Abstract

Nepal has one of the highest maternal and neonatal mortality rates among low- and middle-income countries. Nepal’s health system focuses on life-saving interventions provided during the antenatal to postpartum period. However, the inequality in the uptake of maternity services is of major concern. This study aimed to synthesise evidence from the literature regarding the social determinants of health on the use of maternity services in Nepal. We conducted a structured narrative review of studies published from 1994 to 2016. We searched five databases: PubMed; CINAHL; EMBASE; ProQuest and Global Index Medicus using search terms covering four domains: access and use; equity determinants; routine maternity services and Nepal. The findings of the studies were summarised using the World Health Organization’s Social Determinants of Health framework. A total of 59 studies were reviewed. A range of socio-structural and intermediary-level determinants was identified, either as facilitating factors, or as barriers, to the uptake of maternity services. These determinants were higher socioeconomic status; education; privileged ethnicities such as Brahmins/Chhetris, people following the Hindu religion; accessible geography; access to transportation; family support; women’s autonomy and empowerment; and a birth preparedness plan. Findings indicate the need for health and non-health sector interventions, including education linked to job opportunities; mainstreaming of marginalised communities in economic activities and provision of skilled providers, equipment and medicines. Interventions to improve maternal health should be viewed using a broad ‘social determinants of health’ framework.

Résumé

Le Népal a l’un des taux de mortalité maternelle et néonatale les plus élevés des pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire. Le système de santé népalais se concentre sur des interventions vitales de la période prénatale jusqu’au post-partum. Néanmoins, l’inégalité du recours aux services de maternité est gravement préoccupante. Cette étude visait à synthétiser les données des publications relatives aux déterminants sociaux de la santé sur l’utilisation des services de maternité au Népal. Nous avons conduit un examen narratif structuré des études publiées de 1994 à 2016. Nous avons procédé à des recherches dans cinq bases de données : PubMed ; CINAHL ; EMBASE ; ProQuest et Global Index Medicus en utilisant des termes couvrant quatre domaines : l’accès et l’utilisation ; les déterminants de l’équité ; les services de maternité de routine ; et le Népal. Les conclusions des études ont été synthétisées au moyen du cadre de travail de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé sur les déterminants sociaux. Un total de 59 études ont été analysées. Nous avons identifié un éventail de déterminants socio-structurels et de niveau intermédiaire, comme facteurs ayant facilité ou entravé le recours aux services de maternité. Ces déterminants étaient : la condition socio-économique plus élevée ; l’instruction ; les ethnicités privilégiées comme les Brahmanes/Chhetri, les personnes de confession hindoue ; la facilité d’accès géographique ; l’accès aux transports ; le soutien familial ; l’indépendance et l’autonomie des femmes ; et un plan de préparation à la naissance. Les conclusions révèlent la nécessité d’interventions des secteurs de la santé et d’autres, notamment : l’éducation articulée sur les possibilités d’emploi ; l’intégration des communautés marginalisées dans des activités économiques ; et la mise à disposition de prestataires formés, d’équipements et de médicaments. Les activités destinées à améliorer la santé maternelle devraient être examinées en utilisant un large cadre de « déterminants sociaux de la santé ».

Resumen

Nepal tiene una de las tasas más altas de mortalidad materna y neonatal de los países de bajos y medianos ingresos. El sistema de salud de Nepal se centra en intervenciones para salvar vidas, realizadas durante el período prenatal a posparto. Sin embargo, la desigualdad en la aceptación de servicios maternos es una gran preocupación. Este estudio buscó sintetizar la evidencia del material publicado sobre los determinantes sociales de la salud en el uso de los servicios maternos en Nepal. Realizamos una revisión narrativa estructurada de estudios publicados desde 1994 hasta 2016. Realizamos búsquedas en cinco bases de datos: PubMed; CINAHL; EMBASE; ProQuest y Global Index Medicus, utilizando términos de búsqueda que abarcaron cuatro áreas: acceso y uso, determinantes de equidad, servicios de maternidad rutinarios y Nepal. Los hallazgos de los estudios fueron resumidos utilizando el marco de Determinantes Sociales de la Salud, creado por la Organización Mundial de la Salud. Revisamos 59 estudios en total. Identificamos una variedad de determinantes socioestructurales y de nivel intermediario, ya sea como factores facilitadores, o como barreras, para la aceptación de los servicios de maternidad. Los determinantes eran: mayor nivel socioeconómico; nivel de escolaridad; etnias privilegiadas como brahmins/chhetris, personas que siguen la religión hindú; geografía accesible; acceso a transporte; apoyo familiar; autonomía y empoderamiento de las mujeres; y plan de preparación para el parto. Los hallazgos indican la necesidad de realizar intervenciones en el sector salud y en otros sectores, por ejemplo: educación vinculada con oportunidades de empleo; integración de comunidades marginadas en actividades económicas; y provisión de prestadores de servicios calificados, equipos y medicamentos. Las intervenciones para mejorar la salud materna deben ser consideradas utilizando el marco general de ‘determinantes sociales de la salud’.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, Nepal has made remarkable progress in reducing its maternal mortality ratio (MMR), from 539 to 259 per 100,000 live birthsCitation1,Citation2 and neonatal mortality rate (NMR), from 53 to 21 per 1000 live births.Citation1 Despite this progress, Nepal’s MMR and NMR are the highest among other South Asian countries.Citation3,Citation4 Furthermore, within the country, significant health disparities exist by ethnicity, caste, socioeconomic status and geographical region.Citation5,Citation6 The major causes of maternal deaths are preventable and include postpartum haemorrhage, eclampsia, preeclampsia, puerperal sepsis and unsafe abortion.Citation5 Similarly, preventable causes of neonatal deaths are preterm-related complications, intrapartum-related complications and severe infections.Citation2 Many of these deaths can be prevented with adequate access to routine maternity services such as antenatal care (ANC), safe delivery and postnatal care (PNC). These routine services are proxies for specific maternal interventions. For instance, during ANC, women should receive tetanus toxoid injection, iron-folic acid tablets, counselling and advice on institutional delivery.Citation7 Similarly, during institutional delivery, women should receive interventions like the active management of labour and delivery.Citation7,Citation8 During PNC visits, mothers and newborns are checked for danger signs, and mothers are counselled on nutrition, postpartum family planning and breastfeeding.Citation9

Despite the implementation of Safe Motherhood initiatives since 1996, and the Maternity Incentive Scheme since 2005, the population level coverage of services remains low.Citation10,Citation11 The Nepal Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) 2011, for example, reported that only half of pregnant women have at least four ANC (4ANC) visits, and only one-third of women receive skilled care during childbirth, or PNC.Citation6 Inequalities in access to these services are evident. Data from Joshi et al in 2011 reported that the uptake of 4ANC was highest in women in the wealthiest quintile (84%) and those with higher education (93%), and lowest in the least wealthy quintile (28%) and in illiterate women (29%).Citation6

Achieving Nepal’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets to reduce MMR to 70 per 100,000 live births, decrease NMR to less than 10 per 1000 live births and achieve 90% coverage of routine maternity services by 2030 will require focussed strategies that address inequitable access to services and health outcomes.Citation2

The socioeconomic–demographic context

Nepal is a low-income country, heavily reliant on agriculture (33%) and remittances from foreign employment (29%), especially from Gulf countries.Citation12,Citation13 The country’s topography is diverse and divided into three eco-regions: Mountains, Hills and Terai (Plains).Citation14 The Hill and Mountain regions present challenges in ensuring equitable access to services due to their geographical terrain and ethnolinguistic diversity.Citation14 Nepal is one of the most ethnolinguistically diverse countries in the world with 125 castes and 123 languages in a comparatively small geographical area; and with identities based on a combination of religion, ethnicity and caste.Citation14 The Brahmin/Chhetris are the dominant ethnic groups in political spheres and usually reside in the Hills.Citation14,Citation15 While progress has been made in reducing the number of people living in absolute poverty, 25.2% of people in Nepal live on less than $1.25 per day. Dalits (44%) and Indigenous (29%) groups are the poorest.Citation14 In 2011, the adult literacy rate was 57%; more than half of this illiterate adult population are female (53%).Citation14

Minority groups living in Hill and Mountain regions experience poor access to social services due to the topographical terrain and distance, poor transportation, and time taken to reach health facilities.Citation16 The disadvantaged groups of the Terai (Tharus and Muslims) typically have poor health-seeking practices due to low awareness. They experience high out-of-pocket expenditure for health care in Nepal, although the recently introduced national health insurance scheme is believed to have reduced this expenditure, especially among needy people.Citation17

After promulgation of a new constitution in 2015, Nepal was restructured into three levels of government: federal, state and local. The state is divided into seven provinces, subdivided again into 77 districts and 753 local levels. The local-level government has been given more power by the federal and provincial governments to run development activities, including the health sector.Citation18 Given the contextual diversity of the country, the local-level government should design contextual policies and programmes to address the various social determinants of health that affect the underutilisation of maternity services.

Social Determinants of Health as a framework for synthesising determinants of the use of maternity services in Nepal

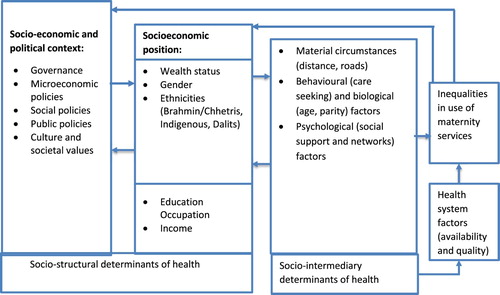

The health of women and children is determined not only by biomedical factors such as maternal age or care-seeking patterns but also by a complex interaction of social attributes.Citation19 The social determinants of health reflect the distribution of resources and power in society and define people’s life circumstances and the contexts in which they undertake their daily activities.Citation20 These determinants produce inequalities in health outcomesCitation20 due to social stratification and unfair distribution of resources and power.Citation21 The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Social Determinants of Health (SDH) frameworkCitation22 is an action-oriented model that can help to identify entry points for interventions to reduce inequalities in health outcomes.Citation22 The framework has three components: (1) the socioeconomic and political context that includes governance and public policies; (2) social and structural determinants, such as wealth, gender, education and ethnicity; and (3) intermediary determinants, which arise from structural determinants (). Intermediary determinants include distance to health facilities, social support, care-seeking practices, age, parity and access to quality services; and these factors are likely to shape health choices and daily living conditions.Citation22

Figure 1. Adapted and modified version of SDH framework 2010Citation22

The SDH framework has the potential to examine factors that shape inequalities in use of maternity services in Nepal and may help to identify where to intervene effectively. Previous review studies have reported on the determinants of the use of routine maternity services.Citation23–25 However, it is rare for studies to systematically synthesise determinants beyond the biomedical and behavioural models. The purpose of this study is therefore to synthesise current evidence on socio-structural and intermediary-level determinants of access and utilisation of maternity services in Nepal.

Methods

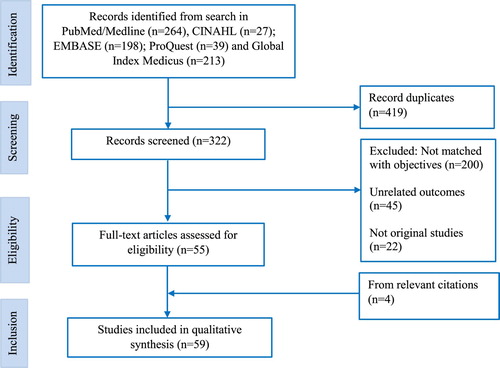

We conducted a structured narrative review.Citation26 Studies were retrieved from five databases: PubMed; CINAHL; EMBASE; ProQuest and Global Index Medicus. The first author, RBK, developed the search strategy, which was independently reviewed and verified by the second author RK. RBK then assessed the titles and abstracts of selected identified studies to evaluate their eligibility. Full-text articles were assessed, discussed within the team and, after consensus, included in the review ().

Search strategy

A total of 38 search terms were developed based on four broad domains: (1) maternity services: Matern*OR obstetric*OR reproductive OR delivery OR prenatal OR “antenatal care” OR “postnatal care” OR postpartum OR postnatal OR neonatal OR newborn OR “continuum of care” OR “Skilled Birth Attendants” OR SBA OR “institutional delivery” OR “essential newborn care”. (2) Equity determinants: Poor OR illiterate OR uneducated OR rural OR remote OR marginalise OR disadvantaged OR Hills OR Mountains OR education OR “Socioeconomic status”. (3) Access and utilisation: utilisation OR access OR use OR factors OR determinants OR barriers OR facilitators OR decisions OR demand OR supply. (4) Nepal: Nepal OR Nepalese. The final search was domain 1 AND domain 2 AND Domain 3 AND domain 4.

Selection criteria

We searched for original peer-reviewed research articles that reported studies focussed on the determinants of routine maternity services (ANC, delivery and PNC by skilled providers) in Nepal. Inclusion criteria were written in the English language; published or data collected after 1994; conducted in Nepal. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were review articles; letter to the editor; commentary and conference posters/proceedings. We used the McGill Mixed Methods Appraisal ToolCitation27 as a guiding framework for the inclusion of studies in this review.

Data extraction and analysis

A template was developed to enable the extraction of relevant data from each eligible study. After reading the selected studies, key findings were extracted into the template including information related to the first author, year of publication, journal name, year of data collection, outcome variables, sample, study design, summary findings. Based on previous studies conducted in China,Citation28 IndiaCitation21 and the United States,Citation29 this review also used the SDH framework to report the findings. In reviewing each article, socio-structural and intermediary determinants of health were identified and categorised into barriers and facilitators.

Results

A total of 59 studies met the eligibility criteria. Of these, 46 articles were primary, small-scale studies conducted in specific geographical settings of Nepal, and 13 articles were further analyses of data from different NDHS (1996, 2001, 2006 and 2011). Forty-eight studies were published after 2006. Half of the studies were conducted in Hill areas and 15 in the Plains. Forty studies were quantitative, 14 were qualitative and 4 used mixed method designs. The majority (53) were published in international journals and 48 were written by a Nepalese first author. Eleven articles were on ANC, 9 focussed on ANC and institutional delivery, 26 were related to childbirth, 6 to PNC and 7 were on ANC, institutional delivery and PNC. Studies related to PNC were primarily focussed on postpartum care for mothers rather than postnatal care for babies.

Social determinants on use of routine maternity services

Of the studies reviewed, none focussed on the broader socio-political level (such as governance and macroeconomic policies). Almost all studies were on the socioeconomic position as socio-structural determinants of health or on socio-intermediary factors. Socio-structural and intermediary-level determinants were categorised as facilitating factors, or as barriers, of maternity service use (). Twenty-three studies cited education and 21 included socioeconomic status as major socio-structural determinants. Similarly, 39 studies included health system factors as intermediary-level determinants.

Table 1. Summary findings as they relate to the structural- and intermediary-level determinants as either facilitators or barriers to using maternity services in Nepal

Structural determinants

According to the SDH framework, structural determinants include wealth status, gender, ethnicity, education, income and occupation. Most of the studies included in this review reported income, education and occupation in a similar context, so we used education as a proxy for income and occupation.

Wealth status

Routine maternity care is free in Nepal and incentivised under some circumstances. Women get NRs 400 (=US$ 4) if they complete 4ANC visits and NRs 1000 (=US$ 10) for transportation, if they deliver babies in health facilities.Citation89 However, associated indirect costs, for instance, days lost from work, food and accommodation, can still be high and unaffordable, resulting in non-use of maternity services. Being in the higher wealth quintile, and family land ownership, were positive factors for using routine maternity services. A study conducted in a Mountain district (Achham) reported that a family with higher land ownership also had higher use of institutional delivery.Citation30 Some studies reported that the frequency of ANC, institutional delivery and PNC was high among women of wealthier families.Citation31,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35,Citation41,Citation63 In other studies, the higher socioeconomic status of the family was the main facilitating factor for the use of maternity services.Citation43–45

Women from families in the lower wealth quintiles, on the other hand, had higher home deliveries. Where there were complications, delayed presentation to health facilities occurred,Citation50 and women also delayed attending for their first ANC visit,Citation42 even in the accessible Terai areas.Citation62 Further analysis of NDHS studies reported that the women of the highest wealth quintile were three times more likely to receive ANC compared to the lowest wealth quintile, which also received poor quality of ANC.Citation35 Moreover, women with low socioeconomic status had experienced financial burdens for maternity care as they had to pay not only for the cost of transportation, accommodation and food, but also lost their earnings due to absenteeism from work.Citation36,Citation37,Citation39,Citation40,Citation47,Citation49 Moreover, fear of an extended stay in hospitals (for women and their caretakers) in case of further complications, associated with additional expenses, deterred uptake of maternity services among the poor.Citation38

Gender

Gendered norms were barriers to women’s control over their resources and health-related decision making.Citation57 Nepalese families are generally patriarchal, meaning that household heads are usually male, and considered as the breadwinner, with more exposure to working outside of the household. Women are typically involved in daily chores at home,Citation60 and often have less access to information about available health services, especially in more traditional households.Citation56 Women who received information from friends and relatives were more empowered in decision making, on economic matters in the family, and also had movement autonomy that improved their uptake of institutional delivery services.Citation39,Citation51,Citation53,Citation55,Citation58 Health-seeking decision-making power emerged from the review as being positively associated with the use of maternity services.Citation35,Citation48 For instance, a study analysing data from NDHS 2011 reported that women who had made at least one of the three decisions regarding their health care, major household purchases and visiting family or relatives, were two times more likely to receive ANC services.Citation35 A study conducted in Kavre (a Hill district) found that 13% of women did not visit a health centre because mothers-in-law did not allow it. Spousal discussion on decision making, on the choice of providers, timing and place of health facilities, contributed to the uptake of ANC.Citation52,Citation53,Citation59 In another paper, a Hindu-caste woman in semi-urban Kathmandu gave a cultural construction of birthing being a “natural” phenomenon that did not require human regulation, with women responsible for childbirth and lactation,Citation57 meaning that women had no control over their health.Citation39 Gender-based domestic violence was common in contexts where women’s husbands were unemployed or addicted to alcohol. For these women, their spousal communication was reported to be mainly centred on daily problems, with less attention given to issues such as pregnancy and delivery care.Citation34 The combination of all or some of these factors implies that women have limited capacity to demand biomedical services from their husbands or mothers-in-law, and therefore follow traditional practices, including giving birth without a skilled birth attendant or not using maternity services.Citation35,Citation39,Citation48,Citation54

Ethnicities and religions

Studies conducted in Bhaktapur and Kavre (Hill districts) found that women of privileged ethnicities (Newar/Brahmin/Chhetri) had higher use of maternity services,Citation61,Citation71 a finding that was consistent with a study in the Brahmin of the Terai.Citation58 Similarly, the continuity and quality of ANC services received by women from advantaged ethnicities were high.Citation35 A study conducted in Chitwan district (in the Plains) reported that Brahmin/Chhetri women often bypassed the local birthing centre, going instead to higher level centres to obtain better quality childbirth services.Citation73

The ethnic (Indigenous or Madhesi) and religious (Muslim) minorities were reported in the literature to have lower ANC visits and institutional delivery compared to the more privileged ethnicities.Citation31,Citation46 Furthermore, Dalits were often reluctant to use institutional childbirth servicesCitation62 and also had a lower frequency of PNC visits.Citation45,Citation61 ANC visits were low among the Tamang of peripheral communities of the Kathmandu Valley and nearby districts.Citation54,Citation72 In Hinduism, postpartum women are not allowed to leave their home until the 11th day, which is a special day for rituals and the naming of newborns, so, for some women in remote areas, this ritual practice means they do not attend for PNC.Citation79 Among Muslims seeking behaviour related to pregnancy and childbirth was poor,Citation31 and other local minority religions (Kirat Mundhum and Christians) had high home delivery rates.Citation31,Citation46

Education

The educational level of women had synergistic impacts on improving their status within households and communities, leading them to be more aware of their health and more informed about where to go when in need of health services.Citation68 A higher level of education of women and their husbands was associated with the use of ANC and other routine maternity services.Citation31,Citation39,Citation70 Higher education in women was positively associated with ANC use and institutional delivery,Citation35,Citation43,Citation65,Citation68 and educated women involved in non-manual work such as office settings, used PNC more than those who worked as manual labourers or in the agricultural sector.Citation45,Citation61 A study conducting further analysis of NDHS 2001 revealed that women with at least a secondary level of education were five times more likely to have ANC and skilled care at birth.Citation52

Halim et al analysed NDHS 2001 data and reported that the more education a woman had, the more she was likely to use maternity services; for example, women with primary, secondary or higher education were 19%, 29% and 48%, respectively, more likely to use ANC services compared with their uneducated counterparts.Citation56 Another study conducted in Jumla (2001) revealed that paternal education greater than the fifth-grade reduced high-risk childbirth practices significantly.Citation69 A randomised control trial conducted in a maternity hospital in Kathmandu reported that educating husband and wife pairs during their visits to ANC clinics was two times more effective in increasing their use of routine maternity services.Citation70 An analysis of NDHS 2011 reported that if the husbands were educated and had non-manual jobs, their wives had higher levels of ANC.Citation35 Similarly, another analysis of NDHS 2006 showed that such women were more likely to take up PNC.Citation43 Likewise, studies in Kavre (Hill district) and Morang (Plains district) reported that education was associated with uptake of SBA services.Citation44,Citation45 Women whose husbands worked as subsistence farmers had low uptake of ANC.Citation54 Secondary or higher education increased women’s use of PNC services fourfold, compared to less educated women.Citation63

Illiterate women often delayed their first ANC visit and usually presented late.Citation36,Citation47 A study conducted in the Plains districts (Kapilvastu and Morang) for example revealed that uneducated women had low levels of institutional deliveryCitation46,Citation62 and findings were similar in Hills districts (Dhading and Illam).Citation64,Citation67 Women with low education who were also unemployed had lower use of maternity services.Citation34,Citation49,Citation66 A decomposition analysis of NDHS 2011 by Nawal et al revealed that maternal illiteracy was a critical contributing factor in the uptake of more than three ANC visits.Citation33

Intermediary determinants

According to the SDH framework, intermediary determinants include material circumstances, biological and behavioural factors, psychosocial factors and health system factors. In our review, the specific major intermediary factors found were distance and travel time to reach health facilities, poor road networks and access to transportation, age and parity of mothers, delayed care-seeking and birth preparedness practices, social support and networks, inadequate human and capital resources and access to quality health services.

Material circumstances

Material circumstances include place of residence, housing, road networks and transport systems. Most of the studies identified distance and transportation as barriers to access maternity services. The absence of road networks or limited means of transportation was also linked to poverty, exacerbating women’s poor access to health facilities.Citation54 Studies reported that women living in urban areas had more PNCCitation63 and ANC, and experienced better quality of care.Citation35,Citation76 Closer proximity to health facilities meant short distances and less travel to reach health facilities, and this was associated with higher use of institutional delivery.Citation65,Citation75

Lengthy travel times and difficult geography were negative predictors of maternity service use.Citation42,Citation45 For remote communities which lacked all-weather road networks, difficulty in accessing services led to higher rates of home delivery.Citation33,Citation47 Most of the studies reported that a lack of transportation meant underutilisation of ANCCitation31 and institutional delivery in remote and rural areas of the country.Citation44,Citation45,Citation48,Citation64,Citation74 Even in the Terai (Kapilvastu district), home delivery was reported to be high because of poor transportation during the rainy season.Citation62 A qualitative study reported that in remote communities, health workers were also unable to make home visits.Citation40 These factors prevented women from reaching referral hospitals when they had complications.Citation49,Citation50,Citation60 Moreover, difficult geographical circumstances increased the financial constraints of poor families when obliged to visit referral hospitals.Citation37

Biological and behavioural factors

Maternal factors including higher parity, large family sizeCitation36,Citation43 and older maternal age were associated with low maternity service utilisation.Citation34,Citation44,Citation45,Citation66,Citation72,Citation73 Neupane et al reported that women of higher parity (four or more) had twice the likelihood of attending their first ANC visit late.Citation36 Older women based their decisions on past experiences and sought care from traditional healers.Citation40,Citation46 Lower parityCitation33,Citation50 and younger (20–25 years) women had a higher uptake of maternity services.Citation30,Citation31,Citation35,Citation54

In some communities, care seeking was influenced by women’s past experiences, for instance, women (and their mothers-in-law) who delivered at home previously wanted future home births.Citation42,Citation60,Citation67,Citation78 Home delivery and delayed decisions to seek care during obstetric complications placed women at greater risk of death,Citation57 and delay in recognising danger signs affected timely care-seeking practices, with care initially sought from traditional birth attendants or Shaman (spiritual) healers, before being referred to health workers.Citation51 Based on their traditional beliefs, many women engaged in potentially harmful self care following home delivery. Such beliefs include considering childbirth as dirty and untouchable, and not allowing postpartum women to eat certain food items such as green vegetables or meat, due to the perceived belief that such food can cause puerperal sepsis.Citation42,Citation56,Citation60,Citation74,Citation79 Some cultural practices may lead to delayed care in case of complications,Citation77 which unintentionally put women at risk.Citation34

Psychosocial factors

Psychosocial support, networks and social stress were identified as influencing factors for use and non-use of maternity services. The support from family members, peers, partners and health service providers influenced the use of ANC services.Citation59 Spousal support while visiting a health clinic during pregnancy increased the chance of receiving ANC and facility-based childbirth services.Citation52 Frequent contact, interpersonal communication and advice from health workers increased the uptake of services.Citation82 Family support during routine or emergency situations was positively associated with uptake of maternity care.Citation53,Citation55,Citation77,Citation80,Citation81

In a few cases, mothers-in-law, based on their pregnancy and delivery experienceCitation39,Citation64 obliged women to give birth at home.Citation34,Citation51,Citation78 A few women perceived institutional delivery to be insecure, non-confidential and stressful.Citation44 They considered childbirth practices as personal or familial matters, and home as a more convenient place for childbirth than health institutions.Citation52 In remote areas, women had spiritual beliefs to please the gods, requiring living in a separate house, or in dark rooms so that others could not see them during the few days postdelivery. Such beliefs undermined safety, created risk and prevented the uptake of standard pregnancy and institutional delivery services.Citation69,Citation79,Citation83

Health system factors

Health service delivery and uptake are intricately linked with the local context and supply of health services. Birth preparedness packages effectively raised awareness, informed on service availability and promoted institutional deliveryCitation53,Citation77,Citation84,Citation85 including readiness for referral in case of emergency.Citation87 Counselling on complications of pregnancy, home visits by health workers and media exposure with pregnancy-related information increased the use of maternity services.Citation44,Citation45 Previous pregnancy complications sometimes triggered service use in subsequent pregnancy and labour.Citation44,Citation45,Citation52,Citation71,Citation75 Similarly, uptake of services within the continuum of care increased use of services, meaning that women who completed 4ANC visits were more likely to receive SBA services,Citation32,Citation61,Citation64,Citation65 and women who gave birth in the presence of a skilled attendant had a higher chance of receiving PNC visits.Citation45,Citation63 Good quality ANC services, with adequate counselling on birth preparedness and complication readiness (identification of danger signs, a health facility, transport, blood donor), was found to be directly associated with the use of institutional delivery or PNC.Citation44,Citation72,Citation76 Pregnant women who felt they had been treated with respect during ANC were more likely to deliver their babies at health institutions.Citation51,Citation81 Client satisfaction attributes, such as less waiting time, free services, the availability of a bed, and polite and competent service providers, were positive predictors of maternity service use.Citation58,Citation86,Citation88

The most common health system barriers were inadequate birth preparedness,Citation39,Citation60,Citation66 poor quality of care, inadequate infrastructure, perceived non-competent health workers and midwives,Citation41,Citation73 inadequate or no staff accommodation, lack of water and sanitation, no privacy and poor communication with service users, which all contributed negatively to the use of maternity services.Citation60,Citation78,Citation82 Adverse past experiences, including scolding by service providers and health workers’ negative attitudes and behaviours towards women, had deterred the use of maternity services.Citation40,Citation42,Citation44 Poor satisfaction with counselling decreased the use of SBA services.Citation50 The women who delivered at home often had limited birth preparedness and complication readiness and were also more likely to report pre-lacteal feeding practices.Citation57,Citation74 Women who had not made ANC visits were found to have delayed recognition of danger signs, and also had poor hygiene practices during childbirth and in the postpartum period.Citation69 Cost was also a barrier to access to maternity services, and deliveries in private hospitals increased the cost for many women, especially women from disadvantaged families.Citation47,Citation49,Citation50

Discussion

This review revealed that the use of maternity services is influenced by a complex interplay of social and intermediary factors that correspond to the WHO Social Determinants of Health framework. The structural determinants which acted as facilitating factors were household wealth, higher educational status of women and their husbands, advantaged ethnicities (mediated by the support of family or husband),Citation53 accessible health facilities and women having a birth preparedness plan.Citation33,Citation39,Citation68,Citation72 Conversely, structural determinants which were barriers were poverty, marginalised ethnicities, illiteracy and low status of women in the family. Additionally, socio-intermediary level barriers elicited included delayed care seeking,Citation64,Citation79 disrespectful maternity care, remoteness and poor transportation/road networks.Citation34,Citation69,Citation70,Citation81 Despite the rapid increase in the uptake of routine maternity services over the last two decades, these social determinants of health are still relevant and affect the lower uptake of services among disadvantaged people in Nepal.Citation16,Citation33,Citation75

The social-structural level determinants contribute to inequities due to the unfair distribution of power, money and resources that create poverty, marginalisation, exposure and vulnerabilities towards ill health.Citation22,Citation33 Furthermore, the dynamics of power and positions create unequal social stratification in the society which leads to poor uptake of health care services.Citation22 Poverty and illiteracy trap illiterate women into a vicious cycle of intergenerational poverty.Citation90 These factors mediate through the intermediary-level determinants of long distance to health facilities, harmful care practices, irregular and poor quality of available services, and compound inequalities in uptake of maternity services.Citation46

The multiple layers of structural and intermediary-level determinants, acting as facilitators and barriers, are the causes of inequitable use of maternity services in Nepal and elsewhere.Citation91 Some social groups have multiple advantages and others multiple disadvantages. Women living in urban areas, those with high socioeconomic status and who have completed higher education can enjoy quality maternity services. On the other hand, illiterate women who live in remote areas and belong to the lowest wealth quintile and to ethnic minority groups have low access and use of maternity services. Despite this situation, many maternal health programmes have been implemented with a “one-size-fits-all” approachCitation11,Citation33 which might not be appropriate considering the diversity of Nepal. These programmes are effective in improving the overall coverage of services, but advantaged groups benefit more compared to their disadvantaged counterparts. For instance, maternity incentives were provided for women who delivered at health facilities in Nepal. After implementation of this scheme, the increase in use of SBA services was significantly higher among the highest wealth quintile compared to the lowest wealth quintile, so widening the equity gap.Citation92

Apart from sustaining high advocacy and commitment to the policies and programmes formulated thus far, attention should be given to addressing the multiple social and intermediary barriers to accessing maternity services among the poorest. These barriers need to be addressed locally, given the diversity of Nepalese society. As local-level governments have more authority on local development and service delivery, there are opportunities to address various contextual social determinants of health. Local-level government units can consider structural and intermediary determinants while designing health and other sectoral policies according to the prevailing context. For instance, local units can address proximal health system factors including hiring skilled health providers or equipping health facilities. Additionally, if the local-level government was to prioritise roads or bridges to health facilities, such development efforts will make distance to health facilities less of a problem. Financial incentives can also be provided to socio-economically marginalised women.

This review highlights the socio-structural privilege (or disadvantage) among certain groups in Nepal. Our findings are comparable with studies conducted in ChinaCitation28 and IndiaCitation21 using the SDH framework, which also showed poor utilisation among urban migrants and adolescents. Nepal is also experiencing rapid rural to urban migration and a high adolescent fertility rateCitation54; however, relevant studies focussing on the utilisation of maternity services among the urban poor and adolescents were not found.

To our knowledge, this is the first review on this topic, using the SDH framework to synthesise the determinants of routine maternity service use in Nepal. This review sheds light on intersectional marginalisation and identifies important programmes and research gaps. The review is unable to estimate the extent of inequity quantitatively. The reasons behind this were because we took multiple outcome variables (ANC, delivery and PNC) and because we included studies which adopted various quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods. We conducted a narrative review of the evidence using the McGill Mix Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT)Citation27 eligibility criteria. The MMAT specifies some methodological criteria for diverse types of studies but does not specify quality ratings for studies or evidence, so we did not do a quality assessment. The timeframe of review is long (1994–2016), and during this time there may have been changes in social determinants, health care seeking and utilisation. DHS data, however, frequently reports on some of the structural determinants and we know from NDHS 2016Citation1 that equity gaps remain across the decades, although changes may not be uniform nationwide.

Research implications of this review include the following. First, we identified the multiple factors that lead to marginalisation, but further quantitative analysis would identify to what extent women with multiple jeopardies receive maternity services. Second, almost all studies focussed on contact coverage such as ANC, PNC or institutional delivery. There is a lack of evidence on what happens to women when they reach the health facility, for example in relation to evidence on the effective coverageCitation93 of interventions such as tetanus toxoid injections, iron supplementation or counselling for institutional delivery.

We identified various social determinants of health affecting low utilisation of routine maternity services. For monitoring of services, policy makers and programme managers rely on surveys like DHS, conducted every 5 years, or other small-scale studies. The national routine Health Management Information System (HMIS) does not collect disaggregated data on uptake of maternity services such as ethnicities, wealth, level of education or distance to health facilities. If such social determinants of health are included in the HMIS, progress on the uptake of routine maternity services can be monitored yearly or even at shorter periods. Such disaggregated data on the uptake of maternity services can help to refocus the scarce resources and priorities which could ultimately be used to improve equity. Such disaggregated data could help formulate targeted strategies and interventions for disadvantaged, marginalised and underserved groups.

Conclusion

The WHO’s SDH framework was useful in highlighting the contextual impediments to accessing maternity services in Nepal, at the socio-structural and socio-intermediary levels. Findings indicate the need for the development of non-health sector interventions such as education, local development and inclusion of economically marginalised communities in income generating activities. Similarly, improving daily living conditions through access to transportation and family support for care seeking of health services can increase the utilisation of health services. Demand-side interventions are not enough, and supply-side, health service specific interventions are also required, including the deployment of trained, skilled health personnel, supplies of required commodities and focus on the quality of services. Improving the equitable uptake of maternity services needs to be considered using the broader lens of the social determinants of health.

Acknowledgements

The first author would like to acknowledge previous and current advisors of his doctoral research project for their encouragement in the literature review and writing this paper. He also would like to acknowledge Scott Macintyre for support in the literature search.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ministry of Health, Nepal; New ERA; and ICF. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Kathmandu: Ministry of Health, Nepal; 2017.

- Pradhan YV, Upreti SR, Pratap KC N, et al. Newborn survival in Nepal: a decade of change and future implications. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(Suppl. 3):iii57–iii71. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs052

- Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):462–474. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00838-7

- Wang H, Liddell CA, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9947):957–979. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60497-9

- Suvedi BK, Pradhan A, Barnett S, et al. Nepal Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Study 2008/2009. Kathmandu: Family Health Division, Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health, Government of Nepal; 2009.

- Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) [Nepal], New ERA, ICF International Inc. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Kathmandu and Calverton (MD): Ministry of Health and Population, New ERA, and ICF International; 2012.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

- Paudel D, Shrestha IB, Siebeck M, et al. Neonatal health in Nepal: analysis of absolute and relative inequalities and impact of current efforts to reduce neonatal mortality. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1239. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1239

- Child Health Division, Family Health Division, Save the Children. A synthesis of recent studies on maternal and newborn survival interventions in Nepal. Kathmandu: Child Health Division and Family Health Division, Ministry of Health and Population; 2014.

- Ratha D, Eigen-Zucchi C, Plaza S. Migration and remittances Factbook 2016. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications; 2016.

- Nepal S. Importance of financing for Nepalese agriculture and economic development. The University of Bergen; 2015.

- Central Bureau of Statistics N. National population and housing census 2011. National Report; 2012.

- Joshi SR, editor. District and VDC profile of Nepal: a socio-economic database of Nepal. Kathmandu: Intensive Study and Research Centre; 2010.

- Khatri RB, Dangi TP, Gautam R, et al. Barriers to utilization of childbirth services of a rural birthing center in Nepal: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177602

- Mishra SR, Khanal P, Karki DK, et al. National health insurance policy in Nepal: challenges for implementation. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(1):28763. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.28763

- Constituent Assembly Secretariat. Constitution of Nepal 2015. Kathmandu: Constituent Assembly Secretariat; 2015.

- López N, Gadsden VL. Health inequities, social determinants, and intersectionality. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2016.

- Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, et al. Health CoSDo. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6

- Sanneving L, Trygg N, Saxena D, et al. Inequity in India: the case of maternal and reproductive health. Glob Health Action. 2013;6(1):19145.

- World Health Organization. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Karkee R, Lee AH, Binns CW. Why women do not utilize maternity services in Nepal: a literature review; 2013.

- Simkhada B, Van Teijlingen E, Porter M, et al. Major problems and key issues in maternal health in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2006;4(2):258–263.

- Raj BY. Maternal health services utilisation in Nepal: progress in the new millennium? Health Sci J. 2012;6(4):618–633.

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inform Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002

- Yuan B, Qian X, Thomsen S. Disadvantaged populations in maternal health in China who and why? Glob Health Action. 2013;6:19542. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.19542

- Szaflarski M. Social determinants of health in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;41:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.06.013

- Maru S, Rajeev S, Pokhrel R, et al. Determinants of institutional birth among women in rural Nepal: a mixed-methods cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:252. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1022-9

- Tripathi V, Singh R. Ecological and socio-demographic differences in maternal care services in Nepal. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1215. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1215

- Bhatta DN, Aryal UR. Paternal factors and inequity associated with access to maternal health care service utilization in Nepal: A community based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130380

- Nawal D, Goli S. Inequalities in utilization of maternal health care services in Nepal. Ethn Inequal Health Soc Care. 2013;6(1):3–15. doi: 10.1108/EIHSC-11-2012-0015

- Lama S, Krishna AK. Barriers in utilization of maternal health care services: perceptions of rural women in eastern Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2014;12(48):253–258.

- Joshi C, Torvaldsen S, Hodgson R, et al. Factors associated with the use and quality of antenatal care in Nepal: a population-based study using the demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-94

- Neupane S, Doku DT. Determinants of time of start of prenatal care and number of prenatal care visits during pregnancy among Nepalese women. J Commun Health. 2012;37(4):865–873. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9521-0

- Dhakal S, van Teijlingen E, Raja EA, et al. Skilled care at birth among rural women in Nepal: practice and challenges. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29(4):371–378. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v29i4.8453

- Simkhada P, van Teijlingen E, Sharma G, et al. User costs and informal payments for care in the largest maternity hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. Health Sci J. 2012;6(2):317–334.

- Simkhada B, Porter MA, van Teijlingen ER. The role of mothers-in-law in antenatal care decision-making in Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-34

- Milne L, van Teijlingen E, Hundley V, et al. Staff perspectives of barriers to women accessing birthing services in Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:142. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0564-6

- Karkee R, Lee AH, Binns CW. Bypassing birth centres for childbirth: an analysis of data from a community-based prospective cohort study in Nepal. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(1):1–7. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt090

- Morrison J, Thapa R, Basnet M, et al. Exploring the first delay: a qualitative study of home deliveries in Makwanpur district Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-89

- Neupane S, Doku D. Utilization of postnatal care among Nepalese women. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(10):1922–1930. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1218-1

- Sharma SK, Sawangdee Y, Sirirassamee B. Access to health: women's status and utilization of maternal health services in Nepal. J Biosoc Sci. 2007;39(5):671–692. doi: 10.1017/S0021932007001952

- Dhakal S, Chapman GN, Simkhada PP, et al. Utilisation of postnatal care among rural women in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-7-19

- Pokhrel BR, Sharma P, Bhatta B, et al. Health seeking behavior during pregnancy and child birth among Muslim women of Biratnagar, Nepal. Nepal Med College J. 2012;14(2):125–128.

- Tuladhar H, Khanal R, Kayastha S, et al. Complications of home delivery: our experience at Nepal Medical College Teaching Hospital. Nepal Med College J. 2009;11(3):164–169.

- Shrestha SK, Banu B, Khanom K, et al. Changing trends on the place of delivery: why do Nepali women give birth at home? Reprod Health. 2012;9:25. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-25

- Acharya J, Kaehler N, Marahatta SB, et al. Hidden costs of hospital based delivery from Two tertiary hospitals in Western Nepal. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157746

- Chaudhary P. Accidental out-of-hospital deliveries: factors influencing delay in arrival to maternity hospital; 2005;3(2):115–122.

- Regmi K, Madison J. Contemporary childbirth practices in Nepal: improving outcomes. Br J Midwifery. 2009;17(6):382–387. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2009.17.6.42608

- Furuta M, Salway S. Women's position within the household as a determinant of maternal health care use in Nepal. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2006;32(1):17–27. doi: 10.1363/3201706

- Thapa DK, Niehof A. Women's autonomy and husbands’ involvement in maternal health care in Nepal. Social Sci Med. 2013;93:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.003

- Dhakal S, van Teijlingen ER, Stephens J, et al. Antenatal care among women in rural Nepal: a community-based study. Online J Rural Nurs Health Care. 2011;11(2):76–87.

- Kc S, Neupane S. Women's autonomy and skilled attendance during pregnancy and delivery in Nepal. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(6):1222–1229. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-1923-2

- Halim N, Bohara AK, Ruan X, et al. Healthy mothers, healthy children: does maternal demand for antenatal care matter for child health in Nepal? Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(3):242–256. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq040

- Brunson J. Confronting maternal mortality, controlling birth in Nepal: the gendered politics of receiving biomedical care at birth. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(10):1719–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.013

- Deo KK, Paudel YR, Khatri RB, et al. Barriers to utilization of antenatal care services in eastern Nepal. Front Public Health. 2015;3:197. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00197

- Upadhyay P, Liabsuetrakul T, Shrestha AB, et al. Influence of family members on utilization of maternal health care services among teen and adult pregnant women in Kathmandu, Nepal: a cross sectional study. Reprod Health. 2014;11:92. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-92

- Onta S, Choulagai B, Shrestha B, et al. Perceptions of users and providers on barriers to utilizing skilled birth care in mid- and far-western Nepal: a qualitative study. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:24580. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.24580

- Choulagai BP, Aryal UR, Shrestha B, et al. Jhaukhel–Duwakot health demographic surveillance site, Nepal: 2012 follow-up survey and use of skilled birth attendants. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:29396. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.29396

- Khanal V, Bhandari R, Adhikari MK, et al. Utilization of maternal and child health services in western rural Nepal: a cross-sectional community-based study. Indian J Public Health. 2014;58(1):27–33. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.128162

- Khanal V, Adhikari M, Karkee R, et al. Factors associated with the utilisation of postnatal care services among the mothers of Nepal: analysis of Nepal demographic and health survey 2011. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-19

- Wagle RR, Sabroe S, Nielsen BB. Socioeconomic and physical distance to the maternity hospital as predictors for place of delivery: an observation study from Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2004;4(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-4-8

- Karkee R, Binns CW, Lee AH. Determinants of facility delivery after implementation of safer mother programme in Nepal: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:193. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-193

- Pandey S, Karki S. Socio-economic and demographic determinants of antenatal care services utilization in central Nepal. Int J MCH AIDS. 2014;2(2):212–219.

- Pradhan PM, Bhattarai S, Paudel IS, et al. Factors contributing to antenatal care and delivery practices in village development committees of Ilam district, Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2013;11(41):60–65.

- Matsumura M, Gubhaju B. Women's status, household structure and the utilization of maternal health services in Nepal: even primary-leve1 education can significantly increase the chances of a woman using maternal health care from a modem health facility. Asia-Pacific Popul J. 2001;16(1):23–44. doi: 10.18356/e8a4c9ed-en

- Thapa N, Chongsuvivatwong V, Geater AF, et al. High-risk childbirth practices in remote Nepal and their determinants. Women Health. 2000;31(4):83–97. doi: 10.1300/J013v31n04_06

- Mullany BC, Becker S, Hindin MJ. The impact of including husbands in antenatal health education services on maternal health practices in urban Nepal: results from a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(2):166–176. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl060

- Sharma SR, Poudyal AK, Devkota BM, et al. Factors associated with place of delivery in rural Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:306. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-306

- Sanjel S, Ghimire RH, Pun K. Antenatal care practices in Tamang community of hilly area in central Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2011;9(34):57–61.

- Shah R. Bypassing birthing centres for child birth: a community-based study in rural Chitwan Nepal. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):597. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1848-x

- Sreeramareddy CT, Joshi HS, Sreekumaran BV, et al. Home delivery and newborn care practices among urban women in western Nepal: a questionnaire survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2006;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-6-27

- Choulagai B, Onta S, Subedi N, et al. Barriers to using skilled birth attendants’ services in mid- and far-western Nepal: a cross-sectional study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:49. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-13-49

- Acharya LB, Cleland J. Maternal and child health services in rural Nepal: does access or quality matter more? Health Policy Plan. 2000;15(2):223–229. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.2.223

- Shah R, Rehfuess EA, Maskey MK, et al. Factors affecting institutional delivery in rural Chitwan district of Nepal: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:27. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0454-y

- Morrison J, Basnet M, Budhathoki B, et al. Disabled womens maternal and newborn health care in rural Nepal: a qualitative study. Midwifery. 2014;30(11):1132–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2014.03.012

- Sharma S, van Teijlingen E, Hundley V, et al. Dirty and 40 days in the wilderness: eliciting childbirth and postnatal cultural practices and beliefs in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):147. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0938-4

- Mesko N, Osrin D, Tamang S, et al. Care for perinatal illness in rural Nepal: a descriptive study with cross-sectional and qualitative components. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2003;3(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-3-3

- Erlandsson K, Sayami JT, Sapkota S. Safety before comfort: a focused enquiry of Nepal skilled birth attendants’ concepts of respectful maternity care. Evidence Based Midwifery. 2014;12(2):59–64.

- Karkee R, Lee AH, Pokharel PK. Womens’ perception of quality of maternity services: a longitudinal survey in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-45

- Kaphle S, Hancock H, Newman LA. Childbirth traditions and cultural perceptions of safety in Nepal: critical spaces to ensure the survival of mothers and newborns in remote mountain villages. Midwifery. 2013;29(10):1173–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.06.002

- Karkee R, Lee AH, Khanal V. Need factors for utilisation of institutional delivery services in Nepal: an analysis from Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2011. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e004372. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004372

- Nonyane BAS, Kc A, Callaghan-Koru JA, et al. Equity improvements in maternal and newborn care indicators: results from the Bardiya district of Nepal. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(4):405–414. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv077

- Morgan A, Jimenez Soto E, Bhandari G, et al. Provider perspectives on the enabling environment required for skilled birth attendance: a qualitative study in western Nepal. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(12):1457–1465. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12390

- McPherson RA, Khadka N, Moore JM, et al. Are birth-preparedness programmes effective? results from a field trial in Siraha district, Nepal. J Health, Popul Nutr. 2006;24(4):479–488.

- Paudel YR, Mehata S, Paudel D, et al. Women's satisfaction of maternity care in Nepal and its correlation with intended future utilization. Int J Reprod Med. 2015;2015:783050. doi: 10.1155/2015/783050

- Ensor T, Bhatt H, Tiwari S. Incentivizing universal safe delivery in Nepal: 10 years of experience. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(8):1185–1192. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx070

- Traeger B. Poverty and fertility in India: some factors contributing to a positive correlation. Global Majority E-Journal. 2011;2:87.

- Walby S, Armstrong J, Strid S. Intersectionality: multiple inequalities in social theory. Sociology. 2012;46(2):224–240. doi: 10.1177/0038038511416164

- Sharma S, Teijlingen E, Belizan JM, et al. Measuring what works: an impact evaluation of women's groups on maternal health uptake in rural Nepal. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155144

- Nguhiu PK, Barasa EW, Chuma J. Determining the effective coverage of maternal and child health services in Kenya, using demographic and health survey data sets: tracking progress towards universal health coverage. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22(4):442–453. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12841