Abstract

Prior to the conflict, Syria had relatively high fertility rates. In 2010, it had the sixth highest total fertility rate in the Arab World, but it witnessed a fertility decline before the conflict in 2011. Displacement during conflict influences fertility behaviour, and meeting the contraceptive needs of displaced populations is complex. This study explored the perspectives of women and service providers about fertility behaviour of and service provision to Syrian refugee women in Bekaa, Lebanon. We used qualitative methodology to conduct 12 focus group discussions with Syrian refugee women grouped in different age categories and 13 in-depth interviews with care providers from the same region. Our findings indicate that the displacement of Syrians to Lebanon had implications on the fertility behaviour of the participants. Women brought their beliefs about preferred family size and norms about decision-making into an environment where they were exposed to both aid and hardship. The unaffordability of contraceptives in the Lebanese privatised health system compared to their free provision in Syria limited access to family planning services. Efforts are needed to maintain health resources and monitor health needs of the refugee population in order to improve access and use of services.

Résumé:

Avant le conflit, la Syrie affichait des taux de fécondité relativement élevés. En 2010, elle présentait le sixième taux de fécondité total le plus élevé dans le monde arabe, mais a été témoin d'un déclin de fécondité avant le conflit en 2011. Le déplacement au cours du conflit affecte le comportement de la fécondité et la satisfaction des besoins contraceptifs des populations déplacées est complexe. Cette étude a exploré les perspectives des femmes et des fournisseurs de services sur le comportement de la fécondité et la prestation de services aux femmes réfugiées syriennes à la Bekaa, au Liban. Nous avons utilisé une méthodologie qualitative pour mener 12 discussions avec des femmes réfugiées syriennes regroupées dans différentes catégories d'âge et 13 entretiens approfondis avec des fournisseurs de soins de la même région. Nos résultats ont indiqué que le déplacement des Syriens vers le Liban a des implications sur le comportement de fertilité des participants. Les femmes ont apporté leurs croyances sur la taille de la famille préférée et les normes sur la prise de décision dans un environnement où elles étaient exposées à la fois à l'aide et aux difficultés. L'inabordabilité des moyens de contraception dans le système de santé privatisé libanais comparativement à leur offre gratuite en Syrie a limité l'accès aux services de planification familiale. Des efforts sont nécessaires pour maintenir les ressources sanitaires et surveiller les besoins en matière de santé de la population réfugiée afin d'améliorer l'accès et l'utilisation des services.

موجز اامقال

قبل النزاع، كانت معدلات الخصوبة مرتفعة نسبيًا في سوريا. ففي العام 2010، سجلت سوريا سادس أعلى معدل للخصوبة الكلي في العالم العربي، ولكنها شهدت انخفاضًا في معدّل الخصوبة قبل النزاع في العام 2011. هذا وقد أثّر النزوح خلال النزاع على سلوك الخصوبة في حين أن تلبية احتياجات النازحين من وسائل منع الحمل أمر معقد. قامت هذه الدراسة بإستكشاف وجهات نظر النساء ومقدمي الخدمات بشأن سلوك الخصوبة وتوفير الخدمات للاجئات السوريات في البقاع، لبنان. واعتمدنا منهجية نوعية لإجراء 12 جلسة مناقشة مركزة مع اللاجئات السوريات ضمن فئات عمرية مختلفة و13 مقابلة معمقة مع مقدمي الرعاية في المنطقة نفسها. وأشارت نتائجنا إلى أن حركة نزوح السوريين إلى لبنان لها انعكاسات على سلوك الخصوبة لدى المشاركات في الدراسة. وأعربت النساء عن آرائهن حول حجم الأسرة المفضل لديهن والمعايير في صنع القرار في بيئة تعرضن فيها لكل من المساعدة والمشقة. هذا وقد حدّت عدم القدرة على تحمل تكاليف وسائل منع الحمل في النظام الصحي اللبناني المخصخص مقارنة بتوزيعها المجاني في سوريا، من إمكانية الحصول على خدمات تنظيم الأسرة. وينبغي بذل جهود للحفاظ على الموارد الصحية ورصد الاحتياجات الصحية للاجئين من أجل تحسين إمكانية الحصول على الخدمات واستخدامها

Introduction

The current conflict in Syria is described by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as “the worst humanitarian crisis in the 21st century”, resulting in 4.3 million refugees displaced to neighbouring countries and 7.6 million displaced internally by December 2015.Citation1 Over one million refugees have been displaced to Lebanon, where they live within local communities in makeshift housing, informal tented settlements (ITS) or rented spaces. According to UNHCR, the majority of Syrian refugees to Lebanon are residing in the Bekaa, an agricultural area of Lebanon most adjacent to Syria.Citation1

Interpretations of changes in fertility behaviour following forced displacement vary in the literature from rises in fertility in order to replace dead and lost children to fertility falls as a result of uncertainties of refugee life. McGinnCitation2 describes the different responses in fertility behaviour among refugees from several conflict-affected areas around the world. Low fertility was attributed to inadequate nutrition among Khmer refugees in Cambodia;Citation3 high fertility associated with the desire to procreate following massacres in Ethiopia;Citation2 whereas socio-demographic characteristics and land ownership in the host country were important factors in determining fertility levels among refugees in Belize.Citation4 In addition, the refugee population’s knowledge and use of contraception prior to the conflict are believed to influence their demand for contraceptive services, and factors related to camp organisation and access to health services in the host country influence refugees’ fertility practices.Citation2 A systematic review of refugee women’s reproductive health (RH) suggests that migration, women’s health, bio-psycho-social factors and infant health could potentially influence fertility behaviour.Citation5 Overall, fertility behaviour in the context of forced migration is complex, contextual and influenced by a number of factors that act and interact at varying degrees, therefore difficult to predict in the long term.Citation6

RH needs of refugees are complex and not always met due to financial and logistic reasons.Citation7 Limited access to RH services, including contraception, is one of the top five concerns of refugee women, increasing women’s risks of unwanted pregnancy, maternal and perinatal mortality.Citation8

The Minimum Initial Service Package for Reproductive Health (RH) (MISP) developed by the Inter-agency Working Group on RH in Crises, addresses RH needs at the onset of an emergency including provision of contraception.Citation9 However, the use of family planning services in displaced and refugee populations has been observed to be minimal and largely dependent on the suitability of those services to the cultural norms of the displaced population, contextual factors and supply of contraceptives, which has been found to be unreliable.Citation9,Citation10 Contraceptive use is generally lower in refugee camp settings compared to the non-refugee communities in the same neighbourhood due to misconceptions, fear of side effects and religious teachings.Citation11 Low use of family planning services was also coupled with poor knowledge of contraceptive methods even when demand for contraceptives was high.Citation12 The commonly faced difficulties of health service provision to refugee populations are aggravated by the long-term nature of the conflict as humanitarian agencies are ill-prepared to address these populations’ long-term needs.

The total fertility rate (TFR) declined in Syria from a very high level of 5.3 in 1990 to 2.9 in 2010 before the conflict.Citation13 Still in 2010, Syria had the sixth highest TFR in the Arab WorldCitation13 and a much higher rate (a little less than double) as compared to the TFR of 1.6 in Lebanon in that year.Citation14 There were also 5.1% polygamous marriages in 2002 in Syria.Citation15 Findings from national surveys in Syria before the conflict indicated the high use of contraceptive methods. In 2006, 73% of ever-married Syrian women reported using contraceptive methods at least once during their lifetime, while also desiring large families (4.9 children on average), reflecting contraceptive use for birth spacing.Citation16 In 2009, 54% of married women reported currently using contraceptives; 59% in urban and 47% in rural areas.Citation17 Twenty-two percent used intrauterine devices (IUD), 8.9% pills, 8.9% used periodic abstinence and 3.5% used injectables.Citation17 In a survey of 425 Syrian refugee women in Lebanon,Citation18 only 34.5% of women reported using a contraceptive method, primarily IUD followed by oral contraceptive pills and periodic abstinence. Identified barriers to contraceptive use were cost, transportation to service provision points and unavailability of services.Citation18

Syrians in Lebanon are not officially recognised as refugees by the Lebanese government therefore official camps were not established as in neighbouring countries. Many Syrians in the Bekaa live in unfinished buildings or in one of over 900 ITSs. The ITS offer little protection against weather conditions, have limited access to clean water and are often over-crowded.Citation19 ITS are managed by local governments in collaboration with UNHCR and local and international NGOs.Citation20 Refugees living outside the ITS also struggle with high rental rates and daily expenses despite being considered from economically self-sufficient groups, educated and arriving from urban areas in Syria. Syrian’s access to labour market was restricted in 2014 limiting their earning power to provide for basic needs. Seventy per cent of the displaced Syrian refugees in Lebanon now live below the Lebanese extreme poverty line.Citation21 Additionally, tensions were reported between Syrian Refugees and Lebanese nationals as both compete for the same resources and services.Citation22

RH services are provided to UNHCR registered refugees at primary health care centres. Refugees have to pay 3000–5000 LBP (2–3 USD) for a consultation and UNHCR covers up to 85% of diagnostic tests for pregnant women and 75% of the total cost of delivery.Citation23 It also provides free contraception (IUD, pills and condoms) and two postnatal visits. Unregistered refugees have access to some services, such as immunisation, newborn care and first antenatal care visit, and care for child and maternal acute illnesses and communicable diseases.Citation24

Observations of high fertility rates among Syrian refugees are commonly expressed by clinicians providing RH services in host communities in Lebanon, something that has prompted our quest for an in-depth understanding of this phenomenon and for exploring the complexities related to fertility behaviour in this context. This study explores the perspectives of women and service providers on fertility behaviour and service utilisation of refugee Syrian women in Al-Marj town in West Bekaa, Lebanon. It aims at contributing to better understanding of fertility behaviour during conflict and displacement situations and of issues around service use and provision, especially in the case of Syrian refugee population in Lebanon and elsewhere.

Methods

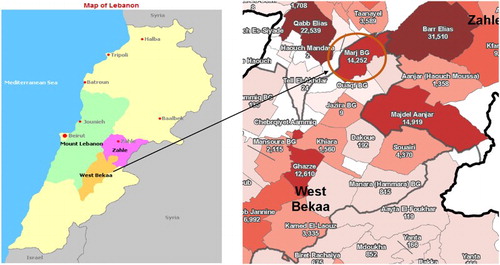

This is an exploratory study using qualitative methodology. Our study populations consisted of: (1) Syrian married women, 18 years and above, refugees in Al-Marj town of the West Bekaa region in Lebanon, and (2) health care providers from the same region. We have selected the Bekaa region, identified by UNHCR as a region hosting one of the most socio-economically vulnerable refugee communities while having 11% of the poorest Lebanese population ()Citation1. We also had ease of access to the refugee population in Al-Marj town of West Bekaa as one of the authors (FK), being from Al-Marj town, is very well connected with the local authorities and refugee groups, and two other authors (TKK and RM) have previous research experiences with the same population. According to the Municipality of Al-Marj, the displaced Syrian population in Al-Marj was estimated at 12,000 at the time of data collection (January–March 2015).

Figure 1. Map of Lebanon showing the West Bekaa region and the Al-Marj town in West Bekaa. Source: UNHCR, September 2016.

We chose to conduct focus group discussions (FGD) with Syrian refugee women as an approach recommended for investigating complex behaviourCitation25 and considering their vulnerable status and their reluctance towards individual interviews. Our initial contact was through the municipality of Al-Marj which identified community gatekeepers to assist the study team in identifying potential participants. One of the authors (RM), a post-doctoral research fellow, with appropriate training and previous experience in qualitative research, conducted 12 FGDs with women residing inside and outside ITS. Each FGD consisted of 6–12 married women. Purposive selection of women was done according to their ages and their residence (in or outside ITS) with the aim of having some homogeneity within the groups and capturing the generational variation in fertility behaviour between groups. Three age groups were included: less than 25 years, 26–35 years and 36 years old and above. The number of FGDs was guided by the principle of data saturation.Citation24 The FGDs took place within the ITS, at health centres, and at the residence of the head of the municipality. The topic guide for FGDs included the following: preferences for number of children, use of contraception, decision-making process regarding the number of children before and after conflict and displacement, and experiences with health services. The facilitator encouraged women to voice their views on these topics as well as on other relevant aspects of concern to them. Dynamic group interaction was encouraged throughout the discussions. The interviewer’s background as a Syrian female who had a good understanding of the Syrian culture and speaking to the women in Arabic, facilitated her interaction with the FGD participants and encouraged them to open up. Her status as a female Syrian professional working in Lebanon facilitated the sharing of information on contraceptive use.

A purposive sample of 13 health care providers comprising of physicians, nurses and midwives was selected for in-depth interviews. Gatekeepers identified these providers as the ones who were highly involved in providing RH services to Syrian refugees in Al-Marj. They were selected from public health centres, hospitals and private clinics, representing all types of health services accessed by Syrian refugees in that area. One of the authors (RM) approached those providers in person, obtained informed consent and conducted the interviews. The individual interviews covered providers’ experiences with Syrian refugees, their perceptions of the fertility practices of refugees and provision of family planning services to refugees.

All interviews were voice recorded and transcribed verbatim in Arabic. Thematic analysis was conducted for women’s FGDs and the providers’ interviews separately following Braun and Clarke’s approach.Citation25 Two of the authors (TKK, RM) engaged in multiple readings of the transcripts as a first step, then independently coded by identifying emerging and anticipated codes and concepts. This was done through careful line-by-line readings of the transcripts. Following that, these two authors discussed the emergent themes, which consisted of clusters of emerging meanings and shared it with the other authors in a general discussion that shaped the final interpretation of results. There were no major disagreements in relation to the identified themes between authors. Matrices were constructed to help in identifying linkages across different themes and different interviews. Two of the authors (HB and FK), familiar with the Syrian community and the refugee situation, validated the final output of themes and subthemes. Outputs from both components (FGDs, and in-depth interviews) were merged at the writing up stage. The quotes selected from the matrices to be used in the manuscript were translated to English.

Strict adherence to ethical standards in carrying research on humans was respected. The approvals of the Institutional Review Board of the American University of Beirut and key local community representatives were obtained. Informed consent was also obtained from all participants. We respected the confidentiality of respondents by not mentioning real names. We removed all identifiers during transcription. Participants in the FGDs were referred to according to the age group and area of residence (inside or outside ITS), and participants in key informant interviews were referred to according to the type of health facility where they worked.

Results

Our thematic analysis revealed the following themes presented hereafter separately for women and health care providers: desired family size for women; decision-making about fertility during displacement; perceptions about contraceptive needs and provision; perspectives of women about health care; then perspectives of health care providers of Syrian women.

Characteristics of participants

The total number of women participating in the 12 FGDs was 84. All participants whether living in or outside the ITS reported living with their extended families in the same dwellings. The families living outside of the ITS were perceived to possess some additional economic resources that enable them to pay for rent. Other characteristics describing participants are found in .

Table 1. Characteristics of FGD participants.

A total of six obstetrician/gynaecologists were interviewed, of which two were females. Two practiced in private clinics and four in public health centres. All of the five nurses interviewed were females and working in health centres, and the two midwives, also females, were providing services at a hospital ().

Table 2. Characteristics of health care providers interviewed.

Women’s desired family size

Syrian refugee women expressed a desire for four to six children in their families as it was an acceptable social norm before the conflict. The number of children is also determined by the importance attached to having at least one male born in the family, something that is perceived to guarantee the continuation of the family name, provision of support to the parents during their old age, as well as to female siblings.

“Let’s assume I got older, I have to make sure to have male children before getting old. The girls will get married and leave, I need to have at least one or two boys so that they support me when I get older … they also can help the girls (their sisters).” (18–25 yr, from ITS)

Women’s wish to establish a certain balance in gender among siblings and enhancing family support was a factor considered in determining desired family size, as expressed by one FGD participant living outside of ITS “a brother for my boy and a sister for my girl.” Similarly, “God’s will” had a prominent influence on women’s desire for family size, particularly for 36–45-year olds and those with low education level. They perceived that “God’s will” determines their number of children and “rizqa” [good livelihood] will accompany each newborn despite their current difficult circumstances.

Syrian women explained the important role that registration in the UNHCR system had in “encouraging women to get pregnant” and give birth while being displaced in Lebanon. Registration within the UN system was especially important as it entitled women’s families to receive aid for food and shelter in addition to antenatal and intra-partum care.

“The UNHCR is encouraging them to get pregnant. If you don’t have a baby, and even when you have children, you’re not entitled for aid, so women get pregnant to receive aid.” (26–35 yr, outside ITS)

There was also a perceived need to replace the children lost to war.

“We want to have more children because we lost many … . I lost my 8 year old son. Everyone has lost one or two people from the family. If the situation allows, everyone will want to have more children.” (36–45 yr, outside ITS)

These preferences and needs, however, were found to be in conflict with difficulties imposed on these families because of displacement. A change towards lower fertility was particularly revealed for women in the 18–25 age group with some wanting to limit their family to one or two children.

“One boy and one girl is more than enough in this situation, the less the better, I mean life is difficult, everything is expensive, you need to be able to provide for both children and save money.” (18–25 yr, outside ITS)

The group dynamics in FGDs encouraged women to draw comparisons between living conditions before and after the conflict noting their reduced desire for children “as refugees, we forgot the idea of having children”. Women voiced concerns about the difficulty of providing basic needs of food and shelter, as men, if present, were usually unemployed and obliged to support the extended family residing with them.

“… you have to pay for rent, electricity, water, and if the water is cut off, you need to buy it, everything changed, my husband needs to support everyone living with us here.” (18–25 yrs, outside ITS)

Women also considered the lack of equal opportunities for Syrian children in terms of schooling and legal registration for those born in Lebanon when deciding to limit their family size. A woman living in an ITS shared her story:

“… .my daughter was registered on my father- in-law’s family document because our marriage was not officially registered at the court. This means that she is the sister of my husband (sigh) … .we wanted to have a child each year, not anymore.”

“We have a big problem. I have 3 children and there is no school and I cannot afford to send them to a private school. I teach them letters and how to count at home.” (18–25 yr, ITS)

Decision-making about fertility during displacement

Women were fearful that their husbands would marry a second wife, as polygamy is culturally accepted in certain rural areas of Syria, especially when the couple does not have male children. Polygamy has become a more significant threat to women after displacement to Lebanon, in view of wider exposure of men to women outside their communities and the living arrangements imposed by displacement whereby more interactions between men and women are experienced in contrast to the traditional norms that limited these interactions in Syria. This comes in addition to the tendency of displaced Syrian families to want to marry their single daughters earlier than they are used to in Syria, in an effort to ensure their social security.

“If I disagree with him he will marry another woman, he will say I want children.” (26–35 yr, ITS)

There is general acceptance by Syrian women about the dominant role of the male partner in the decision-making process for fertility and for family planning. Women perceived that men are influenced by social norms and cultural/religious expectations regarding preferences for male children and large families. They discussed their changing roles due to displacement. Statements such as “we used to go out to pay visits” and “we are like men now” point to their perception of changing roles noting that they were used to only go out for social outings in Syria now they need to run errands assuming the tasks given to men in their families.

Whereas the above-mentioned “new” roles were more apparent among the older age group of women participants, the younger women explained about their changing roles in the decision-making process regarding fertility. Women are using their situation as displaced and their economic hardship, as triggers to discuss the issue of limiting or spacing births with their husbands in contrast to their usual norms of decision-making. This is shown in a young woman’s justification for being more involved in decision-making:

“I could not negotiate this issue with him before, if the man wants a child you cannot prevent him, but now I have good reasons to convince him and to say no.”

There were also reports of some women resorting to use contraception without the knowledge of their husband.

Perceptions about contraceptive needs and provision

Women expressed a strong need for contraceptives in consideration of their difficult living conditions, especially those above 25 years of age who wanted to limit their family size to one or two children.

“Women used pills after having ten children, but we have only one or two and want to use the pill now.” (25–36 yr, outside ITS)

In contrast to the statement above, women aged 18–25 who have not completed their desired family size or did not have at least one male child, reported not using contraception. There were some reports of fear of infertility perceived to be induced by modern contraceptive methods within this group.

The dynamics of FGDs pointed to common concerns of Syrian women with different modern contraceptive methods that eventually drive women to resort to natural methods of family planning. Concerns limiting use were the relatively high cost of insertion of IUDs in Lebanon, although this was less of an issue among women residing outside ITSs. Women living in ITS did not favour the use of pills. They were concerned about forgetting to take them regularly while living in crowded and difficult conditions. They also worried about not being able to tolerate the side effects of contraceptive pills and considered them as “additional reasons to get sick” given the difficulties of their lives as refugees.

Perspectives of women about health care

Syrian women talked about their difficulties with RH care services in Lebanon in terms of discriminatory treatment received at health facilities, lack of female providers and the high cost.

Syrian women pointed to the judgmental approaches of care providers, which contributed to their perception of low-quality care received.

“You wait in line like sheep, someone talks badly to you, and another one laughs at you. You bear humiliation after humiliation. After all the humiliation we suffered there, we came here and got humiliated again.” (36–45 yr, outside ITS)

They were also vocal about the lack of female physicians in health centres in Lebanon. Both of the above reasons influenced their preference for Syrian health care providers. Some mentioned seeking care with a female gynaecologist from Syria practicing in Bekaa.

“We need health centres to have female physicians, for example as a dentist and also for women’s problems.” (26–35 yr, outside ITS)

Syrian women complained about the high cost of health care in Lebanon compared to free public services in Syria. They referred to opportunity (long waiting time in health centres) and financial costs that encouraged some of them to go back to Syria whenever possible to receive care at a lower cost.

“It is more expensive now, 20,000 LBP (13 USD) and the doctor prescribes a medication for 15,000LBP (10 USD) or 20,000LBP (13 USD) so that’s approximately 50,000LBP (33 USD) per visit, where are we going to get the money from? The best doctor in Syria costs 500 SP (2.5 USD) and sometimes it is for free.” (26–35 yr, ITS)

“Some of us go back to Syria to get treated or have a surgery because it is very expensive in Lebanon … It is becoming more and more difficult to cross the border now.” (36–45 yr, outside ITS)

Perspectives of health care providers of Syrian women

There was a general agreement between health care providers interviewed that Syrian refugee women expressed a desire to have more children in comparison with their Lebanese counterparts and despite the hardship of displacement.

“The number of deliveries among Syrian refugees is high, it does not stop at a certain thing or a certain age. They are obsessed with kids, maybe they like to reproduce more because of what is happening with them.” (Midwife, hospital)

Providers explained that a large number of the refugee Syrian population in the West Bekaa had been displaced from rural areas in Syria where large families are desired, whereas the urban population residing in Syria is generally of a higher socio-economic background and has few children.

“Those who are from the north of Syria have their own traditions and want to have a large family. The ones from Damascus have different traditions and norms.” (Physician, male, health centre)

In agreement with women, health care providers pointed to the role of aid provided by UN agencies in encouraging women to have more children while being displaced.

“At the beginning of the conflict, many women used to tell me that they want to make use of their time in Lebanon and have many children especially that they perceive medical care to be good in Lebanon and they are covered by UNHCR.” (physician, female, private clinic)

Providers also confirmed women’s concerns about polygamy and how that influenced women’s decisions to have more children and how they play the expected social role either through having more children than they desire or by accepting a polygamous marriage.

“Women are forced to get pregnant because their husbands threaten them that they will get another wife … .Second marriages are really easy for Syrians. Even sometimes, the wife helps her husband to choose a second wife. I often see at my clinic a man with his two wives.” (Physician, male, health centre).

Health care providers reported a demand for contraceptive methods by the Syrian population using the health centres. They noted certain concerns regarding the unavailability of injectable contraceptives that were requested by Syrian women, as well as the relatively high cost of IUD insertion for this population.

“I mostly advise them to insert IUD … we give IUDs for free in this health centre but they need to visit the physician to insert it … the visit costs around 20,000 LBP (13 USD) … .a lot of refugee women come here and ask me for information about contraceptive methods … they ask about injections, this is something they have in Syria.” (Nurse, from health centre)

They pointed to the shortage in contraceptives for free distribution in health centres to cover the need of Syrian refugees in the Bekaa. This is in alignment with women’s reported needs for free or affordable contraceptives.

“We used to have good supply of pills and condoms but no more. There are a lot of Syrian refugees coming and asking for free contraception and we don’t have any more to offer.” (Nurse, public health centre)

“Many women ask for contraception. The Ministry of Health provided us with contraception over a long period of time, we had thousands of different methods. However, they took them all, and now we do not have any birth control pills.” (Physician, male, public health centre)

Providers’ discourses revealed negative attitudes that confirm women’s reported experiences of discriminatory treatment when seeking RH care.

“They are irresponsible and ignorant. Many of them do not commit to appointments. They really give us a hard time … . They exhaust us.” (physician, male, health centre)

“They have children that do not go to school and they could not care less. They are ignorant. There are few educated ones but the uneducated are much more.” (physician, female, private clinic)

Discussion

Earlier studies looking at fertility behaviour among refugees in several settings examined desired and actual number of children, birth intervals, family planning practices and abortion, and explained an increase in fertility as due to the need to replace lost children, while a decrease in fertility was seen as due to the difficult living conditions of refugees.Citation6,Citation26 These studies, however, have failed to take into account the contextual factors and the complex process that influences women’s fertility behaviours under conditions of displacement. In this study, we focused on Syrian refugee women’s fertility behaviours in Al-Marj, Bekaa, revealing the complex interplay of contextual factors some encouraging the maintenance of high fertility and some conducive to lowering fertility. In parallel, we identified issues around the lack of affordability and acceptability of the offered methods of contraception with regard to women’s situation and needs, as well as the discrimination experienced in the Lebanese health system.

Although this refugee population has moved to a neighbouring country where they share the language and are familiar with cultural characteristics, our findings highlight the extent to which these refugee women are challenged by the contradictions between their social norms and their adverse current situation, when making decisions about their fertility. The maintenance of high fertility levels is encouraged by women’s preference for a large family, for male children, their wish to replace children lost to war, their fear from the practice of polygamy that is exacerbated by their living conditions in Lebanon, and the expected aid from UN agencies. On the other hand, adverse changes in their lives brought about by war and displacement, the challenges faced in the legal system for registering marriages and births as well as the difficulties in children’s schooling are discouraging women from achieving their desired large family size.

The tension created by these factors is influencing women’s role in the decision-making process regarding fertility. Women’s endured social and economic hardship is serving as an impetus to take an active role in the decision-making process and is used as an argument with their husbands for limiting the number of children in their family or opting to use contraception without their spouse’s knowledge. This reveals a change in social roles of women. In contrast, despite being overwhelmed by too many children, some women continued to want more children fearing that their husbands take a second wife, a phenomenon also documented among Afghan refugees in Iran.Citation27 Women used a careful balancing act while trying to adapt to the various circumstances that influence their wish to have or limit the number of their children. Although they felt empowered by their new situation to get involved in this male-dominated process of decision-making, they were also carefully considering the consequences especially polygamy. This is a practice that although was present on a small scale in Syria before the conflict,Citation15 has been well articulated by refugee women in this community as a major concern.

UNHCR and NGOs facilitated Syrian women’s access to health care and while focusing on maternal health and offering aid to pregnant women and their families they played a significant role in determining women’s willingness to have more children. However, with the prolongation of the conflict situation over years the UNHCR support diminished leaving the community with even more accentuated experience of hardship, which is now influencing their decision in limiting their family size.

Refugee Syrian women have to deal with a host culture and a health system that is non-responsive to their needs. The discourse of providers interviewed in this study reveals some long-standing stereotypes that emanate from close contact of the two populations over the years and confirm women’s reports of discriminatory treatment at health care centres. Health care providers were unaware of fertility levels and behaviours prominent in Syria before the conflict and therefore were shocked by the fertility behaviours of Syrian refugee women when comparing them to the Lebanese population. The discriminatory treatment received in health care settings had a major contribution in limiting women’s access to health care. Other barriers include opportunity and financial costs of contraceptives, limited access to preferred types of methods and the unavailability of female providers. These barriers were reported in previous studies in SyriaCitation28 and among Syrian refugees in Lebanon.Citation18,Citation29–31 An important feature in health care use in this population is the repeated travel between Syria and Lebanon to receive health care; a phenomenon that is not usually found among refugee populations elsewhere.

The Lebanese health care system is facing many challenges in managing the influx of Syrian refugees in the absence of crisis preparedness plans and official acknowledgment of the refugee crisis as well as the lack of funds directed toward refugee population health needs. Providers’ report of lack of supplies of contraceptives is one example identified in our study. Timely access to RH supplies has been reported as a challenge in other humanitarian settings.Citation32 The Lebanese health care system that relies mostly on the private sector and on the limited capacity of the host communities to provide services through NGOs presents other significant challenges for the organisation of health care in crisis situations.Citation33 The ongoing influx of Syrian refugees has created a large demand on providers and health centres with limited capacity. This has undesirable implications on the care provided and can explain women’s reports of discontent with the quality of care received. A similar situation has been reported in an evaluation of RH services offered to Syrian refugees in Jordan.Citation34

In addition to showing that the Lebanese health system is non-responsive to the RH needs of refugee women, our findings point to the misfit of emergency health care provision programmes, such as the MISP, in addressing these needs. This confirms the necessity of planning and providing family planning services through considerations given to contextual factors and cultural norms of the refugee population.Citation9,Citation10

Our study focused on women’s perspectives and because of limited resources and recognised sensitivities in refugee settings, it was not possible to include men in the study. This can be considered in future research aiming to improve our understanding of this community regarding fertility behaviour and contraceptive use. We were also not able to examine differences in access to and use of contraception based on the region of origin of the refugees in Syria. The cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow us to capture changes in perceptions and behaviour across different points in time in the lives of the refugees.

The contextual factors and their complex interplay in affecting fertility outcomes and use of RH services as described above provide additional insights to what is known about fertility behaviour in conflict situations.Citation6,Citation26 We consider that our close look into the mechanisms of change in fertility behaviour is a valuable contribution to the knowledge accumulated in this area in emerging refugee situations. These insights point to the need to give attention to changes in fertility behaviour and access to services among refugee populations who are experiencing displacement and facing the challenges of differences in health care and cultural contexts.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all women and health care providers who participated in the study. They acknowledge the seed grant received from the Reproductive Health Working Group (RHWG) for the completion of this project and thank Dr Belgin Tekce for her support in revising earlier drafts of this paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [Internet]. Geneva: UNHCR; c2001-2017. Syrian Regional Refugee Response – Inter-agency information sharing portal. [cited 2015 Dec]. Available from: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php

- McGinn T. Reproductive health of war-affected populations: what do we know? Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2000;26(4):174–180. doi: 10.2307/2648255

- Holck SE, Cates W Jr. Fertility and population dynamics in two Kampuchean refugee camps. Stud Fam Plann. 1982;13(4):118–124. doi: 10.2307/1965707

- Moss N, Stone MC, Smith JB. Fertility among Central American refugees and immigrants in Belize. Hum Organ. 1993;52(2):186–193. doi: 10.17730/humo.52.2.d5148v8415776537

- Gagnon AJ, Merry L, Robinson C. A systematic review of refugee women’s reproductive health. Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees. 2002;21(1):1–17.

- Georgiadis K. Migration and reproductive health: a review of the literature. London: University College London, Department of Anthropology; 2008. Working Paper 1/2008.

- Patel P, Roberts B, Guy S, et al. Tracking official development assistance for reproductive health in conflict-affected countries. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000090

- World Health Organization. Women and health: today’s evidence tomorrow’s agenda. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

- 2004 Inter-agency global evaluation of reproductive health services for refugees and internally displaced persons [internet]. Inter-Agency Working Group (IAWG); 2004. Available from: http://iawg.net/resource/2004-inter-agency-global-evaluation-reproductive-health-services-refugees-internally-displaced-persons/

- Krause SK, Otieno M, Lee C. Reproductive health for refugees. Lancet. 2002;360:s15–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11803-4

- UNHCR. Refocusing family planning in refugee settings: findings and recommendations from a multi-country baseline study. Geneva: UNHCR; 2011; Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/4ee6142a9.pdf

- McGinn T, Austin J, Anfinson K, et al. Family planning in conflict: results of cross-sectional baseline surveys in three African countries. Confl Health. 2011;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-5-11

- World Bank. World development indicators 2012. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2012. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6014

- Lebanon Country profile. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/Views/Reports/ReportWidgetCustom.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=LBN

- Central Bureau of Statistics, Government of Syria. Family health survey in Syria 2002. Damascus: Government of Syria; 2002.

- Syrian Commission for Family Affairs. The community-based study on Syrian women’s attitudes and beliefs on family planning. Damascus: Government of Syria; 2006.

- Central Bureau of Statistics, Government of Syria. Family health survey in Syria 2009. Damascus: Government of Syria; 2011.

- Reese Masterson A, Usta J, Gupta J, et al. Assessment of reproductive health and violence against women among displaced Syrians in Lebanon. BMC Women’s Heal. 2014;14(1):2242.

- Doctors without Borders (MSF) [internet]. Geneva: MSF; c2017. Lebanon: heat wave adds to the woes of Syrian refugees in Bekaa Valley. 2015 Aug 20 [cited 2015 Dec]. Available from:http://www.msf.org/article/lebanon-heat-wave-adds-woes-syrian-refugees-bekaa-valley

- Doctors without Borders (MSF). Syrian refugees in Lebanon: this crisis cannot be forgotten. The Daily Star [Internet]. 2015 Jan 31 [cited 2015 Dec]. Available from: http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2015/Jan-31/285925-syrian-refugees-in-lebanon-this-crisis-cannot-be-forgotten.ashx

- United Nations News Center [Internet]. New York: United Nations; c2017. Conditions of Syrian refugees in Lebanon worsen considerably, UN reports. 2015 Dec 23 [cited 2015 Dec]. Available from: http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=52893#.VswINOYY7A0

- Harb C, Saab R. Social cohesion and CLI assessment – save the children report. London: Save the Children & American University of Beirut; 2014.

- UNHCR. Health services for Syrian refugees in Bekaa. Geneva: UNHCR; 2014.

- Morgan DL, Krueger RA. When to use focus groups and why. In: Morgan DL, editor. Successful focus groups: advancing the state of the art. Thousands Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1993. p. 3–19.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Majelantle RG, Navaneetham K. Migration and fertility: a review of theories and evidences. J Glob Economy. 2013;1(101):2.

- Tober DM, Taghdisi M, Jalati M. “Fewer children, better life” or “as many as God wants”? Family planning among low-income Iranian and Afghan refugee families in Isfahan, Iran. Med Anthropol Q. 2006;20(1):50–71. doi: 10.1525/maq.2006.20.1.50

- Bashour H, Abdulsalam A. Syrian women’s preferences for birth attendant and birth place. Birth. 2005;32(1):20–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00333.x

- Aptekman M, Rashid M, Wright V, et al. Unmet contraceptive needs among refugees. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:e613–e619.

- Benage M, Greenough GP, Vinck P, et al. An assessment of antenatal care among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Confl Health. 2015;9:8. doi: 10.1186/s13031-015-0035-8

- Huster K, Patterson N, Schilperoord M, et al. Cesarean sections among Syrian refugees in Lebanon from December 2012/January 2013 to June 2013: probable causes and recommendations. Yale J Biol Med. 2014;87:269–288.

- Casey S, Chynoweth S, Cornier N, et al. Progress and gaps in reproductive health services in three humanitarian settings: mixed-methods case studies. Confl Health. 2015;9(suppl 1):S3. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-S3

- Gulland A. Syrian refugees in Lebanon find it hard to access healthcare, says charity. British Med J. 2013;346:1869.

- Krause S, Williams H, Onyango MA, et al. Reproductive health services for Syrian refugees in Zaatari camp and Irbid City, Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan: an evaluation of the Minimum Initial Services Package. Confl Health. 2015;9(suppl 1):54. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-S4