Abstract

Background

Managed Alcohol Programs (MAPs) are a harm reduction strategy for people experiencing homelessness and alcohol dependence. Despite a growing evidence base, resistance to MAPs is apparent due to limited knowledge of alcohol harm reduction and the cultural preference for abstinence-based approaches. To address this, service managers working in a not-for-profit organization in Scotland designed and delivered a program of alcohol-specific staff training as part of a larger study exploring the potential implementation of MAPs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 service managers and staff regarding their experiences of the training provided. Data were analyzed using Framework Analysis, and Lewin’s model of organizational change was applied to the findings to gain deeper theoretical insight into data relating to staff knowledge, training, and organizational change.

Findings

Participants described increased knowledge about alcohol harm reduction and MAPs, as well as increased opportunities for conversations around cultural change. Findings highlight individual- and organizational-level change is required when implementing novel harm reduction interventions like MAPs.

Conclusion

The findings have implications for the future implementation of MAPs in homelessness settings. Training can promote staff buy-in, facilitate the involvement of staff within the planning process, and change organizational culture.

Introduction

Harm reduction interventions are evidence-based approaches that aim to reduce the harms associated with drug or alcohol use. Although these approaches are extensive, and widely implemented globally in relation to drug use (Kouimtsidis et al., Citation2021), harm reduction interventions are less commonly available for those who experience alcohol dependence. The majority of harm reduction interventions that do exist for alcohol are typically at the population level, such as alcohol pricing initiatives (Ivsins et al., Citation2019). Alcohol dependence refers to cravings and tolerance for alcohol, as well as a preoccupation with alcohol, and sustained drinking, despite detrimental consequences. It is associated with a range of physical and mental health problems and wider challenges (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Citation2011). People experiencing homelessness are at increased likelihood of being alcohol dependent due to previous and ongoing challenges, including discrimination and traumatic experiences (Johnson & Chamberlain, Citation2008; McVicar et al., Citation2015; Pauly, Wallace, et al., Citation2018). Alcohol-related harm is already a key public health concern in Scotland, with a rate of 22.9 deaths per 100,000 people in 2022 (National Records of Scotland, Citation2023). This is an increase of 2% since 2021 (National Records of Scotland, Citation2023). The alcohol-related risks to those experiencing homelessness in Scotland are more than double that of the general population, with 14% of deaths among people experiencing homelessness caused by alcohol (Waugh et al., Citation2018). Treatment for alcohol dependence tends to be abstinence-based (Pauly et al., Citation2019) which works for some, however, research also provides evidence that people experiencing homelessness report a preference for harm reduction approaches (Carver et al., Citation2020).

Managed Alcohol Programs (MAPs) are a harm reduction strategy for people experiencing alcohol dependence and unstable housing and are most often provided within homelessness services across a range of settings, such as day programs, shelters/hostels, and transitional and permanent housing (Pauly, Vallance, et al., Citation2018). They provide regular measured doses of alcohol throughout the day, with the aim of improving health and social outcomes (Pauly, Vallance, et al., Citation2018). Published evidence suggests that MAPs have a range of positive outcomes, such as reduced levels of alcohol consumption (Pauly et al., Citation2019); improved quality of life (Smith-Bernardin et al., Citation2022; Stockwell et al., Citation2018); improved retention in housing (Stockwell et al., Citation2013); less harmful patterns of alcohol use (Pauly et al., Citation2019; Vallance et al., Citation2016); and reduced contact with emergency services (Podymow et al., Citation2006; Zhao et al., Citation2022). MAPs were first introduced more than 20 years ago in Canada, and currently, more than 40 exist across the country (Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, Citation2022).

Outside of Canada, MAPs have been implemented in the Republic of Ireland (Depaul, Citation2023b), Northern Ireland (Depaul, Citation2023a), and the USA (Brocious et al., Citation2021; Ristau et al., Citation2021), and there is interest in Portugal (Fuertes et al., Citation2021) and Australia to develop them (Ezard et al., Citation2018; Holmes, Citation2019). Recent research has highlighted the need for MAPs in Scotland due to the high levels of alcohol consumption among people living in hostel accommodation, and a general lack of suitable services for those experiencing homelessness and alcohol dependence (Carver et al., Citation2021; Carver, Parkes, et al., Citation2022; Parkes, Carver, Masterton, et al., Citation2021; Parkes, Carver, Matheson, et al., Citation2021). Further, a previous meta-ethnography of 23 published papers on the views of people experiencing homelessness regarding effective treatment approaches for alcohol dependence found that MAPs are perceived as an important harm reduction intervention (Carver et al., Citation2020). Indeed, since the completion of the study reported in this paper, a pilot MAP opened in 2021 in Scotland run by Simon Community Scotland (Scottish Housing News, Citation2020).

Despite a growing evidence base, and the increased implementation of MAPs outside of Canada, public and organizational resistance to MAPs continues, especially in the homelessness sector globally where a cultural preference for abstinence-based approaches is a significant barrier to successful implementation (Carver et al., Citation2021; Gaetz et al., Citation2016; Ivsins et al., Citation2019). Indeed, within the context of Scotland, an abstinence-based culture appears to be the status quo for alcohol support services. Anecdotally, this has been attributed to limited funding and resources for support for alcohol dependence and initiatives, such as wet centers, where alcohol would be allowed, as well as the influence of 12-Step programs within many services (L. Ball, personal communication, August 25, 2023). This status quo may be further confounded if people with lived experience of alcohol (or drug) challenges who work on health and social care/homelessness teams have themselves benefited from an abstinence-based treatment modality (L. Ball, personal communication, August 25, 2023). Additionally, abstinence is often required to gain access to other services, such as housing (Carver et al., Citation2021). Carver et al. (Citation2021) explored the need for alcohol harm reduction in Scotland and reported that those interviewed spoke about harm reduction almost exclusively as focused on illicit drug use, rather than alcohol use. Despite this, some staff participants in that study acknowledged the need for change in Scotland to provide harm reduction services to people for whom abstinence is unrealistic or undesirable.

In another study, Carver, Price, et al. (Citation2022) found that a lack of shared values between homelessness services staff regarding drug or alcohol harm reduction practices could lead to fragmentation within staff teams, especially in services with less supportive team environments. Indeed, in previous MAPs research in Scotland, tensions were identified concerning staff views of MAPs, especially for those who were more favorable to abstinence-based approaches (Carver, Parkes, et al. Citation2022). It was noted that some staff lacked knowledge of alcohol harm reduction approaches and, reportedly, did not understand the rationale underpinning the implementation of a MAP. Other research found that some staff were concerned around the practical application of MAPs and fearful of causing additional harm by providing alcohol to people experiencing alcohol dependence (Parkes, Carver, Masterton, et al., Citation2021; Parkes, Carver, Matheson, et al., Citation2021). These findings are supported by other international studies which report that a lack of knowledge among healthcare staff on how to deliver a novel intervention, as well as mistaken beliefs about efficacy, can have a negative impact on staff acceptance of an intervention (Harvey et al., Citation2022; Meyerson et al., Citation2020; Mutschler et al., Citation2022; Pauly et al., Citation2021).

When exploring the influence that staff knowledge may have on intervention implementation, research with healthcare professionals has identified that specific training can help staff to understand harm reduction for substance use as well as improve attitudes toward it (Ali et al., Citation2021; Goddard, Citation2003; Hartzler et al., Citation2014). In turn, positive staff attitudes to harm reduction (including managed alcohol dispensing) can then build trust and better therapeutic relationships between staff and residents in homelessness services (Nixon & Burns, Citation2022). Staff training on why harm reduction approaches are suitable and necessary should, therefore, be considered before intervention development to increase the likelihood of workforce buy-in and implementation success (Parkes, Carver, Masterton, et al., Citation2021; Parkes, Carver, Matheson, et al., Citation2021). Particularly given the prevalence of abstinence-based approaches within Scottish services that support people with experiencing alcohol dependence, Carver, Parkes, et al. (Citation2022) found that the introduction of a MAP in Scotland would likely require a slow, ongoing approach to training before implementation. Providing staff with suitable training to increase their awareness of the evidence base and benefits of MAPs within a Scottish context should, therefore, be considered as an essential element as part of managing staff perceptions and expectations of delivering a MAP.

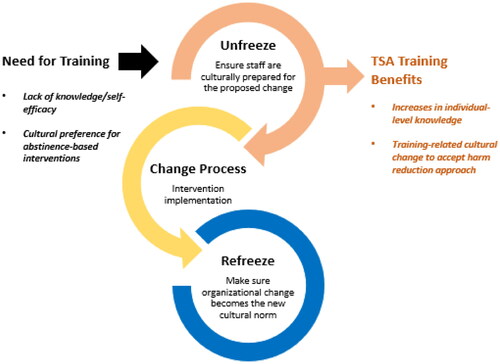

Lewin’s three stage (1. unfreezing, 2. change process, 3. refreezing) model of planned change (Lewin, Citation1947) provides a way of understanding how to plan and encourage effective change in an organization. Despite its age, Lewin’s model is considered to be one of the classic approaches used to explain organizational change within all types of organizations (Cummings et al., Citation2016; Robbins & Judge, Citation2009; Sonenshein, Citation2010). It has been used extensively to provide a theoretical perspective for managing and understanding organizational change within harm reduction settings (Sokol et al., Citation2020), and health and social care settings more widely (Abd El-Shafy et al., Citation2019; Bowers, 2011; Bradley & Mott, Citation2014; Chaboyer et al., Citation2009; Harrison et al., Citation2021; Tetef, Citation2017; Radtke, Citation2013). Lewin’s (Citation1947) model assumes that an organization may naturally exhibit some resistance to change, such as when the implementation of a novel intervention does not align with the traditional organizational culture. As a result, an organization that does not address such resistance is more likely to be unsuccessful in implementing new approaches.

Lewin’s (Citation1947) model suggests that an organization’s leaders should begin by identifying any barriers, such as training needs, and ensure that members of the organization are prepared for, and ready to accept, the proposed change. The process of preparing the organization can be targeted at the individual or group level via the sharing of knowledge where required (unfreezing). This is followed by the implementation of a novel intervention into the organization, with appropriate ongoing support and effective leadership (change process). The final stage involves the process of ensuring that the organizational change becomes the new cultural norm within the organization (refreezing) (Lewin, Citation1947). Health and social care studies have shown that organizations with higher levels of support, training, and proactive leadership are associated with more positive organizational cultures when it comes to implementing evidence-based practices to enhance quality of care (Brimhall et al., Citation2016; Hussain et al., Citation2018; Johnson et al., Citation2016; Powell et al., Citation2017). For example, The Salvation Army (TSA), an international Christian church and charity that provides support to disadvantaged people through services related to homelessness, addiction, modern slavery, poverty, older people, unemployment, and more, have acknowledged the concept of unfreezing and refreezing in their approaches. In particular, TSA services specific to homelessness and addiction in Scotland (and wider UK) discuss this concept in facilitating their harm reduction strategy over the past decade as the organization has sought to expand their support more widely than a purely abstinence-based focus (L. Ball, personal communication, August 25, 2023).

This paper reports training-specific data that were generated as part of a larger study exploring the potential implementation of MAPs in TSA services in Scotland during the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of the larger study was to understand how MAPs might reduce infection risk for people experiencing alcohol dependence and homelessness. Early in the research, TSA service managers in Scotland noticed that staff knowledge and awareness of MAPs, and alcohol harm reduction more generally, was limited. As discussed, a lack of knowledge about alcohol harm reduction is common across health and social care services, particularly within Scotland, and is not specific to TSA services. However, given the potential impact that a lack of knowledge may have on the successful implementation of novel interventions, a program of alcohol-specific staff training was designed and delivered by service managers in TSA in Scotland to respond to this.

Two training sessions were held for staff working in the four TSA services where there was the potential to implement a MAP. The first was a webinar about general alcohol harm reduction approaches that staff could use with clients, such as keeping alcohol diaries, setting realistic goals, and switching to lower (alcohol by volume, ABV) percentage alcoholic drinks. It also covered general statistics around alcohol use and alcohol-specific harms in Scotland, the link between alcohol and mental health, and the importance of self-care and emotional regulation for staff, recognizing that they were experiencing highly challenging circumstances during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although MAPs were briefly discussed in this workshop, they were not given extensive attention given that the aim was to encourage staff to start considering alcohol harm reduction without overloading them with information. The second session was a webinar that specifically focused on MAPs, discussing the rationale underpinning them and the supporting evidence base. Evidence and case studies of MAPs in Canada, drawn primarily from The Canadian Managed Alcohol Program Studies (CMAPS) web page (Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, n.d.), were used as a launching point for discussion about how MAPs could work within TSA services. The training included breakout rooms for staff to discuss fears and concerns around MAPs. With reference to Lewin’s (Citation1947) model of organizational change, this paper reports on specific qualitative data relating to this training and the impact training had on TSA staff (both individually and culturally) within a Scottish context.

Methods

A full account of the methods has already been reported (Carver, Parkes, et al. Citation2022; Parkes, Carver, Masterton, et al., Citation2021) so they are summarized here in relation to the training-specific data reported in this paper. The study was conducted over a period of six months (May–November 2020) in four TSA service settings in Scotland which were representative of the wider diversity of client and staff experiences across the country. These settings were two large ‘Lifehouses’ (hostels/shelters), a Housing First setting (permanent supportive housing), and a city center ‘drop-in.’ Data collection was facilitated by a productive research center community-university partnership between the University of Stirling and TSA which has been in place since February 2017. Ethical approval was granted by University of Stirling’s General University Ethics Panel (GUEP; paper 917) and the Ethics Subgroup of the Research Coordinating Council of The Salvation Army (RCC-EAN200709). Risk assessments were in place for face-to-face data collection.

Qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews conducted between July and October 2020 with TSA frontline staff and service managers. Participants were purposively sampled to ensure diversity regarding gender, role, and organizational roles. Service managers working in the four TSA services were invited to participate in an interview. They were also asked to identify frontline staff for the research team to approach for interview. These individuals were then provided with information about the study and invited to participate in an interview. Participants were supplied with an information sheet detailing the interview process and, before the interview, written consent was obtained.

Interview schedules for the wider study (Supplementary File 1) sought perspectives on the potential implementation of MAPs and interview questions were informed by the Consolidation Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al., Citation2009), a framework used extensively in public health research to facilitate identification of key considerations and potential barriers to interventions being implemented. The CFIR was used to structure interview questions so that the research team could explore different aspects of the intervention. Relative to this training-specific paper, the CFIR guided the structure of interview questions about the inner context of an organization, such as its structural characteristics, culture, and its readiness for implementation, and how these can affect successful intervention implementation. The CFIR therefore aligns well with Lewin’s (Citation1947) model of organizational change which was drawn on to guide the analysis of training data reported in this paper, as discussed below. Interviews were conducted by telephone by WM and PM. All interviews were audio-recorded and lasted an average of 54 min. At the conclusion of the interview, participants were given a debrief sheet and thanked for their help. After each interview, detailed fieldnotes were written up by each researcher to encourage reflexivity (Maharaj, Citation2016) and enable changes to be made to the interview schedules as needed.

After full transcription, data were uploaded in two separate participant datasets (staff and service managers) to NVivo version 12. Data for the wider study were analyzed using Framework Analysis (Ritchie & Lewis, Citation2003) which enabled a structured and transparent approach (Kiernan & Hill, Citation2018). Due to the short timeframe of the study, specified by the research funder, four researchers (HB, JD, PM, TB) took part in concurrent coding, with a fifth (HC) regularly checking for coding consistency across the coders. Researchers coded line-by-line. While the study research questions guided deductive coding activities, inductive coding was also used to explore new ideas and expand on the CFIR framework (Damschroder et al., Citation2009). HB and HC developed an initial thematic framework after the coding of six transcripts and this was then used to code the remainder. Data were then arranged into themes/subthemes and key quotes identified. To provide greater theoretical insight into the data specific to staff knowledge, training, and organizational change, Lewin’s (Citation1947) three stage model of organizational change was subsequently drawn on, and findings were analyzed in relation to the initial ‘unfreeze’ phase ().

Figure 1. Findings in relation to Lewin’s (Citation1947) three stage model of organizational change.

Findings

Fifteen interviews were conducted with seven frontline staff and eight service managers: the frontline staff worked in three of the four TSA services, three of the service managers had national roles, and five worked in frontline services. The findings were split into two key themes which highlighted the specific training benefits: increases in individual-level knowledge, and training-related cultural change.

Increases in individual-level knowledge

Findings highlighted how important staff thought it was to have training around alcohol harm reduction. Many reported knowing very little about this area, as well as having limited knowledge of the serious risks surrounding alcohol withdrawal:

Some of my colleagues weren’t even aware about the possibilities of the central nervous system shutting down and possibly having fatal circumstances if you were to withdraw. (Staff 7)

I don’t really think there is a lot out there for people that are struggling with alcohol… there seems to be a lot more services in place for people that are using drugs, so the numbers were quite shocking actually. (Staff 4)

Their centers have been understaffed, they have been under a lot of pressure, you know, just in general with COVID etc., and I think it gave them that opportunity to sit back and self-reflect. (Manager 3)

Initially they were really uncertain… this is something that we’ve never really had in our conversation before, and I think through the staff going on training, having regular conversations as a team about it, having the webinar, each step kind of opens up people’s eyes up a wee bit more… actually giving them a bit of information, letting them kind of assimilate it, mull it over, coming back with questions, and each stage, you know, you move forwards. (Manager 7)

With increasing knowledge of how MAPs operated, however, came some concerns and fears. Some participants expressed fears regarding how MAPs could fit into the existing support their service provided. For example, some staff felt that there were simply not enough resources to maintain new interventions and were concerned about the additional staff time and costs that may be implicated. Staff discussed feeling overstretched already, particularly during the pandemic, and felt that adding a MAP to an already overburdened staff team would be an additional challenge. Members of management also discussed this concern:

It’s not about ticking a box, do you know what I mean? ‘Oh we do a managed alcohol program’ but, actually, do we have that level of resource to be able to support staff on the frontline to deliver the service? (Manager 3)

I think giving the same opportunities to talk about the barriers and their individual concerns, you know, and then tackling those. So, people say ‘I am concerned about somebody being on a MAP passing away and the impact that that has on me personally, but also how it impacts on me professionally.’ Then speaking to people about the nature of the client group that we work with… ‘have you ever worked in a setting where you’ve lost a service user?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Okay, were they involved in any sort of intervention at that time?’ It’s trying to make it real to people… I think it’s a unique opportunity for people to really put their cards on the table, how they feel, and then using that to kind of move forward, and involving people in the solutions to some of those barriers. (Manager 7)

Training-related cultural change

As well as individual-level changes in knowledge, findings showed that training could contribute to cultural change within the organization. This is important in the context of this study given the popularity of abstinence-based approaches in services that support people experiencing alcohol dependence in Scotland. As noted, an abstinence-based culture would likely pose a challenge when trying to implement a harm reduction intervention. The development of the training sessions was described by managers and staff as showing that the organization is open to research and building knowledge and evidence about harm reduction interventions. Others commented that the alcohol harm reduction training shows how much the value base and approach of TSA had shifted over the past few years, while acknowledging there was still hesitation, particularly in Scotland, over how the details regarding how harm reduction might work in practice:

It’s a big movement for the organization, because this is an organization that has always espoused abstinence as the choice. The organization has really embraced harm reduction over the last six, seven years, and has moved significantly in that direction. But, all of a sudden, when you’re kind of saying, when you are bringing it [alcohol] into the building, then they have real concerns, and I can understand that. But they are open, and they are really moving themselves forward. (Manager 1)

The old me would have definitely been a barrier, the old me would have said, ‘this is not a good idea’ […], but I’ve changed as a person and I’ve changed as a professional, well, in my professional life as well. (Staff 14)

I now think we would all be capable of it. (Staff 22)

They are not just being told, you know, ‘we need to do a managed alcohol program’. They are actually being asked ‘what are your thoughts and feelings around it? And how do you think it would look?’ I think the breakout rooms were probably the most successful part of it in terms of staff really just feeling valued and heard and actually, you know, we didn’t have all the answers to all their questions, by any stretch of the imagination, but just being open and honest about this, and saying ‘we are exploring this, and lots of your questions are valid, and these are the things that we really need to be looking into, and getting some of the answers to, if this were to be rolled out’. (Manager 3)

Participants remained hopeful that, through continued training and discussions around the need for novel interventions, cultural change could be possible in the near future. Staff highlighted how ‘like with drugs, it takes time, but then you feel more confident about the advice you give out’ (Staff 20). Indeed, other interviewees stated that the training allowed them to consider how they were ‘nearly there’:

Once the basic structure is in place, I think it could be something that could run well, run smoothly for a small bunch of people, and prove itself very quickly in terms of its effectiveness. (Manager 6)

In summary, study findings highlighted that the training sessions increased individual-level knowledge around alcohol harm reduction and the need for novel interventions, such as MAPs. However, findings also highlighted that training helped initiate conversations around organizational-level cultural change regarding how MAPs could, in fact, complement existing organizational values and practice within a Scottish context. These findings demonstrate that both individual- and organizational-level change are likely to both be essential when implementing a novel harm reduction intervention, particularly in an environment where it is not immediately obvious how it will be successfully integrated. Indeed, as TSA have done previously with other harm reduction interventions relating to illicit drugs, the organization is attempting to resolve (‘unfreeze’) initial staff barriers to the successful implementation of MAPs within Scotland through the provision of staff training and promoting culture change. In turn, this should help facilitate a move toward a more adaptive implementation culture.

Discussion

This paper has presented data on the importance of training in relation to organizational change that was generated as part of a wider study regarding the potential implementation of MAPs in TSA services in Scotland during the early COVID-19 pandemic. TSA undertook training with staff within the four services involved in the research study to address a gap in their knowledge regarding MAPs and alcohol harm reduction. The findings highlight that staff knowledge in relation to MAPs and alcohol harm reduction increased following training because it provided them with opportunities to voice concerns and ask questions regarding the potential implementation of MAPs within their services. As Lewin (Citation1947) notes, organizational resistance can be directly addressed through training to facilitate staff engagement (unfreezing). The provision of training before the implementation of a novel harm reduction intervention could improve buy-in from staff and service managers, which may increase the likelihood of successful implementation in the following change process stage, as shown previously in (Lewin, Citation1947).

Additionally, the findings highlight that it is particularly important for staff to be suitably trained in relation to MAPs given that the harm reduction ethos inherent within MAPs may be at odds with their own attitudes and past experiences (Carver, Parkes, et al., Citation2022; Mancini et al., Citation2008). As previously discussed, abstinence-based approaches appear to be more common in Scotland, compared to other parts of the UK, and this may present a barrier to implementing alcohol harm reduction in Scottish services that support people experiencing alcohol dependence and homelessness. Research has shown that direct experience of an evidence-based harm reduction intervention, as well as training and explicit clinical guidance, may positively impact staff attitudes and confidence in their roles (James et al., Citation2021; VanDevanter et al., Citation2020). In turn, this may facilitate the introduction of alcohol harm reduction, even in a service that has not integrated it before. Thus, training followed by timely implementation of MAPs could strengthen the ‘unfreezing’ process and facilitate the journey toward ‘refreezing’ the organizational norms around alcohol harm reduction interventions, with important implications for future service delivery in a Scottish context. It should be noted, however, that training was only provided to staff on two occasions, so additional training would likely be required if TSA choose to move forward with the implementation of MAPs within their services in Scotland. Findings indicate that training should also be ongoing throughout service delivery to ensure benefits, something with wider applicability to services across the sector.

Study findings also indicated that training could contribute to wider cultural changes within an organization, such as moving from a traditionally abstinence-based approach in relation to alcohol, to a harm reduction approach. Indeed, the training process as a whole highlighted TSA’s desire to provide such services in Scotland and to ensure that staff were well-trained, knowledgeable, and confident enough to do so. Hussain et al. (Citation2018) explain that organizations do not rely solely on training individuals for cultural change, but also on individuals sharing their knowledge at the wider organizational level. Therefore, through individuals sharing their knowledge of beliefs, experiences, skills, competencies, and abilities with colleagues, including management, this can be effective in challenging the status quo and result in both proactive and reactive organizational cultural change (Hussain et al., Citation2018). It is therefore possible that increasing individual staff knowledge could be an effective catalyst for wider organizational change that can operate to reinforce a positive implementation culture, not only from the top down but from the bottom up. As discussed, TSA reports the successful freezing and unfreezing process for various interventions over the past decade and highlights the importance of understanding it as an ongoing process, particularly when there is a high level of staff turnover with newer, less experienced staff coming in which, in turn, may inhibit knowledge transfer (L. Ball, personal communication, August 25, 2023).

Lewin’s (Citation1947) model emphasizes the importance of effective leaders in creating a successful process of change. Our findings highlight that staff had opportunities to be included in ‘strategic level discussions’ about MAPs. This seems to have transcended the impact of the training beyond unfreezing, as employee involvement has been cited as an important aspect of the subsequent change process stage when the novel intervention is implemented (Hussain et al., Citation2018). Staff involvement in strategic discussions thereby represents an early way of giving staff some ownership of the potential implementation of a new intervention which could further enhance the cultural shift toward accepting a MAP. Going forward, however, TSA may need to establish ongoing staff and other stakeholder groups at the strategic and planning level for the implementation of MAPs in Scotland.

This paper provides insight into the views and experiences of staff and service managers regarding training provision as part of a research study of the potential implementation of MAPs. We highlight the changes made to individual-level knowledge, as well as to organizational culture change. The study has some limitations. Firstly, we were only able to interview seven frontline staff from three of the four services. We approached more staff to participate but, due to staff sickness and severe challenges with staffing resources and capacity due to COVID-19, we were unable to speak to more. Secondly, the interviews with staff were conducted at the same time as the training was being provided which meant we were unable to capture participant views before and after the training which would have been advantageous. While some participants had not yet completed the training when they were interviewed, others had, so this provided different perspectives on training needs. This is not necessarily a limitation but should be noted. Finally, it is possible that the participants interviewed were more knowledgeable (than wider staff members) about and supportive of, MAPs. This was certainly the case for service managers who had strongly bought into the intervention and its usefulness for TSA clients. This may be a reason why the voices of managers seemed to come through more strongly than staff in relation to training. It is also likely that the frontline staff we interviewed were aware of MAPs and their benefits, although findings still showed levels of resistance and fear among the participant group. In terms of implications for future research, there should be further exploration of the views of those who have not yet bought into or are less aware of, MAPs as an intervention and wider alcohol harm reduction approaches. Additionally, more research is required to better understand the longer-term impact of training on staff before and during MAP implementation.

Conclusion

In this paper, we describe frontline staff and service managers’ views and experiences of training on alcohol harm reduction and MAPs which was conducted to improve staff knowledge and awareness. We drew on Lewin’s (Citation1947) model of organizational change to interpret the training-specific data within the wider study, highlighting the benefits of training provision in increasing knowledge and facilitating wider cultural change as part of the ‘unfreezing’ process. The findings have implications for future implementation of MAPs in homelessness settings, highlighting the need for training to support positive staff buy-in, involvement of staff within the planning process, and changing organizational cultures from abstinence-based to an environment where novel harm reduction approaches can be embraced.

Institutional Review Board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the General University Ethics Panel of University of Stirling (paper 917; 30 June 2020) and the Ethics Subgroup of the Research Coordinating Council of The Salvation Army (RCC-EAN200709; 6 July 2020).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, T.P., H.C., B.M.P., and L.B.; methodology, T.P., H.C., and B.M.P.; coding, H.B., P.M., and H.C.; analysis, W.M., H.C., and H.B; resources, L.B. and H.M.; writing—original draft preparation, W.M., H.C., H.B., P.M., and T.P.; writing—review and editing W.M., H.C., H.B., P.M., T.P., L.B., H.M., L.M., and B.M.P.; supervision, T.P., H.C., L.B., and H.M.; project administration, T.P., H.C., and W.M.; funding acquisition; T.P., H.C., and B.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank The Salvation Army for their support for this study, including all of the Study Strategy Group: Margaret Cowan, Susan Grant, Fi Grimmond, Sean Kehoe, Laura Mitchell, and Iain Wilson. We would also like to thank our participants for their willingness to be involved and their valuable insights; Catriona Matheson who helped with the funding application; and our Research Advisory Group who provided insight and expertise throughout the study. We would also like to acknowledge Danilo Falzon, Josh Dumbrell, Tyler Browne, and other SACASR colleagues for their help with data collection and analysis and note taking during SG meetings. Finally, we would like to thank the University of Stirling’s General University Ethics Panel (GUEP) and the Ethics Subgroup of the Research Coordinating Council of The Salvation Army for turning around our ethics applications so quickly during an extremely challenging time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the study are not publicly available. Individual privacy could be compromised if the dataset is shared due to the small sample involved.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abd El-Shafy, I., Zapke, J., Sargeant, D., Prince, J.M., & Christopherson, N. A. M. (2019). Decreased pediatric trauma length of stay and improved disposition with implementation of Lewin’s change model. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 26(2), 84–88.

- Ali, S., McCormick, K., & Chavez, S. (2021). LEARN harm reduction: A collaborative organizational intervention in the US South. Journal of Social Service Research, 47(4), 590–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2020.1860183

- Bradley, S., & Mott, S. (2014). Adopting a patient-centred approach: An investigation into the introduction of bedside handover to three rural hospitals. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(13–14):1927–1936.

- Brimhall, K. C., Fenwick, K., Farahnak, L. R., Hurlburt, M. S., Roesch, S. C., & Aarons, G. A. (2016). Leadership, organizational climate, and perceived burden of evidence-based practice in mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 43(5), 629–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0670-9

- Brocious, H., Trawver, K., & Demientieff, L. V. X. (2021). Managed alcohol: One community’s innovative response to risk management during COVID-19. Harm Reduction Journal, 18(125). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00574-5

- Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research (2022). Overview of managed alcohol program (MAP) sites in Canada (and beyond). Retrieved from https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/assets/docs/resource-overview-of-MAP-sites-in-Canada.pdf

- Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research (n.d.). The Canadian Managed Alcohol Program Studies (CMAPS). Retrieved from https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/projects/map/index.php

- Carver, H., Parkes, T., Browne, T., Matheson, C., & Pauly, B. (2021). Investigating the need for alcohol harm reduction and managed alcohol programmes for people experiencing homelessness and alcohol use disorders in Scotland. Drug and Alcohol Review, 40(2), 220–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13178

- Carver, H., Parkes, T., Masterton, W., Booth, H., Ball, L., Murdoch, H., Falzon, D., & Pauly, B. M. (2022). The potential for managed alcohol programmes in Scotland during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A qualitative exploration of key areas for implementation using the consolidated framework for implementation research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15207. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215207

- Carver, H., Price, T., Falzon, D., McCulloch, P., & Parkes, T. (2022). Stress and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods exploration of frontline homelessness services staff experiences in Scotland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063659

- Carver, H., Ring, N., Miler, J., & Parkes, T. (2020). What constitutes effective problematic substance use treatment from the perspective of people who are homeless? A systematic review and meta-ethnography. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-0356-9

- Chaboyer, W., McMurray, A., Johnson, J., Hardy, L., Wallis, M., & Sylvia Chu, F,Y. (2009). Bedside handover: Quality improvement strategy to “transform care at the bedside”. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 24(2), 136–142.

- Cummings, S., Bridgman, T., & Brown, K, G. (2016). Unfreezing change as three steps: Rethinking Kurt Lewin’s legacy for change management. Human Relations, 69(1), 33–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715577707

- Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- Depaul (2023a). Stella Maris. Retrieved from https://ie.depaulcharity.org/projects/stella-maris/

- Depaul (2023b). Sundial House. Retrieved from https://ie.depaulcharity.org/projects/sundial-house/

- Ezard, N., Cecilio, M. E., Clifford, B., Baldry, E., Burns, L., Day, C. A., Shanahan, M., & Dolan, K. (2018). A managed alcohol program in Sydney, Australia: Acceptability, cost-savings and non-beverage alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37 Suppl 1(S1), S184–S194. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12702

- Fuertes, R., Belo, E., Merendeiro, C., Curado, A., Gautier, D., Neto, A., & Taylor, H. (2021). Lisbon’s COVID 19 response: harm reduction interventions for people who use alcohol and other drugs in emergency shelters. Harm Reduction Journal, 18(13). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00463-x

- Gaetz, S., Dej, E., Richter, T., & Redman, M. (2016). The state of homelessness in Canada 2016. Canadian Observatory on Homelessness. Retrieved from https://homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/SOHC16_final_20Oct2016.pdf

- Goddard, P. (2003). Changing attitudes towards harm reduction among treatment professionals: A report from the American Midwest. International Journal of Drug Policy, 14(3), 257–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-3959(03)00075-6

- Hartzler, B., Jackson, T. R., Jones, B. E., Beadnell, B., & Calsyn, D. A. (2014). Disseminating contingency management: Impacts of staff training and implementation at an opiate treatment program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(4), 429–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.12.007

- Harrison, R., Fischer, S., Walpola, R, L., Chauhan, A., Babalola, T., Mears, S., & Le-Dao, H. (2021). Where do models for change management, improvement and implementation meet? A systematic review of the applications of change management models in healthcare. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 13, 85–108. https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S289176.

- Harvey, L., Sliwinski, S. K., Flike, K., Boudreau, J., Gifford, A. L., Branch-Elliman, W., & Hyde, J. (2022). Utilizing implementation science to identify barriers and facilitators to implementing harm reduction services in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 9(Supplement_2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofac492.1715

- Holmes, C. (2019). Consultation findings on the development of a residential managed alcohol program for trial and evaluation in the Northern Territory. Final report.

- Hussain, S. T., Lei, S., Akram, T., Haider, M. J., Hussain, S. H., & Ali, M. (2018). Kurt Lewin’s change model: A critical review of the role of leadership and employee involvement in organizational change. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 3(3), 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2016.07.002

- Ivsins, A., Pauly, B., Brown, M., Evans, J., Gray, E., Schiff, R., Krysowaty, B., Vallance, K., & Stockwell, T. (2019). On the outside looking in: Finding a place for managed alcohol programs in the harm reduction movement. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 67, 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.02.004

- James, J. R., Marolf, M., Klein, J. W., Blalock, K. L., Merrill, J. O., & Tsui, J. I. (2021). Staff attitudes toward buprenorphine before and after implementation of an office-based opioid treatment program in an urban teaching clinic. Substance Use & Misuse, 56(11), 1569–1575. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2021.1928206

- Johnson, A., Nguyen, H., Groth, M., Wang, K., & Ng, J. L. (2016). Time to change: a review of organisational culture change in health care organisations. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 3(3), 265–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-06-2016-0040

- Johnson, G., & Chamberlain, C. (2008). Homelessness and substance abuse: Which comes first? Australian Social Work, 61(4), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070802428191

- Kiernan, M. D., & Hill, M. (2018). Framework analysis: A whole paradigm approach. Qualitative Research Journal, 18(3), 248–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-D-17-00008

- Kouimtsidis, C., Pauly, B., Parkes, T., Stockwell, T., & Baldacchino, A. M. (2021). COVID-19 social restrictions: An opportunity to re-visit the concept of harm reduction in the treatment of alcohol dependence. A position paper. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 623649. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.623649

- Lewin, K. (1947). Field theory in social science. Harper & Row.

- Maharaj, N. (2016). Using field notes to facilitate critical reflection. Reflective Practice, 17(2), 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2015.1134472

- Mancini, M. A., Linhorst, D. M., Broderick, F., & Bayliff, S. (2008). Challenges to implementing the harm reduction approach. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 8(3), 380–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332560802224576

- McVicar, D., Moschion, J., & van Ours, J. C. (2015). From substance use to homelessness or vice versa? Social Science & Medicine, 136–137, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.005

- Meyerson, B. E., Agley, J. D., Jayawardene, W., Eldridge, L. A., Arora, P., Smith, C., Vadiei, N., Kennedy, A., & Moehling, T. (2020). Feasibility and acceptability of a proposed pharmacy-based harm reduction intervention to reduce opioid overdose, HIV and hepatitis C. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy, 16(5), 699–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.08.026

- Mutschler, C., Bellamy, C., Davidson, L., Lichtenstein, S., & Kidd, S. (2022). Implementation of peer support in mental health services: A systematic review of the literature. Psychological Services, 19(2), 360–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000531

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2011). Alcohol-use disorders. Diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking and alcohol dependence. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg115/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-136423405

- National Records of Scotland (2023). Alcohol-specific deaths 2022. National Records of Scotland. Retrieved from https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/vital-events/deaths/alcohol-deaths

- Nixon, L. L., & Burns, V. F. (2022). Exploring harm reduction in supportive housing for formerly homeless older adults. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 25(3), 285–294. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.25.551

- Parkes, T., Carver, H., Masterton, W., Booth, H., Ball, L., Murdoch, H., Falzon, D., Pauly, B. M., & Matheson, C. (2021). Exploring the potential of implementing managed alcohol programmes to reduce risk of COVID-19 infection and transmission, and wider harms, for people experiencing alcohol dependency and homelessness in Scotland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12523. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312523

- Parkes, T., Carver, H., Matheson, C., Browne, T., & Pauly, B. (2021). ‘It’s like a safety haven’: Considerations for the implementation of managed alcohol programs in Scotland. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 29(5), 477–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2021.1945536

- Pauly, B., Brown, M., Chow, C., Wettlaufer, A., Graham, B., Urbanoski, K., Callaghan, R., Rose, C., Jordan, M., Stockwell, T., Thomas, G., & Sutherland, C. (2021). “If I knew I could get that every hour instead of alcohol, I would take the cannabis”: Need and feasibility of cannabis substitution implementation in Canadian managed alcohol programs. Harm Reduction Journal, 18(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00512-5

- Pauly, B., Brown, M., Evans, J., Gray, E., Schiff, R., Ivsins, A., Krysowaty, B., Vallance, K., & Stockwell, T. (2019). “There is a place”: Impacts of managed alcohol programs for people experiencing severe alcohol dependence and homelessness. Harm Reduction Journal, 16(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-019-0332-4

- Pauly, B., Vallance, K., Wettlaufer, A., Chow, C., Brown, R., Evans, J., Gray, E., Krysowaty, B., Ivsins, A., Schiff, R., & Stockwell, T. (2018). Community managed alcohol programs in Canada: Overview of key dimensions and implementation. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37 Suppl 1(S1), S132–S139. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12681

- Pauly, B., Wallace, B., & Barber, K. (2018). Turning a blind eye: Implementation of harm reduction in a transitional programme setting. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 25(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2017.1337081

- Podymow, T., Turnbull, J., Coyle, D., Yetisir, E., & Wells, G. (2006). Shelter-based managed alcohol administration to chronicallyhomeless people addicted to alcohol. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174(1), 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1041350

- Powell, B. J., Beidas, R. S., Lewis, C. C., Aarons, G. A., McMillen, J. C., Proctor, E. K., Khinduka, S. K., & Mandell, D. S. (2017). Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 44(2), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-015-9475-6

- Radtke, K. (2013). Improving patient satisfaction with nursing communication using bedside shift report. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 27(1),19–25.

- Ristau, J., Mehtani, N., Gomez, S., Nance, M., Keller, D., Surlyn, C., Eveland, J., & Smith-Bernardin, S. (2021). Successful implementation of managed alcohol programs in the San Francisco Bay Area during the COVID-19 crisis. Substance Abuse, 42(2), 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2021.1892012

- Ritchie, J., & Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Robbins, S., & Judge, T. A. (2009). Organizational behavior: Concepts, controversies, and applications. 13th edn. Prentice-Hall.

- Scottish Housing News (2020). Managed alcohol project to be piloted in Scotland. Retrieved from https://www.scottishhousingnews.com/article/managed-alcohol-project-to-be-piloted-in-scotland#:∼:text=The Managed Alcohol Project aims,of coming off alcohol altogether

- Smith-Bernardin, S. M., Suen, L. W., Barr-Walker, J., Cuervo, I. A., & Handley, M. A. (2022). Scoping review of managed alcohol programs. Harm Reduction Journal, 19(82). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-022-00646-0

- Sonenshein, S. (2010). We’re changing – or are we? Untangling the role of progressive, regressive, and stability narratives during strategic change implementation. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 477–512.

- Sokol, R., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Batalden, M., Sullivan, L., & Shaughnessy, A, F. (2020). A change management case study for safe opioid prescribing and opioid use disorder treatment. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 33(1), 129–137.

- Stockwell, T., Pauly, B. B., Chow, C., Erickson, R. A., Krysowaty, B., Roemer, A., Vallance, K., Wettlaufer, A., & Zhao, J. (2018). Does managing the consumption of people with severe alcohol dependence reduce harm? A comparison of participants in six Canadian managed alcohol programs with locally recruited controls. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37 Suppl 1(S1), S159–S166. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12618

- Stockwell, T., Pauly, B., Chow, C., Vallance, K., & Perkin, K. (2013). Evaluation of a managed alcohol program in Vancouver, BC: Early findings and reflections on alcohol harm reduction (Vol. 9). University of Victoria Centre for Addictions Research of BC (CARBC) Bulletin.

- Tetef, S. (2017). Successful implementation of new technology using an interdepartmental collaborative approach. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing, 32(3), 225–230.

- Vallance, K., Stockwell, T., Pauly, B., Chow, C., Gray, E., Krysowaty, B., Perkin, K., & Zhao, J. (2016). Do managed alcohol programs change patterns of alcohol consumption and reduce related harm? A pilot study. Harm Reduction Journal, 13(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-016-0103-4

- VanDevanter, N., Vu, M., Nguyen, A., Nguyen, T., van Minh, H., Nguyen, N. T., & Shelley, D. R. (2020). A qualitative assessment of factors influencing implementation and sustainability of evidence-based tobacco use treatment in Vietnam health centers. Implementation Science, 15(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01035-6

- Waugh, A., Clarke, A., Knowles, J., & Rowley, D. (2018). Health and homelessness in Scotland. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/health-homelessness-scotland/

- Zhao, J., Stockwell, T., Pauly, B., Wettlaufer, A., & Chow, C. (2022). Participation in Canadian managed alcohol programs and associated probabilities of emergency room presentation, hospitalization and death: a retrospective cohort study. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 57(2), 246–260.