ABSTRACT

This research note elaborates on the impact assessment practices of the French Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) industry. The research was conducted by the Scientific Committee of the French public SRI label based on interviews, participative observation, a survey, and documentary evidence. SRI is usually distinguished from impact investing in terms of investors’ different intentions (contributing to sustainable development in a financially savvy way for SRI vs. demonstrating a societal impact for impact investing). We show that, beyond this distinction, the meanings and motivations behind impact assessment in the SRI community are broadly different from impact assessment practices in impact investing, creating a distance between the two communities. In fact, little is known about impact assessment practices in SRI, despite the market power of this asset class. We address this shortcoming by investigating 1) who is interested in impact assessment in the SRI industry, 2) why SRI investors want impact assessment, and 3) what impact assessment looks like in the SRI industry. We develop this analysis to suggest areas of concern and opportunities for the SRI, impact investing, and accounting communities. SRI investors’ recent appropriation of impact assessment indicates that the three communities’ interests and success will increasingly be linked to one another. The topic therefore warrants investigation.

Introduction

Impact investing comprises various approaches, from venture philanthropy through to place-based financing and social impact bonds (Hehenberger, Mair, and Metz Citation2019; Höchstädter and Scheck Citation2015). Although the motivations of impact investors differ – from ‘impact-first’ to ‘finance-first’ – impact investing funds all aim to achieve a significant societal impact. Impact investing finds its roots in the not-for-profit sector and has since strived to maintain its non-financial values. Despite the importance of the societal transformation pursued, many impact measures are primarily chosen for their ability to be easily communicable to the public (Ebrahim Citation2013; Hall and Millo Citation2018; Hockerts and Moir Citation2004). Consequently, impact assessment practices vary; although the community hopes to achieve greater standardisation in the future (Mudaliar et al. Citation2017; Reeder et al. Citation2015; Weber Citation2013).

In spite of the different metrics in use, the evaluations prepared by impact investing funds often follow what is referred to as a ‘theory of change’ (Jackson Citation2013). An impact investing fund will first identify the impact it aims to achieve (e.g. empowering women) before developing the theory of change it needs to implement in order to achieve this result. Identifying a theory of change means outlining the inputs (e.g. education), mechanisms (e.g. self-determination), outputs (e.g. high school enrollment), and outcomes (e.g. financial independence) through which the desired impact (e.g. empowerment) will be obtained. This impact assessment approach has typically been proposed by accountants, who have mainly studied impact assessment techniques in social enterprises (Costa and Pesci Citation2016; Hall, Millo, and Barman Citation2015; Muñoz, Gamble, and Beer Citation2020).

Assessing impact in the financial industry is difficult, particularly when the causal relationships between the investment and the results are hard to identify (e.g. the relationship between early childhood education and adult well-being). The impact investment community has produced several guidelines and training resources that are used worldwide (Best and Harji Citation2013). Such frameworks include the guide by the European Venture Philanthropy Association (EVPA) (Hehenberger, Harling, and Scholten Citation2013); Social Return on Investment (SROI) (Gibbon and Dey Citation2011; Vik Citation2017); impact metrics such as the BACO (Best Available Charitable Option) developed by the venture philanthropy investor Acumen; or the GIRRS (Global Impact Investment Rating System).Footnote1 Although they offer valuable insights, these guidelines alone are not enough. Human judgment remains essential since there are many ways of calculating impact and numerous possible interpretations of the effects that have been achieved (Barman Citation2015; Hehenberger, Mair, and Metz Citation2019; Silva, Nuzum, and Schaltegger Citation2019). In impact assessment, context matters.

Until a few years ago, impact investors would have been the only investors to conduct an impact assessment. This is no longer the case. Socially Responsible Investors (SRI) now aim to demonstrate their practical impact (Arjaliès and Durand Citation2019; Vörösmarty et al. Citation2018). SRI mutual funds differ from impact investing funds (Busch et al. Citation2021). SRI investors typically invest in listed multinational companies and focus their non-financial efforts on the issuers’ selection process rather than on the results achieved through their investments. For instance, while an impact investing fund will aim to demonstrate the reduction of carbon emissions achieved through financing wind turbines, an SRI fund will calculate the carbon ‘score’ of the companies present in its portfolio (Dumas and Louche Citation2016). This type of focus has led some observers to label SRI practices as greenwashing since SRI and conventional portfolios tend to be the same, and the practical impacts of SRI appear to be very limited (Olatubosun and Nyazenga Citation2019; Feront and Bertels Citation2021). It remains difficult to envisage how an investor owning a tiny percentage of shares in a large company could prove that its investment makes a difference – however good its intentions may be.

Despite the apparent contradictions between impact assessment principles and SRI investment practices, the SRI community has resolutely decided to shift gear (Kölbel et al. Citation2020; Vörösmarty et al. Citation2018; Busch et al. Citation2021). For instance, the French public SRI label that provides a national certification to SRI funds now aims to include impact assessment in its regulatory policy. However, little is known about the SRI community’s ongoing transformation and evaluation practices (Muñoz, Gamble, and Beer Citation2020). Why do SRI investors want to perform impact assessments? What does impact assessment mean in this context? What are the potential consequences for the SRI, impact investing, and accounting communities?

This research note addresses these gaps through a research project led by the Scientific Committee (i.e. the authors of this article) of the French public SRI label.Footnote2 The Scientific Committee comprises academics appointed by the French Ministry of the Economy and Finance. Their role is notably to guarantee that the SRI label does not support greenwashing practices. Data collection included participative observation of the discussions between professionals regarding impact assessment, the interview of the country’s leading actors in impact assessment and SRI, an online national survey – which gathered the answers of 151 investment management professionals – and documentary evidence. France is a leading country for SRI, with more than 50 asset managers and owners actively involved in the industry and one of the highest amounts of green assets (Eurosif Citation2018, Citation2021). Its SRI regulation is expected to shape European regulation. As members of the Scientific Committee of the SRI label, we had privileged access to the industry’s ongoing discussions on impact assessment. Our academic freedom guarantees the independence of our writing. It is nevertheless important to mention that the findings shared in this research note do not represent the public SRI label, the industry, or the French government. They are our interpretations and should not be ascribed to others.

In this research note, we argue that the SRI industry’s ongoing transformation might have significant consequences for impact investing and accounting. First, we show that although SRI investors appropriate the vocabulary of impact assessment, superficially mirroring what impact investors aim to achieve, they do not embrace their practices. Given the market power of SRI compared to impact investing (an estimated EUR 4 trillion for ESG Integration in Europe in 2018 vs. EUR 108 billion for impact investing (Eurosif Citation2018)), the appropriation of impact assessment by SRI funds is certainly not without consequences for impact investing. The penetration of impact measures into the SRI industry could either support the development of impact investing or threaten its meaning and legitimacy by confusing the two practices.

Second, we argue that although the SRI industry genuinely aims to fight against greenwashing, investment managers’ motivations vary, with differing levels of commitment to the impact’s societal dimension. SRI investors must overcome numerous challenges to shift from ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) criteria to impact. For instance, SRI mutual funds do not employ the theory of change or use counterfactuals when performing their impact assessments. This omission and the resemblance of SRI impact assessment to traditional ESG evaluation practices pose a risk of greenwashing accusations that could endanger both SRI and impact investing (Busch et al. Citation2021).

Third, due to the rise of assurance concerns for new types of financial instruments such as green bonds (International Capital Market Association Citation2021), the accounting profession may need to step forward to shape impact assessment practices, bearing the responsibility for identifying potential greenwashing patterns. Although the profession is currently focused on the non-financial standards wars between the SASB, Integrated Reporting, IFRS, or the European Commission (Cho Citation2020), to name but a few, the investment community has already moved to the next stage of reporting: discrete and unregulated impact assessment (Busch et al. Citation2021; O’Dwyer and Unerman Citation2020). Indeed, this research note shows that accountants were mainly absent from the discussions regarding impact assessment regulation in the French SRI label. By revealing the current impact assessment practices in the SRI industry, this research note enriches accountants’ knowledge on a matter that is likely to be significant in the accounting profession in the years to come. If they do not understand what is happening inside the SRI community, accountants might fail to meet these challenges. This study also offers unique real-time insights that could become a reference for future research on the topic.

The new challenges posed by performing impact assessments in SRI cannot be grasped without understanding the genealogy of the measurement systems in the industry, as described in the first section of the research note. The second section presents the French public SRI label and the methodological standpoint adopted in this research note. The third section summarises the current state of the French SRI industry’s impact assessment practices in terms of three main themes: 1) Who is interested in impact assessment in the SRI industry? 2) Why do SRI investors want impact assessment? and 3) What does impact assessment look like? Finally, the discussion section examines the implications of these findings for the SRI, impact investing, and accounting communities.

From negative screening to impact assessment: a brief genealogy of SRI

SRI has shifted from a niche gathering of a handful of ethical investors to becoming mainstream (Arjaliès Citation2010; Crifo and Mottis Citation2016; Yan, Ferraro, and Almandoz Citation2019). In 2018, it was estimated that US$30.7 trillion worth of assets integrated non-financial criteria, in other words about half of the global assets under management.Footnote3 A new trend is emerging from these practices: impact. The notion of impact is complex and multi-faceted. The word comes from the Latin impactus, which means ‘to push into, drive into, strike against’. By referring to the notion of impact, investment management professionals want to show that they are making a change (Busch et al. Citation2021). To appreciate the novelty of the concept and its implications for SRI actors, we need to understand the differences between negative screening, engagement, ESG integration, and impact assessment: the main strategies favoured today by the SRI industry.

Negative screening

SRI first emerged as an ethical practice whose goal was to align investments with their investors’ religious beliefs, mainly by excluding companies that did not abide by those principles. Although not at the core of most practices included in today’s SRI movement, negative screening remains topical (Louche, Arenas, and Van Cranenburgh Citation2012). For instance, Islamic finance, which involves financing companies following Sharia principles, was estimated at US$2.88 trillion worth of assets in 2019Footnote4 (Hayat, Den Butter, and Kock Citation2013). Some non-religious SRI funds also employ negative screening in their selection of companies. For instance, European investors have started to divest from the fossil fuel industry, both for ethical and financial reasons. They judge oil resource exploitation as wrong for the planet and financially risky, with many stocks becoming stranded assets. Negative screening raises risk exposure issues since it reduces the investment universe – and hence portfolio diversification – but it is relatively easy to implement (i.e. by excluding companies). Screening can also be ‘positive’ if only a few sectors referred to as positive for the environment or society are selected. Thematic funds that invest only in renewable energy or companies adopting bottom of pyramid strategies are a good example. Given the importance of normative views in this approach, previous research on negative screening has attempted to understand the antecedents and practices of such decisions (Louche, Arenas, and Van Cranenburgh Citation2012).

Shareholder engagement

From a historical perspective, the second approach to SRI appeared in the aftermath of the anti-Apartheid movement and is referred to as shareholder engagement. Instead of excluding companies from portfolios, engaged investors used their shares in these companies to move them towards better social and environmental practices (Gond and Piani Citation2013). Shareholders can use proxy voting, which involves voting against or favouring certain resolutions at the company’s annual meetings (Agrawal Citation2012). They can also propose resolutions, such as asking companies to report their carbon emissions. Or they can engage in one-on-one practices during which they exchange directly with the companies whose shares they own. This form of engagement is long and fastidious but facilitates learning and cooperation for both parties (Ferraro and Beunza Citation2018). In many countries, investment management professionals must report on their proxy voting policy. Shareholder engagement is therefore widely practiced all over the world. However, its effects are difficult to uncover since most investment managers have limited influence on companies. First, they tend to have a small number of shares compared to the total amount of shares available in the market. Second, they are incentivized to avoid strong positions on climate change or gender diversity topics, since clients of the same mutual fund might disagree on those issues. Faced with these difficulties, most research in this area has focused on how investors can successfully engage with companies (Goodman et al. Citation2014; DesJardine and Durand Citation2020).

ESG integration

The most abundant publications in the SRI field belong to what is usually called ESG Integration (van Duuren, Plantinga, and Scholtens Citation2016). This approach integrates ESG criteria into investment practices, generally to improve financial performance (Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim Citation2018; Dumas and Louche Citation2016). This inclusion aims to select companies that better manage their societal risks and that have transformed societal issues into a competitive advantage (e.g. green products) (Ioannou and Serafeim Citation2015). The bulk of the research explores the relationships between ESG and financial performance (Flammer Citation2015). Although recent meta-analyses have suggested that ESG integration is financially beneficial, the academic consensus remains unclear (Chatterji et al. Citation2016; Orlitsky, Schmidt, and Rynes Citation2003; Revelli and Viviani Citation2015; Van Beurden and Gössling Citation2008). Endogeneity problems, a lack of comparable historical data, and disagreement about what ESG actually includes count among the issues usually identified by the researchers who question these results (Chatterji, Levine, and Toffel Citation2009). Qualitative accounts of SRI practices show that practitioners share similar problems since ESG criteria are difficult to include in the financial models in use (Beunza and Ferraro Citation2019; Déjean, Gond, and Leca Citation2004; Casasnovas and Ferraro Citation2021). Despite those struggles, the SRI industry has gradually come to use a standard set of indicators offered by a handful of social rating agencies, including criteria such as carbon emissions, board diversity, or human rights violations.

Impact assessment

ESG integration has been key to the mainstreaming of SRI. By using a financial lens, investment management professionals could gradually transform their practices towards including non-financial criteria previously outside their realm of competencies and beliefs (van Duuren, Plantinga, and Scholtens Citation2016; Arjaliès Citation2010). The emergence of impact assessment reflects a new direction (Kölbel et al. Citation2020; Vörösmarty et al. Citation2018). As explained above, impact investing, whose primary goal is to produce social and environmental benefits through targeted investments in specific projects – e.g. social housing or mobile education applications – is not new (Agrawal and Hockerts Citation2021; Barman Citation2015). A by-product of venture philanthropy, impact investing applies traditional techniques to settings that were previously outside the scope of investors, such as social enterprises or public-private partnerships (Cooper, Graham, and Himick Citation2016; Höchstädter and Scheck Citation2015). Financial returns are usually lower, but the societal impact of these investments is relatively demonstrable and sizeable. The integration of impact assessment measures by SRI investors is a much more recent phenomenon (Busch et al. Citation2021). Encouraged by initiatives such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) launched by the United Nations in 2017, the SRI industry now wants to demonstrate its positive impacts (Bebbington and Unerman Citation2018; Hollensbe et al. Citation2014). The form, content, and evaluation of these impacts, however, remain relatively unclear. Are there significant differences between this approach and the previous ones? Are investors able to measure their impacts, and if so, how? What motivates investors to shift towards impact? We do not know. The challenges of impact assessment in the SRI industry are numerous, as the next section will explain.

The challenges of impact assessment in the SRI industry

The notion of impact assessment has recently appeared in the SRI industry. The concept and practices attached to the evaluation of impact are not new, as the literature on impact investing has shown (Hehenberger, Mair, and Metz Citation2019; Muñoz, Gamble, and Beer Citation2020). Already in 1970, the National Environmental Policy Act in the United States required federal agencies to factor in the environmental impacts of their projects in order to be approved (Caldwell Citation1988). Environmental and social indicators at the global level abound, such as the OECD framework for measuring well-being or the quantity of solid waste diversion and disposal. According to the OECD, impact refers to the primary and secondary long-term effects, positive and negative, produced by an intervention, directly or indirectly, voluntarily or not.Footnote5 Burckart, Lydenberg, and Ziegler (Citation2018, 10) translated this definition for SRI as the direct incremental change caused by investors’ individual market transactions (portfolio-level activities).

Impact assessment in the accounting literature primarily refers to the practices of social enterprises (e.g. SROI, theory of change – see the Introduction above) (Gibbon and Dey Citation2011; Vik Citation2017). Impact assessment in impact investing revolves around the notions of additionality, counterfactuals, and intentionality (Brest and Born Citation2013; Busch et al. Citation2021). Additionality is something (e.g. outcomes) that would not have happened otherwise, i.e. without a specific intervention, policy, or investment.Footnote6 A counterfactual is an estimate of the outcomes that would have occurred without the intervention. In the impact bond context, a counterfactual enables a comparison with what would have happened without the impact bond. The counterfactual is an essential element in assessing the additionality of an intervention or investment.Footnote7 Intentionality refers to how impact investors, like philanthropists, invariably intend to achieve social or environmental goals (Brest and Born Citation2013). Unlike the guidelines provided by the social enterprise and impact investing communities, there is no indication of how SRI investors should measure impact, aside from the need for the ‘quantifiable assessment of established performance indicators’ (Burckart, Lydenberg, and Ziegler Citation2018, 10). SRI differs from impact investing, notably with respect to investors’ intentions (contributing to sustainable development in a financially savvy way for SRI vs. demonstrating a societal impact for impact investing). The impact assessment practices in the SRI industry are different from those in impact investing, creating a distance between the two communities.

Our literature review of impact assessment identifies several challenges that might explain the absence in SRI of impact assessment elements usually found in impact investing: the lack of counterfactuals, the short time horizon, and aggregation at the portfolio level. We do not pretend that this list is exhaustive, but these points appear to be particularly salient among the mainstream SRI funds that have attempted to attain the public SRI label. The difficulties are not mutually exclusive with the notions of additionality and intentionality essential to the impact investing community (see above).

The lack of counterfactuals

First, impact assessment evaluates the effects of an investment on a practical situation compared to the case without this investment (i.e. counterfactual reasoning). It then attempts to reveal a causal mechanism linking the investment to the changes observed in a particular setting. For instance, investors would like to determine how investing in renewable energies has reduced carbon emissions. This analysis is difficult to achieve in SRI since most environmental and social issues targeted by SRI funds are global and systemic (i.e. investees are multinational companies), and are hence likely to evolve due to various reasons and the influence of diverse stakeholders (Costa and Pesci Citation2016; Ormiston Citation2019). To control for these external factors, investors would need to use statistical matching techniques to compare the effects of two similar investment types, one including ESG factors, the other not. Such pairings, however, are difficult to reproduce in natural settings, such as financial markets.

Short time horizon

The second problem for impact assessment in SRI is the short time horizon of mutual fund investments. In 1960, the NYSE’s average holding period for stocks was eight years and four months; in 2000, it was one year and two months; and in 2016, it was estimated to be only four months.Footnote8 Such limited involvement would appear to cast doubt on the appropriateness of attributing the observed changes to SRI (Louche et al., Citation2019). Transforming practices towards better social and environmental outcomes requires time and commitment (Bansal and DesJardine Citation2014; Busch, Bauer, and Orlitzky Citation2016).

Aggregation at the portfolio level

The last issue that SRI faces with impact assessment relates to the need to aggregate portfolio level measures. This aggregation is challenging in two respects. First, it implies adding or subtracting the assessments of individual companies to give an overall evaluation of the portfolio. This compilation is not easy since the types of effects might vary, and their comparability might be limited – SRI funds typically invest across a range of industries. The societal impacts of an insurance product are not likely to be the same as those of a chocolate bar. Second, it requires attributing the effects of a company’s investments to an environmental or social issue – also referred to as additionality (Brest and Born Citation2013). However, unless the investment finances a specific project, it is impossible to trace money flows through to their use, unlike social impact bonds.

Despite these difficulties, several initiatives have recently been launched to support the development of impact assessment in SRI. The Investment Integration ProjectFootnote9 published a set of guidelines to help investors think about the systemic impacts of problems like climate change or food security. The approach was developed by a consortium of asset management professionals and universities (Vörösmarty et al. Citation2018). The Investment Leader Group hosted by Cambridge University offers some indicators that investors could use to assess their SDG contributions (Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership 2016). The French public SRI label has initiated a working group on the topic (see below). However, what impact assessment might look like in practice remains relatively unknown.

Research context: the French public SRI label

The French SRI market is among the most active markets worldwide.Footnote10 French SRI appeared in the late 1990s and progressively became mainstream thanks to several laws promoted by certain politicians and supported by trade unions, and the actions of three (market) actors: institutional investors (e.g. public pension funds), regulators, and market intermediaries (e.g. social rating agencies) (Arjaliès Citation2010; Crifo, Durand, and Gond Citation2019; Gond and Boxenbaum Citation2013).

In January 2016, the French government launched two public labels to guarantee the ‘SRI’ quality of mutual funds bought by retail consumers.

The Energy and Ecological Transition for Climate Label (formerly called TEEC, now GREENFIN) is dedicated to products with measurable environmental benefits, usually invested in specific ‘eco-sectors’ such as renewable energies and waste management. It is managed by the French Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition. Greenfin-labelled funds are traditionally more advanced than conventional SRI funds when it comes to impact assessment and can be compared to what are often referred to as impact funds by professional bodies such as Environmental Finance.Footnote11 These Greenfin-labelled funds are not examined in the present research note. Instead, we look at more mainstream SRI funds – e.g. ESG integration, monetary funds – which are likely to be labelled under the public SRI label instead of the Greenfin label.

The public SRI label under study in this article includes a broader range of ESG criteria managed by the French Ministry of the Economy and Finance. To qualify for the label, mutual funds must exclude 20% of their initial investment universe on the basis of ESG criteria or the average ESG rating of the portfolio must be higher than the rating of the benchmark index used to measure its financial performance (see Arjaliès and Durand Citation2019 for further information). These ‘mainstream’ SRI funds are traditionally less attuned to impact assessment and less advanced than ‘impact-type’ SRI funds or social impact bonds, for instance.Footnote12

The SRI label was launched to increase the visibility of SRI products among savers in France and Europe. In October 2020, there were more than 581 labelled funds, run by 81 asset management companies representing EUR 200 billion worth of AuM.Footnote13 The 12 members of the SRI label committee are appointed by the French Ministry of the Economy and Finance and are selected based on their expertise, academic or professional experience in employee savings or corporate finance; in third-party asset management; in financial investment or consumer and saver protection; or in institutional investment or savings product distribution. The SRI label committee is supplemented by a Scientific Committee comprising four academics (the authors of this research note).

The SRI label is awarded for a three-year period, during which follow-up certification audits are conducted. The fund labelling audit is performed by two independent bodies accredited by the COFRAC (a semi-public body that ensures the quality of labelling organisations across all sectors): Afnor Certification and EY France (the only accounting firm). These organisations review the applications submitted by asset management companies and independently decide whether to award the label based on the label’s terms of reference. They conduct an annual labelling assessment and suggest technical changes that may be made to the label. The French Ministry of the Economy and Finance delegates the promotion of the label to a promoting organisation. This organisation is led by the Association Française de la Gestion Financière (French Asset Management Association – AFG) and the Forum pour l’Investissement Responsable (Forum for Responsible Investment – the French Social Investment Forum) and is responsible for collecting the fees paid by asset managers for the labelling of their funds.Footnote14

Research methods: insights from the Scientific Committee of the French public SRI label

In 2017, the label’s Scientific Committee concluded that the lack of evidence for the societal impact generated by SRI was a critical weakness of the label and a potential greenwashing threat. Following our mandate (i.e. as the Scientific Committee), we suggested that the French Ministry of the Economy and Finance launch a working group on impact assessment. After some hesitation and debates regarding the topic’s technical and political issues, the Ministry finally accepted and officially approved this group’s creation in September 2017. The working group’s primary objectives were to 1) analyze current practices and 2) suggest impact assessment metrics that could be attached to the label.

The Impact Assessment Working Group was launched on December 1, 2017 by the SRI label committee. The group’s work involved preparing a literature review on impact assessment, organising interviews of innovative players in the field from France and Europe, conducting an online survey on impact assessment, and generating recommendations for the labelling committee. Four meetings bringing together more than 30 participants from the SRI community were organised between January and June 2018. The final report, written by the Scientific Committee, which was largely distributed and included some feedback on the Scientific Committee’s recommendations, was discussed during another meeting in September 2018. The report set out our primary recommendations for the government and an in-depth analysis of impact assessment mechanisms. After submitting the report, we decided to deepen the scientific evaluation of the data we had gathered and accordingly conducted further data analysis in the form of econometric tests and qualitative coding. We hoped to contribute to the academic debate. It had always been understood with the Ministry and participants that we would conduct such research and we discussed the topic again in 2020 with several governmental entities. This research note is the result of our investigation.

The findings described below comprise insights from the Impact Assessment Survey and our participative observation of industry discussions. The interviews and documentary evidence were gathered throughout the consultation process. Our research approach is aligned with the ‘engagement research’ suggested in social and environmental accounting research. Engagement research is defined as the ‘iterative ‘reflexive and empathetic’ (Adams and Larrinaga-Gonzales Citation2007, 335) involvement of the researcher with organizations and with organizational members in the process of investigation’ (Contrafatto Citation2011, 274). Our privileged access to the discussions unfolding between SRI investors enabled us to provide valuable insights into the impact assessment practices and motivations of the SRI industry – an understanding we would not have been able to develop without this form of engagement research (Adams and Larrinaga-Gonzales Citation2007).

However, as with any mixed methods involving qualitative data, we do not argue that our results are statistically representative of the French SRI industry – hence our decision to prepare a research note rather than a traditional article. For instance, the survey administration was opportunistic, with a wide distribution among the SRI community through professional bodies, but without guaranteeing that the respondents were statistically representative of the industry. Given our extended involvement in the field, we are confident that this research note offers a fair and reasonable account of the sector’s practices and discussions regarding impact assessment. Our academic independence and the multiple data sources guarantee our ability to prevent managerial capture (Adams and Larrinaga-Gonzales Citation2007). To be as transparent as possible regarding our source of information for each of our conclusions, we will provide further details on our data collection and analysis as we present our findings below. We chose to develop our arguments and analytical points without systematically quoting excerpts from the interviews and observations conducted within the working group. We did not want these quotes to be identified. Instead, we have used evidence whose public status was clear (i.e. questionnaires, written contributions).

Who is interested in impact assessment in the SRI investment industry?

To gather the views of French SRI professionals, we designed an Impact Assessment survey administered online through Qualtrics®. We developed a first draft of the survey questions based on our literature review of impact assessment and SRI, which we tested with key participants well-versed in the topic (three academics and three investment professionals). We then used their feedback to fine-tune the survey, which ultimately included 25 questions on impact assessment and 14 questions on the respondents’ background (the questionnaire is available as supplemental material online). To maximise the response rate, respondents were not required to disclose their names or affiliations. They could also skip questions they preferred not to answer. The order of choices within questions was not randomised. The multiple-choice questions allowed for free-text responses or complete negation of all response choices, enabling respondents to raise concerns and suggest ideas not offered in the survey questions.

The survey was distributed via email with the support of several professional bodies, such as the AFG and the FIR, between March and June 2018. We received 151 responses of which 88 had been fully completed – which can be considered a large sample of the French SRI community. The results of this self-administered survey allowed us to combine both quantitative and qualitative analysis (i.e. open questions, ability to submit written comments in addition to the survey.) Integrating these two types of data source enabled us to exploit their complementarity and to interpret and generalise the quantitative data results in the light of qualitative, less standardised results. Our quantitative analysis is based only on the 88 complete responses; the qualitative analysis uses the full set of 151 responses.

The descriptive statistics of demographic variables are reported in . Our study provides insights into respondents’ profiles across several dimensions: position, seniority, age, and gender.

Table 1. Demographics and company data.

First, the survey shows that all the professions are concerned about impact assessment – not only the analysts or the asset managers but also the auditors, consultants, sales, and financial advisors. This interest is shown by the high attendance rates at the working group meetings throughout the process.

Second, the results indicate that all types of organisations are interested in impact assessment. The AuM of the respondents’ organisations varied, from small (under EUR 5 billion) to large, which was the most frequent size observed (more than EUR 50 billion). However, there were more representatives from asset management companies and institutional investors, reflecting the industry’s structure.

Last, the findings demonstrate that impact assessment is a critical strategic issue for the SRI industry. Most respondents had significant SRI expertise (SRI asset management experience with five years or more in SRI), with respondents including CEOs, Managing Directors, Heads of SRI, and Sales Directors. In addition, 77% of respondents answered that SRI was a priority and 48% disclosed that the organisation included SRI-labelled funds.

In addition to the high response rate to the survey and the strong involvement of professionals throughout the working group process, these results illustrate that impact assessment is a crucial topic for the SRI community in its entirety. This involvement also provides confidence that the results presented in our research note accurately represent the ongoing practices and discussions in the industry.

Why do SRI investors want impact assessment?

At the industry level: fighting greenwashing and maintaining competitiveness

Throughout our observation of the consultation process, it was clear that both the French government and industry envisioned impact assessment as a tool to 1) prevent greenwashing and 2) show the added value of publicly labelled SRI mutual funds compared with conventional funds. Since the SRI label argues that SRI provides social and environmental benefits, measuring these impacts seemed an excellent way to prove such an assertion. Representative consumer bodies were also adamant about the need to back up commercial arguments with substantial evidence. Professional associations and SRI lobbies also saw the inclusion of impact metrics in the SRI label as a significant opportunity for the French industry to move ahead of its competitors in the field. In other words, impact assessment was labelled as an opportunity to strengthen SRI’s business success, ethics, and transparency.

This insight was reinforced by the voluntary contributions that participants shared with us for inclusion in the ‘Report’ that we presented to the Ministry. The excerpts presented below are taken from this document, which is referred to as ‘Report’. The advantage of those excerpts is twofold. First, unlike the open survey questions, those testimonials were provided to us voluntarily and were not biased by our survey questions. Second, their publicly available status made it possible to use them in an academic publication without endangering the anonymity of the quotes.

Measuring impact is the priority area of progress for the label. A public label is, by definition, the result of a compromise. It should not become the result of a [bad] compromise. The credibility of this label in France is clearly at stake, but there is also a perspective of reflection at the European level. To sum up, the nineteenth century enabled investors to measure the financial performance of their investments. The twentieth century allowed investors to measure the financial risk associated with their investments, with all the unfinished debates that we know about. The twenty-first century will be the century of ESG impact measurement. The public SRI label, a niche within ESG integration, intends to show the way. (Asset Management Company 1, Report)

At the individual level: favoring business through external or internal means

Although the professionals we observedFootnote15 agreed on the need to prove the societal impact of SRI funds, the individual motivations exhibited were more varied (see ). Four main reasons for adopting impact assessment were cited by more than 50% of respondents: 1) communicating with customers (67%); 2) relevance for savers (58%): 3) distinguishing between SRI and conventional funds (56%); and 4) identifying the SRI themes of tomorrow (50%). Other motivations were also noted, such as the need to meet SRI label requirements (35%) or the ability to use these metrics to self-evaluate portfolios (30%).

The label plays an essential role in the development of SRI. It contributes to the fight against “SRI-washing”, and it stimulates the market. (Asset Management Company 2, Report)

Table 2. Motivations for impact assessment.

We therefore need simple, results-oriented indicators that speak to ordinary people. Of course, indicators can take the form of quantitative results or YES/NO answers. In practice, we have observed that retail customers clearly understand the presentation of companies’ business models and their relationships with sustainable development solutions. (Asset Management Company 1, Report)

Furthermore, some motivations appear to be negatively correlated. For instance, respondents who wanted to use impact assessment for self-evaluation purposes did not identify the need for impact assessment for differentiation purposes, for providing relevance for savers, or for communicating with clients regarding future SRI. This finding indicates that some ‘subgroups’ of investors seem to cluster around external and internal impact assessment motivations.

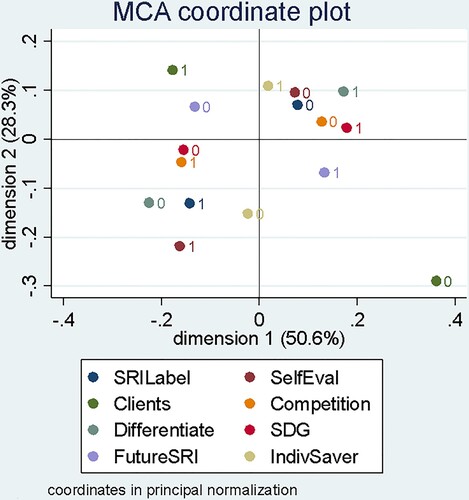

To complement our correlation analysis and since we have binary variables, we conducted a Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), which revealed the presence of two sets of motivations for impact assessment. MCA describes, explores, summarises, and visualises the information in datasets containing qualitative or categorical variables. Many variants of MCA have been proposed to improve the robustness of the method. Our approach is based on Joint Correspondence Analysis (JCA), which uses the alternating least-squares method proposed by Greenacre (Citation2006; Citation1988), and which we implemented using Stata software.

Our MCA (see ) distinguishes respondents with respect to two main dimensions. The first dimension differentiates between the Yes categories (1) and the No categories (0) for three variables. The second dimension distinguishes different motives on the bottom of the graph versus the top of the graph. Reinforcing our initial analysis of the survey, we can see two subgroups in the MCA, the first one focusing on external means (i.e. clients, differentiation, individual saver purposes), the second one mobilising internal means (i.e. for the future of SRI, the label, and self-evaluation purposes). Note that implementing SDGs can be considered both in the external and internal purpose categories, which moderates the comparison, although we initially considered as external within the MCA. The map thus enables us to identify respondents who develop impact assessment for the following reasons – as an external differentiation tool, as the internal future theme for SRI, or to implement SDGs.

Although the survey revealed various motivations, the correlation analysis and MCA enable us to identify two main subgroups of investors in terms of their impact assessment motivations. The first group hopes to use impact assessment to enhance business, mainly through external routes (e.g. differentiation, clients, etc.). The second group identifies internal means as the main way to strengthen their practices (e.g. self-evaluation, label, etc.). Overall, and unlike impact investors, both external and internal motivations for impact assessment are linked to the business’s success rather than the societal goals pursued, encouraging SRI investors to ask for different shades of green within the label itself, as shown in the following quote:

Not all SRI-labeled funds have the same impact objectives. In the context of SRI-labeled fund reporting, it would be interesting to propose different types of indicators depending on the funds’ objectives: is it relevant to require impact indicators for funds that do not seek impact? What goals are pursued by the indicators? A label graduated according to the impact sought and achieved would make it possible to enhance the value of the various approaches and ensure greater clarity for the end investor. (Asset Management Company 7, Report)

We should be careful not to automatically demand quantitative objectives since this would be akin to impact funds rather than SRI funds. We should require a difference in relation to a benchmark, not necessarily a yearly progression. (Asset Management Company 3, Report)

What does impact assessment look like?

Impact assessment: a mirroring of ESG criteria rather than a new category of evaluation practice

We used an open question to ask each respondent for a definition of impact assessment. As shows, the responses varied greatly, with each respondent offering their own explanation. Our qualitative coding for the content of the answers nevertheless revealed that most respondents associate impact assessment with three main features: 1) ESG measurement; 2) companies’ (positive) externalities or ‘contribution’, notably in alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); and 3) the need to provide evidence (see evidence in types of approach in ).

Measuring the alignment of a portfolio with the SDGs – the positive impact measured in terms of turnover generated by products and services that provide solutions – has the merit of being a transparent and easy-to-understand approach. At the level of each SDG, you can also measure negative externalities (tobacco, coal, controversies, etc.) or companies’ performance as stewards (managing positive or negative impacts), which can give an indication of company intentionality. In our view, this type of approach should not be aggregated across the 17 SDGs, the signal would be diluted and difficult to understand (risk of impact washing). (Asset Management Company 5, Report)

Table 3. Qualitative coding of impact assessment definitions.

Currently, SRI market practice in impact measurement can be characterized as relatively nascent. This is seen in the lack of standard definitions and methodologies for impact criteria, limited data availability, and the high cost of collecting and structuring data and developing relevant impact methodologies. (Asset Management Company 2, Report)

There are currently no effective indicators for monitoring the impact of the funds. The only reliable and comparable indicators are mainly related to the climate/environmental impact. Nevertheless, a choice of three indicators would be: carbon intensity (overall CO2 emissions measured in tons of carbon equivalent/company turnover weighted by the securities in the portfolio); contribution of the fund to the 2°C trajectory; % of the fund invested in companies that have signed the Global Compact. (Survey, open question)

Several quantitative indicators for measuring positive operational impact (emissions, water consumption, diversity, etc.) may also be interesting. Still, it is necessary to ensure that their definitions are standardized so that they are comparable. (Asset Management Company 6, Report)

Since our approach is very sector-based, it will be challenging to have consolidated indicators at a fund level. There are several possibilities: one possibility is to have a list of generic indicators common to all issuers and a specific list of additional indicators, i.e. per issuer (depending on its activity). These other indicators should be accompanied by a representativeness indicator, i.e. the proportion of the fund’s assets covered by the indicator in question. (Open question, survey)

In this market context, it seems necessary above all to formulate the key basic principles relating to the quality and transparency of the impact approaches used by the management companies seeking the SRI Label, without imposing a high additional cost on management companies and without constraining innovation and the appearance of new impact measures. (Asset Management Company 2, Report)

The reluctance that this may generate for players less committed than the pure players, the difficulty of defining consensual measurement tools … (Open question, survey)

Reporting is excessively burdensome, and small management companies do not have the staff and resources to produce these reports, which are becoming increasingly complex. (Open question, survey)

The constraints of small management companies, which have few resources (human, financial, tools) dedicated to SRI, must be considered. Excessive requirements in terms of impact measurement would transform the SRI Label into a label accessible only to large companies. However, the objective of the public SRI Label was to encourage the development of SRI and restricting it to a limited number of companies would be a mistake in my view. (Open question, survey)

The construction of best-in-class portfolios is not compatible with impact measurement. Impact measurement is better suited to thematic funds. (Open question, survey)

There is too little investor engagement with issuers to demand relevant indicators (concerning the issues at stake). (Open question, survey)

The means (management costs) and method (requires an authentic evaluation culture) are lacking. (Open question, survey)

Accessibility and comparability of data; cost of the ESG research required for impact measurement (this is an additional service offered by non-financial rating agencies or requires recourse to specialized providers); lack of consensus on the very definition of impact measurement; difficulty in taking these indicators into account on a day-to-day basis in management decisions (ex post indicators) (Open question, survey)

An industry at the crossroads

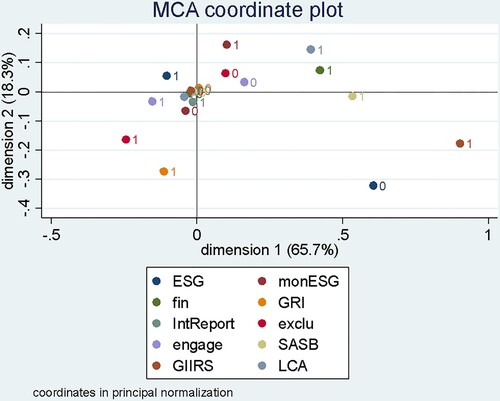

In line with our analysis of motivations, we performed an MCA to identify subgroups of investors organised by impact assessment style. The first subgroup comprises investors that use impact assessment based on: 1) ESG indicators in monetary value; 2) monetary/financial indicators; 3) SASB; and 4) Life Cycle Analysis (LCA). The MCA (see ) shows an opposition on the first dimension between the Yes categories (1) and the No categories (0). It opposes respondents who implement, or intend to implement, impact measures based on each of these activities with those who do not – this dimension opposes investors who develop impact assessment compared to others. A second subgroup appears to be based on opposing criteria: investors using impact assessment based on: 1) pure ESG indicators; 2) engagement measures; and 3) negative screening measures.

Figure 2. MCA of the impact assessment styles revealing two opposed groups (obtained from the Burt Table).

Table 4. Most commonly cited impact measures (Open Question).

Table 5. Relevant indicators for impact assessment.

Table 6. Impact assessment styles.

The second dimension distinguishes between different impact styles. In one section of the graph, we find monetary ESG/LCA/pure monetary versus GRI/Exclusion/GIIRS in the other section. This provides additional evidence of the tension between the approaches in terms of impact assessment styles.

The MCA enables us to reinforce our initial analysis and to offer two conclusions. First, SRI impact assessment does seem to mirror most of the tensions historically present in the SRI community between the ‘niche’ investors more likely to engage in ‘pure ESG’ (i.e. exclusion, GRI) and more mainstream investors who tend to use ESG integration to generate financial returns (e.g. monetary ESG, pure monetary). From this perspective, SRI impact assessment appears to be an extension of the ESG evaluation practices already in use in the SRI community, rather than an adoption of the impact assessment practices from the impact investing community.

To date, the SRI label reference framework mentions the notion of impact several times in criterion 6 and the related appendix. The current wording suggests that the impact of ESG management is measured by highlighting the ESG and human rights performance of the underlying issuers. If this is indeed the case, the use of the notion of impact as employed in the current framework is very different from the notion of impact measurement used for several decades by public and private players in impact investing. It would therefore be advisable to clarify what is expected in the reporting of SRI-labeled funds and modify criterion 6 and the corresponding appendix in line with these expectations. (Asset Management Company 7, Report)

We should reflect on the relevant basis of comparison for judging social or environmental positioning: is the use of benchmarks created to assess financial performance really appropriate? Can we create comparative measures that allow us to truly judge the relevance of the social and environmental results obtained by a company based on industrial peers whose industrial reality is socially or environmentally comparable? (Asset Management Company 4, Report)

Discussion and conclusion

As members of the Scientific Committee of the French public SRI label, we had access to discussions and practices regarding impact assessment in the SRI industry. Informed by this participative observation, together with interviews, an online survey, and documentary evidence gathered through the Impact Assessment Working Group that we managed for the French Ministry of the Economy and Finance, we came to several conclusions as summarised below.

Impact assessment in the SRI community is not the same as impact assessment in the impact investment industry

In a market where the volume of SRI-related AuM is growing swiftly, impact remains a complicated topic. Many players already struggle with ESG integration and are unable to precisely define what it means. Introducing impact measurement raises an additional series of technical and organisational issues (Busch et al. Citation2021). The French SRI industry, in particular, is very mainstream and its roots lie in conventional investment practices (Arjaliès Citation2010). Adopting impact assessment is therefore difficult since SRI investors are unfamiliar with such investing practices (Ormiston Citation2019).

Our work as the Scientific Committee of the French public SRI label and the data collected within the Impact Assessment Working Group (i.e. documentary evidence, interviews, and an online survey) led us to conclude that, for now at least, impact assessment is more a dream that SRI investors would like to achieve than a reality. This research note shows that although SRI investors want to demonstrate their impact, they are not familiar with concepts usually associated with impact assessment (e.g. the theory of change, counterfactuals, SROI). Unlike social ventures that aim to put impact assessment at the service of their societal goals (i.e. intentionality), SRI investors did not hide the fact that impact assessment was implemented for business purposes. In addition, they were not focused on a stakeholder approach either – which is usually an inclusive method favoured by social ventures to define impact assessment (Costa and Pesci Citation2016; Gibbon and Dey Citation2011). In other words, there were few accountability mechanisms. We also found no sign that the SRI community is currently shaping a common approach to impact assessment. Impact assessment practices and their understanding by SRI actors are still very close to the ESG criteria employed by the investment community. The SRI community has not yet developed guidelines and metrics that its members can widely use, nor has it formed a novel cluster of evaluation practices that could be labelled as ‘impact’.

We can therefore conclude that impact assessment in the SRI community does not mirror the impact investing community’s practices. It is mainly an extension of existing SRI approaches (e.g. negative screening, shareholder engagement, ESG integration), reproducing the historical divide between ‘mainstream’ investors more likely to favour financial performance and ‘niche’ investors more focused on the societal dimensions of impact.

The importance of the SRI label considering the lack of standards

SRI players mainly appear to adopt impact assessment for instrumental reasons linked to business success. Although the government and the industry want to avoid greenwashing, most SRI actors see impact assessment as an opportunity to strengthen their success, either through external factors (e.g. increasing their legitimacy vis-à-vis clients) or internal factors (e.g. self-evaluation). The types of impacts on society that should be favoured, for instance, were not a topic of discussion. The ability of SRI investors to effectively increase their positive impact on a population was also absent. This omission is a signal of the differences between the SRI and impact investing communities. Although, it could also be explained by the early stage of development of impact measures in the SRI industry.

In emerging markets, the quality signal that a label provides to potential customers plays a significant role. It contributes to the market’s segmentation and growth by reassuring buyers and providing suppliers with new differentiation levers (Arjaliès et al. Citation2013). In the beginning, the label can be very inclusive in terms of convincing suppliers to apply. After this first phase, the referential needs to be tightened in order to maintain the credibility of the quality signal. This hypothesis led to the creation of the Scientific Committee’s working group.

The experience demonstrated that a more demanding label inevitably generates some resistance from actors who see this as a threat to their business expansion. Impact, in this case, is a concept that meets the expectations of individual savers but places undesired pressure on investment managers. This common framework is essential for preserving a level playing field, and the label is a powerful tool with which to achieve this. This was the reasoning behind some of the recommendations made in the Scientific Committee’s Report (Arjaliès et al. Citation2018), which remain to be implemented.

From SRI to impact investing: some new connections?

Although impact assessment in the SRI community mainly reproduces existing ESG evaluation practices, the ongoing discussions around impact and greenwashing may trigger changes that eventually position a subgroup of SRI investors closer to impact investors than to traditional SRI investors. Some actors appear willing to push for more radical practices, looking for inspiration in the impact investing community (e.g. GIIRS). This development could bring both communities closer to one another, with some opportunities and potential risks for impact investing given the possible accusations of greenwashing associated with impact assessment (Busch et al. Citation2021). Given the crucial differences between the two communities’ outlook on impact assessment and the asymmetry of power between them, it appears essential that impact investors pay more attention to the ongoing debates in the SRI industry. Although there are potential allies in the SRI community, there are also potential threats to the credibility of impact assessment as a whole (Kölbel et al. Citation2020).

Beyond the ‘greenwashing’ debate associated with SRI’s impact assessment, it is also worth mentioning that this concept can renew and extend both the SRI and impact investing communities. Including impact metrics in ESG integration and negative screening can help select high performers on non-financial dimensions. Other strategies covering the worst performers could also be strengthened with clear impact measures close to the best-in-progress method, which remains marginal today. This would mean betting on an issuer’s capacity to improve its ESG rating (typically by reducing its negative externalities) by employing an explicit causal model relying on active engagement policies, for example. From this perspective, the SRI community could benefit from the impact investing community’s expertise (i.e. the theory of change) (Gibbon and Dey Citation2011).

The SRI community’s adoption of impact assessment practices could also spur investors to employ new ways of influencing issuers previously outside their scope (e.g. listed companies). It could also trigger new forms of collaboration, such as impact bonds, whose design could be based on impact investing practices while involving a more prominent investor. The market power of SRI is so strong that its appropriation of impact assessment (even in the form of a broad label for now) is likely to significantly affect investors, who should prepare accordingly.

For the French public SRI label, this kind of evolution is currently at stake. Unsurprisingly, the technical difficulties related to impact measurement and management still need to be discussed. Although everybody agrees that impact is an important dimension, there is currently no consensus on how to address these challenges. This is probably one of the fundamental issues to be addressed regarding the future of the SRI label and SRI in general.

Implications for the accounting community: probably a good time to engage

Finally, despite the critical role of audit firms in monitoring the French SRI label, accountants have been relatively absent from the discussions unfolding in the investment industry. For instance, the French government authorised only one Big Four firm (EY France) to audit SRI mutual fund labelling – the other authorised auditor belongs to the certification world. Accounting bodies have tended to focus on the debates surrounding the standardisation of non-financial reporting and the heated arguments between the different approaches (e.g. SASB, IIRC, European Taxonomy, IFRS, etc.) (Cho Citation2020). Although perfectly understandable, this lack of attention regarding discussions of impact assessment in the SRI community might raise significant issues in the years to come. Accountants may be progressively excluded from a substantial market (i.e. SRI) and may also lose ground with their current clients since non-financial evaluation practices in the investment industry typically prefigure the reporting practices adopted by companies (Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim Citation2018; O’Dwyer and Unerman Citation2020). Given the assurance concerns regarding new types of financial products such as green bonds (International Capital Market Association Citation2021), it might also be the case that the accounting profession will need to shape impact assessment practices in SRI. Being involved in the discussions early on would help prepare the accounting profession to better understand the challenges at stake and to prepare for an auditing process governed by an impact regulatory framework linked to the SRI label.

This lack of interest in impact assessment in the SRI industry can also be seen in academic research. Despite impact assessment being an accounting practice, few articles have examined the question (Muñoz, Gamble, and Beer Citation2020; O’Dwyer and Unerman Citation2020). Most social and environmental accounting research focuses on integrated reporting, carbon accounting, or social accountability. This research note points to the need for accounting academics to engage with the topic. As the abovementioned interest in assurance shows, audit firms will increasingly need to control the accuracy of the declarations made by SRI investors – representing billions of AuM and a similar amount of money potentially invested in greenwashing practices. Understanding impact assessment and the difference between financial and non-financial reporting practices will be of primary importance to support this work. Last, accountants could help strengthen current impact assessment practices by sharing their knowhow and expertise. The body of knowledge developed by the social and environmental academic community could be of tremendous help in the ongoing debates surrounding the regulation of SRI funds, a disclosure requirement that will affect investors and issuers – hence virtually all listed companies. We hope this research note will encourage scholars to conduct further studies on the topic and its consequences for accounting practices.

Compliance with ethical standards/conflicts of interest

The authors are all members of the Scientific Committee of the French public SRI label. They collected the data studied in this research note through their involvement in the Impact Assessment Working Group. The conclusions of this analysis are those of the authors, and should not be ascribed to others. Further details are available in the manuscript.

Questionnaire-220111.pdf

Download PDF (103.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 https://b-analytics.net/, accessed January 29, 2020.

2 https://www.lelabelisr.fr/en/what-sri-label/, accessed February 23, 2021.

3 https://www.ipe.com/top-400/total-global-aum-table-2018/10007066.article, accessed June 21, 2019.

4 https://icd-ps.org/fr/news/refinitiv-icd-2020-report-global-islamic-finance-assets-expected-to-hit-369-trillion-in-2024, accessed February 23, 2021.

5 https://www.oecd.org/dac/results-development/what-are-results.htm, accessed June 21, 2019.

6 https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/glossary/, accessed August 5, 2021.

7 https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/glossary/, accessed August 5, 2021.

8 https://www.politifact.com/virginia/statements/2016/jul/06/mark-warner/mark-warner-says-average-holding-time-stocks-has-f/, accessed June 21, 2019.

9 https://www.tiiproject.com/, accessed January 30, 2020.

10 http://www.eurosif.org/sri-study-2016/france/, accessed July 10, 2019.

11 https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/awards/, accessed August 5, 2021.

12 See https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/awards/ for impact-type SRI funds, accessed August 5, 2021.

13 https://www.frenchsif.org/isr-esg/, accessed February 23, 2021.

14 https://www.lelabelisr.fr/, website promoting the SRI label, accessed August 3, 2021.

15 Our questionnaire included several open questions, which encouraged the respondents to highlight genuinely diverse SRI practices. These survey results were corroborated by other data sources (i.e., interviews, observation, and voluntary contributions to the ‘Report’).

References

- Adams, Carol A., and Carlos Larrinaga-Gonzales. 2007. “Engaging with Organisations in Pursuit of Improved Sustainability Accounting and Performance.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 20: 333–355.

- Agrawal, Ashwini K. 2012. “Corporate Governance Objectives of Labor Union Shareholders: Evidence from Proxy Voting.” Review of Financial Studies 25 (1): 187–226.

- Agrawal, Anirudh, and Kai Hockerts. 2021. “Impact Investing: Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 33 (2): 153–181. doi:10.1080/08276331.2018.1551457

- Amel-Zadeh, Amir, and George Serafeim. 2018. “Why and How Investors Use ESG Information: Evidence from a Global Survey.” Financial Analysts Journal 74 (3): 87–103.

- Arjaliès, Diane-Laure. 2010. “A Social Movement Perspective on Finance: How Socially Responsible Investment Mattered.” Journal of Business Ethics 92: 57–78.

- Arjaliès, Diane-Laure, Pierre Chollet, Patricia Crifo, and Nicolas Mottis. 2018. “Mesure d'Impact et Label ISR: Analyse et Recommendations” [Impact Measurement and SRI Label: Analysis and Recommendations]. Report and recommendations written by the Scientific Committee for the French Ministry for the Economy and Finance regarding the “Impact Assessment” Regulation of Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) Mutual Funds. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3559718.

- Arjaliès, Diane-Laure, and Rodolphe Durand. 2019. “Product Categories as Judgment Devices: The Moral Awakening of the Investment Industry.” Organization Science 30 (5): 885–911.

- Arjaliès, Diane-Laure, Samer Hobeika, Jean-Pierre Ponssard, and Sylvaine Poret. 2013. “Le Rôle de La Labellisation Dans La Construction d’un Marché: Le Cas de l’ISR En France.” Revue Française de Gestion 39: 93–107.

- Bansal, Pratima, and Mark R. DesJardine. 2014. “Business Sustainability: It Is About Time.” Strategic Organization 12 (1): 70–78.

- Barman, Emily. 2015. “Of Principle and Principal: Value Plurality in the Market of Impact Investing.” Valuation Studies 3 (1): 9–44.

- Bebbington, Jan, and Jeffrey Unerman. 2018. “Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: An Enabling Role for Accounting Research.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 31 (1): 2–24.

- Best, H., and K. Harji. 2013. Guidebook for Impact Investors: Impact Measurement. Toronto, ON: Purpose Capital.

- Beunza, Daniel, and Fabrizio Ferraro. 2019. “Performative Work: Bridging Performativity and Institutional Theory in the Responsible Investment Field.” Organization Studies 40 (4): 515–543.

- Brest, Paul, and Kelly Born. 2013. “When Can Impact Investing Create Real Impact.” Stanford Social Innovation Review 11 (4): 22–31.

- Burckart, William, Steven D. Lydenberg, and Jessica Ziegler. 2018. Measuring Effectiveness: Roadmap to Assessing System-Level and SDG Investing.” TIIP The Investment Integration Project, IRRC Institute.

- Busch, Timo, Rob Bauer, and Marc Orlitzky. 2016. “Sustainable Development and Financial Markets: Old Paths and New Avenues.” Business & Society 55 (3): 303–329.

- Busch, Timo, Peter Bruce-Clark, Jeroen Derwall, Robert Eccles, Tessa Hebb, Andreas Hoepner, Christian Klein, Philipp Krueger, Falko Paetzold, and Bert Scholtens. 2021. “Impact Investments: A Call for (Re) Orientation.” SN Business & Economics 1 (2): 1–13.

- Caldwell, Lynton K. 1988. “Environmental Impact Analysis (EIA): Origins, Evolution, and Future Directions.” Impact Assessment 6 (3–4): 75–83.

- Casasnovas, Guillermo, and Fabrizio Ferraro. 2021. “Speciation in Nascent Markets: Collective Learning Through Cultural and Material Scaffolding.” Organization Studies. doi:10.1177/01708406211031733.

- Chatterji, Aaron, Rodolphe Durand, David I. Levine, and Samuel Touboul. 2016. “Do Ratings of Firms Converge? Implications for Managers, Investors and Strategy Researchers.” Strategic Management Journal 37: 1597–1614.

- Chatterji, Aaron K., David I. Levine, and Michael W. Toffel. 2009. “How Well Do Social Ratings Actually Measure Corporate Social Responsibility?” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 18 (1): 125–169.

- Cho, Charles. 2020. My Comment Letter to the IFRS Foundation about the Consultation Paper on Sustainability Reporting.” Accounting Resources Centre- European Accounting Association (blog). Accessed December 31, 2020. https://arc.eaa-online.org/blog/my-comment-letter-ifrs-foundation-about-consultation-paper-sustainability-reporting.

- Contrafatto, Massimo. 2011. “Social and Environmental Accounting and Engagement Research: Reflections on the State of the Art and New Research Avenues.” Economia Aziendale Online 2 (3): 273–289.

- Cooper, Christine, Cameron Graham, and Darlene Himick. 2016. “Social Impact Bonds: The Securitization of the Homeless.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 55: 63–82.

- Costa, Ericka, and Caterina Pesci. 2016. “Social Impact Measurement: Why Do Stakeholders Matter?” Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 7 (1): 99–124.

- Crifo, Patricia, Rodolphe Durand, and Jean-Pascal Gond. 2019. “Encouraging Investors to Enable Corporate Sustainability Transitions: The Case of Responsible Investment in France.” Organization & Environment 32 (2): 125–144.

- Crifo, Patricia, and Nicolas Mottis. 2016. “Socially Responsible Investment in France.” Business & Society 55 (4): 576–593.

- Déjean, Frédérique, Jean-Pascal Gond, and Bernard Leca. 2004. “Measuring the Unmeasured: An Institutional Entrepreneur Strategy in an Emerging Industry.” Human Relations 57 (6): 741–764.

- DesJardine, Mark R., and Rodolphe Durand. 2020. “Disentangling the Effects of Hedge Fund Activism on Firm Financial and Social Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 41 (6): 1054–1082.

- Dumas, Christel, and Celine Louche. 2016. “Collective Beliefs on Responsible Investment.” Business & Society 55 (3): 427–457.

- van Duuren, Emiel, Auke Plantinga, and Bert Scholtens. 2016. “ESG Integration and the Investment Management Process: Fundamental Investing Reinvented.” Journal of Business Ethics 138 (3): 525–533.

- Ebrahim, Alnoor. 2013. Let’s Be Realistic about Measuring Impact.” Harvard Business Review Blogs (March 13, 2013) (blog). 2013. http://blogs.hbr.org/hbsfaculty/2013/03/lets-be-realistic-about-measur.html.

- Eurosif. 2018. European SRI Study.” Eurosif Studies.

- Eurosif. 2021. Eurosif Report 2021 - Fostering Investor Impact - Placing It at the Heart of Sustainable Finance.” Eurosif Studies.

- Feront, Cecile, and Stephanie Bertels. 2021. “The Impact of Frame Ambiguity on Field-Level Change.” Organization Studies 42 (7): 1135–1165.

- Ferraro, Fabrizio, and Daniel Beunza. 2018. “Creating Common Ground: A Communicative Action Model of Dialogue in Shareholder Engagement.” Organization Science 29 (6): 1187–1207.

- Flammer, Caroline. 2015. “Does Corporate Social Responsibility Lead to Superior Financial Performance? A Regression Discontinuity Approach.” Management Science 61 (11): 2549–2568.

- Gibbon, Jane, and Colin Dey. 2011. “Developments in Social Impact Measurement in the Third Sector: Scaling up or Dumbing Down?” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 31 (1): 63–72.

- Gond, Jean-Pascal, and Eva Boxenbaum. 2013. “The Glocalization of Responsible Investment: Contextualization Work in France and Quebec.” Journal of Business Ethics 115 (4): 707–721.

- Gond, Jean-Pascal, and Valeria Piani. 2013. “Enabling Institutional Investors’ Collective Action: The Role of the Principles for Responsible Investment Initiative.” Business & Society 52 (1): 64–104.

- Goodman, Jennifer, Céline Louche, Katinka C van Cranenburgh, and Daniel Arenas. 2014. “Social Shareholder Engagement: The Dynamics of Voice and Exit.” Journal of Business Ethics 125 (2): 193–210.

- Greenacre, Michael J. 1988. “Correspondence Analysis of Multivariate Categorical Data by Weighted Least-Squares.” Biometrika 75 (3): 457–467.

- Greenacre, Michael. 2006. “From Simple to Multiple Correspondence Analysis.” Multiple Correspondence Analysis and Related Methods, 41–76.

- Hall, Matthew, and Yuval Millo. 2018. “Choosing an Accounting Method to Explain Public Policy: Social Return on Investment and UK Non-Profit Sector Policy.” European Accounting Review 27 (2): 339–361.

- Hall, Matthew, Yuval Millo, and Emily Barman. 2015. “Who and What Really Counts? Stakeholder Prioritization and Accounting for Social Value.” Journal of Management Studies 52 (7): 907–934.

- Hayat, Raphie, Frank Den Butter, and Udo Kock. 2013. “Halal Certification for Financial Products: A Transaction Cost Perspective.” Journal of Business Ethics 117 (3): 601–613.

- Hehenberger, Lisa, Anna-Marie Harling, and Peter Scholten. 2013. “A Practical Guide to Measuring and Managing Impact.” European Venture Philanthropy Association.

- Hehenberger, Lisa, Johanna Mair, and Ashley Metz. 2019. “The Assembly of a Field Ideology: An Idea-Centric Perspective on Systemic Power in Impact Investing.” Academy of Management Journal 62 (6): 1672–1704.

- Höchstädter, Anna Katharina, and Barbara Scheck. 2015. “What’s in a Name: An Analysis of Impact Investing Understandings by Academics and Practitioners.” Journal of Business Ethics 132 (2): 449–475.

- Hockerts, Kai, and Lance Moir. 2004. “Communicating Corporate Responsibility to Investors: The Changing Role of the Investor Relations Function.” Journal of Business Ethics 52 (1): 85–98.

- Hollensbe, Elaine, Charles Wookey, Loughlin Hickey, Gerard George, and Cardinal Vincent Nichols. 2014. “Organizations with Purpose.” Academy of Management Journal 57 (5): 1227–1234.

- International Capital Market Association. 2021. Green Bond Principles (GBP).” International Capital Market Association. https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/2021-updates/Green-Bond-Principles-June-2021-140621.pdf.

- Ioannou, Ioannis, and George Serafeim. 2015. “The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Investment Recommendations: Analysts’ Perceptions and Shifting Institutional Logics.” Strategic Management Journal 36 (7): 1053–1081.

- Jackson, Edward T. 2013. “Interrogating the Theory of Change: Evaluating Impact Investing Where It Matters Most.” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 3 (2): 95–110.

- Kölbel, Julian F, Florian Heeb, Falko Paetzold, and Timo Busch. 2020. “Can Sustainable Investing Save the World? Reviewing the Mechanisms of Investor Impact.” Organization & Environment 33 (4): 554–574.

- Louche, Celine, Daniel Arenas, and Katinka C. Van Cranenburgh. 2012. “From Preaching to Investing: Attitudes of Religious Organisations Towards Responsible Investment.” Journal of Business Ethics 110 (3): 301–320.

- Louche, Celine, Timo Busch, Patricia Crifo, and Alfred Marcus. 2019. “Financial Markets and the Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy: Challenging the Dominant Logics.” Organization & Environment 32 (1): 3–17.

- Mudaliar, Abhilash, Aliana Pineiro, Rachel Bass, and Hannah Dithrich. 2017. The State of Impact Measurement and Management Practice.” Global Impact Investing Network.

- Muñoz, Pablo, Edward Gamble, and Haley Beer. 2020. “Impact Measurement in an Emerging Social Sector: Four Novel Approaches.” Academy of Management Discoveries, doi:10.5465/amd.2020.0044.

- O’Dwyer, Brendan, and Jeffrey Unerman. 2020. “Shifting the Focus of Sustainability Accounting from Impacts to Risks and Dependencies: Researching the Transformative Potential of TCFD Reporting.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 33 (5): 1113–1141.