevention programs and research indicating that harm reduction aligns with youths’ substance use education and support needs (Jenkins et al., Citation2017; Slemon et al., Citation2019). Examples of early school-based harm reduction approaches to substance use include SHAHRP in the UK (McKay et al., Citation2014), DEVS in Australia (Midford et al., Citation2014), JustSayKnow in the USA (Meredith et al., Citation2021), BeYourself in Spain (Villanueva et al., Citation2021), MOTI-4 in the Netherlands (Dupont et al., Citation2016) and SCIDUA in Canada (Poulin & Nicholson, Citation2005). More recently, there have been harm reduction-focused interventions specific to cannabis developed for Canadian post-secondary contexts. These interventions aim to increase knowledge and minimize associated harms, rather than frequency or amount of use (Mader et al., Citation2020).

Beyond programs delivered in educational settings, there is limited evidence on interventions to address the potential harms of youth cannabis use (Bogt et al., Citation2014). Walton et al. (Citation2014) suggest that family-based interventions may hold promise for reducing self-reported cannabis use amongst teens; however, interventions aimed at parents and youth have not been extensively studied. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of family-based interventions, Vermeulen-Smit et al. (Citation2015) suggest that ‘family interventions targeting parent–child dyads are likely to be effective in preventing and reducing adolescent marijuana use in general populations,’ (p. 218) but cite the need for additional studies on poly-substance use and use within ‘high-risk’ populations. Indeed, while there is a high prevalence of cannabis use among youth generally, harmful cannabis use is notably higher among youth who experience stress and trauma in their family and school environments (Butters, Citation2005; Hyman & Sinha, Citation2009), as well as among youth who are marginalized (Fusco & Newhill, Citation2021; Nelson, Citation2021). Indeed, the presence of vulnerabilities within families, including parental substance use, mental illness, and childhood adversity, are associated with the earlier onset of use by youth and more frequent use that leads to dependence (Nelson et al., Citation2015; Silins et al., Citation2014). Cannabis education designed to support marginalized and vulnerable families has not been developed, despite the pressing need.

Given the shifting cannabis policy landscape in much of North America and the central role that adult caregivers play in adolescent substance use practices, an environmental scan was conducted to map and critically analyze current cannabis resources available online for parents/caregivers and their adolescent children. This environmental scan provides insights on publicly available cannabis-related educational materials and can be used to inform the development of appropriate and accessible family-oriented resources, inclusive of the needs of the families who may benefit the most.

Methods

Environmental scanning is public health needs assessment tool that facilitates rapid and comprehensive mapping of resources and identification of gaps (Choo, Citation2001; Rowel et al., Citation2005). Our environmental scan is informed by what Choo (Citation2001) refers to as ‘searching’, the most systematic and robust scanning approach, involving purposeful attempts to seek out information and an openness to unexpected findings that suggest further information needs. Rowel et al. (Citation2005) describe environmental scans as suited to documenting the contextual landscape that contributes to health resource access and to inform the creation of health materials tailored to the needs of communities. Further, this rigorous approach contributes high-quality findings while also providing the flexibility to capture and represent materials beyond the peer-reviewed literature, where much of the cannabis prevention resources originate.

This environmental scan was conducted to achieve two objectives: 1) to map the scope of current cannabis resources aimed at parents/caregivers, and 2) to identify gaps in these resources as they relate to youth and families who may be at higher risk of cannabis use harms.

Data sources and search strategy

Grey literature search strategy

Our search process involved a comprehensive and systematic search of the grey literature to identify existing cannabis resources targeted at parents. This search was conducted using the terms: youth, young people, child, adolescen*, teen*, train*, tool*, talk, engage*, educat*, involve*, family, parent, adult, caregiver, cannabis, marijuana, pot, weed, prevent*, and harm. These terms were entered into Google using various combinations until content saturation was reached. In accordance with the approach developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Citation2012), the first 20 links generated were screened for relevance. When a website relevant to cannabis resources targeted at parents/caregivers were identified, the next 10 links were reviewed until no additional links of relevance were identified. This search strategy was designed to mimic the process parents/caregivers (i.e. lay public) may use to find helpful resources for themselves.

Resource selection

Between July and August 2018 our comprehensive search was conducted and then updated in August 2019. Searches were limited to materials available in English. Titles were screened by three members of the research team to identify relevant literature or online materials. Inclusion criteria for the environmental scan were broad: online resources developed by cannabis stakeholder groups (e.g. government, non-profit agencies, research organizations, industry) applicable to parents/caregivers of adolescents. Included resources could take multiple formats, for example, videos, websites, or downloadable PDFs. Retrieved materials that did not aim to equip parents/caregivers to discuss cannabis use with youth were excluded, including those that addressed substance use more generally and were not cannabis-specific. A total of 916 web-link titles were screened, 107 resources were retrieved (excluding duplicates). Overall, 60 resources met inclusion criteria and were retained for analysis.

Data extraction

A data extraction tool was developed and three members of our research team reviewed the identified resources to extract key characteristics. Reviewers independently and systematically assessed retrieved materials, with differences in assessment resolved through team discussion. For each resource, the reviewers extracted or computed the following information, where available: the name of the resource and sponsoring organization and/or funder; the year published; URL; country and city of origin; underlying philosophy (i.e. abstinence-based, harm reduction oriented); format; Flesch Kinkaid Reading Ease score (calculated by entering resource URL into an online tool created by WebFX [https://www.webfx.com/tools/read-able/] to determine the reading level required to understand the respective materials); and youth and parental involvement in resource development (see ). Additionally, word frequency counts were calculated for key terms to further characterize the content of identified materials.

Data synthesis and analysis

Microsoft Excel was used to facilitate the analysis of extracted materials and deductive coding of resource content. This process supported our interrogation of different philosophical orientations to substance use education and prevention, implicit/explicit assumptions about family composition and parent-child interactions, research evidence-base, and attention to barriers experienced by marginalized groups (e.g. who is represented in accompanying graphics, how his family life defined, references to the social determinants of health).

In addition, critical content analysis techniques were used to synthesize and inductively identify prominent themes to construct the messages told through the various documents (Stemler, Citation2001). Identified resources were uploaded to NVivo 12, a qualitative data management tool, to aid in the organization of the thematic exploration of document text and accompanying images. This process drew on what Stemler (Citation2001) describes as emergent coding in content analysis, where data are independently reviewed by members of the research team, each of whom identifies codes to capture the themes reflected in the data. These codes are then revised to reach consensus and then applied to the data to organize thematic content and facilitate broader interpretations.

Results

Descriptive summary of included resources

A total of 60 resources were characterized and thematically analyzed. All resources identified came from one of four countries; the majority of resources originated from the United States (US) (n = 37), followed by Canada (n = 19), Australia (n = 3) and the United Kingdom (UK) (n = 1).

Resources were reviewed and categorized by philosophical orientation as abstinence-based, harm reduction oriented, or unknown. Resources were coded as abstinence-based when characterized by fear-based and zero tolerance messaging (e.g. ‘cannabis is inherently harmful substance…Ontario’s doctors advocate that those under 25 years of age abstain from recreational cannabis’). Resources identified as harm reduction oriented often included references to a ‘spectrum of use’ and emphasized ‘safer use’. In situations where the messaging or tone was mixed or unclear, the resource was identified as having an ‘unknown’ philosophical orientation. The vast majority of online resources were categorized as abstinence-based. Specifically, of the 60 resources identified, 42 (70%) were abstinence-based, 14 (23%) were harm-reduction oriented, and 4 (7%) had an unclear or unknown orientation to substance use. The geographic distribution of these orientations to substance use provides further insights. For example, of the 37 American resources identified, 83.8% were abstinence-based (n = 31) while far fewer included harm reduction messaging 10.8% (n = 4). Within the 19 Canadian resources, there was a more even distribution between substance use orientations, with 47.4% being abstinence-based (n = 9), and 42.1% adopting a harm reduction approach (n = 8). Of the three Australian resources, two were abstinence-based and one was harm reduction oriented and the one resource identified from the UK was informed by harm reduction principles (See ).

The majority of online resources were published in 2018 (n = 26, 43% of total resources), while 17% (n = 10) of the resources did not have a publication date available. The identified resources originated from various sources, including health departments (n = 18, 30%), non-profit organizations or advocacy groups (n = 13, 22%), research institutes (n = 7, 12%), addiction treatment centres (n = 5, 8%), cannabis industry groups (n = 2, 3%) and multisectoral coalitions that included school boards and various levels of government (n = 15, 25%).

In addition to analyzing the origins of the resources, Flesch Kincaid Reading Ease scores were calculated to assess the reading level of the included materials. Scores can range from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating a higher level of literacy required. Of the resources identified, there was a median reading ease score of 60.75, indicating that most of the material requires a minimum of a grade 10–12 reading level for easy comprehension. In terms of resource length, there was substantial diversity, with text-based resources spanning from 1 to 65 pages (95 pages including references). Of the 60 resources, 10 involved youth in resource development to varying degrees, and none of the resources definitively identified the inclusion of parents in their development.

Qualitative content analysis

While deductive coding supported a descriptive characterization of included resources, inductive analysis facilitated the identification of several data-driven themes that provide further insights into resource messaging and orientation to substance use. These themes include: 1) framing the effects of cannabis, 2) general versus nuanced conceptualizations of cannabis use, 3) language choices, and 4) assumptions regarding family structures and expected parental behaviour.

Framing the effects of cannabis use: differences by philosophical orientation

Analysis of the content of the abstinence-based resources revealed that beyond a message that youth should not consume cannabis, there was a strong focus on the negative consequences and harmful effects of use. For example, one resource produced by an American nonprofit organization emphasized the negative effects of cannabis and framed all degrees of cannabis use as risky:

During the adolescent years, your teen is especially susceptible to the negative effects of any and all drug use. Marijuana use directly affects the parts of the brain responsible for memory, learning and attention. Scientific evidence shows that marijuana use during the teen years can permanently lower a person’s IQ and interfere with other aspects of functioning and well-being (Resource #15)

While some of the resources characterized as abstinence-based acknowledged the various reasons why youth may choose to use or experiment with cannabis (e.g. to fit into a social group, curiosity, sensation seeking), there was rarely mention of the potential benefits of cannabis use. Where they were referenced, these benefits (e.g. reducing anxiety, lessening pain, and facilitating sleep) were often framed as ‘perceived’ or lacking credibility, while the negative consequences were positioned as far outweighing any benefits. A lack of maturity or brain development was often cited as contributing to young peoples’ (poor) decision-making about cannabis use. An example of this is illustrated by the content of a resource developed by an American health department:

The adolescent brain craves pleasure but isn’t mature enough yet to weigh risks. This may result in youth using marijuana because they crave the good feelings, or the “high,” without having the ability to think about potential long-term consequences as an adult would. (Resource #12)

In contrast, analysis of harm reduction-oriented materials revealed more nuanced, less absolutist messaging, with negative consequences or potential harms described, but often with a caveat that cannabis use ‘may or may not lead to problems’ (Resource #7). This subtle, but clear difference in language further distinguished the materials using an abstinence-based orientation from those taking a harm reduction approach. For example, the abstinence-based materials framed cannabis use as leading to ‘consequences’ that are exclusively negative or harmful, whereas the harm reduction-based resources tended to describe ‘impacts’:

When approaching cannabis education with youth, parents and educators must often navigate the challenges of speaking about both the evidence-based risks and benefits of cannabis use, including what to say and how to say it. In order to minimize harmful behaviours and help youth make informed decisions regarding the use of cannabis, the inclusion of evidence-based conversations should prioritize young people's agency and decision-making capabilities, as well as assist youth in understanding the impacts of cannabis use. (Resource #33)

The language used in this harm reduction-oriented resource avoids assumptions about the effects of cannabis use, instead of using words that are more inclusive. Further, the potential harms of youth cannabis use are not ignored, nor is youth cannabis use condoned. Rather, a balance is achieved by acknowledging that cannabis use is associated with both risks and benefits and centering the importance of evidence. Moreover, harm reduction-oriented resources like this one did not dismiss youth as being ‘too young’ or immature to understand the consequences of their actions, but instead highlighted youth agency and capacity to make informed decisions.

The use of evidence within the included resources was taken up to varying degrees among both abstinence and harm reduction-based materials. For example, while some resources were well-cited and worded using value-neutral terms, others provided minimal to no references for stated claims. Additionally, those resources that reported exclusively on negative side effects of cannabis use often appeared to have ‘cherry picked’ the cited literature, excluding other evidence that may be contrary. One harm reduction-based resource produced by an American non-profit organization noted this bias in its messaging to parents and encouraged critical appraisal of resources:

Learn about the array of drugs available to young people but be sure your sources are scientifically grounded and balanced. Any source that fails to describe both risks and benefits should be considered suspect. (Resource #56)

Further, while some abstinence-based resources mentioned potential benefits of medical uses for cannabis, many did not. Among the resources that did acknowledge prescribed uses for cannabis, an implicit or explicit prohibitionist stance was often present. For example, an American resource produced by a multisectoral coalition group reads, “While the suffering of these people is undeniable, the legalization of ‘medical’ or recreational marijuana others may push for would not be good for [state]” (Resource #13).

Conceptualizations of cannabis use

Within the reviewed materials, there was a strong tendency for abstinence-based resources to consolidate cannabis use materials together in a resource with other (currently illicit) drugs. These resources framed ‘any and all drug use’ as ‘harmful to the teenage brain’. In doing so, there is an implicit message that all drugs have the same (harmful) effects on youth. For example, a resource developed by an American non-profit organization stated:

The new marijuana landscape doesn’t change the fact that all substances — including marijuana — are harmful for the still-developing teen brain. Your teen’s brain is not fully developed until he is in his mid-20s. During the adolescent years, your teen is especially susceptible to the negative effects of any and all drug use. (Resource # 17)

This highlights a central theme among the abstinence-based resources – that any drug use, no matter what the substance or pattern, is inherently unacceptable and harmful. It frames cannabis and other drug use as a universal in experience, with everyone having the same ‘consequences’. Furthermore, in the abstinence-based resources identified, cannabis use is often dichotomized into non-use versus addiction or dependence.

In contrast, those resources informed by a harm reduction orientation often acknowledged the spectrum of psychoactive substance use – from abstinence through to harmful use and dependency. For example, in a resource developed by a Canadian research institute and a health department, the differences between substance use (in general) and problematic use are detailed:

Substance use – people use different kinds of drugs, like caffeine, alcohol and cannabis, for many reasons; some use it to relax or feel good. Depending on the substance and how often someone uses it, it may or may not lead to problems. Problematic use – is substance use that causes negative health and social consequences. (Resource #54)

In this illustration, the effects of cannabis are not conflated with those of other drugs, as in the previous examples. Indeed, in contrast to the ‘all or nothing’ language used in most abstinence-based resources, those grounded in harm reduction acknowledged that cannabis ‘may or may not lead to problems’, with problematic use framed largely in the context of negative health and social consequences.

Language choices

Within the identified resources, fear-based language remained prominent, particularly within those classified as abstinence-based. For example, a resource developed by an American substance use treatment centre reads:

If you think that your teen has developed a marijuana addiction, you are in a position to take necessary action. As a parent, you can legally force a child under the age of 18 to attend inpatient addiction treatment. Of course, forced rehab should be considered a last-resort option when all other methods have been exhausted. And though you may be labeled "the bad guy" for a little while, your teenager will be alive and well…and that's what matters. (Resource #1).

Here, the focus is solely on the extreme end of the substance use spectrum (i.e. cannabis use disorder) and the language of keeping children ‘alive and well’ suggests that the inaction of parents could result in extreme harm to their child, even death. While the resource stated that forced rehab should be a ‘last resort option’; the implicit message is that parental inaction can result in significant harm and that any degree of cannabis use will lead to dependency. This lack of nuance in presenting cannabis use patterns may lead some parents to misinterpret all cannabis use as problematic or reflective of cannabis use disorder. Similar sentiments were identified in other resources, including one produced by an American coalition group, developed with the support of a health department:

Get help at the first sign of trouble. Parents often underestimate the seriousness of drug use, especially with alcohol and marijuana. Seek out a professional and ask for help… Your child’s future depends on it. (Resource #40)

In this resource, details on what would constitute ‘the first sign of trouble’ are not provided and therefore left to individual interpretation. Further, other messaging and accompanying imagery (e.g. a no cannabis sign), suggest that there is no level of cannabis use that is without harm. By not ‘reaching out for help’, parents are therefore framed as putting their child’s future at risk.

In addition to fear-based messaging, many of the identified resources also included stigmatizing language. For example, an abstinence-oriented resource developed by an American substance use treatment centre used pejorative and stigmatizing terms, including referring to people who experience substance use disorders as ‘addicts’:

Many people who smoke weed behave like addicts. I’ll bet you know kids who obsess about how and when they’re going to get high again. Some of them steal money from family members and do other things they aren't proud of to get money for it. (Resource #22)

Similarly, a resource developed by an American health department used derogatory language, such as ‘pothead’ within the context of fear-based messaging about the loss of life opportunities:

Teach them that if they want to reach their goals, they need to focus on more than just marijuana. Being labeled a “pothead” could hurt their chances of getting a job or even dating someone they like. (Resource #41)

Labels like ‘addict’ and ‘pothead’ were used in these materials to denote undesirable social groups that parents should protect their children from. This ‘othering’ was used to highlight the social ‘consequences’ of cannabis use, with assumptions about who would make a ‘suitable’ or desirable romantic partner. Further, these resources capitalized on fears of social and professional rejection, without providing substantiating evidence of these social impacts.

Of note, such stigmatizing terminology was not solely identified in abstinence-based resources. For example, a resource developed by a cannabis advocacy group stated, ‘Make a distinction between responsible use and being a ‘pothead’’ (Resource #35) in an effort to encourage less harmful forms of use. This approach may serve to legitimize ‘responsible use’ by the cannabis industry but at the cost of further stigmatization of those who use more frequently as the irresponsible and undesirable ‘other’.

This harmful messaging was explicitly called to attention in many of the harm-reduction-oriented resources, which highlighted the potential harm that could result. In a resource developed by a Canadian research institute, parents were encouraged to consider their own biases: ‘Are you using language that could reveal your biases about cannabis? For example, do you use stigmatizing terms such as stoner, pothead, druggie or burnout?’ (Resource #58). Similarly, in a resource developed by a Canadian non-profit group, parents were educated about stigma and the implications for building a trusting relationship with youth:

A recent Canadian report on adolescent cannabis perceptions noted that young people fear being caught by parents or police because they don’t want to be labeled as a “drug user.” This is generally aligned with stereotypes around frequent cannabis users, such as being known as a “stoner,” “pothead,” or “druggie.” Stigma can act as a barrier in engaging youth in open and honest conversations around cannabis use and their own experiences. (Resource #33)

Assumptions regarding family structures

An analysis of both the textual and imagery content of identified resources revealed that the vast majority of family-targeted educational materials assumed ‘traditional’ family structures (i.e. heteronormative and nuclear families), with a limited representation of the diversity of family structures. Resources typically targeted ‘parents,’ with no mention of caregivers or other adults who may be positioned in a parental role. Further, most imagery was of white, middle- or upper-class families with cis-gender mother-father dyads. Other types of family structures, such as blended families with stepparents, caregivers or guardians who are not biological parents, foster families, or extended family members (like grandparents, aunts, or uncles) who act as primary caregivers were mostly unmentioned. This tendency is illustrated through a word frequency count. The word ‘parent’ and its derivatives (parent, parents, parental) was the seventh (7th) most commonly used word within the dataset (mentioned 857 times), while ‘family’, ‘adult’, ‘ally’, ‘caregiver’ and ‘guardian’ were used much less frequently (i.e. these terms were among the 40th to 769th most commonly used words within the included resources). Overall, six of the 59 resources opted for a more general term to denote their target audience, selecting language such as ‘youth allies’, which was described as inclusive of parents, mentors, coaches, health professionals, or ‘any person who is trusted by youth’. (Resource #58)

While the conceptualization of ‘family’ was represented in limiting ways across most resources, so too was attention to diverse identities, such as families who include LGBTQ2S + members. For example, only one resource made mention of families with youth who may identify as LGBTQ2S+, though this did not extend to the parents or guardians, and none of the imagery depicted two parents of the same gender expression. Finally, while some resources used the imagery of ethnically diverse youth or families, it remained infrequent.

In addition to assumptions of a heteronormative, white, nuclear family audience, most resources reflected a middle-class social context. Parental strategies to prevent cannabis use or initiate cannabis conversations often presumed family contexts in which parents were present and available in terms of time and financial assets. Several resources, for example, stressed the importance of parents eating dinner regularly with their teens, keeping youth occupied with extracurricular activities like music lessons or sports teams, or talking with them while travelling in the car. These strategies may be inappropriate or of limited value to families experiencing financial deprivation, where parents work shiftwork or have multiple jobs, and/or live in circumstances where other extraneous stressors limit the application of these tactics.

While there was a limited reflection of diverse family compositions and circumstances, there was also a paucity of resources acknowledging the ways in which the social determinants of health operate to influence cannabis use in youth. In resources that did refer to social determinant influences, the explanation was usually brief and superficial, focusing on 1) how family, school, and community environments may shape youth substance use trajectories or 2) how family substance use or addiction, mental illness, or trauma, can be a risk factor for youth cannabis use. Important social determinants that may intersect and contribute to health and social inequities linked to youth substance use, such as racism, discrimination, and marginalization, were typically unexplored, though there were a few notable exceptions. One Canadian harm reduction-oriented resource (Resource #35), included a brief description of how intersecting issues of racism, socioeconomic stability, affordable housing, and other social inequities impacted substance use and the effectiveness of substance use education and prevention initiatives. Another resource developed by an American non-profit organization (Resource #56) directly refuted the implicit assumption – present in many resources – that parents will have the financial means to enroll their children in extracurricular activities. This resource reads: ‘Extracurricular programs such as sports, arts, drama and other creative activities should be available to all secondary school students, at low or no cost to parents’. In including this statement, this resource is explicit in its position that the cost burden for youth extracurricular activities should not fall to families, in an effort to facilitate equitable access to such health-promoting and substance use prevention programming. In addition, a harm reduction-based resource developed by a Canadian non-profit organization highlighted the importance of taking a contextualized approach to cannabis education and prevention:

The best approach [to cannabis education] depends on context; age, cultural considerations, and realities of youth’s experiences are all factors in deciding which approach is right… Acknowledging issues related to racism, social justice, and stigma also allows the educator or parent to tailor programs or conversations to the context, particularly when working with vulnerable populations. (Resource #33)

With little attention to diverse contexts and their influence on cannabis use patterns or the implications for approaches to education, most of the identified resources focused narrowly on how individual parent behaviours affect youth’s cannabis use decision-making. This manifests as messaging about parental ‘role modelling’, with 21 of the identified resources (36%) discussing the importance of setting a ‘good example’ for children. This included encouraging parents to reflect on their own substance use – including cannabis use – and modifying their behavior for the benefit of their children:

Be a role model – your own choice to use drugs will affect your teen’s decisions about using or trying drugs. It is best not to use cannabis or other drugs in front of your children/teens. Don’t show them that using drugs is a way to have fun or to cope with stress. (Resource #4)

While some of the resources were encouraging in tone, some were more direct, positioning parental use of substances as ‘wrong’:

Coming home from a stressful day of work and pouring a drink or smoking a joint sends the wrong message to a child who needs to learn positive coping mechanisms to difficult situations… Therefore, you’re going to want to try to eliminate or significantly cut back on your substance use during your children’s impressionable adolescent years. (Resource #37)

This example is illustrative of how many resources dichotomized substance use, essentially taking an all or nothing stance, and considering drug use as a uniform experience across the spectrum and types of use. Additionally, for parents who use cannabis, and particularly those who have used it in the past, some resources urged them to frame their past use as a ‘mistake’ when questioned by youth:

If you did use marijuana as a teen or young adult, it’s best to vaguely describe the circumstances and rationale behind your usage. However, it’s important to also emphasize the negative effects the drug had at the time as well as what inspired you to abstain. Just because you used marijuana in the past doesn’t give your teen permission to do so now, but you can frame the conversation in a way that you’re trying to help them not make the mistakes you did. (Resource #37)

Another example from a resource developed by an American substance use treatment centre, provided a script for parents to use when talking about their past use with their child:

[Parent’s response to a teenager]: I can tell you that my life is no better because I smoked pot. I admit to making some poor decisions when I was your age, but I made some good decisions, too. One of them was moving beyond that risky behavior. (Resource #22)

This strategy makes the key assumption that parents or caregivers perceive their past or current use to be problematic, a ‘poor decision’, or a mistake, encouraging parents to express these beliefs to their children. It also perpetuates an ideal or ‘model parent’ that may be irrelevant, inauthentic, or unattainable for many parents who use cannabis.

Discussion

The legal status of non-medical cannabis use has been shifting throughout much of North America in recent years. Within this context, there is a priority need for cannabis education resources – targeting parents and caregivers – to reduce the potential harms of cannabis use among youth. Using an environmental scanning technique, we mapped and critically analyzed the available cannabis resources for use in family contexts, identifying 60 materials aimed at supporting parents or caregivers in facilitating cannabis-related conversations with youth. The majority of resources were developed in America, followed by Canada and then Australia and the UK. There has been a proliferation of such resources in recent years, with most being published since 2018 – which aligns with the changing legislative landscape.

Overall, the identified resources predominantly approached cannabis and cannabis use from one of two polarized philosophical orientations to substance use – abstinence or harm reduction. Abstinence-based resources focused heavily on the negative consequences of youth cannabis use, while those resources adopting a harm reduction approach were more often balanced in their messaging, acknowledging both the potential harms and benefits of cannabis use for youth. Additionally, the harm reduction-based resources tended to include more nuanced messaging, referencing the spectrum of substance use, the contexts that contribute to greater substance use risks, as well as the various reasons for use (i.e. medical and non-medical). Such comprehensive and nuanced approaches to youth cannabis use are critical and, as Hyshka (Citation2013) argued, family-based substance use education that aims to minimize or reduce harms, not simply prevent all use by youth, is a public health priority.

Indeed, the need for cannabis education resources that move beyond abstinence messaging is well supported by available research evidence (Bruno & Csiernik, Citation2020). For example, past research on widely implemented abstinence-based educational interventions indicates that such programming is ineffective in reducing substance use (Canadian Paediatric Society, Citation2008). Moreover, these ‘just say no’ approaches can inadvertently harm by failing to provide youth with the knowledge and resources to more safely navigate their substance use practices (Slemon et al., Citation2019). In a position statement released by the Canadian Paediatric Society (Citation2008), they note that education grounded in a harm reduction orientation is ‘congruent with what we know about adolescent development and decision-making. Adolescence is a time of experimentation and risk-taking. Adolescents also tend to reject authority and strive for autonomy in their decision-making.’ (p. 53).

Beyond the scientific evidence, Kozlowski (Citation2020) provides an argument grounded in a public health bioethical framework, which frames youth access to harm reduction-oriented messaging about substance use as a human right. Kozlowski notes the disparities in substance use harms among youth who experience health and social inequities and suggests that youth have an ethical and human right to health-related information. Further, she asserts that ‘our “thinking” about these issues needs to go beyond our ‘feelings’’ (p. 1052) and instead be grounded in critical and systematic scientific evidence and principles of public health ethics. This perspective is particularly relevant in the context of marginalized or vulnerable family contexts. For example, Kozlowski notes, drawing on examples from tobacco control, that ‘where nicotine/tobacco use is treated as a minority, stigmatized activity (especially one that might threaten the privileged majority), the rights of youth…who are using these products are especially at risk of being neglected’ (p. 1052). The feeling that harm reduction is taboo or will contribute to a proliferation of use must be reconsidered in the face of scientific evidence demonstrating that such a perspective perpetuates stigma and health inequities among already marginalized or vulnerable groups, including young people who use drugs. While our previous research in youth substance use found that youth can be quite capable of weighing the risks and benefits of cannabis use if provided with appropriate supports (Moffat et al., Citation2013), abstinence-based resources tended to position youth as immature and unable to assess risk. In contrast, resources grounded in principles of harm-reduction tended to position youth as having agency and decision-making capabilities. The differences between resources from these two perspectives were also notable in terms of their portrayal of other substance use, wherein abstinence-based resources often conflated the harms of cannabis use with those of other, currently illicit, drugs. In this way, the now outdated gateway theory of drug use, which theorizes youth cannabis use as a steppingstone to ‘hard’ drugs is perpetuated (Jorgensen & Wells, Citation2021; Moffat et al., Citation2009). Moreover, equating the harms of cannabis with those associated with other drugs, or cautioning youth that any and all forms of cannabis use will lead to addiction to other drugs, does a disservice to youth. Indeed, such an approach fails to provide youth with evidence of specific cannabis-related harms and strategies to reduce the risks that do exist. This also disregards the spectrum of psychoactive drug use and misses a valuable opportunity to equip parents to support their teens in developing the skills to recognize when use becomes problematic and to prevent problematic use (Slemon et al., Citation2019). Education incorporating the guidelines for lower-risk cannabis use and the spectrum of psychoactive use can provide concrete, actionable and evidence-based strategies to guide parent and caregiver discussions about cannabis to avoid spreading misconceptions or misinformation (Fischer et al., Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2020). Yet without mention of the contexts of cannabis use, the spectrum of use, or ways that parents or caregivers can model or discuss ‘responsible’ use, there is a clear message that abstaining from substance use is ‘good’ and ‘healthy’, while using substances – of any kind or amount – is inherently ‘unhealthy’ and ‘bad’. It also equates being a ‘good parent’ one who abstains from the use of cannabis and other drugs.

In conducting this environmental scan, it also became apparent that the use of stigmatizing language within current family-oriented cannabis resources is highly prevalent, particularly in framing the effects of cannabis use, decision-making about use, and referring to people who use cannabis. Stigmatizing language and othering of people who use cannabis is a remnant of cannabis prohibition and the moral model of substance use (Taylor, Citation2016). However, in previous qualitative research with youth, we have found that youth are highly skeptical of strategies that use stigmatizing terms and tend to ‘tune out’ or dismiss people who use discourse such as ‘potheads’ or ‘addicts’ (Bottorff et al., Citation2009; Johnson, Citation2014; Moffat et al., Citation2013). Similarly, findings from interviews with Canadian parents who use cannabis suggest that stigma associated with use is persistent, despite legalization, and poses barriers to open and honest discussions about cannabis use between parents and their adolescent children (Dearden et al., Citation2020).

Another critical finding of this environmental scan was that current resources often position parental role modeling as a key strategy for preventing cannabis-related harm. However, many abstinence-based resources advise parents to speak vaguely about previous use experiences, cease personal use, and refer to previous use as a mistake. Ultimately, such approaches normalize abstinence from cannabis, even in a context where it is highly prevalent and legal, which our past research has identified can result in youth feeling that they do not have the coping strategies or trusted sources of support when they need help managing their substance use (Slemon et al., Citation2019). In addition to prioritizing being ‘substance free’, most of the identified resources also depicted the family context in non-inclusive ways. The tendency to portray a generic family context may intentionally appeal to a broad base; however, even the recognition that some parents may be using cannabis for medical purposes was lacking. Ultimately, this excludes youth and parents from families where cannabis use occurs and reinforces the assumption that abstinence is the only appropriate goal. Moreover, many of the resources were written using complicated language that requires advanced literacy skills. This may inadvertently exclude the use of these resources in some family contexts. The use of plain language principles should be prioritized in the development of cannabis resources and other substance use education to reduce barriers to use (Stableford & Mettger, Citation2007).

Finally, this environmental scan identified a clear and urgent need for family-oriented resources that involve their target audience in co-designing these materials. The meaningful engagement of knowledge users in the research and program design process has long been identified within the participatory research literature as contributing to more valuable and impactful knowledge products (Jenkins et al., Citation2017). Indeed, in our previous research, we emphasize that for ‘harm reduction programing to be effective, it must also be informed by youth experiences’ (Jenkins et al., Citation2017, p. 9). It was notable that although 10 of the 60 resources analyzed involved youth in their development to varying degrees, none – as far as we could tell from available descriptions –involved parents/caregivers in any significant way.

This analysis is the first that we are aware of to catalogue the breadth and scope of family-oriented cannabis resources; however, some limitations warrant acknowledgment. Specifically, in the absence of published evaluations of the identified resources, we lack data on how parents or caregivers have used and experienced them and whether they found them helpful. For example, while our critical analysis identified several weaknesses within current resources, it is possible that some parents or other caregivers may garner useful information from these materials, even in instances where they do not fully ‘buy in’ to the approach or take up all of the suggestions offered. Further, the intention of the environmental scanning approach is to map the current scope of available materials on a particular topic and does not include formal assessments or metrics of quality. Additionally, our search did not include the terms ‘son’ or ‘daughter’, which could have resulted in some relevant resources being missed. Finally, due to resource restrictions, our search was limited to those materials available in English, potentially missing other relevant resources available in different languages.

In conclusion, this environmental scan maps the current landscape of parent-targeted, online, English-language cannabis resources – capturing materials produced across several contexts, including America, Canada, Australia and the UK. Critical content analysis of these resources provides insights into the information and advice provided to parents and caregivers, suggesting that abstinence is the predominant approach, even in the context of early cannabis legalization. Online cannabis education resources geared towards parents currently lack balance and inclusive information, focus on cannabis harms and risks, and provide a little discussion of potential benefits or responsible use. Given this, there remains a priority need for holistic approaches to addressing cannabis use – ones that aim to minimize or reduce harms, not simply prevent all use by youth. Resources should be co-developed with their intended audience to enhance applicability and appropriateness (i.e. youth and parents/caregivers, including those who use cannabis). Additionally, the resources should be written in plain, accessible and non-stigmatizing language; and should be geared toward reducing inequities by representing diverse family contexts that support resource utilization within families who may benefit most.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their appreciation to Caitlyn Andres for her contributions to the search approach and early analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request sent to the lead author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adinoff, B., & Cooper, Z. D. (2019). Cannabis legalization: Progress in harm reduction approaches for substance use and misuse. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 45(6), 707–712.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2012, September). Clinical guidelines and recommendations. Retrieved May 19, 2021, from https://www.ahrq.gov/prevention/guidelines/index.html

- Bogt, T. F., Looze, M., Molcho, M., Godeau, E., Hublet, A., Kokkevi, A., Kuntsche, E., Nic Gabhainn, S., Franelic, I. P., Simons-Morto, B., Sznitman, S., Vieno, A., Vollebergh, W., & Pickett, W. (2014). Do societal wealth, family affluence and gender account for trends in adolescent cannabis use? A 30 country cross-national study. Addiction, 109(2), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12373

- Bok, M., & Morales, J. (2000). Harm reduction: Dealing differently with adolescents and youth. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents & Children, 3(3), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1300/J129v03n03_06

- Bottorff, J. B., Johnson, J. L., Moffat, B. M., & Mulvogue, T. (2009). Relief-oriented use of marijuana by teens. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 4(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-4-7

- Bruno, T. L., & Csiernik, R. (2020). An examination of universal drug education programming in Ontario, Canada’s elementary school system. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(3), 707–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9977-6

- Butters, J. E. (2005). Promoting healthy choices: The importance of differentiating between ordinary and high risk cannabis use among high-school students. Substance Use & Misuse, 40(6), 845–855. https://doi.org/10.1081/ja-200030803

- Canadian Paediatric Society. (2008). Harm reduction: An approach to reducing risky health behaviours in adolescents. Paediatric Child Health, 13(1), 53–56.

- Choo, C. W. (2001). Environmental scanning as information seeking and organizational learning. Information Research, 7(1), 1–37.

- Dearden, T., Jenkins, E., McGuinness, L., & Haines-Saah, R. (2020). TRACE4Parents: Preventing the health harms of youth cannabis use in contexts of parental cannabis use. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 23.

- Dupont, H. B., Candel, M. J., Kaplan, C. D., van de Mheen, D., & de Vries, N. K. (2016). Assessing the efficacy of MOTI-4 for reducing the use of cannabis among youth in the Netherlands: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 65, 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2015.11.012

- Fischer, B., Russell, C., Sabioni, P., Van Den Brink, W., Le Foll, B., Hall, W., Rehm, J., & Room, R. (2017). Lower-risk cannabis use guidelines: A comprehensive update of evidence and recommendations. American Journal of Public Health, 107(8), e1–e12.

- Fusco, R. A., & Newhill, C. E. (2021). The impact of foster care experiences on marijuana use in young adults. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 21(1), 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2020.1870286

- Guerin, N., & White, V. (2018). ASSAD 2017 statistics & trends: Australian secondary students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, over-the-counter drugs, and illicit substances. Cancer Council Victoria. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/secondary-school-students-use-of-tobacco-alcohol-and-other-drugs-in-2017

- Hathaway, A. (2019). Evidence‐based policy development for cannabis? Insights on preventing use by youth. Canadian Public Administration, 62(4), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1111/capa.12350

- Health Canada. (2019). Canadian student tobacco, alcohol and drugs survey. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-student-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2018-2019-detailed-tables.html

- Hyman, S. M., & Sinha, R. (2009). Stress-related factors in cannabis use and misuse: Implications for prevention and treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36(4), 400–413.

- Hyshka, E. (2013). Applying a social determinants of health perspective to early adolescent cannabis use–An overview. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 20(2), 110–119.

- Jenkins, E. K., Slemon, A., & Haines-Saah, R. J. (2017). Developing harm reduction in the context of youth substance use: Insights from a multi-site qualitative analysis of young people’s harm minimization strategies. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0180-z

- Johnson, J. (2014). Cycles – Facilitator’s manual. An educational resource exploring decision making and marijuana use among young people. https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/carbc/assets/docs/cycles-guide.pdf

- Johnston, L. D., Miech, R. A., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., & Patrick, M. E. (2019). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2018: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research.

- Jorgensen, C., & Wells, J. (2021). Is marijuana really a gateway drug? A nationally representative test of the marijuana gateway hypothesis using a propensity score matching design. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1–18.

- Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., Lowry, R., Chyen, D., Whittle, L., Thornton, J., Lim, C., Bradford, D., Yamakawa, Y., Leon, M., Brener, N., & Ethier, K. A. (2018). Youth risk behavior Surveillance – United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1–114. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1

- Kozlowski, L. T. (2020). Younger individuals and their human right to harm reduction information should be considered in determining ethically appropriate public health actions. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 22(6), 1051–1053. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz049

- Lee, C. R., Lee, A., Goodman, S., Hammond, D., & Fischer, B. (2020). The lower-risk cannabis use guidelines’(LRCUG) recommendations: How are Canadian cannabis users complying? Preventive Medicine Reports, 20, 101187.

- Mader, J., Smith, J. M., Smith, J., & Christensen, D. R. (2020). Protocol for a feasibility study investigating the Ucalgary’s Cannabis Café: Education and harm reduction initiative for postsecondary students. BMJ Open, 10(2), e032651.

- McKay, M., Sumnall, H., McBride, N., & Harvey, S. (2014). The differential impact of a classroom-based, alcohol harm reduction intervention, on adolescents with different alcohol use experiences: A multi-level growth modelling analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 37(7), 1057–1067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.07.014

- Meredith, L. R., Maralit, A. M., Thomas, S. E., Rivers, S. L., Salazar, C. A., Anton, R. F., Tomko, R. L., & Squeglia, L. M. (2021). Piloting of the just say know prevention program: A psychoeducational approach to translating the neuroscience of addiction to youth. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 47(1), 16–25.

- Midford, R. (2010). Drug prevention programmes for young people: Where have we been and where should we be going? Addiction, 105(10), 1688–1695. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02790.x

- Midford, R., Mitchell, J., Lester, L., Cahill, H., Foxcroft, D., Ramsden, R., Venning, L., & Pose, M. (2014). Preventing alcohol harm: Early results from a cluster randomised, controlled trial in Victoria, Australia of comprehensive harm minimisation school drug education. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25(1), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.05.012

- Moffat, B. M., Jenkins, E. K., & Johnson, J. L. (2013). Weeding out the information: An ethnographic approach to exploring how young people make sense of the evidence on cannabis. Harm Reduction Journal, 10(1), 34.

- Moffat, B. M., Johnson, J. L., & Shoveller, J. A. (2009). A gateway to nature: Teenagers’ narratives on smoking marijuana outdoors. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.05.007

- Nelson, E. U. E. (2021). I take it to relax… and chill’: Perspectives on cannabis use from marginalized Nigerian young adults. Addiction Research & Theory, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2021.1895125

- Nelson, S. E., Van Ryzin, M. J., & Dishion, T. J. (2015). Alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use trajectories from age 12 to 24 years: Demographic correlates and young adult substance use problems. Development and Psychopathology, 27(1), 253–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000650

- Poulin, C., & Nicholson, J. (2005). Should harm minimization as an approach to adolescent substance use be embraced by junior and senior high schools? Empirical evidence from an integrated school- and community-based demonstration intervention addressing drug use among adolescents. International Journal of Drug Policy, 16(6), 403–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.11.001

- Rowel, R., Moore, N. D., Nowrojee, S., Memiah, P., & Bronner, Y. (2005). The utility of the environmental scan for public health practice: Lessons from an urban program to increase cancer screening. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(4), 527–534.

- Silins, E., Horwood, J. L., Patton, G. C., Fergusson, D. M., Olsson, C. A., Hutchinson, D. M., Spry, E., Toumbourou, J. W., Degenhardt, L., Swift, W., Coffey, C., Tait, R. J., Letcher, P., Copeland, J., & Mattick, R. P. (2014). Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: An integrative analysis. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 1(4), 286–293.

- Slemon, A., Jenkins, E. K., Haines-Saah, R. J., Daly, Z., & Jiao, S. (2019). You can’t chain a dog to a porch”: A multisite qualitative analysis of youth narratives of parental approaches to substance use. Harm Reduction Journal, 16(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-019-0297-3

- Stableford, S., & Mettger, W. (2007). Plain language: A strategic response to the health literacy challenge. Journal of Public Health Policy, 28(1), 71–93.

- Stemler, S. (2001). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(17), 1–6.

- Taylor, S. (2016). Moving beyond the other: A critique of the reductionist drugs discourse. Tijdschrift over Cultuur & Criminaliteit, 6(1), 100–118. https://doi.org/10.5553/TCC/221195072016006001007

- Vermeulen-Smit, E., Verdurmen, J. E. E., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2015). The effectiveness of family interventions in preventing adolescent illicit drug use: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18(3), 218–239.

- Villanueva, V. J., Puig-Perez, S., & Becoña, E. (2021). Efficacy of the “Sé tú Mismo” (be yourself) program in prevention of cannabis use in adolescents. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19(4), 1214–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00219-6

- Walton, M. A., Resko, S., Barry, K. L., Chermack, S. T., Zucker, R. A., Zimmerman, M. A., Booth, B. M., & Blow, F. C. (2014). A randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of a brief cannabis universal prevention program among adolescents in primary care. Addiction, 109(5), 786–797. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12469

- Watson, T. M., & Erickson, P. G. (2019). Cannabis legalization in Canada: How might ‘strict’ regulation impact youth? Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 26(1), 1–5.

- Watson, T. M., Valleriani, J., Hyshka, E., & Rueda, S. (2019). Cannabis legalization in the provinces and territories: Missing opportunities to effectively educate youth? Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 110(4), 472–475.

Appendix

Table A1. Summary of resources.