Abstract

Human rights has been a vital tool in the global movement to reduce maternal mortality and to expose the disrespect and abuse that women experience during childbirth in facilities around the world. Yet to truly transform the relationship between women and providers, human rights-based approaches (HRBAs) will need to go beyond articulation, dissemination and even legal enforcement of formal norms of respectful maternity care. HRBAs must also develop a deeper, more nuanced understanding of how power operates in health systems under particular social, cultural and political conditions, if they are to effectively challenge settled patterns of behaviour and health systems structures that marginalise and abuse. In this paper, we report results from a mixed methods study in two hospitals in the Tanga region of Tanzania, comparing the prevalence of disrespect and abuse during childbirth as measured through observation by trained nurses stationed in maternity wards to prevalence as measured by the self-report upon discharge of the same women who had been observed. The huge disparity between these two measures (baseline: 69.83% observation vs. 9.91% self-report; endline: 32.91% observation vs. 7.59% self-report) suggests that disrespect and abuse is both internalised and normalised by users and providers alike. Building on qualitative research conducted in the study sites, we explore the mechanisms by which hidden and invisible power enforces internalisation and normalisation, and describe the implications for the development of HRBAs in maternal health.

Résumé

Les droits de l’homme sont un outil vital dans le mouvement mondial pour réduire la mortalité maternelle et exposer le manque de respect et la maltraitance que les femmes subissent pendant l’accouchement dans les établissements de santé autour du monde. Cependant, pour véritablement transformer les relations entre femmes et prestataires, les approches fondées sur les droits de l’homme devront aller au-delà de l’articulation, la dissémination et même l’application juridique des normes formelles de services de maternité respectueux. Pour véritablement remettre en question les modes établis de comportement et de structure des systèmes de santé qui marginalisent et maltraitent, les approches fondées sur les droits de l’homme doivent aussi parvenir à une compréhension plus profonde et plus nuancée du fonctionnement du pouvoir dans les systèmes de santé dans des conditions sociales, culturelles et politiques particulières. Cet article rend compte des résultats d’une étude avec des méthodes mixtes, réalisée dans deux hôpitaux de la région tanzanienne de Tanga, qui a comparé la prévalence du manque de respect et de la maltraitance pendant l’accouchement, mesurée par l’observation d’infirmières formées présentes dans les services de maternité, avec la prévalence mesurée par l’autodéclaration quand les mêmes femmes ayant fait l’objet de l’observation quittent l’hôpital. L’écart très important entre ces deux mesures (valeurs initiales : 69,83% pour les observations contre 9,91% pour les autodéclarations ; fin de l’étude : 34,17% pour les observations contre 6,83% pour les autodéclarations) donne à entendre que le manque de respect et la maltraitance sont assimilés et normalisés aussi bien par les utilisatrices que par les prestataires des services. Nous fondant sur une recherche qualitative menée dans les sites de l’étude, nous étudions les mécanismes par lesquels un pouvoir caché et invisible impose l’assimilation et la normalisation, et nous décrivons les conséquences pour la mise au point d’approches fondées sur les droits de l’homme dans la santé maternelle.

Resumen

Los derechos humanos han sido una herramienta vital en el movimiento mundial por reducir la mortalidad materna y exponer la falta de respeto y el maltrato que las mujeres enfrentan durante el parto en unidades de salud a nivel mundial. Sin embargo, para transformar verdaderamente la relación entre las mujeres y los prestadores de servicios, el enfoque basado en los derechos humanos (EBDH) debe trascender la articulación, difusión y aplicación legal de normas oficales relativas a la atención materna respetuosa. Además, para poder cuestionar eficazmente los patrones de comportamientos establecidos y las estructuras de los sistemas de salud que marginan y maltratan, el EBDH debe desarrollar una comprensión más profunda y más matizada de cómo el poder funciona en los sistemas de salud bajo condiciones sociales, culturales y políticas específicas. En este artículo, informamos los resultados de un estudio con métodos combinados realizado en dos hospitales en la región de Tanga de Tanzania, que comparó la prevalencia de falta de respeto y maltrato durante el parto medida en observaciones por enfermeras capacitadas en los pisos de maternidad con la prevalencia medida por el autoinforme de las mujeres que habían sido observadas en el momento de recibir alta. La gran disparidad entre estas dos medidas (línea de base: 69.83% observación vs. 9.91% autoinforme; línea final: 34.17% observación vs. 6.83% autoinforme) indica que la falta de respeto y el maltrato son internalizados y normalizados tanto por las usuarias como por los prestadores de servicios. Basándonos en los estudios de investigación cualitativa realizados en los lugares de estudio, exploramos los mecanismos por los cuales el poder oculto e invisible aplica la internalización y normalización, y describimos las implicaciones para el desarrollo de EBDH en la salud materna.

Introduction

Human rights has been a vital tool in repositioning maternal mortality and morbidity in the public imagination and on the public health agenda. After centuries in which death in pregnancy and childbirth was seen as a personal tragedy – a natural, if rare, consequence of women’s role in reproduction – human rights helped to redefine maternal mortality as a public health imperative, as a fundamentally social and political challenge that reflects deep social fractures and institutional frailties.

Human rights tools have been particularly effective in highlighting the long-simmering issue of poor interpersonal treatment of women during childbirth in facilities. Labelled as disrespect and abuse (D&A), mistreatment, or obstetric violence, the issue has recently emerged at the top of the global quality of care agenda and the broader reproductive justice movement as well. A coalition of NGOs and advocates has used human rights norms to articulate a Charter of the Universal Rights of Childbearing Women in an effort to set global standards of Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) grounded in existing law.Citation1 Human rights advocates have also done more formal legal analysis, showing how international human rights law can apply to the range of abusive practices described in the literature.Citation2 Some have initiated formal litigation in national court systems to demand redress in particular cases.Citation3

Yet true transformation in the relationship between women and providers of childbirth services cannot be compelled by the operation of law. It will also have to be built from the ground up through creative efforts to challenge settled patterns of behaviour and deeply entrenched health system structures that marginalise and abuse. To do that, human rights and RMC advocates need first to understand how power – especially “invisible” power – works in health systems.Citation4–6 They need to examine the ways in which hierarchies of power that permeate health systems and the marginalising, demeaning practices that go with those hierarchies are internalised, naturalised and/or normalised by patients and providers alike. With that empirical understanding as a foundation and human rights ideals as a guide, new approaches to social and institutional change can be created and implemented.

This paper is a modest contribution to that process. Here, we report results from Staha, an exploratory project in the rural Tanga region of Tanzania. Launching in 2010, it was among the first of the recent wave of initiatives to focus on disrespect and abuse,Footnote* a field that had no generally accepted definition of D&A, method to measure D&A, or tested interventions to address D&A. We consulted widely in Tanga, worked through a first definition, tried multiple approaches to measure prevalence, and used the refined conceptual understanding of D&A that was emerging from formative qualitative research and a baseline quantitative survey in Tanga to inform the participatory design of an intervention to be tested there.

In this paper, we compare two methods for measuring D&A and highlight the huge difference between the prevalence of D&A as measured by women’s self-report versus by third-party observation. We explore how this difference illuminates the ways that power works in the childbirth encounter and its implications for developing a human rights-based approach (HRBA) to maternal health.

Defining disrespect and abuse

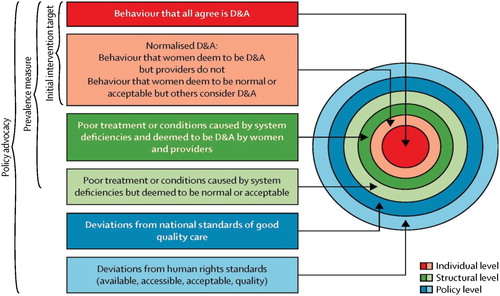

The Staha team, collaborating with a multi-disciplinary group from its sister project in Kenya, developed a definition of D&A to inform research, intervention and advocacy.Citation7 Footnote† This definition acknowledges two distinctly different approaches to defining D&A. The first turns on women’s own experience of D&A and credits their subjective feeling of being disrespected or humiliated, whether the source of that feeling is observable to outsiders or not. We called this the “experiential building blocks” of the definition, and they are best captured in the self-report measure. The second approach turns on the norms for RMC defined in law and policy, and regards deviation from the norms as a kind of D&A. We called this the “normative building blocks” of the definition, best captured in the third-party observation. Our definition included not only individual actions by health system actors that are experienced as or intended to be disrespectful or humiliating, but also structural conditions that create an environment that is in itself disrespectful and humiliating. We arranged these elements in the bull’s eye pattern shown in .

Figure 1. Defining disrespect and abuse of women in childbirth

Note: Reprinted from The Lancet, vol. 384, Freedman LP, Kruk ME. Disrespect and abuse of women in childbirth: challenging the global quality and accountability agendas. page e43. 2014, with permission from Elsevier.

Yet even this carefully parsed bull’s eye is just a heuristic. In fact, D&A in pregnancy and childbirth is a complex human experience, often interspersed with moments of kindness and compassion, and deeply embedded in the family, community and institutional power structures and social dynamics of any given setting. Childbirth and the conditions under which it happens reflect other important aspects of social change, including social signaling as women aspire to consolidate and convey some image of their own lives and selvesCitation12 – e.g. to be modern; to be well-off; to be strong; to be “good”. Childbirth and its conditions become a prism refracting histories of oppression and struggle, as is so clearly demonstrated by the birth justice movement in the United States, led by women of colour whose analysis tracks the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow lawsFootnote‡ into the current interactions with the state and other institutions around childbirth and motherhood.Citation13–15

In short, the quantitative measures reported in this paper only begin to hint at the many deeper dimensions of the phenomenon of D&A. Neither third-party observation nor women’s self-report should be understood as the “gold standard” for measuring the prevalence of D&A. As the comparisons between observation and self-report below imply, these are essentially measuring two different – but both relevant – aspects of the social relationships that constitute health system dynamics, rather than being two alternative ways to quantify one unified, sharply delineated thing called D&A.

The Staha intervention

The Staha intervention had two components: a six-month long participatory process involving community members, community leaders, and health system actors in Tanga to locally adapt and disseminate a client rights charter that articulated a local consensus about the standards of respectful care for facility-based childbirth; and a facility-based change process that used tools of quality improvement to implement specific changes in the maternity ward designed to realise the standards of the client charter. Previous papers provide a detailed description of the intervention and associated changes,Citation16,Citation17 showing a 66% reduced odds of a woman experiencing D&A during childbirth following the intervention.

Separately from the before-and-after survey at the intervention and comparison facilities, we also measured prevalence through observation by trained nurses stationed in the maternity ward, followed by an exit interview of the same women who had been observed. Those measurements, which are reported here, were not powered to detect the degree of change associated with the intervention. Rather, building on insights from our qualitative research, the comparison between observation and self-report at two time points in the two study facilities was undertaken to deepen our understanding of how power operates in the childbirth encounter.

Methods

Quantitative measures

Data were collected from two study facilities in the Tanga region of Tanzania, one randomly assigned to receive the intervention and one assigned as the comparison. Data were collected at two time points: at baseline from September–October 2012 and after the implementation of the study intervention from November–December 2015. Women were eligible for study inclusion if they were in active labour when they were admitted to the maternity ward of the study facilities and if they were 15 years of age or older.

At each data collection period, women who consented to participate were observed by nurse observers unaffiliated with the study facilities, from active labour to two hours postpartum. Observers had undergone a one-week training by the Staha team and an obstetrician-gynecologist, which included information on D&A, observation techniques, and the data collection tool. We then piloted the tool for one week in order for the observers to become oriented to the facility and the tools and to account for the Hawthorne effectFootnote§

Pairs of observers worked in three 8-hour shifts to ensure 24-hour coverage in the maternity ward. One observer was assigned to each study participant for up to eight hours, at which point another observer took over the observation, if applicable. Upon discharge from the health facility, these same women were approached by trained interviewers to participate in an exit interview, which were conducted in privacy in a tent set up outside the hospital but within the hospital compound. The interviews were performed in Swahili and were approximately 45 minutes in length. Women were given a bar of soap and a bottle of water for their participation in the study. All women provided written informed consent for the observation and the exit interview. The officer in charge of the facilities also gave written consent for the observations.

Observation and exit questionnaires contained the same 14 questions about D&A during labour and delivery (). During observations, observers recorded if any of these D&A events occurred and briefly described the incident and the context. In the exit interview, the same women were asked if they experienced any of the 14 events during labour and delivery. Each item was asked as a separate question and categorised as a dichotomous variable (experienced vs. not experienced). We defined “any disrespect and abuse” as the endorsement of (answering “yes” to) any of the D&A items. The questions were created and validated for the Tanzanian context and were based on Bowser and Hill’s categorisation of D&A events.Citation10

Table 1. Disrespect and abuse categories and actions included in observation and exit interview questionnaire

Statistical analysis

The observations and the exit interviews were matched by study ID. To account for the Hawthorne effect, we removed the first week of data from analysis.Citation18 We calculated the prevalence of the 14 D&A items and D&A for each measurement method by time period. As the main purpose of this paper is to compare self-report and observation rather than to measure the impact of the intervention, the analyses were performed across facilities.

First, to allow for more meaningful comparisons across measures, D&A items which were reported on observation for fewer than five women were eliminated from analysis. Second, to understand reporting trends, we calculated the ratio of D&A observed to women’s self-report. Third, we explored the agreement between the two methods by calculating the percent of participants who reported D&A on both measures, those who were observed to have experienced D&A only, and those who self-reported D&A only, separately for each time period. Fourth, to understand whether women’s characteristics may influence the propensity to report D&A, we used chi-square and t-tests, as appropriate, to compare demographic and delivery characteristics of those who had concordant D&A responses across the two measurement methods (either reported D&A on both measures or reported no D&A on both measures) to those that had discordant responses.

Data were missing for the D&A items for 3.3% of the baseline participants and 7.0% of the endline participants. The results of the complete case are presented here. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (College Station, TX, USA).

Qualitative data and analysis

Observers’ written descriptions of the D&A incident and context were put into a spreadsheet, organised by type of D&A. The descriptions were then reviewed to identify any patterns or recurring themes that might shed light on the actual norms operating in practice in the facilities.

The interpretation of the quantitative and descriptive data from the observation and self-report builds on a substantial base of qualitative research conducted in Tanga over the course of the project. At baseline in 2011, we conducted 11 focus group discussions in communities with women and men with children under one year, three focus group discussions with doctors, midwives and medical assistants working in facilities, and 60 key informant interviews with stakeholders from community to national level, all to explore the perceptions of D&A, its manifestations and drivers.Citation19 During the nine-month participatory design process to develop the intervention, we facilitated a series of eight workshops in communities and facilities in which findings from baseline research were discussed and collectively analysed. Further qualitative research was conducted throughout implementation to assess evolving perceptions of D&A.Citation20 Supplementary Table 1 provides more detail about the sample for focus group discussions, in-depth interviews and stakeholder meetings.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the IRBs of Columbia University, Ifakara Health Institute, and the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania.

Results

A total of 232 women at baseline and 237 women at endline participated in both the observation and the exit interview. Women at baseline and endline were similar on demographic and some delivery care characteristics. (). Most participants were aged 20–34 and for about 40% of the women, this was their first birth. A lower proportion of participants at baseline compared to endline were married and a higher proportion reported any complications during childbirth.

Table 2. Characteristics of participants at baseline (2012) and endline (2015) in two health faciliites in Tanga Region, Tanzania

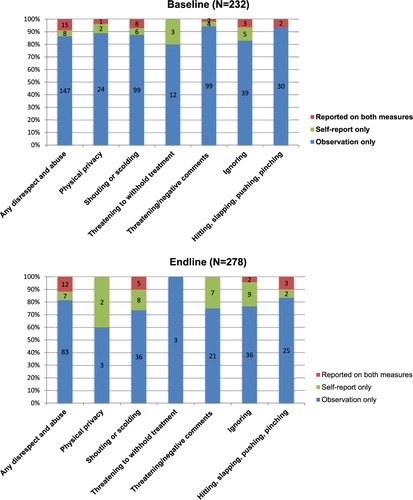

provides a comparison of the percent of each D&A item by measurement method by time period. For all D&A items, the observers reported more D&A than the women themselves. At baseline, across facilities, the prevalence of any observed D&A was 69.83% and on self-report, 9.91% (ratio: 7.05). At endline, the percent of any D&A reduced on both measures, with 32.91% observed and 7.59% self-reported (ratio: 4.34). The most reported item on both measures at both time periods was shouting or scolding ().

Table 3. Comparison of reports of disrespect and abuse on observation and self-report at baseline (2012) and at endline (2015) in two health facilities in Tanga Region, Tanzania

presents the agreement between reports of D&A from the two methods at baseline and at endline, respectively. Comparison of demographic and delivery characteristics between women with concordant measurements and those with discordant reports is shown in supplemental material (Supplementary Table 2).

There was little overlap between the observations and self-reports. At both time periods, the item with the most agreement between the two measures was shouting and scolding (agreement at baseline 7.08% vs endline 11.90%). The items with the least agreement were threatening to withhold treatment (0% agreement at baseline and endline), threatening or negative comments (agreement at baseline 1.90% vs endline 0%), and physical privacy (agreement at baseline 3.70% vs endline 0%). Overall, however, there was an increase in the agreement of reporting any D&A over time, from 8.82% at baseline to 12.94% at endline.

The descriptions of D&A events provided by the observers give a fuller sense of the D&A happening most often in the two facilities studied. Three scenarios stand out as relatively common. First, privacy violations. At baseline, although the physical organisation of the ward certainly made maintaining privacy difficult, the incident reports indicate that most violations were not merely the result of infrastructure constraints. Common privacy violations also included non-clinical staff, such as cleaners, or other patients’ relatives, moving through the room without regard to women’s physical exposure or to the labouring woman’s emotional vulnerability. Often women were transferred from room to room, wheeled through hallways without being covered.

“The nurse left the woman uncovered when she was delivering; also the door was open to the extent that when other people were passing they could see her (the delivering woman).”

If you continue shouting we will take you back without operating you to deliver your baby.

Lower down your waist so that I can examine you. I will slap you if you continue bothering me!

When the mother was delivering the baby and the baby’s head could be seen, she [the woman] closed her legs while shouting. She [the nurse] slapped her and pinched her thighs.

“You stupid; lie on your back so that the baby can descend,” she [the nurse] shouted at her at a very sharp tongue; she slapped her on her lap, and when the woman was giving birth the nurse slapped the mother on her face while telling her, “Push the baby, you will kill it, stop being stupid.”

“This woman! She acts as if this is her first pregnancy. Did you deliver previous pregnancies without labour pain?” The woman was not following the nurse’s instructions and she [the nurse] shouted at the woman and said, “You will let me know when you are ready, I am going to attend other women; as you can see I am all alone.” The nurse left; she went to dispense medicine to other patients.

When the woman was about to be taken to the theatre, the relative was asked if they have money to buy the materials needed. The relative said no. Then the nurse complained and said, “Now how will your patient be helped?”

Although similar kinds of D&A were observed at both baseline and endline, their prevalence declined substantially – by 50% – between the two-time points (baseline: 73.28% vs. endline: 35.86%) and the gap between observation and self-report narrowed (baseline ratio: 7.05 vs endline 4.34).

Discussion

In a study of 469 births in two hospitals in the Tanga region of Tanzania, we found that the prevalence of D&A as measured through third-party observation was dramatically higher than the prevalence of D&A measured through parturient women’s self-report (baseline: 70% vs. 10%; endline: 34% vs 7%). Moreover, the incidents that observers reported as D&A were largely not the same ones that women self-reported as D&A.

One reaction is to see the disparity as a definitional problem: whose view of D&A is “correct” or true? Another reaction is to see it as a measurement problem: are the instruments used insufficiently sensitive and specific to provide the true prevalence of D&A? Yet, a third reaction is to highlight the possible bias in D&A measurement: is there courtesy bias in self-report and recorder bias in observation? Or is the low prevalence of self-report of D&A due to fear of retaliation in a setting where there is little choice in hospital care? While there may be some truth to all of those points, they are not likely to explain fully the size of the gap between observation and self-report or the almost total lack of overlap in what incidents observers and women report as D&A.

We propose that the disparate prevalence measurements should be seen less as a contest between two ways of quantifying a single objective phenomenon and more as a red flag alerting us to a deeper, more challenging dynamic to be uncovered, analysed and addressed in efforts to build a HRBA to maternal health.Citation21 Our data support the growing understanding that women’s low self-report of D&A shows that their powerlessness to prevent or challenge D&A, perhaps even their expectation and acceptance that they will be subjected to D&A, are internalized; and that providers’ high propensity to commit these acts despite knowledge that they are being observed shows that D&A is normalized.

But what exactly are the mechanisms by which internalisation and normalisation happen? The key lies in understanding power and how it works in the encounters of women and health systems during childbirth in specific hospital settings as shaped by their specific social and political histories and dynamics. One useful framework for understanding the workings of power in health systems identifies three forms of power:Citation22,Citation23,Citation6

Visible power: Formal, observable forms of power, such as a government official’s power to promulgate a new rule or standard of care.

Hidden power: Power exercised behind the scenes, such as the ways that “street-level bureaucrats” – frontline workers – use their inherent discretionary power when implementing a law or regulation.Citation24

Invisible power: The power of “hegemonic norms and beliefs that secure consent to domination,”Citation25 such as the norms and ideologies that underlie a woman’s implicit acceptance of D&A as a natural part of the social world in which she exists.

The concept of invisible power is particularly useful for addressing women’s internalisation of D&A. While all these forms of power certainly exist on the provider side too, it is the exercise of hidden power that may best elucidate the normalisation of D&A within the maternity ward.

Hidden power in the maternity ward

A growing body of literature focuses on the gap between formal rules that govern the health system, and the actual behaviour of providers that regularly diverges from those rules.Citation26,Citation27 These discretionary exercises of power (breaking the rules) should not be understood as individual providers running amok. Rather their discretionary actions typically fall into specific patterns and routines detectable across the system – what Olivier de Sardan calls practical norms, “the various informal rules, tacit or latent, that underpin those practices of public actors which do not conform to formal professional or bureaucratic norms”.Citation28 It is in this full sense that D&A is normalised: it becomes both routine and unremarkable (normal) and a pattern of behaviour (a norm) that functions in practice, informally, to regulate the actions of health workers.

For example, physical abuse is certainly prohibited by professional ethical rules in Tanzania.Citation29 Yet, the observers reported and our qualitative data confirm that physically striking women during the second stage of labour – especially slapping on the inner thighs – had become an accepted way to deal with what providers perceive to be “non-compliant” behaviour. This exercise of hidden power over women at that most vulnerable moment in the delivery is often reinforced by verbally berating them with warnings that their behaviour (not obeying providers’ orders) will kill the baby. This combination of a specific form of physical abuse and specific trope of verbal abuse makes very clear whose view of “appropriate” birthing behaviour dominates and provides accepted boundaries in which to assert that domination. In other words, the operation of this practical norm – the disciplining of “non-compliant” patients – not only controls women’s behaviour, it regulates provider behaviour too. At times, providers were completely frank about this dynamic, as the norm slowly began to shift over the course of the Staha project:

I think they [incidents of bad language toward patients] have reduced … although sometimes they resulted due to poor cooperation from clients especially those who are giving birth for the first time and that normally upset the situation and they are forced to use power over them. (health facility manager)Citation20(p. 26)

Providers often appropriate the spaces of maternity wards by overtly using them for personal purposes, resulting in practices that diverge from formal rules and creating a setting conducive to the assertion of provider dominance. As d’Alessandro observed in her ethnographic study of poor infection control practices in hospitals in Niger, the introduction of social activities into technical work spaces privatises those spaces. She makes the trenchant point that when the hospital space is converted into providers’ social, privatised space, then “patients are perceived as intruders” making the hospital “fundamentally inhospitable.”Citation30

In the Staha intervention hospital, the first step taken to improve respectful care was to move the patient intake and discharge desk from an open area in the middle of the maternity ward to a private alcove where conversations could not be overheard. Although first conceived as a privacy intervention for patients, providers later acknowledged that this had other important effects on their own behaviour as well, taking them away from distractions of interactions with other staff and allowing them to focus more intently on the one-on-one communication with the patient. With the later addition of curtains placed between beds, the ward began to shift from a totally open space dominated by provider work and social routines to one with sheltered spaces individualised for patients, leading to a subtle but meaningful shift in a sense of whose needs the space was being organised to serve.Citation20

Space is just one aspect of the material conditions of a maternity ward that shape the interactions between providers and patients. Additionally, the deficits in infrastructure, supplies and equipment that plague many hospitals in low-income countries, including Tanzania, can by themselves create abusive conditions for women, as our bull’s eye definition recognises (). Equally important, providers regularly pointed to these work conditions as the explanation for aspects of their own behaviour that they recognised as D&A.

It is important to specify exactly how a deficient work environment translates into behaviours that are often described by researchers and by clients as individual “attitude” problems. As anthropologist Josiane Tantchou explains it in her study of hospitals in a remote and underserved region of northern Cameroon, when providers work in “unsuitable spaces that lack basic equipment and supplies … [it] engenders a permanent uncertainty,” making it impossible to follow rules and procedures that were designed for an idealised, well-stocked setting. Instead, to manage this uncertainty, health workers need to mobilise considerable intellectual resources to constantly anticipate needs and demands and to “translate” the resources they do have into improvised responses. She asserts that “altercations with users arise from this demanding and continuous process of translation and anticipation as well as the emotional, intellectual, and physical fatigue it causes.”Citation31

Yet simply ensuring adequate supplies or other elements of infrastructure is not likely to be enough, by itself, to create and maintain respectful care behaviour.Citation32 While these deficits define the immediate, stressful circumstances that providers cope with, “care” as provided in a maternity ward, is ultimately a far more complex phenomenon involving the interplay of people, places and things, all embedded in broader power dynamics. As explained by Tantchou, “[t]he materiality of care encompasses infrastructures, spatial organisation, equipment and supplies, income, and the ways professional status is managed – all of which are determined by history, broad economic and political forces, a specific position in medicoscapes … ”.Citation31(p. 3)

We see this dynamic play out in Tanga, where a commonly cited source of patient-provider conflict was the stock-outs of drugs that patients knew were supposed to be available free of charge. Our qualitative research revealed that patients believed providers were saving drugs for favored clients or manufacturing fake scarcity in order to profit personally. The RMC intervention chosen by the maternity ward staff in Tanga was to publicly post stock-outs on a daily basis in order to remove the suspicion of corruption or unfair treatment around this type of scarcity. There may not have been any better supply of drugs available, but the perception of D&A engendered by stock-outs was significantly reduced.

Yet stock-outs led to suspicion precisely because they played directly into a broader concern expressed widely by community members, that “favoritism” was rife in the system, such that those with kinship or other social connections to providers would get preferential treatment, including access to scarce commodities such as drugs. Such favoritism based on personal connections is arguably a different phenomenon from poor treatment or discrimination against disfavored or marginalised groups, as it is typically framed in human rights literature, although both may be considered unequal treatment in a legal sense – and both were reported in Tanga.

This kind of favoritism in health systems is widely reported in the literature on delivery of public services in low and middle-income countries and can be documented empirically as one of many practical norms that regulate the hidden, discretionary power of midwives and other providers in the maternity ward. Rejecting the explanation that midwives’ behaviour reflects aspects of an (imagined) traditional African culture, Olivier de Sardan explains this and other actual practices in maternity wards as a convergence of (1) a common bureaucratic culture rooted in colonial and (path-dependent) post-colonial dynamics that is shared by government bureaucracies across different sectors; (2) profession-specific culture such as that of midwifery; and (3) a site-specific culture.Citation28 The powerful convergence of these three influences results in a set of practical norms that encourage workers to see the maternity ward as their space and the anonymous client – the pregnant woman who has no pre-existing connection via kinship or other means to the health workers – as “a nuisance, an inferior and a victim all rolled into one”.Citation28(p. 418)

Hidden and invisible power resisted: unlocking agency, changing norms and reforming systems

The typical HRBA asserts that health systems are by and for the people. It elaborates entitlements based on human rights law and encourages users to demand fulfilment as a matter of right.Citation33,Citation34 But the global health literature rarely acknowledges how profoundly different this conception of the health facility is from the actual, hierarchical way that facilities have historically functioned. Moreover, there is only minimal attention to understanding the psychosocial processes that shape people’s stance when they encounter abusive or humiliating exercises of power in their interactions with social institutions including health systems. The fact that women self-report D&A at such a dramatically lower level than the third-party observers, and the lack of concordance in the specific events reported by each group, suggest that women’s expectation and acceptance of – perhaps their rationalisation of – D&A is deeply internalised. This is invisible power at work.

When the sway of hegemonic norms is deeply internalised, simple human rights awareness-raising programmes or pre-service RMC training modules are not likely to unlock agency for either patients or providers, even when they acknowledge their dislike of the behaviours in question.Citation35,Citation36 Staha interventions were designed to challenge existing formal and practical norms through the participatory charter adaptation process and to tackle concrete, tangible, material conditions of the care and work environment through quality improvement processes. These had promising results that are now being taken up, adapted and tested by government and NGOs around the country.

Recent research on invisible power in other areas of rights-based activism suggests potential new directions for RMC programs. For example, Jethro Pettit studied aid-supported democracy programmes that aimed to encourage active citizenship but routinely confronted “political cultures of passivity and compliance.” Contrary to the theories of change underlying many initiatives, he shows that people do not simply learn about their entitlements and then, as though living only in the moment, make a reasoned, calculated choice to act, to demand fulfillment of their rights. Rather, people’s past experience of poverty and exclusion – filtered through their identities of gender, sexuality, race, age, and class, and perpetuated by “patterns of patriarchy, patronage and clientism” – construct social boundaries that constrain their options for action. Drawing on Bourdieu, he coins the term “civic habitus” to describe “the tacit, rational collusion with socialized norms of power in order to survive and evade harm” that characterises the reluctance to engage in civic action so often seen in such democracy projects.Citation37

Intriguingly, and important for HRBAs, Pettit also draws insight from cognitive neuroscience to try to explain how invisible power and the habitus it shapes actually turns into physical, bodily expression, “a way of bearing one’s body, presenting it to others, moving it, making space for it” – essentially the observable choreography of D&A as clients and providers interact with one another. For our purposes, this turn to neuroscience and what neuroscientists call enactive or embodied cognition, is important for the way it sets the target of rights-based work in a realm that also operates beyond intellectual discourse. For rights activists it implies a need for more than persuasive argument, more than the mobilisation of data or cost–benefit analysis to make their case to the people whose rights are at stake.

There are other literatures and areas of activism that would surely generate additional insight on how to respond effectively to internalised powerlessness, including work on intimate partner violence, principles of trauma-informed care, and the Freire-inspired practice of conscientisation, to name a few. A full analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, but our point here is that to be effective, efforts to address D&A must go beyond the formal announcement and enforcement of respectful care norms. We need to bring a more nuanced, power-conscious and empirically driven understanding of the childbirth encounter to activism for change.

And, despite the profound effects of both internalisation of D&A by women and normalisation of D&A by providers, we must recognise that together, clients and providers remain the only true engines of transformative change in their own settings. The urgent challenge is to understand what conditions actually do unlock that potential, and to support the exercise of their agency – and then to get out of the way. The answer is likely to require not just a stock intervention, such as a patient charter or a maternal death review, but also very careful, sustained attention to the workings of power that must be persistently confronted during implementation.Citation16,Citation38 Without that, even the best-intentioned interventions end up succumbing to forces that keep the status quo in place.Citation38–40

Conclusion – rethinking HRBA

The enormous gap between women’s self-report of D&A and observers’ reports of D&A should serve as a caution. Formal norms, formal law, formal policies – perhaps even the formal conventions of public health research and programming – will struggle to touch in meaningful ways the workings of power that shape women’s experience in facility-based childbirth. This does not make human rights law or its global vision of dignity, non-discrimination and social justice irrelevant. In fact, given the anti-democratic trends surfacing in many parts of the world, the principle of universal human rights is arguably more relevant today than ever. But its cultural legitimacy – and so its power to generate change – in any given setting cannot be assumed; it must be actively built. That means a HRBA must be grounded in actual practical norms that can be identified empirically and its message must be vernacularised into a discourse that can connect effectively to the fears, hopes and aspirations of both women and providers. Perhaps most profoundly, an HRBA must nurture what Scott-Villiers and Oosterom identify as another form of invisible power: the “resisting imagination,” the power to imagine the world differently.Citation41

Supplementary Tables

Download MS Word (26.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Regional Administrative Secretary, the Regional Medical Officer and all Regional Health Management Team officials from Tanga region and the District Executive Directors, District Medical Officers and Council Health Management Teams of Muheza and Korogwe, for their support and guidance. We are grateful to the health facility in-charges and maternity ward staff from Muheza District Designated Hospital and Korogwe District Hospital who allocated precious time and energy to participate in this study. We extend our deep appreciation to the women and their families who participated in the study at such vulnerable and meaningful moments in their lives. Finally, we thank the many data collectors and research assistants who worked under difficult circumstances to collect and analyse the data, as well as Francesca Heintz for research support and Amy Manning for assistance in preparing the manuscript for publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Lynn P Freedman https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4288-605X

Stephanie A Kujawski http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7915-8553

Selemani Mbuyita http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2113-6137

August Kuwawenaruwa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8459-443X

Margaret E Kruk https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9549-8432

Kate Ramsey https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8784-0779

Godfrey Mbaruku https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5285-5877

Additional information

Funding

Notes

*The humanisation of childbirth movement, particularly active in Latin America starting in the 1990s, is a forerunner of the current (post-2010) wave of initiatives on disrespect and abuse and the global movement now coalescing around respectful maternity care.

†Every effort described in the peer-reviewed literature to measure D&A quantitatively (including ours) has used a typology of D&A, ideally adapted to and validated for the specific setting.Citation8,Citation9 However, such typologiesCitation10,Citation11 are not definitions. They list types of D&A, but they do not tell us the criteria that must be met in order for an event, interaction or condition to qualify and be counted as D&A.

‡“Jim Crow” refers to the laws and practices that enforced racial segregation in public places, primarily in the southern states of the United States, in the period between the abolition of slavery (mid-19th century) and the civil rights era (1960s).

§The possibility that providers’ awareness of being observed would itself change their behaviour.

References

- White Ribbon Alliance. Respectful maternity care: The Universal Rights of Childbearing Women. 2011. Available from: http://whiteribbonalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Final_RMC_Charter.pdf.

- Khosla R, Zampas C, Vogel JP, et al. International human rights and the mistreatment of women during childbirth. Health Hum Rights. 2016;18(2):131–143.

- Millicent Awuor Maimuna & Margaret Anyoso Oliele v. Attorney General and Others. Available from: https://www.reproductiverights.org/sites/crr.civicactions.net/files/documents/Judgment%20Petition%20No562%20of%202012%20Kenya%20detention%20case.pdf.

- Freedman LP. Using human rights in maternal mortality programs: from analysis to strategy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001 Oct;75(1):51–60. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11597619. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00473-8

- Veneklasen L. Last word – how does change happen. Development. 2006;49(1):155–161. Available from: http://www.palgrave-journals.com/doifinder/10.1057/palgrave.development.1100231.

- Gaventa J. Finding the spaces for change: a power analysis. IDS Bull. 2006;37(6):23–33. Available from: http://www.powercube.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/finding_spaces_for_change.pdf. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2006.tb00320.x

- Freedman LP, Ramsey K, Abuya T, et al. Defining disrespect and abuse of women in childbirth: a research, policy and rights agenda. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(12):915–917. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.137869

- Sando D, Ratcliffe H, Mcdonald K, et al. The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016: 1–10.

- Savage V, Castro A. Measuring mistreatment of women during childbirth: a review of terminology and methodological approaches. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):138, Available from: http://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/. doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0403-5

- Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth. Report of a landscape analysis; 2010. Available from: https://www.harpnet.org/resource/exploring-evidence-for-disrespect-and-abuse-in-facility-based-childbirth-report-of-a-landscape-analysis/.

- Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLOS Med. 2015;12(6):e1001847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847

- Mumtaz Z, Levay A, Bhatti A, et al. Signalling, status and inequities in maternal healthcare use in Punjab, Pakistan. Soc Sci Med. 2013;94:98–105. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23845659. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.013

- Roberts D. Killing the black body: Race, reproduction, and the meaning of liberty. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Penguin Random House.

- Ross LJ, Solinger R. Reproductive justice: An introduction. Oakland (CA): University of California Press; 2017.

- Black Mamas Matter Alliance. Available from: http://blackmamasmatter.org/.

- Kujawski SA, Freedman LP, Ramsey K, et al. Community and health system intervention to reduce disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Tanga Region, Tanzania: A comparative before-and-after study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(7):e1002341. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002341.

- Kujawski S, Mbaruku G, Freedman LP, et al. Association between disrespect and abuse during childbirth and women’s confidence in health facilities in Tanzania. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(10):2243–2250. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25990843. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1743-9

- Leonard K, Masatu MC. Outpatient process quality evaluation and the Hawthorne Effect. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(9):2330–2340. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.003

- Ramsey K. Power asymmetry at the point of care: A potential driver of disrespect and abuse. In Global maternal newborn health conference. Mexico City; 2015. Available from: https://cdn2.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2015/12/K-Ramsey-Staha-power-dynamics-GMNHC-2015.pdf.

- Ramsey K, Moyo W, Larsen A, et al. Staha project: building understanding of how to promote respectful and attentive care in Tanzania: implementation research report to USAID TRAction Project. New York (NY): Averting Maternal Death and Disability Program; 2016. Available from: https://www.mailman.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/pdf/staha_implementation_research_report_-_2016.03.12.pdf.

- Erdman JN. Bioethics, human rights, and childbirth. Heal Hum Rights J. 2015;17(1):43–51. doi: 10.2307/healhumarigh.17.1.43

- Lukes S. Power: a radical view. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 1974; Available from: http://voidnetwork.gr/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Power-A-Radical-View-Steven-Lukes.pdf.

- Veneklasen L, Miller V. A new weave of power, people & politics: the action guide for advocacy and citizen Participation Oklahoma City (OK): World Neighbors; 2002; Available from: https://justassociates.org/en/resources/new-weave-power-people-politics-action-guide-advocacy-and-citizen-participation.

- Erasmus E. The use of street-level bureaucracy theory in health policy analysis in low- and middle-income countries: a meta-ethnographic synthesis. Health Policy Plan. 2014 Nov 30;29(suppl 3):iii70–iii78. [cited 2014 Dec 1]. Available from: http://www.heapol.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu112

- Pettit J, Acosta AM. Power above and below the waterlin: bridging political economy and power analysis. IDS Bull. 2014;45(5):9–22. doi: 10.1111/1759-5436.12100

- Gilson L, Schneider H, Orgill M. Practice and power: a review and interpretive synthesis focused on the exercise of discretionary power in policy implementation by front-line providers and managers. Health Policy Plan. 2014 Nov 30;29(suppl 3):iii51–iii69. [cited 2014 Dec 1]. Available from: http://www.heapol.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu098

- Erasmus E, Gilson L. How to start thinking about investigating power in the organizational settings of policy implementation. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23(5):361–368. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn021

- Olivier de Sardan J-P. The delivery state in Africa . Interface bureaucrats, professional cultures and the bureaucratic mode of governance. In: Bierschenk T, Olivier de Sardan J-P, editors. States at work: Dynamics of African bureaucracies. Lieden: Brill; 2014.

- Nursing and Midwifery Act of 2017, Part VI, Disciplinary Provisions.

- d’Alessandro E. Human activities and microbial geographies. An anthropological approach to the risk of infections in west African hospitals. Soc Sci Med. 2015;136–137:64–72. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953615002981. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.016

- Tantchou JC. The materiality of care and nurses’ “Attitude Problem”. Sci Technol Human Values. 2018;43(2):270–301. doi: 10.1177/0162243917714868

- Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Tunçalp Ö, et al. Mistreatment of women during childbirth in Abuja, Nigeria: a qualitative study on perceptions and experiences of women and healthcare providers. Reprod Heal 2017 141. 2017;14(1):239–244. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10995-005-0037-z%0A; https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-016-0265-2.

- Gruskin S, Bogecho D, Ferguson L, et al. “Rights-based approaches” to health policies and programs: articulations, ambiguities and assessment. J Public Health Policy. 2010;31(2):129–145. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20535096.

- Gauri V, Gloppen S. Human rights-based approaches to development: concepts, evidence, and policy. Polity. 2012;44(4):485–503. doi: 10.1057/pol.2012.12

- George AS, Branchini C, Portela A, et al. Do interventions that promote awareness of rights increase use of maternity care services? A systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0138116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138116

- George AS, Branchini C. Principles and processes behind promoting awareness of rights for quality maternal care services: a synthesis of stakeholder experiences and implementation factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:264. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1446-x

- Pettit J. Why citizens don’t engage – power, poverty and civic habitus. IDS Bull. 2016;47(5):89–102. Available from: http://bulletin.ids.ac.uk/idsbo/article/view/2794/ONLINE%20ARTICLE doi: 10.19088/1968-2016.169

- Béhague DP, Kanhonou LG, Filippi V, et al. Pierre Bourdieu and transformative agency: a study of how patients in Benin negotiate blame and accountability in the context of severe obstetric events. Sociol Health Illn. 2008 May;30(4):489–510. [cited 2013 Feb 3]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18298632. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01070.x

- Joshi A, Houtzager PP. Widgets or watchdogs? Conceptual explorations in social accountability. Public Manag Rev. 2012;14(2):145–162. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2012.657837

- Schmitz HP, Mitchell GE. The other side of the coin: NGOs, rights-based approaches, and public administration. Public Adm Rev. 2016;76(2):252–262. doi: 10.1111/puar.12479

- Scott-Villiers P, Oosterom M. Introduction. Power, Poverty and Inequality. IDS Bull. 2016;47(5):1–10. Available from: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/123456789/12671/IDS_B47.5_10.190881968-2016.163.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.