ABSTRACT

Social enterprises are organisations that employ commercial strategies to deliver societal impact, rather than shareholder value, and may play an important role in the transition to a more socially sustainable society. However, social entrepreneurship has become a contested terrain due to its ambiguous identity and ideology. This study maintains that accounting plays a role in the development of social enterprises due to its ability to shape the domain of economic operation. Using interview data obtained from the key actors in Finland, this study identifies and analyses perceptions of the roles of accounting for social enterprises. Overall, the study highlights the ambiguities related to accounting for social enterprises and draws attention to the plural roles of accounting. It encourages opening up the processes of defining the principles and tools for accounting for social enterprises, arguing that such decisions may have broader organisational and societal implications.

Introduction

Social enterprises (SEs) may play an important role in the transition to a more socially sustainable society. Indeed, there are great expectations regarding their mission of delivering social welfare and solving social problems with innovative solutions (Teasdale, Lyon, and Baldock Citation2013). Social enterprises are organisations that employ commercial strategies to deliver societal impact, rather than shareholder value, and they are currently being promoted in all over the world and experiencing increasing popularity (Dey, Schneider, and Maier Citation2016; Hulgård Citation2010). However, there are also many unanswered questions related to this organisational model, from the varying understandings of what a SE is in a first place (Defourny and Nyssens Citation2017; Dey, Schneider, and Maier Citation2016; Mason Citation2012) to the discussion of the variety of supporting measures and structures, such as accounting, needed to advance these organisations and help them balance between social and financial goals. Concerns have also been raised regarding the managerialisation of SEs as part of the increasing financialisation of social and environmental activities (Amslem and Gendron Citation2019; Chiapello Citation2015; Dey and Teasdale Citation2016).

Much of the research that analyses SEs acknowledges the fact that the concept is understood differently by different people (Dey and Teasdale Citation2013; Mason Citation2012). Social entrepreneurship and social enterprisesFootnote1 also take different legal forms in different countries. However, the consequences of such differences in practices and understandings are rarely discussed (Day and Steyaert Citation2010). The paper at hand argues that these different understandings of SEs also differ in their constructions of ‘the social entrepreneurial paradigm’ (Nicholls Citation2010) and may lead to different material and structural implications. Importantly, it is maintained that accounting plays a role in this development due to its ability to shape the domain of economic operation as well as social relations (Chenhall, Hall, and Smith Citation2013; Miller and Power Citation2013).

Social enterprises currently face global pressure to start measuring their societal impacts, and one of the key issues in the institutionalisation of the field is how to account for and report the social impact of SEs (Ebrahim Citation2003; Ebrahim and Rangan Citation2014; Hall and O'Dwyer Citation2017). Despite the growing popularity of studies on SEs, there is a need of research focusing on accounting within this field (Gibbon Citation2012; Hall and O’Dwyer Citation2017; Mäkelä, Gibbon, and Costa Citation2017). Because the purpose of SEs is to create social impact rather than economic value for shareholders, conventional accounting measures are often not suitable for SEs. Caution has also been expressed about adopting the most common social accounting tools, such as the Social Return on Investment (SROI) and Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) without proper consideration of their fit to SEs (Brown and Dillard Citation2014; Green Citation2019; Vik Citation2017). This study argues for a more nuanced understanding of accounting ideas, systems, and processes and how they may enable and support the dual goals of SEs. An analysis focusing on the various roles of accounting for SEs highlights the multiplicity and ambiguities related to accounting and its’ implications. Furthermore, the study joins critical research on SEs (Dey and Teasdale Citation2016; Dey, Schneider, and Maier Citation2016; Mason Citation2012) and points to the complexity of SEs and how accounting may or may not support particular understandings and development of this organisational field. Using interview data with the key actors in the field, this study analyses perceptions of the roles of accounting in shaping the contested terrain of SEs. It aims at highlighting the ambiguities related to accounting for social enterprises and draws attention to the plural roles of accounting. It encourages opening up the processes of defining the principles and tools for accounting for social enterprises, arguing that such decisions may have broader organisational and societal implications.

The study at hand focuses on SEs in the context of a Northern-European country, Finland, where SEs are still in a pre-paradigmatic state. Using interview data with the key actors, those seen as influential in defining and developing SEs and the broader field of social entrepreneurship (Dey, Schneider, and Maier Citation2016; Nicholls Citation2010), the study analyses perceptions of the roles of accounting for SEs. The paper proceeds by introducing the concept and varying definitions of social enterprise, highlighting the different understandings and ideologies of SEs. This is then followed by a discussion of the role of accounting as a social and organisational practice, describing how accounting may impact the development of the field of SEs and emphasising the importance of understanding the multiple roles and functionings of accounting. Prior work in the area of accounting for SEs is also summarised. The next section presents the findings of the empirical material, i.e. identifies and analyses the perceptions of the roles for accounting for SEs in Finland. A concluding section discusses the broader significance of the findings.

Definition(s) of social enterprises

As is often the case with any emerging concept, the concept of a social enterprise has various meanings (Dart Citation2004; Dey and Teasdale Citation2013; Dey, Schneider, and Maier Citation2016; Mason Citation2012). Conceptual confusion occurs because the ‘social enterprise is a fluid and contested concept constructed by different actors promoting different discourses connected to different organisational forms and drawing upon different academic theories’ (Teasdale Citation2012, 1). Some of the definitions of SEs highlight the entrepreneurial nature of these organisations and the role of the ‘hero entrepreneur’, while others point to their critical links to social economy, underlining the role of the community and networks of action (Barrakett Citation2013; Dey and Teasdale Citation2013; Dey, Schneider, and Maier Citation2016; Nicholls Citation2009; Ridley-Duff Citation2007). Generally speaking, the varying understandings of SEs all rely on certain key concepts, such as economic activity, social value and impact, community development, democracy, and even innovation, but these understandings very much differ in their prioritisation of these diverse aspects. There are also differences in understanding SEs depending on geographic location and cultural boundaries (Kerlin Citation2010; Mason Citation2012). Specifically, US-based approaches tend to emphasise the role of market-oriented action (Defourny and Nyssens Citation2010), innovation and the social entrepreneur, whereas in Italy, for example, the history of SEs is often linked to social cooperatives taking charge of social services. Obviously, the context influences the adoption, development, and institutionalisation of social entrepreneurship because the existing social structures, politics and institutions have power over the development of this field (Kerlin Citation2010).

In Europe, where this study is located, the concept of the social enterprise first appeared in Italy in the early 1990s (Defourny and Nyssens Citation2012). Since then, legal forms of SEs have been introduced at least in Spain, Greece, France, Belgium, and the UK. The European Commission promotes SEs (EC Citation2011) and social economy in general in an attempt to create social innovation. There is some confusion, however, because SEs in different countries take different legal forms and are associated with different conceptions and identities. The most commonly cited ‘official criteria’ for SEs in Europe, which the European Commission also echoes, is that of the EMES European Research Network, which defines three sets of criteria for SEs: the economic and entrepreneurial dimensions emphasising, for instance, a significant level of economic risk; the social dimensions emphasising the explicit aim of benefiting the community and the dimension of participatory governance of an SE, emphasising the democratic and participatory nature of the organisation. However, it has been claimed that the institutional field of SEs is still in a pre-paradigmatic state (Nicholls Citation2010; Roy et al. Citation2018).

One paradox reported by Hulgård (Citation2010, 8) is that SEs can be seen as two sides of the same coin: ‘not only as elements in a process of privatisation but also as a manifestation of the power of civil society – trend towards the emergence of new forms of solidarity and collectivism’. Often, they are introduced as ‘a third way’ that falls somewhere between ‘the triumph of capitalism’ (Gilbert Citation2002) ‘and the “old” institutional-redistributive model of welfare, with state dominance’ (Hulgård Citation2010, 15). These different definitions view the nature and purpose of the institutional field of SEs in different ways and also shape the broader knowledge structures and how we come to think and act in terms of SEs. They also affect how the field is then promoted, resourced, and regulated.

Social entrepreneurship has obviously become a debated terrain due to ambiguities over its identity, ideology and ‘fuzzy conceptual boundaries’ (Mason Citation2012, 124). Social enterprises, as part of third sector organising, may be seen as an arena for wider ideological and political struggles. It is claimed that the SE concept has ‘tactical polyvalence’ (Teasdale Citation2012), allowing it to be flexibly aligned with new ideas and political agendas and to be adopted in diverse areas such as culture, health and social care (Baines, Bull, and Woolrych Citation2010). A growing critique has emerged among researchers and grassroots actors regarding the managerialist and functionalist understandings of SEs, echoing the assumption that ‘even the most benevolent initiatives of social change can become “dangerous” as soon as they use particular “truths” to mobilize subjects and institutions’ (Day and Steyaert Citation2010, 100). Concerns have been expressed that the field has been captured by the neoliberal political agenda, which promotes financialisation, (alleged) economic rationality and entrepreneurial and business-like values and practices (Amslem and Gendron Citation2019; Chiapello Citation2015; Dey and Teasdale Citation2013, Citation2016; Nicholls and Teasdale Citation2017) and renders the third sector as a governable terrain (Carmel and Harlock Citation2008; Eikenberry Citation2009; Eikenberry and Kluver Citation2004). Social enterprises are sometimes presented as a materialisation of the broader societal shift toward market dogmatism (Amslem and Gendron Citation2019; Chiapello Citation2017; Grant and Humphries Citation2006).

The small but growing critical body of work on SEs has emphasised that the supposedly ‘necessary’ and ‘inevitable’ marketisation of the third sector, including SEs, is not a value-neutral and rational act but a political and ideological intervention (Dey and Teasdale Citation2013; Eikenberry Citation2009; Grant and Humphries Citation2006; Teasdale and Dey Citation2019). The ‘seemingly unproblematic combination of market-based approaches and the pursuit of social goals’ (Dey and Teasdale Citation2013, 250) has been questioned, and there are calls for revisiting the discourse of SEs (Dart Citation2004; Dey and Teasdale Citation2013; Grant and Humphries Citation2006; Mason Citation2012). For instance, the managerialist, entrepreneurial and market-based understandings are promoted through the marginalisation of ‘practices and values that foster participation, solidarity, civic deliberation, and trust’ (Eikenberry Citation2009, as quoted by Dey and Teasdale Citation2013, 251). Dart (Citation2004) claims that the taken-for-granted rationalist understandings and narrow economic reasoning for the existence of SEs downplays the complex cultural and political context and origins of the field. However, and importantly, Dey and Teasdale (Citation2013, 250) argue that these managerialist accounts of SEs may oversimplify their reality because firstly, the degree to which third sector organisations are rational economic actors may be overestimated and, secondly, the dilemmas and ambivalences of their everyday activities may be concealed. The study at hand joins the limited number of critical scholars interested in SEs, shedding light on the multiple and varying conceptualisations of SEs and their relationship with accounting (Dey, Schneider, and Maier Citation2016; Mason Citation2012).

Accounting for social enterprises

Despite the growing popularity of SEs and social entrepreneurship, no comprehensive understanding exists regarding the impact [positive or negative] of this field on society – despite its almost myth-like features of delivering social welfare and solving social problems (Maas and Grieco Citation2017). A ‘striking lack’ of accounting and reporting research and practices for SEs has been noticed (André, Cho, and Laine Citation2018; Hall and O’Dwyer Citation2017; Nicholls Citation2009; Vik Citation2017). Social accounting research, which is generally interested in how to best account for and report on corporate societal performance and impact, tends to focus its attention on large multinational companies at the expense of marginalising knowledge on alternative types of economic organisation (Hall and O’Dwyer Citation2017; Mäkelä, Gibbon, and Costa Citation2017). Conventional accounting, as practiced by multinational corporations following international accounting standards, is also claimed to support the business case for sustainable development, consistent with corporate agendas of shareholder wealth maximisation (Larrinaga-Gonzalez and Bebbington Citation2001; O’Dwyer Citation2003). Because their primary purpose is to create social impact rather than economic value for shareholders, conventional accounting measures are often not suitable for SEs (Costa, Parker, and Andreaus Citation2014; Gibbon Citation2010; Gibbon and Dey Citation2011; Luke Citation2016; Citation2017; Martinez and Cooper Citation2017; Vik Citation2017). A broad field of research focusing on accounting for NGOs (see e.g. Agyemang, O’Dwyer, and Unerman Citation2019; Hall and O’Dwyer Citation2017; Unerman and O’Dwyer Citation2006) may offer promising insights for SEs regarding the role of accounting supporting values-based organisations. However, in a similar manner that traditional for-profit companies are different from SEs, NGOs usually differ from SEs for their financial base and not-for-profit strategies. In other words, both types of organisations usually serve one primary goal. While the roles of accounting are likely to vary in these organisations too, the linkage between accounting and organisational strategy is here still argued to be more straightforward than for SEs that balance between the social and financial purposes.Footnote2 SEs differ from private companies and NGOs because the two types of organisational goals are intrinsically connected, rather than seen as two ends of a continuum. Accounting for SEs requires a complex, dynamic, multi-directional and multi-stakeholder accounting system (Costa, Parker, and Andreaus Citation2014). There is a risk in adopting traditional, taken-for-granted assumptions and measures of accounting without considering their broader implications for SEs and social entrepreneurship more broadly.

Several studies criticise the employment of traditional understandings of accounting within SEs and point to the importance of analysing multiple and alternative understandings. Prior research (Gibbon and Affleck Citation2008; Johnson and Schaltegger Citation2016; Kay and McMullan Citation2017) reports on the barriers and resistance to social and environmental accounting, mainly lack of time, awareness, expertise and financial resources. Gibbon (Citation2010) argues that social accounts may actually be used to support the individualistic or hierarchical models of accountability rather than informal and broader socialising models of accountability, quite contrary to what might be expected from values-based organisations with a strong mission of social justice. Gibbon and Dey (Citation2011, 63) argue that the use of the relatively widespread social return on investment (SROI) method may promote ‘a one-dimensional funder- and investor-driven approach to social impact measurement in the third sector’. Likewise, Vik (Citation2017) critiques SROI for its limitedness in measuring the ‘true impact’ of SEs and echoes Luke, Barraket, and Eversole (Citation2013) in claiming that it is mainly used for organisational legitimation. Also, more practically oriented experiments are being reported about emergent accounting and reporting practices by, for instance, Green (Citation2019), Luke (Citation2016), Mook, Richmond, and Quarter (Citation2003) and Nicholls (Citation2009), with similar concerns about the risk of reducing social impacts to a list of financial debits or credits. It is also claimed that in the broader field of third sector organising, accountability requirements may disable rather than enable social values and thus hinder organisations in achieving societal impact (Martinez and Cooper Citation2017).

Different approaches to accounting and accountability have been offered by, for instance, Brown and Wong (Citation2012), Dillard and Pullman (Citation2017), Gibbon and Angier (Citation2011), Kleinhans, Bailey, and Lindbergh (Citation2019) and Oakes and Young (Citation2008), emphasising processual, discursive and socialising forms of accountability. These studies argue that accounting and accountability should be based on an ongoing process that incorporates the shared activity of establishing the goals to be met, as well as serious attention to the question of who to include in this activity and how social accounts enable the development of accountability relationships over time. Despite some interesting research initiatives, there is a lack of in-depth studies and understanding of accounting in the context of SEs (Aung et al. Citation2017; Bengo et al. Citation2016; Hall and O’Dwyer Citation2017). In sum, the prior work highlights the need for a more nuanced understandings regarding accounting for SEs.

Accounting as a social and organisational practice

In this study, accounting is understood in its broadest notion, as defined by Miller and Power (Citation2013), as ‘a complex’, as a group of diverse elements, comprised not only of accounting and measurement tools but also of ideas, goals, reports, standards, laws and the human actors operating in this broad and fluid field of accounting. Accounting includes all the historically varying calculative practices that allow us ‘to describe and act on entities, processes and persons’ (Chapman, Cooper, and Miller Citation2009, 1).

It is well-recognised that ‘accounting cannot be conceived as purely an organizational phenomenon’ (Burchell et al. Citation1980, 19). Here, accounting is seen as a social and organisational practice (see, e.g. Hines Citation1988; Hopwood Citation1987; Miller and O’Leary Citation1987), and discussions and decisions about whether and what types of accounting systems will be implemented have broader implications. Accounting influences organisations and the organising of societies by creating visibility and significance (Hopwood Citation1987) because it is in these discussions about the accountability relationships, types of accounts and their operation that the worth of things is debated (Chenhall, Hall, and Smith Citation2013, 283). Through measuring organisational success, accounting provides ‘authoritative signals’ regarding the very purpose of an organisation (Chenhall, Hall and Smith Citation2013, 270). Business planning, for instance, is not ‘a neutral mechanism of transcription’ but has a significant influence on the ‘forms and amounts of capital within a field and for organizational identities’ (Oakes, Townley, and Cooper Citation1998, 258). Through highlighting certain aspects of reality and simultaneously silencing others, accounting has the power to influence our knowledge structures and the ways we come to think and act regarding SEs (Burchell et al. Citation1980; Hines Citation1988). Accounting influences knowledge constructions also in fields outside its direct influence because it is involved in shaping organisational objectives and accountability relationships, and in the constructions and compromises or what is seen as desirable organisational behaviour (Amslem and Gendron Citation2019; Modell Citation2019).

Furthermore, numerical accounts as such are claimed to have universal appeal because they convey authority and credibility (Porter Citation1995; Power Citation2004). Due to increasing financialisation, numerical accounts and other financial figures have become dominant organising devices. Through numerical accounts, we can align different viewpoints and share allegedly common criteria and metrics, even across disciplinary boundaries (Arjaliès and Bansal Citation2018; Chiapello Citation2017; Porter Citation1995). Accounting numbers can also be actively and purposively used as framing devices to influence decision making (Goretzki et al. Citation2018). For these reasons, debates and decisions about particular accounts are critical to organisational and institutional development.

Accounts are increasingly being demanded from different types of organisations (see, e.g. Amslem and Gendron Citation2019; Martinez and Cooper Citation2017), not only private companies but also of public sector entities, NGOs as well as SEs. The study argues for the importance of in-depth analyses of accounting for SEs, and sheds light on the multitude of ways in which the ‘accounting complex’ may be perceived, as well as what sorts of purposes, properties and roles may be attached to it. The study highlights the complexity of SEs and how accounting may or may not support and advance particular understandings of this organisational identity and relationships. Furthermore, it is likely to affect our understanding of what kind of tangible support is needed for SEs to flourish. In other words, the study focuses on the interconnectedness of accounting and the institutionalisation of SEs and argues that the understandings, development and adoption of accounting ideas and systems has a wider impact on the emergence of SEs and social entrepreneurship. Considering the pre-paradigmatic state of SEs, the adoption of accounting ideas and tools may be critical in the development of the field.

Empirical analysis

The context: social enterprises in Finland

The present study focuses on the specific context of SEs in Finland. In Finland, interest in SEs has only recently begun to grow (Ministry of Employment and the Economy Citation2011, Citation2020; Sitra Citation2012). The Finnish Social Enterprise MarkFootnote3 (Citation2014) defines the criteria for being identified and labelled as a social enterprise. The principles include having a social or ecological purpose, profit distribution constraints, transparency, and ownership in Finland. The ‘secondary criteria’ involve employee engagement and the measurement of social impact. Estimates vary, but there are some 1700 to even 15,000 SEs in Finland, depending on the criteria used (see also Teasdale, Lyon, and Baldock Citation2013). Many different types of organisations fall under the rubric of SE: seemingly ‘traditional’ private companies, but also those that aim to foster democratic governance and alternative understandings of economic organisation. SEs in Finland operate in all areas of society, but mostly within health and social services. Also, in the arts and culture arenas, SEs have flourished. There is no legal form or special legislation for SEs in FinlandFootnote4 or any structural support being provided, such as special financing modes or state subsidies. The organisations may take various legal forms but often operate as limited companies, cooperatives or even associations. SEs and social entrepreneurship are seen to be in a pre-paradigmatic state in Finland, allowing an insightful analysis of the varying understandings of SEs, accounting for SEs and their interconnectedness.

Accounting and measurement ideas and tools have only recently been introduced to the field, for instance, by Sitra.Footnote5 These ideas and suggestions range from the extensive reporting frameworks, such as the GRI and Integrated Reporting (IR) to the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) and SROI. Many discussions seem to centre around these well-known and most commonly used global frameworks. However, none of these have thus far been adopted by the SEs for use on a regular basis. Given the global growth of SEs and the rather underdeveloped level of institutionalisation in this field in Finland, SEs are experiencing a very interesting time. As claimed by Defourny and Nyssens (Citation2010, 49), ‘unless embedded in local contexts, social enterprises will just be replications of formula that will last only as long as they are fashionable’. The decisions to be made regarding the institutional role of and potential supporting structures, such as accounting, for SEs in Finland will be vital in defining their future development.

Empirical material and method

To gain insights into accounting for SEs, interviews were conducted with key actors in the field of SEs in Finland. Before data collection, the key actors had to be identified. The key actors, or intermediary or field-building actors, are those who are seen as influential in defining the meaning and developing the field of SEs (Dey, Schneider, and Maier Citation2016; Mason Citation2012; Nicholls Citation2010). The role of the political actors and also, more broadly, the intermediary organisations is key in the development and institutionalisation of SEs (Dey, Schneider, and Maier Citation2016; Mason Citation2012). These actors control the institutional resources, including but not limited to financial support, which are required to foster SEs. They also hold other resources, such as authority, experience, and networks, in defining the directions that SEs take in Finland. Here, the key actors were considered to be people who had been involved in the development of SEs and social entrepreneurship in Finland during the previous years or had been ‘actively engaged with paradigm building’ (Nicholls Citation2010, 617). The initial intention was to interview several key actors from a wide variety of positions and backgrounds. However, because social entrepreneurship is an emerging field in the small country of Finland, only a small number of people and institutions have been actively engaged in promoting and developing the field. Initially, I contacted several people who had been involved in the formal working groups and other organising bodies established around social enterprises in Finland, such as the working group for developing social enterprises in Finland, organised by the Ministry of Employment and the Economy in the early 2010s, and the people who at the time of the interviews were involved in the organisations whose aim was to promote and develop social entrepreneurship in Finland. In addition, I contacted people who were actively involved in the more informal work for social enterprise development, mainly active members of a group that gathered individuals interested in social entrepreneurship, including researchers, activists and consultants with their own SE-related businesses. A snowball technique was also used among the interviewees to identify relevant actors. Altogether, nine interviews were conducted from 2014 to 2015. The interviewees can be classified as representatives of the Government (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and Ministry of Employment and the Economy), fellowship and network organisations, consultancy firms and ‘individual activists’. Due to the very limited number of individuals engaged with paradigm-building in the small country of Finland, ensuring anonymity of the interviewees did not allow for a more specific identification of the informants.

All primary data were collected through these nine semi-structured interviews, which ranged in length from 50 to 90 min.Footnote6 A loose interview guide was used to systemise the interview situations. However, the participants were encouraged to speak freely and openly about anything that they considered relevant respecting their expertise, prior experiences and their own insights and interpretations. The interviews were later transcribed by a professional service. The quotations from the interviews were translated by the author and later proofed for English language by a professional service.

The analysis process was iterative and reflexive, and the transcribed interviews were read through several times and analysed through a close-reading of the interview data. During the first reading, memos were written on the initial descriptive narratives, which were then used as a basis for the following iterative process of reading, writing and analysis between data and theory. The data were coded according to the key themes identified in the first rounds of reading. These themes were then used as a basis for a more detailed, in-depth analysis of the data. The analysis was on the level of shedding light on the multiplicity of understandings of the role of accounting, and not much attention was given on ‘who said what’, also again ensuring the anonymity of the individual informants. Finally, the interpretations were re-evaluated and elaborated by going back and forth between the data and theory. The data collection, analysis and reporting were conducted by the sole author. While such interpretive analysis is never free from subjectivity but always and essentially based on the subjective reading of the researcher, the memos and quotations from the data ensure the reliability of the interpretation and analysis.

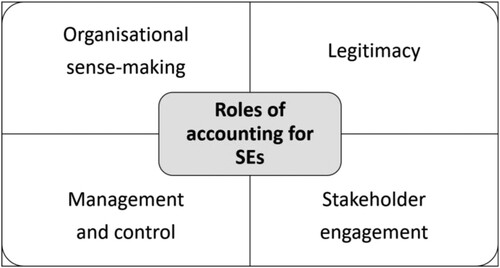

Findings of the empirical analysis: roles of accounting for SEs

The following section reports the findings from the empirical analysis, that set out to identify and analyse the varying perceptions on the roles of accounting for SEs. All in all, the most common themes in the interviews were indeed related to the multiple and varying roles for accounting systems and practices in SEs. While the analysis was not on the level of individual informants and their personal motivations to express particular opinions, the varying backgrounds and positions of the interviewees were fruitful in bringing out the diversity of perceptions regarding the roles of accounting. This is also seen to highlight the pre-paradigmatic state of SEs in Finland, where dominant understandings are perhaps not yet strongly embedded. Furthermore, it also sheds light on the politics inherent in the development of the field.

The semi-structured interviews allowed for the discussion to freely develop according to the interests, opinions, and experiences of each of the interviewees. The definitions regarding accounting were initially kept broad and unspecified by the interviewer, to allow multiple understandings to emerge and to be covered. The themes, or words, most often used were ‘reporting’ and ‘measurement’. These often led the discussions to the other roles of accounting, and it was left to the interviewees themselves to lead the discussion in their preferred directions. Usually, they did not specify any particular aspect of accounting or any particular means of or tools of account giving. The interviewees most commonly referred to accounting as a very general idea of ‘measuring performance’ or ‘measuring impact’, which seemed to cover several aspects of accounting. This also reflects the fact that there are no such systems in place in Finnish SEs and perhaps that most of the interviewees were not accounting experts. Most of the interviewees pointed to the fact that any performance measurement system or accounting beyond the minimal financial accountability of providing financial statements was fully based on voluntary actions and basically non-existent.

It is barely done yet. We don’t really have proper measures. I4

Ensuring legitimacy of the institutional field of social enterprises

All in all, the need for accounting was seen as self-evident. None of the interviewees denied the importance of or need for accounting and measurement tools and practices, although some did mention that measurement for measurement’s sake did not make sense. Overall, it was clear that all were in favour of accounting for the social impact of SEs. In fact, measurement was seen as a must. Less discussed were the reasons for accounting and measurement and their practical purposes and implications. It appears that accounting and measurement as such were seen as important, hinting that they are necessary in order to ‘show impact’, that is, to show that the emerging field of SEs is a legitimate one. As in previous research (Luke, Barraket, and Eversole Citation2013), the key actors in Finland also spoke of a need to justify the existence of this new, evolving field that is still facing doubts from various groups in society, such as ‘traditional’ entrepreneurs, financial investors and the government.

Yes it should be measured, and above all, there should always be external reporting. As much as we can, we should raise these issues, and with understandable measures, so that even the general public understands that this is why this social enterprise exists and this is why it succeeds. I1

Evaluating social impact with transparent reporting is […] important, and there are certain supporting mechanisms, identifying the funding models, how to fund these operations. After all, this funding is extremely important. I6

Of course reporting and transparency are important, but I don’t know if it is such an important foundation anyway. […] I am quite critical towards it, what it can solve after all. I8

So it [reporting/measurement] should, primarily, give answers to serve the development of operations. It should not make some “general public” believe something. I3

Similar tendency is being reported in the non-profit sector more broadly as well (Fry Citation1995; Goddard and Assad Citation2006), with increasing faith in ‘outcome measurement as the compass by which non-profit agencies should guide themselves regardless of how they are configured’ (Light Citation2010, 2, as quoted in Grimes Citation2010). Because SE as a business model is not striving for the largest possible financial gains, it may face doubts regarding its ability to run successful business. Therefore, SEs may need to show that they can run their operations profitably and efficiently. Prior research has also identified that SEs with strong performance measurement practises can more easily legitimise themselves is the eyes of venture capitalists (Mair and Marti Citation2006). Similar findings have been reported regarding the more specific accounting tools for SEs, such as SROI, with claims that SROI is viewed as a tool for symbolic legitimacy rather than providing credible and elucidating the ‘true’ value of social impact (Luke, Barraket, and Eversole Citation2013; Vik Citation2017). Ensuring legitimacy for SEs may be important for various reasons, also for their role in providing societal impact. All in all, the role of accounting in constructing a particular view of SE, making them and their performance and wider impact visible was considered vital.

Organisational sense-making

Previous research claims that performance measures are used as examples of shared meanings and are linked to shared values among organisational actors as they make visible the intended future directions of the organisation (André, Cho, and Laine Citation2018; Grimes Citation2010; Henri Citation2006; Townley, Cooper, and Oakes Citation2003). Grimes (Citation2010) sees performance measurement as an outcome of sense-making activities rather than as a tool for influencing performance expectations. Performance metrics may help the organisations to make sense of their own social performance and the related aspirations (André, Cho, and Laine Citation2018). Also, among the Finnish key actors, accounting and performance measurement were seen as enabling the organisations to elaborate on their shared values and future directions. By developing vision and strategy and setting targets, the organisations engage in sense-making processes to determine what they are all about, their priorities and what they strive for.

So that we would start thinking about why we exist, what we want to achieve, what the impacts are and for whom should they be created. I7

One of the central benefits … is that the companies identify as alike and somehow build the understanding that it kind of strengthens their identities in relation to other similar actors … so it is clearly a tool for building internal identity, at the moment, more than anything else. I3

We started the wrong way. … there’s a large group there that are SEs. They don’t know that they are SEs. They haven’t thought about it from this perspective, even if they operate just like these principles [of SEs]. So, they should first have done the job [of defining who they are] and then created the label. I7

Managing and controlling performance

Unsurprisingly, accounting is also seen as a tool for managing and controlling organisational performance. As organisations establish goals and metrics, they simultaneously set the level of performance to which they wish to aspire (Kaplan and Norton Citation1992). In other words, organisations become what they measure. With clear targets and measures, organisational control is more informed and more efficient. Many of the interviewees expressed their wish for SEs to be managed through accounting-related targets and measures and some sort of performance measurement systems. Within this perspective, the justification for accounting is a more reasonable, better planned and more rational social order.

Yes, I think every organisation should think about their own measures. It doesn’t have to be much, but something to start with […], and start reporting […] so that there is the clarity, transparency. I8

It should primarily serve so that the organisation itself can improve its performance. So it should give answers regarding the development of operations, primarily. I3

[…] and how we bring it to the management control system, as a natural part. […] It is not just that we abide by the norms and report about that but that we perform better. […] Of course, we need to measure exactly because we need to evaluate our performance. “Have we met the targets? Have we done the right thing?” I4

I guess it is needed. You must have measures and indicators for quality. […] I think it is one of the central issues, that social enterprises can show that this is the impact, and this is the price. I3

Efficient performance measurement and management are undeniably, or at least to some extent, essential in any organisation, and they become particularly important in organisations with scarce resources, as is usually the case in SEs. However, because accounting and performance measurement set targets and shape organisational directions, they risk an instrumental and managerialist rationalisation of organisational performance (Townley, Cooper, and Oakes Citation2003). The development of a specialised organisational language (that of performance measurement) is an important element of this instrumental rationalisation (Hopwood Citation1987). Expert vocabularies of accounting, including strategies, budgets, and performance measures, articulate and construct new organisational visibilities and goals (Hopwood Citation1987; Miller and Power Citation2013). However, it is debated whether accounting and performance measurement necessarily bring about this instrumental rationality and control (Ahrens and Chapman Citation2004; Townley, Cooper, and Oakes Citation2003; Wouters and Wilderom Citation2011).

Stakeholder engagement

Some interviewees clearly emphasised the ‘social’ nature of SEs and discussed the abilities of accounting systems to support the principles of democratic governance and multi-stakeholder engagement. However, this is an area in which the interviewees’ perceptions differed the most: some of the views were clearly focused on stakeholder engagement and democratic governance, whereas others focused on the business side of operations and creating social impact, stating that democratic governance and other similar principles regarding how to run the business processes did not seem important.

Because reporting means building trustful relationships with any stakeholder, it requires a certain amount of transparency […] it does not happen through a yearly document but through a one-to-one discussion. It is reporting too, such a discussion. It’s just that the format is quite different. I6

The reporting is, kind of, needed. But it’s not the thing, but the whole process is. How the results are finally produced, that’s the more important thing. […] We have that dialogue, and that’s how I think the real transparency is created. I7

[…] a very tight and a real interconnected relationship with the target group, so that this group can influence how the company operates, how it pursues its target, what kind of performance it is trying to achieve. This, I guess, is the key. I9

Well, that’s quite a new perspective for me. I haven’t thought about it, because I always thought that the one who acts is responsible for producing the information, so it’s kind of the social enterprise that is responsible for producing the information. I4

If it takes a massive amount of time, in the name of democracy, to report about these things, then is it good business or is it … I8

The interviewees who emphasised the importance of stakeholder engagement were worried that formal accounting systems with an explicit focus on figures and indicators might set aside social principles and purposes. Also, previous research reports that ‘techniques of calculation and the specialized knowledges inherent in planning and measurement systems can suppress moves to socially justified and coordinated action’ (Townley, Cooper, and Oakes Citation2003, 1056; see also Martinez and Cooper Citation2017). This kind of instrumental rationalisation poses a risk of de-personalising social relationships and extending technically rational control over social processes (Brubaker Citation1984, as quoted in Townley, Cooper, and Oakes Citation2003, 1056).

However, accounting may also be seen as a positive force in facilitating stakeholder engagement (Roberts Citation2001; Wouters and Wilderom Citation2011). Engaging stakeholders in the accountability processes creates more socialising forms of accountability, which are not so much focused on the final report and formal accounts but on the entire process of accountability and the role of stakeholders and stakeholder relationships (Kleinhans, Bailey, and Lindbergh Citation2019; Roberts Citation2001). Respecting stakeholders is seen valuable in itself and as part of the democratic and participatory governance mechanisms of SEs. Furthermore, stakeholders that are committed to and engaged with the organisation are seen as an important organisational resource and are also expected to maintain their relationship with the organisation longer. Given a close relationship with inside and outside stakeholders, whether they are employees or customers, information and other resources flow more easily, and trust is created. However, prior research has noticed that stakeholder engagement does not necessarily support ‘real’ democratic governance or socialising forms of accountability, but may serve as symbolic and instrumental tool for legitimising ‘business as usual’ (Brown and Dillard Citation2015; Mitchell, Agle, and Wood Citation1997; Puroila and Mäkelä Citation2019).

In sum, the empirical analysis aimed at shedding light on the varying roles that accounting is perceived to serve in SEs. While all the interviews shared the opinion that accounting is important, and accounting for SEs is a must, the perceptions on the roles of accounting varied significantly. Very few of the interviewees were able to explicitly define what they mean by accounting but varying implicit understandings of the roles of accounting were identified from the empirical material. This could be taken to highlight that if not properly scrutinised, the taken-for-granted perceptions of accounting may lead us to adopt and implement accounting tools that are not the best fit for its environment. Furthermore, there is a risk of neglecting the broader organisational and societal implications of accounting for the field of SEs.

Conclusions and discussion

Using interview data with the key actors in the field of SEs in Finland, this study analysed perceptions of the roles of accounting in the context of shaping the contested terrain of SEs. It aimed at drawing attention to the ambiguities and the plural roles of accounting in the context of SEs.

This study found four different perceptions of and roles for accounting in SEs. Firstly, accounting is expected to legitimise the organisation for external and internal stakeholders by representing that organisation’s capacity to deliver expected performance. Accounting has universal appeal as a rational and trustworthy system of organising. By creating particular visibility, setting particular ‘frames’ for organisational performance and hence bringing a sort of desired closure to the organisational image, accounting may create legitimacy regarding organisational performance. This applies to both social and financial expectations. In particular, having formal accounting systems in place will seem professional and make SEs appear as ‘serious business organisations’. Secondly, as accounting and measurement are linked with organisational planning and target-setting, implementing an accounting system may encourage sense-making and elaborations of the purpose and identity of the organisation. By defining the future goals, as well as the steps that must be taken to pursue and measure them, accounting highlights organisational identity, goals, and priorities. It also articulates targets and priorities across organisations through strategic work and resource allocation. Thirdly, through accounting systems, financial management and control practices are introduced to organisations, with the purpose of providing information to the management of the organisation to help better plan and control organisational performance. Finally, accounting may also increase stakeholder engagement and strengthen the stakeholder relationships through socialising forms of accounting and accountability, encouraging stakeholders to be included in the processes of organisational sense-making, goal setting, performance measurement, accounting and reporting.

Giving an account is central to all organisational relationships. These identified roles of accounting in SEs may overlap, but they may also highlight and serve very different functions and purposes in organisations. SEs as organisations are seen to pursue multiple goals from societal impact to efficient financial performance, embedded in different ideologies that vary significantly in their orientation and usually fall somewhere in the line between innovative market-based solutions and sustainable social economy (Amslem and Gendron Citation2019; Barrakett Citation2013; Day and Steyaert Citation2010; Mason Citation2012). As accounting in acknowledged to impact our understandings of organisational performance (Hines Citation1988; Hopwood Citation1987; Miller and Power Citation2013), the question is what, if any, of the purposes and ideologies of SEs will be promoted when adopting a particular accounting measure for SEs. Prior research has drawn attention to how particular accounting tools may serve particular understandings of SEs, drawing attention to the risk of disabling rather than enabling the social values (Gibbon and Dey Citation2011; Vik Citation2017). Then again, accounting may serve to strengthen organisational purpose (Chenhall, Hall, and Smith Citation2013) and to enable stakeholder engagement and social values through socialising forms of giving an account (Kleinhans, Bailey, and Lindbergh Citation2019; Oakes and Young Citation2008; Roberts Citation2001; Timming and Brown Citation2015).

The present study argues for a need to acknowledge such ambiguities related to the roles and implications of accounting. Here, the identified roles of accounting were not attached to any particular accounting tool but to the varying roles attached to accounting in more general. Prior research has highlighted the risks and possibilities of particular tools, but what matters is also, and importantly, staying alert to the processes of how accounting is implemented and used. Echoing dialogic accounting (Brown and Dillard Citation2014, Citation2015), this study emphasises pluralism in the roles of accounting and encourages opening up rather than closing down the processes of accounting for SEs. Critical reflection from diverse socio-political perspectives is seen important in implementing accounting for SEs, paying attention to the various implications of accounting in the development of SEs. This may be important, particularly in contexts such as Finland, where the field of SEs is still pre-paradigmatic and no over-arching definition, form or legislation of SEs, or accounting for SEs, is yet established.

The empirical findings of this study clearly highlight how more-or-less all the interviewees see accounting, particularly in the form of measurement and reporting (even if understood in a relatively abstract way), as a must. However, the interviewees do not often specify what they mean by accounting in this case or what the expected benefits are. For instance, the concept of transparency was often referred to as an important guiding principle, yet when asked, no clear definition is given or shared among the interviewees. Accounting and the act of giving an account seem to have legitimacy per se, as if the mere existence of accounting, reporting or performance measurement would make the organisation exist in the eyes of others. This relates to the nature of our capitalist market society, where a lack of attention and visibility seem to question the existence of the whole organisation (Ikonen Citation2018).

Accounting is needed to create visibility and credibility for SEs and to constitute SEs as legitimate institutional actors. Accounting thus has the ability to ‘make the invisible visible’, set values, construct our shared social realities and constitute organisations and performance as governable and measurable in terms of efficiency, cost-effectiveness and transparency (Burchell et al. Citation1980; Carmel and Harlock Citation2008; Miller and Power Citation2013). The abovementioned view regarding the need to measure and account for SE performance may assist in normalising the organisational goals and targets around the imperative of cost-effectiveness, ordering priorities and allocating resources and actions accordingly. Those activities that do not directly contribute to this primary goal risk being defined as non-relevant and unessential. However, this is not necessarily or not always the case as performance measurement may simultaneously serve various purposes, such as coercive and enabling (Ahrens and Chapman Citation2004). Such documentations are indeed important and in line with the present study’s aim at highlighting the pluralism in the roles of accounting. Prior research in values-based organisations however also shows that accounting, often in the form of the quantification and increased financialisation of our social sphere, may lead organisations further away from their social missions (Amslem and Gendron Citation2019; Martinez and Cooper Citation2017). The appeal of accounting, and numerical accounts in particular, as neutral, rational and transparent (Porter Citation1995) may assist in viewing accounting and measurement as rational and apolitical, that is, as ‘a wise thing to do’. Simultaneously, however, it risks omitting the inherent politics and silencing the ideological struggle and debate behind particular dominant understandings (Carmel and Harlock Citation2008; Mason Citation2012).

While the concept of SE may be captured by the market logic (Amslem and Gendron Citation2019), the present study argues that it is important to highlight and problematise the ideological nature of such capturing. The instrumentality and managerialism that dominate our understandings of social and economic relationships result from a political and ideological agenda and are achieved through decades of education and various types of everyday ideological work. It is important to recognise them as ‘social fabrications of a specific time and place, serving a specific form of society’ (Grant and Humphries Citation2006, 43). While acknowledging these as extremely powerful and widespread perspectives, the study argues for the importance of alternative conceptualisations and epistemologies related to the role of accounting in organising economic action. We should stay alert to how different understandings and implementations of accounting influence ‘the imagery of social entrepreneurship and its space of influence and intervention’ (Day and Steyaert Citation2010, 86). Further accounting studies, particularly empirical research, are encouraged to highlight the pluralism in accounting for SEs and to analyse whether such ambivalence related to the roles of accounting in SEs could translate into resistance to the dominant understandings. Furthermore, an increased understanding of the accounting-related catalysts that could lead SEs in more democratic and socially sustainable directions is needed.

Accounting is claimed to shape organisations as economic agents (Miller and Power Citation2013). The present study highlights the role of the accounting complex in shaping organisations and identities but, importantly, argues for a more nuanced understanding of the role of accounting in values-based organisations such as SEs. Echoing Miller and Power (Citation2013), accounting in itself is a fluid complex shaped by our socio-political context and history: no pre-defined ‘accounting logic’ or essence exists. Rather, ‘accounting is a variable bearer of potential institutional logics, providing the mechanism for their realization and expression at the organizational level’ (Miller and Power Citation2013, 592). The study at hand shows that various rationales exist regarding the adoption of accounting, and that multiple roles can be attached to accounting. Perhaps, depending on what sort of accounting systems and tools become adopted for SEs, different decisions will be made related to the basic questions of accounting, such as what is the timeframe to be adopted, what sort of accountability relationships become prioritised and why, what to include in the calculations, how do we set the organisational and accounting boundaries and who to include in the decision-making. These very basic accounting decisions may take us in very different directions for the development of SEs, depending on the underlying understandings of the purposes and ideological orientation of SEs that set the priorities for such decisions.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful for the editor and the two anonymous reviewers for detailed comments on the manuscript. I also gratefully acknowledge the comments provided by Matias Laine and the participants of the RESPMAN Research Seminar. This work was supported by the University of Tampere Institute for Advanced Social Research; the Foundation for Economic Education; Säätiöiden post doc -pooli (the Foundations’ Post Doc Pool); and the Academy of Finland research grant (decision no. 324215).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 I refer to social entrepreneurship as the wider institutional field comprising economic activities that combine explicit societal and financial mission, and to social enterprises as a more specific subset of activities within this field (see also Alter Citation2006; Nicholls Citation2010).

2 The discussion on hybrid organisations (see e.g. Battilana and Lee Citation2014) could also offer insights into accounting for social enterprises and how accounting may serve as a form of hybrid organizing. Hybrid organisations operate under multiple forms and logics, combining and managing the activities between these different rationales. However, the present study focuses on a specific context of social enterprises in Finland and therefore engages mainly with the literature on accounting for social enterprises, a specific type of (hybrid) organisations with a pre-defined dual purpose.

3 A voluntary label that suitable companies can apply for, granted by an independent organization, not by the government.

4 The Finnish Act on Social Enterprises (Citation1351/2003) is not a law about SEs as we understand them today but a law about work integration social enterprises, a very specific type of organisation that provides employment opportunities, particularly for the disabled and long-term unemployed.

5 Sitra (The Finnish Innovation Fund) is an independent, state-funded and future-oriented organisation whose aim is to promote sustainable well-being and economic growth.

6 See Appendix 1 for more information on the informants.

References

- Act on Social Enterprises. 1351/2003. http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/2003/en20031351.

- Agyemang, G., B. O’Dwyer, and J. Unerman. 2019. “NGO Accountability: Retrospective and Prospective Academic Contributions.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 32 (8): 2353–2366.

- Ahrens, T., and C. S. Chapman. 2004. “Accounting for Flexibility and Efficiency: A Field Study of Management Control Systems in a Restaurant Chain.” Contemporary Accounting Research 21 (2): 271–301.

- Alter, S. K. 2006. “Social Enterprise Models and their Mission and Money Relationships.” In Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change, edited by A. Nicholls, 205–232. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Amslem, T., and Y. Gendron. 2019. “From Emotionality to the Cultivation of Employability: An Ethnography of Change in Social Work Expertise Following the Spread of Quantification in a Social Enterprise.” Management Accounting Research 42: 39–55.

- André, K., C. H. Cho, and M. Laine. 2018. “Reference Points for Measuring Social Performance: Case Study of a Social Business Venture.” Journal of Business Venturing 33 (5): 660–678.

- Ansari, S., and K. J. Euske. 1987. “Rational, Rationalizing, and Reifying Uses of Accounting Data in Organizations.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 12 (6): 549–570.

- Arjaliès, D. L., and P. Bansal. 2018. “Beyond Numbers: How Investment Managers Accommodate Societal Issues in Financial Decisions.” Organization Studies 39 (5-6): 691–719.

- Aung, M., S. Bahramirad, R. Burga, M. A. Hayhoe, S. Huang, and J. LeBlanc. 2017. “Sense-making Accountability: Netnographic Study of an Online Public Perspective.” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 37 (1): 18–32.

- Baines, S., M. Bull, and R. Woolrych. 2010. “A More Entrepreneurial Mindset? Engaging Third Sector Suppliers to the NHS.” Social Enterprise Journal 6 (1): 49–58.

- Barrakett, J. 2013. “Ground Breaking Social Enterprise Research – Case Australia.” A key note speech at the FinSERN 2nd research conference on social entrepreneurship, Helsinki, Finland, November 13.

- Battilana, J., and M. Lee. 2014. “Advancing Research on Hybrid Organizing – Insights from the Study of Social Enterprises.” Academy of Management Annals 8 (1): 397–441.

- Bengo, I., M. Arena, G. Azzone, and M. Calderini. 2016. “Indicators and Metrics for Social Business: A Review of Current Approaches.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 7 (1): 1–24.

- Brown, J., and J. Dillard. 2014. “Integrated Reporting: On the Need for Broadening Out and Opening Up.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 27 (7): 1120–1156.

- Brown, J., and J. Dillard. 2015. “Dialogic Accountings for Stakeholders: On Opening Up and Closing Down Participatory Governance.” Journal of Management Studies 52 (7): 961–985.

- Brown, A. M., and C. W. Wong. 2012. “Accounting and Accountability of Eastern Highlands Indigenous Cooperative Reporting.” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 32 (2): 79–93.

- Brubaker, R. 1984. The Limits of Rationality. London: Allen and Unwin.

- Burchell, S., C. Clubb, A. Hopwood, and J. Hughes. 1980. “The Roles of Accounting in Organizations and Society.” Accounting, Organization and Society 5 (1): 5–27.

- Carmel, E., and J. Harlock. 2008. “Instituting the ‘Third Sector’ as a Governable Terrain: Partnership, Procurement and Performance in the UK.” Policy & Politics 36 (2): 155–171.

- Chapman, C. S., D. J. Cooper, and P. Miller, eds. 2009. Accounting, Organizations, and Institutions: Essays in Honour of Anthony Hopwood. Oxford: OUP.

- Chenhall, R. H., M. Hall, and D. Smith. 2013. “Performance Measurement, Modes of Evaluation and the Development of Compromising Accounts.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 38 (4): 268–287.

- Chiapello, E. 2015. “Financialisation of Valuation.” Human Studies 38 (1): 13–35.

- Chiapello, E. 2017. “Critical Accounting Research and Neoliberalism.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 43: 47–64.

- Costa, E., L. D. Parker, and M. Andreaus, eds. 2014. Accountability and Social Accounting for Social and Non-Profit Organizations. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

- Dart, R. 2004. “The Legitimacy of Social Enterprise.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 14 (4): 411–424.

- Day, P., and C. Steyaert. 2010. “The Politics of Narrating Social Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 4 (1): 85–108.

- Defourny, J., and M. Nyssens. 2010. “Conceptions of Social Enterprise and Social Entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and Divergences.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 1 (1): 32–53.

- Defourny, J., and M. Nyssens. 2012. “Conceptions of Social Enterprise in Europe: A Comparative Perspective with the United States.” In Social Enterprises, edited by B. Gidron and Y. Hasenfeld, 71–90. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Defourny, J., and M. Nyssens. 2017. “Fundamentals for an International Typology of Social Enterprise Models.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 28 (6): 2469–2497.

- Dermer, J. 1990. “The Strategic Agenda: Accounting for Issues and Support.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 15 (1-2): 67–76.

- Dey, P., H. Schneider, and F. Maier. 2016. “Intermediary Organisations and the Hegemonisation of Social Entrepreneurship: Fantasmatic Articulations, Constitutive Quiescences, and Moments of Indeterminacy.” Organization Studies 37 (10): 1451–1472.

- Dey, P., and S. Teasdale. 2013. “Social Enterprise and Dis/Identification: The Politics of Identity Work in the English Third Sector.” Administrative Theory & Praxis 35 (2): 248–270.

- Dey, P., and S. Teasdale. 2016. “The Tactical Mimicry of Social Enterprise Strategies: Acting ‘as if’in the Everyday Life of Third Sector Organizations.” Organization 23 (4): 485–504.

- Dillard, J., and M. Pullman. 2017. “Cattle, Land, People, and Accountability Systems: The Makings of a Values-Based Organisation.” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 37 (1): 33–58.

- Ebrahim, A. 2003. “Making Sense of Accountability: Conceptual Perspectives for Northern and Southern Nonprofits.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 14 (2): 191–212.

- Ebrahim, A., and K. Rangan. 2014. “What Impact? A Framework for Measuring the Scale and Scope of Social Performance.” California Management Review 56 (3): 118–141.

- Eikenberry, A. M. 2009. “Refusing the Market: A Democratic Discourse for Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 38 (4): 582–596.

- Eikenberry, A. M., and J. D. Kluver. 2004. “The Marketization of the Nonprofit Sector: Civil Society at Risk?” Public Administration Review 64 (2): 132–140.

- European Commission. 2011. More Responsible Businesses Can Foster More Growth in Europe. European Commission - IP/11/1238, October 25. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-11-1238_en.htm?locale=en.

- Finnish Social Enterprise Mark. 2014. http://suomalaisentyonliitto.fi/en/symbols/finnish-social-enterprise-mark.

- Fry, R. E. 1995. “Accountability in Organizational Life: Problem or Opportunity for Nonprofits?” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 6 (2): 181–195.

- Gibbon, J. 2010. “Enacting Social Accounting Within a Community Enterprise: Actualising Hermeneutic Conversation.” PhD thesis, University of St Andrews, Scotland.

- Gibbon, J. 2012. “Understandings of Accountability: An Autoethnographic Account Using Metaphor.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 23 (3): 201–212.

- Gibbon, J., and A. Affleck. 2008. “Social Enterprise Resisting Social Accounting: Reflecting on Lived Experience.” Social Enterprise Journal 4 (1): 41–56.

- Gibbon, J., and P. Angier. 2011. “Towards Better Understandings of Relationships in Fair-Trade Finance: Shared Interest Society and Social Accounting.” Dialogues in Critical Management Studies 1: 203–223.

- Gibbon, J., and C. Dey. 2011. “Developments in Social Impact Measurement in the Third Sector: Scaling up or Dumbing Down?” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 31 (1): 63–72.

- Gilbert, N. 2002. Transformation of the Welfare State. The Silent Surrender of Public Responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goddard, A., and M. Juma Assad. 2006. “Accounting and Navigating Legitimacy in Tanzanian NGOs.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 19 (3): 377–404.

- Goretzki, L., S. Mack, M. Messner, and J. and Weber. 2018. “Exploring the Persuasiveness of Accounting Numbers in the Framing of ‘Performance’ – A Micro-Level Analysis of Performance Review Meetings.” European Accounting Review 27 (3): 495–525.

- Grant, S., and M. Humphries. 2006. “Critical Evaluation of Appreciative Inquiry: Bridging an Apparent Paradox.” Action Research 4 (4): 401–418.

- Green, K. R. 2019. “Social Return on Investment: A Women’s Cooperative Critique.” Social Enterprise Journal 15 (3): 320–338.

- Grimes, M. 2010. “Strategic Sense Making Within Funding Relationships: The Effects of Performance Measurement on Organizational Identity in the Social Sector.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34 (4): 763–783.

- Hall, M., and B. O'Dwyer. 2017. “Accounting, Non-governmental Organizations and Civil Society: The Importance of Nonprofit Organizations to Understanding Accounting, Organizations and Society.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 63: 1–5.

- Henri, J. F. 2006. “Organizational Culture and Performance Measurement Systems.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 31 (1): 77–103.

- Hines, R. D. 1988. “Financial Accounting: In Communicating Reality, we Construct Reality.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 13 (3): 251–261.

- Hopwood, A. G. 1987. “The Archeology of Accounting Systems.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 12 (3): 207–234.

- Hulgård, L. 2010. Discourses of Social Entrepreneurship – Variations of the Same Theme? EMES European Research Network Publications, WP no. 10/01.

- Ikonen, H. M. 2018. “‘Sitä palkintoo ei ehkä koskaan tule’: Toimijuuden tunnustus ja maaseudun naisyrittäjät.” Sosiologia 55 (2): 115–129.

- Johnson, M. P., and S. Schaltegger. 2016. “Two Decades of Sustainability Management Tools for SMEs: How Far Have We Come?” Journal of Small Business Management 54 (2): 481–505.

- Kaplan, R. S., and D. P. Norton. 1992. The Balanced Scorecard––Measures that Drive Performance. Harvard Business Review (January–February), 71–79.

- Kay, A., and L. McMullan. 2017. “Contemporary Challenges Facing Social Enterprises and Community Organisations Seeking to Understand Their Social Value.” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 37 (1): 59–65.

- Kerlin, J. A. 2010. “A Comparative Analysis of the Global Emergence of Social Enterprise.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 21 (2): 162–179.

- Kleinhans, R., N. Bailey, and J. Lindbergh. 2019. “How Community-Based Social Enterprises Struggle with Representation and Accountability.” Social Enterprise Journal 16 (1): 60–81.

- Larrinaga-Gonzalez, C., and J. Bebbington. 2001. “Accounting Change or Institutional Appropriation? A Case Study of the Implementation of Environmental Accounting.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 12 (3): 269–292.

- Light, P. C. 2010. Making Nonprofits Work: A Report on the Tides of Nonprofit Management Reform. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Luke, B. 2016. “Measuring and Reporting on Social Performance: From Numbers and Narratives to a Useful Reporting Framework for Social Enterprises.” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 36 (2): 103–123.

- Luke, B. 2017. “Statement of Social Performance: Opportunities and Barriers to Adoption.” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 37 (2): 118–136.

- Luke, B., J. Barraket, and R. Eversole. 2013. “Measurement as Legitimacy Versus Legitimacy of Measures: Performance Evaluation of Social Enterprise.” Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management 10 (3/4): 234–258.

- Maas, K., and C. Grieco. 2017. “Distinguishing Game Changers from Boastful Charlatans: Which Social Enterprises Measure Their Impact?” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 8 (1): 110–128.

- Mair, J., and I. Marti. 2006. “Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Source of Explanation, Prediction, and Delight.” Journal of World Business 41 (1): 36–44.

- Mäkelä, H., J. Gibbon, and E. Costa. 2017. “Social Enterprise, Accountability and Social Accounting.” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 37 (1): 1–5.

- Martinez, D. E., and D. J. Cooper. 2017. “Assembling International Development: Accountability and the Disarticulation of a Social Movement.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 63: 6–20.

- Mason, C. 2012. “Up for Grabs: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Social Entrepreneurship Discourse in the United Kingdom.” Social Enterprise Journal 8 (2): 123–140.

- Miller, P., and T. O’Leary. 1987. “Accounting and the Construction of the Governable Person.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 12 (3): 235–265.

- Miller, P., and M. Power. 2013. “Accounting, Organizing, and Economizing: Connecting Accounting Research and Organization Theory.” Academy of Management Annals 7 (1): 557–605.

- Ministry of Employment and the Economy. 2011. Yhteiskunnallisen yrityksen toimintamallin kehittäminen. Publications 4/2011. http://www.tem.fi/files/29202/4_2011_web.pdf.

- Ministry of Employment and the Economy. 2020. Yhteiskunnalliset yritykset Suomessa. Publications 10/2020. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/162094/TEM_2020_10.pdf.

- Mitchell, R., B. Agle, and D. Wood. 1997. “Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts.” Academy of Management Review 22 (4): 853–886.

- Modell, S. 2019. “Constructing Institutional Performance: A Multi-Level Framing Perspective on Performance Measurement and Management.” Accounting and Business Research 49 (4): 428–453.

- Mook, L., B. J. Richmond, and J. Quarter. 2003. “Integrated Social Accounting for Nonprofits: A Case from Canada.” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 14 (3): 283–297.

- Nicholls, A. 2009. “We Do Good Things, Don’t We?’: ‘Blended Value Accounting’ in Social Entrepreneurship.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 34: 755–769.

- Nicholls, A. 2010. “The Legitimacy of Social Entrepreneurship: Reflexive Isomorphism in a Pre-Paradigmatic Field.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34 (4): 611–633.

- Nicholls, A., and S. Teasdale. 2017. “Neoliberalism by Stealth? Exploring Continuity and Change Within the UK Social Enterprise Policy Paradigm.” Policy & Politics 45 (3): 323–341.

- Oakes, L. S., B. Townley, and D. J. Cooper. 1998. “Business Planning as Pedagogy: Language and Control in a Changing Institutional Field.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 43: 257–292.

- Oakes, L., and O. Young. 2008. “Accountability Re-examined: Evidence from Hull House.” Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 21 (6): 765–790.

- O’Dwyer, B. 2003. “Conceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Nature of Managerial Capture.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 10 (4): 532–557.

- Porter, T. M. 1995. Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Power, M. 2004. “Counting, Control and Calculation: Reflections on Measuring and Management.” Human Relations 57 (6): 765–783.

- Puroila, J., and H. Mäkelä. 2019. “Matter of Opinion: Exploring the Socio-Political Nature of Materiality Disclosures in Sustainability Reporting.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 32 (4): 1043–1072.

- Ridley-Duff, R. 2007. “Communitarian Perspectives on Social Enterprise.” Corporate Governance: An International Review 15 (2): 382–392.

- Roberts, J. 2001. “Trust and Control in Anglo-American Systems of Corporate Governance: The Individualizing and Socializing Effects of Processes of Accountability.” Human Relations 54 (12): 1547–1572.

- Roy, M. J., B. Macaulay, C. Donaldson, S. Teasdale, R. Baker, S. Kerr, and M. Mazzei. 2018. “Two False Positives Do Not Make a Right: Setting the Bar of Social Enterprise Research Even Higher Through Avoiding the Straw Man Fallacy.” Social Science & Medicine 217: 42–44.

- Sitra. 2012. Promotion of Social Enterprises. http://www.sitra.fi/en/economy/social-enterprises.

- Teasdale, S. 2012. “What’s in a Name? Making Sense of Social Enterprise Discourses.” Public Policy and Administration 27 (2): 99–119.

- Teasdale, S., and P. Dey. 2019. “Neoliberal Governing Through Social Enterprise: Exploring the Neglected Roles of Deviance and Ignorance in Public Value Creation.” Public Administration 97 (2): 325–338.

- Teasdale, S., F. Lyon, and R. Baldock. 2013. “Playing with Numbers: A Methodological Critique of the Social Enterprise Growth Myth.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 4 (2): 113–131.

- Timming, A. R., and R. Brown. 2015. “Employee Voice Through Open-Book Accounting: The Benefits of Informational Transparency.” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 35 (2): 86–95.

- Townley, B., D. J. Cooper, and L. Oakes. 2003. “Performance Measures and the Rationalization of Organizations.” Organization Studies 24 (7): 1045–1071.

- Unerman, J., and B. O'Dwyer. 2006. “Theorising Accountability for NGO Advocacy.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 19 (3): 349–376.

- Vik, P. 2017. “What’s so Social About Social Return on Investment? A Critique of Quantitative Social Accounting Approaches Drawing on Experiences of International Microfinance.” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 37 (1): 6–17.

- Wouters, M., and C. Wilderom. 2011. “Developing Performance-Measurement Systems as Enabling Formalization: A Longitudinal Field Study of a Logistics Department.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 33 (4-5): 488–516.