Abstract

Homelessness and heavy alcohol consumption are increasing global public health concerns. Homelessness is associated with poorer health outcomes, shorter life expectancy, and health risk behaviours. High levels of alcohol consumption intersect with the cause and effect of homelessness making this an important consideration for research. This is explored through a theoretical lens of recovery capital, referring to the resources required to initiate and maintain recovery, and is applied to both heavy alcohol consumption and homelessness. Life history calendars were utilised alongside semi-structured interviews to explore the impact that adverse life events had on alcohol consumption and living situations with 12 participants in contact with homelessness services in North-West England. The findings consider how social, health, and structural-related adverse life events were both a cause and effect of homelessness and increasing consumption of alcohol, which were further exacerbated by a lack of recovery capital. The authors argue for further consideration relating to the intersection of homelessness and high levels of alcohol consumption in relation to recovery capital. The findings have implications for policy and practice by demonstrating the need for relevant services to help individuals develop and maintain resources that will sustain recovery capital.

Introduction

Homelessness is an increasing global public health concern (Busch-Geertsema et al., Citation2016). Homelessness refers to those who sleep rough (in areas not intended for habitation), those in temporary accommodation, and those who stay with family and friends. Homelessness is difficult to measure. In the UK, figures for rough sleepers often rely on ‘point in time counts’ (Homeless Link, Citation2017; Smith, Citation2015) meaning those staying with friends and family are often omitted from statistics. Busch-Geertsema et al. (Citation2016) argue that a current estimate of global homelessness would be impossible to generate under current circumstances due to inconsistent data and thus figures relating to homelessness in the UK and across the world are likely to be underestimated. Nevertheless, it is clear that homelessness is increasing. For example, in the UK, the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) noted a 16% increase in the number of rough sleepers between 2015 and 2016 (Department for Communities and Local Government, Citation2015). Furthermore, in England, there were 79,880 households in temporary accommodation in March 2018, a 3% increase from the previous year (Ministry of Housing and Local Government, Citation2018). A lack of affordable and social housing (Tunstall et al., Citation2013), increasing benefit sanctions (Beatty et al., Citation2015; Reeve, Citation2017) and restrictions imposed on those with no recourse for social funds (Dwyer et al., Citation2018; Homeless Link, Citation2016) are all thought to contribute to the increasing levels of homelessness in the UK.

Homelessness within high-income countries has been associated with a number of poor health outcomes (Fazel et al., Citation2014) such as poor nutrition (Sprake et al., Citation2014), unintentional injuries (Mackelprang et al., Citation2014; Topolovec-Vranic et al., Citation2012), communicable disease (Beijer et al., Citation2012; Aldridge et al., Citation2018) ; poor dental health (Paisi et al., Citation2019) and poor mental health (Fazel et al., Citation2008). Those that are homeless have a reduced life expectancy, for example, in the UK the life expectancy of a homeless adult is 47 years compared with 77 years for the general population (Thomas, Citation2012).

Heavy drinking is also a significant public health issue (Room et al., Citation2005). Globally, alcohol consumption was responsible for 2.44 million deaths in 2019 (IHME, Citation2019), and drinking high quantities of alcohol has been associated with a number of risks including disease, addiction, unintentional injury, victimisation, and perpetration of crime and mental health disorders (Ritchie & Roser, Citation2019; Room et al., Citation2005). In England, 24% of adults regularly drink over the Chief Medical Officer’s low-risk guidelinesFootnote1 (Department for Health, Citation2016; Public Health England, Citation2016). Furthermore, in England, there are an estimated 586,780 people who have an addiction to alcohol but only 18% are receiving treatment (Public Health England, Citation2018, Citation2019). Alcohol consumption amongst those who are homeless is often higher than the general population (Jones et al., Citation2015). A study by Fallaize et al. (Citation2017) that compared dietary intake between homeless men and men transitioning into stable accommodation found a significant difference with regards to high-risk drinking, with those who were sleeping rough being more likely to engage in risky drinking practices. Furthermore, as part of a wider population study, Jones et al. (Citation2015) collected data regarding the number of units of alcohol consumed by 200 participants residing across 12 UK hostels and made comparisons to a general population sample. They found that for those who resided in a hostel, the mean unit consumption on ‘typical drinking days’ was 17.0 ± 2.8 units for men and 16.3 ± 2.4 units for women. Compared to the general population sample, those who resided in a hostel consumed 97.1% (men) and 222.1% (women) more units per week (Jones et al., Citation2015).

Drinking high quantities of alcohol is known to reduce life expectancy (Rehm et al., Citation2018), thus those individuals who are both homeless and engaging in heavy drinking are at an increased risk of comorbidity as a result. Moreover, those who are homeless often lack consistent access to appropriate healthcare (Baggett et al., Citation2010; Canavan et al., Citation2012; Paisi et al., Citation2019). Those faced with multiple and intersecting inequalities including substance use, mental ill-health, and homelessness face multiple disadvantages, which establishes the importance of considering intersectionality. This is demonstrated in the disadvantage faced when accessing appropriate support. A systematic review and meta-ethnography carried out by Carver et al. (Citation2020) found that those who are homeless and require treatment for substance use-related issues, such as heavy drinking, require individualised complex support to suit their needs. This level of support is not always accessible, and often those who are homeless lack the means to access the recovery-related support that is necessary to address their own distinct needs (Carver et al., Citation2020; Parkes et al., Citation2019).

Drinking high quantities of alcohol, as well as other forms of substance use, are linked with the cause and effect of homelessness (Fountain et al., Citation2003). Roca et al. (Citation2019) found that many of the common issues that led to homelessness, such as chronic health problems and experiencing traumatic and stressful life events were further exacerbated by heavy drinking. Furthermore, research has demonstrated how the intersection of homelessness and high levels of alcohol consumption can also lead to additional complications with poor health outcomes (Ijaz et al., Citation2017). Substance use, including drinking high levels of alcohol, also correlates with an increase in the length of time an individual remains homeless (Fountain et al., Citation2003) further demonstrating why the intersection between alcohol consumption and homelessness is of interest.

Recovery capital

Recovery capital, originally founded on the concept of social capital (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992) relates to the quantity and quality of resources available to an individual, to initiate and sustain recovery from addiction (Cloud & Granfield Citation2008). Best and Laudet (Citation2010) operationalise recovery capital by dividing the concept into three categories: personal recovery capital (such as personal skills and capabilities as well as personal); social recovery capital (relationships and social networks) and community recovery capital (such as availability and accessibility of resources such as jobs and housing). Economic capital (such as financial means) also has an important role within recovery capital (Cloud & Granfield, Citation2008).

Whilst traditionally the concept of recovery capital has been applied to addiction, the authors of this paper argue that it could also be applied to both homelessness and heavy drinking and that the intersection between both creates further barriers for those who wish to enhance their recovery capital. Like addiction, homelessness is often the result of a breakdown in different forms of capital and there are similarities between what can lead a person to become homeless and what can lead them to develop risky drinking practices (Padgett et al., Citation2008). When the intersection between homelessness and heavy drinking occurs, the dual issues experienced to create a further reduction in the potential for enhancing recovery capital. This is evidenced through research that has considered severe multiple disadvantages and multiple severe exclusions experienced by those that are homeless (see Bramley & Fitzpatrick, Citation2018; Queen et al., Citation2017) as well as in research that has measured perceived quality of life which incorporates many elements synonymous with recovery capital (Best et al., Citation2020; O’Sullivan et al., Citation2019). Research by O’Sullivan et al. (Citation2019) and Best et al. (Citation2020) consider long-term development of recovery capital highlighting the importance of stability of which secure housing is imperative.

Crucially, there is a crossover between the operational categories of recovery capital (Best & Laudet, Citation2010) and the resources that these categories refer to which can be used by an individual to help them in recovery. Homelessness is often the result of loss of employment, addiction, poor health (both mental and physical), domestic abuse, relationship breakdown, and/or childhood trauma and neglect (Fransham & Dorling, Citation2018; Manthorpe et al., Citation2015). These factors are also related to a person having low recovery capital in relation to alcohol consumption and other forms of substance use (Cloud & Granfield, Citation2008). Personal capital is cited as being essential in establishing the social and peer support needed within the recovery process (Cano et al., Citation2017; Cloud & Granfield, Citation2008; White & Cloud, Citation2008) and a lack of personal capital has also been highlighted as a barrier in securing the means for secure accommodation (Chamberlain & Johnson, Citation2013). Economic capital is a further element of personal capital as argued by Best and Laudet (Citation2010). Economic capital is imperative in accessing secure accommodation (Chamberlain & Johnson, Citation2013; Shinn, Citation2007). Finally, the establishment of community recovery is evidenced through research that has considered the importance of the provision of support services that are available within local communities (Anderson et al., Citation2021; Cano et al., Citation2017; O’Sullivan et al., Citation2019; Paquette & Winn, Citation2016). This highlights the further disadvantage in terms of obtaining and maintaining recovery capital for those who experience the dual issues of heavy alcohol consumption and homelessness as there is often a lack of services that offer support for both.

Aims and objectives

This paper aims to explore the intersection between homelessness and heavy alcohol consumption through a recovery capital lens. In doing so, the research considers how adverse life events relate to both living situations and alcohol consumption and how a lack of recovery capital with regards to both homelessness and heavy drinking can affect outcomes at an individual level.

Method

Generic qualitative research (GQR) was chosen as the qualitative research approach. This flexible and richly descriptive approach does not adhere to a single established methodology but draws on numerous qualitative approaches to understand a phenomenon, a process, or the perspectives of participants (Merriam, Citation1998). Multiple methods of data collection are used to describe a broad range of experiences and reflections (Percy et al., Citation2015). Similar to phenomenology in that both seek to explore and understand a phenomenon through the participants’ experiences, GQR aims to discover the ‘individual’ meaning of a process or phenomenon from the perspective of the participant rather than the ‘shared’ essence of the meaning of a process or phenomenon (Kennedy, Citation2016). As the study sought to understand the impact of significant life events on participants’ living situations and/or alcohol consumption, GQR was deemed appropriate.

The research process that was used for this study included life history calendars (LHCs) embedded within semi-structured interviews (adapted from Porcellato et al., Citation2014). These facilitated the production of in-depth case studies that depicted the participants’ current and previous experiences of homelessness and their drinking practices. Overall, this research adopts a social constructionist approach. Social constructionism considers how the interactions of individuals with their society and the world around them give meaning and create realities (Burr, Citation2003). In terms of this research, utilising a social constructionist approach allowed for the participant’s perceptions of their own realities to be explored to allow for an understanding of how they perceived their own recovery capital as well as their experiences relating to alcohol consumption and homelessness. Permission to carry out this research was granted by the Liverpool John Moores Research Ethics Committee.

Sample

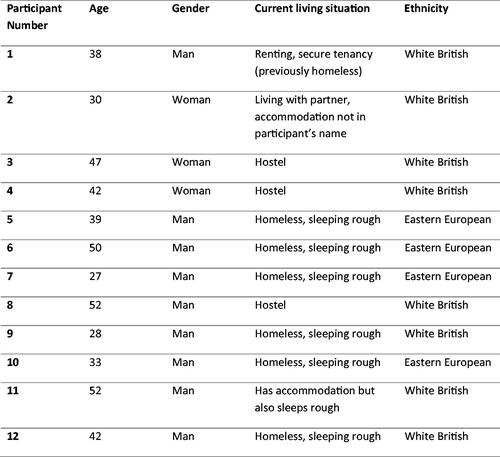

Twelve participants took part in the life history calendar interviews (see ). Most of the participants (n = 11) self-reported their current alcohol consumption as being high, one had been on a detoxification programme and had not consumed any alcohol during the previous fortnight. All of the participants frequently consumed alcohol in excess of the UK Chief Medical Officer’s recommended guidelines for low-risk drinking (Department of Health, Citation2016), and participants also applied their own definitions of what they ascertained to be a high level of consumption. The majority of the participants engaged in polysubstance use (citing use of heroin, cannabis, and cocaine). However, the participants were selected for this study as they all cited alcohol as their primary substance.

Purposive sampling was used; all participants were recruited through a service for homeless and street drinkers in the North-West of England across two locations. To take part in the research, participants had to be over the age of 18, had to be homeless, or have previously been homeless and drink or have previously drunk high quantities of alcohol. Researchers visited both locations a number of times prior to carrying out data collection so that potential participants could become familiar with them. The research team was introduced by staff who worked at the service to help facilitate trust, which is important when working with vulnerable populations (Smith, Citation2008). Potential participants were then asked by the research team if they would participate in the study. Interviews took place in a private room within the services. Staff who worked at the services were available in the event that participants made a disclosure requiring immediate action.

Process

One of the locations allowed alcohol consumption on site. This meant that some participants had been drinking alcohol prior to their participation. Staff who worked at the service helped the research team determine who would be potentially suitable to take part based on their history of alcohol use and whether their current level of intoxication meant that they were able to give informed consent. A potential participant was considered able to give informed consent if they could converse with the researcher about the study and understand the information sheet (determined in collaboration with staff). Signed consent was obtained from all participants. The interviews were carried out by two experienced research assistants and a senior researcher.

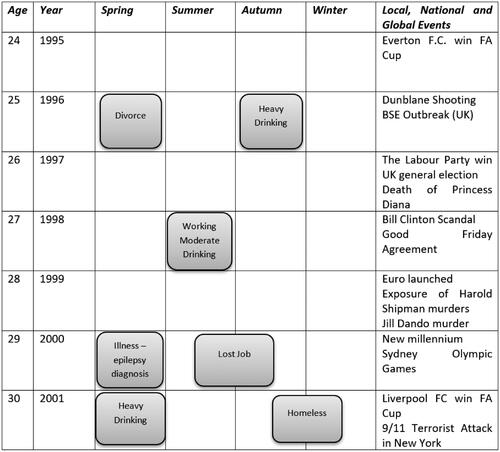

Data was collected using LHCs embedded within semi-structured interviews, which created a visual overview of the participant’s experiences that related to their alcohol consumption and living situation. The interviews included questions around set themes (alcohol consumption/living situation/significant life events) which participants could elaborate on (Bryman, Citation2015). This was then followed up by open-ended questions that were used to probe and explore the participant’s subsequent experiences following these adverse life events. Generic questions and research themes were reviewed by staff who worked within the services. LHCs provide a framework and cues to trigger recall via significant events (e.g. births, relationships, housing, incarcerations, etc.) (Fikowski et al., Citation2014; Porcellato et al., Citation2014), allowing researchers ‘not only to structure the interviews but also to stimulate the interviewees’ reflexivity with regard to their own life trajectories’ (Nico, Citation2016, p. 2109). A calendar grid going back 20 years from the date of the interview was used, as recommended by staff at the services who felt this was an appropriate period based on the typical age of their service users. Each year was broken down quarterly to help simplify the recollection process. The participant’s age was calculated for each year and a list of global and national events for each year was included, to help with recall (see for an example). The calendars were completed during the course of the interview with the help of the researcher if necessary. Participants were provided with stickers to mark critical life events such as marriage, birth, death, incarceration, education, and employment. These were added to the calendar throughout the interview to map the occurrence of these events alongside stickers citing changes in alcohol consumption (abstinent, low, moderate, high) and living situation (stable housing, unstable housing, sleeping rough). In line with the social constructionist approach, the participants defined what constituted these levels of alcohol consumption and decided which life events were ‘significant’ to them. The participants were asked to review the calendar at the end of the interview to ensure accuracy. On average the interviews lasted 1.5 h (in terms of the time sat with the researcher), however, due to the emotive nature of the topics, participants did take frequent breaks so the overall process took a number of hours in some cases. Participants were provided with follow-up support from the services that they engaged with if needed. The interviews were digitally recorded and verbatim transcripts were produced. Given the transient nature of the participants, feedback checks on the write-up of the data were not feasible.

Analysis

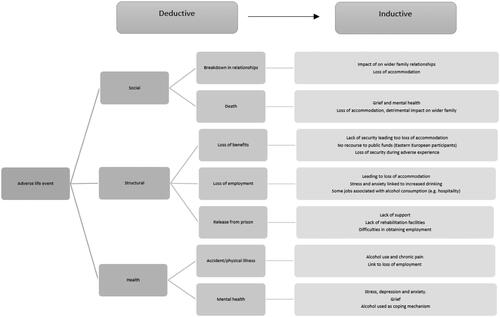

To protect the confidentiality, identifiable data was removed and codes were assigned to each participant. For the interviews, a staged thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Burnard, Citation1991; Burnard et al., Citation2008) was undertaken in QSR NVivo 11 by the lead researcher. This interpretive approach involved the application of deductive, pre-determined codes to all of the text. These were based on the topics within the interview schedule as well as the theoretical framework relating to social and recovery capital. The use of this first stage enabled the lead researcher to become familiar with the data and apply codes that were based on the interview questions to elicit relevant themes. This use of deductive coding is justified by the authors, who argue that it is a way to elicit conceptual themes, such as recovery capital, from data when participants may not use the terminology that directly relates to these concepts, but has described experiences for which the theoretical lens can be applied. Following this, open coding was also undertaken by the lead researcher across all the transcripts in order to identify any additional and unexpected themes. This second stage was repeated by the lead researcher several times until saturation of themes was reached (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The codes were then grouped into categories and emerging research themes were identified. The coding of all the transcripts was then cross-checked by the two research assistants who had assisted in the data collection; discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Results

Following the deductive and inductive coding, there were three clear overarching themes: social, structural, and health. presents an overview of the themes derived from the data. These themes developed from the consideration of similarities across the range of experiences described by the participants (evident through the inductive coding) and also reflect key components of recovery capital (Cloud & Granfield, Citation2008) that came through the application of deductive codes as well as inductive coding. The development of these themes demonstrates the intersection between adverse significant life events with heavy drinking, as well as deterioration in living situation. They also reflect on the challenges faced in terms of developing recovery capital when faced with reoccurring adverse life events. The following provides summaries of the data accompanied by illustrative quotations that reflect the overall themes.

Social – relationships, births, and deaths

Throughout the interviews and production of the LHCs, participants highlighted significant changes in relationships with family members. This included positive changes (such as a new relationship or birth of a child) as well as events that had a detrimental effect (for example a death, a breakdown in a relationship, or becoming a victim of an abusive relationship). The participants discussed how adverse events contributed to a decline in their living situation and/or heavy alcohol consumption. The cyclical nature of adverse life events meant that once participants engaged with heavy alcohol consumption or homelessness it became difficult for them to overcome the adversities. Some participants had depended on partners or family members for housing and the loss of these relationships became a catalyst for homelessness. Two participants discussed domestic violence in relation to their current homelessness. For one participant it had been the main cause of them becoming homeless and drinking large quantities of alcohol, as they moved to a mother and baby refuge and befriended another homeless individual who was drinking heavily. For the other participant, it formed part of a wider breakdown in family relationships brought on by their own high levels of alcohol use that ultimately led to them becoming homeless.

I have been in loads of mother and baby units because my ex-partner battered me…I moved to [name of unit], it’s a shared house. The girl I know who lived there used to drink cider so I used to drink cider with her. (Participant 2)

I used to live with my dad and his girlfriend…I am homeless because I was having murder with my brother. He is mentally ill and set the dog on me. So I just got off, I just walked out because I can’t live with that. (Participant 9)

For both of these participants, alcohol had become a means to cope with the stress and anxiety caused by domestic violence and becoming homeless. This meant that for these participants it was difficult for them to achieve and/or maintain recovery capital in terms of their alcohol consumption as the loss of secure accommodation had impacted their stability. This is an example of how the intersectionality of both heavy alcohol consumption and homelessness creates additional barriers to overcoming both homelessness and heavy drinking.

Other participants discussed drinking high quantities of alcohol as a way of coping with the loss of a loved one; experiencing death was often mapped alongside higher levels of alcohol consumption on the life history calendars.

My mum died in 2009 she killed herself, she was an alcoholic and I don’t think I grieved properly for her so I think that is why I drink. (Participant 9)

The death of a parent appeared to have the most impact on the deterioration in living situations for this group of participants. Many discussed experiencing prior adverse life events that could have potentially led to them becoming homeless, but they had been able to rely on the support of a parent, thus highlighting the significance of the role that relationships and human capital have (Granfield & Cloud, Citation2001; White & Cloud, Citation2008). The loss of their parent(s) meant that when further adverse life events occurred they lacked the support they had previously, thus becoming more likely to experience homelessness. Consuming large quantities of alcohol as a means to cope with this loss became a further barrier that then impacted their remaining relationships and often meant that recovery capital from both their alcohol consumption and homelessness was difficult to maintain.

For the Eastern European participants, friendships were critical because they were displaced from their home country and were unlikely to have family in the UK. As these participants had no recourse to public funds (no entitlement to welfare benefits or public housing) they would often sleep rough. Drinking alcohol was an integral part of socialising with other rough sleepers, as well as a means of coping with the pressures of rough sleeping.

When I lived at my sister’s I didn’t drink, then sometimes [when I] lived in hostel. Then working, working, working so then I don’t drink and don’t see friends. Now I am homeless and when I meet friends it’s [makes drinking gesture]. (Participant 10)

Some participants also discussed how the stigma that is often associated with both homelessness and heavy alcohol consumption could also negatively impact family relationships.

I never went to their [brother’s son] weddings because I was a drunk, a drunken bum is the word. I couldn’t go to the wedding, I haven’t got the best clothes… I couldn’t go to a wedding and degrade my brother. (Participant 11)

These findings highlight the complexity of human capital in relation to heavy alcohol consumption, and how this is further complicated by homelessness. For the Eastern European participants as discussed above, alcohol helped them to develop social capital with their peers through the shared drinking practices, whilst this did not enable them to overcome homelessness it did provide them with a means of coping with homelessness. For other participants, the negative and stigmatised association with heavy drinking was further exasperated by the stigma that is also associated with homelessness, which led to a loss of social capital. This is evidence of the nuances that surround heavy drinking, with some people finding it a means of developing and maintaining social capital with others in a similar situation, whereas for others it led to the deterioration and loss of relationships which otherwise may have been the catalyst for recovery capital in terms of reducing their drinking and securing stable accommodation.

Structural – welfare benefits, unemployment, and incarceration

For participants who had access to public funds, benefit sanctions (having welfare payments stopped or reduced for a fixed period due to not meeting the terms of agreement made with the Department for Work and Pensions) played a considerable role in the decline of their living situation and often led to eviction due to rent arrears. The majority of these participants had experienced mental health difficulties (often associated with high levels of drinking), which they felt had contributed to the situation that had led to their benefits becoming sanctioned.

Now I am living here at that [hostel]. I was living in my nice little flat until universal credit stopped my benefits. Then I got sanctioned and then they stopped my rent. (Participant 4)

These sanctions resulted in the participants who had previously engaged in heavy drinking finding it difficult to maintain their recovery. It also contributed to the development of heavy drinking for those who reported low-risk drinking practices previously. Again, this highlights the duality of issues and complexity of experiencing multiple disadvantages that are faced by those who drink high quantities of alcohol and who experience homelessness, as both hinder the potential to achieve recovery capital.

Having no recourse to public funds when faced with unemployment was a major factor for Eastern European participants in particular. Whilst they had been able to pay for accommodation when they had employment, loss of employment, predominantly due to poor health or unintentional injury, resulted in homelessness. These participants went on to discuss how being homeless further impacted their potential to gain employment thus creating a vicious circle and making it difficult to find a way out of homelessness. These participants maintained that they would have reverted to low-risk drink drinking practices had they then secured employment and accommodation and that heavy drinking was a means of coping with homelessness.

I was in a hostel. I broke my ankle and shoulder, I was in hospital for 4 weeks and 4 weeks rehabilitation centre after. I went back to the hostel and [they said] ‘no you don’t have more hostel, you don’t have more benefits, go to street’ on this [gestures to leg] in plaster. (Participant 6)

I don’t know’ what to do if I am going to get a job [whilst homeless]. How are you going to get a job? How will you sleep? How will you transport? Where will you put your bag? You know this is a problem. (Participant 5)

Several of the participants discussed incarceration. Those who had spent time in prison had found the detoxification programmes helped them to address their high levels of alcohol consumption. One participant commented that the support from healthcare staff in prisons was one of the main reasons that they had successfully completed detoxification in prison as opposed to in the community where there was less support. However, these participants also discussed how a lack of support upon their release contributed to their becoming homeless and once again engaging in high-risk drinking practices.

[In prison] they give you Librium, they check you three times a day when they give you Librium and check you’re alright and that you’re not going to start having fits, so yeah I’d say it does help. (Participant 12)

Sometimes I felt sad to leave prison because I knew what I was coming back to…I’d been clean in prison but I walk down the road, the first offy [off-licence] I come to, you start on that, the drink starts first. (Participant 8)

One participant who had spent time in prison also went on to discuss how his criminal record was problematic when it came to finding employment. The only jobs he was able to get involved kitchen work in nightlife venues. This had had a detrimental impact on his recovery and he had subsequently started drinking alcohol again. This in turn had contributed to him losing his job and becoming unable to support himself resulting in homelessness.

I worked as a chef and there’s alcohol there and that’s a trigger…I can’t do most jobs because of my criminal record…but they don’t CRB [criminal records check] you to work in a kitchen. (Participant 9)

This case study provides an example of the detriment caused by social structures that can impact upon recovery capital in terms of both alcohol consumption and homelessness. Whilst employment can lead to further acquisition of economic capital which is a key factor in recovery capital related to homelessness, in this case, it also contributed to the participant drinking large quantities of alcohol, subsequently resulting in their loss of employment and return to homelessness.

Health – physical and mental health

Heavy drinking was both a cause and effect of the physical and mental health issues experienced by the participants. Participants discussed a number of health problems (such as liver cirrhosis) due to the consumption of high quantities of alcohol. However, some participants had also started drinking harmful levels of alcohol following accidents, as a coping strategy to deal with pain. This was evident throughout the LHC, which saw periods of illness or an accident mapped alongside higher levels of alcohol consumption.

I’ve got a broken spine. That’s why I drink, self-medicating. It’s cheaper and sometimes it’s the only way. (Participant 8)

Furthermore, the majority of the participants had self-medicated with alcohol as a means of coping with mental health issues as evidenced by the participants mapping mental illness and increasing alcohol consumption alongside adverse life events. Often this was then followed by a period of homelessness as evidenced through the LHC. Some participants discussed how they started drinking high levels of alcohol because of their children being taken into care. Several participants had also started drinking heavily to cope with depression after the death of a loved one.

The death of my friend, he shot himself and when he died I drank pure vodka, I would drink litres per day. (Participant 11)

I drink more [thinking about her children] I got my kids taken off me. (Participant 3)

This reflects the importance that human capital can have on the development and maintenance of recovery capital. Having responsibility for children and maintaining relationships with family and close friends was often a motivation for these participants to maintain secure accommodation and engage with abstinence or low-risk drinking. The loss of this human capital, often the result of a series of adverse life events, led to a further deterioration of their mental health which subsequently contributed to heavy drinking along with homelessness.

Anxiety and stress were also factors, which led to participants engaging in heavy drinking and had the potential to result in homelessness.

I’d say I have a bit of low self-esteem at the moment so I drink and that makes me more confident to go and speak to people and the anxiety goes but the next day when I’ve got the hangover the anxiety is ten time worse so then I carry on drinking. (Participant 9)

Heavy drinking as a means to cope with mental health disorders resulted in further deterioration with regards to mental health as illustrated in the quotation above. For the participants who referred to using alcohol as a means of coping with their mental health, this was also associated with both the cause and effect of their homelessness. Often this was a result of homelessness or led to homelessness as the combination of mental health disorders and heavy drinking made secure accommodation difficult to maintain. This reflects the duality of issues faced by those that are homeless and who consume high quantities of alcohol with regards to mental health (Queen et al., Citation2017; Tsai et al., Citation2017) and how experiencing both can impact upon recovery capital.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore, the relationship between adverse significant life events, homelessness and alcohol consumption within one UK city, through a recovery capital lens. All of the participants discussed experiencing increasing adverse life events (such as illness or the death of a loved one) that led to a period of instability and subsequent deterioration in their housing situation and an increase in their alcohol consumption. There was often one critical event, such as a breakdown or loss of relationship or loss of employment, which would act as the final catalyst. A lack of recovery capital in this instance meant that the participant did not have support to help ameliorate some of the issues that they were facing. Several participants had faced some similar issues in the past but, because they had support networks and other elements associated with recovery capital in place at the time, this did not lead to homelessness or heavy drinking.

It is also important to note that, for some individuals, detrimental family relations could have also led to a loss of recovery capital, principally with regards to their alcohol use, if these relationships also contributed to anxiety and other factors associated with poor mental health. This has been explored by Neale and Stevenson (Citation2015) in their research into recovery capital with hostel residents who used drugs and found that, in relation to recovery capital, family relationships were often complex and could be both of benefit and detriment to the participants. This was very much reflected through the LHCs in this study, which mapped both ups and downs of the participants’ relationship with their wider family and how this impacted upon their living situation and alcohol consumption thus evidencing the role of human and social capital within wider recovery capital (Cloud & Granfield, Citation2008; White & Cloud, Citation2008).

The loss of a parent emerged as one of the key factors associated with becoming homeless and heavy drinking, as parents would have originally provided crucial support during times of crisis. Furthermore, those who had maintained a good relationship with their parents generally did not experience rough sleeping until later in life compared to those who discussed fragmented relationships earlier in their life course. Research by Brown et al. (Citation2016) in the USA has further demonstrated that breakdown in relationships can affect people differently depending on the point in their life when this breakdown occurs. Again, the LHCs demonstrated how the timing of parental loss would often shape the impact that this had on developing or maintaining recovery capital. If it happened during a period that included other adverse life events then it would be more likely to impact their living situation and level of alcohol consumption.

Participants who identified as Eastern European lacked recovery capital, in some respects, through having no recourse to public funds and no immediate family living nearby that could provide support. This meant that if an adverse life event occurred, such as the loss of employment or a period of ill health, then they often struggled to maintain their accommodation, frequently using alcohol consumption as a coping strategy. This reflected how this population may face additional adversity as a result of multiple exclusionary homelessness (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2012). Interestingly, this group of participants was confident that, should their unemployment situation become resolved, they would subsequently be able to maintain stable accommodation and would drink less alcohol. Whilst these participants lacked social capital with regard to family support, they did maintain social capital with regard to their peer group. Whilst these relationships did sometimes facilitate high-risk drinking as peers would share alcohol and drinking was considered a social activity, they also provided moral support to one another. This particular group of participants did not feel that their drinking was problematic, and felt that if they had a job they would drink less. Consequently, recovery capital was more dependent on the increase of economic elements, as opposed to social elements, and was more related to being homeless than alcohol consumption. This is also an event in research by Anderson et al. (Citation2021) which explored how the role of social bonds within recovery capital and argued that wider networks can have both positive and negative influences on recovery. Additionally, despite not believing their drinking to be an addiction, these participants did report detrimental effects associated with or aggravated by their alcohol consumption, such as a deterioration in their mental health. This again highlights, the importance of considering the intersection between homelessness and heavy alcohol consumption as those experiencing both can experience multiple disadvantages in developing recovery capital.

The intersection between homelessness and heavy drinking further impacted the participants’ recovery capital. Participants discussed how a combination of homelessness and high-risk drinking would make recovery difficult to achieve and maintain and adverse life events could further exacerbate this. They recognised that homelessness made it difficult to overcome their high-risk drinking practices (Brown et al., Citation2016; McQuistion et al., Citation2014; Velasquez et al., Citation2000) which highlights the additional needs of the homeless population. Furthermore, as homelessness and heavy drinking are associated with stigma, those who experience these are often subject to social distance (Phillips, Citation2015; Van Steenberghe et al., Citation2021) which in turn creates further barriers for recovery capital. Research by Best (Citation2016) explored stigma in recovery communities in Blackpool and argued that having a visible and pro-social recovery community in the local area can help to challenge preconceived ideas about those that are in recovery. The example used by Best is social enterprise companies (SECs), which provide jobs for those in recovery as well as further opportunities for these individuals to build social bonds with others who may have had similar lived experiences of adversities. The use SECs can be applied to both those that engage in high-risk drinking and those that are homeless, as both groups are often stigmatised within local communities and SECs provide resources to build upon different elements of recovery capital through facilitating social networks, as well as providing stability and financial support, and challenging negative stereotypes.

What was evident through the analysis of the LHCs was the importance of perceived quality of life in successfully maintaining recovery. This has been highlighted previously in research into recovery from illicit substance use (Laudet & White., Citation2008; Laudet et al., Citation2009; O’Sullivan et al., Citation2019; Van Steenberghe et al., Citation2021). Participants discussed how their perception of stigma was associated with their quality of life, and an improvement in quality of life was considered to be a way of developing recovery capital. This was through both an improvement in their mental health which was important in terms of them reducing their alcohol consumption and the acquisition of economic capital that enabled them to have the physical means of overcoming issues associated with stigma. This was often through having secure accommodation. This has implications for policy, as it demonstrates how issues relating to recovery capital need to be addressed in order for those who are homeless and who drink large quantities of alcohol to achieve sustainable housing, recovery and avoid relapse.

Through the consideration of the operational categories of recovery capital as set out by Best and Laudet (Citation2010), research can continue to map out experiences of individuals who experience multiple adverse life events that result in heavy alcohol consumption and homelessness, as well as other potential health risk behaviours. This would provide those working in policy and practice with a deeper understanding of how services can be structured to support individual needs (Carver et al., Citation2020). Bramley and Fitzpatrick (Citation2018) have argued for a more targeted approach in homelessness prevention services and the authors of this paper support this notion and would content that a focus upon the intersection between recovery capital, homelessness, and health risk behaviours such as heavy drinking is needed.

Problematic concepts relating to the overall notion of recovery capital should also be noted as discourse surrounding recovery is often based on abstinence. In this study, the LHCs highlighted periods of moderate or low-level alcohol consumption and several of the participants stated that they were not addicted to alcohol, rather their alcohol use was a means of coping with their current situation. Interestingly, Laudet et al. (Citation2009) also note that, in relation to illicit substance use, quality of life does not always equate with abstinence. In Canada, there has been some development of services that have introduced managed alcohol programmes that attempt to address the duality of the issues experienced by those who engage in heavy alcohol consumption and who are homeless (Pauly et al., Citation2018; Carver et al., Citation2021). Research into services that support harm reduction approaches as opposed to abstinence-based approaches has demonstrated some success in improving outcomes for those who use these services through the reduction in social harms that are associated with heavy and risky drinking, allowing these individuals to start to develop elements of recovery capital (Henwood et al., Citation2014; Stockwell et al., Citation2018). There is some evidence that supports programmes that encourage safer drinking practices if abstinence is not feasible (Grazioli et al., Citation2015). Additionally, there is limited evidence from the UK that the provision of safe spaces for homeless people to drink can help to lower alcohol consumption in the short term and encourage engagement with support services in the medium to long term (see McCoy et al., Citation2016).

Study limitations

The study does provide conceptual insight into the lived experiences of the twelve participants and, to an extent, these could be used to provide some generic understanding of the impact that adverse life events have on homelessness and high risk drinking. However, it is important to bear in mind that due to the small sample size, whilst many of the experiences discussed by the participants are common across both the UK homeless population and those who engage in heavy alcohol consumption, it is probable that not all potential impacting factors were experienced or discussed by the participants. Moreover, the sample included fewer women compared to men. Whilst this is generally reflective of the overall homeless population within the UK (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, Citation2019), it does mean that this paper is less reflective of the experiences of women who are homeless. As Wincup (Citation2016) and Andersson et al. (Citation2021) have highlighted, it is important to reflect on the different challenges that women can face with regard to recovery capital. Furthermore, due to the method of recruitment, the study only engaged with those in contact with local homelessness services and therefore those who did not engage with such services were not included. As the research team only carried out data collection with those that were considered to be able to give informed consent in line with the criteria set out in the application for ethical approval, participants considered to be too intoxicated were excluded from the study. Additionally, the study and interview questions were designed by researchers who have no lived experiences of homelessness or high-risk drinking. This may mean that they did not elicit the full spectrum of experiences that may have had relevance to the overall research aim.

Conclusion

The research that has been presented in this paper explored relationships between significant life events and alcohol consumption amongst homeless people in a city within the North-West of England. Findings were explored through a recovery capital lens in order to explore the intersection between homelessness and risky drinking practices. The findings demonstrate how homelessness and heavy alcohol consumption should be addressed simultaneously due to the overlap of factors associated with both in relation to a lack of recovery capital. This intersection is an important consideration for policy and practice. When faced with an accumulation of adverse life events, it was often the lack of social support that led to participants becoming homeless and/or developing high-risk drinking practices. In particular, the loss of a loved one, or a breakdown in a relationship, was the catalyst for homelessness as these relationships were key in securing accommodation, especially when the individual in question lacked economic capital. Those who are commissioning and developing services for the homeless and/or individuals who engage in high-risk drinking should consider how resources that enable individuals to increase their recovery capital can be developed and sustained in order to help prevent the cyclical nature of homelessness and/or engaging in risky drinking practices, for example in providing additional support for bereavement or maintaining relationships with children. Future research should consider further the intersection in relation with regards to the different elements of recovery capital as well as consider how services support the development of recovery and capital in order to identify examples of best practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, Collette Venturas and Andrew Bradbury for their assistance with the data collection and Pat Ross for proof reading the manuscript. Special thanks go to all the participants who took part in this study and the services that assisted with recruitment.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 UK Chief Medical Officers low risk drinking guidelines for men and women: no more than 14 units of alcohol a week spread over three or more days.

References

- Aldridge, R. W., Story, A., Hwang, S. W., Nordentoft, M., Luchenski, S. A., Hartwell, G., Tweed, E. J., Lewer, D., Katikireddi, S. V., & Hayward, A. (2018). Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 391(10117), 241–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31869-X

- Anderson, M., Devlin, A. M., Pickering, L., McCann, M., & Wight, D. (2021). ‘It’s not 9 to 5 recovery’: The role of a recovery community in producing social bonds that support recovery. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 28(5), 475–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2021.1933911

- Andersson, C., Wincup, E., Best, D., & Irving, J. (2021). Gender and recovery pathways in the UK. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 28(5), 454–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2020.1852180

- Baggett, T. P., O’Connell, J. J., Singer, D. E., & Rigotti, N. A. (2010). The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: A national study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(7), 1326–1333. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109

- Beatty, C., Foden, M., McCarthy, L., & Reeve, K. (2015). Benefit sanctions and homelessness: A scoping report. Crisis. https://www.crisis.org.uk/media/20568/benefit_sanctions_scoping_report_march2015.pdf

- Beijer, U., Wolf, A., & Fazel, S. (2012) Prevalence of tuberculosis, hepatitis C virus, and HIV in homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 12(11), 859–870. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70177-9

- Best, D., & Laudet, A. (2010). The potential of recovery capital. RSA. https://facesandvoicesofrecovery.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/The-Potential-of-Recovery-Capital.pdf

- Best, D. (2016). An unlikely hero? Challenging stigma through community engagement. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 16(1), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-09-2015-0054

- Best, D., Vanderplasschen, W., & Nisic, M. (2020). Measuring capital in active addiction and recovery: The development of the strengths and barriers recovery scale (SABRS). Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 15(1), 40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-020-00281-7

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. University of Chicago Press.

- Bramley, G., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2018). Homelessness in the UK: Who is most at risk? Housing Studies, 33(1), 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1344957

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [available from http://www.aijcrnet.com/journals/Vol_3_No_3_March_2013/1.pdf] https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, R. T., Goodman, L., Guzman, D., Tieu, L., Ponath, C., & Kushel, M. B. (2016). Pathways to homelessness among older homeless adults: Results from the HOPE HOME study. PLoS One, 11(5), e0155065. [available from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155065]

- Bryman, A. (2015). Social research methods (5th ed). Oxford University Press.

- Burnard, P. (1991). A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Education Today, 11(6), 461–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-6917(91)90009-Y

- Burnard, P., Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., & Chadwick, B. (2008). Analysing and presenting qualitative data. British Dental Journal, 204(8), 429–432. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.292

- Burr, V. (2003). Social constructionism (2nd ed). Routledge.

- Busch-Geertsema, V., Culhane, D., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2016). Developing a global framework for conceptualising and measuring homelessness. Habitat International, 55, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.03.004

- Canavan, R., Barry, M. M., Matanov, A., Barros, H., Gabor, E., Greacen, T., Holcnerová, P., Kluge, U., Nicaise, P., Moskalewicz, J., Díaz-Olalla, J. M., Strassmayr, C., Schene, A. H., Soares, J. J. F., Gaddini, A., & Priebe, S. (2012). Service provision and barriers to care for homeless people with mental health problems across 14 European capital cities. BMC Health Services Research, 12(222), 222. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-222

- Cano, I. M., Best, D., Edwards, M., & Lehman, J. (2017). Recovery capital pathways: Modelling the components of recovery wellbeing. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 181(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.002

- Carver, H., Parkes, T., Browne, T., Matheson, C., & Pauly, B. (2021). Investigating the need for alcohol harm reduction and managed alcohol programs for people experiencing homelessness and alcohol use disorders in Scotland. Drug and Alcohol Review, 40(2), 220–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13178

- Carver, H., Ring, N., Miler, J., & Parkes, T. (2020). What constitutes effective problematic substance use treatment from the perspective of people who are homeless? A systematic review and meta-ethnography. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(1), 10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-0356-9

- Chamberlain, C., & Johnson, G. (2013). Pathways into adult homelessness. Journal of Sociology, 49(1), 60–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783311422458

- Cloud, W., & Granfield, R. (2008). Conceptualizing recovery capital: Expansion of a theoretical construct. Substance Use & Misuse, 43(12–13), 1971–1986. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080802289762

- Department for Communities and Local Government. (2015). Rough Sleeping Statistics England - Autumn 2014 official statistics.

- Department of Health. (2016). UK Chief Medical Officers’ low risk drinking guidelines. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545937/UK_CMOs__report.pdf

- Dwyer, P. J., Scullion, L., Jones, K., & Stewart, A. (2018). The impact of conditionality on the welfare rights of EU migrants in the UK. Policy and Politics, 10, 133–150.

- Fallaize, R., Seale, J., Mortin, C., Armstrong, L., & Lovegrove, J. (2017). Dietary intake, nutritional status and mental wellbeing of homeless adults in Reading, UK. British Journal of Nutrition, 118(9), 707–714. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114517002495

- Fazel, S., Geddes, J. R., & Kushel, M. K. (2014). The health of homeless people in high-income countries: Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical policy recommendations. The Lancet, 384(9953), 1529–1540. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Fazel, S., Khosla, V., Doll, H., & Geddes, J. (2008). The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in Western countries: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Medicine, 5(12), e225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225

- Fikowski, J., Marchand, K., Palis, H., & Oviedo-Joekes, E. (2014). Feasibility of applying the life history calendar in a population of chronic opioid users to identify patterns of drug use and addiction treatment. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 8, 73–78. https://doi.org/10.4137/SART.S19419

- Fitzpatrick, S., Johnsen, S. & Bramley , (2012). Multiple exclusion homelessness amongst migrants in the UK. European Journal of Homelessness, 6(1), 31–58.

- Fountain, J., Howes, S., Marsden, J., Taylor, C., & Strang, J. (2003). Drug and alcohol use and the link with homelessness: Results from a survey of homeless people in London. Addiction Research & Theory, 11(4), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/1606635031000135631

- Fransham, M., & Dorling, D. (2018). Homelessness and public health. BMJ, 360, k214. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k214

- Granfield, R., & Cloud, W. (2001). Social context and “natural recovery”: The role of social capital in the resolution of drug-associated problems. Substance Use & Misuse, 36(11), 1543–1570. 1570. https://doi.org/10.1081/JA-100106963

- Grazioli, V. S., Hicks, J., Kaese, G., Lenert, J., & Collins, S. E. (2015). Safer-drinking strategies used by chronically homeless individuals with alcohol dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 54, 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2015.01.010

- Henwood, B. F., Padgett, D. K., & Tiderington, E. (2014). Provider views of harm reduction versus abstinence policies within homeless services for dually diagnosed adults. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 41(1), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-013-9318-2

- Homeless Link. (2016). Supporting people with no recourse to public funds (NRPF). https://www.homeless.org.uk/sites/default/files/site-attachments/Supporting%20people%20with%20no%20recourse%20to%20public%20funds%20%28NRPF%29%202016.pdf

- Homeless Link. (2017). Counts & estimates toolkit 2017: Introduction and intelligence gathering. https://www.homeless.org.uk/sites/default/files/site-attachments/Counts%20%26%20Estimates%20Introduction%202017.pdf

- IHME. (2019). Global burden of disease. http://www.healthdata.org/gbd/2019

- Ijaz, S., Jackson, J., Thorley, H., Porter, K., Fleming, C., Richards, A., Bonner, A., & Savović, J. (2017). Nutritional deficiencies in homeless persons with problematic drinking: A systematic review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0564-4

- Jones, L., McCoy, E., Bates, G., Bellis, M. A., & Sumnall, H. (2015). Understanding the alcohol harm paradox in order to focus the development of interventions (Final report for Alcohol Research UK). Liverpool John Moores University.

- Kennedy, D. M. (2016). Is it any clearer? Generic qualitative inquiry and the VSAIEEDC model of data analysis. The Qualitative Report, 21(8), 1369–1379. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2444

- Laudet, A. B., & White, W. L. (2008). Recovery capital as prospective predictor of sustained recovery, life satisfaction, and stress among former poly-substance users. Substance Use & Misuse, 43(1), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080701681473

- Laudet, A. B., Becker, J. B., & White, W. L. (2009). Don’t wanna go through that madness no more: Quality of life satisfaction as predictor of sustained remission from illicit drug misuse. Substance Use & Misuse, 44(2), 227–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080802714462

- Mackelprang, J. L., Graves, J. M., & Rivara, F. P. (2014). Homeless in America: Injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2007-2011. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 21(3), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457300.2013.825631

- Manthorpe, J., Cornes, M., O’Halloran, S., & Joly, L. (2015). Multiple exclusion homelessness: The preventive role of social work. British Journal of Social Work, 45(2), 587–599. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct136

- McCoy, E., Oyston, J., Ross-Houle, K., Cochrane, M., Bates, G., Jones, L., Whitfield, M., & McVeigh, J. (2016). Evaluation of the Liverpool rehabilitation, education, support & treatment (REST) centre. Liverpool John Moores University.

- McQuistion, H. L., Gorroochurn, P., Hsu, E., & Caton, C. L. M. (2014). Risk factors associated with recurrent homelessness after a first homeless episode. Community Mental Health Journal, 50(5), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-013-9608-4

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

- Ministry of Housing and Local Government. (2018). Statutory homelessness and prevention and relief, January to March (Q1) 2018: England. Z:/ARUK%20alcohol%20&%20homeless/Statutory_Homelessness%202018.pdf

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. (2019). Statutory homelessness, July to September (Q3) 2018: England. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/804055/Statutory_Homelessness_Statistical_Release_July_to_September_2018.pdf

- Neale, J., & Stevenson, C. (2015). Social and recovery capital amongst homeless hostel residents who use drugs and alcohol. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 26(5), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.09.012

- Nico, M. L. (2016). Bringing life “back into life course research”: Using the life grid as a research instrument in qualitative data collection and analysis. Quality and Quantity, 50(5), 2107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0253-6

- O’Sullivan, D., Xiao, Y., & Watts, J. R. (2019). Recovery capital and quality if life in stable recovery from addiction. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 62(4), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355217730395

- Padgett, D. K., Henwood, B., Abrams, C., & Drake, R. E. (2008). Social relationships among persons who have experienced serious mental illness, substance abuse, and homelessness: Implications for recovery. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(3), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014155

- Paisi, M., Kay, E., Plessas, A., Burns, L., Quinn, C., Brennan, N., & White, S. (2019). Barriers and enablers to accessing dental services for people experiencing homelessness: A systematic review. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 47(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12444

- Paquette, K., & Winn, L. A. P. (2016). The role of recovery housing: Prioritizing choice in homeless services. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 12(2), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2016.1175262

- Parkes, T., Matheson, C., Carver, H., Budd, J., Liddell, D., Wallace, J., Pauly, B., Fotopoulou, M., Burley, A., Anderson, I., MacLennan, G., & Foster, R. (2019). Supporting Harm Reduction through Peer Support (SHARPS): Testing the feasibility and acceptability of a peer-delivered, relational intervention for people with problem substance use who are homeless, to improve health outcomes, quality of life and social functioning and reduce harms: Study protocol. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 5, 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0447-0

- Pauly, B., Vallance, K., Wettlaufer, A., Chow, C., Brown, R., Evans, J., Gray, B., Krysowaty, B., Ivsins, A., Schiff, R., & Stockwell, T. (2018). Community managed alcohol programs in Canada: Overview of key dimensions and implementation. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37(S1), S132–S139. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12681

- Percy, W. H., Kostere, K., & Kostere, S. (2015). Generic qualitative research in psychology. The Qualitative Report, 20(2), 76–85.

- Phillips, L. (2015). Homelessness: Perception of causes and solutions. Journal of Poverty, 19(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2014.951981

- Porcellato, L., Carmichael, F., & Hulme, C. T. (2014). Using occupational history calendars to capture lengthy and complex working lives: A mixed method approach with older people. International Journal of Social Research Methods, 19(3), 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2014.988005

- Public Health England. (2016). The public health burden of alcohol and the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies: An evidence review. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/733108/alcohol_public_health_burden_evidence_review_update_2018.pdf

- Public Health England. (2018). Public health dashboard. https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/public-health-dashboard-ft#page/11/gid/1938133154/pat/6/par/E12000006/ati/102/are/E10000015/iid/93011/age/168/sex/4

- Public Health England. (2019). Estimates of alcohol dependent adults in England. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/alcohol-dependence-prevalence-in-england

- Queen, A. B., Lowrie, R., Richardson, J., & Williamson, A. E. (2017). Multimorbidity, disadvantage, and patient engagement within a specialist homeless health service in the UK: An in-depth study of general practice data. BJGP Open, 1(3), 100941. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen17X100941

- Reeve, K. (2017). Welfare conditionality, benefit sanctions and homelessness in the UK: Ending the ‘something for nothing culture’ or punishing the poor? Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, 25(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1332/175982717X14842281240539

- Rehm, J., Guiraud, J., Poulnais, R., & Shield, K. D. (2018). Alcohol dependence and very high risk level of alcohol consumption: A life-threatening and debilitating disease. Addiction Biology, 23(4), 961–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12646

- Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2019). Alcohol consumption. https://ourworldindata.org/alcohol-consumption

- Roca, P., Panadero, S., Rodríguez-Moreno, S., Martín, R. M., & Vázquez, J. J. (2019). The revolving door to homelessness. The influence of health, alcohol consumption and stressful life events on the number of episodes of homelessness. Anales de Psicología, 35(2), 175–180. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.35.2.297741

- Room, R., Babor, T., & Rehm, J. (2005). Alcohol and public health. The Lancet, 365(9458), 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17870-2

- Shinn, M. (2007). International homelessness: Policy, socio-cultural, and individual perspectives. Journal of Social Issues, 63(3), 657–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00529.x

- Smith, A. (2015). Can we compare homelessness across the Atlantic? A comparative study of methods for measuring homelessness in North America and Europe. European Journal of Homelessness, 9(2), 233–257.

- Smith, L. J. (2008). How ethical is ethical research? Recruiting marginalized, vulnerable groups into health services research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(2), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04567.x

- Sprake, E. F., Russell, J. M., & Barker, M. E. (2014). Food choice and nutrient intake amongst homeless people. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 27(3), 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12130

- Stockwell, T., Pauly, B., Chow, C., Erickson, R. A., Krysowaty, B., Roemer, A., Vallance, K., Wettlaufer, A., & Zhao, J. (2018). Does managing the consumption of people with sever alcohol dependence reduce harm? A comparison of participants in six Canadian managed alcohol programs with locally recruited controls. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37(S1), S159–S166. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12618

- Thomas, B. (2012). Homelessness kills: An analysis of the mortality of homeless people in early twenty-first century England. Crisis. https://www.crisis.org.uk/media/236799/crisis_homelessness_kills_es2012.pdf

- Topolovec-Vranic, J., Ennis, N., Colantonio, A., Cusimano, M. D., Hwang, S. W., Kontos, P., Ouchterlony, D., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2012). Traumatic brain injury among people who are homeless: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 12, 1059. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-1059

- Tsai, J., O’Toole, T., & Kearney, L. K. (2017). Homelessness as a public mental health and social problem: New knowledge and solutions. Psychological Services, 14(2), 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000164

- Tunstall, R., Bevan, M., Bradshaw, J., Croucher, K., Duffy, S., Hunter, C., Jones, A., Rugg, J., Wallace, A., & Wilcox, S. (2013). The links between housing and poverty: An evidence review. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Van Steenberghe, T., Vanderplasschen, W., Bellaert, L., & De Maeyer, J. (2021). Photovoicing interconnected sources of recovery capital of women with a drug use history. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 28(5), 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2021.1931033

- Velasquez, M. M., Crouch, C., Von Sternberg, K., & Grosdanis, I. (2000). Motivation for change and psychological distress in homeless substance users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 19(4), 395–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(00)00133-1

- White, W., & Cloud, W. (2008). Recovery capital: A primer for addictions professionals. Counselor, 9(5), 22–27.

- Wincup, E. (2016). Gender, recovery and contemporary UK drug policy. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 16(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-08-2015-0048