Abstract

How rurality relates to women’s abortion decision-making in the United States remains largely unexplored in existing literature. The present study relies on qualitative methods to analyze rural women’s experiences related to pregnancy decision-making and pathways to abortion services in Central Appalachia. This analysis examines narratives from 31 participants who disclosed experiencing an unwanted pregnancy, including those who continued and terminated a pregnancy. Results suggest that women living in rural communities deal with unwanted pregnancy in three phases: (1) the simultaneous assessment of the acceptability of continuing the pregnancy and the acceptability of terminating the pregnancy, (2) deciding whether to seek services, and (3) navigating a pathway to service. Many participants who experience an unwanted pregnancy ultimately decide not to seek abortion services. When women living in rural communities assess their pregnancy as unacceptable but abortion services do not appear feasible to obtain, they adjust their emotional orientation towards continuing pregnancy, shifting the continuation of pregnancy to be an acceptable outcome. The framework developed via this analysis expands the binary constructs around abortion access – for example, decide to seek an abortion/decide not to seek an abortion, obtain abortion services/do not obtain abortion services – and critically captures the dynamic, often internal, calculations women make around unwanted pregnancy. It captures the experiences of rural women, a gap in the current literature.

Résumé

L’influence de la ruralité sur les décisions relatives à l’avortement aux États-Unis reste dans l’ensemble peu étudiée dans les publications existantes. La présente étude se fonde sur des méthodes qualitatives pour analyser le ressenti de femmes rurales pour des décisions relatives à la grossesse et aux parcours vers les services d’avortement dans la région des Appalaches centrales. Cette analyse examine les récits de 31 participantes qui ont révélé qu’elles avaient connu une grossesse non désirée, certaines ayant poursuivi la grossesse et d’autres l’ayant interrompue. Les résultats suggèrent que les femmes qui vivent dans des communautés rurales gèrent une grossesse non désirée en trois phases : 1) évaluer simultanément l’acceptabilité de la poursuite de la grossesse et l’acceptabilité de l’interruption de grossesse ; 2) décider si elles vont demander des services ; et 3) emprunter un parcours vers le service. Beaucoup de participantes qui font face à une grossesse non désirée décident en fin de compte de ne pas demander de services d’avortement. Lorsque les femmes vivant dans des communautés rurales jugent que leur grossesse est inacceptable, mais qu’il ne semble pas possible d’obtenir des services d’avortement, elles ajustent leur orientation émotionnelle vers la poursuite de la grossesse et en font un résultat acceptable. Le cadre mis au point par le biais de cette analyse élargit les constructions binaires autour de l’accès à l’avortement - par exemple, décider de demander un avortement/décider de ne pas demander un avortement, obtenir des services d’avortement/ne pas obtenir des services d’avortement - et saisit les calculs dynamiques, souvent internes, que les femmes font autour d’une grossesse non désirée. Il fait comprendre l’expérience des femmes rurales, comblant ainsi une lacune des publications actuelles.

Resumen

En Estados Unidos, la relación entre ruralidad y la toma de decisiones de las mujeres respecto al aborto aún continúa muy poco explorada en la literatura disponible. El presente estudio depende de métodos cualitativos para analizar las experiencias de las mujeres rurales relacionadas con su toma de decisiones respecto al embarazo y las vías a los servicios de aborto en Appalachia central. Este análisis examina las narrativas de 31 participantes que divulgaron haber tenido un embarazo no deseado, incluidas las que continuaron o interrumpieron su embarazo. Los resultados indican que las mujeres que viven en comunidades rurales enfrentan un embarazo no deseado en tres fases: 1) evaluar simultáneamente la aceptabilidad de continuar el embarazo y la aceptabilidad de interrumpir el embarazo, 2) decidir si buscar o no servicios, y 3) navegar una vía al servicio. Muchas participantes que tienen un embarazo no deseado deciden no buscar servicios de aborto. Cuando las mujeres que viven en comunidades rurales evalúan su embarazo como inaceptable pero no les parece factible obtener servicios de aborto, ajustan su orientación emocional hacia continuar el embarazo y empiezan a percibir la continuación del embarazo como un resultado aceptable. El marco creado por medio de este análisis amplía los constructos binarios en torno al acceso a los servicios de aborto - por ejemplo, deciden buscar un aborto/deciden no buscar un aborto, obtienen servicios de aborto/no obtienen servicios de aborto- y captura críticamente los cálculos dinámicos, y a menudo internos, que hacen las mujeres con relación al embarazo no deseado. Captura las experiencias de las mujeres rurales, una brecha en la literatura actual.

Introduction

In 2009, an estimated 27.2 million women aged 18 and older lived in rural areas of the United States, representing 22.8% of all women.Citation1 When last calculated in 2000, the abortion rate among women living in metropolitan counties was still twice that of women in non-metropolitan counties (24 vs. 12 per 1000).Citation2 The driver of this difference in abortion rate is not known and the current literature offers no insight into rural women’s experiences related to unwanted pregnancy and abortion. It is unclear if a lack of need or unmet need for abortion services is the cause for different rates of service use. Against the larger backdrop of worse health and reproductive health outcomes compared to urban peers,Citation3 it is possible that the differential abortion rates are a result of inequity, not the absence of need. Existing literature indirectly suggests rural women’s ability to obtain abortion services is not equal to that of women in metropolitan areas. Women who obtained abortion services in 2008 and who reside in non-metropolitan counties were over fourteen times more likely to travel greater distances to the facility providing care as compared to their metropolitan-residing peers.Citation4 Women residing in non-metropolitan counties obtain abortion care at later gestational ages on average than those living in metropolitan counties, after controlling for individual-level factors such as age, race, education, and miles travelled to care.Citation5

Attention to this potential inequity is needed, starting with exploratory research. Women’s decision-making around abortion, and their experiences of seeking care, remain largely unexplored in rural communities. The present study addresses this gap, by investigating how, if at all, rurality relates to women’s decision-making around abortion services, and their ability to obtain these services. Developing this knowledge is essential to addressing potential disparities in access between women living in rural communities and women living in non-rural communities. It is especially relevant for women living in Central Appalachia, a region in which 42% of the population lives in rural communities, as compared to 20% of the population nationally.Citation6 In the context of a high-income country like the United States, this region, spanning multiple states, is characterised by a mountain range that renders some areas remote and has historically experienced disproportionate levels of economic distress. Those residing in Appalachia represent a highly visible rural population, who experience health disparities relative to the general U.S. population.Citation7

The present study, focused in the Central Appalachian region, relied on qualitative methods to explore the relationship between residing in a rural county, decision-making, and ability to obtain abortion services. Instead of recruiting exclusively at the point of abortion service provision, this study recruited participants in rural communities at multiple locations and includes the experiences of those who continued an unwanted pregnancy. By including women who had a range of pregnancy outcomes, this study captures the dynamics between living in a rural community and unwanted pregnancy without methodically restricting the range of experiences to those who ultimately obtained abortion services.

Pregnancy acceptability, help-seeking, and cognitive dissonance

Surveying existing literature, two distinct discourses may be relevant to abortion decision-making: pregnancy acceptability and help-seeking behaviours. In existing literature on women’s intentions as they relate to pregnancy, there is an emerging awareness that pregnancy prevention is a product of conscious and subconscious conflict.Citation8 The dominant discourse parses the frame of “unintended pregnancy” into “mistimed” and “unwanted.” At the same time, there is growing attention to the observation that emotions around a given pregnancy may be highly fluid.Citation9 A recent paradigm suggests that the construct of “pregnancy acceptability” is more salient than pre-pregnancy intentions. However, perceived ability to obtain abortion services is not specifically named as a driver of “pregnancy acceptability.” Instead, the perceived ability to obtain abortion services is identified as relevant only after a woman determines her pregnancy to be acceptable or unacceptable.Citation9

In examining the interplay between perceived access to abortion and pregnancy acceptability among rural women, cognitive dissonance theory may be relevant.Citation10 This theory states than an individual strives for “internal consistency” and experiences stress when holding contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values. Cognitive dissonance theory hypothesises that an individual seeks to resolve this internal conflict through a variety of means, one of which is changing one of the conflicting ideas. Perceived ability to obtain abortion services may be in tension with a desire to terminate a pregnancy, generating conflict.

Seeking to resolve internal conflict, the perceived feasibility of obtaining abortion services may influence whether a woman finds her pregnancy acceptable or unacceptable. A general model of help-seeking behaviours can expand what might otherwise be glossed over as an instantaneous internal determination.Citation11,Citation12 These models frame patient action (and inaction) around a health problem in three identifiable phases and have been successfully applied to other nuanced and stigmatised health issues, such as intimate partner violence and mental health.Citation13–15 The first phase is the problem definition and appraisal – that is, how an individual defines or labels a problem and evaluates its severity. Is the pregnancy unacceptable? Will there be negative consequences if a woman continues her pregnancy? If so, how severe does she perceive those consequences to be? Those determinations lead to the second phase: the decision to seek help (e.g. whether or not to take steps to seek abortion services). Evidence from other stigmatised health needs suggests that the decision to seek help is heavily influenced by whether obtaining help seems feasible.Citation13,Citation15 Lastly, according to theory, the third phase is the selection of a help provider, meaning the identification of informal or formal sources of support that can help actualise the decision.

Pathways to abortion services

Existing literature offers information about women’s pathways to abortion services, without specific attention to those women living in rural communities. The evidence is captured from the vantage point of those who arrive at a point of service. In one study, 58% of women reported that they would have liked to have had the abortion earlier.Citation16 The most common reasons for delay were that it took a long time to make arrangements (59%), to decide whether to have the abortion (39%) and to discover the pregnancy in the first place (36%).Citation16 Inaccurate referrals, difficulty finding an appropriate provider, and the time needed to collect the money are also noted as reasons for the delay.Citation16 The cost of abortion is an important factor in abortion delay, particularly for low-income women.Citation17,Citation18 For an estimated 4000 women each year in the U.S., the combination of delays and gestational limits ultimately results in not obtaining a wanted abortion.Citation19 How the barriers observed in these samples of women compare to those faced by women in rural communities has not yet been explored in the United States. Initial qualitative research capturing narratives from fifteen women who received services in New Zealand identified several barriers on the pathway to care, such as identifying a provider, stigma, shame and secrecy, and logistics in accessing care, related to travel, money and support.Citation20 Understanding the barriers and facilitators on the pathway of rural women to obtain an abortion in the United States holds the potential to highlight disparities and to identify modifiable factors.

Methods

Research questions

The primary research question for this study was: what barriers do women of reproductive age who live in rural counties in Central Appalachia face when seeking reproductive health care and what facilitates access to care? Research questions for this analysis are: (1) what factors do women living in rural communities use to define the acceptability of continuing or terminating a pregnancy? (2) how, if at all, does perceived feasibility of obtaining abortion services influence the decision to seek care? and (3) for women who decide to seek care, what, if any, resources and barriers do women encounter when actively seeking abortion services?

Sampling

This study included English-speaking women aged 16–45 years, residing in United States Census-defined rural counties in Central Appalachia. Within these inclusion criteria, we used a stratified purposeful sampling approach, seeking the participation of three groups of women: (1) women presently accessing specialised reproductive health services, recruited at specialised facilities offering abortion care within 300 miles of the centre of this region, (2) women presently accessing general reproductive health services, recruited at federally funded primary health care centres located in rural counties within this region, and (3) women not accessing any reproductive health services at time of recruitment, invited to participate at centres of commerce located in rural counties within this region. Centres of commerce are clusters of stores (“strip malls”) joined by common entrances and parking areas. Recruitment was further stratified within these three groups by age (16–25 years and 26–45 years, delineated by eligibility for inclusion on parents’ health insurance). Formal consent was obtained from all participants. Additionally, we obtained parental consent for participants under 18 years of age.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from three specialised reproductive healthcare facilities offering abortion care, two federally funded primary health care centres, and two centres of commerce in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia. For participants recruited at centres of commerce, study team members approached potential participants in public spaces using a recruitment script and screened for eligibility criteria. Those participants who agreed to participate in the study were interviewed at a later date/time in a setting where privacy could be assured. For participants recruited at health facilities (specialised and primary care), potential participants were approached by clinical staff who described the study and asked if they had any interest in study participation. Those who expressed interest were then screened for inclusion criteria. At specialised reproductive health facilities, we recruited women seeking abortion as potential participants. At primary care facilities, women seeking a variety of clinical services at the facilities’ reproductive health clinics were included as potential participants.

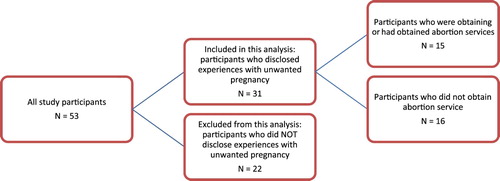

Study recruitment occurred from December 2013 to September 2014 and was concluded at the point of thematic saturation. Of the 53 participants who completed interviews as part of this study, 31 were included in this analysis. This analysis thus examines a subset of interviews within the overall study: women who described having unwanted pregnancies at the time of pregnancy diagnosis, including women who intended to have, or who had, an abortion, and women who explicitly considered terminating a pregnancy ().

As part of the semi-structured interview tool, each participant was asked to “share her story” of each pregnancy, starting “from the moment [she] first suspected [she] was pregnant.” Respondents included in this sub-analysis were those who discussed feeling, around the discovery of at least one pregnancy, that they did not want to continue that pregnancy. Respondents were not directly asked about pregnancy wantedness. Codes for inclusion were (1) feeling unable to parent a child resulting from continuing the pregnancy, and (2) expressing that continuing the pregnancy would be highly disruptive. This enabled us to include participants who may have considered terminating their pregnancy, but ultimately moved forward to continue the pregnancy, as well as those who obtained abortion services.

Data collection

Semi-structured, in-person interviews ranged from 20 to 45 minutes. Study design and tools were reviewed for suitability for the study population by a community advisory board from Central Appalachia, including a researcher, two health care providers, and a community advocate, and recruitment specifics were adjusted based on their feedback (no adjustments to the study tools were recommended). Participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire after the written consent process and prior to the interview. The questionnaire consisted of five items about age, insurance status, relationship status, caregiving responsibilities, and education. Interviews explored participants’ experiences accessing any kind of healthcare, their experiences accessing reproductive health care, their sources of information on reproductive healthcare, and their experiences around seeking and receiving pregnancy-related care. A single interviewer, trained in qualitative methods, conducted all interviews. After the completion of the interview, participants were given a $50 store gift card in appreciation for their time. An additional $15 gift card to a local gas station chain for transportation costs was given to all participants who had travelled to a separate location from where they were recruited. The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Institutional Review Board approved this study. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Identifying information was removed to protect individual anonymity.

Analysis

For the analysis, we layered two methods. First, we used an inductive approach to data analysis, a process derived from grounded theoryCitation21 conducted iteratively to hone the analysis. Data analysis took shape over three phases: (1) “open coding”, in which transcripts were reviewed to conceptualise patterns and themes in the data, (2) the application of categories and codes related to the research question, and (3) axial coding, in which the relationships between concepts were examined. Initial themes and relationships between themes developed using this inductive approach had the potential to connect to existing frameworks, specifically those addressing pregnancy acceptability and help-seeking behaviours.Citation9,Citation11 Second, to refine the axial coding, we completed a thematic content analysis using existing frameworks, focused on the sub-domains of pregnancy acceptability (as it relates to findings on pregnancy decision-making) and help-seeking behaviours (as relevant to the dynamics between decision-making and navigation to care). Thematic content analysis was used to sharpen the axial coding which surfaced via the inductive approach, our primary analytic approach. The corresponding author conducted all coding and analysis, drawing on an immersion and crystallisation approach; additional authors reviewed codes for clear conceptualisation, assisted with the iterative development of the research questions, and co-developed the emergent framework that resulted from axial coding. Additionally, findings from the interview transcripts were triangulated with field notes, taken after each interview. We used NVivo qualitative analysis software for data management and as a tool to support the development of codes.

Results

Participant demographics

Participants included in this analysis were similar in characteristics to all study participants (). The largest group of participants were in their twenties (median 27, range 17–44 years) and almost all were white, with a small number of black participants, consistent with the demographics of the region overall. 45% of participants were uninsured at the time of the interview, 32% received insurance provided by the state and 23% had private insurance. In the context of family life, 77% had a partner as of the time of the interview and 60% were the primary caregiver for one or more children. Participants had varied educational backgrounds: 13% completed some high school, 35% completed a high school degree, 39% completed some college coursework (associate or bachelor program), and 13% completed a college degree (associate or bachelor degree). Of the participants included in this analysis, 14 (45%) were recruited at specialised facilities, 7 (23%) were recruited at primary care facilities, and 10 (32%) were recruited at centres of commerce.

Table 1. Participant demographics

Framework for abortion decision-making in rural communities

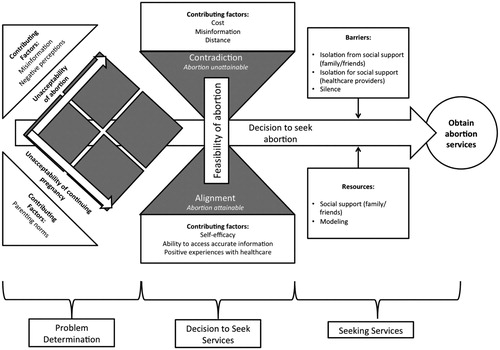

The results suggest that women living in rural communities engage with the potential for obtaining abortion services in three phases: pregnancy and abortion assessment, the decision to seek services, and the pathway to service (). The first phases align closely with what is documented in the “help-seeking” framework: “problem definition and appraisal” and “decision to seek help” phases, while the last captures attempts at service utilisation. Many participants who discover an unwanted pregnancy ultimately do not decide to seek abortion services. In addition to the participants’ assessments of the acceptability of continuing the pregnancy versus abortion, the decision to seek care is heavily influenced by the feasibility of obtaining abortion services. Participants do not decide to seek abortion services if obtaining those services appears difficult because of contributing factors such as cost, misinformation, distance, a lack of self-efficacy, and previous negative experience with healthcare. Once the decision is made to seek care, the pathway to care is made more or less challenging by the presence of various helping resources or barriers.

Acceptability of abortion and of continuing pregnancy

In participant narratives, decisional conflict around the outcome of an unintended pregnancy is not restricted to the acceptability of continuing the pregnancy. These narratives reveal that participants managed conflict around the acceptability of continuing the pregnancy, and the acceptability of obtaining an abortion, simultaneously (). Many women described one potential outcome as unacceptable, but not the other. A small subset of participants articulated both outcomes as acceptable, almost neutral. A portion of participants determined that continuing the pregnancy and obtaining an abortion were both highly unacceptable.

Table 2. Matrix reflecting the unacceptability of abortion and of continuing pregnancy among participants

While conflict around an important decision is common and to be expected, three factors (misinformation, negative perceptions of abortion, and parenting norms related to unwanted pregnancy), internalised by some women, heighten the conflict. When determining the acceptability of continuing the pregnancy, participants discussed strong norms on continuing unwanted pregnancies. One participant in her mid-twenties from Kentucky, recruited at a centre of commerce, shared her thoughts about her first pregnancy at age 16:

“I was off of that Depo shot for a year, and I got pregnant on accident. And I didn’t want to be. My daddy about died, said, ‘Oh, you’ve ruined your life.’ But my family, the way we were raised, you don’t have abortions [whispering]. Automatically, that wasn’t a choice. It’s either I was gonna raise it or my daddy would raise it. They’re just like that, I guess they’re old-fashioned. But after I got used to the fact, I guess I loved the fact of it.”

Two factors influenced the determination of abortion acceptability. First, negative perceptions of abortion, like the perception that abortion is morally wrong or fraught. One participant in her mid-thirties from Kentucky, recruited at an abortion facility, described her thinking:

“Do I agree with abortions? Not really. I think there’s a time for it. A lot of women, I would say, probably use it as a form of birth control. I hate to say that, but I’m sure it’s probably true. I don’t see it like that. I do think it’s wrong, you know?”

“[I had to do] a lot of internet Googling, and things like that … I was first making sure that it was legal to do it, because I know in some states … I have no idea anything about it. And a lot of different sides tell you different things … And I was really worried because every site told me something different. What to expect, and some of it saying it’s really dangerous, and some say it’s safer than giving birth.”

Feasibility of obtaining abortion services, the decision to seek care, and the experience of seeking care

Assessment of the feasibility of obtaining abortion services is closely connected with the decision to seek care. Three contributing factors contribute to participants describing obtaining abortion as feasible – self-efficacy, positive experiences with healthcare in the past, and the ability to access accurate information. Self-efficacy is the strength of one’s belief in one’s own ability to complete tasks and reach goals. A participant in her early thirties from Kentucky, recruited at an abortion facility, illustrated this confidence. Her confidence enabled her to navigate through a crisis pregnancy centre to confirm her pregnancy first, then to the abortion facility, without concern that she would ultimately obtain the services she needed:

“So all these different numbers started popping up. And one of the very first numbers I called was the place here in Lexington. They don’t do abortion services, but I was on the phone like, ‘Hey, can you tell me all about it? I’m clueless. I have no idea.’ And she’s like, ‘Honey, we don’t do them and we don’t offer them. We don’t refer them. All we do is give free pregnancy tests and ultrasounds.’ I said, ‘Fabulous, because I took a pregnancy test. I know that I am. But I would love to know how far along I am.’ And that’s how I found that place was just Googling ‘abortion services,’ and that popped up. They don’t condone the abortions, you know? They’re there for you, whatever decision you make, whether you wanna have it, give it up for adoption, abortion—whatever. I talked to ‘em about my choice. They counseled me a little bit on it to make sure that I knew what I was talking about, you know? Because I don’t think a lot of girls know what they’re getting themselves into when they’re doing something like this.”

“I’ve always kind of had a primary care doctor, and I’ve tried to always stay on birth control. I don’t have any kids. And I just moved here to Kentucky, and I hadn’t gotten a regular doctor yet. And, you know, my prescription ran out. And within that month’s time, voilà … I found this place [the abortion facility] online and when I called, they were very nice.”

“On figuring out where to go, it’s actually been pretty easy. Again, went to my handy-dandy internet, and, of course, I’d always heard about Planned Parenthood, but you get ‘abortion abortion abortion’ stuff. As far as health care, they’ve actually been very nice today, and I was like, ‘This is how they treat you when you come here; maybe I should maybe start coming here on a regular basis.’”

“The cost was another issue, because at that time I didn’t really have a job or any sort of way to get money. My sister ended up helping me out. I had transportation, so it wasn’t an issue to get there. I would say just the cost was the biggest issue.”

“Because I just lacked a week from being too far to have [my abortion] done here. And where we live, it was over two hours to get here. Where I live so far out from hospitals and stuff, I would think it’s so far away to even get an ultrasound, and what if my water broke or something if I kept [the pregnancy]? I’d be so far out, and the roads are so bad. I live on a dirt road. I just thought, you know — my mom done it with seven kids … Getting here today, it was really hard. But I made it, I guess.”

The dynamic relationship between these phases of abortion decision-making played out in a liminal moment, more often hours than weeks. For example, a participant in her early twenties from Kentucky, recruited at a centre of commerce, shared that she suspected she might be unexpectedly and unwantedly pregnant at the time of her interview:

“I need to be on birth control, bad. I think, I don’t know, but I’m praying … I’ve been so nauseous. I hope I’m not, but if I am, I don’t want to, but I just can’t do it. I already have two too many.”

Barriers and facilitators related to seeking abortion services

For women who actively seek abortion care, the pathway to obtaining abortion services is made more, or less challenging, depending on the presence of resources and barriers (). Barriers include the absence of emotional, appraisal, informational, or instrumental assistance received from family/friends; the absence of emotional, appraisal, informational, or instrumental assistance received from healthcare providers; and the absence of abortion narratives in the immediate community. Facilitators include the presence of social support from family/friends and modelling (observing of other’s abortion experience).

Table 3. Resources and barriers in pathway to abortion services

Discussion

This study directly explores the relationship between residing in a rural county and access to abortion services in the United States. These results offer insight into the experiences of this population. Instead of recruiting exclusively at the point of abortion service provision, this study recruited participants in rural communities in multiple locations and included a diversity of experiences related to pregnancy decision-making and barriers and facilitators to obtaining services.

Access to abortion services is uniquely challenging for rural communities. Initial qualitative research has established a broader framework to analyse rural women’s experiences accessing abortion services.Citation22 In that framework, the nature of the health need – both the level of specialisation required to provide the needed care (e.g. dilating the cervix to place an intrauterine contraceptive device) and the level of stigmatisation attached to it (e.g. shame around testing for sexually transmitted infections) – has a cascading influence on the experiences of participants accessing reproductive health services. These two components – stigmatisation and specialisation – powerfully influence women’s navigation to needed services by shaping women’s ability to access care and possibly the quality of the care received. Compared to other reproductive health services, abortion services are largely limited to specialised clinicians and facilitiesCitation23 and are more stigmatisedCitation24 than other reproductive health services. These qualities mean that abortion services are not offered to a woman living in a rural county's immediate community (e.g. town or county) and social support around seeking services tends to be absent. Both these factors make the navigation to care more challenging, and the service more difficult to access, which suggests that the experiences of those accessing abortion may be uniquely challenging, compared to those accessing other reproductive health services.

Given the navigation challenges associated with accessing abortion services, the “help-seeking” framework may be especially relevant to women living in rural communities as a means to add depth around the decision to seek abortion services. Applying these theoretical concepts to abortion decision-making among rural women, it is clear that there may be an interplay between the “problem definition and appraisal” and “decision to seek help” phases. Cognitive dissonance theory offers insight into the dynamics related to the decisional conflict. Applied plainly to women’s decision-making around pregnancy, the belief that continuing pregnancy is unacceptable (the problem definition), could conflict with the belief that abortion services are unattainable, which strongly influences the decision to seek help. Cognitive dissonance theory hypothesises that an individual seeks to resolve this internal conflict through a variety of means, including changing one of the conflicting ideas (e.g. “my pregnancy is acceptable”).

Notably, the results of this study develop a framework which describes how women living in rural communities engage with the potential of obtaining abortion services. This framework has three phases: (1) the simultaneous assessment of the acceptability of continuing the pregnancy and acceptability of terminating the pregnancy, (2) the decision to seek services, and (3) the pathway to service. This framework expands the binary constructs around abortion access – for example, decide to seek an abortion/decide not to seek an abortion, obtain abortion services/do not obtain abortion services – and critically captures the dynamic, often internal, calculations women make around unwanted pregnancy.

The liminal space of a newly identified unintended pregnancy is a continuation of the emotional fluidity documented around pregnancy intention. Based on these results, the determination of the acceptability of a pregnancy is assessed in parallel to abortion acceptability. Women are simultaneously conducting assessments of the acceptability of two potential outcomes: abortion and continuing the pregnancy (adoption was notably absent from the respondents’ narratives). The intersection of these two assessments can result in high conflict (when both outcomes are unacceptable), or deep ambivalence (when she feels neutral about both outcomes). Community norms and beliefs are deeply tied to women’s assessment of abortion as an outcome. For example, the perceived deviance of having an abortion, and misinformation about the medical safety of abortion, promotes the unacceptability of terminating a pregnancy. Strong community norms of parenting children resulting from unwanted pregnancies promote the acceptability of continuing a pregnancy.

Decision-making around unwanted pregnancy is also heavily influenced by the perceived feasibility of obtaining abortion services. Factors relevant to the feasibility of obtaining care are well-known in the literature, including finding correct information, managing the logistics of seeking care, and gathering the financial resources needed to pay for care. The influence of rurality is in the confluence of several barriers that are consistent throughout these data: the absence of abortion narratives in the immediate community and the normalisation of continuing an unwanted pregnancy, combined with the distance between a woman’s community and care. This trio of factors, tied to the community of residence, can make women perceive that even attempting to seek abortion services is an enormous task. These results exclusively represent women's perceptions, without additional validation; how “objective” factors that potentially limit a woman’s ability to obtain abortion services compare to a woman’s perception of the feasibility of terminating a pregnancy is not captured in this study, but would hold great value to contextualising these findings. That said, many women, fortified by facilitators like self-efficacy or positive experiences receiving needed healthcare, both undertake and succeed in that task. A small group is propelled beyond both the perceived enormity of the task and their assessment of abortion as unacceptable by what they perceive as the desperate circumstances that would result from continuing their pregnancy. This group is especially vulnerable to negative experiences in their navigation process, such as fear, shame, and distress.

Cognitive dissonance theory points to the impulse to resolve these points of conflict. For some participants, especially those who did not actively seek abortion services despite the distress they articulated around continuing the pregnancy, this resolution reframes the ultimate parenting of the child from the unwanted pregnancy as a positive outcome. For these women, what is modifiable is their own acceptance of what had previously been an unacceptable outcome: continuing the pregnancy. The resolution of this internal conflict may take place internally and very quickly. However, it also points to potential unmet need.

These results resonate with the literature on “help-seeking” related to other stigmatised health issues, such as mental health, substance abuse, sexually transmitted infections, and intimate partner violence. These findings also resonate with aspects of the rural health discourse. Ricketts and Goldsmith highlight the interaction between the patient and the healthcare system as dynamic and iterative, with patient expectations shaped by their experiences around requiring, seeking, and receiving care.Citation25 Non-use of services is the product of negative experiences from an attempt to access services in the past.Citation25 Given that the health infrastructure in some rural communities in Central Appalachia is more limited than in urban communities,Citation26 women in rural communities may have lived experiences that suggest their health needs will not be met, which may influence their abortion decision-making. Finally, these results raise important questions about the modifiable factors in this dynamic. Women living in rural communities carry the burden of contextual conflict related to abortion services – notably misinformation about safety and cost. Would the conflict women face resolve differently if these barriers were removed?

This study offers the unique strength of examining abortion decision-making via recruitment of both women who arrive at the point of abortion service delivery and those who do not. Further research with similarly inclusive samples is needed to explore how, if at all, these findings are applicable to other groups of women, or to all women. While there is excellent research on the reasons why women seek abortion services,Citation27,Citation28 there is a dearth of research on why they do not. The implicit assumption that women who continue pregnancies did not want to terminate them is not sufficient. While reflections on this liminal space result from an analysis of the experiences of women living in rural communities, the dynamics described may have implications for other populations.

Given the specific regional focus and the sample size, these findings are not generalisable to all rural women. By applying qualitative methods, the analysis seeks to establish breadth and depth in exploring the experiences of a specific group of women. Also, abortion is a sensitive topic, which can raise participant anxiety or concern related to confidentiality. While we made efforts to minimise the effect of anxiety or concern in data collection, it is possible that participants did not fully disclose their experiences related to abortion and pregnancy. This analysis also has clear strengths. As aforementioned, the recruitment approach enabled the inclusion of narratives from women with varied experiences around unwanted pregnancy and accessing abortion services, expanding the analysis beyond the narratives of women who obtained care. Simultaneously, the research questions elicited experiences related to abortion within the broad frame of reproductive health, while enabling a comparison between these experiences and experiences related to other services. Finally, the data collection reached the point of saturation, which underscores that an appropriate sample size was achieved to develop valid themes. Despite the study’s limitations and in light of these strengths, the results provide initial, and previously absent, insights into rural women’s experiences accessing abortion in Central Appalachia and the complex dynamics around pregnancy decision-making in the context of multiple barriers to abortion access.

Conclusion

Women living in rural communities in Central Appalachia engage with the potential of obtaining abortion services within three phases: pregnancy and abortion assessment, the decision to seek services, and the pathway to service. The liminal space around deciding on a plan for managing an unwanted pregnancy is heavily influenced by the perceived feasibility of obtaining abortion services (similar to that related to other stigmatised health needs). What is modifiable is their own acceptance of what had previously been an unacceptable outcome: continuing the pregnancy. This understandable response to internal conflict, at the population level, may conceal potential unmet need for abortion services; this unmet need has negative implications for women's health and well-being, and may be avoidable. Efforts to make abortion feasible for women living in rural communities holds the potential to reduce the conflict some women experience in their decision-making around pregnancy and abortion. This could take the form of removing concrete barriers to abortion services, such as misinformation and cost, or perceived barriers, such as negative perceptions of abortion, or the absence of narratives from other women living in rural communities, who obtained abortion services. Addressing modifiable factors at the population level would allow women, especially those for whom continuing their pregnancy is highly unacceptable, to avoid reliance on the lone modifiable factor that is fully in their control – their acceptance of previously unacceptable outcomes in their reproductive lives.

New insights offered by the present study allow for a careful consideration of rural women's experiences seeking the care they need, and are valuable for policy makers and clinicians. These findings offer preliminary evidence to inform rural-focused interventions. Additionally, this analysis adds critical nuance to the dynamic relationship between pregnancy acceptability, abortion acceptability, and the sociocultural context of pregnancy and abortion acceptability, which has the potential to concretely shape pregnancy decision-making and help-seeking behaviour related to unwanted pregnancy. These findings may be relevant beyond the study population, and provide insights into how objective and perceived barriers to obtaining abortion services are internalised by women and potentially influence pregnancy decision-making.

ORCID

Jenny O'Donnell http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8887-8744

Theresa Betancourt http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3683-4440

References

- Women’s Health USA 2011. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, 2011.

- Jones RK, Darroch JE, Henshaw SK. Patterns in the socioeconomic characteristics of women obtaining abortions in 2000–-2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34(5):226–235. Epub 2002/10/24. PubMed PMID: 12392215. doi: 10.2307/3097821

- ACOG. Committee opinion No. 586: health disparities in rural women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 Pt 1):384–388. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000443278.06393.d6. Epub 2014/01/24. PubMed PMID: 24451676.

- Jones RK, Jerman J. How far did US women travel for abortion services in 2008? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(8):706–713. Epub 2013/07/19 06:00. PubMed PMID: 23863075. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4283

- O’Donnell J, Goldberg AB, Betancourt TS, et al. Access to abortion in Central Appalachian states: examining county of residence and county-level attributes. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. Forthcoming 2018. doi:10.1363/psrh.12079

- Commission AR. The Appalachian region 2017. Available from: https://www.arc.gov/appalachian_region/TheAppalachianRegion.asp.

- Behringer B, Friedell GH. Appalachia: where place matters in health. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(4):A113.

- Aiken ARA, Dillaway C, Mevs-Korff N. A blessing I can’t afford: factors underlying the paradox of happiness about unintended pregnancy. Soc Sci Med. 2015;132:149–155. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.038. PubMed PMID: 25813729; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4400251.

- Aiken AR, Borrero S, Callegari LS, et al. Rethinking the pregnancy planning paradigm: unintended conceptions or unrepresentative concepts? Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;48(3):147–151. doi:10.1363/48e10316. Epub 2016/08/12. PubMed PMID: 27513444; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5028285.

- Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1957.

- Cornally N, McCarthy G. Help-seeking behaviour: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17(3):280–288. doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2011.01936.x. Epub 2011/05/25. PubMed PMID: 21605269.

- Pescosolido BA. Beyond rational choice: The social dynamics of How people seek help. AJS. 1992;97(4):1096–1138.

- Liang B, Goodman L, Tummala-Narra P, et al. A theoretical framework for understanding help-seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;36(1–2):71–84. doi:10.1007/s10464-005-6233-6. Epub 2005/09/01. PubMed PMID: 16134045.

- Greenlay R, Mullen A. Help-seeking and the use of mental health services. Res Commun Ment Health. 1990;6:325–350.

- Fox JC, Blank M, Rovnyak VG, et al. Barriers to help seeking for mental disorders in a rural impoverished population. Commun Ment Health J. 2001;37(5):421–436. Epub 2001/06/23. PubMed PMID: 11419519. doi: 10.1023/A:1017580013197

- Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, et al. Timing of steps and reasons for delays in obtaining abortions in the United States. Contraception. 2006;74(4):334–344. Epub 2006/09/20 09:00. PubMed PMID: 16982236. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.04.010

- Roberts SC, Gould H, Kimport K, et al. Out-of-pocket costs and insurance coverage for abortion in the United States. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(2):e211–e218. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.01.003. Epub 2014/03/19. PubMed PMID: 24630423.

- Margo J, McCloskey L, Gupte G, et al. Women’s pathways to abortion care in south carolina: A qualitative study of obstacles and supports. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;48(4):199–207. doi:10.1363/psrh.12006. Epub 2016/11/29. PubMed PMID: 27893185.

- Upadhyay UD, Weitz TA, Jones RK, et al. Denial of abortion because of provider gestational Age limits in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;15. Epub 2013/08/21 06:00. PubMed PMID: 23948000.

- Doran FM, Hornibrook J. Barriers around access to abortion experienced by rural women in New South Wales, Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2016;16(1):3538. Epub 2016/03/19. PubMed PMID: 26987999.

- Strauss A. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987.

- O’Donnell J, Goldberg A, Lieberman E, et al. Specialized, stigmatized, and forgotten: cascading effects on access to women’s reproductive healthcare in Appalachia. 2016.

- Jones RK, Kooistra K. Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43(1):41–50. Epub 2011/03/11 06:00. PubMed PMID: 21388504. doi: 10.1363/4304111

- Kumar A, Hessini L, Mitchell EM. Conceptualising abortion stigma. Cult Health Sex. 2009;11(6):625–639. Epub 2009/05/14. doi:10.1080/13691050902842741. PubMed PMID: 19437175.

- Ricketts TC, Goldsmith LJ. Access in health services research: the battle of the frameworks. Nurs Outlook. 2005;53(6):274–280. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2005.06.007. Epub 2005/12/20. PubMed PMID: 16360698.

- Lane NM, Lutz AY, Baker K. Health care costs and access disparities in Appalachia. Washington (DC): Appalachian Regional Commission; 2012.

- Biggs MA, Gould H, Foster DG. Understanding why women seek abortions in the US. BMC Womens Health. 2013;13:41. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-13-29. Epub 2013/07/09. PubMed PMID: 23829590; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3729671.

- Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, et al. Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(3):110–118. doi:10.1363/psrh.37.110.05. Epub 2005/09/10. PubMed PMID: 16150658. doi: 10.1363/3711005