Abstract

Continuing international conflict has resulted in several million people seeking asylum in other countries each year, over half of whom are women. Their reception and security in overburdened camps, combined with limited information and protection, increases their risk and exposure to sexual violence (SV). This literature review explores the opportunities to address SV against female refugees, with a particular focus on low-resource settings. A systematic literature review of articles published between 2000 and 2016 was conducted following PRISMA guidelines. Databases including Medline (Ovid), PubMed, Scopus, PsychINFO, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library. Grey literature from key refugee websites were searched. Studies were reviewed for quality and analysed according to the framework outlined in the UNHCR Guidelines on Prevention and Response of Sexual Violence against Refugees. Twenty-nine studies met the inclusion criteria, of which 7 studies addressed prevention, 14 studies response and 8 addressed both. There are limited numbers of rigorously evaluated SV prevention and response interventions available, especially in the context of displacement. However, emerging evidence shows that placing a stronger emphasis on programmes in the category of engagement/participation and training/education has the potential to target underlying causes of SV. SV against female refugees is caused by factors including lack of information and gender inequality. This review suggests that SV interventions that engage community members in their design and delivery, address harmful gender norms through education and advocacy, and facilitate strong cooperation between stakeholders, could maximise the efficient use of limited resources.

Résumé

Les conflits internationaux forcent chaque année plusieurs millions de personnes, dont la moitié de femmes, à chercher asile dans d’autres pays. La surpopulation des camps où elles sont accueillies, les lacunes de la sécurité associées aux limitations de l’information et de la protection, multiplient leur risque d’être exposées à la violence sexuelle. Cette étude des publications s’est intéressée aux possibilités de lutter contre la violence sexuelle à l’égard des réfugiées, en mettant particulièrement l’accent sur les environnements à faibles ressources. Une étude systématique des articles publiés entre 2000 et 2016 a été menée conformément aux directives PRISMA. La recherche a porté sur des bases de données, notamment Medline (Ovid), PubMed, Scopus, PsychINFO, CINAHL, ainsi que la littérature grise de la bibliothèque Cochrane tirée des principaux sites web de réfugiés. Les études ont été examinées pour évaluer leur qualité et analysées selon le cadre d’action préconisé dans les Principes directeurs du HCR pour la prévention et l’intervention en matière de violence sexuelle et sexiste contre les réfugiés. Vingt-neuf études répondaient aux critères d’inclusion, dont sept études sur la prévention, 14 sur l’intervention et huit sur les deux thèmes. On dispose d’un nombre limité d’activités de prévention et d’intervention en matière de violence sexuelle évaluées de manière rigoureuse, en particulier dans le contexte des personnes déplacées. Néanmoins, les données émergentes montrent qu’une priorité accrue aux programmes dans la catégorie de l’engagement/la participation et la formation/l’éducation a le potentiel de cibler les causes sous-jacentes de la violence sexuelle. La violence sexuelle à l’égard des réfugiées est causée par des facteurs tels que le manque d’information et l’inégalité entre hommes et femmes. Cette analyse suggère que les interventions qui associent les membres de la communauté à leur conception et leur mise en œuvre, s’attaquent aux normes sexuelles néfastes par l’éducation et le plaidoyer, et facilitent une coopération resserrée entre les parties prenantes pourraient optimiser l’utilisation judicieuse de ressources limitées.

Resumen

Debido al conflicto internacional continuo, cada año varios millones de personas, más de la mitad de las cuales son mujeres, buscan asilo en otros países. Su recepción y seguridad en campos sobrecargados, combinadas con información y protección limitadas, aumentan su riesgo y exposición a la violencia sexual (VS). Esta revisión de la literatura exploró las oportunidades para abordar la VS contra mujeres refugiadas, con un enfoque específico en entornos de bajos recursos. Se realizó una revisión sistemática de la literatura de artículos publicados entre los años 2000 y 2016, siguiendo las directrices de PRISMA. Se realizaron búsquedas en bases de datos tales como Medline (Ovid), PubMed, Scopus, PsychINFO, CINAHL y la literatura gris de la Biblioteca Cochrane, de sitios web clave sobre refugiados. Los estudios fueron revisados para determinar su calidad y analizados según el marco resumido en la publicación de ACNUR titulada Violencia sexual contra los refugiados: directrices relativas a su prevención y respuesta. Veintinueve estudios reunieron los criterios de inclusión. De esos, siete estudios abordaron prevención; 14 estudios, respuesta; y ocho, ambas. Existen números limitados de intervenciones de prevención y respuesta a VS que han sido evaluadas rigurosamente, especialmente en el contexto de desplazamiento. Sin embargo, la evidencia emergente muestra que mayor énfasis en programas en la categoría de participación y capacitación/formación tiene el potencial de encarar las causas subyacentes de VS. VS contra mujeres refugiadas es causada por factores tales como falta de información y desigualdad de género. Esta revisión indica que las intervenciones contra VS que incluyen a miembros de la comunidad en su diseño y ejecución, abordan normas de género perjudiciales por medio de educación y actividades de promoción y defensa, y facilitan una sólida cooperación entre las partes interesadas, podrían maximizar el uso eficiente de recursos limitados.

Background

By the end of 2016, continuing conflicts, threats of persecution, violence and human rights violations have led to the displacement of an estimated 65.6 million people globally, of whom 22.5 million are refugees.Citation1 This is the highest refugee population ever recorded and much of the growing refugee population was driven by the Syrian conflict between 2012 and 2015. However, other conflicts in Iraq, Yemen and Sub-Saharan Africa have also contributed to the global refugee crisis.Citation1,Citation2 As a result, the main country of origin of refugees in 2016 was Syria, followed by Afghanistan, South Sudan and Somalia.Citation1,Citation2 Over half of all refugees are being hosted by just 10 countries, of which nine are low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) without sufficient resources to sustain and support these refugee numbers.Citation1,Citation3 Europe also received an increased influx of refugees with two million arriving between 2015 and 2016, 55% being women and girls.Citation4–8

Sexual violence (SV) is experienced by many women living in conflict and post-conflict settings, during transit, and within destination countries.Citation9–13 A recent systematic review estimated that 21% of women in conflict countries have experienced SV either by a stranger or an intimate partner.Citation14 Another study carried out in Belgium and the Netherlands, which interviewed 223 refugees in 2012, showed that 69.3% of refugee women experienced SV since their arrival in the European Union.Citation15 However, data available on SV prevalence against female refugees are limited as incidents are often not reported or documented due to lack of SV training of humanitarian staff, SV-related stigma or lack of information about available services.Citation16,Citation17

This article is focused on SV, which is defined as “any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic (…) against a person’s sexuality using coercion (…)”.Citation18 SV is a form of gender-based violence (GBV), which describes violence against women (VAW) perpetrated predominately by men against women and girls as a result of unequal power relations between genders. SV can be perpetrated by strangers, acquaintances, family members and intimate partners, the latter identified as sexual inter-personal violence (IPV).Citation19,Citation20 Although men can be subjected to SV, women are more vulnerable to SV due to entrenched inequities and discrimination against women.Citation14,Citation21,Citation22 This is a consequence of sociocultural gender norms and expectations that situate women at a disadvantage compared to men and contribute to their increased risk of violence. Displacement and crisis situations can further aggravate gender inequality and with it the risk of SV due to disruption of social structures and loss of extended family support, economic and physical insecurity, lack of access to information and resources or services as well as an uncertain legal status.Citation12,Citation15,Citation23 SV against female refugees includes rapes, sexual harassments, forced marriage in order to gain male protection and survival sex in return for documents, food or transport.Citation12,Citation13,Citation24 Women are targeted by smugglers, human traffickers, male refugees, humanitarian staff or strangers.Citation11–Citation12 Citation13 Consequences of SV are severe and can lead to many short- and long-term health consequences, such as unintended pregnancies, transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, as well as mental health disorders including anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression. In addition, sexually abused women are often stigmatised, which further aggravates their mental health, and can result in non-reporting of abuse, suicide, social rejection or murder of victims by the community or family members.Citation25,Citation26 SV survivors are also at increased risk of being subjected to subsequent abuse, further aggravating long-term health outcomes.Citation15

Despite attempts by refugee host countries, UN and humanitarian organisations to implement protective measures, basic security measures and protection guidelines are often not adequately implemented, as shown by recent situation assessments in refugee-receiving countries.Citation10,Citation16,Citation17,Citation27 Many international NGOs and UN agencies have published prevention and response guidelines with the most relevant ones formulated by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and include the following:

Sexual Violence against Refugees. Guidelines on Prevention and Response (UNHCR, 1995)Citation28

UNHCR Handbook for the Protection of Women and Girls (UNHCR, 2008)Citation29

Action against Sexual and Gender-based Violence: An Updated Strategy (UNHCR, 2011)Citation30

Guidelines for Integrating Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action: Reducing Risk, Promoting Resilience, and Aiding Recovery (IASC, 2015)Citation31

The Minimum Standards for Prevention and Response to Gender-based Violence in Emergencies (UNFPA, 2015)Citation32

In response, the UNHCR, which has the primary UN mandate of protecting and supporting refugees, has formulated comprehensive guidelines that are specific for the prevention of and response to SV against refugees.Citation28 The guidelines have an overarching human-rights based approach, which aims to address the root causes of SV and ensure that international human rights standards are protected and promoted. UNHCR recognises the significance of harmful gender norms and power dynamics in regard to SV and recommends human rights- and community-based approaches including: initiatives that empower women, through targeted livelihood interventions or creation of women’s groups; ensuring confidentiality for SV survivors and legal action for perpetrators; safety and security measures including secure accommodation; and increased education regarding SV.Citation28–30

Despite these guidelines, there is a gap in understanding how to implement SV prevention and response programmes across diverse humanitarian settings and in particular within transit or in temporary refugee settlements.Citation33 This review addresses this “know-do” gap, synthesising published literature on the effectiveness of interventions to prevent and respond to SV against female refugees. The review focuses on promising approaches aligned with UNHCR guidelines that have evidence of impact on SV prevalence in humanitarian settings with limited resources, as the majority of refugees are hosted by LMICs.Citation1 While the focus is on refugees protected by international law, displaced people in refugee-like situations, who are also in need of protection but might not meet the definition of the 1951 UN Convention, are also included.Citation1,Citation2

Methods

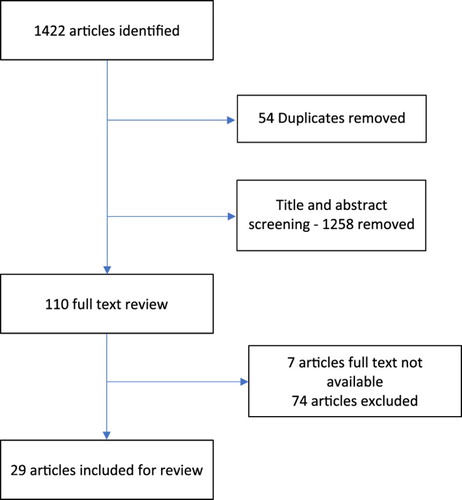

A literature search was conducted in July–August 2016. The review focused on peer-reviewed articles accessed from the following databases: Medline (Ovid), PubMed, Scopus, PsychINFO, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library. Grey literature was reviewed from websites of the World Health Organisation (WHO), UNHCR, Women’s Refugee Commission, United Nation Population Fund and the World Bank. In addition, reference lists of relevant articles were manually searched. The review was limited to articles and reports in English and German, which have been published between 1 January 2000 and 31 August 2016. Search terms encompassing variants of SV, humanitarian crisis settings and programme evaluation were incorporated. A summary of search terms can be found in .

Table 1. Search strategy

The title and abstract of all articles were screened for eligibility according to specific inclusion and exclusion criteria as described in . Articles and reports, which matched the inclusion criteria, were then obtained as full text and screened for further eligibility according to content. Summary data from all included articles were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet for analysis by both authors.

Table 2. Eligibility criteria

Quality assessment

Included studies were evaluated for the quality of their methodological rigour, and rated as either “weak”, “moderate” or “strong” and assessed with a different appraisal tool according to the type of study: quantitative studies were evaluated with the quality assessment tool for quantitative studies of the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP).Citation34 For qualitative studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality appraisal toolCitation35 was chosen and for systematic reviews, the AMSTAR measurement tool was used.Citation36,Citation37 The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool was used to review included mixed methods studies.Citation38

Analysis of studies

Included studies were reviewed and evaluated against a framework based on the UNHCR Sexual Violence against Refugees: Guidelines on Prevention and Response, including subsequent updates, due to its specificity to the topic of review.Citation28–30 The framework is categorised into prevention and response strategies and sub-categories, which shared common protective elements for either prevention or response. Prevention was sub-categorised into four sections: (a) participation and engagement, (b) safety, (c) legal protection and (d) education and training. Response was divided into the following four sections: (a) treatment and counselling, (b) protection from repeat abuse, (c) legal protection and (d) education and training. Articles were analysed according to this framework to evaluate the focus and orientation of available evidence and to identify research gaps and intervention opportunities.

provides an overview of the guidelines and the applied framework.

Table 3. UNHCR guidelines with framework of analysis

Results

The literature search resulted in 1422 articles. After removing 54 duplicates and a screening of title and abstract of the remaining articles, 110 articles were included for further review. The full text of seven articles could not be located and these were excluded. After full-text screening, 74 articles were excluded due to incomplete information on interventions described, uncertainty on whether or how SV was targeted, or when implemented in a high-resource setting. At the end of this process, 29 articles were included for the synthesis (see ). Included articles consisted of nine qualitative studies, six quantitative studies, two mixed method studies, seven reviews and five reports. Seven publications addressed prevention, 14 focused on response and 8 publications addressed both. Finally, 12 studies were of “weak”, 14 of “moderate” and 3 of “strong” quality.

summarises the key characteristics of the included articles and summarises the studies against the UNHCR Framework.

Prevention

Identified articles discussed SV prevention with respect to male involvement in protection measures, community mobilisation as well as skills and livelihood enhancing strategies similar to the recommendations of the UNHCR guidelines. Several articles addressed more than one guideline category.

Participation and engagement

Nine articles described interventions which engaged refugee communities or men in SV prevention efforts.

One trial, of weak quality, conducted in conflict-affected Côte d’Ivoire, engaged men in reflective discussion groups and showed that even a short but intensive intervention period of four months was successful in changing negative gender norms and expectations, increased conflict management skills and respect for women’s rights. The intervention recruited 174 men and their female partners and conducted a survey about the incidence of IPV, including sexual IPV, pre- and one-year post-intervention. According to the surveys one year after the intervention, women reported experiencing less sexual IPV and more men agreed with the statement that women have a right to refuse sex regardless of the circumstances. The strength of this study was the inclusion of female partner reports in the analysis, which reduced the possible bias inherent with relying on reports given by participating men.Citation39

According to Gurman,Citation40 SV reduction strategies also have to consider the influence of social networks and the local community on the actions of the individual. Community-based interventions appear most suitable as people can be engaged as agents for social change.Citation40 One promising strategy is the use of short films and video projects in order to educate the local community and to initiate a public discussion about GBV and SV.Citation41–43 One multi-year participatory video project rated as being of weak quality, which took place in Thailand along the Thai-Myanmar border and in Rwanda, Liberia, South Sudan and Uganda in Africa, actively engaged the community and included different stakeholders such as ministries, religious leaders and youth and women's groups in the creation of several targeted videos, which educated about GBV, including SV.Citation40 Each public screening was then followed by reflective discussions. A qualitative evaluation of 18 focus group discussions showed that participants credited the project with an increased awareness and respect for women’s rights, more equitable gender dynamics within relationships and families, a decrease in forced early marriage and increased reporting of GBV including SV and use of related services. Nevertheless, it was also recognised that continuous activism is still necessary to change gender norms long-term as some abused women still deal with stigma and hence, may choose to remain silent.Citation40 In a qualitative study in Rwanda, refugees also expressed the need for collaboration between camp leaders, local communities and NGOs to avoid a top-down intervention approach and thereby increase accountability, ownership and acceptability of protective services.Citation43 One intervention of weak quality in a refugee camp in Darfur showed that actively consulting and engaging female refugees and camp leaders in developing solutions to safety concerns was more effective and sustainable than endeavouring to enforce existing guidelines and policies.Citation44 Another article by Spangaro et alCitation41 found that SV interventions designed and implemented with active involvement of the community were associated with greater reductions in SV exposure and incidence, concluding that engagement of targeted communities may be fundamental to the success and sustainability of SV prevention efforts.

The empowerment of women through vocational skills training and education has also been found to be promising as an attempt to increase women’s livelihoods and decrease risk of SV.Citation43,Citation45Citation46–Citation47 In Sierra Leone, this approach was reported to increase women’s choices and capability to earn a sustainable income and thereby decreased women’s vulnerability to sexual exploitation.Citation46 However, projects supporting women’s economic opportunities can also increase their risk to IPV, which may include sexual IPV.Citation47 Ray et alCitation47 strongly recommend engaging with men in any livelihood programmes. Implementing these interventions in isolation is discouraged given the complexity of GBV in displacement situations. Despite the recognition that livelihood interventions might be crucial for protecting refugee women, there was limited evidence among the included studies with regard to the effectiveness of economic opportunities in displacement settings for reducing SV. In many hosting countries, governments apply significant restrictions on the right of refugees to work.Citation47

None of the identified studies evaluated efforts to conserve the original community structures from the country of origin within refugee camps or on how to engage refugee women in the design, management or leadership of SV protection measures as recommended by UNHCR.

Safety

Eleven studies evaluated the impact of SV prevention on increasing personal and environmental safety.

All studies within the safety domain addressed the risk of SV that women faced while collecting firewood.Citation41Citation42 Citation43 Citation44–Citation45,Citation48Citation49 Citation50 Citation51 Citation52–Citation53 Intervention approaches included firewood provision or training in fuel-efficient stove production.Citation41–43 One comprehensive evaluation of a firewood project in Kenya, rated as being of moderate quality, provided firewood in an attempt to reduce rapes. While the incidence of rape was 10% lower during wood collection, it increased in other situations within the same camp.Citation53 In addition, the monetary value of wood increased during the project and some women collected additional firewood for income generation, augmenting their risk, despite their own fuel needs being supplied.Citation52,Citation53 The project was assessed as neither cost-effective nor sustainable, and was found to increase tensions between refugee and host communities as the firewood provision was resented by host communities who did not receive the same assistance.Citation53 Tappas and colleagues reviewed the provision of fuel-efficient stoves to reduce the trips necessary to collect firewood and reduce SV exposure of women and found the need to purchase fuel can in turn increase the economic burden and SV vulnerability.Citation43 Despite its questionable impact, stove or firewood provision remains a major approach by humanitarian organisations to increase safety and decrease exposure to SV.Citation51 However, one project, in a Sudanese displaced persons camp, showed a promising approach, which included the formation of a women-led firewood patrol committee. Regular meetings of these women allowed them to discuss any safety concerns and it increased trust, problem-solving skills and ultimately women’s safety.Citation42,Citation44,Citation52

Legal protection

Five articles, among them three systematic reviews, discussed legal interventions, such as protective laws, policies, guidelines and training programmes as a preventative measure against SV.

The limited literature on protective legal interventions in the prevention of SV against refugees indicates a severe lack of evidence available. Moreover, included literature discussed interventions with limited effectiveness as evaluations showed that refugees are insufficiently educated about their rights or available legal mechanisms and may regard SV as something shameful but inevitable, thereby somewhat “normalising” SV. Therefore, many SV cases may not be reported despite protective legal mechanisms in place.Citation41–43,Citation54 Legal interventions are, however, considered important components for SV prevention to deter perpetrators through comprehensive laws and policies.Citation42 Nevertheless, a systematic review of moderate quality by Spangaro et alCitation42 found that even if legal policies and mechanisms are in place and SV charges are reported, many cases have not been prosecuted, leaving many SV perpetrators unpunished and SV survivors without justice. Consequently, protective policies and laws are limited in their impact of deterring future or repeat SV perpetrators.Citation41–43

Education and training

Seven studies evaluated education and training interventions for SV prevention.

One weak quality study implemented by UNIFEM in 11 refugee camps in Darfur between 2008 and 2011 intended to increase the internal security for female refugees by training camp leaders, police and humanitarian staff in gender sensitivity and GBV/SV protection protocols.Citation44 The training resulted in increased awareness and understanding of VAW and improved capabilities and problem-solving skills of the community to protect refugee women against SV more efficiently.Citation44 Thompson et alCitation44 stressed the importance of the involvement of camp leaders in interventions and a participatory training, with regular continuous training, as a long-term strategy to change social norms and harmful attitudes that result in SV. Moreover, in this study, the involvement of religious leaders was shown to play an important role to reinforce important messages against SV.Citation44 Another training programme implemented in Guinea further showed success in SV prevention through the deployment of “community trainers” in refugee settlements, who facilitated and educated refugees about SV and involved the community in a participatory problem-solving process to establish SV preventative systems. The programme also succeeded in recruiting refugees, including women, to be trained as paraprofessional social workers to support awareness-raising activities such as through the organisation of women’s groups, aiming to inform and sensitise women about their rights in cases of abuse, and has led to an increased uptake of SV-related services.Citation41,Citation42 Four studies also focus on encouraging further education and skills training as promising approaches for the prevention of sexual exploitation of refugees.Citation45–47 However, in some circumstances, economic opportunities for displaced women also increased the exposure to sexual harassment or attacks by employers, especially if working illegally, as women may fear deportation or detention if they seek help from the authorities or police.Citation47 Limited access to employment opportunities for displaced girls and women without family or spousal support is of particular concern as food rations provided by humanitarian agencies are often insufficient, which may force girls and women to seek precarious means to earn an income through prostitution or illegal domestic work, where they risk sexual harassment. Ray et alCitation47 strongly recommend that governments need to grant refugee women legal status as quickly as possible and allow them to work legally in the country of refuge to prevent the cycle of vulnerability that favours sexual exploitation.

Two systematic reviews on SV in humanitarian settings worldwide, both of moderate quality, determined that training programmes for volunteers, staff, community leaders and refugees have the greatest impact on reducing the risk of SV, when combined with multi-component interventions, which may include community discussions and awareness-raising activities.Citation41,Citation42 According to Spangaro et al,Citation41,Citation42 this is due to the fact that this intervention approach better addresses the broad spectrum of issues, which initially led to the exposure and risk of SV.

Response

The identified literature predominately focused on treatment and counselling as a response to SV. Several articles addressed more than one guideline category.

Treatment and counselling

Eighteen studies addressed the treatment of SV and counselling of SV survivors with only one study of strong quality.

The majority of the identified literature predominately focused on alleviating PTSD through individual or group therapy and support groups with skills training; these have had some success in alleviating mental distress and increasing perceived social support.Citation41,Citation42,Citation44Citation45–Citation46,Citation55Citation56 Citation57 Citation58 Citation59 Citation60–Citation61 However, studies often lacked rigorous methodology and reporting, especially if conducted in conflict areas.Citation56,Citation57 In a weak quality trial conducted in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), female SV survivors with high levels of PTSD, anxiety and depression were randomly assigned to either individual support or cognitive processing therapy (CPT). Evaluations showed that women completing the CPT intervention recorded greater reduction in mental health distress than women receiving individual support only. Additionally, functional impairment was also significantly decreased in the CPT intervention group.Citation55 Another intervention, implemented in a conflict setting of Congo, showed that psychological support provided by trained psychologists can successfully reduce SV trauma-related impairment by around 60% and its benefit was maintained up to two years after the intervention.Citation58

Five of these 16 studies also suggest that the inclusion of traditional rituals helped SV survivors to deal with trauma and build resilience.Citation41,Citation42,Citation59,Citation60,Citation62 According to a moderate quality study by Stark,Citation60 traditional healing ceremonies held in communities for former girl soldiers who survived SV during the conflict in Sierra Leone supported their personal healing and reintegration process into society. Another study from Sierra Leone, which interviewed local social workers and women who had survived war-related SV, showed that a personal care approach, which includes directive advice, self-disclosure and personal involvement of social workers, who were often SV survivors themselves, was greatly appreciated by help-seeking women and seen as a source of knowledge and courage.Citation59 These findings are reinforced by the analytical analysis of a failed GBV/SV intervention in a displaced people camp in Eritrea, which attempted to provide health services and individual counselling to SV survivors of the Saho ethnic group after the second Ethiopia–Eritrea war. Most women did not attend those services and later evaluations concluded that the implemented intervention might have imposed models of Western psychotherapy, which were insufficient to attend the needs of SV survivors in Eritrea, as Saho women are more accustomed to group support with women in their community facing similar issues. Therefore, traditional or community support systems were not fully considered and might have affected the impact of the intervention.Citation63

Leskes et alCitation61 further evaluated two psychosocial programmes in Liberia, which were implemented for three months each by two different local NGOs. The evaluation compared their respective interventions, which included one intervention with individual counselling and another one with support group and skills training for income generation. The aim of the evaluation was to measure the impact on stress and trauma reduction experienced by SV survivors. Both interventions had positive effects, although for many participants their stress was not due to SV experience alone, but was compounded by ongoing socio-economic deprivation.Citation61

Only four articles evaluated healthcare services in regard to SV response.Citation48,Citation49,Citation63,Citation64 One weak quality study, situated in Colombia, stressed the importance of a culturally sensitive integrated response to SV that allowed vulnerable women to access comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services. The project closely collaborated with different local governmental and civil society organisations, such as health councils, health committees, pastors, women’s groups and youth networks, to create strong links with other relevant services such as legal aid, and to challenge local attitudes and social mechanisms that condone SV through awareness-raising campaigns. This approach was seen as essential to the achievement of the project to increase the visibility of available services and to increase access to appropriate care.Citation46 In addition, Henttonen et alCitation64 further found that appropriate health services require regular training in SV of all health staff as well as a stronger orientation of services towards adolescents to maintain proper care. Particularly adolescent women were found to be vulnerable to SV, which required health services to offer youth-friendly services with special hours to better meet their need of care in case of SV.Citation64

A strong quality study by Wirtz et alCitation49 and a weaker one by Vu et alCitation48 described the development and testing of the ASIST-GBV screening tool, which was specifically designed for conflict areas of Colombia and Ethiopia to increase timely identification and referral of SV survivors for treatment and appropriate services. The tool has been shown to be accurate, practical and easy to use, adaptable to context, specific to women’s and girl’s needs and suitable for resource-constrained humanitarian settings. Collected patient data can be linked with reporting and monitoring systems, such as GBV-IMS, to avoid duplication of information and re-traumatisation of abused women. The ASIST-GBV screening tool is to date the only tool being tested in a humanitarian context, which does not only target IPV. However, the acceptability of the tool by end-users, such as refugees and service providers, has not been extensively studied and is currently being evaluated.Citation48,Citation49 Despite benefits of early SV detection, screening is not advised in the absence of a functioning and efficient referral system in place.Citation49

Protection from repeat abuse

Eight included studies addressed this domain of the UNHCR framework. One study of strong methodological rigour by Lattu et alCitation54 explored various mechanisms in place in different refugee settings in case of sexual exploitation and abuse, in particular if committed by humanitarian staff. This qualitative researchCitation54 showed that camp residents were often hesitant and fearful to complain and were insufficiently informed about how to protect themselves from abuse or how to safely report sexual misconduct. Therefore, refugees suggested firing humanitarian staff found guilty of perpetrating SV, and that displaced communities needed to be better informed about their rights, including how to access freely available humanitarian services. Awareness-raising activities, such as workshops and youth drama clubs, further proved to be effective in initiating discussions within displaced communities about SV and safe reporting. Moreover, collaboration with gatekeepers, such as camp leaders, was found to be essential for successful implementation of related interventions.Citation54 Another study in Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya further explored community mechanisms in response to IPV, including sexual IPV, and discovered a hierarchy of responses, which showed that community-based responses, which often involved negotiations with community leaders and relatives, were preferred to services provided by humanitarian staff. This was also due to the fact that many refugees were mistrusting of services implemented by international agencies as they believed them to act with a top-down approach and to act only in favour of women and against the interest of the involved families. However, the study also showed that community measures do not necessarily result in the protection of abused women and can even support re-victimisation, as many women were blamed for their own abuse at the hands of their partners.Citation43,Citation65 In addition, included literature also pointed towards the importance of changing harmful gender norms, raising public awareness about SV and providing economic opportunities to female refugees to decrease their vulnerability to repeated sexual exploitation as well as to address the underlying social mechanisms that lead to repeat abuse of female refugees.Citation40Citation41–Citation42,Citation45,Citation50

Legal protection

Five studies discussed legal interventions such as legal aid services and prosecution of SV offences but there was limited evidence regarding their effectiveness.

Two studies focused on public awareness-raising campaigns, which inform about women’s rights and legal services available in case of SV, and these were found to be crucial to signal zero tolerance towards SV and to encourage SV survivors to seek justice.Citation43,Citation46 However, two included reviews of moderate quality stated that without adequate protection for abused women against stigma, negative attitudes of the public or avoidance of re-victimisation and traumatisation, legal interventions will be ineffective in reaching out to women and enabling them to receive justice as women will fear to speak up.Citation41,Citation42 Nevertheless, legal services have been found to be essential to counteract the prevailing impunity for SV against refugees and therefore this needs to be addressed in response measures.Citation41,Citation42,Citation50

Education and training

Nine identified studies evaluated effective SV education and training interventions.

A majority of studies either focused on training refugees about SV through awareness-raising campaigns, workshops or through teaching vocational skills in order to decrease SV vulnerability and increase well-being.Citation40Citation41–Citation42,Citation44Citation45–Citation46,Citation50 One study of moderate quality described a multi-component programme in the DRC, which targeted women who survived SV during the conflict. The intervention included advocacy and support for local women’s groups in the organisation of educational opportunities for women and girls and was found to have a positive impact on participants’ well-being and functioning in daily and social tasks.Citation50 A similar intervention of weak quality, implemented in Sierra Leone, targeted women affected by SV during the civil war who had been forced into commercial sex. The intervention aimed to provide knowledge and skills, which would enable these women to find alternative income activities and protect themselves from HIV. Applied strategies to educate these women included music, dance and drama and peer education and were found to be effective in delivering sensitive and important messages. Impact evaluations also showed that the programme was successful in encouraging women to learn new skills and to find alternative livelihoods. HIV infections and mortality decreased among female programme participants.Citation46 Another intervention in Colombia, which aimed to protect and educate women affected by violence including SV, used radio and flyers and trained mobile teams in order to teach women about GBV and SV, to increase the visibility of available services and to confront the cultural acceptance of GBV. Moreover, the cooperation with youth, women’s and social organisations increased the reach of the project.Citation46 Another determining factor for training programmes was their need to be empowering and participatory in order to enable refugees to gain practical skills to solve SV-related safety concerns and to change harmful attitudes that condone SV. A successful intervention, which applied this approach, was conducted by Thompson et al,Citation44 training female refugees in women’s rights and leadership skills, who then passed on their skills to other women through meetings at women’s centres and committees. This allowed women to voice their concerns and issues to decision-makers and enabled them to have an active role in the planning of safety measures within their own camps.Citation44

Three studies also evaluated training on SV response for service providers and humanitarian staff.Citation44,Citation64,Citation66 One moderate quality study, which trialled a multi-media training for health providers in humanitarian settings of four different countries, further succeeded in increasing respect for patients’ rights, case management and treatment.Citation66 However, negative attitudes towards SV survivors were not affected by the training, posing a substantial barrier to the reporting of SV abuse to service providers.Citation66 Another evaluation of health services provided to SV survivors in post-conflict Uganda further showed health personnel should be regularly trained on SV case management as part of their continuous medical education, as one-off trainings in SV response protocols through international agencies were deemed insufficient to ensure appropriate care. Moreover, a greater focus on dealing with adolescent SV survivors was recommended as predominately young girls were found to be sexually abused.Citation64 Within this category only one study, of weak quality,Citation44 pointed out the importance and impact on SV reduction by training both refugees and service providers, in order to increase the understanding and communication between refugees and the professionals working with them, as well as to build an enabling and empowering environment for refugees to find practical and tangible solutions for SV protection. However, while this review identified studies with the objective of transforming harmful gender norms within displaced communities, none of them addressed attitudes and prejudices held by service providers and other professionals, who directly engage with SV survivors.

Discussion

The review demonstrates that SV against refugee women is a complex public health concern requiring a comprehensive, multi-component and culturally sensitive solution. The interventions included were generally not well designed, lacked adequate monitoring and evaluation and were often short-term, preventing a robust impact assessment of interventions on SV long-term or a reliable estimate of the impact interventions have on SV.Citation41–43,Citation45 Few programmers followed the UNHCR guidelines, with the exception of the limited intervention of firewood collection within the safety (prevention) domain and numerous programmes providing counselling within the treatment and counselling (response) domain. Notably, no study evaluated the methods of data collection or interagency information sharing to improve SV prevention and response measures.Citation28–30,Citation43 Humanitarian actors all endorse the need to mainstream SV prevention and response in all programmes to achieve a true impact on the protection of refugee women and girls.Citation28 However, none of the identified studies evaluated the approaches to mainstream SV prevention within broader humanitarian efforts.

Nevertheless, the review identified a number of promising approaches for SV prevention and response, deserving greater attention from humanitarian actors and researchers. These include the active involvement of female refugees in the design, planning and implementation of preventative measures. The involvement of refugees increased empowerment and ownership of implemented programmes and built capacity reducing SV across all included studies.Citation41–44,Citation46 Community engagement strategies also helped to raise awareness about SV, transform harmful gender norms and strengthen accountability within communities to reduce and prevent SV.Citation39,Citation40,Citation41,Citation43Citation44 Citation45–Citation46 Training and education interventions, which engage and teach refugees about SV and the value of gender-equitable norms, are also effective in the prevention and response to SV, according to our review.Citation40Citation41–Citation42,Citation44,Citation46,Citation50 However, few studies targeted service providers directly in contact with survivors.Citation64,Citation66 In addition, very few included studies addressed effective methods of collaboration between organisations, services or even between humanitarian staff and refugees in order to better address safety concerns or to better integrate and improve services for SV survivors.Citation44,Citation46

Although the UNHCR guidelines are important for SV protection, the recommendations have a tendency to position refugees in isolation and disconnected from context, thereby disregarding the often complex dynamics and factors contributing to SV exposure of female refugees. The guidelines also focus on SV perpetrated by strangers rather than intimate partners, even though sexual IPV cases are not uncommon during times of crisis and displacement.Citation14 Risks posed by the host community, including smuggling and trafficking networks, are barely acknowledged and discussed.Citation15 Moreover, abused women face many barriers due to harmful gender biases, stigma, xenophobia and social marginalisation despite protection measures in place.Citation66–68 The existing UNHCR guidelines are more applicable for refugee camp settings.Citation28–30 Refugee populations in transit face constantly changing circumstances and situations on their way to their destination, a logistically challenging research setting, reflected in the paucity of studies in moving populations.

A number of interventions commonly implemented by NGOs or UN agencies in humanitarian settings were excluded from our review due to the limited evidence of effectiveness. These include women’s safe spaces or youth tents, where displaced women and girls can socialise, retreat, build skills and receive information about GBV.Citation23 Other approaches trialled include the establishment of mobile health teams that reach remote displaced populations which would otherwise be marginalised.Citation23

Finally, while UNHCR acknowledges the importance of multi-sectoral and coordinated SV/GBV responses, none of the identified literature in this review examined the potential benefit of effective coordination between humanitarian agencies in a given setting. The UNHCR’s Refugee Coordination Model provides guidance on harmonisation of humanitarian action in regard to GBV protection, which includes the establishment of a Refugee Protection Working Group for the coordination of humanitarian services and the mainstreaming of GBV protection in all sectors.Citation69 The absence of any evaluations of coordinating mechanisms is a significant research gap.

Limitations

This review has some limitations. The focus on English and German publications may have excluded relevant papers only available in other languages. The screening of articles was conducted by a single reviewer which may have resulted in reviewer bias. In addition, the complex context that is the hallmark of conflict and humanitarian crises means that rigorous programme evaluation is particularly challenging. It is noteworthy that only three of the included papers were of strong methodological rigour.

Conclusion

There is limited evidence available for the effectiveness of SV interventions which protect refugees and prevent SV. This review suggests that empowerment, engagement, gender-transformative, culturally sensitive and comprehensive approaches, which build the capacities of the refugee community, provide the most promising strategies to prevent SV. Refugee women cannot rely on short-term SV responses but require a long-term commitment across government and humanitarian sectors to ensure protection for all women. We recommend a greater focus on evaluating and implementing effective models for legal protection, male-engaging strategies, livelihood interventions and training for service providers. Our review provides examples of promising interventions within the domains of engagement and participation as well as training and education, and highlights the significant evidence gaps, which need to be addressed to ensure female refugees enjoy their full rights and can live valuable and healthy lives.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tanya Caulfield for her insight and support during the conduct of this research. They also appreciate the very careful review and comments by the reviewers in the development of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Alison Morgan http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5380-1619

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Global trends forced displacement in 2015. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); 2016.

- EY. The global displacement of populations – from crisis management to long-term solutions [Internet]. EY; 2016 Jul [cited 2017 Sep 10]. Available from: http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY_-_The_global_displacement_of_populations/$FILE/EY-the-global-displacement-of-populations-july-2016.pdf

- European Commission. The EU and the refugee crisis [Internet]. European Union; 2016 Jul [cited 2016 Oct 10]. Available from: http://publications.europa.eu/webpub/com/factsheets/refugee-crisis/en/

- Amnesty International. Tackling the global refugee crisis from shirking to sharing responsibility. London: Amnesty International; 2016.

- Purvis C. Europe’s refugee crisis policy brief. London: International Rescue Committee; 2015.

- Bonewit A. Reception of female refugees and asylum seekers in the EU case study Germany. Brussels: Policy Department C Citizens Rights and Constitutional Affairs European Parliament; 2016.

- Frontex. Western Balkans annual risk analysis. Warsaw: Frontex; 2016.

- Oxfam. Gender analysis: the situation of refugees and migrants in Greece [Internet]. Oxfam; 2016 Aug [cited 2016 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/oxfam_gender_analysis_september2016_webpage.pdf

- Parker S. Hidden crisis: violence against Syrian female refugees. Lancet. 2015;385:2341–2342. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61091-1

- UN Women. Gender-based violence and child protection among Syrian refugees in Jordan, with a focus on early marriage. Amman: UN Women; 2013.

- Nobel Women’s Initiative. Women refugees at risk in Europe. Ottawa: Nobel Women’s Initiative; 2016.

- Ward J, Marsh M. Sexual violence against women and girls in war and its aftermath: realities, responses, and required resources. Brussels: UNPFA; 2006.

- Keygnaert I, Guieu A. What the eye does not see: a critical interpretive synthesis of European Union policies addressing sexual violence in vulnerable migrants. Reprod Health Matters. 2015;23(46):45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.11.002

- Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Watts C. Preventing violence against women and girls in conflict. Lancet. 2014;383(9934):2021–2022. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60964-8

- Keygnaert I, Vettenburg N, Temmerman M. Hidden violence is silent rape: sexual and gender-based violence in refugees, asylum seekers and undocumented migrants in Belgium and the Netherlands. Cult Health Sex. 2012;14(5):505–520. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.671961

- Women’s Refugee Commission. Falling through the cracks: refugee women and girls in Germany and Sweden. New York (NY): Women’s Refugee Commission; 2016.

- European Union. Asylum and migration into the EU in 2015. Luxembourg: Publications Office for the European Union; 2016.

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA. The world report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

- European Institute for Gender Equality. What is gender-based violence? [Internet]. EIGE; 2017 [cited 2017 Sep 10]. Available from: http://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/what-is-gender-based-violence

- UNFPA/WAVE. Defining gender-based violence [Internet]. UNFPA/WAVE; 2017 [cited 2017 Sep 10]. Available from: http://www.health-genderviolence.org/training-programme-for-health-care-providers/facts-on-gbv/defining-gender-based-violence/21

- World Health Organization. Violence prevention the evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Keygnaert I, Dias SF, Degomme O, et al. Sexual and gender-based violence in the European asylum and reception sector: a perpetuum mobile? Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(1):90–96. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku066

- United Nations Population Fund. Adolescent girls in disaster & conflict interventions for improving access to sexual and reproductive health services. New York: UNFPA; 2016.

- Eapen R, Falcione F, Hersh H, et al. Initial assessment report protection risks for women and girls in the European refugee and migrant crisis Greece and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. UNHCR, UNFPA and Women’s Refugee Commission; 2015.

- García-Moreno C. Responding to sexual violence in conflict. Lancet. 2014;383(9934):2023–2024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60963-6

- Hynes M, Cardozo BL. Observations from the CDC: sexual violence against refugee women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(8):819–823. doi: 10.1089/152460900750020847

- Womens Refugee Commission. EU-Turkey agreement failing refugee women and girls. New York (NY): Womens Refugee Commission; 2016.

- UNHCR. Sexual violence against refugees. Guidelines on prevention and response. Geneva: UNHCR; 1995.

- UNHCR. UNHCR handbook for the protection of women and girls. Geneva: UNHCR The UN Refugee Agency; 2008.

- UNHCR. Action against sexual and gender-based violence: an updated strategy. Geneva: UNHCR Division of International Protection; 2011.

- Committee I-AS. Guidelines for integrating gender-based. Violence interventions in humanitarian action: reducing risk, promoting resilience and aiding recovery. Geneva: Inter-Agency Standing Committee; 2015.

- UNFPA. Minimum standards for prevention and response to gender-based violence in emergencies. New York (NY): UNFPA; 2015.

- Asgary R, Emery E, Wong M. Systematic review of prevention and management strategies for the consequences of gender-based violence in refugee settings. Int Health. 2013;5(2):85–91.

- Effective Public Health Practice Project. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies [Internet]. Effective Public Health Practice Project; 2009 [cited 2016 Sep 1]. Available from: http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research [Internet]. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP); 2013 May 31 [cited 2016 Aug 3]. Available from: https://hhs.hud.ac.uk/lqsu/Useful/critap/Qualitative%20Research%20Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Research-Checklist-31.05.13.pdf

- Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:1085. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10

- Shea A, Andersson N, Henry D. A measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR). Supplement to: increasing the demand for childhood vaccination in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9(1):S5. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-9-S1-S5

- Long AF, Godfrey M, Randall T, et al. HCPRDU evaluation tool for mixed methods studies [Internet]. University of Salford Manchester; 2002 [cited 2016 Sep 11]. Available from: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/13070/1/Evaluative_Tool_for_Mixed_Method_Studies.pdf

- Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Kiss L, et al. Working with men to prevent intimate partner violence in a conflict-affected setting: a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial in rural Côte d’Ivoire. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:339. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-339

- Gurman TA, Trappler RM, Acosta A, et al. By seeing with our own eyes, it can remain in our mind: qualitative evaluation findings suggest the ability of participatory video to reduce gender-based violence in conflict-affected settings. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(4):690–701. doi: 10.1093/her/cyu018

- Spangaro J, Adogu C, Ranmuthugala G, et al. What evidence exists for initiatives to reduce risk and incidence of sexual violence in armed conflict and other humanitarian crises? A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062600

- Spangaro J, Adogu C, Zwi AB, et al. Mechanisms underpinning interventions to reduce sexual violence in armed conflict: A realist-informed systematic review. Confl Health. 2015;9(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13031-015-0047-4

- Tappis H, Freeman J, Glass N, et al. Effectiveness of interventions, programs and strategies for gender-based violence prevention in refugee populations: an integrative review. PLoS Curr. 2016:8. doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.3a465b66f9327676d61eb8120eaa5499

- Thompson M, Okumu M, Atema E. Building a web of protection in Darfur. Humanitarian Exchange. 2014;2014(60):24–27.

- Willman AM, Corman C. Sexual and gender-based violence: what is the World Bank doing, and what have we learned? Washington (DC): World Bank; 2013.

- United Population Fund. Programming to end violence against women: 10 case studies. New York (NY): UNFPA; 2006.

- Ray S, Heller L. Peril or protection: the link between livelihoods and gender-based violence in displacement settings. New York (NY): Women’s Refugee Commission; 2009.

- Vu A, Wirtz A, Pham K, et al. Psychometric properties and reliability of the Assessment Screen to Identify Survivors Toolkit for Gender Based Violence (ASIST-GBV): results from humanitarian settings in Ethiopia and Colombia. Confl Health. 2016;10:1. doi: 10.1186/s13031-016-0068-7

- Wirtz A, Glass N, Pham K, et al. Comprehensive development and testing of the ASIST-GBV, a screening tool for responding to gender-based violence among women in humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2016;10(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13031-016-0071-z

- Bolten P. Assessing the impact of the IRC program for survivors of gender based violence in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. International Rescue Committee (IRC) and The Applied Mental Health Research Group; 2009.

- Abdelnour S, Saeed AM. Technologizing humanitarian space: Darfur advocacy and the rape-stove Panacea. Int Pol Soc. 2014;8:145–163. doi: 10.1111/ips.12049

- Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children. Finding trees in the desert: firewood collection and alternatives in Darfur. New York (NY): Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children; 2006.

- CASA Consulting. Evaluation of the Dabaab Firewood project, Kenya. Montreal: UNHCR; 2001.

- Lattu K. To complain or not to complain: still the question. Consultations with humanitarian aid beneficiaries on their perceptions of efforts to prevent and respond to sexual exploitation and abuse. Geneva: Humanitarian Accountability Partnership (HAP); 2008.

- Bass JK, Annan J, McIvor Murray S, et al. Controlled trial of psychotherapy for Congolese survivors of sexual violence. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2182–2191. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211853

- Casey SE. Evaluations of reproductive health programs in humanitarian settings: a systematic review. Confl Health. 2015;9(1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-S1

- Tol WA, Stavrou V, Greene MC, et al. Sexual and gender-based violence in areas of armed conflict: a systematic review of mental health and psychosocial support interventions. Confl Health. 2013;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-7-16

- Hustache S, Moro M-R, Roptin J, et al. Evaluation of psychological support for victims of sexual violence in a conflict setting: results from Brazzaville, Congo. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2009;3:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-3-7

- Doucet D, Denov M. The power of sweet words: local forms of intervention with war-affected women in rural Sierra Leone. Int Soc Work. 2012;55(5):612–628. doi: 10.1177/0020872812447639

- Stark L. Cleansing the wounds of war: an examination of traditional healing, psychosocial health and reintegration in Sierra Leone. Intervention. 2006;4(3):206–218. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0b013e328011a7d2

- Lekskes J, Van Hooren S, De Beus J. Appraisal of psychosocial interventions in Liberia. Intervention. 2007;5(1):18–26. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0b013e3280be5b47

- O’Brien JE, Macy RJ. Culturally specific interventions for female survivors of gender-based violence. Aggress Violent Behav. 2016;31:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2016.07.005

- Gruber J. Silent survivors of SV in conflict and the implications for HIV mitigation: experiences from Eritrea. Afr J AIDS Res. 2005;4(2):69–73. doi: 10.2989/16085900509490344

- Henttonen M, Watts C, Roberts B, et al. Health services for survivors of gender-based violence in northern Uganda: a qualitative study. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(31):122–131. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31353-6

- Horn R. Responses to intimate partner violence in Kakuma refugee camp: refugee interactions with agency systems. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.036

- Smith JR, Ho LS, Langston A, et al. Clinical care for sexual assault survivors multimedia training: a mixed-methods study of effect on healthcare providers’ attitudes, knowledge, confidence, and practice in humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2013;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-7-14

- Govender V, Penn-Kekana L. Gender biases and discrimination: a review of health care interpersonal interactions. Glob Public Health. 2008;3(S1):90–103. doi: 10.1080/17441690801892208

- Chauvin P, Simonnot N, Vanbiervliet F. Access to healthcare in Europe in times of crisis and rising xenophobia, an overview of the situation of people excluded from healthcare systems. Brussels: Doctors of the World; 2013.

- UNHCR. Refugee coordination model (RCM) [Internet]. UNHCR: The UN Refugee Agency [cited 2016 Aug 10]. Available from: https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/60930/refugee-coordination-model-rcm

- Doedens W, Krause S, Matthews J. Assessment of the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) of reproductive health for Sudanese refugees in Chad. New York (NY): UNFPA; 2004.