Abstract

Introduction

Long-term use of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) might lead to distressing withdrawal symptoms following cessation. This paper aims to share challenges in recruiting patients to a pilot intervention study with parallel substance use disorder (SUD) treatment and to explore barriers to participation among AAS forum members.

Methods

Eligible AAS-dependent men were recruited to receive hormone therapy for 16 weeks, and exclusion reasons were registered. Audience engagement from social media advertisements was measured. Information about the study was posted in an AAS online forum, and discussion among forum members was thematically analyzed.

Results

Twelve of 81 potential participants were included, whereas ten completed the intervention. Participants were excluded due to residency outside the study area, illicit substance use or severe medical conditions. Challenges in recruitment were linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, funding and advertisements on social media. AAS forum members suggested modifications to the intervention, were skeptical to the SUD-patient requirement, feared prosecution or other negative outcomes and/or preferred to seek online advice on self-initiated testosterone replacement therapy or post cycle therapy.

Conclusion

AAS-related online recommendations among peers, criminalized AAS use setting and obligatory SUD treatment might have affected recruitment. Based on lessons learned, recommendations for future similar studies are presented.

Introduction

Anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) constitute a sub-group of image and performance enhancing drugs (IPEDs), designed to mimic the effects of endogenous testosterone (Kicman, Citation2008). In recent decades, the use of AAS has become increasingly more common in the general population, especially among young men, to boost muscle strength and to improve aesthetics and performance (Brennan et al., Citation2017). However, AAS use is associated with multiple bodily harms, including endocrine, cardiovascular and metabolic disturbances (Horwitz et al., Citation2019; Melsom et al., Citation2022; Pope et al., Citation2014; Rasmussen, Schou, Madsen, Selmer, Johansen, Hovind, et al., Citation2018; Rasmussen, Schou, Madsen, Selmer, Johansen, Ulriksen, et al., Citation2018; Rasmussen et al., Citation2017), as well as reduced cognition, risk behavior and other substance use (Bjornebekk et al., Citation2019; Havnes et al., Citation2020; Zahnow et al., Citation2018). AAS-induced hypogonadism (ASIH), which is caused by AAS’ long term feedback inhibition on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, commonly leads to distressing withdrawal symptoms among those who try to cease use (Botman et al., Citation2023; de Ronde & Smit, Citation2020; Rahnema et al., Citation2014). Symptoms of ASIH include fatigue, reduced libido, erectile dysfunction and depression, which might persist for months to years following AAS cessation or, for some, even be irreversible (Coward et al., Citation2013; Kanayama et al., Citation2015; Rasmussen et al., Citation2016). Resumed and sustained AAS use may alleviate these distressing withdrawal symptoms. This is a central mechanism in the development of AAS dependence, which about one in three of people who use AAS are reported to develop (Skauen et al., Citation2023).

Despite AAS-related health problems, which include dependence and withdrawal symptoms, treatment-seeking among people who use AAS is found to be low (Amaral et al., Citation2022; Havnes et al., Citation2019; Pope et al., Citation2004; Zahnow et al., Citation2017). Reported reasons for not seeking treatment is not considering experienced AAS-related side effects to be of treatment demanding nature (Henriksen et al., Citation2023; Zahnow et al., Citation2017), having the perception that health professionals lack knowledge about AAS (Bonnecaze et al., Citation2020; Zahnow et al., Citation2017), fear of stigmatization (Yu et al., Citation2015) or negative sanctions from health professionals (Havnes et al., Citation2019) and not having access to desired hormonal treatment to alleviate withdrawal symptoms after cessation (Harvey et al., Citation2019; Havnes & Skogheim, Citation2020; Underwood et al., Citation2021). People who use AAS tend to seek information from peers and online on how to use AAS and self-monitor own health (Andreasson & Henning, Citation2022; Bojsen-Moller & Christiansen, Citation2010). This often involves seeking and giving advice on how to self-medicate at the end of an AAS cycle to restore endogenous testosterone production (Tighe et al., Citation2017), a practice termed post cycle therapy (PCT) (Griffiths et al., Citation2017; Rahnema et al., Citation2014; Smit & de Ronde, Citation2018). The non-prescribed prescription drugs most commonly used for this purpose are approved for the treatment of infertility and breast cancer in women and include selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs, also called anti-estrogens), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and aromatase inhibitors (Bonnecaze et al., Citation2021). PCT is not scientifically proven to be an effective treatment for ASIH, despite being easily accessible and frequently used after an AAS cycle (Westerman et al., Citation2016).

Previous literature on treatments for AAS-related physical and mental harms is limited and consists mainly of case reports (Bates et al., Citation2019). Even though the lack of evidence-based guidance might be challenging in clinical settings, there have been attempts at designing general guidelines for treating ASIH (Botman et al., Citation2023). However, there is still a knowledge gap regarding the efficacy and safety of medical interventions targeting AAS withdrawal symptoms, dependence and support during and after cessation. The Oslo University Hospital (OUH) has 15 years of experience providing substance use disorder (SUD) treatment to people with a desire to cease AAS use. SUD treatment for this patient group involves alleviating withdrawal symptoms by providing psychosocial support, prescribing psychopharmacological medication and addressing co-occurring mental and physical health problems (Havnes et al., Citation2019; Kanayama et al., Citation2010; Pope et al., Citation2010). However, SUD treatment does not directly target ASIH and the withdrawal symptoms associated with low endogenous testosterone production. Consequently, the Department of Endocrinology and the Department of Addiction Treatments at OUH initiated a collaborative pilot study to investigate the effect of hormone therapy for men in SUD treatment discontinuing AAS use, as a potential supplement to the already existing SUD treatment.

People who use AAS may be seen as a socially disadvantaged hard-to-reach group as use is associated with social and economic challenges including reports of troubled childhood (Ganson et al., Citation2021), high unemployment rates (Ljungdahl et al., Citation2019), concurrent substance use (Havnes et al., Citation2020) and higher crime records (Lundholm et al., Citation2015). In addition to the barriers to seek treatment described above, people who use AAS may also have barriers to recruitment and participation in health research (Bonevski et al., Citation2014). As participants in this hormone therapy intervention were required to have patient status in SUD treatment, it is important to explore and understand potential barriers to engagement in clinical research participation and to healthcare treatment-seeking among people who use AAS. The aims of this paper are to describe the recruitment process and the related challenges that were experienced in this intervention study and to generate insight into potential reasons that those invited to join the study did not participate. We will use a dual approach: First, by sharing recruitment experiences, and secondly, to analyze online engagement among members from an AAS community forum on the intended hormone therapy intervention with obligatory SUD treatment. Finally, we will present lessons learned and future recommendations, which could be of relevance for future intervention studies seeking to address the treatment needs of people who use AAS.

Methods

Setting

The Norwegian healthcare system is publicly funded, as all residents are covered by the National Insurance Scheme (World Health Organization. Regional Office for et al., Citation2013). Every citizen is entitled to a general practitioner that may refer their patients to specialized treatment at publicly funded hospitals. Even though most costs related to public health services is covered, patients would still normally pay a small user fee for each healthcare visit. Patients are then given a healthcare exemption card if they reach a maximum amount in user fees for treatment services per year (present maximum user fee is NOK 3040 ≈ 300 USD) (The Norwegian Health Economics Administration, Citation2023).

Use and possession of AAS and other IPEDs became illegal in Norway through a legislation change in 2013. At the same time, as one of few countries, people who use AAS in Norway were given rights to specialized psychosocial treatment for SUDs in the public healthcare system. The SUD treatment program involves biopsychosocial treatment of people with current or previous AAS use, and professional follow-up on related socioeconomically issues. The National Steroid Project was created by OUH in 2014 to provide a free and anonymous helpline for people who use AAS and their next of kin, as well as inform health professionals and the Norwegian public on associated health risks, treatment options, and economic, social or legal consequences related to AAS use (Havnes et al., Citation2019).

The pilot study

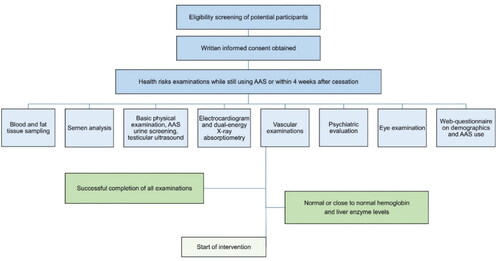

This paper describes the challenges in recruitment for the single-site, open longitudinal proof of concept pilot study Health risks and off-label use of clomiphene citrate to Treat Anabolic-androgenic Steroid (AAS) induced Hypogonadism upon cessation among men – a pilot study (CloTASH) at OUH. The pilot study tested a modified version of a 16 weeks treatment model with the SERM clomiphene citrate (CC, clomiphene or Clomid), as proposed by Rahnema et al. (Citation2014), with 25 mg CC given every second day for 16 consecutive weeks, transdermal testosterone applied daily for the first four weeks and hCG injections added in cases of poor endogenous hormone response. The study aimed to include 25–30 men referred to SUD treatment with AAS dependence and a desire to end AAS use permanently. All participants who received the intervention participated in thorough physical and mental health examinations prior to starting treatment, while still using AAS or within four weeks of cessation. For a full list of examinations at the time of inclusion, see . Participants were monitored with self-report questionnaires every two weeks and physical examinations every four weeks throughout the 16 week intervention. They had follow-ups at six and 12 months to investigate whether the potential health risks that were identified at the time of inclusion were reversed. When planning the pilot study, the research group established a user panel consisting of five persons with previous AAS use and experience from either SUD or psychiatric treatment. A systematic review investigating recruitment of hard-to-reach groups found that community involvement in the planning process for clinical intervention studies is important to make both study protocols and recruitment more feasible (Bonevski et al., Citation2014). The research questions, intervention, clinical examinations and web questionnaires for the pilot study were discussed in workshops with the user panel, who strongly approved of and supported the study. Persons with user experience were also involved in the development of social media advertisements.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included men who used AAS and wished to permanently quit, above 18 years of age, with consent capacity, fulfilling criteria for AAS dependence according to the DSM-IV (Pope et al., Citation2010), and with continuous use for the six months prior to the intervention. In addition, requirements for initiating the intervention included serum-testosterone levels <25 nmol/L (reference range 9–30), hemoglobin levels <18 g/dl (13.4–17), alanine transaminase <210 U/L (10–70) and aspartate transaminase <135 U/L (15–45), i.e. <3x upper limit for normal reference range for liver transaminases (liver enzymes). All participants were required to participate in follow-ups at the SUD outpatient clinic during the intervention. Residency in or nearby Oslo was also required for study participation. Exclusion criteria were severe mental illness (i.e. current or previous severe depression with suicidal ideation or attempts, bipolar disorder or psychosis), severe cardiovascular disease (i.e. previous thromboembolic events, myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest), prescribed testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) for hypogonadism from causes other than AAS use, ongoing non-prescribed use of other hormones, illicit substance use or previous adverse effects from clomiphene.

Recruitment procedure

The National Steroid Project at OUH was the primary contributor to participant recruitment. To reach out to men who use AAS, the following recruitment strategies, listed chronologically, were continuously assessed and improved in order to be as effective as possible: Advertisements containing study information were initially posted on the OUH website, on social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok), in an online AAS forum and in several online fitness forums. Audience engagement with the social media advertisements was measured in reach, representing the number of unique users who saw the advertisement, and clicks, representing the number of people who clicked on the advertisement and were redirected to the official study website at OUH. The study was also advertised through flyers and posters in over 35 gyms and fitness centers in and around Oslo, and a degree of snowball sampling effect was expected. The Norwegian School of Sport Sciences and one of the Norwegian gym chains with the most members, Fresh Fitness Norway, broadcasted the study several times on their social media pages. The National Steroid Project sent out letters with study information to every general practitioner located in Oslo and in selected areas of Eastern Norway. Several lectures about the ongoing clinical study and AAS-related health risks were held for relevant healthcare professionals in Norway throughout 2021 and 2022, including SUD clinicians at OUH, who were invited to refer male AAS patients already undergoing SUD treatment directly to the study researchers responsible for inclusion. Lastly, study researchers were interviewed in Norwegian newspapers to spread information about the study.

Qualitative analysis of a discussion about the study in an online AAS forum

When information about the study was shared in an online forum for people who use AAS, with the intention of making the study known and to recruit participants, it generated a discussion among 20 forum members, with a range of 1–12 posts each. The subjects of discussion included the choice of hormone therapy intervention, criminalization of AAS use and how the study was organized within the SUD treatment facilities. To gain insight into potential barriers to participate in the pilot study, we were inspired by early observational netnography as to thematically analyze the content of a single online forum thread, as ‘netnography is not defined in relation to the size of a dataset, but to its depth’ (Kozinets, Citation2020). Kozinets describe four basic steps which include ‘(1) research inquiry (explore potential barriers to participate in the study), (2) data collection (one single forum thread where information about the study was posted and discussed by forum members), (3) data analysis and 4) research communication’. Step 3, the data analysis, was conducted as a thematic analysis by first and last author who read and reread the posts several times. The posts were then individually coded with a focus on potential barriers to participate in the pilot study. First and last author jointly discussed coding and themes until consensus, resulting in three main themes: (I) Suggesting modifications to the intervention, (II) Fear of negative outcomes, and (III) Proposed alternatives. Step 4 (research communication) involved ethical considerations as described in the Ethics section below, and relevant quotes were selected to exemplify the themes and sub-themes.

Table 2. The themes and sub-themes that were generated during the thematic analysis of the online discussion among AAS forum members in response to the pilot study advertisement.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the pilot study was obtained from the Norwegian Regional Committees for Medical Research Ethics (33872), the Norwegian Medicines Agency (21/18081-9) and the Data Protection Officer at Oslo University Hospital (20/27593). The research was performed in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation in the intervention, all eligible participants received oral and written information about the study. Written informed consent was provided by all participants.

All study examinations, medication and follow-ups were provided free of charge, but travel expenses were not reimbursed. As patients of the public SUD treatment program at OUH, participants were required to pay for each visit at the outpatient clinic. The initial plan for the pilot project was to offer optional SUD treatment to those participants who were in need of it either during or after the 16 week long intervention. However, the clinical administration at the outpatient department at OUH had ethical objections to this approach and regarded mandatory SUD treatment as a necessary support for all study participants. This was based on many years of experience with the patient group and an understanding that some patients with a desire to permanently cease AAS use develop severe depression and suicidal ideation shortly following cessation (Lindqvist et al., Citation2014; Thiblin et al., Citation1999). In addition, as this intervention had not previously been scientifically tested, we did not know whether it would have an effect on men with long-term AAS use.

All participants could withdraw from the study at any stage prior to data publication, without any consequence for their access to psychosocial treatment at the outpatient SUD clinic. Any pathological finding at the time of inclusion or during intervention was evaluated by the research physicians and investigated further clinically when indicated. All participants were insured against potential adverse medical events related to the use of study drugs, through the principal investigator’s membership in the Norwegian Drug Liability Association.

To ensure ethical standards of online research and to secure the anonymity of online forum members, we excluded sensitive or potentially identifiable information from the material quoted and discussed. A research guide for internet research ethics (The National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities, Citation2019) was reviewed and discussed with the Data Protection Officer at Oslo University Hospital prior to publication:

Distinction between public and private: The AAS online forum consists of many thousand members. The overview of different threads in the forum is openly available to all, but it is necessary to create a user account with a password in order to read the posts. The forum members from the thread whose posts we analyzed did not reveal information about personal identity.

Concerns for vulnerable groups: We did not consider the online forum users to be a vulnerable group.

Responsibility to inform and obtain consent: It was not possible to obtain consent as forum users cannot interact with each other through direct messages, and members use pseudonyms as usernames, thus the real identity of each online member was not known. The researcher who posted the study advertisement in the forum did not participate in an exchange of opinions nor in the active discussion with the intent to ‘provoke’ a reaction from the forum users. The researcher responded to direct questions about healthcare personnel’s obligation to report AAS use. One forum member sent an e-mail to the principal investigator regarding the study protocol and subsequently reposted the response from the researcher in the thread online for continued discussion among forum members.

Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured by not stating the name of the forum, replacing user names with pseudonyms, avoiding sensitive information and translating quotes from Norwegian to English.

Sharing of data: Data will not be shared.

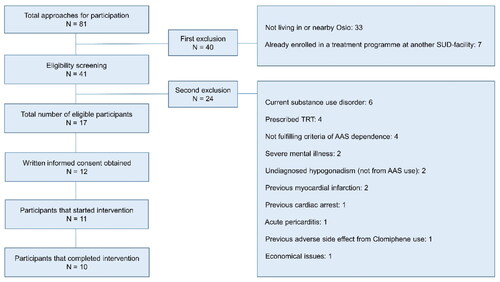

Results – challenges in recruitment

The recruitment period lasted for one year, 1 January 2022–31 December 2022. Overall, 17 of 81 men were considered eligible for study participation, but five reconsidered and chose not to participate without further explanation. The remaining 12 men provided written informed consent to participate. One of these participants withdrew from the study before starting the intervention. Another participant dropped out of the study in the middle of intervention and restarted AAS use due to distressing withdrawal symptoms. The 10 remaining participants completed the intervention according to the study protocol. The recruitment process in this pilot proved challenging for several reasons that will be discussed in the next sections, and which ultimately resulted in a lower number of eligible participants than intended (25–30). However, the study had already been postponed due to COVID-19 and, due to funding limitations, the recruitment period could not be extended.

Advertisements through social media

Information about the study initially reached men who use AAS through the National Steroid Project’s direct helpline (Havnes et al., Citation2019) and through snowball sampling. However, people who use AAS have previously shown to be a hard-to-reach group (Bonnecaze et al., Citation2020; Harvey et al., Citation2019; Richardson & Antonopoulos, Citation2019; Zahnow et al., Citation2017), and recruitment during the first months was unprogressive, despite following careful advice from user representatives connected to the study. All recruitment channels were made linguistically appropriate for the intended receivers, as this previously has shown to be of importance to reach socioeconomically disadvantaged groups (Bonevski et al., Citation2014). However, spreading information about this study through posters and flyers distributed at local gyms and the hospital’s website, did not result in more participants. In addition, the Norwegian gym culture was heavily affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and many gyms in Oslo were entirely or partly closed through the years of 2020–2022. It was therefore anticipated that people who use AAS might turn to social media and online platforms for connecting with peers during the pandemic. Hence, we approached various social media platforms with paid advertisements and posted information about the study on an AAS online forum. Paid advertisements on social media appeared to be an efficient way of reaching out to many in a short time span, as depicted by the amount of reach and clicks gained by the paid study advertisements, see . TikTok was the social media platform that generated the most reach and clicks, followed by Snapchat and Meta (Facebook and Instagram). However, some of our advertisements on social media (Meta) were blocked due to violation of community guidelines: (1) the term ‘anabolic steroid’ could provoke suspicion of illegal sale of drugs via its services, and (2) a photo of a bare, muscular male torso was not accepted. This was solved through time consuming negotiations, as well as the use of wider terms, such as ‘performance enhancing substances’ and neutral illustrations.

Table 1. Audience engagement with paid advertisements on social media (Meta, Snapchat and TikTok) measured in Numbers of reach and clicks.

Difficulty reaching the target population and recruiting within the study area

Although most advertisements were intended to recruit participants from a specific geographical area (the capital Oslo), the reach was widespread and many men with AAS use but with residency in other parts of the country showed interest in participation. However, those living non-commutable distances from Oslo could not be included, as visits to the study centers and SUD outpatient clinic throughout the intervention period would be impractical. A total of 81 men who used AAS expressed interest in participation, mostly through direct contact with the National Steroid Project on email or telephone, although some also contacted the other researchers directly. During the initial round of eligibility screening, 33 potential participants were excluded due to residing a non-commutable distance from Oslo. Moreover, seven men were excluded due to being enrolled in SUD treatment at facilities other than OUH. See for more details.

Exclusion due to safety concerns

The remaining 41 men went through a second round of inclusion and exclusion screening, where a final decision on eligibility was jointly made between the study physicians, and 24 men were mainly excluded due to safety concerns. Six potential participants who reported substance use problems were excluded to avoid potential confounding of study data containing physical and mental health measures, and given the risk of unforeseen interactions with clomiphene, transdermal testosterone and hCG. Four men with serious cardiovascular disease were excluded since thromboembolic events have been reported in isolated cases of infertile but otherwise young and healthy men treated with off-label clomiphene (Choi et al., Citation2021; Zahid et al., Citation2016). Two men were excluded based on medical history that indicated undiagnosed primary hypogonadism due to testicular failure and not due to previous AAS use. Finally, two men were excluded due to severe mental illness and one was excluded from participation due to previous visual disturbance related to clomiphene use.

Economic barriers

The medication and all of the examinations and follow-ups in the study were provided free of charge. However, participants had to cover the cost of transport to and from OUH every fourth week during the intervention. Additionally, most participants were not entitled to a healthcare exemption card, and thus had to pay a user fee for each visit at the outpatient clinic as patients of the SUD treatment program. This might have discouraged persons with economic challenges, which was the case for one participant. Of notice, economic incentives has previously proven to be effective to increase retention rates and satisfaction levels among participants with substance use in longitudinal designed studies (Festinger et al., Citation2005, Citation2008).

Recruitment-relevant insights from members of an AAS forum

Several forum members expressed positive attitudes towards the pilot study and saw it as a sign of changed attitude towards people who use AAS. Several had a desire to cease AAS use,Footnote1 but expressed no intention to participate in the study. Some suggested modifications to the intervention, some feared negative outcomes of participation and some who wished to cease AAS use proposed self-treatment as alternative to study participation, see .

Suggested modifications to the intervention

The choice of medical intervention was discussed among forum members. ScienceGuy questioned why the anti-estrogen Nolvadex was not used instead of CC. Another forum member, Diplomate, answered that Nolvadex could influence other hormone levels negatively and lower the bioavailability of testosterone, and that more research has been done on CC, potentially facilitating ethical approval. He also stated that CC has a ‘nicer profile when the goal is to increase the testosterone level without disturbing much else’.

ScienceGuy sent emails to the principal investigator with questions about the choice of medication, dose and scientific rationale for the chosen dose. He received a response that referred to the publication by Rahnema et al.(Rahnema et al., Citation2014) describing the treatment model, as well as justification for the dose based on recent scientific reviews, which he copied and posted online. There were several posts where scientific knowledge and excerpts from published papers were shared among the forum users. The following discussion took place between ScienceGuy and Diplomate, who had slightly different opinions:

ScienceGuy: I don’t find any scientific justification for choosing Clomid 25mg eod [every other day] in the Rahnema paper.

Diplomate: Earlier cohort studies have used 25mg every day, so 25 mg eod seems reasonable, I think. It is better to try out lower doses prior to experimenting with higher doses. Dose-response of anti-estrogens has a steep effect curve, so there is a lot to gain by using low doses.

ScienceGuy: Yes, perhaps. Microdosing of 25–50mg eod would be more reasonable for studies lasting longer – 1, 2 or 3 years. For short-term studies lasting 1, 3 or 6 months 50–100mg ed [every day] would be more reasonable.

Fear of negative outcomes

Some forum members feared that participation in the study would result in negative outcomes, such as being reported by health professionals to the police for using AAS, not achieving the desired effect from the intervention, being offered psychopharmacological agents instead of TRT or individual health risks.

The online community questioned confidentiality and data protection in the research project. It was suspected that the research project could be a setup by the police to catch people who use AAS:

Skeptical: There are examples where users have been in similar projects, where they have been exposed to a set-up to be caught by the police. I am skeptical until I see proof of the opposite. Everyone else should be as well.

Diplomate: Police provocation is not allowed in Norway – such as a set-up or provoking criminal acts to arrest somebody, so there is no danger here.[.] It is common practice that you sign a consent declaration before the project starts, where your rights are described. This is legally binding, meaning that, if the hospital goes behind your back and gives information about you to the police, it will have legal consequences for them [the researchers]. But this will not happen, the hospital is interested in doing serious research, that’s it.

Supporter: [.] To set up a ‘fake’ research project to catch 3 gym rats like me who use AAS for cosmetic reasons and commit a completely harmless crime with no victim, seems to be a very strange way of using resources. Then it would be cheaper and give more results to simply have a police raid at the nearest gym at 8 at night.

LegalTRT: After reading the «handbook» I get the impression that users of AAS are placed in the same category as drug addicts and gaming addicts, that they have a disease that needs treatment, and that the only solution is to quit all performance enhancing substances forever. It says that the patient should not be offered any form of PCT (nolvadex, clomid, HCG). Furthermore, one should not be offered addictive substances for anxiety or sleep problems, but rather C-drugs, such as antidepressants, antihistamines and antipsychotics. All in all, I have the impression that it is really dangerous to ask for help in the health service for AAS use. In reality you are not offered any real help as long as TRT is not the first choice. When you are threatened with losing your driver’s license or being reported to the child welfare services, it’s just way too stupid.

LegalTRT: Is it possible that the rest of the world sees that messing with PCT is nonsense when good treatment already exists? Whether it is [testosterone] gel, nebido [injectable testosterone depot formulation] or test cyp [testosterone cypionate]? That HAS been researched and is being used all over the world? No, to hell with it, let’s try PCT and give them medication so they will not feel too bad when the testosterone has left the body.

Do you have sleep problems? Here, take some Quetiapin. Oh dear, do you get depressed? Here, take some Cipralex, then you’ll feel better.

LegalTRT: ‘Do you struggle to find participants? Perhaps you should offer some cash to encourage people to participate. It doesn’t come without risk to take a non-approved substance like Clomid/clomiphene in a way it isn’t approved. If you are going to risk life and health, you must get something in return’.

Diplomate: ‘Offer some cash? They offer close medical follow-up for persons who desire to quit AAS use with a substance that most in this forum are already familiar with. Completely free of charge. That’s quite a good payment, if you ask me. I think several in here should cool down.’

Proposed alternatives

Forum members who intended to cease use with either supra-physiologic AAS or self-initiated TRT saw better alternatives to participation in the research project. One member stated that the medical examinations provided by the research project could easily be accessed through other health services instead:

LegalTRT: Those who care can get it checked out by themselves.

Try2Quit: I will try to get off again. I’m on TRT and am not doing cycles anymore. I have used HCG during TRT for several years, and I have gotten prescribed Enklomifen instead of Clomid.

LegalTRT: If you find the right physician, you get the right treatment. I know about one who prescribes testosterone almost automatically if the levels are under 12 nmol/l. But if you don’t find one, you can set up your own TRT like most in here do.

StableTesto: Not the least, it is demanding [to seek treatment] due to a shockingly low level of knowledge in the public health system regarding both steroids and hormone therapy. Even among endocrinologists who are supposed to be the experts, outdated ideas and standards are used. AND very little, if any, consideration is given to the mental effects of quitting testosterone. [.] It is clear that we can’t trust [the knowledge of] public physicians. So it has to be ourselves, or private physicians so expensive that the first hour [of consultation] costs more than several years of underground testosterone consumption. So, we are left to self-medicate if we want a healthy, stable level of testosterone instead of yo-yoing with the hormonal system.

Broscience: To be honest, I think we who are users on the forum have a better chance to help people to quit AAS than the health services and the [research] project. We have the most knowledge and experience. We know what kind of protocols can work, and we can do «everything» that may help without superintendence. Unfortunately.

ForumTrust: I trust Diplomate and the other guys here on the forum more than those tired physicians…[.] I have gotten so much help from this forum that a physician could never have provided.

LegalTRT: Like me, I have used steroids for more than 10 years. To follow a protocol for a year to regain testosterone production is most probably just nonsense and something I would never expose myself to when I know that there are legal, good medications that offer what I need in a good, effective and safe way.[.] Is it strange that people do not want to participate in projects like this? No. Is it strange that we self-medicate? No. Do we want it like this? No.

What we users would need is a study where you [the researchers] investigate the effect of getting active and former steroid users (with too low level of testosterone) off self-medication and on legal TRT with access to gel, nebido and test cyp. For us who have used, or abused as you [the researchers] see it, steroids for many years have, as I see it, little use for your project. You should focus on our group [people who self-medicate], because the majority who need help the most belong to our group. Most people who start [with steroids] use for many years, the rest stop after first or second cycle.

Discussion

In this proof of concept pilot study providing off-label hormone therapy to men with a desire to cease continuous AAS use, we aimed to include 25–30 men with a desire to cease continuous, long-term AAS use. However, we experienced a variety of challenges in recruitment of research participants, many of which could have been solved if addressed earlier during the planning of the study. Even though 81 men expressed interest in participation, 40 were excluded early in the process due to residency in other parts of Norway and 24 were excluded mainly due to safety reasons such as concurrent SUD, or history of severe cardiovascular disease or mental disorder. In the end, only ten men who were found eligible for participation successfully completed the study intervention.

Exclusion challenges

The decision to exclude participants due to safety concerns can be ethically challenging, given the physical and mental health risks posed by continued AAS use (Horwitz et al., Citation2019; Piacentino et al., Citation2015). However, there is a knowledge gap regarding the effectiveness and safety of various PCT models for treating ASIH (Bates et al., Citation2019). Even though clomiphene has previously shown to be safe and effective for treating hypogonadism from causes other than AAS use (Krzastek et al., Citation2019; Moskovic et al., Citation2012; Taylor & Levine, Citation2010; Wheeler et al., Citation2019), it has not yet been used off-label in clinical research to treat ASIH. The more common side effects of clomiphene comprise headache, dizziness, mood changes, breast tenderness and gastrointestinal symptoms (Choi et al., Citation2005; Wheeler et al., Citation2019), while rarer and more serious adverse effects have been reported, which involve vision changes (e.g. blurred vision; Purvin, Citation1995), liver damage (Zhang et al., Citation2018) and thromboembolic events (Solipuram et al., Citation2021). Serious adverse effects from previous use of clomiphene should therefore be an exclusion criterion for study participation.

Obligatory SUD treatment

Norway is one of few countries where AAS use has been included in the drug policy, from which follows that AAS use and possession is criminalized and that people who use AAS are entitled to SUD treatment. However, fear of being reported to the police might serve as a barrier to participating in SUD treatment. Five men who were deemed eligible to participate in the intervention chose not to in the end. Fear of reporting practices among health professionals might have played a role in this, as described by forum members that discussed the intervention and the obligatory SUD treatment, as well as in previous studies (Havnes et al., Citation2019; Havnes & Skogheim, Citation2020). These legal repercussions could include issues with child protection services or driver’s license authorities, or that having a medical file that involves AAS use may potentially influence access to future life insurance. Moreover, men who in a previous study contacted The National Steroid Project’s information service feared that the health professionals would report their AAS use to employers or to the police if they were enrolled in SUD treatment (Havnes et al., Citation2019). It is therefore likely that fear of sanctions would not only influence negatively on the engagement towards public treatment services but also towards entering a clinical study administered by a public university hospital. This is further strengthened by the fact that we continuously tested urine samples for the use of AAS or other illegal substances, that SUD treatment was made compulsory for every study participant, and that patient records were logged electronically. Thus, some may have been reluctant to enter SUD treatment, as they did not wish to have their AAS use documented in their medical file or did not necessarily identify as having a SUD use. There is reason to believe that all these factors might have dissuaded those who received information about the study from participating. However, we found support in the argument for obligatory SUD treatment among user involvements in the planning of the protocol. Yet, despite previous positive experiences with SUD treatment for AAS cessation, some individuals from our user panel initially warned that the mandatory enrollment to SUD treatment might be met with skepticism. Still, as there was a risk of prolonged symptom burden in cases of delayed or low treatment response, a joint decision was made to refer all eligible participants to SUD treatment at the time of study inclusion. Additionally, in the occasions of co-occurring mental health problems, other comorbidities or socioeconomic and interpersonal challenges, SUD treatment would be considered beneficial. Finally, it may be considered both ethical and financial feasible to include participants as patients in the public healthcare system as it not only requires less study funding due to clinical examinations being part of the treatment but also ensures documentation and follow-up of pathological findings according to the Norwegian health legislation.

Barriers to participate in the study

We directly targeted the community of people who use AAS by posting study details in an online AAS forum. Forum members were skeptical to having the study organized within the public SUD treatment system. Furthermore, they criticized and suggested modifications to the proposed intervention: the choice of study drug (clomiphene citrate); the dosage, which were perceived as too low, or the treatment period, which some thought was too short. This shows that there are diverse perspectives on PCT among those who self-medicate, as the intervention design was largely based on recommendations from men who use AAS, both from a user panel of persons with previous AAS use and from user involvement in the original protocol (Rahnema et al., Citation2014).

The criminalization of AAS use might also have worked as a barrier to study participation as some forum members advised against it due to fear of sanctions or police reporting, either by the researchers or the SUD treatment providers, as previously described (Havnes et al., Citation2019; Havnes & Skogheim, Citation2020).

Research suggests that people who use AAS seek information from peers online (Andreasson & Henning, Citation2022; Frude et al., Citation2020; Henning & Andreasson, Citation2021; Smith & Stewart, Citation2012; Tighe et al., Citation2017). This was found to be the case in this study where forum members gave advice about various PCT protocols and self-treatment regimens, as well as how to self-initiate TRT at the end of an AAS cycle instead of using PCT, to both stabilize endogenous testosterone levels and improve mental health. It seems that customized, online recommendations from peers might be more attractive to some persons who use AAS than participating in studies that investigate health risks and the effects of PCT. Forum members expressed a bigger trust in the general knowledge of people who use AAS than physicians. A netnography by Underwood et al. (Citation2021) found that some are motivated to self-initiate TRT due to low willingness to prescribe TRT among physicians, a perceived lack of AAS knowledge among healthcare professionals, and that non-prescribed testosterone is easily accessible at a low price. Moreover, self-initiated TRT was found to be used in a similar way as prescribed medical TRT, and often seen as a better alternative than cessation. The authors suggest that the ‘repair/enhancement dichotomy’ is more useful when discussing AAS use, rather than label non-prescribed testosterone use as abuse (Underwood et al., Citation2021). This thematic was also discussed among forum members in the current study where cycling as enhancement was perceived as ‘AAS use’, as opposed to ‘self-initiated TRT’ which was perceived as self-treatment and a way of discontinuing ‘AAS use’. Although non-prescribed products used for TRT and PCT are easily available (Cox et al., Citation2023; McBride et al., Citation2018), these products may be counterfeit (i.e. they are over- or under dosed, do not contain active substances or are made up of other substance(s) than the ones labeled) (Magnolini et al., Citation2022) and may together with contaminated AAS lead to health problems (Frude et al., Citation2020). Hence, some choose to manufacture AAS at home for personal use instead, as this is perceived to lower the risk for counterfeit and contaminated substances (Brennan et al., Citation2018). Although various self-treatment regimens could lead to bodily harms, it may still be seen as a form of harm reduction strategy. Forum users desired access to legal and prescribed TRT for men with low endogenous testosterone levels, instead of using illicit substances or quitting use. Thus, previous experiences with unsuccessful AAS cessation may therefore have worked as a barrier to participation in the study.

Strengths and limitations

It may be considered a strength that AAS user involvement played a role in the planning and recruitment phase of this pilot study. However, the user panel consisted of people with previous AAS use and positive SUD or other treatment experiences, with a desire to obtain more knowledge about their health status following cessation of AAS. By conducting a short survey among men with current use or by including them earlier in the planning phase, we could have potentially garnered insights into factors that would make participation more appealing. It may be seen as a strength that we included a thematic analysis of the discussion among members of an online AAS forum in response to the study advertisement, as this gave us valuable information about possible barriers to participation. However, it should be considered a limitation that this analysis was not planned beforehand and that the data was solely collected from a single thread with 20 active forum members.

Lessons learned and recommendations for future studies

Individuals with current or previous AAS use should be involved in an early planning phase, which could include both online surveys and meetings with researchers

Future studies exploring off-label use of anti-estrogens on people who withdraw from AAS should consider safety assessments prior to starting off-label interventions with PCT

Similar future studies that use social media for recruitment, should be cautious of using sensitive titles (e.g. ‘anabolic steroids’) or graphics showing bare skin, as these advertisements risk being banned on various social media platforms.

Enrollment of participants into a parallel, public SUD treatment program, ensures a safer, more ethical and more cost-effective study execution, but may contribute to challenges in recruitment.

Future studies should consider free SUD (or other) treatment, cover travel expenses or compensate participants with economic incentives for time spent on health examinations.

In cases of study postponements due to unforeseen circumstances, which in our case was the COVID-19 pandemic, further funding is needed to be able to prolong the recruitment period.

The inclusion examinations turned out to be demanding for some participants, as the examinations were performed at different clinics and by multiple examiners, and thus could rarely be conducted on the same day. For future studies, this could be solved by reducing the location sites with single-center trials, and thus minimize the number of examinations and forgo assessments of AAS-related health risks. This could be particularly relevant for smaller studies or pilot studies.

The expressed interest for the study across the country suggests that a multicenter trial may lead to higher inclusion rates.

The contribution of the National Steroid Project and its direct helpline proved to be an important recruitment strategy and seemed to be the most effective way of recruiting participants with an intention to cease AAS use. Having access to an initial noncommittal and anonymous information session with a healthcare professional seem to be a motivating factor to enter a research project with a parallel SUD treatment program. Similar services should therefore be considered utilized for future treatment studies in this particular patient population.

While hormone therapy following AAS cessation aims to treat the endocrine part of the AAS dependence, SUD-treatment focuses more on other central parts of dependence such as body image disorder and reward effects. For future similar studies, SUD treatment could be considered an option, rather than a requirement, limited only to participants who experience suicidal ideation during AAS withdrawal, body image disorder, lack of reward effects or comorbid mental health problems in need of treatment. This could be based on an initial evaluation prior to inclusion, as well as close monitoring by study researchers with clinical expertise throughout the intervention period.

Some men have no desire to cease AAS use despite access to legal PCT, mainly due to previous experience with burdensome withdrawal symptoms after cessation. Instead they choose to self-initiate TRT at the end of an AAS cycle or after cessation of continuous AAS use.

For some, customized, online recommendations from peers is more appealing than participation in studies that investigate the effects of PCT, especially if participation involves SUD patient status with records of AAS use in the medical file.

Naturalistic observational studies may be considered an option to intervention studies, either to explore the effect of non-prescribed PCT or to compare the effects of non-prescribed PCT with self-initiated TRT. However, this approach might be subject by various sources of error.

Conclusion

Challenges in recruitment included difficulty reaching the target group with information about the study, as well as other barriers, such as financial limitations, obligatory enrollment to SUD treatment, self-initiated TRT as an option to cease use, criticism from potential participants of the medical protocol used for the intervention and fear of being prosecuted as AAS use is criminalized in Norway. Our experienced challenges and lessons learned may be considered a valuable contribution to research on its potential guidance of future clinical trials on treatment for people who use AAS.

Author’s contributions

IAH is Principal Investigator and was responsible for the study design together with APJ. CW and HCBH were the main contributors to active participant recruitment. HCBH, IAH and APJ were responsible for eligibility screening, inclusion examinations and data collection. HCBH and IAH planned the analyses for this paper and jointly conducted the thematic analysis. HCBH wrote the first draft of the manuscript and IAH drafted the qualitative part. APJ and CW provided critical feedback on the manuscript. All authors contributed substantially to the manuscript, and have approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

This study has benefited from the contributions of a user panel, who provided helpful feedback in the recruitment process. Special thanks go to Christina Brux for useful comments and for language editing on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term “use” among forum members mainly referred to the use of AAS in supra-physiologic doses and cycles, and not necessarily to the use of self-initiated TRT.

References

- Amaral, J. M. X., Kimergard, A., & Deluca, P. (2022). Prevalence of anabolic steroid users seeking support from physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 12(7), e056445. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056445

- Andreasson, J., & Henning, A. (2022). “Falling down the Rabbit Fuck Hole”: Spectacular masculinities, hypersexuality, and the real in an online doping community. Journal of Bodies, Sexualities, and Masculinities, 3(2), 76–97. https://doi.org/10.3167/jbsm.2022.030205

- Bates, G., Van Hout, M. C., Teck, J. T. W., & McVeigh, J. (2019). Treatments for people who use anabolic androgenic steroids: A scoping review. Harm Reduction Journal, 16(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-019-0343-1

- Bjornebekk, A., Westlye, L. T., Walhovd, K. B., Jorstad, M. L., Sundseth, O. O., & Fjell, A. M. (2019). Cognitive performance and structural brain correlates in long-term anabolic-androgenic steroid exposed and nonexposed weightlifters. Neuropsychology, 33(4), 547–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000537

- Bojsen-Moller, J., & Christiansen, A. V. (2010). Use of performance and image-enhancing substances among recreational athletes: A quantitative analysis of inquiries submitted to the Danish anti-doping authorities. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 20(6), 861–867. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01023.x

- Bonevski, B., Randell, M., Paul, C., Chapman, K., Twyman, L., Bryant, J., Brozek, I., & Hughes, C. (2014). Reaching the hard-to-reach: A systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-42

- Bonnecaze, A. K., O’Connor, T., & Aloi, J. A. (2020). Characteristics and attitudes of men using Anabolic Androgenic Steroids (AAS): A survey of 2385 men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 14(6), 1557988320966536. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988320966536

- Bonnecaze, A. K., O’Connor, T., & Burns, C. A. (2021). Harm reduction in male patients actively using Anabolic Androgenic Steroids (AAS) and Performance-Enhancing Drugs (PEDs): A review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(7), 2055–2064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06751-3

- Botman, E., Smit, D. L., & de Ronde, W. (2023). Clinical question: How to manage symptoms of hypogonadism in patients after androgen abuse? Clinical Endocrinology, 98(4), 469–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.14686

- Brennan, R., Wells, J. S. G., & Van Hout, M. C. (2017). The injecting use of image and performance-enhancing drugs (IPED) in the general population: A systematic review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(5), 1459–1531. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12326

- Brennan, R., Wells, J. S. G., & Van Hout, M. C. (2018). “Raw juicing” – An online study of the home manufacture of anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS) for injection in contemporary performance and image enhancement (PIED) culture. Performance Enhancement & Health, 6(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peh.2017.11.001

- Choi, J., Lee, S., & Lee, C.-N. (2021). Isolated cortical vein thrombosis in an infertile male taking clomiphene citrate. Neurological Sciences, 42(4), 1615–1616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04862-z

- Choi, S.-H., Shapiro, H., Robinson, G. E., Irvine, J., Neuman, J., Rosen, B., Murphy, J., & Stewart, D. (2005). Psychological side-effects of clomiphene citrate and human menopausal gonadotrophin. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 26(2), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443610400022983

- Coward, R. M., Rajanahally, S., Kovac, J. R., Smith, R. P., Pastuszak, A. W., & Lipshultz, L. I. (2013). Anabolic steroid induced hypogonadism in young men. The Journal of Urology, 190(6), 2200–2205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.010

- Cox, L., Gibbs, N., & Turnock, L. A. (2023). Emerging anabolic androgenic steroid markets; the prominence of social media. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 2023, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2023.2176286

- de Ronde, W., & Smit, D. L. (2020). Anabolic androgenic steroid abuse in young males. Endocrine Connections, 9(4), R102–R111. https://doi.org/10.1530/EC-19-0557

- Festinger, D. S., Marlowe, D. B., Croft, J. R., Dugosh, K. L., Mastro, N. K., Lee, P. A., DeMatteo, D. S., & Patapis, N. S. (2005). Do research payments precipitate drug use or coerce participation? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 78(3), 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.011

- Festinger, D. S., Marlowe, D. B., Dugosh, K. L., Croft, J. R., & Arabia, P. L. (2008). Higher magnitude cash payments improve research follow-up rates without increasing drug use or perceived coercion. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 96(1–2), 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.007

- Frude, E., McKay, F. H., & Dunn, M. (2020). A focused netnographic study exploring experiences associated with counterfeit and contaminated anabolic-androgenic steroids. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00387-y

- Ganson, K. T., Murray, S. B., Mitchison, D., Hawkins, M. A. W., Layman, H., Tabler, J., & Nagata, J. M. (2021). Associations between adverse childhood experiences and performance-enhancing substance use among young adults. Substance Use & Misuse, 56(6), 854–860. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2021.1899230

- Griffiths, S., Henshaw, R., McKay, F. H., & Dunn, M. (2017). Post-cycle therapy for performance and image enhancing drug users: A qualitative investigation. Performance Enhancement & Health, 5(3), 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peh.2016.11.002

- Harvey, O., Keen, S., Parrish, M., & van Teijlingen, E. (2019). Support for people who use Anabolic Androgenic Steroids: A Systematic Scoping Review into what they want and what they access. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1024. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7288-x

- Havnes, I., & Skogheim, T. (2020). Alienation and lack of trust barriers to seeking substance use disorder treatment among men who struggle to cease anabolic-androgenic steroid use. Journal of Extreme Anthropology, 3, 7046. https://doi.org/10.5617/jea.7046

- Havnes, I. A., Jorstad, M. L., & Wisloff, C. (2019). Anabolic-androgenic steroid users receiving health-related information; health problems, motivations to quit and treatment desires. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 14(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-019-0206-5

- Havnes, I. A., Jørstad, M. L., McVeigh, J., Van Hout, M. C., & Bjørnebekk, A. (2020). The anabolic androgenic steroid treatment gap: A national study of substance use disorder treatment. Substance Abuse, 14, 1178221820904150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178221820904150

- Henning, A., & Andreasson, J. (2021). “Yay, another lady starting a log!”: Women’s fitness doping and the gendered space of an online doping forum. Communication & Sport, 9(6), 988–1007. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479519896326

- Henriksen, H. C. B., Havnes, I. A., Jørstad, M. L., & Bjørnebekk, A. (2023). Health service engagement, side effects and concerns among men with anabolic-androgenic steroid use: A cross-sectional Norwegian study. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 18(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-023-00528-z

- Horwitz, H., Andersen, J. T., & Dalhoff, K. P. (2019). Health consequences of androgenic anabolic steroid use. Journal of Internal Medicine, 285(3), 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12850

- Kanayama, G., Brower, K. J., Wood, R. I., Hudson, J. I., & Pope, H. G.Jr (2010). Treatment of anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence: Emerging evidence and its implications. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 109(1–3), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.011

- Kanayama, G., Hudson, J. I., DeLuca, J., Isaacs, S., Baggish, A., Weiner, R., Bhasin, S., & Pope, H. G.Jr (2015). Prolonged hypogonadism in males following withdrawal from anabolic-androgenic steroids: An under-recognized problem. Addiction, 110(5), 823–831. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12850

- Kicman, A. T. (2008). Pharmacology of anabolic steroids. British Journal of Pharmacology, 154(3), 502–521. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjp.2008.165

- Kozinets, R. V. (2020). E-Tourism research, cultural understanding, and netnography. Springer.

- Krzastek, S. C., Sharma, D., Abdullah, N., Sultan, M., Machen, G. L., Wenzel, J. L., Ells, A., Chen, X., Kavoussi, M., Costabile, R. A., Smith, R. P., & Kavoussi, P. K. (2019). Long-term safety and efficacy of clomiphene citrate for the treatment of hypogonadism. The Journal of Urology, 202(5), 1029–1035. https://doi.org/10.1097/ju.0000000000000396

- Lindqvist, A. S., Moberg, T., Ehrnborg, C., Eriksson, B. O., Fahlke, C., & Rosen, T. (2014). Increased mortality rate and suicide in Swedish former elite male athletes in power sports. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 24(6), 1000–1005. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12122

- Ljungdahl, S., Ehrnborg, C., Eriksson, B. O., Bagge, A.-S L., Tommy, M., Fahlke, C., & Rosén, T. (2019). Patients who seek treatment for AAS abuse in Sweden: Description of characteristics. J Addict Med Ther, 3, 11.

- Lundholm, L., Frisell, T., Lichtenstein, P., & Långström, N. (2015). Anabolic androgenic steroids and violent offending: Confounding by polysubstance abuse among 10,365 general population men. Addiction, 110(1), 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12715

- Magnolini, R., Falcato, L., Cremonesi, A., Schori, D., & Bruggmann, P. (2022). Fake anabolic androgenic steroids on the black market – A systematic review and meta-analysis on qualitative and quantitative analytical results found within the literature. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1371. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13734-4

- McBride, J. A., Carson, C. C., 3rd., & Coward, R. M. (2018). The availability and acquisition of illicit anabolic androgenic steroids and testosterone preparations on the internet. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(5), 1352–1357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988316648704

- Melsom, H. S., Heiestad, C. M., Eftestol, E., Torp, M. K., Gundersen, K., Bjornebekk, A. K., Thorsby, P. M., Stenslokken, K. O., & Hisdal, J. (2022). Reduced arterial elasticity after anabolic-androgenic steroid use in young adult males and mice. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 9707. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14065-5

- Moskovic, D. J., Katz, D. J., Akhavan, A., Park, K., & Mulhall, J. P. (2012). Clomiphene citrate is safe and effective for long‐term management of hypogonadism. BJU International, 110(10), 1524–1528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.10968.x

- National Advisory Unit on Substance Use Treatment, O. U. H. (2015). Kunnskap og behandling i diagnostikk og behandling av AAS-brukere. https://oslo-universitetssykehus.no/fag-og-forskning/nasjonale-og-regionale-tjenester/tsb/-behandling-av-steroidebrukere

- Piacentino, D., Kotzalidis, G. D., Del Casale, A., Aromatario, M. R., Pomara, C., Girardi, P., & Sani, G. (2015). Anabolic-androgenic steroid use and psychopathology in athletes. A systematic review. Current Neuropharmacology, 13(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159x13666141210222725

- Pope, H. G., Jr., Wood, R. I., Rogol, A., Nyberg, F., Bowers, L., & Bhasin, S. (2014). Adverse health consequences of performance-enhancing drugs: An Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocrine Reviews, 35(3), 341–375. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2013-1058

- Pope, H. G., Kanayama, G., Ionescu-Pioggia, M., & Hudson, J. I. (2004). Anabolic steroid users’ attitudes towards physicians. Addiction, 99(9), 1189–1194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00781.x

- Pope, H. G., Kean, J., Nash, A., Kanayama, G., Samuel, D. B., Bickel, W. K., & Hudson, J. I. (2010). A diagnostic interview module for anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence: Preliminary evidence of reliability and validity. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18(3), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019370

- Purvin, V. A. (1995). Visual disturbance secondary to clomiphene citrate. Archives of Ophthalmology, 113(4), 482–484. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1995.01100040102034

- Rahnema, C. D., Lipshultz, L. I., Crosnoe, L. E., Kovac, J. R., & Kim, E. D. (2014). Anabolic steroid-induced hypogonadism: Diagnosis and treatment. Fertility and Sterility, 101(5), 1271–1279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.002

- Rasmussen, J. J., Schou, M., Madsen, P. L., Selmer, C., Johansen, M. L., Hovind, P., Ulriksen, P. S., Faber, J., Gustafsson, F., & Kistorp, C. (2018). Increased blood pressure and aortic stiffness among abusers of anabolic androgenic steroids: Potential effect of suppressed natriuretic peptides in plasma? Journal of Hypertension, 36(2), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000001546

- Rasmussen, J. J., Schou, M., Madsen, P. L., Selmer, C., Johansen, M. L., Ulriksen, P. S., Dreyer, T., Kumler, T., Plesner, L. L., Faber, J., Gustafsson, F., & Kistorp, C. (2018). Cardiac systolic dysfunction in past illicit users of anabolic androgenic steroids. American Heart Journal, 203, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2018.06.010

- Rasmussen, J. J., Schou, M., Selmer, C., Johansen, M. L., Gustafsson, F., Frystyk, J., Dela, F., Faber, J., & Kistorp, C. (2017). Insulin sensitivity in relation to fat distribution and plasma adipocytokines among abusers of anabolic androgenic steroids. Clinical Endocrinology, 87(3), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.13372

- Rasmussen, J. J., Selmer, C., Ostergren, P. B., Pedersen, K. B., Schou, M., Gustafsson, F., Faber, J., Juul, A., & Kistorp, C. (2016). Former abusers of anabolic androgenic steroids exhibit decreased testosterone levels and Hypogonadal symptoms years after cessation: A case-control study. PLoS One, 11(8), e0161208. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161208

- Richardson, A., & Antonopoulos, G. A. (2019). Anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) users on AAS use: Negative effects, ‘code of silence’, and implications for forensic and medical professionals. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 68, 101871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2019.101871

- Skauen, J. E., Pallesen, S., Bjørnebekk, A., Chegeni, R., Syvertsen, A., Petróczi, A., & Sagoe, D. (2023). Prevalence and correlates of androgen dependence: A meta-analysis, meta-regression analysis and qualitative synthesis. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity, 2023, 22. https://doi.org/10.1097/med.0000000000000822

- Smit, D. L., & de Ronde, W. (2018). Outpatient clinic for users of anabolic androgenic steroids: An overview. Netherlands Journal of Medicine, 76(4), 167.

- Smith, A. C., & Stewart, B. (2012). Body perceptions and health behaviors in an online bodybuilding community. Qualitative Health Research, 22(7), 971–985. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312443425

- Solipuram, V., Pokharel, K., & Ihedinmah, T. (2021). Pulmonary embolism as a rare complication of clomiphene therapy: A case report and literature review. Case Reports in Endocrinology, 2021, 9987830. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9987830

- Taylor, F., & Levine, L. (2010). Clomiphene citrate and testosterone gel replacement therapy for male hypogonadism: Efficacy and treatment cost. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(1 Pt 1), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01454.x

- The National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities, N. E. S. H. (2019). A Guide to Internet Research Ethics. https://www.forskningsetikk.no/en/guidelines/social-sciences-humanities-law-and-theology/a-guide-to-internet-research-ethics

- The Norwegian Health Economics Administration. (2023). Exemption card for public health services in Norway. https://www.helsenorge.no/en/payment-for-health-services/exemption-card-for-public-health-services/

- Thiblin, I., Runeson, B., & Rajs, J. (1999). Anabolic androgenic steroids and suicide. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 11(4), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022313529794

- Tighe, B., Dunn, M., McKay, F. H., & Piatkowski, T. (2017). Information sought, information shared: Exploring performance and image enhancing drug user-facilitated harm reduction information in online forums. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0176-8

- Underwood, M., van de Ven, K., & Dunn, M. (2021). Testing the boundaries: Self-medicated testosterone replacement and why it is practised. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 95, 103087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.103087

- Westerman, M. E., Charchenko, C. M., Ziegelmann, M. J., Bailey, G. C., Nippoldt, T. B., & Trost, L. (2016). Heavy testosterone use among bodybuilders: An uncommon cohort of illicit substance users. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 91(2), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.10.027

- Wheeler, K. M., Sharma, D., Kavoussi, P. K., Smith, R. P., & Costabile, R. (2019). Clomiphene citrate for the treatment of hypogonadism. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 7(2), 272–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.10.001

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for, E., European Observatory on Health, S., Policies, Ringard, Å., Sagan, A., Sperre Saunes, I., & Lindahl, A. K. (2013). Norway: Health system review. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330299

- Yu, J., Hildebrandt, T., & Lanzieri, N. (2015). Healthcare professionals’ stigmatization of men with anabolic androgenic steroid use and eating disorders. Body Image, 15, 49–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.06.001

- Zahid, M., Arshad, A., Zafar, A., & Al-Mohannadi, D. (2016). Intracranial venous thrombosis in a man taking clomiphene citrate. BMJ Case Reports, 2016, bcr2016217403. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-217403

- Zahnow, R., McVeigh, J., Bates, G., Hope, V., Kean, J., Campbell, J., & Smith, J. (2018). Identifying a typology of men who use anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS). The International Journal on Drug Policy, 55, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.02.022

- Zahnow, R., McVeigh, J., Ferris, J., & Winstock, A. (2017). Adverse effects, health service engagement, and service satisfaction among anabolic androgenic steroid users. Contemporary Drug Problems, 44(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450917694268

- Zhang, H.-M., Zhao, X.-H., He, Y.-F., & Sun, L.-R. (2018). Liver injury induced by clomiphene citrate: A case report and literature reviews. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 43(2), 299–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12654