Abstract

The Minimum Initial Services Package (MISP) for reproductive health has been the minimum standard for reproductive health service provision in humanitarian emergencies since 1995. Assessments of acute humanitarian settings in 2004 and 2005 revealed few MISP services in place and low knowledge of the MISP among humanitarian responders. Just 10 years later, assessments of humanitarian settings in 2013 and 2015 found largely consistent availability of MISP services and high awareness of the MISP as a standard among responders. We describe the multi-pronged strategy undertaken by the Women’s Refugee Commission and other Inter-agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises (IAWG) member agencies to effect systemic improvements in the availability of the MISP at the onset of humanitarian responses. We find that investments in fact-finding missions, awareness-raising, capacity development, policy harmonisation, targeted funding, emergency risk management, and community resilience-building have been critical to facilitating a sea-change in reproductive health responses in acute, large-scale emergencies. Efforts were underpinned by collaborative, inter-agency partnerships in which organisations were committed to working together to achieve shared goals. The strategies, activities, and achievements contain valuable lessons for the health sector, including reproductive health, and other sectors seeking to better integrate emerging or marginalised issues into humanitarian action.

Résumé

Le dispositif minimum d’urgence (DMU) pour la santé génésique est la norme minimale pour la prestation de services de santé génésique dans les situations d’urgence humanitaire depuis 1995. Les évaluations entreprises dans les crises humanitaires aiguës en 2004 et 2005 ont révélé peu de services de DMU en place et de faibles connaissances du DMU parmi les répondants humanitaires. Dix ans après, des évaluations menées dans des contextes humanitaires en 2013 et 2015 ont montré une disponibilité largement constante des services du DMU et une connaissance élevée du DMU comme norme parmi les répondants. Nous décrivons la stratégie multiple entreprise par Women’s Refugee Commission et d’autres institutions membres du Groupe de travail inter-institutions sur la santé génésique en situation de crise (IAWG) pour parvenir à des améliorations systémiques de la disponibilité du DMU au début d’une intervention humanitaire. Nous avons constaté que les investissements dans les missions exploratoires, les activités de sensibilisation, la consolidation des capacités, l’harmonisation des politiques, le financement ciblé, la gestion des risques dans les situations d’urgence et le renforcement de la résilience communautaire ont été essentiels pour faciliter un changement radical dans les réponses de santé génésique lors de situations d’urgence aiguës et à grande échelle. Ces succès contiennent des leçons précieuses pour le secteur de la santé, notamment la santé génésique, et d’autres secteurs souhaitant mieux intégrer des questions émergentes ou marginalisées dans l’action humanitaire.

Resumen

El Paquete de Servicios Iniciales Mínimos (MISP, por sus siglas en inglés) para la Salud Reproductiva ha sido el estándar mínimo para la prestación de servicios de salud reproductiva en emergencias humanitarias desde 1995. Las evaluaciones realizadas en ámbitos humanitarios agudos en 2004 y 2005 revelaron pocos servicios de MISP establecidos y pocos conocimientos del MISP entre respondedores humanitarios. Diez años después, las evaluaciones realizadas en entornos humanitarios en 2013 y 2015 encontraron disponibilidad muy constante de servicios de MISP y un alto nivel de conciencia del MISP como estándar entre respondedores. Describimos la estrategia multifacética aplicada por la Comisión de Mujeres Refugiadas y otras instituciones miembro del Grupo de Trabajo Interinstitucional sobre Salud Reproductiva en Situaciones de Crisis (IAWG, por sus siglas en inglés) para propiciar mejoras sistémicas en la disponibilidad del MISP al inicio de las respuestas humanitarias. Encontramos que inversiones en misiones investigadoras, sensibilización, desarrollo de capacidad, armonización de políticas, financiamiento específico, gestión de riesgos en situaciones de emergencia y desarrollo de la capacidad de recuperación de las comunidades han sido fundamentales para facilitar un cambio radical en las respuestas de salud reproductiva en emergencias agudas de gran escala. Estos logros contienen lecciones valiosas para el sector salud, incluido el de salud reproductiva, y otros sectores que buscan integrar mejor asuntos emergentes o marginados en la acción humanitaria.

Introduction

In April 2004, the Women’s Refugee Commission and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) conducted an assessment of the Minimum Initial Services Package (MISP) for reproductive health () in eastern Chad following the influx of 110,000 Sudanese refugees from Darfur, Sudan. Using the first iteration of inter-agency MISP assessment tools, the team conducted interviews with 53 field staff, undertook 12 health facility assessments, and held 10 focus group discussions with 108 refugee women, men, and youth. The findings were bleak: most humanitarian aid workers had not heard of the MISP, a reproductive health working group had not been established, and few priority reproductive health services were in place.Citation1 One humanitarian aid worker said:

Figure 1. Objectives and priority activities of the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) per the 2010 Inter-agency Field Manual on Reproductive Health in Humanitarian Settings

“We have no staff dedicated to this issue. Our real focus is food, water, and shelter. After that, when we have stabilization, the team will probably focus on that [reproductive health coordination].”Citation1

Eleven years later, an inter-agency team led by the Women’s Refugee Commission travelled to Nepal to assess the implementation of the MISP after the 2015 earthquake. Through 32 focus group discussions, 17 health facility assessments, and 24 key informant interviews with aid workers, the team found remarkable improvement: UNFPA had established a reproductive health working group within days of the emergency, and, despite some gaps and challenges, the services of the MISP were largely in place. Funding and supplies were generally sufficient. Most aid workers interviewed were aware of the MISP as a minimum standard, and representatives from leading agencies, such as Department of Health Services Nepal, UNFPA, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the World Health Organization (WHO), could recite the standard’s objectives and activities.Citation2 How did this change happen – in just over a decade?

Background

The story of the MISP begins in the mid-1990s with the coalescence of three key events. First, the Women’s Refugee Commission published its ground-breaking report on reproductive health in humanitarian settings, Refugee Women and Reproductive Health Care: Reassessing Priorities, which documented few services and high needs in multiple countries.Citation3 Soon after, reproductive health was articulated as a human right with explicit recognition for refugee and internally displaced persons’ rights in the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development Programme of Action.Citation4 During this time, the conflicts in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia brought global attention to wartime sexual violence against women and girls. These events sparked widespread interest in reproductive health in crises, and an international network was launched to advance the issue, the Inter-agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises (IAWG). IAWG tackled a key gap in the field: in 1996, it published the first technical guidance on implementing reproductive health services in humanitarian settings – the field test version of the Reproductive Health for Refugees: An Inter-agency Field Manual (IAFM).Citation5 The IAFM, which was finalised in 1999, included the first guidelines for a minimum set of priority reproductive health services – the MISP – designed to prevent excess morbidity and mortality in humanitarian emergencies, particularly among women and girls.Citation6 To facilitate MISP implementation in the field, IAWG supported the development of 12 packages of reproductive health supplies and medicines, known as the Inter-agency Reproductive Health Kits. Later, in 2010, the IAFM was further revised and additional priority reproductive health activities to the MISP were included ().

The MISP’s odyssey from its initial articulation as a minimum set of priority services in 1995 to widespread implementation in acute, large-scale emergencies by 2015 was facilitated by an innovative strategy led by the Women’s Refugee Commission, UNFPA, International Planned Parenthood Federation’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Programme in Crisis and Post-crisis Settings (SPRINT Initiative), among other active IAWG member agencies. In the early 2000s, the Women’s Refugee Commission spotlighted the challenges in translating the MISP standard into practice. The organisation drew on its theory of change to design and execute, with partners, a strategy to equip humanitarian health actors with comprehensive knowledge of the MISP and to promote supportive policies and sufficient financial resources to support MISP implementation from the onset of an emergency response. The theory of change involved three prongs:

undertaking research and fact-finding missions on MISP implementation in a variety of humanitarian settings to document gaps, challenges, good practices, and progress;

rethinking current approaches to MISP implementation and developing guidance, such as the MISP Distance Learning Module, and other resources to build technical capacity and raise awareness; and,

working to resolve challenges by advocating policy and funding changes, building inter-agency alliances including with donors, and supporting community capacity development and resilience building.

Executing the MISP strategy

Research and fact-finding missions

The Women’s Refugee Commission led MISP assessments in collaboration with IAWG partners following humanitarian emergencies in Chad (2004), Indonesia (2005), Kenya (2008), Haiti (2010), Jordan (2013), and Nepal (2015).Citation1,Citation2,Citation7–10 The assessments were critical in highlighting gaps and tracking progress regarding MISP implementation, as well as bringing attention to the voices and experiences of women and girls in humanitarian settings. Key findings and recommendations were promoted at national and global levels through reports, press releases, news articles, peer-reviewed papers, conference presentations, congressional briefings, and advocacy meetings with humanitarian actors, including representatives of the UN and government agencies. Assessment reports were translated into local languages to support awareness-raising among local staff, and summaries were shared with the displaced communities themselves as part of accountability commitments. The assessment tools, which include questionnaires, checklists, and guidance for focus group discussions, key informant interviews, and health facility assessments, were informed by the Reproductive Health Response in Crises Consortium’sFootnote* field tools developed in 1998, and have since undergone multiple revisions. In 2017, IAWG launched an updated MISP process evaluation toolkit to facilitate a standardised approach to evaluating MISP implementation, ideally within three months of a humanitarian emergency response.Citation11

Resources to improve knowledge and capacity of humanitarian actors

To build capacity at the field level, the Women’s Refugee Commission, in collaboration with other members of the former Reproductive Health Response in Crises Consortium, developed resources to educate relief workers and raise awareness about humanitarian actors’ responsibilities to the MISP as a standard of care in new emergencies. They developed a series of technical manuals on reproductive health to support MISP implementation, including on emergency contraception, emergency obstetric and newborn care, HIV, and other sexually transmitted infections.Citation12–15

To more directly address the acute gap in humanitarian actors’ knowledge of the MISP, the Women’s Refugee Commission led the development of a self-instructional distance learning module on the MISP in 2007.Citation16 This module has been instrumental in raising awareness among and developing the capacity of aid workers on the standard. The MISP module is available online and in hard copy, and has been translated into ten languages, enabling wide reach. It provides a user-friendly perspective on the MISP in the context of an acute emergency and provides practical guidance and tools to humanitarian staff, including fundraising templates and information about how to order the Inter-agency Reproductive Health Kits. The inclusion of a post-test and certification incentivised aid workers to complete the module. The Women’s Refugee Commission and IAWG colleagues have since worked to integrate the module into the curricula of numerous complex emergency courses and university programmes around the world as another avenue to promote capacity development and awareness-raising.

The next major catalyst in building field-level capacity on the MISP came with the launch of International Planned Parenthood Federation’s SPRINT Initiative in 2007. With support from the Australian government, the SPRINT Initiative and UNFPA developed a comprehensive training curriculum on how to coordinate and implement the MISP in an acute crisis response.Citation17 The SPRINT training has been rolled out across multiple regions, and UNFPA has used the training to strengthen national capacity. While the MISP module and SPRINT training helped augment the skills and knowledge of humanitarian responders, more attention was needed to build resilience at the community level. With support from UNFPA, the Women’s Refugee Commission developed a training curriculum on reproductive health and gender to help communities prepare for and better withstand disasters.Citation18 Participants develop action agendas to improve MISP preparedness within the community, such as mapping the location of health facilities and safe spaces for boys and girls.

As awareness of and attention to the MISP grew, assessments found ongoing gaps in the clinical skills of health providers to deliver certain MISP services. In response, IAWG developed the Training Partnership Initiative, supported by the US government, which works to institutionalise refresher trainings for health providers on the clinical components of the MISP in crisis-prone countries with partners in low- and middle-income countries. Four clinical modules have been developed: clinical care for survivors of sexual violence, manual vacuum aspiration, vacuum extraction, and emergency obstetric and newborn care.

In this way, the Women’s Refugee Commission and IAWG partners engaged in an iterative process in which they identified key gaps or challenges in MISP implementation, developed and disseminated tools and resources to address them, and conducted assessments to track progress and examine additional gaps. To better engage adolescents from the onset of humanitarian emergencies, for example, Save the Children and UNFPA developed an adolescent toolkit that complements the IAFM.Citation19 To support community information, education and communication about the MISP, the Women’s Refugee Commission developed a package of universal, adaptable pictorial templates on the benefits of seeking care after sexual violence and signs of complications from pregnancy and childbirth, which can be easily modified to reflect the local context. Provision of newborn care has long been neglected in humanitarian response, and Save the Children and UNICEF created a field guide on newborn health, also to complement the IAFM.Citation20

Policy and funding advocacy

The Women’s Refugee Commission and IAWG partners successfully advocated for the integration of the MISP into key humanitarian guidelines and policies as part of efforts to systematically ensure inclusion of the MISP in humanitarian health responses and to promote consistency across inter-agency guidance. An important initial milestone was the inclusion of the MISP into the 2000 version of The Sphere Handbook, the most widely embraced set of common humanitarian principles and standards.Citation21 The MISP was elevated to a Sphere standard in the 2004 revision of the handbook.Citation22 Institutionalisation of the MISP gained momentum as it was integrated into Inter-agency Standing Committee (IASC) guidelines on gender-based violence,Citation23 gender,Citation24 and HIV.Citation25 From 2006 to 2010, the advocacy partners to Columbia University’s Reproductive Health Access, Information, and Services in Emergencies (RAISE) Initiative – which included JSI Training and Research Institute, Marie Stopes International, and the Women’s Refugee Commission – led many of the efforts to facilitate an enabling policy and funding environment for reproductive health services in humanitarian settings. They successfully advocated for inclusion of the MISP and/or comprehensive reproductive health services into 4 existing and 30 new UN and inter-agency policies, standards, and technical guidance, such as the IASC Global Health Cluster guidanceCitation26 and the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) Life-saving Criteria and Sectoral Activities Guidelines. Through collective action with other working groups, the UN Security Council further adopted Resolutions 1325, 1820, 1888, 1889, and 1960 on Women, Peace, and Security that explicitly referred to the need to ensure women and girls’ access to reproductive health services in conflict settings. IAWG also promoted awareness of the MISP through the development and wide dissemination of inter-agency statements on the importance of MISP implementation at the onset of humanitarian emergencies, such as post-earthquake in Haiti and Nepal. As of 2017, IAWG has further hosted 17 annual meetings around the world to share research, policy, and programming findings, obtain collegial feedback, and to establish networking opportunities to support new ideas and collaborative initiatives. These meetings have served as important fora to develop momentum in pursuit of a common advocacy agenda.

On the funding side, a number of private and government donors have been instrumental to the advancement of the MISP. From 2003 to 2009, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation explicitly supported the Women’s Refugee Commission’s strategic plan to ensure the MISP as a systemic part of humanitarian response. The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation also funded the Women’s Refugee Commission’s MISP initiative and wider IAWG research and advocacy, while an anonymous donor currently supports the IAWG.

A key donor in advancing the MISP at the field and global levels has been Australia’s foreign aid programme, which has funded the SPRINT Initiative for a decade. It has provided important financial contributions to support reproductive health and disaster risk reduction initiatives, inter-agency MISP assessments, and a comprehensive package of MISP assessment toolsCitation11 developed by IAWG members. The US Government’s Bureau for Population Refugees and Migration and the US Agency for International Development’s Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance have additionally supported MISP efforts through the IAWG Training Partnership Initiative.

Regarding implementation, a variety of donors have committed to support the MISP at the onset of a crisis response as reflected in the financial support to emergencies in Jordan and Nepal. According to key informants, donors that supported MISP implementation in both Jordan and Nepal include CERF, governments, UN agencies, and several large nongovernmental organisations, while the Flash Appeal and Consolidated Appeals Process also included MISP activities in Nepal.Citation2,Citation10 Most importantly, key informants acknowledged that funding was sufficient for the emergency response, though some reported challenges in financial support for the transition from MISP to more comprehensive reproductive health services.Citation2

Emergency and disaster risk management

While early efforts to advance the MISP focused largely on policy change, donor support, and the development of technical resources, in recent years, IAWG partners have given more attention to the role of reproductive health in emergency and disaster risk management, including building community resilience. At the national level, the SPRINT Initiative – the first national capacity building initiative focused on the MISP including disaster risk reduction – has catalysed the field. Launched in 2007, SPRINT has grown from its original pilot in the East, South East Asia, and Pacific region, and is now part of International Planned Parenthood Federation’s core humanitarian work, with operations in select countries across the Asia, Pacific, Africa, and the Middle East.

In 2010, the Women’s Refugee Commission established an inter-agency working group on disaster risk reduction. With support from the WHO, this became an official reproductive health working group within the UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) Thematic Platform for Health. Informed by the Hyogo Framework for Action, the working group developed and widely disseminated a policy brief on integrating the MISP into national emergency and disaster risk managementCitation27 and developed a complementary monitoring tool.Citation28 The Women’s Refugee Commission and other IAWG members, including WHO, UNFPA, and the SPRINT Initiative, successfully advocated for the integration of reproductive health in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030.Citation29 The Women’s Refugee Commission captured several unique case studies on the integration of reproductive health into emergency and disaster risk management for health, such as a regional (18 country) MISP readiness assessment undertaken by multiple stakeholders in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia region.Citation30

Outcomes

The coordinated, comprehensive efforts of the Women’s Refugee Commission and IAWG partners such as UNFPA, the SPRINT Initiative, the RAISE Initiative, among others, have contributed significantly to the consistent advancement of the MISP in humanitarian settings. The capacity of humanitarian aid workers to coordinate and implement the MISP has improved: as of May 2017, more than 5000 people around the world have received certification in the MISP distance learning module, and almost 2 dozen complex emergency and university courses have included the MISP module in their curricula. More than 6000 individuals from 50+ countries have undertaken SPRINT’s MISP training, which has been critical to raising awareness and strengthening national and local capacities. The 2012–2014 IAWG Global Evaluation found a marked increase in organisational capacity to implement the MISP, with 84% of the institutions surveyed reportedly addressing the MISP.Citation31 Indeed, the most recent IAWG Global Evaluation revealed strong progress regarding MISP implementation since 2004, although gaps remain across all objectives.Citation32

At the policy level, the overwhelming majority of relevant health and protection-related global humanitarian guidance documents are harmonised with the 2010 IAFM version of the MISP.Citation24–26,Citation33–35 Clear improvements have been achieved at the agency level: the 2012–2014 IAWG Global Evaluation found that 68% of 82 humanitarian and development institutions surveyed reported having an internal policy or guideline on reproductive health in humanitarian settings, as compared to 43% of the 30 institutions surveyed in the 2002–2004 IAWG Global Evaluation.Citation31

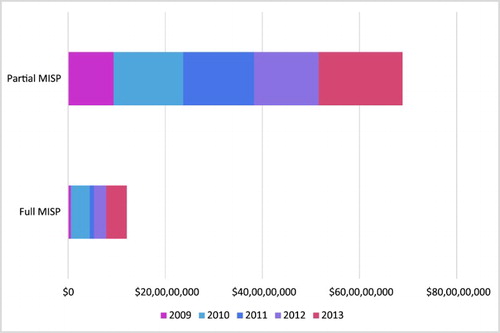

In terms of funding, aid agencies have submitted an increasing number of health and protection proposals appealing to implement MISP-related activities as part of financial appeals processes, and funding received for these activities has also increased.Citation36 For example, proposals submitted to humanitarian appeals that included full or partial MISP implementation saw an average annual increase of 39.5% and 2.4%, from 2009 to 2013, respectively.Citation36 In addition, we re-examined the funding-related data from the 2012–2014 IAWG Global Evaluation, and found that US$120.7 million was received for proposals that noted full MISP implementation and US$688.6 million for proposals that included partial MISP implementation over this five-year time period (). It is unsurprising that in terms of absolute dollar amounts, full MISP implementation proposals received far less funding than those that noted partial MISP implementation, given that more proposals contained activities that were partially MISP-related, than those that explicitly noted implementing the MISP in full. Overall, during this period, all relevant reproductive health proposals received a total of US$1,592.9 million.

Proposals that sought to implement the MISP in full were 42.9% funded, and those that noted partial MISP implementation were 44.1% funded over the five-year period. This trend is similar to the proportion of all relevant reproductive health-related health and protection proposals that were funded over the same period, which was 45.6%.Citation36

When examining proposals addressing partial MISP implementation in depth, MISP-related maternal newborn health activities were funded at 50.4% of requests to implement this reproductive health component, while family planning received 59.2% of requested funding. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections were funded at 47.6%, reproductive health-related gender-based violence at 35.0%, and general reproductive healthFootnote† at 57.6%.Footnote‡ While family planning appears to have been most funded, the absolute number of proposals that mentioned MISP-related family planning activities was much less (171) compared to those that included maternal newborn health (565) or gender-based violence (736) activities. Overall trends from all relevant reproductive health-related health and protection proposals – not just those limited to the MISP – from the 2012–2014 IAWG Global Evaluation further showed that maternal newborn health was most commonly appealed for and funded as a component of reproductive health during the five-year period.Citation36

Regarding implementation of the MISP, the two most recent MISP assessments in Jordan (2013) and Nepal (2015) showed high levels of commitment by hosting governments, UN agencies particularly UNFPA, donors, and non-governmental organisations to establish MISP services.Citation2,Citation10 In both settings, a dedicated lead agency to support MISP implementation was in place, funding and supplies were largely sufficient, and skilled health workers gave attention to all components of the MISP. Key informants identified the factors that they perceived facilitated MISP implementation in their setting: a lead reproductive health agency, staff capacity to support the MISP, sufficient funding, and adequate supplies. Additional facilitating factors included pre-crisis investments in disaster risk management for health including training staff on the MISP, Ministry of Health protocols (particularly for sexual violence) aligned to support the MISP, and the pre-positioning (even virtually) of supplies.Citation2

Looking ahead

Investments in the multi-pronged strategy to improve policy, funding, and humanitarian actors’ knowledge and capacity to implement the MISP were steadily successful over 20 years of facilitating systematic progress in MISP implementation in acute, large-scale emergencies. Key to these efforts were collaborative, inter-agency partnerships in which agencies were committed to working together to achieve shared goals. In addition, the evidence from the MISP assessment in Nepal highlights the value of investing in the integration of the MISP into disaster risk management for health, and strengthening community resilience. The achievements made through this comprehensive strategy contain important lessons for actors seeking to better integrate other areas into humanitarian response, such as efforts related to persons with disabilities and persons with diverse sexual and gender identities.

The story of the MISP is far from over. In fact, new guidance on the MISP is underway as IAWG has made fundamental changes to the MISP chapter of the 2018 revision of the IAFM by adding a new objective and priority activities. These include making available: voluntary contraception including long-acting reversible contraceptive methods to meet demand, expanded maternal and newborn care, and expanded HIV prevention and care. In addition, the MISP chapter notes the need to address safe abortion care to the full extent of the law, including as part of clinical care for survivors of sexual violence.Citation37

While the addition of more activities challenges the construction of the MISP as a set of limited priority activities, the aim is to ensure the availability of reproductive health services that are life-saving in the short-term and feasible at the onset of all humanitarian responses. It is possible that the attention of governments and donors, and the infusion of funding and human resources at the onset of humanitarian response, can set the stage for comprehensive services as the situation stabilises. This has important potential to “build back better”. These additional priority activities also compel humanitarian actors to enhance coordination, given that no one agency is likely to have capacity to support all services.

While significant advancements to the MISP have been achieved, much more effort is needed to ensure its systematic implementation and uptake in an acute crisis. Indeed, service utilisation does not inherently follow service availability. Neither does availability imply equitable coverage. Aid actors must bring the services of the MISP to the attention of the population, as they did in Nepal, to facilitate uptake through community outreach and information about the benefits and location of services by radio, television, social media, and other methods appropriate to the context. Crisis-affected communities, including often marginalised groups such as adolescents, persons with disabilities, and persons with diverse sexual and gender identities, need to be more consistently engaged in planning, implementing, supporting, and evaluating MISP services. Men and boys, too, have reproductive health needs that require better attention, such as HIV and other sexually transmitted infection-related care, as well as sensitised post-sexual violence care. Indeed, systematic provision of clinical care for all survivors of sexual violence is an ongoing gap in humanitarian health service provision, which appears to be in part influenced by a dearth of pre-existing protocols and services. Many reproductive health issues are culturally sensitive, requiring a nuanced and thoughtful approach, and emerging areas such as reproductive health for very young adolescents, sexual violence against men, boys, and persons with diverse sexual orientation and gender identities, as well as comprehensive abortion care may require new strategies and approaches.

For ethical reasons as well as more effective implementation, it is critical to build on existing local and national capacities. If the capacity exists to support comprehensive service provision from the onset of a crisis, then that should be the aim. However, in many emergencies, this is not possible, and it is thus important to plan to transition from the MISP to comprehensive services as soon as possible. The timely transition to comprehensive services has long been a gap in MISP implementation, and though this objective has been strengthened using the health system building blocks approach in the revised IAFM, more consistent attention is needed. The current political climate in the United States also threatens funding and support for reproductive health in crises, although some new donors have expressed interest in offsetting financial shortcomings. At the policy level, IAWG and other actors must continue to ensure that the 2018 version of the IAFM and the MISP are consistent in all new revisions of humanitarian guidance, such as the upcoming Sphere and IASC gender handbook revisions, and in any new “packages of services” supported by the health cluster in humanitarian emergencies.

A number of initiatives are underway to continue to support implementation and uptake of good quality MISP services. For example, IAWG plans to update all MISP resources to align with the revised 2018 IAFM, such as the MISP distance learning module, and to widely disseminate the revised IAFM, including through field orientation sessions. The global IAWG will also support regional IAWGs to effectively disseminate the revised IAFM and other related resources and tools, such as the Newborn Health in Humanitarian Settings: Field Guide and the IAWG MISP Clinical Refresher Training Modules. In addition, IAWG has recently finalised a comprehensive package of MISP assessment tools supported by the SPRINT Initiative, which are available on the IAWG website. The tools can be used by national and local actors to conduct MISP assessments and advocate for attention to reproductive health needs in all sudden onset emergencies, including smaller and less visible crises. The IAWG also plans to pilot and widely disseminate an existing “MISP to comprehensive reproductive health care” toolkit to catalyse participatory planning among national stakeholders to integrate comprehensive reproductive health into health system reconstruction efforts. To better address climate-induced disasters, IAWG members will continue to build capacity at global, national, and community levels to integrate reproductive health in disaster risk management planning. As additional barriers to MISP implementation and utilisation are identified, the IAWG will develop solutions to address them as part of the network’s comprehensive campaign to ensure that all women, girls, men, and boys surviving crises and displacement realise their right to good quality reproductive health care.

Acronyms

| ARV: | = | Antiretrovirals |

| CERF: | = | Central Emergency Response Fund |

| IAFM: | = | Inter-agency Field Manual on Reproductive Health in Humanitarian Settings |

| IASC: | = | Inter-agency Standing Committee |

| IAWG: | = | Inter-agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises |

| MISP: | = | Minimum Initial Service Package for Reproductive Health |

| RAISE: | = | Reproductive Health Access, Information and Services in Emergencies |

| SPRINT: | = | Sexual and Reproductive Health Programme in Crisis and Post-Crisis Situations |

| UN: | = | United Nations |

| UNFPA: | = | United Nations Population Fund |

| UNICEF: | = | United Nations Children’s Fund |

| UNIDSR: | = | United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction |

| WHO: | = | World Health Organization |

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to our donors and IAWG partners, as well as the local organizations and crisis-affected communities with whom we have worked over the years to advance the MISP.

Notes

* The members of the Reproductive Health Response in Crises Consortium included the American Refugee Committee, CARE, Columbia University, International Rescue Committee, JSI Research and Training Institute, Marie Stopes International, and the Women’s Refugee Commission. All members are active in IAWG.

† Per the original 2012–2014 IAWG Global Evaluation article, “general reproductive health” includes: reproductive health coordination, procurement of Reproductive Health Kits and supplies, planning for comprehensive reproductive health, disaster risk reduction, menstrual hygiene, and dignity kits, among other activities.

‡ Based on the methodology of the original 2012–2014 IAWG Global Evaluation study, funding requested and received have been weighted by the number of reproductive health components encompassed in each proposal. Hence, similar limitations and assumptions of proportional allocation of funds per mentioned reproductive health component, apply.

References

- Women’s Refugee Commission (formerly Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children), United Nations Population Fund. Lifesaving Reproductive Health Care: Ignored and Neglected, Assessment of the Minimum Initial Services Package (MISP) of Reproductive Health for Sudanese Refugees in Chad [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/srh-2016/resources/60-lifesaving-reproductive-health-care-in-chad-ignored-and-neglected

- Women’s Refugee Commission. Evaluation of the MISP for Reproductive Health Services in Post- earthquake Nepal [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/srh-2016/resources/1253-misp-nepal-20

- Women’s Refugee Commission (formerly Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children). Refugee Women and Reproductive Health Care: Reassessing Priorities. 1994 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/resources/document/583-refugee-women-and-reproductive-health-care-reassessing-priorities

- UN Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, with support from UNFPA. Report of the International Conference on Population and Development. 1994.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations: An Inter-agency Field Manual, Field-Test Version. 1996.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations: An Inter-agency Field Manual [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/publications/operations/3bc6ed6fa/reproductive-health-refugee-situations-inter-agency-field-manual-unhcrwhounfpa.html

- Women’s Refugee Commission (formerly Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children). Reproductive Health Priorities in an Emergency: Assessment of the Minimum Initial Service Package in Tsunami-affected Areas of Indonesia. 2005.

- Women’s Refugee Commission (formerly Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children). Reproductive Health Coordination Gap, Services Ad hoc: Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) Assessment in Kenya [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/images/zdocs/ken_misp.pdf

- CARE, International Planned Parenthood Federation, Save the Children, Women’s Refugee Commission. Priority Reproductive Health Activities in Haiti: An inter-agency MISP assessment conducted by CARE, International Planned Parenthood Federation, Save the Children and Women’s Refugee Commission [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/resources/document/696-priority-reproductive-health-activities-in-haiti-2011

- Krause S, Williams H, Onyango MA, et al. Reproductive health services for Syrian refugees in Zaatri Camp and Irbid City, Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan: an evaluation of the Minimum Initial Services Package. Confl Health. 2015;9(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-S4

- Inter-agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises. MISP Process Evaluation Tools [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 October 19]. Available from: http://iawg.net/resource/misp-process-evaluation-tools-2017/

- Reproductive Health Response in Crises Consortium. Emergency Contraception for Conflict-Affected Settings: A Reproductive Health Distance Learning Module [Internet]. 2004. Available from: http://iawg.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/8D85E33AB589277AC1256FF00039AAAC-WCRWC_may_2004.pdf

- Reproductive Health Response in Crises Consortium. Field-friendly Guide to Integrate Emergency Obstetric Care in Humanitarian Programs. 2005.

- Reproductive Health Response in Crises Consortium. Guidelines for the Care of Sexually Transmitted Infections in Conflict-affected Settings [Internet]. Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children. 2004 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/resources/document/602-guidelines-for-the-care-of-sexually-transmitted-infections-in-conflict-affected-settings

- Reproductive Health Response in Crises Consortium. HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control: A short course for humanitarian workers: Facilitator’s Manual [Internet]. Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children. 2004 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/resources/document/603-hivaids-prevention-and-control-a-short-course-for-humanitarian-workers-facilitators-manual

- Women’s Refugee Commission. Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for reproductive health in crisis situations: a distance learning module. 2007.

- International Planned Parenthood Federation, United Nations Population Fund. SPRINT training on the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for sexual and reproductive health in crises: a course for coordination teams. 2013.

- Women’s Refugee Commission. Community Preparedness for Reproductive Health and Gender, A Facilitator’s Kit for a 3-day Training Curriculum [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/resources/document/1048-drr-community-preparedness-curriculum

- United Nations Population Fund, Save the Children. Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/adolescent-sexual-and-reproductive-health-toolkit-humanitarian-settings

- Save the Children, United Nations Children’s Fund. Newborn health in humanitarian settings: field guide. 2016.

- The Sphere Project. Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response. 2000.

- The Sphere Project. Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response. 2004.

- Inter-agency Standing Committee. Guidelines for Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings Focusing on Prevention of and Response to Sexual Violence in Emergencies [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/453492294.pdf

- Inter-agency Standing Committee. Women, Girls, Boys and Men: Different Needs – Equal Opportunities, Inter-agency Standing Committee Gender Handbook in Humanitarian Action [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/legacy_files/IASC%20Gender%20Handbook%20%28Feb%202007%29.pdf

- Inter-agency Standing Committee. Guidelines for Addressing HIV in Humanitarian Settings [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/legacy_files/IASC_HIV_Guidelines_2010_En.pdf

- World Health Organization. Health Cluster Guide: A practical guide for country-level implementation of the Health Cluster [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/health-cluster/resources/publications/hc-guide/en/

- World Health Organization. Integrating sexual and reproductive health into health emergency and disaster risk management [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/preparedness/SRH_policybrief/en/

- UNISDR Reproductive Health Working Group. Integrating Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) into emergency and disaster risk management for health: country assessment and monitoring tool. 2017.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: http://www.unisdr.org/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf

- Women’s Refugee Commission. Building National Resilience for Sexual and Reproductive Health: Learning from Current Experiences. 2016 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/images/zdocs/Building-Resilience-for-SRH-Case-Study.pdf

- Tran N-T, Dawson A, Meyers J, et al. Developing institutional capacity for reproductive health in humanitarian settings: a descriptive study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0137412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137412

- Chynoweth SK. Advancing reproductive health on the humanitarian agenda: the 2012–2014 global review. Confl Health. 2015;9(Suppl 1):I1. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-I1

- The Sphere Project. Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response. 2011.

- World Health Organization. Health Resource Availability Mapping System (HeRAMS). 2009.

- Inter-agency Standing Committee. Guidelines for Integrating Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action: Reducing risk, promoting resilience and aiding recovery [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://gbvguidelines.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/2015-IASC-Gender-based-Violence-Guidelines_lo-res.pdf

- Tanabe M, Schaus K, Rastogi S, et al. Tracking humanitarian funding for reproductive health: a systematic analysis of health and protection proposals from 2002–2013. Confl Health. 2015;9(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-S2

- Inter-agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises. Inter-agency field manual on sexual and reproductive health in humanitarian settings. 2017.