Abstract

Background

Low-THC cannabis products have become popular worldwide and are used as self-treatment for a variety of medical conditions despite limited high-quality evidence on efficacy or long-term side-effects.

Method: We compare the experiences of CBD-oil-only users to that of users, who indicated use of cannabis products conventionally higher in THC (high-THC cannabis) with respect to number of symptoms relieved, overall perceived effect on symptoms, effect on pain level and sleep duration, and perceived side-effects. A self-selected convenience sample of Danish cannabis users were recruited to an anonymous online survey. Inclusion criteria were 18 years or older and use of cannabis as medicine (CaM) (prescribed or non-prescribed).

Results

The final sample included 2.642 users of CaM, of which 992 were CBD-oil-only users and 1650 used high-THC products. Compared to respondents who used high-THC cannabis, CBD-oil-only users reported fewer symptoms relieved by cannabis, a slightly lower overall symptom reduction, as well as comparable pain reduction and sleep improvement. CBD-oil-only users reported fewer side-effects and were more likely to report no side-effects of cannabis.

Conclusion: CBD-oils may produce less intense effects compared to high-THC cannabis products, while also producing fewer side-effects. Regulation of the legal low-THC cannabis market is needed.

Background

In the last decades, there has been an increased interest in cannabidiol (CBD: main non-psychotropic component of cannabis), as CBD-dominant cannabis products have become popular worldwide (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Citation2020; Hazekamp, Citation2018; Manthey, Citation2019), both as self-medication for a myriad of conditions (e.g., pain, sleep problems) and for general health and well-being (Corroon & Phillips, Citation2018; Fortin et al., Citation2021; Goodman et al., Citation2020; Moltke & Hindocha, Citation2021). In most European countries, multiple country-level changes in the regulation of hemp products has resulted in open sale of so called ‘low-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (low-THC) cannabis products’ (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Citation2020). Low-THC cannabis products are defined as cannabis products that claim or appear to have a very low percentage of THC and which would be unlikely to cause intoxication (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Citation2020, p. 4). These products are typically marketed for their low concentration of THC (main psychoactive component of cannabis) or their high concentration of CBD (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Citation2020). While high concentrations of THC have been shown to increase risk of psychosis and cannabis addiction (Colizzi & Bhattacharyya, Citation2017; Curran et al., Citation2019; Di Forti et al., Citation2019; Freeman et al., Citation2018; Quattrone et al., Citation2021), low-THC cannabis products may be attractive to users who wish to experiment with medicinal cannabis use, while avoiding some of the risks conventionally associated with cannabis use. Also, low-THC cannabis products with high concentration of CBD are likely to have increased in popularity, because these products are often advertised with health claims that drastically exceeds the current body of knowledge (Evans, Citation2020; Lachenmeier & Walch, Citation2020; Wagoner et al., Citation2021; Zenone et al., Citation2021).

Public health concerns related to low-THC cannabis products

The emerging use of low-THC cannabis products has raised public health concerns with respect to long-term safety, efficacy, and quality of the products. Emerging research shows therapeutic effects of CBD for epilepsy and Parkinsonism (Bilbao & Spanagel, Citation2022), and indicates a therapeutic potential of CBD for various conditions, such as rheumatic disease (Boehnke et al., Citation2022), bacterial infections (Blaskovich et al., Citation2021), gastrointestinal disorders (Martínez et al., Citation2020), psychosis (Chesney et al., Citation2021) and substance use disorder (Navarrete et al., Citation2021). Parallel to this, there is a growing consensus of CBD having a favourable safety profile with limited side-effects and no abuse potential (Arnold et al., Citation2022; Chesney et al., Citation2020; Fasinu et al., Citation2016; Iffland & Grotenhermen, Citation2017), and according to the World Health Organization, no public health problems have been associated with CBD use (World Health Organization: Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, Citation2018). Still, large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with long-term follow-up are lacking (Arnold et al., Citation2022; Bilbao & Spanagel, Citation2022; Black et al., Citation2019), and clinical data supporting the use of CBD as a pharmacotherapy is currently limited to the treatment of seizures with the drug Epidiolex (Britch et al., Citation2021; Wise, Citation2019). Public health concerns also involve the lack of quality control with low-THC cannabis products currently used without prescription for self-medication purposes, as several studies have found labelling inaccuracies of available CBD products, both in the US (Bonn-Miller et al., Citation2017; Johnson et al., Citation2022; Vandrey et al., Citation2015) and Europe (Hazekamp, Citation2018; International Medical Cannabis Patient Coalition, Citation2017; Lachenmeier et al., Citation2019; Pavlovic et al., Citation2018), including Denmark (Eriksen & Christoffersen, Citation2020).

Medical cannabis in Denmark

From 2013 and onward, the topic of medical cannabis has become increasingly salient in the Danish media (Houborg & Enghoff, Citation2018), with multiple reports of people with severe conditions self-medicating with illegal cannabis products (Avisen, Citation2017; Bechgaard, Citation2014; Dr1, Citation2017; Dr2, Citation2014), and a 2016 poll suggesting that at least 50.000 (app. 1%) Danes used cannabis as medicine (CaM) (Damløv, Citation2016). In 2018, a Medical Cannabis Pilot Program (MCPP) was initiated in Denmark, providing prescribed whole plant cannabis to patients with multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, as well as patients with treatment resistant chronic pain or chemotherapy-related nausea, and vomiting (Ministry of Health, Citation2016). However, despite this change in Danish policy, there are still indications of a vast use of cannabis for self-medication purposes outside the legal framework, reported by various patient groups in Denmark (Danske Patienter, Citation2020; Gustavsen et al., Citation2019; Kvamme et al., Citation2021a; Nielsen et al., Citation2021). Further, there are indications that low-THC products have become popular, with growth in web shops selling CBD-oils with less than 0.2% THC (Brix, Citation2020; Cuculiza, Citation2019; Damløv, Citation2016), and with physical stores in major cities (Andersen, Citation2022; CBD-Helten, Citation2022; Undonno Store, Citation2022), and day-to-day home delivery services (Weedshop, Citation2022) openly selling low-THC cannabis products. Yet another indication of the growing market for CBD products in Denmark is the illegal medicines confiscated by the Danish Medicines Agency, where 39% of all illegal medicines was found to contain the letters CBD in 2021 (Danish Medicines Agency, Citation2021). Outside the MCPP, all cannabis use is illegal in Denmark, both sale and possession, except for a legal limit of 0.2% THC in commercial hemp products, such as cosmetics and food, that was established in 2018 (Danish Medicines Agency, Citation2018). This limit has placed cannabis products with less than 0.2% THC in a legal grey area, as these products are legal to buy and possess, but illegal to sell if they are considered to be medicine by the Danish Medicines Agency, which most of them are (Danish Medicines Agency, Citation2018). Uncertainties in the legislative framework for CBD-products, is far from unique to Denmark, as the legalization of hemp products with low-THC, has enabled over the counter and online sale of CBD products in several jurisdictions, with marketed products sometimes failing to meet the legal requirements for sale (McGregor et al., Citation2020), This is also the case in Denmark, where an analysis from 2020 by Department of Forensic Medicine at the University of Southern Denmark showed that out of 58 CBD-oils, 38% contained illegal amounts of THC (ranging from 0.2% to 1%) (Eriksen & Christoffersen, Citation2020), making these products illegal, both to sell and possess, according to the Danish Act on Euphoriant Substances. Of note, other European countries (Switzerland and the Czech Republic) have a 1% THC limit and consequently these products are easily available to Danes through web shops.

The relevance of cannabinoid composition

Still, the THC concentration in CBD-oils found in Denmark is considered very low compared to cannabis products on the illegal drug market in Denmark such as skunk (Sinsemilla) or hash (cannabis resin) that are typically used for recreational purposes. Skunk has been found to contain high concentrations of THC (≈14%) and minimal concentration of CBD (Potter et al., Citation2008, Citation2018), and the THC content in hash has increased markedly in the last decades across European countries (Freeman, Craft, et al., Citation2020); in Denmark, the THC concentration in seized hash increased threefold from 2000 (mean: 8.3%) to 2017 (mean: 25.3%), while CBD concentrations remained stable (mean around 6%) (Rømer Thomsen et al., Citation2019). These changes in the cannabinoid composition are highly relevant to public health; while THC may have therapeutic utility and potential (Bilbao & Spanagel, Citation2022; Legare et al., Citation2022), frequent use of cannabis with high concentration of THC has been associated with increased risk of cannabis-related harms such as cognitive impairment (Colizzi & Bhattacharyya, Citation2017; Englund et al., Citation2017; Morgan et al., Citation2018; Rømer Thomsen et al., Citation2017), cannabis use disorder (Curran et al., Citation2016, Citation2019; Freeman et al., Citation2018; Freeman & Winstock, Citation2015; Meier, Citation2017), and psychosis (Di Forti et al., Citation2015, Citation2019; Quattrone et al., Citation2021). Conversely, some studies suggest that CBD has anxiolytic and antipsychotic effects (Blessing et al., Citation2015; Bonaccorso et al., Citation2019; Freeman et al., Citation2019; Iseger & Bossong, Citation2015), and may – in high doses—provide a potential for treatment of cannabis use disorders (Freeman, Hindocha, et al., Citation2020; Navarrete et al., Citation2021; Thomsen et al., Citation2021). There is also some indications that high doses of CBD protects against some of the harmful effects of THC (Bonaccorso et al., Citation2019; Freeman et al., Citation2019), although a recent RCT examining THC:CBD ratios corresponding to cannabis products available on the UK market (i.e., much lower CBD concentration) failed to find protective effects of CBD (Englund et al., Citation2022). The emerging research on the effects of THC, CBD, and specific THC:CBD ratios, has contributed with valuable findings, but barriers to conducting whole plant cannabis research (National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, Citation2017; Piomelli et al., Citation2019) has made it difficult to compare available high quality evidence to observed outcomes from whole plant cannabis used in medicinal or recreational settings. These barriers are both technical and economic (Fortin & Massin, Citation2020) and occur even in countries that have fully legalize the adult use of cannabis (Rueda et al., Citation2022).

The relevance of ‘real world evidence’

With the emerging popular use of CBD products outpacing both the current scientific knowledge as well as regulatory practices, the relevance of ‘real world evidence’ on user experiences with medicinal use related to various cannabis products have been emphasized (Banerjee et al., Citation2022; Graham et al., Citation2020; Schlag et al., Citation2022). While RCTs are necessary in order to potentially establish a causal relationship between medical cannabis use and positive health outcomes, studies exploring ‘real world’ user experiences can inform public health policy, complement RCTs, and improve guidance on safety and adverse events. Further, ‘real world evidence’ can offer insight into the experiences of users with co-morbidities, who are conventionally excluded from RCT’s (Fortin, Marcellin, et al., Citation2022; Rothwell, Citation2005; Veziari et al., Citation2017), despite potentially being overrepresented among medicinal cannabis users (Gardiner et al., Citation2019). In this context, the emerging use of ‘Do-It-Yourself’-medicine in Denmark that involves the grey and illegal cannabis markets, presents a unique opportunity to explore perceived effects and side-effects of whole plant cannabis products with variations in CBD and THC content.

In this study, we utilized a large, self-selected sample of Danish users of CaM to explore potential differences in perceived effects and side-effects depending on subtypes of cannabis used. Specifically, we compare CBD-oil-only users’ experiences with users who use cannabis products conventionally higher in THC content (‘high-THC cannabis’) in terms of number of symptoms relived, overall effect, effects on pain and sleep, and side-effects.

Methods

Study design

The study was a part of a larger survey-based study on the use of CaM in Denmark, which is the first survey on CaM in Denmark. The survey was made available online from July 14th to November 1st 2018 to a self-selected convenience sample of users of CaM with a self-perceived medical motive for use, either prescribed by a doctor or non-prescribed. Participants were recruited via the national media, patient organisations, in selected doctors’ offices and hospitals, at the illegal open drug market, Christiania, and through various cannabis related sites on social media. The survey was inspired by previous surveys on use of CaM in other countries (Grotenhermen & Schnelle, Citation2003; Hazekamp et al., Citation2013; Reiman et al., Citation2017; Reinarman et al., Citation2011; Sexton et al., Citation2016; Ware et al., Citation2005; Webb & Webb, Citation2014). The survey consisted of 42 structured questions and 21 possible follow-up questions, answered in a yes/no format, multiple-choice response, and rating scales. The questions were divided in six thematic sections; (1) Motives for use, (2) Substitution of a prescription drug, (3) Patterns of use, (4) Becoming a medicinal cannabis user, (5) Access and stigma, (6) Attitudes and demography. Survey duration was approximately 15 minutes. The survey was in Danish only, however subsequently we have made an English version of the survey available here (Kvamme, Citation2022a). IP addresses of the respondents were not saved or made available to the researchers, prioritizing respondent anonymity over the possibility of repeated participation (Barratt et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). For a detailed description of the large survey and recruitment procedures, see (Kvamme, Citation2022a; Kvamme et al., Citation2021a).

Data from the survey have previously been used to examine motives and patterns of use of CaM (Kvamme et al., Citation2021a), use of cannabis as a substitute for prescription drugs (Kvamme et al., Citation2021b), and previous recreational experience when initiating use of CaM (Kvamme, Citation2022b). The current study explores perceived effects and side-effects related to use of subtypes of cannabis products. We have chosen to give particular attention to the experiences of CBD-oil-only users, as there has been a rapid emergence of this type of cannabis product in the cannabis market in Denmark and there is a dearth of research exploring this type of use (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Citation2020).

Measures

Conditions treated with CaM

Respondent were presented with a list of 52 conditions when reporting conditions treated with CaM. The conditions were categorized as either somatic conditions (n = 36) or psychiatric conditions (n = 13), based on ICD-10 classifications, except for ‘chronic pain,’ ‘sleep disturbances,’ and ‘stress,’ which were listed as independent categories (See Appendix A).

Experienced symptom relief by CaM

Respondents were presented with a list of 17 potential symptoms, and were asked to indicate on which symptoms they had experienced an effect of CaM.

Experienced side-effects from CaM

Respondents were presented with a list of 18 potential side-effects, and were asked to indicate side-effects that they had experienced from use of CaM.

Experienced effect of CaM on symptoms

Respondents were asked to evaluate the effect of CaM for each of the conditions that they indicated use of CaM for on a nine-point Likert scale (from − 4 = very large aggravation, to + 4 = very large improvement).

Experienced effect of CaM on pain level

Respondents who indicated that CaM had an effect on pain were asked to rate their experienced pain level without and with the use of CaM on a pain visual analogue scale (from 0 = no pain, to 10 = worst pain imaginable) (VAS: Jensen et al., Citation2003).

Experienced effect of CaM on sleep duration

Respondents who indicated that CaM had an effect on sleep disturbances were asked to report the number of hours of sleep they experience without and with the use of CaM. It was possible for respondents to indicate that their sleep improvement was not quantitative (hours), but qualitative (quality of sleep). This question was binary, and the degree of qualitative improvement was not assessed.

Patterns of use

Respondents were asked which type of cannabis product/s they used, and were presented with a list of cannabis products from which they could choose more than one product. Non-prescription products were categorized as ‘THC-oil,’ ‘CBD-oil,’ ‘Hash, pot or skunk,’ and prescription products were categorized as ‘cannabinoid-based medicine’ or ‘whole plant cannabis.’

Data management and analysis

Of the 4.570 respondents who opened the survey, 3.140 answered all questions. For the present study, we included respondents who were current users of CaM. In total, 498 were excluded: 59 were under the age of 18, 115 answered on behalf of someone next of kin, seven had inconsistencies in answers, 264 were previous users of CaM, and 53 were identified as duplicates either through an overlap in the contact information given (n = 44) or through analysis in Stata (Hamilton, Citation2012) (n = 9). Hence, 2.642 were included in the final sample.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe sample characteristics. A dummy variable was used to discriminate between users who only indicated using CBD-oil (CBD-oil-only) (1) and users who indicated using at least one cannabis product conventionally higher in THC (0), i.e., THC-oil, hash, pot or skunk, or prescribed cannabis products (Marinol, Sativex, Nabilone, Bedrocan, Bediol). Of note, the ‘CBD-oil-only’ category consists of users who only indicated use of CBD-oil, thus excluding use of high THC products. Conversely, the category of users of cannabis products higher THC, does not exclude co-use of CBD-oil. This dummy variable was used in two ways in the analyses. Firstly, as a dependent variable analysing, which user characteristics predicted exclusive use of CBD-oil, secondly, as a predictor of side-effects and experienced effect on symptoms. All analyses of user characteristics, side effect, and symptom relief were controlled for age and gender. Analyses of symptom relief and side-effects were also controlled for types of condition treated with cannabis. Differences with respect to number of symptoms and number of side-effects between CBD-oil-only users and users of cannabis products conventionally higher in THC were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Differences with respect to pain reduction and quantitative sleep improvement over time were assessed with a t-test and through a linear mixed effects model controlled for age and gender and with random intercept for each respondent. Age was centred around the grand mean.

The time points were pseudo longitudinal in that respondents were asked to evaluate pain and sleep quality before and after using CAM in this questionnaire. Differences with respect to overall effect on symptoms were assessed using a linear multiple regression controlling for age and gender.

Ethics

Respondents were informed about the study, anonymity, data storage, that their participation was voluntary, and they could drop out at any time before completion of the survey. No compensation was given for study participation. Under Danish law, no ethics approval is needed for survey studies. Data was stored on secure servers, and procedures for data handling and storage were approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Results

Sample description

A majority (64.8%) indicated use of CBD-oil, followed by hash, pot or skunk (37.1%), THC-oil (24.7%), other (8%), prescribed cannabinoid-based medicine (6.3%), and prescribed whole plant cannabis (2%) (). Of the 1.711 users who indicated use of CBD-oil, 992 were CBD-oil-only users, while the remaining 719 CBD-oil users also indicated use of other cannabis products that are conventionally higher in THC: ‘THC-oil’ or ‘Hash, pot or skunk’ or prescribed cannabis products (Marinol, Sativex, Nabilone, Bedrocan, Bediol).

Table 1. User characteristics.

Compared to respondents who used high-THC cannabis, CBD-oil-only users were more likely to be women (p < 0.001) and had a higher mean age (M 53.2 vs. M 48.8). Controlling for age and gender, CBD-oil-only users were more likely to be in full time occupation (p < 0.001). CBD-oil-only users reported treating fewer conditions compared to respondents who used high-THC cannabis (M 2.6 vs. M 3.7 (p < 0.001)) and were less likely to report use of CaM for mental health conditions (p < 0.001), chronic pain (p < 0.001), sleep disturbances (p < 0.001), and stress (p < 0.001), after controlling for age and gender. There was no difference between CBD-oil-only users and respondents who used high-THC cannabis in reporting use of CaM for treatment of somatic conditions. After controlling for age and gender, CBD-oil-only users were more likely to be daily users (p < 0.001), less likely to have recreational experience with cannabis (p < 0.001), and less likely to hold a prescription for medical cannabis (p < 0.001).

Experienced symptom relief

Compared to respondents who also used high-THC cannabis, CBD-oil-only users reported fewer symptoms relived by CaM (M 6.4 vs. M 3.6 (p < 0.001)) and had higher odds of reporting ‘no effect on any symptoms’ (OR 1.75 (p < 0.05)), after controlling for age, gender, and types of condition treated with CaM (). Further, CBD-oil-only users indicated relief from all 17 possible symptoms significantly less frequently compared to respondents who used high-THC cannabis, after controlling for age, gender, and types of conditions treated with CaM ().

Experienced effect on symptoms

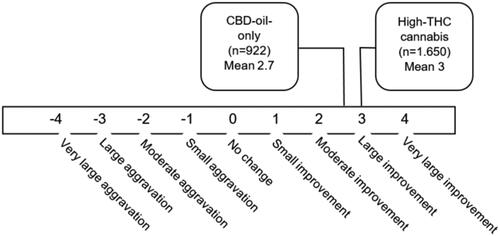

For every condition indicated, users of CaM were asked to indicate how cannabis affected the symptoms of their condition on a 9-point Likert scale. Users of CBD-oil-only indicated a mean effect of M 2.7, which was slightly lower compared to respondents who used high-THC cannabis (M 3), however after controlling for age and gender this difference was not significant ().

Figure 1. Experienced effect of cannabis on symptoms related to condition treated. Mean effect across all condition for users of high-THC cannabis and users of CBD-oil-only.

Table 2. Symptoms relieved by use of CaM.

Experienced effect on pain

Respondents indicating pain as a symptom relieved by CaM rated their experienced pain with and without the use of CaM on a pain VAS. The average reduction in pain level reported by users of CBD-oil-only (4.5 reduction), was comparable to the average reduction in pain level reported by respondents who used high-THC cannabis (4.6 reduction) (). After controlling for age and gender there was a small imrpovement favouring CBD-oil-only use for pain reduction (See Appendix B).

Table 3. Effect of CaM on pain and sleep.

Experienced effect on sleep

Respondents indicating sleep as a symptom relived by CaM reported the number of hours of sleep at night with and without the use of CaM. CBD-oil-only users reported an average increase of 2.7 hours of sleep from the use of CaM, compared to 3.2 hours for respondents who used high-THC cannabis (). However, the difference was non-significant after controlling for age and gender. Of note, a larger proportion of CBD-oil-only users (27.2%) indicated that their improvement in sleep was not quantitative, but qualitative, compared to respondents who also used high-THC cannabis (17,3%) (p < 0.001).

Experienced side-effects

The most frequent side-effects reported from CBD-oil-only users were dryness of mouth (6.4%), diarrhea (4.7%), increased tiredness (3.5%), and headache (3.5%) (). For respondents who used high-THC cannabis, the most frequent side-effects reported were dryness of mouth (32.7%), being high (24.4%), red eyes (20.9%), memory impairment (12.8%), and increased tiredness (11.5%). Compared to respondents who used high-THC cannabis, CBD-oil-only users were more likely to report ‘no side-effects of cannabis’ (OR 2.90 (CI: 2.42–3.48) (p < 0.001). Moreover, CBD-oil-only users reported fewer side-effects from use of CaM compared to users of high-THC cannabis (M 0.4 vs. M 1.5, (p < 0.001)). CBD-oil-only users were also less likely to report experiencing dryness of mouth, increased tiredness, sweating, dizziness, palpilations, memory impairment, being high, muscle fatigue, red eyes, thoughts of worry, and anxiety, compared to respondents who used high-THC cannabis.

Table 4. Side effects from use of CaM.

Discussion

Based on a survey among a large, self-selected sample of Danish users of CaM, we explored potential differences between people who used CBD-oil-only and people who used high-THC cannabis, with respect to experienced number of symptoms relieved, overall effect on symptoms, effects on pain and sleep, and side-effects.

We found group differences in terms of demographics and conditions treated with CaM. Compared to respondents who also used high-THC cannabis products, CBD-oil-only users were more likely to be women, older, and in full time occupation. As for conditions, CBD-oil-only users reported treating fewer conditions and were less likely to report use of CaM for mental health conditions, chronic pain, sleep disturbances, and stress. Further, CBD-oil-only users reported fewer symptoms relieved from use of CaM and a slightly lower symptom improvement. The experienced effects on pain and sleep reported by the CBD-oil-only users were comparable to that of users of high-THC products. Finally, CBD-oil-only users reported fewer side-effects and were more likely to report ‘no side-effects’ from use of CaM compared to users who also used- high-THC products. Overall, our study findings indicate that the experienced effects and symptom relief may be less prominent among users of CBD-oil-only compared to users who also used high-THC products. However, it should be noted that CBD-oil-only users reported a mean improvement close to the category ‘large improvement.’ Also, CBD-oil-only users report markedly fewer side-effects compared to users who also used high-THC cannabis products, as well as comparable effects on pain and sleep.

Experienced effects of CBD products

Our findings on self-reported symptom improvement from CBD-oil-only use are in line with other surveys exploring user experiences with therapeutic use of CBD products across Europe and the U.S. (Corroon & Phillips, Citation2018; Fortin et al., Citation2021; Moltke & Hindocha, Citation2021; Schilling et al., Citation2021; Wheeler et al., Citation2020). For example, in a survey based on a convenience sample of CBD users, 1.483 respondents indicated medicinal use, primarily for pain conditions, anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders, of which the majority indicated that CBD products treated their condition ‘very well’ (35.8%) or ‘moderately well’ (29.5%) (Corroon & Phillips, Citation2018). Also, recent observational studies of clinical use of CBD products over time (3 weeks − 6 months) in New Zealand (Gulbransen et al., Citation2020), Canada (Rapin et al., Citation2021), and the U.S. (Shannon et al., Citation2019) indicate a positive impact of CBD products on pain and mental health for some patients. Moreover, three U.S. observational studies following medical cannabis patients over time (3 months − 1 year) explored subtypes of cannabis and found that use of CBD-dominant cannabis products were associated with improvements in mood (Gruber et al., Citation2021; Martin et al., Citation2021; Sagar et al., Citation2021), as well as lower scores on depression (Martin et al., Citation2021) and anxiety (Sagar et al., Citation2021). Taken together, these studies indicate that some users experience relief from pain and mental health conditions when using cannabis products with high CBD and low THC. More research is needed to examine the short- and long-term efficacy and safety of clinical use of CBD-dominant cannabis products, including both placebo-controlled RCTs and longitudinal studies exploring user experiences and treatment outcomes.

Comparing CBD products to high-THC products in naturalistic settings

Our finding that users of CBD products report fewer side-effects compared to those who used high-THC cannabis is consistent with the current consensus on the relative safety of CBD (Iffland & Grotenhermen, Citation2017; World Health Organization: Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, Citation2018) and the current knowledge from cannabinoid science, indicating that high concentrations of THC are associated with the adverse events conventionally ascribed to cannabis (Curran et al., Citation2019; Di Forti et al., Citation2019; Freeman et al., Citation2018; Morgan et al., Citation2018; Quattrone et al., Citation2021). Further, in recent years, studies have emerged that explore the acute effects of various subtypes of cannabis in naturalistic settings. For instance, a recent study comparing acute objective and subjective intoxication effects of THC-dominant vs. CBD-dominant cannabis concentrates, found that the CBD-dominant concentrate invoked positive mood effects, lower intoxication, and an absence of undesirable effects associated with the THC-dominant concentrate (Drennan et al., Citation2021). These findings suggest that CBD-dominant cannabis products may produce less intense effects compared to high-THC products and the findings align with our study findings on CBD-oil-only users reporting a slightly lower symptom relief and fewer side-effects from use of CaM, when compared to users of CaM with a higher THC content. Moreover, recent studies utilizing large-scale digital self-report of short-term (2–4 hours) symptom relief from self-administration of whole plant cannabis products, found that only variation in THC concentration was associated with symptom relief in pain (Li et al., Citation2019) and depression (Li et al., Citation2020), while variation in CBD concentration was not predictive of significant symptom changes or experienced side-effects. These study findings could indicate that potential therapeutic effects of CBD are negligible, at least in the short term, and the findings contrast with the symptom relief reported by CBD-oil-only users in our study. The discrepancy could be explained by a variety of factors, such as variations in mode of intake and dose, temporal differences (short term or long term), the potential for substantial placebo effects in our study population, etc. Also, previous user experience with cannabis is a relevant factor, as the participants in the studies by Li et al. are likely to have previous experience with cannabis use and may have developed a tolerance to, and a preference for, high-THC products over time. In contrast, most CBD-oil-only users (90.2%) in our study reported being cannabis novices before they started using CBD-oil as medicine and may therefore be more susceptible to the effects of CBD. Finally, it is worth noting that the CBD-oils used by respondents in our study may contain higher concentrations of THC, despite being advertised as being below 0.2% THC, as findings from Department of Forensic Medicine at the University of Southern Denmark show, that these products have a THC content that range between 0,0%-1.0% THC (Eriksen & Christoffersen, Citation2020). Thus, the additional THC may explain some of the symptom improvement reported by the CBD-oil-only users. Lastly, experienced differences between users of CBD-oil-only, compared to those who used high-THC cannabis, may also be related to differences in cannabis use practices. For instance, a recent survey, found that CBD-dominant users, use cannabis at a lower frequency and amount, compared to THC-dominant users (Fedorova et al., Citation2021), indicating a more medicinally oriented cannabis use among those that favour CBD-dominant cannabis.

Addressing use of low-THC cannabis products in Denmark

The legal changes in Denmark that allow sale of cannabis products with less than 0.2% THC were intended to permit the use of hemp in cosmetics and food, but it inadvertently facilitated a grey market for low-THC cannabis products high in CBD used for medicinal purpose, and possibly also for recreational purposes (Andersen, Citation2022). Currently, users of these products are de facto decriminalized, free to buy, possess, and consume the products, as long as the products do not exceed the THC threshold of 0.2%. However, these users are left navigating an unregulated market, where the products in principle are legal to sell, unless they violate the Danish Medicines Act, which can only be decided after an examination by the Danish Medicines Agency on a case by case basis (Danish Medicines Agency, Citation2018). Consequently, users are left navigating an unregulated market that exists in a legal grey area. The current situation presents several public health issues that need to be addressed; for one, the consumption of these products without medical supervision presents a considerable health risk, due to the lack of guidance on contraindications and potential interaction effects of CBD with other prescription drugs (MacCallum & Russo, Citation2018). Secondly, the products are not regulated for cannabinoid content and some CBD-oils may contain THC concentrations above the 0.2% limit (Eriksen & Christoffersen, Citation2020). This is hazardous to the user, as purchase and possession of such cannabis products are illegal according to the Danish Act on Euphoriant Substances, punishable by a fine (270 euro) and visible for two years on the private criminal record and for ten years on the public criminal record. Also, it will expose the user to a higher THC content, and while these concentrations may be negligible in terms of producing a ‘high,’ a small proportion (0.7%) of CBD-oil-only users, in our study, reported experiencing a high as a side effect from use. Potential explanations for this finding include placebo effects, report error, or products with higher amounts of THC than advertised. Also, the mode of ingestion may play a role, as the psychoactive effects of THC are greater and longer lasting when cannabis is ingested, as opposed to when inhaled (Barrus et al., Citation2016; Marangoni & Marangoni, Citation2019). Thirdly, illegal cannabis products have been found to contain natural contaminants related to production, such as fungi, bacteria, heavy metals and other chemicals, which may pose health hazards (Lenton et al., Citation2018; National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, Citation2017). Recent tests of European CBD-oils show, that some oils contain carcinogens at a level that far exceeded the maximum levels set by the EU (International Medical Cannabis Patient Coalition, Citation2017); in one case, a CBD-oil labelled as ‘organic’ was found to contain traces of a pesticide that was banned 20 years ago (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Citation2020). Fourth, the marketing of CBD-products contain health claims that far exceeds the current evidence for efficacy of CBD (Evans, Citation2020; Hsu, Citation2019; Lachenmeier & Walch, Citation2020; Leas et al., Citation2019; Wagoner et al., Citation2021; Zenone et al., Citation2021), which may be a significant contributor to the present popularity of CBD products. In Denmark, recent examples of aggressive marketing of low-THC cannabis products involve Instagram influencers with thousands of followers, that have been hired by a seller to advertise smoked CBD-products, suggesting that the products can be used for pleasure or to relieve stress and sleep problems (Grosen, Citation2022; Krarup, Citation2022). The aggressive marketing may lead to increased prevalence of use among youth in Denmark, a trend that has already been observed in other European countries, such as France, Switzerland, and Italy (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Citation2020). While increased use of CBD-products may present a public health benefit in instances where cannabis users replace high-THC products with CBD-products (Fortin, Di Beo, et al., Citation2022; Thomsen et al., Citation2021), emerging use among cannabis novices may result in adverse net public health outcomes (Manthey, Citation2019). Lastly, in recent years, the Danish low-THC cannabis market has moved beyond the focus on CBD, with the emergence of products marketed for their high amount of cannabinoids with THC-like properties, such as Hexahydrocannabinol (HHC), which was subsequently made illegal (The Ministry of the Interior and Health, Citation2023). At present, the potent THC-like cannabinoid, tetrahydrocannabiphorol (THC-P), discovered in late 2019 (Citti et al., Citation2019), also appears to have found its way to (currently) legal cannabis products sold in Danish web shops (Weedshop, Citation2022), despite lack of knowledge on the health implications of use of cannabis high in this cannabinoid. Thus, it is of great importance to monitor use of low-THC cannabis products for both recreational and medicinal purposes, particularly among Danish youth. Moreover, an increased focus and regulation of advertising, content testing, and labeling is likely to reduce the public health harms associated with low-THC cannabis use.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several limitations. Most importantly, it was not a study on the efficacy of CaM as this should be explored in RCTs. The study used a self-selected convenience sample, which may cause selection bias, as the sample is likely to include more users with positive experiences/opinions about CaM, as well as users who are engaged with the topic on social media and who are familiar with online surveys. As a consequence, the sample may not be representative of the general population of CaM users in Denmark. Moreover, the respondents may have been influenced by self-reporting biases, such as recall bias, confirmation bias, and social desirability bias (Althubaiti, Citation2016; Krumpal, Citation2013), and may have exaggerated the experienced effects of CaM or underreported adverse effects. To protect anonymity, the respondents’ IP-addresses were not made accessible to the researchers, and thus we cannot rule out that there may be multiple responses from the same person using different IP-addresses. Moreover, the dummy variable constructed for this study only discriminate between users who only indicated using CBD-oil (CBD-oil-only) (1) and users who indicated using at least one cannabis product conventionally higher in THC (0), and therefore it does not account for the fact that a subset of users of high THC cannabis products (n = 716) reported co-use of CBD-oils, which may impact their user experiences. Further, the subgroups of users that are compared vary with respect to type of cannabis product used, as we compare CBD-oil-only users, to users of various types of high-THC products (oils, hash, pot etc). Likewise, the response categories, such as ‘THC oil’ and ‘CBD oil,’ likely cover a wide variety of products. Also, there are significant differences in types of conditions treated and number of treated conditions between the subgroups that are compared in the study, which may impact the experienced relief associated with use of CaM. Lastly, assessment of improvements with respect to pain and sleep were measured at the same time and are thus only pseudo-longitudinal data.

Despite these limitations, this study also has considerable strengths, as it explores the experiences related to subtypes of cannabis in a large sample of medicinal users navigating in the unregulated cannabis market in Denmark, with great relevance to public health. Also, while the use of a self-selected convenience sample holds several limitations, an anonymous online survey is a great tool to gain access to ‘hidden populations,’ where the behaviour of interest is either stigmatized or illegal, or both (Barratt et al., Citation2015; Dunlap & Johnson, Citation1998). In fact, self-report surveys have been found to be a reliable predictor of drug use, when compared to biological measures (Bharat et al., Citation2023). Further, this method has been shown to prompt honest responses and self-disclosure (Heiervang & Goodman, Citation2011; Joinson & Paine, Citation2007), as it provides a favorable setting for disclosure of delicate topics (Kays et al., Citation2013).

Conclusion

Our study findings are in line with several studies indicating that some users of CaM experience substantial symptom relief in a wide range of conditions, when using cannabis products with high CBD concentrations and limited THC concentrations. The study findings are in accordance with emerging research suggesting that cannabis products with high CBD concentrations produce less intense effects compared to high-THC cannabis products, while also producing fewer side-effects. With the emerging popularity of low-THC cannabis products, there is an urgent need to monitor trends in use of these products, both medicinal and recreational, particularly among youth. Increased regulation of the current grey market for low-THC cannabis products in Denmark is likely to reduce the potential harms associated with use.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Althubaiti, A. (2016). Information bias in health research: Definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 9, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S104807

- Andersen, M. (2022). Cannabis is legally sold as potpourri, but is it actually smoked? (Cannabis bliver lovligt solgt som potpourri, men bliver det faktisk røget?). Retrieved 13.12 2022 from https://www.tv2lorry.dk/koebenhavn/cannabis-bliver-lovligt-solgt-som-potpourri-men-bliver-det-faktisk-roeget?fbclid=IwAR2wSTscv6Fh3NxnL4p6-NCUQGZBnmovsjbswSgxx5rr3vH7OPXnpdttLrg

- Arnold, J. C., McCartney, D., Suraev, A., & McGregor, I. S. (2022). The safety and efficacy of low oral doses of cannabidiol: An evaluation of the evidence. Clinical and Translational Science, 16(1), 10–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.13425

- Avisen, D. (2017, 16 juni). Søs Egelind om pot: ingen medicin kunne lindre paa den måde. https://www.avisen.dk/soes-egelind-om-pot-ingen-medicin-kunne-lindre-paa-d_449459.aspx

- Banerjee, R., Erridge, S., Salazar, O., Mangal, N., Couch, D., Pacchetti, B., & Sodergren, M. H. (2022). Real world evidence in medical cannabis research. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science, 56(1), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-021-00346-0

- Barratt, M. J., Ferris, J. A., Zahnow, R., Palamar, J. J., Maier, L. J., & Winstock, A. R. (2017). Moving on from representativeness: Testing the utility of the Global Drug Survey. Substance Abuse, 11, 1178221817716391. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178221817716391

- Barratt, M. J., Potter, G. R., Wouters, M., Wilkins, C., Werse, B., Perälä, J., Pedersen, M. M., Nguyen, H., Malm, A., Lenton, S., Korf, D., Klein, A., Heyde, J., Hakkarainen, P., Frank, V. A., Decorte, T., Bouchard, M., & Blok, T. (2015). Lessons from conducting trans-national Internet-mediated participatory research with hidden populations of cannabis cultivators. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 26(3), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.12.004

- Barrus, D. G., Capogrossi, K. L., Cates, S. C., Gourdet, C. K., Peiper, N. C., Novak, S. P., Lefever, T. W., & Wiley, J. L. (2016). Tasty THC: Promises and challenges of cannabis edibles. Methods Report, 2016, 1611. https://doi.org/10.3768/rtipress.2016.op.0035.1611

- Bechgaard, A. T. (2014, 24 feb). Patients seek advice on Facebook on the use of illegal cannabis (Syge søger råd på Facebook om brugen af ulovlig cannabis). Dr.dk. https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/indland/syge-soeger-raad-paa-facebook-om-brugen-af-ulovlig-cannabis

- Bharat, C., Webb, P., Wilkinson, Z., McKetin, R., Grebely, J., Farrell, M., Holland, A., Hickman, M., Tran, L. T., Clark, B., Peacock, A., Darke, S., Li, J.-H., & Degenhardt, L. (2023). Agreement between self-reported illicit drug use and biological samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 118(9), 1624–1648. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16200

- Bilbao, A., & Spanagel, R. (2022). Medical cannabinoids: A pharmacology-based systematic review and meta-analysis for all relevant medical indications. BMC Medicine, 20(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02459-1

- Black, N., Stockings, E., Campbell, G., Tran, L. T., Zagic, D., Hall, W. D., Farrell, M., & Degenhardt, L. (2019). Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 6(12), 995–1010. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30401-8

- Blaskovich, M. A. T., Kavanagh, A. M., Elliott, A. G., Zhang, B., Ramu, S., Amado, M., Lowe, G. J., Hinton, A. O., Pham, D. M. T., Zuegg, J., Beare, N., Quach, D., Sharp, M. D., Pogliano, J., Rogers, A. P., Lyras, D., Tan, L., West, N. P., Crawford, D. W., … Thurn, M. (2021). The antimicrobial potential of cannabidiol. Communications Biology, 4(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01530-y

- Blessing, E. M., Steenkamp, M. M., Manzanares, J., & Marmar, C. R. (2015). Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for anxiety disorders. Neurotherapeutics, 12(4), 825–836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-015-0387-1

- Boehnke, K. F., Häuser, W., & Fitzcharles, M.-A. (2022). Cannabidiol (CBD) in Rheumatic Diseases (Musculoskeletal Pain). Current Rheumatology Reports, 24(7), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-022-01077-3

- Bonaccorso, S., Ricciardi, A., Zangani, C., Chiappini, S., & Schifano, F. (2019). Cannabidiol (CBD) use in psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. Neurotoxicology, 74, 282–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2019.08.002

- Bonn-Miller, M. O., Loflin, M. J., Thomas, B. F., Marcu, J. P., Hyke, T., & Vandrey, R. (2017). Labeling accuracy of cannabidiol extracts sold online. JAMA, 318(17), 1708–1709. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.11909

- Britch, S. C., Babalonis, S., & Walsh, S. L. (2021). Cannabidiol: Pharmacology and therapeutic targets. Psychopharmacology, 238(1), 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-020-05712-8

- Brix, L. (2020, 24 November). Chaos in the content of cannabis oils (Kaos i indholdet af cannabisolier). Videnskab.dk. https://videnskab.dk/krop-sundhed/kaos-i-indholdet-af-cannabisolier

- CBD-Helten. (2022). Retrieved December 13, from https://www.cbd-helten.dk/

- Chesney, E., Oliver, D., Green, A., Sovi, S., Wilson, J., Englund, A., Freeman, T. P., & McGuire, P. (2020). Adverse effects of cannabidiol: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(11), 1799–1806. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-020-0667-2

- Chesney, E., Oliver, D., & McGuire, P. (2021). Cannabidiol (CBD) as a novel treatment in the early phases of psychosis. Psychopharmacology, 239(5), 1179–1190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-021-05905-9

- Citti, C., Linciano, P., Russo, F., Luongo, L., Iannotta, M., Maione, S., Laganà, A., Capriotti, A. L., Forni, F., Vandelli, M. A., Gigli, G., & Cannazza, G. (2019). A novel phytocannabinoid isolated from Cannabis sativa L. with an in vivo cannabimimetic activity higher than Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol: Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabiphorol. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 20335. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56785-1

- Colizzi, M., & Bhattacharyya, S. (2017). Does Cannabis Composition Matter? Differential Effects of Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol on Human Cognition. Current Addiction Reports, 4(2), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-017-0142-2

- Corroon, J., & Phillips, J. A. (2018). A Cross-Sectional Study of Cannabidiol Users. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 3(1), 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2018.0006

- Cuculiza, M. (2019, January 19). Cannabisassociation sounds the alarm: The CBD-marked is a pure wild west (Cannabisforening slår alarm: CBD-markedet er et rent wild west.). Sundhedspolitisk tidsskrift. https://sundhedspolitisktidsskrift.dk/nyheder/1706-cannabis-forening-slar-alarm-cbd-markedet-er-et-rent-wild-west.html

- Curran, H. V., Freeman, T. P., Mokrysz, C., Lewis, D. A., Morgan, C. J., & Parsons, L. H. (2016). Keep off the grass? Cannabis, cognition and addiction. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 17(5), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.28

- Curran, H. V., Hindocha, C., Morgan, C. J., Shaban, N., Das, R. K., & Freeman, T. P. (2019). Which biological and self-report measures of cannabis use predict cannabis dependency and acute psychotic-like effects? Psychological Medicine, 49(9), 1574–1580. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171800226X

- Damløv, L. (2016, October 11). Cannabis sellers on the internet mislead sick people (Cannabis-sælgere på nettet vildleder syge mennesker). Danmarks Radio https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/indland/cannabis-saelgere-paa-nettet-vildleder-syge-mennesker

- Danish Medicines Agency. (2021, May 11). List of products determined to be medicines. https://laegemiddelstyrelsen.dk/en/licensing/medicine-or-not/list-of-products-determined-to-be-medicines/

- Danish Medicines Agency, L. (2018, October 11). Change of the THC limit as of 1 July 2018. Retrieved 24.03.2020 from https://laegemiddelstyrelsen.dk/en/special/medicinal-cannabis/citizens/change-of-the-thc-limit-as-of-1-july-2018/

- Danske Patienter. (2020, February 25). Patients opinions on and experiences with cannabis as medicine (Patienters holdninger til og erfaringer med cannabis Som Medicin) Retrieved 19.10.2021 from https://danskepatienter.dk/sites/danskepatienter.dk/files/media/Publikationer%20-%20Eksterne/A_Danske%20Patienter%20%28eksterne%29/rapport_cannabis_som_medicin.pdf

- Di Forti, M., Marconi, A., Carra, E., Fraietta, S., Trotta, A., Bonomo, M., Bianconi, F., Gardner-Sood, P., O’Connor, J., Russo, M., Stilo, S. A., Marques, T. R., Mondelli, V., Dazzan, P., Pariante, C., David, A. S., Gaughran, F., Atakan, Z., Iyegbe, C., … Murray, R. M. (2015). Proportion of patients in south London with first-episode psychosis attributable to use of high potency cannabis: A case-control study. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 2(3), 233–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00117-5

- Di Forti, M., Quattrone, D., Freeman, T. P., Tripoli, G., Gayer-Anderson, C., Quigley, H., Rodriguez, V., Jongsma, H. E., Ferraro, L., La Cascia, C., La Barbera, D., Tarricone, I., Berardi, D., Szöke, A., Arango, C., Tortelli, A., Velthorst, E., Bernardo, M., Del-Ben, C. M., … Murray, R. M. (2019). The contribution of cannabis use to variation in the incidence of psychotic disorder across Europe (EU-GEI): A multicentre case-control study. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 6(5), 427–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30048-3

- Dr1. (2017, January 24). Søs and the fight for cannabis (Søs og kampen om cannabis) Retrieved March 20, 2019, from https://www.dr.dk/drtv/serie/soes-og-kampen-om-cannabis_19010

- Dr2. (2014, February 24). Dr2 undersøger: Syge danskere på hashmedicin (Dr2 Explores: Sick Danes on hash medicine). https://www.dr.dk/tv/se/dr2-undersoeger/dr2-undersoeger-syge-danskere-pa-hashmedicin?app_mode=true&platform=undefined

- Drennan, M., Karoly, H., Bryan, A., Hutchison, K., & Bidwell, L. (2021). Acute objective and subjective intoxication effects of legal-market high potency THC-dominant versus CBD-dominant cannabis concentrates. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 21744. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01128-2

- Dunlap, E., & Johnson, B. D. (1998). Gaining access to hidden populations: Strategies for gaining cooperation of drug sellers/dealers and their families in ethnographic research. Drugs & Society, 14(1–2), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1300/J023v14n01_11

- Englund, A., Freeman, T. P., Murray, R. M., & McGuire, P. (2017). Can we make cannabis safer? The Lancet. Psychiatry, 4(8), 643–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30075-5

- Englund, A., Oliver, D., Chesney, E., Chester, L., Wilson, J., Sovi, S., De Micheli, A., Hodsoll, J., Fusar-Poli, P., Strang, J., Murray, R. M., Freeman, T. P., & McGuire, P. (2022). Does cannabidiol make cannabis safer? A randomised, double-blind, cross-over trial of cannabis with four different CBD: THC ratios. Neuropsychopharmacology, 48(6), 869–876. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-022-01478-z

- Eriksen, T., & Christoffersen, D. J. (2020, August 19). (Have you also ingested cannabis without knowing it? (Har du også indtaget cannabis uden at vide det?). Retrieved May 06, 2022, from https://videnskab.dk/forskerzonen/krop-sundhed/har-du-ogsaa-indtaget-cannabis-uden-at-vide-det

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2020). Low-THC cannabis products in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union Retrieved from https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/ad-hoc-publication/low-thc-cannabis-products-europe_en

- Evans, D. G. (2020). Medical fraud, mislabeling, contamination: All common in CBD products. Missouri Medicine, 117(5), 394.

- Fasinu, P. S., Phillips, S., ElSohly, M. A., & Walker, L. A. (2016). Current status and prospects for cannabidiol preparations as new therapeutic agents. Pharmacotherapy, 36(7), 781–796. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1780

- Fedorova, E. V., Wong, C. F., Ataiants, J., Iverson, E., Conn, B. M., & Lankenau, S. E. (2021). Cannabidiol (CBD) and other drug use among young adults who use cannabis in Los Angeles. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 108648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108648

- Fortin, D., Di Beo, V., Massin, S., Bisiou, Y., Carrieri, P., & Barré, T. (2021). Reasons for using cannabidiol: A cross-sectional study of French cannabidiol users. Journal of Cannabis Research, 3(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42238-021-00102-z

- Fortin, D., Di Beo, V., Massin, S., Bisiou, Y., Carrieri, P., & Barré, T. (2022). A “Good” Smoke? The off-label use of cannabidiol to reduce cannabis Use. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 829944. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.829944

- Fortin, D., Marcellin, F., Carrieri, P., Mancini, J., & Barré, T. (2022). Medical cannabis: Toward a new policy and health model for an ancient medicine. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 904291. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.904291

- Fortin, D., & Massin, S. (2020). Medical cannabis: Thinking out of the box of the healthcare system. Journal de gestion et d’economie de la sante, 2(2), 110–118. https://www.cairn.info/revue-journal-de-gestion-et-d-economie-de-la-sante-2020-2-page-110.htm

- Freeman, A. M., Petrilli, K., Lees, R., Hindocha, C., Mokrysz, C., Curran, H. V., Saunders, R., & Freeman, T. P. (2019). How does cannabidiol (CBD) influence the acute effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in humans? A systematic review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, 696–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.036

- Freeman, T., & Winstock, A. (2015). Examining the profile of high-potency cannabis and its association with severity of cannabis dependence. Psychological Medicine, 45(15), 3181–3189. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001178

- Freeman, T. P., Craft, S., Wilson, J., Stylianou, S., ElSohly, M., Di Forti, M., & Lynskey, M. T. (2020). Changes in delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) concentrations in cannabis over time: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 116(5), 1000–1010. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15253

- Freeman, T. P., Hindocha, C., Baio, G., Shaban, N. D. C., Thomas, E. M., Astbury, D., Freeman, A. M., Lees, R., Craft, S., Morrison, P. D., Bloomfield, M. A. P., O’Ryan, D., Kinghorn, J., Morgan, C. J. A., Mofeez, A., & Curran, H. V. (2020). Cannabidiol for the treatment of cannabis use disorder: A phase 2a, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, adaptive Bayesian trial. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7(10), 865–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30290-X

- Freeman, T. P., van der Pol, P., Kuijpers, W., Wisselink, J., Das, R. K., Rigter, S., van Laar, M., Griffiths, P., Swift, W., Niesink, R., & Lynskey, M. T. (2018). Changes in cannabis potency and first-time admissions to drug treatment: A 16-year study in the Netherlands. Psychological Medicine, 48(14), 2346–2352. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717003877

- Gardiner, K. M., Singleton, J. A., Sheridan, J., Kyle, G. J., & Nissen, L. M. (2019). Health professional beliefs, knowledge, and concerns surrounding medicinal cannabis–a systematic review. PLoS One, 14(5), e0216556. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216556

- Goodman, S., Wadsworth, E., Schauer, G., & Hammond, D. (2020). Use and perceptions of cannabidiol products in Canada and in the United States. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 7(3), 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2020.009

- Graham, M., Lucas, C. J., Schneider, J., Martin, J. H., & Hall, W. (2020). Translational hurdles with cannabis medicines. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 29(10), 1325–1330. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4999

- Grosen, J. (2022). Young influencers advertise cannabis products on Instagram: "It’s troubling" (Unge influencere reklamerer for cannabisprodukter på Instagram: “Det er bekymrende”). Radio4. Retrieved November 04, 2022, from https://www.radio4.dk/nyheder/unge-influencere-reklamerer-for-cannabisprodukter-paa-instagram-og-det-moeder-kritik/

- Grotenhermen, F., & Schnelle, M. (2003). Survey on the medical use of cannabis and THC in Germany. Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics, 3(2), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1300/J175v03n02_03

- Gruber, S. A., Smith, R. T., Dahlgren, M. K., Lambros, A. M., & Sagar, K. A. (2021). No pain, all gain? Interim analyses from a longitudinal, observational study examining the impact of medical cannabis treatment on chronic pain and related symptoms. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(2), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000435

- Gulbransen, G., Xu, W., & Arroll, B. (2020). Cannabidiol prescription in clinical practice: An audit on the first 400 patients in New Zealand. BJGP Open, 4(1), bjgpopen20X101010. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen20X10101

- Gustavsen, S., Søndergaard, H., Andresen, S., Magyari, M., Sørensen, P., Sellebjerg, F., & Oturai, A. (2019). Illegal cannabis use is common among Danes with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 33, 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2019.05.008

- Hamilton, L. C. (2012). Statistics with Stata: Version 12 (Vol. 12). Cengage Learning.

- Hazekamp, A. (2018). The trouble with CBD Oil. Medical Cannabis and Cannabinoids, 1(1), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1159/000489287

- Hazekamp, A., Ware, M. A., Muller-Vahl, K. R., Abrams, D., & Grotenhermen, F. (2013). The medicinal use of cannabis and cannabinoids–an international cross-sectional survey on administration forms. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45(3), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2013.805976

- Heiervang, E., & Goodman, R. (2011). Advantages and limitations of web-based surveys: Evidence from a child mental health survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 46(1), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0171-9

- Houborg, E., & Enghoff, O. (2018). Cannabis in Danish newspapers. Tidsskrift for Forskning i Sygdom og Samfund, 15(28), 173–204. https://doi.org/10.7146/tfss.v15i28.107265

- Hsu, T. (2019, August 13). Ads Pitching CBD as a Cure-All Are Everywhere. Oversight Hasn’t Kept Up. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/13/business/media/cbd-marijuana-fda.html

- Iffland, K., & Grotenhermen, F. (2017). An Update on Safety and Side-effects of Cannabidiol: A Review of Clinical Data and Relevant Animal Studies. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 2(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2016.0034

- International Medical Cannabis Patient Coalition. (2017). Warning for consumers of CBD and cannabis oils sold on the EU market. Retrieved April 30, 2022 from http://imcpc.org/warning-for-consumers-of-cbd-and-cannabis-oils-sold-on-the-eu-market/

- Iseger, T. A., & Bossong, M. G. (2015). A systematic review of the antipsychotic properties of cannabidiol in humans. Schizophrenia Research, 162(1–3), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2015.01.033

- Jensen, M. P., Chen, C., & Brugger, A. M. (2003). Interpretation of visual analog scale ratings and change scores: A reanalysis of two clinical trials of postoperative pain. The Journal of Pain, 4(7), 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1526-5900(03)00716-8

- Johnson, E., Kilgore, M., & Babalonis, S. (2022). Cannabidiol (CBD) product contamination: Quantitative analysis of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) concentrations found in commercially available CBD products. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 237, 109522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109522

- Joinson, A. N., & Paine, C. B. (2007). Self-disclosure, privacy and the Internet. In K. Y. A. M. Adam, N. Joinson, & Tom Postmes (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of Internet psychology (pp. 235–250). Oxford University Press.

- Kays, K. M., Keith, T. L., & Broughal, M. T. (2013). Best practice in online survey research with sensitive topics. In Advancing research methods with new technologies (pp. 157–168). IGI Global.

- Krarup, N. (2022). Diamond daughter in cannabis-fuckup (Diamantdatter i cannabisbrøler). Ekstra Bladet, 12, 30. https://ekstrabladet.dk/underholdning/dkkendte/diamantdatter-i-cannabisbroeler/9568442

- Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025–2047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9

- Kvamme, S. L. (2022a). Do-It-Yourself medicine. Exploring the use of cannabis as medicine in Denmark Aarhus University]. Aarhus BSS. https://psy.au.dk/fileadmin/site_files/filer_rusmiddelforskning/dokumenter/ph.d.-afhandlinger/Sinikka_L._Kvamme._Do-It-Yourself_medicine._Exploring_the_use_of_cannabis_as_medicin_in_Denmark.pdf

- Kvamme, S. L. (2022b). With medicine in mind? Exploring the relevance of having recreational experience when becoming a medicinal cannabis user. contemporary drug problems, 49(2), 192–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/00914509211070741

- Kvamme, S. L., Pedersen, M. M., Alagem-Iversen, S., & Thylstrup, B. (2021a). Beyond the high: Mapping patterns of use and motives for use of cannabis as medicine. Nordisk Alkohol- & Narkotikatidskrift, 38(3), 270–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072520985967

- Kvamme, S. L., Pedersen, M. M., Thomsen, K. R., & Thylstrup, B. (2021b). Exploring the use of cannabis as a substitute for prescription drugs in a convenience sample. Harm Reduction Journal, 18(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00520-5

- Lachenmeier, D. W., Habel, S., Fischer, B., Herbi, F., Zerbe, Y., Bock, V., de Rezende, T. R., Walch, S. G., & Sproll, C. (2019). Are adverse effects of cannabidiol (CBD) products caused by tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) contamination? F1000Research, 8(8), 1394. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.19931.1

- Lachenmeier, D. W., & Walch, S. G. (2020). Cannabidiol (CBD): A strong plea for mandatory pre-marketing approval of food supplements. Journal of Consumer Protection and Food Safety, 15(2), 97–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00003-020-01281-2

- Leas, E. C., Nobles, A. L., Caputi, T. L., Dredze, M., Smith, D. M., & Ayers, J. W. (2019). Trends in internet searches for cannabidiol (CBD) in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 2(10), e1913853-e1913853. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13853

- Legare, C. A., Raup-Konsavage, W. M., & Vrana, K. E. (2022). Therapeutic potential of cannabis, cannabidiol, and cannabinoid-based pharmaceuticals. Pharmacology, 107(3–4), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1159/000521683

- Lenton, S., Frank, V. A., Barratt, M. J., Potter, G. R., & Decorte, T. (2018). Growing practices and the use of potentially harmful chemical additives among a sample of small-scale cannabis growers in three countries. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 192, 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.040

- Li, X., Diviant, J. P., Stith, S. S., Brockelman, F., Keeling, K., Hall, B., & Vigil, J. M. (2020). Focus: Plant-based medicine and pharmacology: The effectiveness of Cannabis Flower for Immediate Relief from Symptoms of Depression. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 93(2), 251.

- Li, X., Vigil, J. M., Stith, S. S., Brockelman, F., Keeling, K., & Hall, B. (2019). The effectiveness of self-directed medical cannabis treatment for pain. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 46, 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2019.07.022

- MacCallum, C. A., & Russo, E. B. (2018). Practical considerations in medical cannabis administration and dosing. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 49, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2018.01.004

- Manthey, J. (2019). Cannabis use in Europe: Current trends and public health concerns. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 68, 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.006

- Marangoni, I. P., & Marangoni, A. G. (2019). Cannabis edibles: Dosing, encapsulation, and stability considerations. Current Opinion in Food Science, 28, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2019.01.005

- Martin, E. L., Strickland, J. C., Schlienz, N. J., Munson, J., Jackson, H., Bonn-Miller, M. O., & Vandrey, R. (2021). Antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of medicinal cannabis use in an observational trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 729800. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.729800

- Martínez, V., Iriondo De-Hond, A., Borrelli, F., Capasso, R., Del Castillo, M. D., & Abalo, R. (2020). Cannabidiol and other non-psychoactive cannabinoids for prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders: Useful nutraceuticals? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(9), 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093067

- McGregor, I. S., Cairns, E. A., Abelev, S., Cohen, R., Henderson, M., Couch, D., Arnold, J. C., & Gauld, N. (2020). Access to cannabidiol without a prescription: A cross-country comparison and analysis. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 85, 102935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102935

- Meier, M. H. (2017). Associations between butane hash oil use and cannabis-related problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 179, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.06.015

- Ministry of Health. (2016, November 08). Agreement on medical cannabis pilot programme (Aftale om forsøgsordning med medicinsk cannabis). http://sundhedsministeriet.dk/Aktuelt/Nyheder/Medicin/2016/November/∼/media/Filer%20-%20dokumenter/Aftale-om-medicinsk-cannabis/Politisk-aftale-om-forsogsordning-med-medicinsk-cannabis.ashx

- Moltke, J., & Hindocha, C. (2021). Reasons for Cannabidiol use: A cross-sectional study of CBD users, focusing on self-perceived stress, anxiety, and sleep problems. Journal of Cannabis Research, 3(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42238-021-00061-5

- Morgan, C. J., Freeman, T. P., Hindocha, C., Schafer, G., Gardner, C., & Curran, H. V. (2018). Individual and combined effects of acute delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on psychotomimetic symptoms and memory function. Translational Psychiatry, 8(1), 181. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-018-0191-x

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. (2017). The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. NASEM. https://doi.org/10.17226/24625

- Navarrete, F., García-Gutiérrez, M. S., Gasparyan, A., Austrich-Olivares, A., & Manzanares, J. (2021). Role of cannabidiol in the therapeutic intervention for substance use disorders. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 626010. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.626010

- Nielsen, S. W., Ruhlmann, C. H., Eckhoff, L., Brønnum, D., Herrstedt, J., & Dalton, S. O. (2021). Cannabis use among Danish patients with cancer: A cross-sectional survey of sociodemographic traits, quality of life, and patient experiences. Supportive Care in Cancer, 30(2), 1181–1190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06515-z

- Pavlovic, R., Nenna, G., Calvi, L., Panseri, S., Borgonovo, G., Giupponi, L., Cannazza, G., & Giorgi, A. (2018). Quality traits of “cannabidiol oils”: Cannabinoids content, terpene fingerprint and oxidation stability of European commercially available preparations. Molecules, 23(5), 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051230

- Piomelli, D., Solomon, R., Abrams, D., Balla, A., Grant, I., Marcotte, T., & Yoder, J. (2019). Regulatory barriers to research on Cannabis and Cannabinoids: A proposed path forward. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 4(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2019.0010

- Potter, D. J., Clark, P., & Brown, M. B. (2008). Potency of Δ9–THC and other cannabinoids in cannabis in England in 2005: Implications for psychoactivity and pharmacology. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 53(1), 90–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2007.00603.x

- Potter, D. J., Hammond, K., Tuffnell, S., Walker, C., & Di Forti, M. (2018). Potency of Δ9–tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids in cannabis in England in 2016: Implications for public health and pharmacology. Drug Testing and Analysis, 10(4), 628–635. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.2368

- Quattrone, D., Ferraro, L., Tripoli, G., La Cascia, C., Quigley, H., Quattrone, A., Jongsma, H. E., Del Peschio, S., Gatto, G., Gayer-Anderson, C., Jones, P. B., Kirkbride, J. B., La Barbera, D., Tarricone, I., Berardi, D., Tosato, S., Lasalvia, A., Szöke, A., Arango, C., … Di Forti, M. (2021). Daily use of high-potency cannabis is associated with more positive symptoms in first-episode psychosis patients: The EU-GEI case–control study. Psychological Medicine, 51(8), 1329–1337. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720000082

- Rapin, L., Gamaoun, R., El Hage, C., Arboleda, M. F., & Prosk, E. (2021). Cannabidiol use and effectiveness: Real-world evidence from a Canadian medical cannabis clinic. Journal of Cannabis Research, 3(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42238-021-00078-w

- Reiman, A., Welty, M., & Solomon, P. (2017). Cannabis as a substitute for opioid-based pain medication: Patient self-report. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 2(1), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2017.0012

- Reinarman, C., Nunberg, H., Lanthier, F., & Heddleston, T. (2011). Who are medical marijuana patients? Population characteristics from nine California assessment clinics. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(2), 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2011.587700

- Rothwell, P. M. (2005). External validity of randomised controlled trials: To whom do the results of this trial apply? Lancet, 365(9453), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17670-8

- Rueda, S., Limanto, E., & Chaiton, M. (2022). Cannabis clinical research in purgatory: Canadian researchers caught between an inflexible regulatory environment and a conflicted industry. Lancet Regional Health, 7, 100171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2021.100171

- Rømer Thomsen, K., Callesen, M. B., & Ewing, S. W. F. (2017). Recommendation to reconsider examining cannabis subtypes together due to opposing effects on brain, cognition and behavior. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 156–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.05.025

- Rømer Thomsen, K., Lindholst, C., Thylstrup, B., Kvamme, S., Reitzel, L. A., Worm-Leonhard, M., Englund, A., Freeman, T. P., & Hesse, M. (2019). Changes in the composition of cannabis from 2000-2017 in Denmark: Analysis of confiscated samples of cannabis resin. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27(4), 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000303

- Sagar, K. A., Dahlgren, M. K., Lambros, A. M., Smith, R. T., El-Abboud, C., & Gruber, S. A. (2021). An observational, longitudinal study of cognition in medical cannabis patients over the course of 12 months of treatment: Preliminary results. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 27(6), 648–660. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617721000114

- Schilling, J. M., Hughes, C. G., Wallace, M. S., Sexton, M., Backonja, M., & Moeller-Bertram, T. (2021). Cannabidiol as a treatment for chronic pain: A survey of patients’ perspectives and attitudes. Journal of Pain Research, 14, 1241–1250. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S278718

- Schlag, A. K., Zafar, R. R., Lynskey, M. T., Athanasiou-Fragkouli, A., Phillips, L. D., & Nutt, D. J. (2022). The value of real world evidence: The case of medical cannabis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 1027159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1027159

- Sexton, M., Cuttler, C., Finnell, J. S., & Mischley, L. K. (2016). A cross-sectional survey of medical cannabis users: Patterns of use and perceived efficacy. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 1(1), 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2016.0007

- Shannon, S., Lewis, N., Lee, H., & Hughes, S. (2019). Cannabidiol in anxiety and sleep: A large case series. The Permanente Journal, 23(1), 18–041. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/18-041

- The Ministry of the Interior and Health. (2023). Ban on the euphoric substance HHC. Retrieved from https://www.ft.dk/samling/20222/almdel/SUU/bilag/196/2698983/index.htm

- Thomsen, K. R., Thylstrup, B., Kenyon, E. A., Lees, R., Baandrup, L., Ewing, S. W. F., & Freeman, T. P. (2021). Cannabinoids for the treatment of cannabis use disorder: New avenues for reaching and helping youth? Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 132, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.11.033

- Undonno Store. (2022). Retrieved December13, 2022, from https://www.udonnostore.com/da

- Vandrey, R., Raber, J. C., Raber, M. E., Douglass, B., Miller, C., & Bonn-Miller, M. O. (2015). Cannabinoid dose and label accuracy in edible medical cannabis products. JAMA, 313(24), 2491–2493. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.6613

- Veziari, Y., Leach, M. J., & Kumar, S. (2017). Barriers to the conduct and application of research in complementary and alternative medicine: A systematic review. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 17(1), 166. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-017-1660-0

- Wagoner, K. G., Lazard, A. J., Romero-Sandoval, E. A., & Reboussin, B. A. (2021). Health claims about cannabidiol products: A retrospective analysis of US Food and Drug Administration warning letters from 2015 to 2019. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 6(6), 559–563. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2020.0166

- Ware, M., Adams, H., & Guy, G. (2005). The medicinal use of cannabis in the UK: Results of a nationwide survey. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 59(3), 291–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00271.x

- Webb, C. W., & Webb, S. M. (2014). Therapeutic benefits of cannabis: A patient survey. Hawai’i Journal of Medicine & Public Health, 73(4), 109.

- Weedshop. (2022). Retrieved December, 13, 2022, from https://weedshop.dk/

- Wheeler, M., Merten, J. W., Gordon, B. T., & Hamadi, H. (2020). CBD (cannabidiol) product attitudes, knowledge, and use among young adults. Substance Use & Misuse, 55(7), 1138–1145. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2020.1729201

- Wise, J. (2019). European drug agency approves cannabis-based medicine for severe forms of epilepsy. BMJ, 366, l5708. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l5708

- World Health Organization: Expert Committee on Drug Dependence. (2018, 4-7 June). Cannabidiol (CBD) Critical Review Report. Retrieved 04.02.2022 from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/279948/9789241210225-eng.pdf

- Zenone, M. A., Snyder, J., & Crooks, V. (2021). Selling cannabidiol products in Canada: A framing analysis of advertising claims by online retailers. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1285. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11282-x

Appendix A

Somatic conditions (36): acne, AIDS, Alzheimer’s, asthma, Chron’s disorder, herniated disc, dystonia, eczema, epilepsy, endometriosis, fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, cataracts, hepatitis, brain damage, COPD, cancer, CFS(chronic fatigue), chronic nerve inflammation, migraine, menstrual pain, multiple sclerosis, neurodermatitis, IBS, lupus (SLE), end-of-life(palliative care), Parkinson’s, peripheral neuropathy, psoriasis, spinal cord injury, pain following operation, pain following an accident, tinnitus, trigeminal neuralgiaPsychiatric conditions (13): ADHD, anxiety, dependence (alcohol), dependence (harddrugs), dependence (prescription drugs), anorexia, autism, bipolar disorder, depression,OCD, PTSD, schizophrenia, Tourette’s/tics.