Abstract

Aim

The receipt of long-term financial social assistance (FSA) as an indicator of financial difficulties among Finnish youth with prenatal substance exposure (PSE) was investigated in comparison with unexposed youth.

Methods

Data from national health and social welfare registers were collected for 18–24-year-old exposed (n = 355) and unexposed (n = 1011) youth. The influence of youth and maternal characteristics and out-of-home care (OHC) on the association between PSE and youth’s long-term FSA receipt was studied by generalized linear models and mediation analyses.

Results

Exposed youth had an increased likelihood of long-term FSA receipt (OR 4.89, 95% CI 3.76, 6.37) but the difference with unexposed was attenuated following adjustments for youth and maternal characteristics and OHC (AOR 1.33, 95% CI 0.89, 1.98). Maternal long-term FSA receipt (0.48, 95% CI 0.35, 0.64) and OHC (0.63, 95% CI 0.47, 0.83) mediated a large proportion of the association between PSE and youth’s long-term FSA receipt. Youth’s mental or behavioral disorders partly mediated the association (0.21, 95% CI 0.14, 0.30), but the mediating effect of lack of secondary education was minor (0.03, 95% CI 0.01, 0.07).

Conclusion

Receipt of long-term FSA among youth with PSE likely reflects maternal substance abuse linked with maternal financial situation and care instability in childhood.

1. Introduction

Transition to adulthood is a critical period of life characterized by several significant parallel developmental phases and life-course events. These include the psychological transition from parental care and social safety nets, to increased demands on adult role taking including financial independence (Arnett, Citation2000; Scales et al., Citation2016).

During transition phases, temporary financial difficulties can be common among youth (Ilmakunnas & Moisio, Citation2019). In Finland, one important indicator of financial difficulties is the receipt of financial social assistance (FSA) (Haula & Vaalavuo, Citation2021; Ristikari et al., Citation2018). FSA is a means-tested (i.e. only accessible to individuals with insufficient income or resources) last-resort financial benefit for individuals and families living or residing in Finland whose income and assets do not cover the necessary expenses. FSA is intended to help the recipient to overcome temporary financial difficulties. Prior research indicates that receipt of FSA is relatively common among youth, but its duration is often short (Ilmakunnas & Moisio, Citation2019; Raittila et al., Citation2018). Studies in Finland have shown that long-term FSA needs among youth can indicate financial difficulties during the transition to adult independence, and other health and social concerns or disadvantaged family background (Haula & Vaalavuo, Citation2021; Ilmakunnas & Moisio, Citation2019; Vauhkonen et al., Citation2017). These studies also show that youth with long-term FSA needs can be in a socially disadvantaged position during the transition to adult independence and have an increased risk of further problems in being an active member of society (Ilmakunnas & Moisio, Citation2019; Ristikari et al., Citation2018).

Financial difficulties in youth can be especially common in the setting of prenatal substance exposure (PSE) (i.e. alcohol and/or illicit drugs) and are potentially explained by the direct effects of PSE on cognitive and behavioral functioning and health overall (Behnke & Smith, Citation2013; Gunn et al., Citation2016; Mattson et al., Citation2019). Impairments in cognitive and behavioral functioning associated with PSE can contribute to challenges with adaptive functioning, mental health, educational attainment, and independent living (Fagerlund et al., Citation2012; McLachlan et al., Citation2020; Oei, Citation2018; Weyrauch et al., Citation2017). Impairments and challenges in these areas can increase the risk of financial difficulties among exposed youth.

Financial difficulties among youth with PSE can also be linked to adverse childhood caregiving factors (e.g. parental socioeconomic and psychological adversities) and childhood caregiving instability commonly co-occurring with PSE (Flannigan et al., Citation2021; Price et al., Citation2017; Sarkola et al., Citation2007). Interrelated risk factors in the childhood caregiving environment including parental financial difficulties, substance abuse and mental health disorders can negatively influence youth’s developmental outcomes including mental health and educational attainment (Pitkänen et al., Citation2021; Raitasalo et al., Citation2021; Weitoft et al., Citation2008), and thus, directly or indirectly, increase youth’s vulnerability to financial difficulties (Haula & Vaalavuo, Citation2021; Ilmakunnas & Moisio, Citation2019; Kauppinen et al., Citation2014; Ristikari et al., Citation2018).

Furthermore, children with PSE are often placed in out-of-home care (OHC) in early childhood (Flannigan et al., Citation2021; Sarkola et al., Citation2007). In the Finnish child welfare system, OHC is considered the last-resort measure of municipal child protective services. A child can be taken into OHC if the home environment or child’s behavior seriously endangers their health or development, and non-residential services are insufficient. The reasons for OHC among small children typically include neglect due to parental mental health problems, parental substance abuse, and family violence. Reasons for OHC among older children and youth typically relate to offspring factors such as major mental health disorders or behavioral problems (e.g. violence, substance abuse, criminality) or severe problems endangering school participation (Heino et al., Citation2016). In a Finnish cohort study including children born in 1997 (n = 57 174), 5.7% of the children had experienced placement in OHC prior to the 18th birthday (Kääriälä et al., Citation2021). Prior studies show troubling outcomes including mental and behavioral disorders, lower educational attainment, and financial difficulties among youth with OHC history (Gypen et al., Citation2017; Kääriälä et al., Citation2019; Vinnerljung & Sallnäs, Citation2008). Therefore, financial difficulties among youth with PSE can also reflect care instability in their childhood environment and difficulties during the transition from OHC to financial independence.

Research on financial difficulties among youth with PSE and the influence of youth and maternal characteristics and OHC on financial difficulties in young adulthood is lacking. Financial difficulties in youth with PSE during the transition to adulthood can indicate other health and social concerns and predispose the youth to further social problems. Studying financial difficulties in these populations is important to prevent further challenges in life. Therefore, the aim was to compare the receipt of long-term FSA as an indicator of financial difficulties among 18–24-year-old youth with PSE with a matched unexposed cohort. The second aim was to investigate associations between youth’s long-term FSA receipt and youth and maternal postnatal characteristics, and OHC. The third aim was to investigate how these characteristics mediate the association between PSE and youth’s long-term FSA receipt.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

ADEF Helsinki (Alcohol/Drugs Exposure during Fetal life) is a longitudinal register-based cohort study including data for 615 youth with PSE (i.e. exposed cohorts) and 1787 unexposed youth aged 15–24 years (Koponen et al., Citation2020). In the present study, we focused on the receipt of long-term FSA after the age of 18. Therefore, the data comprised individuals from the ADEF cohort aged 18–24 years at the end of follow-up in 2016 (i.e. individuals born in 1992–1998) including 368 exposed and 1060 unexposed youth. The following cases were excluded: (1) individuals with intellectual disability (primary diagnosis from specialized healthcare, i.e. inpatient or outpatient hospital care following the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems ICD-9 codes 317–319, ICD-10 codes F70–F79) (6 exposed, 10 unexposed), and (2) individuals who died or were lost during the follow-up (7 exposed, 39 unexposed). The final study population included 355 exposed and 1011 unexposed youth aged 18–24 years.

The exposed cohort consisted of children born to women with a history of intensified pregnancy follow-up and counseling provided every 2–4 weeks at special multidisciplinary HAL clinics (abbreviation for illicit drugs, alcohol, and central nervous system medicines with abuse potential) at the Helsinki University Maternity Hospital (Helsinki, Finland) serving the Helsinki metropolitan area. HAL clinics are outpatient clinics established in 1983. These clinics have extensive experience in the antenatal follow-up of pregnant women with substance abuse including intensified frequent follow-ups and counselling during antenatal follow-up, and screening of substance use (i.e. alcohol, cannabis, amphetamine, heroin, buprenorphine, and other drugs) based on self-report, voluntary urine toxicology screenings, and conventional blood tests reflecting alcohol consumption (Sarkola et al., Citation2000). HAL clinics also offer referrals for the treatment of opioid dependence. Indications for a referral from primary healthcare maternity clinics to the HAL clinics included an Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) score ≥8 points, ongoing maternal opioid maintenance treatment, drug abuse, or nonmedical use of central nervous system medication.

In ADEF, three unexposed mother-child dyads with no evidence of maternal substance abuse in national registers within one year prior to or at the time of the child’s birth were obtained from the Medical Birth Register for each exposed mother-child dyad. The population-based exposed and unexposed cohorts were matched for five characteristics, including maternal age, parity, number of fetuses, the month of birth, and delivery hospital of the index child. Register data () were collected identically for exposed and unexposed mother-child dyads and linked using unique personal identification numbers.

Table 1. Summary of the main outcome variable, mediators and covariates, and data sources.

The study was approved by the local ethical committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa. The authorities maintaining the registers approved the use of data. The register linkages and pseudonymization of the data were conducted by the Finnish Institute of Health and Welfare (THL) as the statistical authority. Study subjects were not contacted, and thus informed consent was not required.

2.2. Main outcome variable

Youth’s financial difficulties were measured by the receipt of long-term financial social assistance (FSA). Information on the receipt of FSA in 2010–2016 was obtained from the Register of Social Assistance maintained by THL (). The study focused on primary FSA, including basic FSA and supplementary FSA. Basic FSA is intended to cover expenses for daily necessities (e.g. food, clothing, and transportation), whereas supplementary FSA is intended to cover other expenses or necessary expenses arising from special needs (e.g. pharmaceuticals) or circumstances.

Long-term FSA receipt has been defined in various ways in prior research. According to the Finnish Law (Act of Rehabilitative Work) (Laki kuntouttavasta työtoiminnasta 189/2001, Citation2001), a youth less than 25 years can be referred to rehabilitate work if she/he has been recipient of FSA for more than four months during a calendar year. Following the law, FSA receipt was considered prolonged among the youth if received for at least four months during a calendar year. Therefore, long-term FSA was defined as receipt of FSA for four months or longer during a calendar year at least once during the follow-up, to exclude brief 1–3-month FSA provided during educational summer breaks (Ristikari et al., Citation2018).

2.2.1. Other characteristics of youth's financial social assistance receipt

We also included other characteristics of youth financial social assistance receipt in the descriptive analyses, including age at the first long-term FSA receipt and the number of years for which it was granted ().

2.3. Mediator variables

The selection of mediators was based on prior research showing associations between maternal substance abuse during pregnancy, and financial difficulties among youth (Flannigan et al., Citation2021; Haula & Vaalavuo, Citation2021; Kauppinen et al., Citation2014) as well as data availability within the ADEF Helsinki study. Detailed information on mediators and data sources are outlined in .

Youth characteristics included the presence of mental or behavioral disorders and information on secondary education completion. Mental or behavioral disorders were defined by at least one specialized healthcare episode due to primary or secondary ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis. Secondary education completion by the end of follow-up was coded as present or not present.

Maternal postnatal characteristics included mental or behavioral disorders, maternal substance abuse, and maternal financial difficulties measured by the receipt of long-term FSA. Maternal mental or behavioral disorders were defined as at least one specialized healthcare care episode due to primary or secondary ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnoses. Maternal substance abuse was defined by primary ICD-9 and ICD-10 substance abuse-related diagnoses from specialized healthcare care. Maternal receipt of long-term FSA was defined similarly to youth long-term FSA receipt. These maternal characteristics were derived from the registers from the child’s birth until 18th birthday.

Out-of-home care (OHC) was defined as at least one OHC episode between the child’s birth and 18th birthday. We also included additional characteristics of OHC (age at the first OHC episode, cumulative length of OHC episodes) in the descriptive analysis.

2.4. Data analyses

First, we compared (1) the characteristics of youth and their mothers between the exposed and unexposed cohorts, and (2) the same characteristics between the exposed and unexposed recipients of long-term FSA, using the Chi-Squared test (χ2) and Mann-Whitney U-test. The long-term FSA needs between the cohorts were analyzed using the χ2-test and Independent-Samples t-Test. We present results from the descriptive analyses as counts and percentages, medians and Interquartile Range (IQR), as well as means and standard deviations (SD).

Second, we defined unadjusted and adjusted associations between PSE, youth (i.e. sex, mental or behavioral disorders, lack of secondary education) and maternal characteristics (i.e. mental or behavioral disorders, substance abuse, receipt of long-term FSA), OHC, and youth’s receipt of long-term FSA with generalized linear models. First, we regressed bivariate associations between PSE, the youth and maternal characteristics, and OHC and the youth’s receipt of long-term FSA. Second, in the adjusted model, we included all the youth and maternal characteristics and OHC simultaneously to account for the potential effect of these predictors on the association between PSE and youth’s receipt of long-term FSA. The model was also adjusted for the follow-up time to account for differences in the follow-up time between birth years, and thus, for the likelihood of FSA receipt. The results of the unadjusted and adjusted models are reported as parameter estimates (b) with standard error (SE), odds ratios (OR), and p-values.

Mediation analyses were applied to investigate how the association between PSE and youth’s receipt of long-term FSA is mediated by the selected mediators. The selection of the variables for the mediation analyses in a combined exposed and unexposed dataset was based on the results from the adjusted generalized linear models and included variables showing independent associations with youth’s long-term FSA receipt (i.e. youth’s mental or behavioral disorders, lack of secondary education, maternal receipt of long-term FSA, and OHC).

We first defined the direct association (c’) between PSE (X) and the youth’s receipt of long-term FSA (Y). Second, we defined path a, which indicates the association between PSE (X) and mediator (M). Third, we defined path b, indicating the association between mediator (M) and youth’s receipt of long-term FSA (Y) while controlling for the effect of PSE (X). Fourth, the indirect (ab) association and total effect (c) were defined. Indirect association indicates the mediation effect (i.e. the effect of PSE on youth’s receipt of long-term FSA that goes through a mediator), whereas total effect (c) sums the direct and indirect effects. Lastly, the proportion mediated describes the proportion of the effect of X on Y that goes through the mediator (M). The results of mediation analyses are reported as parameter estimates (b) with standard errors (SE), 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI), and p-values.

Statistical significance was set to p < 0.05. The descriptive analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 28, and the bivariate and multivariable generalized linear models with R. The mediation analyses were performed with a bootstrapping method including 1000 simulations and conducted with the mediation package for R (Tingley et al., Citation2014).

3. Results

Characteristics of and differences between exposed and unexposed cohorts are presented in . The median follow-up time in years in the exposed and unexposed cohorts was 20.5 (IQR 19.2, 22.7) and 20.4 (IQR 19.2, 22.5) (p = 0.770), respectively. Exposed and unexposed cohorts differed in all characteristics except for sex. Mental or behavioral disorders were more common in the exposed youth compared with the unexposed youth (57.2% vs. 28.5%, p < 0.001), and a lower proportion of the exposed youth had completed secondary education at follow-up (30.1% vs. 41.3%, p < 0.001) compared with the unexposed youth. Mothers of exposed children were more likely to have been in specialized healthcare for mental or behavioral disorders and substance abuse and were more often recipients of long-term FSA compared with mothers of unexposed children. A majority of the exposed had at least one OHC episode compared with the unexposed (64.5% vs. 7.0%, p < 0.001). The exposed had been placed in OHC at a younger age (3.2 vs. 12.9 years, p < 0.001) and for a longer time period (10.6 vs. 1.6 years, p < 0.001) compared with the unexposed ().

Table 2. Descriptive characteristics and comparison of 18–24-year-old exposed and unexposed youth and recipients of long-term financial social assistance.

The comparison of characteristics of the exposed and unexposed recipients of long-term FSA indicated no sex or educational differences between the cohorts. The exposed and unexposed recipients of long-term FSA differed significantly with respect to the other youth and maternal characteristics and OHC ().

The comparison of long-term FSA receipt between the cohorts indicated that the receipt of long-term FSA was significantly more common among the exposed compared with the unexposed youth (50.4% vs. 17.2%, p < 0.001). The comparison of other characteristics between the cohorts indicated that the exposed were slightly younger at first long-term FSA receipt (18.8 years vs. 19.3 years, p < 0.001) and received long-term FSA for a longer period on average (2.5. years vs. 2.1 years, p = 0.039) compared with the unexposed youth ().

Table 3. Comparison of receipt of financial social assistance among 18–24-year-old exposed and unexposed youth.

presents the unadjusted and adjusted predictors of youth’s receipt of long-term FSA. Results of the unadjusted analyses indicated that exposed youth had a nearly five-fold increased likelihood of long-term FSA receipt compared with the unexposed youth (OR 4.89, 95% CI 3.76, 6.37). The results also indicated that youth characteristics including mental or behavioral disorders and lack of secondary education, maternal postnatal characteristics including maternal mental or behavioral disorders, substance abuse and receipt of long-term FSA, and OHC were positively associated with youth’s receipt of long-term FSA. After adjusting the analysis for all the variables simultaneously, the difference in the likelihood of long-term FSA receipt between the exposed and unexposed cohorts was attenuated to nonsignificant levels (AOR 1.33, 95% CI 0.89, 1.98), and the youth’s mental or behavioral disorders (AOR 2.28, 95% CI 1.68, 3.10), lack of secondary education (AOR 5.39, 95% CI 3.55, 8.17), maternal receipt of long-term FSA (AOR 3.09, 95% CI 2.13, 4.48), and OHC (AOR 3.39, 95% CI 2.20, 5.23) were independently associated with youth’s receipt of long-term FSA.

Table 4. Unadjusted and adjusted predictors of long-term financial social assistance receipt among 18–24-years old youth.

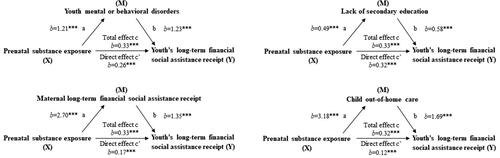

Next, mediation analyses were conducted to investigate whether these independent predictors of youth’s long-term FSA receipt mediate the association between PSE and youth’s long-term FSA receipt ( and ). A positive association was found between PSE and youth’s mental or behavioral disorders (b = 1.21, p < 0.001), and the association between PSE and youth’s receipt of long-term FSA was partly mediated by these disorders (0.21, 95% CI 0.14, 0.30). PSE was also positively associated with the lack of secondary education (b = 0.49, p < 0.001), but only 3% (95% CI 0.01, 0.07) of the association between PSE and youth’s long-term FSA receipt was mediated by the lack of secondary education. The results also indicated that PSE was strongly associated with maternal long-term FSA receipt (b = 2.70, p < 0.001) and OHC (b = 3.18, p < 0.001). A large proportion of the association between PSE and youth’s long-term FSA receipt was mediated by maternal long-term FSA receipt (0.48, 95% CI 0.35, 0.64) and OHC (0.63, 95% CI 0.47, 0.83) (, ).

Figure 1. The mediating effect of youth mental or behavioral disorders (M), lack of secondary education (M), maternal long-term financial social assistance receipt (M) and child out-of-home care (M) on the association between prenatal substance exposure (X) and youth’s long-term financial social assistance receipt (Y). Parameter estimates (b) with p-value ***p < 0.001.

Table 5. The mediating effect of youth’s characteristics (i.e. mental or behavioral disorders, lack of secondary education), maternal long-term financial social assistance receipt and child out-of-home care on the association between prenatal substance exposure and youth’s long-term financial social assistance (FSA) receipt.

4. Discussion

In this study, financial difficulties measured by the receipt of long-term financial social assistance (FSA) were significantly more common among 18–24-year-old youth with a history of prenatal substance exposure (PSE) compared with a matched prenatally unexposed cohort. However, this study found that the difference in long-term FSA receipt between exposed and unexposed cohorts was largely explained by maternal financial difficulties, also measured by the receipt of long-term FSA, child’s out-of-home care (OHC), and to some degree also by youth mental or behavioral disorders. Youth’s lack of secondary education explained only a small proportion of the association between PSE and youth’s long-term FSA needs. Overall, it seems that financial difficulties among exposed youth are largely predicted by maternal substance abuse and dependence linked with maternal financial situation and care instability in childhood (OHC), and to some extent also by youths mental or behavioral disorders possibly influencing cognitive and behavioral functioning and overall wellbeing during the transition to adult independence.

This study expands previous research on financial difficulties among the general youth population by investigating long-term FSA needs among a vulnerable youth population with PSE. We were unable to find similar studies on financial difficulties among youth born to mothers followed up prenatally for substance abuse. Studies from the general youth population show that temporary financial difficulties are common among youth during transition phases (Ilmakunnas & Moisio, Citation2019). It has been reported that 18.9% of 18–24-year-old Finnish youth received FSA for at least one month in 2017, and for a majority, the receipt of FSA was short-term (Raittila et al., Citation2018). In another Finnish study, 29.8% of youth aged 18–24-years received FSA for at least one month during the study period (Haula & Vaalavuo, Citation2021). Although these estimates are not fully comparable due to differences in the studied duration and form of FSA and changes in the administration of FSA in Finland in 2017, receipt of long-term FSA among exposed youth (50.4%) is significantly higher than the estimates in the general Finnish youth population (Haula & Vaalavuo, Citation2021; Raittila et al., Citation2018).

The financial difficulties among the exposed youth could be linked to the direct effect of PSE on children’s cognitive and behavioral functioning and health (Behnke & Smith, Citation2013; Gunn et al., Citation2016; Mattson et al., Citation2019), which, can contribute to challenges with adaptive functioning, mental health, educational attainment and independent living (Fagerlund et al., Citation2012; McLachlan et al., Citation2020; Weyrauch et al., Citation2017). Problems in these areas can be reflected as financial difficulties during the transition to adulthood among exposed youth. Lower educational attainment and other psychosocial outcomes among exposed youth may add to this (Howell et al., Citation2006; Nissinen et al., Citation2021; Rangmar et al., Citation2015). However, our findings indicated no difference in secondary education completion between exposed and unexposed recipients of long-term FSA, and this is consistent with only a marginal prediction of long-term FSA needs in our mediation analyses. We speculate that the small mediating effect of lack of secondary education in the mediation analysis could be due to the relatively young age of our study cohort, low proportion of completed secondary education overall, but also the mitigating support from the population-based mandatory comprehensive Finnish education system. The previously reported time lag in secondary education completion in our prenatally exposed cohort might, however, predict long-term FSA needs later in adulthood (Nissinen et al., Citation2021).

Our findings linking youth’s mental or behavioral disorders with financial difficulties are consistent with previous studies (Haula & Vaalavuo, Citation2021; Ringbom et al., Citation2021). The results of the mediation analyses also showed that youth’s mental or behavioral disorders partly mediate the association between PSE and long-term FSA needs.

Our results also show that youth with PSE face the accumulation of several interrelated risk factors and care instability in childhood that can predispose them to financial difficulties, as also reported in prior studies from the general youth population (Gypen et al., Citation2017; Ilmakunnas & Moisio, Citation2019; Kauppinen et al., Citation2014). Children and youth exposed to substances prenatally often face double jeopardy (Carta et al., Citation2001; Flannigan et al., Citation2018). Not only are their developmental outcomes influenced by PSE, but they are also often exposed to an accumulation of risk factors in their postnatal caregiving environment, including socioeconomic and psychological adversities (Carta et al., Citation2001; Flannigan et al., Citation2018). Due to this, youth exposed to substances prenatally can be more vulnerable to risks and stress during the transition to adulthood, potentially predisposing them to other challenges then, including financial difficulties.

Our findings showed that maternal financial difficulties were common among mothers of exposed children, that is, mothers with potential substance abuse during pregnancy. In addition, maternal financial difficulties mediated a large proportion of PSE-related long-term FSA needs. Studies from the general youth population show that family socioeconomic factors including financial difficulties can predict youth's long-term FSA needs (Kauppinen et al., Citation2014; Ristikari et al., Citation2018). Parents with financial difficulties may not have the resources to support the youth during their transition to independent adulthood, and thus, FSA is needed to ensure this process. Parental financial difficulties can also reflect the accumulation of adversities including parental mental health disorders or substance abuse (Jääskeläinen et al., Citation2016), which can directly or indirectly increase youth’s vulnerability to poor developmental outcomes (Pitkänen et al., Citation2021; Raitasalo et al., Citation2021; Rodwell et al., Citation2018), and influence their transition to financial self-support (Haula & Vaalavuo, Citation2021; Ilmakunnas, Citation2018; Kauppinen et al., Citation2014; Ristikari et al., Citation2018).

Moreover, the results indicated that a significant proportion of the exposed youth had been placed in OHC during early childhood. Long-term outcomes in various life areas including financial self-support difficulties tend to be common among youth with OHC history (Gypen et al., Citation2017; Kääriälä et al., Citation2019; Vinnerljung & Sallnäs, Citation2008). In Finland, the receipt of FSA among youth with OHC history can reflect the aftercare services provided following OHC. However, the receipt of FSA can also reflect a lack of social and financial support or other factors including mental or behavioral disorders or educational challenges which can predispose former OHC youth to a challenging transition to financial self-support. Our results also showed that OHC was associated with the youth’s financial difficulties, and the results of the mediation analyses indicated that OHC mediated a large proportion of the association between PSE and the youth’s receipt of long-term FSA. However, studies extending into later adulthood are needed to investigate the transition from OHC to financial independence.

Studies extending into adulthood are also needed to investigate whether the financial difficulties among youth with PSE reflect challenges in establishing financial independence during young adulthood or long-term challenges in being an active member of society.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the study include a matched unexposed cohort and the availability of data on factors known to be associated with financial difficulties among youth. By using a prospective hospital medical record and comprehensive mandatory national register-based study design, we were able to avoid data collection inaccuracies related to retrospective self-reported information, low response rate, recall bias (e.g. under-reporting of adverse events), or losses in the follow-up. We also consider the mediation analyses exploring the role of different predictors explaining the variance of the association between prenatal substance exposure and youth’s long-term financial social assistance receipt in our combined exposed and unexposed dataset as a strength.

We acknowledge limitations related to the lack of data on the type, timing, and severity of maternal substance use during pregnancy. Self-reported information on substance use is inevitably inaccurate, precluding analyses on independent associations with a specific type of substance, and hence, the exposed vs. unexposed categorization was used in the analysis. Our exposed cohort includes children born to mothers with significant substance abuse identified at maternity clinics and therefore excludes children born to mothers with low or occasional substance use during pregnancy. We acknowledge that the unexposed cohort may include women with minor substance use during pregnancy not identified by screening the registers for maternal substance abuse-related primary and secondary diagnosis and external causes of injuries from outpatient and inpatient hospital care one year prior or at the time of child’s birth among the mothers of the unexposed children. Another limitation is the lack of information on another caregiver that may have an equal and significant role in the youth’s life including the father or foster parent(s).

By using register data, we may not have captured all potential characteristics of the childhood caregiving environment that may influence financial difficulties in youth. However, OHC, as the last-resort measure of municipal child protective services, generally indicates significant challenges in the caregiving environment endangering a child’s health and development. Another limitation related to the register data relates to data on secondary education that was only available until 2015. Thus, the number of exposed and unexposed who have completed secondary education by the end of 2015, especially among the youngest study participants, may be underestimated. Lastly, considering the study’s observational nature, causal links cannot be proved.

5. Conclusions

This study finds financial difficulties to be more common among 18–24-year-old youth with prenatal substance exposure (PSE) compared with unexposed youth. However, the increased likelihood of long-term FSA among exposed youth was attenuated to nonsignificant levels when adjusting for youth and maternal postnatal characteristics and child OHC. The results from the mediation analysis indicated that the association between PSE and youth’s financial difficulties were mainly mediated by maternal financial difficulties and child OHC, and partly by youth mental or behavioral disorders. Lack of secondary education was related to financial difficulties only to a minor extent, and this likely reflects the mitigating support from the population-based mandatory comprehensive Finnish education system. It seems that FSA among youth with PSE to ensure the transition to adult independence likely reflects maternal substance abuse and dependence linked with maternal financial situation and care instability in childhood. Early identification and support of youth at risk seem important for optimizing the transition to financial independence.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Aku-Ville Lehtimäki for advice on statistical analyses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data are not publicly available due to data confidentiality and the authors do not have permission to share the data. Similar data can be applied from Findata, the Finnish Social and Health Data Permit Authority: (https://findata.fi/en/).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. The American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

- Behnke, M., & Smith, V. C. (2013). Prenatal substance abuse: Short- and long-term effects on the exposed fetus. Pediatrics, 131(3), 1009. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3931

- Carta, J. J., Atwater, J. B., Greenwood, C. R., McConnell, S. R., McEvoy, M. A., & Williams, R. (2001). Effects of cumulative prenatal substance exposure and environmental risks on children’s developmental trajectories. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(3), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_5

- Fagerlund, Å., Autti-Rämö, I., Kalland, M., Santtila, P., Hoyme, H. E., Mattson, S. N., & Korkman, M. (2012). Adaptive behaviour in children and adolescents with foetal alcohol spectrum disorders: A comparison with specific learning disability and typical development. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 21(4), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-012-0256-y

- Flannigan, K., Kapasi, A., Pei, J., Murdoch, I., Andrew, G., & Rasmussen, C. (2021). Characterizing adverse childhood experiences among children and adolescents with prenatal alcohol exposure and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Child Abuse & Neglect, 112, 104888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104888

- Flannigan, K., Pei, J., Stewart, M., & Johnson, A. (2018). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and the criminal justice system: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 57, 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2017.12.008

- Gunn, J. K. L., Rosales, C. B., Center, K. E., Nuñez, A., Gibson, S. J., Christ, C., & Ehiri, J. E. (2016). Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 6(4), e009986. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009986

- Gypen, L., Vanderfaeillie, J., Maeyer, S. d., Belenger, L., & Holen, F. v (2017). Outcomes of children who grew up in foster care: Systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 76, 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.02.035

- Haula, T., & Vaalavuo, M. (2021). Mental health problems in youth and later receipt of social assistance: Do parental resources matter? Journal of Youth Studies, 2021, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.1923676

- Heino, T., Hyry, S., Ikäheimo, S., Kuronen, M., & Rajala, R. (2016). Lasten kodin ulkopuolelle sijoittamisen syyt, taustat, palvelut ja kustannukset: HuosTa-hankkeen (2014–2015) päätulokset. [Reasons, backgrounds, services and costs concerning the placing of children outside the home. Main results from the HuosTa project (2014–2015)]. Raportti 3. Helsinki: Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos.

- Howell, K. K., Lynch, M. E., Platzman, K. A., Smith, G. H., & Coles, C. D. (2006). Prenatal alcohol exposure and ability, academic achievement, and school functioning in adolescence: A longitudinal follow-up. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31(1), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsj029

- Ilmakunnas, I. (2018). Risk and vulnerability in social assistance receipt of young adults in Finland. International Journal of Social Welfare, 27(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12273

- Ilmakunnas, I., & Moisio, P. (2019). Social assistance trajectories among young adults in Finland: What are the determinants of welfare dependency? Social Policy & Administration, 53(5), 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12413

- Jääskeläinen, M., Holmila, M., Notkola, I. L., & Raitasalo, K. (2016). A typology of families with parental alcohol or drug abuse. Addiction Research and Theory, 24(4), 288–299. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2015.1127358

- Kääriälä, A., Gyllenberg, D., Sund, R., Pekkarinen, E., Keski-Säntti, M., Ristikari, T., Heino, T., & Sourander, A. (2021). The association between treated psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders and out-of-home care among Finnish children born in 1997. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 1789–1798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01819-1

- Kääriälä, A., Haapakorva, P., Pekkarinen, E., & Sund, R. (2019). From care to education and work? Education and employment trajectories in early adulthood by children in out-of-home care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98, 104144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104144

- Kauppinen, T. M., Angelin, A., Lorentzen, T., Bäckman, O., Salonen, T., Moisio, P., & Dahl, E. (2014). Social background and life-course risks as determinants of social assistance receipt among young adults in Sweden, Norway and Finland. Journal of European Social Policy, 24(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928714525818

- Koponen, A. M., Nissinen, N.-M., Gissler, M., Sarkola, T., Autti-Rämö, I., & Kahila, H. (2020). Cohort profile: ADEF Helsinki – A longitudinal register-based study on exposure to alcohol and drugs during foetal life. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 37(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072519885719

- Laki kuntouttavasta työtoiminnasta 189/2001 (2001). Retrieved from https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2001/20010189

- Mattson, S. N., Bernes, G. A., & Doyle, L. R. (2019). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: A review of the neurobehavioral deficits associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(6), 1046–1062. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14040

- McLachlan, K., Flannigan, K., Temple, V., Unsworth, K., & Cook, J. L. (2020). Difficulties in daily living experienced by adolescents, transition-aged youth, and adults with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 44(8), 1609–1624. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14385

- Nissinen, N.-M., Gissler, M., Sarkola, T., Kahila, H., Autti-Rämö, I., & Koponen, A. M. (2021). Completed secondary education among youth with prenatal substance exposure: A longitudinal register-based matched cohort study. Journal of Adolescence, 86, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.11.006

- Oei, J. L. (2018). Adult consequences of prenatal drug exposure. Internal Medicine Journal, 48(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.13658

- Pitkänen, J., Remes, H., Moustgaard, H., & Martikainen, P. (2021). Parental socioeconomic resources and adverse childhood experiences as predictors of not in education, employment, or training: A Finnish register-based longitudinal study. Journal of Youth Studies, 24(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1679745

- Price, A., Cook, P. A., Norgate, S., & Mukherjee, R. (2017). Prenatal alcohol exposure and traumatic childhood experiences: A systematic review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.05.018

- Raitasalo, K., Østergaard, J., & Andrade, S. B. (2021). Educational attainment by children with parental alcohol problems in Denmark and Finland. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 38(3), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072520968343

- Raittila, S., Korpela, T., Ylikännö, M., Laatu, M., Heinonen, H.-M., Jauhiainen, S., & Helne, T. (2018). Nuoret ja perustoimeentulotuen saanti. Rekisteriselvitys. Työpapereita. 138. Helsinki: Kela.

- Rangmar, J., Sandberg, A. D., Aronson, M., & Fahlke, C. (2015). Cognitive and executive functions, social cognition and sense of coherence in adults with fetal alcohol syndrome. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 69(6), 472–478. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2015.1009487

- Ringbom, I., Suvisaari, J., Kääriälä, A., Sourander, A., Gissler, M., Ristikari, T., & Gyllenberg, D. (2021). Psychiatric disorders diagnosed in adolescence and subsequent long-term exclusion from education, employment or training: Longitudinal national birth cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 2021, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.146

- Ristikari, T., Merikukka, M., & Hakovirta, M. K. (2018). Timing and duration of social assistance receipt during childhood on early adult outcomes. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 9(3), 312–326. https://doi.org/10.14301/llcs.v9i3.471

- Rodwell, L., Romaniuk, H., Nilsen, W., Carlin, J. B., Lee, K. J., & Patton, G. C. (2018). Adolescent mental health and behavioural predictors of being NEET: A prospective study of young adults not in employment, education, or training. Psychological Medicine, 48(5), 861–871. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002434

- Sarkola, T., Eriksson, C. J., Niemelä, O., Sillanaukee, P., & Halmesmäki, E. (2000). Mean cell volume and gamma-glutamyl transferase are superior to carbohydrate-deficient transferrin and hemoglobin-acetaldehyde adducts in the follow-up of pregnant women with alcohol abuse. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 79(5), 359–366.

- Sarkola, T., Kahila, H., Gissler, M., & Halmesmäki, E. (2007). Risk factors for out-of-home custody child care among families with alcohol and substance abuse problems. Acta paediatrica, 96(11), 1571–1576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00474.x

- Scales, P. C., Benson, P. L., Oesterle, S., Hill, K. G., Hawkins, J. D., & Pashak, T. J. (2016). The dimensions of successful young adult development: A conceptual and measurement framework. Applied Developmental Science, 20(3), 150–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2015.1082429

- Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, L., & Imai, K. (2014). Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 59, 1–38. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v059.i05

- Vauhkonen, T., Kallio, J., Kauppinen, T., & Erola, J. (2017). Intergenerational accumulation of social disadvantages across generations in young adulthood. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 48, 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2017.02.001

- Vinnerljung, B., & Sallnäs, M. (2008). Into adulthood: A follow-up study of 718 young people who were placed in out-of-home care during their teens. Child & Family Social Work, 13(2), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2007.00527.x

- Weitoft, G. R., Hjern, A., Batljan, I., & Vinnerljung, B. (2008). Health and social outcomes among children in low-income families and families receiving social assistance – A Swedish national cohort study. Social Science & Medicine, 66(1), 14–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.031

- Weyrauch, D., Schwartz, M., Hart, B., Klug, M., & Burd, L. (2017). Comorbid mental disorders in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 38(4), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000440