Abstract

While there are a growing number of interventions and evaluations of programmes aimed at changing gender norms and violence against women and girls, there remains a dearth of documentation outlining the challenges faced in conducting these interventions and evaluations, particularly in traditional and low literacy settings. The Do Kadam Barabari Ki Ore (Two Steps Towards Equality) programme sought to understand what works to prevent violence against women and girls in Bihar, India. This paper draws insights from process evaluation data. It describes promising features and challenges of implementation, and characteristics which weaken the potential effects of complex, community based, social sector programmes that aim to change deeply entrenched gender power hierarchies. We drew on the Medical Research Council framework for process evaluation in analysing our process evaluation data, and focus on mechanisms of impact, and factors inhibiting programme success, including contextual and implementation challenges. The paper also outlines measures that may help overcome observed challenges and areas that require modifications and/or further investigation. The programme experienced several challenges. These included contextual issues, such as the lack of leadership skills of those delivering the intervention and the gap between expected responsibilities and activities of government platforms and reality. Implementation challenges were encountered in reaching men and boys, younger women and the community at large and ensuring their regular attendance; and in maintaining the fidelity of the intervention activities. Our insights call for an evidence-supported dialogue on these challenges and how best to anticipate and address them.

Résumé

Si un nombre croissant d’interventions et d’évaluations de programmes visent à changer les normes de genre et lutter contre la violence à l’égard des femmes et des filles, la documentation qui met en évidence les défis à relever pour mener ces interventions et évaluations reste rare, en particulier dans les environnements traditionnels et peu alphabétisés. Le programme Do Kadam Barabari Ki Ore (Deux pas vers l’égalité) souhaitait comprendre quelles mesures fonctionnent pour prévenir la violence contre les femmes et les filles au Bihar, Inde. Cet article tire des enseignements des données de l’évaluation du processus. Il décrit les éléments prometteurs et les écueils de la mise en œuvre, ainsi que les caractéristiques qui affaiblissent les effets potentiels de programmes communautaires complexes du secteur social qui ont pour but de changer des hiérarchies de pouvoir sexospécifiques profondément enracinées. Nous nous sommes fondés sur le cadre du MRC pour l’évaluation du processus lors de l’analyse de nos données sur l’évaluation du processus et nous sommes centrés sur les mécanismes de l’impact, ainsi que sur les facteurs qui inhibent le succès du programme, notamment les difficultés contextuelles et de mise en œuvre. L’article souligne également les mesures susceptibles d’aider à surmonter les difficultés observées et les domaines qui requièrent des modifications et/ou des recherches plus approfondies. Le programme s’est heurté à plusieurs obstacles, notamment de nature contextuelle, comme le manque d’aptitude au leadership chez les personnes réalisant l’intervention et l’écart entre les responsabilités et les activités attendues des plateformes gouvernementales et la réalité. S’agissant de la mise en œuvre, des difficultés ont été rencontrées pour atteindre les hommes et les garçons, les plus jeunes femmes et la communauté dans son ensemble, de même que pour garantir leur fréquentation régulière ; et aussi pour maintenir la fidélité des activités d’intervention. Nos conclusions vont dans le sens d’un dialogue étayé par les données factuelles sur ces difficultés et sur la meilleure façon de les prévoir et de s’y attaquer.

Resumen

Aunque existe un creciente número de intervenciones y evaluaciones de programas que procuran cambiar las normas de género y la violencia contra mujeres y niñas, continúa habiendo escasez de documentación sobre los retos enfrentados para llevar a cabo estas intervenciones y evaluaciones, en particular en entornos tradicionales y con bajas tasas de alfabetización.

El programa Do Kadam Barabari Ki Ore (Dos pasos hacia la igualdad) buscó entender qué funciona para prevenir la violencia contra mujeres y niñas en Bihar, India. Este artículo extrae ideas de los datos de evaluación del proceso. Describe características prometedoras y los retos de la ejecución, así como características que debilitan los posibles efectos de complejos programas communitarios del sector social que procuran cambiar jerarquías de poder de género profundamente arraigadas. Nos basamos en el marco MRC de evaluación del proceso para analizar nuestros datos de la evaluación del proceso y centrarnos en los mecanismos de impacto y en los factores que inhiben el éxito del programa, incluidos los retos relacionados con el contexto y la ejecución. El artículo también resume las medidas que podrían ayudar a superar los retos observados y las áreas que necesitan modificaciones y/o más investigación.

El programa enfrentó varios retos, entre ellos problemas contextuales, como la falta de habilidades de liderazgo de las personas a cargo de la ejecución y la brecha entre las responsabilidades y actividades previstas de las plataformas gubernamentales y la realidad. Se enfrentaron retos de ejecución para llegar a los hombres y niños, a las mujeres jóvenes y a la comunidad en general, para asegurar su asistencia habitual y para mantener la fidelidad de las actividades de la intervención. Nuestras percepciones recomiendan un diálogo apoyado por evidencia acerca de estos retos y la mejor manera de preverlos y abordarlos.

1. Introduction

India has a range of policies and programmes to empower women and reduce violence. Yet, in 2015–2016, 29% of women aged 15–49 years experienced physical or sexual violence within marriage.Citation1 A key challenge is the dearth of evidence on what works and what does not work to change notions of masculinity and femininity, reverse social norms that condone marital violence, and reduce women’s experience of intimate partner violence.

The Population Council, together with partners, the Centre for Catalysing Change and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and with support from UKaid, implemented and evaluated a package of interventions to better understand what works to prevent violence against women and girls in Bihar, incorporating evidence-based best practices from India and globally.

Our programme, known as Do Kadam Barabari Ki Ore (Two Steps Towards Equality), was guided by Heise’s revised ecological framework.Citation2 Factors relating to the woman that have been consistently shown across studies and settings to increase the risk of victimisation include: attitudes justifying non-egalitarian gender roles and violence against women; and lack of social support, agency, access to resources, and participation in groups. Other factors relate to couple (relationship) and male characteristics, including men’s sense of entitlement to perpetrate violence, poor spousal communication, and non-egalitarian decision-making. At the community level, these include norms that condone violence against women, norms linking male honour to female purity, reluctance to share intimate family matters outside the home, and conversely, reluctance to intervene in cases of marital violence.Citation2 Our programme comprised four interventions that targeted these factors, particularly those identified as amenable to intervention.

Drawing on process evaluation data, this paper describes the mechanisms through which the Do Kadam programme brought about change in outcomes that it sought to affect. Challenges that inhibited success are also described. Our findings highlight challenges of implementation, and characteristics that weaken the potential effects of complex, community based, social sector programmes that change deeply entrenched gender power hierarchies. In so doing, the paper contributes to addressing the dearth of documentation outlining practical challenges faced in conducting interventions and evaluations, particularly in traditional and low literacy settings such as rural Bihar.

2. Setting: Bihar and the Do Kadam programme

Bihar is one of India’s least developed states, with low levels of female literacy and limited female agency. Large proportions of women and men express gender inegalitarian attitudes and condone the perpetration of violence against women in marriage (). In India, Bihar has the highest proportion of women experiencing marital violence. The availability of services and reach of entitlements are compromised in the state. However, there exist a number of programmes implemented by state and national governments that focus on, for example, health and family welfare, women and child development, or local self-government whose mandate encompasses reducing violence against women. These programmes are ideally placed to replicate at scale successful lessons from violence prevention projects, such as Do Kadam.Citation3–5

Table 1. Selected socio-demographic indicators, Bihar and India, 2010–2016.

The goal of the Do Kadam programme was to build the evidence base on what may work to prevent violence against women and girls in Bihar. Building upon the insights of our conceptual framework, we argue that skilled and supported facilitators – peer leaders, elected representatives, and front line workers – can raise awareness about women’s rights, change traditional notions of masculinity and female subordination, and enhance women’s agency. Facilitators may also build support systems that enable those at risk of violence to seek help and those who observe violent incidents to intervene to stop the incident. The perpetration or experience of violence and alcohol abuse could thereby be reduced. Our interventions thus aimed to (a) change attitudes towards violence; (b) promote women’s agency and awareness of rights; (c) build support networks for women; (d) encourage intervention to stop incidents of violence; (e) raise awareness of the law and services for women in distress; and (f) thereby, reduce the experience (women) and perpetration (men) of violence against women and girls. Specific objectives varied, as described below and in . At the same time, the objective was to implement potentially scalable interventions for incorporation into regular public sector programmes.

Table 2. Descriptions of interventions implemented under the Do Kadam Programme.

3. Intervention design, evaluation design, and effects

The four interventions focused on primary and secondary prevention. They were conducted in two districts of Bihar, namely Nawada or Patna. Each intervention was implemented independently, located in a separate geographic area, with no overlap.

The programme was initiated with a year-long inception phase in which researchers sought to identify, through a synthesis of literature, field assessments, and a qualitative field investigation,Citation14 appropriate interventions that could be implemented through public sector platforms. Based on insights thus generated, we decided to focus on boys and young men, married women and men, frontline workers (FLW)Footnote*, locally elected representatives and communities more generally. We based two of our projects on other studies conducted in India and elsewhere that demonstrated solid evidence: working with adolescent boys and young men using gender transformative group learning approaches (BOYS),Citation15–18 and working with women’s self-help empowerment groups (SHG).Citation19–22

Our third project, with the Panchayati Raj Institute (PRI), drew on sparser evidence suggesting that trained change agents may effectively change attitudes and behaviours related to violence against women and misuse of alcohol.Citation2,Citation23–25 We adapted elements from these programmes to train locally elected Panchayati Raj representatives. They acted as change agents to reduce alcohol misuse and to engender attitudes denouncing male entitlement and the acceptability of marital violence among married men and women in their communities. Our fourth intervention with FLW adapted programmes that used a screening tool on women seeking care (for any reason) from a health facility.Citation26,Citation27 We supported FLW to conduct the screening within women’s homes. With an eye to scale-up, each of these projects was housed within a government platform and required the cooperation of various departments of the Government of Bihar ().

Each intervention was developed independently, keeping in mind the preferences and interests of the target group, and as such, each intervention adopted different approaches, curricula, and activities. The BOYS project adopted a two-pronged approach that provided cricket coaching together with life skills education. The SHG project sought to empower members financially and in terms of resisting violence perpetrated against them and others. Both projects were delivered by group-based peer mentors, selected for their leadership skills, who underwent extensive capacity building before and during the intervention, and were supported by locally appointed project staff members. In the PRI project, locally elected representatives underwent regular capacity building sessions in which they prepared for the events they would transact at the community level; in turn, they conducted monthly community events and made efforts to intervene in incidents of violence that came to their notice. The FLW project sensitised and trained FLW in how to administer the Abuse Assessment Screen, a screening tool, in a non-threatening way. In routine home visits, FLW then used the tool and provided basic counselling, support, and referral as appropriate. Although the curriculum used in all projects contained common themes, others were tailored to each target group (). In all four projects, community-wide events such as street plays were held to sensitise communities more generally about matters related to violence against women and girls.

Evaluation designs differed (), taking into consideration the target group addressed, the strength of available evidence and the evaluation questions. Where strong global evidence and design precedents existed (BOYS, SHG), we opted to use cluster randomised trials. Where these did not exist, we opted for a quasi-experimental design (PRI), and a pre–post design with panel surveys (FLW). We assessed project acceptability at the endline survey and included in-depth interviews with those participating in, and/or delivering interventions and services. The Population Council’s Institutional Review Board approved the protocol for all four studies.

Most participants in each of the four groups found the intervention useful and acceptable. Even so, attendance varied. For example, in the SHG project, while 82% of SHG members attended sessions regularly, just 20% of husbands did so. Although 94% of husbands owned a mobile phone, just 38% had listened to more than 5 of the 24 messages delivered, using an interactive voice response system (IVRS). In the BOYS project, only 39% participated regularly in the gender transformative sessions and 38% in the cricket coaching sessions. In the PRI project, 42% of men and 32% of women in the community had attended one event organised by their elected representative.

Effects of the four presentations are summarised in . They highlight that attitudes about gender roles and acceptability of gender-based violence were significantly affected in programmes that worked directly with women SHG members and boys (BOYS, SHG), but not in those addressed more generally during community-level meetings and events (SHG, PRI). Agency (decision-making, freedom of movement, financial literacy, control over economic resources) increased significantly among women in one programme (SHG). Awareness of women’s rights and available services improved in all four interventions. Access to social support and willingness to seek help in case of violence, and/or to intervene to stop incidents of violence observed also improved in all four interventions. Despite these changes, effects on the perpetration and experience of violence were mixed, with, at best, no more than mildly significant effects observed among women (SHG, PRI, FLW), and with regard to stalking a girl, among boys (BOYS).

Table 3. Effects of interventions implemented under the Do Kadam Programme.

4. Methods of the process evaluation

Process evaluation was conducted throughout the programme and comprised several elements: (a) monthly monitoring reports on the reach of project activities; (b) monthly participatory observation visits in which principal investigators observed activities and discussed their observations with those delivering the intervention and those exposed to it; (c) longitudinal in-depth interviews with selected participants prior to the intervention, midway through and at its conclusion (BOYS, SHGs), or at two points (early in the intervention and at its conclusion) (PRI, FLW). During the interviews, participants also discussed aspects of the programme they perceived as most acceptable or important for fostering change.

The data generated allow us to reflect on mechanisms through which the programme produced changes and on challenges that inhibited programme success in certain domains. Within the partnership, the Centre for Catalysing Change (C3 India) took the lead in implementation and the Population Council in conducting the evaluation. Process documentation was conducted jointly.

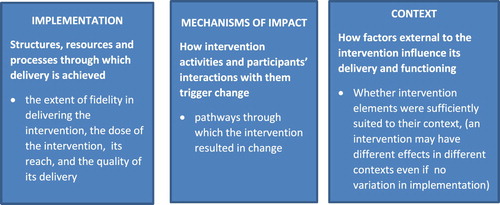

In analysing our process evaluation data, we drew on the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for process evaluation ().Citation28

5. Process evaluation findings

5.1. Mechanisms of impact: how did the programme produce change?

Our process evaluation data shed considerable light on the mechanisms through which the effects described above were achieved.

First, incorporating components into each intervention that were of interest to target groups (BOYS, SHG) was important. This responded to their needs, enabled attendance, and served as a means to instil changes in attitudes and practices. For example, survey findings revealed that women in SHGs appreciated the programme focus on financial literacy, access to banks, a savings orientation, and exposure to information about livelihood training opportunities, along with the gender transformative life skills education curriculum. More SHG members from intervention than control sites reported being informed about livelihood training (69–72% versus 11%), employment (38–46% versus 6%), and loan opportunities (59–65% versus 27%). More members in intervention groups were assisted in acquiring livelihood skills (13–14% versus 2%). Several women recognised the importance of economic empowerment for egalitarian gender relations. For example:

Yes, this should be started in the whole of Bihar so that people get to know about “Do Kadam Barabari”. Through this, women have savings of their own, and can earn as well. Husbands will help their wives in earning for themselves and becoming independent. Women will develop themselves, which will lead to less violence against them. [SHG]

This project will help to bring down physical and mental violence. … It teaches that women should be empowered and children should be educated. [SHG]

Boys commended the two-pronged life skills and sports intervention for its appealing format. It taught them to apply what they learned about team spirit and fair play to their lives and ingrained in them the importance of intervening to stop violence:

I liked it because earlier when we lost a game we would accuse the winning team of cheating or we would not talk to [them] … but we were taught that unity is important … whether we lose or win the match. We should hug the other team-mates, shake their hands and should say that in future we would try our best to perform. [BOYS]

Second, in all four interventions, participants highlighted that the curricula or activities to which they were exposed opened their horizons and provided them with the skills and information to interrupt the status quo, empowering them to negotiate and attain wanted outcomes without fear of violence:

Earlier in our village we did not have any discussion on domestic violence but now I also go and explain to a couple if there is violence … Now if I hear someone or see someone spreading rumours or exaggerating stories about girls then I talk to them and try to stop them … make them understand. [BOYS]

Before I used to get scared but not anymore. … attending the meetings has chased my fears away … . Before I wouldn’t dare to say anything to my husband if he was upset, but that changed after I joined the Do Kadam programme. They told me what to do and how and I did that, now he doesn’t give me any tension. [SHG]

I am not afraid of him since the day the sister came and gave me knowledge (from the brochure). So I keep making him afraid. I say “See, should I call on that number which is printed on the card? … [If you beat me] they will take me with them and then what will you eat?” [FLW]

There has been a lot of awareness among women through your programme. Which is why they have started coming to me, may be twenty women … this year. I solved their problems through the law or the panchayat … Yes, now if any woman has experienced violence, her family and husband are called and we punish them, financially or physically … scold them and make them understand. [PRI (Male, panchayat representative)]

Third, the findings underscore the importance of equipping those in authority (e.g. PRI representatives and frontline health workers) to incorporate messages on violence in their interactions with community members. It required changing their gender role attitudes, convincing them that their mandate included addressing gender-based violence and equipping them with the skills and empathy to overcome their inhibitions and take on a more proactive role in changing community norms and taking action against perpetrators. Findings showed a greater interaction between these change agents and community members by the end of the programme:

Yes, we organised sessions, discussed education, how to be free from alcohol, domestic violence. Both men and women participated, sometimes 20–25, not necessarily the same people. Afterwards we talked, people said what is the point of talk, why don’t we do something to stop selling alcohol. [Male, panchayat representative, PRI]

We were told about the ways through which to recognise victims of violence. We were also told that the victim will not tell us her story completely in the first meeting … .I learnt how to talk to them so that they reveal their experiences. … With the screening form, it is very easy to ask these questions. [ASHA, FLW]

Fourth, efforts to familiarise those delivering the interventions with available resources and linking them to services available to address violence against women also contributed to empowering those in authority and to strengthening their ability to support women in their communities, for example:

We were taken to the women’s police station, the women’s helpline etc. I knew about them before but had never been to any facility. [Male, panchayat representative, PRI]

Yes, through this, we understood that women can go to many people for help, like the village headmen, the ward member, or any person she trusts. Everything we learned was beneficial. I really liked the programme. … We didn’t even know what the women helpline was, and through this training we got to know that if a woman is facing torture, she should call the women helpline for protection. [FLW, (AWW)]

Despite these positive changes, attitudes remained inegalitarian among some intervention participants, with perpetration and experience of violence only mildly affected by our interventions. Challenges experienced that may explain these weaknesses are outlined below.

5.2. Factors inhibiting programme success: context

5.2.1. Gender inegalitarian setting

We recognised that communities accorded limited priority to addressing violence against women and women’s rights and entitlements, and that an exclusive focus on women’s rights would not be strategic. Hence our programme addressed violence through mechanisms that carried resonance among target populations: sports among boys; financial literacy and health-related home visits among women; and credibility of, and respect for, locally elected representatives among communities at large. Even so, change was slow in this hugely gender inegalitarian setting.

5.2.2. Implementation through existing platforms that are expected to, but do not prioritise gender issues and violence prevention

We believed that in order to inform scale-up, locating our projects in existing public sector platforms was preferable to a boutique programme where lessons learnt may not be applicable to a generalised programme. This meant that we did not have full control over the implementation of the project, the skills of those delivering it, or other systemic issues.

Moreover, gaps existed between the expected responsibilities and activities of each of these platforms and reality. For example, Nehru Yuvak Kendra Sangathan (NYKS) youth clubs of the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports are intended for boys and young men aged 13–35, yet the membership of NYKS clubs tended to concentrate on those aged 25 and above. Meetings of club members were held irregularly and social issues were rarely addressed. Likewise, many SHGs did not adhere to the procedures laid out for group meetings and savings activities by the SHG Federation. In the PRI project, while meetings were supposed to be held at regular intervals, several committees did not meet regularly. When they met, many members, especially women, did not attend. Complex caste, class, and gender dynamics interfered with the ability of PRI representatives to act jointly to ensure appropriate governance and financial allocations. Many representatives did not consider social issues a priority. While FLW have regular contact with married women, gender-based violence is not covered in the pre-service training of AWWs or auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs). There is a special module in the training of ASHAs that focuses on identifying and targeting women who are at risk of violence,Citation29 but many ASHAs have not been exposed to this module. The identification and support of women who have experienced violence explicitly are not included in the responsibilities of FLW, so FLW did not prioritise the activities proposed under the Do Kadam project. In the FLW project, challenges were experienced in facilitating a strong and supportive relationship between ASHAs and AWWs on the one hand, and ANMs on the other, because of competing demands on ANMs' time.

Delivering the intervention activities using these platforms required considerably more preparatory work and/or midcourse changes than originally intended. Our programme, therefore, built in three support mechanisms: capacity building of those delivering the projects, continuous mentorship by project representatives, and efforts to build linkages to available public sector services. For example, we ran a special membership drive before starting the NYKS intervention to inform boys, young men and their parents about the eligibility for membership in NYKS clubs. We made efforts in the SHG intervention to restore meeting schedules among SHG members, encourage better record-keeping, and instil a sense of ownership of their savings. In the PRI intervention, project teams worked to activate the panchayats, build the capacity of locally elected representatives, ensure regular attendance of all, raise interest among representatives, and engage them as a group. Despite these measures, our experience suggests that efforts to make existing platforms suitable for integrating the kind of violence prevention interventions advocated in the Do Kadam programme may not have been sufficient.

5.2.3. Addressing the weakness of referral services

Our project succeeded in reducing violence through individual intervention in incidents of violence against women and girls that programme participants witnessed or that came to their attention. However, referral of those in need to available services for women in distress was less successful. A major challenge was the perceived lack of responsiveness of services for women in distress. For example, SHG members and FLWs who had linked a few women with the helpline and other services reported that the helpline was unresponsive to the needs of women they referred there, or that services were not provided at locations convenient to women who faced difficulty in travelling away from their home. Women were reluctant to lodge complaints against their husband with the helpline or police for fear of adverse repercussions from their husband or marital family members.

5.3. Factors inhibiting programme success: implementation issues

5.3.1. Lack of leadership skills of those delivering the intervention

Building the leadership skills of those expected to deliver the intervention at the community level was a major challenge. For example, SHG members, PRI representatives, and FLWs displayed uneven levels of fluency in reading and writing, making it difficult to deliver gender transformative curricula or administer the screening tool. Indeed, in a few SHGs, particularly those in villages dominated by socially disadvantaged groups, there was not a single woman who was able to read the modules fluently. Many peer mentors in the NYKS and SHG projects, PRI representatives and FLWs held to the same traditional norms and attitudes about masculinity and marital violence as others in their community. Hence it was difficult to convince them that women should not tolerate marital violence or to enable them to overcome their hesitation about discussing topics such as gender discrimination and violence against women and girls with their peers and communities. Peer leaders from the NYKS clubs and SHGs, and even PRI representatives and FLWs lacked confidence and skills in public speaking, and in organising and leading meetings and other public events.

To strengthen leadership skills, pre-intervention workshops and regular refresher sessions were held for NYKS and SHG peer mentors, PRIs and FLWs. Workshops were tailored to address the needs of each group. Where literacy, numeracy or fluency in reading and writing were a concern (SHG), efforts were made to have the more literate supporting those less literate in acquiring reading, writing, and arithmetic skills. At the same time, in interactive sessions, training focused on enabling those delivering the intervention to question gendered norms, to understand women’s rights and their own responsibility in intervening to stop violence, to overcome inhibitions about speaking in a group forum, and to build communication and negotiation skills. We also encouraged project staff members to take on a more prominent role than originally intended in supporting those delivering each intervention to conduct sessions, narrate case stories, organise role play, and initiate discussion among participants. By the end of the intervention, many boys and young men, SHG members, PRI members and FLWs demonstrated greater confidence and skills in leading sessions. Even so, our experience suggests that the efforts to build capacity of those charged with imparting the intervention may not have been sufficient in time or content.

5.3.2. Reaching men and boys

This was a key challenge in the NYKS, SHG, and PRI interventions. Boys tended to be a mobile group and reported competing time commitments, commuting long distances to schools, colleges, or places of work outside their village or attending after-school coaching classes. Many husbands of SHG members had migrated away from their village or worked long hours. Others did not prioritise the goals of the intervention. Men in communities where the PRI project was implemented were less interested in attending events focused on violence and alcohol abuse than in those that discussed access to jobs, loans, and skill-building opportunities.

The SHG project made considerable efforts to encourage male participation, such as replacing husbands as peer mentors with staff conducting sessions; modifying session timing to suit majority preference; or using an IVRS to convey short messages to husbands over the phone. Despite these efforts, just a fifth of husbands reported regular attendance at sessions and few attended the (IVRS) calls. PRI project staff played a greater than expected role in accompanying members making home visits to inform men about upcoming meetings and to help them to stop incidents of violence in their constituencies.

Identifying forums for reaching men and boys remains challenging. Our NYKS project succeeded because it was conveyed through sports, a forum that appealed to and interested boys. In contrast, activities promoted for men in the SHG and PRI projects were not necessarily linked with activities that were valued by them and efforts to engage the husbands of SHG members failed.

5.3.3. Reaching younger women

Within the setting where Do Kadam interventions were implemented, recently married and young women were particularly secluded within the home while also at risk of violence. The need to reach them is large, but the means of reaching them is challenging. The project intended to screen and support women who experience violence. It explicitly concentrated on providing services to young women. Our findings reveal that although screening was conducted during home visits, privacy was not always assured and many young women hesitated to disclose their experiences. In the SHG project, since SHG membership excludes women under 18, younger women, notably newlywed women, a group that may be much in need of a group -based programme, may remain unreached.

5.3.4. Reaching communities at large

All four interventions aimed to influence communities through those directly affected by the intervention – in particular, NYKS club members, SHG members and their husbands, and PRI representatives. Meetings, street plays, competitions, public pledges, and other events were held, but were not enough to saturate their communities or to ensure regular exposure among those who attended these events. Over the course of the PRI project, only 50% of men and 33% of women from the community had attended at least one event organised by PRI members (on any subject). In the SHG project, even fewer attended a community meeting or street play organised by SHG members (17% of women and 9% of men and 31% of women and 18% of men had attended at least one meeting and one street play, respectively). While street plays, competitions, and other events were entertaining, they may not have engaged audiences in introspecting about violence-related norms and practices.

5.3.5. Maintaining the fidelity of the intervention activities

There was intra-project variation in the faithfulness with which curricula were imparted – for instance, in ensuring attendance, maintaining uniformity in the coverage and quality of delivery of the curriculum, and encouraging group participation and discussion. In all four intervention projects, project staff made efforts to attend sessions and events (and in the case of the FLW project, to accompany FLWs on regular field visits) to ensure fidelity, but this was not always possible and such intensive engagement is clearly not feasible in an upscaled programme.

5.3.6. Length of intervention

Our interventions ranged in effect from 6 to 12 months (in some, sessions were not held during festivals and exam time) – long enough to engage target populations and make a dent in norms and practices, but not so long as to risk dwindling interest and participation. We speculate that changes in attitudes and practices may have been greater, and peer mentors, locally elected representatives, and FLWs more confident about delivering interventions if the intervention had taken place over a longer time. Given deeply entrenched gender norms and limited communication and negotiation skills, a longer incubation period, in which leadership skills are nurtured and delivery of the interventions demonstrated in a hands-on manner, may offer a more compelling strategy for change.

6. Discussion

This paper has outlined challenges faced in conducting and evaluating interventions aimed at changing gender norms and violence against women and girls. Measures we believe may help overcome these challenges and areas for modifications and/or further investigation were also described. Many of the challenges we faced are likely to recur in most interventions and evaluations and may be useful to other programme implementers and evaluators.

Partnering with the public sector and working in public sector platforms has advantages. Their reach is wide. Most – for example, all the platforms with which we worked – are in principle committed to addressing social issues. Unfortunately, the reality is different, and social issues have thus far been given less priority than other activities such as sports (NYKS), infrastructure development (PRI), savings (SHGs) or pregnancy prevention and care (FLWs). Projects that seek to reorient the system to value its role as an agent of social change and to support the system in mentoring and empowering those in positions of authority clearly require a lengthy mentorship phase. A longer incubation or demonstration period, in which programme staff play a proactive role may allow community-based programme implementers to develop confidence and hands-on experience about imparting the intervention. During this phase, efforts could be made to hone leadership capacity, make platforms (such as SHGs, PRI community development activities, health outreach) accountable and ensure that they adhere to their basic responsibilities with regard to frequency of interactions and topics addressed. Those associated with delivering the intervention should be sensitised, empowered, and supported to clarify their own values.

With an eye to sustainability, programmes have tended to invest in and rely on community members with leadership potential to deliver intervention activities. While the situation is undoubtedly changing, our experience suggests that most of those selected lacked the self-confidence, communication skills, and willingness to advocate for changes that counter traditional norms. A lengthier and more intensive pre-intervention capacity building component is needed, that builds commitment to and skills in imparting the intervention. Greater self-confidence and more attention to gender transformative education should be built in those tasked with delivering the intervention, with a continuous mentoring mechanism over the initial period of programme implementation. However, questions arise about the best and most cost effective way to provide this support; and when and how to withdraw the mentorship arrangement.

Our experience calls for greater introspection into ways of modifying each model. Six thoughts stand out:

In interventions for boys, include a peer mentor who is somewhat older and commands more respect from boys than a boy of their own age.

Focus on making support services more accessible to women at community level. Provide outreach mechanisms to allay women’s concerns about travelling far to access services and to enable service providers to confront and counsel perpetrators without requiring the woman to file formal charges against a family member.

In the health arena, include the prevention of violence, as well as safety planning and referral strategies, in the regular responsibilities of ANMs.

Make programming for men more strategic, folding exposure to changing norms and practices into the activities of men’s pre-existing groups, such as a farmers’ group, income generation, and/or savings opportunities.

Exposure to individuals in positions of authority – police, lawyers, helpline protection officers, as well as block and district-level authorities – may also provide greater credibility to the messages transmitted.

At initial stages of implementation, give consideration to entry points and activities through which to approach the topic of inegalitarian gender roles and violence against women, including, for example: single-sex events; events directed at different groups, such as farmers or parents of school-going children; livelihoods opportunities and social sector programmes for which community members may be eligible; or venues such as meetings called by PRI members, or held by FLW, for women with young children, or members of various mandals.

Our experience also raises evaluation questions that need to be answered in future studies. Are attitudes sustained in the longer term? How likely is it that exposure to the intervention will have longer term effects, on boys’ perpetration of violence on their wife in the future? What is the ideal pathway to upscaling? Our projects – like most other pilots – have shown promise in a fairly idealised and resource-intensive situation. Even if we draw on our project experience and pare activities and curricula down to what is most promising and scalable, can the model be upscaled to district or state level or is there a need for an intermediary step? If so, far more attention needs to be paid to what those intermediate steps may entail. Indeed, in our projects, while statistical significance is established, the magnitude of change – for example, in percentages reporting a particular attitude or practice, and in the mean number of attitudes held or behaviours practiced – may be small, sometimes even in the range of 5–10 percentage points. Conventional wisdom would argue that these are strong effects and markers of a successful intervention, but policy-makers may question whether statistically significant small effects warrant investment in an upscaled programme. This is an intractable issue affecting policy decisions arising from evaluations of interventions, and more research and policy analyses are needed that offer rigorous insights into preconditions for upscaling.

In the long run, it is important to obtain commitment from, and transfer responsibility to, the district and block-level leadership of the NYKS, SHG federations, PRI department, health and family welfare department and integrated child development services (ICDS), as appropriate. There is a huge need for evidence-supported dialogue on the challenges faced in interventions addressing key social issues. This paper, using the Do Kadam experience, is one step towards synthesising these challenges, raising questions, and generating discussion about how best to anticipate and address them.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our co-investigators from the Population Council, the Centre for Catalyzing Change and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for their contributions to the design, implementation and analysis of data from the projects that we undertook under this programme. Komal Saxena was responsible for editorial matters and for preparing the manuscript for publication, and we would like to record our appreciation of her inputs.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

* Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) are trained village-level health workers who serve as a link between communities and the health system; and Anganwadi Workers (AWWs) who cater to pregnant and lactating women and children aged 0–6, provide nutritional supplementation, monitoring growth and providing early childhood education.

References

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS). National family health survey-4, 2015–2016, India factsheet. Mumbai: IIPS; 2017.

- Heise LL. What works to prevent partner violence? An evidence overview. Report for the UK Department for International Development; 2011.

- Women Development Corporation, Bihar. SHG formation nurturing. Bihar: Women Development Corporation; n.d. [cited 2017 Apr 27]. Available from: http://www.wdcbihar.org.in/SHG-Formation-Nurturing.aspx

- Government of Bihar. The Bihar Panchayat Raj Act, 2006 an act to replace the Bihar Panchayat Raj Act, 1993 as amended up to date. Bihar: Government of Bihar; n.d. [cited 2016 Apr 9]. Available from: http://www.panchayat.gov.in/documents/10198/350801/BiharPRAct_2006_English.pdf

- Government of India, Ministry of Youth Affairs & Sports, Nehru Yuva Kendra Sangathan. Annual Report 2010–11. New Delhi: Ministry of Youth Affairs & Sports, Nehru Yuva Kendra Sangathan; n.d. [cited 2016 Jan 5]. Available from: http://www.nyks.org/resources/pdf/ap201011.pdf

- Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India. Census of India 2011: primary census abstract, data highlights, India, series 1. New Delhi: Government of India; 2013.

- Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Religion PCA: Uttar Pradesh; 2015; [cited 2017 Apr 17]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/Religion_PCA.html

- Planning Commission. 2014. Report of the expert group to review the methodology for measurement of poverty. New Delhi: Planning Commission; [cited 2017 Apr 17]. Available from: http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/pov_rep0707.pdf

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National family health survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2017.

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Acharya R, Pandey N, et al. The effect of a gender transformative life skills education and sports-coaching programme on the attitudes and practices of adolescent boys and young men in Bihar. New Delhi: Population Council; 2017.

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Santhya KG, Acharya R, et al. Empowering women and addressing violence against them through self-help groups (SHGs). New Delhi: Population Council; 2017.

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Francis Zavier AJ, Santhya KG, et al. Modifying behaviours and notions of masculinity: effect of a programme led by locally elected representatives. New Delhi: Population Council; 2017.

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Santhya KG, Singh S, et al. Feasibility of screening and referring women experiencing marital violence by engaging frontline workers: evidence from rural Bihar. New Delhi: Population Council; 2017.

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Santhya KG, Sabarwal S. Gender-based violence: a qualitative exploration of norms, experiences and positive deviance. New Delhi: Population Council; 2013.

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. A cluster randomized-controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of stepping stones in preventing HIV infections and promoting safer sexual behaviour amongst youth in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa: trial design, methods and baseline findings. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(1):3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01530.x

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2008;337:a506. DOI:10.1136/bmj.a506.

- Achyut P, Bhatla N, Khandekar S, et al. Building support for gender equality among young adolescents in school: findings from Mumbai, India. New Delhi: ICRW; 2011.

- Das M, Ghosh S, Miller E, et al. Engaging coaches and athletes in fostering gender equity: findings from the Parivartan program in Mumbai, India. New Delhi: ICRW & Futures Without Violence; 2012.

- Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomized trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9551):1973–1983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4

- Kim J, Watts CH, Hargraeves J, et al. Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women’s empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1794–1802. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.095521

- Schuler SR, Hashemi SM, Riley AP, et al. Credit programs, patriarchy and men’s violence against women in rural Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(12):1729–1742. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00068-8

- Iyengar R, Ferrari G. Discussion sessions coupled with microfinancing may enhance the role of women in household decision-making in Burundi. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series No, 16902; 2011.

- Schensul SL, Saggurti N, Burleson J, et al. Community-level HIV/STI intervention and their impact on alcohol use in urban poor populations in India. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:S158–67. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9724-x

- Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Verma R, et al. Addressing gender dynamics and engaging men in HIV programs: lessons learned from Horizons research. Pub Health. 2010;125(2):282–292.

- Bradley JE, Bhattacharjee P, Banadakoppa R, et al. Evaluation of stepping stones as a tool for changing knowledge, attitudes and behaviours associated with gender, relationships and HIV risk in Karnataka, India. BMC Pub Health. 2011;11496. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-496

- McCloskey LA, Lichter E, Williams C, et al. Assessing intimate partner violence in health care settings leads to women’s receipt of interventions and improved health. Pub Health Rep. 2006;121(4):435–444. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100412

- McFarlane JM, Groff JY, O’Brien JA, et al. Secondary prevention of intimate partner violence: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res. 2006;55:52–61 [PMID: 16439929]. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200601000-00007

- Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015; 350(h1258). doi:10.1136/bmj.h1258.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW). Mobilising for action on violence against women: a handbook for ASHA. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; n.d.