ABSTRACT

Following the financial crash of 2008, many scholars have highlighted flaws and inadequacies in emerging macroprudential regulatory regimes. A missing ingredient in the political economy of post-crisis financial reform is the neglect of questions of social purpose in both policy debate and IPE scholarship. Social purpose is defined as a vision of the desirable or good economic system, derived from combinations of economic analysis and ethical reasoning. It is of particular relevance and importance to macroprudential regime building, because the foundational macroprudential conceptual frameworks developed by the Bank for International Settlements and the Geneva Group from 2000 onwards display the features of a macrosocial ontology that draw on a Minsky–Keynes tradition. By focusing on systemic outcomes and collective social expectations, such an ontology creates the basis for so-called macro-moralities that provide ethical justifications for public forms of systemic stabilisation. However, a variety of epistemological, professional, institutional and political barriers have impeded relevant expert groups and political actors’ willingness and ability to actively translate macroprudential ontology into a systemic vision, or sense of social purpose that could be communicated to the public at large.

To be precise the most important concern in court politics is access to the mind of the prince. And if economics is too important to be left to the economists, it is certainly too important to be left to economist courtiers. Economic issues must become a serious public matter and the subject of debate if new directions are to be undertaken. Meaningful reforms cannot be put over by an advisory and administrative elite that is itself the architect of the existing situation. Unless the public understands the reason for change they will not accept its cost; understanding is the foundation of legitimacy for reform. (Minsky, Citation1986, p. 321).

Introduction

How is it that economic ideas that offer critical assessments of financial market pathologies can be applied in ways that effectively maintain those very same processes? Using the case of the emergence of macroprudential regulation since the financial crash of 2008, this article argues that when ideas are not translated into, or accompanied by, a clearly articulated sense of the ‘social purpose’ they should serve, they are likely to be conservative in application. In making this case, the article calls for a renewed and more explicit focus on the concept and processes of social purpose as a series of interactive discursive and political processes in the study of International Political Economy (IPE).

After John Ruggie's seminal 1982 article, which established the conceptual and empirical importance of social purpose (Ruggie, Citation1982), the treatment of social purpose has been implicit, incidental and fleeting in subsequent scholarship, not least because it remains a slippery concept that was never formally defined.Footnote1 Social purpose is defined here as a systemic vision, which specifies the purpose, function and contribution of the financial system, in wider economic and social terms, derived from combinations of empirical and normative reasoning, that is communicated publicly and explicitly to build an inter-subjective consensus concerning appropriate economic goals, principles, values and activities. Ontology, or accounts of the constituent processes, properties and relations of economic life, as previous scholarship in this journal has illustrated, provide foundations for ethical and normative orientation (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006). Scholars of IPE can, therefore, place the study of social purpose on a more systematic footing by investigating how specific economic ontologies carry within them distinct moral possibilities (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006, p. 610). The argument advanced here goes beyond Best and Widmaier's important contribution to illustrate that normative and moral reasoning does not automatically emerge from a given ontology. When that ontology takes the form of what they call a macrosocial ontology, developing related ‘macro-moralities’ requires an active process of translation by expert groups and political actors, communicating a systemic vision, or social purpose derived from that ontology. In the macroprudential case, this process of translation has not materialised, because a macrosocial ontology that shares many features with the work of Keynes and Minsky, has not led to the kind of normative and moral arguments about financial reform, that both of these scholars developed in earlier eras. The article makes this argument and investigates the reasons why macroprudential ambition and efforts to explicitly connect it to a sense of social purpose have been so limited.

The limited nature of financial reform after the financial crash has been the subject of considerable scholarly debate and attention (Bieling, Citation2014; Helleiner, Citation2014; Konings, Citation2016; Lall, Citation2012; Pagliari & Young, Citation2014). The need for macroprudential regulatory regimes was one of the primary changes identified by numerous expert groups convened by the official community following the financial crash of 2008, and was officially endorsed as a policy priority by the G20 summits during 2009 (Baker, Citation2013a). It was seen by some in the policy world to signal a ‘new ideology’, or approach to financial governance (Borio, Citation2011; Haldane, Citation2009). Macroprudential policy involves pre-emptive interventions to minimise the threat of financial instability and moderate cyclical risk-taking across financial systems as a whole. It promised a greater role for public authorities in overseeing and framing private decision-making, after two decades of light-touch oversight based on faith in private risk management techniques. It also emphasised macro-financial instability over equilibrium, while critiquing many of the assumptions of the efficient market approach and private risk management modelling techniques such as value at risk (VaR). In this sense, the macroprudential turn has represented a degree of crisis-induced intellectual change (Baker, Citation2013a, Citation2013b; CitationDatz, 2013; Engelen et al., Citation2011; Erturk, Froud, Leaver, Moran, & Williams, Citation2011). However, there is a growing sense that the ‘macroprudential turn’, despite some degree of intellectual rupture with the last three decades, is increasingly constrained and minimal in its ambition, providing ‘perfect cover’ for a limited reform agenda overlooking distributional concerns and the case for stronger controls on markets (Helleiner, Citation2014, p. 128). Noted explanations for macroprudential minimalism include vested financial sector interests diluting macroprudential ambition (Helleiner, Citation2014); macroprudential as symbolic politics (Goodhart, Citation2015; Lombardi & Moschella, Citation2017); risk management as a form of neo-liberal governmentality (Konings, Citation2016); practical difficulties in executing macroprudential policy instruments (Butzbach, Citation2016; Stellinga & Mugge, Citation2017); a technocratic predisposition to incrementalism (Baker, Citation2013b); and an ambiguous regulatory philosophy (Cooper, Citation2011; Helleiner, Citation2014). While these potential explanations have varying merits, they all overlook an important element of the emerging political economy of macroprudential regulation.

To talk meaningfully of a ‘macroprudential perspective’ requires recognising that a combination of the staff of an international organisation (IO) –The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and a group of academic economists consciously developed and defined a macroprudential conceptual core, or ontology – as a series of claims about how the financial world is constituted by specific market processes and their macroeconomic implications. This article identifies a gap between the latent critical nature of that ontology and the relatively conservative policy activity emerging from it. More ambitious blue prints and guiding rationales for macroprudential policy are not emerging. Actors that developed macroprudential ontology (central bankers, staff of IOs and academic economists) have not pursued wider questions relating to the purpose and objectives of macroprudential regulatory regimes. Efforts at new forms of systemic financial governance are, in many national settings, consequently being conducted with little in the way of a guiding vision of what purpose the overall system, as the object of regulation, should serve.

The first section introduces, defines and revisits the concept of social purpose. A key question addressed is how scholars should approach and study social purpose. The second section scrutinises macroprudential ontology, through a combination of content analysis of the two foundational streams of conceptual work (BIS and Geneva Group) that established a macroprudential perspective, and interviews with some of these early macroprudential advocates. It establishes that macroprudential ontology displays the features of a macrosocial ontology, that draws heavily, although often implicitly, on a Keynes, Kindleberger, Minsky (KKM) tradition (Kirshner, Citation2014, p. 96). As a macrosocial ontology, it emphasises collective outcomes that are more than the sum of their parts, the limits and flaws of individual private decision-making in a context of uncertainty, and the subsequent role of self-fulfilling agent expectations in driving economic cycles and socially suboptimal financial instability (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006, p. 617). Crucially, contrary to some claims, evidence is presented to show that this ontology does contain a theory of endogenous financial instability that has a number of similarities to the earlier work of Hyman Minsky (Kregel, Citation2014). Such a macro-intellectual universe opens up potential macro-ethical orientations involving a public ethics and a collective conception of moral responsibility and agency (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006, pp. 610–611). The third section identifies that the potential moral and ethical implications of macroprudential ontology have been neglected by policy-makers, producing a lack of clarity with regards to the objectives and purposes of macroprudential policy regimes (Tucker, Citation2016a). In earlier eras, both Keynes and Minsky developed moral reasoning derived from their empirical and conceptual work, recognising this could power and legitimate their ideas and was part of the task of economics (Baker & Widmaier, Citation2014; Widmaier, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). In contrast, a combination of professional, epistemological and institutional factors have made contemporary macroprudentialists reluctant to move beyond a narrow technical mode of operation (Engelen, Johal, Leaver, Nilsson, & Williams, Citation2011, p. 189). Without purposeful actors willing to and capable of, translating ideas, into a systemic normative vision, their application is likely to result in modest technical system maintenance and management.

Financial reform, social purpose and ontology

Financial reform projects intended to produce greater degrees of financial stability impose costs on some actors. In the macroprudential case, this involves regulators potentially constraining the risk-taking activities of private financial institutions during the upswing phase of financial cycles in an effort to minimise the costs generated by episodes of financial instability. Current macroprudential tools include leverage limits/ ratios; time-varying capital requirements (e.g. the countercyclical capital buffer in Basel III); loan-to-value requirements (LTV) and loan-to-income requirements (LTI) on mortgages; margins and haircuts; and in some Asian countries restrictions on and management of foreign exchange liabilities and the levying of ‘macroprudential’ taxes. All of these instruments can affect the terms on which consumers and enterprises can access credit and conduct financial transactions. Such interventions can result in individuals or institutions perceiving that their capacity to accumulate wealth is being squeezed, potentially making them unpopular. Several prominent macroprudential advocates have noted that there is no readymade supportive constituency for such countercyclical policies (Borio, Citation2013; Haldane, Citation2013). The Minsky quote with which this paper begins, is a recognition of these kinds of costs and emphasises the importance of building public understanding and support based on public debate and justifications for financial reform couched in terms of wider benefits (social purpose). However, clear intelligible explanations can be difficult to arrive at in an area renowned for its technical complexity. This is where articulations of social purpose by policy-makers can build public support for financial reform projects, but can also guide and inform policy interventions.

Social purpose is defined here as a systemic vision of the good financial and economic system derived from a combination of analytical and normative reasoning communicated through a public discourse, that builds a widely shared intersubjective consensus (among both government elites and mass publics) concerning the desirability and benefits of a given system. Where finance is concerned, this might entail arguments about the purpose finance should serve in relation to the wider economy, including goals such as ecological sustainability, employment generation, or simply the plentiful, but relatively stable supply of credit and investment opportunities as the basis of economic efficiency. Such a vision will also identify the appropriate role and obligations of the state, and can involve reaching evaluative judgements on desirable and undesirable economic and financial activity. Social purpose can be thought of as an ongoing interactive process, in which normative claims and their systemic vision are advanced, accepted, rejected or modified by publics and elites.

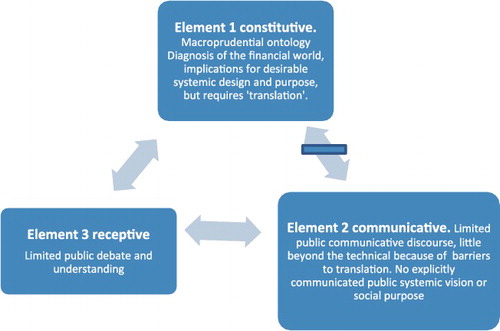

Future research into social purpose should think in terms of three elements: (1) a constitutive or content element (the primary focus here) where claims about how economic systems function, their problems and how they might be made better are established; 2) a communication element – combinations of normative and utilitarian discourses that provide explanations and justifications to the public for broad policy orientation, articulating a wider systemic vision, derived from the content element; (3) and a reception element involving public and elite reactions, behaviours and coalition building, that feeds into, drives and may modify visions of appropriate social purpose. All three of these elements will interact. The politics of social purpose is the question of whether agents are able and willing to develop and derive normative interpretations drawn from prevailing economic accounts, and whether those in turn draw supportive reactions from broad coalitions. To be functional, social purpose has to evolve into a widely shared intersubjective consensus (with domestic and international components) that enables evaluations of the intentionality and appropriateness of state and corporate agents’ behaviours.Footnote2 In the macroprudential case to date, it is argued that movement from element 1 to element 2 as part of a process of ‘translation’ (Ban, Citation2016; Campbell, Citation2004) has been limited (see ).

Social purpose was referred to on 16 occasions in one of the most influential and cited IPE articles of all time (Ruggie, Citation1982). However, in his seminal piece, John Ruggie never formally defined the concept and it has only been the subject of somewhat passing engagement in subsequent scholarship (Muzaka & Bishop, Citation2015; Ruggie, Citation2008; Van Apeldoorn, Citation2003).Footnote3 Ruggie's account did allude to the fact that social purpose refers to the normative framework of regimes (Ruggie, Citation1982, p. 384), relates to the balance between market and state authority, including how state power was to be employed in the domestic economy (Ruggie, Citation1982, p. 386). Financial reform projects and new fields of public policy such as macroprudential regulation or policy, which are in essence about expanding the range of available policy instruments to constrain financial market excess (Baker & Widmaier, Citation2014) are particularly ripe for analysis in terms of social purpose, precisely because they expand the scope of state intervention and potentially reconfigure the relationship between state and market authority. Moreover, because macroprudential policy is about system-wide financial governance and the management of systemic risk, we can reasonably expect that such an enterprise could be aided by a systemic vision.

The notion of social purpose as a form of systemic vision is congruent with Ruggie's original use of the term. ‘Embedded liberalism’ as described by Ruggie was a form of normative system governance based on the principle that governments would assume more responsibility for domestic social security under post-war Bretton Woods regimes, than under nineteenth-century ‘laissez faire liberalism’. Near-universal demands for enhanced social protection from across the political spectrum (Ruggie, Citation1982, p. 287) produced a compromise between domestic stability and an open international economy based on ‘appropriate’ domestic interventions to promote welfare and growth (Ruggie, Citation1982, p. 393). While Ruggie's account is relatively light on the norms and principles at the core of embedded liberalism, he did note that ‘international regimes provide a permissive environment for the kind of economic transactions that are complementary to the normative frameworks that have bearing on them’ (Ruggie, Citation1982, p. 404). Practising social purpose, therefore, requires identifying and encouraging normatively permissible/desirable and non-desirable types of economic activity and taking action accordingly. In the macroprudential case, such efforts have been limited. Public communicative discourses linking macroprudential regulation to normative visions of the desirable financial system are also similarly underdeveloped, internationally, and in most domestic settings.

The literature on ideas in economic governance has recognised the importance of normative claims. For example, Vivien Schmidt distinguishes between cognitive and normative ideas, with cognitive ideas, concerning what is and what to do (causal ideas, maps and recipes for policy action – macroprudential ontology) and normative ideas reaching judgements about what is good and bad and what one ought to do (Schmidt, Citation2008, pp. 306–307). John Campbell refers to normative ideas that specify how things should be (Campbell, Citation1998), while Seabrooke and Wigan consider how expert professionals use moral authority to propel ideas with moral force as well as expert analysis (Seabrooke & Wigan, Citation2016). Schmidt also considers background philosophical ideas, as world views, underlying assumptions, values and principles that structure knowledge in society and are rarely contested except in times of crisis (Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 306). More recently, Smith has called for greater attention on the hierarchy of values in the study of political economy and how they are invoked to either reproduce or change rules, norms and conventions (Smith, Citation2017, p. 615). These latter two concepts resemble social purpose, but social purpose goes beyond individual normative claims, which can often take the form of pragmatic and inconsistent stories told by elites for instrumental reasons (Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 310). Rather social purpose is an interactive process in which a form of system or macro thinking is derived from a systematic diagnosis of past economic performance and involves a concerted effort to convey a desirable systemic vision derived from that diagnosis. Any given social purpose will, therefore, require actors who are willing and able to stitch together combinations of compatible cognitive and normative ideas and communicate a vision of the good and desirable system.

In invoking social purpose, one of Ruggie's intentions was to encourage scholars to pay more attention to the content of the international order – its social purpose (Ruggie, Citation1982, p. 283). Studying social purpose requires giving due consideration to how such visions of the good system are formulated and from where they emerge. In this sense, social purpose can be thought of as a sequential process. To be able to advance arguments about what is appropriate and desirable, agents need to first be able to offer a diagnosis of current inter-relations and properties of economic systems (an ontology) and reach judgements and interpretations based on that analysis (Blyth, Citation2002). Normative and moral possibilities in economic policy, it has been noted, are rooted in prevailing ontologies (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006). One implication of this is that scholars concerned with the politics of ideas should spend time interrogating economic ontologies, deciphering their potential ethical implications and likely political reception. However, the literature on economic ideas has generally had more to say about the processes through which ideas become ascendant and the fashion in which they are used, rather than thorough interrogations of the implications of their content and claims.Footnote4

Claims that ideas have a relational quality, as webs of related elements of meaning, with different parts of ideas depending closely on one another (Cartsensen, Citation2011), imply that a particular ontology and the concepts that comprise it, will have implications for normative ideas and ethical stances (Schmidt, Citation2008). A useful starting point in arriving at a deeper understanding of the content of a given order, therefore, is to give due attention to the concepts policy-makers employ to provide accounts of complex systems, including the claims those concepts make, and any normative implications that may flow from them. Intellectual heritage and lineage matter here because, as Keynes noted in his famous reference to the influence of defunct economists (Keynes, Citation1936, p. 384), many policy actors often draw unwittingly on earlier conceptual frames and writings, which often contain hidden or deep-rooted normative assumptions about moral agency and responsibility. Understanding of the politics of social purpose in the macroprudential case should, therefore, begin with a deeper analysis of macroprudential ontology, its conceptual foundations and its intellectual heritage.

Macroprudential as macrosocial ontology

As Best and Widmaier note, a fundamental ontological distinction in modern economic theory is between microeconomics and macroeconomics. Micro-approaches deploy an ontological individualism based on the rational representative agent, reducing the social world to the actions of individuals, who are alone capable of exercising moral responsibility (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006, pp. 616–617). Accordingly, ‘a methodological emphasis on micro foundations hardens into a liberal individualist normative bias’ (p. 610). A macro-ontology, on the other hand, shifts focus to collective outcomes, advancing beyond aggregation of atomistic individual agents to consider complex dynamic social systems as autonomous forces that are more than the sum of their parts (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006, p. 617). Conceptions of individual wealth and moral responsibility are consequently complicated by acknowledgement of these broader systemic forces. Macrosocial ontologies follow Keynes in seeing the economy as a social realm (p. 611), emphasising the role of collective expectations and conventions under conditions of uncertainty (p. 617). With economic policy effectiveness shaped by such expectations, overarching policy objectives are seen as something appropriately determined by wider public deliberation (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006, p. 618). Macrosocial ontologies in this reading translate into macro-ethical orientations (p. 610), implying a far more public ethics, with public authorities having an obligation to protect collective welfare and stabilise financial and economic systems (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006, p. 617). Such a shift opens up new potential macro-moralities and conceptions of the purpose of finance that were previously closed off. However, while actors operating in a micro-individualist frame have relatively little to do to assert moral and normative positions derived from the primacy of the individual in a form of passive translation, macrosocial ontologies require agents engaging in active intellectual translation, developing expansive normative reasoning, because they depend on the construction of alternative systemic visions and their subsequent communication.

The BIS, the Geneva report and the intellectual heritage of macroprudential ontology

Central bankers, the staff of the BIS and the academic economists interviewed in the course of the research for this article, all emphasised that the macroprudential frame has an eclectic range of intellectual influences from early monetarism, Irving Fisher's debt deflation thesis, to Hyman Minsky's work on financial instability (Interview, central banker, 27 March 2013, Interview IO staff, 7 February 2013). However, it is possible to show that the intellectual foundational work that outlined the core concepts that defined a macroprudential perspective have the features of a macrosocial ontology. These concepts draw heavily on Minsky's work on cyclical financial instability (even if this was not always intentional). The nature of these parallels, their roots in Minsky's reinterpretation of Keynes, their implications and significance have received only limited consideration to date (Barwell, Citation2013, p. 26; Esen & Binatli, Citation2012; Kregel, Citation2008; Papadimitriou & Wray, Citation2010, p. 129). The rediscovery of Minsky, given his previously marginal status and reputation as a voice for radical reform of capitalism, certainly warrants closer inspection in terms of its political implications as well as its intellectual ones.

While macroprudential knowledge continues to evolve, the defining conceptual core of a macroprudential perspective was established by two work streams that produced a range of papers from the early 2000s onwards. The first of these was the in-house work of BIS staff. Two speeches by General Manager Andrew Crockett were used to justify a macroprudential research agenda in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis, with BIS staff laying some claim to having invented ‘macroprudential’ (Crockett, Citation2000; Confidential interviews, 7 February 2013, 28 October 2013; Clement, Citation2010; Galati & Moessner, Citation2013). The BIS is an IO that provides data, analytical, research and information services for its member central banks (Seabrooke, Citation2006). A second stream of academic work was undertaken by the Financial Markets Group at the London School of Economics (LSE), with BIS staff themselves approvingly referring to an ‘LSE endogeneity school of risk’ (Borio, Citation2003, p. 8; Danielsson et al., Citation2001; Danıelsson, Shin, & Zigrand, Citation2004; Goodhart & Danielsson, Citation2001). Three primary academics associated with this emerging school, Charles Goodhart, Markus Brunnermeir and Hyun Shin, were all well networked in the central banking world and later teamed up with Crockett, and markets analyst and investor Avinash Persaud to produce the Geneva Report (Brunnemeier, Crockett, Goodhart, Persaud, & Shin, Citation2009). One senior Bank of England official recalled that this was the most intellectually substantial of the many post-crisis reports and did most to establish a macroprudential frame in the central banking community (Confidential Interview, Bank of England Official, March 2014). While numerous post-crisis reports referenced and called for macroprudential regulation (Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2014), it was these two streams of longer-standing work that established conceptually what the macroprudential frame consisted of and consciously developed a macroprudential ontology. As one BIS official noted: ‘most of the intellectual push for macroprudential came from BIS staff and UK based academics, some of whom later went to the US’ (Shin and Brunnermeier moved to Princeton (Correspondence from IO official, March 2012).

Fallacies of composition

Both the BIS work and the Geneva report start by identifying fallacies of composition (FOC) to highlight how financial systems are more than the sum of their parts. Identifying a problem for regulators adopting a micro-lens, the Geneva Report noted a fallacy of composition arises when ‘one infers that something is true for the whole from the fact that it is true for each of the individual components of the whole’ (Brunnemeier et al., Citation2009, p. 75). In the BIS reading, financial crises were not random events, or accidents, ‘but the outcome of systemic distortions in perceptions of risk, resulting from fallacies of composition’ (Borio, Citation2011, p. 2). Likewise, the Geneva Report noted that ‘by trying to make themselves safer, highly leveraged financial intermediaries, can behave in ways that collectively undermine the system’ (Brunnemeier et al., Citation2009, p. xi). In this respect, fallacy of composition identifies the problem of asserting systemic properties by extrapolating from individual ones. It was used to highlight the knowledge deficits faced by both regulators and market participants adopting a micro-lens and the limits of focusing on individual actions as the basis for systemic outcomes.

Both streams of work constructed financial regulation as a macroeconomic issue. The Geneva Report opened by explicitly stating, ‘in our view (macro)economic analysis and insight has, in the past, been insufficiently applied to the design of financial regulation. Our purpose is to rectify that lacunae’ (Brunnemeier et al., Citation2009, p. xi). Likewise, the BIS noted that financial regulators (with the exception of central banks) lacked the know-how to factor macroeconomic or market-wide considerations into their decision-making (Borio, Citation2011, p. 13). In the Geneva Report, one of the key critiques of existing regulatory practice such as the earlier Basel agreements was that they essentially sought to agree and harmonise best practice, without much attempt to ‘rationalise them against principles of underlying (macroeconomic) theory’ (Brunnemeier et al., Citation2009, p. 1). Earlier BIS writing had claimed the ‘macroprudential perspective’ fell squarely within the ‘macroeconomic tradition’, because it viewed financial distress in terms of its impact on economic output as a whole, rather than individual institutions (Borio, Citation2003, p. 2).

FOC were used to place an ontological premium on collective systemic outcomes, while stressing the limitations of individual preferences in producing ‘equilibria’ (Ferri & Minsky, Citation1992). In this respect, it followed Keynes observation that:

it is not a correct deduction from the principles of economics that enlightened self-interest always operates in the public interest. Nor is it true that self-interest generally is enlightened. More often individuals acting separately to promote their own ends are too ignorant, or too weak to attain even these. (Keynes, Citation1931, pp. 287–288, quoted in Minsky, Citation1975, p. 147)

Endogeneity

A second distinctive feature of macroprudential ontology emphasised in both BIS and Geneva group accounts identified the endogenous sources of financial risk and instability. Pre-crash, financial instability was largely conceived of as a function of exogenous shocks from outside of the system. The endogenous focus of macroprudential ontology shifted the analytical lens towards the ‘collective behaviours, decisions, risk perceptions and reactions of market participants (banks and financial institutions)’ (Borio, Citation2003, pp. 3, 5; Brunnemeier et al., Citation2009, pp. xv–xvi, 5, 25, 63). The BIS approvingly noted an emerging LSE endogeneity school of risk (Borio, Citation2003, p. 8; Danielsson et al., Citation2001; Goodhart & Danielsson, Citation2001) that focused attention on financial institutions’ management of balance sheet exposures as a cause of financial instability (Borio, Citation2003, p. 16). An endogenous perspective on financial instability was developed at some length by Minsky, who emphasised the importance of ‘beginning one's theorizing about capitalist economies with interlocking balance sheets’ (Minsky, Citation1995, p. 202). Rather than a benign view of market conditions forcing powerless agents to serve a social good (Ferri & Minsky, Citation1992, p. 9, fn. 14), Minsky highlighted how the profit-maximising, cost-minimising and portfolio preferences of banks could lead to short-term financing, increasing debt-to-equity ratios, resulting in increased systemic financial fragility (Minsky, Citation1995, p. 203). Both the BIS and Geneva group authors noted that market actors have incentives to react to risk in ways that are socially suboptimal (Abbreu & Brunnermeier, Citation2003; Borio, Furfine, & Lowe, Citation2001, p. 1; Brunnermeier & Nagel, Citation2004), with the Geneva report identifying size, interconnectedness with the rest of the system, degree of leverage and the role of prices in contemporary private risk models in ‘intensifying endogenous volatility’ (Brunnemeier et al., Citation2009, p. XVI).

An ontology of endogenous financial instability allows for more critical readings of private market investment techniques, strategies and business models. It also effectively diagnoses financial instability as a natural outcome of financing processes and the incentives of market agents. Minsky used his endogenous approach to make the case for authorities developing evolving ‘thwarting mechanisms’ to contain market instability (Ferri & Minsky, Citation1992, p. 24). Similarly, the endogenous focus of macroprudential ontology identifies how private decisions can pose threats to broader collective public welfare, with the implication that ‘respect for private freedoms should always be balanced against a broader sense of public interests’ (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006, p. 614). This broad acknowledgement, however, raises the question of what better collective outcomes look like, or how a collective public good should be defined in systemic terms. It also suggests a need for certain investment techniques, behaviours and financial products to be evaluated for their systemic contribution to any such wider collective public good.

Procyclicality

Procyclicality is in many respects the defining feature of macroprudential ontology. It is identified as the market process that produces an inherent and endemic financial instability. Some BIS staff view it as the primary financial market feature to be mitigated by macroprudential policy. Their analytical work in the 2000s was primarily driven by an effort to deepen understanding of procyclicality, after several central bankers had observed the term was little understood (Confidential interview, February 2014, Borio et al., Citation2001). The BIS refer to procyclicality as a financial accelerator effect first identified by Irving Fisher (Citation1933), but also explored by Kindleberger and Minsky (Borio, Citation2003, p. 6). It involves risk being underestimated by the market as a whole in booms and overestimated in recessions, with financial trading activities having an amplifying effect (Borio et al., Citation2001, p. 1). As an asset price goes up, the Geneva report explains, demand for it also rises because its risk drops, further accentuating its price level, leading to procyclical increases in leverage, further driving the cycle, with the same cycle operating in reverse, when prices fall (Brunnemeier et al., Citation2009, pp. 16–17). The BIS account presents procyclicality as a function of a time dimension – the question of how perceptions of risk change over time (Borio, Citation2011). Financial market participants have difficulty in calculating the time dimension of risk, because short-time horizons produce extrapolations of current conditions into the future resulting in misperceptions of risk (Borio et al., Citation2001, p. 2). The Geneva report also noted how market actors do not have long enough time horizons (Brunnemeier et al., Citation2009, p. 33). Earlier iterations of the time dimension of procyclicality were evident in Minsky's observation that financial liquidity was not an innate attribute, but rather was a ‘time related characteristic of an ongoing (collective) economic intuition’ (Minsky, Citation1967, p. 1). Keynes similarly observed that financial markets revolved around expectations, so that investment levels were shaped by moods and expectations about the future (Keynes, Citation1936, p. 30; Palan, Citation2015, p. 370).

In this respect, the collective social features of macroprudential ontology come to the fore in accounts of procyclicality and associated behavioural patterns of herding – a phenomenon mentioned 11 times in the Geneva report (Borio, Citation2003, p. 8; Brunnemeier et al., Citation2009, p. 39). One Geneva group author explained that herding involves banks and institutions buying and selling what others are buying and selling, because ‘in a world of uncertainty the best way to exploit others’ information is to copy what they are doing’ (Persaud, Citation2000, p. 3). In this sense, the concept of procyclicality and the behaviours associated with it follow a Keynes–Minsky tradition that sees investors wrestling with complex unknowable factors, making calculations drawn from samples of past and present market data limited guides to the future (Keynes, Citation1936, pp.156–158; Kirshner, Citation2014, p. 47; Palan, Citation2015, p. 381). A cycle of collective optimism about the future generates more credit and leverage in expectation of future earnings, but changes in mood lead to the opposite process, with collective pessimism about future earnings leading to contractions in available credit and collateral, lower volumes of trading, lower liquidity and falling asset prices, as wealth literally vanishes (Palan, Citation2015, p. 378).

Macroprudential ontology consequently places a heavy emphasis on collective social processes and conventions as drivers of market cycles and performance (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006; Nelson & Katzenstein, Citation2014). In the IPE literature, this has been referred to as the ‘reflexivity of finance’, meaning that valuations have little solid anchor outside of market participants’ assessments, with such valuation techniques not just estimating risks, but also shaping market movements by guiding market participants’ decisions (Mackenzie, Citation2008; Stellinga & Mugge, Citation2017, p. 394). Echoes of this position are to be found in the Geneva Report's critical assessment of VaR modelling where ‘risk measures are estimated naively using past data’ and where risk measures force either fire sales, or encourage procyclical expansions in leverage (Brunnemeier et al., Citation2009, p. 22). More recent macroprudential work has expressed this in terms of the distinction between risk and ‘knightian uncertainty’, when risks become unknowable, making complex modelling and institutions own VaR models less effective as guides for estimating banks’ capital requirements, than simple heuristic indicators such as leverage ratios (Aikman et al., Citation2014; Haldane & Modouros, Citation2012). Socially driven cycles of financial instability are also explored in the BIS concept of ‘the paradox of financial instability’ (Borio, Citation2011; Borio & Drehmann, Citation2009). This concept suggests that when the system looks strongest to most actors, it is at its most vulnerable, because market agents have the confidence to expand risk-taking and leverage due to low measured risk, with ‘success breeding a disregard of failure’ (Borio, Citation2011, p. 7; Minsky, Citation1986, p. 237). In this reading, individual decisions become part of a wider expectation-driven cyclical social process, producing unstable collective systemic outcomes. Again, the appropriate systemic stabilising role of public authorities, their role in mitigating such cycles, in discouraging and encouraging certain types of financial activity, and the broader question of how much stability is desirable are brought into view by macroprudential ontology.

Complexity

Complexity is a final notable element of macroprudential ontology. The BIS sees complexity as a cross-sectional dimension of risk (contrasting with the time dimension of procyclicality) – how risk is allocated across the financial system at a given point in time. They call for analyses of interlinkages to allow calculation of what each institution should pay for the systemic risk externality it imposes on the system (Borio, Citation2011, p. 3). The Geneva report similarly made the case for a greater focus on the ‘asset liability structure’ of institutions, because of the risk spillovers from one institution to the next, proposing spillover measures such as ‘CoVar’ to better capture the links across several institutions (Brunnemeier et al., Citation2009, p. 25). Complexity has an ambiguous and mixed intellectual heritage in finance. Minsky provided an account of how a euphoric economy produced a rapid complex layering of financial obligations (Minsky, Citation1970, p. 51). In such a layered structure, obligations could come to outstrip income receipts (Minsky, Citation1970, p. 54), with ‘the interdependence of payments commitments and position making across units and institutions’, meaning that the inability of one unit to meet payments would restrict the ability of recipient units to meet their payment obligations (Minsky & Campbell, Citation1987, p. 255). Other authors have noted how Hayek used a variety of complexity theory to argue that a spontaneous order of a natural pricing system could not be regulated, or foreseen with any precision (Cooper, Citation2011, p. 376; von Hayek, Citation1974). The complexity narrative has brought consideration of how to make financial regulation and structures simpler through segmentation arrangements (fire walls and so-called ring fencing) (Aikman et al., Citation2014; Haldane & Madouros, Citation2012; Haldane & May, Citation2011). Such rationales are likely to have limited public resonance, however, without a sense of the overall purpose and functions of the financial system that can be communicated publicly.

The policy neglect of social purpose?

The macroprudential perspective consequently has many of the features of a macrosocial ontology. Its focus on collective and systemic outcomes repeatedly raises questions of the collective good, the wider vision of the good financial system, its function and purpose, and desirable degrees of stability. However, such questions have by and large remained unanswered and neglected in macroprudential debates. Writing in 2016, former deputy governor of the Bank of England, Paul Tucker, lamented a lack of consideration given to the objectives and purpose of macro-financial stability regimes and worried about the lack of public debate. He called for less papers on the effectiveness of various instruments – the default mind and skill set of macro-policy researchers – and more focus on objectives, purpose and the question of what macroprudential policy is for (Tucker, Citation2016a, p. 6, 51, Citation2016b, Citation2017).

The neglect of macroprudential social purpose owes much to Best and Widmaier's distinction between micro- and macro-ontologies and their implications for normative possibilities, particularly so-called ‘macro-moralities’. In this respect, micro- and macro-ontologies create and limit ethical possibilities in distinct ways. For example, the liberal individualist normative bias, referred to by Best and Widmaier, limits ethical possibilities through a reductionist logic that claims only individuals have moral responsibilities. Former IMF Managing Director Michel Camdessus's normative case for orderly capital account liberalisation simply highlighted benefits accruing to individuals in terms of freedom and liberty (Best & Widmaier, Citation2006, pp. 610, 625–626; Blustein, Citation2001, pp. 49–50; Camdessus, Citation1999). Liberal individualist normative arguments do not require an especially expansive moral vision. Little imagination is necessary to translate their ontological claims into moral ones, because there is a restricted sense of a collective good. This is in stark contrast to macrosocial ontologies. An ontological focus on systemic dynamics and good collective outcomes means that so-called macro-moralities require an active process of intellectual translation in which a principled systemic vision is articulated. This requires the exercise of substantial, analytical and normative imagination and creativity. Macro-ontologies do open up a wider range of moral possibilities, but they also require heavy intellectual lifting to interrogate what the normative and ethical implications of a given macro-ontology may be and to position them in public debate.

Thinking about this in terms of the politics of social purpose and three phases or elements of social purpose is instructive. Moving beyond a macrosocial ontology requires agents willing to, and capable of, translating ontology as constitutive element 1, into a communicative element 2, by acting as active normative agents as well as reflexive analytical ones. In this regard, macroprudential regime development, appears to be beset by a barrier or blockage that limits attention to questions of purpose (see ).

The barrier or blockage inhibiting public debate about macroprudential purpose is partly a function of the way contemporary economic governance and knowledge production is delegated and segmented into fields of expertise and institutional settings that draw boundaries around specific tasks, skill sets and patterns of thought (Seabrooke & Henriksen, Citation2017).Footnote5 In both academic macroeconomics and central banking, patterns of scientisation, involving formal analysis, mathematical abstraction and technical mastery have been evident (Marcussen, Citation2006). Such a professional culture creates significant institutional and professional disincentives to the adoption of the kind of explicit, expansive normative reasoning required to develop and communicate macro-moralities and social purpose as a systemic vision.

BIS and Geneva Group authors may have drawn upon many of Minsky's ideas and ended up constructing a very similar macrosocial ontology, but here similarities end. In this respect, contrasting the intellectual steps Minsky took after developing his endogenous cyclical financial instability ontology with those of contemporary macroprudential intellectuals can help to illuminate the nature of the translation barrier in the macroprudential policy field. Minsky moved freely between financial system theory, the authoring of financial reform proposals for the Federal Reserve and more normative arguments intended to influence public debate and sentiment.Footnote6 He also actively linked the purpose and objectives of financial reform to broader macroeconomic priorities and questions of social justice. A theory of the financial system was viewed as a ‘prior for action’ (Minsky, Citation1991, p. 1). Reform proposals had to ‘begin with an acknowledgement that financing processes introduced endogenous destabilising forces not well suited to accommodating specialised long lived, expensive capital assets’ (Minsky, Citation1986, p. 320). From this position, Minsky came to a view that the proper role of the financial system was to promote the ‘capital development’ of the economy, broadly interpreted as a financial structure that improved living standards through job creation (Wray, Citation2011). The appropriate purpose of financial regulation was identified as (full) employment (primary), price stability and greater equality, with all three interconnected, and best delivered through mechanisms that rigged markets’ (Minsky, Citation1986, p. 326). In making this argument, both diagnostic and normative forms of reasoning were utilised.

No agreement with the orientation of Minsky's prescriptions is needed to recognise the intellectual steps he is taking. In the first half of Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, Minsky developed a financial instability ontology. In the second half of the book, he used that theory to generate a systemic vision of the desirable financial system – a sense of financial social purpose, where financial regulation was linked to other broader desirable macroeconomic goals (Minsky, Citation1986). In his reinterpretation of Keynes’ General Theory, his closing exploration of social philosophy makes an ethical case for economic policy objectives focused on employment generation and a more equal distribution of income, including limiting income from existing wealth, so that economic efficiency became ‘a hand maiden of social justice and individual liberty’ (Minsky, Citation1975, pp. 148–152). In Minsky's own terms, financial reform could not follow piecemeal approaches and patchwork changes, but had to follow a ‘thorough integrated approach’ that ‘must range over the entire economic landscape and fit the pieces together in a consistent, workable way’ (Minsky, Citation1986, p. 323). In a world of ‘reflexive finance’ (as at least partially acknowledged by macroprudential ontology), efforts to fine-tune price distortions through risk-based adjustments to capital requirements become problematic (Stellinga & Mugge, Citation2017). In this context, the case for ‘regulators emphasizing how financial governance has a direct bearing on a range of broader societal domains, and designing rules with an eye to substantive policy goals in those’ becomes much stronger (Mugge & Perry, Citation2014, p. 20).

For Minsky, the good financial system required ‘central banks being more hands on in guiding the evolution of financial institutions’, ‘favouring and encouraging long term stability enhancing activities, over short-term speculative rentier activities and discouraging instability augmenting institutions and practices’ (Minsky, Citation1986, p. 349). Such an approach would involve reaching judgements on the social worth, or otherwise, of various financial activities and products – the overall risks they generate, whether they have a long-term orientation, as well as the contributions they make to other economic objectives such as employment generation, sustainable infrastructure and technological development, for example. In other words, regulation would be driven by a vision, or conception of the social purpose of finance that would inform a constant evaluation of market products and processes (Kregel, Citation2014), including judgements on whether they induce instability, with such activities accordingly disincentivised through the levying of penalties, using combinations of taxes and or capital requirements.

Despite sharing much of Minsky's diagnosis of processes of financial instability, contemporary macroprudential intellectuals have not followed Minsky in his second step of using that ontology to generate arguments about the appropriate social purpose of finance, or in linking regulation to other broader desirable economic objectives. In short, the post-crisis rediscovery of Minsky in financial regulatory circles has been marked by a reluctance to follow in his prescriptive footsteps. This is a pattern that is particularly evident in the use of macroprudential language. The terms rentier and speculation, referring to socially and economically corrosive forms of short-term profiteering and wealth extraction, were central to Minsky and Keynes’ conceptions of capitalist dysfunction, as the primary activities to be identified and curtailed by public policy interventions. However, such pejoratives are conspicuous by their absence in contemporary macroprudential documentation.

Neither term made an appearance in the 98-page Geneva Group report. In 354 documents on the BIS website with macroprudential in the title, ranging from central bankers’ speeches, working and conference papers by academics, central bankers and IO staff, policy notes, and joint reports from the Financial Stability Board (FSB), IMF and BIS to the G20, the term rentierism or rentier made not a single appearance. ‘Speculative’ or ‘speculation’ appeared in 36 documents, just 10.1%. Only 12 of those papers went beyond a passing single incidental reference, just 3.95%. A further eight documents simply used the term to describe current practice in emerging countries, where curbing speculative or short-term investments in housing, and currency markets are stated as objectives of macroprudential policy in the cases of Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, Brazil, South Korea, Peru, China, Colombia, Thailand and Turkey (Arslan & Upper, Citation2017; Lim et al., Citation2011). This left only two outlier papers that discussed making the identification and curbing of ‘speculative’ activity an objective of macroprudential regime building. The first was a discussion paper under the auspices of the Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS), chaired by Jose Manuel Gonzalez Paramo of the European Central Bank, which suggested the use of qualitative evaluations of financial activities to assess whether they were speculative (CGFS, Citation2012, pp. 15–16). A second academic paper by MIT Researchers, building on the work of Brunnermeier on optimism and leverage cycles, presented at the Bank of England, considered the demand benefits of using macroprudential policies to constrain optimistic and pessimistic speculation (Caballero & Simsek, Citation2017). Nevertheless, the thwarting of speculative financial practices, despite being referenced in name in some emerging markets’ institutional arrangements, has remained marginal to contemporary macroprudential debate and transnational knowledge construction to date.

The barriers to translating macroprudential ontology into a systemic vision that draws on normative as well as empirical reasoning are simultaneously epistemological, professional and institutional. For example, one Geneva group author expresses reservations about seeking to differentiate and isolate socially useless (speculative) from socially valuable finance, because it is difficult to distinguish pure position taking, from operations on behalf of clients, or normal day-to-day financing functions, without jeopardising the efficient functioning of complex financial markets (Goodhart, Citation2011). Since 2009, intellectual activity for Geneva group authors has focused on modelling interactions between optimism and leverage cycles, in an effort to mathematically formalise Minsky's financial instability hypothesis (Bhattacharya, Goodhart, Tsomocos, & Vardoulakis, Citation2015; Brunnermeier & Oehmke, Citation2012).Footnote7 But these authors have not followed in Minsky's footsteps when it comes to considering how financial regulation could be linked to wider economic policy objectives. The main macroprudential focus for BIS staff since the crisis has been the collection and quarterly publication of credit–GDP gap statistics for 44 countries reaching back to 1961. The Basel III agreement uses the gap between the credit-to-GDP ratio and its long-term trend as a guide for informing the operation of countercyclical capital buffers, at the instigation of BIS officials in earlier negotiations (Drehmann & Tsataronis, Citation2014; Confidential interview BIS official, 8 February 2013). In short, as Paul Tucker has noted, the focus of professionals in the macroprudential policy field has been on data, model development and indicators at the expense of wider objectives (Tucker, Citation2016a, p. 6).

The picture is further confirmed by a recent citation analysis of both policy and academic papers on ‘systemic risk’ that shows authors remain almost entirely wedded to formal mathematic modelling, potentially excluding observable phenomenon that cannot be accommodated in such models (Thiemann, Aldgewy, & Ibrocevic, Citation2017, p. 21). Professional skill sets are similarly leading to the triumph of ‘bland reformism’ over ‘strong interventionism’ in shadow banking – an area with implications for systemic risk (Ban, Seabrooke, & Freitas, Citation2017). Official debates have ‘neither lionized shadow banking, nor treated it as dysfunctional villain’, but maintained a detached perspective, with the FSB engaged in data collection and measurement, the BIS working on the extension of conventional banking regulatory standards (Basel III) and the IMF developing notions of conditionality attached to market backstopping for fiscal reasons (Ban, Seabrooke, & Freitas, Citation2017, p. 1022). In this respect, macroprudential ontology is a predominantly central banking and academic economists’ framework of understanding. The authority of both groups rests on claims to expertise and mastery of technique to generate policy solutions. There are strong peer group incentives to stay within such boundaries, while moving beyond technical work based on mathematical prowess carries the risk of eroding professional status and esteem in peer groups (Baker, Citation2017).

There is also a strong institutional element to contemporary macroprudential politics that revolves around the act of delegation and the relationships between delegators (elected legislators) and delegated (independent agencies such as central banks staffed by unelected technocrats) (Lombardi & Moschella, Citation2017; Tucker, Citation2016a). Delegation is intended to insulate technical decision-making and institute a supposedly non-political realm. Tucker, for example, considers the limits to ‘legitimate delegation to independent agencies’, warning against tasking them with discretionary interventions that have distributional effects on households and businesses (Tucker, Citation2016a). Such conceptions of delegation also construct boundaries around the kinds of things experts can do, but also the forms of public reasoning they can deploy and engage in. A point made by several central bank officials in interviews was that the main priority in macroprudential regime building was to establish a financial stability equivalent of inflation targeting, identifying a clear target to be addressed by specific instruments (Confidential interviews, 15 December 2013, 8 February 2014, 27 March 2014). One central banker, who favoured an activist and expansive approach to financial cycle management reflected that he ‘could never win a normative argument, but could generate good data and analysis, creating compelling rationales to inform wider societal debate’ (Confidential interview, 27 March 2014).

In contemporary economic governance, ‘goals’ are increasingly viewed as the preserve of legislators and or finance ministries, but these actors have generally paid little attention to questions of ‘how much stability and stability of what’ (Tucker, Citation2016a, pp. 5, 51, Citation2016b). The interest finance ministries, governments, politicians and wider civil society actors take in the design, objectives and purpose of financial stability regimes varies by country. However, even in most of the emerging economies that have a stated intent to use macroprudential policy to stem speculative activities, there is relatively little evidence of well-developed public communicative discourses. In the advanced G7 countries, debate about the appropriate social purpose of macroprudential regimes has been even more muted. In the UK, HM Treasury has only made one contribution on the institutional design of the Bank of England's new financial policy committee (HM Treasury, Citation2011), but has published few other macroprudential public documents and lacks expertise in the area.

The countries that most clearly buck this trend of neglecting macroprudential social purpose are Brazil and South Korea. Brazil had a number of officials who sympathised with a Minskian developmental perspective, while South Korea practised a form of ‘macroprudential jujitsu’ (Gallagher, Citation2018, pp. 106, 110). In South Korea, finance minister Yoon Jeung-Hyun urged a rethink of the function of the financial system to benefit the real economy to enable capital to flow into ‘productive use’. This has been accompanied by government criticism of banks for dividend payments, rather than supporting local firms in a form of moral suasion designed to shape public expectations concerning the appropriate purpose of finance (Thurbon, Citation2016, p. 120). Such arguments chimed with a long-standing ‘developmental mindset’ (Thurbon, Citation2016), in South Korea, that as in the Brazilian case, had parallels with Minsky's argument about the purpose of financial governance being to facilitate the capital development of an economy. South Korea also has integrated policy-making and co-ordination mechanisms facilitating ‘developmentalism’ that displayed less reliance on contemporary notions of delegation, as the finance ministry worked closely with the central bank and was the dominant macroprudential agency. Moreover, in the South Korea case, it was possible to connect technical macroprudential knowledge to a sense of social purpose by engaging the services of Geneva group author Hyun Shinn as presidential advisor. Experimentation with new forms of capital controls, foreign exchange interventions, and taxes on banks dollar denominated debt based on Shin's advice to President Lee were headlined as macroprudential measures to encourage funds towards ‘productive activities’ (Thurbon, Citation2016, pp. 118–121).

Despite these exceptions, Tucker's lament about the neglect of the question of what macroprudential policy is for (Tucker, Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2017) reflects a deep-rooted knowledge–authority asymmetry. Agents with the moral and political authority (the executive branches of government and legislators) to make arguments about the desirable purpose of finance and the objectives of macro-financial regulations have generally lacked conceptual and empirical understanding of cyclical endogenous financial instability, or the capacity to draw out the implications of that for a systemic vision of the purpose of finance. Agents with knowledge of macroprudential ontology, largely central bankers and macroeconomists, lack the political authority and have few professional and institutional incentives to make public arguments about the purpose of finance. Instead, their focus has been on technical activities and tasks. Communication between the two groups has also been constrained by contemporary delegation arrangements and professional identities, while South Korean and Brazilian approaches have made little headway internationally, as evident in the limited consideration of speculation in macroprudential transnational knowledge construction. Some authors have consequently highlighted how macroprudential policy reinforces and represents a continuation of neo-liberal governance practices (Casey, Citation2015; Konings, Citation2016), with central banks using the systemic risk frame to protect the transmission mechanisms of the financial system, rather than pursue restrictive regulation of the financial sector (Konings, Citation2016, p. 16). However, it is difficult to show this is part of a concerted strategic effort by elites, because there have been so few attempts to publicly communicate this as a form of explicit macroprudential purpose. Indeed, abstaining on questions of social purpose has been effective in producing such an outcome to date, although recognition of the need to be clearer in communicating macroprudential objectives are starting to grow (Patel, Citation2017; Skingsley Citation2016; Tucker, Citation2016a).

The macroprudential knowledge–authority asymmetry, referred to above, has created a void into which chair of the US-based Systemic Risk council (a group of former regulatory professionals with the stated of intent of preventing post-crisis regulatory backsliding), and former Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, Paul Tucker, has stepped. In sketching a vision of social purpose, Tucker's preferred option is to make macroprudential ‘safe for central bankers’, by agreeing an international standard of resilience involving the maintenance of core financial services, based on a conception of the financial system as a global common resource problem (Tucker, Citation2016a, Citation2017). This is a modest vision of the social purpose of financial stability regimes, with capital requirements seen as the first and primary line of defence, agreed internationally, and adjusted according to fiscal track record and the flexibility of labour and product markets (Tucker, Citation2016a). Moreover, it neglects important macroeconomic questions, including a ‘too much finance thesis’, where crowding out and misallocation effects impede growth (Arcand, Berkes, & Panizza, Citation2015; Cecchiti & Kharroubi, Citation2012, Citation2015; Christensen, Shaxson, & Wigan, Citation2016; Epstein & Montecino, Citation2016). Macroprudential policy's potential role in guarding against these effects by reducing levels of harmful financial activity, has received little attention to date. While macroprudential's macrosocial ontology potentially opened up space for a public debate about the social purpose of finance and its regulation, there are signs that former regulatory professionals are now moving into that normative void, filling it in a conservation fashion, in an effective continuation of patterns of ‘club financial governance’ (Tsingou, Citation2015).Footnote8

Conclusion

The concept of social purpose never entirely departed the field of IPE. Nevertheless, it has languished in a state of under use, implicit consideration and passing reference. Financial reform since the financial crisis and the task of interpreting that, do create an impetus for scholars to redouble their efforts to develop understanding of the politics of social purpose, and to be more systematic and forensic in approaching this task. This article argues that in finance, social purpose originates in and emerges from accounts of economic and financial systems or economic ontology. Macroprudential ontology, it has been established, has the features of a macrosocial ontology, which brings within reach the articulation of distinctive macro-moralities regarding systemic stabilisation, systemic design and questions of the good system. By and large, these opportunities have not been pursued. The politics of macroprudential social purpose has resided in a knowledge–authority vacuum produced by epistemological, institutional and political barriers. The broader significance of this argument is that it identifies a missing ingredient in academic writing about why financial reform and macroprudential regime building has been relatively timid. Technical difficulties and reflexivity itself (Stellinga & Mugge, Citation2017), neo-liberal governmentality involving a fixation on risk at the expense of uncertainty (Konings, Citation2016), the reinforcement of neo-liberal growth models (Casey, Citation2015,) principal-delegator's desire for control through symbolic politics (Lombardi & Moschella, Citation2017), and private sector resistance (Helleiner, Citation2014) have all been forwarded. None, however, fully capture the emerging political economy of macroprudential regulation. Likewise, scholar of the Minsky archive, Jan Kregel, has argued that the problem with macroprudential regulation is that it has lacked a theory of dynamic endogenous financial instability to underpin it (Kregel, Citation2014). On the contrary, this paper has argued that such a theory is identifiable in foundational macroprudential ontology. The problem is not the lack of theory, but the failure to fully interrogate that theory and the lack of actors willing and able to translate it into a sense of the overarching social purpose macroprudential policy regimes should serve. Normative agents in the macroprudential policy field are thin on the ground. The politics of social purpose can help us to understand the obstacles to more ambitious forms of macroprudential policy. In this respect, social purpose is a crucial missing ingredient in macroprudential debates, both in policy terms, and in academic efforts to understand and interpret the political economy of this emerging policy field, and of post-crisis financial reform more generally.

Acknowledgments

This paper has been presented at events at Yale, New Orleans, Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam and Copenhagen, and has benefitted from five sets of extensive commentary, as well as three very helpful sets of reviewers’ comments. Particular thanks are due to Wade Jacoby, Martin Carstensen, Cornelia Woll, Vivien Schmidt, Cornel Ban, Wesley Widmaier, Leonard Seabrooke, Adam Leaver, Liam Stanley. Mark Blyth, Oddný Helgadóttir, Julian Gruin, Jonathan Zeitlin, Daniel Mugge, Bart Stellinga, Geoffrey Underhill, Matthias Thiemann and Daniela Gabor. Remaining errors and oversights are the author's sole responsibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrew Baker

Andrew Baker is Professorial Fellow in the Faculty of Social Sciences (Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute and Department of Politics) University of Sheffield, UK and is a co-editor of the journal New Political Economy.

Notes

1. Ruggie began the 1982 article with reference to looking for a black cat in a black room, while making the case for an interpretative epistemology. The difficulties of studying social purpose, of identifying it, of studying its politics have possibly put scholars off, but this suggests that creating firmer analytical foundations for the study of social purpose is warranted.

2. Ruggie referred to social purpose functioning through a ‘generative grammar’ of understanding that gave content to international economic order and its systems of governance.

3. The main exception is the work of Bastiaan Van Apeldoorn who developed a neo-Gramscian account of the social purpose of the European Single Market project (Van Apeldoorn, Citation2003).

4. Notable exceptions are to be found in the work of Best (Citation2005, esp. Ch. 5), Widmaier (Citation2016a, Citationb), Ban (Citation2016) and Helgadottir (Citation2016).

5. Seabrooke's work emphasising the role of knowledge brokers that link professional ecologies does not run contrary to this line of argument. One of the reasons knowledge brokers who span different professional groups are of high potential influence is because of the segmented, compartmentalised and tightly delegated nature of contemporary knowledge production (Ban, Seabrooke, & Freitas, Citation2017; Seabrooke, Citation2014; Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2009).

6. In 1966–1997, Minsky drafted a proposal for a new bank examination procedure for the Federal Deposit Commission and drafted follow ups for the Federal Reserve (Kregel, Citation2014; Minsky, Citation1967).

7. Charles Goodhart notes that, while he finds Minsky ‘enormously attractive’, his ideas are difficult to model in a rigorous way (http://www.metropolis-verlag.de/Minsky-I-find-enormously-attractive-but-his-issues-are-very-difficult-to-model-in-any-rigorous-way/13012/book.do). He and other Geneva group authors engage with Minsky but do not pick up the hedge, speculative and Ponzi distinctions.

8. NGOs are a possible countervailing force including one narrative that identifies a ‘finance curse’ effect (see CitationBaker & Wigan, 2017).

References

- Abreu, D., & Brunnermeier, M. K. (2003). Bubbles and crashes. Econometrica, 71(1), 173–204.

- Aikman, D., Galesic, M., Gigerenzer, G., Kapadia, S., Katsikopoulos, K. V., Kothiyal, A., … Neumann, T. (2014). Taking uncertainty seriously: Simplicity versus complexity in financial regulation. Munich Personal RePEc Archive. Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/59908/1/MPRA_paper_59908.pdf

- Arcand, J. L., Berkes, E., & Panizza, U. (2015). Too much finance? Journal of Economic Growth, 20(2), 105–148.

- Arslan, Y., & Upper, C. (2017, December). Macroprudential frameworks: Implementation and effectiveness1. (BIS Papers No. 94). Retrieved from https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap94.pdf

- Baker, A. (2013a). The new political economy of the macroprudential ideational shift. New Political Economy, 18(1), 112–139.

- Baker, A. (2013b). The gradual transformation? The incremental dynamics of macroprudential regulation. Regulation & Governance, 7(4), 417–434.

- Baker, A. (2017). Esteem as professional currency and consolidation: The rise of the macroprudential cognosenti. In L. Seabrooke & L. Henriksen (Eds.), Professionals and organizations in transnational governance (pp. 149–164). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baker, A., & Widmaier, W. (2014). The institutionalist roots of macroprudential ideas: Veblen and Galbraith on regulation, policy success and overconfidence. New Political Economy, 19(4), 487–506.

- Baker, A., & Wigan, D. (2017). Constructing and contesting City of London power: NGOs and the emergence of noisier financial politics. Economy and Society, 46(2), 185–210.

- Ban, C. (2016). Ruling ideas: How global neoliberalism goes local. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ban, C., Seabrooke, L., & Freitas, S. (2016). Grey matter in shadow banking: International organizations and expert strategies in global financial governance. Review of International Political Economy, 23(6), 1001–1033.

- Barwell, R. (2013). Macroprudential policy: Taming the wild gyrations of credit flows, debt stocks and asset prices. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Best, J. (2005). The limits of transparency: Ambiguity and the history of international finance. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Best, J., & Widmaier, W. (2006). Micro or macro moralities? Economic discourses and policy possibilities. Review of International Political Economy, 13(4), 609–631.

- Bhattacharya, S., Goodhart, C. A., Tsomocos, D. P., & Vardoulakis, A. P. (2015). A reconsideration of Minsky's financial instability hypothesis. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 47(5), 931–973.

- Bieling, H. J. (2014). Shattered expectations: The defeat of European ambitions of global financial reform. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(3), 346–366.

- Blustein, P. (2001). The chastening: Inside the crisis that rocked the global system and humbled the IMF. New York, NY: Little Brown.

- Blyth, M. (2002). Great transformations: Economic ideas and institutional change in the twenty first century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Borio, C. (2003). Towards a macroprudential framework for financial supervision and regulation? CESifo Economic Studies, 49(2), 181–215.

- Borio, C. (2011). Implementing a macroprudential framework: Blending boldness and realism. Capitalism and Society, 6(1), 1–23.

- Borio, C. (2013, April). Macroprudential policy and the financial cycle: Some stylized facts and some suggestions. Paper presented at Rethinking Macro Policy II: First Steps and Early Lessons, Washington, DC.

- Borio, C., & Drehmann, M. (2009). Towards an operational framework for financial stability: 'Fuzzy' measurement and its consequences. BIS Working Paper, No.284. Retrieved from https://www.bis.org/publ/work284.pdf

- Borio, C., Furfine, C., & Lowe, P. (2001, March). Procyclicality of the financial system and financial stability issues and policy options. (BIS Working Paper No. 1, pp. 1--57). Retrieved from https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap01a.pdf

- Brunnemeier, M., Crockett, A., Goodhart, C., Persaud, A., & Shin, H. (2009). The fundamental principles of financial regulation. Geneva Report on the World Economy 11. Geneva: International Centre for Monetary and Banking Studies; London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

- Brunnemeier, M., & Nagel, S. (2004). Hedge funds and the technology bubble. The Journal of Finance, 59(5), 2013–2040.

- Brunnermeier, M. K., & Oehmke, M. (2012). Bubbles, financial crises, and systemic risk. National Bureau of Economic Research (Working Paper No. 18398). Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w18398

- Butzbach, O. (2016). Systemic risk, macro-prudential regulation and organizational diversity in banking. Policy and Society, 35(3), 239–251.

- Caballero, R. J., & Simsek, A. (2017). A risk-centric model of demand recessions and macroprudential policy (No. w23614). National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from https://economics.mit.edu/files/13059

- Camdessus, M. (1999). From the crises of the 1990s to the new millennium: Remarks to the International Graduate School of Management, 27 November 1999, International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/external/np/speeches/1999/112799.htm

- Campbell, J. L. (1998). Institutional analysis and the role of ideas in political economy. Theory and Society, 27(3), 377–409.

- Campbell, J. L. (2004). Institutional change and globalization. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Carstensen, M. B. (2011). Ideas are not as stable as political scientists want them to be: A theory of incremental ideational change. Political Studies, 59(3), 596–615.

- Casey, T. (2015). How macroprudential financial regulation can save neoliberalism. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 17(2), 351–370.

- Cecchiti, S., & Kharrobi, E. (2012) Reassessing the impact of finance on growth (BIS Working Paper No. 381). Retrieved from https://www.bis.org/publ/work381.pdf

- Cecchetti, S. G., & Kharroubi, E. (2015). Why does financial sector growth crowd out real economic growth? CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP10642, Retrieved from https://cdn.evbuc.com/eventlogos/67785745/cecchetti.pdf

- CGFS. (2012, December). Operationalising the selection and application of macroprudential instruments. CGFS Papers No. 48. Retrieved from https://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs48.pdf

- Christensen, J., Shaxson, N., & Wigan, D. (2016). The finance curse: Britain and the world economy. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18(1), 255–269.

- Clement, P. (2010, March). The term 'macroprudential': Origins and evolution. BIS Quarterly Review, pp. 59–67.

- Cooper, M. (2011). Complexity theory after the financial crisis: The death of neoliberalism or the triumph of Hayek? Journal of Cultural Economy, 4(4), 371–385.

- Crockett, A. (2000, September 21). Marrying the micro and macroprudential dimensions of financial stability. BIS Speeches.