Abstract

This case study describes the health response provided by the Ministry of Health of Nepal with support from UN agencies and several other organisations, to the 1.4 million women and adolescent girls affected by the major earthquake that struck Nepal in April 2015. After a post-disaster needs assessment, the response was provided to cater for the identified sexual and reproductive health (RH) needs, following the guidance of the Minimum Initial Service Package for RH developed by the global Inter-Agency Working Group. We describe the initiatives implemented to resume RH services: the distribution of medical camp kits, the deployment of nurses with birth attendance skills, the organisation of outreach RH camps, the provision of emergency RH kits and midwifery kits to health facilities and the psychosocial counselling support provided to maternity health workers. We also describe how shelter and transition homes were established for pregnant and post-partum mothers and their newborns, the distribution of dignity kits, of motivational kits for affected women and girls and female community health volunteers. We report on the establishment of female-friendly spaces near health facilities to offer a multisectoral response to gender-based violence, the setting up of adolescent-friendly service corners in outreach RH camps, the development of a menstrual health and hygiene management programme and the linkages established between adolescent-friendly information corners of schools and adolescent-friendly service centres in health facilities. Finally, we outline the gaps, challenges and lessons learned and suggest recommendations for preparedness and response interventions for future disasters.

Résumé

Cette étude de cas décrit la réponse donnée par le Ministère népalais de la santé, avec le soutien d’institutions des Nations Unies et de plusieurs autres organisations, aux 1,4 million de femmes et d’adolescentes touchées par le séisme majeur qui a frappé le Népal en avril 2015. Après une évaluation des besoins postérieure à la catastrophe, l’intervention a été mise en œuvre pour répondre aux besoins de santé sexuelle et génésique identifiés, en suivant les recommandations du dispositif minimum d’urgence pour la santé génésique, établi par le Groupe de travail interorganisations. Nous décrivons les initiatives appliquées pour rétablir les services de santé génésique : distribution de trousses médicales dans les camps, déploiement d’infirmières compétentes pour assister les accouchements, organisation de camps de santé génésique de proximité, fourniture de trousses de santé génésique d’urgence et de nécessaires pour sages-femmes aux centres de santé, et soutien psychosocial prodigué aux agents de santé travaillant dans les maternités. Nous décrivons également comment des abris et des foyers relais ont été créés pour les femmes enceintes, les jeunes mères et leurs nouveau-nés, la distribution de trousses hygiéniques [pour redonner un sentiment de dignité à leurs bénéficiaires], de kits de motivation pour les femmes et les adolescentes touchées, et les femmes enrôlées comme agents de santé bénévoles. Nous décrivons l’aménagement d’espaces adaptés aux femmes près des centres de santé pour offrir une réponse multisectorielle à la violence sexiste, la création de points de services destinés aux adolescents dans des camps de santé génésique de proximité, la mise au point d’un programme de prise en charge de la santé et l’hygiène menstruelle, et les liens instaurés entre les points d’information pour adolescents dans les écoles et les centres de services s’adressant aux jeunes dans les établissements de santé. Enfin, nous soulignons les lacunes, les difficultés et les leçons retirées ; et nous proposons des recommandations pour la préparation et la réponse à de futures catastrophes.

Resumen

Este estudio de caso describe la respuesta de salud proporcionada por el Ministerio de Salud de Nepal con el apoyo de organismos de las Naciones Unidas y varias otras organizaciones, a 1.4 millones de mujeres y adolescentes afectadas por el gran terremoto que azotó a Nepal en abril de 2015. Después de una evaluación de necesidades post-desastre, la respuesta fue proporcionada para atender las necesidades de salud sexual y reproductiva identificadas, siguiendo la orientación del Paquete de Servicios Iniciales Mínimos de salud reproductiva creado por el Grupo de Trabajo Interinstitucional. Describimos las iniciativas aplicadas para reanudar la prestación de servicios de salud reproductiva: la distribución de kits para campamentos médicos, el despliegue de enfermeras con habilidades de asistencia de partos, la organización de campamentos de extensión en salud reproductiva, el suministro de kits de salud reproductiva para emergencias y kits de partería a unidades de salud, y el apoyo de consejería psicosocial brindado a trabajadores de salud materna. Además, describimos cómo se establecieron refugios y hogares de transición para madres embarazadas y posparto y sus recién nacidos, la distribución de kits de dignidad, de kits de motivación para mujeres y niñas afectadas y voluntarias sanitarias comunitarias. Informamos sobre el establecimiento de espacios amigables a mujeres cerca de las unidades de salud, con el fin de ofrecer una respuesta multisectorial a la violencia de género, el establecimiento de puestos de servicios amigables a adolescentes en campamentos de extensión en salud reproductiva, la creación de un programa de gestión de salud e higiene menstrual, y los vínculos establecidos entre puestos escolares informativos amigables a adolescentes y centros de servicios amigables a adolescentes en establecimientos de salud. Por último, señalamos las brechas, retos y lecciones aprendidas; y sugerimos recomendaciones de intervenciones de preparación y respuesta a futuros desastres.

Nepal earthquake 2015: introduction and context

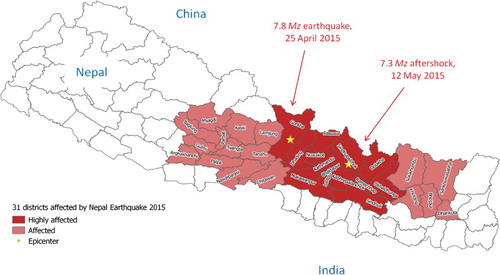

On Saturday 25 April 2015, a magnitude 7.8 Mz earthquake struck Nepal with the epicentre at Gorkha district, followed by hundreds of aftershocks including one that measured 7.3 Mz on 12 May 2015 with the epicentre at Sindupalchowk district, which caused additional severe destruction. A total of 31 out of 75 districts were affected by the earthquake and aftershocks, and of these, 14 severely ().Citation1 In this southeast Asian low-income country of around 28 million people,Citation2 eight million were directly affected,Citation1 and 8890 casualties and 22,303 injuries reported.Citation3 More than 885,000 private houses and 1400 government buildings were severely damaged or destroyed, including 1147 public health facilities.Citation4 Due to the earthquake, other related small-scale disasters ensued and caused further damage, including several landslides that blocked access to large areas for several weeks, causing riverine floods and more deaths and injuries.

Before the earthquake, the maternal mortality ratio in Nepal was estimated at 190 per 100,000 live births.Citation5 UNFPA estimated that due to the earthquake, 1.4 million women and girls of reproductive age were affected, and among them, 93,000 were pregnant women.Citation6 UNFPA estimated that 10,300 would deliver every month in the affected area, including 1000 to 1500 who were at risk of pregnancy-related complications requiring cesarean-sections.Citation6

Moreover, as shown in other post-disaster situations, women were at greater risk of gender-based violence.Citation7 For instance, based on estimated numbers of affected people and using the Inter-agency Working Group (IAWG) on Reproductive Health in Crises’ Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) calculator for estimating needs during humanitarian emergencies,Citation8 around 28,000 women potentially required post-rape care services.

Five hours after the earthquake, the Ministry of Health (MoH), Government of Nepal activated the Health Emergency Operation Center. All civil, army and security forces immediately initiated search and rescue operations while tertiary care hospitals designated as “hub hospitals”Footnote* in the preparedness phase began treating the injured, in coordination with their pre-identified “satellite” hospitals. In total, more than 84 non-governmental organisations, and 137 foreign medical teams and around 50 Nepali national medical teams joined the efforts to support the MoH in responding to the disaster.Citation9

On 26 April 2017, the first meeting of the Health Cluster was convened by the MoH. Co-led by the World Health Organization (WHO), the function of this cluster was to coordinate the health sector response, identify the needs and gaps and prioritise the allocation of resources optimally.

On 1 May, a post-disaster needs assessment was initiated under the leadership of the Government of Nepal in all 31 districts affected by the earthquake. It covered 23 thematic areas including health and population services, and involved more than 250 officials and experts from the government and external development partners. Pre-disaster baseline data were compared with observed post-disaster conditions. Damage, loss and cost of service provision to the affected population were estimated, based on the inventory of damages to buildings, equipment, instruments, furniture, pharmaceuticals and supplies.

The aim of this case study is to review the post-disaster health response provided by the MoH with support from the UN agencies, bi-lateral development partners and the international and national non-governmental and civil society organisations to cater to the needs of adolescents and women. We outline the successes, gaps, challenges and lessons learned from this response and suggest recommendations for preparedness and response interventions for future disasters.

Methods and sources of information

In March and April 2017, a systematic review of published and unpublished literature on health response to the Nepal Earthquake 2015 was conducted by the authors.

First, the Medline repository was searched using the PubMed portal and the key words “Nepal”, “earthquake” and “response”, to locate relevant articles describing interventions implemented as a response to women’s needs. Of the 11 matches, only 3 were related to gender issuesCitation10 or women’s health. Of them, two articles were only commentaries (not bringing out any relevant information to this review), and one was about human trafficking during emergencies.

Next, data collected by WHO in 2016 in preparation for a joint MoH/WHO conference on the health sector response to the Nepal Earthquake 2015 was reviewed, and also the interventions implemented during the immediate and intermediate phases post-disaster were described. Key elements of discussion for drawing policy, technical and operational recommendations were also found.

Third, in order to assess if response interventions were implemented per existing national contingency plans, the National Disaster Response Framework (NDRF) that defines the roles and responsibilities of government and non-government agencies involved in disaster risk management in Nepal,Citation11 and the health sector component of the NDRF that was developed by the MoH with WHO support in 2014Citation12 were reviewed.

Available grey literature, such as the daily reports produced by the MoH, proceedings of the national midwifery conferences, internal reports and publications from WHO Country Office for Nepal,Citation1 UNFPA Country Office,Citation7 UNICEF Country Office, as well as publications from other agencies involved in the health sector response, such as the Midwifery Society of Nepal (MIDSON) and Deutsche Gesellschaft fuer internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) were compiled and reviewed. Main stakeholders engaged in sexual and reproductive health (SRH) or maternal, newborn and child and adolescent health programs were contacted for their reports on the response to the Nepal Earthquake 2015. The findings of the post-disaster needs assessmentCitation4 were also reviewed, as well as communications, meeting minutes and reports from the reproductive health (RH) sub-cluster meetings held at the national level and at two district-based humanitarian hubs.Citation13

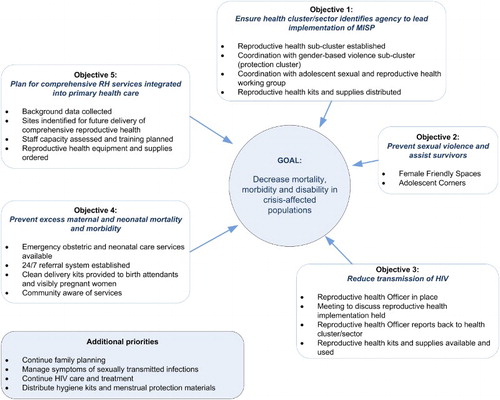

Finally, the reports of an inter-agency evaluation led by the Women’s Refugee Commission (WRC) on implementation of the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for RH in the five months following the earthquake in the capital, Kathmandu, and in Sindhupalchowk, one of the humanitarian hubs and amongst the most affected districts, were consulted.Citation14 The MISP is a coordinated set of priority activities designed to prevent and manage the consequences of sexual violence, reduce HIV transmission, prevent excess newborn and maternal morbidity and mortality and plan for comprehensive RH services.Citation15 The WRC evaluation explored awareness of the MISP, implementation of the standard and factors that influenced implementation.

Findings of this desk review were reviewed by the authors of this article who were involved in the response (7/10 authors) at three successive triangulation meetings during which we listed the successes of this response, the challenges met and the unfilled gaps; we outlined the key findings and together drew the lessons learned.

Sexual and reproductive health response

More than 30 agencies have been involved in the SRH response to the 2015 earthquake in Nepal.Citation13 Here below the response interventions are described in the chronological order of their implementation (immediate and intermediate response and recovery phases).

Immediate response phase: within the first month

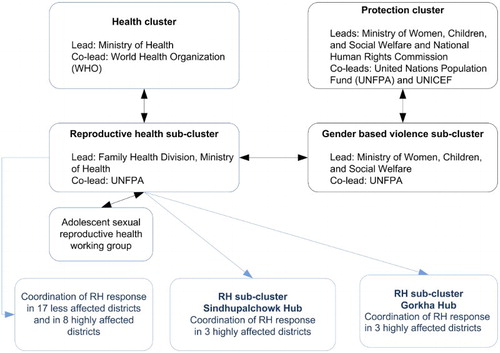

Four days after the earthquake, an RH sub-cluster, led by the Family Health Division of the MoH and co-led by UNFPA, was activated under the umbrella of the central health cluster. This was a coordination structure decided by the health cluster which was not planned in the National Disaster Response Framework, but is a key objective in the MISP for RH guidelines that was adapted and endorsed by the MoH in early 2015 (). By May 2015, at least 33 agencies were active in this sector, which was termed the RH sub-cluster.

Figure 2. MISP for RH. Source: UNFPA fact-sheetCitation17

The first objective of the RH sub-cluster was to conduct a rapid situation analysis. A data collection tool was developed based on MISP guidelines and other disaster response guidelines (Supplemental File 2). This situation analysis was conducted in the 14 most affected districts by teams of senior nurses from the MIDSON, the MoH, obstetricians from the main maternity hospital and UN personnel. It revealed that out of the 360 existing basic emergency obstetric and neonatal care sites or birthing centres, 112 were severely and 144 were partially damaged. Six district hospitals and 331 rural health facilities, including staff quarters, were also severely damaged in these districts. As a result, emergency obstetric and neonatal care services were disrupted in most of these districts and RH services, including provision of anti-retroviral therapy, family planning and management of sexually transmitted infections, were largely suspended.

Immediate SRH needs were identified from the rapid situation analysis followed by additional field visits and communications with affected health facilities.Citation13 The following eight priorities were presented to the central health cluster: (1) provide tents to damaged health facilities to ensure the continuity of health services; (2) distribute RH kits to health facilities providing basic emergency obstetric care, with a special focus on hard to reach areas; (3) conduct RH mobile camps in areas where health facilities are no longer in operation; (4) distribute RH kits for comprehensive emergency obstetrical care to the districts; (5) distribute motivational packages to health workers and female community health volunteers (FCHVs); (6) prevent and manage risks of sexual violence; (7) strengthen the health workers’ skills on gender-based violence with a special emphasis on clinical management of rape and (8) distribute dignity kits for girls and women.

The following were defined as intermediate needs:Citation4,Citation13,Citation16 (1) re-establish or strengthen reproductive health, maternal and neonatal health and child health services in all affected areas; (2) establish transition homes in the premises of health facilities to cater for a maximum number of pregnant women to deliver, women who have recently delivered and their infants, and injured children under 5 years of age in each district; (3) strengthen intersectoral coordination in particular to prevent gender-based violence and to establish temporary infrastructure for health service provision and (4) plan the installation of pre-fabricated buildings in places where health facilities are operating under tents (in view of the approaching monsoon).

After the rapid situation analysis, the RH sub-cluster began coordinating the response among partners to avoid duplication of interventions and to address gaps and challenges. One of the first decisions was to supply clean delivery kits (including chlorhexidine for prevention of umbilical cord infection among newborns) to all visibly pregnant women in all 31 earthquake-affected districts, except in Kathmandu Valley where there was still access to functional health facilities.Citation14 The RH sub-cluster also decided to upload relevant national maternal, newborn and child health and RH guidelines and protocols, including STI/HIV management and infection prevention guidelines to the Health Emergency Operation Center website for use by both national and foreign medical teams. New guidelines, such as how to use emergency contraceptives and how to provide friendly services to adolescents, were developed and disseminated amongst partners.

Several initiatives were quickly implemented by the RH sub-cluster partners to restart reproductive health services and to help the health workers cope with the surge of activities and health service disruption, including (1) setting up of WHO Medical Camp Kits (MCKs) and medical tents to accommodate the provision of RH services; (2) deployment of nursing and medical teams to help maternity staff cope with the emergency and surge of activity; (3) organisation of outreach RH camps to provide free of charge SRH services for earthquake-affected people in remote communities in all 14 affected districts;Citation7 (4) distribution of Emergency RH kitsCitation7,Citation17 and (5) provision of psychosocial counselling to maternity staff ().

Table 1. Response interventions implemented during the immediate response phase, after Nepal Earthquake 2015

Meanwhile, and within two weeks after the earthquake, RH sub-clusters were formed in two humanitarian hubs in the most affected area, one in the western part at Gorkha and the other in the eastern part at Sindupalchowk ().Citation14 These sub-clusters were led by the respective District Health Offices, co-led by UNFPA and attended by Health Cluster co-leads from WHO and all RH partners. The clusters met regularly to refine the needs and coordinate the interventions planned by or with the central RH sub-cluster. The RH sub-clusters of the two humanitarian hubs were also tasked to coordinate the RH response in other affected districts assigned to the respective humanitarian hubs.

At the end of May 2015, C-section services were available in all district hospitals except one in the 14 most affected districts.Citation13 All outpatient department services, including antenatal care, were re-established in all service sites and the majority of birthing centres had started to provide 24-hour delivery services in tents or undamaged buildings.

Intermediate response phase: from the second to the sixth month after the disaster

The interventions described above allowed SRH services to resume in all affected areas by the end of the immediate response phase. Additional measures were taken during the intermediate response phase to further improve access to these services and to ensure their quality. A total of 1080 midwifery kits were distributed to maternity teams as well as 53,000 newborn suits to avoid hypothermia.

Additionally, in all 14 most affected districts, except Kathmandu, UNICEF and UNFPA established 50 shelter and transition homes on the premises of health facilities delivering maternity services. They were residential facilities where pregnant women and post-partum women could be accommodated free of charge. These shelter and transition homes aimed to improve the accessibility of health care services, mainly obstetrical care for pregnant women, in affected districts. UNICEF found that easy access to medical care, a safe shelter with water supply and sanitation facilities available and free meals (four per day) were primary reasons for women to use the shelter homes. Gender-based violence (GBV) prevention and care services were also available. During winter 2015–2016, these facilities were further outfitted to protect those who stayed there from the cold, and blankets were distributed to keep children and women warm. A total of 15,301 women and more than 5000 newborns benefited from these shelter and transition homes (details provided in ).

Table 2. Response interventions implemented during the intermediate response phase, after Nepal Earthquake 2015

Meanwhile, the RH sub-cluster started to advocate for the inclusion of SRH, maternal, newborn and child health services in all immediate life-saving responses implemented by health and other sectors. Linkages were established between the RH sub-cluster and the gender-based violence sub-cluster operating under the umbrella of the protection cluster. A separate adolescent sexual reproductive health (ASRH) working group was formed within the RH sub-cluster to ensure that ASRH issues were adequately integrated into the overall RH-response ().

Facilitated by this inter-cluster coordination and cooperation, other interventions were designed and implemented to respond to specific needs of women and adolescents, such as the distribution of dignity kits to 56,000 women and girlsCitation18 and of motivational kits to 10,327 female community health volunteersCitation7 (Details in ). Meanwhile, the campaign “Dignity First” was launched by the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare and UNFPA to raise awareness on the unmet needs of earthquake survivors, particularly their needs for reproductive health and hygiene.Citation7

A total of 97 Female-friendly spaces (FFS) consisting of large tents staffed with care-takers and counsellors were established near health facilities to offer a multisectoral response to gender-based violence. FFSs were safe spaces for girls and women to rest, to talk freely, to receive psychosocial counselling, to participate in awareness and recreational activities, to get dignity kits and to find shelter services and links to establish livelihood activities. More specifically, gender-based violence screening and counselling were available at these spaces and survivors of gender-based violence could be safely treated or referred to relevant facilities for safe abortion whenever necessary. A total of 147,337 women and adolescents in the 14 most affected districts benefited from these spaces,Citation7 while over 15,000 girls, women and survivors of GBV received adapted psycho-social counselling services, case management and support. UNFPA recorded 2799 cases of GBV from the female-friendly spaces and the outreach RH camps.

Adolescent-friendly service corners were set up in all 132 outreach RH camps, run by trained adolescent facilitators and volunteers, of which 56% were girls. These adolescents conducted awareness-raising activities for their peers and encouraged them to utilise the SRH services in an adolescent-friendly and safe environment. Linkages between adolescent-friendly information corners of schools and adolescent-friendly service centres in health facilities were established to promote the utilisation of these services by students in need. The adolescent service corners reached over 4231 young people of which 71% were femalesCitation7,Citation19 and more than 14,666 adolescents received ASRH services through the overall intervention.

A Menstrual health and hygiene management (MHM) programme was developed and implemented in all 14 most affected districts. Under the umbrella of both the MoH and the Ministry of Education, schoolteachers and health workers were trained on MHM information and education as well as on how to locally make re-usable sanitary pads, using their own old cotton clothes. In Dhading district, for instance, the MHM programme funded by German Development Cooperation benefited 4148 adolescent girls from 42 schools.

The role of the RH sub-cluster at the central level and in the two humanitarian hubs remained crucial throughout the whole intermediate response phase. Collecting, compiling and sharing local level information was indispensable in addressing the remaining gaps and avoiding duplication of response interventions. The RH sub-cluster significantly contributed to the coordination of the interventions of partners by preparing regular updates of the “4W Coordination Tool” which recorded “who” was working “where”, on “what”, and since or until “when”.

Recovery phase: from the seventh month after the disaster up to the present

All relevant interventions initiated during the immediate and intermediate response phases were extended during the recovery phase. In addition, several guidelines and tools were developed and implemented during this phase to upgrade the knowledge and skills of various health workers on RH and disaster response issues (). Finally, the reconstruction of many health-related structures also began during this phase. In the most affected areas, several agencies became involved in the reconstruction or retrofitting of completely or partially damaged public health care facilities respectively. In some cases, buildings were repaired, while in other cases pre-fabricated structures were installed or permanent buildings constructed. For example, GIZ and UNICEF constructed 34 and 50 new pre-fabricated health posts, each with one delivery room, respectively. Additional support included energy and water supply equipment, waste management solutions and provision of medical equipment or basic furniture.

Table 3. Training, guidelines and tools developed during the recovery phase

Discussion

Structural and environmental conditions have seriously challenged the RH response after this disaster. First, the Health Sector component of the National Disaster Response Framework and Plan (NDRF) published one year prior to the Earthquake by the MoH clearly described the major challenges Nepal would have to face should a large-scale disaster happen. Private and public hospitals “did not have the capacity to respond to the health needs” and there was “no comprehensive disaster management guideline in place”.Citation11 The NDRF stated that because of the limited institutionalised emergency preparedness, there were “gaps in resources for the health sector, including buffer stocks of medicines and equipment”. Moreover, in addition to these structural challenges, the humanitarian response was further hampered because many affected areas were geographically hard to reach, and many roads and bridges had been damaged. The monsoon season started right after the disaster further complicating access to remote areas, due to floods and landslides. In addition, during winter 2015, a 4-month blockade at the Nepal-India border led to shortages of fuel and medicines and thus, further affected the pace of the recovery process.Citation21

Despite the challenges, the RH sub-cluster led a largely effective response to the disaster.Citation14 Several factors may have facilitated this response. First of all, the health sector collaboration was built on a longstanding commitment of civil society organisations as well as with the private sector. The activation of the RH sub-cluster under the leadership of the MOH/Family Health Division within a few days of the disaster helped in prioritising the interventions to be immediately implemented, with support from several sub-cluster agencies and related development partners. Other contributive factors that enabled the implementation of a large-scale and timely response were: media mobilisation which helped affected communities to express their needs; UN agencies preparedness and very effective resource mobilisation from external development partners as well as from the government.

One month after the earthquake, all outpatient department services, including antenatal care, were re-established in all services sites operating either from tents or in undamaged buildings, the majority of birthing centres were able to provide delivery services; outreach RH camps were conducted to reach remote communities and C-section services were available in 11 of the district hospitals in the 14 most affected districts. Five months after the earthquake, all MISP services and priority activities were largely available in these districts, as assessed by an Inter-agency team led by the Women’s Refugee Commission.Citation14 It should also be acknowledged that despite the efforts made, political turmoil and harsh geographical and climatic conditions have made the recovery phase more laborious and have hampered reconstruction and rehabilitation of damaged health infrastructure.

Interestingly, most response interventions implemented were not clearly outlined in the health sector component of NDRF and plan. For instance, the activation of a dedicated sub-cluster for RH issues was not specified in the NDRF. The only SRH measure clearly mentioned in the NDFR was the need to address gender-based violence starting as early as 24 hours after the disaster. Very effective measures taken, such as conducting outreach RH camps, setting up female-friendly spaces or adolescent-friendly corners, were not pre-planned or guidelines for implementation were not readily available and were built on other effective in-country experiences (such as the uterine prolapse camps in Nepal).Citation21 These interventions were discussed and mutually agreed in the RH sub-cluster meetings, based on the situational analysis.

Gaps we identified in the response mostly relate to the emergency reproductive health kits. Few ERH kits had been pre-positioned. Re-establishment and continuation of essential RH services in some sites were delayed because of issues related to procuring and transporting the kits. Moreover, although the kits were distributed following an orientation programme on their content and use, additional training to peripheral health facilities staff would have been beneficial. Another gap was the lack of availability of country contextualised guidelines, although global guidelines were available. We also report the lack of revolving emergency funds available at the district or health facility level to facilitate transportation of sick or injured people or women with obstetric complications.

Based on lessons learned from this case study, we offer 10 recommendations for an effective SRH response to women’s and adolescents’ needs in future disaster response:

Prioritise SRH issues and needs in disaster preparedness plans and contingency plans for health; among other priorities, preparedness activities should address the development of rosters of health workers trained on SRH services for emergencies, including GBV prevention and care, as well as the establishment of revolving emergency funds at all levels of the response structure.

Immediately after a disaster, formalise a RH sub-cluster, under the Health Cluster, with strong linkages with other response clusters, such as the protection cluster for the response to gender-based violence.

Estimate the immediate SRH needs using the MISP calculator but plan a subsequent needs assessment for intermediate and recovery interventions.

Protect and address the basic and psychosocial needs of SRH health workers who survived the disaster, to help them sustain the trauma and stress, and resume their services.

Conduct outreach RH camps to deliver services to women in remote or difficult to access areas or sheltered in temporary camps, to help them overcome their challenges in accessing health facilities.

Include gender-based violence prevention, screening, management and referral programmes into the response, as gender-based violence, including trafficking and abuse, increases in post-disaster situations and is often under-reported.

Establish female-friendly spaces and transition homes to provide a safe, temporary shelter to pregnant and postnatal mothers and their infants and secure their access to sexual and reproductive health care.

Address the SRH needs of adolescents, including their protection against abuse, trafficking, substance abuse and their need for availability and disposal of menstrual management products; engage adolescents in the interventions, such as in the setting up of adolescent-friendly corners in the RH camps.

Establish reporting, monitoring and evaluation mechanisms of the response to fulfil accountability and establish a comprehensive 4W (who, what, where and when) to avoid duplication of activities.

As part of preparedness activities: pre-position ERH kits with adapted communication material, plan for the replenishment of these kits once distributed, and monitor their use in the affected communities.

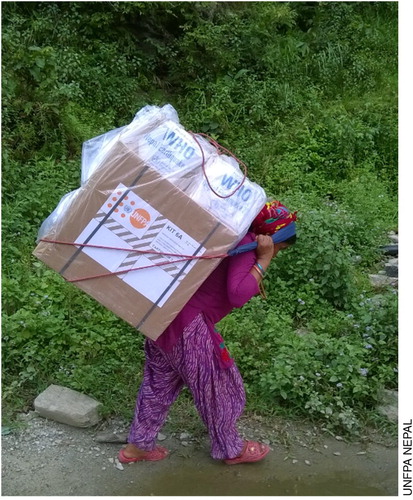

Transporting medical supplies following the 2015 earthquake in Nepal

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Bobby Rawal Basnet, Hari Karki and Manju Karmacharya from UNFPA, as well as Laxmi Tamang from MIDSON, Zainab Naimy and Sarita Pradhan, for their inputs during the preparation of this manuscript, or their participation in the reproductive health response to the Nepal Earthquake 2015. The MIDSON acknowledges the organisation Direct Relief for the provision of midwifery kits.

Disclosure Statement

This case study presents the humanitarian response to the sexual and reproductive health needs of the population of Nepal affected by the massive earthquake of 2015. It reflects the view of the authors and does not pretend to provide a comprehensive picture of the response by every stakeholder involved in SRH programs at that time.

ORCID

Reuben Samuel http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6674-6401

Sophie Goyet http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1835-4478

Notes

* Hub hospitals are designated lead hospitals prepared to ensure the coordination of the victims’ management in their respective areas, using their own facilities/staff/resources and those of their satellite hospitals, which are the private and public hospitals with >50 beds operating in those specific areas.

References

- New Delhi: World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Nepal Earthquake 2015: an insight into risks – a vision for resilience. 2016. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/entity/emergencies/documents/nepal-earthquake-a-vision-for-resilience.pdf?ua=1

- Government of Nepal, National Planning Commission Secretariat & Central Bureau of Statistics. Nepal population projection 2011-2031. 2014 [cited 2017 April 17]. Available from: http://cbs.gov.np/image/data/Population/Population%20projection%202011-2031/PopulationProjection2011-2031.pdf.

- Raj Upreti S. Overview of health impact and health response. In: Lessons learnt conference: health sector response to Nepal earthquake 2015. Kathmandu, Nepal: Government of Nepal, Ministry of Health, Curative Service Division; 2016.

- Nepal Earthquake 2015, Post Disaster Needs Assessment. Vol.B: Sector Reports. 2015 [cited 2017 Feb 23]. Available from: http://nepal.unfpa.org/sites/asiapacific/files/pub-pdf/PDNA_volume_BFinalVersion.pdf.

- WHO. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015. WHO [cited 2016 Sept 2016]. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/maternal-mortality-2015/en/.

- UNFPA Nepal. Nepal earthquake has affected 1.4 million women of reproductive age including 93,000 pregnant [cited 2017 April 17]. Available from: http://nepal.unfpa.org/en/news/nepal-earthquake-has-affected-14-million-women-reproductive-age-including-93000-pregnant.

- UNFPA. Dignity First: UNFPA Nepal 12 month earthquake report. 2016 [cited 2017 April 17]. Available from: http://un.org.np/sites/default/files/EQ%20REPORT_Final_2.pdf.

- Inter-Agency Working Group on reproductive health in crisis. MISP Calculators – Inter-Agency Working Group. Welcome to the Inter-agency Working Group (IAWG). [cited 2017 April 17]. Available from: http://iawg.net/resource/misp-rh-kit-calculators/.

- Singh DR. Medical interventions. In: Lessons learnt conference: health sector response to Nepal earthquake 2015. Kathmandu, Nepal: Curative Service Division, Ministry of Health, Government of Nepal; 2016.

- Gyawali B, Keeling J, Kallestrup P. Human trafficking in Nepal: post-earthquake risk and response. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2016. 1–2. DOI:10.1017/dmp.2016.121.

- The Government of Nepal, Ministry of Home Affairs. National Disaster Response Framework; 2013 [cited 2017 May 5]. Available from: http://www.un.org.np/sites/default/files/NDRF_English%20version_July-2013.pdf.

- Ministry of Health, Government of Nepal. Health Sector Plan for Disaster Response, 2071; 2014. [cited 2017 Nov 21]. Available from: http://www.flagship2.nrrc.org.np/sites/default/files/knowledge/Health%20Sector%20NDRF%202014.pdf

- Chaudhary P. Post-earthquake immediate response and recovery plan for Maternal and Newborn services. Kathmandu, Nepal: Family Health Division, Direction of Health Services, Ministry of Health; 2015

- Women’s Refugee Commission. Evaluation of the MISP for Reproductive Health Services in Post-earthquake Nepal. 2016 [cited 2017 April 18]. Available from: http://nepal.unfpa.org/en/publications/minimum-initial-service-package-reproductive-health-post-earthquake-nepal.

- UNFPA. Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for Reproductive Health; 2015 [cited 2017 May 4]. Available from: http://nepal.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/MISP-Cheat-Sheet.pdf.

- Government of Nepal, National Planning Commission. Nepal Earthquake 2015, Post Disaster Needs Assessment. Vol. A: Key Findings; 2015. [cited 2017 Feb 23]. Available from: http://npc.gov.np/images/category/PDNA_Volume_A.pdf

- Thakur N, Pradhan LM, Adhikari S, et al. Provision of comprehensive reproductive health services to the women in immediate post-earthquake situation through delivering emergency life-saving reproductive health supplies. In: 2nd National Midwifery conference. Kathmandu, Nepal: MIDSON; 2016.

- Karmacharya M, Pradhan LM, Basnet B, et al. Implementing Minimal Initial Service Package incorporating adolescent Sexual and Reproductive health services in emergencies in Nepal. In: 2nd National Midwifery conference. Kathmandu, Nepal; 2016

- Karki H, Pant S, Dahal S, et al. Operation of female friendly spaces for prevention and response to gender based violence in emergencies in Nepal. In: 2nd National Midwifery conference. Kathmandu, Nepal: MIDSON; 2016.

- UNFPA – United Nations Population Fund. Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings [cited 2017 May 9]. Available at: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/adolescent-sexual-and-reproductive-health-toolkit-humanitarian-settings.

- Subedi M. Uterine prolapse, mobile camp approach and body politics in Nepal. Dhaulagiri J Sociol Anthropol. 2011;4:21–40.