Abstract

The caste system is a complex social stratification system which has been abolished, but remains deeply ingrained in India. Scheduled Caste (SC) women are one of the historically deprived groups, as reflected in poor maternal health outcomes and low utilisation of maternal healthcare services. Key government schemes introduced in 2005 mean healthcare-associated costs should now be far less of a deterrent. This paper examines the factors contributing to this low use of maternal health services by investigating the perceptions, health-seeking behaviours and access of SC women to maternal healthcare services in Bihar, India. Eighteen in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with SC women in Bihar. Data were analysed using Framework Analysis and presented using the AAAQ Toolbox. Main facilitating factors included the introduction of accredited social health activists (ASHAs), free maternal health services, the Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK), and changes in the cultural acceptability of institutional delivery. Main barriers included inadequate ASHA coverage, poor information access, transport costs and unauthorised charges to SC women from healthcare staff. SC women in Bihar may be inequitably served by maternal health services, and in some cases may face specific discrimination. Recommendations to improve SC service utilisation include research into the improvement of postnatal care, reducing unauthorised payments to healthcare staff and improvements to the ASHA programme.

Résumé

Le régime des castes est un système complexe de stratification sociale qui a été aboli, mais demeure profondément ancré en Inde. Les femmes appartenant à une caste répertoriée (Scheduled Caste) forment l’un des groupes défavorisés de longue date, ainsi que le montrent les mauvais résultats de santé maternelle et la faible utilisation de services de santé maternelle. Des projets gouvernementaux majeurs introduits en 2005 auraient dû rendre les frais associés aux soins de santé moins dissuasifs. Cet article examine les facteurs contribuant à ce faible recours aux services de santé maternelle en enquêtant sur les conceptions, les comportements favorisant la santé et l’accès des femmes des castes répertoriées aux services de santé au Bihar, Inde. Dix-huit entretiens approfondis semi-structurés ont été réalisés avec des femmes de castes répertoriées au Bihar. Les données ont été analysées à l’aide du logiciel Framework Analysis et présentées avec la boîte à outils AAAQ (disponibilité, accessibilité, acceptabilité et qualité). Les principaux facteurs favorables comprenaient l’introduction d’agents sanitaires et sociaux certifiés (ASHA), la gratuité des services de santé maternelle, le programme Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK) et des changements dans l’acceptabilité culturelle des accouchements pratiqués dans un centre de santé. Les obstacles les plus importants incluaient la couverture insuffisante des ASHA, l’accès médiocre aux informations, les dépenses de transport et les frais que les agents de santé perçoivent sans autorisation aux femmes des castes répertoriées. Il est possible que les femmes des castes répertoriées au Bihar soient desservies de manière inéquitable par les services de santé maternelle et, dans certains cas, qu’elles soient en butte à une discrimination spécifique. Parmi les recommandations pour accroître l’utilisation des services par les castes répertoriées figurent la recherche sur l’amélioration des soins postnatals, la réduction des paiements non autorisés au personnel de santé et des progrès dans le programme des ASHA.

Resumen

El sistema de castas es un sistema complejo de estratificación social que ha sido abolido, pero continúa profundamente arraigado en India. Las mujeres de Castas Desfavorecidas (SC, por sus siglas en inglés) son uno de los grupos históricamente desfavorecidos, como se refleja en malos resultados de salud materna y bajo uso de servicios de salud materna. Los esquemas gubernamentales clave presentados en 2005 significan que los gastos asociados con los servicios de salud deberían ser mucho menos disuasivos ahora. Este artículo examina los factores que contribuyen al bajo uso de los servicios de salud materna, al investigar las percepciones, los comportamientos de búsqueda de atención sanitaria y el acceso de las mujeres de SC a los servicios de salud materna en Bihar, India. Se realizaron 18 entrevistas semiestructuradas a profundidad con mujeres de SC en Bihar. Los datos fueron analizados con el Análisis de Marco y presentados con el Juego de Herramientas AAAQ. Los principales factores facilitadores fueron: la introducción de activistas acreditados en salud social (ASHA), servicios gratuitos de salud materna, el Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK) y cambios en la aceptabilidad cultural de la entrega institucional. Las principales barreras fueron: cobertura inadecuada por ASHA, limitado acceso a información, gastos de transporte y cargos no autorizados a las mujeres de SC por parte del personal sanitario. Las mujeres de SC en Bihar posiblemente sean atendidas de manera desigual por los servicios de salud materna, y en algunos casos podrían enfrentar discriminación específica. Entre las recomendaciones para mejorar el uso de servicios por las mujeres de SC se encuentran: investigar el mejoramiento de la atención posnatal, reducir pagos no autorizados al personal de salud y mejorar el programa de ASHA.

Introduction

Once a country with one of the highest maternal mortality ratios (MMR) in the world, India has made great strides towards improving maternal healthcare. The MMR has been lowered by 77% between 1990 and 2016, to current levels of 130 per 100,000.Citation1,Citation2

This decline can be partly attributed to the introduction of several key government interventions under the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) which began in 2005 ().Citation3 The NRHM has been hailed globally as a successful programme, with institutional delivery rates increasing from 39% to 79% between 2005 and 2016.Citation4 However, this progress has not been homogenous; MMR varies dramatically country-wide, indicating the inequities that persist across dimensions such as geography, wealth and rural-urban status.Citation5 These inequities, combined with India's vast population and high fertility rate, mean that India still accounts for 15% of global maternal deaths, more than any other country.Citation6,Citation7

Table 1. Key schemes implemented under the National Rural Health MissionCitation3

Poor maternal health is still too prevalent in many communities and this is particularly apparent within India's low caste groups.Citation8,Citation9 This paper seeks to better understand the inequalities in maternal health of one of India's most deprived populations; the Scheduled Castes (SCs).

The caste system is a complex social stratification system; at the upper end are the General Castes, the Other Backward Castes, and at the bottom are the SCs and Scheduled Tribes which are historically the more deprived groups.Citation10 The caste system was abolished in 1949, and it has been a challenge to liberate the country of a system deeply ingrained within its culture. SCs and Scheduled Tribes still face many forms of discrimination, deprivation and health inequalities.Citation8,Citation9 SCs constitute 17% of India's population and were previously named “Untouchables” due to traditional Hindu beliefs that they were polluting to touch.Citation10,Citation11 It is estimated that 30% of people belonging to SCs live below the poverty line of ∼30Rs (∼US$ 0.45) a day, with the majority living in slums or segregated villages.Citation10,Citation12 SC women often face triple discrimination due to their caste, socio-economic status and gender, and these problems have previously been reflected in poor maternal health outcomes.Citation8,Citation9 There is no recent available data comparing national maternal outcomes between castes, but smaller-scale studies show a continued strong relationship between caste and MMR/reproductive morbidity.Citation9,Citation13,Citation14

Given a variety of factors such as lower general living standards and general health indicators, it is unsurprising that indicators of maternal health are poorer in SC women.Citation8,Citation9 It should follow that they have an increased need for health care, yet they continue to show a lower utilisation of health services such as antenatal care (ANC) over a period of a decade, as shown by National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data ().Citation15,Citation16

Table 2. National Maternal Health Service Utilisation, India, disaggregated by casteCitation15,Citation16

Before the introduction of the NRHM, differences in service utilisation may have been expected due to poverty in SC women. Many would face catastrophic expenditure to access maternal health services.Citation17 However, with the introduction of the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY)/JSSK schemes, transport and healthcare are now free, with a cash incentive for institutional delivery, making costs less of a deterrent.

This paper seeks to better understand why the use of maternal health services by SC women remains lower, by investigating the perspectives of SC women regarding facilitating factors and barriers to their maternal healthcare.

Methodology

Study location and sampling

Eighteen interviews were conducted in six locations within Purnia district, Bihar in May 2017. There are currently 17 million SCs living in Bihar, with 12% of Purnia's population made up of SCs.Citation18,Citation19 Three interviews each were conducted at a Primary Health Centre (PHC) and an Anganwadi Centre (small village shelters providing basic health care), and six interviews each at rural village homes and urban slum homes. Bihar has a MMR of 274 per 100,000 live births (2013) and institutional delivery rate of 64% (2015).Citation17,Citation19 The district was selected because of poor indicators for maternal health. The most recently reported MMR in Purnia is also one of the worst in the country, at 349 per 100,000 live births (2013), although it is possible that improvements have occurred since it became one of 184 priority districts to receive increased government funding and attention in 2015.Citation20,Citation21

The six locations were purposively chosen, with the aim of recruiting from a broad range of SC women, including women from both rural and urban locations. Participants were recruited opportunistically, through block managers (whose role is to facilitate and monitor the health system within a sub district area) or ASHAs, providing they were available and fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: female, age >21 years, belonging to a SC and had given birth 1–4 years previously. These criteria were identified using ASHA registers and checked prior to each interview. India has high levels of child marriage, leading to high numbers of adolescent pregnancies.Citation22 These young mothers are more likely to suffer from mental health and other problems during pregnancy so these women were excluded to minimise potential harm from the discussion of sensitive topics.Citation23 Mothers giving birth in the previous year were also excluded in case participation caused distress from the discussion of traumatic deliveries.

Data collection

Eighteen in-depth interviews were conducted, after which data saturation was reached. The interview technique was semi-structured, allowing adaptation of questions to emerging themes. Non-leading, open questions were derived using data from a literature review and existing questionnaires on maternal healthcare utilisation.Citation16 Interviews were 45–60 minutes, recorded using the application “Dictaphone” and conducted by the lead researcher and a local female translator (translating English to Hindi). Before the interviews, the translator was familiarised with the study and a pilot interview was carried out at a SC woman's home, which helped to determine the seating position of the translator and interviewer, and to finalise the interview questions. Using the recordings, interviews were then transcribed into English. As some data could have been lost during translation of the interviews, a second translator was used to listen to the recordings to ensure consistency with interview transcripts.

All data was stored in either a secure room or a locked flash drive, with participant anonymity ensured through confidentiality training of all parties involved and removal of identifiable information from transcripts. Recordings and transcripts were stored separately from consent forms. Ethical approval was obtained from both the Leeds Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (FMHREC-17–2.3) and other approvals through a signed memorandum of understanding (MoU) submitted to the Government of Bihar, through the parent organisation CARE India, to ensure the project met both international and local research standards. Interviews were conducted in May 2017.

Data analysis

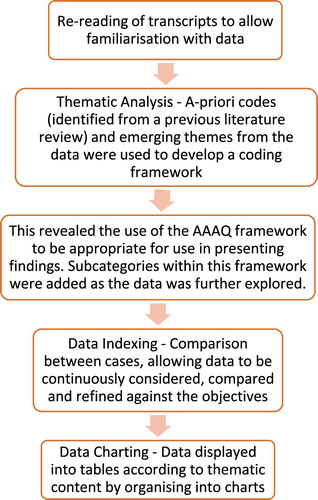

Data were analysed using Framework Analysis ().Citation24

Figure 1. Process of framework analysisCitation24

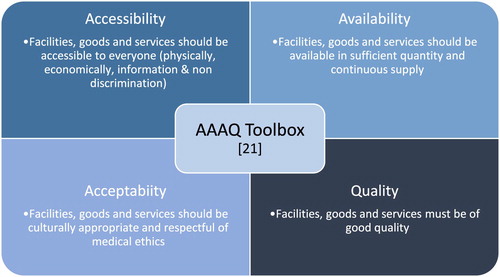

Emerging themes suggested the AAAQ framework () to be appropriate; a framework adopted by the United Nations, containing four elements of the “Right to Health”.Citation25 This has been used previously as guidance for a rights-based approach to target maternal mortality.Citation26

Figure 2. The AAAQ toolboxCitation25

Following interviews and analysis, the findings were discussed in individual meetings with both a local block manager and an experienced public maternal health worker, to generate appropriate recommendations in the context of current Indian health policy.

Findings

The findings are presented as an initial description of service utilisation, followed by women's perceptions, behaviours and access under the four key themes using the AAAQ framework.Citation25

Service utilisation

All but one of the 18 women interviewed had between one and three ANC check-ups. Of these, ten went to a local Anganwadi Centre on Village Health and Nutrition days and seven to a PHC. One woman received no ANC at all and none received the WHO-recommended 4+ ANC check-ups.Citation27

Of the 18 women interviewed, 12 had most recently delivered their baby in the WHO-recommended method (supervised by a skilled birth attendant within a health institution).Citation27 Of six home deliveries, one was attended by a skilled birth attendant, one by a traditional birth attendant and four were attended only by family or friends.

Twelve of the 18 women received no form of postnatal care (PNC) following birth, i.e. they did not receive PNC in-hospital or at home, counselling, or any advice. Five women received between one and three postnatal home visits from an ASHA (whose role is to provide between six and seven visits following delivery and to monitor for signs of post-partum and newborn complications).Citation28 Only one woman received PNC from a fully trained clinician (ANM), after self-recognising symptoms of complications and travelling to her PHC.

None of the women received the WHO-recommended 24+ hours supervision or the 4+ PNC check-ups from a clinician following birth.Citation27

Availability of facilities, services and staff

A lack of general facilities, services and medication was not specifically identified by participants as a barrier to care. However, four women discussed long waits for services, for example:

“It can be very long to wait for medicines and to see health workers.” (Woman A, location 2)

“Sometimes you must wait several hours and it can be tiring.” (Woman C, location 1)

One woman commented:

“The Government always says they will give us more health facilities … but Scheduled Caste can't get any [care] sometimes and we want more.” (Woman B, location 3)

With regard to healthcare staff, in nine interviews, the ASHAs were identified as a facilitating factor through their role in connecting SC women with maternal health services. Six women also identified the ASHA's role in the provision of information (on the JSY, importance of institutional delivery or where to go for ANC and delivery) as a facilitating factor. Another facilitating feature of the ASHA, discussed by two women, was the ASHA's role in the provision of childcare whilst the women were in hospital:

“a big help … this means I don't have to worry about the children during delivery.” (Woman B, location 2)

However, a shortage of healthcare staff also appeared recurrently as a barrier to receiving healthcare; a desire for more ASHAs was discussed in eight interviews. In rural areas there was a desire for more ASHAs:

“there are not enough ASHAs in Bihar in rural areas, we need much more” … (Woman B, location 5)

“there are not enough regular visits from ASHAs.” (Woman B, location 6)

In the urban slums it was unclear whether or not an ASHA system was yet in place. Urban Social Health Activists (USHA), who are urban ASHAs, were technically recruited in 2015 under the National Urban Health Mission (NUHM, 2013) and were introduced in Purnia in 2016–17.Citation29 The scheme should therefore have just come into effect in Purnia at the time of the data collection, but no SC women interviewed in the urban slums had any maternal health contact with an USHA, although several had some form of contact for their children's healthcare, with one women commenting:

“USHA comes only for child immunisation, but do not care for mothers.” (Woman C, location 3)

However, there appeared to be a strong desire for an USHA scheme and four of six women interviewed from urban slums discussed the lack of USHA as a barrier to their access to healthcare, stating that if an USHA visited they could:

“get better healthcare and much more information on where to go, on transport and how to receive JSY payment.” (Woman A, location 4)

Women were also unsure of the reason for the absence of USHAs in their area, with two women questioning whether discrimination was a factor:

“I don't know if the USHA is not coming because she is not appointed or because she does not want to, but this would make things easier … maybe she is avoiding the area because she thinks we live in a dirty area and are unclean.” (Woman B, location 3)

Accessibility of services

No women discussed distance to health facilities or lack of transport as a barrier to receiving healthcare (although due to the sampling methodology, all participants were located reasonably close to a PHC). However, three women discussed their ASHA living outside of their local area, with one woman identifying the ASHA living far away as a barrier to care:

“I called the ASHA to take me but she said she was too far away to help … I do not want to go without the ASHA as I do not know how it works and it would probably cost more. So I delivered at home.” (Woman B, location 1)

Eleven women who delivered institutionally travelled there by auto-rickshaw, costing them between 100–500Rs (∼US$ 1.5–7), and one travelled in her own vehicle. Several women complained about the cost of transport, with one woman identifying the transport cost of 500Rs (∼US$ 7) as a barrier.

With regard to emergency obstetric care (EmOC), the Bihar public ambulance service provides free home to hospital transfers. No woman had used this service during their recent delivery (although one woman discussed using the service previously, with no complaint). Whilst two women living close to a PHC stated they would prefer to use an auto-rickshaw for ease, most were interested in the idea of a free ambulance but knew little about the service. Several women explained they would not know how to contact an emergency ambulance:

“there is an ambulance … but we do not call because we do not know the number.” (Woman A, location 6)

Four women stated they had needed emergency transport but did not know how to access it:

“I needed emergency care but did not know how to call an ambulance … an ASHA has not said how.” (Woman A, location 5)

This had led to women delivering at home rather than in their preferred institution.

Affordability

Most participants were very poor, and cost appeared the dominating factor in their choices regarding healthcare. Whilst 63–70% of Indian households rely on India's vast private sector as the main source of their healthcare,Citation15 all participants in this study had accessed only public services, likely due to their poverty status and the fact that public maternal services should now be free. Most women had not paid to receive ANC or PNC, although two women discussed paying extra money to cut long queues for ANC:

“You must pay if you want the health service faster [discussing ANC], otherwise you must wait in queue for your turn.” (Woman A, location 2)

All participants were aware of the JSY scheme, and this was identified as the main facilitating factor for institutional delivery in eight interviews. However, only 6 of 12 women eligible for JSY payment said it covered the full costs of delivery, with the rest paying over 1400Rs (US$ 20) for the combined cost of transport, ASHA or ANM help, and medication. One woman discussed how the combined costs of her (uncomplicated) delivery had added up to over 5000Rs (∼US$ 71). Another participant said a determining factor for her home delivery had been the knowledge the JSY would not cover her incurred costs:

“There are many more charges and the JSY is not sufficient … you have to pay money to receive services at every point.” (Woman B, location 1)

Most incurred costs were during transport to hospital or payments to the ASHAs or ANMs. Seven of the women had paid the ASHA 100–500Rs (∼US$ 1.5–7) to accompany her to hospital (a service the ASHA should provide free and for which she is paid 600Rs (∼US$ 9) by the Government) and most women had expected to pay this.

It was also common to pay ANMs during delivery; eight women described paying the multiple ANMs who cared for them 200–500Rs (∼US$ 3–7) each. Whilst one woman described choosing to pay this due to her pleasure in having a son, most women described the payments as “forced”:

“I had to give 1000Rs (~US$ 14) overall during and after delivery or they say they will not treat me … the nurses are not listening or taking care of me properly. However, if we give money they take care of us properly.” (Woman C, location 6)

Another woman described travelling to hospital during delivery and being asked for 500Rs (∼US$ 7) from ANMs to enter. The woman did not have this and so had to return home to borrow a friend's money before being allowed to enter the facility:

“if I had not paid they would have made me come home again.” (Woman C, location 2)

Only one woman received the JSY payment easily; most received the cheque two to three months after delivery (the payment should arrive within seven days). For most, the barrier to receiving payment was not owning a bank account; opening an account took time and often required documents they did not own. However, four women discussed receiving delayed payments even with the required bank account/documents. One woman received no payment, even after returning to the hospital several times to enquire why. She discussed the possibility of discrimination:

“People think us dirty … I am low caste so no one listens when I ask anything. If I was higher caste maybe I would have received the money.” (Woman B, location 1)

Information

Twelve women identified poor access to information relating to maternal healthcare in their communities as a barrier:

“we need more information … on everything.” (Woman C, location 3)

The women wanted more information on; “how to access maternal care”, “how to have a healthy child”, “how to organise emergency care” and “an ambulance phone number” (see previous). Three women commented that staff appeared to prioritise child immunisations over other agendas:

“ASHA tells us about child immunisations, but not anything to do with myself or treating our children after birth.” (Woman A, location 5)

Four women commented that the ASHA did not provide them with enough information:

“ASHA gave information on JSY payment only … not on where delivery should take place or how to organise emergency care.” (Woman C, location 4)

“… now the ASHA sometimes comes but she does not give information on anything … there is no way to get it.” (Woman B, location 2)

For the women living in urban slums, this deficiency of information appeared more extreme as they also had no ASHA:

“there is no information … I don't know how to get information, or who I would ask … no one here knows anything really.” (Woman B, location 4)

Acceptability

Four women discussed a change in the cultural acceptability of institutional delivery as a facilitating factor in the increased utilisation of maternal services:

“Three years ago I gave birth at home because it was the tradition - now times have changed and I can get all the facilities I need and they are much better … if I gave birth now I would give birth in a hospital.” (Woman B, location 1)

However, one woman described how her mother-in-law had barred her from hospital as she believed she could offer better care herself because:

She thinks “it is the traditional way to give birth at home”. (Woman C, location 5)

A barrier to one woman accessing delivery care were the rules of her local PHC; she was not allowed to have her family present during her first birth:

“I was in pain and scared … I wanted my family with me but the nurses, they would not let them stay with me.” (Woman B, location 2)

For this reason, she had chosen to deliver her subsequent two children at home.

Quality

Few women discussed the general quality of services or facilities during ANC/delivery/PNC as either a facilitating factor or barrier to healthcare. Participants mostly felt the quality was sufficient, had improved over recent years and was:

“better than home treatment.” (Woman B, location 3)

However, four women commented on the general “poor quality” of PHC facilities and several discussed poor cleanliness, cramped conditions, long waits for ANC and slow PHC service.

Discrimination on the grounds of both caste and socio-economic status was commented on in five interviews. One woman queried whether her caste was the major factor contributing to her unpaid JSY payment (as previously quoted) and several women perceived that ASHAs performed fewer regular visits to SC women (see previous) or avoided SC areas:

“It would be helpful to have an ASHA that visited but I think they avoid SC areas … I’m not sure why.” (Woman B, location 4)

Perceptions of the quality of care received from staff varied. Three women were content with the care received from staff:

“the nurses treated me respectfully throughout.” (Woman B, location 3)

However, more often the women had a contrasting opinion that nurses were: “not respectful” or “not kind” (discussed in seven interviews), although no women specifically attributed this to caste.

Additionally, three women discussed only being treated at the PHC after women of higher caste:

“I am a Dalit. First they take care of high caste people. I am poor, illiterate and I can't pay … they will treat high caste first.” (Woman C, location 2)

One positive aspect, however, was that no participant described discrimination from healthcare workers in the form of “Untouchability” (in which higher castes refuse to touch SCs due to fear of contamination). Previous literature described healthcare workers refusing to examine SC mothers/babies and segregating mothers on the wards by caste.Citation30 However, the consensus was that such practices have become relatively obsolete in the context of Bihar.

Discussion

The main facilitating factors included three NRHM programmes (the introduction of ASHAs, the JSY and JSSK) as well as a general change in the cultural acceptability of institutional delivery. The main barriers discussed included not enough ASHAs (inadequate numbers in rural areas, none in urban areas), poor access to information (including how to contact emergency care), the cost of transport and unauthorised charges from healthcare staff.

The national average rates from NFHS-4 (2015–6) show that 51% of women receive the WHO-recommended 4+ ANC check-ups, 79% deliver institutionally, and 63% receive PNC.Citation17 It is not possible to compare national service utilisation rates with service utilisation in this small sample, but our study reveals poor use of services. The interviewed women who delivered in health facilities left without a check-up in the facility, the majority received no PNC and none received the WHO-recommended 4+ PNC check-ups.Citation27 All participants in this study returned home within a few hours following delivery, likely due to the “cramped”, “unclean” facilities they described. These findings suggest that basic PNC is not available in hospitals and health facilities, making home-based PNC more vital. It is currently expected that an ASHA should provide six or seven home postnatal visits (for which she is paid on completion) and an ANM should carry out at least one home visit.Citation28 With the majority of maternal (and neonatal) deaths occurring after delivery (50% of maternal deaths occur in the first 24 hours after delivery and 65% in the first 7 days),Citation31 it seems that PNC monitoring activities are not happening enough to prevent these incidents.

One positive aspect highlighted in this study is the value of the ASHA programme, despite its limitations. In rural areas, ASHAs were an important facilitating factor. In the urban slums, there appeared to be no alternative form of information dissemination, leading to poor understanding of the health system, and reduced rates of ANC, PNC and institutional delivery. It was unclear whether the proposed USHA scheme had been fully implemented or not, or whether the USHAs had already started but were avoiding SC urban slums (possibly due to discriminatory factors). Nevertheless, there appears to be an urgent need for implementation of the USHA scheme to reduce this inequity in access to services.

SC women seemed dependent on ASHAs. This could be due to several factors, including the geographical and caste segregation, reduced access to information (poor access to media sources such as the internet and telephones) and reduced literacy levels.Citation8 Conversely, their dependence on ASHAs may mean that the ASHA programme's failings are also their biggest barriers to care. A common view was that ASHAs were not providing enough information and that importance was weighted towards child immunisation, rather than conveying other desired information (such as how to set up a bank account, receive PNC or organise EmOC). Knowledge of the public ambulance service was very poor, and no participant understood how to get one, leading to home deliveries. This is key information that should be prioritised by the ASHA programme in enabling SC women to access EmOC; and vital if maternal outcomes are to be improved.

Another area of concern is the payments SC women are making to receive healthcare that should now be free. These payments may be also extracted from women of other castes. It is unclear from this research whether SC women are being specifically exploited. However, payments represent an increased barrier to care for the SC women due to their increased poverty levels, suggesting a need for changes in the training, supervision and accountability of these health workers. Whilst the ASHA's role is supposed to be mainly voluntary, a 2010 study found 73% of ASHAs in Bihar considered the financial incentives they received inadequate for the job. ASHA incentives have changed little in the past ten years.Citation32 ASHAs usually work only 60–70% of the hours in an average work week.Citation32 Perhaps certain ASHA incentives need to be increased. The current incentive for completion of six or seven home PNC visits is only 250 Rs (∼US$ 3.5), proportionally much less than their other incentives, and potentially a major factor in why these visits are not happening.Citation28 This could decrease the need for ASHAs to request extra payments from women who can least afford them. However, as change in practice may take time and is likely affected by complex societal factors, a more pragmatic solution may be that the JSY cash transfer amounts be increased, although there are also documented limitations to the JSY.Citation33

The general consensus was that ASHA's visits were too brief and irregular, perhaps due to a shortfall in ASHAs. The national protocol is for one ASHA per 1000 population, but in Bihar, the coverage is only 0.8 per 1000.Citation34 It was perceived that ASHAs avoided SC areas, so in SC areas this ratio is potentially even lower. It could be argued that these women have both an increased health need and increased dependence on ASHAs, and so perhaps the ASHA ratios could be increased in SC areas. Additionally, ASHAs are supposed to be recruited from each individual community, to ensure there would always be an ASHA living locally, from the same population. For the women in this study, this does not appear to be the case, as several discussed the ASHA living far away. In discussions with healthcare workers, they believe this to be due to the relatively lower literacy levels of SC women, as the ASHA's role requires a higher level of education. However, SC literacy levels have risen rapidly in recent years (48.6% SC in Bihar were literate in 2011]).Citation35 There should now be acceptable numbers of educated SC women from which to recruit ASHAs, and this needs to be better imposed to ensure that SC are represented in the ASHA that serve them.

This study has some limitations. It involved interviews with SC women only, so it is difficult to know whether findings would have been similar if elicited from non-SC women of a similar poverty status. However, our study did elicit information suggesting specific discrimination against SC women (see findings), suggesting there are key differences. Participants were recruited through ASHAs and block managers, which may have introduced selection bias by excluding the most marginalised women, who may not have contact with such individuals. This may also have contributed to response bias as women known to ASHAs and block managers may be less likely to experience or articulate negative aspects. In addition, we interviewed some women at a PHC/Anganwadi Centre, contributing to the same response bias. However, some interviews were at women's homes and we reduced potential bias by making all interviews private, with assured anonymity and confidentiality. We also excluded women who had delivered the same year or who were less than 21 years old, who may have had recent or different (possibly more negative) perspectives.

Conclusion

We conclude that SC women in Bihar may be inequitably served by maternal health services, and they may also be facing discrimination within what should be a universal service. Barriers to care highlighted in this study include limited PNC and unauthorised payments to healthcare staff. To enable improvements in both quality and frequency of PNC, we recommend research into why ASHAs and ANMs are not fulfilling their expected role of providing PNC check-ups and whether ASHA and ANM incentives to encourage participation in areas such as PNC visits should be increased. We also recommend further research into demands for payments from healthcare staff, the development of “anti-corruption” training modules for ASHAs and ANMs, as well as improved line monitoring of health workers through block managers to increase accountability for corruption.

Finally, the ASHA programme, whilst clearly vital, could be improved. A checklist containing the care ASHAs should be providing (including PNC and how to contact EmOC) could be developed and audited by ASHA facilitators, helping to address the lack of information the women receive about health services. Additionally, auditing of ASHA coverage in SC areas should be done to assess whether there is lower coverage and whether ASHAs are avoiding SC areas. Auditing of SC ASHA representation could also help to assess whether SC women are equitably represented by ASHAs from their local community. Finally, we suggest increasing ASHA ratios in SC areas above the standard levels, to help address the barriers to healthcare faced by SC women.

ORCID

Parisa Patel http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0053-3635

References

- Maternal mortality ratio (modeled estimate, per 100,000 live births) [Internet]. Maternal mortality ratio (modeled estimate, per 100,000 live births) Data. WHO; 2016 [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT?locations=IN

- Special Bulletin on Maternal Mortality in India 2014–16. [Internet]. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner India. Government of India. [cited 2018 May 18] Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-Common/Sample_Registration_System.html

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Health Mission. [Online] 2017. [cited 2018 Apr 18] Available from: http://nhm.gov.in/

- Delivery Care (Institutional Deliveries) [Internet]. UNICEF DATA. 2013 [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: http://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/delivery-care/

- Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian S. Health care and equity in India. Lancet. 2011;377:505–515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61894-6

- USAID. India’s Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A) Strategy. p9 [Internet] [PDF] 2014. [cited 2018 Apr 18] Available from: http://www.mchip.net/sites/default/files/RMNCH+A%20in%20India.pdf

- GBD. Maternal mortality collaborators. Global, regional and national levels of maternal mortality 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease 2015. Lancet. 2015;388:1775–1812. [Internet] [PDF] 2016 [cited 2018 Apr 18] Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(16)31470-2.pdf

- Sabharwal SN, Sonalkar W. Dalit women in India: at the crossroads of gender, class and caste. Glob Just Theory Pract Rhetor. 2015;8:44–73.

- Sanneving L, Trygg N, Saxena D, et al. Inequity in India: the case of maternal and reproductive health. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:19145. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.19145

- Who are Dalits? [Internet]. Navsarjan Trust. 2014 [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: https://navsarjantrust.org/who-are-dalits/

- Primary Census Abstract: Data Highlights. [Internet] [PDF] Census of India; 2011. [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/PCA/PCA_Highlights/pca_highlights_file/India/1Cover_page.pdf

- Panagariya A, More V. Poverty by social, religious & economic groups in India and its largest states 1993–94 to 2011–12. New York: Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy; 2013.

- Iyengar K, Iyengar SD, Suhalka V, et al. Pregnancy-related deaths in rural Rajasthan, India: exploring causes, context, and care-seeking through verbal autopsy. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27:293–302.

- Bhanderi MN, Kannan S. Untreated reproductive morbidities among ever married women of Slums of Rajkot City, Gujarat: the role of class, distance, provider attitudes, and perceived quality of care. J Urban Health. 2010;87:254–263. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9423-y

- India: national family health survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06. India: national family health survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2007.

- India: national family health survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16. India: national family health survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2016.

- Gupta SK, Pal DK, Tiwari R, et al. Impact of Janani Suraksha Yojana on institutional delivery rate and maternal morbidity and mortality: an observational study in India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;30:464–471. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v30i4.13416

- Population Enumeration Data (final population). [Internet] Office of the Registration General and Census Commissioner, India. 2011 [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/population_enumeration.html

- Purnia District Population, Bihar – Census India. [Internet] Census India. 2011. [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: https://www.censusindia2011.com/bihar/purnia-population.html

- Annual Health Survey 2012–13 Fact Sheet [Internet]. Census of India: Annual Health Survey 2012–13 Fact Sheet. [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/AHSBulletins/AHS_Factsheets_2012_13.html

- List of High Priority Districts (HPDS) in the Country. [Internet] Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=118620

- Roy M. Nutrition in adolescent girls in South Asia. Br Med J. 2017;357:J1309.

- Maternal Mental Health & Child Health and Development. [Internet] [PDF] WHO. [cited 2018 Apr 18]. 2008.

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. Los Angeles (CA): Sage; 2004. p. 193.

- AAAQ framework – The Danish Institute for Human Rights [Internet] [PDF]. [cited 2018 Apr 18].

- PMNCH. PMNCH Knowledge Summary #23 Human Rights and Accountability [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2013 [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/summaries/knowledge_summaries_23_human_rights_accountability/en/

- Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2015. [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/imca-essential-practice-guide/en/

- Home Based Newborn Care-Operational Guidelines. [Internet] [PDF] Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2011 [cited 2018 Apr 18].

- ASHA. [Internet]. National Urban Health Mission; 2014 [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: http://nuhm.upnrhm.gov.in/nuhm/ASHA.html

- Sabharwal N, Sharma S, Diwakar G, et al. Caste discrimination as a factor in poor access to public health service system. J Soc Inclu Stud. 2009;1(1):148–169.

- Postnatal Care Module: 1. Postnatal Care at the Health Post and in the Community [Internet]. Postnatal Care Module: 1. Postnatal Care at the Health Post and in the Community [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: http://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=335&printable=1

- Bajpal N, Dholakia R. Improving the performance of accredited social health activists in India. New York: Columbia Global Centres; 2011 [cited 2018 Apr 18]. p. 40–42.

- Das A, Rao D, Haopian A. India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana: further review needed. Lancet. 2011;377:295–296. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60085-8

- Update on ASHA Programme. [Internet] [PDF] Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2016 [cited 2018 Apr 18].

- Scheduled Caste Population-Census 2011. [Internet] Census 2011 [cited 2018 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.census2011.co.in/scheduled-castes.php