Abstract

Relationships between stress and alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence, and alcohol harms as mediated by drinking to cope and moderated by gender and education were investigated. Australian participants completed online surveys during 2020 (T1: n = 589, Mage = 51.3, 67.7% female; T2: n = 493; T3: n = 487; T4: n = 311). Participants completed the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales stress subscale, the Drinking Motives Questionnaire for Adults ‘Drinking to cope’ subscale, and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. T1 drinking to cope mediated the relationship between T1 stress and alcohol consumption at all time points (R2T1 = 0.24, R2T2 = 0.17, R2T3 = 0.21, R2T4 = 0.11). T4 drinking to cope mediated the relationship between T1 stress and T4 alcohol consumption (R2T1 = 0.15). Furthermore, a stronger effect was found for men in the relationship between T1 stress and T4 alcohol consumption as mediated by T4 drinking to cope (R2T4 = .18). No other relationships were found. Overall, drinking to cope appears to explain some of the increase in alcohol consumption across time due to stress and patterns of drinking to cope with stress appear to develop more strongly over time for men.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Alcohol consumption is a leading risk factor for death worldwide and is responsible for a 2.4% reduction in adjusted life years for women and a 6.8% reduction in adjusted life years for men (Griswold et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, regular and heavy alcohol consumption can lead to dependence (Hashimoto & Wiren, Citation2008) and can result in physical harm to the user and others (Cherpitel et al., Citation2019). These alcohol-related harms can include ‘blackouts’ (Wilhite & Fromme, Citation2015), home and traffic injuries (Bunker et al., Citation2017; Cherpitel et al., Citation2018), and the perpetration of violence (Duke et al., Citation2018; Leonard & Quigley, Citation2017; Lorenz & Ullman, Citation2016).

People are motivated to consume alcohol for a variety of reasons. Typically, these drinking motives are measured using the Drinking Motives Questionnaire–Revised (DMQ-R; Cooper, Citation1994) which has been widely used to study the drinking motives of adolescents and young adults (individuals 18–25 years-old) (Fernandes-Jesus et al., Citation2016; Haynes et al., Citation2018; Lac & Donaldson Citation2016; Lyvers et al., Citation2018; Maphisa & Young, Citation2018; Martin et al., Citation2016; Mosher Ruiz et al., Citation2017; Sun et al., Citation2015). While much of the extant drinking motives literature has focussed on drinking in adolescent and young adult samples, adults represent most of the drinking population and those most likely to report to treatment for their alcohol usage (Wallenstein et al., Citation2007). Recently, we developed and validated a Drinking Motives Questionnaire for Adults (DMQ-A) which we propose as a more suitable alternative when studying adults (D’Aquino et al., Citation2023). Our research highlighted five factors of adult drinking motives. These include drinking alcohol for its taste, for its euphoric effects, to facilitate social interaction, as a way of alleviating social nervousness, and to cope with negative thoughts or feelings.

Drinking to cope (drinking to cope with negative thoughts and feelings) has been consistently found to predict greater alcohol consumption and greater alcohol harm among adults using both the DMQ-R (Lac & Donaldson, Citation2017; Mohr et al., Citation2018) and the DMQ-A (D’Aquino, et al., Citation2023). Moreover, drinking to cope has been linked with substance use disorders (Anker et al., Citation2016), symptoms of alcohol dependence (Crum et al., Citation2013), depression (Grazioli et al., Citation2018; Villarosa et al., Citation2018), anxiety sensitivity (Allan et al., Citation2015; DeMartini & Carey, Citation2011), anxiety (Bravo & Pearson, Citation2017; Kushner et al., Citation2001), and stress (Rice & Van Arsdale, Citation2010; Temmen & Crockett, Citation2020). This association between drinking to cope with symptoms of psychopathology supports the notion that alcohol is used by some as a means of self-medicating (Robinson et al., Citation2009).

Research has demonstrated that drinking to cope mediates the relationship between stress and alcohol outcomes including alcohol consumption and alcohol harms cross-sectionally (Rice & Van Arsdale, Citation2010; Temmen & Crockett, Citation2020). This suggests a chain of events from stress leading to drinking to cope and subsequently leading to excessive and harmful drinking. While the temporal order of stress, drinking to cope, and alcohol outcomes are not assessed with cross-sectional research, Hatzenbuehler et al. (Citation2011) found this association may exist longitudinally. However, it is worth noting that Hatzenbuehler, et al. (Citation2011) used a measure of discrimination as a proxy measure of minority stress. Similar work using a more general measure of stress has not been done. Lack of longitudinal evidence using a validated measure of stress prevents the establishment of a clear link between stress and alcohol outcomes. Furthermore, research establishing the relationships between stress, drinking motives, and alcohol outcomes has only been conducted using adolescent and young adult samples who have different drinking motives than adults (Cooper, Citation1994; D’Aquino, et al., Citation2023). Previous research has also explored the impact of educational attainment and gender on alcohol outcomes (Parke et al., Citation2018; Rosoff et al., Citation2021) and the current study provided opportunity to explore these moderators on the relationships between stress and alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence, and alcohol harms.

2. Research aims and hypotheses

This study aimed to examine whether the relationships between stress and alcohol outcomes are mediated by drinking to cope in adults. Additionally, it aimed to explore whether these relationships were moderated by gender and educational attainment. The study explored these relationships cross-sectionally and across several time points longitudinally to provide robust support of a pathway between stress and alcohol outcomes. Furthermore, the current study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and Australian lockdowns (Karnon, Citation2020) allowing for an examination of stress and alcohol outcomes at the time of a powerful social stressor. Based on previous research in adolescent samples (Rice & Van Arsdale, Citation2010; Temmen & Crockett, Citation2020), it was hypothesised that drinking to cope would mediate the relationship between stress and alcohol outcomes including alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence, and alcohol harms both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Furthermore, based on research into relationships between alcohol outcomes and educational attainment (Rosoff, et al., Citation2021) and drinking motives and gender (Park & Levenson, Citation2002), stronger mediated relationships were expected for men and those with lower educational attainment.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

Following ethics approval (La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee: HEC20052), a convenience sample was recruited via Facebook and Instagram advertising. Recruitment occurred between 16 April 2020 and 11 May 2020 (T1) and involved asking prospective participants if they were interested in completing a survey on why Australians drink. Participants were incentivised with the chance to win a AUD50 supermarket voucher. Inclusion criteria for the current study included speaking English, living within Australia, being aged 25-65, and consuming alcohol at least monthly. Of the 2,630 prospective participants who clicked on the Facebook or Instagram advertisements, 885 (33.7%) did not meet the inclusion criteria, 304 (17.4%) were omitted for not completing any items for at least one of the primary measures in the study, and 852 (32.4%) did not take part in any of the follow up surveys. This left an initial sample at T1 of 589 participants. Of these 589 participants, 493, 487, and 311 participated in surveys at the second, third, and fourth time points (T2: 22 June 2020; T3: 7 October 2020; T4: 23 November 2020), respectively. The initial sample at T1 were predominantly middle aged (MAGE = 51.3), females (67.7%), with tertiary qualifications (64.9%), who had close to at risk AUDIT scores (MAUDIT = 15.5). By the final survey, 278 participants (47.2%) were lost to attrition. Participants who dropped out were younger (t(587) = −3.48, p < .001), had greater T1 DASS-stress scores (t(587) = 2.30, p = .02), and had greater drinking to cope scores (t(587) = 2.60, p = .01), but did not differ in AUDIT scores (t(1876) = 0.66, p = .88) at the p < .05 level. Demographics of participants at each survey time point are presented in .

Table 1. Participant demographics and mean AUDIT, DASS-Stress, and drinking to cope scores at the initial (T1), second (T2), third (T3), and fourth (T4) time points of the study.

3.2. Materials

3.2.1. Alcohol use disorders identification test

The ten item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al., Citation2001) contains three subscales which measure alcohol consumption (AUDIT-C; items one to three), alcohol dependence symptoms (AUDIT-Dependence; items four to six), and harmful alcohol use (AUDIT-Harms; items seven to ten). Participants with scores ≤7, 8–15, and ≥16 are deemed low, moderate, and high risk for developing a substance use disorder, respectively (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; Babor, et al., Citation2001). The AUDIT has good one-month test-retest reliability (0.84–0.85) and has excellent concurrent validity with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Substance Abuse Module (De Meneses-Gaya et al., Citation2009).

3.2.2. Depression anxiety and stress Scales (stress subscale)

Stress was measured using the seven items from the stress subscale of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales short form (DASS-21; Lovibond, Citation1996). The DASS-21 stress subscale has excellent internal consistency reliability (0.90) (Henry & Crawford, Citation2005) and strong correlation with the Perceived Stress Scale (Andreou et al., Citation2011) demonstrating construct validity.

3.2.3. Drinking motives Questionnaire for adults (coping subscale)

The Drinking Motives Questionnaire for Adults (DMQ-A; D’Aquino et al, Citation2023) is an adaption of the Drinking Motive Questionnaire Revised (DMQ-R), which is a measure of drinking motives in adolescents. The DMQ-A is a 20-item questionnaire with four response options (scores ranging from 0 to 4) measuring each of its five dimensions: enhancement, taste, social, coping, and confidence. Drinking to cope was measured by the average score from the four items on the coping subscale of the DMQ-A. D’Aquino, et al. (Citation2023) demonstrated drinking to cope to have good internal consistency (α = 0.89) and good convergent validity with the drinking to cope dimension on the DMQ-R, and in multiple regression demonstrated a moderate correlation with AUDIT-C (.30) and AUDIT-Harms (.42).

3.3. Procedure

Participants who clicked on the advertisement were directed to a Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Citation2020) online survey on their computer or mobile device which took approximately 10-15 minutes to complete. In the initial survey (T1: 16 April 2020), participants completed demographics questions on age, gender (male, female, non-binary, prefer not to say), education (less than year 12, year 12 equivalent, diploma or equivalent, and bachelor’s degree or higher), and a range of drinking motives including the drinking to cope subscale of the DMQ-A, the stress subscale of the DASS, and the AUDIT. Additionally, participants completed the AUDIT at three subsequent time points spaced 11 weeks apart (T2: 22 June 2020; T3: 7 October 2020; T4: 23 November 2020). These surveys were completed during the COVID-19 pandemic and some during the Australian stay at home orders of 2020 (Karnon, Citation2020). In the final survey (T4), participants completed drinking motive items which were included in the initial survey.

3.4. Data analysis

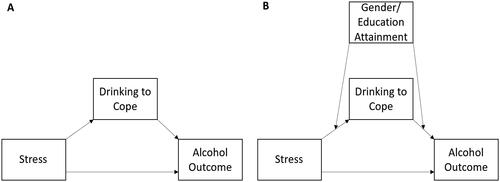

In order to determine whether drinking to cope mediated the stress and alcohol outcomes relationship, a mediation analysis was conducted. Hays SPSS process macro model 4 (Hayes (Citation2018); ) utilising 5000 bootstrap samples was used to determine whether drinking to cope mediated the relationships between stress measured at T1 and alcohol outcomes (AUDIT-C, AUDIT-Dependence, and AUDIT-Harms) measured at T1, T2, T3, and T4. These analyses were conducted with drinking to cope measured at both T1 and T4 for robustness. For drinking to cope measured at T1, there is a cross-sectional path from stress to drinking to cope and a longitudinal path from drinking to cope to the alcohol outcome. For drinking to cope measured at T4, there is a longitudinal path from stress to drinking to cope and a cross-sectional path from drinking to cope to the alcohol outcome. Based on recommendations by Rucker et al. (Citation2011), emphasis was placed on magnitude and significance of these relationships instead of whether the associations suggested partial or full mediation. Significant mediation was indicated by the confidence interval of the total indirect effect. If this confidence interval did not include zero, then the relationship was deemed significant.

Figure 1. (A) Drinking to cope mediating the stress and alcohol outcomes (alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence alcohol harms) relationship; (B) drinking to cope mediating the stress and alcohol outcomes relationship, with moderation by gender or education.

In order to determine whether gender and or education impacted the relationship between stress and alcohol outcomes as mediated by drinking to cope, a moderated mediation was conducted for any significant mediated relationship. Hays SPSS process macro model 58 (Hayes (Citation2018); ) utilising 5000 bootstrap samples was used to assess if the mediation of stress and alcohol outcome by drinking to cope was moderated by gender (male or female) and education (having a tertiary qualification or not having a tertiary qualification). Significant moderation was indicated by the confidence interval of index of moderated mediation. If the confidence interval of the moderated mediation did not include zero, then the gender and or education was deemed to significantly moderate the mediated relationship.

4. Results

4.1. Mediation by drinking to cope

Mediation analyses were conducted to test the hypotheses that drinking to cope mediated the relationship between stress and AUDIT-C, AUDIT-Harms, and AUDIT-Dependence (). First, these analyses were conducted with drinking to cope measured at T1. In this relationship there is a cross-sectional path from stress to drinking to cope and a longitudinal path from drinking to cope to the alcohol outcome. lists the total indirect effects of stress measured at T1 on AUDIT-C, AUDIT-Dependence, and AUDIT-Harms measured at T1, T2, T3, and T4, as mediated by DMQ-A drinking to cope measured at T1.

Table 2. Standardised Indirect effect (R2) of stress (measured at T1) on AUDIT-C subscales (measured at T1, T2, T3, and T4) as mediated by DMQ-a drinking to cope (measured at T1).

Drinking to cope at T1 was found to mediate the relationship between stress and AUDIT-C scores for all time points (T1, T2, T3, T4) with medium sized effects (Cohen, Citation1992). The direction of these relationships indicated that greater stress was associated with greater alcohol consumption via greater T1 drinking to cope. Drinking to cope was not found to mediate any relationships between stress and either AUDIT-Dependence or AUDIT-Harms.

Additionally, mediation analyses were conducted with drinking to cope measured at T4. In this relationship, there is a longitudinal path from stress to drinking to cope and a cross-sectional path from drinking to cope to alcohol outcome. lists indirect effects of stress measured at T1 on AUDIT-C, AUDIT-Dependence, and AUDIT-Harms measured at T4 as mediated by DMQ-A drinking to cope measured at T4.

Table 3. Standardised Indirect effect (R2) of stress (measured at T1) on alcohol outcome (measured T4) as mediated by DMQ-a drinking to cope (measured at T4).

Drinking to cope at T4 was found to mediate the relationship between stress and AUDIT-C scores at T4 with medium sized effect (Cohen, Citation1992), but not with AUDIT-Dependence or AUDIT-Harms scores at T4. The direction of this relationships indicated that greater stress was associated with greater alcohol consumption via greater T4 drinking to cope.

Overall, greater stress scores were consistently associated with greater alcohol consumption scores via greater drinking to cope scores. Conversely, stress was consistently not associated with alcohol dependence or alcohol harm symptom scores via drinking to cope.

4.2. Moderation by gender and education

To test whether gender and or education impacted the mediated relationship between stress and alcohol outcomes by drinking to cope, moderated mediation was conducted for significant mediated relationships in and . Thus, moderated mediation was conducted for the relationship between stress and AUDIT-C at all time points. These analyses were conducted with both gender and education as moderators and drinking to cope at both T1 and T4 as mediators. Gender was analysed as a dichotomous variable as either male or female and educational attainment was analysed as a dummy variable as either having a tertiary qualification or not having a tertiary qualification. The index of moderated mediation was used as the statistic to determine whether gender or education moderated the mediated relationships being explored. This statistic reported the difference in total indirect effect between male and females or those with a tertiary degree or those without a tertiary degree.

Moderated mediations were conducted with gender and education as moderators and drinking to cope measured at T1. In this relationship, there is a cross-sectional path from stress to drinking to cope moderated by either gender or education and a longitudinal path from drinking to cope to alcohol consumption with the same moderation. The index of moderated mediation for the moderating effects of gender and education on these relationship is provided in . Neither gender nor education were found to moderate any relationships between stress and AUDIT-C as mediated by drinking to cope at any time point.

Table 4. Index of moderated mediation for the relationship between stress and AUDIT-C (measured at T1, T2, T3, T4) as mediated by DMQ-a drinking to cope and moderated by gender and education.

Finally, the index of moderated mediation for the moderating effects of gender and education on the relationship between stress and AUDIT-C as mediated by drinking to cope measured at T4 are provided in . In these relationships, there is a longitudinal path from stress to drinking to cope moderated by either gender or education and a cross-sectional path from drinking to cope to alcohol consumption with the same moderation.

Table 5. Index of moderated mediation for gender (male or female) and education (tertiary qualification and no tertiary qualification) on the relationship between stress (measured at T1) and AUDIT-C (measured at T4) as mediated by DMQ-a drinking to cope (measured at T4).

Gender was found to significantly moderate the relationship between stress scores at T1 and AUDIT-C scores at T4 as mediated by drinking to cope at T4 with a medium sized effect (Cohen, Citation1992). The direction of the relationship suggests the mediating effects of drinking to cope were greater for men than women. Education was not found to moderate the relationship between stress at T1 and AUDIT-C at T4 as mediated by drinking to cope at T4.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the relationship between stress, drinking motives, and alcohol outcomes and the impact of gender and education on these relationships. It was hypothesised that drinking to cope would mediate the relationship between stress and alcohol consumption both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. This hypothesis was supported with a positive relationship between stress and alcohol consumption as mediated by drinking to cope for all cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Additionally, it was hypothesised that drinking to cope would mediate the relationship between stress and both alcohol dependence and alcohol harms. These hypotheses were not supported as no significant cross-sectional or longitudinal associations were found. It was also hypothesised that stronger relationships between stress and alcohol outcomes as mediated by drinking to cope would be found for men. This hypothesis was partially supported with stronger longitudinal associations between stress and alcohol consumption as mediated by drinking found for men when drinking to cope measured at T4, but not at T1. Lastly, it was hypothesised that stronger relationships between stress and alcohol outcomes as mediated by drinking to cope would be found for those with lower educational attainment. This hypothesis was not supported with no difference found in mediated relationships based on educational attainment.

Results of the current study suggest that there were some Australian adults during the 2020 COVID pandemic who developed patterns of heavier alcohol use as a means of coping with stress. Drinking to cope with stress underlies the premise of the drinking to cope subscales of the DMQ-A (Cooper, Citation1994; D’Aquino, et al., Citation2023). Most notably, consistent longitudinal results across each time point in the current study provide evidence of a pathway between stress and alcohol consumption among adults. While it is always possible for an extraneous variable to explain a correlation, the longitudinal mediation analyses with drinking to cope (measured at T1 and T4) helps establish a chain of events. Based on our model, individuals who are more stressed are more likely to develop increased motivation to drink alcohol to cope with their negative feelings. Subsequently, these individuals are more likely to go on to consume higher levels of alcohol than those who have lower levels of stress. However, this increased consumption is not linked with dependence or drinking harms. So, while this type of consumption has potential to cause longer term health issues, in the short term this extra consumption does not appear to lead to alcohol dependence or immediately harmful drinking consequences.

The cross-sectional mediation of stress and alcohol consumption by drinking to cope for adults in the current study supports prior research into young-adults (Temmen & Crockett, Citation2020). However, results in the current study differ from results found by both Rice & Van Arsdale (Citation2010) and Temmen & Crockett (Citation2020) who demonstrated that drinking to cope mediated the stress and alcohol harms cross-sectional relationship in their young-adult samples. Furthermore, lack of significant longitudinal mediation predicting AUDIT-Harms in the current study somewhat differs from research by Hatzenbuehler, et al. (Citation2011). Hatzenbuehler, et al. (Citation2011) found that drinking to cope mediated the longitudinal relationship between minority stress (measured as discrimination) and alcohol harms in their sample of young adults. However, this could simply reflect differences between chronic long-term stress and the more acute stress experienced during the pandemic. Alternatively, the pattern of alcohol harms resulting from drinking to cope due to increased stress may be more prevalent in young adults than a general adult population.

Interestingly, stronger mediating effects were found for men when predicting alcohol consumption at T4 when drinking to cope was measured at T4 but not when drinking to cope was measured at T1. This indicates that stress had a stronger effect on drinking to cope for men than women when drinking to cope was measured at a later time point. The mediation by drinking to cope measured at T1 may demonstrate a more immediate pathway from stress and mediation by drinking to cope measured at T4 may demonstrate the development of this mechanism over time. The difference in these results may suggest both men and women have a similar elevation in their drinking to cope behaviors as a result of stress, but for men, drinking more alcohol to cope with stress is more likely to continue over time. These findings support research demonstrating men as more likely to use alcohol as a means of regulating emotion and coping with stress (Nolen-Hoeksema, Citation2012). Furthermore, research suggests that the type of stress which leads to coping based drinking differs between genders. In particular, Temmen & Crockett (Citation2020) demonstrated that the mediation of the stress and excessive drinking relationship by drinking to cope in their sample was significant for men when in response to occupational stress and for women when in response to relationship stress. Thus, the type and strength of the relationship between stress and alcohol outcomes appears to somewhat differ between men and women.

A strength of the current study was the use of both cross-sectional and longitudinal mediation analyses of stress and alcohol consumption by drinking to cope. Furthermore, the timing of the study has allowed investigation into a coping response of heavier drinkers during a significant social stressor. However, the findings of the current study are not without their limitations. On average, participants in the current study had high AUDIT scores (an average score of 15.5 in the current study compared with an average score of 4.6 in a representative Australian sample (O’Brien et al., Citation2020)). Thus, participants in the current study may have more alcohol centric ways of coping with stress than the general population. High AUDIT scores are known to indicate risk for developing a substance use disorder (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; Bush et al., Citation1998) and individuals with high AUDIT scores are those who most commonly report to treatment for their alcohol use (Wallenstein, et al., Citation2007). So, results of the current study may provide valuable information on the mechanisms for alcohol use for those who may require treatment for their drinking. Furthermore, it is also possible that association between stress, drinking to cope, and alcohol outcomes was the result of an extraneous variable. For example, participants in the study may have comorbid depression or anxiety which may have contributed to the studied relationships. However, the moderate effect sizes found in the current study provides evidence that stress is likely to be a significant contributor to the drinking to cope-alcohol consumption pathway. Finally, attrition was a problem in the current study with many participants not completing all surveys. Baseline levels of stress and drinking to cope scores were higher among those who dropped out, potentially reducing effects of some analyses.

Previous research has demonstrated that a stronger relationship between stress and drinking to cope exists for those with less personal restraint (Corbin et al., Citation2013). Thus, future research could investigate whether personal restraint and impulsivity impact the mediated relationships explored in the current study and explore any potential interaction of this with gender. This could further elucidate target populations who are prone to drinking alcohol to cope with stress. Also, research demonstrates associations between depression and anxiety, and drinking to cope (Bravo & Pearson, Citation2017; Gonzalez & Halvorsen, Citation2021). Additionally, research has established longitudinal associations between onset of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders, and subsequent development of substance use disorders among those who drink to cope (Turner et al., Citation2018). Thus, future research could now investigate whether drinking to cope mediates the relationship between anxiety and depression, and drinking outcomes across time as was done with stress in the current study.

Overall, the current study addressed a gap in the literature by demonstrating a mechanism which leads to greater alcohol consumption in high-risk drinking adults. This expands upon research conducted on adolescents and young adults to a population of older adults who form the largest portion of those who seek treatment for their alcohol use (Wallenstein, et al., Citation2007). Results of the current study suggest that adults with higher levels of stress consumed more alcohol over time to cope with their stress than those with lower levels of stress. This contributes to the growing literature on the relationship between mental health and alcohol outcomes and provides insight into the impact social stressors can have on alcohol consumption.

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allan, N. P., Albanese, B. J., Norr, A. M., Zvolensky, M. J., & Schmidt, N. B. (2015). Effects of anxiety sensitivity on alcohol problems: Evaluating chained mediation through generalized anxiety, depression and drinking motives. Addiction, 110(2), 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12739

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th ed.).

- Andreou, E., Alexopoulos, E. C., Lionis, C., Varvogli, L., Gnardellis, C., Chrousos, G. P., & Darviri, C. (2011). Perceived stress scale: Reliability and validity study in Greece. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(8), 3287–3298. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8083287

- Anker, J. J., Kushner, M. G., Thuras, P., Menk, J., & Unruh, A. S. (2016). Drinking to cope with negative emotions moderates alcohol use disorder treatment response in patients with co-occurring anxiety disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 159, 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.031

- Babor, T., Higgins-Biddle, J. C., Saunders, J. B., & Monteiro, M. G. (2001). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary health care., Second Edition: World Health Organisation.

- Bravo, A. J., & Pearson, M. R. (2017). In the process of drinking to cope among college students: An examination of specific vs. global coping motives for depression and anxiety symptoms. Addictive Behaviors, 73, 94–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.001

- Bunker, N., Woods, C., Conway, J., Barker, R., & Usher, K. (2017). Patterns of ‘at‐home’ alcohol‐related injury presentations to emergency departments. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(1-2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13472

- Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789

- Cherpitel, C. J., Witbrodt, J., Korcha, R. A., Ye, Y., Monteiro, M. G., & Chou, P. (2019). Dose–response relationship of alcohol and injury cause: Effects of country‐level drinking pattern and alcohol policy. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(5), 850–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13986

- Cherpitel, C. J., Witbrodt, J., Ye, Y., & Korcha, R. (2018). A multi-level analysis of emergency department data on drinking patterns, alcohol policy and cause of injury in 28 countries. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 192, 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.033

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Cooper, M. L. (1994). Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117

- Corbin, W. R., Farmer, N. M., & Nolen-Hoekesma, S. (2013). Relations among stress, coping strategies, coping motives, alcohol consumption and related problems: A mediated moderation model. Addictive Behaviors, 38(4), 1912–1919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.005

- Crum, R. M., Mojtabai, R., Lazareck, S., Bolton, J. M., Robinson, J., Sareen, J., Green, K. M., Stuart, E. A., La Flair, L., Alvanzo, A. A. H., & Storr, C. L. (2013). A prospective assessment of reports of drinking to self-medicate mood symptoms with the incidence and persistence of alcohol dependence. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(7), 718–726. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1098

- D’Aquino, S., Callinan, S., Smit, K., Mojica-Perez, Y., & Kuntsche, E. (2023). Why do adults drink alcohol? Development and validation of a drinking motives questionnaire for adults (DMQ. A). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 37(3), 402–415. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000877

- De Meneses-Gaya, C., Zuardi, A. W., Loureiro, S. R., & Crippa, J. A. S. (2009). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): An updated systematic review of psychometric properties. Psychology & Neuroscience, 2(1), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.3922/j.psns.2009.1.12

- DeMartini, K. S., & Carey, K. B. (2011). The role of anxiety sensitivity and drinking motives in predicting alcohol use: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.10.001

- Duke, A. A., Smith, K. M. Z., Oberleitner, L. M. S., Westphal, A., & McKee, S. A. (2018). Alcohol, drugs, and violence: A meta-meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence, 8(2), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000106

- Fernandes-Jesus, M., Beccaria, F., Demant, J., Fleig, L., Menezes, I., Scholz, U., de Visser, R., & Cooke, R. (2016). Validation of the drinking motives questionnaire - revised in six european countries. Addictive Behaviors, 62, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.06.010

- Gonzalez, V. M., & Halvorsen, K. A. S. (2021). Mediational role of drinking to cope in the associations of depression and suicidal ideation with solitary drinking in adults seeking alcohol treatment. Substance Use & Misuse, 56(5), 588–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2021.1883661

- Grazioli, V. S., Bagge, C. L., Studer, J., Bertholet, N., Rougemont-Bücking, A., Mohler-Kuo, M., Daeppen, J.-B., & Gmel, G. (2018). Depressive symptoms, alcohol use and coping drinking motives: Examining various pathways to suicide attempts among young men. Journal of Affective Disorders, 232, 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.028

- Griswold, M. G., Fullman, N., Hawley, C., Arian, N., Zimsen, S. R. M., Tymeson, H. D., Venkateswaran, V., Tapp, A. D., Forouzanfar, M. H., Salama, J. S., Abate, K. H., Abate, D., Abay, S. M., Abbafati, C., Abdulkader, R. S., Abebe, Z., Aboyans, V., Abrar, M. M., Acharya, P., … Gakidou, E. (2018). Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet, 392(10152), 1015–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2

- Hashimoto, J. G., & Wiren, K. M. (2008). Neurotoxic consequences of chronic alcohol withdrawal: Expression profiling reveals importance of gender over withdrawal severity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(5), 1084–1096. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301494

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Corbin, W. R., & Fromme, K. (2011). Discrimination and alcohol-related problems in young adults: The mediating roles of coping motives, alcohol expectancies, and negative affect. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 115(3), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.002

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. (2nd ed.): The Guilford Press.

- Haynes, E. E., Strauss, C. V., Stuart, G. L., & Shorey, R. C. (2018). Drinking motives as a moderator of the relationship between dating violence victimization and alcohol problems. Violence against Women, 24(4), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801217698047

- Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(Pt 2), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657

- Karnon, J. (2020). A simple decision analysis of a mandatory lockdown response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 18(3), 329–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-020-00581-w

- Kushner, M. G., Thuras, P., Abrams, K., Brekke, M., & Stritar, L. (2001). Anxiety mediates the association between anxiety sensitivity and coping-related drinking motives in alcoholism treatment patients. Addictive Behaviors, 26(6), 869–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00240-4

- Lac, A., & Donaldson, C. (2016). Alcohol attitudes, motives, norms, and personality traits longitudinally classify nondrinkers, moderate drinkers, and binge drinkers using discriminant function analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 61, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.05.006

- Lac, A., & Donaldson, C. (2017). Comparing the predictive validity of the four-factor and five-factor (bifactor) measurement structures of the drinking motives questionnaire. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 181, 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.012

- Leonard, K. E., & Quigley, B. M. (2017). Thirty years of research show alcohol to be a cause of intimate partner violence: Future research needs to identify who to treat and how to treat them. Drug and Alcohol Review, 36(1), 7–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12434

- Lorenz, K., & Ullman, S. E. (2016). Alcohol and sexual assault victimization: Research findings and future directions. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 31, 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.08.001

- Lovibond, S. H. (1996). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation of Australia.

- Lyvers, M., Hanigan, C., & Thorberg, F. A. (2018). Social interaction anxiety, alexithymia, and drinking motives in australian university students. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 50(5), 402–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2018.1517228

- Maphisa, J., & Young, C. (2018). Risk of alcohol use disorder among South African university students: The role of drinking motives. Addictive Behaviors, 82, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.016

- Martin, J., Ferreira, J., Haase, R., Martins, J., & Coelho, M. (2016). Validation of the drinking motives questionnaire-revised across us and portuguese college students. Addictive Behaviors, 60, 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.030

- Mohr, C. D., McCabe, C. T., Haverly, S. N., Hammer, L. B., & Carlson, K. F. (2018). Drinking motives and alcohol use: The SERVe study of U.S. current and former service members. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(1), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2018.79.79

- Mosher Ruiz, S., Oscar-Berman, M., Kemppainen, M. I., Valmas, M. M., & Sawyer, K. S. (2017). Associations between personality and drinking motives among abstinent adult alcoholic men and women. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), 52(4), 496–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agx016

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology: The Role of Gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8(1), 161–187. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109

- O’Brien, H., Callinan, S., Livingston, M., Doyle, J. S., & Dietze, P. M. (2020). Population patterns in Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores in the Australian population 2007–2016. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 44(6), 462–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13043

- Park, C. L., & Levenson, M. R. (2002). Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems and coping processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(4), 486–497. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486

- Parke, H., Michalska, M., Russell, A., Moss, A. C., Holdsworth, C., Ling, J., & Larsen, J. (2018). Understanding drinking among midlife men in the United Kingdom: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 8, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2018.08.001

- Qualtrics. (2020). Qualtrics. Provo, Utah, USA. Retrieved from https://www.qualtrics.com

- Rice, K. G., & Van Arsdale, A. C. (2010). Perfectionism, perceived stress, drinking to cope, and alcohol-related problems among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(4), 439–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020221

- Robinson, J., Sareen, J., Cox, B. J., & Bolton, J. (2009). Self-medication of anxiety disorders with alcohol and drugs: Results from a nationally representative sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.03.013

- Rosoff, D. B., Clarke, T.-K., Adams, M. J., McIntosh, A. M., Davey Smith, G., Jung, J., & Lohoff, F. W. (2021). Educational attainment impacts drinking behaviors and risk for alcohol dependence: Results from a two-sample Mendelian randomization study with ∼780,000 participants. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(4), 1119–1132. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0535-9

- Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations: Mediation analysis in social psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

- Sun, L., Windle, M., & Thompson, N. J. (2015). An exploration of the four-factor structure of the drinking motives questionnaire-revised among undergraduate students in china. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(12), 1590–1598. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2015.1027924

- Temmen, C. D., & Crockett, L. J. (2020). Relations of stress and drinking motives to young adult alcohol misuse: Variations by gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(4), 907–920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01144-6

- Turner, S., Mota, N., Bolton, J., & Sareen, J. (2018). Self‐medication with alcohol or drugs for mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review of the epidemiological literature. Depression and Anxiety, 35(9), 851–860. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22771

- Villarosa, M. C., Messer, M. A., Madson, M. B., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2018). Depressive symptoms and drinking outcomes: The mediating role of drinking motives and protective behavioral strategies among college students. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(1), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1327974

- Wallenstein, G. V., Pigeon, S., Kopans, B., Jacobs, D. G., & Aseltine, R. (2007). Results of national alcohol screening day: College demographics, clinical characteristics, and comparison with online screening. Journal of American College Health : J of ACH, 55(6), 341–350. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.55.6.341-350

- Wilhite, E. R., & Fromme, K. (2015). Alcohol-induced blackouts and other negative outcomes during the transition out of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(4), 516–524. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2015.76.516