Abstract

Unsafe abortion is responsible for at least 9% of all maternal deaths worldwide; however, in humanitarian emergencies where health systems are weak and reproductive health services are often unavailable or disrupted, this figure is higher. In Puntland, Somalia, Save the Children International (SCI) implemented postabortion care (PAC) services to address the issue of high maternal morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortion. Abortion is explicitly permitted by Somali law to save the life of a woman, but remains a sensitive topic due to religious and social conservatism that exists in the region. Using a multipronged approach focusing on capacity building, assurance of supplies and infrastructure, and community collaboration and mobilisation, the demand for PAC services increased as did the proportion of women who adopted a method of family planning post-abortion. From January 2013 to December 2015, a total of 1111 clients received PAC services at the four SCI-supported health facilities. The number of PAC clients increased from a monthly average of 20 in 2013 to 38 in 2015. During the same period, 98% (1090) of PAC clients were counselled for postabortion contraception, of which 955 (88%) accepted a contraceptive method before leaving the facility, with 30% opting for long-acting reversible contraception. These results show that comprehensive PAC services can be implemented in politically unstable, culturally conservative settings where abortion and modern contraception are sensitive and stigmatised matters among communities, health workers, and policy makers. However, like all humanitarian settings, large unmet needs exist for PAC services in Somalia.

Résumé

Les avortements à risque sont responsables d’au moins 9% des décès maternels dans le monde ; néanmoins, ce chiffre est plus élevé dans les situations d’urgence humanitaire, où les systèmes de santé sont faibles et les services de santé génésique souvent indisponibles ou désorganisés. Au Puntland, en Somalie, Save the Children International (SCI) a mis en œuvre des services de soins post-avortement pour traiter le problème des taux élevés de mortalité et de morbidité maternelles dus aux avortements à risque. L’avortement est explicitement autorisé par le droit somalien pour sauver la vie de la femme, mais demeure une question sensible en raison du conservatisme religieux et social qui règne dans la région. Moyennant une approche plurielle centrée sur le renforcement des capacités, la garantie des approvisionnements et de l’infrastructure, ainsi que la collaboration et la mobilisation de la communauté, la demande de services de soins post-avortement a augmenté, tout comme la proportion de femmes ayant adopté une méthode de planification familiale après l’avortement. De janvier 2013 à décembre 2015, un total de 1111 clientes ont reçu des services de soins post-avortement dans les quatre centres de santé soutenus par SCI. Le nombre de clientes pour des soins de cette nature a augmenté d’une moyenne mensuelle de 20 en 2013 à 38 en 2015. Pendant la même période, 98% (1090) de ces clientes ont été conseillées pour une contraception post-avortement, dont 955 (88%) ont accepté une méthode contraceptive avant de quitter le centre, avec 30% d’entre elles optant pour une contraception réversible de longue durée. Ces résultats montrent que des services complets de soins post-avortement peuvent être mis en œuvre dans des environnements politiquement instables et culturellement conservateurs, où l’avortement et la contraception moderne sont des questions sensibles et réprouvées parmi les communautés, les agents de santé et les décideurs. Néanmoins, comme dans toutes les situations de crise humanitaire, de vastes besoins insatisfaits demeurent pour des services de soins post-avortement en Somalie.

Resumen

El aborto inseguro es responsable de por lo menos el 9% de todas las muertes maternas del mundo; sin embargo, en emergencias humanitarias donde los sistemas de salud son débiles y los servicios de salud reproductiva a menudo no están disponibles o son interrumpidos, esta cifra es más alta. En Puntland, Somalia, Save the Children International implementó servicios de atención postaborto (APA) para tratar el problema de alta morbimortalidad materna debido al aborto inseguro. El aborto es permitido por la ley somalí explícitamente para salvar la vida de la mujer, pero continúa siendo un tema delicado debido al conservadurismo religioso y social que existe en la región. Utilizando un enfoque multifacético centrado en el desarrollo de capacidad, garantía de insumos e infraestructura, y colaboración y movilización comunitarias, la demanda de servicios de APA aumentó, al igual que el porcentaje de mujeres que adoptaron un método de planificación familiar postaborto. Desde enero de 2013 hasta diciembre de 2015, un total de 1111 usuarias recibieron servicios de APA en las cuatro unidades de salud apoyadas por SCI. El número de usuarias de APA aumentó de un promedio mensual de 20 en 2013, a 38 en 2015. Durante el mismo período, el 98% (1090) de las usuarias de APA recibieron consejería sobre anticoncepción postaborto, de las cuales 955 (88%) aceptaron un método anticonceptivo antes de dejar la unidad de salud, y el 30% optó por un método anticonceptivo reversible de acción prolongada (LARC). Estos resultados muestran que los servicios integrales de APA pueden ser implementados en entornos políticamente inestables y culturalmente conservadores, donde el aborto y la anticoncepción moderna son temas delicados y estigmatizados por comunidades, trabajadores de salud y formuladores de políticas. Sin embargo, como en todos los entornos humanitarios, existen grandes necesidades insatisfechas de servicios de APA en Somalia.

Introduction

Globally, 830 women die every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and child birth; of these, almost all (99%) occur in low- and middle-income countries.Citation1 Over two thirds of maternal deaths result from direct obstetric causes, such as haemorrhage, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, sepsis, abortion, and other direct causes.Citation2 In sub-Saharan Africa, more than 97% of abortions received by women are unsafe and unsafe abortion is responsible for at least 9% of all maternal deaths with over 1.6 million women hospitalised for complications due to these dangerous procedures each year.Citation3–5 Despite being recognised as a significant contributor to maternal deaths, in 2008, an estimated 3 million women with complications from unsafe abortion were left without care in low- and middle-income countries, often at a huge cost to individuals, communities, and the health system.Citation3,Citation6,Citation7

Postabortion care (PAC) refers to a package of health facility-based services for complications of spontaneous or induced abortion. The three-component model, attributed to USAID, includes emergency treatment for complications of abortion, including infection, sepsis, haemorrhage, shock, and reproductive tract injuries; family planning counselling and provision of contraceptive methods for the prevention of further unplanned or mistimed pregnancies that may lead to repeat induced abortions; and community awareness and mobilisation around the critical nature of PAC, allowing for important linkages to other reproductive health (RH) services, including gender-based violence and HIV, which are essential to internally displaced person (IDP) populations in humanitarian crises. Although it is known that PAC services can prevent morbidity and mortality from abortion-related complications, access to these lifesaving services is widely unavailable to women across sub-Saharan Africa.Citation8 Barriers to access include, but are not limited to, restrictive laws and policies, a lack of understanding of these laws and policies by providers and community members, stigma associated with abortion, negative attitudes of service providers, lack of trained medical personnel, restriction of services to higher level and cadre of care, inadequate supplies and equipment, and lack of integration into the primary health care system.Citation8,Citation9

The situation is worsened in humanitarian settings, where access to general RH services for crisis-affected women is severely limited, often due to non-existent or fractured infrastructure.Citation10–13 The need for RH services is high in conflicts, while the availability is low.Citation14 Although significant progress has been made in improving access to RH services for women in humanitarian settings since the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994, gaps in RH services continue to exist for key interventions, such as lifesaving PAC services.Citation15–17 Improving access to PAC, family planning (FP), and other RH services to women in humanitarian settings is a key strategy for preventing maternal mortality and morbidity.

A programmatic evidence base for the feasibility, effectiveness, and quality of PAC services in fragile settings is slim.Citation16 This paper documents strategies, results, and lessons learned from Save the Children International’s (SCI) PAC implementation in Puntland, Somalia. Somali law explicitly allows abortion to save a woman’s life, which allows for PAC. In addition to the restrictive legal environment, Puntland presents a challenging humanitarian context that is coupled with religious and social conservatism that further elevates barriers to improving the availability and accessibility of quality PAC services. This study makes an important contribution to the existing evidence base for the implementation of PAC services in a challenging humanitarian context.

Background

The Somali population is predominantly young, rural, and nomadic. Among the 12.3 million people living in Somalia, approximately 9% are internally displaced.Citation18 Somalia has continued to endure chronic conflict for more than two decades since the last central government collapsed. The existing government capacity and systems are weak and access to basic services, including health care, is limited. Somalia has one of the highest total fertility rates in the world (TFR = 6.4) coupled with very low modern contraceptive prevalence (mCPR = 1%), high unmet need for family planning (29.2%), and limited access to PAC.Citation19,Citation20 With a 1 in 18 lifetime risk of a woman dying during pregnancy or childbirth, it remains one of the few places with the highest risk for mothers.Citation21

Somalia is a culturally and religiously conservative country. Nearly the entirety of the population (99.9%) is Muslim. It is a pronatalist nation, where children are highly desired for social status and economic benefits.

Puntland, Somalia, is one of the areas where SCI has implemented the FP and PAC Initiative. Puntland is relatively stable and has a well-functioning, semi-autonomous government system, but limited resources and a lack of trained health workers impede the government’s capacity to deliver essential basic social services, including health. Due to ongoing conflict in South Central Somalia, the influx of internally displaced persons (IDPs) into Puntland has increased, putting additional pressure on an already fragile health system. It is estimated that about 130,000 IDPs currently reside in Puntland.Citation22

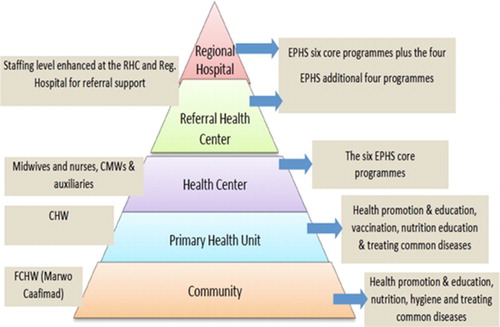

In 2010, the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Puntland articulated a Reproductive Health Strategy which included FP and PAC services among its priorities. This strategy is yet to be fully implemented, leaving the majority of women without access to essential RH services. Save the Children began implementing the FP and PAC Initiative in collaboration with the MOH in July 2012 for a three-year period, consistent with funding. The overall aim of the project was focused on improving access to FP and PAC to women residing in remote communities in the Karkaar region of Puntland, Somalia. The Somali government is committed to bolstering RH services and, in 2009, launched the Essential Package of Health Services, which is a framework to deliver primary health care services in the areas of maternal, reproductive, and neonatal and child health; communicable disease; surveillance and control, including water and sanitation promotion; first-aid and care of critically ill and injured; treatment of common illnesses and HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and tuberculosis. PAC is viewed by the government and MOH as an essential lifesaving procedure. The cadre of skilled staff aligns with the package of health services provided at the various levels of health facilities and the referral system functions as a pyramid, with referrals beginning at the community level and extending to the regional hospital (). Prior to the commencement of the FP-PAC project, there were no FP and PAC services available to the local population; PAC was restricted to dilatation and curettage (D&C) only at some regional hospitals. Rural districts are located at an average of 450 kilometres from the regional hospital, with difficult terrain, poor communication and weak transportation infrastructure, thus accessing emergency PAC services was often impossible. The project was implemented in four governmental health facilities (a regional referral hospital and three health centres) in rural and urban districts with a combined catchment population of 87,704 inhabitants (including about 10,000 IDPs) with 18,415 women of reproductive age. Save the Children is the only international NGO collaborating with the Regional Health Office in the provision of FP and PAC services in Puntland. By working with the Somali Ministry of Health to ensure that all three components of PAC are available throughout the communities, more women have access to lifesaving care.

Project implementation approach

The twofold programme approach focusses on service provision and community mobilisation; this includes capacity building, infrastructure improvement, supply chain management, monitoring and evaluation (M&E), and a tailored demand generation activities and advocacy strategy.

Service provision

Capacity building

The SCI capacity building strategy for health workers combines competency-based clinical training, supportive supervision, and individual provider support. A total of 12 service providers (2 Clinical Officers, 7 midwifes, and 3 nurses) received a three-week competency-based training for FP and PAC, with two staff receiving additional training to become master trainers themselves. Over time, refresher trainings are provided to ensure that providers’ skills are up-to-date. Due to standard staff turnover, newly hired providers receive training to ensure that each facility has sufficiently trained staff. Furthermore, having a diversity of cadres trained in PAC and FP can positively influence contraceptive uptake post-abortion.Citation23 The comprehensive training package included treatment for abortion complications, including manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) and misoprostol; postabortion FP counselling; and a full range of contraceptive methods, including long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) and permanent methods. Additionally, health workers were trained in other areas necessary for quality service delivery, such as Infection Prevention and Control. Following training, each provider was followed up within three to six months of training at their duty posts by facilitators and the programme team to provide further support and ensure good quality of care. Additional coaching was provided during on-the-job training and joint quarterly supportive supervision conducted by SCI and MOH. When client load was low, providers were assessed for competency by demonstrating on anatomic models. During supportive supervision, standardised checklists were used to assess health facility infrastructure and health workers’ competencies in providing PAC services, including postabortion contraception. Feedback was given to health workers based on identified gaps and improvement plans were agreed upon jointly by the supervisor and the health worker.

To monitor individual performance, health workers maintained individual logbooks recording PAC cases, the course of treatment provided, and assessments of competency during supportive supervision visits. The logbooks were complemented by a Microsoft Excel-based training database. The database enables the SCI programme team to monitor each service providers’ level of training, performed procedures, and supportive supervision visits received, and allows for the identification of training needs over time.

A crucial initiative within the programme’s capacity building strategy was the establishment of a training centre. SCI with the collaboration of the MOH constructed and equipped a training centre in Kakaar for the training of service providers on FP, PAC, and other RH trainings. The training centre combined with locally trained master trainers was crucial to maintaining the capacity of service providers for the duration of project implementation.

Infrastructure improvement and supply chain management

To ensure privacy and confidentiality, the infrastructure of the facility is essential. An initial health facility assessment identified areas for improvement to allow for PAC services to be provided with sufficient privacy and space for procedures, counselling, and postabortion contraception. Due to a lack of additional rooms at the supported sites, PAC procedures had to be integrated into the delivery rooms. Though this presented challenges in data management and privacy, due to the commitment of the MOH and trained providers to PAC services, these issues were resolved.

Essential PAC commodities were selected as per the MOH approved recommendations set forth by UNFPA. These included MVA kits, essential drugs (doxycycline hydrochloride, tablet, 100 mg; metronidazole, tablet, 250 mg; misoprostol, tablet 200 mcg; ibuprofen, tablets, 400 mg; oxytocin, injection, 10 IU/ml; lidocaine hydrochloride, injection, 10 mg/ml (1%); atropine sulfate, 1 mg/ml; water for injection; chlorhexidine gluconate, detergent solution, 4%; chlorhexidine gluconate, concentrated solution, 5%), and renewables (surgical gloves, examination gloves, syringes, needles, compresses, gauze, and sharps boxes). On a regular basis, pharmacy needs were estimated based on the monthly consumption of each health facility. Buffer stocks served as a back-up mechanism to prevent the rupture of equipment and supplies and avoid disruption of services. Procured commodities were stored in the MOH regional warehouse and distributed to health facilities within the existing MOH supply chain. Health service providers in the facilities were trained on how to request supplies based on the consumption during the last period and projections for the upcoming period. Excluding start-up, the project never experienced stock-outs of any essential supplies for PAC or family planning services.

Monitoring and evaluation

To monitor the programme, make programmatic decisions based on data, and optimise program performance, SCI implemented a comprehensive and tailored M&E framework. PAC registers were developed in collaboration with the MOH. The registers collect basic demographic information (age, parity, and locale), gestational age, mode of uterine evacuation, complications, medicines given, counselling for family planning, and contraceptive method chosen. PAC registers include PAC–FP data, as these services are provided in the same physical space. The data collected from these registers was then aggregated and entered into a database. On a monthly basis, the SCI team rectified missing data, reviewed and analysed the data, discussed with the MOH and health facility staff, and developed action points for areas of improvement. Because programme metrics are consistently tracked, programme staff and providers can prioritise their work to address the most critical areas for improvement. In addition to routine data collection, Client Exit Interviews (CEI) and an external programme evaluation were conducted to assess client satisfaction and the quality of the service provision. CEIs served as a programme accountability mechanism by providing information on client satisfaction and suggestions for improvement. Annual CEIs were conducted by trained data collectors using standardised semi-structured questionnaires. In 2015, an external programme evaluation was completed by the RAISE Initiative at Columbia University. The evaluation included an assessment of programme areas, such as service provision, waste management, infection prevention and control, supplies and equipment, supportive supervision, staff training, data use, and community activities. The results indicated that FP and PAC services were available and utilised as evidenced by progressive client increase. Low percentage of LAPM uptake and limited involvement of men in community activities were identified as areas for improvement. The findings and recommendations from the independent evaluation informed SCI’s quality improvement efforts.

Community mobilisation

Demand generation activities

Using a systematic community awareness strategy, SCI worked in collaboration with the MOH to improve knowledge and awareness of PAC services and prompt behaviour change among communities in Puntland. The approach involves working with a broad range of community actors, including Community Health Committees (CHC), Community Health Workers (CHWs), FP/PAC Champions, and community and religious leaders. The targeted communities were educated on the risks related to complications from abortion, the health benefits of PAC, and FP services. Prior to April 2014, there were no CHWs working under the programme and client follow-up was initially done by phone because of the sensitivity around FP and PAC services. Following improved community acceptance of PAC services, two CHWs per facility were recruited and trained to conduct household visits, client tracking, and community sensitisation using tailored information, education, and communication materials and job aids. Religious and community leaders have come to champion PAC and have worked to ensure community-based solutions to ensure that women are able to reach health facilities in a timely manner to receive PAC services. Furthermore, they have discussed the importance of PAC frequently within communities to reduce the potential stigma that initially existed around PAC services.

Advocacy approach

SCI’s advocacy approach involves the engagement of MOH both at regional and central levels for the purpose of creating an enabling environment for the delivery of PAC services. Due to initial sensitivities regarding FP, PAC services were approached as a critical component of maternal health. SCI involved the government in programme design, implementation, reviews, and evaluation. During periodic reviews, SCI shared data and lessons learned from programme implementation with government officials at all levels, with the objective of influencing government plans, policies, and approaches. The government expressed willingness to adopt SCIs approach to PAC and family planning across Puntland.

Methodology

A descriptive analysis was conducted to observe changes in PAC-related health service statistics attributable to SCI’s FP and PAC programme. All patients who received PAC services at the four SCI-supported health facilities from January 2013 to December 2015 were included in this analysis. Raw client data collected through the programme database were analysed using MS Excel to generate frequency tables, averages and charts. Data were cleaned and verified on a monthly basis as part of the routine M&E system.

Findings

Services and treatment

From January 2013 to December 2015, a total of 1111 clients received PAC services at the four SCI-supported health facilities. The number of PAC clients increased from a monthly average of 19.91 PAC clients (SD = 15.95) in 2013 to a 34.75 monthly average (SD = 4.11) in 2014, and finally to a monthly average of 37.92 PAC clients (SD = 9.52) in 2015 (). The mean increase was significant between 2013/2014 (p = .006) and 2013/2015 (p = .001).

During the same three-year period, 57% (629/1111) clients were treated with MVA, 24% (268/1111) with misoprostol, while 19% (214/1111) did not require an evacuation, as products of conception had been expelled naturally. The monthly mean number of PAC clients treated with misoprostol more than tripled from 3.17 (SD = 4.20) in 2013 to 11.5 (SD = 3.21) in 2015 (p < .001).

Acceptance of postabortion FP counselling and care

During the 2013–2015 period, 98% (1090/1111) of PAC clients were counselled for postabortion contraception of which 88% (955) accepted a contraceptive method before leaving the facility (). The percentage of PAC clients adopting a method of family planning was generally high and the average monthly total of PAC clients accepting FP rose from 15.58 (SD = 12.92) in 2013 to 35.75 (SD = 6.14) in 2015 (p < .001). After a notable decline in the proportion of PAC clients adopting a method of contraception in May 2014, trainings and on-site coaching were conducted with providers to ensure quality care and counselling were being provided.

Figure 3. Percentage of PAC clients who adopt FP, by month; Save the Children, Puntland, Somalia, 2013–2015

Over the entire 2013–2015 period, 70% (673/1111) of PAC clients opted for a short-term method of family planning, with 34% (375/1111) choosing oral contraceptive pills and 27% (298/1111) choosing injectables. Of those adopting an LARC method, 14% (160/1111) opted for an intrauterine device (IUD) and 11% (122/1111) chose an implant. As illustrates, the contraceptive method mix for PAC–FP clients shifted greatly over time to include a greater variety of contraceptive choices. Nearly 30% (68/223) opted for LARC in the final six months (July – December 2015) compared to 10% (3/29) in the first six-month period (January – June 2013).

Discussion

In Somalia, a religiously conservative country with highly restrictive abortion laws and a health system damaged by prolonged crisis, access to timely and quality comprehensive PAC is not only critical to manage complications from miscarriage and unsafe abortion practices, but also to prevent future unplanned pregnancies through the provision of contraception. Achievements and results of the PAC programme implemented by SCI in Puntland, Somalia demonstrate that it is feasible to successfully implement quality PAC services in an area affected by conflict and natural disasters and a sensitive cultural context. From programme inception to December 2015, the project reached 1111 women with comprehensive PAC services, exceeding the programme targets based on population size, total fertility rate, and facility data. The steady increase in PAC service utilisation at the supported health facilities shows that through a comprehensive and well-implemented programme model, acceptance and uptake of PAC services can be increased even in unstable humanitarian settings. It also proves that the programme approach of improved service delivery through adequate equipment and supplies, capacity building, and community engagement is a successful programme model for the delivery of PAC services in humanitarian settings, and could potentially be replicated in similar contexts. The project ensured that competent staff were available in all facilities 24/7, with a solar backup energy source, and essential supplies were never out of stock, thereby ensuring consistent and reliable service availability.

Sustained engagement with the different segments of the communities, especially religious and community leaders was vital to clarifying misconceptions about PAC and postabortion FP, and was crucial to improve service utilisation. The involvement of the MOH in all stages of the programme cycle fostered good collaboration and paved the way for successful programme implementation. While our current approach has been successful in reaching the community with services and awareness raising on abortion generally, certain gaps remain. For example, the community engagement approach currently does not specifically target men and youth. Furthermore, the messaging around PAC and contraception was not tailored to the specific needs of the various groups in the community. Tailored messages along more diversified community awareness activities would have the potential to address and mobilise specific community members, such as husbands and male youth, more effectively.

Before the implementation of the programme, only the hospital had PAC services available and exclusively performed all evacuations using D&C. Despite its advantages, safety and cost-effectiveness, MVA was largely unavailable in Puntland due to the absence of trained personnel and supplies. Following the implementation of PAC through MVA and misoprostol at health centres and hospitals and training of staff, PAC was performed by mid-level health workers, such as nurses and midwives. MVA was the preferred method of treatment for incomplete abortion in our setting (57%) as compared to misoprostol (24%). The introduction not only made PAC services available at health centres, it also increased service availability in remote areas which were previously disconnected to any PAC treatment option. Task sharing of PAC through the introduction of MVA and misoprostol increases availability, access, and safety of services. Available evidence shows that both methods, MVA and misoprostol, are equally effective in the treatment of incomplete abortion and other complications.Citation24 The WHO recommends both methods for the treatment of incomplete abortion. MVA is safer, more cost effective, and more feasible to implement in low resource settings compared to D&C which was the predominant method before the FP and PAC project. Misoprostol is a safe non-surgical alternative for the treatment of incomplete abortion and can safely be used with lower cadre heath workers with minimal skills and in rural settings.Citation8

Client counselling on postabortion contraception is a standard component of PAC. At SCI-supported sites, all PAC clients should systematically receive contraceptive counselling and potentially the method of their choice before discharge. The provider counsels PAC clients on the available methods and effectiveness, side effects, and use, and women choose their preferred contraceptive method. One successful strategy was to make contraceptive services available directly at the PAC service point to avoid referral of clients such that a client can be managed for abortion complications and offered postabortion contraception by the same provider. The proportion of women who accepted postabortion contraception in our setting is above the internationally recommended target of 80% and is also higher compared to similar fragile settings such as Djibouti, Chad, Pakistan, DRC, and Mali, where PAC–FP rates ranging from 28% to 77% have been reported.Citation25 Although the percentage of PAC clients who accepted a modern FP method fluctuated, likely due to natural variations, it continuously improved due to training on counselling for postabortion FP, individual provider support, and follow-up during supportive supervision. Our finding is similar to what has been reported in other low income countries where PAC–FP acceptance was reported to have improved following training specifically on counselling.Citation26

Though 70% of PAC clients opted for short-term methods of contraception over the three-year period, a gradual shift towards more effective LARC methods was observed. It is expected that clients’ acceptance of LARC methods increases as misconceptions are clarified and provider skills improve over time, particularly in regard to counselling. While there is no standard “expected” method mix for any setting, predominance (>50% of any method) of one or two methods in any setting requires further investigation as it could imply an insufficient range of options, provider bias, or cultural preferences.Citation27,Citation28 In the context of the Puntland programme, all options were always available so the issue of insufficiency of methods does not arise. Other sociocultural factors which could be influencing the choice of short-term methods in our setting could be the desire of most women to return to fertility as soon as possible after a spontaneous abortion. In Somali culture, large families are valued and, therefore, women are constantly exposed to societal pressure to bear more children. It is also possible that, due to the relatively young age of our general clientele, provider bias could be playing a role in influencing the FP choices of women. Data from a sample of clients from a register review conducted in Puntland in December 2014 indicated that 57% of the general FP clients who accepted a FP method in SCI-supported facilities were less than 30 years of age. Although 50% of general clients had five or more children, none of the clients below 25 years were given an IUD.Citation29 Further investigation will be required, however, to gain a better understanding of the factors affecting women's choices of contraception post-abortion in our setting.

Limitations

Our data are routine programme data and the coverage of intervention is limited to four health facilities; however, in April 2016, the programme was expanded to six additional facilities and has shown to be scalable and cost effective. Our findings cannot be generalised to the whole population as the characteristics of the population accessing our services may differ from the general population. There was no baseline contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) prior to the programme inception; as such it is not possible to measure the contribution of our program to improving general CPR. Furthermore, the study lacks an appropriate comparison group that could be used as a control.

Conclusion

Our data shows that comprehensive PAC services can be implemented in politically unstable, culturally conservative settings where abortion and modern contraception can be sensitive and stigmatised matters among communities, health workers, and policy makers. The multipronged approach is essential and was taken to ensure that quality PAC services were implemented in an effective manner. The approach focused on health worker capacity building, continuous improvement in service delivery, consistent collaboration with the local health authorities, and sustained community engagement. Like all humanitarian settings, large unmet needs exist for PAC services in Somalia. More resources must be committed to further expand the provision of quality PAC services in crisis-affected countries in order to treat postabortion complications, ensure effective family planning counselling and provision, and contribute to the overall reduction in maternal mortality globally.

References

- WHO. Maternal mortality fact sheet. 2016.

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):e323–e333. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X

- Sedgh G, Singh S, Shah IH, et al. Induced abortion: incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008. Lancet. 2012;379(9816):625–632. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61786-8

- Singh S, Darroch J, Ashford L. Adding it up: the costs and benefits of investing in sexual and reproductive health 2014. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2014.

- Singh S, Maddow-Zimet I. Facility-based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: a review of evidence from 26 countries. BJOG. 2016;123(9):1489–1498. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13552

- WHO. Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. Geneva: WHO; 2011.

- Vlassoff M, Shearer J, Walker D, et al. Economic impact of unsafe abortion-related morbidity and mortality: evidence and estimation challenges. Vol. 59. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies; 2008.

- Barot S. Implementing post-abortion care programs in the developing world: ongoing challenges. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2014.

- RamaRao S, Townsend JW, Diop N, et al. Post-abortion care: going to scale. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;37(1):40–44. doi: 10.1363/3704011

- Swatzyna RJ, Pillai VK. The effects of disaster on women’s reproductive health in developing countries. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5(4):106. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n4p106

- Tunçalp Ö, Fall IS, Phillips SJ, et al. Conflict, displacement and sexual and reproductive health services in Mali: analysis of 2013 health resources availability mapping system (HeRAMS) survey. Confl Health. 2015;9(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s13031-015-0051-8

- McGinn T, Austin J, Anfinson K, et al. Family planning in conflict: results of cross-sectional baseline surveys in three African countries. Confl Health. 2011;5(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-5-11

- Casey SE, Chynoweth SK, Cornier N, et al. Progress and gaps in reproductive health services in three humanitarian settings: mixed-methods case studies. Confl Health. 2015;9(1):S3. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-S3

- Austin J, Guy S, Lee-Jones L, et al. Reproductive health: a right for refugees and internally displaced persons. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(31):10–21. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31351-2

- Catino J. Meeting the Cairo challenge: progress in sexual and reproductive health. Implementing the ICPD Programme of Action. New York, NY: Family Care International; 1999.

- Casey SE. Evaluations of reproductive health programs in humanitarian settings: a systematic review. Confl Health. 2015;9(1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-S1

- Lehmann A. Safe abortion: a right for refugees? Reprod Health Matters. 2002;10(19):151–155. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(02)00026-5

- UNFPA. Population Estimation Survey; 2013.

- PRB. World population data sheet. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau; 2016.

- World Bank. World development indicators database; 2016.

- Save the Children. The urban disadvantage: state of the World’s mothers 2015. Fairfield, CT: Save the Children Federation; 2015.

- OCHA. Humanitarian needs overview: Somalia; 2015.

- Maxwel L, Voetagbe G, Paul M, et al. Does the type of abortion provider influence contraceptive uptake after abortion? An analysis of longitudinal data from 64 health facilities in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):586. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1875-2

- Clark W, Shannon C, Winikoff B. Misoprostol for uterine evacuation in induced abortion and pregnancy failure. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2007;2(1):67–108. doi: 10.1586/17474108.2.1.67

- Curry DW, Rattan J, Huang S, et al. Delivering high-quality family planning services in crisis-affected settings II: results. Global Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(1):25–33. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00112

- Tripney J, Kwan I, Bird KS. Post-abortion family planning counseling and services for women in low-income countries: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.014

- Bertrand JT, Sullivan TM, Knowles EA, et al. Contraceptive method skew and shifts in method mix in low-and middle-income countries. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;40(3):144–153. doi: 10.1363/4014414

- Sullivan TM, Bertrand JT, Rice J, et al. Skewed contraceptive method mix: why it happens, why it matters. J Biosoc Sci. 2006;38(04):501–521. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005026647

- Save the Children. Family planning and post-abortion care register review data; 2015.