Abstract

Minimum unit pricing for alcohol (MUP) came into effect on 1st May 2018 in Scotland, raising the price of the cheapest shop-bought alcohol. Small retailers are a key source of alcohol for communities, often located in areas of high alcohol-related harm. We sought to examine their experiences of MUP implementation and impact. We conducted semi-structured interviews in-store with 20 small retailers in central Scotland at two time points: October – November 2017 (6–7 months pre-implementation); and October – November 2018 (5–6 months post-implementation). Prior to implementation, some retailers did not understand MUP, including how prices would link to product strength, or were concerned about anticipated implementation burden. Several expressed support for reducing ‘problem’ drinking or suggested that MUP would increase alcohol prices in supermarkets bringing them into line with small retailers. Despite initial concerns, small retailers reported minimal disruption following implementation of MUP, which was generally straightforward. Compliance was taken seriously and price calculations relatively manageable. Few/no negative reactions from customers were reported. Some felt that the measure enabled them to better compete with larger retailers/supermarkets. Concerns about MUP expressed by some trade bodies prior to implementation were largely not borne out in the experiences of small retailers.

Introduction

On 1st May 2018, Scotland became the first country in the European Union to set a Minimum Unit Price (MUP) for alcohol, mandating that all drinks containing alcohol must have a minimum sales price of £0.50-per-unit of alcohol (Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act, Citation2012). (A UK unit is equivalent to 10 ml or 8 g of pure alcohol; £0.50-per-unit is therefore approximately €0.74 per 10 g of pure alcohol or $1.21 per US standard drink). Prospective modelling estimated that the policy would lead to 400 fewer alcohol-related deaths and 8,000 fewer alcohol-related hospital admissions over its first five years (Angus et al., Citation2016). A key feature of the MUP legislation is the inclusion of a ‘sunset clause’ meaning that the legislation will cease to exist beyond its sixth year unless the Scottish Parliament vote for it to continue. This decision will be informed by research evidence including several studies commissioned by NHS Health Scotland (now Public Health Scotland) which collectively aim to generate evidence on the outcomes in the theory of change (Public Health Scotland, Citation2021). Wales subsequently introduced MUP in March 2020 (Public Health (Minimum Price for Alcohol) (Wales) Act, Citation2018), and it was implemented in the Republic of Ireland in January 2022 (Public Health (Alcohol) Act 2018 (Commencement) Order, Citation2021). Experiences of novel policies in early-adopter countries are important for informing debate, decision-making and implementation strategies in other countries, as well as informing the sunset clause vote in Scotland.

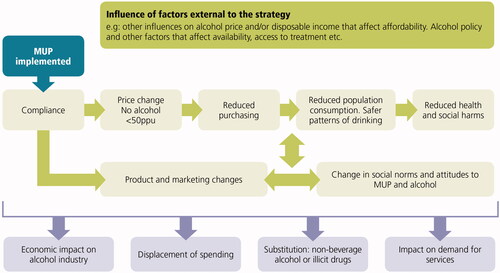

The main expected chain of outcomes from the policy were identified in a Theory of Change prepared by the national public health agency in Scotland () (Beeston et al., Citation2020). This theory posited that compliance (i.e. correct implementation by alcohol retailers) would result in an increase in the price of low cost, high strength alcohol, translating into reductions in alcohol purchasing and consumption which in turn would reduce alcohol-related harms (Beeston et al., Citation2020). For any policy to produce the intended public health benefits, it must be implemented as intended by those in the frontline. A key part of the MUP chain is the small retail sector. Small retailers comprise small owner-operated businesses which typically also sell groceries and confectionery, usually comprising a single store or small number of stores owned and operated by an individual or family. In the UK such stores can be affiliated to a ‘symbol group’ (e.g. Nisa, Premier, and Best-One) or independent (also known as non-affiliated).

Figure 1. Theory of Change for minimum unit pricing for alcohol. (Figure from Beeston et al., Evaluation of Minimum Unit Pricing of Alcohol: A Mixed Method Natural Experiment in Scotland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103394).

It is important to examine MUP implementation in this sector for several reasons. Firstly, small retailers are an important source of alcohol for local communities. There are around 5,000 such stores in Scotland1 and collectively they account for around 22% of alcohol sales in the UK (Euromonitor International, Citation2021). They are often located in areas of deprivation which experience higher levels of alcohol-related harm (Shortt et al., Citation2018) and where lower disposable incomes means some customers display higher levels of price sensitivity (Gill et al., Citation2015). People with high levels of alcohol dependence disproportionately purchase alcohol from small retailers compared with other retail outlets (Gill et al., Citation2015). As a key part of the local community retail environment, small shops are potentially important in shaping wider norms and expectations around health behaviours (e.g. Daly & Allen, Citation2018; Sandín Vázquez et al., Citation2019). Secondly, small retailers often have different alcohol product ranges from supermarkets, and tend to sell products not available in larger stores. For example, Buckfast tonic wine and strong and high-volume white ciders such as Frosty Jack's, which were frequently cited in media debate about the need for, and likely impact of, MUP (e.g. Allardyce, Citation2018; Ferguson & Madeley, Citation2018; Ikonen, Citation2018; Rose, Citation2017), tend to be only available through small retailers and are disproportionately consumed by dependent drinkers (see citations above). Thirdly, small retailers often have more autonomy than larger retailers, where centralised and automated systems are in place to manage product range and pricing; this may introduce variability into small retailers’ implementation of and compliance with new regulations, and highlights the importance of examining how such stores interpret and implement them (e.g. Eadie et al., Citation2016; Stead et al., Citation2020b). Most of the published research into small retailers’ implementation of alcohol restrictions has focused on regulations prohibiting under-age sales and retailers’ response to interventions to increase compliance with these regulations, such as test purchasing (e.g. Forsyth et al., Citation2014; Van Hoof et al., Citation2012). The only prior published research into retailers’ implementation of a floor-price intervention such as MUP is in Canada, where forms of minimum pricing have been in place for some years, albeit with considerable variety in level and coverage across different jurisdictions (Thompson et al., Citation2017).

Another important reason to examine experiences of implementation in the small retail sector is that there had been predictions in retail trade publications (print and online magazines targeted at retailers) prior to the implementation of MUP that the policy would be harmful to small retail businesses. Articles warned that customers might react negatively to price increases and retailers would no longer being able to offer price promotions below the minimum unit price (e.g. McNee, Citation2018; Retail Newsagent, Citation2017). Small retailers in Scotland are already subject to a number of other alcohol controls, including licensing requirements and a ban on ‘irresponsible’ price promotions (Scottish Government, Citation2013), and MUP represented another substantial change. For all these reasons, it was important to examine whether the policy was able to be implemented as intended in this sector, how retailers perceived its impact, and to identify any implications for other jurisdictions considering introducing MUP, as well as potential future modifications to the policy in Scotland.

Here we report on our interview study of small retailers’ perceptions and experiences of the implementation of MUP, which forms part of a larger study examining implementation and impact of the policy in the small retail sector (Stead et al., Citation2020a).

Methods

We conducted in-store semi-structured interviews with a target sample of 20 small retailers at two time points: Wave 1 October – November 2017 (6–7 months pre-implementation) and Wave 2 October – November 2018 (5–6 months post-implementation). This report meets the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (O’Brien et al., Citation2014).

Sample and recruitment

Small retailers were defined as small owner-operated businesses, usually comprising a single store or small number of stores run by an individual or family. Smaller satellite stores that formed part of large supermarket chains (e.g. Tesco Metro) were excluded. Twenty-four small retailers were recruited at Wave 1 to ensure a minimum sample of 20 at both stages. Three were excluded from the sample at Wave 2 because of a change of status which might have affected their implementation of MUP or alcohol product range (e.g. a new owner), and one was unavailable within the fieldwork period.

The sample was purposively selected from central Scotland, which contains the majority of the Scottish population, to represent a range of store types, affiliated and non-affiliated stores and levels of deprivation using Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) scores for store postcodes (ZIP codes). Stores were identified using online databases such as Google Maps and then visited in person to explain the study, to assess willingness to participate and to determine whether the business met four eligibility criteria using a structured protocol: shop ownership (operated premises for at least 12 months); licence status (was displaying and licensed to sell alcohol); future business intentions (was not planning to make major changes over the study period); and whether the prospective interviewee had responsibility for day-to-day stock decisions. Thirty four stores were approached, of which 24 agreed to participate in the study. Reasons for non-recruitment included refusal, lack of time, and the business owner being unavailable at the time of the initial store visit. Eligible and interested retailers were given an information sheet and then re-contacted to provide written consent and schedule a time for interview as appropriate. A financial incentive (30 GBP) was offered at each wave for participation.

Procedure and data collection

At each wave, semi-structured interviews were conducted in-store during business hours. Interviews lasted 20–30 minutes and were audio-recorded with consent by DE, MS, RP and JM. All interviewers were experienced qualitative researchers, practised in recruiting and interviewing retailers for academic research. The interview and recording were paused during customer transactions as appropriate. The interviews examined retailers’ understanding, expectations and experiences of MUP, pre-and post-implementation. Questions were framed to reflect the two time points. For example, the pre-implementation interviews explored retailers’ awareness (if any) of MUP; their understanding of its basis and purpose; their expectations of which products would be affected and how they would calculate new prices; and how they anticipated that the business might be affected. The post-implementation interviews focused on experiences of the implementation process, including how and when retailers adjusted their prices; any guidance received from different sources; any facilitators or barriers to implementation; any experience of compliance checks; perceptions of the impact of MUP on sales and profits; and perceptions of customer response.

Analysis

All interview recordings were transcribed verbatim for thematic analysis using QSR NVivo12 software. All stores and participants were assigned a non-identifiable code to retain anonymity and all interview transcripts were anonymised. DE and MS read a sample of the Wave 1 transcripts and developed an initial coding framework using deductive and inductive approaches. The coding framework was then piloted on a sample of transcripts by DE, MS, JM and RP to assess reliability and any interpretative differences resolved through discussion before all the data were coded. At Wave 2, the coding framework was revised and expanded. Where comparison between waves was important (for example, regarding attitudes towards MUP or pricing strategy), original codes were retained, with new codes and sub-codes added as required to reflect the themes emerging from the Wave 2 data.

Ethical approval for the retailer interviews was provided by the General University Ethics Panel (GUEP) at the University of Stirling.

Findings

We report the findings under the following themes: understanding of and attitudes towards MUP, implementation, compliance, and perceptions of impact. Findings are supported using illustrative quotes identifying affiliation status (affiliated or non-affiliated), whether the store is located in an area of higher or lower deprivation (SIMD 1–2: higher; SIMD 3–5: lower) and when the interview was conducted (Wave 1 or Wave 2).

Understanding of and attitudes towards MUP

Prior to implementation, retailers had varying levels of awareness and knowledge of MUP. Some confused it with a rise in taxation or a recent ban on multi-buy promotions (Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Act, Citation2010), while others understood correctly that it was a measure to increase prices; however, they did not necessarily grasp that the price rise would be linked to product strength. It was apparent that some initially had limited awareness of the number of units of alcohol in specific products and even of the general concept of units, describing how MUP had made them consider alcohol units for the first time: ‘Never [thought about units before]. I was shocked, you’re like, 23 units!’ (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 1-2, Wave 2).

Some initial concerns were expressed regarding the anticipated burden involved in making changes and that it could have an adverse effect on sales in both alcohol and other categories:

Nothing is positive about it, aye.

Do you think it could have any positive consequences as a business?

No, definitely not…it will stop people buying it, nobody is going to buy that, just talking about [Frosty Jack’s] but nobody is going to buy that for £7.00 or £8.00 per bottle. It will have a knock on effect won’t it, on the rest of the groceries. (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 1-2, Wave 1)

There was uncertainty at Wave 1 regarding the point in the supply chain at which MUP would apply, with questions regarding whether wholesaler and manufacturer prices would rise accordingly, and how and where margins would be affected:

I don’t even know how the cash and carry pricing structure will work. I mean obviously they’re going to raise their prices, manufacturers are going to raise their prices. I take it there’s just going to be more tax on it is there?… I mean where does the extra money go to? Certainly we’re going to make the same margin, whether we make 20%, 30%, which is what we run on roughly, you know? But cash and carries run on about 5%, 10% they say, so I mean surely the manufacturer is not going to benefit from it, so I don’t know. (Non-affiliated retailer, SIMD 1-2, Wave 1)

However, this was a minority view: several retailers believed that the impact would probably not be substantial because only a minority of products and customers would be affected, and some were supportive of, or at least not opposed to, the perceived public health goal of reducing problem drinking: ‘I know that there’s always been an issue with people in Scotland consuming too much alcohol. It’s probably changing the culture of that.’ (Non-affiliated retailer, SIMD 3-5, Wave 1). Further, there was a perception among some that MUP was a necessary corrective to a trend of increasing alcohol affordability – essentially returning alcohol products to a more realistic price:

I remember years ago a bottle of vodka was quite expensive. Instead of going up it’s …came [sic] down.…that’s because supermarkets have forced the prices down. (Non-affiliated retailer, SIMD 3-5, Wave 1)

Implementation

Implementation of MUP was generally described by retailers as straightforward. Any prior concerns about the burden of implementation or impact on business had generally abated by Wave 2, as retailers realised that much of their stock was unaffected: ‘It was fine. Because we went through everything, there was only maybe half a dozen, a dozen prices that we had to change’ (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 3-5, Wave 2).

Around two-thirds of our sample were affiliated to a symbol group. For some of these affiliated retailers, MUP price adjustments were calculated centrally by the symbol group and the retailers’ till software was updated for them with the new prices, meaning that there was no requirement for them to work it out or implement it themselves. Other affiliated retailers calculated and set their own prices, sometimes drawing on pricing advice, price lists or suggested recommended prices provided by the symbol group. Although this task could take some time, it was felt to be relatively manageable once they had worked out the formula and set up systems for checking the stock.

Non-affiliated retailers, around a third of our sample, had to prepare for and implement MUP themselves. However, these were sometimes quite small stores with a limited alcohol range, meaning that the work involved was not too burdensome, particularly as the £0.50 per unit level meant calculations were relatively straightforward.

We had to make a plan up…how they [staff] would work it out, how they’d calculate the price of the bottle and make sure everything…everyone knows how it works. … it was just an inconvenience. (Non-affiliated retailer, SIMD 1-2, Wave 2)

The task of checking and adjusting any below-MUP prices was facilitated by the £0.50 per unit level, making the calculation of minimum unit price relatively simple: ‘See, the thing is that, it’s easy. … 2.8 unit in a can, so we divide it by two, so we can’t sell it below then £1.40.’ (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 1-2, Wave 2)

In some cases retailers received external help. Instances were described of wholesalers sending ‘countdown emails’ (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 1-2, Wave 2) and a leaflet on ‘how to do the [price] conversion’ (Non-affiliated retailer, SIMD 3-5, Wave 2), and of local licensing officers visiting stores to advise on how to deal with price-marked stock:

High Commissioner [a price-marked whisky] for example… £14.99, but it ought to be £15.00 so it was [out by] by one pence. So, I asked him [licensing officer] and he [said] ‘it has to be [fifteen]’ … I had to cover it with masking tape. (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 1-2, Wave 2)

Retailers generally changed prices close to the MUP deadline, although a few introduced some price changes earlier, to familiarise customers with the new prices. Apart from calculating prices, the main challenge was to avoid being left with stock which they could not sell after MUP. This could be because the product would go out of date before it could be sold at the less attractive higher price, or because the price increase would be so dramatic that the product could not be sold at all. In some cases, this message was underlined by licensing officers:

They came round to basically advise us, … do not bulk buy at the wholesalers, and wholesalers had notices up as well saying they were doing no returns. (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 1-2, Wave 2)

Despite efforts to ‘run down’ such stock in the weeks prior to the deadline, some retailers were nonetheless left with products which they could neither return to the wholesalers nor sell: ‘Cider, two cases. … try and get rid of them and we can’t’ (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 1-2, Wave 2).

Retailers generally did not make significant changes to their wider alcohol pricing strategies. A small number suggested that they had taken the opportunity of MUP to increase prices for some other lines of alcohol not affected by MUP, but doing so did not appear to be widespread. Changes to product range were generally reported to be limited, the most common being delisting a small number of product lines which retailers felt were no longer realistic sellers at their new higher price points:

We delisted the larger [strong cider bottles], I think the notorious Frosty Jack [sic], which is a three litre bottle, we delisted that immediately. We still carry the one litre bottle. It ticks along…but there's only one customer that buys that. (Non-affiliated retailer, SIMD 3-5, Wave 2)

Compliance

Retailers described divergent experiences in terms of being assessed for compliance after the MUP implementation deadline. Several retailers had not had any experience of having been knowingly inspected, while others had been inspected by licensing officers to check that their prices were not below MUP. The inspections appeared to vary in scope and intensity, ranging from a selective inspection of certain product prices to a more thorough assessment of the full product range.

They usually go for more ciders. They come in, scan it and see how much it’s going for. Or they just ask you, ‘how much are you selling that for?’ – try to catch you out. (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 3-5, Wave 2)

Actually the council licence authority came round to check… the prices and everything, yeah, unit pricing. Every product. (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 1-2, Wave 2)

Generally retailers took compliance seriously. Most perceived that the consequences of non-compliance – fines or loss of licence – were serious, and stated that they ‘wouldn’t take the risk’ (Non-affiliated retailer, SIMD 3-5, Wave 2); furthermore, any retailer who gained a reputation for selling below MUP could attract trouble from customers: ‘[If] you sell somebody one thing cheap, word goes around and then you’ve got other people harassing you for it’ (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 1-2, Wave 2). However, some retailers speculated or insinuated that selling below MUP could be taking place among other retailers, or commented that they had heard about it from customers (the research was not able to verify these comments). Retailers who described knowing of such practices generally distanced themselves from them, although one did admit to engaging in similar activity. This particular retailer explained how he sometimes sold Frosty Jack’s cider below MUP to regular customers, his rationale being that this was a service solely for good customers who were also ‘friends’. This was the only first-hand instance of intentional non-compliance spoken about by any of the sample.

Perceptions of impact on customer interactions, sales and profits

Despite some initial concerns that customers might argue with retailers about MUP price rises, few described any problems. None of the retailers perceived that there had been an increase in shoplifting of alcohol since the introduction of MUP. However, one retailer cited a perceived increase in the theft of confectionery which might be linked to MUP, as some customers now had less to spend on other products.

Retailers reported a range of perceptions of the impact of MUP on overall alcohol sales, with views varying dependent on which product categories were discussed and the retailer’s local context. Some felt that sales had declined as a result of MUP, particularly of high strength cider which had ‘plummeted’ (Non-affiliated retailer, SIMD 3-5, Wave 2), some that there had been little change, and some that their alcohol sales had increased: ‘Business on the whole, terrific. And alcohol…the last time I checked was up about 20 per cent since the new legislation.’ (Affiliated retailer, SIMD 3-5, Wave 2). However, it was noted by some retailers that it was difficult to distinguish the impact of MUP from other contextual factors which might also have impacted alcohol sales, such as changing customer trends, the long dry summer of 2018 and the football World Cup.

Despite, in some cases, a perceived decline in volume sales, there was a perception that profit margins had improved as a result of MUP, particularly in high strength ciders and in spirits, where retailers were now able to make £2 to £3 profit on larger bottles rather than selling them at close to cost price:

In terms of the actual products sold, there was a decrease in turnover. So, what I lost in turnover, I probably made in margin … Cider, obviously, has reduced significantly, but the margins have increased dramatically. (Non-affiliated retailer, SIMD 3-5, Wave 2)

Several retailers welcomed how MUP had limited supermarkets’ ability to heavily discount alcohol, and this had been ‘beneficial for us, because… [local supermarket] will not be able to do the deals they were doing before.’ (Non-affiliated retailer, SIMD 3-5, Wave 2). Retailers felt that, now that price differentials between local stores and supermarkets had narrowed following MUP implementation, customers might be less inclined to travel to supermarkets, preferring the convenience of buying alcohol locally.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that MUP was implemented as intended in the small retail sector. Retailers understood what was required, found that implementation was largely straightforward, and took compliance seriously. Few adverse effects were reported, and some felt that MUP had improved their ability to compete with supermarkets.

That MUP was straightforward for retailers to implement is supported by other MUP research in Scotland. A study of licensing officers’ perspectives reported high levels of compliance across the off-trade sector (shops selling alcohol for consumption off the premises), and found that, contrary to some expectations, there were no more instances of non-compliance in smaller shops than in larger shops (Dickie et al., Citation2019). The high levels of compliance found in this study are also consistent with those reported from studies of price data, including robust electronic point of sale data monitoring the prices of alcoholic drinks sold in retail outlets in Scotland before and after MUP was implemented (Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Stead et al., Citation2020a).

Several factors have been identified as factors facilitating implementation of MUP (Dickie et al., Citation2019). These include the mandatory status of MUP (compliance is a condition of a store’s alcohol licence), the fact that only a small proportion of products were affected, and the perceived beneficial impact on income. Research into small retailers’ implementation of other regulations designed to protect public health – such as bans on retail point of sale display and promotion of tobacco, introduction of standardised packaging, and restrictions on the display and promotion of high fat, salt and sugar products – has reported similarly high compliance (Eadie et al., Citation2016; Scheffels & Lavik, Citation2013; Stead et al., Citation2020b; Usidame et al., Citation2020). Studies have found that despite initial concerns about the time and costs of implementing changes, small retailers are able to adapt to new legal requirements, even where these are more burdensome than MUP (for example, requiring substantial changes to product ranges or store layout (Stead et al., Citation2020b).

Small retailers often report that anticipated negative consequences of implementing public health-related regulations do not transpire (Haw et al., Citation2020), and even that there are sometimes unanticipated benefits of implementing new public health regulations: for example, small retailers in Scotland reported that the introduction of tobacco standardised packaging resulted in a reduction in product range, which simplified stock control (Purves et al., Citation2019). This is in contrast to articles in the retail trade press, which tend to argue, prior to implementation, that new public health regulations for retailers will be difficult to implement and will harm businesses (Hastings et al., Citation2008; Pettigrew et al., Citation2018; Thompson et al., Citation2021). In the current study, some retailers perceived that, far from harming their business, MUP had improved their ability to compete with supermarkets and increased their profit margins on some alcohol products, and this had to some extent compensated for any decreases in sales volumes. We did not examine actual impacts on purchasing, sales or profits in this study, as these have been investigated in other studies (e.g. Robinson et al., Citation2021; Xhurxhi, Citation2020).

A number of implications for research and policy emerge from the study. Any evaluation of public health measures which involve modification to retail practices should include examination of retailers’ perspectives and experiences. Such research can assess whether retailers understand what is required and whether measures are implemented as intended, and can identify information and support needs to facilitate ongoing implementation. Furthermore, obtaining evidence directly from retailers on the burden and effects of implementation means that policymakers hear from a diversity of actors in the alcohol industry, and not simply from those alcohol producers who are opposed to the policy. The findings here support the view that the alcohol industry is not monolithic, and has a multiplicity of interests and perspectives on given policy issues (Hilton et al., Citation2020; Holden et al., Citation2012). It is important to note that trade bodies may be primarily funded by larger retailers or by alcohol producers and may therefore oppose minimum unit pricing as it would affect their sales, even if it might benefit bars or smaller retailers. Smaller retailers and policy stakeholders should be mindful of these conflicting interests in trade associations that represent a diverse industry (Fitzgerald et al., Citation2022). In terms of future MUP policy, the findings here suggest that, building on this experience, Scottish retailers would be able to adjust to any modifications to MUP which might be required in future. However, it should be noted that the current £0.50 per unit level made price calculations relatively straightforward for retailers who had to adjust prices themselves, and also meant that only a minority of products were affected. More support may be helpful if a future price per unit entailed more complex calculations and applied to a greater proportion of products.

Study strengths include the first-hand insight into retailer experiences, which complement other research into licensing officers’ perspectives on compliance (Dickie et al., Citation2019), and the longitudinal element, which enabled us to see how retailers’ views evolved after implementation; this also enabled us to build an element of trust with retailers which encouraged openness about issues such as compliance and enforcement. Conducting interviews in-store meant that the setting could be used as a prompt to encourage retailers to reflect on what had changed, and facilitated greater understanding of the retail context. Limitations include the small sample size, meaning that the findings may not be generalisable to shops in other areas of Scotland or to other countries. While it is possible that retailers with lower levels of compliance may have been less likely to take part in the study, similar findings from other empirical data sources (e.g. Dickie et al., Citation2019; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Stead et al., Citation2020a) give us confidence that our interviews provide a valid indication of compliance among small retailers. We focused on only one sector of the retail environment (small shops), as it was anticipated that this sector may experience more difficulties with or variability in implementation; however, this meant that we did not examine implementation by larger retailers and supermarkets. The study was not designed to examine impact on sales and did not collect sales data, as this was being examined elsewhere. Retailers’ own perceptions of the impact of MUP on sales and profits may not be reliable; nonetheless, they are important, as positive perceptions may foster willingness to comply with any modifications to MUP in future.

Conclusions

Small retailers reported straightforward, and in some cases positive, experiences of implementing minimum unit pricing for alcohol in Scotland. Implementation was helped by the ease of calculating the minimum price (at 50p per UK unit), and in some cases by support from retail groups or local government-employed licensing standards officers who visited premises. The latter also conducted compliance checks. Retailers experienced few/no negative reactions from customers and some felt that the measure would enable them to better compete with larger retailers/supermarkets who could no longer heavily discount alcohol products. Their experiences contrast with public opposition to the measure from some trade bodies in advance of implementation, whose claims of several likely negative impacts are not borne out by these findings. This adds to other studies finding that negative predictions about the business impact of public health measures do not come to pass, and suggests that a degree of future skepticism about such claims, and the motivation for such claims, is merited.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all our retailer interviewees who gave up their time to participate and share their experiences with us. The authors thank our colleagues Anne Marie MacKintosh, Heather Mitchell and Colin Sumpter for their work on the wider project, and Aileen Paton for assistance with project administration. The authors also thank the following for contributing to the reported research: NHS Health Scotland for guidance and advice throughout the project; members of the MUP Economic Impact and Price Evaluation Advisory Group for providing advice and information; and members of the MUP Evaluation Collaborative for advice and comments.

Disclosure statement

Members of the MUP Economic Impact and Price Evaluation Advisory Group provided comment on the draft of the report from the larger study (but not on this manuscript). All comments were advisory only. Decision making on the research design, investigation, analyses, and content of the study and the final report rested with the research team. Membership of the Evaluation Advisory Groups can be found on the MUP evaluation website2. CA has previously received research funding related to commissioned research from Systembolaget and Alko, the Swedish and Finnish government-owned alcohol retail monopolies. None of the other authors have received any funding from the alcoholic drinks industry, alcohol retailers, or affiliated bodies. NC is a member of the Board of Alcohol Focus Scotland. CA sits on an alcohol policy expert committee for the Department of Health in Ireland. NF sits on alcohol policy expert committees for the Department of Health in Ireland and Public Health Scotland, and served as President of the International Confederation of Alcohol, tobacco and other drug Research Associations (ICARA) from 2018-2020. The authors report there are no further competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Unpublished analysis by CA of 2015 alcohol market data from CGA Strategy. Source data are described here https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14040406.

References

- Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act. (2012). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2012/4/contents/enacted

- Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Act. (2010). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2010/18/contents

- Allardyce, J. (2018). Make drinkers pay to pump up volume'; Group says charging more for drinks with a higher percentage of alcohol such as Buckfast would be more effective than 50p plan. The Sunday Times

- Angus, C., Holmes, J., Pryce, R., Meier, P., & Brennan, A. (2016). Model-based appraisal of the comparative impact of Minimum Unit Pricing and taxation policies in Scotland: An adaptation of the Sheffield Alcohol Policy Model version 3. ScHARR, University of Sheffield. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/media/13073/download?attachment

- Beeston, C., Robinson, M., Giles, L., Dickie, E., Ford, J., MacPherson, M., McAdams, R., Mellor, R., Shipton, D., & Craig, N. (2020). Evaluation of minimum unit pricing of alcohol: A mixed method natural experiment in Scotland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103394

- Daly, S., & Allen, J. (2018). Healthy High Streets: Good place-making in an urban setting. Public Health England & Institute of Health Equity. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/699295/26.01.18_Healthy_High_Streets_Full_Report_Final_version_3.pdf

- Dickie, E., Mellor, R., Myers, F., & Beeston, C. (2019). Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) Evaluation: Compliance (licensing) study. NHS Health Scotland. http://www.healthscotland.scot/media/2660/minimum-unit-pricing-for-alcohol-evaluation-compliance-study-english-july2019.pdf

- Eadie, D., Stead, M., MacKintosh, A. M., Murray, S., Best, C., Pearce, J., Tisch, C., van der Sluijs, W., Amos, A., MacGregor, A., & Haw, S. (2016). Are retail outlets complying with national legislation to protect children from exposure to tobacco displays at point of sale? Results from the first compliance study in the UK. PloS One, 11(3), e0152178. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152178

- Euromonitor International. (2021). Alcoholic Drinks in the United Kingdom, 2021. Euromonitor International.

- Ferguson, K., Giles, L., & Beeston, C. (2021). Evaluating the impact of Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) In Scotland. Public Health Scotland. https://www.publichealthscotland.scot/media/7669/mup-price-distribution-report-english-june2021.pdf

- Ferguson, K., & Madeley, G. (2018). Get set for the North of England booze cruise! Border supermarkets stockpile extra drink as they prepare for Scots to flock south to stock up after it becomes the first country in the world to impose minimum price on alcohol. MailOnline. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5677687/Scotland-imposes-minimum-alcohol-prices-sparking-warnings-English-booze-cruise.html

- Fitzgerald, N., Manca, F., Uny, I., Martin, J. G., O'Donnell, R., Ford, A., Begley, A., Stead, M., & Lewsey, J. (2022). Lockdown and licensed premises: COVID-19 lessons for alcohol policy. Drug and Alcohol Review, 41(3), 533–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13413

- Forsyth, A. J. M., Davidson. N., & Ellaway, A. (2014). ‘I can spot them a mile off’: Community shopkeepers’ experience of alcohol test-purchasing. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 21(3), 221–224. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2013.86095

- Gill, J., Chick, J., Black, H., Rees, C., O'May, F., Rush, R., & McPake, B. A. (2015). Alcohol purchasing by ill heavy drinkers; cheap alcohol is no single commodity. Public Health, 129(12), 1571–1578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.08.013

- Hastings, G., MacKintosh, A. M., Holme, I., Davies, K., Angus, K., & Moodie, C. (2008). Chapter D. Retailer Concerns. In Point of Sale Display of Tobacco Products. A report by the Centre for Tobacco Control Research, University of Stirling. (pp. 29–36). Cancer Research UK. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/aug2008_pointofsale_report_final.pdf

- Haw, S., Currie, D., Eadie, D., Pearce, J., MacGregor, A., Stead, M., Amos, A., Best, C., Wilson, M., Cherrie, M., Purves, R., Ozakinci, G., & MacKintosh, A. M. (2020). Chapter 4 Small retailers’ perspectives on the implementation and impact of point-of-sale legislation. In S. Haw, D. Currie & D. Eadie (Eds.), The Impact of the Point-of-Sale Tobacco Display Ban on Young People in Scotland: Before-and-After Study. (Public Health Research, 8.1) (pp. 27–35). NIHR Journals Library. https://doi.org/10.3310/phr08010

- Hilton, S., Buckton, C. H., Henrichsen, T., Fergie, G., & Leifeld, P. (2020). Policy congruence and advocacy strategies in the discourse networks of minimum unit pricing for alcohol and the soft drinks industry levy. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 115(12), 2303–2314. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15068

- Holden, C., Hawkins, B., & McCambridge, J. (2012). Cleavages and co-operation in the UK alcohol industry: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 12, 483. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-483

- Ikonen, C. (2018). Crippling alcohol price laws rolled out TODAY with booze costs to SOAR. Daily Star Online. https://www.dailystar.co.uk/news/latest-news/alcohol-price-rise-scotland-booze-17134038

- McNee, J. (2018). The bare minimum. Scottish Grocer.

- O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

- Pettigrew, S., Hafekost, C., Jongenelis, M., Pierce, H., Chikritzhs, T., & Stafford, J. (2018). Behind closed doors: the priorities of the alcohol industry as communicated in a trade magazine. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 217. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00217

- Public Health (Alcohol) Act 2018 (Commencement) Order (2021). Republic of Ireland https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2021/si/230/made/en/print

- Public Health (Minimum Price for Alcohol) (Wales) Act (2018). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/anaw/2018/5/enacted

- Public Health Scotland (2021). Monitoring and Evaluating Scotland's Alcohol Strategy (MESAS). Retrieved September 11, 2021, from http://www.healthscotland.scot/health-topics/alcohol/monitoring-and-evaluating-scotlands-alcohol-strategy-mesas

- Purves, R. I., Moodie, C., Eadie, D., & Stead, M. (2019). The response of retailers in Scotland to the Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products Regulations and Tobacco Products Directive. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 21(3), 309–313. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nty181

- Retail Newsagent. (2017). Welsh retailers welcome alcohol unit plans, 5.

- Robinson, M., Mackay, D., Giles, L., Lewsey, J., Richardson, E., & Beeston, C. (2021). Evaluating the impact of minimum unit pricing (MUP) on off-trade alcohol sales in Scotland: an interrupted time-series study. Addiction, 116(10), 2697–2707. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15478

- Rose, G. (2017). Minimum price could push wine to £6 a bottle. The Scottish Mail on Sunday.

- Sandín Vázquez, M., Rivera, J., Conde, P., Gutiérrez, M., Díez, J., Gittelsohn, J., & Franco, M. (2019). Social norms influencing the local food environment as perceived by residents and food traders: The Heart Healthy Hoods project. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030502

- Scheffels, J., & Lavik, R. (2013). Out of sight, out of mind? Removal of point-of-sale tobacco displays in Norway. Tobacco Control, 22(e1), e37–e42. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050341

- Scottish Government. (2013). 3. Drinks Promotions. In Scottish Government, Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Act 2010: guidance for licensing boards. Justice Directorate. https://www.gov.scot/publications/alcohol-etc-scotland-act-2010-guidance-licensing-boards/pages/3/

- Shortt, N. K., Rind, E., Pearce, J., Mitchell, R., & Curtis, S. (2018). Alcohol risk environments, vulnerability and social inequalities in alcohol consumption. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(5), 1210–1227. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1431105

- Stead, M., Critchlow, N., Eadie, D., Fitzgerald, N., Angus, K., Purves, R., McKell, J., MacKintosh, A. M., Mitchell, H., Sumpter, C., & Angus, C. (2020a). Evaluating the Impact of Alcohol Minimum Unit Pricing in Scotland: Observational Study of Small Retailers. NHS Health Scotland/Public Health Scotland.

- Stead, M., Eadie, D., McKell, J., Sparks, L., MacGregor, A., & Anderson, A. S. (2020b). Making hospital shops healthier: evaluating the implementation of a mandatory standard for limiting food products and promotions in hospital retail outlets. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8242-7

- Thompson, C., Clary, C., Er, V., Adams, J., Boyland, E., Burgoine, T., Cornelsen, L., de Vocht, F., Egan, M., Lake, A. A., Lock, K., Mytton, O., Petticrew, M., White, M., Yau, A., & Cummins, S. (2021). Media representations of opposition to the 'junk food advertising ban' on the Transport for London (TfL) network: A thematic content analysis of UK news and trade press. SSM - Population Health, 15, 100828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100828

- Thompson, K., Stockwell, T., Wettlaufer, A., Giesbrecht, N., & Thomas, G. (2017). Minimum alcohol pricing policies in practice: A critical examination of implementation in Canada. Journal of Public Health Policy, 38, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-016-0051-y

- Usidame, B., Miller, E. A., & Cohen, J. E. (2020). Retailer compliance with state and local policies on tobacco advertising. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 6(2), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.18001/TRS.6.2.2

- Van Hoof, J. J., Gosselt, J. F., Baas, N., & De Jong, M. D. T. (2012). Improving shop floor compliance with age restrictions for alcohol sales: effectiveness of a feedback letter intervention. European Journal of Public Health, 22(5), 737–742. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckr162

- Xhurxhi, I. P. (2020). The early impact of Scotland's minimum unit pricing policy on alcohol prices and sales. Health Economics, 29(12), 1637–1656. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4156